- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Full text: Bush's speech

My fellow citizens, events in Iraq have now reached the final days of decision. For more than a decade, the United States and other nations have pursued patient and honorable efforts to disarm the Iraqi regime without war. That regime pledged to reveal and destroy all its weapons of mass destruction as a condition for ending the Persian Gulf War in 1991.

Since then, the world has engaged in 12 years of diplomacy. We have passed more than a dozen resolutions in the United Nations Security Council. We have sent hundreds of weapons inspectors to oversee the disarmament of Iraq. Our good faith has not been returned.

The Iraqi regime has used diplomacy as a ploy to gain time and advantage. It has uniformly defied Security Council resolutions demanding full disarmament. Over the years, U.N. weapon inspectors have been threatened by Iraqi officials, electronically bugged, and systematically deceived. Peaceful efforts to disarm the Iraqi regime have failed again and again -- because we are not dealing with peaceful men.

Intelligence gathered by this and other governments leaves no doubt that the Iraq regime continues to possess and conceal some of the most lethal weapons ever devised. This regime has already used weapons of mass destruction against Iraq's neighbors and against Iraq's people.

The regime has a history of reckless aggression in the Middle East. It has a deep hatred of America and our friends. And it has aided, trained and harbored terrorists, including operatives of al Qaeda.

The danger is clear: using chemical, biological or, one day, nuclear weapons, obtained with the help of Iraq, the terrorists could fulfill their stated ambitions and kill thousands or hundreds of thousands of innocent people in our country, or any other.

The United States and other nations did nothing to deserve or invite this threat. But we will do everything to defeat it. Instead of drifting along toward tragedy, we will set a course toward safety. Before the day of horror can come, before it is too late to act, this danger will be removed.

The United States of America has the sovereign authority to use force in assuring its own national security. That duty falls to me, as Commander-in-Chief, by the oath I have sworn, by the oath I will keep.

Recognizing the threat to our country, the United States Congress voted overwhelmingly last year to support the use of force against Iraq. America tried to work with the United Nations to address this threat because we wanted to resolve the issue peacefully. We believe in the mission of the United Nations. One reason the UN was founded after the second world war was to confront aggressive dictators, actively and early, before they can attack the innocent and destroy the peace.

In the case of Iraq, the Security Council did act, in the early 1990s. Under Resolutions 678 and 687 - both still in effect - the United States and our allies are authorized to use force in ridding Iraq of weapons of mass destruction. This is not a question of authority, it is a question of will.

Last September, I went to the U.N. General Assembly and urged the nations of the world to unite and bring an end to this danger. On November 8, the Security Council unanimously passed Resolution 1441, finding Iraq in material breach of its obligations, and vowing serious consequences if Iraq did not fully and immediately disarm.

Today, no nation can possibly claim that Iraq has disarmed. And it will not disarm so long as Saddam Hussein holds power. For the last four-and-a-half months, the United States and our allies have worked within the Security Council to enforce that Council's long-standing demands. Yet, some permanent members of the Security Council have publicly announced they will veto any resolution that compels the disarmament of Iraq. These governments share our assessment of the danger, but not our resolve to meet it. Many nations, however, do have the resolve and fortitude to act against this threat to peace, and a broad coalition is now gathering to enforce the just demands of the world. The United Nations Security Council has not lived up to its responsibilities, so we will rise to ours.

In recent days, some governments in the Middle East have been doing their part. They have delivered public and private messages urging the dictator to leave Iraq, so that disarmament can proceed peacefully. He has thus far refused. All the decades of deceit and cruelty have now reached an end. Saddam Hussein and his sons must leave Iraq within 48 hours. Their refusal to do so will result in military conflict, commenced at a time of our choosing. For their own safety, all foreign nationals - including journalists and inspectors - should leave Iraq immediately.

Many Iraqis can hear me tonight in a translated radio broadcast, and I have a message for them. If we must begin a military campaign, it will be directed against the lawless men who rule your country and not against you. As our coalition takes away their power, we will deliver the food and medicine you need. We will tear down the apparatus of terror and we will help you to build a new Iraq that is prosperous and free. In a free Iraq, there will be no more wars of aggression against your neighbors, no more poison factories, no more executions of dissidents, no more torture chambers and rape rooms. The tyrant will soon be gone. The day of your liberation is near.

It is too late for Saddam Hussein to remain in power. It is not too late for the Iraqi military to act with honor and protect your country by permitting the peaceful entry of coalition forces to eliminate weapons of mass destruction. Our forces will give Iraqi military units clear instructions on actions they can take to avoid being attacked and destroyed. I urge every member of the Iraqi military and intelligence services, if war comes, do not fight for a dying regime that is not worth your own life.

And all Iraqi military and civilian personnel should listen carefully to this warning. In any conflict, your fate will depend on your action. Do not destroy oil wells, a source of wealth that belongs to the Iraqi people. Do not obey any command to use weapons of mass destruction against anyone, including the Iraqi people. War crimes will be prosecuted. War criminals will be punished. And it will be no defense to say, "I was just following orders."

Should Saddam Hussein choose confrontation, the American people can know that every measure has been taken to avoid war, and every measure will be taken to win it. Americans understand the costs of conflict because we have paid them in the past. War has no certainty, except the certainty of sacrifice.

Yet, the only way to reduce the harm and duration of war is to apply the full force and might of our military, and we are prepared to do so. If Saddam Hussein attempts to cling to power, he will remain a deadly foe until the end. In desperation, he and terrorists groups might try to conduct terrorist operations against the American people and our friends. These attacks are not inevitable. They are, however, possible. And this very fact underscores the reason we cannot live under the threat of blackmail. The terrorist threat to America and the world will be diminished the moment that Saddam Hussein is disarmed.

Our government is on heightened watch against these dangers. Just as we are preparing to ensure victory in Iraq, we are taking further actions to protect our homeland. In recent days, American authorities have expelled from the country certain individuals with ties to Iraqi intelligence services. Among other measures, I have directed additional security of our airports, and increased Coast Guard patrols of major seaports. The Department of Homeland Security is working closely with the nation's governors to increase armed security at critical facilities across America.

Should enemies strike our country, they would be attempting to shift our attention with panic and weaken our morale with fear. In this, they would fail. No act of theirs can alter the course or shake the resolve of this country. We are a peaceful people - yet we're not a fragile people, and we will not be intimidated by thugs and killers. If our enemies dare to strike us, they and all who have aided them, will face fearful consequences.

We are now acting because the risks of inaction would be far greater. In one year, or five years, the power of Iraq to inflict harm on all free nations would be multiplied many times over. With these capabilities, Saddam Hussein and his terrorist allies could choose the moment of deadly conflict when they are strongest. We choose to meet that threat now, where it arises, before it can appear suddenly in our skies and cities.

The cause of peace requires all free nations to recognize new and undeniable realities. In the 20th century, some chose to appease murderous dictators, whose threats were allowed to grow into genocide and global war. In this century, when evil men plot chemical, biological and nuclear terror, a policy of appeasement could bring destruction of a kind never before seen on this earth.

Terrorists and terror states do not reveal these threats with fair notice, in formal declarations - and responding to such enemies only after they have struck first is not self-defense, it is suicide. The security of the world requires disarming Saddam Hussein now.

As we enforce the just demands of the world, we will also honor the deepest commitments of our country. Unlike Saddam Hussein, we believe the Iraqi people are deserving and capable of human liberty. And when the dictator has departed, they can set an example to all the Middle East of a vital and peaceful and self-governing nation.

The United States, with other countries, will work to advance liberty and peace in that region. Our goal will not be achieved overnight, but it can come over time. The power and appeal of human liberty is felt in every life and every land. And the greatest power of freedom is to overcome hatred and violence, and turn the creative gifts of men and women to the pursuits of peace.

That is the future we choose. Free nations have a duty to defend our people by uniting against the violent. And tonight, as we have done before, America and our allies accept that responsibility.

Good night, and may God continue to bless America.

- Middle East and north Africa

Most viewed

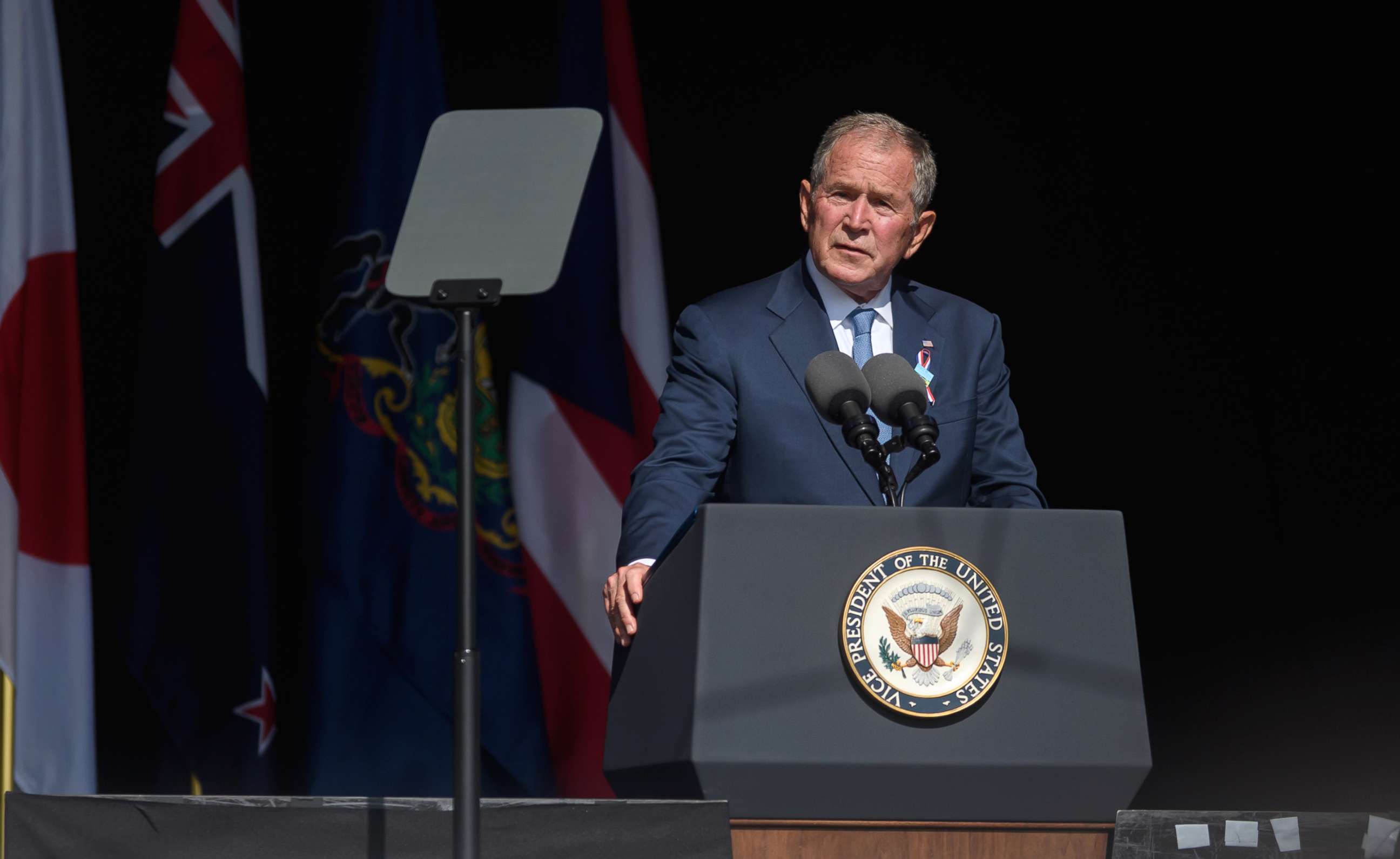

Bush condemns 'unjustified and brutal' invasion of Iraq, instead of Ukraine, in speech gaffe

Realizing his mistake, the former president made a joke about his age.

Former President George W. Bush had a tongue-tied moment at a speech on Wednesday and millions on social media took notice.

When condemning Russia's attack on Ukraine , Bush mistakenly referred to the decision to launch an "unjustified and brutal invasion of Iraq" before quickly correcting himself to say "Ukraine," in what was a bungled criticism of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

"The result is an absence of checks and balances in Russia, and the decision of one man to launch a wholly unjustified and brutal invasion of Iraq," said Bush, before catching himself and shaking his head. "I mean -- of Ukraine."

Realizing his mistake, Bush then appeared to say under his breath, "Iraq, too."

MORE: Russia-Ukraine updates: US sanctions Russian military shipbuilder, diamond miner

Bush made the comment in a speech at his presidential center at Southern Methodist University in Dallas on Wednesday during an event examining the future of American elections. After a pause, Bush blamed the mistake on his age and the audience laughed.

"Anyway, [I'm] 75," he said.

But on Twitter, the reaction to Bush's inadvertent reference to the most polarizing decision of his administration was mixed, as users revived criticism of his decision to invade and sarcastically riffed on his history of such slip-ups .

MORE: Pennsylvania GOP reaps what Trump sows: The Note

Former Rep. Joe Walsh, who ran for the Republican nomination for president in 2020, tweeted as the clip swirled through social media: "All gaffes aside, George W Bush was wrong to invade Iraq. And Putin was wrong to invade Ukraine."

Another user cracked that "Freud really stepped out of his grave to personally slap the ‘Iraq’ out of Bush’s mouth didn’t he."

The mixup was widely seen. Since video of Bush's speech was clipped and tweeted by Dallas Morning News reporter Michael Williams on Wednesday, it has been viewed more than 17 million times.

MORE: Iraq Invasion 12 Years Later: See How Much Has Changed

In his Wednesday remarks, Bush also described Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy as a "cool little guy," deeming him "the [Winston] Churchill of the 21st century."

Related Stories

Mom accused of leaving kids home alone for cruise

- Apr 12, 1:54 PM

Biden warns Iran on retaliatory strike on Israel

- Apr 12, 8:03 PM

OJ Simpson dies at 76

- Apr 11, 6:32 PM

As president, Bush oversaw the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 -- as part of the post-9/11 conflicts in the Middle East -- under the pretext that the country was hiding weapons of mass destruction, or WMDs. Iraq's dictator, Saddam Hussein, was deposed but no weapons were found, and the war officially lasted for nearly a decade.

While the Bush administration argued the fighting was necessary for national security even without the WMDs, it became increasingly unpopular at home. Thousands of U.S. service members and tens of thousands of civilians died.

Bush wrote in his post-White House memoir that he had a "sickening feeling" when he learned there were no WMDs in Iraq after their supposed existence was used as justification for the invasion. He told ABC News' "World News Tonight" when leaving office in 2008 that the "biggest regret" of his presidency was what he called the "intelligence failure in Iraq."

MORE: Bush: 'I Did Not Compromise My Principles'

When pressed in that interview, Bush declined to "speculate" on whether he would still have gone to war if he knew Iraq didn't have WMDs. "That is a do-over that I can't do," he said.

Nonetheless, he wrote in his memoir, "I strongly believe that removing Saddam from power was the right decision."

ABC News' Chris Donovan contributed to this report.

Related Topics

- George W. Bush

How 2 teenagers plotted their best friend's murder

- Apr 12, 1:14 PM

6 dead, suspect killed in attack at Sydney mall

- Apr 13, 1:00 PM

ABC News Live

24/7 coverage of breaking news and live events

clock This article was published more than 1 year ago

George W. Bush called Iraq war ‘unjustified and brutal.’ He meant Ukraine.

It was the “decision of one man to launch a wholly unjustified and brutal invasion of Iraq,” former president George W. Bush said Wednesday before quickly correcting himself, saying he meant to describe Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine.

“Iraq, too, anyway,” he added under his breath to laughter from the audience during a speech at his presidential center in Dallas.

But while the joke landed with some, many were quick to pounce on his verbal slip after nearly two decades of sharp criticism that Bush was unjustified in directing the United States’ 2003 invasion of Iraq, with some lobbing accusations that the 43rd president is a war criminal — the same label some have given Putin after his invasion of Ukraine this year , which has been widely criticized by the international community as illegal and inhumane.

“I’m not laughing, and I am guessing nor are the families of the thousands of American troops and the hundreds of thousands of Iraqis who died in that war,” said Mehdi Hasan, a liberal commentator and cable news host, on “MSNBC Prime” on Wednesday night.

“How many Americans were sent to die by him for a lie? Disgusting,” tweeted conservative media personality Tim Young .

At least 200,000 civilians died as a result of “direct war-related violence” during the U.S. invasion of Iraq, according to the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University, which noted that difficulties in measuring deaths accurately mean the toll was probably much higher.

Political consensus among many on the left and right has since moved to largely condemn the war, with many presidential hopefuls and other politicians nudged to say that they were then or are now against the Iraq invasion.

Even Bush’s brother Jeb, in a 2015 presidential debate , when asked by moderator Megyn Kelly whether “your brother’s war was a mistake,” said the invasion was wrong and based on “faulty intelligence.”

“Oof,” tweeted Justin Amash, a former congressman who left the Republican Party to become an independent, in reaction to the video of Bush’s gaffe.

“If you were George W. Bush, you think you’d just steer clear of giving any speech about one man launching a wholly unjustified and brutal invasion,” he said.

“Welcome to the resistance,” G. Elliott Morris, a U.S. correspondent for the Economist, joked on Twitter.

“George W. Bush is a war criminal,” tweeted former Ohio state senator Nina Turner.

Just before the slip-up, Bush — who at 75 blamed the gaffe on his age — had been comparing the leadership of Russia and Ukraine. He praised Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, whom he called a “cool little guy” and “the Churchill of the 21st century,” the latter statement echoing one he made after the two met virtually this month.

As for Russia, Bush said that its elections are rigged and its political opponents imprisoned. “The result is an absence of checks and balances in Russia.”

The George W. Bush Presidential Center did not immediately respond to a request for a comment.

- How Russia learned from mistakes to slow Ukraine’s counteroffensive September 8, 2023 How Russia learned from mistakes to slow Ukraine’s counteroffensive September 8, 2023

- Before Prigozhin plane crash, Russia was preparing for life after Wagner August 28, 2023 Before Prigozhin plane crash, Russia was preparing for life after Wagner August 28, 2023

- Inside the Russian effort to build 6,000 attack drones with Iran’s help August 17, 2023 Inside the Russian effort to build 6,000 attack drones with Iran’s help August 17, 2023

Watch CBS News

Full Transcript Of Bush's Iraq Speech

By Alfonso Serrano

January 10, 2007 / 5:58 PM EST / CBS

Below is the text of President Bush's speech on Iraq that he delivered on Wednesday night:

When I addressed you just over a year ago, nearly 12 million Iraqis had cast their ballots for a unified and democratic nation. The elections of 2005 were a stunning achievement. We thought that these elections would bring the Iraqis together — and that as we trained Iraqi security forces, we could accomplish our mission with fewer American troops.

But in 2006, the opposite happened. The violence in Iraq — particularly in Baghdad — overwhelmed the political gains the Iraqis had made. Al Qaeda terrorists and Sunni insurgents recognized the mortal danger that Iraq's elections posed for their cause, and they responded with outrageous acts of murder aimed at innocent Iraqis. They blew up one of the holiest shrines in Shia Islam — the Golden Mosque of Samarra — in a calculated effort to provoke Iraq's Shia population to retaliate. Their strategy worked. Radical Shia elements, some supported by Iran, formed death squads. And the result was a vicious cycle of sectarian violence that continues today.

The situation in Iraq is unacceptable to the American people — and it is unacceptable to me. Our troops in Iraq have fought bravely. They have done everything we have asked them to do. Where mistakes have been made, the responsibility rests with me.

It is clear that we need to change our strategy in Iraq. So my national security team, military commanders, and diplomats conducted a comprehensive review. We consulted Members of Congress from both parties, allies abroad, and distinguished outside experts. We benefited from the thoughtful recommendations of the Iraq Study Group — a bipartisan panel led by former Secretary of State James Baker and former Congressman Lee Hamilton. In our discussions, we all agreed that there is no magic formula for success in Iraq. And one message came through loud and clear: Failure in Iraq would be a disaster for the United States.

The consequences of failure are clear: Radical Islamic extremists would grow in strength and gain new recruits. They would be in a better position to topple moderate governments, create chaos in the region and use oil revenues to fund their ambitions. Iran would be emboldened in its pursuit of nuclear weapons. Our enemies would have a safe haven from which to plan and launch attacks on the American people. On September the 11th, 2001, we saw what a refuge for extremists on the other side of the world could bring to the streets of our own cities. For the safety of our people, America must succeed in Iraq.

The most urgent priority for success in Iraq is security, especially in Baghdad. Eighty percent of Iraq's sectarian violence occurs within 30 miles of the capital. This violence is splitting Baghdad into sectarian enclaves and shaking the confidence of all Iraqis. Only the Iraqis can end the sectarian violence and secure their people. And their government has put forward an aggressive plan to do it.

Our past efforts to secure Baghdad failed for two principal reasons: There were not enough Iraqi and American troops to secure neighborhoods that had been cleared of terrorists and insurgents, and there were too many restrictions on the troops we did have. Our military commanders reviewed the new Iraqi plan to ensure that it addressed these mistakes. They report that it does. They also report that this plan can work.

Let me explain the main elements of this effort.

The Iraqi government will appoint a military commander and two deputy commanders for their capital. The Iraqi government will deploy Iraqi Army and National Police brigades across Baghdad's nine districts. When these forces are fully deployed, there will be 18 Iraqi Army and National Police brigades committed to this effort — along with local police. These Iraqi forces will operate from local police stations — conducting patrols, setting up checkpoints, and going door-to-door to gain the trust of Baghdad residents.

This is a strong commitment. But for it to succeed, our commanders say the Iraqis will need our help. So America will change our strategy to help the Iraqis carry out their campaign to put down sectarian violence and bring security to the people of Baghdad. This will require increasing American force levels. So I have committed more than 20,000 additional American troops to Iraq. The vast majority of them — five brigades — will be deployed to Baghdad. These troops will work alongside Iraqi units and be embedded in their formations. Our troops will have a well-defined mission: To help Iraqis clear and secure neighborhoods, to help them protect the local population, and to help ensure that the Iraqi forces left behind are capable of providing the security that Baghdad needs.

Many listening tonight will ask why this effort will succeed when previous operations to secure Baghdad did not. Here are the differences: In earlier operations, Iraqi and American forces cleared many neighborhoods of terrorists and insurgents — but when our forces moved on to other targets, the killers returned. This time, we will have the force levels we need to hold the areas that have been cleared. In earlier operations, political and sectarian interference prevented Iraqi and American forces from going into neighborhoods that are home to those fueling the sectarian violence. This time, Iraqi and American forces will have a green light to enter these neighborhoods — and Prime Minister Maliki has pledged that political or sectarian interference will not be tolerated.

I have made it clear to the Prime Minister and Iraq's other leaders that America's commitment is not open-ended. If the Iraqi government does not follow through on its promises, it will lose the support of the American people — and it will lose the support of the Iraqi people. Now is the time to act. The Prime Minister understands this. Here is what he told his people just last week: "The Baghdad security plan will not provide a safe haven for any outlaws, regardless of [their] sectarian or political affiliation."

This new strategy will not yield an immediate end to suicide bombings, assassinations, or IED attacks. Our enemies in Iraq will make every effort to ensure that our television screens are filled with images of death and suffering. Yet over time, we can expect to see Iraqi troops chasing down murderers, fewer brazen acts of terror, and growing trust and cooperation from Baghdad's residents. When this happens, daily life will improve, Iraqis will gain confidence in their leaders, and the government will have the breathing space it needs to make progress in other critical areas. Most of Iraq's Sunni and Shia want to live together in peace — and reducing the violence in Baghdad will help make reconciliation possible.

A successful strategy for Iraq goes beyond military operations. Ordinary Iraqi citizens must see that military operations are accompanied by visible improvements in their neighborhoods and communities. So America will hold the Iraqi government to the benchmarks it has announced.

To establish its authority, the Iraqi government plans to take responsibility for security in all of Iraq's provinces by November. To give every Iraqi citizen a stake in the country's economy, Iraq will pass legislation to share oil revenues among all Iraqis. To show that it is committed to delivering a better life, the Iraqi government will spend $10 billion of its own money on reconstruction and infrastructure projects that will create new jobs. To empower local leaders, Iraqis plan to hold provincial elections later this year. And to allow more Iraqis to re-enter their nation's political life, the government will reform de-Baathification laws — and establish a fair process for considering amendments to Iraq's constitution.

America will change our approach to help the Iraqi government as it works to meet these benchmarks. In keeping with the recommendations of the Iraq Study Group, we will increase the embedding of American advisers in Iraqi Army units — and partner a Coalition brigade with every Iraqi Army division.

We will help the Iraqis build a larger and better-equipped army — and we will accelerate the training of Iraqi forces, which remains the essential U.S. security mission in Iraq. We will give our commanders and civilians greater flexibility to spend funds for economic assistance. We will double the number of provincial reconstruction teams. These teams bring together military and civilian experts to help local Iraqi communities pursue reconciliation, strengthen moderates, and speed the transition to Iraqi self reliance. And Secretary Rice will soon appoint a reconstruction coordinator in Baghdad to ensure better results for economic assistance being spent in Iraq. As we make these changes, we will continue to pursue al Qaeda and foreign fighters. Al Qaeda is still active in Iraq. Its home base is Anbar Province. Al Qaeda has helped make Anbar the most violent area of Iraq outside the capital. A captured al Qaeda document describes the terrorists' plan to infiltrate and seize control of the province. This would bring al Qaeda closer to its goals of taking down Iraq's democracy, building a radical Islamic empire and launching new attacks on the United States at home and abroad.

Our military forces in Anbar are killing and capturing al Qaeda leaders — and protecting the local population. Recently, local tribal leaders have begun to show their willingness to take on al Qaeda. As a result, our commanders believe we have an opportunity to deal a serious blow to the terrorists. So I have given orders to increase American forces in Anbar Province by 4,000 troops. These troops will work with Iraqi and tribal forces to step up the pressure on the terrorists. America's men and women in uniform took away al Qaeda's safe haven in Afghanistan — and we will not allow them to re-establish it in Iraq.

Succeeding in Iraq also requires defending its territorial integrity — and stabilizing the region in the face of the extremist challenge. This begins with addressing Iran and Syria. These two regimes are allowing terrorists and insurgents to use their territory to move in and out of Iraq. Iran is providing material support for attacks on American troops. We will disrupt the attacks on our forces. We will interrupt the flow of support from Iran and Syria. And we will seek out and destroy the networks providing advanced weaponry and training to our enemies in Iraq.

We are also taking other steps to bolster the security of Iraq and protect American interests in the Middle East. I recently ordered the deployment of an additional carrier strike group to the region. We will expand intelligence sharing — and deploy Patriot air defense systems to reassure our friends and allies. We will work with the governments of Turkey and Iraq to help them resolve problems along their border. And we will work with others to prevent Iran from gaining nuclear weapons and dominating the region.

We will use America's full diplomatic resources to rally support for Iraq from nations throughout the Middle East. Countries like Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, and the Gulf States need to understand that an American defeat in Iraq would create a new sanctuary for extremists — and a strategic threat to their survival. These nations have a stake in a successful Iraq that is at peace with its neighbors — and they must step up their support for Iraq's unity government. We endorse the Iraqi government's call to finalize an International Compact that will bring new economic assistance in exchange for greater economic reform. And on Friday, Secretary Rice will leave for the region — to build support for Iraq and continue the urgent diplomacy required to help bring peace to the Middle East.

The challenge playing out across the broader Middle East is more than a military conflict. It is the decisive ideological struggle of our time. On one side are those who believe in freedom and moderation. On the other side are extremists who kill the innocent and have declared their intention to destroy our way of life. In the long run, the most realistic way to protect the American people is to provide a hopeful alternative to the hateful ideology of the enemy — by advancing liberty across a troubled region. It is in the interests of the United States to stand with the brave men and women who are risking their lives to claim their freedom and help them as they work to raise up just and hopeful societies across the Middle East.

From Afghanistan to Lebanon to the Palestinian Territories, millions of ordinary people are sick of the violence and want a future of peace and opportunity for their children. And they are looking at Iraq. They want to know: Will America withdraw and yield the future of that country to the extremists — or will we stand with the Iraqis who have made the choice for freedom?

The changes I have outlined tonight are aimed at ensuring the survival of a young democracy that is fighting for its life in a part of the world of enormous importance to American security. Let me be clear: The terrorists and insurgents in Iraq are without conscience, and they will make the year ahead bloody and violent. Even if our new strategy works exactly as planned, deadly acts of violence will continue — and we must expect more Iraqi and American casualties. The question is whether our new strategy will bring us closer to success. I believe that it will.

Victory will not look like the ones our fathers and grandfathers achieved. There will be no surrender ceremony on the deck of a battleship. But victory in Iraq will bring something new in the Arab world — a functioning democracy that polices its territory, upholds the rule of law, respects fundamental human liberties and answers to its people. A democratic Iraq will not be perfect. But it will be a country that fights terrorists instead of harboring them — and it will help bring a future of peace and security for our children and grandchildren.

Our new approach comes after consultations with Congress about the different courses we could take in Iraq. Many are concerned that the Iraqis are becoming too dependent on the United States — and therefore, our policy should focus on protecting Iraq's borders and hunting down al Qaeda. Their solution is to scale back America's efforts in Baghdad or announce the phased withdrawal of our combat forces. We carefully considered these proposals. And we concluded that to step back now would force a collapse of the Iraqi government, tear that country apart, and result in mass killings on an unimaginable scale. Such a scenario would result in our troops being forced to stay in Iraq even longer, and confront an enemy that is even more lethal. If we increase our support at this crucial moment, and help the Iraqis break the current cycle of violence, we can hasten the day our troops begin coming home.

In the days ahead, my national security team will fully brief Congress on our new strategy. If members have improvements that can be made, we will make them. If circumstances change, we will adjust. Honorable people have different views, and they will voice their criticisms. It is fair to hold our views up to scrutiny. And all involved have a responsibility to explain how the path they propose would be more likely to succeed.

Acting on the good advice of Sen. Joe Lieberman and other key members of Congress, we will form a new, bipartisan working group that will help us come together across party lines to win the war on terror. This group will meet regularly with me and my administration, and it will help strengthen our relationship with Congress. We can begin by working together to increase the size of the active Army and Marine Corps, so that America has the armed forces we need for the 21st century. We also need to examine ways to mobilize talented American civilians to deploy overseas — where they can help build democratic institutions in communities and nations recovering from war and tyranny.

In these dangerous times, the United States is blessed to have extraordinary and selfless men and women willing to step forward and defend us. These young Americans understand that our cause in Iraq is noble and necessary — and that the advance of freedom is the calling of our time. They serve far from their families, who make the quiet sacrifices of lonely holidays and empty chairs at the dinner table. They have watched their comrades give their lives to ensure our liberty. We mourn the loss of every fallen American, and we owe it to them to build a future worthy of their sacrifice.

Fellow citizens: The year ahead will demand more patience, sacrifice, and resolve. It can be tempting to think that America can put aside the burdens of freedom. Yet times of testing reveal the character of a nation. And throughout our history, Americans have always defied the pessimists and seen our faith in freedom redeemed. Now America is engaged in a new struggle that will set the course for a new century. We can and we will prevail.

More from CBS News

The Other Symbol of George W. Bush's Legacy

George W. Bush's library opened a week before the 10th anniversary of his 'Mission Accomplished' speech.

A Library Completed, a 'Mission Accomplished'

J. Scott Applewhite | AP

President Bush gives a "thumbs-up" sign after declaring the end of major combat in Iraq as he speaks aboard the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln off the California coast. (J. Scott Applewhite/AP)

Former President George W. Bush unveiled his presidential library April 25 to a beaming crowd of supporters. It was, as former President Bill Clinton called it, "the latest, grandest example of the eternal struggle of former presidents to rewrite history."

[ RELATED: Bush's $250M Presidential Center Second Only in Size to Reagan Library ]

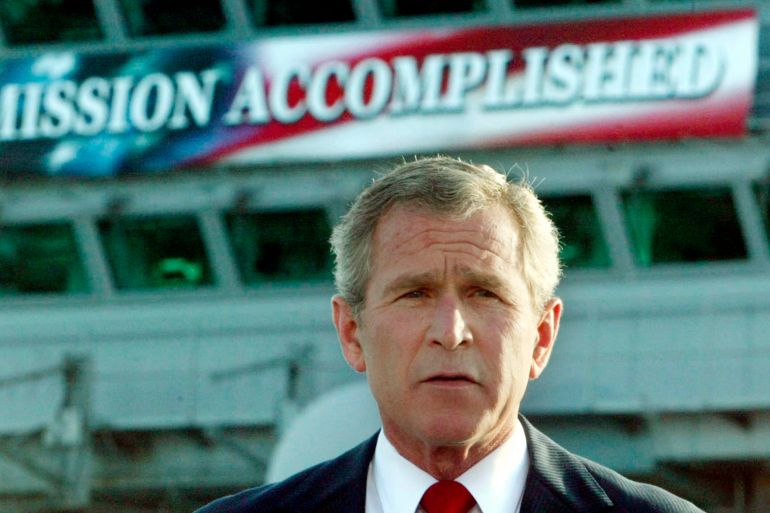

If there's one day in particular Bush could choose to rewrite, it might be May 1, 2003.

It was a sunny day off the coast of San Diego. Congress had authorized what would become the Iraq war a few months earlier, in October 2002. The invasion had begun in March 2003. On May 1, President Bush had landed on the USS Abraham Lincoln in the co-pilot's seat of a Navy fighter jet.

After landing, Bush changed out of his combat suit and stepped up to the podium, surrounded by a crowd as receptive as the one in Dallas last week.

Having marched U.S. troops through Iraq and deposed of Saddam Hussein's regime (and his statue), Bush called Operation Iraqi Freedom "a job well done."

[ RELATED: 10 Years Ago, the U.S. Invaded Iraq ]

"Major combat operations in Iraq have ended," Bush said , the infamous "Mission Accomplished" banner hovering over him. "In the battle of Iraq, the United States and our allies have prevailed."

At the time, the theatrics seemed effective, in the eyes of U.S. News. Democrats were disappointed, as Ken Walsh wrote, that the photo-op went so smoothly.

"The top gun cut a striking figure in his Top Gun duds, surrounded by admiring men and women in uniform—an image that's likely to turn up in Republican campaign advertising next year," he wrote.

[ READ: The Underestimated Costs, and Price Tag, of the Iraq War ]

Instead, the speech and the banner became a symbol of the unpopular war, which would last another eight brutal years. The image came to encapsulate not just the war, but the mistakes of the Bush administration as a whole, as even Bush himself admitted at his final press conference as president.

"Clearly, putting a 'mission accomplished' on an aircraft carrier was a mistake," Bush said, when asked about his errors while in the White House. "It sent the wrong message. We were trying to say something differently but, nevertheless, it conveyed a different message."

This article originally appeared in the May 12, 2003, issue of U.S. News & World Report.

The President on the Flight Deck

By Kenneth T. Walsh

President Bush's visit to the USS Abraham Lincoln last week had a movie-set feel reminiscent of those Clintonesque extravaganzas choreographed by the former president's Hollywood pals and Ronald Reagan's patriotic iconography. Rejecting the customary VIP helicopter, Bush swooped onto the aircraft carrier's deck in a Navy jet after taking the controls for a few minutes, then strutted in his green flight suit and aviator boots toward a swarm of welcoming sailors.

"In the battle of Iraq, the United States and our allies have prevailed," the commander in chief declared. "Because of you, our nation is more secure. Because of you, the tyrant has fallen and Iraq is free." Democrats fumed that Bush was diverting attention from the economy and getting a pass on his sketchy Air National Guard background. "We hoped that at least he'd look foolish getting out of the airplane," sighed a Democratic congressional aide. (Like that onetime Democratic presidential nominee looked tooling around in a tank?) No such luck. The top gun cut a striking figure in his Top Gun duds, surrounded by admiring men and women in uniform—an image that's likely to turn up in Republican campaign advertising next year.

- 6 Predictions Days Before the Iraq War

- After Iraq: How a Decade of War Shaped the U.S. Military

- Opinion: Bush Library Glides Over His Mistakes

Join the Conversation

Tags: history , George W. Bush , Iraq war (2003-2011)

America 2024

Health News Bulletin

Stay informed on the latest news on health and COVID-19 from the editors at U.S. News & World Report.

Sign in to manage your newsletters »

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

You May Also Like

The 10 worst presidents.

U.S. News Staff Feb. 23, 2024

Cartoons on President Donald Trump

Feb. 1, 2017, at 1:24 p.m.

Photos: Obama Behind the Scenes

April 8, 2022

Photos: Who Supports Joe Biden?

March 11, 2020

Trump Gives Johnson Vote of Confidence

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton April 12, 2024

U.S.: Threat From Iran ‘Very Credible’

Cecelia Smith-Schoenwalder April 12, 2024

Inflation Up, Consumer Sentiment Steady

Tim Smart April 12, 2024

House GOP Hands Johnson a Win

A Watershed Moment for America

Lauren Camera April 12, 2024

The Politically Charged Issue of EVs

- This Day In History

- History Classics

- HISTORY Podcasts

- HISTORY Vault

- Link HISTORY on facebook

- Link HISTORY on twitter

- Link HISTORY on youtube

- Link HISTORY on instagram

- Link HISTORY on tiktok

Speeches & Audio

George w. bush declares mission accomplished.

From aboard the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln on May 1, 2003, standing directly under a "Mission Accomplished" banner, President George W. Bush declares, "In the battle of Iraq, the United States and our allies have prevailed." Bush's claim of victory in what became known as the "Mission Accomplished" speech drew criticism as the war in Iraq continued for several years thereafter.

Create a Profile to Add this show to your list!

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Middle East

3 takeaways 20 years after the invasion of iraq.

Scott Neuman

Larry Kaplow

U.S. Marine Maj. Bull Gurfein pulls down a poster of Iraqi President Saddam Hussein on March 21, 2003, a day after the start of the U.S. invasion, in Safwan, Iraq. Chris Hondros/Getty Images hide caption

U.S. Marine Maj. Bull Gurfein pulls down a poster of Iraqi President Saddam Hussein on March 21, 2003, a day after the start of the U.S. invasion, in Safwan, Iraq.

Two decades ago, U.S. air and ground forces invaded Iraq in what then-President George W. Bush said was an effort to disarm the country, free its people and "defend the world from grave danger."

In the late-night Oval Office address on March 19, 2003, Bush did not mention his administration's assertion that Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction. That argument — which turned out to be based on thin or otherwise faulty intelligence — had been laid out weeks before by Secretary of State Colin Powell at a U.N. Security Council meeting.

U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell holds a vial representing the small amount of anthrax that closed the U.S. Senate in 2002 during his address to the U.N. Security Council on Feb. 5, 2003, in New York City. Powell was making a presentation attempting to convince the world that Iraq was deliberately hiding weapons of mass destruction. Mario Tama/Getty Images hide caption

U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell holds a vial representing the small amount of anthrax that closed the U.S. Senate in 2002 during his address to the U.N. Security Council on Feb. 5, 2003, in New York City. Powell was making a presentation attempting to convince the world that Iraq was deliberately hiding weapons of mass destruction.

Bush described the massive airstrikes on Iraq as the "opening stages of what will be a broad and concerted campaign" and pledged that "we will accept no outcome but victory."

20 years ago, the U.S. warned of Iraq's alleged 'weapons of mass destruction'

However, Bush's caveat that the campaign "could be longer and more difficult than some predict" proved prescient. In eight years of boots on the ground, the U.S. lost some 4,600 U.S. service members , and at least 270,000 Iraqis, mostly civilians, were killed. While the invasion succeeded in toppling Saddam, it ultimately failed to uncover any secret stash of weapons of mass destruction. Although estimates vary, a Brown University estimate puts the cost of the combat phase of the war at around $2 trillion.

When Ryan Crocker, who at the time had already been U.S. ambassador to Lebanon, Kuwait and Syria and would go on to hold the top diplomatic post in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan, first saw Bush's televised speech announcing the start of combat operations, he was at an airport heading back to Washington, D.C.

"I was thinking, 'Here we go,' " he recalls. But it was a sense of dread, not excitement. Crocker wondered, "God knows where we're going."

Peter Mansoor, a colonel attending the U.S. Army War College at the time, was concerned about his future, knowing that he'd soon be in command of the first brigade of the 1st Armored Division, which would go on to see action in Iraq.

"I was very interested in the outcome of the invasion and what would happen in the aftermath," says Mansoor, who is now a military history professor at Ohio State University. "I didn't expect the Iraqi army to be able to put up much resistance beyond a few weeks."

Meanwhile, Marsin Alshamary, an 11-year-old Iraqi American growing up in Minneapolis, Minn., when the invasion occurred, says "seeing planes and bombing over where my grandparents lived made me cry." Alshamary, who is now a Middle East policy expert at the Brookings Institution, says to her at the time, the possibility that Saddam would be deposed seemed "unreal."

Crocker, Mansoor and Alshamary recently shared their thoughts with NPR on lessons learned from one of America's longest conflicts — the war in Iraq. Here are their observations:

Wars aren't predictable. They're chaotic — and costlier than anyone anticipates

U.S. optimism for a quick and relatively bloodless outcome in Iraq was apparent even before the invasion.

In the months leading to the 2003 invasion, then-Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, in a radio call-in program , predicted that the coming fight would take "five days or five weeks or five months, but it certainly isn't going to last any longer than that." Bush, in what's been dubbed his "mission accomplished" speech on May 1, 2003, declared that "major combat operations in Iraq have ended."

Rumsfeld's prediction would prove hopelessly optimistic. In the days and weeks after Baghdad fell, a growing insurgency took root and U.S. forces began to come frequently under fire from hostile militias.

Mansoor says the Bush administration "made a certain set of planning assumptions that didn't pan out."

"They basically planned for a best-case scenario, where the Iraqi people would cooperate with the occupation, that Iraqi units would be available to help secure the country in the aftermath of conflict, and that the international community would step in to help reconstruct Iraq," he says. "All three of those assumptions were wrong."

Although many Iraqis were happy to see Saddam gone, "there was a significant minority who benefited from his rule. And they weren't going to go quietly into the night," Mansoor says.

That was not only the Iraqi army, but government bureaucrats who owed their livelihoods to Saddam.

15 Years After U.S. Invasion, Some Iraqis Are Nostalgic For Saddam Hussein Era

The U.S. decision to disband the Iraqi army a couple of months later — thus leaving 400,000 disgruntled and combat-trained Iraqi men with no income — proved a turning point in the conflict. It helped fuel the insurgency and is credited by some historians with having helped to spawn the Islamic State (ISIS) terrorist group.

Iraqi children sit amid the rubble of a street in Mosul's Nablus neighborhood in front of a billboard bearing the logo of the Islamic State group on March 12, 2017. Aris Messinis/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Iraqi children sit amid the rubble of a street in Mosul's Nablus neighborhood in front of a billboard bearing the logo of the Islamic State group on March 12, 2017.

"The Iraq conflict sucked thousands, if not tens of thousands, of jihadi terrorists into the country," Mansoor says. "It also created a battleground in Iraq where ... civil war could take place."

"None of this was foreseen," he says. "But the outcome of removing Saddam's regime enabled that."

Alshamary calls the Bush administration's approach to the Iraq invasion "outrageous."

"There has been no history of short, successful interventions that have resulted in successful regime change. So the arrogance of assuming that could happen was astounding," she says.

Instead of a conflict that lasted weeks or months, as Bush's Cabinet officials and advisers had hoped, a years-long occupation ensued that would be inherited by the administration of President Barack Obama. The word "quagmire" — largely disused since the Vietnam War — was dusted off to describe the situation in Iraq.

The potential for a protracted occupation should have been foreseen, says Crocker. "To overthrow someone else's government and occupy the country is going to set into motion consequences that aren't just third and fourth order. They're 30th and 40th order — way beyond any capacity to predict or plan."

"In Iraq, we paid for it in blood as well as money," the former ambassador says. "Somebody tell me when we decide if it was worth those 4,500 lives, not to mention the hundreds of thousands of lives that Iraqis lost."

If you set out to "reshape" a region, you may not like the shape it becomes

Key figures in the Bush administration believed that regime change would make Iraq a U.S. ally in the region and provide a pro-American bulwark against neighboring Iran, while reducing the threat of terrorism at home. Alshamary calls that notion, at least in relation to Iran, "wishful thinking."

Instead, she says, Tehran may have been the biggest beneficiary of the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Iran and Iraq fought a brutal eight-year conflict in the 1980s and were still bitter enemies at the start of the U.S. invasion. Today, the Iraqi army is just half its pre-invasion size. And s ome analysts argue that the Iraq War has made it much more difficult for the international community to respond to Iran's efforts to build nuclear weapons.

Instead of containing Tehran, the invasion of its neighbor and rival only "created a vacuum of power that Iran filled," Mansoor says.

It's a view shared by Crocker. "We basically left the field to adversaries with greater patience and more commitment," he says. "That would, of course, be al-Qaida to the west and Iran and its affiliated militias to the east."

The Islamic State also exploited sectarian tensions following the invasion to entrench itself in both Iraq and Syria, causing the U.S. to send troops back to Iraq three years after first withdrawing from the country.

The Two-Way

Obama: 275 troops will go to iraq as militants take ground.

A woman from an Arabic family cries after her family was denied entry to a Kurdish-controlled area from an ISIS-held village in late 2015 near Sinjar, Iraq. John Moore/Getty Images hide caption

A woman from an Arabic family cries after her family was denied entry to a Kurdish-controlled area from an ISIS-held village in late 2015 near Sinjar, Iraq.

Not all outcomes are bad

Despite the huge loss of life and the other consequences from the U.S. invasion, Alshamary, Mansoor and Crocker agree that Iraq is a fundamentally freer country today than it was before 2003.

Yes, there's crippling corruption , unemployment , poverty and a complete reliance on oil as a source of wealth , Alshamary says. On the other hand, Iraq has elections "that aren't perfectly free and fair but are actually a lot better than people think they are."

Iraqi protesters helped spur new elections. But many doubt their votes will matter

Even so, attacks on activists and journalists are not uncommon. Recent street protests have been forcefully quashed by authorities. Two years ago, Iraq's prime minister narrowly survived an assassination attempt , allegedly by an Iranian-backed militia group.

Despite these problems, Iraq has held together. It's a democracy with peaceful transitions of power — things that wouldn't exist without the U.S. intervention, Mansoor says.

Meanwhile, Crocker points to a recent visit to Iraq, where he met with a group of recent university graduates. What was Iraq's biggest problem? he asked.

"Corruption," was the answer. "And it starts at the top, including the PM."

"I noted they were saying this in the PM's guest house," he says.

- 20th anniversary Iraq War

- Islamic State

- Iraq and U.S.

- George W. Bush

.css-1d0dlne-HeadlineTextBlock >*{display:inline-block;} .css-1plpptc-HeadlineTextBlock{margin:0;color:rgba(255,255,255,1);font-family:Escrow Condensed,Georgia,serif;font-size:36px;line-height:40px;font-weight:700;letter-spacing:0px;font-style:normal;text-transform:none;font-stretch:normal;padding:0.5px 0px;}.css-1plpptc-HeadlineTextBlock svg{fill:rgba(255,255,255,1);}.css-1plpptc-HeadlineTextBlock::before{content:'';margin-bottom:-0.2266em;display:block;}.css-1plpptc-HeadlineTextBlock::after{content:'';margin-top:-0.1956em;display:block;}.css-1plpptc-HeadlineTextBlock >*{display:inline-block;} The Iraq War: George W. Bush's Speech 10 Years Later

The Iraq War began 10 years ago on March 19, 2003. In this video, President George W. Bush makes his case for war.

Wall Street Journal

March 19, 2013

Editor Picks

View all .css-yin81f{display:inline-block;position:relative;top:2px;} .css-ocvtgk{fill:rgba(244,244,244,1);vertical-align:unset;display:inline-block;}@media screen and (prefers-reduced-motion: no-preference){.css-ocvtgk{transition-property:fill;transition-duration:200ms;transition-timing-function:cubic-bezier(0, 0, .5, 1);}}@media screen and (prefers-reduced-motion: reduce){.css-ocvtgk{transition-property:fill;transition-duration:0ms;transition-timing-function:cubic-bezier(0, 0, .5, 1);}}, most popular, politics & campaign, life & culture, at barron's, marketwatch, moneyish and barron's.

Help inform the discussion

Presidential Speeches

August 8, 1990: address on iraq's invasion of kuwait, about this speech.

George H. W. Bush

August 08, 1990

- Download Full Video

- Download Audio

In the life of a nation, we're called upon to define who we are and what we believe. Sometimes these choices are not easy. But today as President, I ask for your support in a decision I've made to stand up for what's right and condemn what's wrong, all in the cause of peace.

At my direction, elements of the 82d Airborne Division as well as key units of the United States Air Force are arriving today to take up defensive positions in Saudi Arabia. I took this action to assist the Saudi Arabian Government in the defense of its homeland. No one commits America's Armed Forces to a dangerous mission lightly, but after perhaps unparalleled international consultation and exhausting every alternative, it became necessary to take this action. Let me tell you why.

Less than a week ago, in the early morning hours of August 2d, Iraqi Armed Forces, without provocation or warning, invaded a peaceful Kuwait. Facing negligible resistance from its much smaller neighbor, Iraq's tanks stormed in blitzkrieg fashion through Kuwait in a few short hours. With more than 100,000 troops, along with tanks, artillery, and surface-to-surface missiles, Iraq now occupies Kuwait. This aggression came just hours after Saddam Hussein specifically assured numerous countries in the area that there would be no invasion. There is no justification whatsoever for this outrageous and brutal act of aggression.

A puppet regime imposed from the outside is unacceptable. The acquisition of territory by force is unacceptable. No one, friend or foe, should doubt our desire for peace; and no one should underestimate our determination to confront aggression.

Four simple principles guide our policy. First, we seek the immediate, unconditional, and complete withdrawal of all Iraqi forces from Kuwait. Second, Kuwait's legitimate government must be restored to replace the puppet regime. And third, my administration, as has been the case with every President from President Roosevelt to President Reagan, is committed to the security and stability of the Persian Gulf. And fourth, I am determined to protect the lives of American citizens abroad.

Immediately after the Iraqi invasion, I ordered an embargo of all trade with Iraq and, together with many other nations, announced sanctions that both freeze all Iraqi assets in this country and protected Kuwait's assets. The stakes are high. Iraq is already a rich and powerful country that possesses the world's second largest reserves of oil and over a million men under arms. It's the fourth largest military in the world. Our country now imports nearly half the oil it consumes and could face a major threat to its economic independence. Much of the world is even more dependent upon imported oil and is even more vulnerable to Iraqi threats.

We succeeded in the struggle for freedom in Europe because we and our allies remain stalwart. Keeping the peace in the Middle East will require no less. We're beginning a new era. This new era can be full of promise, an age of freedom, a time of peace for all peoples. But if history teaches us anything, it is that we must resist aggression or it will destroy our freedoms. Appeasement does not work. As was the case in the 1930's, we see in Saddam Hussein an aggressive dictator threatening his neighbors. Only 14 days ago, Saddam Hussein promised his friends he would not invade Kuwait. And 4 days ago, he promised the world he would withdraw. And twice we have seen what his promises mean: His promises mean nothing.

In the last few days, I've spoken with political leaders from the Middle East, Europe, Asia, and the Americas; and I've met with Prime Minister Thatcher, Prime Minister Mulroney, and NATO Secretary General Woerner. And all agree that Iraq cannot be allowed to benefit from its invasion of Kuwait.

We agree that this is not an American problem or a European problem or a Middle East problem: It is the world's problem. And that's why, soon after the Iraqi invasion, the United Nations Security Council, without dissent, condemned Iraq, calling for the immediate and unconditional withdrawal of its troops from Kuwait. The Arab world, through both the Arab League and the Gulf Cooperation Council, courageously announced its opposition to Iraqi aggression. Japan, the United Kingdom, and France, and other governments around the world have imposed severe sanctions. The Soviet Union and China ended all arms sales to Iraq.

And this past Monday, the United Nations Security Council approved for the first time in 23 years mandatory sanctions under chapter VII of the United Nations Charter. These sanctions, now enshrined in international law, have the potential to deny Iraq the fruits of aggression while sharply limiting its ability to either import or export anything of value, especially oil.

I pledge here today that the United States will do its part to see that these sanctions are effective and to induce Iraq to withdraw without delay from Kuwait.

But we must recognize that Iraq may not stop using force to advance its ambitions. Iraq has massed an enormous war machine on the Saudi border capable of initiating hostilities with little or no additional preparation. Given the Iraqi government's history of aggression against its own citizens as well as its neighbors, to assume Iraq will not attack again would be unwise and unrealistic.

And therefore, after consulting with King Fahd, I sent Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney to discuss cooperative measures we could take. Following those meetings, the Saudi Government requested our help, and I responded to that request by ordering U.S. air and ground forces to deploy to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Let me be clear: The sovereign independence of Saudi Arabia is of vital interest to the United States. This decision, which I shared with the congressional leadership, grows out of the longstanding friendship and security relationship between the United States and Saudi Arabia. U.S. forces will work together with those of Saudi Arabia and other nations to preserve the integrity of Saudi Arabia and to deter further Iraqi aggression. Through their presence, as well as through training and exercises, these multinational forces will enhance the overall capability of Saudi Armed Forces to defend the Kingdom.

I want to be clear about what we are doing and why. America does not seek conflict, nor do we seek to chart the destiny of other nations. But America will stand by her friends. The mission of our troops is wholly defensive. Hopefully, they will not be needed long. They will not initiate hostilities, but they will defend themselves, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and other friends in the Persian Gulf.

We are working around the clock to deter Iraqi aggression and to enforce U.N. sanctions. I'm continuing my conversations with world leaders. Secretary of Defense Cheney has just returned from valuable consultations with President Mubarak of Egypt and King Hassan of Morocco. Secretary of State Baker has consulted with his counterparts in many nations, including the Soviet Union, and today he heads for Europe to consult with President Ozal of Turkey, a staunch friend of the United States. And he'll then consult with the NATO Foreign Ministers.

I will ask oil-producing nations to do what they can to increase production in order to minimize any impact that oil flow reductions will have on the world economy. And I will explore whether we and our allies should draw down our strategic petroleum reserves. Conservation measures can also help; Americans everywhere must do their part. And one more thing: I'm asking the oil companies to do their fair share. They should show restraint and not abuse today's uncertainties to raise prices.

Standing up for our principles will not come easy. It may take time and possibly cost a great deal. But we are asking no more of anyone than of the brave young men and women of our Armed Forces and their families. And I ask that in the churches around the country prayers be said for those who are committed to protect and defend America's interests.

Standing up for our principle is an American tradition. As it has so many times before, it may take time and tremendous effort, but most of all, it will take unity of purpose. As I've witnessed throughout my life in both war and peace, America has never wavered when her purpose is driven by principle. And in this August day, at home and abroad, I know she will do no less.

Thank you, and God bless the United States of America.

More George H. W. Bush speeches

What Really Took America to War in Iraq

A fatal combination of fear, power, and hubris

A t the Pentagon on the afternoon of 9/11, as the fires still burned and ambulances blared, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld returned from the smoke-filled courtyard to his office. His closest aide, Undersecretary Stephen Cambone, cryptically recorded the secretary’s thinking about Saddam Hussein and Osama (or Usama) bin Laden: “Hit S. H. @same time; Not only UBL; near term target needs—go massive—sweep it all up—need to do so to hit anything useful.”

The president did not agree. That night, when George W. Bush returned to Washington, his main concern was reassuring the nation, relieving its suffering, and inspiring hope. Informed that al-Qaeda was most likely responsible for the attack, he did not focus on Iraq. The next day, at meetings of the National Security Council, Rumsfeld and Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz advocated action against Saddam Hussein. With no good targets in Afghanistan and no war plans to dislodge the Taliban, Defense officials thought Iraq might offer the best opportunity to demonstrate American resolve and resilience. Their arguments did not resonate with anyone present.

The following evening, however, President Bush encountered his outgoing counterterrorism expert, Richard Clarke, and several other aides outside the Situation Room in the White House. According to Clarke, the president said , “I want you, as soon as you can, to go back over everything, everything. See if Saddam did this. See if he’s linked in any way.” Clarke promised he would but insisted that al-Qaeda, not Hussein, was responsible. Then he muttered to his assistants, “Wolfowitz got to him.”

There is no real evidence that Wolfowitz did get to Bush. The president may have talked about attacking Iraq in a conversation with British Prime Minister Tony Blair on Friday, September 14. But when Wolfowitz raised the issue again at Camp David over the weekend, Bush made it clear that he did not think Hussein was linked to 9/11, and that Afghanistan was priority No. 1. His vice president, national security advisers, and CIA director were all in agreement.

From the January/February 209 issue: The George W. Bush years

Bush’s decision to invade Iraq was neither preconceived nor inevitable. It wasn’t about democracy, and it wasn’t about oil. It wasn’t about rectifying the decision of 1991, when the United States failed to overthrow Hussein, nor was it about getting even for the dictator’s attempt to assassinate Bush’s father, George H. W. Bush, in 1993. Rather, Bush and his advisers were motivated by their concerns with U.S. security. They urgently wanted to thwart any other possible attack on Americans, and they were determined to foreclose Hussein’s ability to use weapons of mass destruction to check the future exercise of American power in the Middle East.

Bush resolved to invade Iraq only after many months of high anxiety, a period in which hard-working, if overzealous, officials tried to parse intelligence that was incomplete and unreliable. Their excessive fear of Iraq was matched by an excessive preoccupation with American power. And they were unnerved, after 9/11’s shocking revelation of an unimagined vulnerability, by a sense that the nation’s credibility was eroding.

I n Bush’s key speeches during the first week after 9/11, he did not dwell on Iraq. When reporters asked the president if he had a special message for Saddam Hussein, Bush spoke generically: “Anybody who harbors terrorists needs to fear the United States … The message to every country is, there will be a campaign against terrorist activity, a worldwide campaign.” When General Tommy Franks, the commander of U.S. forces in the Middle East, suggested to Bush that they begin military planning against Iraq, the president instructed him not to.

Rumsfeld and his top advisers remained more concerned about Iraq—a regime, wrote Undersecretary of Defense Douglas Feith on September 18, “that engages in and supports terrorism and otherwise threatens US vital interests.” But even they weren’t advocating a full-scale invasion. Instead, Wolfowitz favored seeding a Shia rebellion in the south, establishing an enclave or a liberation zone for organizing a provisional government, and denying Hussein control over the region’s oil. “If we’re capable of mounting an Afghan resistance against the Soviets,” Wolfowitz told me, “we could have been capable of mounting an Arab resistance.”

Bush was not entirely unsympathetic to this approach, but neither Rumsfeld nor Wolfowitz could persuade him to divert his attention from Afghanistan and the broader War on Terror. Wolfowitz deferred to Bush’s priority, ultimately helping devise the strategy that toppled the Taliban in Afghanistan. But he, Feith, and their civilian colleagues at the Pentagon did not relinquish the idea of regime change in Iraq. They were incensed by Hussein’s gloating over the 9/11 attack. And they were convinced that he was dangerous.

Bush’s attention did not gravitate to Iraq until the fall, after anthrax spores circulated through the U.S. mail, killing several postal workers, and turned up in a Senate office building and at a facility handling White House mail. On October 18, sensors inside the White House alerted staff to the presence of a deadly toxin; it was a false alarm, but one that intensified worries about an attack with biological or chemical weapons.

Bush and his advisers were troubled by what they thought they knew about Iraq, though assessing Hussein’s intentions and capabilities was difficult. The Iraqi dictator had expelled international inspectors in 1998, leaving the CIA unable to collect information. But analysts were convinced that Hussein could not be trusted to have destroyed all of the weapons of mass destruction he’d previously possessed. Their suspicions were reinforced when an Iraqi defector claimed that Iraq had established mobile biological-weapons-production plants and now possessed “capabilities surpassing the pre–Gulf War era.”

From the January/February 2004 issue: Spies, lies, and weapons: what went wrong

Michael Morell, the president’s CIA briefer, insisted to me that someone reexamining the available evidence at the time would still conclude that Hussein “had a chemical-weapons capability, that he had chemical weapons stockpiled, that he had a biological-weapons-production capability, and he was restarting a nuclear program. Today you would come to that judgment based on what was on that table.” But what was on the table, Morell told me, was circumstantial and suspect, much of it coming from Iraqi Kurdish foes of the regime. Morell acknowledged that he should have said, “Mr. President, here is what we think … But what you really need to know is that we have low confidence in that judgment and here is why.” Instead, Morell was telling the president that Hussein “had a chemical-weapons program. He’s got a biological-weapons-production capability.”

Bush and his top advisers were predisposed to think that Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. This was true not only of the hawks in the administration. Secretary of State Colin Powell and National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice believed that Hussein possessed WMDs. So did State Department analysts and their counterparts in the CIA and at the National Security Agency. They disagreed about the purpose of aluminum tubes and about Iraq’s acquisition of uranium yellowcake, and they were aware that Hussein would need five to seven years to develop a nuclear weapon once the regime began working on it again. Nevertheless, they thought they knew that Iraq had biological and chemical weapons, or could develop them quickly, and that Hussein aspired to reconstitute a nuclear program.

Foreign-intelligence partners concurred. Tony Blair and his most trusted advisers felt the same way. Nobody told Bush that Hussein did not have WMDs.

Hussein had been seriously hampered by sanctions and the presence of inspectors. But now the inspectors were gone, and the sanctions were disappearing. The conundrum facing U.S. policy makers was how to contain Hussein if the sanctions regime ended and if United Nations monitors did not return. “I wasn’t worried about what he would do in 2001,” Wolfowitz told me. “I was worried about what he would do in 2010 if the existing containment … collapsed.”

Hussein was not doing much to allay American fears. He was using his oil revenues to leverage support from France, China, and Russia to end UN sanctions. He had not ceased providing support for terrorist activity in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, some of which targeted American aid workers. And reports of his pervasive repressions inside Iraq persisted.

Read: Britain’s Iraq war reckoning

At the same time, Hussein was investing his growing financial reserves in strengthening Iraq’s military-industrial complex and acquiring materials that could be used for chemical and biological weapons. According to British intelligence, the Iraqis were still concealing information about 31,000 chemical munitions, 4,000 tons of chemicals that could be used for weapons, and large quantities of material that could be employed for the production of biological weapons.

Such assessments held through the winter. “Iraq continues to pursue its WMD programmes,” concluded the British Joint Intelligence Committee in February 2002. “If it has not already done so, Iraq could produce significant quantities of biological warfare agents within days and chemical warfare agents within weeks of a decision to do so.”

“I have no doubt we need to deal with Saddam,” Blair had written to Bush in the fall of 2001. But if we “hit Iraq now,” Blair had warned, “we would lose the Arab world, Russia, probably half the EU and my fear is the impact on Pakistan.” Far better to deliberate quietly and avoid public debate “until we know exactly what we want to do; and how we can do it.” Bush agreed.

“P resident Bush believed ,” Rumsfeld subsequently wrote, “that the key to successful diplomacy with Saddam was a credible threat of military action. We hoped that the process of moving an increasing number of American forces into a position where they could attack Iraq might convince the Iraqis to end their defiance.” As Stephen Hadley, the deputy national security adviser during Bush’s first term, told me: “We thought it would coerce him … to do what the international community asked, which is either destroy the WMD or show us that you destroyed it. That was it. Either do it or, if you’ve already done it, show it, prove it.”

Bush wanted to use the threat of force to resume inspections and gain confidence that Iraq did not possess WMDs that might fall into the hands of terrorists or be used to blackmail the U.S. in the future. But he also wanted to use the threat of force to remove Hussein from power. He did not really know which of these goals had priority. He never clearly sorted out these overlapping yet conflicting impulses, even as each seemed to become more compelling.

“The best way to get Saddam to come into compliance with UN demands,” wrote Cheney in his memoir, In My Time , “was to convince him we would use force.” Prominent Democrats did not disagree. In early February 2002, Senator Joseph Biden, the Democratic chair of the Foreign Relations Committee, held hearings dealing with the State Department’s request for the 2003 budget. Secretary Powell emphasized that the War on Terror was his No. 1 priority. There were regimes, Powell said, that not only supported terror but were developing WMDs. They “could provide the wherewithal to terrorist organizations to use these sorts of things against us.”

Biden asked whether this meant that the president was announcing a new policy of preemption, as foreign allies thought he was doing. After Powell denied this allegation, Biden proclaimed his own fears about the proliferation of WMDs, especially in Iraq. “I happen to be one that thinks that one way or another Saddam has got to go and it is likely to be required to have U.S. force to have him go,” he said. “The question is how to do it, in my view, not if to do it.”

Intelligence reports over the following months did not ease Bush’s anxieties. What alarmed the president was new information that al-Qaeda was seeking biological and chemical weapons, alongside the knowledge that Iraq had had them and used them.

In late May 2002, analysts reported that al-Qaeda operatives were moving into Baghdad, including the high-ranking jihadist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi . “Other individuals associated with al-Qaida,” the head of the State Department’s intelligence office informed Powell, “are operating in Baghdad and are in contact with colleagues who, in turn, may be more directly involved in attack planning.” Since 9/11, there had been little al-Qaeda activity in Iraq, and experts disagreed about the nature of the relationship between the Iraqi dictator and Osama bin Laden. Hardly anyone thought Iraq had anything to do with 9/11, but, according to a postwar Senate investigation, there were “a dozen or so reports of varying reliability mentioning the involvement of Iraq or Iraqi nationals in al-Qa’ida’s efforts to obtain” chemical- and biological-warfare training.

From the July/August 2006 issue: The short, violent life of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi

Al-Zarqawi was a known terrorist, a Jordanian who had fought in Afghanistan, met with bin Laden, and managed his own training camps in Herat. Already notorious for his toughness, radicalism, and barbarity, he lusted to wreak revenge on Americans. Reports of al-Zarqawi’s presence in Iraq came shortly before U.S. policy makers received information about an Iraqi procurement agent’s activity in Australia. Allegedly, this agent was seeking to buy GPS software that would allow the regime to map American cities. Might the Iraqi dictator be plotting a WMD attack inside the United States?

Al-Zarqawi was also collaborating with Ansar al-Islam, an Islamist extremist group that was battling a mainline Kurdish party for control of northeastern Iraq. A small CIA team had infiltrated the region near the city of Khurmal and reported in July that al-Zarqawi had begun experimenting with biological and chemical agents that terrorists could put in ventilation systems. According to one of the CIA agents, “they were full-bore on biological and chemical warfare … They were doing a lot of testing on donkeys, rabbits, mice, and other animals.”

In Washington, the Joint Chiefs of Staff favored military action in Khurmal. So did Cheney, Rumsfeld, and Wolfowitz. They did not believe that al-Qaeda would be in Iraq—even a part not controlled by Hussein—without the dictator’s acquiescence. Their suspicions grew when information placed al-Zarqawi and other al-Qaeda fighters in Baghdad. The CIA agents in Iraq saw no evidence that the al-Qaeda operatives were linked to Hussein, but everyone they spoke with believed that Hussein had WMDs.

Bush said he would act with “deliberation,” employing only the best intelligence. But the intelligence was murky, leading to contentious assessments, conflicting judgments, and uncertain recommendations. Sometimes, the president overstated the evidence he had. Hussein’s a threat, Bush told the press corps in November 2002, “because he is dealing with al-Qaeda.” Although this was an exaggeration, Bush did know that al-Zarqawi had been in Baghdad, had links to al-Qaeda, and was experimenting with biological and chemical weapons. And he knew that Hussein supported suicide bombings and celebrated their “martyrs.”