- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

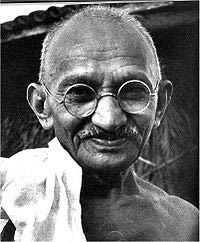

Mahatma Gandhi

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 6, 2019 | Original: July 30, 2010

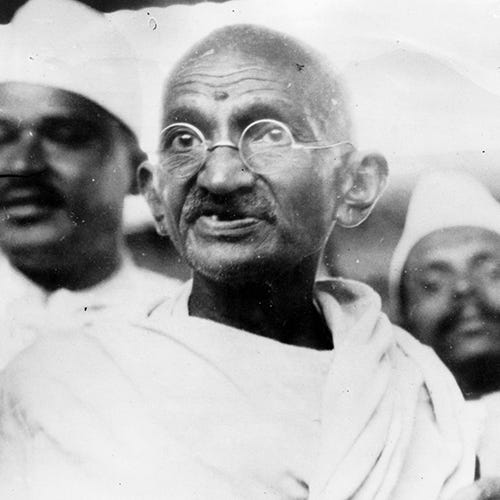

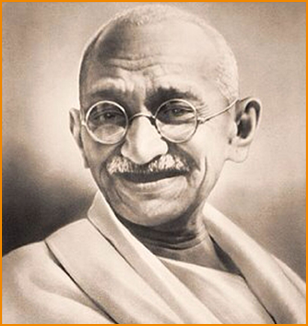

Revered the world over for his nonviolent philosophy of passive resistance, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was known to his many followers as Mahatma, or “the great-souled one.” He began his activism as an Indian immigrant in South Africa in the early 1900s, and in the years following World War I became the leading figure in India’s struggle to gain independence from Great Britain. Known for his ascetic lifestyle–he often dressed only in a loincloth and shawl–and devout Hindu faith, Gandhi was imprisoned several times during his pursuit of non-cooperation, and undertook a number of hunger strikes to protest the oppression of India’s poorest classes, among other injustices. After Partition in 1947, he continued to work toward peace between Hindus and Muslims. Gandhi was shot to death in Delhi in January 1948 by a Hindu fundamentalist.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, at Porbandar, in the present-day Indian state of Gujarat. His father was the dewan (chief minister) of Porbandar; his deeply religious mother was a devoted practitioner of Vaishnavism (worship of the Hindu god Vishnu), influenced by Jainism, an ascetic religion governed by tenets of self-discipline and nonviolence. At the age of 19, Mohandas left home to study law in London at the Inner Temple, one of the city’s four law colleges. Upon returning to India in mid-1891, he set up a law practice in Bombay, but met with little success. He soon accepted a position with an Indian firm that sent him to its office in South Africa. Along with his wife, Kasturbai, and their children, Gandhi remained in South Africa for nearly 20 years.

Did you know? In the famous Salt March of April-May 1930, thousands of Indians followed Gandhi from Ahmadabad to the Arabian Sea. The march resulted in the arrest of nearly 60,000 people, including Gandhi himself.

Gandhi was appalled by the discrimination he experienced as an Indian immigrant in South Africa. When a European magistrate in Durban asked him to take off his turban, he refused and left the courtroom. On a train voyage to Pretoria, he was thrown out of a first-class railway compartment and beaten up by a white stagecoach driver after refusing to give up his seat for a European passenger. That train journey served as a turning point for Gandhi, and he soon began developing and teaching the concept of satyagraha (“truth and firmness”), or passive resistance, as a way of non-cooperation with authorities.

The Birth of Passive Resistance

In 1906, after the Transvaal government passed an ordinance regarding the registration of its Indian population, Gandhi led a campaign of civil disobedience that would last for the next eight years. During its final phase in 1913, hundreds of Indians living in South Africa, including women, went to jail, and thousands of striking Indian miners were imprisoned, flogged and even shot. Finally, under pressure from the British and Indian governments, the government of South Africa accepted a compromise negotiated by Gandhi and General Jan Christian Smuts, which included important concessions such as the recognition of Indian marriages and the abolition of the existing poll tax for Indians.

In July 1914, Gandhi left South Africa to return to India. He supported the British war effort in World War I but remained critical of colonial authorities for measures he felt were unjust. In 1919, Gandhi launched an organized campaign of passive resistance in response to Parliament’s passage of the Rowlatt Acts, which gave colonial authorities emergency powers to suppress subversive activities. He backed off after violence broke out–including the massacre by British-led soldiers of some 400 Indians attending a meeting at Amritsar–but only temporarily, and by 1920 he was the most visible figure in the movement for Indian independence.

Leader of a Movement

As part of his nonviolent non-cooperation campaign for home rule, Gandhi stressed the importance of economic independence for India. He particularly advocated the manufacture of khaddar, or homespun cloth, in order to replace imported textiles from Britain. Gandhi’s eloquence and embrace of an ascetic lifestyle based on prayer, fasting and meditation earned him the reverence of his followers, who called him Mahatma (Sanskrit for “the great-souled one”). Invested with all the authority of the Indian National Congress (INC or Congress Party), Gandhi turned the independence movement into a massive organization, leading boycotts of British manufacturers and institutions representing British influence in India, including legislatures and schools.

After sporadic violence broke out, Gandhi announced the end of the resistance movement, to the dismay of his followers. British authorities arrested Gandhi in March 1922 and tried him for sedition; he was sentenced to six years in prison but was released in 1924 after undergoing an operation for appendicitis. He refrained from active participation in politics for the next several years, but in 1930 launched a new civil disobedience campaign against the colonial government’s tax on salt, which greatly affected Indian’s poorest citizens.

A Divided Movement

In 1931, after British authorities made some concessions, Gandhi again called off the resistance movement and agreed to represent the Congress Party at the Round Table Conference in London. Meanwhile, some of his party colleagues–particularly Mohammed Ali Jinnah, a leading voice for India’s Muslim minority–grew frustrated with Gandhi’s methods, and what they saw as a lack of concrete gains. Arrested upon his return by a newly aggressive colonial government, Gandhi began a series of hunger strikes in protest of the treatment of India’s so-called “untouchables” (the poorer classes), whom he renamed Harijans, or “children of God.” The fasting caused an uproar among his followers and resulted in swift reforms by the Hindu community and the government.

In 1934, Gandhi announced his retirement from politics in, as well as his resignation from the Congress Party, in order to concentrate his efforts on working within rural communities. Drawn back into the political fray by the outbreak of World War II , Gandhi again took control of the INC, demanding a British withdrawal from India in return for Indian cooperation with the war effort. Instead, British forces imprisoned the entire Congress leadership, bringing Anglo-Indian relations to a new low point.

Partition and Death of Gandhi

After the Labor Party took power in Britain in 1947, negotiations over Indian home rule began between the British, the Congress Party and the Muslim League (now led by Jinnah). Later that year, Britain granted India its independence but split the country into two dominions: India and Pakistan. Gandhi strongly opposed Partition, but he agreed to it in hopes that after independence Hindus and Muslims could achieve peace internally. Amid the massive riots that followed Partition, Gandhi urged Hindus and Muslims to live peacefully together, and undertook a hunger strike until riots in Calcutta ceased.

In January 1948, Gandhi carried out yet another fast, this time to bring about peace in the city of Delhi. On January 30, 12 days after that fast ended, Gandhi was on his way to an evening prayer meeting in Delhi when he was shot to death by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu fanatic enraged by Mahatma’s efforts to negotiate with Jinnah and other Muslims. The next day, roughly 1 million people followed the procession as Gandhi’s body was carried in state through the streets of the city and cremated on the banks of the holy Jumna River.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi was the primary leader of India’s independence movement and also the architect of a form of non-violent civil disobedience that would influence the world. He was assassinated by Hindu extremist Nathuram Godse.

(1869-1948)

Who Was Mahatma Gandhi?

Mahatma Gandhi was the leader of India’s non-violent independence movement against British rule and in South Africa who advocated for the civil rights of Indians. Born in Porbandar, India, Gandhi studied law and organized boycotts against British institutions in peaceful forms of civil disobedience. He was killed by a fanatic in 1948.

Early Life and Education

Indian nationalist leader Gandhi (born Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi) was born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, Kathiawar, India, which was then part of the British Empire.

Gandhi’s father, Karamchand Gandhi, served as a chief minister in Porbandar and other states in western India. His mother, Putlibai, was a deeply religious woman who fasted regularly.

Young Gandhi was a shy, unremarkable student who was so timid that he slept with the lights on even as a teenager. In the ensuing years, the teenager rebelled by smoking, eating meat and stealing change from household servants.

Although Gandhi was interested in becoming a doctor, his father hoped he would also become a government minister and steered him to enter the legal profession. In 1888, 18-year-old Gandhi sailed for London, England, to study law. The young Indian struggled with the transition to Western culture.

Upon returning to India in 1891, Gandhi learned that his mother had died just weeks earlier. He struggled to gain his footing as a lawyer. In his first courtroom case, a nervous Gandhi blanked when the time came to cross-examine a witness. He immediately fled the courtroom after reimbursing his client for his legal fees.

Gandhi’s Religion and Beliefs

Gandhi grew up worshiping the Hindu god Vishnu and following Jainism, a morally rigorous ancient Indian religion that espoused non-violence, fasting, meditation and vegetarianism.

During Gandhi’s first stay in London, from 1888 to 1891, he became more committed to a meatless diet, joining the executive committee of the London Vegetarian Society, and started to read a variety of sacred texts to learn more about world religions.

Living in South Africa, Gandhi continued to study world religions. “The religious spirit within me became a living force,” he wrote of his time there. He immersed himself in sacred Hindu spiritual texts and adopted a life of simplicity, austerity, fasting and celibacy that was free of material goods.

Gandhi in South Africa

After struggling to find work as a lawyer in India, Gandhi obtained a one-year contract to perform legal services in South Africa. In April 1893, he sailed for Durban in the South African state of Natal.

When Gandhi arrived in South Africa, he was quickly appalled by the discrimination and racial segregation faced by Indian immigrants at the hands of white British and Boer authorities. Upon his first appearance in a Durban courtroom, Gandhi was asked to remove his turban. He refused and left the court instead. The Natal Advertiser mocked him in print as “an unwelcome visitor.”

Nonviolent Civil Disobedience

A seminal moment occurred on June 7, 1893, during a train trip to Pretoria, South Africa, when a white man objected to Gandhi’s presence in the first-class railway compartment, although he had a ticket. Refusing to move to the back of the train, Gandhi was forcibly removed and thrown off the train at a station in Pietermaritzburg.

Gandhi’s act of civil disobedience awoke in him a determination to devote himself to fighting the “deep disease of color prejudice.” He vowed that night to “try, if possible, to root out the disease and suffer hardships in the process.”

From that night forward, the small, unassuming man would grow into a giant force for civil rights. Gandhi formed the Natal Indian Congress in 1894 to fight discrimination.

Gandhi prepared to return to India at the end of his year-long contract until he learned, at his farewell party, of a bill before the Natal Legislative Assembly that would deprive Indians of the right to vote. Fellow immigrants convinced Gandhi to stay and lead the fight against the legislation. Although Gandhi could not prevent the law’s passage, he drew international attention to the injustice.

After a brief trip to India in late 1896 and early 1897, Gandhi returned to South Africa with his wife and children. Gandhi ran a thriving legal practice, and at the outbreak of the Boer War, he raised an all-Indian ambulance corps of 1,100 volunteers to support the British cause, arguing that if Indians expected to have full rights of citizenship in the British Empire, they also needed to shoulder their responsibilities.

In 1906, Gandhi organized his first mass civil-disobedience campaign, which he called “Satyagraha” (“truth and firmness”), in reaction to the South African Transvaal government’s new restrictions on the rights of Indians, including the refusal to recognize Hindu marriages.

After years of protests, the government imprisoned hundreds of Indians in 1913, including Gandhi. Under pressure, the South African government accepted a compromise negotiated by Gandhi and General Jan Christian Smuts that included recognition of Hindu marriages and the abolition of a poll tax for Indians.

Return to India

In 1915 Gandhi founded an ashram in Ahmedabad, India, that was open to all castes. Wearing a simple loincloth and shawl, Gandhi lived an austere life devoted to prayer, fasting and meditation. He became known as “Mahatma,” which means “great soul.”

Opposition to British Rule in India

In 1919, with India still under the firm control of the British, Gandhi had a political reawakening when the newly enacted Rowlatt Act authorized British authorities to imprison people suspected of sedition without trial. In response, Gandhi called for a Satyagraha campaign of peaceful protests and strikes.

Violence broke out instead, which culminated on April 13, 1919, in the Massacre of Amritsar. Troops led by British Brigadier General Reginald Dyer fired machine guns into a crowd of unarmed demonstrators and killed nearly 400 people.

No longer able to pledge allegiance to the British government, Gandhi returned the medals he earned for his military service in South Africa and opposed Britain’s mandatory military draft of Indians to serve in World War I.

Gandhi became a leading figure in the Indian home-rule movement. Calling for mass boycotts, he urged government officials to stop working for the Crown, students to stop attending government schools, soldiers to leave their posts and citizens to stop paying taxes and purchasing British goods.

Rather than buy British-manufactured clothes, he began to use a portable spinning wheel to produce his own cloth. The spinning wheel soon became a symbol of Indian independence and self-reliance.

Gandhi assumed the leadership of the Indian National Congress and advocated a policy of non-violence and non-cooperation to achieve home rule.

After British authorities arrested Gandhi in 1922, he pleaded guilty to three counts of sedition. Although sentenced to a six-year imprisonment, Gandhi was released in February 1924 after appendicitis surgery.

He discovered upon his release that relations between India’s Hindus and Muslims devolved during his time in jail. When violence between the two religious groups flared again, Gandhi began a three-week fast in the autumn of 1924 to urge unity. He remained away from active politics during much of the latter 1920s.

Gandhi and the Salt March

Gandhi returned to active politics in 1930 to protest Britain’s Salt Acts, which not only prohibited Indians from collecting or selling salt—a dietary staple—but imposed a heavy tax that hit the country’s poorest particularly hard. Gandhi planned a new Satyagraha campaign, The Salt March , that entailed a 390-kilometer/240-mile march to the Arabian Sea, where he would collect salt in symbolic defiance of the government monopoly.

“My ambition is no less than to convert the British people through non-violence and thus make them see the wrong they have done to India,” he wrote days before the march to the British viceroy, Lord Irwin.

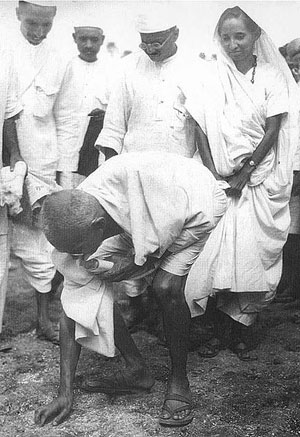

Wearing a homespun white shawl and sandals and carrying a walking stick, Gandhi set out from his religious retreat in Sabarmati on March 12, 1930, with a few dozen followers. By the time he arrived 24 days later in the coastal town of Dandi, the ranks of the marchers swelled, and Gandhi broke the law by making salt from evaporated seawater.

The Salt March sparked similar protests, and mass civil disobedience swept across India. Approximately 60,000 Indians were jailed for breaking the Salt Acts, including Gandhi, who was imprisoned in May 1930.

Still, the protests against the Salt Acts elevated Gandhi into a transcendent figure around the world. He was named Time magazine’s “Man of the Year” for 1930.

Gandhi was released from prison in January 1931, and two months later he made an agreement with Lord Irwin to end the Salt Satyagraha in exchange for concessions that included the release of thousands of political prisoners. The agreement, however, largely kept the Salt Acts intact. But it did give those who lived on the coasts the right to harvest salt from the sea.

Hoping that the agreement would be a stepping-stone to home rule, Gandhi attended the London Round Table Conference on Indian constitutional reform in August 1931 as the sole representative of the Indian National Congress. The conference, however, proved fruitless.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S MAHATMA GANDHI FACT CARD

Protesting "Untouchables" Segregation

Gandhi returned to India to find himself imprisoned once again in January 1932 during a crackdown by India’s new viceroy, Lord Willingdon. He embarked on a six-day fast to protest the British decision to segregate the “untouchables,” those on the lowest rung of India’s caste system, by allotting them separate electorates. The public outcry forced the British to amend the proposal.

After his eventual release, Gandhi left the Indian National Congress in 1934, and leadership passed to his protégé Jawaharlal Nehru . He again stepped away from politics to focus on education, poverty and the problems afflicting India’s rural areas.

India’s Independence from Great Britain

As Great Britain found itself engulfed in World War II in 1942, Gandhi launched the “Quit India” movement that called for the immediate British withdrawal from the country. In August 1942, the British arrested Gandhi, his wife and other leaders of the Indian National Congress and detained them in the Aga Khan Palace in present-day Pune.

“I have not become the King’s First Minister in order to preside at the liquidation of the British Empire,” Prime Minister Winston Churchill told Parliament in support of the crackdown.

With his health failing, Gandhi was released after a 19-month detainment in 1944.

After the Labour Party defeated Churchill’s Conservatives in the British general election of 1945, it began negotiations for Indian independence with the Indian National Congress and Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s Muslim League. Gandhi played an active role in the negotiations, but he could not prevail in his hope for a unified India. Instead, the final plan called for the partition of the subcontinent along religious lines into two independent states—predominantly Hindu India and predominantly Muslim Pakistan.

Violence between Hindus and Muslims flared even before independence took effect on August 15, 1947. Afterwards, the killings multiplied. Gandhi toured riot-torn areas in an appeal for peace and fasted in an attempt to end the bloodshed. Some Hindus, however, increasingly viewed Gandhi as a traitor for expressing sympathy toward Muslims.

Gandhi’s Wife and Kids

At the age of 13, Gandhi wed Kasturba Makanji, a merchant’s daughter, in an arranged marriage. She died in Gandhi’s arms in February 1944 at the age of 74.

In 1885, Gandhi endured the passing of his father and shortly after that the death of his young baby.

In 1888, Gandhi’s wife gave birth to the first of four surviving sons. A second son was born in India 1893. Kasturba gave birth to two more sons while living in South Africa, one in 1897 and one in 1900.

Assassination of Mahatma Gandhi

On January 30, 1948, 78-year-old Gandhi was shot and killed by Hindu extremist Nathuram Godse, who was upset at Gandhi’s tolerance of Muslims.

Weakened from repeated hunger strikes, Gandhi clung to his two grandnieces as they led him from his living quarters in New Delhi’s Birla House to a late-afternoon prayer meeting. Godse knelt before the Mahatma before pulling out a semiautomatic pistol and shooting him three times at point-blank range. The violent act took the life of a pacifist who spent his life preaching nonviolence.

Godse and a co-conspirator were executed by hanging in November 1949. Additional conspirators were sentenced to life in prison.

Even after Gandhi’s assassination, his commitment to nonviolence and his belief in simple living — making his own clothes, eating a vegetarian diet and using fasts for self-purification as well as a means of protest — have been a beacon of hope for oppressed and marginalized people throughout the world.

Satyagraha remains one of the most potent philosophies in freedom struggles throughout the world today. Gandhi’s actions inspired future human rights movements around the globe, including those of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. in the United States and Nelson Mandela in South Africa.

Martin Luther King

"],["

Winston Churchill

Nelson Mandela

"]]" tml-render-layout="inline">

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Mahatma Gandhi

- Birth Year: 1869

- Birth date: October 2, 1869

- Birth City: Porbandar, Kathiawar

- Birth Country: India

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Mahatma Gandhi was the primary leader of India’s independence movement and also the architect of a form of non-violent civil disobedience that would influence the world. Until Gandhi was assassinated in 1948, his life and teachings inspired activists including Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela.

- Civil Rights

- Astrological Sign: Libra

- University College London

- Samaldas College at Bhavnagar, Gujarat

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- As a young man, Mahatma Gandhi was a poor student and was terrified of public speaking.

- Gandhi formed the Natal Indian Congress in 1894 to fight discrimination.

- Gandhi was assassinated by Hindu extremist Nathuram Godse, who was upset at Gandhi’s tolerance of Muslims.

- Gandhi's non-violent civil disobedience inspired future world leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela.

- Death Year: 1948

- Death date: January 30, 1948

- Death City: New Delhi

- Death Country: India

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Mahatma Gandhi Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/political-figures/mahatma-gandhi

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: September 4, 2019

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- An eye for an eye only ends up making the whole world blind.

- Victory attained by violence is tantamount to a defeat, for it is momentary.

- Religions are different roads converging to the same point. What does it matter that we take different roads, so long as we reach the same goal? In reality, there are as many religions as there are individuals.

- The weak can never forgive. Forgiveness is the attribute of the strong.

- To call woman the weaker sex is a libel; it is man's injustice to woman.

- Truth alone will endure, all the rest will be swept away before the tide of time.

- A man is but the product of his thoughts. What he thinks, he becomes.

- There are many things to do. Let each one of us choose our task and stick to it through thick and thin. Let us not think of the vastness. But let us pick up that portion which we can handle best.

- An error does not become truth by reason of multiplied propagation, nor does truth become error because nobody sees it.

- For one man cannot do right in one department of life whilst he is occupied in doing wrong in any other department. Life is one indivisible whole.

- If we are to reach real peace in this world and if we are to carry on a real war against war, we shall have to begin with children.

Assassinations

The Manhunt for John Wilkes Booth

Indira Gandhi

Alexei Navalny

Martin Luther King Jr.

James Earl Ray

Malala Yousafzai

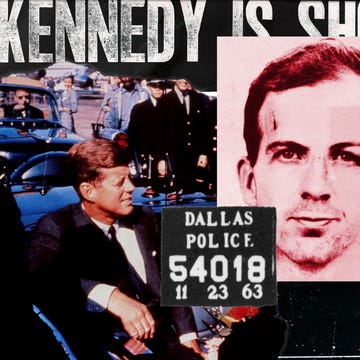

Who Killed JFK? You Won’t Believe Us Anyway

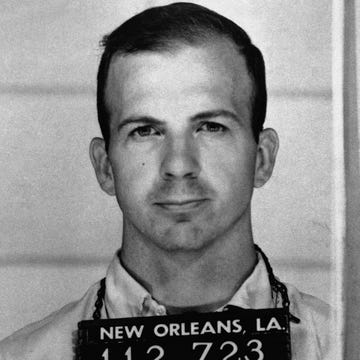

Lee Harvey Oswald

John F. Kennedy

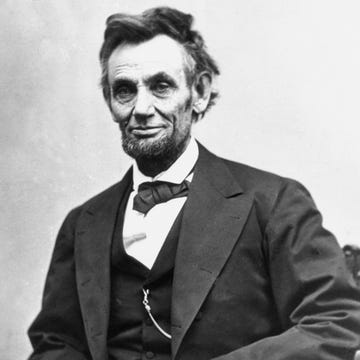

Abraham Lincoln

Biography Online

Mahatma Gandhi Biography

Mahatma Gandhi was a prominent Indian political leader who was a leading figure in the campaign for Indian independence. He employed non-violent principles and peaceful disobedience as a means to achieve his goal. He was assassinated in 1948, shortly after achieving his life goal of Indian independence. In India, he is known as ‘Father of the Nation’.

“When I despair, I remember that all through history the ways of truth and love have always won. There have been tyrants, and murderers, and for a time they can seem invincible, but in the end they always fall. Think of it–always.”

Short Biography of Mahatma Gandhi

Around this time, he also studied the Bible and was struck by the teachings of Jesus Christ – especially the emphasis on humility and forgiveness. He remained committed to the Bible and Bhagavad Gita throughout his life, though he was critical of aspects of both religions.

Gandhi in South Africa

On completing his degree in Law, Gandhi returned to India, where he was soon sent to South Africa to practise law. In South Africa, Gandhi was struck by the level of racial discrimination and injustice often experienced by Indians. In 1893, he was thrown off a train at the railway station in Pietermaritzburg after a white man complained about Gandhi travelling in first class. This experience was a pivotal moment for Gandhi and he began to represent other Indias who experienced discrimination. As a lawyer he was in high demand and soon he became the unofficial leader for Indians in South Africa. It was in South Africa that Gandhi first experimented with campaigns of civil disobedience and protest; he called his non-violent protests satyagraha . Despite being imprisoned for short periods of time, he also supported the British under certain conditions. During the Boer war, he served as a medic and stretcher-bearer. He felt that by doing his patriotic duty it would make the government more amenable to demands for fair treatment. Gandhi was at the Battle of Spion serving as a medic. An interesting historical anecdote, is that at this battle was also Winston Churchill and Louis Botha (future head of South Africa) He was decorated by the British for his efforts during the Boer War and Zulu rebellion.

Gandhi and Indian Independence

After 21 years in South Africa, Gandhi returned to India in 1915. He became the leader of the Indian nationalist movement campaigning for home rule or Swaraj .

Gandhi also encouraged his followers to practise inner discipline to get ready for independence. Gandhi said the Indians had to prove they were deserving of independence. This is in contrast to independence leaders such as Aurobindo Ghose , who argued that Indian independence was not about whether India would offer better or worse government, but that it was the right for India to have self-government.

Gandhi also clashed with others in the Indian independence movement such as Subhas Chandra Bose who advocated direct action to overthrow the British.

Gandhi frequently called off strikes and non-violent protest if he heard people were rioting or violence was involved.

In 1930, Gandhi led a famous march to the sea in protest at the new Salt Acts. In the sea, they made their own salt, in violation of British regulations. Many hundreds were arrested and Indian jails were full of Indian independence followers.

“With this I’m shaking the foundations of the British Empire.”

– Gandhi – after holding up a cup of salt at the end of the salt march.

However, whilst the campaign was at its peak some Indian protesters killed some British civilians, and as a result, Gandhi called off the independence movement saying that India was not ready. This broke the heart of many Indians committed to independence. It led to radicals like Bhagat Singh carrying on the campaign for independence, which was particularly strong in Bengal.

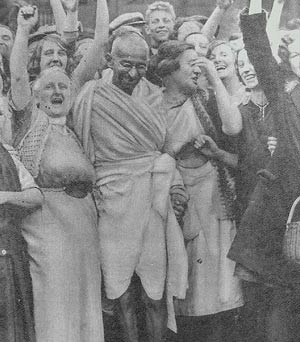

In 1931, Gandhi was invited to London to begin talks with the British government on greater self-government for India, but remaining a British colony. During his three month stay, he declined the government’s offer of a free hotel room, preferring to stay with the poor in the East End of London. During the talks, Gandhi opposed the British suggestions of dividing India along communal lines as he felt this would divide a nation which was ethnically mixed. However, at the summit, the British also invited other leaders of India, such as BR Ambedkar and representatives of the Sikhs and Muslims. Although the dominant personality of Indian independence, he could not always speak for the entire nation.

Gandhi’s humour and wit

During this trip, he visited King George in Buckingham Palace, one apocryphal story which illustrates Gandhi’s wit was the question by the king – what do you think of Western civilisation? To which Gandhi replied

“It would be a good idea.”

Gandhi wore a traditional Indian dress, even whilst visiting the king. It led Winston Churchill to make the disparaging remark about the half naked fakir. When Gandhi was asked if was sufficiently dressed to meet the king, Gandhi replied

“The king was wearing clothes enough for both of us.”

Gandhi once said he if did not have a sense of humour he would have committed suicide along time ago.

Gandhi and the Partition of India

After the war, Britain indicated that they would give India independence. However, with the support of the Muslims led by Jinnah, the British planned to partition India into two: India and Pakistan. Ideologically Gandhi was opposed to partition. He worked vigorously to show that Muslims and Hindus could live together peacefully. At his prayer meetings, Muslim prayers were read out alongside Hindu and Christian prayers. However, Gandhi agreed to the partition and spent the day of Independence in prayer mourning the partition. Even Gandhi’s fasts and appeals were insufficient to prevent the wave of sectarian violence and killing that followed the partition.

Away from the politics of Indian independence, Gandhi was harshly critical of the Hindu Caste system. In particular, he inveighed against the ‘untouchable’ caste, who were treated abysmally by society. He launched many campaigns to change the status of untouchables. Although his campaigns were met with much resistance, they did go a long way to changing century-old prejudices.

At the age of 78, Gandhi undertook another fast to try and prevent the sectarian killing. After 5 days, the leaders agreed to stop killing. But ten days later Gandhi was shot dead by a Hindu Brahmin opposed to Gandhi’s support for Muslims and the untouchables.

Gandhi and Religion

Gandhi was a seeker of the truth.

“In the attitude of silence the soul finds the path in a clearer light, and what is elusive and deceptive resolves itself into crystal clearness. Our life is a long and arduous quest after Truth.”

Gandhi said his great aim in life was to have a vision of God. He sought to worship God and promote religious understanding. He sought inspiration from many different religions: Jainism, Islam, Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism and incorporated them into his own philosophy.

On several occasions, he used religious practices and fasting as part of his political approach. Gandhi felt that personal example could influence public opinion.

“When every hope is gone, ‘when helpers fail and comforts flee,’ I find that help arrives somehow, from I know not where. Supplication, worship, prayer are no superstition; they are acts more real than the acts of eating, drinking, sitting or walking. It is no exaggeration to say that they alone are real, all else is unreal.”

– Gandhi Autobiography – The Story of My Experiments with Truth

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of Mahatma Gandhi” , Oxford, UK. www.biographyonline.net 12th Jan 2011. Last updated 1 Feb 2020.

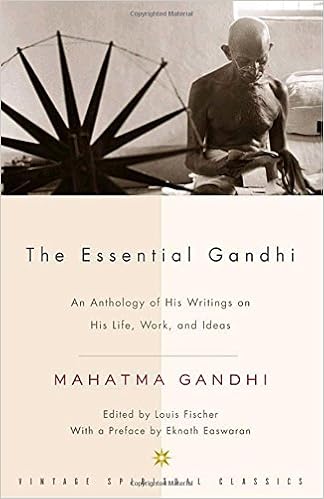

The Essential Gandhi

The Essential Gandhi: An Anthology of His Writings on His Life, Work, and Ideas at Amazon

Gandhi: An Autobiography – The Story of My Experiments With Truth at Amazon

Related pages

Indian men and women involved in the Independence Movement.

- Nehru Biography

He stood out in his time in history. Non violence as he practised it was part of his spiritual learning usedvas a political tool. How can one say he wasn’t a good lawyer or he wasn’t a good leader when he had such a following and he was part of the negotiations thar brought about Indian Independance? I just dipped into this ti find out about the salt march.:)

- February 09, 2019 9:31 AM

- By Lakmali Gunawardena

mahatma gandhi was a good person but he wasn’t all good because when he freed the indian empire the partition grew between the muslims and they fought .this didn’t happen much when the british empire was in control because muslims and hindus had a common enemy to unite against.

I am not saying the british empire was a good thing.

- January 01, 2019 3:24 PM

- By marcus carpenter

Dear very nice information Gandhi ji always inspired us thanks a lot.

- October 01, 2018 1:40 PM

FATHER OF NATION

- June 03, 2018 8:34 AM

Gandhi was a lawyer who did not make a good impression as a lawyer. His success and influence was mediocre in law religion and politics. He rose to prominence by chance. He was neither a good lawyer or a leader circumstances conspired at a time in history for him to stand out as an astute leader both in South Africa and in India. The British were unable to control the tidal wave of independence in all the countries they ruled at that time. Gandhi was astute enough to seize the opportunity and used non violence as a tool which had no teeth but caused sufficient concern for the British to negotiate and hand over territories which they had milked dry.

- February 09, 2018 2:30 PM

- By A S Cassim

By being “astute enough to seize the opportunity” and not being pushed down/ defeated by an Empire, would you agree this is actually the reason why Gandhi made a good impression as a leader? Also, despite his mediocre success and influence as you mentioned, would you agree the outcome of his accomplishments are clearly a demonstration he actually was relevant to law, religion and politics?

- November 23, 2018 12:45 AM

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

Gandhiji’s life, ideas and work are of crucial importance to all those who want a better life for humankind. The political map of the world has changed dramatically since his time, the economic scenario has witnessed unleashing of some disturbing forces, and the social set-up has undergone a tremendous change. The importance of moral and ethical issues raised by him, however, remain central to the future of individuals and nations. We can still derive inspiration from the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi who wanted us to remember the age old saying, “In spite of death, life persists, and in spite of hatred, love persists.” Rabindranath Tagore addressed him as ‘Mahatma’ and the latter called the poet “Gurudev’. Subhash Chandra Bose had called him ‘Father of the Nation’ in his message on Hind Azad Radio.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, at Porbandar, a small town in Gujarat, on the sea coast of Western India. He was born in the distinguished family of administrators. His grandfather had risen to be the Dewan or Prime Minister of Porbandar and was succeeded by his father Karamchand Gandhiji .His mother Putlibai, a religious person, had a major contribution in moulding the character of young Mohan.

He studied initially at an elementary school in Porbandar and then at primary and high schools in Rajkot, one of the important cities of Gujarat. Though he called himself a ‘mediocre student’, he gave evidence of his reasoning, intelligence, deep faith in the principles of truth and discipline at very young age. He was married, at the age of thirteen, when still in high school, to Kasturbai who was of the same age, and had four sons named Harilal, Ramdas, Manilal and Devdas. His father died in 1885. At that time Gandhiji was studying at Samaldas College in Bhavnagar. It was hoped that his (Mohandas’s) going to England and qualifying as a barrister would help his family to lead more comfortable life.

He sailed to England on September 4, 1888 at the age of 18, and was enrolled in The Inner Temple. It was a new world for young Mohan and offered immense opportunities to explore new ideas and to reflect on the philosophy and religion of his own country. He got deeply interested in vegetarianism and study of different religions. His stay in England provided opportunities for widening horizons and better understanding of religions and cultures. He passed his examinations and was called to Bar on June 10, 1891. After two days he sailed for India.

He made unsuccessful attempts to establish his legal practice at Rajkot and Bombay. An offer from Dada Abdulla & Company to go to South Africa to instruct their consul in a law suit opened up a new chapter in his life. In South Africa, Mohandas tasted bitter experience of racial discrimination during his journey from Durban to Pretoria, where his presence was required in connection with a lawsuit. At Maritzburg station he was pushed out from first class compartment of the train because he was ‘coloured’ Shivering in cold and sitting in the waiting room of Maritzburg station, he decided that it was cowardice to run away instead he would fight for his rights. With this incident evolved the concept of Satyagraha. He united the Indians settled in South Africa of different communities, languages and religions, and founded Natal Indian Congress in 1893. He founded Indian Opinion, his first journal, in 1904 to promote the interests of Indians in South Africa. Influenced by John Ruskin’s Unto This Last, he set up Phoenix Ashram near Durban, where inmates did manual labour and lived a community living.

Gandhiji organized a protest in 1906 against unfair Asiatic Regulation Bill of 1906. Again in 1908, he mobilsed Indian community in South Africa against the discriminatory law requiring Asians to apply for the registration by burning 2000 official certificates of domicile at a public meeting at Johannesburg and courting jail. He established in May 1910 Tolstoy Farm, near Johannesburg on the similar ideals of Phoenix Ashram.

In 1913, to protest against the imposition of 3 Pound tax and passing immigration Bill adversely affecting the status of married women, he inspired Kasturbai and Indian women to join the struggle. Gandhi organized a march from New Castle to Transvaal without permit and courting arrest. Gandhi had sailed to South Africa as a young inexperienced barrister in search of fortune. But he returned to India in 1915 as Mahatma.

As advised by Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Gandhiji spent one year travelling in India and studying India and her people. In 1915 when Gandhiji returned from South Africa he had established his ashram at Kochrab near Ahmedabad. Now after year’s travel, Gandhiji moved his ashram on the banks of Sabarmati River near Ahmedabad and called it Satyagraha Ashram.

His first Satyagraha in India was at Champaran, Bihar in 1917 for the rights of peasants on indigo plantations. When British Government ordered Gandhiji to leave Champaran, he defied the order by declaring that “British could not order me about in my own country”. The magistrate postponed the trial and released him without bail and the case against him was withdrawn. In Champaran, he taught the poor and illiterate people the principles of Satyagraha. Gandhiji and his volunteers instructed the peasants in elementary hygiene and ran schools for their children.

In Ahmedabad, there was a dispute between mill workers and mill owners. The legitimate demands of workers were refused by mill owners. Gandhiji asked the workers to strike work, on condition that they took pledge to remain non-violent. Gandhiji fasted in support of workers. At the end of 3 days both the parties agreed on arbitration. Same year in 1918, Gandhiji led a Satyagraha for the peasants of Kheda in Gujarat.

In 1919, he called for Civil Disobedience against Rowlatt Bill. This non-cooperation movement was the first nationwide movement on national scale. However, the violence broke out; Gandhiji had to suspend the movement as people were not disciplined enough. He realized that people had to be trained for non violent agitation. Same year he started his weeklies Young India in English and Navajivan in Gujarati.

In 1921, Gandhiji took to wearing loin cloth to identify himself with poor masses and to propagate khadi, hand spun cloth. He also started Swadeshi movement, advocating the use of commodities made in the country. He asked the Indians to boycott foreign cloth and promote hand spun khadi thus creating work for the villagers. He devoted himself to the propagation of Hindu-Muslim unity, removal of untouchablity, equality of women and men, and khadi. These were important issues in his agenda of constructive work – essential programmes to go with Satyagraha.

On March 12 1930, Gandhiji set out with 78 volunteers on historic Salt March from Sabarmati Ashram; Ahmedabad to Dandi, a village on the sea coast .This was an important non violent movement of Indian freedom struggle. At Dandi Gandhiji picked up handful of salt thus technically ‘producing’ the salt. He broke the law, which had deprived the poor man of his right to make salt .This simple act was immediately followed by a nation-wide defiance of the law. Gandhiji was arrested on May 4. Within weeks thousands of men and women were imprisoned, challenging the authority of the colonial rulers.

In March 1931, Gandhi-Irwin Pact was signed to solve some constitutional issues, and this ended the Civil Disobedience. On August 29, 1931 Gandhiji sailed to London to attend Round Table Conference to have a discussion with the British. The talks however were unsuccessful. In September 1932, Gandhiji faced the complex issue of the British rulers agreeing for the separate electorates for untouchables. He went on fast to death in protest and concluded only after the British accepted Poona Pact.

In 1933, he started weekly publication of Harijan replacing Young India. Aspirations of the people for freedom under Gandhi’s leadership were rising high. In 1942 Gandhiji launched an individual Satyagraha. Nearly 23 thousand people were imprisoned that year. The British mission, headed by Sir Stafford Cripps came with new proposals but it did not meet with any success.

The historic Quit India resolution was passed by the Congress on 8th August 1942. Gandhiji’s message of ‘Do or Die’ engulfed millions of Indians. Gandhiji and other Congress leaders were imprisoned in Aga Khan Palace near Pune. This period in prison was of bereavement for Gandhiji. He first lost his trusted secretary and companion Mahadev Desai on 15th August 1942. Destiny gave another cruel blow to Gandhiji, when Kasturbai, his wife and companion for 62 years, died on 22 February 1944.

Gandhiji was released from prison as his health was on decline. Unfortunately, political developments had moved favouring the partition of the country resulting in communal riots on a frightful scale. Gandhiji was against the partition and chose to be with the victims of riots in East Bengal and Bihar. On 15 August 1947, when India became independent, free from the British rule, Gandhiji fasted and prayed in Calcutta.

On 30th January 1948, Gandhiji, on his way to the prayer meeting at Birla House, New Delhi, fell to the bullets fired by Nathuram Vinayak Godse.

As observed by Louis Fischer, “Millions in all countries mourned Gandhi’s death as a personal loss. They did not quite know why; they did not quite know what he stood for. But he was ‘a good man’ and good men are rare.

Mahatma Gandhi Biography: From Humble Beginnings to Global Icon

Mahatma Gandhi, also known as Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi , was a prominent leader, political activist and spiritual guide in India’s struggle for independence from British rule. His life and teachings continue to inspire millions around the world, making him an icon of peace, nonviolence and social change. In this beginner’s guide, we’ll delve into various aspects of Mahatma Gandhi’s life, from his early days and remarkable achievements to his unique leadership style and profound influence on India’s history.

Mahatma Gandhi Biography

Mahatma Gandhi Early Life

First of all, let us trace the early life and background of Mahatma Gandhi . He was born on October 2, 1869, in the coastal city of Porbandar in present-day Gujarat, India. Gandhiji was from a simple family and his father was serving as the Chief Minister of the local princely state. As a young boy, he displayed an inclination towards truthfulness and moral values, which shaped the foundation of his character.

Achievements of Mahatma Gandhi

Second, the life of Mahatma Gandhi is replete with many achievements that shaped the course of India’s history. One of his most notable achievements was leading a non-violent civil disobedience movement against British colonial rule, known as the Salt March, which became a turning point in the fight for independence. Gandhi’s efforts also led to important reforms, such as the Civil Disobedience Movement, the Quit India Movement and the successful Dandi March, all of which contributed to India’s independence.

Mahatma Gandhi Leadership Style

Furthermore, Mahatma Gandhi’s leadership style was characterized by his unwavering commitment to truth, non-violence and self-discipline. He advocated “Satyagraha”, a unique philosophy of passive resistance where individuals peacefully protested against injustice and oppression. Gandhi believed that nonviolent resistance could bring about social change without resorting to violence, and he used this approach to organize the masses and challenge the British Raj.

Mahatma Gandhi nonviolent resistance

Furthermore, central to Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy was the principle of nonviolent resistance. He believed that love and compassion could overcome hatred and violence, leading to a more harmonious society. Gandhiji’s nonviolent protests and hunger strikes gained widespread attention and support, forcing the British to engage in negotiations, and eventually India’s independence in 1947.

Mahatma Gandhi’s impact on India

Another important aspect of Mahatma Gandhi’s life was his profound influence on the history and culture of India. His tireless efforts in advocating human rights, promoting social equality and upliftment of the oppressed classes left an indelible mark on the nation. Gandhi’s teachings influenced various leaders and movements around the world, including Martin Luther King Jr., Nelson Mandela, and the Civil Rights Movement in the United States.

Continuing the legacy of Mahatma Gandhi

Finally, Mahatma Gandhi’s legacy lives on today and continues to inspire generations for truth, non-violence and social justice. His unwavering commitment to these principles not only transformed India but also served as a guiding light for the global fight against oppression and injustice. As we reflect on his life, we can draw valuable lessons from Mahatma Gandhi’s journey and apply them to our own lives, creating a better and more compassionate world for all.

Q1: When and where was Mahatma Gandhi born?

A1: Mahatma Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, a coastal town in present-day Gujarat, India.

Q2: What is Mahatma Gandhi’s full name?

A2: Mahatma Gandhi’s full name is Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

Q3: What were Mahatma Gandhi’s early life and upbringing like?

A3: Mahatma Gandhi hailed from a modest family and displayed a penchant for truthfulness and moral values from a young age. His father served as a chief minister in the local princely state.

Q4: What significant role did Mahatma Gandhi play in India’s independence movement?

A4: Mahatma Gandhi led various nonviolent civil disobedience movements against British colonial rule, including the Salt March and the Quit India Movement, which played a pivotal role in India’s struggle for independence.

Q5: What is the philosophy of nonviolent resistance, and how did Gandhi use it in his activism?

A5: The philosophy of nonviolent resistance, or “Satyagraha,” was central to Gandhi’s approach. He believed that peaceful protests and passive resistance could bring about societal change without resorting to violence.

Q6: What were Mahatma Gandhi’s notable achievements during his lifetime?

A6: Some of Mahatma Gandhi’s notable achievements include leading India to independence, advocating for human rights, promoting social equality, and inspiring civil rights movements globally.

Q7: How did Mahatma Gandhi’s leadership style differ from other leaders of his time?

A7: Gandhi’s leadership style was characterized by his unwavering commitment to truth, nonviolence, and self-discipline, setting him apart from many other leaders who used force or aggression.

Q8: How did Mahatma Gandhi’s teachings influence other global leaders and movements?

A8: Mahatma Gandhi’s principles of nonviolent resistance inspired leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela, as well as civil rights movements in various parts of the world.

Q9: What were the major challenges faced by Mahatma Gandhi during his activism?

A9: Gandhi faced numerous challenges, including imprisonment, opposition from colonial authorities, and internal disagreements within the Indian National Congress.

Q10: How is Mahatma Gandhi remembered and celebrated today?

A10: Mahatma Gandhi is revered as the “Father of India” and is celebrated worldwide for his teachings on peace, nonviolence, and civil rights. His birthday, October 2, is observed as the International Day of Non-Violence.

Muhammad Ali Biography

Queen Elizabeth II Biography

Abraham Lincoln Biography

One Comment

[…] Mahatma Gandhi Biography […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Mohandas Gandhi

- Occupation: Civil Rights Leader

- Born: October 2, 1869 in Porbandar, India

- Died: January 30, 1948 in New Delhi, India

- Best known for: Organizing non-violent civil rights protests

- The 1982 movie Gandhi won the Academy Award for best motion picture.

- His birthday is a national holiday in India . It is also the International Day of Non-Violence.

- He was the 1930 Time Magazine Man of the Year.

- Gandhi wrote a lot. The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi have 50,000 pages!

- He was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize five times.

- Listen to a recorded reading of this page:

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Mahatma Gandhi : a biography, complete and unabridged

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

114 Previews

4 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

EPUB and PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station47.cebu on September 18, 2020

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

- Mahatma Gandhi Biography and Political Career

Biography of Mahatma Gandhi (Father of Nation)

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi , more popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi . His birth place was in the small city of Porbandar in Gujarat (October 2, 1869 - January 30, 1948). Mahatma Gandhi's father's name was Karamchand Gandhi, and his mother's name was Putlibai Gandhi. He was a politician, social activist, Indian lawyer, and writer who became the prominent Leader of the nationwide surge movement against the British rule of India. He came to be known as the Father of The Nation. October 2, 2023, marks Gandhi Ji’s 154th birth anniversary , celebrated worldwide as International Day of Non-Violence, and Gandhi Jayanti in India.

Gandhi Ji was a living embodiment of non-violent protests (Satyagraha) to achieve independence from the British Empire's clutches and thereby achieve political and social progress. Gandhi Ji is considered ‘The Great Soul’ or ‘ The Mahatma ’ in the eyes of millions of his followers worldwide. His fame spread throughout the world during his lifetime and only increased after his demise. Mahatma Gandhi , thus, is the most renowned person on earth.

Education of Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi's education was a major factor in his development into one of the finest persons in history. Although he attended a primary school in Porbandar and received awards and scholarships there, his approach to his education was ordinary. Gandhi joined Samaldas College in Bhavnagar after passing his matriculation exams at the University of Bombay in 1887.

Gandhiji's father insisted he become a lawyer even though he intended to be a docto. During those days, England was the centre of knowledge, and he had to leave Smaladas College to pursue his father's desire. He was adamant about travelling to England despite his mother's objections and his limited financial resources.

Finally, he left for England in September 1888, where he joined Inner Temple, one of the four London Law Schools. In 1890, he also took the matriculation exam at the University of London.

When he was in London, he took his studies seriously and joined a public speaking practice group. This helped him get over his nervousness so he could practise law. Gandhi had always been passionate about assisting impoverished and marginalised people.

Mahatma Gandhi During His Youth

Gandhi was the youngest child of his father's fourth wife. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was the dewan Chief Minister of Porbandar, the then capital of a small municipality in western India (now Gujarat state) under the British constituency.

Gandhi's mother, Putlibai, was a pious religious woman.Mohandas grew up in Vaishnavism, a practice followed by the worship of the Hindu god Vishnu, along with a strong presence of Jainism, which has a strong sense of non-violence.Therefore, he took up the practice of Ahimsa (non-violence towards all living beings), fasting for self-purification, vegetarianism, and mutual tolerance between the sanctions of various castes and colours.

His adolescence was probably no stormier than most children of his age and class. Not until the age of 18 had Gandhi read a single newspaper. Neither as a budding barrister in India nor as a student in England nor had he shown much interest in politics. Indeed, he was overwhelmed by terrifying stage fright each time he stood up to read a speech at a social gathering or to defend a client in court.

In London, Gandhiji's vegetarianism missionary was a noteworthy occurrence. He became a member of the executive committee in joined the London Vegetarian Society. He also participated in several conferences and published papers in its journal. Gandhi met prominent Socialists, Fabians, and Theosophists like Edward Carpenter, George Bernard Shaw, and Annie Besant while dining at vegetarian restaurants in England.

Political Career of Mahatma Gandhi

When we talk about Mahatma Gandhi’s political career, in July 1894, when he was barely 25, he blossomed overnight into a proficient campaigner . He drafted several petitions to the British government and the Natal Legislature signed by hundreds of his compatriots. He could not prevent the passage of the bill but succeeded in drawing the attention of the public and the press in Natal, India, and England to the Natal Indian's problems.

He still was persuaded to settle down in Durban to practice law and thus organised the Indian community. The Natal Indian Congress was founded in 1894, and he became the unwearying secretary. He infused a solidarity spirit in the heterogeneous Indian community through that standard political organisation. He gave ample statements to the Government, Legislature, and media regarding Indian Grievances.

Finally, he got exposed to the discrimination based on his colour and race, which was pre-dominant against the Indian subjects of Queen Victoria in one of her colonies, South Africa.

Mahatma Gandhi spent almost 21 years in South Africa. But during that time, there was a lot of discrimination because of skin colour. Even on the train, he could not sit with white European people. But he refused to do so, got beaten up, and had to sit on the floor. So he decided to fight against these injustices, and finally succeeded after a lot of struggle.

It was proof of his success as a publicist that such vital newspapers as The Statesman, Englishman of Calcutta (now Kolkata) and The Times of London editorially commented on the Natal Indians' grievances.

In 1896, Gandhi returned to India to fetch his wife, Kasturba (or Kasturbai), their two oldest children, and amass support for the Indians overseas. He met the prominent leaders and persuaded them to address the public meetings in the centre of the country's principal cities.

Unfortunately for him, some of his activities reached Natal and provoked its European population. Joseph Chamberlain, the colonial secretary in the British Cabinet, urged Natal's government to bring the guilty men to proper jurisdiction, but Gandhi refused to prosecute his assailants. He said he believed the court of law would not be used to satisfy someone's vendetta.

Political Teacher of Mahatma Gandhi

Gopal Krishna Gokhale was one of the prominent political teachers and mentors of Mahatma Gandhi. Gokhale, a renowned Indian nationalist leader, played a significant role in shaping Gandhi's political ideology and approach to leadership. He emphasized the importance of nonviolence, constitutional methods, and constructive work in achieving social and political change. Gandhi referred to Gokhale as his political guru and credited him with influencing many of his principles and strategies in the Indian freedom struggle. Gokhale's teachings and guidance had a profound impact on Gandhi's development as a leader and advocate for India's independence.

Death of Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi's death was a tragic event and brought clouds of sorrow to millions of people. On the 29th of January, a man named Nathuram Godse came to Delhi with an automatic pistol. About 5 pm in the afternoon of the next day, he went to the Gardens of Birla house, and suddenly, a man from the crowd came out and bowed before him.

Then Godse fired three bullets at his chest and stomach, who was Mahatma Gandhi. Gandhi was in such a posture that he to the ground. During his death, he uttered: “Ram! Ram!” Although someone could have called the doctor in this critical situation during that time, no one thought of that, and Gandhiji died within half an hour.

How Shaheed Day is Celebrated at Gandhiji’s Samadhi (Raj Ghat)?

As Gandhiji died on January 30, the government of India declared this day as ‘Shaheed Diwas’.

On this day, the President, the Vice-President, the Prime Minister, and the Defence Minister every year gather at the Samadhi of Mahatma Gandhi at the Raj Ghat memorial in Delhi to pay tribute to Indian martyrs and Mahatma Gandhi, followed by a two-minute silence.

On this day, many schools host events where students perform plays and sing patriotic songs. Martyrs' Day is also observed on March 23 to honour the lives and sacrifices of Sukhdev Thapar, Shivaram Rajguru, and Bhagat Singh.

Gandhi believed it was his duty to defend India's rights. Mahatma Gandhi had a significant role in attaining India's independence from the British. He had an impact on many individuals and locations outside India. Gandhi also influenced Martin Luther King, and as a result, African-Americans now have equal rights. Peacefully winning India's independence, he altered the course of history worldwide.

FAQs on Mahatma Gandhi Biography and Political Career

1. What was people's reaction after Nathuram Godse killed Mahatma Gandhi?

When Nathuram Godse killed Mahatma Gandhi, people shouted to kill Nathuram. After killing Mahatma Gandhi, Nathuram Godse tried to kill himself but could not do so since the police seized his weapons and took him to jail. After that, Gandhiji's body was laid in the garden with a white cloth covered on his face. All the lights were turned off in honour of him. Then on the radio, honourable Prime minister Pandit Nehru Ji declared sadly that the Nation's Father was no more.

2. How vegetarianism impacted Mahatma Gandhi’s time in London?

During the three years he spent in England, he was in a great dilemma with personal and moral issues rather than academic ambitions.

The sudden transition from Porbandar's half-rural atmosphere to London's cosmopolitan life was not an easy task for him. And he struggled powerfully and painfully to adapt himself to Western food, dress, and etiquette, and he felt awkward.

His vegetarianism became a continual source of embarrassment and was like a curse to him; his friends warned him that it would disrupt his studies, health, and well-being. Fortunately, he came across a vegetarian restaurant and a book providing a well-defined defence of vegetarianism.

His missionary zeal for vegetarianism helped draw the pitifully shy youth out of his shell and gave him a new and robust personality. He also became a member of the London Vegetarian Society executive committee, contributing articles to its journal and attending conferences.

3. Who was the first person to write a biography of Mahatma Gandhi (Father of The Nation)?

Christian missionary Joseph Doke had written the first biography of Bapu. The best part is that Gandhiji had still not acquired the status of Mahatma when this biography was written.

4. Who was Gandhiji’s favorite writer?

Gandhiji’s favorite writer was Leo Tolstoy.

5. What is Mahatma Gandhi’s date of birth?

Mahatma Gandhi's date of birth is October 2, 1869. We celebrate every year on October 2nd as Mahatma Gandhi Jayanti.

6. Which are the famous Mahatma Gandhi books?

Mahatma Gandhi authored several influential books and writings that have left a lasting impact on the world. Some of his famous books include:

Autobiography

Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule

Satyagraha in South Africa

Young India

The Essential Gandhi

These books reflect Gandhi's deep commitment to nonviolence, truth, and social justice, making them essential reads for those interested in his life and principles.

April 28, 2024

Life Story of Famous People

Short Bio » Civil Rights Leader » Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was the preeminent leader of the Indian independence movement in British-ruled India. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on 2 October 1869 to a Hindu Modh Baniya family in Porbandar (also known as Sudamapuri ), a coastal town on the Kathiawar Peninsula and then part of the small princely state of Porbandar in the Kathiawar Agency of the Indian Empire. Employing nonviolent civil disobedience, Gandhi led India to independence and inspired movements for civil rights and freedom across the world.

Gandhi famously led Indians in challenging the British-imposed salt tax with the 400 km (250 mi) Dandi Salt March in 1930, and later in calling for the British to Quit India in 1942. He was imprisoned for many years, upon many occasions, in both South Africa and India. One of Gandhi’s major strategies, first in South Africa and then in India, was uniting Muslims and Hindus to work together in opposition to British imperialism. In 1919–22 he won strong Muslim support for his leadership in the Khilafat Movement to support the historic Ottoman Caliphate. By 1924, that Muslim support had largely evaporated.

Time magazine named Gandhi the Man of the Year in 1930. Gandhi was also the runner-up to Albert Einstein as “Person of the Century” at the end of 1999. The Government of India awarded the annual Gandhi Peace Prize to distinguished social workers, world leaders and citizens. Nelson Mandela, the leader of South Africa’s struggle to eradicate racial discrimination and segregation, was a prominent non-Indian recipient. In 2011, Time magazine named Gandhi as one of the top 25 political icons of all time. Gandhi did not receive the Nobel Peace Prize, although he was nominated five times between 1937 and 1948, including the first-ever nomination by the American Friends Service Committee, though he made the short list only twice, in 1937 and 1947.

Indians widely describe Gandhi as the father of the nation. In 2007, the United Nations General Assembly declared Gandhi’s birthday 2 October as “the International Day of Nonviolence.

More Info: Wiki

Fans Also Viewed

Published in Historical Figure

More Celebrities

Who was Mahatma Gandhi? (Short biography)

1. biography.

Mahatma Gandhi was an Indian lawyer, politician, and thinker of the nineteenth and twentieth century. He was known mainly for claiming sovereignty and leading the independence of India through nonviolent methods . He was born on October 2, 1869 and died on January 30, 1948.

1.1. Childhood

Gandhi was born in Porbandar, a small coastal city in western India, son of Karamchand Gandhi (the city’s prime minister) and Putlibai Gandhi. His mother was one of his most important influences in his life. From her, Gandhi learned respect for living beings, the virtues of vegetarianism, and tolerance towards different ways of thinking, even towards other creeds and religions.

At eighteen Gandhi moved to London to study law at University College London. When he finished his studies he returned to Bombay to try to practice as a lawyer, but the over-saturation of the profession at that time coupled with the lack of real experience in the courts made it impossible for him to succeed. Luckily, during that same year (1893) he was presented with the opportunity to work in South Africa which he accepted the job on the spot. He was motivated by the resistance struggle and non-violent civil disobedience that his compatriots were carrying out in the face of pressure and discrimination from the country towards the Hindu people.

1.3. Years in South Africa

In South Africa, Gandhi saw first hand the strong rejection and hatred towards the Hindus, which motivated him to create an Indian political party to defend their rights in 1894. After 22 years of nonviolent protests in South Africa, Gandhi gained enough power and respect to negotiate with South African General Jan Christian Smuts in order to find a solution to the Indian conflict.

1.4. Return to India

In 1915 Gandhi returned to India, where he continued to promulgate his religious, philosophical and political values. During these years in India, two great social protests stood out: The March of the Salt (1930) and The Vindication of the Independence of the India of the British empire in the time frame of the Second World War (1939-1945). The latter, involuntarily involving India in the war as a British dependency, together with all the years of nonviolent struggle, finally led to the official independence of India on August 15, 1947.

A few months later, on January 30, 1948, Gandhi was assassinated by Nathuram Godse, an ultra-right Hindu fanatic. Godse was an extremist who wanted to establish Hinduism as the one and only acceptable religion. On the other hand, Gandhi, although a supporter of Hinduism, was accepting of other religions and beliefs. Godse saw Gandhi as an obstacle to his own political agenda and thus to defend this ideology of an egalitarian society, Gandhi was murdered at the age of 78.

2. GANDHI DOCUMENTARY

3. REFERENCES

- Saberespractico.com (2018). ¿Quién fue Gandhi? ¿Qué hizo? (Resumen) . Text in Spanish. Avaliable [ HERE ].

- Krishna – Youtube.com (2014). Mahatma Gandhi Documentary. Avaliable [ HERE ].

- Unknown – Wikimedia Commons (1930). Gandhi portrait . Original image avaliable [ HERE ].

Learner Trip

PhD in Education. I've been sharing all kind of content/information on the Internet for 14+ years now. I try to do it in the most straightforward and reliable way possible, cross-referencing information with the primary sources of authority in each field (unless unnecessary). You can reach out to me in the comments. I read all your inquiries and typically respond to most of them daily. If you find what I do helpful, you can support me here . 🙂

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Don't subscribe All new comments Replies to my comments Notify me of followup comments via e-mail. You can also subscribe without commenting.

- Get Featured

- Our Patreon

- Biographies

Mahatma Gandhi: Biography, Beliefs, Religion

The biography of Mahatma Gandhi presents an intricate journey of a man deeply rooted in his beliefs and principles. His life story showcases a blend of spiritual, philosophical, and political endeavors that had profound impacts within and beyond religion. Across diverse contexts, Gandhi’s name resonates with notions of peace, nonviolence, and resilience. Dive into the comprehensive narrative of this influential figure and understand the ethos that defined his path.

Table of Contents

Biography Summary

Early Life and Education Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, better known as Mahatma Gandhi, was born on October 2, 1869, and tragically died on January 30, 1948. A beacon of peace and nonviolence, Gandhi was an exemplary figure who battled colonial subjugation and heralded India’s independence from oppressive British rule. His unwavering dedication to nonviolent resistance was instrumental in inspiring movements for civil rights and freedom on a global scale.

South African Sojourn

In the coastal state of Gujarat, within a devout Hindu family, Gandhi’s roots were planted. His legal proficiency was honed at the Inner Temple, London, where he achieved his accolade of being called to the bar in June 1891 at the age of 22. Struggling to cultivate a successful law practice in India, Gandhi sought opportunities in South Africa in 1893, representing an Indian merchant in legal matters. South Africa became his home for 21 years, where he not only nurtured a family but also cultivated the strategy of nonviolent resistance as a weapon against injustice and discrimination.

Return to India and National Leadership

1915 marked his return to India, and at 45, Gandhi embarked on a mission to consolidate peasants, farmers, and laborers, championing causes against discrimination and excessive land tax. Steering the Indian National Congress in 1921, his leadership illuminated paths toward mitigating poverty, broadening women’s rights, fostering religious and ethnic harmony, and terminating untouchability. With the embodiment of swaraj or self-rule as his objective, Gandhi became a paragon of simplicity, adopting a lifestyle resonating with the underprivileged.

Defiance Against British Rule

In a defining moment of defiance against British rule, Gandhi spearheaded the 400 km Dandi Salt March in 1930, challenging the stringent British salt tax. His clarion call for the British to “Quit India” echoed through the nation in 1942. Despite numerous incarcerations in South Africa and India, Gandhi’s spirit remained unyielding.

Partition and the Struggle for Peace

As the winds of freedom began to blow across the Indian subcontinent in the early 1940s, they carried with them the storms of partition, driven by the burgeoning demand for a separate Muslim homeland. The twilight of British rule in August 1947 unfurled the dawn of independence, heralding the birth of India and Pakistan. A crucible of turbulence, upheaval, and religious animosity ensued, marring the euphoria of emancipation with the stains of violence and bloodshed.

Gandhi, who envisioned an India resonating with religious pluralism, became a crucible of solace and peace, endeavoring tirelessly to assuage the tempests of violence and discord. Embarking on several hunger strikes, his life became an epitome of sacrifice aimed at halting the horrific religious carnage. His journey, however, was tragically ended by the bullets of Nathuram Godse, a militant Hindu nationalist, on January 30, 1948.

Remembered and revered as the Father of the Nation in the tapestry of post-colonial India, Gandhi’s legacy is enshrined in his unyielding devotion to peace and nonviolence. The global canvas commemorates his birth on October 2 as Gandhi Jayanti and the International Day of Nonviolence, celebrating the luminary who illuminated pathways towards peace, tolerance, and harmony.

Early Life and Background

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, a coastal town on the Kathiawar Peninsula in the then princely state of Porbandar, part of the Kathiawar Agency of the British Raj. He was born into a Gujarati Hindu Modh Bania family with a prominent status in the region. His father, Karamchand Uttamchand Gandhi (1822–1885), held the esteemed Porbandar state’s dewan (chief minister) position, contributing actively to the governance and administration despite having a modest educational background.

The familial lineage of the Gandhis originated from Kutiana village in what was then the Junagadh State. Karamchand, Gandhi’s father, was particularly experienced in state administration, and his influential tenure included a remarriage with Putlibai (1844–1891), who became an essential figure in the family and Gandhi’s life. This union produced several children, with Mohandas being the youngest, born in a rather humble setting within the Gandhi family residence.

Childhood Influences and Education

Gandhi’s early years were marked by a blend of traditional Indian stories and diverse religious exposure, pivotal in shaping his moral compass and philosophical standings. His internalization of truth and love as supreme virtues was profoundly influenced by epic Indian classics, leaving an indelible mark on his conscience and thought processes. A salient feature of Gandhi’s upbringing was the eclectic religious atmosphere at home, rooted in Hindu traditions, enriched with teachings from various texts like the Bhagavad Gita, the Bhagavata Purana, and several others, offering him a well-rounded spiritual foundation.