- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

BusinessCycles →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is a Business Cycle?

Understanding the business cycle.

- Measuring and Dating

- Relationship With Stock Prices

The Bottom Line

Business cycle: what it is, how to measure it, the 4 phases.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/headshot1-6c67c442a0684de18fb605c3cd2fb176.png)

Business cycles are a type of fluctuation found in the aggregate economic activity of a nation—a cycle that consists of expansions occurring at about the same time in many economic activities, followed by similarly general contractions. This sequence of changes is recurrent but not periodic.

The business cycle is also called the economic cycle .

Key Takeaways

- Business cycles are composed of concerted cyclical upswings and downswings in the broad measures of economic activity—output, employment, income, and sales.

- The alternating phases of the business cycle are expansions and contractions.

- Contractions often lead to recessions, but the entire phase isn't always a recession.

- Recessions often start at the peak of the business cycle—when an expansion ends—and end at the trough of the business cycle, when the next expansion begins.

- The severity of a recession is measured by the three Ds: depth, diffusion, and duration.

Madelyn Goodnight / Investopedia

In essence, business cycles are marked by the alternation of the phases of expansion and contraction in aggregate economic activity and the co-movement among economic variables in each phase of the cycle. Aggregate economic activity is represented by not only real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) GDP—a measure of aggregate output—but also the aggregate measures of industrial production, employment, income, and sales, which are the key coincident economic indicators used for the official determination of U.S. business cycle peak and trough dates.

Popular misconceptions are that the contractionary phase is a recession and that two consecutive quarters of decline in real GDP (an informal rule of thumb) means a recession. It's important to note that recessions occur during contractions but are not always the entire contractionary phase. Also, consecutive declines in real GDP are one of the indicators used by the NBER, but it is not the definition the organization uses to determine recessionary periods.

On the flip side, a business cycle recovery begins when that recessionary vicious cycle reverses and becomes a virtuous cycle, with rising output triggering job gains, rising incomes, and increasing sales that feedback into a further rise in output . The recovery can persist and result in a sustained economic expansion only if it becomes self-feeding, which is ensured by this domino effect driving the diffusion of the revival across the economy.

Of course, the stock market is not the economy. Therefore, the business cycle should not be confused with market cycles , which are measured using broad stock price indices.

Measuring and Dating Business Cycles

The severity of a recession is measured by the three D's: depth, diffusion, and duration. A recession's depth is determined by the magnitude of the peak-to-trough decline in the broad measures of output, employment, income, and sales. Its diffusion is measured by the extent of its spread across economic activities, industries, and geographical regions. Its duration is determined by the time interval between the peak and the trough.

An expansion begins at the trough (or bottom) of a business cycle and continues until the next peak, while a recession starts at that peak and continues until the following trough.

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) determines the business cycle chronology—the start and end dates of recessions and expansions for the United States. Accordingly, its Business Cycle Dating Committee considers a recession to be "a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales."

The Dating Committee typically determines recession start and end dates long after the fact. For instance, after the end of the 2007–09 recession, it "waited to make its decision until revisions in the National Income and Product Accounts [were] released on July 30 and Aug. 27, 2010," and announced the June 2009 recession end date on Sept. 20, 2010.

The average length of recessions in the U.S. since World War II has been around 11 months. The Great Recession was the longest one during this period, reaching 18 months.

U.S. expansions have typically lasted longer than U.S. contractions. From 1854–1899, they were almost equal in length, with contractions lasting about 25 months and expansions lasting about 29 months, on average. The average contraction duration then fell to 18 months in the 1900–1945 period and 11 months in the post-World War II period. Meanwhile, the average duration of expansions increased progressively, from 29 months in 1854–1899 to 30 months in 1900–1945, 43 months in 1945–1982, and 70 months in 1982–2009.

Stock Prices and the Business Cycle

The biggest stock price downturns tend to occur—but not always—around business cycle downturns (e.g., contractions and recessions). For example, the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the S&P 500 took steep dives during the Great Recession. The Dow fell 51.1%, and the S&P 500 fell 56.8% between Oct. 9, 2007 to March 9, 2009.

There are many reasons for this, but primarily, it is because businesses assume defensive measures and investor confidence falls during contractionary periods. Many events occur before those in an economy are aware they are in a contraction, but the stock market trails what is going on in the economy.

So, if there is speculation or rumors about a recession, mass layoffs, rising unemployment, decreasing output, or other indications, businesses and investors begin to fear a recession and act accordingly. Businesses assume defensive tactics, reducing their workforces and budgeting for an environment of falling revenues.

Investors flee to investments "known" to preserve capital, demand for expansionary investments falls, and stock prices drop.

It's important to remember that while stock prices tend to fall during economic contractions, the phase does not cause stock prices to fall—fear of a recession causes them to fall.

What Are the Stages of the Business Cycle?

In general, the business cycle consists of four distinct phases: expansion, peak, contraction, and trough.

How Long Does the Business Cycle Last?

According to U.S. government research, the business cycle in America takes, on average, around 6.33 years.

What Was the Longest Economic Expansion?

The 2009-2020 expansion was the longest on record at 128 months.

The business cycle is the time is takes the economy to go through all four phases of the cycle: expansion, peak, contraction, and trough. Expansions are times of increasing profits for businesses, rising economic output, and are the phase the U.S. economy spends the most time in. Contractions are times of decreasing profits and lower output, and is the phase the least amount of time is spent in.

St. Louis Federal Reserve. " All About the Business Cycle: Where Do Recessions Come From? "

The National Bureau of Economic Research. " Business Cycle Dating ."

National Bureau of Economic Research. “ Business Cycle Dating Procedure: Frequently Asked Questions. What is a Recession? What is an Expansion? ”

National Bureau of Economic Research. " The NBER's Recession Dating Procedure ."

National Bureau of Economic Research. " Business Cycle Dating Committee, National Bureau of Economic Research ."

National Bureau of Economic Research. " US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions ."

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. " Stock Prices in the Financial Crisis ."

Congressional Research Service. " Introduction to U.S. Economy: The Business Cycle and Growth ," Page 2.

- Depression in the Economy: Definition and Example 1 of 14

- What Is Economic Collapse? Definition and How It Can Occur 2 of 14

- Business Cycle: What It Is, How to Measure It, the 4 Phases 3 of 14

- Boom And Bust Cycle: Definition, How It Works, and History 4 of 14

- Negative Growth: Definition and Economic Impact 5 of 14

- The Great Depression: Overview, Causes, and Effects 6 of 14

- Were There Any Periods of Major Deflation in U.S. History? 7 of 14

- The Greatest Generation: Definition and Characteristics 8 of 14

- A History of U.S. Government Financial Bailouts 9 of 14

- Understanding Austerity, Types of Austerity Measures, and Examples 10 of 14

- The New Deal: Meaning, Overview, History 11 of 14

- The Economic Effects of the New Deal 12 of 14

- Gold Reserve Act of 1934: Meaning, History 13 of 14

- Emergency Banking Act of 1933: Definition, Purpose, Importance 14 of 14

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-2003724854-2aff2851bdba49d3aa4d53a8323cadf8.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

Business Cycles

Economies experience times of growth and times of recession. Learn more about these fluctuations known as business cycles.

Temporary losses look to be severe after the collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge and closure of the Port of Baltimore, but there are several reasons to be optimistic about recovery.

Adam Scavette Regional Economist

President Tom Barkin explores different ways to look at recent data, and then gives his own perspective.

Tom Barkin President, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

Several factors include labor market participation, business cycle volatility and responsiveness to the underlying economic environment.

Marios Karabarbounis

How has the economy navigated previous rate cycles, and how do they compare to the current one?

Erin Henry , Pierre-Daniel G. Sarte and Jack Taylor

President Tom Barkin reflects on 2023 and shares his outlook for the year ahead.

Upcoming Event: What do Uber and the Federal Reserve have in common? They both hire economists! Did you know that some of your favorite brands also hire economists? But what do economists actually do? Registration required.

President Tom Barkin shares how communities in the Fifth District are working to move the needle on housing.

President Tom Barkin explores potential paths for the U.S. economy and their implications for monetary policy.

Is it possible durable goods spending will settle above the pre-pandemic trend line? If so, what might this consumption shift mean for the aggregate economy?

John O'Trakoun

President Tom Barkin explores what’s happening in the labor market and how it could impact the path ahead.

Out of the many components that make up the PPI, one particularly relevant item from the perspective of shoppers may be the PPI's trade indexes.

The current cycle appears to be unique in how inflation has moved during this most recent series of rate hikes.

Conner Mulloy , Pierre-Daniel G. Sarte and Erin Henry

President Tom Barkin discusses what’s driving the resilient U.S. economy and where it may be headed next.

How do state economies behave differently through the ups and downs of national business cycles? Do some states tend to enter recessions sooner (or later) than others? Are some states more recession-proof (or prone) than others?

Nicolas Morales discusses his research on supply chains and the factors that can help them resist and recover from economic shocks, like the COVID-19 pandemic. Morales is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

The Richmond Fed Community Conversations team visited Wythe County to explore the region's promises and possibilities.

While auto sales have been trending up over the past several months, we'll look into a couple of reasons why the future may not be so bright.

Wage-price pass throughs may help explain why core goods inflation has risen so much faster in the current expansion than in previous ones.

Changes in unemployment appear to be strong recession predictors, especially when combined with lagged term spreads.

Andreas Hornstein

Moves toward stable inflation and maximum employment can be in conflict in the short term.

Felipe F. Schwartzman

Among the topics discussed were income growth volatility, AI's impact on productivity and how housing price changes affect young businesses.

Tim Sablik and Matthew Wells

Jason Kosakow and Santiago Pinto describe how survey data is gathered and used to assess regional and national economic conditions. Kosakow is survey director and Pinto is a senior economist and policy advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

The lockdowns resulting from COVID-19 provide an opportunity to examine what factors affect the strength of supply chains.

Claire Conzelmann , Nicolas Morales , Gaurav Khanna and Nitya Pandalai-Nayar

Hard (or large) sovereign defaults have been associated with larger negative economic responses than soft defaults.

Brandon Fuller , Grey Gordon and Pablo Guerrón-Quintana

A new real-time measure of credit market sentiment appears to outperform credit conditions indicators currently used in the literature.

Danilo Leiva-León , Gabriel Pérez-Quirós , Horacio Sapriza , Francisco Vazquez-Grande and Egon Zakrajšek

The yield curve is often used to gauge potential recessions. Can its predictive value be improved?

While several indicators have pointed to a recent slowdown in economic activity, one that uses unemployment rates to gauge recession probabilities may offer new insights.

Sonya Ravindranath Waddell shares insights from the latest survey of chief financial officers and other financial decision-makers at companies across the United States. Waddell is a vice president and economist at the Richmond Fed.

As the Fed works to contain inflation, many ask whether we are headed into a recession. President Barkin shares his perspective.

We search for hysteresis in aggregate post-WWII U.S. data. Our findings suggest that hysteresis effects have been virtually absent for the sample excluding the financial crisis and the Great Recession, and they only appear when including the period following the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

Luca Benati and Thomas A. Lubik

Unlike in other recessions, women's labor force participation was impacted more than men's. What impact did child care have?

Kartik B. Athreya and Sierra Latham

How did unemployment insurance expansion affect recovery from the pandemic-induced recession? What are the effects of federal minimum wage hikes? A recent research conference addressed these questions and more.

John Mullin

The unemployment rate is close to pre-pandemic lows, and job openings are at record highs. Yet, participation and employment rates are still below pre-pandemic levels.

Andreas Hornstein and Marianna Kudlyak

The recent high inflation had been due to price changes in a small group of expenditures, but that changed a few months ago.

Alexander L. Wolman

Studies suggest that short-term effects of such spending are small and long-term effects depend on an economy's sensitivity to such investment.

News about productivity shocks — even when these shocks have not even happened yet — seems to be a powerful additional source of economic fluctuations.

Thomas A. Lubik , Christoph Gortz and Christopher Gunn

Is money essential? How do self-interested parties bargain to achieve mutually beneficial outcomes? These were among questions addressed at a recent research conference.

A surge of interest in starting new businesses could reverse a long-running drought.

The Beveridge curve — which measures the inverse relationship between the unemployment and vacancy rates — has shifted significantly outward and is much steeper than in pre-COVID times.

Thomas A. Lubik

Felipe Schwartzman and Chen Yeh discuss their research on business cycles and what forces impact them on the individual and aggregate level. Schwartzman is a senior economist and Yeh is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

The Fed's relatively new repo facilities may create greater price certainty, but the Fed's intervention may mute valuable market signals regarding economic efficiency and stability.

Huberto M. Ennis and Jeff Huther

Some argue that damages from climate change aren't large enough to affect the financial system, but what about amplification effects?

Unemployment insurance seems to help smooth consumer spending after a job loss, but there's disagreement on how much it discourages people from finding new jobs.

How do local government borrowing, default, and migration interact? We find in-migration results in excessive debt accumulation due to a key externality: Immigrants help repay previously issued debt.

Grey Gordon and Pablo Guerrón-Quintana

Household consumption shocks have accounted for close to 40 percent of pre-pandemic business cycle fluctuations.

Christian Matthes and Felipe F. Schwartzman

University of Texas at Austin economist on wage growth, labor's share of income, and the gender unemployment gap

David A. Price

Contrary to the traditional view, adverse events for a single firm can affect the economy as a whole, if the firm is large enough.

Without a recent directly comparable episode, economic forecasters modified their models or sought additional information in data to create forecasts during the pandemic.

Recent legislation has again highlighted the U.S. welfare system. This EB summarizes the welfare system and a "work bias" embedded in many U.S. welfare programs.

Claudia Macaluso

Conducting a statistical analysis of U.S. economic data, economists from the Richmond Fed and the University of Bern find no evidence of hysteresis, the idea that seemingly temporary economic shocks can have permanent effects.

Households' expectations often differ from formal economic forecasts. The researchers quantify these differences and explain them by developing a "theory of time-varying pessimism." Embedding their new theory into a quantitative economic model, they find that fluctuations in pessimism have significant effects on macroeconomic measures, most notably the unemployment rate.

Anmol Bhandari , Jaroslav Borovicka and Paul Ho

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused severe economic distress in the Fifth District, but the regional housing market has proven remarkably resilient.

Benjamin Lukas Intern (2020)

Much of the previous economic research on the aftermath of recessions has focused on their short-term effects on earnings and jobs. New research suggests that with longer-term consequences, workers' earnings, health and family outcomes may be affected.

Emily Green

This paper identifies total factor productivity (TFP) news shocks using standard VAR methodology and documents a new stylized fact: in response to news about future increases in TFP, inventories rise and comove positively with other major macroeconomic aggregates.

Christoph Gortz , Christopher Gunn and Thomas A. Lubik

There is enough research to suggest that sentiment does play a role in shaping the business cycle. The question facing policymakers is what to do about it.

Richmond Fed president Tom Barkin discusses economic conditions and the potential for a recession.

What caused the housing boom and bust of the early 2000s?

Daisuke Ikeda , Toan Phan and Tim Sablik

This Economic Brief evaluates the predictive capabilities of the yield curve and several other leading indicators, including the Conference Board Leading Economic Index (LEI), claims for unemployment insurance, manufacturing activity, consumer lending, and CEO optimism.

Matthew Murphy , Jessie Romero and Roy H. Webb

This brief makes the case that research and policy should focus on four aspects of economic fluctuations: a short-term component (cycles of less than two years), a business cycle component (cycles between two and eight years), a medium-term component (cycles up to thirty-two years), and a long-term component (the trend).

Renee Haltom , Thomas A. Lubik , Christian Matthes and Fabio Verona

The recent flattening of the yield curve has raised concerns that a recession is around the corner. Such concerns stem partly from the fact that yield curve inversions have preceded each of the past seven recessions.

Renee Haltom , Elaine Wissuchek and Alexander L. Wolman

Small banks do, in fact, play a special role in the intermediation of credit in the U.S. economy. But when the cyclical properties of NIM are decomposed into the asset and liability sides of the balance sheet, it appears that the liability side drives the difference in the performance of small and large banks.

Borys Grochulski , Daniel Schwam , Aaron Steelman and Yuzhe Zhang

A downturn following the collapse of an asset bubble — an episode of speculative booms in asset prices — can be severe and sustained, with output and employment often lower than in the prebubble economy. This Economic Brief considers some possible theoretical explanations.

Helen Fessenden and Toan Phan

Economic growth in the United States following the Great Recession has been well below the post-World War II average. Some observers have called this the "new normal."

Aaron Steelman and John A. Weinberg

Real business cycle (RBC) models have been highly successful at explaining business cycles that occurred before 1984. But since then, shifts in comovements and relative volatilities of key economic aggregates have challenged their preeminence.

Thomas A. Lubik , Karl Rhodes , Pierre-Daniel G. Sarte and Felipe F. Schwartzman

Are the majority of inner cities experiencing a renaissance thanks to rapid gentrification, or is growth limited to a small number of high-technology regions, resulting in inequality among metropolitan areas?

Aggregate demand is the total demand for all goods and services in an economy. Should the government try to boost it with fiscal stimulus during recessions?

Renee Haltom Vice President and Regional Executive

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker addressed the Global Interdependence Center in Sarasota, Florida.

Jeffrey M. Lacker President, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey Lacker addressed the Greater Richmond Chamber of Commerce.

Stanford University economist on the effects of economic uncertainty, the role of management practices in economic performance, and fostering good management

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker addressed business leaders during a luncheon hosted by the Rotary Club of Charlotte in Charlotte, N.C.

Andreas Hornstein , Marianna Kudlyak , Fabian Lange and Tim Sablik

This paper studies equilibrium pricing in a product market for an indivisible good where buyers search for sellers.

Guido Menzio and Nicholas Trachter

In this paper, we show that variations in the discount factor estimated using inventories correlate well with established independent measures of credit market frictions.

Thomas A. Lubik , Pierre-Daniel G. Sarte and Felipe F. Schwartzman

The Richmond Fed conducts monthly surveys of business conditions in the manufacturing and service sectors of the Fifth Federal Reserve District. This article provides background information on these surveys and on other manufacturing and service sector surveys.

David A. Price and Aileen Watson

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke about the economic outlook Jan. 17, 2014, in remarks to the Richmond chapter of the Risk Management Association.

In this paper we ask how uncertainty about fiscal policy affects the impact of fiscal policy changes on the economy when the government tries to counteract a deep recession.

Christian Matthes and Josef Hollmayr

We study the impact of intersectoral and interregional trade linkages in propagating disaggregated productivity changes to the rest of the economy.

Pierre-Daniel G. Sarte , Esteban Rossi-Hansberg , Fernando Parro and Lorenzo Caliendo

In a stylized quantitative analysis, we show that the consumption effect dominates, so that unemployment benefits increase per-worker productivity. We also analyze the welfare-maximizing benefit level and find that it decreases as moving costs increase.

David L. Fuller , Marianna Kudlyak and Damba Lkhagvasuren

We study the sovereign debt duration chosen by the government in the context of a standard model of sovereign default.

Juan Carlos Hatchondo and Leonardo Martinez

Robert L. Hetzel

A new database of online job posting data sheds light on how workers search for jobs.

Marianna Kudlyak and Jessie Romero

This paper provides a theoretical framework to quantitatively investigate the optimal accumulation of international reserves to hedge against rollover risk.

Javier Bianchi , Juan Carlos Hatchondo and Leonardo Martinez

In view of the increasing share of long-term unemployment since the 2007-09 recession, we provide an extension of the Shimer (2012) unemployment accounting scheme that allows for both short-term and long-term unemployment and that uses data on the duration distribution of unemployment.

Marianna Kudlyak and David A. Price

We show that, whereas during earlier recessions it was sufficient to examine the flows between employment and unemployment to account for the dynamics of the unemployment rate, this was not true in the Great Recession.

Marianna Kudlyak and Felipe F. Schwartzman

Marianna Kudlyak , Damba Lkhagvasuren and Roman Sysuyev

This paper examines the optimality of fiscal rules and measures their aggregate effects using a baseline sovereign default framework.

Juan Carlos Hatchondo , Leonardo Martinez and Francisco Roch

As households strengthen their balance sheets, their ability to take on new debt to finance consumption is improving, but household debt remains elevated by historical standards, and other determinants of consumer spending remain weak.

R. Andrew Bauer and Betty Joyce Nash

Juan Carlos Hatchondo , David A. Price and Jonathan Tompkins

Robert Schnorbus and Judy Cox

Andreas Hornstein , Thomas A. Lubik and Jessie Romero

Yongsung Chang and Andreas Hornstein

Lacker Addresses Dulles Regional Chamber of Commerce, Chantilly, Va.

Lacker speaks at Southern Growth's 2011 Chairman's Conference in Roanoke, Va.

Since the recession started in 2007, there has been a growing concern that small businesses may lack adequate access to credit. This Economic Brief examines the complexity of small business credit issues.

Betty Joyce Nash and Kimberly Zeuli

Robert Schnorbus and Aileen Watson

Marianna Kudlyak , David A. Price and Juan M. Sanchez

President Lacker Addresses Piedmont, N.C.'s Business Leaders

Marianna Kudlyak

Michael U. Krause and Thomas A. Lubik

Pierre-Daniel G. Sarte

Juan Carlos Hatchondo , Leonardo Martinez and Cesar Sosa Padilla

Lacker Addresses Greensboro, NC Business Leaders

Juan Carlos Hatchondo , Leonardo Martinez and Horacio Sapriza

Marianna Kudlyak , Devin Reilly and Stephen Slivinski

Thomas A. Lubik and Wing Leong Teo

President Lacker addresses the Maryland Bankers Association

Thomas A. Lubik and Stephen Slivinski

Cover Story: The Price is Right? Has the financial crisis provided a fatal blow to the efficient market hypothesis?

President Lacker addresses Charlotte business leaders

Cover Story: Measuring Quality of Life: How should we assess improvements to our standard of living?

Economists and policymakers often use average income as a way to gauge a country's "standard of living." But income alone doesn't capture overall quality of life. Should policymakers use other measures — including health, education, and even aggregate happiness — when making economic policy? Related Links

Lacker addresses VA House Appropriations Committee

Existing policies to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) largely have been structured to subsidize alternative energy technologies. Yet these policies are likely not to be as useful as ones that target CO2 emissions directly, such as an emissions tax or a "cap and trade" program.

Kartik B. Athreya and Renee Haltom

Lacker Speech to Charlotte RMA (Video Available)

Cover Story: Reforming the Raters: Can regulatory reforms adequately realign the incentives of credit rating agencies?

Lacker Speaks to Danville Chamber of Commerce

It is widely believed that public sector spending and investment can restore aggregate economic activity to efficient levels. But some policy responses are likely to be more successful than others.

Lacker Speaks at North Carolina Senate Appropriations Committee

Lacker Speaks at Beijing Banking Summit

President Lacker speaks to Charlottesville, Va., business leaders

President Jeffrey Lacker speaks to the Charleston Metro Chamber of Commerce.

President Lacker addresses the National Association for Business Economics at the 2009 Washington Economic Policy Conference

In this paper we develop a quantitative dynamic stochastic small open economy model with incomplete markets, endogenous fiscal policy and sovereign default where public expenditures and tax rates are optimally procyclical.

Gabriel Cuadra , Juan M. Sanchez and Horacio Sapriza

President Lacker addresses the Risk Management Association, Richmond Chapter

President Lacker speaks to the Maryland Bankers Association.

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke December 3, 2008, at the Charlotte Chamber of Commerce Economic Outlook Conference in Charlotte, N.C.

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke at the November 21, 2008 meeting of The Tech Council of Maryland in Bethesda, Md.

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke November 18, 2008 at the CATO Institute's 26th Annual Monetary Conference in Washington, D.C.

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke at the Global Interdependence Center Conference held November 3, 2008 at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke June 5, 2008 at the Distinguished Speakers Seminar European Economics and Financial Centre, London, England.

Michael U. Krause , David Lopez-Salido and Thomas A. Lubik

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke February 5, 2008 to the West Virginia Bankers Association and the Community Bankers of West Virginia in Charleston, W.Va.

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey M. Lacker spoke January 18, 2008 to the Risk Management Association in Richmond, Va.

Thomas A. Lubik and Paolo Surico

A. Andrew John and Alexander L. Wolman

It's a pleasure to be here today and to have this opportunity to comment on conducting monetary policy in a low inflation environment.

J. Alfred Broaddus President

Reviews the Bank's operations and includes the article entitled "Accounting for Corporate Behavior"

Marvin Goodfriend and Robert G. King

- About the Levy Economics Institute

- Board of Governors

- Board of Advisors

- Staff Directory

- Employment at the Levy Institute

- Visit the Levy Institute

- Research Programs:

- The State of the US and World Economies

- Monetary Policy and Financial Structure

- The Distribution of Income and Wealth

- • Levy Institute Measure of Economic Well-Being

- • Levy Institute Measure of Time and Income Poverty

- Gender Equality and the Economy

- Employment Policy and Labor Markets

- Immigration, Ethnicity, and Social Structure

- Economic Policy for the 21st Century

- • Federal Budget Policy

- • Explorations in Theory and Empirical Analysis

- • INET–Levy Institute Project

- Equality of Educational Opportunity in the 21st Century

- Special Projects:

- Ford-Levy Institute Project

- Levy Institute M.S. in Economic Theory and Policy

- Greek Labor Institute Partnership

- Minsky Archive

- Multiplier Effect

- Levy Institute M.S. in Economic Policy and Theory

- Economics Program at Bard

- Bard Program in Economics and Finance

- Greek Labour Institute Partnership

- Economists for Peace and Security

- Economists for Full Employment

- Current Research Topics:

- Greek economic crisis

- Labor force participation

- Income inequality

- Employment policy

- Job guarantee

- Climate Change and Economic Policy

- Financial instability

- Stock-flow consistent (SFC) modeling

- Time deficits

- Fiscal austerity

- Research Project Reports

- Strategic Analysis

- Public Policy Briefs

- Policy Notes

- Working Papers

- LIMEW Reports

- e-pamphlets

- Book Series

- Conference Proceedings

- Biennial Reports

- Public Policy Brief Highlights

- In Translation Δημοσιεύσεις στα Ελληνικά

- Press Releases

- In the Media

- Request an Interview

- Sign Up for eNews

- Research Programs

Research Topics

- Request an Interview

Publications on Business cycles

Keynes’s theories of the business cycle, evolution and contemporary relevance, some comments on the sraffian supermultiplier approach to growth and distribution, inequality update: who gains when income grows, reorienting fiscal policy, a critical assessment of fiscal fine-tuning.

The present paper offers a fundamental critique of fiscal policy as it is understood in theory and exercised in practice. Two specific demand-side stabilization methods are examined here: conventional pump priming and the new designation of fiscal policy effectiveness found in the New Consensus literature. A theoretical critique of their respective transmission mechanisms reveals that they operate in a trickle-down fashion that not only fails to secure and maintain full employment but also contributes to the increasing postwar labor market precariousness and the erosion of income equality. The two conventional demand-side measures are then contrasted with the proposed alternative—a bottom-up approach to fiscal policy based on a reinterpretation of Keynes’s original policy prescriptions for full employment. The paper offers a theoretical, methodological, and policy rationale for government intervention that includes specific direct-employment and investment initiatives, which are inherently different from contemporary hydraulic fine-tuning measures. It outlines the contours of the modern bottom-up approach and concludes with some of its advantages over conventional stabilization methods.

Growth Trends and Cycles in the American Postwar Period, with Implications for Policy

Do all types of demand have the same effect on output? To answer this question, I estimate a cointegrated vector autoregressive (VAR) model of consumption, investment, and government spending on US data, 1955–2007. I find that: (1) economic growth can be decomposed into a short-run (transitory) cycle gravitating around a long-run (permanent) trend made of consumption shocks and government spending; (2) the estimated fluctuations are investment dominated, they coincide remarkably with the business cycle, and they are highly correlated with capacity utilization in both labor and capital; and (3) the long-run multipliers point to a large induced-investment phenomenon and to a smaller, but still significantly positive, government spending multiplier, around 1.5. The results cover a lot of theoretical ground: Paul Samuelson’s accelerator principle, John Kenneth Galbraith’s stress on consumption and government spending, Jan Tinbergen's investment-driven business cycle, and Robert Eisner’s inquiries on the investment function. The results are particularly useful to distinguish between economic policies for the short and long runs, albeit no attempt is made at this point to inquire into the effectiveness of specific economic policies.

Weak Expansions

A distinctive feature of the business cycle in latin america and the caribbean.

Using two standard cycle methodologies (classical and deviation cycle) and a comprehensive sample of 83 countries worldwide, including all developing regions, we show that the Latin American and Caribbean cycle exhibits two distinctive features. First, and most important, its expansion performance is shorter and, for the most part, less intense than that of the rest of the regions considered; in particular, that of East Asia and the Pacific. East Asia’s and the Pacific’s expansions last five years longer than those of Latin American and the Caribbean, and its output gain is 50 percent greater. Second, the Latin American and Caribbean region tends to exhibit contractions that are not significantly different from those other regions in terms of duration and amplitude. Both these features imply that the complete Latin American and Caribbean cycle has, overall, the shortest duration and smallest amplitude in relation to other regions. The specificities of the Latin American and Caribbean cycle are not confined to the short run. These are also reflected in variables such as productivity and investment, which are linked to long-run growth. East Asia’s and the Pacific’s cumulative gain in labor productivity during the expansionary phase is twice that of Latin American and the Caribbean. Moreover, the evidence also shows that the effects of the contraction in public investment surpass those of the expansion, leading to a declining trend over the entire cycle. In this sense, we suggest that policy analysis needs to increase its focus on the expansionary phase of the cycle. Improving our knowledge of the differences in the expansionary dynamics of countries and regions can further our understanding of the differences in their rates of growth and levels of development. We also suggest that, while the management of the cycle affects the short-run fluctuations of economic activity and therefore volatility, it is not trend neutral. Hence, the effects of aggregate demand management policies may be more persistent over time, and less transitory, than currently thought.

The Household Sector Financial Balance, Financing Gap, Financial Markets, and Economic Cycles in the US Economy

A structural var analysis.

This paper investigates private net saving in the US economy—divided into its principal components, households and (nonfinancial) corporate financial balances—and its impact on the GDP cycle from the 1980s to the present. Furthermore, we investigate whether the financial markets (stock prices, BAA spread, and long-term interest rates) have a role in explaining the cyclical pattern of the two private financial balances. We analyze all these aspects estimating a VAR—between household and (nonfinancial) corporate financial balances (also known as the corporate financing gap), financial markets, and the economic cycle—and imposing restrictions on the matrix A to identify the structural shocks. We find that households and corporate balances react to financial markets as theoretically expected, and that the economic cycle reacts positively to corporate balance, in accordance with the Minskyan view of the operation of the economy that we have embraced.

Minsky Moments, Russell Chickens, and Gray Swans

The methodological puzzles of the financial instability analysis.

The recent revival of Hyman P. Minsky’s ideas among policymakers, economists, bankers, financial institutions, and the mass media, synchronized with the increasing gravity of the subprime financial crisis, demands a reappraisal of the meaning and scope of the “financial instability hypothesis” (FIH). We argue that we need a broader approach than that conventionally pursued, in order to understand not only financial crises but also the periods of financial calm between them and the transition from stability to instability. In this paper we aim to contribute to this challenging task by restating the strictly financial part of the FIH on the basis of a generalization of Minsky’s taxonomy of economic units. In light of this restatement, we discuss a few methodological issues that have to be clarified in order to develop the FIH in the most promising direction.

A Financial Sector Balance Approach and the Cyclical Dynamics of the US Economy

This paper investigates the relationship between asset markets and business cycles with regard to the US economy. We consider the Goldman Sachs approach (2003) developed to study the dynamics of financial balances.

By means of a small econometric model we find that asset market dynamics are fundamental to determining the long-run financial sector balance dynamics. The gap between long-run equilibrium values and the actual values of the financial balances help to explain the cyclical path of the economy. Among all financial sectors balances, the financing gap in the corporate sector shows a leading effect on business cycles, in a Minskyan spirit. The last results appear innovative with respect to Goldman Sachs’s findings. Furthermore, our econometric results are robust and quite stable.

Quick Search

Current research topics.

From the Press Room

- Publications

- Memberships

Research Cycle Process and Theory explained

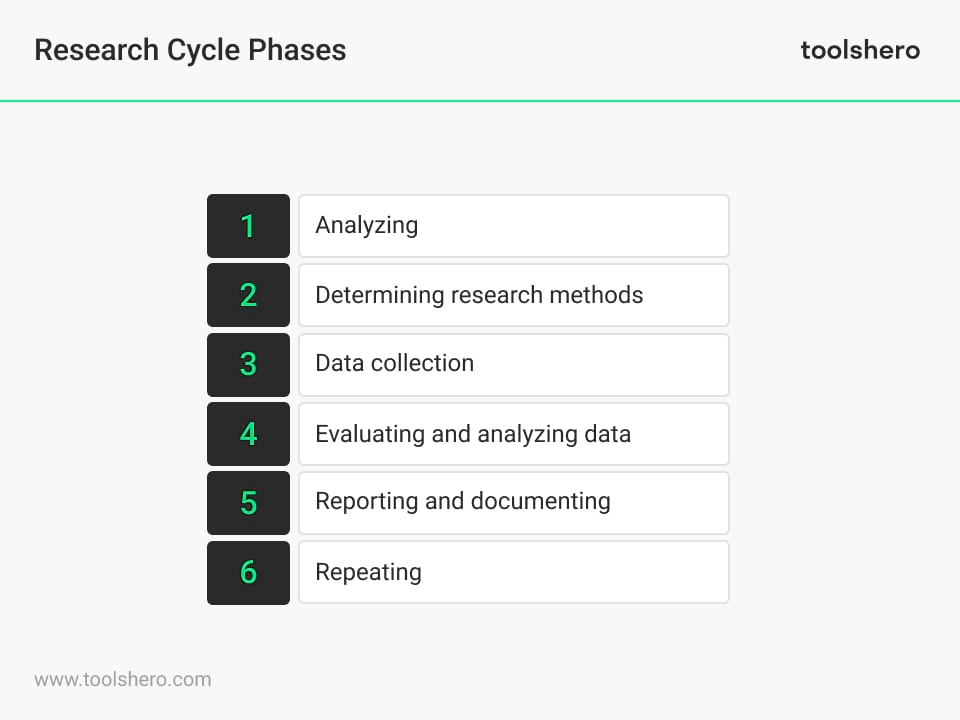

Research Cycle: This article provides a practical explanation of the research cycle . The article begins with a list of the research stages and a list of questions that every researcher should ask themselves before and during the research process. After this introduction, you will find a detailed explanation about every phase of the research cycle, as well as tips and recommendations for starting researchers. Enjoy reading!

What is a research cycle?

A research cycle is a series of stages that guide the user through the process of conducting research. The cycle roughly consists of the following stages:

- Determining research methods

- Data collection

- Evaluating and analyzing data

- Reporting and documenting

These stages will be discussed later in this article, including a description of the tasks and results from each stage. Because every research project is unique, it is important to constantly ask yourself the following questions:

- What am I going to research?

- Why am I researching this?

- Who am I going to research?

- How am I going to conduct my research?

- Where am I going to conduct my research?

- When am I going to conduct my research?

Stages of the research cycle

Research is a vital process for gaining insights and discovering new information in a particular field. The research cycle involves several stages, including analyzing the problem , determining research methods , collecting data, analyzing and evaluating the data, reporting and documenting the findings, and repeating the process.

Figure 1 – Phases / Stages of the research cycle

Stage 1: Analyzing

The first stage of the research cycle is analyzing the problem or topic under investigation. Researchers need to define the research question, scope of the study, and background of the research topic, including its significance in the field.

This stage also requires a thorough review of existing literature and research and identifying any potential limitations. The definition of research questions is also part of this phase.

Stage 2: Determining Research Methods

The next stage is determining the research methods to be used, including research design, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques.

Researchers must select the most appropriate methods for their study based on the research question, data availability, the type of field research and time constraints.

Stage 3: Data Collection

The third stage involves collecting the data needed to answer the research question. Researchers must ensure that the data collection methods used are reliable and valid, and take into consideration ethical considerations such as obtaining informed consent from participants and maintaining confidentiality.

Stage 4: Evaluating and Analyzing Data

The fourth stage is evaluating and analyzing the data collected to answer the research question. This involves cleaning and organizing the data and conducting statistical analysis using appropriate software. The results of the analysis are then interpreted, and conclusions are drawn based on the findings.

Stage 5: Report and Document

The fifth stage is reporting and documenting the findings. Researchers must present the research question, methods, results, and conclusions in a clear and concise manner. The report must be well-organized and easy to read, and the findings presented in a way that is meaningful to the target audience. Researchers must also include a discussion of the study’s limitations and recommendations for future research.

Stage 6: Repeat

The final stage of the research cycle involves repeating the process to refine the research question and methods. Researchers may need to conduct additional studies to address any limitations or questions that arise from the initial study. This iterative process allows researchers to continually refine their methods and findings, leading to more accurate and reliable results.

In conclusion, the research cycle is a crucial process that requires careful consideration and planning. By following the research cycle, researchers can ensure that their studies are well-designed, valid, and reliable. This iterative process allows researchers to continually refine their methods and findings, contributing to the advancement of their field.

Research Methodology Bootcamp: Research Methods Simplified More information

Research Cycle tips and recommendations for the starting researcher

For anyone just starting out in the world of research, it can be a daunting task to navigate. However, with the right approach and mindset, starting researchers can set themselves up for success. Here are some tips and recommendations for those just beginning their research journey:

Start with a clear research question

Before beginning any research project, it is important to have a clear research question in mind. This will help guide your research and keep you focused throughout the process.

Conduct a thorough literature review

It is important to research existing literature on your topic to ensure that your research question has not already been answered or explored. Additionally, a literature review can provide valuable insights and information that can inform your research design and methods.

Choose appropriate research methods interviews , or experiments. It is important to choose methods that are appropriate for your research question and can yield valid and reliable results. Collect and analyze data carefully

Data collection and analysis are crucial components of any research project. It is important to ensure that your data is collected accurately and analyzed using appropriate statistical techniques.

Communicate your findings effectively

Once your research is complete, it is important to communicate your findings clearly and effectively to your target audience. This can include writing reports or creating presentations that are well-organized and easy to understand.

Now It’s Your Turn

What do you think? Do you recognize the explanation about the research cycle? Do you recognize the cycle from times where you were working on a research topic, like your thesis? Do you think the cycle is complete and accurate as described? Or do you add new phases and elements to it? Which other tips and recommendations can you add?

Share your experience and knowledge in the comments box below.

More information

- Barick, R. (2021). Research Methods For Business Students . Retrieved 02/16/2024 from Udemy.

- Berman, P. S., Jones, J., & Udry, J. R. (2000). Research design . National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health.

- Fox, W., & Bayat, M. S. (2008). A guide to managing research . Juta and company Ltd.

- Verhoeven, N. (2007). Doing research. The Hows and Whys of Applied Research . Boom Lemma Uitgevers .

How to cite this article: Janse, B. (2023). Research Cycle Process . Retrieved [insert date] from Toolshero: https://www.toolshero.com/research/research-cycle/

Original publication date: 07/25/2023 | Last update: 01/02/2023

Add a link to this page on your website: <a href=”https://www.toolshero.com/research/research-cycle/”>Toolshero: Research Cycle Process</a>

Did you find this article interesting?

Your rating is more than welcome or share this article via Social media!

Average rating 4.2 / 5. Vote count: 5

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Ben Janse is a young professional working at ToolsHero as Content Manager. He is also an International Business student at Rotterdam Business School where he focusses on analyzing and developing management models. Thanks to his theoretical and practical knowledge, he knows how to distinguish main- and side issues and to make the essence of each article clearly visible.

Related ARTICLES

Respondents: the definition, meaning and the recruitment

Market Research: the Basics and Tools

Gartner Magic Quadrant report and basics explained

Univariate Analysis: basic theory and example

Bivariate Analysis in Research explained

Contingency Table: the Theory and an Example

Also interesting.

Content Analysis explained plus example

Field Research explained

Observational Research Method explained

Leave a reply cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

BOOST YOUR SKILLS

Toolshero supports people worldwide ( 10+ million visitors from 100+ countries ) to empower themselves through an easily accessible and high-quality learning platform for personal and professional development.

By making access to scientific knowledge simple and affordable, self-development becomes attainable for everyone, including you! Join our learning platform and boost your skills with Toolshero.

POPULAR TOPICS

- Change Management

- Marketing Theories

- Problem Solving Theories

- Psychology Theories

ABOUT TOOLSHERO

- Free Toolshero e-book

- Memberships & Pricing

Advertisement

Supported by

Is the Boom-and-Bust Business Cycle Dead?

There is a growing view that the U.S. business cycle has changed (for better) in a more diversified economy. To some, that sounds like tempting fate.

- Share full article

By Talmon Joseph Smith

For much of modern history, even the richest nations have been subject to big perennial upswings and crashes in commercial activity almost as fixed as the four seasons.

Periods of economic growth get overstretched by increased risk-taking. Hiring and investment crest and fall into a contraction as consumer confidence wanes and spending craters. Sales fall, bankruptcies and unemployment rise. Then, in the depths of a recession, debts are settled, panic abates, green shoots appear, and banks begin lending more easily again — fueling a recovery that enables a new upswing.

But a brigade of academic economists and prominent voices on Wall Street are asking if the unruly business cycle they learned in school, and witnessed in practice, has fundamentally morphed into a tamer beast.

Rick Rieder, who manages about $3 trillion in assets at the investment firm BlackRock, is one of them.

“There is a lot of ink spilled on what type of landing we will see for the U.S. economy,” he wrote in a note to clients last summer — employing the common metaphor for whether the U.S. economy will crash or achieve a “soft landing” of lower inflation, slower growth and mild unemployment.

“But one point to keep in mind,” Mr. Rieder continued, “is that satellites don’t land and maybe that is a better analogy for a modern advanced economy” like the United States. In other words, dips in momentum will now happen within a steadier orbit.

And there is some evidence that the current spurt of economic growth may have not just months but several years to run, barring an external disruption (what economists call an “ exogenous shock ”) or a return of high inflation that prompts the Federal Reserve to push the economy into recession.

“Financial reporters and market strategists often argue about whether we are ‘early-cycle,’ ‘mid-cycle’ or ‘late-cycle,’” David Kelly, the chief global strategist at J.P. Morgan Asset Management, wrote in a March 11 note to investors that closely aligned with Mr. Rieder’s “satellite” thesis. “However, these perspectives are based on an outdated model of how the U.S. economy behaves.”

According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the U.S. economy between the 1850s and the early 1980s experienced 30 recessions lasting an average of 18 months, with intervening periods of economic growth averaging only 33 months.

Helping drive this pattern, Mr. Kelly and other economists explain, were highly cyclical industries: Manufacturing and agriculture, now only a fraction of overall output, were once mainstays of the U.S. economy.

Today, manufacturing accounts for about $2.3 trillion of gross domestic product, employs about 12 million people and indirectly supports other local jobs. (Every manufacturing job, for instance, spurs seven to 12 new jobs in related industries, according to a McKinsey estimate.)

But the consumer-driven U.S. economy, mostly made up of services (health care, auto repair, nail salons, customer service, administration and so on), is almost $30 trillion in size. Uptrends and pullbacks in the production of goods have less impact now. The relative stability of total household spending in recent years is a key part of why the United States has avoided a recession.

America’s contemporary economy, Mr. Rieder argued in his note to clients, is less vulnerable to the boom-and-bust cycles of old — mainly because its prosperous consumers are service-oriented, less dependent than ever on factories or farms. Consumption spending makes up about 70 percent of the economy.

“Consumption doesn’t really adjust that dramatically without some major form of economic stress,” he added.

One piece of data in favor of Mr. Rieder’s “satellite” theory is the absence of any widespread weakness before the pandemic crippled economies worldwide.

That was consistent with a developing trend: Since the early 1980s, there have been only four recessions, lasting an average of nine months, with economic expansions averaging 104 months.

The current period of job growth is in its 40th month.

“You don’t want to jinx it,” Ann Harrison, the dean of the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley, said in an interview — noting that peak confidence in economic expansions frequently arrives right before their downfall. (Talk has picked up of a new “ Roaring Twenties ,” an era that didn’t end well.)

As ever, there are reasons to worry. The emergence and rapid growth of “shadow banks” operating in private markets with little oversight of their lending has concerned many economists and old-school regulators. And a range of industry insiders in commercial real estate say the negative effects of lower office occupancy rates — for local economies and government budgets — have only just begun.

Yet Mr. Kelly of J.P. Morgan lists various reasons that periods of U.S. economic growth may be elongated and less chaotic going forward. Federal deposit insurance, introduced after the Depression, sharply reduced bank panics and failures. Vastly improved information on inventory levels among goods-producing businesses, he said, has “tamed” the inventory cycle, preventing mismatches between supply and demand that can cause mass layoffs.

The rise of international trade, Mr. Kelly added, can often offset slowing domestic demand since businesses, enabled by the internet, can find customers throughout the globe. And the service sector’s growth, he concluded, has “made the economy more stable and, importantly, less sensitive to interest rates.”

Across the economics profession, many are not feeling as reassured.

When weighing recession risks, Thomas Herndon, a professor of economics at John Jay College of the City University of New York, doesn’t take much long-term solace in the growing sophistication of big business. There are, he said, “many, many, many causes” for downturns — some of which are not directly linked to financial instability.

Mr. Herndon noted the work of the 20th-century Polish economist Michal Kalecki, who argued that business leaders feel “undermined” by the maintenance of full employment. Using their substantial influence over policy, Kalecki argued, they can help institute restrictive economic policies that bring times of economic expansion to an end and reset them with softer, more tolerable labor power.

And Mr. Herndon said he thought old-fashioned “bubble” manias and “credit cycles” remained a danger, too.

Eliminating the longstanding economic cycle would be “the holy grail of central banking,” said James Knightley, chief international economist at ING, the global bank. “The Fed’s willingness to use innovative tools” — like its off-the-cuff creation of lending facilities to keep credit flowing on Main Street and heal bank balance sheets since 2020 — gives it “more levers to wiggle to help reduce the chance of a downturn,” Mr. Knightley said.

“Phrases like ‘This time it will be different’” generally have a bad track record, he said. “But maybe it will.”

In several ways, this time has been different so far.

Typically, the housing sector — and its interconnected industries, from construction and home improvement to real estate finance — accounts for nearly 20 percent of U.S. output . The Federal Reserve has more than quadrupled its interest-rate levels since the spring of 2022, bringing its key policy rate to over 5 percent from near zero. That drove mortgage rates to unaffordable highs and made financing new home building difficult. And the residential real estate sector, highly sensitive to interest rates, ground to a halt. But the economy as a whole continued to grow.

When in-person services plummeted during the pandemic, e-commerce and goods-buying picked up the slack. By the time millions of households were sated with goods purchases and manufacturing fell off, the in-person economy was reopening and in-person services began a booming recovery.

There are some market analysts, such as Jim Bianco of Bianco Research, who believe that the U.S. economy — in its dynamism, diversity and size — has in some respects begun to resemble the global economy itself, which typically contracts only when colossal shocks to output occur.

The global financial crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic — which were separated by only 10 years and did cause global recessions — show that while rare, such maelstroms can coincidentally occur back to back. So, long expansions are no guarantee. On the flip side, Australia went about three decades without a recession until Covid ended the streak .

Nina Eichacker, a professor of economics at the University of Rhode Island and the author of two recent papers about government responses to crises, cited another influence: a powerful school of thought that government interventions, even amid downturns, add “frictions and inefficiencies to markets” and “make us worse off overall.”

The robust federal response to the pandemic shock was enabled by a general view that it was an act of nature. Future financial stresses are more likely to have villains, which means proposed solutions are more likely to face division in Congress even if unemployment is notably rising.

But Ms. Eichacker thinks that those political limits to consensus may soften if this expansion rolls on and public opinion of the hefty federal response that helped foster it grows fonder.

“I am sometimes freaked out by how optimistic I feel about the state of things,” she said. “Economically anyway.”

Talmon Joseph Smith is a Times economics reporter, based in New York. More about Talmon Joseph Smith

We've detected unusual activity from your computer network

To continue, please click the box below to let us know you're not a robot.

Why did this happen?

Please make sure your browser supports JavaScript and cookies and that you are not blocking them from loading. For more information you can review our Terms of Service and Cookie Policy .

For inquiries related to this message please contact our support team and provide the reference ID below.

Advertisement

Business Cycles and the Dynamics of Innovation: a Theoretical Perspective

- Published: 04 March 2023

Cite this article

- Manzoor Ahmad ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5858-6994 1 ,

- Zahoor Ul Haq 1 &

- Shehzad Khan 2

545 Accesses

2 Citations

Explore all metrics

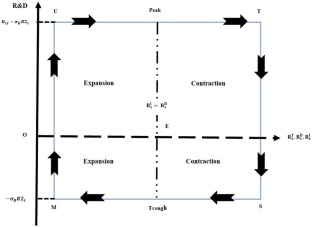

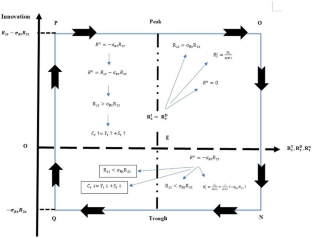

This paper constructs a simple dynamic growth model and deducts four theoretical predictions: prediction I , new knowledge creations and research and development expenditures (R&DE) contribute to economic upturns and downturns; prediction II , the R&DE and new knowledge creations upsurge and fall in the economic expansions and contractions periods, respectively; prediction III , the research intensity and frequency of new knowledge creations increase and reduce during boom and recession periods, respectively; prediction IV , positive and negative shocks in R&DE and new knowledge creation are caused by changes in consumption, saving, R&DE, and innovation activities during economic boom and slump periods; and prediction IV , innovation and gross domestic product have a bidirectional causal nexus during trade cycles.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Source: Ahmad and Zheng ( 2022 )

Similar content being viewed by others

The determinants of innovation performance: an income-based cross-country comparative analysis using the Global Innovation Index (GII)

Adisu Fanta Bate, Esther Wanjiru Wachira & Sándor Danka

Neoclassical Economics: Origins, Evolution, and Critique

Intellectual property rights and R&D subsidies: are they complementary policies?

Aghion, P, & Howitt, P. W. (2008). The economics of growth . MIT Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=B9vxCwAAQBAJ

Aghion, P., Askenazy, P., Berman, N., Cette, G., & Eymard, L. (2012). Credit constraints and the cyclicality of r&d investment: Evidence from France. Journal of the European Economic Association, 10 (5), 1001–1024. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-4774.2012.01093.x

Article Google Scholar

Ahmad, M., Khan, Z., Rahman, Z. U., Khattak, S. I., & Khan, Z. U. (2021). Can innovation shocks determine CO2 emissions (CO2e) in the OECD economies? A new perspective. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 30 (1), 89–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599.2019.1684643

Ahmad, M., & Zheng, J. (2022). The cyclical and nonlinear impact of R&D and innovation activities on economic growth in OECD economies: A new perspective. Journal of the Knowledge Economy . https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-021-00887-7

Anzoategui, D., Comin, D., Gertler, M., & Martinez, J. (2019). Endogenous technology adoption and R&D as sources of business cycle persistence. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 11 (3), 67–110.

Google Scholar

Archibugi, D., & Filippetti, A. (2013). Innovation and economic crisis: Lessons and prospects from the economic downturn . Taylor & Francis. https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=iIioAgAAQBAJ

Arndt, J. (1983). The political economy paradigm: foundation for theory building in marketing. Journal of marketing, 47 (4), 44–54. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/002224298304700406?journalCode=jmxa

Arnold, L. G. (2006). The dynamics of the Jones R&D growth model. Review of Economic Dynamics, 9 (1), 143–152.

Arrow, K. J. (1972). Economic welfare and the allocation of resources for invention. In Readings in industrial economics (pp. 219–236). Springer.

Ayres, R. U., & Warr, B. (2010). The economic growth engine: How energy and work drive material prosperity . Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bahamas. (1984). Estimating expenditure on gross domestic product for the Bahamas, 1980–1982 . Department of Statistics. https://books.google.com/books?id=IS9rI1m4PUoC

Barlevy, G. (2007). On the cyclically of research and development. In American Economic Review (Vol. 97, Issue 4, pp. 1131–1164). https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.97.4.1131

Bayarcelik, E. B., & Taşel, F. (2012). Research and development: Source of economic growth. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 58 , 744–753.

Beneito, P., Rochina-Barrachina, M. E., & Sanchis-Llopis, A. (2015). Ownership and the cyclicality of firms’ R&D investment. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11 (2), 343–359.

Bernstein, J. I., & Mamuneas, T. P. (2005). Depreciation estimation, R&D capital stock, and North American manufacturing productivity growth. Annales d’Économie et de Statistique , 383–404.

Castellacci, F. (2007). Evolutionary and new growth theories. Are they converging? Journal of Economic Surveys , 21 (3), 585–627.

Colander, D. C. (2003). Macroeconomics . McGraw-Hill/Irwin. https://books.google.com/books?id=AIoeHbH1QhgC

Comin, D. (2004). R&D: A small contribution to productivity growth. Journal of Economic Growth, 9 (4), 391–421.

Diacon, P. -E., & Maha, L. -G. (2015). The relationship between income, consumption and GDP: A time series, cross-country analysis. Procedia Economics and Finance, 23 , 1535–1543.

Downing, D., & Clark, J. (1992). Business statistics . Barron’s Educational Series. https://books.google.com/books?id=oRNq4rTTHb8C

Fabrizio, K. R., & Tsolmon, U. (2014). An empirical examination of the procyclicality of R&D investment and innovation. Review of Economics and Statistics, 96 (4), 662–675. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00412

Francois, P., & Lloyd-Ellis, H. (2009). Schumpeterian cycles with pro-cyclical R&D. Review of Economic Dynamics, 12 (4), 567–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RED.2009.02.004

Francois, P., & Lloyd-Ellis, H. (2008). Implementation cycles, investment, and growth. International Economic Review, 49 (3), 901–942.

Gabrovski, M. (2020). Simultaneous innovation and the cyclicality of R&D. Review of Economic Dynamics, 36 , 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2019.09.002

Glanville, A., & Glanville, J. (2011). Economics from a global perspective . Glanville Books. https://books.google.com/books?id=tV7jEjMU4QcC

Grabowski, R. (1999). Pathways to economic development . Edward Elgar. https://books.google.com/books?id=JHC4AAAAIAAJ

Guellec, D., & Ioannidis, E. (1997). Causes of fluctuations in R&D expenditures-A quantitative analysis. OECD Economic Studies , 123–138.

Gupta, K. R. (2009). Economics of development and planning (Issue v. 1). Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=ULJTAsND2zgC

Ha, J., & Howitt, P. (2007). Accounting for trends in productivity and R&D: A Schumpeterian critique of semi-endogenous growth theory. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 39 , 733–774.

Hanusch, H., & Pyka, A. (2007). Elgar companion to neo-Schumpeterian economics . Edward Elgar. https://books.google.com/books?id=P0zUrTYpMnkC

Harashima, T. (2005). The pro-cyclical R&D puzzle: Technology shocks and pro-cyclical R&D expenditure. Macroeconomics .

Hottenrott, H., & Zhang, T. (2015). On the cyclicality of R&D investments in the presence of financial constraints and R&D subsidies .

Jones, C. I., & Vollrath, D. (2013). Introduction to economic growth . https://books.google.com/books?id=cQPQLwEACAAJ&dq=Introduction+to+Economic+Growth&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwifwKmx99TgAhUQCewKHXIsBCIQ6AEINDAC

Jones, C. I., & Williams, J. C. (2000). Too much of a good thing? The economics of investment in R&D. Journal of Economic Growth, 5 (1), 65–85.

Kabukcuoglu, Z. (2019). The cyclical behavior of R&D investment during the Great recession. Empirical Economics, 56 (1), 301–323.

Kirchhoff, B. A. (1994). Entrepreneurship and dynamic capitalism: The economics of business firm formation and growth . Praeger. https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=_aVSzzMOUTEC

Kiselakova, D., Sofrankova, B., Cabinova, V., Onuferova, E., & Soltesova, J. (2018). The impact of R&D expenditure on the development of global competitiveness within the CEE EU countries. Journal of Competitiveness, 10 (3), 34–50.

Konstantakis, K. N., & Michaelides, P. G. (2017). Does technology cause business cycles in the USA? A Schumpeter-inspired approach. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 43 , 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2017.05.005

Levacic, R. (1976). Macroeconomics: The static and dynamic analysis of a monetary economy . Macmillan. https://books.google.com/books?id=9Bm3AAAAIAAJ

López García, P., Montero Montero, J. M., & Moral Benito, E. (2012). Business cycles and investment in intangibles: Evidence from Spanish firms. Documentos de Trabajo/Banco de España, 1219 .

Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22 (1), 3–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(88)90168-7

Mand, M. (2019). On the cyclicality of R&D activities. Journal of Macroeconomics, 59 , 38–58.

Marcelino-Jesus, E., Sarraipa, J., Beça, M., & Jardim-Goncalves, R. (2017). A framework for technological research results assessment. International Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing, 30 (1), 44–62.

Matsuyama, K. (1999). Growing through cycles. Econometrica, 67 (2), 335–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00021

Miller, R. L. R., Hornsby, & Clegg, N. W. (1999). Economics today: Macro view . Addison-Wesley Longman, Incorporated. https://books.google.com/books?id=J5uUCMX2yecC

Nafziger, E. W. (2012). Economic development . Cambridge University Press. https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=bGxVzEdae7UC

Nuño, G. (2011). Optimal research and development and the cost of business cycles. Journal of Economic Growth, 16 (3), 257–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-011-9063-4

OECD. (2018). Growth: Rationale for an innovation strategy. 2007. Availabe from https://www.OECD.org/Site/Innovationstrategy/Readingmaterial.htm

Ouyang, M. (2011). On the cyclicality of R&D. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93 (2), 542–553. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00076

Pansera, M., & Owen, R. (2019). Innovation and development: The politics at the bottom of the pyramid . Wiley. https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=UMt7DwAAQBAJ

Parkes, H. B., Parkes, & Bamford, H. (1943). Capitalism, socialism, and democracy. By Joseph A. Schumpeter. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1942. Pp. x, 381. $3.50. The Journal of Economic History , 3 (02), 238–239. https://econpapers.repec.org/article/cupjechis/v_3a3_3ay_3a1943_3ai_3a02_3ap_3a238-239_5f08.htm

Romer, P. M. (1986). Increasing returns and long-run growth. Journal of Political Economy, 94 (5), 1002–1037. https://doi.org/10.1086/261420

Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of political Economy, 98 (5), 71–102. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1506720

Romer, P. M. (1994). The origins of endogenous growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8 (1), 3–22.

Root, F. R. (1984). International trade & investment . South-Western Publishing Company. https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=pzQFAQAAIAAJ

Ruttan, V. W. (2003). Social science knowledge and economic development: An institutional design perspective . University of Michigan Press.

Saeed, K. (2019). Towards sustainable development: Essays on system analysis of national policy . Taylor \& Francis. https://books.google.com/books?id=bPODDwAAQBAJ

Samuelson, P. A. (2010). Economics . Tata McGraw Hill. https://books.google.com/books?id=gzqXdHXxxeAC

Schiller, B. R. (2005). The macro economy today with discoverecon with Solman videos . McGraw-Hill Higher Education. https://books.google.com/books?id=%5C_-Oc02aqjJQC

Schmookler, J. (1966). Invention and business growth . MA, Harvard University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Schot, J., & Steinmueller, W. E. (2018). Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation and transformative change. Research Policy , 47 (9), 1554–1567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.08.011

Schumpeter, J. (1911). The theory of economic development . Harvard University Press.

Schumpeter, J. (1939). Business cycles: A theoretical, historical and statistical analysis of the capitalist process . McGraw-Hill Book company Inc.

Schumpeter, J. (1942). Creative destruction. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, 825 , 82–85.

Sengupta, J. (2013). Theory of innovation: A new paradigm of growth . Springer International Publishing. https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=LTgnAQAAQBAJ

Shinagawa, S. (2013). Endogenous fluctuations with procyclical R&D. Economic Modelling, 30 , 274–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECONMOD.2012.09.024

Shleifer, A. (1986). Implementation cycles. Journal of Political Economy, 94 (6), 1163–1190.

Sokolov-Mladenović, S., Cvetanović, S., & Mladenović, I. (2016). R&D expenditure and economic growth: EU28 evidence for the period 2002–2012. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 29 (1), 1005–1020. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2016.1211948

Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70 (1), 65–94.

Solow, R. M. (1957). Technical change and the aggregate production function. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 39 (3), 312. https://doi.org/10.2307/1926047

Szarowská, I. (2017). Does public R&D expenditure matter for economic growth? Journal of International Studies , 10 (2).

Tachi, R., & Walker, R. (1993). The contemporary Japanese economy: An overview . University of Tokyo Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=8FkU46ZQX6QC

Tucker, I. B. (2001). Survey of economics . South-Western College Pub. https://books.google.com/books?id=b156VLO24TcC

Wälde, K. (2002). The economic determinants of technology shocks in a real business cycle model. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 27 (1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1889(01)00018-5

Wälde, K. (2005). Endogenous growth cycles. International Economic Review , 46 (3), 867–894. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3663496

Wood, D., & Wood, D. C. (2010). Economic action in theory and practice: Anthropological investigations . Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=Hs6x76L2EJ8C

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, Pakhtunkhwa Economic Policy Research Institute (PEPRI), Faculty of Business and Economics, Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan, Mardan, Pakistan

Manzoor Ahmad & Zahoor Ul Haq

Institute of Business Studies and Leadership, Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan, Mardan, Pakistan

Shehzad Khan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Manzoor Ahmad .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Ahmad, M., Haq, Z.U. & Khan, S. Business Cycles and the Dynamics of Innovation: a Theoretical Perspective. J Knowl Econ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01155-6

Download citation

Received : 09 October 2021

Accepted : 21 February 2023

Published : 04 March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01155-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- R&D expenditures

- Technological innovation

- Business cycles

- Economic growth

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

A look at small businesses in the U.S.

Most U.S. adults (86%) say small businesses have a positive effect on the way things are going in the country these days, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey . Small businesses, in fact, receive by far the most positive reviews of any of the nine U.S. institutions we asked about, outranking even the military and churches.

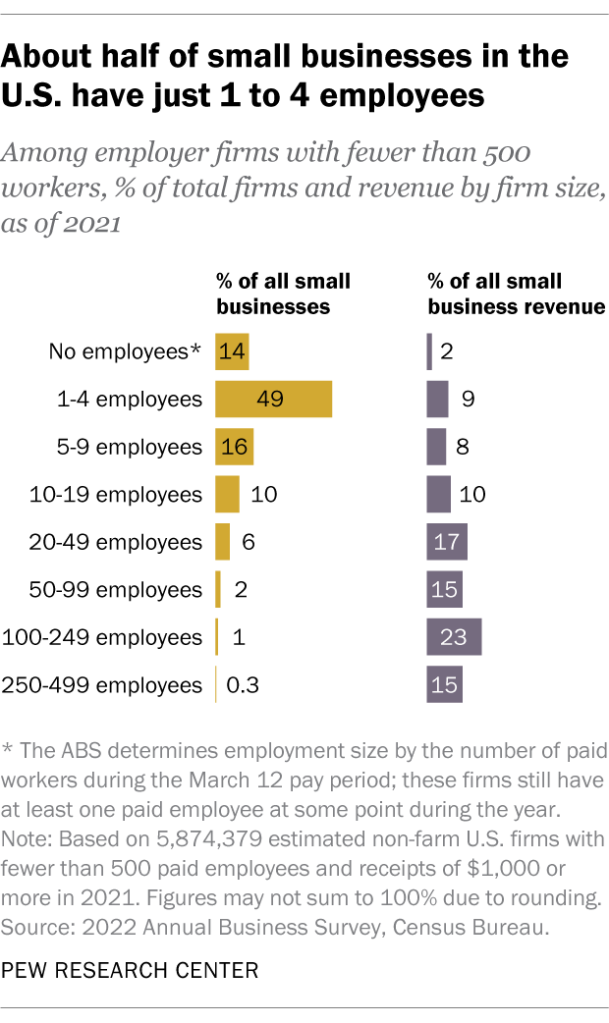

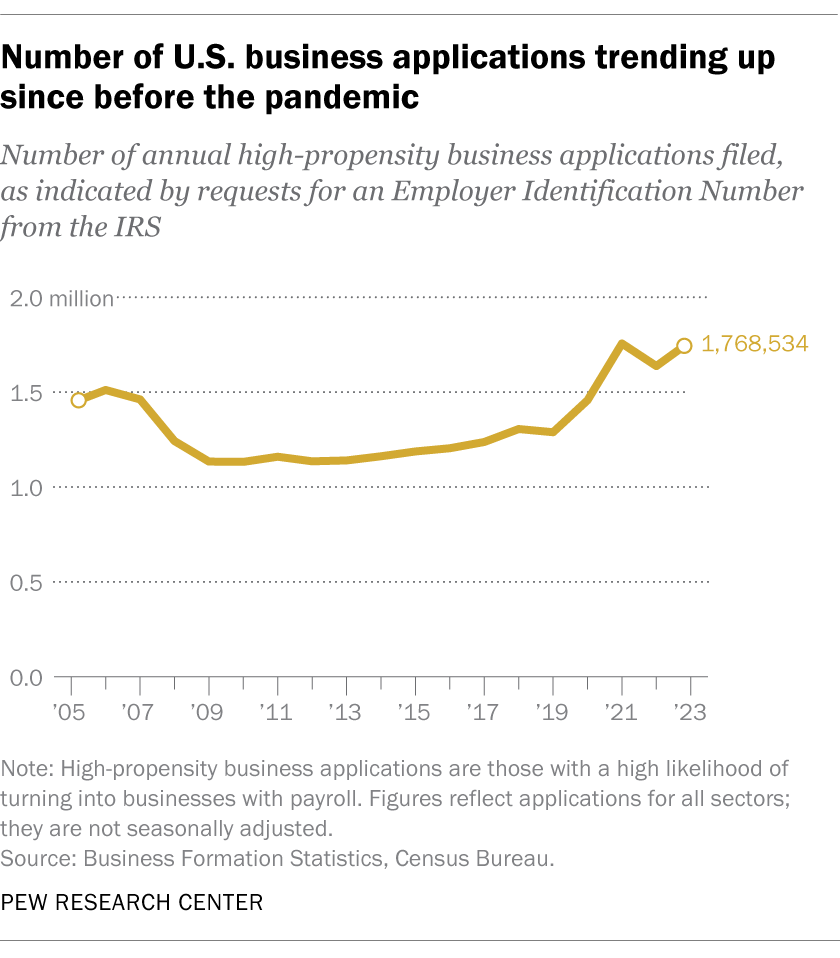

Despite their name, small businesses loom large in the United States. These businesses – defined here as those with 500 employees or fewer – account for 99.9% of U.S. firms, according to the Small Business Administration . While most of these 33 million firms don’t have paid employees, about 6 million of them do . They account for just under half of total private sector employment (46%).