What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

1. Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

2. Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

Find academic papers related to your research topic faster. Try Research on Paperpal

3. Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

4. Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

5. Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

6. Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

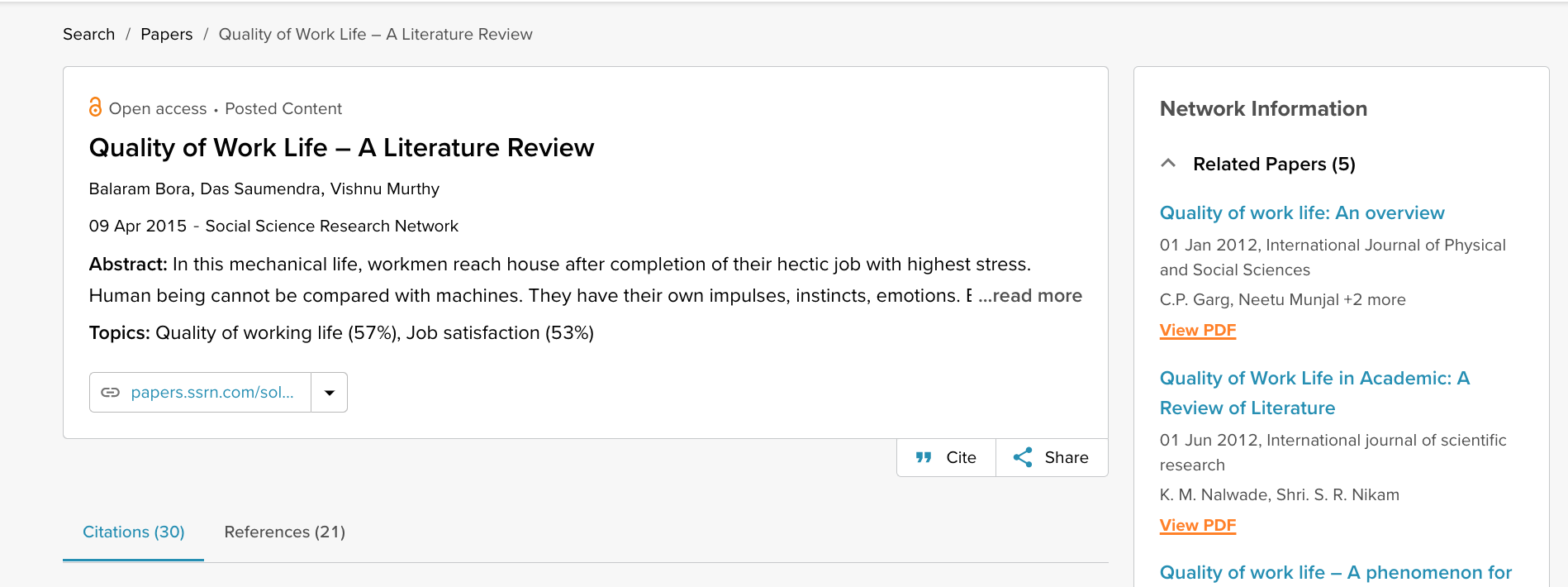

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

Strengthen your literature review with factual insights. Try Research on Paperpal for free!

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Write and Cite as you go with Paperpal Research. Start now for free.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

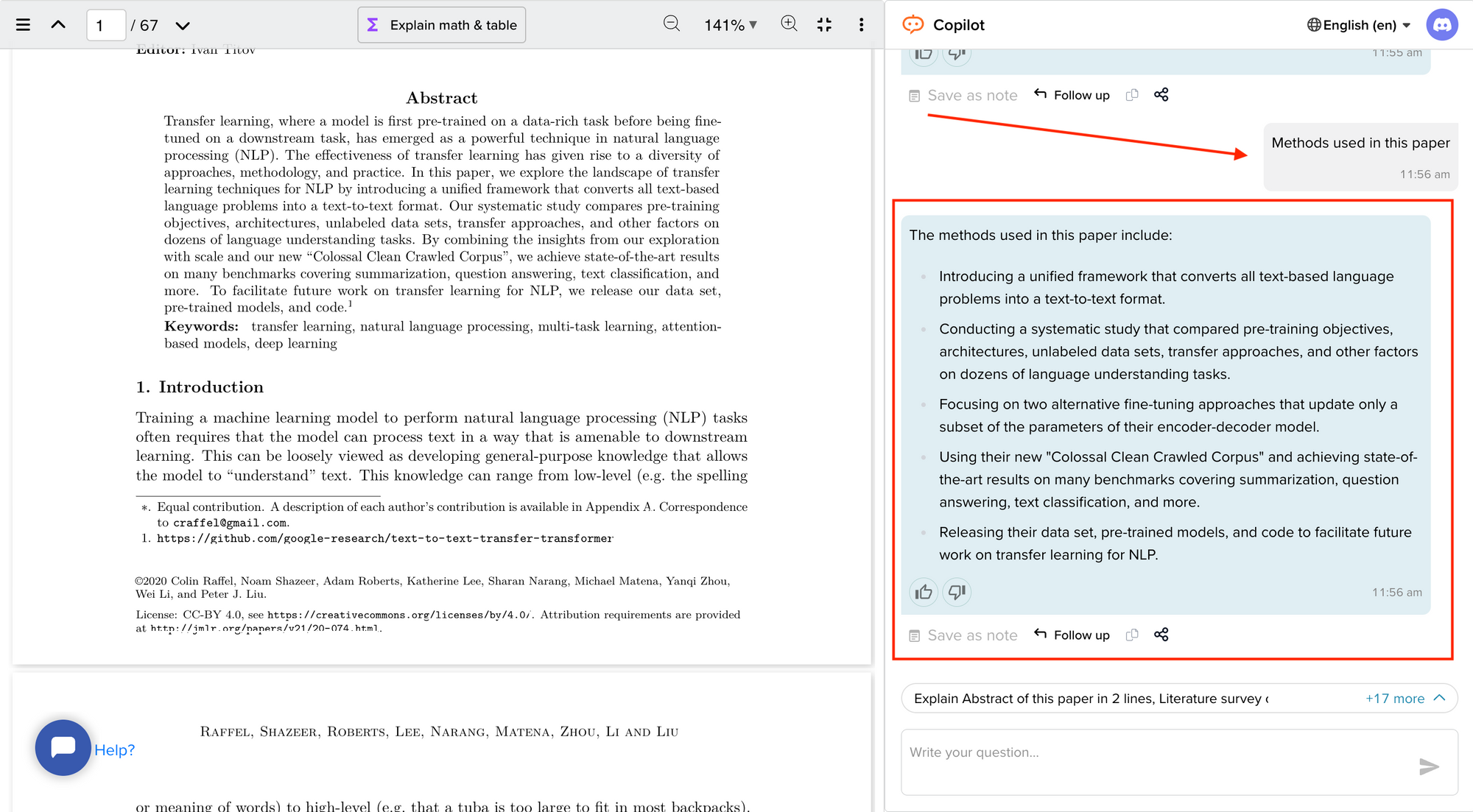

Whether you’re exploring a new research field or finding new angles to develop an existing topic, sifting through hundreds of papers can take more time than you have to spare. But what if you could find science-backed insights with verified citations in seconds? That’s the power of Paperpal’s new Research feature!

How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Paperpal, an AI writing assistant, integrates powerful academic search capabilities within its writing platform. With the Research feature, you get 100% factual insights, with citations backed by 250M+ verified research articles, directly within your writing interface with the option to save relevant references in your Citation Library. By eliminating the need to switch tabs to find answers to all your research questions, Paperpal saves time and helps you stay focused on your writing.

Here’s how to use the Research feature:

- Ask a question: Get started with a new document on paperpal.com. Click on the “Research” feature and type your question in plain English. Paperpal will scour over 250 million research articles, including conference papers and preprints, to provide you with accurate insights and citations.

- Review and Save: Paperpal summarizes the information, while citing sources and listing relevant reads. You can quickly scan the results to identify relevant references and save these directly to your built-in citations library for later access.

- Cite with Confidence: Paperpal makes it easy to incorporate relevant citations and references into your writing, ensuring your arguments are well-supported by credible sources. This translates to a polished, well-researched literature review.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a good literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses. By combining effortless research with an easy citation process, Paperpal Research streamlines the literature review process and empowers you to write faster and with more confidence. Try Paperpal Research now and see for yourself.

Frequently asked questions

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.

Literature reviews are essential components of academic and research papers, and various strategies can be employed to conduct them effectively. If you want to know how to write a literature review for a research paper, here are four common approaches that are often used by researchers. Chronological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the chronological order of publication. It helps to trace the development of a topic over time, showing how ideas, theories, and research have evolved. Thematic Review: Thematic reviews focus on identifying and analyzing themes or topics that cut across different studies. Instead of organizing the literature chronologically, it is grouped by key themes or concepts, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of various aspects of the topic. Methodological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the research methods employed in different studies. It helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies and allows the reader to evaluate the reliability and validity of the research findings. Theoretical Review: A theoretical review examines the literature based on the theoretical frameworks used in different studies. This approach helps to identify the key theories that have been applied to the topic and assess their contributions to the understanding of the subject. It’s important to note that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, and a literature review may combine elements of more than one approach. The choice of strategy depends on the research question, the nature of the literature available, and the goals of the review. Additionally, other strategies, such as integrative reviews or systematic reviews, may be employed depending on the specific requirements of the research.

The literature review format can vary depending on the specific publication guidelines. However, there are some common elements and structures that are often followed. Here is a general guideline for the format of a literature review: Introduction: Provide an overview of the topic. Define the scope and purpose of the literature review. State the research question or objective. Body: Organize the literature by themes, concepts, or chronology. Critically analyze and evaluate each source. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the studies. Highlight any methodological limitations or biases. Identify patterns, connections, or contradictions in the existing research. Conclusion: Summarize the key points discussed in the literature review. Highlight the research gap. Address the research question or objective stated in the introduction. Highlight the contributions of the review and suggest directions for future research.

Both annotated bibliographies and literature reviews involve the examination of scholarly sources. While annotated bibliographies focus on individual sources with brief annotations, literature reviews provide a more in-depth, integrated, and comprehensive analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. The key differences are as follows:

| Annotated Bibliography | Literature Review | |

| Purpose | List of citations of books, articles, and other sources with a brief description (annotation) of each source. | Comprehensive and critical analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. |

| Focus | Summary and evaluation of each source, including its relevance, methodology, and key findings. | Provides an overview of the current state of knowledge on a particular subject and identifies gaps, trends, and patterns in existing literature. |

| Structure | Each citation is followed by a concise paragraph (annotation) that describes the source’s content, methodology, and its contribution to the topic. | The literature review is organized thematically or chronologically and involves a synthesis of the findings from different sources to build a narrative or argument. |

| Length | Typically 100-200 words | Length of literature review ranges from a few pages to several chapters |

| Independence | Each source is treated separately, with less emphasis on synthesizing the information across sources. | The writer synthesizes information from multiple sources to present a cohesive overview of the topic. |

References

- Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review. Journal of criminal justice education , 24 (2), 218-234.

- Pan, M. L. (2016). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Taylor & Francis.

- Cantero, C. (2019). How to write a literature review. San José State University Writing Center .

Paperpal is an AI writing assistant that help academics write better, faster with real-time suggestions for in-depth language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of research manuscripts enhanced by professional academic editors, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- How Long Should a Chapter Be?

- How to Use Paperpal to Generate Emails & Cover Letters?

6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how to avoid it, you may also like, academic integrity vs academic dishonesty: types & examples, dissertation printing and binding | types & comparison , what is a dissertation preface definition and examples , the ai revolution: authors’ role in upholding academic..., the future of academia: how ai tools are..., how to write a research proposal: (with examples..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide).

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 5. The Literature Review

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys prior research published in books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have used in researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within existing scholarship about the topic.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014.

Importance of a Good Literature Review

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in the social sciences, a literature review usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

Given this, the purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011; Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Doing a Literature Review." PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (January 2006): 127-132; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012.

Types of Literature Reviews

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally among scholars that become part of the body of epistemological traditions within the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

NOTE: Most often the literature review will incorporate some combination of types. For example, a review that examines literature supporting or refuting an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem related to the research problem will also need to include writing supported by sources that establish the history of these arguments in the literature.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Thinking About Your Literature Review

The structure of a literature review should include the following in support of understanding the research problem :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Validity -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Basic Stages of Writing 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

Consider the following issues before writing the literature review: Clarify If your assignment is not specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions: 1. Roughly how many sources would be appropriate to include? 2. What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites; scholarly versus popular sources)? 3. Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique sources by discussing a common theme or issue? 4. Should I evaluate the sources in any way beyond evaluating how they relate to understanding the research problem? 5. Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history? Find Models Use the exercise of reviewing the literature to examine how authors in your discipline or area of interest have composed their literature review sections. Read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or to identify ways to organize your final review. The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read, such as required readings in the course syllabus, are also excellent entry points into your own research. Narrow the Topic The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to obtain a good survey of relevant resources. Your professor will probably not expect you to read everything that's available about the topic, but you'll make the act of reviewing easier if you first limit scope of the research problem. A good strategy is to begin by searching the USC Libraries Catalog for recent books about the topic and review the table of contents for chapters that focuses on specific issues. You can also review the indexes of books to find references to specific issues that can serve as the focus of your research. For example, a book surveying the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may include a chapter on the role Egypt has played in mediating the conflict, or look in the index for the pages where Egypt is mentioned in the text. Consider Whether Your Sources are Current Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. This is particularly true in disciplines in medicine and the sciences where research conducted becomes obsolete very quickly as new discoveries are made. However, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be required. In other words, a complete understanding the research problem requires you to deliberately examine how knowledge and perspectives have changed over time. Sort through other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to explore what is considered by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not.

III. Ways to Organize Your Literature Review

Chronology of Events If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials according to when they were published. This approach should only be followed if a clear path of research building on previous research can be identified and that these trends follow a clear chronological order of development. For example, a literature review that focuses on continuing research about the emergence of German economic power after the fall of the Soviet Union. By Publication Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on environmental studies of brown fields if the progression revealed, for example, a change in the soil collection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies. Thematic [“conceptual categories”] A thematic literature review is the most common approach to summarizing prior research in the social and behavioral sciences. Thematic reviews are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time, although the progression of time may still be incorporated into a thematic review. For example, a review of the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics could focus on the development of online political satire. While the study focuses on one topic, the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics, it would still be organized chronologically reflecting technological developments in media. The difference in this example between a "chronological" and a "thematic" approach is what is emphasized the most: themes related to the role of the Internet in presidential politics. Note that more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point being made. Methodological A methodological approach focuses on the methods utilized by the researcher. For the Internet in American presidential politics project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of American presidents on American, British, and French websites. Or the review might focus on the fundraising impact of the Internet on a particular political party. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed.

Other Sections of Your Literature Review Once you've decided on the organizational method for your literature review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out because they arise from your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period; a thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue. However, sometimes you may need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. However, only include what is necessary for the reader to locate your study within the larger scholarship about the research problem.

Here are examples of other sections, usually in the form of a single paragraph, you may need to include depending on the type of review you write:

- Current Situation : Information necessary to understand the current topic or focus of the literature review.

- Sources Used : Describes the methods and resources [e.g., databases] you used to identify the literature you reviewed.

- History : The chronological progression of the field, the research literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Selection Methods : Criteria you used to select (and perhaps exclude) sources in your literature review. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed [i.e., scholarly] sources.

- Standards : Description of the way in which you present your information.

- Questions for Further Research : What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

IV. Writing Your Literature Review

Once you've settled on how to organize your literature review, you're ready to write each section. When writing your review, keep in mind these issues.

Use Evidence A literature review section is, in this sense, just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence [citations] that demonstrates that what you are saying is valid. Be Selective Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the research problem, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological. Related items that provide additional information, but that are not key to understanding the research problem, can be included in a list of further readings . Use Quotes Sparingly Some short quotes are appropriate if you want to emphasize a point, or if what an author stated cannot be easily paraphrased. Sometimes you may need to quote certain terminology that was coined by the author, is not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. Do not use extensive quotes as a substitute for using your own words in reviewing the literature. Summarize and Synthesize Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each thematic paragraph as well as throughout the review. Recapitulate important features of a research study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study's significance and relating it to your own work and the work of others. Keep Your Own Voice While the literature review presents others' ideas, your voice [the writer's] should remain front and center. For example, weave references to other sources into what you are writing but maintain your own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with your own ideas and wording. Use Caution When Paraphrasing When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author's information or opinions accurately and in your own words. Even when paraphrasing an author’s work, you still must provide a citation to that work.

V. Common Mistakes to Avoid

These are the most common mistakes made in reviewing social science research literature.

- Sources in your literature review do not clearly relate to the research problem;

- You do not take sufficient time to define and identify the most relevant sources to use in the literature review related to the research problem;

- Relies exclusively on secondary analytical sources rather than including relevant primary research studies or data;

- Uncritically accepts another researcher's findings and interpretations as valid, rather than examining critically all aspects of the research design and analysis;

- Does not describe the search procedures that were used in identifying the literature to review;

- Reports isolated statistical results rather than synthesizing them in chi-squared or meta-analytic methods; and,

- Only includes research that validates assumptions and does not consider contrary findings and alternative interpretations found in the literature.

Cook, Kathleen E. and Elise Murowchick. “Do Literature Review Skills Transfer from One Course to Another?” Psychology Learning and Teaching 13 (March 2014): 3-11; Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . London: SAGE, 2011; Literature Review Handout. Online Writing Center. Liberty University; Literature Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2016; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012; Randolph, Justus J. “A Guide to Writing the Dissertation Literature Review." Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. vol. 14, June 2009; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016; Taylor, Dena. The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Writing a Literature Review. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra.

Writing Tip

Break Out of Your Disciplinary Box!

Thinking interdisciplinarily about a research problem can be a rewarding exercise in applying new ideas, theories, or concepts to an old problem. For example, what might cultural anthropologists say about the continuing conflict in the Middle East? In what ways might geographers view the need for better distribution of social service agencies in large cities than how social workers might study the issue? You don’t want to substitute a thorough review of core research literature in your discipline for studies conducted in other fields of study. However, particularly in the social sciences, thinking about research problems from multiple vectors is a key strategy for finding new solutions to a problem or gaining a new perspective. Consult with a librarian about identifying research databases in other disciplines; almost every field of study has at least one comprehensive database devoted to indexing its research literature.

Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Just Review for Content!

While conducting a review of the literature, maximize the time you devote to writing this part of your paper by thinking broadly about what you should be looking for and evaluating. Review not just what scholars are saying, but how are they saying it. Some questions to ask:

- How are they organizing their ideas?

- What methods have they used to study the problem?

- What theories have been used to explain, predict, or understand their research problem?

- What sources have they cited to support their conclusions?

- How have they used non-textual elements [e.g., charts, graphs, figures, etc.] to illustrate key points?

When you begin to write your literature review section, you'll be glad you dug deeper into how the research was designed and constructed because it establishes a means for developing more substantial analysis and interpretation of the research problem.

Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1 998.

Yet Another Writing Tip

When Do I Know I Can Stop Looking and Move On?

Here are several strategies you can utilize to assess whether you've thoroughly reviewed the literature:

- Look for repeating patterns in the research findings . If the same thing is being said, just by different people, then this likely demonstrates that the research problem has hit a conceptual dead end. At this point consider: Does your study extend current research? Does it forge a new path? Or, does is merely add more of the same thing being said?

- Look at sources the authors cite to in their work . If you begin to see the same researchers cited again and again, then this is often an indication that no new ideas have been generated to address the research problem.

- Search Google Scholar to identify who has subsequently cited leading scholars already identified in your literature review [see next sub-tab]. This is called citation tracking and there are a number of sources that can help you identify who has cited whom, particularly scholars from outside of your discipline. Here again, if the same authors are being cited again and again, this may indicate no new literature has been written on the topic.

Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2016; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

- << Previous: Theoretical Framework

- Next: Citation Tracking >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2024 11:05 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Research Methods

- Getting Started

- Literature Review Research

- Research Design

- Research Design By Discipline

- SAGE Research Methods

- Teaching with SAGE Research Methods

Literature Review

- What is a Literature Review?

- What is NOT a Literature Review?

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Literature Reviews vs. Systematic Reviews

- Systematic vs. Meta-Analysis

Literature Review is a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works.

Also, we can define a literature review as the collected body of scholarly works related to a topic:

- Summarizes and analyzes previous research relevant to a topic

- Includes scholarly books and articles published in academic journals

- Can be an specific scholarly paper or a section in a research paper

The objective of a Literature Review is to find previous published scholarly works relevant to an specific topic

- Help gather ideas or information

- Keep up to date in current trends and findings

- Help develop new questions

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

- Identifies critical gaps, points of disagreement, or potentially flawed methodology or theoretical approaches.

- Indicates potential directions for future research.

All content in this section is from Literature Review Research from Old Dominion University

Keep in mind the following, a literature review is NOT:

Not an essay

Not an annotated bibliography in which you summarize each article that you have reviewed. A literature review goes beyond basic summarizing to focus on the critical analysis of the reviewed works and their relationship to your research question.

Not a research paper where you select resources to support one side of an issue versus another. A lit review should explain and consider all sides of an argument in order to avoid bias, and areas of agreement and disagreement should be highlighted.

A literature review serves several purposes. For example, it

- provides thorough knowledge of previous studies; introduces seminal works.

- helps focus one’s own research topic.

- identifies a conceptual framework for one’s own research questions or problems; indicates potential directions for future research.

- suggests previously unused or underused methodologies, designs, quantitative and qualitative strategies.

- identifies gaps in previous studies; identifies flawed methodologies and/or theoretical approaches; avoids replication of mistakes.

- helps the researcher avoid repetition of earlier research.

- suggests unexplored populations.

- determines whether past studies agree or disagree; identifies controversy in the literature.

- tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

As Kennedy (2007) notes*, it is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the original studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally that become part of the lore of field. In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews.

Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are several approaches to how they can be done, depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study. Listed below are definitions of types of literature reviews:

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews.

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical reviews are focused on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [content], but how they said it [method of analysis]. This approach provides a framework of understanding at different levels (i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches and data collection and analysis techniques), enables researchers to draw on a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection and data analysis, and helps highlight many ethical issues which we should be aware of and consider as we go through our study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review. Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?"

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to concretely examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review help establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

* Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147.

All content in this section is from The Literature Review created by Dr. Robert Larabee USC

Robinson, P. and Lowe, J. (2015), Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39: 103-103. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12393

What's in the name? The difference between a Systematic Review and a Literature Review, and why it matters . By Lynn Kysh from University of Southern California

Systematic review or meta-analysis?

A systematic review answers a defined research question by collecting and summarizing all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria.

A meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of these studies.

Systematic reviews, just like other research articles, can be of varying quality. They are a significant piece of work (the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at York estimates that a team will take 9-24 months), and to be useful to other researchers and practitioners they should have:

- clearly stated objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies

- explicit, reproducible methodology

- a systematic search that attempts to identify all studies

- assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies (e.g. risk of bias)

- systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies

Not all systematic reviews contain meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects of health care than those derived from the individual studies included within a review. More information on meta-analyses can be found in Cochrane Handbook, Chapter 9 .

A meta-analysis goes beyond critique and integration and conducts secondary statistical analysis on the outcomes of similar studies. It is a systematic review that uses quantitative methods to synthesize and summarize the results.

An advantage of a meta-analysis is the ability to be completely objective in evaluating research findings. Not all topics, however, have sufficient research evidence to allow a meta-analysis to be conducted. In that case, an integrative review is an appropriate strategy.

Some of the content in this section is from Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: step by step guide created by Kate McAllister.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Research Design >>

- Last Updated: Jul 15, 2024 10:34 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.udel.edu/researchmethods

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How To Write A Literature Review - A Complete Guide

Table of Contents

A literature review is much more than just another section in your research paper. It forms the very foundation of your research. It is a formal piece of writing where you analyze the existing theoretical framework, principles, and assumptions and use that as a base to shape your approach to the research question.

Curating and drafting a solid literature review section not only lends more credibility to your research paper but also makes your research tighter and better focused. But, writing literature reviews is a difficult task. It requires extensive reading, plus you have to consider market trends and technological and political changes, which tend to change in the blink of an eye.

Now streamline your literature review process with the help of SciSpace Copilot. With this AI research assistant, you can efficiently synthesize and analyze a vast amount of information, identify key themes and trends, and uncover gaps in the existing research. Get real-time explanations, summaries, and answers to your questions for the paper you're reviewing, making navigating and understanding the complex literature landscape easier.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore everything from the definition of a literature review, its appropriate length, various types of literature reviews, and how to write one.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a collation of survey, research, critical evaluation, and assessment of the existing literature in a preferred domain.

Eminent researcher and academic Arlene Fink, in her book Conducting Research Literature Reviews , defines it as the following:

“A literature review surveys books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated.

Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have explored while researching a particular topic, and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within a larger field of study.”

Simply put, a literature review can be defined as a critical discussion of relevant pre-existing research around your research question and carving out a definitive place for your study in the existing body of knowledge. Literature reviews can be presented in multiple ways: a section of an article, the whole research paper itself, or a chapter of your thesis.

A literature review does function as a summary of sources, but it also allows you to analyze further, interpret, and examine the stated theories, methods, viewpoints, and, of course, the gaps in the existing content.

As an author, you can discuss and interpret the research question and its various aspects and debate your adopted methods to support the claim.

What is the purpose of a literature review?

A literature review is meant to help your readers understand the relevance of your research question and where it fits within the existing body of knowledge. As a researcher, you should use it to set the context, build your argument, and establish the need for your study.

What is the importance of a literature review?

The literature review is a critical part of research papers because it helps you:

- Gain an in-depth understanding of your research question and the surrounding area

- Convey that you have a thorough understanding of your research area and are up-to-date with the latest changes and advancements

- Establish how your research is connected or builds on the existing body of knowledge and how it could contribute to further research

- Elaborate on the validity and suitability of your theoretical framework and research methodology

- Identify and highlight gaps and shortcomings in the existing body of knowledge and how things need to change

- Convey to readers how your study is different or how it contributes to the research area

How long should a literature review be?

Ideally, the literature review should take up 15%-40% of the total length of your manuscript. So, if you have a 10,000-word research paper, the minimum word count could be 1500.

Your literature review format depends heavily on the kind of manuscript you are writing — an entire chapter in case of doctoral theses, a part of the introductory section in a research article, to a full-fledged review article that examines the previously published research on a topic.

Another determining factor is the type of research you are doing. The literature review section tends to be longer for secondary research projects than primary research projects.

What are the different types of literature reviews?

All literature reviews are not the same. There are a variety of possible approaches that you can take. It all depends on the type of research you are pursuing.

Here are the different types of literature reviews:

Argumentative review

It is called an argumentative review when you carefully present literature that only supports or counters a specific argument or premise to establish a viewpoint.

Integrative review

It is a type of literature review focused on building a comprehensive understanding of a topic by combining available theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence.

Methodological review

This approach delves into the ''how'' and the ''what" of the research question — you cannot look at the outcome in isolation; you should also review the methodology used.

Systematic review

This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research and collect, report, and analyze data from the studies included in the review.

Meta-analysis review

Meta-analysis uses statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects than those derived from the individual studies included within a review.

Historical review

Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, or phenomenon emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and identify future research's likely directions.

Theoretical Review

This form aims to examine the corpus of theory accumulated regarding an issue, concept, theory, and phenomenon. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories exist, the relationships between them, the degree the existing approaches have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested.

Scoping Review

The Scoping Review is often used at the beginning of an article, dissertation, or research proposal. It is conducted before the research to highlight gaps in the existing body of knowledge and explains why the project should be greenlit.

State-of-the-Art Review

The State-of-the-Art review is conducted periodically, focusing on the most recent research. It describes what is currently known, understood, or agreed upon regarding the research topic and highlights where there are still disagreements.

Can you use the first person in a literature review?

When writing literature reviews, you should avoid the usage of first-person pronouns. It means that instead of "I argue that" or "we argue that," the appropriate expression would be "this research paper argues that."

Do you need an abstract for a literature review?

Ideally, yes. It is always good to have a condensed summary that is self-contained and independent of the rest of your review. As for how to draft one, you can follow the same fundamental idea when preparing an abstract for a literature review. It should also include:

- The research topic and your motivation behind selecting it

- A one-sentence thesis statement

- An explanation of the kinds of literature featured in the review

- Summary of what you've learned

- Conclusions you drew from the literature you reviewed

- Potential implications and future scope for research

Here's an example of the abstract of a literature review

Is a literature review written in the past tense?

Yes, the literature review should ideally be written in the past tense. You should not use the present or future tense when writing one. The exceptions are when you have statements describing events that happened earlier than the literature you are reviewing or events that are currently occurring; then, you can use the past perfect or present perfect tenses.

How many sources for a literature review?

There are multiple approaches to deciding how many sources to include in a literature review section. The first approach would be to look level you are at as a researcher. For instance, a doctoral thesis might need 60+ sources. In contrast, you might only need to refer to 5-15 sources at the undergraduate level.

The second approach is based on the kind of literature review you are doing — whether it is merely a chapter of your paper or if it is a self-contained paper in itself. When it is just a chapter, sources should equal the total number of pages in your article's body. In the second scenario, you need at least three times as many sources as there are pages in your work.

Quick tips on how to write a literature review

To know how to write a literature review, you must clearly understand its impact and role in establishing your work as substantive research material.

You need to follow the below-mentioned steps, to write a literature review:

- Outline the purpose behind the literature review

- Search relevant literature

- Examine and assess the relevant resources

- Discover connections by drawing deep insights from the resources

- Structure planning to write a good literature review

1. Outline and identify the purpose of a literature review

As a first step on how to write a literature review, you must know what the research question or topic is and what shape you want your literature review to take. Ensure you understand the research topic inside out, or else seek clarifications. You must be able to the answer below questions before you start:

- How many sources do I need to include?

- What kind of sources should I analyze?

- How much should I critically evaluate each source?

- Should I summarize, synthesize or offer a critique of the sources?

- Do I need to include any background information or definitions?

Additionally, you should know that the narrower your research topic is, the swifter it will be for you to restrict the number of sources to be analyzed.

2. Search relevant literature

Dig deeper into search engines to discover what has already been published around your chosen topic. Make sure you thoroughly go through appropriate reference sources like books, reports, journal articles, government docs, and web-based resources.

You must prepare a list of keywords and their different variations. You can start your search from any library’s catalog, provided you are an active member of that institution. The exact keywords can be extended to widen your research over other databases and academic search engines like:

- Google Scholar

- Microsoft Academic

- Science.gov

Besides, it is not advisable to go through every resource word by word. Alternatively, what you can do is you can start by reading the abstract and then decide whether that source is relevant to your research or not.

Additionally, you must spend surplus time assessing the quality and relevance of resources. It would help if you tried preparing a list of citations to ensure that there lies no repetition of authors, publications, or articles in the literature review.

3. Examine and assess the sources

It is nearly impossible for you to go through every detail in the research article. So rather than trying to fetch every detail, you have to analyze and decide which research sources resemble closest and appear relevant to your chosen domain.

While analyzing the sources, you should look to find out answers to questions like:

- What question or problem has the author been describing and debating?

- What is the definition of critical aspects?

- How well the theories, approach, and methodology have been explained?

- Whether the research theory used some conventional or new innovative approach?

- How relevant are the key findings of the work?

- In what ways does it relate to other sources on the same topic?

- What challenges does this research paper pose to the existing theory

- What are the possible contributions or benefits it adds to the subject domain?

Be always mindful that you refer only to credible and authentic resources. It would be best if you always take references from different publications to validate your theory.

Always keep track of important information or data you can present in your literature review right from the beginning. It will help steer your path from any threats of plagiarism and also make it easier to curate an annotated bibliography or reference section.

4. Discover connections

At this stage, you must start deciding on the argument and structure of your literature review. To accomplish this, you must discover and identify the relations and connections between various resources while drafting your abstract.

A few aspects that you should be aware of while writing a literature review include:

- Rise to prominence: Theories and methods that have gained reputation and supporters over time.

- Constant scrutiny: Concepts or theories that repeatedly went under examination.

- Contradictions and conflicts: Theories, both the supporting and the contradictory ones, for the research topic.

- Knowledge gaps: What exactly does it fail to address, and how to bridge them with further research?

- Influential resources: Significant research projects available that have been upheld as milestones or perhaps, something that can modify the current trends

Once you join the dots between various past research works, it will be easier for you to draw a conclusion and identify your contribution to the existing knowledge base.

5. Structure planning to write a good literature review

There exist different ways towards planning and executing the structure of a literature review. The format of a literature review varies and depends upon the length of the research.

Like any other research paper, the literature review format must contain three sections: introduction, body, and conclusion. The goals and objectives of the research question determine what goes inside these three sections.

Nevertheless, a good literature review can be structured according to the chronological, thematic, methodological, or theoretical framework approach.

Literature review samples

1. Standalone

2. As a section of a research paper

How SciSpace Discover makes literature review a breeze?

SciSpace Discover is a one-stop solution to do an effective literature search and get barrier-free access to scientific knowledge. It is an excellent repository where you can find millions of only peer-reviewed articles and full-text PDF files. Here’s more on how you can use it:

Find the right information

Find what you want quickly and easily with comprehensive search filters that let you narrow down papers according to PDF availability, year of publishing, document type, and affiliated institution. Moreover, you can sort the results based on the publishing date, citation count, and relevance.

Assess credibility of papers quickly

When doing the literature review, it is critical to establish the quality of your sources. They form the foundation of your research. SciSpace Discover helps you assess the quality of a source by providing an overview of its references, citations, and performance metrics.

Get the complete picture in no time