Importance of Problem Solving Skills and How to Nurture them in your Child

We all face problems on a daily basis. You, me—our kids aren’t even exempted. Across all different age groups, there rarely is a day when we don’t experience them.

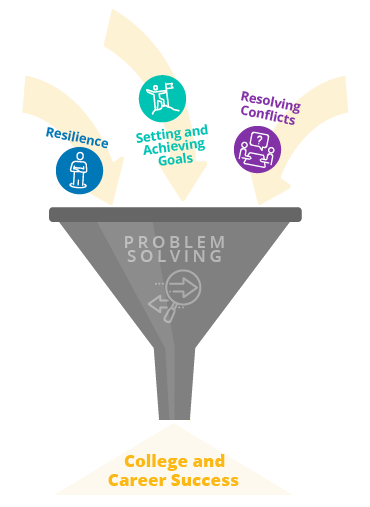

Teaching our kids to develop resilience can help as they face these challenges. Practical problem solving skills are just as necessary to teach our kids. The methods needed to resolve problems may require other skills such as creativity, critical thinking, emotional intelligence, teamwork, decision making, etc.

Unlike with math problems, life doesn’t just come with one formula or guidebook that’s applicable to solve every little problem we face. Being adaptable to various situations is important. So is nurturing problem solving skills in your child.

Here we’ll take a look at the importance of problem solving skills and some ways to nurture them in your child.

Why do we need problem-solving skills?

One thing that always comes up when we speak of problem-solving skills are the benefits for one’s mental health .

Problems are often complex. This means that problem solving skills aren’t a one-size-fits-all solution to all problems.

Strengthening and nurturing this set of skills helps children cope with challenges as they come. They can face and resolve a wider variety of problems with efficiency and without resulting in a breakdown.

This will help develop your child’s independence, allowing for them to grow into confident, responsible adults.

Another importance of problem-solving skills is its impact on relationships . Whether they be friendships, family, or business relationships, poor problem solving skills may result in relationships breaking apart.

Being able to get to the bottom of a problem and find solutions together, with all the parties involved, helps keep relationships intact and eliminate conflicts as they arise. Being adept at this skill may even help strengthen and deepen relationships.

What steps can you take to nurture your child’s problem-solving skills?

Nurturing problem-solving skills in your child requires more than just focusing on the big picture and laying out steps to resolve problems. It requires that you teach them to find and focus on a problem’s essential components.

This may challenge your child’s critical thinking and creativity, among other things.

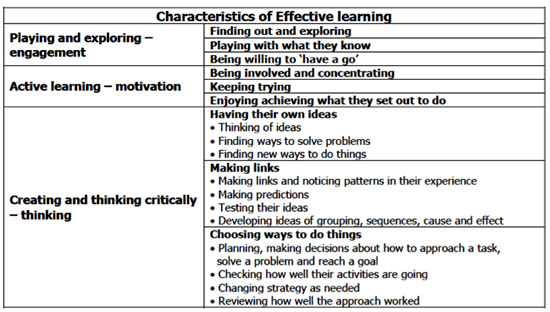

Critical Thinking

This refers to the ability of breaking down a complex problem and analyzing its component parts.

The ability to do that will make it easier to come up with logical solutions to almost any problem. Being able to sort through and organize that pile of smaller chunks of information helps them face problems with ease. It also prevents your child from feeling overwhelmed when a huge barrier is laid out in front of them.

Help your child practice critical thinking by asking them questions. Open-ended questions specifically help them think outside the box and analyze the situation.

Teach them to look into possible reasons why something is the way it is. Why is the sky blue? Why are plants green? Encourage them to be curious and ask questions themselves.

Creative thinking is being able to look at different possible reasons and solutions in the context of problem-solving. It’s coming up with ideas and finding new ways of getting around a problem. Or being open to different ways of looking at an object or scenario.

Creative thinking is best nurtured with activities that involve reflection.

Try getting your child’s viewpoint on topics that may have different answers or reasons for taking place. Get them in the habit of brainstorming ideas, doing story-telling activities, and reading books. All of these help broaden a person’s thinking and flex their creative muscles.

Encourage Independence

It’s important to retain your role as an observer, supporter, or facilitator. Step back and let your kids try out their own solutions. Watch what happens while ensuring their safety and well-being.

As an observer, you encourage independence by stepping back and watching how your child resolves the problem in their own way. It may take longer than it would if you jumped in, but leaving them to their own devices can do a lot for nurturing their skills at problem solving.

Support your child by appreciating and acknowledging their efforts. Create a space where they can freely and effectively express their ideas without fear of judgement. Present them with opportunities to play and solve problems on their own. Encourage them to express themselves by brainstorming activities that they might want to do instead of telling them what to do.

These simple steps of overseeing your child can help them become more independent and be resilient enough to tackle problems on their own.

Here at Early Childhood University , we value the importance of enhancing problem solving skills, creativity and critical thinking. Send your little ones to a school that focuses on a child’s holistic development. Give us a call for more information.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Administration for Children & Families

- Upcoming Events

- Open an Email-sharing interface

- Open to Share on Facebook

- Open to Share on Twitter

- Open to Share on Pinterest

- Open to Share on LinkedIn

Prefill your email content below, and then select your email client to send the message.

Recipient e-mail address:

Send your message using:

Promoting Problem-solving Skills in Young Children

Roselia Ramirez : I'd like to welcome you to the Home Visiting webinar series. We are happy that you have joined us today. The topic for our session is focused on problem-solving and how home visitors can partner with parents to really support its development. Before we get started, we want to tell you a little bit about us and want to have you meet your hosts for today's session.

My name is Roselia Ramirez and I am a senior training and technical assistance specialist at the National Center on Early Childhood Development Teaching and Learning, or DTL for short. I'm happy to be joining you from my home state of Arizona, and I'm going to turn it over to my colleagues and have them introduce themselves. Hey Joyce.

Joyce Escorcia: I am Joyce Escorcia, and thanks everyone for choosing to spend your hour with us. I work alongside Roselia and Sarah at DTL as a senior T and T specialist. You may have seen me in the Coaching Corner webinars and some other places and spaces. Thanks for joining us. We're excited to dig into our topic today. Sarah, do you want to introduce yourself, and share a little bit about yourself?

Sarah Basler: I'm excited to join you all today; you might recognize me as one of the presenters of the Coaching Corner webinar series and my role and work tends to be around coaching and specifically using PBC to support practitioners and even supporting coaches in their PBC practice. I also have a background in pyramid model practices. I'm excited to be here today and talk with you all about problem-solving, which is one of my passions. Thanks so much for having me today.

Roselia: Thanks for joining us, Sarah. It's exciting to see you and to have you as our guest for today on this often-challenging topic for many home visitors as well as parents. Thank you again, and it's so nice to see you. We do probably have some new viewers joining us today. We were wondering if you could start by giving an overview of the Practice-Based Coaching model and then share with our viewers some of the benefits of coaching for a home visitor.

Sarah: Sure. A quick little recap for some of you, and an introduction for others, Practice-Based Coaching or PBC as we call it for short, is a coaching model that when used with fidelity can lead to positive outcomes for children and their families. PBC can be used with anyone, so you can, a coach can support teachers or support home visitors, family childcare providers, or even other coaches. We refer to those that are receiving the coaching as a coachee, to support them to use a set of effective practices. PBC is a content-ready model, which means that any set of practices can be the focus for the middle of the cycle, visual, and so whatever set of practices that you might want to be the focus of coaching can go in the middle there.

The coach and the coachee together identify some strengths and needs related to those effective practices that have been selected for coaching and together they write a goal and an action plan to support that coachee in their implementation of those goals. The coach and the coachee engage in focused observation. The coach will come in and observe the coachee using those effective practices selected in their action plan. Then they meet and reflect about what happened during the focused observation, and the coach will give some feedback, some supportive, and some constructive feedback.

All of these components of PBC fit within a collaborative partnership. PBC occurs in that context, and it's really about a coach and a coachee coming together to work together and support the implementation of those effective practices. When we think about what those benefits might be for a home visitor, a home visitor could share with their coach, challenges that they might be facing related to working with families and together, a coach and the home visitor could talk through maybe some possible solutions or strategies that the home visitor may want to try with the family or support the home visitor in learning a little bit more about a certain set of effective practices.

Sometimes it's really nice to have that support and a colleague to ask your questions and get some ideas. A coach can support a home visitor to grow their home visiting practices. A coach could support them not only around maybe effective practices to try with the, to support the family to use, but could support the home visitor in growing their home visiting practices themselves. Thinking about how to enhance those skills.

Roselia: Thanks, Sarah, I really like the whole notion. The first thing that kind of comes to my mind is this whole idea of having a thought partner. But before we go any further into this topic, and this discussion, if you're just joining the session, we would like to remind you to visit that teal color widget that's at the bottom of your screen. Here's where you can gain access to this participant's guide that you're seeing a little screenshot on your screen now. This resource is intended to be interactive and you're going to hear us reference it and then direct you there during the session for some opportunities for engagement as well as some reflection.

I also want to point out that on the first page of the participant's guide, you're going to find some icons and images that we have been using in our home webinar series, such as the focus on equity segment and this is represented by that little magnifying glass image. I also wanted to mention that not every one of our Home Visiting webinars will have each of the segments in each of the webinars, but just to give you an idea of what those are when you do see them. The other thing we want to do before we go any further is we want to review the learning objectives that we have established for this session.

We have identified and framed the session around two learning goals. First, by the end of the session, we anticipate that you'll be able to describe some essential components of problem-solving, and then second, that you will have some practical strategies and resources that are intended to not only strengthen but nurture problem-solving within that home environment. Now in your participant's guide, we have provided a space for you to reflect and to think about your own learning goals and what you would like to walk away with from this session. Think about that for a moment. What's something that maybe a question that you might have or a type of reflection, something that you would like to walk away with. Take a moment and then jot down your thoughts in your participant's guide.

Joyce: To frame the space that we're in today for our Home Visiting webinar series this year, we've been focusing in on topics that have an impact on social and emotional development. As many of you know, social-emotional development is one of the domains in the Head Start Early Learning and Outcomes Framework, or the ELOF . You can see we have it highlighted here on the slide. When we began the series this year in October, we focused in on the home environment, and then in December, we focused in on relationships. In our last webinar, we really focused in on emotional literacy.

If you missed these webinars, don't worry, you can catch it on Push Play, and you'll have information about that towards the end of our webinar today. For our time today, we're really excited; again, I'm super excited to have my cohost from the Coaching Corner webinar series. I'm excited to be here with Sarah to focus on problem-solving and the practical strategies that we're going to be talking about today. We're really going to be looking at how a home visitor can support and partner with families kind of introduce and nurture that skill within young children. That's really where we're going to be at today.

Again, we wanted to make that connection with the Pyramid Model. While we're not going to go deep into the pyramid, we do want to just make that connection today that the Pyramid Model is a framework of evidence-based practices for promoting young children's social-emotional development. The Pyramid Model builds upon a tiered public health approach by providing universal support to, universal supports for [inaudible]. Animations are going a little wonky on me today. Universal support to all children to promote wellness and then targeted services to those who need more support and then also intensive services for those that need them.

In this webinar, we're going to be focusing in on problem-solving, which is that tier two targeted kind of social-emotional support piece, which we know are essential and important to healthy social development. That's where we're going to be focusing in on today, with, we're thinking about the pyramid. If you want to know more about the pyramid, check out the National Center for Pyramid Model Innovations, or NCPMI . We have links to that within the resource, within your viewer's guide for today. Be sure and check that out as well. We are again super fortunate to have Sarah with us today. We just really want to draw on all of her experience that she's had out in the field and really sharing some of her insight on problem-solving. Sarah, I'm going to pass it over to you.

Sarah: Social competencies like self-regulation, empathy, perspective taking, and problem-solving skills are really foundational to that healthy social-emotional development, and this includes positive interactions like friendship and relationship skills between peers and siblings. Young children really need that support of adults in their lives to help them learn these skills so that they can develop healthy relationships among peers and find ways to really work through social conflicts. As home visitors, you can support this process by really supporting teaching and modeling with families how to help their children develop these skills earlier on.

It can start as young as infants and toddlers. Home visitors can support building these foundational problem-solving and relationship skills that most children can access with adult support and start to use independently as they start to, as they continue to develop these skills. Children, as they become more independent, they'll tend to run into situations in their environment that can lead to frustration or even some challenging behavior.

If parents are intentional and teach children these skills early on in their development, they can become pretty fluent in problem-solving. Then as they learn these skills, they can become more independent and successful with these skills. Their self-esteem will then, in turn, increase, and they will be likely to be able to cope with certain levels of frustration as a result and engage hopefully in less challenging behavior. When they feel confident in these social interactions and are able to problem solve successfully, then we're going to likely see less challenging behavior.

Roselia: Sarah, this is a good place to note that as you get to know your families, you may also discover that there might be some children who struggle, and they don't readily learn these skills through those foundational teaching strategies such as modeling or co-regulation. This might include children with disabilities or suspected delays. Establishing that strong relationship with the parent becomes even more important to get more familiar with and to be aware of the struggles so that you as a home visitor can then explore and use some of those more individualized practices to work on these skills when children need that extra support. We're going to talk some more about that throughout this webinar, but we just thought that would be really important to point that out.

Let's talk a bit more about why problem-solving is important in child development. We know that the earlier that children begin solving those problems, the more ready they are to deal with bigger challenges as they mature. We know that the home is a safe, it's a controlled environment, where parents can direct children as they develop and practice those problem-solving skills. By viewing problems as opportunities to grow, children begin to broaden their understanding while building that confidence that you were talking about.

We also know that when children feel overwhelmed or maybe hopeless, they often, they're not going to attempt to address a problem and that's where some of this challenging behavior for us adults may come up. When they have support, and then adults really support them with that clear formula and some steps for solving problems, they'll feel more confident in their ability to even give it a try. By introducing problem-solving skills at a young age, children learn to think in terms of manageable steps. Sarah, can you share with us how a home visitor might go about this process with families?

Sarah: There are some steps to problem-solving that home visitors can use and introduce to parents and there are some ways that you can support families to incorporate these steps as they encounter social conflict in the home or in socialization. The first is to support children in identifying the problem. This can be simply stating what the problem is out loud and it can make a big difference for children and that even includes infants and toddlers as well as preschool-age children who are feeling stuck. Parents can really think about how to do this in an age-appropriate way to support their child to state what the problem that they're encountering is, such as, your sister doesn't want to play with you, or I see you're having a hard time rolling over, or would you like a turn?

Once the problem has been identified, parents can help their child to think about what some solutions might be to solving their problems. Parents can help to brainstorm possible ways that they might solve that problem. As a home visitor, we can help parents understand that all solutions don't necessarily need to be a good idea, meaning that really just the idea of children coming up with these ideas or sharing some possible solutions. We want to support that process and allow children to share no matter how silly it may sound, and we can support them by offering suggestions to them. The goal is for parents to help their child explore options and the key is to help them do this with creativity and support them to find many different potential solutions because we know that there's not one right way to solve a problem and we want to support children to be able to think of multiple solutions.

Parents can even talk through and help their child identify what the pros and cons of each solution might be. Parents really play this critical role in helping their child identify potential positive and maybe negative consequences for each potential solution they've identified. Once the child has evaluated the possible pros and cons of each solution, the parent can encourage them to pick a solution and try it out and see what happens.

That's where even sometimes those silly solutions that they come up with, it's okay, let them try it out because if it doesn't work, you can support them to try out a different solution. And finally, the last step would be really analyzing or evaluating if it worked. Did this solution that you tried work? Was it, did it solve your problem? And if it doesn't work, you can always come up with a different solution and help them to brainstorm new ones.

Roselia: Thanks Sarah. I think that's a really great way to kind of break down that process and a great way for home visitors to support parents as they're kind of working through that. From your experience as a coach, and then just the various different learning settings that you had the opportunity to work in, why do you think problem-solving is so important?

Sarah: Problem-solving skills give children that independence that they really crave. It gives them agency in their own lives. Even though they may not be able to do this independently right away, when we give children the tools that they need to be able to do this successfully, they're able to navigate interactions with others and it helps to build social competence that they're going to carry with them for the rest of their lives. No matter what the learning environment is that you are in, social interactions are inevitable. They happen all the time. It's important that adults give children the tools that they need and support them to use those tools when they need them so that they become independent and confident in solving these problems when they arise.

Joyce: When Sarah was talking, I said I really love how you made that connection about the importance of parents supporting that, because I think it goes back to what we stated when we started. That about supporting children to become these confident, capable children really does kind of lead into being confident, capable adults who can kind of explore the world around them with all the skills that they need. I think that it just makes a case why this is so important. Because we know that solving problems really is about making choices. As young children develop their problem-solving skills, they build their confidence and we just know that you know, that having all of that, being able to solve problems, figuring things out, really makes them happier, more content, and just independent individuals. That's really what we want.We know when they tackle problems on their own or in a group, they become resilient and persistent. They learn how to look at challenges from a fresh perspective, and therefore, they're confident enough to take more calculated risks and problem-solving is so important in child development.

Again, because we know if we do it and we get it right when they're little, it really turns into this other thing when they become adults that they become confident and capable and are good with taking risk in all kinds of other different ways. Some of you may be wondering why you're here with us, wondering what skills do children need to be successful at problem solving? This is important, like I know it's important. What skills do they need in order to be able to do it well and in order for children to be successful at problem-solving and developing relationships there are a lot of prerequisite skills that are required and needed.

We're going to talk a little bit about that, but we want to open up the Q and A for you guys to say okay, what skills do you think are important for children? What do you think that they might need in order to problem solve? We're going to ask you to pop that into the Q and A, right there, just click on the Q and A widget and put your responses there. We're going to share some of those out. While you guys are kind of thinking and popping ideas into the Q and A, we want to ask Sarah and bring her into the conversation of, Sarah, can you share with participants what some of those, what you think some of those prerequisites could be?

Sarah: For prerequisite skills, as you mentioned Joyce, problem-solving is really complex and it's going to require that a child be able to do many different things at the same time. When we think about children three and up, what they might need to be successful at problem-solving, then you really need to be able to initiate and respond to others. That could be a verbal or a nonverbal interaction or response, and it would vary, of course, based on the child's age or ability. This might look like if a child wants a toy that another child has, it could look like holding out their hand to ask or asking for a turn. A response might look like the other child saying no, I don't want to give you a turn, or pulling the item back to say, I don't want to give you the toy. Children really need to be able to initiate and respond to be successful at problem solving.

Another thing that they need to be able to do is identify emotions in themselves and in others. The reason this is important is because have you ever tried to solve a problem when you're upset? It's really hard. You're not thinking clearly. It's just not going to work. Children need to be able to return themselves to that state of calm before they're able to come up with solutions to their problem, or even to recognize what their problem is. Another step is being able to calm themselves or having an adult support them to calm down.

The next skill might seem obvious, but children really need to be able to identify what the problem is. That could look like a child identifying hey, I've got two apples but there are three siblings here. And what, my problem is I've got two apples, and we don't have enough. Once they've identified the problem, children really need to be able to then come up with possible solutions to solve their problem. That could be that child identifying hey, if I split this apple, we all have some. Or it might be, I don't like apples, so you can have mine.

These skills that I just mentioned are really higher level for maybe preschool-age children, but a home visitor can also support families of infants and toddlers by setting the stage for problem solving. Making sure the environment really promotes interactions with others. Are there opportunities for that child or other children in the home to engage with one another? There usually are, even in routines that we don't think there are, you can build in possible opportunities. Pointing those out for the family, helping them think about what they might do or say and providing, helping support them to provide more opportunities throughout the day.

Another way that a family could support problem-solving in the environment is narrating or pointing out the intentions or what another child might be wanting or needing so that could sound like, “oh, I see Julia crawling towards you. It looks like she wants to play with your ball.” What this does is really builds awareness of the wants and needs and intentions of others. I think that's so important because often I know you've been around children, you know that sometimes it feels like a threat and when we can narrate what's going on, we can frame what's going on for the child so that then they approach it as in a different way.

Of course, it's important to share that if a coach is working with a home visitor to support families to use these practices, a coach can help a home visitor identify what those prerequisite skills are that might need to be taught to the child first, the family or the child to be successful. It's important to note that a coach can be an extra set of eyes. And that, some of the things that I mentioned are coming in on the chat, I'm seeing, or in the Q and A, some people are saying kids need to be able to share, kids need to be able to ask for what they need, kids need to be able to identify the problem, and so it looks like you guys are right in line with what we were talking about. Really having friendship skills is important. Thank you so much for your responses.

Joyce: I feel like folks have a lot of ideas to share about what it takes to problem solve. And again, thank you for all your responses; keep them coming in. We just talked about, there are a lot of things needed for children to be successful at problem-solving and we still see a lot of the responses here we see coming in in the chat. We have Kate and Catrina that talk about regulating emotions. We have Tom that talked about think about possible solutions and then also as adults think about how can we help kind of set them up with possible solutions. Thank you for putting all of those things in there. As you can see, there's a list there added to the list that is coming in the Q and A. All of those things all in mind, problem-solving steps that we talked about and how a home visitor might support the development of this process.

Sarah, just to pop in with a quick question here, when you were talking and explaining the, when you were explaining kind of the why. Like why because it kind of helps to take away that threat aspect of it. As a coach we do that with our coachee or home visitor and do you think that there's some importance or connection then as a home visitor having that knowledge than to be able to have that parallel process of sharing that information with a print of like this is why it's important to narrate kind of that parallel top piece. Do you think that that could also be helpful for a home visitor?

Sarah: Yes, absolutely. I think as adult learners, and when you're working with parents, working with adult learners, it's really important for them to know the why. Why are you telling me to narrate? Pairing the narration is important because it helps children feel less threatened by the other child and you share the intentions. Then it helps make it more, gives the parents the why. Why would I do this? And then they know that the possible impact that using that practice might have. It's really a parallel process. What you would, your coach would use with you, you might also use some of those strategies with the families that you would work with.

Joyce: Yeah, thank you for sharing that. I said it was just when you said that, that light bulb went off, like wow, that's important information to kind of share on both sides, so thank you for that.

Now we're going to just summarize some of those key ideas and practices for home visitors and how they can support some of those problem-solving skills. Again, a lot of things have been coming in through the Q and A. Number one is just to promote healthy relationships, that home visitors can support parents in how they engage with and offer opportunities for young children to work on relationship skills. Sharing and helping and cooperating and comforting and making suggestions about play, even celebrating each other, and creating developmentally appropriate opportunities for practicing those skills throughout the day.

Home visitors can support parents in creating opportunities within the home as well as exploring options where children can practice turn-taking and sharing. Maybe through a socialization activity. Particularly when you're thinking about when there's just one child in the home, parents may have a concern about their child not having opportunities to engage with other children, so that could be a great time to just kind of pause and think about the value they place on peer relationships and how they might be able to provide some of those opportunities for their child. Thinking about some of those being intentional and some might be planning some outdoor activities, some field trips, some going to the park, visiting with their cousins or whatever that aspect.

Just knowing that can also help with thinking about, like, 'Wow, every interaction could be a learning moment, an opportunity to kind of learn and grow these skills.' Thinking about teaching problem-solving steps that earlier we talked about - some steps that home visitors can work through with parents. When it comes to developing problem-solving skills, young children are learning to manage their emotions and behaviors through co-regulation. They're beginning to reason and understand simple consequences. Our role as a home visitor, we have that opportunity to work with parents and support the development of problem-solving.

Problem-solving development at this young age allows children to identify problems, brainstorm possible solutions, and then test those out, test out those appropriate solutions, and then analyze and think about, "Okay, so what kind of results did I get? Did I get what I wanted in the end?" Parents can support children to work through these steps and gain confidence in their ability to work through the problems that they encounter.

Another component would be teaching problem-solving in the moment. Problem-solving is hard work. It is hard work, but a 2-year-old solving problems is hard work for everyone involved sometimes. As home visitors, we have that unique opportunity of supporting this process. We want to build a parent's skill base and their confidence really to help their child use problem-solving steps in the moment. As home visitors can partner with parents to brainstorm ways they can anticipate those social conflicts before they happen. When a problem arises, the parent can anticipate or recognize problems before things can escalate and get out of hand and feel overwhelming or intervene as needed to work through those problem-solving steps that home visitors can support.

How parents individualize strategies they use to provide support, all these skills, really based on the learning kind of style and needs of their child. We know that some children may need the amount of language used to be modified; some children may need visual cues or gestures kind of paired with verbal language; some children may need specific feedback about consequences to really help them learn about the effect of their behavior on the environment really based on the individual needs of that family and the children as well.

Roselia: Thanks for sharing all that, Joyce. That's a lot of great information, and as you were saying all these things that we're doing to support parents or children rather — I think someone mentioned this earlier — about even as adults, problem-solving is difficult for us sometimes. To imagine for children that don't have the words and they're struggling with all these different emotions and wanting to stake their independence, it can really be a tough process.

As home visitors, we're in that unique position to really help support. Thanks for sharing all that. Throughout this webinar, we've really been discussing ways to foster problem-solving skills for all children. Today, in our focus on equity segment, we're going to use our equity lens to take a closer look and really lift up the value of equity in all learning environments as we work with diverse families in our communities.

As home visitors, it is safe to say that we are working with a diverse group of families, and we never want to make any assumptions. Let's reflect on this question: How can a home visitor be sure that they are being culturally responsive to a family's values related to relationships and problem-solving? Think about that because we know it's not a cookie-cutter approach and we know that there are cultures within cultures. It's important that we don't make any assumptions, and thinking about being culturally responsive, how can a home visitor ensure that that is happening?

We'd like for you to take some time and share some of your thoughts with us in the Q and A. While you're doing that, we do have a few suggestions that we would like for you to consider. First, we want to make sure that the skills that you're introducing are culturally relevant to the family that you're working with. It's important to really take the time and think back to the information that you've gathered as you've been developing a relationship with the family. You want to be sure that you're considering the values, beliefs, what's important to them, what's important that, the importance and the goals that they have for their children, and again, not making any assumptions and really asking these types of questions as you're moving through the process.

We also recommend that you take the time to gather input about social problems that the child may face at home or perhaps other settings that they're participating in. Then lastly, although we just mentioned this, we wanted to place an emphasis on the importance of gathering information about the family's values. As you're building those relationships, as you're observing the family, just really asking those questions, and not making assumptions from your perspective but from how the family states it. It's important to remember that problem-solving and how it is approached is not going to look the same for all families. Again, even if you have families that are from the same culture, what works for one family may not work for another. It's important for the suggestions and the strategies to be culturally responsive and respectful of a family's values. Sarah, folks are still entering their thoughts into the Q and A. Is there anything that you would like to add?

Sarah: Those suggestions you gave are great. Something that I think is important is you want to make sure that teaching problem-solving is relevant. You mentioned that, but we want to make sure that it's meeting the needs of the family, like what you're suggesting. Think about, when I think about it from a coach's perspective, this might be an opportunity to support the home visitor to come up with some ideas.

For example, if a home visitor asks the family what kind of social problems are popping up at home, or in their socialization settings with their child, it could be, “Oh, my child is taking toys, and they don't think sharing is important.” What you might do is offer different suggestions, but it might be tricky for a home visitor if they don't value sharing. What else could I offer? That could be where coming to your coach and trying to brainstorm and problem-solve or with your colleagues or your supervisor.

If coaching isn't offered, to come up with some different ideas of what they might offer to that family, what they might suggest they teach their child instead. That could be asking for a turn or asking their sibling to give them a turn when they're finished, so there isn't just one right way to do things, and I think sometimes we forget that even as home visitors, our culture and what we value, we bring that into the environment and what we value isn't the only way. That's where getting the input and what the family values because ultimately, you're there to support them to support their child. Remembering that although your culture is relevant as well when you're there to support the family, you want to think about their values and really incorporate it that way.

Some of the responses that are coming in are pretty much in line with what we just talked about. It's looking very similar, getting input from the family, not making assumptions. I'm seeing finding out what they value, learning about their culture is something new that we didn't mention. Getting the parents' input can be really, really helpful. Thank you for those responses.

Joyce: Thank you, and Sarah, like you said, those responses just keep coming in and we encourage you just to keep sharing and keep thinking about, what we need to do to support families in a way that's culturally responsive.

Now, we want to move into our next portion of our time together, and we want to turn our focus just a bit on looking at how home visitors can support families. We've been talking about this, and that's a great segue into this, so just want to explore that just a little bit more. We want to do that by highlighting the resource, and then you have the link to the resource in your viewer's guide for today.

One resource that was developed by the National Center on Quality Teaching and Learning is “Problem-solving in the Moment.” This is a 15-minute in-service suite developed for preschool classroom teachers to help children problem-solve as they arise or in the moment. We've included a link to those materials in the participant's guide.

The content here really talks about these five steps that support and guide children's behavior to encourage problem-solving in the moment. You'll see that the five steps are here: anticipate, be close, provide support, multiple solutions, and then celebrating the success. We're going to explore each of these steps and relate them to how home visitors can partner with parents to guide their child's behavior at home to problem-solve in the moment. Rosalia is going to help us dig into that a little bit more.

Roselia: Anticipate is the first and very important step of this process. As home visitors, we can really work with parents to try and stay one step ahead of problems by recognizing and being proactive. Home visitors can support parents in sensing some of those changes in a child's behavior, as well as their emotions, and then really starting to pay attention to some of those identifying triggers. Home visitors can also help parents be aware as well as to be ready to activate some of those problem-solving steps that we have been talking about.

Let's move on here and talk about the next step, which is to be close. We know that often parents can be very busy, and they're not always going to be physically close when a problem situation presents itself. What parents can do is to relocate themselves and be near the location when the problem is beginning to occur. That's where it becomes important to start to identify some of those triggers, some of the changes in behaviors that are starting to happen, and then start to relocate.

We want to work with parents to recognize some signs that a problem is about to occur so that they can then move themselves closer to that situation at this stage, rather than when the problem is in full swing. We want parents to know that when they are close, it's an opportunity for them to be able to explore and to begin to provide some support for their child. As a home visitor, you can really support families in beginning to pay attention, starting to recognize, and when to offer some of that proactive or preemptive support and figuring out some of those patterns of the behavior.

Being close, time also provides for families an opportunity to model how to remain calm and then some of those gentle approaches to problem-solving so when the parents are close, they're better able to support and then talk through identifying the problem as well as some of those possible solutions that we've been talking about. They can also support their child in regulating their emotions before they get to that heightened level, and then it's going to be a lot harder for them to be able to calm down. Parents being close also provides that opportunity for them to be able to provide that comfort that might be needed before things just really become too escalated and get out of control. Joyce, tell us a little bit about what this support might look like.

Joyce: One of the things that home visitors can explore with their family when it comes to being close and providing support for their child is knowing what level of support to provide to really ensure there is a teachable moment taking place. Sometimes, that support means helping their child stay near and in proximity to where the problem happens so they can problem-solve effectively. Sometimes, that could mean prompting their child to walk through the problem-solving steps.

It can also mean verbal prompting, like, “Do you remember what to do when baby sister doesn't want to take a turn?” or maybe the parent can involve an older sibling in it if they're available, saying, “Hey, let's ask brother what would you do?” Sometimes it's really when children don't have those verbal skills, support can mean to use like visual cues as well and to prompt, that prompts them perhaps, takes them into those problem-solving steps. It really depends; that level of support depends kind of on the specific needs of their child. Knowing it's okay to kind of try out different levels of support to figure out what's needed.

Now we want to talk about the next step, which is multiple solutions. Like we said, there's a whole bunch of different ways to be right about things, and so there can be situations in which one solution maybe a good solution but we know that it may not always work. As children become older, parents can support problem-solving skills by encouraging their child to generate multiple solutions. Maybe with younger children they're going to need parents to support to generate choices or solutions.

This is going to allow children to begin to grow their own toolbox of solutions to draw from when they encounter problems. The solutions don't need to be complicated and can be as simple as maybe using a timer, waiting patiently, or maybe even flipping a coin. Home visitors can support parents by talking through and really helping parents to determine some solutions they can present and help their child when problem-solving, and when problems arise. Sarah, we just want to tag you in here and ask you, do you have any resources in your toolbox that may support families with identifying solutions at home?

Sarah: There's a great resource from the National Center on Pyramid Model Innovations, and it's called the “Solution Kit.” They have a home edition, and it includes some common solutions to everyday social problems and it comes in multiple languages, which is great. Visual supports can be super helpful for young children and this resource might be something that a home visitor can share with families.

Another great resource for teaching problem-solving is this scripted story, we can be problem solvers at home. This scripted story can be used by the family to help children understand the steps for problem-solving and it includes some scenario cards that you can use with children to help them think about solutions to common social problems that they're going to face, either in the home or the community. Those are two of my favorite resources.

Roselia: I love those, Sarah. Those are actually some of my favorites as well and I really love that they're visual and that they really have been designed to help support in the home environment, because often we see that there is resources for center-based children, but I love that these are specifically designed for the home. We have included the information in your Participant's Guide Resource List, so we want to make sure that you take the time to explore those and think about ways that you can utilize those with families that you might be supporting.

Continuing on and thinking about the five steps that we've been talking about, the last step that we want to talk about is just as important as anticipating a problem and that is celebrating success. Reinforcing a child's success in problem-solving really supports their development as effective problem solvers, and as home visitors, we want to be sure that you share this with parents. They can reinforce that celebrating success. It can be formal, or it can be informal. Some examples of that informal celebration might be things such as a high five, acknowledging that they did a really great job, you can give them a thumbs up, a wink, a verbal praise, or even just a hug.

Just letting them know that you're really proud of how they worked through that particular problem. As home visitors, you can really brainstorm some different options and some of those informal gestures that are culturally appropriate and relevant for their family. Then you can also support them in coming up with some more formal ways to celebrate the success. The important thing here is that we want to make sure that parents are acknowledging when children are working through those problems and that they're becoming much more independent so that children feel accomplished and of course if you recognize it in that positive way, they're going to want to do it again. They're going to feel that appreciation.

We're going to watch a video clip. In this video clip, you're going to notice that the setting is a preschool classroom and that there are two children that have encountered a problem. We want you to take note on how the teacher handles the situation to really engage the children in working through problem-solving. In your participant's guide, you have some space, and we want for you to take some notes and really pay attention to some of the strategies that the teacher is using. It is a classroom; however, think about how this scenario might play out, perhaps in a home between two siblings or even at a group socialization between two children. Let's take a look.

[Video begins]

Teacher 1: Janny, what's the problem? You're getting it to make the fort and it looks like Amy's holding it too. Thanks, Elena for moving so I could get up. So what are we going to do about it? You both want the same block? What are we going to do about it? How are we going to fix the problem? I'm going to hold the block for a minute while you guys help figure it out. What's your idea?

Child 1: [Inaudible]

Teacher 1: You want to play with it over there. Shall we find out what Jammy's idea was? What was your idea, Janny?

Child 2: [Inaudible]

Teacher 1: Oh, and she thinks she needs it for that building. So, you both need this block for two different buildings. Do you want to look for an idea in the basket? Grab the book. See what you can come up with. There's another one over there, right. I think Amy's got the book. What are we going to do? She's looking, so let's play together, so that would be building the same building together.

Take a break, so you just take a break from building. Wait until she's done. One more minute, so she would have it for a minute and then you would have it for a minute. You build with something else, maybe next time. Playing together. You would build it together. Do you want to build together, Janny? Look at Amy's talking to you. Sorry, I just said it and Amy was saying it. Sorry about that, Amy. Here. So Amy, you're going to help Janny build her tower.

Child 1: Let's do this one.

Teacher 1: Excellent. You guys are expert problem solvers.

[Video ends]

Joyce: We see some of the strategies coming through in the Q and A, we'll ask you to keep putting those out there for us, and just want to check in with Rosalia and Sarah to say what did you guys notice anything there about some of those great problem-solving skills that we saw happening?

Sarah: My favorite part of that video is that she really supported those two children to solve their own problem. She gave them support by prompting them to find the materials to help them problem solve. She read through some of the problems with them, or solutions with them, but ultimately the teacher didn't solve the problem for them. And that was really great to see because I think sometimes as adults, we want to be the fixer and in this video the children were really the experts. They were the expert problem solvers here. I thought that was…

Roselia: I agree, Sarah. I really love that and just the anticipation from the teacher, but also having their little solution book that they can kind of, the visual to work through and see they had multiple choices to choose from. That was my favorite part.

Joyce: Yeah, definitely lots to see in that one. I like that one. I think watching the adult and also watching the kids and how they react to that. Sarah, we just want to give you some space as we're kind of wrapping up to hear a little bit more from your coaching experience and just maybe some more tips for supporting home visitors and partnering with families.

Sarah: Sure. It's really important to remember that parents are their children's' best teachers and most children already, most of what children know or what they know when you come into a relationship with that family, has been learned by their parents. As home visitors, when we partner with parents, we really want to set the stage to provide those intentional opportunities for learning within the home setting.

These tips for child size problems that children can solve with the help of their parents or on their own. Here are some tips that you can share with families to set the stage for their child to become problem solvers. One would be to help the child to relax. When children are faced with a problem, they can become upset, frustrated, angry, they might get their feelings hurt or even cry.

This is not the time to try to solve the problem. When the child becomes calm, we want to help them to work through their problem, but when they're at the height of these emotions, that's not the time. We want to regulate, use some calming strategies to get them to calm down. Then we can support them to problem solve. You can support families to understand that supporting children to calm down is a really important step of this process.

We want to make sure that we're giving uninterrupted time. As home visitors you want to partner with parents to help them understand that developing problem-solving skills is complicated and it takes time. Giving them uninterrupted time that's not rushed to talk through and support them to thinking through problems. Also, we want parents to feel like they are a coach. When we're talking about being a coach, we're not talking about home visitors coaching parents but what we mean here is that children at a very young age are still developing these skills.

We want you to work with parents on developing their ability to identify opportunities and support their children through asking questions and helping their children think and share through what maybe these problems and solutions might be. Active listening is a really important part of this process, as parents it can be hard sometimes, we want to throw out our ideas and suggestions but active listening for children is so important.

Here are some strategies that a home visitor can share with families, and we want you to jot down some notes in your participant guide. Encourage parents to withhold from solving those problems for children, so support them to support children and not solve them for them. Support parents in developing questions that they might ask when problems arise. Help parents to identify when they are, their critical solutions to their child is proposing, so try not to judge the solution. Sometimes they may be silly; let them try it out. Provide that active listening. All those strategies, you can remember those that will support families.

Joyce: Definitely, and we've included all of these tips in a handout, and that's part of your participant's guide as well. You may think, "What's my role in supporting some of these practices?" Rosalia, if you want to give maybe one kind of tip to close us out, what do you think that one thing would be regarding the role of the home visitor?

Roselia: I think the important thing, and I think Sarah has kind of really touched on this throughout, is just really taking the time to listen to the family. Finding out what's important to them, and then just kind of being a facilitator if you will — just kind of really asking some of those haunting questions to get the parent to start thinking about some of those steps that we talked about, like anticipating that behavior, looking at problem-solving as an opportunity for learning, and just helping children to really put words to those emotions that sometimes even we as adults struggle with.

I think really being that partner, that reflective partner with the parent, and then providing some of these strategies to help them work through that and again just really seeing it as an opportunity and not necessarily as a behavior that challenges us. Just kind of taking that time to explore with their child and just giving them the words for those emotions to kind of help them become more aware as they kind of go out into the world and face some of those social conflicts if you will. That would be my suggestion.

Joyce: I think that's a great one to leave us with today. Thank you, Sarah, so much for joining us. Thank you everyone here. If you have any questions or anything, drop them in the Q and A. Also, feel free to reach out to us, we have to keep this conversation going, and we will see you guys next time. Thank you.

How young children approach and solve problems is critical to their overall development. Problem-solving supports how young children understand the world around them. It can impact their ability to form relationships as well as the quality of those relationships. Supporting the development of problem-solving skills is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Explore strategies and resources home visitors can use to partner with parents to strengthen and nurture these skills and help children cope with challenges as they arise.

Note: The evaluation, certificate, and engagement tools mentioned in the video were for the participants of the live webinar and are no longer available. For information about webinars that will be broadcast live soon, visit the Upcoming Events section.

Video Attachments

- Webinar Slides (884.13 KB)

- Viewer's Guide (844.2 KB)

« Go to Home Visiting Series

Resource Type: Video

National Centers: Early Childhood Development, Teaching and Learning

Age Group: Infants and Toddlers

Audience: Home Visitors

Series: Home Visiting Series

Last Updated: April 5, 2024

- Privacy Policy

- Freedom of Information Act

- Accessibility

- Disclaimers

- Vulnerability Disclosure Policy

- Viewers & Players

The Importance of Problem Solving and How to Teach it to Kids

FamilyEducation Editorial Staff

Teach your kids to be brilliant problem solvers so they can shine.

We get so lost as parents with all the demands to do more for our children—get better grades, excel at extracurricular activities, have good relationships—that we may be overlooking one of the essential skills they need: problem-solving.

More: A Parent’s Guide to Conscious Discipline

In a Harvard Business Review study about the skills that influence a leader's success, problem-solving ranked third out of 16.

Whether you want your child to get into an Ivy League school, have great relationships, or to be able to take care of the thousands of frustrating tasks that come with adulting, don't miss this significant super-power that helps them succeed.

Our kids face challenges daily when it comes to navigating sibling conflict, a tough math question, or negative peer pressure. Our job as parents or teachers is not to solve everything for them —it is to teach them how to solve things themselves. Using their brains in this way is the crucial ability needed to become confident, smart, and successful individuals.

And the bonus for you is this: instead of giving up or getting frustrated when they encounter a challenge, kids with problem-solving skills manage their emotions, think creatively and learn persistence.

With my children (I have eight), they often pushed back on me for turning the situation back on them to solve, but with some gentle nudging, the application of many tools, and some intriguing conversations, my kids are unbeatable.

Here are some of the best, research-based practices to help your child learn problem-solving so they can build smarter brains and shine in the world:

Don’t have time to read now? Pin it for later:

1. Model Effective Problem-Solving

When you encounter a challenge, think out loud about your mental processes to solve difficulties. Showing your children how you address issues can be done numerous times a day with the tangible and intangible obstacles we all face.

2. Ask for Advice

Ask your kids for advice when you are struggling with something. Your authenticity teaches them that it's common to make mistakes and face challenges.

When you let them know that their ideas are valued, they'll gain the confidence to attempt solving problems on their own.

3. Don't Provide The Answer—Ask More Questions

By not providing a solution, you are helping them to strengthen their mental muscles to come up with their ideas.

At the same time, the task may be too big for them to cognitively understand. Break it down into small steps, and either offer multiple solutions from which they can choose, or ask them leading questions that help them reach the answers themselves.

4. Be Open-Minded

This particular point is critical in building healthy relationships. Reliable partners can hold their values and opinions while also seeing the other's perspective. And then integrate disparate views into a solution.

Teach them to continually ask, "What is left out of my understanding here?"

High-performing teams in business strive for diversity—new points of view and fresh perspectives to allow for more creative solutions. Children need to be able to assess a problem outside of immediate, apparent details, and be open to taking risks to find a better, more innovative approach. Be willing to take on a new perspective.

5. Go Out and Play

It may seem counter-intuitive, but problems get solved during play according to research.

See why independent play is vital for raising empowered children here .

Have you ever banged around an idea in your head with no solution? If so, it's time to get out of your mind and out to play.

Tech companies understand this strategy (I know, I worked at one), by supplying refreshing snacks and ping pong tables and napping pods. And while they have deadlines to meet, they don't micromanage the thinking of their employees.

Offer many activities that will take your child’s mind off of the problem so they can refuel and approach things from a fresh perspective.

Let them see you fail, learn, and try again. Show your child a willingness to make mistakes. When they are solving something, as tricky as it may be, allow your child to struggle, sometimes fail and ultimately learn from experiencing consequences.

Problems are a part of life. They grow us to reach our highest potential. Every problem is there not to make your child miserable, but to lead them closer to their dreams.

Tami Green, America’s most respected life coach, has received magical endorsements by experts from Baylor University and the past president of the American Psychiatric Association. She received her coaching certification from Oprah's enchanting life coach, Dr. Martha Beck. She is a brilliant coach who has helped thousands achieve an exhilarated life through her coaching, classes, and conferences. To see more tips like these, visit her website and join her self-help community here .

About FamilyEducation's Editorial Team

Subscribe to family education.

Your partner in parenting from baby name inspiration to college planning.

- Alzheimer’s Disease: A Comprehensive Overview and Latest Research Insights

- Dementia Prevention: Effective Strategies for Brain Health

- Senior Cognitive Function: Exploring Strategies for Mental Sharpness

- Neuroprotection: Strategies and Practices for Optimal Brain Health

- Aging Brain Health: Expert Strategies for Maintaining Cognitive Function

- Screen Time and Children’s Brain Health: Key Insights for Parents

- Autism and Brain Health: Unraveling the Connection and Strategies

- Dopamine and Brain Health: Crucial Connections Explained

- Serotonin and Brain Health: Uncovering the Connection

- Cognitive Aging: Understanding Its Impact and Progression

- Brain Fitness: Enhancing Cognitive Abilities and Mental Health

- Brain Health Myths: Debunking Common Misconceptions

- Brain Waves: Unlocking the Secrets of the Mind’s Signals

- Brain Inflammation: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment Options

- Neurotransmitters: Unlocking the Secrets of Brain Chemistry

- Neurogenesis: Unraveling the Secrets of Brain Regeneration

- Mental Fatigue: Understanding and Overcoming Its Effects

- Neuroplasticity: Unlocking Your Brain’s Potential

- Brain Health: Essential Tips for Boosting Cognitive Function

- Brain Health: A Comprehensive Overview of Brain Functions and Its Importance Across Lifespan

- An In-depth Scientific Overview of Hydranencephaly

- A Comprehensive Overview of Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome (PTHS)

- An Extensive Overview of Autism

- Navigating the Brain: An In-Depth Look at The Montreal Procedure

- Gray Matter and Sensory Perception: Unveiling the Nexus

- Decoding Degenerative Diseases: Exploring the Landscape of Brain Disorders

- Progressive Disorders: Unraveling the Complexity of Brain Health

- Introduction to Embryonic Stem Cells

- Memory Training: Enhance Your Cognitive Skills Fast

- Mental Exercises for Kids: Enhancing Brain Power and Focus

- Senior Mental Exercises: Top Techniques for a Sharp Mind

- Nutrition for Aging Brain: Essential Foods for Cognitive Health

- ADHD and Brain Health: Exploring the Connection and Strategies

- Pediatric Brain Disorders: A Concise Overview for Parents and Caregivers

Child Cognitive Development: Essential Milestones and Strategies

- Brain Development in Children: Essential Factors and Tips for Growth

- Brain Health and Aging: Essential Tips for Maintaining Cognitive Function

- Pediatric Neurology: Essential Insights for Parents and Caregivers

- Nootropics Forums: Top Online Communities for Brain-Boosting Discussion

- Brain Health Books: Top Picks for Boosting Cognitive Wellbeing

- Nootropics Podcasts: Enhance Your Brainpower Today

- Brain Health Webinars: Discover Essential Tips for Improved Cognitive Function

- Brain Health Quizzes: Uncovering Insights for a Sharper Mind

- Senior Brain Training Programs: Enhance Cognitive Abilities Today

- Brain Exercises: Boost Your Cognitive Abilities in Minutes

- Neurofeedback: A Comprehensive Guide to Brain Training

- Mood Boosters: Proven Methods for Instant Happiness

- Cognitive Decline: Understanding Causes and Prevention Strategies

- Brain Aging: Key Factors and Effective Prevention Strategies

- Alzheimer’s Prevention: Effective Strategies for Reducing Risk

- Gut-Brain Axis: Exploring the Connection Between Digestion and Mental Health

- Meditation for Brain Health: Boost Your Cognitive Performance

- Sleep and Cognition: Exploring the Connection for Optimal Brain Health

- Mindfulness and Brain Health: Unlocking the Connection for Better Wellness

- Brain Health Exercises: Effective Techniques for a Sharper Mind

- Brain Training: Boost Your Cognitive Performance Today

- Cognitive Enhancers: Unlocking Your Brain’s Full Potential

- Neuroenhancers: Unveiling the Power of Cognitive Boosters

- Mental Performance: Strategies for Optimal Focus and Clarity

- Memory Enhancement: Proven Strategies for Boosting Brainpower

- Cognitive Enhancement: Unlocking Your Brain’s Full Potential

- Children’s Brain Health Supplements: Enhancing Cognitive Development

- Brain Health Supplements for Seniors: Enhancing Cognitive Performance and Memory

- Oat Straw Benefits

- Nutrition for Children’s Brain Health: Essential Foods and Nutrients for Cognitive Development

- Nootropic Drug Interactions: Essential Insights and Precautions

- Personalized Nootropics: Enhance Cognitive Performance the Right Way

- Brain Fog Remedies: Effective Solutions for Mental Clarity

- Nootropics Dosage: A Comprehensive Guide to Optimal Use

- Nootropics Legality: A Comprehensive Guide to Smart Drugs Laws

- Nootropics Side Effects: Uncovering the Risks and Realities

- Nootropics Safety: Essential Tips for Smart and Responsible Use

- GABA and Brain Health: Unlocking the Secrets to Optimal Functioning

- Nootropics and Anxiety: Exploring the Connection and Potential Benefits

- Nootropics for Stress: Effective Relief & Cognitive Boost

- Nootropics for Seniors: Enhancing Cognitive Health and Well-Being

- Nootropics for Athletes: Enhancing Performance and Focus

- Nootropics for Students: Enhance Focus and Academic Performance

- Nootropic Stacks: Unlocking the Power of Cognitive Enhancers

- Nootropic Research: Unveiling the Science Behind Cognitive Enhancers

- Biohacking: Unleashing Human Potential Through Science

- Brain Nutrition: Essential Nutrients for Optimal Cognitive Function

- Synthetic Nootropics: Unraveling the Science Behind Brain Boosters

- Natural Nootropics: Unlocking Cognitive Enhancements through Nature

- Brain Boosting Supplements: Enhancing Cognitive Performance Naturally

- Smart Drugs: Enhancing Cognitive Performance and Focus

- Concentration Aids: Enhancing Focus and Productivity in Daily Life

- Nootropics: Unleashing Cognitive Potential and Enhancements

- Best Nootropics 2024

- Alpha Brain Review 2023

- Neuriva Review

- Neutonic Review

- Prevagen Review

- Nooceptin Review

- Nootropics Reviews: Unbiased Insights on Brain Boosters

- Phenylpiracetam: Unlocking Cognitive Enhancement and Brain Health

- Modafinil: Unveiling Its Benefits and Uses

- Racetams: Unlocking Cognitive Enhancement Secrets

- Adaptogens for Brain Health: Enhancing Cognitive Function Naturally

- Vitamin B for Brain Health: Unveiling the Essential Benefits

- Caffeine and Brain Health: Unveiling the Connection

- Antioxidants for Brain: Enhancing Cognitive Function and Health

- Omega-3 and Brain Health: Unlocking the Benefits for Cognitive Function

- Brain-Healthy Foods: Top Picks for Boosting Cognitive Function

- Focus Supplements: Enhance Concentration and Mental Clarity Today

Child cognitive development is a fascinating and complex process that entails the growth of a child’s mental abilities, including their ability to think, learn, and solve problems. This development occurs through a series of stages that can vary among individuals. As children progress through these stages, their cognitive abilities and skills are continuously shaped by a myriad of factors such as genetics, environment, and experiences. Understanding the nuances of child cognitive development is essential for parents, educators, and professionals alike, as it provides valuable insight into supporting the growth of the child’s intellect and overall well-being.

Throughout the developmental process, language and communication play a vital role in fostering a child’s cognitive abilities . As children acquire language skills, they also develop their capacity for abstract thought, reasoning, and problem-solving. It is crucial for parents and caregivers to be mindful of potential developmental delays, as early intervention can greatly benefit the child’s cognitive development. By providing stimulating environments, nurturing relationships, and embracing diverse learning opportunities, adults can actively foster healthy cognitive development in children.

Key Takeaways

- Child cognitive development involves the growth of mental abilities and occurs through various stages.

- Language and communication are significant factors in cognitive development , shaping a child’s ability for abstract thought and problem-solving.

- Early intervention and supportive environments can play a crucial role in fostering healthy cognitive development in children.

Child Cognitive Development Stages

Child cognitive development is a crucial aspect of a child’s growth and involves the progression of their thinking, learning, and problem-solving abilities. Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget developed a widely recognized theory that identifies four major stages of cognitive development in children.

Sensorimotor Stage

The Sensorimotor Stage occurs from birth to about 2 years old. During this stage, infants and newborns learn to coordinate their senses (sight, sound, touch, etc.) with their motor abilities. Their understanding of the world begins to develop through their physical interactions and experiences. Some key milestones in this stage include object permanence, which is the understanding that an object still exists even when it’s not visible, and the development of intentional actions.

Preoperational Stage

The Preoperational Stage takes place between the ages of 2 and 7 years old. In this stage, children start to think symbolically, and their language capabilities rapidly expand. They also develop the ability to use mental images, words, and gestures to represent the world around them. However, their thinking is largely egocentric, which means they struggle to see things from other people’s perspectives. During this stage, children start to engage in pretend play and begin to grasp the concept of conservation, recognizing that certain properties of objects (such as quantity or volume) remain the same even if their appearance changes.

Concrete Operational Stage

The Concrete Operational Stage occurs between the ages of 7 and 12 years old. At this stage, children’s cognitive development progresses to more logical and organized ways of thinking. They can now consider multiple aspects of a problem and better understand the relationship between cause and effect . Furthermore, children become more adept at understanding other people’s viewpoints, and they can perform basic mathematical operations and understand the principles of classification and seriation.

Formal Operational Stage

Lastly, the Formal Operational Stage typically begins around 12 years old and extends into adulthood. In this stage, children develop the capacity for abstract thinking and can consider hypothetical situations and complex reasoning. They can also perform advanced problem-solving and engage in systematic scientific inquiry. This stage allows individuals to think about abstract concepts, their own thought processes, and understand the world in deeper, more nuanced ways.

By understanding these stages of cognitive development, you can better appreciate the complex growth process that children undergo as their cognitive abilities transform and expand throughout their childhood.

Key Factors in Cognitive Development

Genetics and brain development.

Genetics play a crucial role in determining a child’s cognitive development. A child’s brain development is heavily influenced by genetic factors, which also determine their cognitive potential , abilities, and skills. It is important to understand that a child’s genes do not solely dictate their cognitive development – various environmental and experiential factors contribute to shaping their cognitive abilities as they grow and learn.

Environmental Influences

The environment in which a child grows up has a significant impact on their cognitive development. Exposure to various experiences is essential for a child to develop essential cognitive skills such as problem-solving, communication, and critical thinking. Factors that can have a negative impact on cognitive development include exposure to toxins, extreme stress, trauma, abuse, and addiction issues, such as alcoholism in the family.

Nutrition and Health

Maintaining good nutrition and health is vital for a child’s cognitive development. Adequate nutrition is essential for the proper growth and functioning of the brain . Key micronutrients that contribute to cognitive development include iron, zinc, and vitamins A, C, D, and B-complex vitamins. Additionally, a child’s overall health, including physical fitness and immunity, ensures they have the energy and resources to engage in learning activities and achieve cognitive milestones effectively .

Emotional and Social Factors

Emotional well-being and social relationships can also greatly impact a child’s cognitive development. A supportive, nurturing, and emotionally healthy environment allows children to focus on learning and building cognitive skills. Children’s emotions and stress levels can impact their ability to learn and process new information. Additionally, positive social interactions help children develop important cognitive skills such as empathy, communication, and collaboration.

In summary, cognitive development in children is influenced by various factors, including genetics, environmental influences, nutrition, health, and emotional and social factors. Considering these factors can help parents, educators, and policymakers create suitable environments and interventions for promoting optimal child development.

Language and Communication Development

Language skills and milestones.

Children’s language development is a crucial aspect of their cognitive growth. They begin to acquire language skills by listening and imitating sounds they hear from their environment. As they grow, they start to understand words and form simple sentences.

- Infants (0-12 months): Babbling, cooing, and imitating sounds are common during this stage. They can also identify their name by the end of their first year. Facial expressions play a vital role during this period, as babies learn to respond to emotions.

- Toddlers (1-3 years): They rapidly learn new words and form simple sentences. They engage more in spoken communication, constantly exploring their language environment.

- Preschoolers (3-5 years): Children expand their vocabulary, improve grammar, and begin participating in more complex conversations.

It’s essential to monitor children’s language development and inform their pediatrician if any delays or concerns arise.

Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal communication contributes significantly to children’s cognitive development. They learn to interpret body language, facial expressions, and gestures long before they can speak. Examples of nonverbal communication in children include:

- Eye contact: Maintaining eye contact while interacting helps children understand emotions and enhances communication.