- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Health Education Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, rationale for theory-comparison research, rationale for multiple-behavior research, common themes in theory-comparison and multiple-behavior research of the nih’s bcc.

- < Previous

Theory-comparison and multiple-behavior research: common themes advancing health behavior research

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Claudio R. Nigg, John P. Allegrante, Marcia Ory, Theory-comparison and multiple-behavior research: common themes advancing health behavior research, Health Education Research , Volume 17, Issue 5, October 2002, Pages 670–679, https://doi.org/10.1093/her/17.5.670

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Research that seeks to compare and contrast theories of behavior change and assess the utility of a particular theoretical model for changing two or more health-related behaviors is critical to advancing health behavior research. Theory-comparison can help us learn more about the processes by which people change and maintain health behaviors than does study of any single theory alone and thus has the potential to better guide the development of intervention. Multiple-behavior interventions promise to have much greater impact on public health than single-behavior interventions. However, theory-comparison and multiple-behavior research presents several emerging challenges. These include finding new ways to enhance recruitment and retention, especially among diverse populations; improving treatment fidelity; developing common metrics across behaviors that can be used to advance the measurement and assessment of behavioral change; and expanding the reach and translation of intervention approaches that have demonstrated efficacy. This paper discusses the rationale for conducting theory-comparison and multiple-behavior research and presents several common themes that have emerged from the work of the National Institutes of Health Behavior Change Consortium (BCC). The activities of each BCC workgroup and the potential contribution of each to these common themes to advance health behavior research are also described.

The Behavior Change Consortium (BCC), sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the American Heart Association and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, was initiated to support a new generation of research on innovative approaches to disease prevention through behavior change ( Ory et al ., 2002a ). The goal of this initiative has been to stimulate the investigation of innovative strategies designed to initiate and maintain changes in health behaviors.

In addition to demonstrating the efficacy of a single theory or single behavior change program, the intervention studies of the BCC also provide a unique opportunity to compare theories of behavior change and assess the utility of a particular theoretical model for changing two or more health-related behaviors. The collective work of the BCC is oriented toward identifying common theoretical and methodologic themes of interest to advancing health behavior research. This paper discusses the rationale for conducting theory-comparison and multiple-behavior research, and presents several common themes that have emerged from the work of the BCC and its workgroups.

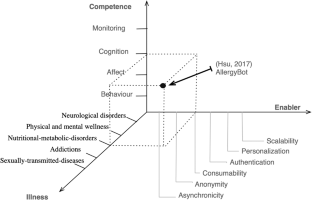

Research on theory-based intervention in changing health behavior has increased dramatically ( Smedley and Syme, 2000 ). Most of the research has focused on studying the explanatory and predictive validity of individual theories, including the Health Belief Model ( Rosenstock, 1966 ; Becker, 1974 ), Self-Determination Theory ( Deci and Ryan, 1980 ), Social Cognitive Theory ( Bandura, 1977 ), Theory of Reasoned Action/Planned Behavior ( Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980 ; Ajzen and Madden, 1986 ) and the Transtheoretical Model ( Prochaska et al ., 1992 ), among others. Indeed, these theories have formed the familiar dialectic of the theoretical perspective that has dominated the field of research in health behavior ( Allegrante and Roizen, 1998 ).

These theories can be categorized as belief-attitude theories, competence-based theories, control-based theories and decision-making theories [e.g. ( Biddle and Nigg, 2000 )]. The emphasis of most of these theories is on understanding the cognitive psychology of the individual, either alone or within the context of the individual’s social environment, and from the point of view of several key constructs (i.e. motivation, intentions and behavior). Such theories reflect a long-standing preoccupation with psychological and social-psychological factors that have been shown to be critically necessary although not sufficient ‘determinants’ of health behavior ( Sallis and Owen, 1999 ).

Broader approaches to understanding health behavior have emerged and are increasingly pursued in health promotion and health behavior change research. These include ecological models [e.g. ( McLeroy et al ., 1988 ; Green and Kreuter, 1999 )] and community models of intervention [e.g. ( Minkler and Wallerstein, 1997 )], where individual psychology comprises but one element of the broader social and environmental context in which health behavior is determined. For example, large-scale studies of population-wide cardiovascular risk reduction conducted at Minnesota ( Luepker et al ., 1995 ), Stanford ( Farquhar et al ., 1990 ) and Pawtucket ( Carleton et al ., 1995 ), supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, were among the first generation of studies to synthesize these broader theoretical perspectives in the design of community intervention programs. While such perspectives have demonstrated differential utility in explaining modest percentages of variance across different behaviors and populations, they have proved useful in providing a more general understanding of the process of health behavior change at both individual and community levels.

Intervention approaches have since been expanded to include advocating for policy changes. Policy approaches have been applied to several studies of health behavior change, including those directed at smoking cessation, increasing physical activity, and improving diet and nutrition ( International Longevity Center, 1999 ); however, research with ecologic and community models of health behavior has sought to study the theories singly, not in comparison.

Comparing and contrasting theories can be fruitful for several reasons. First, as Maddux has suggested, it is counterproductive to hold statistical horse races to see what theory brings about more behavior change and discard the ‘loser’ ( Maddux, 1993 ). Theory-comparison research may help behavioral and social scientists engaged in health behavior research to avoid Marsh’s concept of the ‘jingle-jangle’ fallacy ( Marsh, 1994 ). Theory comparison can inform if the same constructs are being addressed but labeled differently (jingle) or if the theories operationalize the same construct differently (jangle). Moreover, studying multiple theories simultaneously allows for empirically driven integration of theories and may lead to the construction of a more complete or holistic theory of health behavior change than currently exists.

Second, theory comparison can help us learn more about the behavior change process than does study of any theory in isolation and thus better guide intervention development. While one theory may contribute to our understanding of how best to motivate an individual to adopt a new health behavior, another theory may contribute to our understanding of how an individual maintains that behavior change over time. In addition, moderators (e.g. minority status and age) may differentially influence the effectiveness of theories. Moreover, while a particular theory may be appropriate if the disease of interest is proximal, a different theory may prove useful to elicit the desired behavior if the disease to which it is relevant is temporally removed.

Finally, comparing and contrasting theories may help us to understand that some behavior change and the observed variance in change cannot be explained at all by existing theories, perhaps necessitating the development of entirely new theories, and the identification of new variables and novel measurement strategies.

Regardless of the aims, theory-based research will improve our understanding of the health behavior change process. Theory-based research allows for: (1) an understanding of the mechanism of behavior change involved, (2) an understanding of the underlying reasoning of why the mechanism worked or failed, (3) identification of what mediators of behavior an intervention should target and (4) the design of evaluations that can determine why an intervention was (or was not) successful (i.e. process to outcome analyses).

Smoking, high-fat diet and physical inactivity are three behaviors underlying the most preventable causes of disease and death in the US ( National Center for Health Statistics, 1997 ) and are three of the top five priorities of Healthy People 2010 ( US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000 ). In 1997, an international panel of cancer experts concluded that as many as 30–40% of all cancer cases worldwide could be avoided if people ate a healthy diet, avoided obesity and got enough exercise ( Hellmich, 1997 ). Although multiple risk factors are associated with a heightened risk of morbidity and mortality, the majority of health promotion interventions address risk factors as categorically separate entities, with the exception of obesity and diabetes interventions. Yet we know that health behaviors often cluster. For example, in a sample of 1559 manufacturing workers, 46% of smokers had two other risk factors (diet and inactivity) compared to 28% of non-smokers ( Emmons et al ., 1994 ). Further, the rate of heart attack increases from 46 per 1000 persons at risk with one risk factor (smoking) to 95 per 1000 persons at risk for a combination of three risk factors [smoking, hypertension and hyperlipidemia ( American Heart Association, 1997 )]. Thus, a potentially more effective paradigm may be to target multiple behaviors by developing intervention approaches that integrate what we have learned from modular approaches in order to focus on behavior-change issues common or generic to several risk behaviors. The critical questions of interest are: Is it valuable to work on multiple behaviors simultaneously or should one behavior be addressed at a time? What are the key behavioral constructs and processes common to these problem behaviors? How do multiple behaviors interact to increase or decrease health risks?

There is growing evidence that multiple-behavior interventions have the potential for much greater impact on public health than single-behavior interventions. The risk of cardiovascular disease can be lowered by 50–70% when people quit smoking and by 45% by maintaining a physically active lifestyle ( Manson et al ., 1993 ). If intervening on a single behavior can yield such significant improvements in public health, the natural extension of such a corollary is that intervening on multiple behaviors has the potential to greatly increase the impact of the intervention on public health across different diseases. Furthermore, changing multiple health behaviors should result in more favorable benefits measured in terms of quality of life outcomes and health care utilization. Given the growing interest in developing effective theory to both understand and intervene on multiple health behaviors, surprisingly little is known about what is the most effective way to intervene on multiple behaviors ( Smedley and Syme, 2000 ; Emmons, 2001 ).

For example, regular physical activity aids in decreasing both physiological and psychological responses to stress and helps reduce depression, which often accompanies smoking cessation ( Hughes, 1984 ; Holmes and Roth, 1988 ). Preliminary studies have demonstrated the utility of physical activity in enhancing quit rates and decreasing the likelihood of relapse following smoking cessation ( Marcus et al ., 1991 , 1995 ). Physical activity also results in increased caloric expenditure, which may lessen the post-smoking cessation weight gain that often leads to relapse ( Hall et al ., 1989 ; Klesges et al ., 1991 ). There is also some evidence that adopting physical activity leads to dietary changes ( Kano and Tucker, 1993 ). For example, physical activity is not only inversely related to fat intake, it seems to act as a mild appetite suppressant, at least for the first few hours following exercise training ( Wilmore and Costill, 1994 ). Finally, in a study of the cognitive-behavioral mediators of changing multiple behaviors in smokers, King et al . found significant relationships in decisional balance and self-efficacy between smoking and physical activity ( King et al ., 1996 ). This study provided preliminary cross-sectional data on how change in one risk behavior (smoking) may relate to change in another (physical inactivity).

Despite such intriguing evidence, it is currently unknown whether treating more behaviors is more or less effective than treating fewer behaviors and, if so, why. Treating multiple behaviors may have a positive effect due to the multiple exposures to the principles of behavior change. Conversely, treating multiple behaviors may be less effective due to the increased response burden produced by trying to change several behaviors at once. Moreover, there may be a maximum number or hierarchy of order of behaviors that individuals can better cope with trying to change at any given time and with different incentives. Understanding the best ways to change multiple risk behaviors and what motivates those changes is essential for designing effective intervention programs at both the individual and population levels.

The impact of an intervention is partly determined by the percent of the target population recruited and the efficacy of the intervention, i.e. intervention impact = recruitment×efficacy ( Abrams et al ., 1994 ). Recently, another dimension of intervention impact, retention , has been added to this equation, i.e. intervention impact = recruitment×retention×efficacy ( Marcus et al ., 2000 ). This equation could be expanded to assess the impact of multiple-behavior interventions, i.e. intervention impact = recruitment ×retention×mean efficacy×number of behaviors (the mean efficacy may be each behavior’s effect size multiplied by a coefficient derived from the contribution to all cause mortality, which is then averaged for behaviors addressed). In addition to evaluating a summary estimate of behavioral change, projected reductions in morbidity and mortality will inform public health impact and decision making ( Woolf, 1999 ).

Developing integrated intervention approaches that can take advantage of the data pointing to the synergy that exists between multiple health behaviors and what is known about the impact of intervention, however, will require a better understanding of what behaviors are the most difficult to change and maintain, why and how these behaviors can be best used as examples. In addition, further research is required to better understand the relationship of dose to response ( Steckler et al ., 1995 ), i.e. whether intervention dosing based on one theory is equivalent to intervention dosing based on another theory and, related, if intervention dosing based on one behavior is equivalent to dosing of a different behavior.

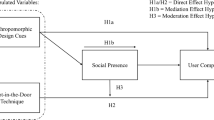

The BCC has endeavored to support cross-site collaborations that are designed to begin answering such questions by supporting theory-comparison and multiple-behavior research. BCC workgroups are engaged in activities on several common themes in theory-comparison and multiple-behavior research (Figure 1 ). These include recruitment and retention, treatment fidelity, measurement and assessment, and reach and translation.

Recruitment and retention

A critical issue in advancing the next generation of health behavior research is conducting representative recruitment and implementing strategic retention plans, especially among underserved populations. While there is a basic understanding that meeting recruitment goals is critical for the scientific integrity of the proposed research, until recently this has been seen as an administrative problem rather than as an area of scientific inquiry ( Ory et al ., 2002b ). Similarly, there is a lack of information on the factors associated with preventing attrition, particularly among underserved populations. There is an urgent need for systematic, empirical research that compares the effectiveness of different approaches to recruitment and retention; that examines the factors and conditions that maximize recruitment and retention; and that assesses various methods most sensitive to the needs of ethnic and racial minorities. Such studies need to consider the recruitment and retention complexities in the context of an increasingly urban, multi-ethnic and multi-racial society ( Levkoff et al ., 2000 ).

To evaluate the effectiveness of multiple-theory and multiple-behavior interventions in an unbiased and scientific manner, mechanisms to ensure that the maximum number of representative study participants are recruited and retained throughout the investigation need to be developed and refined. Recruitment and retention are paramount to ensure generalizability of results and may affect statistical power and an investigation’s effect size ( Altman et al ., 2001 ); however, recruitment and retention remains a challenge to investigators ( Wragg et al ., 2000 ). These challenges may be magnified in theory-comparison and multiple-behavior research where the number of assessments and the dose of the intervention increases, requiring more time from the participants, potentially influencing completion and adherence rates.

The BCC recruitment and retention workgroup is endeavoring to provide an open forum for the discussion of recruitment and retention issues, including representative recruitment, retention plan development, ongoing problem solving of compliance barriers, and evaluation of general and population-specific recruitment and retention techniques. In addition, this workgroup disseminates the most up-to-date recruitment and retention strategies, materials, resources and evaluation methods. This is in an effort to strengthen the validity and generalizability among BCC-funded research projects that study highly diverse groups with variable medical conditions and social environments, and to advance knowledge of recruitment and attrition biases in the social and behavioral sciences.

Treatment fidelity

To further ensure both internal and external validity of intervention research, treatment fidelity must be maximized. Treatment fidelity involves both treatment integrity (the degree to which a treatment condition is implemented as intended) and treatment differentiation (whether the treatment conditions differ from one another as intended) ( Moncher and Prinz, 1991 ). Verification of treatment fidelity is integral to both the interpretation and generalization of research findings. Treatment fidelity can inform whether a ‘type 3’ error is made, concluding that the intervention is ineffective, when in fact it was never implemented.

Elements underlying treatment fidelity, include:

Design: Is the study consistent with the underlying theory?

Training: Has the provider acquired and maintained the requisite skill?

Delivery: Was the intervention delivered as intended?

Receipt: Did the participant understand the intervention?

Enactment: To what extent are the behaviors, skills, and/or cognitive strategies implemented by participants in real life settings?

The BCC has established a treatment fidelity workgroup whose overall aim is to advance the definition and measurement of treatment fidelity and adherence in order to facilitate the interpretation of findings and increase our understanding of the relationship of treatment intensity and dosage to treatment outcome. The workgroup also provides BCC investigators with the information and resources needed to ensure that interventions are delivered as intended, and that the dose delivered and the dose received are measured in a quantifiable manner for use in treatment validity, treatment outcome and treatment cost-effectiveness analyses. Based on existing models of treatment fidelity ( Moncher and Prinz, 1991 ; Lichstein et al ., 1994 ), this workgroup is developing and will disseminate best practice guidelines to enhance treatment fidelity in behavioral interventions.

Measurement and assessment across multiple behaviors

Conducting multiple-behavior research requires identification and organization of common measurements and assessment criteria across constructs and behaviors. There are three key issues when identifying similarities in constructs and measures between behaviors to standardize assessment. First, the equivalence of change in different behaviors has not been investigated. For example, is the equivalence of a one-cigarette reduction or an increase in a serving of vegetables the same as being physically active for 30 min in reducing morbidity and mortality? Does a dichotomous or a continuous conceptualization hold greater utility in prediction? It is also important to consider effect size within this topic of inquiry. For example, BCC intervention studies include a comparison condition so effect sizes can be calculated for each study to express a standardized treatment difference. This will allow for an interpretation of the differential magnitude of behavioral change effects for the different theories and when interventions are applied to different behaviors. Of course, because effect sizes are expressed in standard deviation units, they can and do vary with different populations, and with different inclusionary/exclusionary criteria, so this must be accounted for in comparative analyses. Another notion of equivalence is as an input and assessment of the resources needed to effect a behavioral change. With this interpretation the issue is the meaningful quantification of the resources across behaviors.

Second, instead of metric comparisons, an evaluative perspective could be adopted to identify a consensus definition of a ‘successful’ outcome or criteria in each behavioral domain. For example, for smoking 7-day abstinence rates ( Fiore et al ., 2000 ), for diet interventions using a ‘5-a-day’ behavioral criteria ( Potter et al ., 2000 ) and for physical activity using the recommendations published by CDCP/ACSM ( Pate et al ., 1995 ) may be adopted.

The third key issue when identifying similarities in constructs and measures between theories is documenting and measuring progress in the treatment population. Do we focus on and measure progress towards achievement of individual behavioral goals or do we focus on a single criterion success? In either case, interpretation of progress needs to include the clinical and the public health significance of behavioral changes.

Resolving measurement issues in theorycomparison and multiple-behavior research can aid in advancing our capability to understand relative contributions and trade-offs, and provide evaluation criteria to apply to any health behavior. This presents the opportunity for comparing interventions to establish whether different treatments are more or less effective across health behaviors. However, with using a common metric across behaviors, the issue of similarity of criteria may need to be addressed. For example, is being physically active for 30 min or more on most days of the week on the same ‘difficulty level’ as quitting smoking, or eating five servings of fruits and vegetables a day?

Using the same metric across behaviors also facilitates the identification of gateway behaviors. A gateway behavior can be thought of as a behavior that, when intervened upon, has a positive influence on other behavior changes. Generally stated, it may be that only a few behaviors are related to general health of a specific population. There is preliminary evidence that points toward this possibility as a large number of behaviors are somewhat related ( Nigg et al ., 1999 ). Examining the effect of single behavior change interventions on other health behavior changes is a first step to further develop knowledge regarding potential gateway behaviors.

The BCC workgroup on transbehavioral outcomes assessment is working to further the science of health behavior change and maintenance through cross-project collaboration by working on these kinds of issues. The workgroup has been working to explore the development of transbehavioral indices or assessment methods (such as a behavior change index) to be used in behavior change research regardless of behavior being addressed.

Reach and translation

Despite considerable advances and increasing evidence supporting health behavior interventions, few programs that have been demonstrated efficacious have been adopted in practice settings. Among the major reasons for the failure to adopt effective programs include the concern about the ability to generalize from non-representative efficacy studies, barriers to adoption under constraints of limited time and resources, and difficulties with consistency of implementation.

In general, the next generation of health behavior research needs to more closely consider issues of external validity. The studies involved in the BCC and other recent intervention research [e.g. ( Glasgow et al ., 1996 ; Nigg et al ., 1997 ; Brug et al ., 1998 )] have paid greater attention to the representativeness of individual participants than have previous studies. Work such as this provides an important step in the effort to advance our understanding of health behavior change, and how this can be translated into behavioral and environmental changes that facilitate improvements in individual and population health. The representativeness of the settings in which multiple-theory and multiple-behavior research takes place, and the intervention agents conducting the treatment are equally important as the representativeness of individual participants, but have received less attention ( Glasgow et al ., 1999 , 2002 ).

Recommendations for ways in which to increase adoption by target organizations (e.g. worksites, health care settings and schools) and the likelihood that intervention activities will be maintained after the formal evaluation is completed, include: (1) involving such organizations in intervention design beginning at the earliest stages of program planning, (2) collaborative partnerships by investigators to disseminate successful programs to target organizations, (3) reducing barriers to participation requirements and exclusion criteria for organizations, and (4) paying attention to issues of feasibility and breadth of appeal when designing interventions and contact schedules. The increased understanding through multiple-theory investigations, and the increased impact and applicability of multiple-behavior programs, should facilitate translation efforts as organizations today are less interested in having to adopt a separate health promotion program for every separate target behavior or risk factor.

With funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the BCC workgroup on reach and translation is attempting to systematically address reach and translation issues through a two-part project that is designed to develop, implement and evaluate a framework to measure intervention impact in its broadest sense (that takes into account issues of internal and external validity). This work is based on the earlier work of Glasgow et al . ( Glasgow et al ., 1999 ) who have suggested that multilevel interventions are evaluated based on their settings, goals and purpose. The RE-AIM framework for assessing such intervention includes the dimensions of reach, efficacy, adoption, implementation and maintenance. The reach and translation work group is further refining the RE-AIM framework, has surveyed the various BCC projects about how they are addressing these various issues and is serving as a coordinating resource for projects having the goal of translating their results into practice.

The mission of the BCC is to further the science of health behavior change by supporting individual projects and through cross-project collaboration that can shed further light on the processes by which people make and maintain changes in behaviors that can promote health or prevent disease in different populations and in different settings. By stimulating a wide range of cross-project collaborations, the BCC supports unique efforts for theory-comparison and multiple-behavior research that can better integrate empirical theory in our efforts to change human health behavior. Conducting theory-comparison and multiple-behavior research presents several emerging challenges but needs to be recognized as a priority research area. This includes finding new ways to enhance recruitment and retention, especially among diverse populations; improving treatment fidelity; developing common metrics across behaviors that can be used to advance the measurement and assessment of behavioral change; and expanding the reach and translation of effective intervention approaches. Such work promises to provide a stronger basis for advancing our knowledge of the processes by which people change and maintain health behaviors and how we can best facilitate those processes.

Common themes in theory-comparison and multiple-behavior research.

The authors would like to thank the NIH Behavior Change Consortium workgroups on recruitment and retention, treatment fidelity, transbehavioral outcomes, conceptual mediators, methodology and data, and reach and translation for their collective work, and for their valuable discussions and contributions. Specifically, we would like to acknowledge Drs Belinda Borelli, Mace Coday, Russell E. Glasgow and Lisa M. Klesges for their contributions to earlier drafts. We also thank Ms Janey Peterson, and Drs Patricia J. Jordan, Jay E. Maddock and Randi L. Wolf for their insightful comments.

Abrams, D. B., Orleans, C. T., Niaura, R. N., Goldstein, M. G., Velicer, W. F. and Prochaska, J. O. (1994) Smoking treatment issues: towards a stepped care approach. Tobacco Control , 2 , 517 –537.

Ajzen, I. and Fishbein, M. (1980) Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior . Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Ajzen, I. and Madden, T. J. ( 1986 ) Prediction of goal-directed behavior: attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology , 22 , 453 –474.

Allegrante, J. P. and Roizen, M. F. ( 1998 ) Can net-present value economic theory be used to explain and change health-related behaviors? Health Education Research , 13 , i –iv.

Altman, D. G., Schulz, K. F., Moher, D., Egger, M., Davidoff, F., Elbourne, D., Gotzsche, P. C. and Lang, T. ( 2001 ) The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine , 134 , 663 –694.

American Heart Association (1997) Heart and Stroke Statistical Update . American Heart Association, Dallas, TX.

Bandura, A. (1977) Social Learning Theory . Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Biddle, S. J. H. and Nigg, C. R. ( 2000 ) Theories of exercise behavior. International Journal of Sport Psychology , 31 , 290 –304.

Becker, M. H. (1974) The Health Belief Model and Personal Health Behavior. Health Education Monographs , 2 (Entire Issue).

Brug, J., Glanz, K., Van Assema, P., Kok, G. and van Breukelen, G. J. ( 1998 ) The impact of computer-tailored feedback and iterative feedback on fat fruit and vegetable intake. Health Education and Behavior , 25 , 517 –531.

Carleton, R. A., Lasater, T. M., Assaf, A. R., Feldman, H. A. and McKinlay, S. ( 1995 ) The Pawtucket Heart Health Program: community changes in cardiovascular risk factors and projected disease risk. American Journal of Public Health , 85 , 777 –785.

Deci, E. and Ryan, R. ( 1980 ). Self-determination theory: when mind mediates behavior. Journal of Mind and Behavior , 1 , 33 –43.

Emmons, K. M., Marcus, B. H., Linnan, L., Rossi, J. S. and Abrams, D. B. ( 1994 ) Mechanisms in multiple risk factor interventions: smoking, physical activity, and dietary fat intake among manufacturing workers. Working Well Research Group. Preventive Medicine , 23 , 481 –489.

Emmons, K. M. (2001) Behavioral and social science contributions to the health of adults in the United States. In Smedley, B. D. and Syme, S. L. (eds), Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behavioral Research. Committee on Capitalizing on Social and Behavioral Research to Improve the Public’s Health. National Academy Press, Washington, DC., pp. 254–231.

Farquhar, J. W. Fortmann, S. P., Flora, J. A., Taylor, C. B., Haskell, W. L., Williams, P. T., Maccoby, N. and Wood, P. D. ( 1990 ) Effects of communitywide education on cardiovascular disease risk factors. The Stanford Five-City Project. Journal of the American Medical Association , 264 , 359 –365.

Fiore, M., Bailey, W., Bennett, G., Bennett, H., Cohen, S., Dorfman, S. F., Fox, B., Goldstein, M., Gritz, E., Hasselblad, V., et al . (2000) Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. Clinical Practice Guideline . US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Rockville, MD.

Glasgow, R. E., Eakin, E. G. and Toobert, D. J. ( 1996 ) How generalizable are the results of diabetes self-management results? The impact of participation and attrition. The Diabetes Educator , 22 , 573 –585.

Glasgow, R. E., Vogt, T. M. and Boles S. M. ( 1999 ) Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health , 89 , 1322 –1327.

Glasgow, R. E., Bull, S. S., Gillette, C., Klesges, L. M. and Dzewaltowski, D. A. (2002) Behavior change intervention research in health care settings: a review of recent reports, with emphasis on external validity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine , in press.

Green, L. W. and Kreuter, M. W. (1999) Health Promotion Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach . Mayfield, Mountain View, CA.

Hall, S. M., McGee, R., Turnstall, C. D., Duffy, J. and Benowitz, N. ( 1989 ) Changes in food intake and activity after quitting smoking. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology , 57 , 81 –86.

Hellmich, N. (1997) Fighting cancer: diet and exercise. USA Today , October 1,

Holmes, D. S. and Roth, D. L. ( 1988 ) Effects of aerobic exercise training and relaxation training on cardiovascular activity during psychological stress. Journal of Psychosomatic Research , 32 , 469 –474.

Hughes, J. R. ( 1984 ) Psychological effects of habitual aerobic exercise: a critical review. Preventive Medicine , 13 , 66 –78.

International Longevity Center (1999) Maintaining Healthy Lifestyles: A Lifetime of Choices . A workshop co-sponsored by Canyon Ranch Resort and International Life Sciences Institute.

Kano, M. J. and Tucker, L. A. ( 1993 ) The relationship between aerobic fitness and dietary intake in adult females. Medicine, Exercise, Nutrition and Health , 2 , 155 –161.

King, T. K., Marcus, B. M., Pinto, B. M., Emmons, K. M. and Abrams, D. B. ( 1996 ) Cognitive-behavioral mediators of changing multiple behaviors: smoking and a sedentary lifestyle. Preventive Medicine , 25 , 648 –691.

Klesges, R. C., Benowitz, N. L. and Meyers, A. W. ( 1991 ) Behavioral and biobehavioral aspects of smoking and smoking cessation: the problem of post cessation weight gain. Behavioral Therapy , 22 , 179 –199.

Levkoff, S., Prohaska, T., Weitzman, P. F. and Ory, M. G. ( 2000 ) Recruitment and retention in minority populations: lessons learned in conducting research on health promotion and minority aging. Journal of Mental Health and Aging , 6 , 5 –8.

Lichstein, K. L., Riedel, B. W. and Grieve, R. ( 1994 ) Fair tests of clinical trials: a treatment implementation model. Advances in Behavioral Research and Therapy , 16 , 1 –29.

Luepker, R. V., Murray, D. M., Jacobs, D. R., Jr. Mittelmark, M. B., Bracht, N., Carlaw, R., Crow, R., Elmer, P., Finnegan, J., Folsom, A. R., Grimm, R., Hannan, P. J., Jeffrey, R., Lando, H., McGovern, P., Mullis, R., Perry, C. L., Pechacek, T., Pirie, P., Sprafka, M., Weisbrod, R. and Blackburn, H. ( 1995 ) Community education for cardiovascular disease prevention: risk factor changes in the Minnesota Heart Health Program. American Journal of Public Health , 83 , 1383 –1393.

Maddux, J. E. ( 1993 ) Social cognitive models of health and exercise behavior: an introduction and review of conceptual issues. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology , 5 , 116 –140.

Manson, J. E., Tosteson, H., Ridker, P. M., Satterfield, S., Hebert, P., O’Connor, G. T., Buring, J. E. and Hennekens, C. H. ( 1993 ) The primary prevention of myocardial infarction. New England Journal of Medicine , 326 , 1406 –1416.

Marcus, B. H., Albrecht, A. E., Niaura, R. S., Abrams, D. B. and Thompson, P. D. ( 1991 ) Usefulness of physical exercise for maintaining smoking cessation in women. American Journal of Cardiology , 68 , 406 –407.

Marcus, B. H., Albrecht, A. E., Niaura, R. S., Taylor, E. R., Simkin, L. R., Feder, S. I., Thompson, P. D. and Abrams, D. B. ( 1995 ) Exercise enhances the maintenance of smoking cessation in women. Addictive Behaviors , 20 , 87 –92.

Marcus, B. H., Nigg, C. R., Riebe, D. and Forsyth, L. H. ( 2000 ) Interactive communication strategies: implications for population-based physical-activity promotion. American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 19 , 121 –126.

Marsh, H. W. ( 1994 ) Sport motivation orientations: beware of jingle-jangle fallacies. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology , 16 , 365 –380.

McLeroy, K. R., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A. and Glanz, K. ( 1988 ) An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly , 15 , 351 –377.

Minkler, M. and Wallerstein, N. (1997) Improving health through community organization and community building. In Glanz, K., Lewis, F. M. and Rimer, B. K. (eds), Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice . Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 60–84.

Moncher, F. J. and Prinz, R. J. ( 1991 ) Treatment fidelity in outcome studies. Clinical Psychology Review , 11 , 247 –266.

National Center for Health Statistics. ( 1997 ) Top ten US population causes of death. Monthly Vital Statistics Report , 45 , 40 –43.

Nigg, C. R., Burbank, P., Padula, C., Dufresne, R., Rossi, J. S., Velicer, W. F., Laforge, R. G. and Prochaska, J. O. ( 1999 ) Stages of change across ten health risk behaviors for older adults. The Gerontologist , 39 , 473 –482.

Nigg, C. R., Courneya, K. S. and Estabrooks, P. A. ( 1997 ) Maintaining attendance at a fitness center: an application of the decision balance sheet. Behavioral Medicine , 23 , 130 –137.

Ory, M., Jordan, P. J. and Bazzarre T. ( 2002 ) The Behavior Change Consortium: setting the stage for a new century of health behavior-change research. Health Education Research , 17 , 500 –511.

Ory, M. G., Lipman, P. D., Karlen, P. L., Gerety, M. B., Stevens, V. J., Fiatarone, M. A., Buchner, D. M., Schechtman, K. B. and The FICSIT Group (2002b) Recruitment of older participants in frailty/injury prevention studies. Prevention Science , in press.

Pate, R. R., Pratt, M., Blair, S. N., Haskell, W. L. Macera, C. A., Bouchard, C., Buchner, D., Ettinger, W., Heath, G. W., King, A. C., Kriska, A., Leon, A. S., Marcus, B. H., Morris, J., Pfaffenbarger, R. S., Patrick, K., Pollock, M. L., Rippe, J. M., Sallis, J. and Whilmore, J. H. ( 1995 ) Physical activity and public health. A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. Journal of the American Medical Association , 273 , 402 –407.

Potter, J. D., Finnegan, J. R., Guinard, J. X., Huerta, E. E., Kelder, S. H., Kristal, A. R., Kumanyika, S., Lin, R., McAdams Motsinger, B., Prendergast, F. G., Sorensen, G. and Callahan, K. M. (2000) 5 A Day for Better Health Program Evaluation Report . NIH publ. 01-4904. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD.

Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C. C. and Norcross, J. C. ( 1992 ) In search of how people change: applications to the addictive behaviors. American Psychologist , 47 , 1102 –1114.

Rosenstock, I. M. ( 1966 ) Why people use health services. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly , 44 , 94 –124.

Sallis, J. F. and Owen, N. (1999) Physical Activity & Behavioral Medicine . Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Smedley, B. D. and Syme, S. L. (eds) (2000) Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behavioral Research . National Academy Press, Washington, DC.

Steckler, A., Allegrante, J. P., Altman, D., Brown, R., Burdine, J. N., Goodman, R. M. and Jorgensen, C. ( 1995 ) Health education intervention strategies: recommendations for future research. Health Education Quarterly , 22 , 307 –328.

US Department of Health and Human Services (2000) Healthy People 2010 Fact Sheet [Online]. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Available: http://www.health.gov/healthypeople . Accessed: 7 February 2000.

Wilmore, J. H. and Costill, D. L. (1994) Physiology of Sport and Exercise . Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL.

Woolf, S. H. ( 1999 ) The need for perspective in evidence-based medicine. Journal of the American Medical Association , 282 , 2358 –2365.

Wragg, J. A., Robinson, E. J. and Lilford, R. J. ( 2000 ) Information presentation and decisions to enter clinical trials: a hypothetical trial of hormone replacement therapy. Social Science & Medicine , 51 , 453 –462.

Author notes

Department of Public Health Sciences and Epidemiology, John A. Burns School of Medicine, University of Hawaii at Mãnoa, Honolulu, HI 96822, 1National Center for Health Education and Department of Health and Behavior Studies, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027, and 2School of Rural Public Health, Texas A & M University System, College Station, TX 77840, USA, and formerly National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1465-3648

- Print ISSN 0268-1153

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 08 September 2010

The effectiveness of interventions to change six health behaviours: a review of reviews

- Ruth G Jepson 1 ,

- Fiona M Harris 2 ,

- Stephen Platt 3 &

- Carol Tannahill 4

BMC Public Health volume 10 , Article number: 538 ( 2010 ) Cite this article

82k Accesses

245 Citations

15 Altmetric

Metrics details

Several World Health Organisation reports over recent years have highlighted the high incidence of chronic diseases such as diabetes, coronary heart disease and cancer. Contributory factors include unhealthy diets, alcohol and tobacco use and sedentary lifestyles. This paper reports the findings of a review of reviews of behavioural change interventions to reduce unhealthy behaviours or promote healthy behaviours. We included six different health-related behaviours in the review: healthy eating, physical exercise, smoking, alcohol misuse, sexual risk taking (in young people) and illicit drug use. We excluded reviews which focussed on pharmacological treatments or those which required intensive treatments (e.g. for drug or alcohol dependency).

The Cochrane Library, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE) and several Ovid databases were searched for systematic reviews of interventions for the six behaviours (updated search 2008). Two reviewers applied the inclusion criteria, extracted data and assessed the quality of the reviews. The results were discussed in a narrative synthesis.

We included 103 reviews published between 1995 and 2008. The focus of interventions varied, but those targeting specific individuals were generally designed to change an existing behaviour (e.g. cigarette smoking, alcohol misuse), whilst those aimed at the general population or groups such as school children were designed to promote positive behaviours (e.g. healthy eating). Almost 50% (n = 48) of the reviews focussed on smoking (either prevention or cessation). Interventions that were most effective across a range of health behaviours included physician advice or individual counselling, and workplace- and school-based activities. Mass media campaigns and legislative interventions also showed small to moderate effects in changing health behaviours.

Generally, the evidence related to short-term effects rather than sustained/longer-term impact and there was a relative lack of evidence on how best to address inequalities.

Conclusions

Despite limitations of the review of reviews approach, it is encouraging that there are interventions that are effective in achieving behavioural change. Further emphasis in both primary studies and secondary analysis (e.g. systematic reviews) should be placed on assessing the differential effectiveness of interventions across different population subgroups to ensure that health inequalities are addressed.

Peer Review reports

Chronic diseases, such as cancers, cardiovascular diseases (CVD), diabetes, and respiratory diseases, account for 59% of the 57 million deaths annually and 46% of the global burden of disease [ 1 ]. In 2002, the World Health Report [ 2 ] identified a number of important lifestyle risk factors for such diseases, including physical inactivity; diet-related factors and obesity; and the use of addictive substances such as tobacco, alcohol and illicit drugs.

These lifestyle factors have significant effects on mortality and morbidity, particularly in industrialised countries. For example, data for the WHO European Region show that physical inactivity is a risk factor for diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, non-insulin- dependent diabetes, hypertension, some forms of cancer, musculoskeletal diseases and psychological disorders. These diseases are estimated to account for nearly 600,000 deaths per year [ 3 ]. Similarly, obesity and being overweight are risk factors for diseases such as type 2 diabetes, certain types of cancer and cardiovascular diseases, and affect between 30% and 80% of adults and up to one third of children [ 4 ]. Alcohol is also a significant cause of mortality: alcohol-related deaths increased by 15% between 2000 and 2002, and now represent 6.3% of all deaths in the European Region [ 5 ].

Sexual risk taking and drug misuse also significantly contribute to ill health and have negative effects on well being among young people. In 28 high income (OECD) nations at least 1.25 million teenagers become pregnant each year; of these, approximately 40% (half a million) will seek to terminate the pregnancy while the other 60% (three quarters of a million) will become teenage mothers [ 6 ]. The United States has the highest teenage birth rate in the developed world and the United Kingdom has the highest teenage birth rate in Europe [ 6 ]. Worldwide, young people (15-24 years) have the highest rate of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) of any age group. Up to 60% of the new infections and 50% of all people living with HIV globally are in this age group [ 7 ].

Most public health and health promotion interventions - whether they focus on the individual, community, whole populations or the environment - seek in some way to change health behaviour by changing health-related knowledge, attitudes and/or structural barriers and facilitators [ 8 ]. Social psychological theories such as social cognition theory are commonly used in the development of interventions [ 9 ]. Key elements of such theories include knowledge of health risks, perceived self efficacy, goals and motivations and barriers and facilitators [ 10 ]. Most health promotion interventions include one or more of the following components: education and knowledge building (around the health issue); motivation and goal setting (e.g. alcohol brief interventions and counselling); and community-based techniques to encourage a change in behaviour or reduce structural or cultural barriers. These interventions can be delivered at three different levels, which we explore below: individual, community and population level interventions. Individually targeted interventions are usually aimed at those with an existing 'risky' behaviour such as smoking or alcohol misuse. Community level interventions focus on particular population groups such as people in a particular workplace or young people in schools. Finally, population level interventions tend to rely on the use of mass media activities, policies or legislation.

All three levels of intervention are aimed at achieving changes in lifestyle, as well as improving knowledge and influencing attitudes towards positive healthy behaviours. However, there is a need to take into account the socio-economic and cultural contexts within which they are located. For instance, an intervention to promote healthy eating within an affluent locality might involve a rather different approach from one undertaken in an area of low income and high unemployment.

In light of the growing concern around the link between 'negative' health behaviours and ill health, we were commissioned by the Public Health section of the UK's National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) under the Behaviour Change Programme Development Group to review the relevant evidence in this area. This paper is an update of the findings of this 'review of reviews' of interventions to change health behaviours [ 11 ]. It was one type of evidence used to develop NICE public health programme guidance on behaviour change [ 12 ].

Our aim was systematically to collate, evaluate and synthesise review-level findings on the effectiveness of interventions to change unhealthy behaviours or promote healthy behaviours. This synthesis was intended to provide researchers, policy planners, decision-makers and practitioners with an accessible, good quality overview of the evidence in these topic areas. The review focused on six groups of behaviour change interventions:

Interventions to encourage people to quit tobacco use

Interventions to reduce heavy alcohol use

Interventions to encourage physical activity

Interventions to encourage healthy eating (excluding diets for weight loss)

Interventions to prevent or reduce illicit drug use (excluding drug dependency)

Interventions to prevent or reduce sexual risk taking in young people.

A subsidiary aim of the review was explore, where possible, the evidence of impact of interventions on health inequalities.

Inclusion criteria

1) types of reviews.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses published between 1995 and 2008 (reviews published before this time are likely to be out of date)

English language reviews as we were constrained by time and resource issues. (However, many of the included English language reviews contained primary studies in languages other than English.)

Cochrane reviews and systematic reviews in the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), which encompasses reviews gathered from searching a wide range of OVID databases

Other good quality reviews which have a low risk of bias (see section on quality assessment)

Less robust systematic reviews in areas where no other evidence exists.

2) Content of the reviews

Two sets of inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied in the selection process: those that applied across all the health behaviours (see Table 1 ); and those that were specific to particular health behaviours (Table 2 ). For the six specific health behaviours of interest, interventions aimed at either preventing or delaying onset of the health behaviour were included, as well as those aimed at helping people to change an existing behaviour. However, interventions aimed at treating alcohol or drug dependency were not included as they were considered to require more intensive types of treatments, hence different forms of intervention. Healthy eating and physical activity were limited to outcomes related to changes in knowledge, attitudes or behaviour but did not include outcomes such as weight loss, weight reduction, nor programmes of obesity treatment or exercise specifically targeting high risk groups such as people with cardiovascular disease or cancer. Reviews of the following interventions were also excluded: health screening; psychiatric interventions as part of treatment for those with mental illness; interventions with only a clinical or pharmacological focus (e.g. reducing risk of heart disease); interventions carried out within secondary or tertiary care; drug interventions (including the use of vitamin supplements for healthy diets); and interventions aimed at treating alcohol or drug dependency.

Search strategy

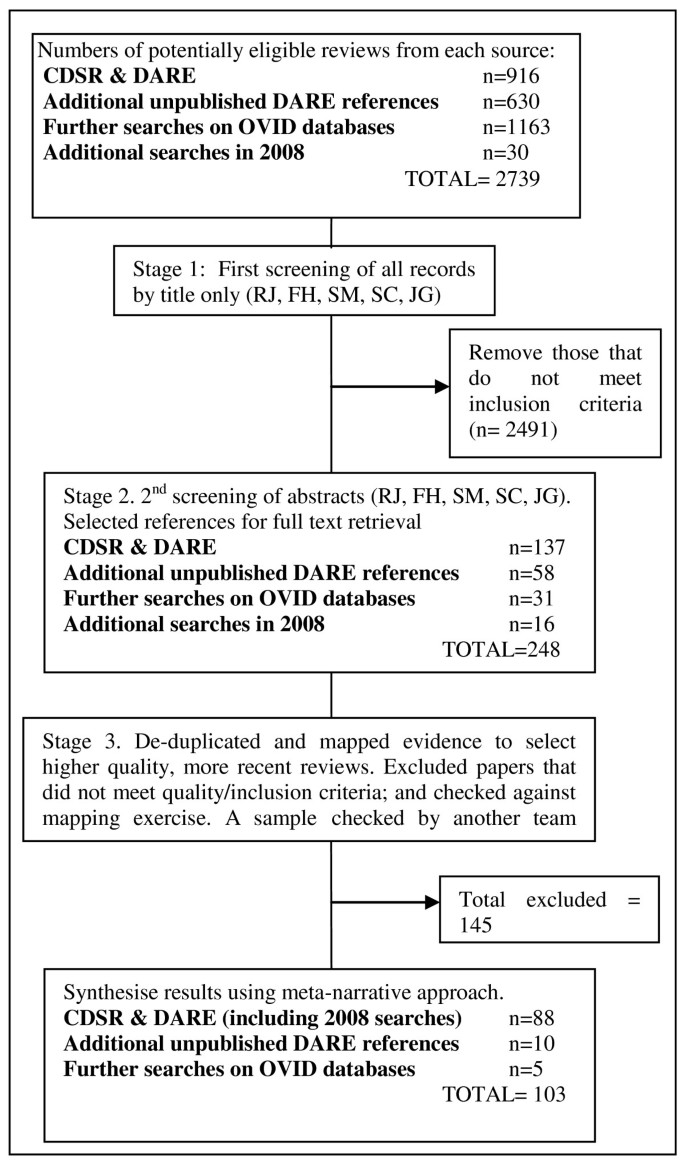

Searches were initially conducted in February 2006 for Cochrane and other systematic reviews and updated in 2008, as detailed below. As a starting point to identify the highest quality review level evidence, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) was searched to identify Cochrane Reviews and the Database of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE) was used for non-Cochrane reviews. DARE includes published and unpublished systematic reviews that have been assessed according to strict quality criteria by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) in York, UK. DARE represents an excellent resource since it includes quality assessed systematic reviews sourced by monthly searches of a wide range of electronic databases. As a final check to reveal what more recent reviews might be missed through this strategy, we also ran searches for each of the six public health topics on a range of OVID databases: AMED, ERIC, Cinahl, EmBase, Medline and PsycINFO. These searches were restricted by terms to identify reviews only, including 'meta-analysis', 'evidence-based review' or 'systematic review'. Full search histories are available on request from the corresponding author.

These searches generated a total of 2709 potentially relevant reviews. The search was updated in November 2008 by searching The Cochrane Library and DARE for new and updated Cochrane reviews and other high quality systematic reviews published since February 2006. This yielded a further 16 new reviews (out of 30 identified through the search), and 12 Cochrane reviews which had been updated since the initial search.

Applying inclusion criteria

Titles and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers. Any discrepancies in selections were discussed until consensus was reached. Another stage of screening consisted of a mapping exercise, where references were mapped into categories of evidence and two reviewers agreed to include or exclude further references based on the quality of the reviews and the date of publication. Since Cochrane reviews are usually the most comprehensive and of high quality, they were selected if there was more than one review in a particular topic area. Other reviews were selected on the basis of most recent publication date and quality of the review (see below for details of how we assessed quality of the reviews). The full review process is illustrated in the quorum statement (see Figure 1 ).

Quorum statement .

Quality assessment

Potentially relevant reviews were assessed for quality using a checklist adapted from the NICE 'Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance' [ 13 ]. We prioritised reviews that had a transparent and replicable data search methodology and analysis. We scored reviews as "++" if at least 10 specified criteria were met, "+" if at least seven criteria were met, and "-" if fewer than seven criteria were met (Table 3 ). We also scored reviews on the type of evidence they were reviewing, such as RCTs or non-RCTs (see Table 4 ). The classification of bias (e.g. ++) was then combined with the type of evidence (e.g. 1) to give a level of evidence. For example, high-quality meta-analyses or systematic reviews of RCTs were coded as 1++. All data extracted on quality were extracted by one reviewer and checked by a second member of the team. Any discrepancies in the data that were extracted (e.g. differences in scoring) were resolved by discussion

Data extraction

Data were extracted by one of four people, and a sample checked by another member of the team. No formal synthesis (such as meta-analysis) was undertaken: a narrative summary of the results was more appropriate for a review of reviews.

We identified 103 systematic reviews evaluating interventions aimed at changing health behaviour in one or more of the six areas. Some of these reviews covered several behaviours. The reviews included studies which targeted specific individuals or organisations (e.g. through counselling within education) or more generally (e.g. mass media interventions or legislation).

We synthesised the results under three research areas:

Evidence for the effectiveness of interventions to prevent, reduce or promote the six health behaviours

Evidence for the effectiveness of interventions across several health behaviours

Evidence for the effectiveness of interventions in targeting health inequalities.

Full consideration of such a large number of reviews would prove too lengthy for this paper, therefore we have chosen to highlight the main findings rather than provide details of individual interventions discussed within each paper. A fuller version of the original document is available from the authors on request. Table 5 summarises the quality of the included reviews and Table 6 provides a brief overview of the studies, grouped by level of intervention (population, community or individual).

1. Evidence for the effectiveness of interventions to prevent, reduce or promote each of the six health behaviours

The focus of interventions varied, depending on the target population. Interventions targeting individuals generally aimed to change an existing behaviour such as cigarette smoking or alcohol misuse, whilst interventions targeting workplaces, schools or the general population were often more focused on promoting positive behaviours (e.g. healthy eating or exercise).

1.1. Smoking and tobacco use

We identified 48 systematic reviews which evaluated interventions to aid smoking cessation, prevent relapse or prevent people taking up smoking [ 14 – 61 ]. One further review evaluated population-level tobacco control interventions and their effect on social inequalities [ 62 ]. This review is discussed in more detail in section 3.

Eleven reviews evaluated interventions aimed at the prevention of smoking, promoting smoking cessation or reducing smoking prevalence in young people [ 22 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 40 , 46 , 50 , 51 , 53 , 56 , 60 , 61 ]. There is some evidence that mass media interventions can be effective in preventing the uptake of smoking in young people, but overall the evidence is not strong. Information provision interventions alone are not effective and there is only limited evidence for the effects of interventions that mainly seek to develop social competence.

There is little evidence of effectiveness of other interventions, such as reducing tobacco sales to minors. Interventions with retailers can lead to large decreases in the number of outlets selling tobacco to youths but there is insufficient evidence to say whether this is linked to reduction or cessation of smoking in young people.

Twenty six of the 48 systematic reviews evaluated interventions aimed at achieving positive changes in tobacco use in adults known to use tobacco (i.e. targeting smokers). Of these, twenty-two of these evaluated interventions for adult cigarette smokers in general, two focussed specifically on pregnant and postpartum women [ 25 , 36 ], and two evaluated interventions for smokeless tobacco use [ 24 , 38 ]. The following sections describe the range of interventions to reduce tobacco consumption in individuals and are grouped by their effectiveness.

Interventions which show a positive effect include advice from health professionals, the rapid smoking form of aversion therapy, self help materials, telephone counselling (compared to less intensive interventions), nurse-delivered interventions, group counselling (which is also more effective than self help), and oral examination and feedback for reducing smokeless tobacco use. However, there is no evidence for the effectiveness of interventions targeting waterpipe smokers. Interventions to promote smoking cessation or smoking reduction with pregnant women are generally effective across the range of intervention types, indicating that pregnancy may be a point in the lifecourse when positive behaviour change can be achieved.

There is less clear or inconclusive evidence of effectiveness for social support interventions (e.g. buddy systems or friends and family support), relapse prevention, biomarker feedback or biomedical risk assessment, exercise, Internet and computer-based interventions and interventions by community pharmacy personnel or dentists. Currently there is not enough evidence to show which interventions are most effective for decreasing parental smoking and preventing exposure to tobacco smoke in childhood.

Interventions for which there is no evidence of effectiveness include hypnotherapy and interventions based on the transtheoretical model of change. The latter proposes that interventions designed to take into account an individual's current stage of change (or readinesss to change a health behaviour) will be more effective and efficient than "one size fits all" interventions [ 63 ]. The model assumes that people move through six changes of change, from 'pre-contemplation' through to 'termination' (when the behaviour has successfully been changed). However, this assumption does not sit comfortably within wider theories of social change, which posit that change rarely moves in a linear fashion. Additionally, a systematic review exploring a range of 'stage based' interventions for smoking cessation found little evidence of effectiveness [ 45 ].

Six studies evaluated smoking interventions that were undertaken in either workplace or community settings [ 19 , 26 , 33 , 49 , 64 , 65 ]. Interventions which show an effect in the workplace include those aimed at encouraging individuals to quit. The results are consistent with those found in other settings [ 64 ]. Particularly effective interventions include individual and group counselling and pharmacological treatment to overcome nicotine addiction. Self-help materials are less effective, and competitions and incentives, while increasing attempts to stop smoking, were not consistently found to increase the rate of quitting. Interventions aimed at the wider community included multi-component interventions and those which use multiple channels to provide reinforcement, support and norms for non-smoking. These show limited effectiveness.

Five systematic reviews evaluated interventions aimed at the general population to prevent the uptake of smoking or reduce smoking rates [ 15 , 16 , 28 , 47 , 66 ]. Mass media interventions show evidence of a small effect in preventing the uptake of smoking, but the evidence comes from a heterogeneous group of studies of variable methodological quality. Smoking cessation interventions that show some evidence of effectiveness include 'Quit and Win' contests and policies to reduce smoking in public places. However, policy interventions are normally evaluated using non-controlled designs (e.g. before and after studies), which makes it difficult to determine the extent to which the outcomes could be attributed to the intervention.

1.2. Physical activity

Twenty-four systematic reviews evaluated interventions to increase or promote the uptake of physical activity [ 23 , 39 , 58 , 67 – 85 ]. Six of these explored the effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity in young people [ 70 , 78 , 83 , 85 – 87 ]. There is moderate evidence of effectiveness for curriculum-based activities in schools. The most effective school-based physical activity interventions include printed educational materials and curricula that promoted increased physical activity during the whole day (i.e., recess, lunch, class-time, and physical education classes). The most effective non-curricular school activities include education and provision of equipment for monitoring TV or video-game use; engaging parents in supporting and encouraging their children's physical activity; and those implemented during school breaks (painting school playgrounds, playground supervisors implementing a games curriculum, and taught playground games or introduced equipment). There is no evidence of an effect of other non-curricular activities, such as active travel to school, extra-curricular activities and summer schools or camps.

The most recent review reported strong evidence that school-based interventions with involvement of the family or community and multi-component interventions can increase physical activity in adolescents [ 85 ].

Ten systematic reviews evaluated targeted interventions aimed at increasing physical activity for adults. Eight of these evaluated interventions for adults over 18 years [ 23 , 39 , 71 , 72 , 74 , 75 , 88 , 89 ], while two evaluated interventions specifically for the older population [ 69 , 84 ]. The interventions included the use of pedometers, telephone counselling, and professional advice and guidance (with continued support). Most of the reviews found some evidence of moderate effectiveness in the short term (less than three months) in increasing physical activity, but effects are not necessarily sustained over a longer time period (e.g. twelve months). Many of the studies were limited by the recruitment of motivated volunteers, and no studies examined the effect of interventions on participants from varying socioeconomic or ethnic groups. In addition, even those interventions which are moderately effective in increasing exercise did not necessarily meet a predetermined threshold of physical activity. These findings were also supported by the findings from reviews of interventions for the older population, which found a small but short-lived effect of home-based, group-based and educational physical activity interventions on increasing physical activity.

Physical activity interventions for which there is inconclusive evidence include biomarker feedback and brief motivational interventions. In addition, there is no evidence that interventions based on the stages of change model increase levels of physical activity.

One systematic review evaluated physical activity programmes in the workplace [ 82 ], finding evidence of a moderate effect on increasing physical activity levels. Interventions comprised self-help or educational programmes, and exercise programmes involving aerobics, walking, jogging, swimming, cycling, muscle strengthening, endurance, flexibility and stretching.

Four systematic reviews evaluated interventions aimed at increasing physical activity in the general population. Two evaluated interventions to increase participation in sport [ 76 , 90 ], one evaluated interventions to promote walking and cycling [ 81 ], and one evaluated mass media interventions [ 73 ]. However, the first two reviews found that no studies had been undertaken to identify any intervention designed to increase active and/or non-active participation in sport (including policy interventions). There is evidence that targeted behaviour change programmes can be effective in changing the transport choices of motivated subgroups, but the social distribution of their effects and their effects on the health of local populations are unclear. Evidence of effectiveness of other types of intervention is inconsistent, of low validity, based on single, highly contextualised studies, or non-existent. There is evidence (with a higher risk of bias) that mass media interventions may increase physical activity, but the effects tend to be in small subgroups or for specific behaviours, such as walking.

1.3. Alcohol misuse

Fifteen reviews evaluated a range of interventions aimed at reducing alcohol consumption in problem drinkers, preventing or delaying the onset of alcohol use in young people, or reducing dangerous activities associated with drinking (e.g. drink-driving) [ 91 – 105 ]. No consistent definitions of what constitutes harmful alcohol consumption were available from existing guidelines or research; however, it is commonly held that behavioural interventions are appropriate for mild to moderate alcohol consumption or binge drinking, whereas more severe problems, such as alcohol dependency, may require specialist addiction treatment. Interventions for the latter were excluded from the review.

Two reviews evaluated interventions targeting school children [ 95 , 96 ]. There is evidence of a positive effect of school-based instructional programmes for reducing riding with drivers under the influence of alcohol. However, there is insufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness of these programmes for reducing drinking and driving. There is also insufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness of peer organisations (e.g. groups of students and/or staff who encourage others to refrain from drinking alcohol) and social norming campaigns (typically, public information programmes based on the assumption that children may overestimate the amount and frequency of their peers' alcohol consumption) to reduce alcohol use, due to the small number of available studies.

Several reviews evaluated interventions for adult problem drinkers. One review assessed home visits for pregnant women who were problem drinkers [ 93 ] and found insufficient evidence to recommend their routine use. Three reviews were of interventions aimed at reducing driving under the influence of alcohol [ 97 , 100 , 103 ]. For convicted drink drivers, there is evidence of an effect of alcohol interlock programmes (where the car ignition is locked until the driver provides an appropriate breath specimen), but the effect of other interventions is inconclusive due to the variable quality of the evidence. According to a Cochrane review [ 97 ] which evaluated the impact of increased police patrols for alcohol impaired drinking, most studies found that such patrols reduce traffic crashes and fatalities. However these conclusions were based on poor quality evidence.

Four further reviews evaluated interventions for problem drinkers in general [ 91 , 98 , 102 , 105 ]. There is evidence of a small positive effect of brief behavioural counselling interventions in reducing alcohol intake. The most recent Cochrane review [ 98 ] of brief interventions delivered to people attending primary care (1-4 sessions) found that, overall, such interventions lower alcohol consumption. When data were available by gender, the effect was clear in men at one year of follow up, but not in women. The authors concluded that longer duration of counselling probably has little additional effect.

Four systematic reviews evaluated mass media interventions [ 92 , 94 ] and legislative interventions [ 99 , 104 ] aimed at people who drink and drive. None of the reviews included evidence from RCTs, mainly because of the difficulty of conducting controlled trials in these areas. One well conducted review found insufficient evidence of effectiveness for mass media 'designated driver programmes' in increasing the number of designated drivers [ 92 ]. The other reviews reported that effective interventions for reducing alcohol and driving related outcomes included mass media campaigns [ 94 ]; low blood alcohol concentration laws for young drivers [ 104 ]; and a policy of a minimum legal drinking age (MLDA) of 21 years (which reduced traffic crashes and alcohol consumption) [ 99 ].

We did not identify any reviews which evaluated evidence relating to mass media interventions to promote 'safe' drinking levels or reduce 'risk drinking' (e.g. binge drinking).

1.4. Healthy eating

Thirteen systematic reviews evaluating behavioural or psychological interventions to promote healthy eating were identified [ 23 , 58 , 79 , 106 – 115 ]. Overall there is evidence that interventions can change eating habits, at least in the short term.

Four reviews evaluated interventions targeted at children or young people [ 79 , 112 – 114 ]. There is evidence of an effect of interventions aimed at increasing fruit and vegetable intake in children aged 4-10 years and interventions for youth aged 11-16 years. However, there is insufficient evidence of an effect of interventions in pre-school children.

Three reviews evaluated community based interventions. One review reported evidence of a small effect of community interventions for people aged 4 years and above on increasing fruit and vegetable intake [ 107 ]. There is also evidence that interventions based in supermarkets are effective for promoting positive changes in shopping habits, although effectiveness was found to be confined only to the period during which the intervention took place [ 110 ]. Lastly one review evaluated community-level interventions for older people [ 109 ] but found little or no effect of interventions to increase fruit and vegetable intake.

Six reviews evaluated a range of targeted interventions or interventions aimed at individuals. There is evidence of a positive effect of stage-based lifestyle interventions delivered to a primary care population [ 58 ], telephone based interventions [ 108 ] and nutritional counselling interventions [ 106 ]. A review of interventions using a Mediterranean diet showed positive results for a range of outcomes, but it is not clear how the interventions brought about behaviour change [ 111 ].

There is inconclusive evidence as to the effectiveness of motivational interviewing [ 23 ] for changing eating behaviours. There is also inconclusive evidence for interventions such as health education, counselling, changes in environment and changes in policy, to encourage pregnant women to eat healthily [ 115 ].

1.5. Illicit drug use

Only four reviews met our inclusion criteria for this section. There is more review level evidence relating to interventions aimed at treating drug users, which was specifically excluded under our search criteria.

All four reviews evaluated community-level interventions to prevent illicit drug use with young people [ 101 , 116 – 118 ]. The evidence base for this topic is limited and there are substantial gaps in knowledge. A positive effect of skill-based programmes in schools is demonstrated, but it is not possible to reach any conclusion about the effectiveness of non-school based programmes. There is also some evidence that the 11-13 age range may be a crucial period for intervention with vulnerable young people.

1.6. Sexual risk taking in young people

Eight systematic reviews evaluating community based interventions were identified in this area. Four reviews focused on the reduction or prevention of HIV or other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [ 119 – 122 ], while four evaluated sexual health promotion and the reduction or prevention of teenage pregnancies [ 123 – 126 ]. The reviews were of variable quality and most commented on the poor quality of existing primary studies, which made the process of synthesising evidence difficult. However, two conclusions can be drawn. First, in the area of risk reduction and prevention programmes, interventions are most effective in promoting the uptake of condom use, with some success in reducing the number of sexual partners and the frequency of sex. Second, interventions seeking to promote the use of contraception are more effective than interventions that promote abstinence. There was a single study of counselling to prevent or reduce teenage pregnancies, but the authors found that the available evidence was of such poor quality that they were unable to reach any firm conclusions about effectiveness.

2. Evidence to suggest that some interventions are effective/ineffective across the range of health behaviours

Many of the interventions included in this review were behaviour specific - e.g. aversion therapy for smoking cessation, tobacco bans and drink driver-related interventions. However, there were a few interventions - such as counselling and physician advice, mass media and motivational interventions - that were used across a range of behaviours. Table 7 outlines the interventions and their effectiveness across different behaviours.

3. Evidence for the effectiveness of interventions in targeting health inequalities

Despite the widely acknowledged link between social and economic inequalities and health, our review of reviews found no evidence which helped to develop an understanding of the following:

Inequalities in levels of physical activity; alcohol misuse; healthy eating; illicit drug use; and sexual risk taking among young people.

Inequalities in access to interventions to promote change in behaviour

Inequalities in recruitment to interventions of 'hard to reach' groups

Differential effectiveness of health behaviour interventions, which may result in increased health inequalities.