Är artikeln peer reviewed?

Peer review är en process där vetenskapliga publikationer läses och granskas av ämnesexperter innan de accepteras för publicering. Sammanfattningsvis kan man säga att det är en form av kvalitetsgranskning som säkrar att den publicerade forskningen håller en hög standard.

Det finns olika sätt att se om en artikel är peer-reviewed (expertgranskad):

- På tidskriftens webbplats. Informationen kan finnas t e x under rubriker som ”Journal Information” eller ”About the journal”. Men hittar man ingen information där behöver det inte nödvändigtvis betyda att artikeln inte är peer-reviewed, det finns fler sätt att gå vidare för att kontrollera detta. Tänk också på att tidskrifter innehåller generellt ett antal olika dokumenttyper. Ledare, brev, nyheter och kommentarer utgör en del av de dokumenttyper som kan inkluderas i en tidskrift utan att ha genomgått en strukturerad peer-review process.

- Ett andra sätt att se om en artikel är peer-reviewed eller inte är att söka upp tidskriften i databasen Ulrichsweb som innehåller detaljerad information om över 300 000 tidskrifter av olika typer. Ulrichweb är tillgänglig via vår databaslista. När du sökt fram en tidskrift finns det en flik som heter ”Additional title details” där det kan finnas information om en tidskrift är peer-reviewed. Detta illustreras antingen genom att det står ”refereed” eller "peer-reviewed". Dock gäller samma sak här som ovan, det vill säga att, även om det inte står något om peer-review behöver det inte nödvändigtvis betyda att tidskriften inte är peer-reviewed.

- Ett tredje sätt att undersöka huruvida en artikel är peer-reviewed eller inte är att det i vissa databaser finns en möjlighet att avgränsa sig till peer-review. PubMed har tyvärr ingen funktion där information om peer-review förekommer. De flesta tidskrifter i PubMed är peer-reviewed men vill man vara säker på om en tidskrift är peer-reviewed får man ta reda på detta genom att gå till någon annan källa. En databas som erbjuder information om peer-review är CINAHL .

På en hel del artiklar står det något i stil med ”Accepted” eller ”Submitted”, följt av ett datum. I många fall har dessa artiklar genomgått peer-review, men det är ingen absolut garanti för att så är fallet. Det kan betyda att artikeln blivit accepterad för publicering utan att ha gått igenom en peer-review process. En sista möjlig utväg är att kontakta tidskriften eller förlaget och be dem svara på om tidskriften och artikeln ifråga är peer-reviewed.

Information om 300 000 tidskrifter och e-tidskrifter med innehållsförteckningar, dagstidningar, nyhetsblad, med mera.

Om du vill att vi ska kontakta dig angående din feedback, var god ange dina kontaktuppgifter i formuläret nedan

- For students

View your schedule and courses

Edit content at umu.se

- Find courses and programmes

- Library search tool

- Search the legal framework

Scholarly articles and other publications

As a student, you will come across different types of academic texts. Here you can find information on how to recognise scholarly articles and many other publications. You can also read about how the peer review system works.

Various types of scholarly publications

Publishing and disseminating research are essential parts of the scientific process. The type of publications differs from one discipline to another. In medicine, it is common for researchers to write articles and publish them in scientific journals, while in the humanities, researchers more often write books (monographs) or chapters in anthologies. Other scientific publications include theses, conference papers, and research reports.

Knowing the difference between different research publications makes understanding what you have found when looking for material for your projects easier. It also makes it easier to refer to your sources correctly and to use them in the appropriate context.

Can I find research in non-scholarly publications?

Research results can also be presented in non-scholarly texts and publications. For example

- popular science books

- articles in newspapers

- debate articles in newspapers

- articles in popular science journals

- articles on websites.

These texts are considered second-hand sources. Sometimes they are written by the researcher and sometimes by others, such as communicators or science journalists. This type of text is often aimed at the general public.

Read more about judging whether a text is scholarly and credible: Evaluation of sources

Scholarly articles

Scholarly articles present the results of research studies and are written by researchers and doctoral students. The primary target audience is other researchers. Often the researchers aim to share their research internationally. This means that scholarly articles often

- contains technical terms and specialised language

- are written in English.

For an article to be considered scholarly, it must

- be published in a scientific journal

- have undergone peer review.

How do I recognise a scholarly article?

Many scholarly articles follow a standardised format called IMRaD, which stands for

- introduction

- material and method

- results and

- discussion.

In addition to these sections, references to the material referred to in the article are always included. The article often begins with a short abstract that you can use to decide whether the article is interesting to read in full.

Various types of scholarly articles

Original articles

In original articles, researchers present the results of their research. The results should be primary and based on the researcher's or research group's data collection.

Review articles

In review articles, researchers evaluate other studies and try to summarise the state of knowledge in an area. Review articles can vary in scope, but the focus is often on current literature. In a review article, the researchers have not conducted a study of their own. The results are instead based on a review of other articles.

Review articles sometimes present meta-analyses, which means that the researchers have statistically weighted the results of several other studies. This is common in medicine and in evaluating the effectiveness of drugs or treatments.

Articles that develop theories and methods

In theoretical articles, the researchers have not collected any data but try to develop new theories or methods based on existing theories and research.

A scholarly article is peer-reviewed before publication

A common feature of scholarly articles is that they are critically reviewed by other subject experts (referees) before they are accepted for publication. This is known as peer review. It is usually carried out by one or more researchers in the same field as the authors.

How does the peer review process work?

The review process varies from journal to journal, but a common approach is as follows:

- The researchers (article authors) submit a draft article to a journal.

- An editor of the journal assesses whether the article is interesting in terms of subject matter and whether it meets the basic requirements of language and content.

- The editor either rejects the draft or sends it for peer review.

- The reviewers assess the quality of the draft and the need for changes. Comments are then submitted to the editor.

- The editor either rejects the draft or suggests that the article authors make changes based on the reviewers' comments.

- Once the authors have submitted a revised version, the process is repeated until the editor either rejects or accepts the draft for publication.

Blind and double-blind review

The review should be as objective as possible and preferably not influenced by personal relationships between the reviewer and the author. To avoid pressure or bias, the review may be "blind" or "double-blind":

- If the review is blind, the authors do not know who is reviewing the manuscript.

- If the review is double-blind, both the authors and the reviewers are anonymous to each other.

A double-blind review is seen as better than a single-blind because the reviewer is not, or to a lesser extent, influenced by bias or preconceptions of the authors as individuals. Double-blind reviews might reduce the risk of discrimination based on gender and ethnicity.

Weaknesses of the peer review system

Since the reviewers are experts in the same field of research as the authors, they might also be competitors. This can make it difficult for reviewers to be impartial and anonymous. The smaller the research field, the more difficult to maintain anonymity. Although the peer review system has flaws, it is accepted as the best review system available today. A movement towards increased review transparency is currently underway to improve the review process.

Open peer review

Some publishers and journals are moving towards a more open review of articles to create increased transparency in the peer review process. The degree of openness may vary between journals but often involves openness in one or more of these three aspects:

- transparency about the identity of reviewers

- transparency in the review process where the reviewer's comments and the authors' responses are published with the article

- that the article is posted for open review so that anyone can review and comment on it.

Preprints (unreviewed versions of articles)

It is becoming increasingly common for researchers to make available a so-called preprint of their article before it has been reviewed and published in a scholarly journal. This means that the content of this version of the article is scientifically sound but not fact-checked.

Scholarly journals

Scholarly articles are usually published in scholarly journals by scientific publishers or associations. These journals often focus on a particular subject area and sometimes on a particular geographical region.

How do I know if a journal is scholarly?

On the journal's website, you can find information about the publisher, whether there is an editor (or editorial board) and whether the articles are peer-reviewed.

When searching for articles in databases or the library's search service, you can use features to limit your search to certain types of articles or scholarly journals. In the library search tool, you can select the "Peer-reviewed" filter to get hits only from journals with a peer review system.

Read more about evaluating different sources: Evaluation of sources

Tools for evaluating journals

Ulrichsweb - information about journals

Ulrichsweb is a service that collects detailed information about journals. Journals with a peer review system are listed in Ulrichsweb as "Refereed". In addition, you will find information about the journal's title, publisher, country, ISSN, format and whether the journal is active or discontinued.

More ways to evaluate journals

There are more ways to assess the quality and impact of journals. These methods are mainly used to compare different journals with each other and to analyse scholarly communication, but they can also be used as a quick way to determine whether a journal is scholarly. If the journal is included in Journal Citation Reports, Scopus Sources or the Norwegian register for scientific journals, it is scholarly.

Impact factors and journal rankings (Norwegian List, Journal Citation Reports and Scopus Sources)

The transformation of scholarly journals

The publication of scholarly journals has changed a lot over time.

- Previously, the journals were published in printed form, but today most of the journals are fully digital.

- The trend is from a subscription-based approach to open access content.

- Open access means that there is no cost to the reader to access the content. Instead, the cost of publishing is borne by the researcher or the institution.

- There is also a trend towards publishing research directly on a publishing platform, without being part of a journal.

- When the journals were printed, it was important to know in which issue an article was published to be able to find it again. Nowadays, the journal issue is mainly used when referring to the article.

More about open access journals: Open access journals

Other scholarly publications

Scholarly books and book chapters

Researchers can publish their research in book form in either monographs or anthologies. A monograph is a book with a well-defined subject and often no more than one or two authors. An anthology is a book of stand-alone chapters written by different researchers on different aspects of a broader topic. Anthologies often have one or more editors who compile the content. Publishing in books is common for researchers in the humanities and social sciences.

Usually, there is no peer review of scholarly books, but other things show whether the book is scientific:

- the authors are scientists

- the book is published by a publisher that focuses on scientific literature

- an editor has reviewed and approved the contributions

- there are references to other scientific publications and a list of them

- the target audience of the book is mainly other subject experts.

In a doctoral level programme, the doctoral student writes a scientific work called a thesis. The doctoral studies lead to a licentiate or doctoral degree. A doctoral degree involves four years of postgraduate stud ies, while a licentiate degree is awarded after two years of postgraduate studies. Approximately eighty percent of all research degrees are doctoral.

There are two different types of doctoral theses:

- A monographic thesis is a coherent book in a defined subject area.

- A compilation thesis consists of several scientific articles written by the doctoral student. The articles are given a context with a comprehensive summary, (called “kappa” in Swedish), which presents theories, methods, and previous research.

Conference proceedings

Conference papers are texts in which researchers present their research to other researchers, often at an early stage of the research process. The written conference contribution complements a talk given by the researcher at a conference. The contribution may resemble a scholarly article, but sometimes it is more of a summary of the lecture. The results presented are often preliminary, and conference papers can thus reflect current and ongoing research.

Conference papers may be published as appendices to scholarly journals or in special conference proceedings. Some conferences peer review papers before publication.

Many conferences also offer the opportunity to participate with a poster presenting a research result or project in text and images. Posters are very brief and not peer-reviewed.

Research reports

A research report is written by a researcher or research team and presents the results of a study or assignment. The research report can be published either by the institution where the researchers work or by the authority or organisation that commissioned the researchers. You can recognise a report by the fact that it is part of a series of reports or contains the word report in the title. Research reports are rarely peer-reviewed before publication.

Search paths for various scholarly sources

In the library's search tool, you can search for various types of publications such as books, journals, articles, theses, and reports. If you are searching in a specific subject area, it may be better to go directly to a subject specific database. Publications published at Umeå University are collected in the university's publication database, DiVA.

The library search tool

Articles, databases and journals

DiVA - publications from Umu

Films about scholarly publications

How can the process with peer review look like when a researcher is about to publish his/her research?

About different types of publications and how to find scientific material for connecting previous research to your work.

Basic course in information search

In our open online course, you will learn how to find scientific articles and other material for your studies.

Basic search techniques

Use different search techniques to perform better searches in the library search tool and other databases.

In-depth search strategies

You can use more in-depth strategies to search for information – for example when writing an essay.

Evaluation of sources

How do you know if a source is scientific? Ask questions about the material!

Questions about information searching?

Do you feel lost among databases and scholarly publications? Visit our drop-in sessions or make an appointment for a tutorial and we will help you. You can also submit short questions via chat or the contact form or ask the staff at the information desk.

Drop-in and lectures for students

Visit our drop-in sessions and ask your questions about information searching and evaluation of sources.

Schedule a tutoring appointment

Make an appointment for personal tutoring when you need more help with information searching.

Contact the library

Do you have a quick question about information searching? Please use our contact form or chat feature.

Nordic Journal of Vocational Education and Training

Current Issue

Peer-reviewed research articles, effects of coaching on wellbeing, perception of inclusion, and study-interest, praktisk yrkesopplæring på nett: en case-studie av yrkesfaglæreres undervisningspraksis under covid-19-pandemien [practical vocational training on the internet: a case study of vocational teachers’ teaching practice during the covid-19 pandemic], a holistic student-centred guidance framework supports finnish vocational education and training students in building competence identity.

The Nordic Journal of Vocational Education and Training (NJVET) invites original, scholarly articles that discuss the vocational and professional education and training, of young people as well as adults, from different academic disciplines, perspectives and traditions. It encourages diversity in theoretical and methodological approach and submissions from different parts of the world.

All published research articles in NJVET are subjected to a peer review process based on two moments of selection: an initial editorial screening and a double-blind review by at least two anonymous referees. Clarity and conciseness of thought are crucial requirements for publication. NJVET previously had a policy of single-blind review. The present policy was introduced in 2015.

NJVET is published on behalf of Nordyrk , a Nordic network for vocational education and training, and with support from NOP-HS and from the Swedish Research Council .

NJVET accepts submissions in English, Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish. To broaden the international readership, Nordic researchers are encouraged to submit and publish their contributions in English.

All articles in NJVET are open access and there are no submission charges or charges for article processing.

NJVET is included in DOAJ, the Directory of Open Access Journals. The journal is also accredited on level 1 according to the Norwegian accreditation of scientific journals, in the Finnish Publication Forum, and on Svenska listan - a register of peer-reviewed publication channels:

- Directory of Open Access Journals, DOAJ

- Norwegian Register for Scientific Journals, Series and Publishers

- The Finnish Publication Forum

- Svenska listan - a register of peer-reviewed publication channels

Call for papers:

NJVET has a continuous open call for papers within the aims and scope of the journal. In addition to this, there could be calls for contributions to special issues.

Upcoming publication of Special Issue on the cooperation between research, teaching and learning in VET

The relation and cooperation between on the one hand research on and in vocational education and training (VET) and on the other hand the teaching and learning in VET can be described as a theory and practice relation that can be challenging. It can also be seen as a way to make the research more relevant by identified needs and questions from vocational teachers.

The Special Issue aims to develop knowledge about the cooperation between research and education. Challenges in cooperation may be the role of the researcher in the educational context, the cooperation between researcher and vocational teachers or the process from defining the problem to implementing results. We especially welcome contributions that address questions such as: What is practice-based research? What´s in it for teachers and for researchers/the mutual benefit? What competence is required of the vocational teacher to be a part in practical research?

In collaboration with the editorial group of Nordic Journal of Vocational Education and Training , Susanne Gustavsson from University of Gothenburg, Sweden, Henriette Duch, VIA University College, Denmark, and Jóhannes Árnason, Akureyri Comprehensive College, Island, will act as guest editors.

Read more about the special issue.

Upcoming publication of Special Issue on Vocational classroom research with a focus on teaching and learning in vocational education subjects

This Special Issue aims to develop knowledge about how teaching in the vocational classroom can create productive conditions for students’ vocational learning and the development of students’ vocational knowledge in vocational subject areas. Contributions will address vocational (subject) didactic perspectives on teaching and learning in the vocational classroom; for example, this may concern vocational learning and vocational knowledge, embodied and material aspects, writing in the vocational classroom, practice-based school research, feedback/assessment in vocational subjects, and the relationship between theory and practice.

In collaboration with the editorial group of Nordic Journal of Vocational Education and Training, Stig-Börje Asplund, together with Nina Kilbrink and Ann-Britt Enochsson, Karlstad University, are acting as guest editors.

Make a Submission

Information.

- For Readers

- For Authors

2011–2024 © NJVET – Nordic Journal of Vocational Education and Training ISSN: 2242-458X

NJVET is published under the auspices of Linköping University Electronic Press (LiU E-Press).

Platform and Workflow by OJS / PKP

- Center for Arts, Business & Culture

- Publications

Peer Reviewed Research Articles

- Wikberg, Erik and Strannegård, Lars (2014) "Selling by Numbers: The Quantification and Marketization of the Swedish Art World for Contemporary Art," Organizational Aesthetics: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, 19-41.

- Werr, A. & Strannegård, L. (2013). “Developing researching managers and relevant research – the ‘executive research programme’”, Innovations in Education and Teaching International, DOI:10.1080/14703297.2013.774140.

- Näslund, L. and Pemer, F. (2012) “The appropriated language: dominant stories as a source of organizational inertia.” Human Relations 65(1): 89-110.

- Strannegård, L. & Strannegård, M. (2012). “Works of Art. Aesthetic Ambitions in Design Hotels”, Annals of Tourism Research, Volume 39, Issue 4, October 2012, Pages 1995–2012.

- Wikberg, E. & Strannegård, L. (2012). “Demarcations and Dirty Money: Financing New Private Contemporary Art Institutions in Sweden”, Homo Oeconomicus, Volume 29, Issue 3, Pages 95-118.

- Strannegård, L. & Dobers, P. (2010). “A Sustainable Identity”, Sustainable Development, No 3, April 2010.

- Dobers, P & Strannegård, L. (2009) Design for unsustainability. ReDe: Design Journal, Vol 1, No 1, pp 27-38.

- Johansson, M. and Näslund, L. (2009). "Welcome to Paradise. Customer experience design and emotional labour on a cruise ship." International Journal of Work Organization and Emotion 3(1): 40-55.

- Stenström, E (2008) ”What Turn Will Cultural Policy Take? The Renewal of the Swedish Model” in International Journal of Cultural Policy, Volume 14, Issue 1.

- Stenström, E. (2007) “Another Kind of Combine: Monogram and the Moderna Museet” in International Journal of Art History, Volume 76, Issue 1.

- Stenström, E. (2005) “I nöd och lust - om konstiga företag i en estetisk ekonomi”. Nordisk kulturpolitisk tidskrift, Nr 2.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

Published on December 17, 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Peer review, sometimes referred to as refereeing , is the process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Using strict criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decides whether to accept each submission for publication.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to the stringent process they go through before publication.

There are various types of peer review. The main difference between them is to what extent the authors, reviewers, and editors know each other’s identities. The most common types are:

- Single-blind review

- Double-blind review

- Triple-blind review

Collaborative review

Open review.

Relatedly, peer assessment is a process where your peers provide you with feedback on something you’ve written, based on a set of criteria or benchmarks from an instructor. They then give constructive feedback, compliments, or guidance to help you improve your draft.

Table of contents

What is the purpose of peer review, types of peer review, the peer review process, providing feedback to your peers, peer review example, advantages of peer review, criticisms of peer review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about peer reviews.

Many academic fields use peer review, largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the manuscript. For this reason, academic journals are among the most credible sources you can refer to.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

Peer assessment is often used in the classroom as a pedagogical tool. Both receiving feedback and providing it are thought to enhance the learning process, helping students think critically and collaboratively.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Depending on the journal, there are several types of peer review.

Single-blind peer review

The most common type of peer review is single-blind (or single anonymized) review . Here, the names of the reviewers are not known by the author.

While this gives the reviewers the ability to give feedback without the possibility of interference from the author, there has been substantial criticism of this method in the last few years. Many argue that single-blind reviewing can lead to poaching or intellectual theft or that anonymized comments cause reviewers to be too harsh.

Double-blind peer review

In double-blind (or double anonymized) review , both the author and the reviewers are anonymous.

Arguments for double-blind review highlight that this mitigates any risk of prejudice on the side of the reviewer, while protecting the nature of the process. In theory, it also leads to manuscripts being published on merit rather than on the reputation of the author.

Triple-blind peer review

While triple-blind (or triple anonymized) review —where the identities of the author, reviewers, and editors are all anonymized—does exist, it is difficult to carry out in practice.

Proponents of adopting triple-blind review for journal submissions argue that it minimizes potential conflicts of interest and biases. However, ensuring anonymity is logistically challenging, and current editing software is not always able to fully anonymize everyone involved in the process.

In collaborative review , authors and reviewers interact with each other directly throughout the process. However, the identity of the reviewer is not known to the author. This gives all parties the opportunity to resolve any inconsistencies or contradictions in real time, and provides them a rich forum for discussion. It can mitigate the need for multiple rounds of editing and minimize back-and-forth.

Collaborative review can be time- and resource-intensive for the journal, however. For these collaborations to occur, there has to be a set system in place, often a technological platform, with staff monitoring and fixing any bugs or glitches.

Lastly, in open review , all parties know each other’s identities throughout the process. Often, open review can also include feedback from a larger audience, such as an online forum, or reviewer feedback included as part of the final published product.

While many argue that greater transparency prevents plagiarism or unnecessary harshness, there is also concern about the quality of future scholarship if reviewers feel they have to censor their comments.

In general, the peer review process includes the following steps:

- First, the author submits the manuscript to the editor.

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to the author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

In an effort to be transparent, many journals are now disclosing who reviewed each article in the published product. There are also increasing opportunities for collaboration and feedback, with some journals allowing open communication between reviewers and authors.

It can seem daunting at first to conduct a peer review or peer assessment. If you’re not sure where to start, there are several best practices you can use.

Summarize the argument in your own words

Summarizing the main argument helps the author see how their argument is interpreted by readers, and gives you a jumping-off point for providing feedback. If you’re having trouble doing this, it’s a sign that the argument needs to be clearer, more concise, or worded differently.

If the author sees that you’ve interpreted their argument differently than they intended, they have an opportunity to address any misunderstandings when they get the manuscript back.

Separate your feedback into major and minor issues

It can be challenging to keep feedback organized. One strategy is to start out with any major issues and then flow into the more minor points. It’s often helpful to keep your feedback in a numbered list, so the author has concrete points to refer back to.

Major issues typically consist of any problems with the style, flow, or key points of the manuscript. Minor issues include spelling errors, citation errors, or other smaller, easy-to-apply feedback.

Tip: Try not to focus too much on the minor issues. If the manuscript has a lot of typos, consider making a note that the author should address spelling and grammar issues, rather than going through and fixing each one.

The best feedback you can provide is anything that helps them strengthen their argument or resolve major stylistic issues.

Give the type of feedback that you would like to receive

No one likes being criticized, and it can be difficult to give honest feedback without sounding overly harsh or critical. One strategy you can use here is the “compliment sandwich,” where you “sandwich” your constructive criticism between two compliments.

Be sure you are giving concrete, actionable feedback that will help the author submit a successful final draft. While you shouldn’t tell them exactly what they should do, your feedback should help them resolve any issues they may have overlooked.

As a rule of thumb, your feedback should be:

- Easy to understand

- Constructive

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Below is a brief annotated research example. You can view examples of peer feedback by hovering over the highlighted sections.

Influence of phone use on sleep

Studies show that teens from the US are getting less sleep than they were a decade ago (Johnson, 2019) . On average, teens only slept for 6 hours a night in 2021, compared to 8 hours a night in 2011. Johnson mentions several potential causes, such as increased anxiety, changed diets, and increased phone use.

The current study focuses on the effect phone use before bedtime has on the number of hours of sleep teens are getting.

For this study, a sample of 300 teens was recruited using social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. The first week, all teens were allowed to use their phone the way they normally would, in order to obtain a baseline.

The sample was then divided into 3 groups:

- Group 1 was not allowed to use their phone before bedtime.

- Group 2 used their phone for 1 hour before bedtime.

- Group 3 used their phone for 3 hours before bedtime.

All participants were asked to go to sleep around 10 p.m. to control for variation in bedtime . In the morning, their Fitbit showed the number of hours they’d slept. They kept track of these numbers themselves for 1 week.

Two independent t tests were used in order to compare Group 1 and Group 2, and Group 1 and Group 3. The first t test showed no significant difference ( p > .05) between the number of hours for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 2 ( M = 7.0, SD = 0.8). The second t test showed a significant difference ( p < .01) between the average difference for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 3 ( M = 6.1, SD = 1.5).

This shows that teens sleep fewer hours a night if they use their phone for over an hour before bedtime, compared to teens who use their phone for 0 to 1 hours.

Peer review is an established and hallowed process in academia, dating back hundreds of years. It provides various fields of study with metrics, expectations, and guidance to ensure published work is consistent with predetermined standards.

- Protects the quality of published research

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. Any content that raises red flags for reviewers can be closely examined in the review stage, preventing plagiarized or duplicated research from being published.

- Gives you access to feedback from experts in your field

Peer review represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field and to improve your writing through their feedback and guidance. Experts with knowledge about your subject matter can give you feedback on both style and content, and they may also suggest avenues for further research that you hadn’t yet considered.

- Helps you identify any weaknesses in your argument

Peer review acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process. This way, you’ll end up with a more robust, more cohesive article.

While peer review is a widely accepted metric for credibility, it’s not without its drawbacks.

- Reviewer bias

The more transparent double-blind system is not yet very common, which can lead to bias in reviewing. A common criticism is that an excellent paper by a new researcher may be declined, while an objectively lower-quality submission by an established researcher would be accepted.

- Delays in publication

The thoroughness of the peer review process can lead to significant delays in publishing time. Research that was current at the time of submission may not be as current by the time it’s published. There is also high risk of publication bias , where journals are more likely to publish studies with positive findings than studies with negative findings.

- Risk of human error

By its very nature, peer review carries a risk of human error. In particular, falsification often cannot be detected, given that reviewers would have to replicate entire experiments to ensure the validity of results.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Discourse analysis

- Cohort study

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilizing rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication. For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project– provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well-regarded.

In general, the peer review process follows the following steps:

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits, and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. It also represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field. It acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to this stringent process they go through before publication.

Many academic fields use peer review , largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the published manuscript.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/peer-review/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, ethical considerations in research | types & examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- SpringerLink shop

Peer Review

The majority of manuscripts that journal editors receive are unsolicited. Some journals, however, only accept papers that they have invited. Some manuscripts will be of extremely high quality, but others papers will be borderline in terms of the scope of the journal and quality of work. With any paper submitted you will have to decide whether this is what the readers want or need and this is where peer reviewers come in.

The quality of peer reviewers is extremely important to the quality of a journal. Peer review helps to uphold the academic credibility of a journal—peer reviewers are almost like intellectual gatekeepers to the journal as they provide an objective assessment of a paper and determine if it is useful enough to be published.

The importance of peer review

Peer reviewers do several things:

- They safeguard the relevance of the work to the journal

- They advise about important earlier work that may need to be taken into account

- They check methods, statistics, sometimes correct English and verify whether the conclusions are supported by the research.

However, the final decision as to whether an article is accepted or rejected is always down to the editor.

For more introductory information on peer review, see the peer reviewer academy here .

How to find reviewers

Similar to being a member of a journal’s editorial board, being a reviewer is considered to be a prestigious position and can therefore attract unsolicited requests. Ideally, you should source your own and have a pool of referees in a database with details of their specialist areas as well as some notes (e.g. number of times they have peer reviewed articles, quality and timekeeping).

Sourcing referees is one of the most difficult tasks as an editor. Sometimes you can use editorial board members, but they might not be the most suitable and there is arguably a perceived conflict of interest in having them review for the journal they are on the editorial board for.

To find potential peer reviewers you can check the reference list of the manuscript, which is always a good starting point. You can also run searches in SpringerLink to identify who is publishing regularly and recently in that field. On Web of Science, you can rank authors by number of publications in a particular subject, so you can determine who the most prominent researchers are.

It is also equally important to try and obtain a global perspective on a paper, so when narrowing down your list of potential peer reviewers try not to have them all from the same country; the same principle that applies to forming an editorial board . This is particularly important for medical journals as burden of disease and treatment patterns vary from country to country so it often adds value having an article reviewed by international peers.

Once you have found potential referees, it is important to check for any potential conflicts of interest, which include having published with the author recently, working with the author, or being sponsored by a pharmaceutical company that is developing a competitor drug. For rare and new areas this can sometimes be problematic because it may just be one research group who is working on that particular area. However, you can try and delegate to the editorial board for suggestions if there is any potential difficulty; double-blind refereeing, where an author’s identity and that of the referee is concealed, can work well in these circumstances to avoid any potential bias. Some journals ask authors to provide a list of potential peer reviewers; however they must not be from the same institution/research group as the author and they must not have published together—this must be made clear in the instructions to authors information . Again when considering potential referees that have been suggested by an author you should always run a check on PubMed or SpringerLink to attempt to eliminate any potential conflicts of interest.

Finally, once you have the names of your potential reviewers you need to find their contact details. Most of the time, if they have published recently, their latest article might have an email address or contact telephone number in the correspondence section. However, most of the time you will need to be quite proactive at using internet searches to obtain up-to-date contact details.

How to target and invite reviewers

It is common to use 2–3 peer reviewers per manuscript. Because it is always possible that some people may not be available or able to review, it is wise to target more than is required on each occasion (e.g. have five reviewers in mind and recruit three, then if one says no you have another two potentials). It is not unheard of for editors to have to invite seven or more reviewers in order to obtain two peer reviews, especially around holiday seasons. On the other hand, editors must also be mindful that local/regional holidays should not be used as a reason to keep authors waiting. For a potential author, every day is important. It is professional practice to notify authors and reviewers in advance of upcoming holidays/office closures etc., providing them with alternative means of contact during this time wherever practically possible.

Always use reviewers appropriate to the field, perhaps doing similar research; they are more likely to find the paper relevant and interesting, and to be qualified to provide feedback on its strengths and weaknesses. You should avoid asking reviewers who are reviewing other articles for the journal and/or currently writing an article; or those that have reviewed within the last month—the more they are overloaded the less likely they will be to say yes.

When approaching referees it is good practice to invite them prior to sending the full manuscript. The communication should contain the following elements:

- Title of paper and journal

- Abstract (if applicable)

- Manuscript number

- That their opinion would be very helpful

- Are they able to referee the manuscript within the timeframe

- Is it in their area of expertise

- Do they have any conflicts of interest?

- If they can’t review then can they recommend someone else?

- Deadline for response.

If they accept, then you should send the paper with clear instructions and a referee report form.

How to develop a useful reviewer database

Ideally you should aim to have a pool of referees in a database with details of their specialist areas and up-to-date contact details, as well as some notes on quality (i.e. number of times they have peer reviewed, how reliable they are, whether they peer review within the timescale, quality of their previous review(s)).

Some reviewers will write several pages of notes and even annotate and mark up manuscripts, others will produce one line reports that don’t help the editors make a decision. It is important to have this information available when selecting appropriate reviewers.

What programs and software are available

For smaller journals with relatively few submissions, a simple system (i.e. a spreadsheet) may be adequate, but for larger journals, electronic manuscript tracking systems can help to keep track of submissions and help to develop a reviewer database. Editorial Manager , is a web-based manuscript submission and review system that lets authors submit articles directly online. Editorial Manager makes it possible for authors to submit manuscripts via the Internet, provides online peer review services and tracks manuscripts through the entire review process. It also allows editors to communicate directly with authors and reviewers. Key features include automatic conversion of authors’ submissions into PDF format as well as supporting submissions in various file formats and special characters.

Clear instructions for reviewers

After a reviewer accepts your invitation to review a manuscript, the reply should include the article or a link to Editorial Manager and a template report form. They should be encouraged to make constructive comments and the template report form should have the following components:

- Deadline by which the review is wanted by (with the option of them proposing an alternative within a reasonable timeframe)

- Whether you want the review sent by email or uploaded to Editorial Manager

- Instructions on evaluation of quality

- Is it original work

- Is it well researched? Are the methods appropriate? Are the conclusions a fair representation of the results?

- Is all relevant previous research referenced?

- Recommendations

- Accept without changes (rare)

- Accept if revised, but doesn’t need re-review

- Revisions that need re-review by reviewer

If a submitted paper’s English is considered to not be up to the standards to be sent to a busy reviewer, then it is the editor’s responsibility to communicate this to the author and suggest that the article undergoes copyediting prior to resubmission.

Setting deadlines and sending reminders

The invitation correspondence needs to clearly state the deadline by which the review should be returned by. Two to three weeks is fairly standard and, given the difficulty in sometimes finding good reviewers, they should always be given the option of negotiating an alternative return by date. Reviewers can be busy people and gentle reminders are often required to chase them up for reviews. You may wish to develop template chaser emails containing the following elements:

- Title for paper

- That they had agreed to send a review on (manuscript number and title) by (date)

- Date they had agreed

- Date it was due by

- That their opinion is important

- Are they still able to review the manuscript

- Method by which it should be sent (email, electronic submission)

- Deadline response with a reminder that if you hear nothing you will have to approach alternative reviewers.

If you still get no reply, then consider approaching alternative reviewers from your list of back up reviewers.

Decision types: What they mean and communicating them to authors

Reviewer decisions are really just recommendations and they tend to fall into the following categories:

- Accept without any revisions

- Accept but on the condition that minor revisions will be done by the author (paper doesn’t need re-review)

- Revisions required that need re-review by reviewer

The decision should not be based on a poll of how many accepts and rejects and maybes the peer-reviewers gave. As an editor, you must verify what the reviewers have suggested and make the final decision. Sometimes reviewer comments may be very superficial and occasionally inappropriate. If there are situations where there are clear differences in opinions between reviewers then options include inviting another reviewer to make a final decision, or approaching an editorial board member.

Before sending the reviewer comments to an author it is good practice to edit and/or select the most constructive and relevant comments to make it clear to the author what the decision is and what might need to be done if their article needs revising.

Decisions tend to either be that the author needs to revise the manuscript or that the manuscript is rejected. Template emails are again useful here.

Request for revision should include statements as follows:

- Your paper has now been peer reviewed and attached (or below) please find the reviewer comments

- Please consider the comments and prepare a revised version of the manuscript plus a separate file with a point-by-point response to show how the comments have been addressed

- Deadline revisions are required by.

Rejection letters are hard to write, especially in situations when an author has revised the manuscript, sometimes several times, and it is always important to show respect for the time the author has spent writing and/or revising the manuscript. The elements of a rejection letter should include:

"Your paper has now been peer reviewed and the manuscript was considered to be unsuitable for publication in (journal name) for several reasons, such as:"

- The paper requires further experimentation to be complete

- The paper is a duplication of what others have already published and adds nothing substantial to what is already known

- The results don’t support the conclusions

- References are too old.

It is important that the rejection letter contains honest and constructive feedback. Equally, it is important that authors are not given false hope that if they make some revisions to the article then they can resubmit it to your journal if this is definitely not the case.

In cases of rejection due to plagiarism, the rejection letter should follow a different format and you should refer to COPE for flowcharts and template letters.

Working with reviewers

Similar to editorial board members, the role of a reviewer is a voluntary position and it is more about the prestige and honor of being a reviewer rather than other benefits.

Reviewers can be very busy people and so it is important to not overload them with work. If you know that the same person is also writing an article for the journal or reviewing another article, or has very recently reviewed an article within the last month, it would be sensible to avoid asking them again too soon—the more they are overloaded the less likely they will be to say yes. But, much of this depends on your working relationship with them.

In terms of setting deadlines for reviews, this depends on your internal deadlines; a month may be adequate or too long. It is important to be flexible and plan well in advance, especially for holiday periods, the end of the year is usually a difficult time to recruit reviewers and you always need to have at least one or two back-up reviewers on standby to contact if you have any problems in recruiting and/or hearing back from reviewers when you are working to a tight deadline.

If you have no response from a reviewer, despite one or two chaser emails, you should go ahead and invite an alternative reviewer and let the person who was originally invited know that they are no longer required on this occasion. There are many reasons why a reviewer may not respond to your emails and it is important to be polite and sensitive in your correspondence. The email should state that you understand that they are busy; however, due to time restrictions in meeting publication deadlines, on this occasion another reviewer has been recruited.

Sometimes reviewer comments can be quite scathing, or the quality of the review might be very superficial. Occasionally reviewers might be in direct competition with the author, want more of their own publications cited or have another agenda. Furthermore, peer reviewers might feel restricted and intimidated in what they say about a manuscript as they are worried about the potential repercussions of making negative comments.

Different refereeing systems have been developed, such as double-blind refereeing, where the author and the referee identities are masked as far as possible, which contrasts with open refereeing where the referee and the author know each others identity.

Conflicts of interest can exist with reviewers and you should aim to screen much of this out before you invite a reviewer. Reviewers must therefore also be asked to state explicitly whether conflicts do or do not exist. Reviewers must not use knowledge of the work, before its publication, to further their own interests.

It is always polite to thank reviewers when they have spent the time reviewing an article. A personal email is often best and reviewers tend to be interested in what the overall decision was.

Peer review templates, expert examples and free training courses

Joanna Wilkinson

Learning how to write a constructive peer review is an essential step in helping to safeguard the quality and integrity of published literature. Read on for resources that will get you on the right track, including peer review templates, example reports and the Web of Science™ Academy: our free, online course that teaches you the core competencies of peer review through practical experience ( try it today ).

How to write a peer review

Understanding the principles, forms and functions of peer review will enable you to write solid, actionable review reports. It will form the basis for a comprehensive and well-structured review, and help you comment on the quality, rigor and significance of the research paper. It will also help you identify potential breaches of normal ethical practice.

This may sound daunting but it doesn’t need to be. There are plenty of peer review templates, resources and experts out there to help you, including:

Peer review training courses and in-person workshops

- Peer review templates ( found in our Web of Science Academy )

- Expert examples of peer review reports

- Co-reviewing (sharing the task of peer reviewing with a senior researcher)

Other peer review resources, blogs, and guidelines

We’ll go through each one of these in turn below, but first: a quick word on why learning peer review is so important.

Why learn to peer review?

Peer reviewers and editors are gatekeepers of the research literature used to document and communicate human discovery. Reviewers, therefore, need a sound understanding of their role and obligations to ensure the integrity of this process. This also helps them maintain quality research, and to help protect the public from flawed and misleading research findings.

Learning to peer review is also an important step in improving your own professional development.

You’ll become a better writer and a more successful published author in learning to review. It gives you a critical vantage point and you’ll begin to understand what editors are looking for. It will also help you keep abreast of new research and best-practice methods in your field.

We strongly encourage you to learn the core concepts of peer review by joining a course or workshop. You can attend in-person workshops to learn from and network with experienced reviewers and editors. As an example, Sense about Science offers peer review workshops every year. To learn more about what might be in store at one of these, researcher Laura Chatland shares her experience at one of the workshops in London.

There are also plenty of free, online courses available, including courses in the Web of Science Academy such as ‘Reviewing in the Sciences’, ‘Reviewing in the Humanities’ and ‘An introduction to peer review’

The Web of Science Academy also supports co-reviewing with a mentor to teach peer review through practical experience. You learn by writing reviews of preprints, published papers, or even ‘real’ unpublished manuscripts with guidance from your mentor. You can work with one of our community mentors or your own PhD supervisor or postdoc advisor, or even a senior colleague in your department.

Go to the Web of Science Academy

Peer review templates

Peer review templates are helpful to use as you work your way through a manuscript. As part of our free Web of Science Academy courses, you’ll gain exclusive access to comprehensive guidelines and a peer review report. It offers points to consider for all aspects of the manuscript, including the abstract, methods and results sections. It also teaches you how to structure your review and will get you thinking about the overall strengths and impact of the paper at hand.

- Web of Science Academy template (requires joining one of the free courses)

- PLoS’s review template

- Wiley’s peer review guide (not a template as such, but a thorough guide with questions to consider in the first and second reading of the manuscript)

Beyond following a template, it’s worth asking your editor or checking the journal’s peer review management system. That way, you’ll learn whether you need to follow a formal or specific peer review structure for that particular journal. If no such formal approach exists, try asking the editor for examples of other reviews performed for the journal. This will give you a solid understanding of what they expect from you.

Peer review examples

Understand what a constructive peer review looks like by learning from the experts.

Here’s a sample of pre and post-publication peer reviews displayed on Web of Science publication records to help guide you through your first few reviews. Some of these are transparent peer reviews , which means the entire process is open and visible — from initial review and response through to revision and final publication decision. You may wish to scroll to the bottom of these pages so you can first read the initial reviews, and make your way up the page to read the editor and author’s responses.

- Pre-publication peer review: Patterns and mechanisms in instances of endosymbiont-induced parthenogenesis

- Pre-publication peer review: Can Ciprofloxacin be Used for Precision Treatment of Gonorrhea in Public STD Clinics? Assessment of Ciprofloxacin Susceptibility and an Opportunity for Point-of-Care Testing

- Transparent peer review: Towards a standard model of musical improvisation

- Transparent peer review: Complex mosaic of sexual dichromatism and monochromatism in Pacific robins results from both gains and losses of elaborate coloration

- Post-publication peer review: Brain state monitoring for the future prediction of migraine attacks

- Web of Science Academy peer review: Students’ Perception on Training in Writing Research Article for Publication

F1000 has also put together a nice list of expert reviewer comments pertaining to the various aspects of a review report.

Co-reviewing

Co-reviewing (sharing peer review assignments with senior researchers) is one of the best ways to learn peer review. It gives researchers a hands-on, practical understanding of the process.

In an article in The Scientist , the team at Future of Research argues that co-reviewing can be a valuable learning experience for peer review, as long as it’s done properly and with transparency. The reason there’s a need to call out how co-reviewing works is because it does have its downsides. The practice can leave early-career researchers unaware of the core concepts of peer review. This can make it hard to later join an editor’s reviewer pool if they haven’t received adequate recognition for their share of the review work. (If you are asked to write a peer review on behalf of a senior colleague or researcher, get recognition for your efforts by asking your senior colleague to verify the collaborative co-review on your Web of Science researcher profiles).

The Web of Science Academy course ‘Co-reviewing with a mentor’ is uniquely practical in this sense. You will gain experience in peer review by practicing on real papers and working with a mentor to get feedback on how their peer review can be improved. Students submit their peer review report as their course assignment and after internal evaluation receive a course certificate, an Academy graduate badge on their Web of Science researcher profile and is put in front of top editors in their field through the Reviewer Locator at Clarivate.

Here are some external peer review resources found around the web:

- Peer Review Resources from Sense about Science

- Peer Review: The Nuts and Bolts by Sense about Science

- How to review journal manuscripts by R. M. Rosenfeld for Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery

- Ethical guidelines for peer review from COPE

- An Instructional Guide for Peer Reviewers of Biomedical Manuscripts by Callaham, Schriger & Cooper for Annals of Emergency Medicine (requires Flash or Adobe)

- EQUATOR Network’s reporting guidelines for health researchers

And finally, we’ve written a number of blogs about handy peer review tips. Check out some of our top picks:

- How to Write a Peer Review: 12 things you need to know

- Want To Peer Review? Top 10 Tips To Get Noticed By Editors

- Review a manuscript like a pro: 6 tips from a Web of Science Academy supervisor

- How to write a structured reviewer report: 5 tips from an early-career researcher

Want to learn more? Become a master of peer review and connect with top journal editors. The Web of Science Academy – your free online hub of courses designed by expert reviewers, editors and Nobel Prize winners. Find out more today.

Related posts

Unlocking u.k. research excellence: key insights from the research professional news live summit.

For better insights, assess research performance at the department level

Search by keyword

Peer review report on sweden now online - products eurostat news.

Back Peer review report on Sweden now online

10 May 2022

Eurostat is pleased to announce that the fourth peer review report within the third round of European Statistical System (ESS) peer reviews – the peer review report on Sweden – is now publicly available on Eurostat’s dedicated web page .

The report has been published following the peer review visit in Sweden, which took place physically between 29 November- 3 December 2021 at the offices of Statistics Sweden , and was implemented by a dedicated team of four experts, including one from Eurostat.

The peer reviews of national statistical systems are conducted by external experts (from both inside and outside the ESS) and follow the same methodology. This includes the completion of self-assessment questionnaires by several statistical authorities followed by a peer review visit. The results are a peer review report containing expert recommendations for improvement, and an action plan to address these recommendations developed by the national statistical institute of the reviewed country.

The current third round of ESS peer reviews will be carried out until the beginning of September 2023. Eight ESS peer reviews took place from end of June to December 2021: four of them virtually and four physically. Five of the 12 peer reviews foreseen in 2022 have already taken place (Luxembourg, Ireland, Denmark, Bulgaria, Austria), all in physical or hybrid mode, and the remaining 11 are scheduled for 2023.

For each of the 31 ESS members, the final reports and the accompanying improvement action plans will be published in due time on Eurostat’s website .

For more information:

- Dedicated section on peer reviews

To contact us, please visit our User Support page.

For press queries, please contact our Media Support .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.25(3); 2014 Oct

Peer Review in Scientific Publications: Benefits, Critiques, & A Survival Guide

Jacalyn kelly.

1 Clinical Biochemistry, Department of Pediatric Laboratory Medicine, The Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Tara Sadeghieh

Khosrow adeli.

2 Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

3 Chair, Communications and Publications Division (CPD), International Federation for Sick Clinical Chemistry (IFCC), Milan, Italy

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding publication of this article.

Peer review has been defined as a process of subjecting an author’s scholarly work, research or ideas to the scrutiny of others who are experts in the same field. It functions to encourage authors to meet the accepted high standards of their discipline and to control the dissemination of research data to ensure that unwarranted claims, unacceptable interpretations or personal views are not published without prior expert review. Despite its wide-spread use by most journals, the peer review process has also been widely criticised due to the slowness of the process to publish new findings and due to perceived bias by the editors and/or reviewers. Within the scientific community, peer review has become an essential component of the academic writing process. It helps ensure that papers published in scientific journals answer meaningful research questions and draw accurate conclusions based on professionally executed experimentation. Submission of low quality manuscripts has become increasingly prevalent, and peer review acts as a filter to prevent this work from reaching the scientific community. The major advantage of a peer review process is that peer-reviewed articles provide a trusted form of scientific communication. Since scientific knowledge is cumulative and builds on itself, this trust is particularly important. Despite the positive impacts of peer review, critics argue that the peer review process stifles innovation in experimentation, and acts as a poor screen against plagiarism. Despite its downfalls, there has not yet been a foolproof system developed to take the place of peer review, however, researchers have been looking into electronic means of improving the peer review process. Unfortunately, the recent explosion in online only/electronic journals has led to mass publication of a large number of scientific articles with little or no peer review. This poses significant risk to advances in scientific knowledge and its future potential. The current article summarizes the peer review process, highlights the pros and cons associated with different types of peer review, and describes new methods for improving peer review.

WHAT IS PEER REVIEW AND WHAT IS ITS PURPOSE?

Peer Review is defined as “a process of subjecting an author’s scholarly work, research or ideas to the scrutiny of others who are experts in the same field” ( 1 ). Peer review is intended to serve two primary purposes. Firstly, it acts as a filter to ensure that only high quality research is published, especially in reputable journals, by determining the validity, significance and originality of the study. Secondly, peer review is intended to improve the quality of manuscripts that are deemed suitable for publication. Peer reviewers provide suggestions to authors on how to improve the quality of their manuscripts, and also identify any errors that need correcting before publication.

HISTORY OF PEER REVIEW

The concept of peer review was developed long before the scholarly journal. In fact, the peer review process is thought to have been used as a method of evaluating written work since ancient Greece ( 2 ). The peer review process was first described by a physician named Ishaq bin Ali al-Rahwi of Syria, who lived from 854-931 CE, in his book Ethics of the Physician ( 2 ). There, he stated that physicians must take notes describing the state of their patients’ medical conditions upon each visit. Following treatment, the notes were scrutinized by a local medical council to determine whether the physician had met the required standards of medical care. If the medical council deemed that the appropriate standards were not met, the physician in question could receive a lawsuit from the maltreated patient ( 2 ).

The invention of the printing press in 1453 allowed written documents to be distributed to the general public ( 3 ). At this time, it became more important to regulate the quality of the written material that became publicly available, and editing by peers increased in prevalence. In 1620, Francis Bacon wrote the work Novum Organum, where he described what eventually became known as the first universal method for generating and assessing new science ( 3 ). His work was instrumental in shaping the Scientific Method ( 3 ). In 1665, the French Journal des sçavans and the English Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society were the first scientific journals to systematically publish research results ( 4 ). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society is thought to be the first journal to formalize the peer review process in 1665 ( 5 ), however, it is important to note that peer review was initially introduced to help editors decide which manuscripts to publish in their journals, and at that time it did not serve to ensure the validity of the research ( 6 ). It did not take long for the peer review process to evolve, and shortly thereafter papers were distributed to reviewers with the intent of authenticating the integrity of the research study before publication. The Royal Society of Edinburgh adhered to the following peer review process, published in their Medical Essays and Observations in 1731: “Memoirs sent by correspondence are distributed according to the subject matter to those members who are most versed in these matters. The report of their identity is not known to the author.” ( 7 ). The Royal Society of London adopted this review procedure in 1752 and developed the “Committee on Papers” to review manuscripts before they were published in Philosophical Transactions ( 6 ).

Peer review in the systematized and institutionalized form has developed immensely since the Second World War, at least partly due to the large increase in scientific research during this period ( 7 ). It is now used not only to ensure that a scientific manuscript is experimentally and ethically sound, but also to determine which papers sufficiently meet the journal’s standards of quality and originality before publication. Peer review is now standard practice by most credible scientific journals, and is an essential part of determining the credibility and quality of work submitted.

IMPACT OF THE PEER REVIEW PROCESS

Peer review has become the foundation of the scholarly publication system because it effectively subjects an author’s work to the scrutiny of other experts in the field. Thus, it encourages authors to strive to produce high quality research that will advance the field. Peer review also supports and maintains integrity and authenticity in the advancement of science. A scientific hypothesis or statement is generally not accepted by the academic community unless it has been published in a peer-reviewed journal ( 8 ). The Institute for Scientific Information ( ISI ) only considers journals that are peer-reviewed as candidates to receive Impact Factors. Peer review is a well-established process which has been a formal part of scientific communication for over 300 years.

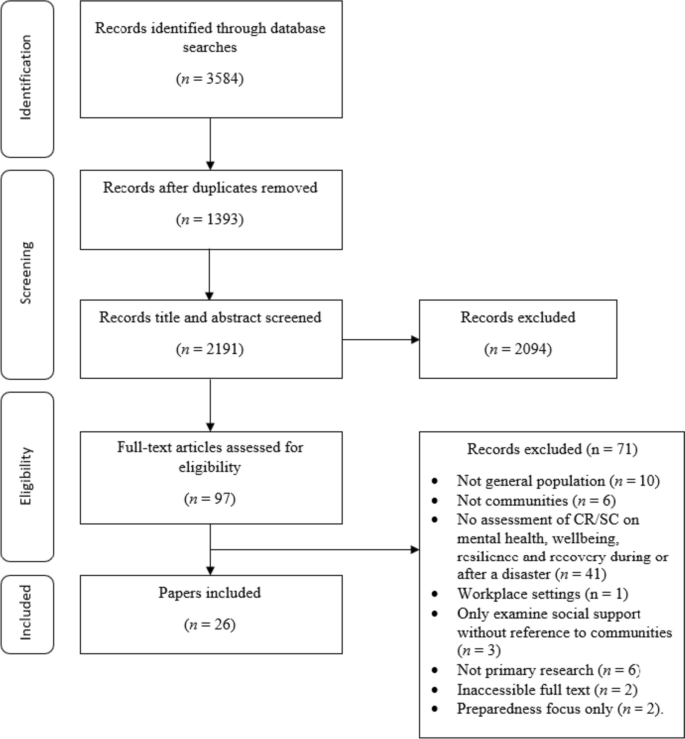

OVERVIEW OF THE PEER REVIEW PROCESS

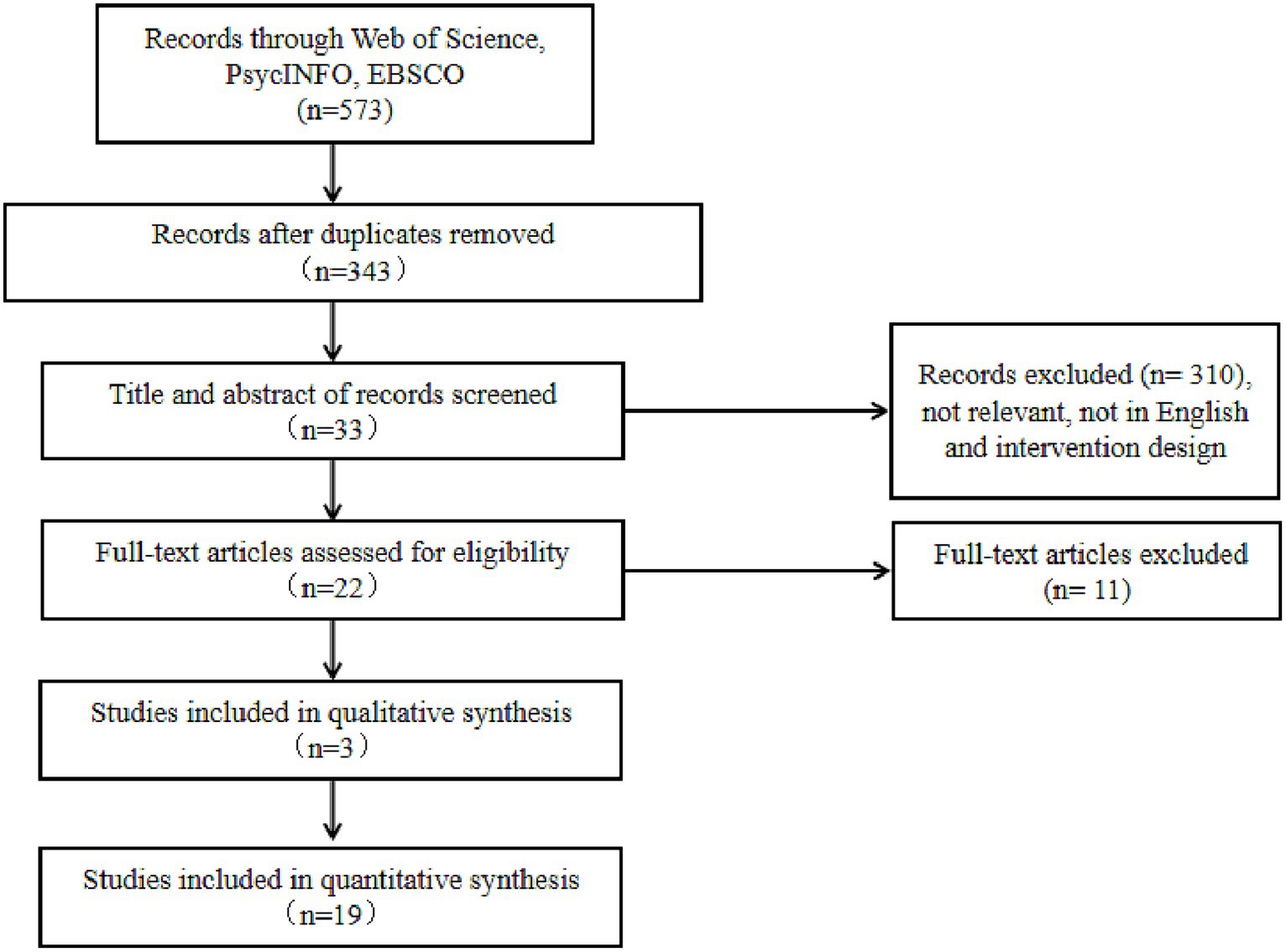

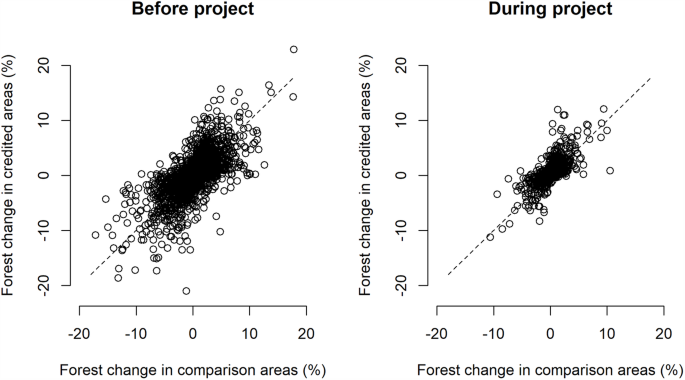

The peer review process begins when a scientist completes a research study and writes a manuscript that describes the purpose, experimental design, results, and conclusions of the study. The scientist then submits this paper to a suitable journal that specializes in a relevant research field, a step referred to as pre-submission. The editors of the journal will review the paper to ensure that the subject matter is in line with that of the journal, and that it fits with the editorial platform. Very few papers pass this initial evaluation. If the journal editors feel the paper sufficiently meets these requirements and is written by a credible source, they will send the paper to accomplished researchers in the field for a formal peer review. Peer reviewers are also known as referees (this process is summarized in Figure 1 ). The role of the editor is to select the most appropriate manuscripts for the journal, and to implement and monitor the peer review process. Editors must ensure that peer reviews are conducted fairly, and in an effective and timely manner. They must also ensure that there are no conflicts of interest involved in the peer review process.

Overview of the review process

When a reviewer is provided with a paper, he or she reads it carefully and scrutinizes it to evaluate the validity of the science, the quality of the experimental design, and the appropriateness of the methods used. The reviewer also assesses the significance of the research, and judges whether the work will contribute to advancement in the field by evaluating the importance of the findings, and determining the originality of the research. Additionally, reviewers identify any scientific errors and references that are missing or incorrect. Peer reviewers give recommendations to the editor regarding whether the paper should be accepted, rejected, or improved before publication in the journal. The editor will mediate author-referee discussion in order to clarify the priority of certain referee requests, suggest areas that can be strengthened, and overrule reviewer recommendations that are beyond the study’s scope ( 9 ). If the paper is accepted, as per suggestion by the peer reviewer, the paper goes into the production stage, where it is tweaked and formatted by the editors, and finally published in the scientific journal. An overview of the review process is presented in Figure 1 .

WHO CONDUCTS REVIEWS?