Insight – Charles Sturt University

Why we still need to study the humanities

The story of us – Homo sapiens – is intriguing and complex. We’re unique creatures living in a rapidly changing world and we continue to face new challenges and opportunities. The study of humans, and all we’ve done, has always been of value. But studying the humanities now is probably more important than ever before!

We chatted with Charles Sturt University’s Jared van Duinen, who’s been teaching humanities for more than 15 years, and asked: what exactly are the humanities and why is it so important to study them in the 21 st century?

So, what are the humanities ?

First things first. When you sign up to learn about humanities, what sorts of topics will you study?

“Well, traditionally, the humanities are those disciplines that deal with human interaction, society and how humans get along in society. So think history, sociology, philosophy, politics, English literature and Indigenous studies.”

Why is it so important to study humanities?

Learning about ourselves – through the various humanities – helps us to create a better world.

“It’s the human in humanities that is worth studying. Humanities can tell us about ourselves, how we interact and get along and why we sometimes don’t!”

“Studying the humanities helps us to better understand who we are, our identity as a people, a society and a culture, and how to organise our societies so we can achieve our goals.

“Importantly, the study of humanities is a wonderful way of exploring our Charles Sturt ethos of Yindyamarra Winhanganha.

“Obviously STEM – science, technology, engineering and mathematics – has a role to play in creating a world worth living in. But the study of humanities can help create a better world, just as much, if not more so, than scientific and technological innovation.”

Tackling the world’s issues

Jared believes that understanding the humanities can help you deal with all sorts of issues and problems facing the world. Big, small and ‘wicked’ ones! How? By taking you behind the human scene, giving you an insight into some really valuable information, and equipping you with a unique set of skills.

- History. Studying the past helps us understand where we’ve come from and learn lessons to help us deal with the future.

- English literature helps us explore the great themes of human interaction and better understand each other.

- Sociology helps us to understand human behaviour, culture and the workings of society.

- Philosophy helps us to think well, clearly, ethically and logically.

- Politics. Learning about political processes and their impacts will help us understand how social and political change occurs.

- Indigenous studies is especially important because Australia has an Indigenous population. If we’re trying to create a world worth living in, a fuller understanding of the perspective of our Indigenous population is essential.

A practical reason to learn about the humanities – the ultimate skill set!

The other super valuable reason to study humanities is more practical. Studying humanities will give you knowledge and skills that you can use all throughout your working life! And grads who study in this field are catching the eye of more and more employers.

“People who study these disciplines are really important to employers. They gain these important, sought-after skill sets:

- effective communication

- critical thinking

- creative thinking

- emotional intelligence

- working well in teams

- cultural understanding

- problem solving.

“Humanities grads have always had these skills in abundance, but for a long time these skills were disregarded or overlooked because they were generic. They didn’t speak to a particular vocation.

“But the world of work is changing, becoming more unpredictable. It’s suggested that a lot of graduates coming out of uni now will change careers five to seven times. So those more well-rounded, transferable or soft skills you gain from studying history, philosophy or English literature will really become important. Having them is now seen as a strength because you can carry them from one occupation to your next. And recent studies highlight that these types of soft skills – the ones humanities graduates gain – are what helps them land jobs.

“Employers say these skills matter. They can teach technical knowledge, but they don’t always have the time or know-how to teach employees these vital soft skills. They look for employees who have these skills well-honed and are ready to work.”

Studying humanities gives you a swag of soft or transferable skills. That means you’ll be the employee who is more flexible. You can pivot from one role to another and adapt faster to changing roles. You become an asset. Now – and definitely into the future!

What jobs are there in humanities?

So, guess you want to know what sort of career you could go into? Studying humanities with Charles Sturt can really take you places – even if you’re not sure where you want to go just yet.

What sort of jobs, you ask?

- Public service – in local, state and federal government. (History grads often end up in the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade!)

- Non-governmental organisations, not-for-profit groups and advocacy groups

- Corporate sector – management and marketing, publishing and media

- Social work

- Policy work

“Studying humanities through our revitalised Bachelor of Arts allows you to study a wide range of disciplines. And that’s especially ideal for those who aren’t quite sure what career path they’ll go down. Those who don’t necessarily know what job they do want, but know they want to study.”

But what about the rise of job automation. How will studying humanities protect you from losing a job to a robot? It all leads back to those very special skills that you’ll build!

“With the increasing automation of many industries, those skills that are resistant to automation, such as critical thinking, cultural understanding, and creative problem solving, are going to be in greater demand.”

Set yourself up for success – now and in the future!

Want to explore the humanities and build a degree that’s meaningful to you and sets you up for career success? Keen to develop the ultimate soft skill set that will help get your first job – and your second and third and fourth? Check out our Bachelor of Arts and let’s get to work!

Bachelor of Arts CRICOS code: 000649C

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

You must be logged in to post a comment.

A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry

A look at history and popular culture

Collections: The Practical Case on Why We Need the Humanities

(Note: Thanks to the effort of a kind reader, this post is now available in audio format here )

I have been holding off writing something like this, because it is often such a well-worn topic and I hardly wanted to preach to the converted. But at the same time, the humanities need all of the defenses they can get and I’ve found, looking at the genre, that my answers for why we need the humanities are rather different from the typical answer.

But first, the shameless plug that if you , yes you! want to support the humanities, you can support this humanist by sharing my writing, subscribing with the button below or by supporting me on Patreon . Your support enables me to continue telling you and other people to continue supporting me, a giant self-devouring ouroboros of support that will grow to become so large it will crush the world (I look forward to regretting this joke in the future).

Email Address

Edit: A friendly reminder to those in the comments: you will be civil . This thread has prompted some spirited discussion. That’s fine. But it will remain polite.

What Humanities?

First, just to define my terms, what are the humanities ? Broadly, they are the disciplines that study human society (that is, that are concerned with humanity): language study, literature, philosophy, history, art history, archaeology, anthropology, and so on. It is necessarily a bit of a fuzzy set. But what I think defines the humanities more than subject matter is method ; the humanities study things which (we argue) cannot be subjected to the rigors of the scientific method or strictly mathematical approaches. You cannot perform a controlled trial in beauty, mathematical certainty in history is almost always impossible, and there is no way to know much stress a society can bear except to see it fail. Some things cannot be reduced to numbers, at least not by the powers of the technology-aided human mind.

By way of example, that methodological difference is why there’s a division between political science and history , despite the two disciplines historically being concerned with many of the same subjects and the same questions (to the point that Thucydides is sometimes produced as the founder of both): they use different methods . History is a humanities discipline through and through, whereas political science attempts to hybridize humanities and STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) approaches; that’s not to say historians never use statistical approaches (I do, actually, quite a lot) but that there are very real differences in methodology. As you might imagine, that difference leads to some competition and conflict between the disciplines as to whose methodology best answers those key questions or equips students to think about them. Given that I have a doctorate in history and self-identify as a historian, you will have no trouble guessing which side of this I come down on, although that might be a bit self-interested on my part.

So if the STEM fields are, at some level, fundamentally about numbers, the humanities are fundamentally about language . The universe may be made of numbers, but the human mind and human societies are constructed out of language. Unlike computers, we do not think in numbers, but in words and consequently, the study of humans as thinking creatures is mostly about those words (yes, yes, I see you there, economics and psychology; there are edge cases, of course). Our laws are written in words because our thoughts form in our heads as words; we naturally reason with words and we even feel with words. Humans are linguistic creations in a mathematical universe; consequently, while the study of the universe is mediated through math, the study of humans and human minds is fundamentally linguistic in nature.

Thus, the humanities.

Oh, the Humanities!

Now I want to note here the standard defense of the humanities, which is that the study of human culture, literature and art enriches the soul and the experience of life. This is, to be clear, undoubtedly true . There is joy and richness in the incredible kaleidoscope of human expression and a deep wisdom in the realization of both how that expression joins us, and how radically different it can be. There is also the enjoyment of developing a ‘palette’ for art and literature which is enhanced by knowing more of it, in being able to see the innovations and cross-connections (the ‘intertext’ to use the unnecessarily fancy academic term). This is all very much the case. There is a reason that rich people with abundant free time have consistently gravitated to the study of the humanities, or supported it.

But this is a weak defense of the humanities as they are currently constructed . The fact is that the academic humanities exist because people who do not study the humanities fund them. The modern study of the humanities, in its infancy, was paid for by wealthy elites who wanted either that joyful richness or at least the status that came from funding it. I should note here also that the humanities were never for the teachers of the humanities, but for its students. The rich funders of the humanities were rarely the authors of the great treatises or studies; rather they wished to be the readers of them (and likewise, the modern academic humanities are not for professors, but the students we teach; more on this next time ). Down until really quite recently, education in the humanities was largely reserved for that elite and their academic clients. As public support for the humanities continues to decline, many humanities fields seem in real danger of reverting back to that status: a prestigious toy for the already-rich and already-elite.

Avoiding that retreat of the humanities back into the wealthy elite means defending the humanities on different grounds. Of course, the traditional humanities will always survive at Harvard or Cambridge or Yale. But for the humanities to actually be generally available, they need to survive, to thrive, outside of those spaces. And yet, no good that is tethered to colleges can be justified solely through the benefit it gives the holder. Colleges, after all, are publicly funded, but while everyone pays taxes, not everyone goes to college . The OECD average rate for tertiary-education-completion among adults is around 37% and not all of those are four-year university degrees. To break down the United States’ data, while 44% of Americans have completed some kind of tertiary education, putting the USA towards the top of the scale (and around two-thirds have at least some college, though they may not have completed it), only 35% of Americans have a four-year degree . And of course, only a subset of those degree-holders will have taken very much in the way of the humanities. Which means the taxes that pay to fund the public universities that make up the great bulk of the study of the humanities are going to mostly come from people who have not, or could not, avail themselves of a humanistic education .

Even if we made the humanities available to all – a goal I robustly support (it is one reason I am spending all this time working on this open, free web platform, after all) – that effort would likely have to be publicly funded through a great many tax-payers who did not care to consume much of the academic products of the humanities (even if they consume many of its pop-cultural byproducts without knowing it). We must be able to justify the expense to them . And alas, while I love crowd-funding (did I mention, you can support me on Patreon ?), it is simply not an alternative for the research and teaching environment of the university (though I think it is and ought to be an important parallel model, for reasons I’ll get into in a moment). The fact is that while ‘short’ essays, blog posts and public-facing books can be popularly funded, the slow, painstaking work that forms the foundation for those efforts has no ready popular market ; but without the latter, the former withers (as a note: my next Collections post will be on the process by which knowledge filters from the latter to the former).

We must be prepared to explain the value of the humanities to people for whom the humanities hold no interest, or appear out of reach (though I feel the need to again reiterate that I think it behooves society to put the humanities within reach for everyone).

The Pragmatic Case for the Humanities

So rather than asking – as many of these sorts of ‘defenses of the humanities’ do – “why study the humanities” the question we ought to ask is “ why would you put down money so that other people can study the humanities? ” The STEM fields have long understood that this is the basis on which they need to defend their funding; not that science is personally enriching, but that it produces things of value to people who are not scientists, engineers, mathematicians or doctors . And they have ready answers in the form of inventions, medicines, soundly constructed machines and so on.

I firmly believe that the humanities can be defended on these terms and will now endeavor to do so.

The great rush of STEM funding that has slowly marginalized the humanities within our education system (it was, for instance, not hard to notice growing up that my school district had a special high school for students gifted in “science and technology” but no such program for students gifted in writing, art, history, and so on) has long been justified on national defense grounds. We needed science to ‘beat the Russians’ and now we need it to ‘beat the Chinese.’ I don’t want to get lost in the weeds of if ‘beating the Chinese’ (which I think, would be better phrased as ‘deterring the leaders of the PRC from mutually destructive conflict’) is a worthwhile goal. But I want to assess the humanities on that strict, materialistic basis (even though I believe there is rather more to our lives and world than a strict materialist outlook), because if the disciplines of the humanities may be justified on these grounds, they may be justified to anyone.

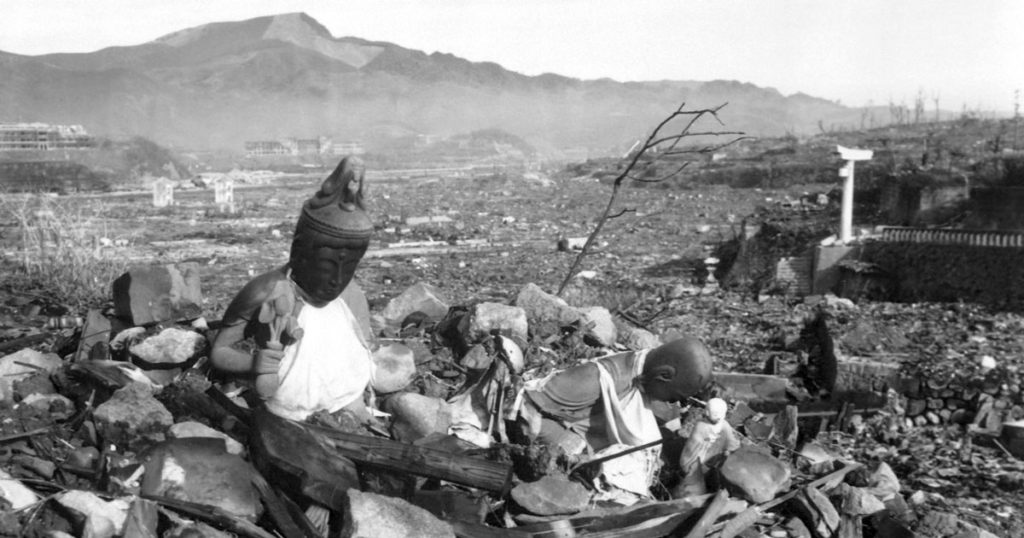

The core of teaching in the humanities is the expression of the grand breadth of human experience. As I hope the images I’ve been using throughout this essay have conveyed, when I say the humanities, I do not just mean a study of the traditional Western canon (by which I mean Greece, Rome, the Renaissance (but rarely the Middle Ages), all in Europe), but of the humanities spread widely over time and space . A ‘humanities’ which covers only elite European men is a narrow field indeed, to its detriment (the same could be said of a field that excluded them, but there is little chance of that). On the one hand, this provides a data set of sorts – a wide range of information about places, cultures and people. But more importantly than that, it is meant to teach students how to go about learning about a place or a people not their own, to inspire a degree of ‘epistemic humility’ (that is the knowledge that you do not know everything ) and also what I call an ’empathy of diversity’ – the appreciation that the human experience and the things humans do and value varies quite a bit place to place and person to person and that what seems strange to us seems normal to others.

(That is, by the by, not an invitation to endless crass moral relativism – some strange foreign customs are bad , some comfortable domestic customs are bad too . Accepting that I, and my society, do not have a monopoly on virtue is not the same thing as declaring virtue itself an impossibility, or even that it is undiscoverable in an absolute sense.)

These experiences, bottled up in artwork, literature, languages, histories and laws, forms the evidence base of any given humanities discipline. But that breadth of evidence, properly delivered, teaches through experience to a depth that merely saying the maxim cannot, two core things: that in the human experience, the human component is constant , even while the experience is not . That is, on the one hand, “the past is a foreign country, they do things differently there” (and foreign countries are foreign countries too!) but at the same time – homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto (I am human, and I think nothing human to be alien to me). Put another way: people are people, no matter where and no matter when, but the where and when still matter quite a lot!

(Now you might argue that there are certain trends within the humanities which present this or that maxim as a transcendent, nearly theological proof and thus fundamentally undermine this message by undermining both epistemic humility and the empathy of diversity with the promise of One True Revelation. And I agree! I am very troubled by this. But the problem is hardly solved by dumping the entire study altogether; if anything, the shrinking of the humanities has made this problem worse as smaller and more poorly funded departments are easier for political interests with ‘one true revelation’ to colonize and dominate.)

The other thing we ask students to do, beyond merely encountering these things is to use them to practice argumentation, to reason soundly , to write well , to argue persuasively about them. That may sound strange to some of you. I find that folks who have not studied in the humanities often assume that each discipline in the humanities consists of effectively memorizing a set of ‘data’ (historical events, laws, philosophies, great books, etc) and being able to effectively regurgitate that information on demand. Students often come into my class thus impatient to be ‘told the answer’ – what is the data I need to memorize? But the humanities are far more about developing a method – a method that can be applied to new evidence – than memorizing the evidence itself. Indeed, the raw data is often far less important – I am much more interested to know if my students can think deeply about Tiberius Gracchus’ aims and means than if they can recall the exact year of his tribunate (133, for the curious).

What a student in these classes is – or at least, ought to be – doing is practicing a form of considered decision-making : assessing the evidence in a way that banishes emotion and relies on reason (which is why we encourage students to write plainly and clearly, without too much rhetorical flourish), and then explaining that reasoning and evidence to a third partly clearly and convincingly . Assertions are followed by evidence and capped off by conclusions in a three-beat-waltz with a minimum of fuss and a maximum of clarity. Different disciplines in the humanities have different kinds of evidence and methods of argument they use – legal argument isn’t quite the same as historical or philosophical argument – but they share the core component of argumentation. I tell my students that even if they never use any fact or idea they encounter in a history course ever again in life – unlikely, I think, but still – they will still use these skills, practiced in formal writing but applicable in all sorts of circumstances, for the rest of their lives in almost anything they end up doing.

What is being taught here is thus a detached, careful form of analysis and decision-making and then a set of communication skills to present that information . Phrased another way: a student is being trained – whatever branch of specialist knowledge they may develop in the future – on how to serve as an advisor (who analyzes information and presents recommendations) or as a leader (who makes and then explains decisions to others).

And it should come thus as little surprise that these skills – a sense of empathy, of epistemic humility, sound reasoning and effective communication – are the skills we generally look for in effective leaders . Because, fundamentally, the purpose of formal education in the humanities, since the classical period, was as training in leadership .

As I’ve already noted, in much of the past, this sort of education was quite clearly limited to a hereditary (or effectively hereditary wealth-defined) class of leaders. Elite Roman education began with basic grammar, but extended to the analysis of poetry, the reading of literature and from there into the study of rhetoric, history and philosophy. Particularly for history, the ancient Greeks, with whom the discipline of history began, left little mystery as to its purpose: history as a field existed to inform decision-making and leadership. As Thucydides puts it, “but if it be judged useful by those inquirers who desire an exact knowledge of the past as an aid to the understanding of the future, which in the course of human things must resemble if it does not reflect it, I shall be content” (Thuc. 1.22.4). Plutarch ( Alexander 1.1-3) and Polybius (1.1.1-4) are similarly direct. Polybius goes so far as to say “men have no more ready corrective of conduct than knowledge of the past” (Plb. 1.1.1). But the same was true for the reading of literature, the development of knowledge in law, oratory and philosophy. These were leadership skills , taught to aristocrats who were assumed to be future leaders. This was true not merely in Greece and Rome (where I just happen to have the easy textual references) but in every sophisticated agrarian society I am aware of, from the universities of medieval Europe to Chinese aristocrats training for Imperial examinations .

(As an aside – note that the use of history in particular in this way is not merely because ‘history repeats.’ In the first case, history does not repeat; if it did, we should surely be around to the second (or third) Akkadian Empire by now. Rather, as Thucydides says, human affairs resemble themselves , because they contain in them the same one dominant ingredient, the one thing the humanities study: humans. The best guide to future human behavior is past human behavior, and history is the best way to sample a lot of that behavior, especially in circumstances that are relatively uncommon.)

Does anyone look at the present moment and conclude that we have an over-abundance of humble, empathetic, well-trained and effectively communicating leaders?

Soft Skills in Soft Power

That is, of course, not the only thing the humanities offer to a society. As I noted above, the steady marginalization – as a matter of education and funding – of the humanities in favor of STEM in the United States has been motivated by the need to ‘win’ geopolitical contests. And perhaps the most obvious benefit of the humanities, particularly in the geopolitical sphere, is the soft-power aspect of a robust culture ‘industry.’ No rocket, no weapon-system of any kind was as instrumental in the collapse of Soviet Communism as Hollywood and Rock’n’Roll – or more correctly the vast culture edifice that those two ideas are used to represent. The Soviet Union wasn’t defeated with missiles, after all, it collapsed from a failure of ideological legitimacy ; a crisis of words not numbers. What we’ve seen again and again over the last century (and even longer, if one cares to look) is that the vast soft power of cultural cachet is often far more cost-effective than new weapons (in part because new weapons are just so expensive). Athens lost the Peloponnesian War, but remained an important place for centuries, while Sparta – which won – sank into irrelevance. It is hard not to conclude that Athens lost the war but decisively won the peace and that it was the latter victory that actually mattered.

The response to this is typically the glib assumption that this cultural ‘effectiveness’ is simply the product of chance, or individual genius or just a product of markets. But the fact is no one is born a great producer of culture; all of the skills are trained. And they are refined against a backdrop of deep complexity, of interleaved references and homages to older and older works. Those rich traditions are kept alive in the humanities to provide so much of the raw material for new artists and writers to hammer into new ideas, new mixtures of old themes and motifs. And while academic cultural criticism can often be self-indulgent and jargonistic, it serves an important role of examining the motifs we would otherwise use unthinkingly, which in turn can lead to the production of yet better (or just new) art. It also trains us to be critical of our art, in a way that makes the public harder to beguile and the art itself better.

At the same time, the study of the humanities, properly done, broadens the range of reference points beyond a single culture. As I hope the images that go with this essay show, when I say the humanities, I do not simply mean the study of the same few dozen European ‘great books.’ By no means am I throwing the western ‘canon’ out, but it is not the whole of the humanities. That in turn can provide a means of training the ability, however dimly, to ‘see’ through the eyes of other cultures (and in other languages, of course); the geopolitical benefits of having people trained this way, prepared with a wide range of cultural reference points from many times and places, should be obvious.

I think the impact that the academic humanities have on that process is often obscured by the intermediate layers that this knowledge passes through. Of course a great many cultural creators do not immerse themselves in four-year humanities degrees (although quite a number do, and it certainly seems to me that most writers, artists and musicians are quite open that the quality of their own art is dependent on sampling the art of other great creators, past and present, which would not exist in accessible form without the academic humanities or their public siblings). Rather, the study of the humanities creates a certain level of diffused knowledge in the society that is available to everyone. It is sufficiently diffused that it is often supposed that we might do as well without its source, but that is a mistake of understanding. I do not stand next to my A/C to get cool (because it cools my whole apartment, albeit less evenly than I might like), but if I turn it off, things will surely get warmer! Likewise, if you disassemble the academic and public humanities, you will quickly find that their beneficial influence on even the art produced beyond their borders wanes, to the detriment of the final product and the culture at large. And yet that diffusion makes the case for the humanities more difficult because it takes training in the humanities, sometimes, to see the influence of the humanities in the broader culture.

In the meantime, it seems to me no accident that as the funding for the humanities, and the social importance placed on a broad humanistic education, has dwindled, it has produced a matching decline in the richness of our cultural products that at this point has been broadly noticed: more and more sequels or remakes of things that aren’t even very old yet; the same handful of properties and themes flogged to death with precious little in the way of innovation. The reference pool has grown small and stagnant, even as every library in the country has an unplumbably deep well of rich ideas, just waiting to be discovered, if we only got back to teaching ourselves how to fathom those depths.

The frustration I most often encounter – particularly from students coming from high schools that too often ‘teach to the test’ instead of teaching skills – is in the apparently round-about way that the humanities teaches these things. Why not shovel money directly into Hollywood and a handful of ‘leadership institutes’? But – and I apologize, because I am going to adapt a phrasing I saw from someone else but can no longer find – that is the equivalent of the student arriving to class asking to “just be told the answers.” The point was never the answers, but the skills you gained finding them .

Leadership courses can reduce some of these ideas to basic maxims – good for what it is; maxims can be very helpful – but they cannot teach you how to discover new maxims . They cannot prepare you for a situation where you find that all of your old maxims are useless because the culture you are in or the people you are now leading do not value a ‘firm handshake’ or ‘strong eye-contact,’ to use one example. Maxims are rigid; the world demands flexibility . And there is no short-cut but to practice reasoning and argumentation, over and over again, in one unfamiliar discipline, one unfamiliar cultural sphere after another (which, of course, in turn necessitates teaching by individuals who are hyper-specialized in those disciplines and cultural spheres, not because humanist academics are the best leaders – note how the skills to teach are not the same skills as to practice . One of these days, we will discuss the art of teaching a bit; suffice to say the old canard ‘those that cannot do, teach’ is rubbish. Few who do can teach , but most who teach can do; they are different skills, only infrequently found together).

And at the moment, particularly, it seems to me that those sort of leadership skills – calm, sound reasoning, careful explanations, epistemic humility and compassion – are in short supply. As I write this – future readers, note the date – we are still in the grip of a global pandemic. What we see is not a failure of our science – by no means! We have clearly gotten our money’s worth from our doctors and scientists who continue to do heroic work. Researchers are breaking one vaccine speed record after another. The speed with which new medical methods and data are brought to bear on the viral enemy is astoundingly fast. But so far, that work hasn’t had the impact it could have had because of leadership failures – failures to buy the scientists the time they need to do their work, to get the public to follow best practices.

Our knowledge of science hasn’t failed – our knowledge of humanity has. And can it be any surprise? Since the 1950s, the humanities – particularly the academic humanities that teach the skills I have been talking about – have faced cuts not only in the United States but around the globe, over and over again. What is happening as a result is that the humanities are collapsing back into what they were in the ancient world: a marker or elite status and privilege, available to those born to wealth .

Which is a real problem, because it isn’t enough for this to be a skill-set held only by a tiny class of designated, hereditary ‘leaders.’ Rather, it behooves us for the humanistic skills to be broadly distributed in society, so that they are widely available. In the same way that I discussed above, where an artist might benefit from the broad array of influences in the humanities without having done a four-year-degree themselves – through their proximity to others who have – society benefits broadly by having skills in the humanities widely diffused. After all, you need someone in the lab to ask if we should, not merely if we can (it is striking, in that scene, that this observation is given to Ian Malcolm, a mathematician, rather than an ethicist or a historian or someone else whose knowledge actually bears on the question of should ; this is Hollywood’s fetishism of scientific knowledge at work. For exhibit B, notice how even the officers in Star Trek: The Next Generation have their training in science rather than in leadership , like real officers do (the Kirk era knew better!) – the only actual knowledge treated as such in TNG is generally scientific knowledge). You need people at every level of business and government who can ask larger questions and seek greater answers in places where science is unable to shed light. It does no good to silo those skills away to a select, elite few.

The most pressing problems that we face are not scientific problems . That is not because science has failed, but rather because it has succeeded – it has given us the answers . It has told us about the climate, given us the power of the atom, the ability to create vaccines and vast , vast productive potential. It has taken us beyond the bounds of our tiny, vast planet. What is left is the human component, which we continue to neglect, underfund, and undervalue. We look for scientific solutions to humanistic problems (where our forebears, it must be confessed, often looked for humanistic solutions to scientific problems) and wonder why our wizards fail us. We have all of the knowledge in the world and yet no wisdom.

We would do well to go back to the humanities.

Share this:

Published by Bret Devereaux

View all posts by Bret Devereaux

297 thoughts on “ Collections: The Practical Case on Why We Need the Humanities ”

- Pingback: Collections: How Your History Gets Made – A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry

Specifically in regards to Star Trek, I will note that yes, in the original series, officers are trained in ‘leadership,’ while the training seems to emphasize science more in later series from the 1980s and on.

With that said… It is true that Picard, as a character, may not have had to pass humanities classes to get the Starfleet Academy degree that launched his officer career in-setting. But he is plainly a cultured *man.* He displays deep moral reasoning, he is passionate about and respectful of the arts, he has a strong sense of where his own species stands in the universe and his vision of where it is going- that is to say, a sense of history. So even if he is only formally trained in the sciences, he cannot be imagined as the product of *only* an education in the sciences. Somewhere along the way, he soaked up a lot of the humanities, even if only indirectly.

But then look at later Star Trek captains- Janeway and Archer. Here we see a considerable amount of decay in their depiction. More superficial moral reasoning, respect for the arts that seems more performative and pro forma at least in my opinion. And, at least aboard Janeway’s USS Voyager, there is no real sense that the activities of the ship fit into a broader historical narrative of which the officers are aware. The ship’s mission is purely about survival and travel, not about “why are we out here.”

So we can view this as a sort of progressive shift, the de-humanitization, if you will, of the Starfleet officer. The captain evolving from a rounded figure who may not know as much science as the science officer or engineering as the chief engineer, but whose grasp of an alien culture or ability to make strategic decisions is enhanced by a sense of history and philosophy… Down to an ascended version of (again) the engineer or science officer. Indeed, Janeway IS the science officer of her own ship; the command-track officers are killed in the first episode and Janeway takes command by stepping into the shoes of the dead.

I’m afraid you betray your lack of ST lore. Janeway was the captain of Voyager from the get go. You’ve relied on false memory for your argument. However, regardless of the nitty-gritty problem of getting the details wrong, I think that your passion for humanities has occluded your perspective, which has failed to take into account evidence that contradicts your argument.

Take C. P. Snow’s 1959 Rede Lecture, The Two Cultures as a jumping off point.

Snow discusses humanities versus STEM problem, and in particular the way each perceives the world and the growing divide where one side is unable to comprehend what the other side says. His argument being that the political and social elites are no longer taught science and technology, which effectively makes them modern day Luddites opposed to industrialization. Therefore they’re at a loss to cope with the changes technology is bringing.

This leads to neither side being able to comprehend the other, or finding the points of view expressed nonsensical to their ears; each seeing the other as deluded. ~Snow argues that this leads to the rich failing to comprehend science and technology, while the poor treat science and technology as things equivalent to magic: beyond their comprehension and understanding.

However, the poor experience the benefits that science and technology bring, and are affected by the social changes arising in a visceral way that the rich are insulated from by their wealth.

In short, the rich live their lives with values derived from an arts and literary education where social change is slow. Whereas the poor have to contend with both the benefits and costs from a rapidly changing cultural milieu. Snow argues these social changes will divide populations, and the only thing that can address the problem is better education with a greater emphasis on science.

Therefore, it could be argued the future is not about machines or the advancement science, but rather information about the most valuable of resources, ourselves and what makes us tick.

However, if we are to do this, then we have to embrace the scientific method, put facts before feelings and develop theories that account for our natures, rather than mythologizing the human condition based on beliefs held onto through faith. I’ve said elsewhere on your lovely blog, that unfortunately facts don’t change peoples opinions.

Caveat: T&CA, E&OE; because most people are concrete operational thinkers, and those who develop abstract formal thinking are only able to do so within specific parameters of their specialist training (Piaget).

Arguably, no matter where you go in this world, ultimately people are just people trying to get along..

Coming back to this much later, I freely admit I misremembered details about Captain Janeway of Star Trek: Voyager and its pilot episode. I was, quite simply, wrong . There are reasons I misremembered such an important set of details in that particular context, and I can find them in hindsight, but the reasons are ultimately irrelevant. I goofed.

More broadly, though, I don’t think I’m wrong in the broader observation about Star Trek , which is that Picard represents something of a high water mark for the franchise in terms of the idea that a Starfleet officer’s aspiration should be towards culture, philosophy, and history of the Federation and those it encounters, as much as to technology and the physicality of space.

To be fully fair to Star Trek , it’s tricky to come up with a convincing three-dimensional character who’s more cultured than Picard without being entirely focused on culture to the exclusion of other activities. One would face similar troubles creating a successor character noticeably braver than Worf or more compassionate than Counselor Troi from the same series. Picard is a tough act to follow in some ways. Note that confronted with a similar problem in TNG itself (“how do we follow Kirk’s act”), the creators quite sensibly didn’t try. They created Picard, who’s a respectable captain but so different from Kirk that neither can be seen as a lesser version of the other, and Riker, who’s a bit more like a lesser Kirk, but who also has the less “spotlight” role of first officer and so can afford to be a little less impressive than another series’ captain.

And to be further fair, I don’t feel qualified at all to comment on the most recent Star Trek series that have come out ( Discovery, Lower Decks while we’re at it, and most notably for what I’m saying, Picard ).

As regards the general thesis of the post I’m replying to, about broader historical trends, I would note that Snow was presenting The Two Cultures in 1959. Of necessity, he was referencing back to social trends observed in the 1950s and earlier, and within the context of specifically the British class system he’d grown up with and lived his adult life in. After all, Charles Percy Snow, recently created Baron Snow as of the time of his speech, was born in 1905, in a world very different from the one we now occupy.

To him, the problem of the Victorian-era focus on a very specific and stilted type of humanities education (poetry memorization, Greek and Latin for everyone, and the sort of inapplicable cramming-focused education memorably mocked in I Am The Very Model Of A Modern Major General ) carrying over into the education of the then-dominant elites of Great Britain (most of whom would have been born during or before the First World War at the time) and leading them to ignore the advances created by “rude mechanicals” must have seemed very real.

We don’t live in his world anymore.

I would argue that whatever may have been the case in Britain c. 1930-1960, in America c. 1990-2020, and in many other parts of the developed world, the problem has changed. The trouble is not that the “classical” elites with their humanities education have walled out the scientists, and merely educating the public in science more fully is not enough to address the matter. I would argue that on the contrary, the problem is that elites whose education focuses almost entirely around law and business management have pushed aside both the humanities and the sciences, except insofar as the sciences can be used to make money.

“Aside from my profound uncertainty as to the accuracy of this claim”

Not to mention many of the riots were sparked by police misbehavior on the spot. When police behaved themselves, so did protesters.

> Within the context of American history, it is fairly close to true to say “only blacks were enslaved.”

Or if you want to get complicated, there’s Indian slavery. Charles Mann says early South Carolina exported lots of Indians as slaves to work in Caribbean islands. Not to mention forced labor through the Spanish Americas, from Columbus to California missions. Supply didn’t keep up though, thus the turn to Africans. (Who brought malaria and yellow fever to the Americas, inadvertently increasing their own relative advantage as laborers, since they had more immunity than anyone else.)

>What a student in these classes is – or at least, ought to be – doing is practicing a form of considered decision-making: assessing the evidence in a way that banishes emotion and relies on reason (which is why we encourage students to write plainly and clearly, without too much rhetorical flourish), and then explaining that reasoning and evidence to a third partly clearly and convincingly.

>What is being taught here is thus a detached, careful form of analysis and decision-making and then a set of communication skills to present that information.

Just to clarify here, are you saying this is something that is the product of studying the humanities, but not a product of non-humanities courses?

If not, then this point boils down to ‘humanities courses also offer SOME of the benefits of stem courses’, which seems like a pretty thin argument in defense of their continued funding.

If, on the other hand, you’re saying that STEMs do not involve careful, impartial and detached analysis based on data, and then communicating the information to others in a precise understandable way, then you’ve defined STEM topics so narrowly as to exclude research publications. All scientific research is a conversation.

>In the meantime, it seems to me no accident that as the funding for the humanities, and the social importance placed on a broad humanistic education, has dwindled, it has produced a matching decline in the richness of our cultural products that at this point has been broadly noticed: more and more sequels or remakes of things that aren’t even very old yet; the same handful of properties and themes flogged to death with precious little in the way of innovation.

This is a pretty weak argument as well; look at 1920’s cinema and you’ll see tons of sequels and adaptations, to the point where even contemporary newspaper comics have numerous complaints about the plague of poor adaptations. So cinema, at least, has always done it. Go back a century further, and stories that were popular with the general public, like “Varney the Vampire” don’t reflect any sort of lost cultural era of literary innovation.

You say the sequel/remake problems started happening in the 1950’s, though. Over the course of 1935-1948, Universal put out SEVEN sequels to Frankenstein (which was, of course, an adaptation of the play from four years earlier, which was itself an adaptation).

But, as you’re the one touting that reasoning based on evidence is the benefit of the humanties education you received, I’d love to see your work. I assume you’ve put your money where your mouth is and have done an actual analysis rather than going off your ‘gut feeling’?

Overall, however, the biggest issue I have is that your post – as such – is structured with the implicit assumption that people with scientific training should be ruled over by those without. You either state, or heavily imply, that mathematicians are incapable of making ethical decisions, that scientists are incapable of asking bigger questions, and that the problem with our covid response is not that the people organizing this scientific project are scientifically illiterate, but that the *wrong* scientifically illiterate people are in charge.

The critical distinction here isn’t between people educated in STEM fields and people educated in the humanities. It’s between people educated in the humanities and people not.

The average physicist has more training in the humanities than the average non-physicist, after all. And the average sociologist has more training in STEM fields than the average non-sociologist. Most people are not any kind of academic.

People, including scientists, are going to be ruled over by some group of people. And it’ll be better for everyone if that group is well-versed in history, sociology, law, economics, philosophy, and language. So the humanities are necessary.

Though it is worth noting that some of the stuff a leader should know is generally considered STEM. Statistics and environmental science, notably.

If, on the other hand, you’re saying that STEMs do not involve careful, impartial and detached analysis based on data, and then communicating the information to others in a precise understandable way, then you’ve defined STEM topics so narrowly as to exclude research publications. All scientific research is a conversation.

I notice that you said “data” whereas Bret said “evidence”. Data is a kind of evidence, of course, but it’s not the only kind, nor does a facility with handling data equate to facility with handling other kinds of evidence.

I’ve wondered how much history might have changed if someone had the idea of representative democracy back in ‘ancient’ times. Seems to me that they didn’t have an idea of something that could scale the way the early US did — spanning 800×1000 miles with no communication better than the printing press and maybe the occasional pigeon. (I.e. well before the railroad or electric telegraph or even the US pony express.)

“political decisions have to be made by a smaller group of people.”

With a large population, the deliberation and detailed decisions have to be made by a small group; the people at large can still approve or strike down proposed decisions once spelled out. Modern Switzerland uses this: a conventional legislature writes laws, but it can be put to popular referendum within a few months if enough people object. I’ve often imagined a system where changes to the criminal or tax laws automatically have to go to referendum.

- Pingback: Fireside Friday, August 28, 2020 – A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry

- Pingback: Fireside Friday, October 30, 2020 – A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry

- Pingback: Fireside Friday: January 1, 2021 – A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry

Faith in Humanities restored! Very compelling post, which shows what it says by doing it.

- Pingback: Collections: The Universal Warrior, Part III: The Cult of the Badass – A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry

>the study of the humanities creates a certain level of diffused knowledge in the society that is available to everyone.

You go on to and talk about Rock&Roll and Hollywood. How they made the Soviet Union collapse. These are greatly limited by copyright law, itself an extension of patent law. The idea behind patent law was that it would grant an inventor a period of exclusive use, and later it would expire and it would enrich public domain.

It is now common for copyright to last 70 years after the death of the writer or artist. And that can be extended on a case by case basis. It is often enough to make a work irrelevant. Lord of the Rings was first published in 1954, 67 years ago! LOTR is copyrighted. Peter Jackson’s movies are copyrighted.

The bulk of popular culture, the de facto culture, is not Homer, Machiavelli, Chopin, or even Tom Sawyer. It’s Guardians of the Galaxy, Kanye West, Home Alone, Die Hard, The Witcher, Spiderman, Dr House or Call of Duty. They’re overwhelmingly patented. There’s no common culture. There are cultures and bubbles.

STEM inventors have it easy as they can literally show an invention used by everyone or by a few important people and explain their working principles. They’re tangible. Humanities ‘inventions’ each require an essay to defend. Besides, we live in a post-truth, post-expert era. Anyone can claim anything on the internet, especially if you have a charismatic personality. On youtube, to a regular joe, anti-vaccer looks just as good as a person highly educated in humanities. We can spend hours arguing how much merit there is in Jordan Peterson’s lectures or how much he uses word salad tactic, using language to distance, intimidate and confuse instead of bridging gaps and illuminating. There’s no straightforward (like a mechanical device) way to test which parts of Peterson’s lectures are valuable. Mechanical contraptions can be taken apart into their base mechanisms. You can’t trivially take Rashomon apart and get Citizen Kane. Wise leaders might benefit from illuminating classic works, but that’s hard and time-consuming to prove to a simple citizen.

People aren’t even interested in facts (knowledge) much anymore. They’re happy with opinions. The more radical and emotional, the better.

- Pingback: Meet a Historian: Michael Taylor on Why We Need Classics – A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry

- Pingback: Collections: So You Want To Go To Grad School (in the Academic Humanities)? – A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry

I agree that the typical justification for the humanities is not solid. I wonder if there is value in tracing the genealogy of that justification, because it answers the question “Why should you study the humanities?” not “Why should society value the humanities?” The common justification has a little moralizing in it – you should study humanities because it is a morally good thing to do so. But I wonder if that is because it is the Western Tradition [of the elite], and at the time it was created, it was an essential part of being a good elite. Hence the idea that it is a moral necessity. I think Bret correctly identified that it is not a sufficient justification for society valuing (and government funding of) the humanities.

Corollary: Many historical rulers were smart. Most historical rulers studied humanities. Many smart historical rulers emphasized the study of humanities (as part of my hypothesis above regarding it being a moral good for elites). Thus, there is some good reason to think that humanities have value for rulers. If so, we should educate the rulers of America in humanities. Who are the rulers in a democracy?

I think it’s absolutely critical to address your responses to the actual question asked, and I appreciate Bret making a solid case for actually funding humanities.

Let me make another case, possibly in a similar vein. My background: I went to a liberal arts college, but got degrees in mathematics and biochemistry. However, a couple years out from college, I now work for a major consulting firm.

What does America value? What defines our culture? No moral judgement here, but America is about money. Everything is America is about money. (I had another comment about the driving factor behind movie construction in Hollywood being money, but it was too long so I cut it). I guess I can justify this statement if somebody wants me to, but I honestly feel like it doesn’t need justification. If I’m wrong, let me have it.

Money in America flows to the most valued members of society. I know what you’re thinking: “Programmers! Engineers! Essentially STEM people.” No, it’s their managers. It’s always the managers who get paid. Programmers and Engineers get paid more than most other workers, but managers are the largest people group who makes serious amounts of money. Obviously tech company founders tend to amass enormous assets, but (1) They are a very select group of people, and (2) They usually stop programming and start managing pretty fast. I don’t even think companies are very good at identifying good managers (Although I’m pretty sure most research has indicated that managers with good people skills pretty generally enhances team performance). But they do recognize that managing people is a more valuable skill than technical ability. On the same note, it always amazes me the ridiculous amount money that consulting companies bring in for having so much less technical ability than the big tech companies. My guess is that much of it is based on strong communication and people skills that make clients comfortable with our technology, more so than it is based on superiority of our technology.

The point here is that people are convinced to spend money, not by technology, but rather by techniques designed to appeal to people. No matter how fancy the technological edifices we construct are, they’re still pretty generally all about people. (Facebook and Google run ad networks based on monetizing people’s preferences!)

I feel like I am missing a logical step here, but I think the implication is that if we want any individual person to succeed in attracting money in America, we need that person to understand people. At least in theory, if we want the whole community of Americans to succeed, we need the whole community of Americans to understand people. I think what Bret has pointed out, again and again, is just how radically different, and how constantly the same people are, and how much we need to directly study these samenesses and differences in order to actually understand people.

(I have further thoughts on how STEM will fail to do this – I think businesses in America are a great place to look for the inability of academic STEM to grasp the world with the totality that it typically desires, but this comment is way too long already)

Patricia Crone in Pre-Industrial Societies talked about education in elite culture being a way to keep the elite as a coherent elite, despite being thinly spread over a diversity of peasants. Then you can have mass education as part of a nationalist program, to make a ‘nation’ out of the masses. But if your core value is pluralism then it’s hard to tell everyone to read the same books, unless you can do that as part of inculcating the value of pluralism… Or things like democracy; I’ve headcanoned that Bujold’s Beta Colony has a strong education in “why democracy is good” (pointing to things like accountability and Condorcet’s Jury Theorem, not just moralizing) and “how democracies have failed”, along with education in marketing techniques (to inoculate people against them), cognitive biases, etc.

First of all, great post and great blog.

I think 21st century American politics cries out for better humanities education. We see a lot of disadvantaged (by technology, globalization, capitalist system etc.) people unaible to channel their political interests through existing structures and politicians and “thought leaders” unable to find a reasonable approach to meet those needs. 2020 elections and especially what followed is just a symptom, but the one that should have been taken seriously and yet everything is primitivized to bad Trump and treasonous rioters.

It doesn’t mean that the current academic structure is fit for the purpose. The non-humanities solution is to make some semi-random clear break and solve one problem by creating a hundred more. More humanities-informed approach (I am a stem person myself, mind) is to understand that institutions grow and the best way is to give them more resources and to set a clear purpose than to try to micromanage who to hire and how to teach classes.

Two more comments.

Have we absorbed the lessons of WWI? It seems that the world powers are just as capable to walk into a major war through militarism and bricksmanship as 100 years ago and just as unable to and conflicts by negotiation. If anything there is some ability to freeze conflicts (better than keep fighting!) like in the West Bank, Cyprus, Eastern Ukraine. Some smart humanitarians have to help here!

Soviet system didn’t collapse because of Hollywood and rock-n-roll. I never studied the details, but lived through it. Mainly, the majority was disappointed with low living standards as compared to Western consumerism and inability of the sklerotic system to move forward. Just like in Western Europe “socialism didn’t work”, but there was no mechanism to change it (relatively) gently.

- Pingback: Fireside Friday, January 21, 2022 (On Public Scholarship) – A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry

I’m reminded of times, online, when people — college educated people– have said things like, “College education is valuable because it teaches critical thinking.” Usually, just that statement, nothing else supporting it. Which makes the statement ironic, because by failing to provide any evidence for their claim that college improves faculties for critical thought, they are demonstrating the exact opposite of their claim: by making explanations without reason, without evidence, they are showing that they themselves have some significant deficits in critical reasoning.

We see assertions like that throughout this argument. That education in the humanities improves leadership ability over education in other domains or no formal education at all. Where is the evidence?

I don’t agree that humanities and science are inherently different domains, that they use different kinds of evidence, etc. Science has regularly had to use qualitative evidence, as for the identification of Saturn’s rings. As in history, science uses the best kind of evidence it can muster. Where that evidence is not as great as we’d like, which comes often from limitations due to timeframe, ethics, budget, we still do what we can, understanding that we’re not saying definitively– we’re *never* saying definitively. Philosophical descriptions of the “scientific method” have been criticized for ignoring absolutely tons of science. Anthropology is an example that does not typically involve any experiments. I find it humorous that in these comments, sociology is provided as an example of the humanities, when some professors, of science *or* humanities, might take offense at that; nevertheless, I think there’s more than a grain of truth to it. There is no hard border between the sciences and the humanities.

And while our art is definitely inspired by domains studied by the humanities, that is a very different thing than claiming that art is dependent on the humanities. Absent written history, absent literacy itself, people still made art. You’ve demonstrated very well that 300 has nearly no historical basis– yet, it was still made, and it’s still good, in the sense that it’s fun, that it’s enjoyable, and that it’s inspiring, at least, to some people.

There is another defense of the humanities: they are *fun*! Do we study to live, or do we live to study? This may not be convincing to some of the rich people providing funding, but it *should* be. Knowledge, inquiry, is not just an instrument to other values. For many of us, it is a primary value, a good in and of itself. Should it come before lives? Probably not, not in my opinion (but I don’t believe that’s an objectively answerable question), but I think you’d agree with that anyways, that if we are ever making an explicit choice between people surviving and people studying history, that we should probably pick the surviving thing, regardless of the practical benefits of the study of the humanities. Yet, not all choices are between those two, at least, not explicitly.

- Pingback: Fireside Friday, December 23, 2022 (W(h)ither History) – A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry

Thanks for this post! Certainly changed my perspective on the humanities, especially as a mathematician who often hasn’t been able to appreciate the humanities in the past.

I can’t help but think that merely funding the humanities is not enough. What most people want out of college is a better job (e.g. https://news.gallup.com/reports/226457/why-higher-ed.aspx ). And humanities are famous for not really giving good job prospects (law degrees being the exception). For the benefits you’re arguing for to come to fruition, people actually have to choose humanities. What practical jobs could the humanities train people for?

I can’t help but think the answer is already contained in this blog: content creator. Why couldn’t humanities majors train people to be YouTubers, and bloggers, and podcasters, and influencers? Heck, the humanities already trains people to be authors and essayists. But pamphlets and books are no longer the dominant medium of communication. So perhaps the humanities also need to adapt.

History majors actually already do fine in the broader economy – the idea that humanities degrees don’t have good job prospects is a myth. See: https://www.historians.org/teaching-and-learning/why-study-history/careers-for-history-majors/what-can-you-do-with-that-history-degree and https://www.historians.org/research-and-publications/perspectives-on-history/april-2017/history-is-not-a-useless-major-fighting-myths-with-data

With respect, my graduating class (2009) fared very poorly and humanities majors took the brunt of the unemployment and underemployment, with engineers and economics majors weathering the storm. Those who doubled down and went on to pursue a PhD in a humanities discipline, reasoning that the job market would improve by the time they graduated, instead faced a collapsing academic job market by the time they completed their doctorates. Those who braved years of underemployment to carve out some sort of niche generally did better than those who had chosen the PhD route.

I studied history and found it immensely fulfilling. My fiancée studied philosophy. We are now both software engineers, her by way of a masters degree and myself by way of self study. It is undoubtedly true that our humanities backgrounds aid our careers in small ways, yet this is insufficient to justify them, because our careers would not be possible with a humanities degree alone. An undergraduate degree is an immense investment and it is reasonable to expect a return on that investment. Given the staggering costs of higher education, assessing a field of study on the basis of whether its graduates are able to achieve any gainful employment at all is wholly inadequate.

Several of my friends who have backgrounds in the humanities, including graduate degrees, subsequently transitioned to software engineering and found the first stable, well paid work with good benefits in their careers through doing so. The foreign language and research skills they acquired through their academic training have little bearing on their present employment.

I continue to read academic history today; I even audited Timothy Snyder’s survey course on the history of Ukraine last fall, doing all of the reading (several books!) and watching all of the lectures. I also continue to pursue several of my other undergraduate interests, such as rock climbing and hiking. I find all of these activities enriching and worthwhile. None of these things pay the bills, however. Knowledge of Python, Rust, and Linux do so.

I support funding the humanities as a matter of policy, because I think exposure to the humanities (history in particular) is critical to fostering the sort of informed critical thinking that is imperative in a democracy and because the production of valuable scholarship requires academic infrastructure and support. That said, if someone asked me whether they should major in a humanities discipline as an undergraduate, I would simply say: don’t do it. It pains me to say this, but I think it needs to be said.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from a collection of unmitigated pedantry.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

College of Liberal Arts & Sciences

Humanities at Illinois

Why studying the humanities matters, why study the humanities, the world needs humanists.

In a world that’s increasingly automated, people who can use words effectively are vital to building relationships and perceiving new possibilities. Countless leaders agree—for example, Steve Jobs has mentioned that "it's in Apple's DNA that technology married with liberal arts married with the humanities yields the result that makes our heart sing."

When you graduate with a humanities degree , you'll have a skill set that employers are actively looking for—humanities students gain expertise in creative thinking, communication, problem solving, relationship building, and more. No matter what you want to do, choosing a humanities major from the University of Illinois will prepare you for a bright future.

Hear from English and Latina/Latino studies alumna Issy why humanities education is important for all students, read on to learn more, and then apply to a humanities major at the University of Illinois.

What are the humanities?

What is the study of humanities ? Humanities involve exploring human life's individual, cultural, societal, and experiential aspects. Studying humanities helps us understand ourselves, others, and the world. If you're interested in humanities, you'll find a variety of subjects to choose from.

The objects of the humanities are the values we embrace, the stories we tell to celebrate those values, and the languages we use to tell those stories. The humanities cover the whole spectrum of human cultures across the entire span of human history.

The College of LAS offers dozens of humanities majors , so as a student at UIUC you're sure to find a path that's right for you. Many of your classes will be small enough to allow intense, in-depth discussion of important topics, guided by teachers who are leading experts in their fields. You will learn from people who know you and take a personal interest in your success. This experiential, interactive learning is deeply satisfying, a source of enjoyment that is one good reason to major in the humanities.

What you learn also will be useful in any career you pursue. Specialized training for a specific profession has a very short shelf life, but the knowledge and skills that come with studying the humanities never go out of date.

To study the humanities is to cultivate the essential qualities you will need in order to achieve your personal and professional goals as you help to create a better society for all human beings.

Why are the humanities important?

Studying the humanities allows you to understand yourself and others better, offering better contexts to analyze the human experience.

So, why is humanities important, and why is it critical to study them? Human values are influenced by religion, socioeconomic background, culture, and even geographical location. The humanities help us understand the core aspects of human life in context to the world around us.

The study of humanities also helps us better prepare for a better future. They teach you skills in the areas of critical thinking, creativity, reasoning, and compassion. Whatever your focus, you'll learn the stories that shape our world, helping you see what connects all of us!

W hat is humanities in college ? What will your courses look like? Just a few popular humanities majors include English, philosophy, gender studies, and history. And while these studies might center around different topics, settings, and even periods in human history, they all share a common goal of examining how we are connected.

Humanities studies may seem less concrete than STEM studies, and some might consider them a luxury we can't afford in a culture that values capital over society. This raises some common questions: Why is humanities important right now? Is it even relevant to our lives today? The answer to those questions lie in how the humanities help us in understanding human culture , emotions, and history—which is vital now more than ever!

As technology advances—such as with artificial intelligence and machine learning becoming more common—it might seem like human beings are becoming less central to the world's workings. That may lead to asking, "why is humanities important if humans are required less in day-to-day operations?" The reality, though, is that rapid changes and development in our world only make the constant aspects of human nature more crucial to explore and celebrate. A deep understanding of humanity gained by studying the humanities helps us not only navigate but also thrive through these changes. The humanities are vital to preserving the core of what makes us human.

So, why study humanities?

What is the study of humanities going to do for my career? Why is humanities important for my work ?

These are two questions commonly asked when students consider an academic journey in the humanities. The journey from classroom to career may not seem as direct for humanities students as those following more defined career paths. However, it’s that nebulous nature that make them such excellent choices. The skills you learn from your studies, like creative thinking, emotional intelligence, and communication, are essential to any career and industry.

And if you are asked, "What is humanities studies ' advantage compared to more 'concrete' subjects like math or science?," you can simply answer that the humanities make you stand out. Employers highly value the nuanced skills gained from humanities studies . In today's rapidly evolving job market, the ability to think critically, communicate effectively, and understand complex social and cultural contexts can set candidates apart.

Ready to take the next step?

You’ll be ready for any future you can imagine by earning a degree in the humanities from the University of Illinois. Apply to a humanities major today!

April 14, 2024

published by phi beta kappa

Print or web publication, why we need the humanities.

The word itself contains the answer

A little over five years ago, a pair of huge, exquisitely crafted L-shaped antennas in Louisiana and Washington State picked up the chirping echo of two black holes colliding in space a billion years ago—and a billion light years away. In that echo, astrophysicists found proof of Einstein’s theory of gravitational waves—at a cost of more than $1 billion. If you ask why we needed this information, what was the use of it, you might as well ask—as Ben Franklin once did—“what is the use of a newborn baby?” Like a newborn’s potential, the value of a scientific discovery is limitless. It cannot be calculated, and it needs no justification.

But the humanities do. Once upon a time, no one asked why we needed to study the humanities because their value was considered self-evident, just like the value of scientific discovery. Now these two values have sharply diverged. Given the staggering cost of a four-year college education, which now exceeds $300,000 at institutions like Dartmouth College (where I taught for nearly 40 years), how can we justify the study of subjects such as literature? The Summer 2021 newsletter of the Modern Language Association reports a troubling statistic about American colleges and universities: from 2009 to 2019, the percentage of bachelor’s degrees awarded in modern languages and literature has plunged by 29 percent. “Where Have All the Majors Gone?” asks the article. But here’s a more pragmatic question: what sort of dividends does the study of literature pay, out there in the real world?

Right now, the readiest answer to this question is that it stretches the mind by exposing it to many different perspectives and thus prepares the student for what is widely thought to be the most exciting job of our time: entrepreneurship. In William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, the story of how a rural Mississippi family comes to bury its matriarch is told from 15 points of view. To study such a novel is to be forced to reckon with perspectives that are not just different but radically contradictory, and thus to develop the kind of adaptability that it takes to succeed in business, where the budding entrepreneur must learn how to satisfy customers with various needs and where he or she must also be ever ready to adapt to changing needs and changing times.

But there’s a big problem with this way of justifying the study of literature. If all you want is entrepreneurial adaptability, you can probably gain it much more efficiently by going to business school. You don’t need a novel by Faulkner—or anyone else.

Nevertheless, you could argue that literature exemplifies writing at its best, and thus trains students how to communicate in something other than tweets and text messages. To study literature is not just to see the rules of grammar at work but to discover such things as the symmetry of parallel structure and the concentrated burst of metaphor: two prime instruments of organization. Henry Adams once wrote that “nothing in education is more astonishing than the amount of ignorance it accumulates in the form of inert facts.” Literature shows us how to animate facts, and still more how to make them cooperate, to work and dance together toward revelation.

Yet literature can be highly complex. Given its complexity, given all the ways in which poems, plays, and novels resist as well as provoke our desire to know what they mean, the study of literature once again invites the charge of inefficiency. If you just want to know how to make the written word get you a job, make you a sale, or charm a venture capitalist, you don’t need to study the gnomic verses of Emily Dickinson or the intricate ironies of Jonathan Swift. All you need is a good textbook on writing and plenty of practice.

Why then do we really need literature? Traditionally, it is said to teach us moral lessons, prompting us to seek “the moral of the story.” But moral lessons can be hard to extract from any work of literature that aims to tell the truth about human experience—as, for instance, Shakespeare does in King Lear . In one scene of that play, a foolish but kindly old man has his eyes gouged out. And at the end of the play, what happens to the loving, devoted, long-suffering Cordelia—the daughter whom Lear banishes in the first act? She dies, along with the old king himself. So even though all the villains in the play are finally punished by death, it is not easy to say why Cordelia too must die, or what the moral of her death might be.

Joseph Conrad once declared that his chief aim as a novelist was to make us see. Like Shakespeare, he aimed to make us recognize and reckon with one of the great contradictions of humanity: that only human beings can be inhumane. Only human beings take children from their parents and lock them in cages, as American Border Patrol agents did to Central American children two years ago; only human beings burn people alive, as ISIS has done in our own time; only human beings use young girls as suicide bombers, as Boko Haram did 44 times in one recent year alone.