Overview of Alcohol Use Disorder

Information & authors, metrics & citations, view options, current u.s. rates of alcohol consumption, binge drinking, heavy drinking, and aud, adverse consequences of aud, neurobiology of aud, etiology of aud.

Current Treatments for AUD

Psychosocial treatments, pharmacological treatments, fda-approved medications, disulfiram., naltrexone., acamprosate., off-label medications, topiramate., gabapentin., promising medications that require further study, psychedelic drugs., phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors., precision treatments, conclusions, information, published in.

- Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

- Psychopharmacology

Competing Interests

Funding information, export citations.

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download. For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu .

| Format | |

|---|---|

| Citation style | |

| Style | |

To download the citation to this article, select your reference manager software.

There are no citations for this item

View options

Login options.

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Purchase Options

Purchase this article to access the full text.

PPV Articles - American Journal of Psychiatry

Not a subscriber?

Subscribe Now / Learn More

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR ® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).

Share article link

Copying failed.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

Next article, request username.

Can't sign in? Forgot your username? Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

Create a new account

Change password, password changed successfully.

Your password has been changed

Reset password

Can't sign in? Forgot your password?

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password.

Your Phone has been verified

As described within the American Psychiatric Association (APA)'s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences. Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Alcohol use

Alcohol use is a major risk factor for death and disability worldwide. In some countries, it is the number one risk factor for men.

Photo by Chuttersnap, Unsplash.

On this page:

How much alcohol is safe to drink.

The risks of drinking alcohol depend on age, local disease patterns, and underlying health conditions:

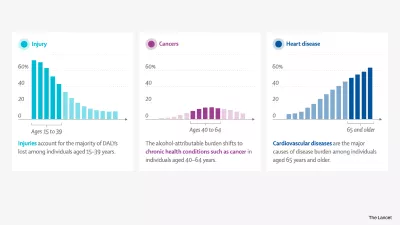

- For young adults ages 15–39 , there are no health benefits to drinking alcohol, only health risks.

- For people over age 40 , drinking a small amount of alcohol may provide some health benefits.

Young people tend to experience a higher rate of injuries as a result of alcohol use, leading to an increase in death and disability for that age group.

For older adults without underlying health issues, having 1-2 standard drinks per day may reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, and diabetes. However, overconsuming alcohol can lead to additional health problems, like liver cirrhosis and some cancers.

On a global scale, the impact of drinking alcohol varies by age

Relative proportions of global disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for causes associated with alcohol use, by cause and age (2020)

IHME & The Lancet infographic: Drinking alcohol has significant health risks for young people, small amounts may be beneficial for some older adults

Dr. Emmanuela Gakidou, Professor of Health Metrics Science

“Our message is simple: young people should not drink, but older people may benefit from drinking small amounts. While it may not be realistic to think young adults will abstain from drinking, we do think it’s important to communicate the latest evidence so that everyone can make informed decisions about their health.”

Why isn’t there a scientific consensus about safe levels of alcohol use?

The patterns for alcohol use and its health impacts are specific to each region of the world and vary depending on the age of the consumer and their overall health status. This results in different recommendations for alcohol consumption. For example:

- In central sub-Saharan Africa, 15% of alcohol-related health risks for those aged 55+ were due to tuberculosis, leading to a recommendation of less than half a standard drink per day.

- By contrast, in North Africa and the Middle East, around 1% of alcohol-related health risks were due to tuberculosis, reflected in a recommendation of about 1 standard drink per day.

There is also some disagreement in the scientific community about the effects of alcohol on cardiovascular disease in individuals over 65. Some studies suggest that small amounts of alcohol may offer protection from cardiovascular disease, while other studies show that alcohol may contribute to it.

Always be sure to consult a health care professional for individual recommendations based on your personal health risks.

Alcohol use is a prominent health risk.

What is the disease burden of alcohol use?

In 1990, high alcohol use was the 15th most relevant risk factor for deaths worldwide; in 2021, it has risen to the 10th most relevant risk factor , responsible for over 1.8 million deaths from various alcohol-attributable causes.

Men are disproportionately prone to health problems stemming from alcohol use, and Eastern Europe in particular is disproportionately affected by alcohol use disorders. Excessive alcohol consumption can lead to several serious health conditions, including:

- Cirrhosis of the liver

- Fetal alcohol syndrome

- Chronic illnesses such as heart disease, stroke, and some cancers

- Interpersonal violence, self-harm (suicide), drunk driving – related injuries, and other unintentional injuries

Researchers Dr. Emmanuela Gakidou, Dana Bryzaka, and Marissa Reitsma discuss key findings from an analysis published in The Lancet and what alcohol consumption recommendations should be made based on age and location.

News and events

The curious case of japan's alcohol contest.

Is alcohol good for your heart? It’s complicated, despite new insights

Urgent action is needed on alcohol harm in nigeria, 9/14/2022: nfl, us open, mlb, gakidou, usfs.

Subscribe to our newsletter

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

Volume 40 Issue 3 November 12, 2020

Epidemiology of Recovery From Alcohol Use Disorder

Part of the Topic Series: Recovery From Alcohol Use Disorder

Jalie A. Tucker, 1 Susan D. Chandler, 1 and Katie Witkiewitz 2

1 Department of Health Education and Behavior and the Center for Behavioral Economic Health Research, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida

2 Department of Psychology and the Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse, and Addictions, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico

Almost one-third of the U.S. population meets alcohol use disorder (AUD) criteria on a lifetime basis. This review provides an overview of recent research on the prevalence and patterns of alcohol-related improvement and selectively reviews nationally representative surveys and studies that followed risk groups longitudinally with a goal of informing patients with AUD and AUD researchers, clinicians, and policy-makers about patterns of improvement in the population. Based on the research, alcohol use increases during adolescence and early adulthood and then decreases beginning in the mid-20s across the adult life span. Approximately 70% of persons with AUD and alcohol problems improve without interventions (natural recovery), and fewer than 25% utilize alcohol-focused services. Low-risk drinking is a more common outcome in untreated samples, in part because seeking treatment is associated with higher problem severity. Sex differences are more apparent in help-seeking than recovery patterns, and women have lower help-seeking rates than men. Whites are proportionately more likely to utilize services than are Blacks and Hispanics. Improving recovery rates will likely require offering interventions outside of the health care sector to affected communities and utilizing social networks and public health tools to close the longstanding gap between need and utilization of AUD-focused services.

Introduction

Substance use disorder (SUD) is among the most prevalent mental health disorders in the United States and in general clinical practice, with 7% of the U.S. population age 12 and older (19.7 million people) having an SUD of some kind in 2018. 1 Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is the most prevalent SUD, with 5% of persons age 12 and older reporting AUD in 2018. 1 Of persons with an SUD in 2018, and excluding those with a tobacco use disorder, 60% had AUD, 27% had an illicit drug use disorder, and 13% had disorders involving alcohol and illicit drugs. 1 On a lifetime basis, almost one-third of persons in the United States meet criteria for AUD. 2 In addition to the high AUD prevalence, many more individuals engage in risky drinking or experience alcohol-related negative consequences that fall short of meeting clinical diagnostic criteria for AUD. 3 Thus, harmful alcohol use is a major public health problem, costing the United States approximately $250 billion per year, and it is the third leading cause of preventable death. 4

Most individuals who develop an AUD or have subclinical alcohol-related problems will reduce or resolve their problem on their own or with assistance from professional alcohol treatment or mutual help groups. 5-9 The epidemiology of this robust phenomenon is the focus of this article. After initial consideration of complexities involved in defining improvement in alcohol-related problems, which is discussed in depth by Witkiewitz et al., 10 this article describes the prevalence and heterogeneity of pathways to recovery and examines relationships between patterns of seeking help for and improvements in alcohol-related problems. Then, the topic is examined from a life span developmental perspective, which is less well-researched and involves relationships among age-related rates of problem onset, reduction, and persistence. The final section discusses differences in the overall patterns previously discussed as a function of gender and race/ethnicity. Emphasis is placed on illustrative recent findings. Earlier work is covered in prior literature. 11,12

Defining Improvement in Alcohol-Related Problems

As discussed by Witkiewitz et al., 10 the conceptualization and measurement of improvements among persons with AUD and the constellation of improvements that define “recovery” have been debated for decades and continue to evolve. Clinical diagnostic criteria for AUD are offered by the American Psychiatric Association’s fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) 3 and the World Health Organization, 13 with the former predominating in the United States. Numerous reputable organizations offer definitions of low- and high-risk drinking practices 4,14 as well as AUD recovery or remission. 15 These various criteria have been revised over time as research evidence has accumulated, generally in the direction of recognizing that alcohol consumption and AUD occur on severity continua. Furthermore, most individuals who engage in harmful alcohol use either do not meet AUD criteria or meet criteria for a mild disorder characterized by lower levels of symptomology. 16

Characterizations of improvement in alcohol-related problems have correspondingly become more nuanced over time in recognition of the heterogeneity of pathways, processes, and outcomes relevant to understanding how people reduce or resolve alcohol-related problems. 10 The term “recovery” is generally reserved for broad-based, sustained improvements in drinking practices and other areas of functioning adversely affected by drinking. Therefore, this article uses the term “recovery” to refer to a broadly conceived process resulting in sustained improvements in multiple domains, and uses the term “remission” to refer to more limited improvements in specific symptoms or problem behaviors (e.g., drinking practices). This is in line with the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism’s (NIAAA) recent definition of recovery from AUD as distinct from remission from AUD, defined symptomatically based on DSM‑5 criteria, or cessation of heavy drinking without characterizing the presence or absence of other symptoms or improvements. It also is consistent with other recovery definitions, including those from the recovery community or patient perspectives, that encompass improved well-being and functioning and are not limited to attainment of abstinence or stable low-risk drinking. 8,17

It is also important to acknowledge the association of the term “recovery” with Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and other mutual support groups. Even though the term is widely used in the clinical literature, many persons attempting to resolve their alcohol problems do not identify with being in recovery 8 and reject clinical labels indicative of AUD, especially those individuals attempting to resolve a drinking problem on their own. 9 Moreover, salutary improvements can occur in circumscribed areas of alcohol-related dysfunction, and reductions in drinking can contribute to improved health and well-being even if ongoing drinking falls short of traditional definitions of recovery that emphasize abstinence as a required element. 18

As discussed by Witkiewitz and Tucker, 16 a core issue debated for decades is the extent to which drinking practices should be central to defining improvement or recovery. Early writings regarded sustained abstinence as the hallmark of recovery among persons with severe alcohol problems who had repeatedly been unable to limit their drinking or abstain. 19 Newer clinical diagnostic systems such as DSM‑5 emphasize development of tolerance and physical dependence and drinking in harmful ways and under conditions that increase risk for adverse consequences. 3 Drinking practices are not a criterion in accepted diagnostic systems for AUD, including DSM‑5, and most schemes define recovery based on symptom reduction, improved functioning, and well-being and are not heavily focused on drinking practices per se. Yet, the large treatment outcome literature concerned with promoting recovery has relied heavily on drinking practices as the major outcome metric, typically by using quantity-frequency criteria considered indicative of higher-risk drinking practices (any occasions of more than 14 drinks weekly or more than five drinks daily for men; more than seven drinks weekly or more than four drinks daily for women in the past year). 4,14

Recent work, however, has shown that such consumption-based thresholds lack sensitivity and specificity for predicting problems related to drinking and do not differentiate individuals based on measures of health, functioning, and well-being. 20,21 Improvements in functioning and life circumstances are considered central features of recovery in many models, including AA, but assessment of these domains is a relatively recent development, primarily evident in clinical research. 18,21 It is generally lacking in survey research that has provided the bulk of epidemiological data on population patterns of alcohol-related improvement, so this body of work only partially addresses the multiple domains considered important for investigating recovery, broadly defined.

A second core issue is that improvement in alcohol-related problems, including recovery from AUD, is a dynamic process of behavior change. Thus, longitudinal studies provide superior information to cross-sectional studies with retrospective assessments of drinking status, although the latter are common in the literature. Cross-sectional surveys have utility if they employ sound retrospective measures of past drinking status, but this is another qualification of the current epidemiological database on alcohol-related improvement and recovery. Longitudinal research has become more common in recent years. However, the intervals over which repeated measures are obtained rarely exceed 3 to 5 years, although there are notable exceptions with follow-ups of 8 to 10 years or more. 22-24 Following large nationally representative samples for decades would be ideal, but the inevitable limitations on research resources have resulted in a collective body of work that generally comprises large representative studies that are cross-sectional or have short-term (e.g., 1 year) follow-ups. Studies with longer-term follow-ups tend to employ smaller, less representative samples. These core issues should be kept in mind when considering the epidemiology of improvements in alcohol-related problems, including recovery from AUD, as discussed next.

Recovery Pathways and Relationships Between Help-Seeking and Drinking-Related Outcomes

Population-based survey research conducted over many decades has consistently revealed the following patterns with respect to improvements in alcohol-related problems:

- The majority of individuals who develop AUD reduce or resolve their problem over time. 7,8,25 Rates of improvement vary widely depending on features of the research, such as the intervals over which drinking status was assessed (e.g., lifetime basis, shorter-term assessment based on a year or more); demographic characteristics, problem severity, and help-seeking status of respondents; and how improvement or recovery/remission was measured. But improvement over time is a reliable pattern and one that argues against a view of AUD as an inevitably progressive disease process.

- Seeking help for drinking problems from professional treatment or community and peer resources such as mutual help groups is uncommon, 1,26 and a large gap persists between population need and service utilization. Most surveys indicate that less than 25% of persons in need utilize alcohol-focused helping resources.

- The great majority of persons who resolve their drinking problems do so without interventions, and such “natural recoveries” are the dominant pathway to problem resolution. Survey research has typically found that more than 70% of problem resolutions occur outside the context of treatment. 7,9

- Stable low-risk drinking (moderation) is a relatively more common outcome in untreated samples, in part because seeking treatment is associated with higher problem severity, 7,12 and most treatment programs emphasize abstinence.

For example, Fan and colleagues 7 reported on the past-year prevalence of AUD recovery in the United States by using data from the NIAAA-funded 2012–2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC-III) 2 and DSM‑5 diagnostic criteria. 3 Survey respondents who met AUD criteria prior to the past year ( n = 7,785) were assessed with respect to their current (past-year) AUD and risk drinking status. Drinking status was determined based on quantity-frequency criteria considered indicative of higher-risk drinking practices and DSM‑5 AUD symptom counts. Measures of functioning and well-being were not collected.

Only 34% of respondents had persistent AUD, and most respondents had some degree of problem reduction; 16% achieved abstinence without symptoms, and 18% achieved low-risk drinking without symptoms. In addition, only 23% of the Fan et al. sample reported having ever received alcohol treatment, and those who did tended to fall into the persistent AUD (26%) or abstinent without symptoms (43%) outcome groups that generally are associated with higher problem severity. 7 In contrast, among the subset of respondents who reported abstinence or low-risk drinking without symptoms, 87% of those who reported low-risk drinking without symptoms were never treated, and only 12% were treated. An additional 15% of the sample reported low-risk drinking with symptoms, and 15% reported high-risk drinking without symptoms. 7 This is a refinement in outcome measurement compared to earlier surveys and illustrates the heterogeneity of recovery-relevant outcomes even in the absence of assessment of functioning and well-being.

This illustrative representative sample survey, among others, 8,9 reveals a more optimistic and variable view of recovery pathways and outcomes than suggested by early research using treatment samples, which emphasized the chronic, relapsing nature of alcohol problems and the difficulty of maintaining remission. Population data indicate that, even though alcohol problems are prevalent, most affected individuals have less serious problems than the minority who seek treatment, and many improve on their own, including achieving stable abstinence or low-risk drinking without problems.

In contrast to these encouraging findings concerning rates of improvement, population research on the prevalence and patterns of help-seeking for alcohol-related problems indicates that the gap between need and service utilization is large and chronic. This is the case even though alcohol-related services have improved and expanded considerably over the past several decades 27,28 and reliably yield benefits for a majority of recipients. Among the 25% or fewer who seek care, sources of care span the professional, community, and peer-helping sectors. Within the professional sector, care is diffused through mental health, medical, and community services systems, and only a minority receive alcohol-focused services from qualified programs or professionals. 8,27

Prevalence estimates for utilization of different types of alcohol services are not reliably available for several reasons. For example, specialty treatment programs are often addiction-oriented and not alcohol-specific, most include mutual help group participation as a program requirement, and the anonymity principle of mutual help groups deters determination of utilization rates apart from treatment. Nevertheless, membership estimates for AA (2.1 million members worldwide, including 1.3 million U.S. residents; https:// www.aa.org ) suggest that AA participation is relatively widespread. Comparable membership data are not available for other mutual help groups such as Self-Management and Recovery Training (SMART Recovery), which holds more than 3,000 meetings per week worldwide ( https://www.smartrecovery.org/ ), and LifeRing Secular Recovery, which offers more than 140 face-to-face meetings in the United States as well as online meetings and other electronic supports ( https://www.lifering.org/ ). Regarding professional treatment, the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health estimated that about 3.8 million U.S. residents age 12 and older received any type of substance use treatment in the past year, 27 but these numbers are not specific to alcohol treatment. Also missing are data on relative remission rates as a function of type of care-seeking.

Higher problem severity predicts help-seeking, with higher severity reflected in greater alcohol dependence levels and alcohol-related impairment in areas of life functioning such as intimate, family, and social relationships; employment and finances; and legal affairs. 29 Perceived need also predicts help-seeking; however, even among those who perceive a need, only 15% to 30% receive help, 30 and problem recognition often precedes seeking care by a decade. 28 Thus, although most individuals who develop AUD will eventually resolve their problem, treatment utilization remains less used as a pathway to recovery. This pattern has persisted for decades despite recent expansion in the spectrum of services beyond clinical treatment to offer less costly and less intensive services that often can be accessed outside of the health care system and are suitable for those with less severe problems. 28 In addition, provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act expanded access to and coverage of services for SUD.

Recovery Across the Life Span

Studies that followed risk groups and people with drinking problems longitudinally—typically using smaller samples than survey research—provide information on patterns of improvement and recovery across the life span. Some studies assessed functioning and life circumstances, in addition to drinking practices, and revealed the following age-related patterns with respect to the onset of and improvements in alcohol-related problems:

- Drinking to intoxication, binge drinking, and alcohol-related problems increase during adolescence and early adulthood, generally peaking between ages 18 and 22. Prevalence of past-year binge drinking (45%) and AUD (19%) is highest in the early 20s 31 and then decreases beginning in the mid-20s and continuing well after early adulthood. This nonlinear trajectory for the majority of adolescents and young adults, often termed “maturing out,” has been found in cross-sectional and longitudinal research using large national samples 2,32,33 and by the annual cross-sectional National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 1

- Adult role transitions (e.g., employment, marriage, parenthood) and personal maturation (e.g., decreased impulsivity) are associated with remission or recovery in early adulthood. 31,34-36 As is the case for the general adult population with AUD, only about a quarter of adolescents and young adults in need of treatment receive it. 1

- A subset of young adults who engage in harmful alcohol use and develop AUD in early adulthood show persistent or escalating problems in later life. Alcohol use before age 21 predicts persistence and severity of harmful use throughout the life span; 37 however, reductions in problem drinking in early adulthood are more likely to occur among individuals who had the most severe problems at earlier ages. 34

- Development of AUD is less common after age 25, and reductions in problem drinking, including recovery from AUD, continue past early adulthood and across the adult life span, including through late middle and old age (ages 60 to 80 and older). 22,34 Reductions in problem drinking at older ages are predicted by relatively heavier alcohol use in early old age that prompted complaints from concerned others. 22

These trends favoring increased remission rates over the life span are generally representative of the population, but can mask important nuances about age-related associations between problem onset, remission, and recurrence rates. 31,34-36 For example, Vergés and colleagues 35,36 used NESARC data from Waves 1 and 2 (from 2001–2002 to 2004–2005) to “deconstruct” age-related patterns of three different dynamic changes that contributed to overall age-related trends in the prevalence of DSM‑IV alcohol dependence at each wave. Although rates of new alcohol problem onset and recurrence of or relapse to earlier problems declined with age, rates of persistence of alcohol problems over time were relatively stable across ages 18 to 50 and older. These different processes that contributed to the overall trend of decreased alcohol-related problems with increasing age suggest that “maturing out”—as young people assume adult roles—is not a sufficiently complete account of remission rates across the life span.

In related research that also used NESARC data from Waves 1 and 2, Lee and colleagues examined how rates of remission, which they termed “desistance,” from mild, moderate, or severe levels of AUD varied across age groups ranging between ages 20 to 24 and 48 to 55. 34 Using Markov models to characterize patterns of longitudinal transitions in drinking status, they found differences in rates of AUD desistance from young adulthood to middle age as a function of AUD severity levels. Desistance rates from severe AUD, defined as six or more DSM‑IV symptoms, were considerably higher in earlier age groups (ages 25 to 29 and 30 to 34) relative to older age groups (ages 35 to 39, 40 to 47, and 48 to 55) as compared to rates found in surveys that aggregated data across AUD severity levels. Desistance rates from moderate AUD showed a similar, but less dramatic pattern across age groups, whereas desistance rates from mild AUD were relatively stable across age groups. When considered with the work of Vergés and colleagues, 35,36 these studies (1) show that resolution of severe AUD contributes heavily and distinctively to early adulthood remission prevalence, and (2) highlight the importance of deconstructing overall AUD prevalence curves by taking into account onset, remission, and recurrence of different levels of AUD severity over the life span.

Finally, a few studies observed increased binge drinking among middle-aged and older adults, 33 suggesting dynamic changes may occur in binge drinking in midlife; these changes are not well researched. Similarly, most natural recovery research comprises samples showing that midlife recovery from AUD is normative. 9,38 Middle age is also when treatment entry tends to occur. 5 Recovery in midlife and later ages is associated with an accumulation of alcohol-related problems coupled with life contexts that support and reinforce maintenance of drinking reductions and involve post-resolution improvements in functioning and well-being. 38,39

Role of Gender and Race/Ethnicity

In addition to age, rates of recovery or remission of AUD symptoms vary by gender and race/ethnicity. Using NESARC Wave 1 data, Dawson et al. found that older age and female gender predicted abstinence, but not low-risk drinking, in both treated and untreated respondents who had alcohol dependence prior to the past year. 5 Compared to non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks had proportionately higher rates of abstinence than low-risk drinking. In the Fan et al. 7 replication of Dawson et al. 5 using NESARC-III data, female gender predicted both abstinence and low-risk drinking.

Also using NESARC-III data, Vasilenko et al. examined AUD prevalence by age and race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic). 40 Although AUD prevalence generally peaked in the 20s and declined steadily with age, prevalence was higher for Whites at younger ages and higher for Blacks at older ages. This cross-over pattern typically occurred around age 60. In midlife, prevalence was similar for Blacks and Whites. Also, Whites reported higher AUD rates than Hispanic respondents at all ages, and men reported higher AUD rates than women until older age, when women were more likely than men to report AUD in their 70s. However, the number of participants older than age 70 was very small.

The study by Lee et al. that investigated age-related patterns of AUD desistance as a function of AUD severity also found gender and race/ethnicity differences. 34 Desistance patterns for males were generally consistent with the full sample findings—namely, elevated desistance rates for severe AUD in early adulthood and relatively stable rates for mild and moderate AUD. In contrast, females showed markedly higher rates of desistance from moderate AUD in early adulthood compared to older ages and attenuated rates of desistance from severe AUD compared to males during ages 30 to 34 only. With respect to race/ethnicity, results for Whites were generally consistent with the full sample, but findings differed for Hispanics and Blacks. For Hispanics, the early adulthood spike in rates of desistance from severe AUD was more time-limited, occurring only during ages 30 to 34 with much lower rates during ages 25 to 29. For Blacks, desistance rates for mild AUD also were relatively stable but were elevated for both moderate AUD (ages 25 to 29 and 30 to 34) and severe AUD (ages 25 to 29). For severe AUD, desistance rates among Blacks were very low during ages 30 to 34.

Patrick and colleagues analyzed age and gender relations with binge drinking using data from 27 cohorts of the annual Monitoring the Future surveys (1976 to 2004). 41 Participants were followed from 12th grade (modal age 18) through modal age 29/30. Across cohorts, the age of peak binge drinking prevalence increased from age 20 in 1976–1985 to age 22 in 1996–2004 for women, and from age 21 in 1976–1985 to age 23 in 1996–2004 for men. Similar to the typical population life span trajectory for AUD remission, for men the high prevalence of binge drinking persisted through ages 25 to 26, followed by reductions during the late 20s. For women ages 21 to 30, more recent cohorts reported significantly higher binge drinking prevalence than in earlier cohorts, with risk remaining high throughout the 20s. These shifts toward older age of peak binge drinking prevalence indicate an extension of risks associated with harmful alcohol consumption in young adulthood, especially for women.

Taken together, these studies on rates of improvement by gender and race/ethnicity suggest that many of the differences observed involve variations in the timing and extent of reductions in binge drinking and AUD during either young adulthood or older age, even though all groups tended to show overall patterns similar to the population as a whole. Differences during midlife were less extensive, although this developmental period has not been the focus of much research.

Help-Seeking

Help-seeking patterns and preferences also vary by gender and race/ethnicity. The gap between need and receipt of treatment is larger for women than for men, even after controlling for the higher prevalence of AUD and greater problem severity among men. 42,43 For example, using NESARC data from Waves 1 and 2, Gilbert et al. found that women identified as having DSM‑IV alcohol abuse or dependence at Wave 1 had significantly lower odds than men at Wave 2 of having used any alcohol service, specialty treatment, or mutual help groups. 42 These utilization differences occurred even though women and men reported similar low perceived need for help and similar numbers of treatment barriers. Women were more likely to report expecting that their problem would improve without intervention, whereas men were more likely to report prior help-seeking that was unhelpful. No differences in service utilization or perceived need were found for race/ethnicity among White, Black, and Hispanic respondents. Consistent with the larger literature, greater alcohol problem severity was associated with higher odds of service utilization.

Studies using pooled data from multiple waves of the national probability samples collected in the National Alcohol Surveys found differences in service utilization as a function of gender and race/ethnicity. 44,45 Zemore et al. used pooled data from three waves (1995–2005) to investigate lifetime alcohol treatment utilization and perceived barriers among Latinx respondents ( N = 4,204). 44 Among respondents, 3.4%, 2.7%, and 2.1% reported any lifetime treatment, AA participation, and institutional treatment, respectively. Men were significantly more likely than women to report receipt of any treatment services (5.6% vs. 1.1%), AA (4.7% vs. 0.6%), or institutional treatment (3.2% vs. 1.0%). Completion of the study interview in English (4.3%) versus Spanish (2.3%) also predicted higher utilization. These patterns were similar among the subsample of respondents who reported lifetime alcohol dependence, among whom rates of service utilization were much higher (20.4% for men and 15.3% for women). The authors suggested that underutilization of treatment by women and Spanish speakers may be due to cultural stigma against women with an alcohol problem, concerns about racial/ethnic stereotyping or stigmatization when seeking treatment, and additional barriers faced by individuals who are uncomfortable speaking English.

A later study using pooled data from the 2000–2010 National Alcohol Surveys included Whites, Blacks, and Latinx participants and found lower service utilization among Latinx, Blacks (vs. Whites), and women (vs. men). 45 Racial/ethnic differences in utilization were moderated by gender. Among women, only 2.5% of Latinas and 3.4% of Blacks with lifetime AUD used specialty treatment compared to 6.7% of Whites; among men, the corresponding figures were 6.8% for Latinos, 12.2% for Blacks, and 10.1% for Whites. 45 Higher utilization among Whites than among Blacks and Hispanics also was found using the 2014 cohort from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 46

Overall, research on race/ethnicity and help-seeking is not extensive, and groups other than Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics/Latinx have not been well studied. 47 Available research suggests that the gap between need and service utilization common among those with an alcohol problem is accentuated among ethnic and racial minority groups; however, research is in its infancy on why this is the case and how to address it.

Research on the epidemiology of recovery from AUD is somewhat uneven in scope and methods, and gaps remain in the knowledge base. Nonetheless, the bulk of evidence converges in showing that (1) improvements in alcohol-related problems, including recovery from AUD, are commonplace; (2) natural recovery is the dominant pathway; (3) greater problem severity is associated with treatment utilization; and (4) low-risk drinking outcomes are more common among untreated samples. Problem prevalence and rates of remission of AUD symptoms in the U.S. population peak during the 20s and are followed by a slow, steady decline over the adult life span. The specific ages when these characteristic dynamics in the temporal patterning of harmful alcohol use and remission of symptoms occur vary somewhat as a function of gender and race/ethnicity, but the overall general pattern is well established.

These findings provide a rich foundation concerning population patterns and dynamics of recovery, remission, and help-seeking. Future research aimed at disaggregating these complex associations at the population level should be a priority and can inform approaches to promoting remission and recovery in two general ways. 48 First, longitudinal studies of the onset of and improvements in alcohol-related problems 31,34-36 exemplify how epidemiological risk factors are reliably associated with the course of alcohol problem development and improvement and can be used to target at-risk individuals for preventive interventions. Second, “upstream” population-level interventions can be applied to prevent or reduce the determinants of risk (e.g., through changes in policy, taxation, and health and community infrastructure). The latter approach, although less common, takes advantage of the well-established prevention paradox—small reductions in harmful alcohol use by risky drinkers with less serious problems result in far greater health improvements at the population level than do changes in harmful alcohol use by the minority of persons with AUD.

This body of research qualifies the usual characterization of AUD as a chronic, relapsing/remitting disorder for which intensive intervention is essential for recovery. That characterization may be representative for a small minority of persons with more severe AUD, but it is inaccurate for the large majority of persons with mild to moderate problems, many of whom resolve their problems the first time they attempt to quit and often without interventions. 9,49 Whether this qualification applies to SUD other than AUD is not established.

The recovery literature is characterized by a mix of cross-sectional population surveys with short-term retrospective assessments (1 year is typical) and prospective follow-ups of smaller-sized samples of risk groups that, with some notable exceptions, 22-24 also had relatively short follow-ups. Use of data from the multiple waves of the NESARC dominates this research literature. Although the NESARC obtained data from a very large nationally representative sample of the U.S. population age 18 and older (e.g., N = 36,309 in NESARC‑III), it shares limitations inherent to most survey research—namely, assessments must be relatively brief, meaning that the domains of inquiry must be limited and selected carefully and cannot be probed to obtain the detail typically useful in clinical applications.

These design characteristics have contributed to gaps in the literature due to overreliance on drinking practices as the major outcome metric and less common measurement of functioning, well-being, and life circumstances, which are central features of recovery and can occur with or without reductions in drinking. Correlates of remission rates are being reported with increasing frequency in survey research, but tend to be limited to demographic characteristics, problem severity variables related to drinking practices, help-seeking history, and, in some cases, psychiatric comorbidity. Other than the seminal research program of Moos and colleagues, 22,39 assessment of functioning, context, and well-being surrounding drinking behavior change is a relatively recent development, primarily evident in clinical research 18,21 and process-oriented research on natural recovery. 38 Connecting these research literatures in meaningful ways in future investigations is essential for broadening scientific knowledge about how affected individuals reduce and resolve their alcohol-related problems and for guiding improvements in alcohol services that are responsive to heterogeneity in recovery-related outcomes and pathways.

Another issue in need of further research involves deconstruction of separable processes that contribute to overall problem prevalence and remission rates across the life span. As highlighted in the research of Vergés, Lee, Sher, and colleagues, 31,34-36 overall population rates are influenced by age-related associations between problem onset, remission, and recurrence rates, which raises questions about whether remission patterns reflect a simple “maturing out” of harmful alcohol use that began in early adulthood. Based on the available data, Lee and Sher 31 concluded: “[T]he continual declines in AUD rates observed throughout the life span . . . appear mainly attributable to reductions in new onsets . . . whereas potential for desistance from an existing AUD may peak in young adulthood . . . [especially] for those with a severe AUD” (p. 37).

The timing and targeting of prevention and treatment programs could be refined to enhance intervention effectiveness if these age-related associations between problem onset, remission, and recurrence rates were firmly established and used to guide intervention delivery. Conducting this kind of research is challenging because it requires collecting data on all three processes over the life span, and there are additional complexities in studying the tails of the age distribution. For example, clinical diagnostic systems may overdiagnose AUD in adolescence, which would inflate estimates of remission rates in early adulthood. 50 Attrition biases are of concern with advancing age as poor health and death may remove proportionately more older adults with AUD from population samples, thereby inflating estimates of remission rates in old age particularly from severe AUD. 5,34

A final generalization from this research concerns the limited contribution of alcohol treatment or other alcohol-focused services to recovery prevalence in the population. Low rates of service utilization have persisted despite improvements in AUD treatment and lower threshold options 28 and the expansion of access and coverage of services for SUD provided by the Affordable Care Act. The enduring gap between population need and service utilization despite these advances strongly suggests that alternative avenues are needed to increase intervention diffusion and uptake. It has proven insufficient to offer improved treatment predominately through the health care sector, and priority needs to be given to reaching broader segments of the at-risk population of drinkers who contribute most of the alcohol-related harm and cost. Nevertheless, a sizable subset of individuals with AUD improve or recover without interventions, and recent evidence suggests that individuals with more severe AUD exercise some degree of appropriate self-selection into treatment. 29 Empirical questions warranting further investigation are how to distinguish among individuals or risk groups for whom natural recovery is a high probability outcome and how to segment the market so that treatment services are targeted and available for those in need who are not likely to achieve recovery without treatment.

Further improvements in reducing the prevalence of AUD and increasing the prevalence of recovery likely depend on dissolving the silos that have long existed between clinical and epidemiological research and applications 11 and finding novel ways to disseminate evidence-based services to the large underserved at-risk population of drinkers who will not use professional services, at least in their present form. It is also important to consider a broader public health approach to dispel long-held beliefs that alcohol is a problem only for those with severe AUD and that those with AUD can resolve their problem only through abstinence. Perpetuation of these myths over many decades has stigmatized the disorder and deterred help-seeking among the millions of people who would benefit from drinking reductions.

In conclusion, recovery from AUD and alcohol-related problems is the most common outcome among those with problem alcohol use, and recovery without abstinence is possible, even among those with severe AUD. Changing the narrative to highlight the high likelihood of recovery could help engage more individuals in alcohol-related services and may encourage individuals to reduce their drinking in the absence of formal treatment.

Acknowledgments

Portions of the research reported were supported in part by National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant R01 AA022328.

Disclosures

The authors have no competing financial interests to disclose.

Publisher's note

Opinions expressed in contributed articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institutes of Health. The U.S. government does not endorse or favor any specific commercial product or commodity. Any trade or proprietary names appearing in Alcohol Research: Current Reviews are used only because they are considered essential in the context of the studies reported herein. Unless otherwise noted in the text, all material appearing in this journal is in the public domain and may be reproduced without permission. Citation of the source is appreciated.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results From the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health . Rockville, MD: SAMHSA; 2019. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018.pdf . Accessed August 16, 2020.

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry . 2015;72(8):757-766. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584 .

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders . 5th ed. Washington, DC: APA; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 .

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Alcohol Facts and Statistics . Rockville, MD: NIAAA; 2019. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-facts-and-statistics . Accessed January 9, 2020.

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, et al. Recovery from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: United States, 2001-2002. Addiction . 2005;100(3):281-292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00964.x .

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Grant BF. Rates and correlates of relapse among individuals in remission from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: A 3-year follow-up. Alcohol Clin Exp Res . 2007;31(12):2036-2045. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00536.x .

- Fan AZ, Chou SP, Zhang H, et al. Prevalence and correlates of past-year recovery from DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: Results from National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. Alcohol Clin Exp Res . 2019;43(11):2406-2420. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14192 .

- Kelly JF, Bergman B, Hoeppner BB, et al. Prevalence and pathways of recovery from drug and alcohol problems in the United States population: Implications for practice, research, and policy. Drug Alcohol Depend . 2017;181:162-169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.028 .

- Sobell LC, Cunningham JA, Sobell MB. Recovery from alcohol problems with and without treatment: Prevalence in two population studies. Am J Public Health . 1996;86(7):966-972. https://doi.org/2105/ajph.86.7.966 .

- Witkiewitz K, Montes K, Schwebel F, et al. What is recovery? Alcohol Res . 2020;40(3):1. https://doi.org/10.35946/arcr.v40.3.01 .

- Room R. Measurement and distribution of drinking patterns and problems in general populations. In: Edwards G, Gross MS, Keller M, et al., eds. Alcohol-Related Disabilities. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1977:61-87.

- Tucker JA. Natural resolution of alcohol-related problems. In: Galanter M, et al., eds. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Volume 16: Research in Alcoholism Treatment. Boston, MA: Springer; 2002;77-90. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-47939-7_7 .

- World Health Organization (WHO). The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines . Geneva, Switzerland: WHO;1992.

- Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide . Rockville, MD: NIAAA; 2005. https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/practitioner/cliniciansguide2005/guide.pdf . Accessed August 16, 2020.

- Betty Ford Institute Consensus Panel. What is recovery? A working definition from the Betty Ford Institute. J Subst Abuse Treat . 2007;33(3):221-228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2007.06.001 .

- Witkiewitz K, Tucker JA. Abstinence not required: Expanding the definition of recovery from alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res . 2020;44(1)36-40. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14235 .

- Kaskutas LA, Borkman TJ, Laudet A, et al. Elements that define recovery: The experiential perspective. J Stud Alcohol Drugs . 2014;75(6): 999-1010. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2014.75.999 .

- Witkiewitz K, Wilson AD, Pearson MR, et al. Profiles of recovery from alcohol use disorder at three years following treatment: Can the definition of recovery be extended to include high functioning heavy drinkers? Addiction . 2019;114(1):69-80. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14403 .

- Jellinek EM. The Disease Concept of Alcoholism . New Haven, CT: Hillhouse Press; 1960.

- Pearson MR, Kirouac M, Witkiewitz K. Questioning the validity of the 4+/5+ binge or heavy drinking criterion in college and clinical populations. Addiction . 2016;111(10):1720-1726. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13210 .

- Wilson AD, Bravo AJ, Pearson MR, et al. Finding success in failure: Using latent profile analysis to examine heterogeneity in psychosocial functioning among heavy drinkers following treatment. Addiction . 2016;111(12):2145-2154. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13518 .

- Brennan PL, Schutte KK, Moos BS, et al. Twenty-year alcohol-consumption and drinking-problem trajectories of older men and women. J Stud Alcohol Drugs . 2011;72(2):308-321. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2011.72.308 .

- Vaillant GE. The Natural History of Alcoholism Revisited . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1995.

- Mattisson C, Bogren M, Horstmann V, et al. Remission from alcohol use disorder among males in the Lundby Cohort during 1947–1997. Psychiatry J . 2018;4829389. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4829389 .

- Sarich P, Canfell K, Banks E, et al. A prospective study of health conditions related to alcohol consumption cessation among 97,852 drinkers aged 45 and over in Australia. Alcohol Clin Exp Res . 2019;43(4):710‑721. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13981 .

- Grella CE, Stein JA. Remission from substance dependence: Differences between individuals in a general population longitudinal survey who do and do not seek help. Drug Alcohol Depend . 2013;133(1):146-153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.019 .

- SAMHSA. National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS): 2016. Data on Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities . Rockville, MD: SAMHSA; 2017. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/2016_NSSATS.pdf

- Tucker JA, Simpson CA. The recovery spectrum: From self-change to seeking treatment. Alcohol Res Health . 2011;33(4):371-379.

- Tuithof M, ten Have M, van den Brink W, et al. Treatment seeking for alcohol use disorders: Treatment gap or adequate self-selection? Eur Addict Res . 2016;22(5):277-285. https://doi.org/10.1159/000446822 .

- Schuler MS, Puttaiah S, Mojtabai R, et al. Perceived barriers to treatment for alcohol problems: A latent class analysis. Psychiatr Serv . 2015;66(11):1221-1228. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400160 .

- Lee MR, Sher KJ. “Maturing out” of binge and problem drinking. Alcohol Res . 2018;39(1):31-42.

- Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001–2002 to 2012–2013: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry . 2017;74(9):911-923. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161 .

- Grucza RA, Sher KJ, Kerr WC, et al. Trends in adult alcohol use and binge drinking in the early 21st-century United States: A meta-analysis of 6 national survey series. Alcohol Clin Exp Res . 2018;42(10):1939-1950. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13859 .

- Lee MR, Boness CL, McDowell YE, et al. Desistance and severity of alcohol use disorder: A lifespan-developmental investigation. Clin Psychol Sci . 2018;6(1):90-105. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702617736852 .

- Vergés A, Jackson KM, Bucholz KK, et al. Deconstructing the age-prevalence curve of alcohol dependence: Why "maturing out" is only a small piece of the puzzle. J Abnorm Psychol . 2012;121(2):511-523. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026027 .

- Vergés A, Haeny AM, Jackson KM, et al. Refining the notion of maturing out: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Am J Public Health . 2013;103(12):e67-e73. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2013.301358 .

- Hingson RW, Hereen T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: Age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med . 2006;160(7):739-746. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739 .

- Tucker JA, Cheong J, James TG, et al. Preresolution drinking problem severity profiles associated with stable moderation outcomes of natural recovery attempts. Alcohol Clin Exp Res . 2020;44(3):738-745. https://doi.org/1111/acer.14287 .

- Moos RH, Finney JW, Cronkite RC. Alcoholism Treatment: Context, Process, and Outcome . New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1990.

- Vasilenko SA, Evans-Polce RJ, Lanza ST. Age trends in rates of substance use disorders across ages 18-90: Differences by gender and race/ethnicity. Drug Alcohol Depend . 2017;180:260-264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.08.027 .

- Patrick ME, Terry-McElrath YM, Lanza ST, et al. Shifting age of peak binge drinking prevalence: Historical changes in normative trajectories among young adults aged 18 to 30. Alcohol Clin Exp Res . 2019;43(2):287-298. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13933 .

- Gilbert PA, Pro G, Zemore SE, et al. Gender differences in use of alcohol treatment services and reasons for nonuse in a national sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res . 2019;43(4):722-31. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13965 .

- Greenfield SF, Black SE, Lawson K, et al. Substance abuse in women. Psychiatr Clin North Am . 2010;33(2):339-355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2010.01.004 .

- Zemore SE, Mulia N, Ye Y, et al. Gender, acculturation, and other barriers to alcohol treatment utilization among Latinos in three National Alcohol Surveys. J Subst Abuse Treat . 2009;36(4):446-456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2008.09.005 .

- Zemore SE, Murphy RD, Mulia N, et al. A moderating role for gender in racial/ethnic disparities in alcohol services utilization: Results from the 2000 to 2010 National Alcohol Surveys. Alcohol Clin Exp Res . 2014;38(8):2286-2296. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12500 .

- SAMHSA. Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results From the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health . Rockville, MD: SAMHSA; 2015. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/results-from-the-2014-national-survey-on-drug-and-use-and-health-summary-of-national-findings/sma15-4927 . Accessed August 16, 2020.

- Vaeth PAC, Wang-Schweig M, Caetano R. Drinking, alcohol use disorder, and treatment access and utilization among U.S. racial/ethnic groups. Alcohol Clin Exp Res . 2017;41(1):6-19. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13285 .

- Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol . 2001;30(3):427-434. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/30.3.427 .

- Kelly JF, Greene MC, Bergman BG, et al. How many recovery attempts does it take to successfully resolve an alcohol or drug problem? Estimates and correlates from a national study of recovering U.S. adults. Alcohol Clin Exp Res . 2019;43(7):1533-1544. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14067 .

- Caetano R, Babor TF. Diagnosis of alcohol dependence in epidemiological surveys: An epidemic of youthful alcohol dependence or a case of measurement error? Addiction . 2006;101(s1):111-114. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01599.x .

Cite this as: Alcohol Research. 2020;40(3):02. https://doi.org/10.35946/arcr.v40.3.02

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Endometriosis

- Excessive heat

- Mental disorders

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Observatory

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Fact sheets /

- Alcohol or alcoholic beverages contain ethanol, a psychoactive and toxic substance that can cause dependence.

- Worldwide, around 2.6 million deaths were caused by alcohol consumption in 2019. Of these, 1.6 million deaths were from noncommunicable diseases, 700 000 deaths from injuries and 300 000 deaths from communicable diseases.

- The alcohol-attributable mortality was heaviest among men, accounting for 2 million deaths compared to 600 000 deaths among women, in 2019.

- An estimated 400 million people, or 7% of the world’s population aged 15 years and older, lived with alcohol use disorders. Of this, 209 million people (3.7% of the adult world population) lived with alcohol dependence.

- Alcohol consumption, even at low levels can bring health risks, but most alcohol related harms come from heavy episodic or heavy continuous alcohol consumption.

- Effective alcohol control interventions exist and should be utilized more, at the same time it is important for people to know risks associated with alcohol consumption and take individual actions to protect from its harmful effects.

Alcohol and alcoholic beverages contain ethanol, which is a psychoactive and toxic substance with dependence-producing properties. Alcohol has been widely used in many cultures for centuries, but it is associated with significant health risks and harms.

Worldwide, 2.6 million deaths were attributable to alcohol consumption in 2019, of which 2 million were among men and 0.6 million among women. The highest levels of alcohol-related deaths per 100 000 persons are observed in the WHO European and African Regions with 52.9 deaths and 52.2 deaths per 100 000 people, respectively.

People of younger age (20–39 years) are disproportionately affected by alcohol consumption with the highest proportion (13%) of alcohol-attributable deaths occurring within this age group in 2019.

The data on global alcohol consumption in 2019 shows that an estimated 400 million people aged 15 years and older live with alcohol use disorders, and an estimated 209 million live with alcohol dependence.

There has been some progress; from 2010 to 2019, the number of alcohol-attributable deaths per 100 000 people decreased by 20.2% globally.

There has been a steady increase in the number of countries developing national alcohol policies. Almost all countries implement alcohol excise taxes. However, countries report continued interference from the alcohol industry in policy development.

Based on 2019 data, about 54% out of 145 reporting countries had national guidelines/standards for specialized treatment services for alcohol use disorders, but only 46% of countries had legal regulations to protect the confidentiality of people in treatment.

Access to screening, brief intervention and treatment for people with hazardous alcohol use and alcohol use disorder remains very low, as well as access to medications for treatment of alcohol use disorders. Overall, the proportion of people with alcohol use disorders in contact with treatment services varies from less than 1% to no more than 14% in all countries where such data are available.

Health risks of alcohol use

Alcohol consumption is found to play a causal role in more than 200 diseases, injuries and other health conditions. However, the global burden of disease and injuries caused by alcohol consumption can be quantified for only 31 health conditions on the basis of the available scientific evidence for the role of alcohol use in their development, occurrence and outcomes.

Drinking alcohol is associated with risks of developing noncommunicable diseases such as liver diseases, heart diseases, and different types of cancers, as well as mental health and behavioural conditions such as depression, anxiety and alcohol use disorders.

An estimated 474 000 deaths from cardiovascular diseases were caused by alcohol consumption in 2019.

Alcohol is an established carcinogen and alcohol consumption increases the risk of several cancers, including breast, liver, head and neck, oesophageal and colorectal cancers. In 2019, 4.4% of cancers diagnosed globally and 401 000 cancer deaths were attributed to alcohol consumption.

Alcohol consumption also causes significant harm to others, not just to the person consuming alcohol. A significant part of alcohol-attributable disease burden arises from injuries such as road traffic accidents. In 2019, of a total of 298 000 deaths from alcohol-related road crashes, 156 000 deaths were caused by someone else’s drinking.

Other injuries, intentional or unintentional, include falls, drowning, burns, sexual assault, intimate partner violence and suicide.

A causal relationship has been established between alcohol use and the incidence or outcomes of infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and HIV.

Alcohol consumption during pregnancy increases the risk of having a child with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs), the most severe form of which is fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), which is associated with developmental disabilities and birth defects. Alcohol consumption during pregnancy can also increase the risk of pre-term birth complications including miscarriage, stillbirth and premature delivery.

Younger people are disproportionately negatively affected by alcohol consumption, with the highest proportion (13%) of alcohol-attributable deaths in 2019 occurring among people aged between 20 and 39 years.

In the long term, harmful and hazardous levels of alcohol consumption can lead to social problems including family problems, issues at work, financial problems, and unemployment.

Factors affecting alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harm

There is no form of alcohol consumption that is risk-free. Even low levels of alcohol consumption carry some risks and can cause harm.

The level of risk depends on several factors, including the amount consumed, frequency of drinking, the health status of the individual, age, sex, and other personal characteristics, as well as the context in which alcohol consumption occurs.

Some groups and individuals who are vulnerable or at risk may have a higher susceptibility to the toxic, psychoactive and dependence-inducing properties of alcohol. On the other hand, individuals who adopt lower-risk patterns of alcohol consumption may not necessarily face a significantly increased likelihood of negative health and social consequences.

Societal factors which affect the levels and patterns of alcohol consumption and related problems include cultural and social norms, availability of alcohol, level of economic development, and implementation and enforcement of alcohol policies.

The impact of alcohol consumption on chronic and acute health outcomes is largely determined by the total volume of alcohol consumed and the pattern of drinking, particularly those patterns which are associated with the frequency of drinking and episodes of heavy drinking. Most alcohol related harms come from heavy episodic or heavy continuous alcohol consumption.

The context plays an important role in the occurrence of alcohol-related harm, particularly as a result of alcohol intoxication. Alcohol consumption can have an impact not only on the incidence of diseases, injuries and other health conditions, but also on their outcomes and how these evolve over time.

There are gender differences in both alcohol consumption and alcohol-related mortality and morbidity. In 2019, 52% of men were current drinkers, while only 35% of women had been drinking alcohol in the last 12 months. Alcohol per capita consumption was, on average, 8.2 litres for men compared to 2.2 litres for women. In 2019, alcohol use was responsible for 6.7% of all deaths among men and 2.4% of all deaths among women.

WHO response

The Global alcohol action plan 2022–2030, endorsed by WHO Member States, aims to reduce the harmful use of alcohol through effective, evidence-based strategies at national, regional and global levels. The plan outlines six key areas for action: high-impact strategies and interventions, advocacy and awareness, partnership and coordination, technical support and capacity-building, knowledge production and information systems, and resource mobilization.

Implementation of global strategy and action plan will accelerate global progress towards attaining alcohol-related targets under the Sustainable Development Goal 3.5 on strengthening the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse and harmful use of alcohol.

Achieving this will require global, regional and national actions on the levels, patterns and contexts of alcohol consumption and the wider social determinants of health, with a particular focus on implementing high-impact cost effective interventions.

It is vital to address the determinants that drive the acceptability, availability and affordability of alcohol consumption through cross-sectoral, comprehensive and integrated policy measures. It is also of critical importance to achieve universal health coverage for people living with alcohol use disorders and other health conditions due to alcohol use by strengthening health system responses and developing comprehensive and accessible systems of treatment and care that for those in need.

The SAFER initiative, launched in 2018 by WHO and partners, supports countries to implement the high-impact, cost-effective interventions proven to reduce the harm caused by alcohol consumption.

The WHO Global Information System on Alcohol and Health (GISAH) presents data on levels and patterns of alcohol consumption, alcohol-attributable health and social consequences and policy responses across the world.

Achieving a reduction in the harmful use of alcohol in line with the targets included in the Global alcohol action plan, the SDG 2030 agenda and the WHO Global monitoring framework for noncommunicable diseases, requires concerted action by countries and effective global governance.

Public policies and interventions to prevent and reduce alcohol-related harm should be guided and formulated by public health interests and based on clear public health goals and the best available evidence.

Engaging all relevant stakeholders is essential but the potential conflicts of interest, particularly with the alcohol industry, must be carefully assessed before engagement. Economic operators should refrain from activities that might prevent, delay or stop the development, enactment, implementation and enforcement of high-impact strategies and interventions to reduce the harmful use of alcohol.

By working together, with due diligence and protection from conflicts of interest, the negative health and social consequences of alcohol can be effectively reduced.

Global status report on alcohol and health and treatment of substance use disorders

Global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol

Global Alcohol Action Plan 2022–2030

SAFER Alcohol Control Initiative

More on alcohol

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Trend of alcohol use disorder as a percentage of all-cause mortality in North America

Affiliations.

- 1 Institute for Mental Health Policy Research, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), 33 Ursula Franklin Street, Toronto, ON, M5S 2S1, Canada. [email protected].

- 2 Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute, CAMH, 250 College Street, Toronto, ON, M5T 1R8, Canada. [email protected].

- 3 Institute for Mental Health Policy Research, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), 33 Ursula Franklin Street, Toronto, ON, M5S 2S1, Canada.

- 4 Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute, CAMH, 250 College Street, Toronto, ON, M5T 1R8, Canada.

- 5 Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, 155 College Street, 6th Floor, Toronto, ON, M5T 3M7, Canada.

- 6 Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, 250 College Street, 8th Floor, Toronto, ON, M5T 1R8, Canada.

- 7 Institute of Medical Science (IMS), University of Toronto, Medical Sciences Building, 1 King's College Circle, Room 2374, Toronto, ON, M5S 1A8, Canada.

- 8 Center for Interdisciplinary Addiction Research (ZIS), Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), Martinistraße 52, 20246, Hamburg, Germany.

- 9 Program on Substance Abuse & WHO CC, Public Health Agency of Catalonia, 81-95 Roc Boronat St, Barcelona, 08005, Spain.

- PMID: 39210466

- PMCID: PMC11360856

- DOI: 10.1186/s13104-024-06882-w

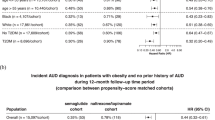

Objective: To evaluate the trend of alcohol use disorder (AUD) mortality as a percentage of all-cause mortality in Canada and the United States (US) between 2000 and 2019, by age group.

Results: Joinpoint regression showed that AUD mortality as a percentage of all-cause mortality significantly increased between 2000 and 2019 in both countries, and across all age groups (i.e., young adults (20-34 years), middle-aged adults (35-49 years), and older adults (50 + years)). The trend has been levelling off, and even reversing in some cases, in recent years. The average annual percentage change differed across countries and between age groups, with a greater increase among Canadian adults aged 35-49 years and among adults aged 50 + years in the US. Over the past two decades, AUD mortality as a percentage of all-cause mortality has been increasing among all adults in both Canada and the US.

Keywords: AUD; Alcohol-attributable harm; Disease trends; Joinpoint regression.

© 2024. The Author(s).

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Joinpoint regression analysis of percentage…

Joinpoint regression analysis of percentage AUD of all-causes of mortality, raw data (black…

- Spillane S, Shiels MS, Best AF, Haozous EA, Withrow DR, Chen Y, et al. Trends in alcohol-induced deaths in the United States, 2000–2016. JAMA Netw open. 2020;3(2):e1921451–e. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21451 - DOI - PMC - PubMed

- Lee E, Navadurong H, Liangpunsakul S. Epidemiology and trends of alcohol use disorder and alcohol-associated liver disease. Clin Liver Disease. 2023;22(3):99–102. - PMC - PubMed

- Doycheva I, Watt KD, Rifai G, Abou Mrad R, Lopez R, Zein NN, et al. Increasing burden of chronic liver disease among adolescents and young adults in the USA: a silent epidemic. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:1373–80. 10.1007/s10620-017-4492-3 - DOI - PubMed

- Flemming JA, Dewit Y, Mah JM, Saperia J, Groome PA, Booth CM. Incidence of cirrhosis in young birth cohorts in Canada from 1997 to 2016: a retrospective population-based study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4(3):217–26. 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30339-X - DOI - PubMed

- Rehm J, Dawson D, Frick U, Gmel G, Roerecke M, Shield KD et al. Burden of disease associated with alcohol use disorders in the United States. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38(4):1068-77. - PMC - PubMed

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- BioMed Central

- PubMed Central

- MedlinePlus Health Information

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Alcohol Use and Your Health

- Preventing Alcohol-Related Harms

- Underage Drinking

- Data on Excessive Alcohol Use

- U.S. Deaths from Excessive Alcohol Use

- Publications

- About Surveys on Alcohol Use

- About Standard Drink Sizes

- CDC Alcohol Program

- Alcohol Outlet Density Measurement Tools

- Resources to Prevent Excessive Alcohol Use

- Online Alcohol Tools and Apps

- Funding to Prevent Excessive Alcohol Use

Related Topics:

- View All Home

- Alcohol-Related Disease Impact (ARDI) Application

- Check Your Drinking. Make a Plan to Drink Less.

- Controle su forma de beber. Haga un plan para beber menos.

- Addressing Excessive Alcohol Use: State Fact Sheets

- Excessive alcohol use can have immediate and long-term effects.

- Excessive drinking includes binge drinking, heavy drinking, and any drinking during pregnancy or by people younger than 21.

- Drinking less is better for your health than drinking more.

- You can lower your health risks by drinking less or choosing not to drink.

Why it's important

- The rest of the alcohol can harm your liver and other organs as it moves through the body.