Political Persuasion: Creating and Engaging Your Audiences

Every political campaign or organization wants to convince and mobilize enough voters to win their election or advance their organization’s cause. However, convincing voters to support your campaign or cause is not an easy task. While political persuasion is a valuable tool for campaigns and causes to assemble the support they need to win, it’s a time-consuming practice that requires effective communication and voter targeting to execute it well. In this blog, we will define political persuasion, the types of voter audiences you may want to target in your persuasion universe, and how you can engage with those voters effectively with tools from NGP VAN.

Watch our webinar below on Creating and Engaging Political Persuasion Audiences!

What is Political Persuasion?

Political persuasion is the art of convincing voters to support your campaign. It’s a valuable tactic for many campaigns and causes that may not be able to win their race without convincing unlikely supporters to support their efforts. Creating a persuasion universe is necessary when there aren’t enough likely supporters to hit your win number or you want to expand your margin of victory in the upcoming election. Political persuasion is particularly effective for a few groups of voters that you can easily target in VAN. But first, let’s describe the differences between persuasion and mobilization.

Is Political Persuasion Different from Political Mobilization?

While political persuasion is focused on convincing voters to support your campaign, political mobilization focuses on getting identified and likely supporters out to vote. Some may only execute mobilization efforts because they have a comfortable margin of identified and likely supporters for their campaign or cause, but that’s not the case everywhere.

Political persuasion differs from mobilization in more than just its ultimate goal. It also requires more planning and message development, more communications and “touches” (contacts with voters), and savvier communicators. As we mentioned before, these audiences will likely need different messages served to them to convince them to support your campaign. For instance, messaging that works well with voters who don’t know you may not work well with voters of different political parties. Your persuasion universe will likely require more communications (or “touches”) to secure their support than your mobilization universe. Finally, communicating with your persuasion audience typically requires savvy communicators who can adapt and address issues that this audience may raise. It’s also beneficial to find trusted volunteers who can communicate respectfully with those who have different opinions than their own.

What Is a Persuasion Universe?

With those differences in mind, we can now share the audiences that may be most effective to include in your persuasion universe. A persuasion universe is the group of voters you will contact to convince them to support your campaign or cause. However, this group of voters will not be as likely to support your campaign as your mobilization universe (which is composed of likely and identified supporters).

Types of Voter Audiences for Persuasive Politics

Several voter audiences may be potential targets for your persuasion universe. To target these groups effectively, you will want to serve them different messages to convince them to support your campaign or cause. Here are three common groups that may need to be in your persuasion universe.

People Who Do Not Know Your Campaign or Cause Yet

These people may not know who you are, but they may support you once they learn more about you and where you stand on the issues.

Members of Another Political Party

While these people are unlikely to support your campaign or cause, there are likely some of them that may be upset with the direction of their political party, the candidate who is running on their party’s ticket, or another factor that may present you an opportunity to convince them to support your campaign or cause or just not vote for your opponent or opposing cause.

People Who Are Not Likely to Support Your Campaign or Cause

While some of these people may fall into one of the other groups we discuss here, some may not be likely to support your campaign or cause due to a stance on a particular issue or some other factor. While these voters may be more difficult to target, they may be another valuable persuasion audience to engage with.

Creating Your Persuasion Universe

VAN makes it easy to create your persuasion universe through several scores and other targeting parameters. You can use ideology or support scores and past voting history to find a group of voters that will be critical to your campaign or organization’s success. Your persuasion universe will be unique to your campaign or organization, but you should understand how many voters you must convince to win your race. Once you have that determined, you can build your persuasion universe to meet or exceed that number to set your campaign or cause up for success.

Identifying Supporters In Your Persuasion Universe

As you begin your outreach to your persuasion universe, you will want to gather a Supporter ID score that you can use for outreach later in the campaign. Campaigns will usually create a Supporter ID Survey Question with responses from 1 to 5 (1 indicating strong support for your campaign or cause and 5 indicating strong opposition to your campaign or cause). Once you progress through contacting your persuasion universe and gather more data, you can better understand how you are advancing towards your win number. You will then add those supporters (those marked as a 1 or 2) into your mobilization universe. Depending on how many supporters you identified in your first pass and how much time is left in the election cycle, you will likely need to make another pass through your persuasion universe to those who you were unable to contact during the first pass, undecided voters, and those who are leaning towards supporting your opponent or opposing cause (those marked as a 3 or 4).

Unique Benefits of Campaign Channels for Political Persuasion

The best channels for political persuasion are those through which you can have one-on-one conversations with voters either in-person or over the phone. However, there are a few other methods that may have varying levels of success. After creating your persuasion universe in VAN, you can determine what areas may be ideal for canvassing and phone banking based on their geographic spread. Ideally, you’d be able to contact this universe multiple times through several channels. But to start, you may want to canvass in areas of higher voter density and make calls in areas with lower voter density.

Canvassing with MiniVAN

Door-to-door canvassing is one of the most effective channels to employ political persuasion. With our mobile canvassing app, MiniVAN, your campaign or cause can easily guide volunteers’ conversations with voters, record valuable data, and sync it instantly back to VAN to act on later in the campaign. MiniVAN even offers the ability to use branched scripts that offer different questions and prompts based on a voter’s answers. Additionally, MiniVAN allows you to choose a default script and up to four alternates to give your canvassers up to five scripts to employ, or you can choose a default script and alternate scripts based on a target’s subgroup.

Phone Banking with OpenVPB

Phone banking is another effective method to contact voters in your persuasion universe. Similarly to MiniVAN, OpenVPB now allows users to create phone banks that can map different scripts to different people and allow callers to toggle between scripts.

Other Methods Phone Banking with OpenVPB

While one-on-one conversations allow campaigns and causes to address concerns or issues from your persuasion universe, other broader contact methods may play a role in convincing voters to support your campaign or cause. For instance, some voters may value endorsements from elected officials or advocacy groups , digital ads that communicate why you’re the better candidate for the job, or something else to determine how they’ll vote in an upcoming election.

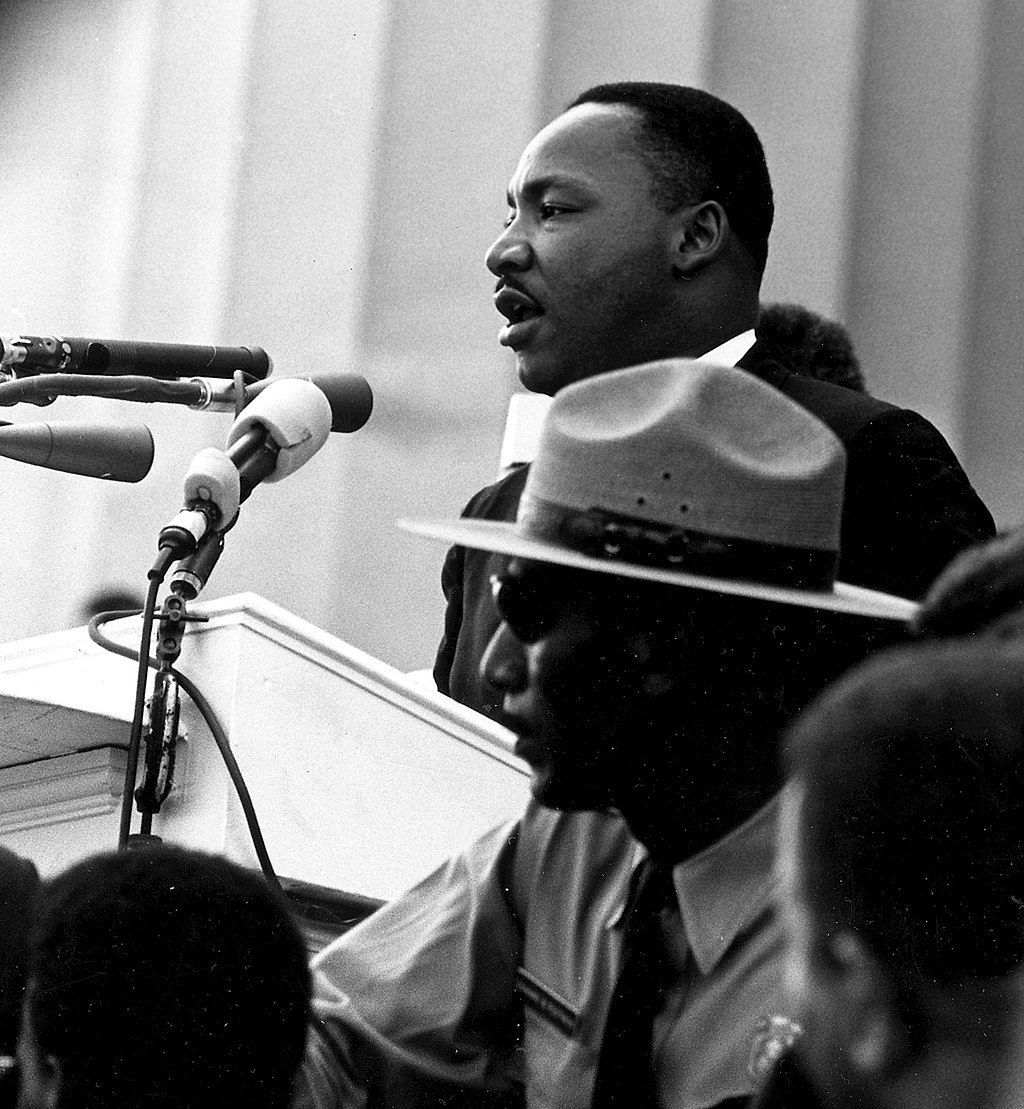

What Purpose Might a Persuasive Political Speech Serve?

Persuasive political speeches may sway some voters to support your campaign, but the impact of these speeches is difficult to measure. Depending on the size of your race, speeches at large rallies may serve as a valuable motivator to drive additional action for your campaign from your supporters. Also, speeches at debates may be a valuable opportunity to convince people to support your campaign or not vote for your opponent because the debate is likely televised or shared with a larger group of potential voters. In other words, while the impact of persuasive political speeches is difficult to measure, in the right circumstances, it may be a valuable opportunity to drive additional action or garner support.

Creating & Engaging Persuasion Audiences with NGP VAN

Through voter targeting in VAN and effective voter outreach through tools like MiniVAN and OpenVPB, you can easily and effectively create and engage with your persuasion audience to help you achieve your campaign or organization’s goals. Get started with NGP VAN today to set your campaign up for success .

Explore more from our blog

Privacy Overview

Communication

iResearchNet

Custom Writing Services

Political persuasion.

Persuasion is an integral part of politics and a necessary component of the pursuit and exercise of power. Political persuasion is a process in which communicators try to convince other people to change their attitudes or behavior regarding a political issue through messages, in an atmosphere of free choice (Perloff 2003, 34). As the field of political communication has grown, so too has the number of studies exploring the processes and effects of political persuasive communication. Political persuasion involves the application of persuasion principles to a context in which most individuals possess the seemingly incompatible characteristics of harboring strong feelings about a host of issues, yet caring precious little about the context in which these issues are played out.

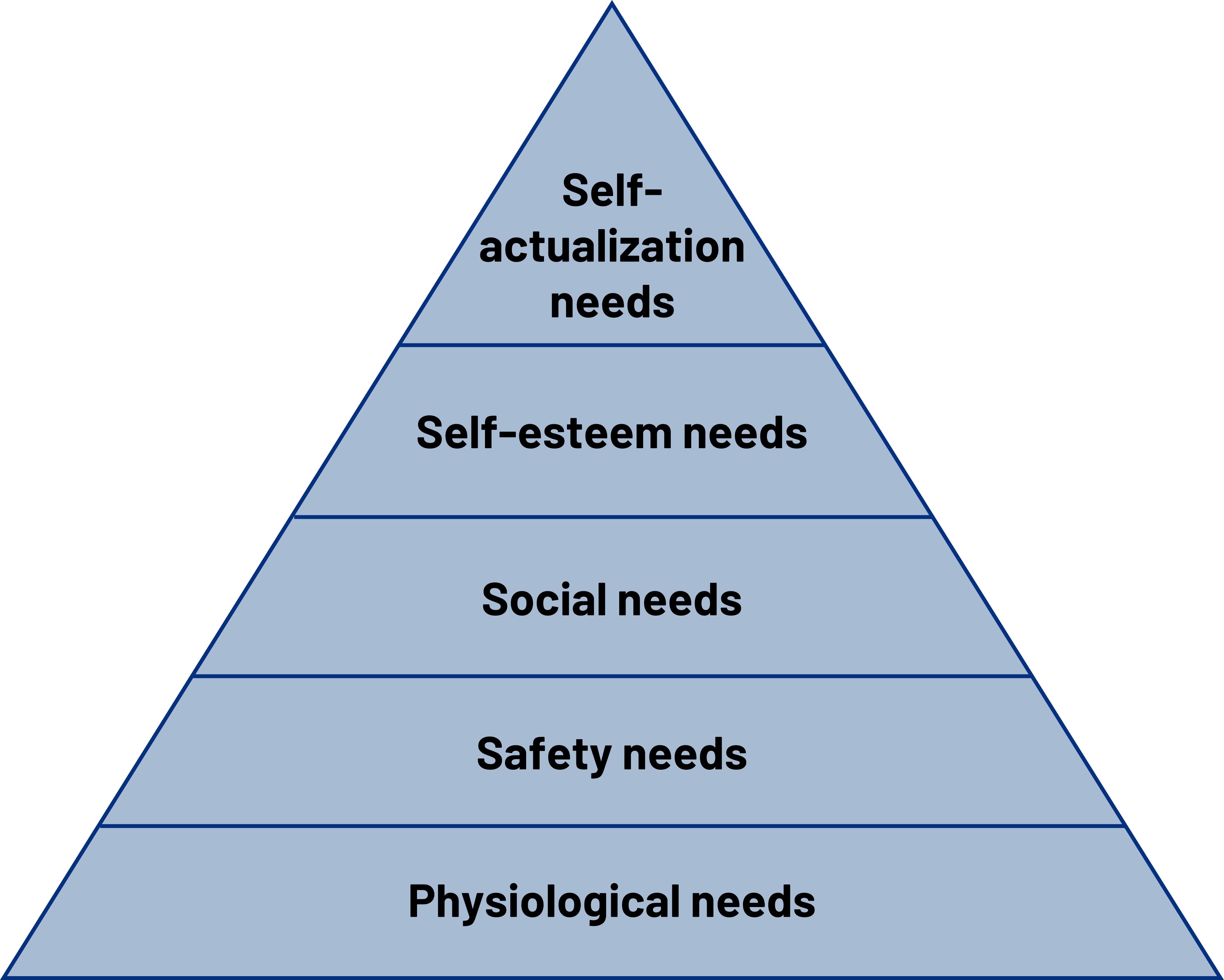

Cognitive Processing

In order to understand political persuasion impact, one must appreciate the processes by which messages achieve their effects). Cognitive processing models such as the elaboration likelihood model (see Petty et al. 2003) emphasize that under low political motivation or ability , voters base decisions on heuristics and are susceptible to cues peripheral to the main message, such as candidate attractiveness, political party labels, endorsements, and even the degree to which political names are repeated or are smooth-sounding. Some researchers argue that in these low-involvement situations, individuals lack political attitudes altogether and therefore can be swayed by factors that are momentarily salient in the political environment, variables that may be of such a transient nature they are devoid of any substantive meaning (Bishop 2005).

By contrast, when individuals are motivated or able to consider political issues, they centrally process message arguments, recalling arguments they perceive to be personally important and thinking through issues, although such thinking is invariably biased by strongly held values or self-interest. In politics, where attitudes and prejudices are formed at an early age, much highly involved processing is biased processing. Consequently, the political persuasion that occurs through debates, advertising, news, and blogs frequently falls under the category of reinforcement, attitude strengthening, or converting attitudes into voting behavior. The vast array of political communications also can change attitudes, frequently subtly and indirectly, as when messages access deeply held values, prime standards for candidate evaluation, and influence the salience of political issues (West 2005).

Levels Of Influence

While researchers generally focus on specific types of political persuasion, we can understand this process more clearly by examining both the direction of influence and the various levels at which this persuasive influence occurs.

If a democratic system is to function efficiently, political persuasion occurs in both directions, bottom-up and top-down. The public must be able to persuade politicians to enact public policies that reflect the will of the people. This persuasion can be expressed by the will of the majority, such as by a mandate in a winning election, but it can also be expressed by the minority, such as in the influence of special interests and lobbyists. Alternatively, the direction of influence can go from political leaders to the public. Politicians must be able to persuade the public to support their agenda of foreign policy, domestic, and legislative initiatives. For example, the government uses various means of political persuasion to persuade the people to support foreign military action, or support new domestic initiatives such as sweeping health-care reform or the privatization of pension provision.

Ultimately, it is the media that are the critical links in this process – regardless of direction – as they transmit carefully crafted messages by government agencies (for example White House propaganda in the war on Iraq; Kellner 2004), convey the strength of public support of policies by reporting public opinion polls (Mutz & Soss 1997), and act as gatekeepers and framers of the daily flow of political news (Williams & Deli Carpini 2000).

Along with direction of influence, we must understand the practice of political persuasion across levels. At the interpersonal level there is ongoing political persuasion occurring within the halls of legislative bodies, where law-makers engage in endless armtwisting of their colleagues while seeking support and votes for legislation. The so-called “Johnson treatment” is a case in point. As a senator in the 1950s, the former US president Lyndon Johnson was particularly effective in gaining the support of his Democratic colleagues by exploiting tactics of persuasive interpersonal communication. In more recent years Johnson’s techniques have been refined through the use of non-stop opinion polls, made famous during the presidencies of Reagan and Clinton.

Political persuasion at the interpersonal level also occurs among individuals, dyads, and groups within the public. This is most apparent during political campaigns as supporters attempt to convert the undecided as well as rally the faithful. The persuasiveness of interpersonal political communication has become more apparent in recent elections as the use of the Internet, including emails and blogs, has been found to be an important means of rallying political support and fundraising (e.g., the Howard Dean 2004 and Barack Obama 2008 presidential campaigns). Internet campaigns by special interest groups have also been found to be effective in spurring letter-writing, phone calls, and emails to members of parliaments to persuade them to vote for particular legislation. In addition, at the intergroup level members of the public participate in political rallies, marches, and protests that can often be effective means of persuading politicians to pay greater attention to specific social causes or legislative issues.

Most research in the area of political persuasion occurs within the context of elections. At the societal level , political advertising has been found to influence the voting decisions and affect the political knowledge of voters in the US (Just et al. 1990). Although derided by critics, negative political ads have been shown to be effective (Perloff 1998). Tactics of persuasion during elections have been practiced and perfected by political consultants (Thurber & Nelson 2000). As inordinate amounts of money are becoming increasingly important in successful political campaigns, candidates and party leaders must persuade donors to make financial contributions. Lastly, throughout the campaign candidates make promises to voters as a means of winning their votes, although means of accountability for broken promises are much less clear.

Converging across levels, attempts at political persuasion by interest groups must continually battle for legitimization from the greater public at large, public officials, and the media. Even as some interest groups find great success in persuading both public and politicians of their message, many other “fringe” groups (e.g., proponents of a 9/11 coverup) may never find their message well received, despite their persuasive attempts.

Media Forms And Frames

Like other forms of political communication, politically persuasive messages are not always truthful and honest, and it is up to media watchdogs and the public to sort out fact from fiction. Politically persuasive messages also take different forms across various media. The goal of films like Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 and Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Political Persuasion Truth is to persuade individuals to support a particular set of political beliefs. In addition, both TV talk shows and talk radio have continued to become more pervasive in the US and other countries, and a myriad of talk-show hosts both entertain and try to persuade their audience that their opinions are right, while also inducing reinforcement effects. Thus, the mediated campaign environment represents the battleground in the fight for the “hearts and minds” of public and elites. Legitimation of message is a crucial aspect of persuasion, and the media are primary sources of political information, whether about candidates or about issues. But the media are not simple conduits for information. Journalistic routines influence what and how news is presented.

How information is framed also affects how it is processed, with what elements it is stored and related in the public’s mind, and ultimately how persuasive it may be. Framing provides the audience with a workable model to interpret complex and often confusing information. In this sense, framing is an extension of agenda setting. Agenda setting was seen as the outcome of journalists’ roles, activities, and values. Hence the media tell us what to think about, if not specifically what to think. Traditionally, this was viewed as a laissez-faire phenomenon, but more recently the setting of the media agenda (and through that the public’s agenda) has been seen as the result of an intention to create the media’s own effects (Lakoff 2004).

But framing is a multilevel phenomenon. Elites and special interest groups attempt to create – or manipulate, depending on your perspective – the public agenda by providing poll-tested linguistic constructions of highly charged political issues. Media, using their own norms and values, select and present information about these issues. The public itself interprets mediated information through its own preconceptions and attitudes.

Initially, framing may be more effective in low-involvement situations, providing simple explanations for events, in line with peripheral processing. Once the frame is set, it can be activated for processing other persuasive messages. Kosicki (2002) argued that framing is consistent with schematic information processing.

Framing operates at both a sociological and a psychological level. When the media present themes that explain basic episodic news (persons and events), there are inherent ideologies, values, and symbols that help to shape context. When individuals use these themes to assess cause and effect, heroes and villains, and right and wrong, the psychological processes are in full play (Iyengar & Simon 1993).

Ambiguity Of Political Persuasion

Ultimately, political persuasion can be best viewed along a continuum – one end anchored in the harmful effects of propaganda, the other in the positive effects of marches and demonstrations leading to civil rights legislation, with a great deal in between. Back in 1922 Walter Lippmann said that the media create a pseudo-reality (Lippmann 1922), but in the age of corporate news media, the “mediation of reality,” in which persuasive messages are delivered by the media, is frequently guided more by purposes such as gaining revenue or influence than by journalistic standards.

Political persuasion remains an ambiguous phenomenon, raising time-honored questions that date back to ancient Greek philosophy. Do political persuasive messages enhance or debase democracy? Do advertisements inform voters about candidates’ positions or mislead them by presenting vacuous statements and feel-good pictures? As campaigns move to the Internet, new questions are emerging, such as whether campaigns will enhance direct communication between leaders and citizens or increase the potential for deception in a milieu unchecked by nonpartisan news media. Theory and research suggest that technology will bring benefits, but also offer new gimmicks in an old game.

References:

- Bishop, G. W. (2005). The illusion of public opinion: Fact and artifact in American public opinion polls . Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Iyengar, S., & Simon, A. (1993). News coverage of the Gulf crisis and public opinion. Communication Research , 20, 363–383.

- Just, M. R., Crigler, A. N., & Wallach, L. (1990). Thirty seconds or thirty minutes: What viewers learn from spot advertisements and candidate debates. Journal of Communication , 40, 120– 133.

- Kellner, D. (2004). Media propaganda and spectacle in the war on Iraq: A critique of U.S. broadcasting networks. Cultural Studies/Critical Methodologies , 4, 329–338.

- Kosicki, G. M. (2002). The media priming effect: News media and conversations affecting political judgments. In J. P. Dillard & M. Pfau (eds.), The persuasion handbook: Developments in theory and practice . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp. 63–81.

- Lakoff, G. (2004). Don’t think of an elephant! Know your values and frame the debate . Chelsea Green. Lippmann, W. (1922). Public opinion . New York: Harcourt Brace.

- Mutz, D. C., & Soss, J. (1997). Reading public opinion: The influence of news coverage on perceptions of public sentiment. Public Opinion Quarterly , 61, 431–451.

- Perloff, R. M. (1998). Political communication: Politics, press, and public in America . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Perloff, R. M. (2003). The dynamics of persuasion: Communication and attitudes in the 21st century , 2nd edn. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Petty, R. E., Wheeler, S. C., & Tormala, Z. L. (2003). Persuasion and attitude change. In T. Millon & M. J. Lerner (eds.), Handbook of psychology . Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, vol. 5, pp. 353–382.

- Thurber, J. A., & Nelson, C. J. (2000). Campaign warriors: The role of political consultants in elections . Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- West, D. M. (2005). Air wars: Television advertising in election campaigns, 1952–2004 , 4th edn. Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly Press.

- Williams, B. A., & Deli Carpini, M. X. (2000). Unchained reaction: The collapse of media gatekeeping and the Clinton–Lewinsky scandal. Journalism , 1, 61–85.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Historian sees a warning for today in post-Civil War U.S.

McCarthy says immigration, abortion, economy to top election issues

Harvard stargazer whose humanity still burns bright

The art of political persuasion.

Christina Pazzanese

Harvard Staff Writer

New research says ‘cognitive dissonance’ helps to ingrain political attitudes

Persuading people to support a particular candidate or party is an essential test of any political campaign. But precisely how to move voters successfully is a matter still not fully understood — and the raison d’etre for political strategists and pundits.

In the fields of economics and political science, conventional wisdom has long held that people generally will act in ways that support their fundamental views and preferences. So, for example, while few observers would be surprised if a lifelong Democrat cast a vote for Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential election, they might not expect a Republican to go against his or her own party affiliation and vote for her.

The idea behind the “rational actor” theory ― that people seek to act in their own self-interest ― sounds perfectly logical. But it fails to explain what causes some voters to change their political views or preferences over time.

Now, political scientists at Harvard and Stanford universities, drawing from longstanding social psychology research, have concluded that a person’s political attitudes are actually a consequence of the actions he or she has taken — and not their cause.

In a new working paper , the researchers say changing political attitudes can be understood in the context of “cognitive dissonance,” a theory of behavioral psychology that asserts that people experience uneasiness after acting in a way that appears to conflict with their beliefs and preferences about themselves or others. To minimize that mental discomfort, the theory posits, a person will adapt his or her attitude to better fit with or justify previous actions.

“There’s a whole host of things going on in social psychology, psychology, and behavioral economics about how humans act and how preferences are formed” that can shed more light on “why politics is the way it is,” said Matthew Blackwell , an assistant professor of government in the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) who co-authored the paper with Maya Sen , an assistant professor of public policy at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), and Avidit Acharya , an assistant professor of political science at Stanford.

The paper offers a new framework for understanding the origin of political attitudes and preferences and how they may change over time, and presents a formal theory about how people adjust their political preferences in order to downplay cognitive dissonance, a theory that has predictive power.

“I think this gives us a lot of insights into how people’s political attitudes come to be formed, and specifically how they change over time,” said Blackwell. “The more we think about these different mechanisms in people’s heads, I think the better we’re going to be able to … figure out what messages are going to work and what strategies are not going to work.”

Blackwell says the findings offer the first formal theory of political attitude change framed within the context of cognitive dissonance, one that could offer new understanding across a range of political behaviors and help answer questions like what causes political partisanship, what drives ethnic and racial animosity, and how empathy with key social ties is so effective in shifting a person’s political views.

The paper was inspired in part by prior research and a forthcoming book project, which examines the long-term impact of slavery on political attitudes in the American South and why white people who live in areas historically active during slavery still hold very conservative and hostile views on race more than 150 years after slavery ended.

In today’s political world, the desire to reconcile cognitive dissonance drives the growing tendency of political candidates to emphasize apolitical qualities such as personality and demeanor while deliberately cultivating vagueness about their policy positions in an effort to minimize cognitive dissonance in voters’ eyes, said Blackwell.

“The less they know about your policies, the less strife they’ll feel in voting for you if they disagree with you,” he said.

The research also suggests that if political parties can get young people to vote for their candidates at an early age, that could “lock in benefits” over the long term. “What we know is that just the act of voting for a candidate seems to increase your affiliation toward that political party over time and makes you a more habitual voter over time,” said Blackwell.

As for the upcoming 2016 presidential race, cognitive dissonance predicts that parties that have a very combative primary season, like the one expected to take place among a vast Republican field, are weakened going into a general election, “not necessarily because of the ‘beleaguered candidate’ or ‘tired candidate’ that we sometimes hear about, but more because there’s a large group of voters who have to reconcile the fact they really vigorously opposed a [primary] candidate and now are being asked to vote for that candidate,” he said. “You have to engage with that cognitive dissonance about whether or not that’s actually a thing you would be able to do.” The big danger for a party is that voters who can’t reconcile their previous support for different candidate might simply sit out the general election.

“This is why you see so much intense management in primary season of endorsements from candidates who dropped out and a lot of rallying the party around a candidate … to make sure that everyone’s on the same page,” said Blackwell. “The longer these primaries go, it could be the case that the more entrenched people’s attitudes become, and it’s harder to dislodge those.”

Share this article

You might like.

Past is present at Warren Center symposium featuring scholars from Harvard, Emory, UConn, and University of Cambridge

Former House speaker also says Trump would likely win if election were held today in wide-ranging talk

Seminar foregrounds Harlow Shapley, who helped scholars escape Nazi rule

Harvard announces return to required testing

Leading researchers cite strong evidence that testing expands opportunity

Yes, it’s exciting. Just don’t look at the sun.

Lab, telescope specialist details Harvard eclipse-viewing party, offers safety tips

For all the other Willie Jacks

‘Reservation Dogs’ star Paulina Alexis offers behind-the-scenes glimpse of hit show, details value of Native representation

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 11 December 2023

The art of rhetoric: persuasive strategies in Biden’s inauguration speech: a critical discourse analysis

- Nisreen N. Al-Khawaldeh 1 ,

- Luqman M. Rababah ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3871-3853 2 ,

- Ali F. Khawaldeh 1 &

- Alaeddin A. Banikalef 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 936 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

3463 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Language and linguistics

This research investigated the main linguistic strategies used in President Biden’s inauguration speech presented in 2021. Data were analyzed in light of Fairclough’s CDA framework: macro-structure (thematic)—intertextually; microstructure in syntax analysis (cohesion); stylistic (lexicon choice to display the speaker’s emphasis); and rhetoric in terms of persuasive function. The thematic analysis of the data revealed that Biden used certain persuasive strategies including creativity, metaphor, contrast, indirectness, reference, and intertextuality, for addressing critical issues. Creative expressions were drawn highlighting and magnifying significant real-life issues. Certain concepts and values (i.e., unity, democracy, and racial justice) were also accentuated as significant elements of America’s status and Biden’s ideology. Intertextuality was employed by resorting to an extract from one of the American presidents in order to convince the Americans and the international community of his ideas, vision, and policy. It appeared that indirect expressions were also used for discussing politically sensitive issues to acquire a political and interactional advantage over his political opponents. His referencing style showed his interest in others and their unity. Significant ideologies encompassing unity, equality, and freedom for US citizens were stated implicitly and explicitly. The study concludes that the effective use of linguistic and rhetorical devices is important to construct meanings in the world, be persuasive, and convey the intended vision and underlying ideologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

A multi-dimensional analysis of interpreted and non-interpreted English discourses at Chinese and American government press conferences

Dandan Sheng & Xin Li

Representations of 5G in the Chinese and British press: a corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis

Jiamin Pei & Le Cheng

No more binaries: a case of Pakistan as an anomalistic discourse in American print media (2001–2010)

Tauseef Javed, Jiandang Sun & Ayisha Khurshid

Introduction

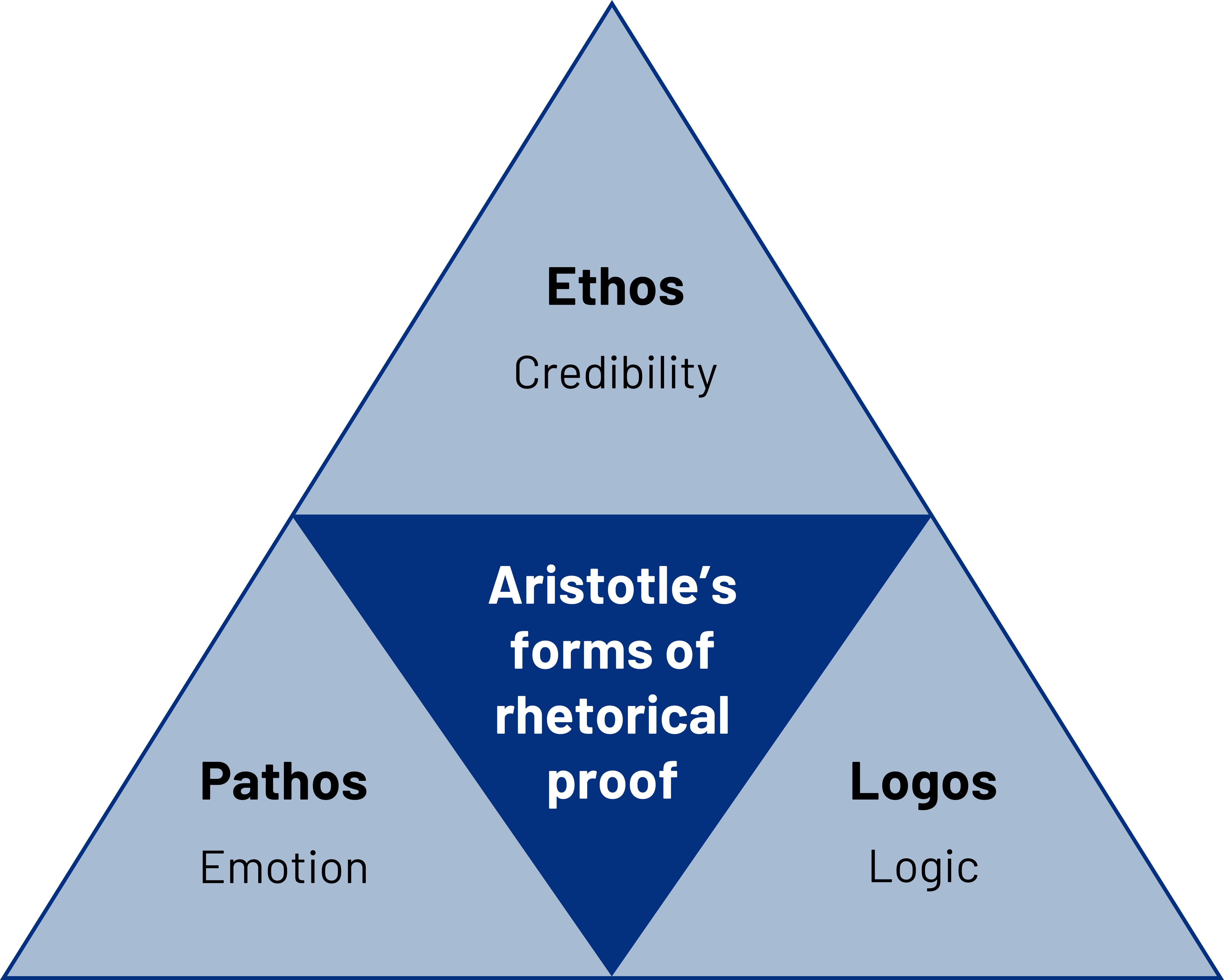

The significance of language in political and academic realms has gained prominence in recent times (Iqbal et al., 2020 ; Kozlovskaya, et al., 2020 ; Moody & Eslami, 2020 ). Language serves as a potent instrument in politics, embodying a crucial role in the struggle for power to uphold and enact specific beliefs and interests. Undeniably, language encompasses elements that unveil diverse intended meanings conveyed through political speeches, influencing, planning, accompanying, and managing every political endeavor. Effectiveness in political speeches relies on meeting criteria such as credibility, logic, and emotional appeal (Nikitina, 2011 ). Credibility is attained through possessing a particular amount of authority and understanding of the selected issue. Logical coherence is evident when the speech is clear and makes sense to the audience. In addition, establishing an emotional connection with the audience is essential to capture and maintain their attention.

Political speech, a renowned genre of discourse, reveals a lot about how power is distributed, exerted, and perceived in a country. Speech is a powerful tool for shaping the political thinking and political “mind” of a nation, allowing the actors and recipients of political activity to acquire a certain political vision (Fairclough, 1989 ). Political scientists are primarily interested in the historical implications of political decisions and acts, and they are interested in the political realities that are formed in and via discourse (Schmidt, 2008 ; Pierson & Skocpol, 2002 ). Linguists, on the other hand, have long been fascinated by language patterns employed to deliver politically relevant messages to certain locations in order to accomplish a specific goal.

Critical discourse analysis (CDA) is a crucial approach for analyzing language in depth so as to reveal certain tendencies within political discourse (Janks, 1997 ). CDA is not the same as other types of discourse analysis. That is why it is said to be “critical.” According to Cameron ( 2001 ), “critical refers to a way of understanding the social world drawn from critical theory” (p. 121). Fairclough ( 1995 ) also says, “Critical implies showing connections and causes which are hidden; it also implies intervention, for example, providing resources for those who may be disadvantaged through change” (p. 9). In short, it can be applied to both talk and text delivered by leaders or politicians who normally have a lot of authority to reveal their hidden agenda (Cameron, 2001 ) and decipher the meaning of the crucial concealed ideas (Fairclough, 1989 ). Therefore, it is a useful technique for analyzing texts like speeches connected with power, conflict, and politics, such as Martin Luther King’s speech (Alfayes, 2009 ). Fairclough concludes that CDA can elucidate the hidden meaning of “I Have a Dream,” the speech that has a strong and profound significance and whose messages concerning black Americans’ poverty and struggle have inspired many people all around the world. The ideological components are enshrined in political speeches since “ideology invests language in various ways at various levels and that ideology is both properties of structures and events” (Fairclough, 1995 , p. 71). Thus, meanings are produced through attainable interpretations of the target speech.

CDA has obtained wide prominence in analyzing language usage beyond word and sentence levels (Almahasees & Mahmoud, 2022 ). CDA, also known as critical language study (Fairclough, 1989 ) or critical linguistics (Fairclough, 1995 ; Chouliaraki & Fairclough, 1999 ), considers language to be a critical component of social and cultural processes (Fairclough, 1992 ; Fairclough, 1995 ; Chouliaraki & Fairclough, 1999 ). The goal of this strategy, according to Fairclough ( 1989 ), is to “contribute to the broad raising of consciousness of exploitative social connections by focusing on language” (p. 4). He also claims that CDA is concerned with studying linkages within language between dominance, discrimination, power, and control (Fairclough, 1992 ; Fairclough, 1995 ) and that the goal of CDA is to link between discourse practice and social practice obvious (Fairclough, 1995 ). The CDA is a type of critical thinking which means, according to Beyer ( 1995 ), “developing reasoned conclusions.” Thus, it might be viewed as a critical perspective and interpretation that focuses on social issues, notably the role of discourse in the production and reproduction of power abuse or dominance (Wodak & Meyer, 2009 ). Furthermore, the ‘Sapir–Whorf hypothesis’ indicates that the goal of critical discourse interpretation is to retrieve the social meanings conveyed in the speech by analyzing language structures considering their interactive and larger social contexts (Fairclough, 1992 ; Kriyantono, 2019 ; Lauwren, 2020 ).

Political communication is generally classified as a persuasive speech since it aims to influence or convince people that they have made the right choice (Nusartlert, 2017 ). Persuasive discourse is a very powerful tool for getting what is needed or intended. In such a type of discourse, people use communicative strategies to convince or urge specific thoughts, actions, and attitudes. Scheidel defines persuasion as “the activity in which the speaker and the listener are conjoined and in which the speaker consciously attempts to influence the behavior of the listener by transmitting audible, visible and symbolic” ( 1967 , p. 1). Thus, persuasive language is used to fulfill various reasons, among which is convincing people to accept a specific standpoint or idea.

Political speeches are considered eloquent pieces of communication oriented toward persuading the target audience (Haider, 2016 ). Politicians often use many persuasive techniques to express their agendas in refined language in order to convince people of their views on certain issues, gain support from the public, and ultimately achieve the envisioned goals (Fairclough, 1992 ). Leaders who control uncertainty, build allies, and generate supportive resources can easily gain enough leverage to lead. This means that their usage of language aims to put their intended political, economic, and social acts into practice. The inaugural speech is a very political discourse to analyze because it marks the inception of the new presidency, mainly focusing on infusing unity among people. In light of the scarcity of research on this significant speech, this study aims to investigate the main linguistic persuasive strategies used in President Biden’s inauguration speech presented in 2021.

Literature review

Political speeches are a significant genre within the realm of political discourse in which politicians use language intentionally to steer people’s mindsets and emotions in order to achieve a specific outcome. Since politics is mainly based on a constant struggle for power among concerned individuals or parties, persuasive techniques are crucial elements politicians use to manipulate others or make them accept their entrenched ideas and plans. Persuasion involves using rhetoric to convince the target audience to embrace certain ideologies, adopt specific attitudes, and control their behavior toward a particular issue (Van Dijk, 2015 ). The inaugural speeches are quite diplomatic and rhetorical, as they constitute a golden chance for the leaders to assert their leadership style. Thus, they are open to different types of interpretations and form a copious source of data for politicians and linguists. The linguistic choices politicians make are rational because of the underlying ideologies that determine the way their speeches should be structured. Considering this idea, it is vital to study the rhetoric of the American presidential inaugural speech since it was presented at a time full of critical political events and scenarios by a very influential political figure in the world, marking the inception of a new phase in the lives of Americans and the world. The significance of studying such a piece of discourse lies in the messages that the new president seeks to deliver to the American nation and the world at large.

Biden’s speeches have attracted researchers’ attention. For example, Renaldo & Arifin ( 2021 ) examined Biden’s ideology evident in his inaugural speech. The analysis of the data revealed three types of presuppositions manifested in his speech, i.e., lexical, existential, and factive, where lexical presupposition is the most frequent one. The underlying ideology was demonstrated in issues regarding immigrants, healthcare, racism, democracy, and climate change.

Prasetio and Prawesti ( 2021 ) analyzed the underlying meanings based on word counts considering three subcategories: hostility, use of auxiliaries, and noun-pronoun discourse analysis. The results revealed Biden’s hope of helping Americans by overcoming problems, developing many fields, and enhancing different aspects. It was evident that his underlying ideology was liberalism and his cherished values were democracy and unity.

Pramadya and Rahmanhadi ( 2021 ) studied the way Biden employed the rhetoric of political language in his inauguration speech in order to show his plans and political views. Each political message conveyed in his inauguration speech revealed his ideology and power. Sociocultural practices that supported the text were explored to view the inherent reality that gave rise to the discourse.

Amir ( 2021 ) investigated Biden’s persuasive strategies and the covert ideology manifested in his inaugural speech. Numerous components including “the rule of three,” the past references, the biblical examples, etc., were analyzed. The results emphasized the strength of America’s heroic past, which requires that Americans mainly focus on American values of tolerance, unity, and love.

Bani-Khaled and Azzam ( 2021 ) examined the linguistic devices used to convey the theme of unity in President Joe Biden’s Inauguration Speech. The qualitative analysis of this theme showed that the speaker used suitable linguistic features to clarify the concept of unity. It revealed that the tone of the speech appeared confident, reconciliatory, and optimistic. Both religion and history were resorted to as sources of rhetorical and persuasive devices.

The review of the literature shows a bi-directional relationship between language and sociocultural practices. Each one of them exerts an influence on the other. Therefore, CDA explores both the socially shaped and constitutive sides of language usage since language is viewed as “social identity, social relations, and systems of knowledge and belief” (Fairclough, 1993 , p. 134). It shows invisible connections and interventions (Fairclough, 1992 ). Consequently, it is significant to disclose such unobserved meanings and intentions to listeners who may not be aware of them.

Despite the plethora of critical discourse analysis research on political speeches, few studies were conducted on Biden’s inauguration speech. Thus, this study aims to enrich the existing research by complementing the analysis and highlighting some other significant aspects of Biden’s inauguration speech. Therefore, it is expected that this study will enrich critical discourse analysis research by focusing mainly on political speech. It can be a helpful source for teachers studying and teaching languages. They will learn how to properly analyze discourses by following a critical thinking approach to fully comprehend the relationship linking individual parts of discourses and creating meaning. Besides, the study casts light on distinctive features of societies manifested in political speech.

Methodology

The present study analyses President Biden’s inauguration speech (Biden, 2021 ). Data were analyzed in light of the CDA framework: macro-structure (thematic)—intertextually; microstructure in syntax analysis (cohesion); stylistic (lexicon choice to display the speaker’s emphasis); and rhetoric in terms of persuasive function. Fairclough’s discourse analysis approach was adopted to analyze the target speech in terms of text analysis, discursive practices, and social practices. The main token and the frequency of the recurring words were statistically analyzed, whereas the persuasive strategies proposed by Obeng ( 1997 ) were analyzed based on Fairclough’s ( 1992 ) CDA mentioned above.

Results and discussion

In the United States, presidents deliver inaugural speeches after taking the presidential oath of office. Presidents use this occasion to address the public and lay forth their vision and objectives. These speeches can also help to unify the United States, especially after difficult times or conflicts. Millions of people in the United States, as well as millions of people throughout the world, listen to the inaugural speeches to gain a glimpse of the new president’s vision for the world. This speech is particularly intriguing to analyze using the CDA framework in many aspects. Fairclough ( 1992 ) emphasizes that language must be regarded as an instrument of power as well as a tool of communication. Actually, there is a technique for utilizing language that seeks to encourage individuals who are engaged to do particular things.

The analysis of the ideological aspect of Biden’s inaugural speech endeavors to link this speech with certain social processes and to decode his invisible ideology. From the opening lines, it is apparent that Biden’s ideology is based on inclusiveness and a citizen-based position. At the beginning of his speech, he uses the first few minutes of his inaugural speech to thank and address his predecessors and audience as ‘my fellow Americans,’ lumping all sorts of nationalities and ethnicities together as one nation.

Biden then continues to mark a successful and smooth transition of power with an emphasis on a citizen-based attitude. He underlines that the victory belongs not only to him but to all Americans who have spoken up for a better life in the United States, saying “We celebrate the triumph not of a candidate, but of a cause. The cause of democracy. The people, the will of the people has been heard and the will of the people has been heeded.” With this victory, he promised to take his position seriously to unify America as a whole, regardless of its diversity by eliminating discrimination and reuniting the country’s divided territories in order to rebuild fresh faith among Americans. People of all races, ethnicities, sexual orientations, faiths, and origins should be treated equally. There is no difference between red and blue states except for the United States. Through this technique, he tries to accentuate that the whole American system depends on grassroots diplomacy, rather than an exclusive system of presidency. The beginning and the end of his speech successfully emphasize the importance of the oath that he took on himself to serve his nation without bias where he begins with “I have just taken a sacred oath each of those patriots took” and reminds the audience of the holiness of this oath at the end of his speech; as he says “ I close today where I began, with a sacred oath ”.

This section is divided into seven parts. Each of these parts analyses the speech in light of the selected persuasive strategies, which are creativity, indirectness, intertextuality, choice of lexis, coherence, modality, and reference. These strategies were selected among others due to their knock-on effect on explicating the core ideas of the speech.

Creativity is an essential part of any successful political speech. That is because it plays a significant role in structuring the facts the speaker wants to convey in a way that is accessible to the audience. It helps political figures persuade the public of their ideas, initiatives, and agendas. Indeed, Biden’s speech abounds with examples of creativity which in turn shapes the policies and expectations he adopts.

By using the expression “ violence sought to shake the Capitol’s very foundation ”. The speaker alluded with some subtlety and shrewdness to the riots made by a pro-Trump crowd that assaulted the US Capitol on Jan. 6 in an attempt to prevent the formal certification of the Electoral College results. Hundreds of fanatics walked onto the same platform where Biden had taken his oath of office, they offended the democracy and prestige of the place and the US reputation. He left unsaid that they were sent to the Capitol by the previous president, and described them in another part of his speech:

Here we stand, just days after a riotous mob thought they could use violence to silence the will of the people, to stop the work of our democracy, and to drive us from this sacred ground.

Biden won the popular vote by a combined (7) million votes and the Electoral College. The election results were frequently confirmed in courts as being free of fraud. Nevertheless, the rioters who attacked the Capitol claimed differently and never completely admitted these results.

The other thing that stood out was Biden’s emphasis on racism. He highlighted the Declaration of Independence’s goals, as he often does, and depicted them as being at odds with reality:

I know the forces that divide us are deep and they are real. But I also know they are not new. Our history has been a constant struggle between the American ideal that we are all created equal and the harsh, ugly reality that racism, nativism, fear, demonization have long torn us apart.

Of all, this isn’t the first time a president has spoken about racism at an inauguration. However, in the backdrop of the (Black Lives Matter) riots and the continued attack on voting rights, Biden’s adoption of that phrase as his own is both strategically and ethically significant. The pursuit of racial justice has previously been mentioned by Biden as a significant government aim. To lend substance to his rhetoric, society will have to take action on criminal justice reform and voting rights.

President Biden also argued that there has been great progress in women’s rights.

Here we stand, where 108 years ago at another inaugural, thousands of protesters tried to block brave women marching for the right to vote. Today we mark the swearing-in of the first woman in American history elected to national office—Vice President Kamala Harris.

In 1913, a huge number of women marched for the right to vote in a massive suffrage parade on the eve of President-elect Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, but the next day crowds of mostly men poured into the street for the following day’s inauguration, making it almost impossible for the marchers to get through. Many women heard ‘indecent epithets’ and ‘barnyard banter,’ and they were jeered, tripped, groped, and shoved. But now the big difference has been achieved. During his primary campaign, Biden promised to make history with his running mate selection, claiming he would exclusively consider women. He followed through on that commitment by choosing a lawmaker from one of the most ardent supporters of his campaign, black women, as well as the fastest-growing minority group in the country, Asian Americans.

On a related note, the president touched on the issue of racism, xenophobia, nativism, and other forms of intolerance in the United States “ And now, a rise in political extremism, white supremacy, domestic terrorism that we must confront and we will defeat .” He stressed that every human being has inherent dignity and deserves to be treated with fairness. That is why, on his first day in office, he signed an order establishing a whole-government approach to equity and racial justice. Biden’s administration talks of “restoring humanity” to the US immigration system and considering immigrants as valuable community members and employees. At the same time, Biden is signaling that the previous administration’s belligerent attitude toward partners is over, that the US’s image has plummeted to new lows, and that America can once again be trusted to uphold its commitments in a clear attempt to heal the rift in America’s foreign relations and rebuild alliances with the rest of the world.

So here is my message to those beyond our borders: America has been tested and we have come out stronger for it. We will repair our alliances and engage with the world once again.

Indirectness

Politicians avoid being obvious and speak indirectly while discussing politically sensitive issues in order to protect and advance their careers as well as acquire a political and interactional advantage over their political opponents. It’s also possible that the indirectness is driven by courtesy. Evasion, circumlocution, innuendoes, metaphors, and other forms of oblique communication can be used to convey this obliqueness. Indirectness is closely connected with politeness as it serves politicians’ agendas by spreading awful stories about their opponents (Van Dijk, 2011 ).

Many presidents have been more inclined to draw comparisons between their policies and those of their predecessors. Therefore, Biden was so adamant about avoiding focusing on the previous president that he didn’t criticize or blame the Trump administration’s shortcomings on the epidemic or anything else. In other words, he does not want to offend Republicans, Trump’s party. When Biden was talking about the attack on the US Capitol by the supporters of Trump, he didn’t mention that Trump had sent them. He talked about the lies of Trump and his followers without naming them, but the idea was clear.

There is truth and there are lies. Lies told for power and for profit” he declared. “Each of us has a duty and responsibility, as citizens, as Americans, and especially as leaders—leaders who have pledged to honor our Constitution and protect our nation—to defend the truth and to defeat the lies.

Of course, such lies were spread not merely by Trump and his horde, but also by the majority of Republicans in Congress, who relentlessly promoted the myth that Trump had won the election. One of the most striking aspects of Biden’s speech is this: while appealing for unity, he admitted that some of his opponents aren’t on the same page as him and that their influence has to be addressed. Biden didn’t use his speech to criticize those who believe his victory was skewed, but he appeared to acknowledge that his plan would be tough to implement without tackling the spread of lies. It was an interesting choice for a man who promotes compromise.

Biden’s speech is enriched with numerous conceptual metaphors and metonymies stemming from various domains. Metaphor is perceived as an effective pervasive technique used frequently in our daily communication (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980 ; Van Dijk, 2006 ). It helps the addressees understand and experience one thing in terms of another. It is closely related to cognition as it affects people’s reasoning and giving opinions and judgments (Thibodeau and Boroditsky, 2011 ). For example, Biden used the metaphor ‘Lower the temperature’ to lessen the tension and chaos caused in the previous presidential period. In another example, he utilized ‘ Politics need not be a raging fire ’ to portray politics as something dangerous and might destroy others.

Biden presents examples of metonymy when he portrays periods of troubles, setbacks, and difficult times as dark winter ‘We will need all our strength to persevere through this dark winter’ to emphasize the gloomy days Americans experience in times of crises and wars. The representation of the concept of ‘unity as the path forward’ implicitly alludes to Biden’s path for the previously created divided America, emphasizing the significance of following and securing the necessary solution, which is unity as the path for moving forward. The depiction of crises facing Americans such as ‘ Anger, resentment, hatred. Extremism, lawlessness, violence, Disease, joblessness, hopelessness’ as foes, make people feel the urgent need to unite in order to combat these foes. The expression of ‘ ugly reality ’ reflects an atrocious world full of problems such as racism, nativism, fear, and demonetization . Integrating such conceptual metaphors and metonymy is conventional and deeply rooted and can lead to promoting ideologies by presenting critical political issues in a specific way (Charteris-Black, 2018 ). They make the speech more persuasive as they facilitate people’s understanding of abstract and intricate ideas through using concrete experienceable objects (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980 ). In other words, they perfectly and politely portray serious issues confronting Americans as well as the course of action required to overcome them. Democracy is depicted as both a precious and fragile object. This metonymy makes people appreciate the value of democracy and encourages them to cherish and protect it. Biden declares that democracy, which has been torn during the previous period, has triumphed over threats. Using this metonymy succeeded in connecting logos with pathos, which is one of the goals of using metaphors in political speeches (Mio, 1997 ).

The metonymy of America as a symbol of good things ‘ An American story of decency and dignity. Of love and of healing. Of greatness and of goodness ’ is deliberately created to represent America as an honest and good country. Through this metaphor, Biden appeals not only to the emotions of all people but also to their minds to persuade them that America has been a source of goodness. This finding supports the researchers’ outcomes (Van Dijk, 2006 ; Charteris-Black, 2011 ; Boussaid, 2022 ) that figurative language reveals how important issues are framed in order to advocate specific ideologies by appealing to people’s emotions. Hence, it is a crucial persuasive technique used in political speeches. This implies that Biden is aware of the significance of metaphor as a persuasive rhetoric component.

Intertextuality

Intertextuality has been defined as “the presence of a text in another text” (Genette, 1983 ). Fairclough claims that all texts are intertextual by their very nature and that they are thus constituents of other texts (Fairclough, 1992 ). It is an indispensable strategic feature politicians employ in their speeches to enhance the strength of the speech and reinforce religious, sociocultural, and historical contexts (Kitaeva & Ozerova, 2019 ). Antecedent texts and names are significant components of rhetoric in politics, especially in presidential speeches, because any leader of a country must follow historical, state, moral, and ethical traditions and conventions; referring to precedent texts is one way to get familiar with them. This linguistic phenomenon is necessary for reaching an accurate interpretation of the text, conveying the intended message (Kitaeva & Ozerova, 2019 ), and increasing the credibility of the text, thus getting the audience’s attention to believe in the speaker’s words (Obeng, 1997 ).

Presidents and political intellectuals in the United States have made plenty of statements that will be remembered for years to come. These previous utterances have been unchangeably repeated by other presidents of the USA in different situations throughout American history and are familiar to all Americans. Presidents of the United States frequently quote their predecessors. Former US presidents are frequently mentioned in the corpus of intertextual instances. The oath taken by all presidents—a set rhetorical act of speech—contains a lot of intertextuality. On a macro-structure level, the speaker utilizes intertextuality to give the general theme an appearance by recalling ‘old’ information. Biden quoted Psalm 30:5: “ Weeping may endure for the night, but joy cometh in the morning .” It is a verse that has great resonance for him, given the loss of his wife and daughter in a car accident and his adult son Beau to cancer. On this occasion, he links it to the suffering, with more than 400,000 Americans having died from COVID-19. This biblical and religious type of intertextuality implies that Biden links people’s intimate connection to God with their social and ethical responsibilities.

Another example is when Biden refers to a saying of President Abraham Lincoln in 1863: “ If my name ever goes down into history, it will be for this act and my whole soul is in it .” Although he leads at a completely different time, much like President Lincoln, Biden is grappling with the challenge of a deeply divided country. Deep political schisms have existed in the United States for a long time, but tensions seem to have been exacerbated lately. These nods to Lincoln bring an element of familiarity back to US politics and, potentially, a sense of return to stability after years of turbulence. The president has also quoted a part of the American Anthem Lyrics. He has recited a few lines of the song that highlight his values of hard work, religious faith, and concern for the nation’s future.

The work and prayers of century have brought us to this day. What shall be our legacy? What will our children say… Let me know in my heart When my days are through America, America I gave my best to you.

Choice of lexis

This choice of lexis may have an impact on the way the listeners think and believe what the speaker says. As Aman ( 2005 ) argues, the use of certain words shows the seriousness of the speech to convince people. Regarding this choice of vocabulary, Denham and Roy ( 2005 ) argue that “the vocabulary provides valuable insight into those words which surround or support a concept” (p. 188).

When you review the entire speech of President Biden, one key theme stands out above all others: Democracy. This was reiterated early in his speech and was repeated several times throughout. He has picked the most under-assaulted ideal: ‘democracy’. This word was used (11) times “We’ve learned again that democracy is precious. Democracy is fragile. And at this hour, my friends, democracy has prevailed,” Biden remarked. This would be evident in another period, but after the 2020 election and the attempt to reverse it, the concept is profound.

The president made lots of appeals to unity in his inaugural speech and ignored the partisan conflicts to achieve the supreme goal of enhancing cooperation between all to serve their country. He repeated the words ‘unity’ and ‘uniting’ (11) times.

And we must meet this moment as the United States of America. If we do that, I guarantee you, we will not fail. We have never, ever, ever, failed in America when we have acted together.

This was Biden’s most forceful call for unity. It would be difficult to achieve, however, not just because of the Trump-supporting Republican Party, but also because of the historically close balance of power in the House and Senate.

Biden’s pledge to bridge the divide on policy and earn the support of those who did not support him, rather than seeing them primarily as political opponents, was a mainstay of his campaign, and it was a major theme of his acceptance speech. “ I will be a president for all Americans .” He also tried to play down the dispute between the two parties (Republican and Democratic) “ We must end this uncivil war that pits red against blue, rural versus urban, conservative versus liberal .” This is evident by addressing his opponents from the Republican Party.

To all of those who did not support us, let me say this:Hear me out as we move forward. Take a measure of me and my heart. And if you still disagree, so be it That’s democracy.That’s America. The right to dissent peaceably, within the guardrails of our Republic, is perhaps our nation’s greatest strength. Yet hear me clearly: Disagreement must not lead to disunion. And I pledge this to you: I will be a President for all Americans. I will fight as hard for those who did not support me as for those who did.

The use of idiomatic expressions is also evident in the speech; Biden says ‘If we’re willing to stand in the other person’s shoes just for a moment’ when talking about overcoming fear about America’s future through unity. This expression encourages the addresses to empathize with the speakers’ circumstances before passing any judgment.

The analysis of syntax helps the addressees sense more specifically cohesion. Within a text or phrase, cohesion is a grammatical and lexical connection that keeps the text together and provides its meaning. Halliday, Hasan ( 1976 ) state that “a good discourse has to take attention in relation between sentences and keep relevance and harmony between sentences. Discourse is a linguistic unit that is bigger than a sentence. A context in discourse is divided into two types; first is cohesion (grammatical context) and second is coherence (lexical context)”.

This was shown with the most frequent form of cohesion for the grammatical section, which is the reference with 140 pieces of evidence. Biden employed a variety of conjunctions in his speech to make it easier for his audience to understand his oration, such as “and” (97) times, “but” (16) times, and “so” (8) times.

The analysis also shows that Biden has used various examples of cohesive lexical devices, repetitions, synonyms, and contrast in order to accomplish particular ends such as emphasis, inter-connectivity, and appealing for public acceptance and support. All of these devices contribute to the accurate interpretation of the discourse. It is evident that Biden used contrast/juxtaposition as in:

‘There is truth and there are lies’; ‘Not to meet yesterday’s challenges, but today’s and tomorrow’s’; ‘Not of personal interest, but of the public good’; ‘Of unity, not division’; ‘Of light, not darkness’; ‘through storm and strife, in peace and in war’, ‘We must end this uncivil war that pits red against blue, rural versus urban, conservative versus liberal’. ‘open our souls instead of hardening our hearts’; ‘ we shall write an American story of hope’ .

The use of juxtaposition makes the scene vivid and enhances the listener’s flexible thinking meta-cognition by focusing on important details drawing conclusions and reaching an accurate interpretation of communication.

The use of synonyms such as ‘ heeded-heard; indivisible-one nation; battle-war; victory-triumph; manipulated-manufactured; great nation-our nation-the country; repair-restore-heal-build; challenging-difficult; bringing America together-uniting our nation; fight-combat; anger-resentment-hatred; extremism-lawlessness-violence-terrorism ’ is evident in Biden’s speech. This type of figurative language helps in building cohesion in the speech, formulating and clarifying thoughts and ideas, emphasizing and asserting certain notions, and expressing emotions and feelings. The results are in line with other researchers’ (Lee, 2017 ; Bader & Badarneh, 2018 ) finding that political speeches are emotive; politicians can express feelings and attitudes toward certain issues. Lexical cohesion has also been established through repetition. The most repeated words and phrases in Biden’s speech are democracy, nation, unity, people, racial justice, and America. The repetitive usage of these concepts highlights them as the main basic themes of his speech.

The speaker employed deontic and epistemic modality, which implies that he has used every obligation, permission, and probability or possibility in the speech to exhibit his power by displaying commands, truth claims, and announcements. The speaker’s ideology can be revealed by the modality of permission, obligation, and possibility.

The usage of medium certainty “will” is the highest in numbers (30) times, but the use of low certainty “can” (16) times, “may” (5) times, and high certainty “must” (10) times was noticeably present. The usage of medium certainty is mainly represented by the usage of “will” to introduce future policies and present goals and visions. In critical linguistics terms, the use of low modality in a presidential address may reflect a lack of confidence in the abilities or possibilities of achieving a goal or a vision. That is, the usage of low modality gives more space to the “actor” to achieve the “goal”. For example, the usage of “can” in “ we can overcome this deadly virus ” and “ we can deliver social justice ” does not reflect strong belief, confidence, and assurance from the actor’s side to achieve the goals (social justice, overcoming the deadly virus). The usage of modal verbs in Biden’s speech reflects a balanced personality.

In modality, by using “will”, the speaker tries to convince the audience by giving a promise, and he may hope that what he says will be followed up. By using “can”, the speaker is expressing his ability. In cohesion, it is well organized, which means the speaker tries to make his speech easier to follow by everyone by using “additive conjunctions” or “transition phrases” that have the function of “listing in order”. Lastly, the generic structure of the speech is well structured.

The use of pronouns in political speeches reveals rich information about references to self, others, and identity, agency (Van Dijk, 1993 ). Biden has used the first and second pronouns meticulously to express his vision. The most frequent pronoun Biden has used is ‘we’ with a frequency of (89) which helps him establish trust and credibility in the speech, and a close relationship between him and his audience. This frequency implies that they are one united nation. Whereas he has used the pronoun ‘ I ’ with a frequency of (32). Using these types of pronouns allows the speaker to convey his ideas directly to his audience and make his intended message comprehensible. This balanced usage of pronouns reflects Fairclough’s ( 1992 ) notion of discourse as a social practice rather than a linguistic practice. The analysis demonstrates that the most prominent themes emphasized by Biden are ‘democracy and unity’. These themes have also been accentuated by the overall dominance of the pronoun “we,” which reflects Biden’s perception of America as a good society that needs to be united to successfully go through difficult times. Such notions represent his policies.

Political speech is functional and directive in its very nature. Thus, the language of politics in inaugural speeches is a significant and unique event since it affects people’s minds and hearts concerning certain pressing issues. It is a powerful tool that newly elected political leaders use to promote their new leadership ideas and strategic plans in order to convince people and attract their support. The analysis of the speech reveals that Biden’s language is easy and understandable. Biden employed a variety of rhetorical features to express his ideology. These figurative devices and techniques include creativity, indirectness, intertextuality, metaphor, repetition, cohesion, reference, and synonymy to achieve his political ideologies; assuring Americans and the world of his good intentions towards uniting Americans and working collaboratively with other nations to persevere through difficult times.

The overall themes expressed in this speech are the timeless values of unity and democracy. They are the cornerstones and key ideological components of Biden’s speech. This value-based orientation indicates their paramount recurrent semantic-cognitive features. The construction of the meaning of such values lies in the sociocultural and political context of the USA and the whole world in general and America in particular. Biden’s speech includes certain ideals, like "unity" to work together for the nation’s development, "democracy" to exhibit the "democracy" that has recently been assaulted, "equality" to treat all American people equally, and "freedom" to let individuals do whatever they want. Such themes are essential, especially in times of the worst crisis of COVID-19 encountering the world since they help him reassure his nation and the world of some improvements and promise them progress and prosperity in the years to come. To sum up, the results showed that the speaker used appropriate language in addressing the theme of unity. The speaker used religion and history as a source of rhetorical persuasive devices. The overall tone of the speech was confident, reconciliatory, and hopeful. We can say that language is central to meaningful political discourse. So, the relationship between language and politics is a very significant one.

The study examined the main linguistic strategies used in President Biden’s inauguration speech presented in 2021. The analysis has revealed that Biden in this speech intends to show his feelings (attitudes), his goals (reviewing the US administration), and his power to take over the US presidential office. It has also disclosed Biden’s ideological standpoint that is based on the central values of democracy, tolerance, and unity. Biden’s speech includes certain ideals, like "unity" to work together for the nation’s development, "democracy" to exhibit the "democracy" that has recently been assaulted, "equality" to treat all American people equally, and "freedom" to let individuals do whatever they want. To convey the intended ideological political stance, Biden used certain persuasive strategies including creativity, metaphor, contrast, indirectness, reference, and intertextuality for addressing critical issues. Creative expressions were drawn, highlighting and magnifying significant real issues concerning unity, democracy, and racial justice. Intertextuality was employed by resorting to an extract from one of the American presidents in order to convince Americans and the international community of his ideas, vision, and policy. It appeared that indirect expressions were also used for discussing politically sensitive issues in order to acquire a political and interactional advantage over his political opponents. His referencing style shows his interest in others and their unity. The choice of these strategies may have an influence on how the listeners think and believe about what the speaker says. Significant ideologies encompassing unity, equality, and freedom for US citizens were stated implicitly and explicitly. The study concluded that the effective use of linguistic and rhetorical devices is recommended to construct meaning in the world, be persuasive, and convey the intended vision and underlying ideologies.

The study suggests some implications for pedagogy and academic research. Researchers, linguists, and students interested in discourse analysis may find the data useful. The study demonstrates a sort of connection between political scientists, linguistics, and discourse analysts by clarifying distinct issues using different ideas and discourse analysis approaches. It has important ramifications for the efficient use of language to advance certain moral principles such as freedom, equality, and unity. It unravels that studying how language is used in a certain context allows people to disclose or analyze more about how things are said or done, or how they might exist in different ways in other contexts. It also shows that studying political language is crucial because it helps language users understand how a language is used by those who want power, seek to exercise it and maintain it to gain public attention, influence people’s attitudes or behaviors, provide information that people are unaware of, explain one’s attitudes or behavior, or persuade people to take certain actions. Getting students engaged in CDA research such as the current study would help them be more adept at navigating and using rhetorical devices and CDA tactics, as well as considering the underlying ideologies that underlie any written piece. Based on the analysis, it is recommended that more research studies be conducted on persuasive strategies in other political speeches.

Data availability

All data analyzed in this study are included in this published article. They are available at this link: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/01/20/inaugural-address-by-president-joseph-r-biden-jr/ .

Alfayes H (2009) Martin Luther King “I have a dream”: Critical discourse analysis. KSU faculty member websites. Retrieved August 28, 2009, from, http://faculty.ksu.edu.sa/Alfayez.H/Pages/CDAofKing’sspeechIhaveadream.aspx

Almahasees Z, Mahmoud S (2022) Persuasive strategies utilized in the political speeches of King Abdullah II: a critical discourse analysis. Cogent Arts Humanit 9(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2022.2082016

Article Google Scholar

Aman I (2005) Language and power: a critical discourse analysis of the Barisan Nasional’s Manifesto in the 2004 Malaysian General Election1. In: Le T, Short M (eds.). Proceedings of the International Conference on Critical Discourse Analysis: Theory into Research, 15–18 November 2005. Tasmania: University of Tasmania, viewed August 20, 2009, from http://www.educ.utas.edu.au/conference/files/proceedings/full-cda-proceedings.pdf

Amir S (2021) Critical discourse analysis of Jo Biden’s inaugural speech as the 46th US president. Period Soc Sci 1(2):1–13

Google Scholar

Bader Y, Badarneh S (2018) The use of synonyms in parliamentary speeches in Jordan. AWEJ Transl Liter Stud 2(3):43–67

Bani-Khaled T, Azzam S (2021) The theme of unity in political discourse: the case of President Joe Biden’s inauguration speech on the 20th of January 2021. Arab World Engl J 12(3):36–50. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3952847

Beyer BK (1995) Critical thinking. Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation, Bloomington, IN