What (Exactly) Is Thematic Analysis?

Plain-Language Explanation & Definition (With Examples)

By: Jenna Crosley (PhD). Expert Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | April 2021

Thematic analysis is one of the most popular qualitative analysis techniques we see students opting for at Grad Coach – and for good reason. Despite its relative simplicity, thematic analysis can be a very powerful analysis technique when used correctly. In this post, we’ll unpack thematic analysis using plain language (and loads of examples) so that you can conquer your analysis with confidence.

Thematic Analysis 101

- Basic terminology relating to thematic analysis

- What is thematic analysis

- When to use thematic analysis

- The main approaches to thematic analysis

- The three types of thematic analysis

- How to “do” thematic analysis (the process)

- Tips and suggestions

First, the lingo…

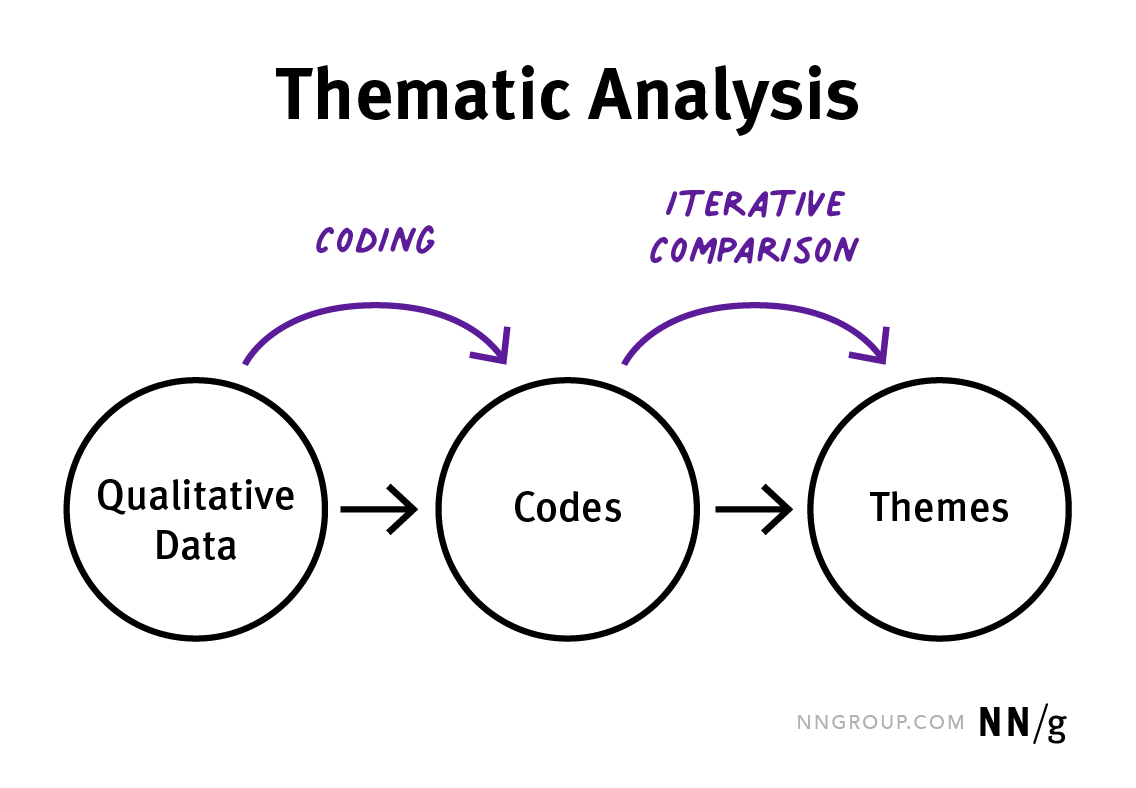

Before we begin, let’s first lay down some terminology. When undertaking thematic analysis, you’ll make use of codes . A code is a label assigned to a piece of text, and the aim of using a code is to identify and summarise important concepts within a set of data, such as an interview transcript.

For example, if you had the sentence, “My rabbit ate my shoes”, you could use the codes “rabbit” or “shoes” to highlight these two concepts. The process of assigning codes is called coding. If this is a new concept to you, be sure to check out our detailed post about qualitative coding .

Codes are vital as they lay a foundation for themes . But what exactly is a theme? Simply put, a theme is a pattern that can be identified within a data set. In other words, it’s a topic or concept that pops up repeatedly throughout your data. Grouping your codes into themes serves as a way of summarising sections of your data in a useful way that helps you answer your research question(s) and achieve your research aim(s).

Alright – with that out of the way, let’s jump into the wonderful world of thematic analysis…

What is thematic analysis?

Thematic analysis is the study of patterns to uncover meaning . In other words, it’s about analysing the patterns and themes within your data set to identify the underlying meaning. Importantly, this process is driven by your research aims and questions , so it’s not necessary to identify every possible theme in the data, but rather to focus on the key aspects that relate to your research questions .

Although the research questions are a driving force in thematic analysis (and pretty much all analysis methods), it’s important to remember that these questions are not necessarily fixed . As thematic analysis tends to be a bit of an exploratory process, research questions can evolve as you progress with your coding and theme identification.

When should you use thematic analysis?

There are many potential qualitative analysis methods that you can use to analyse a dataset. For example, content analysis , discourse analysis , and narrative analysis are popular choices. So why use thematic analysis?

Thematic analysis is highly beneficial when working with large bodies of data , as it allows you to divide and categorise large amounts of data in a way that makes it easier to digest. Thematic analysis is particularly useful when looking for subjective information , such as a participant’s experiences, views, and opinions. For this reason, thematic analysis is often conducted on data derived from interviews , conversations, open-ended survey responses , and social media posts.

Your research questions can also give you an idea of whether you should use thematic analysis or not. For example, if your research questions were to be along the lines of:

- How do dog walkers perceive rules and regulations on dog-friendly beaches?

- What are students’ experiences with the shift to online learning?

- What opinions do health professionals hold about the Hippocratic code?

- How is gender constructed in a high school classroom setting?

These examples are all research questions centering on the subjective experiences of participants and aim to assess experiences, views, and opinions. Therefore, thematic analysis presents a possible approach.

In short, thematic analysis is a good choice when you are wanting to categorise large bodies of data (although the data doesn’t necessarily have to be large), particularly when you are interested in subjective experiences .

What are the main approaches?

Broadly speaking, there are two overarching approaches to thematic analysis: inductive and deductive . The approach you take will depend on what is most suitable in light of your research aims and questions. Let’s have a look at the options.

The inductive approach

The inductive approach involves deriving meaning and creating themes from data without any preconceptions . In other words, you’d dive into your analysis without any idea of what codes and themes will emerge, and thus allow these to emerge from the data.

For example, if you’re investigating typical lunchtime conversational topics in a university faculty, you’d enter the research without any preconceived codes, themes or expected outcomes. Of course, you may have thoughts about what might be discussed (e.g., academic matters because it’s an academic setting), but the objective is to not let these preconceptions inform your analysis.

The inductive approach is best suited to research aims and questions that are exploratory in nature , and cases where there is little existing research on the topic of interest.

The deductive approach

In contrast to the inductive approach, a deductive approach involves jumping into your analysis with a pre-determined set of codes . Usually, this approach is informed by prior knowledge and/or existing theory or empirical research (which you’d cover in your literature review ).

For example, a researcher examining the impact of a specific psychological intervention on mental health outcomes may draw on an existing theoretical framework that includes concepts such as coping strategies, social support, and self-efficacy, using these as a basis for a set of pre-determined codes.

The deductive approach is best suited to research aims and questions that are confirmatory in nature , and cases where there is a lot of existing research on the topic of interest.

Regardless of whether you take the inductive or deductive approach, you’ll also need to decide what level of content your analysis will focus on – specifically, the semantic level or the latent level.

A semantic-level focus ignores the underlying meaning of data , and identifies themes based only on what is explicitly or overtly stated or written – in other words, things are taken at face value.

In contrast, a latent-level focus concentrates on the underlying meanings and looks at the reasons for semantic content. Furthermore, in contrast to the semantic approach, a latent approach involves an element of interpretation , where data is not just taken at face value, but meanings are also theorised.

“But how do I know when to use what approach?”, I hear you ask.

Well, this all depends on the type of data you’re analysing and what you’re trying to achieve with your analysis. For example, if you’re aiming to analyse explicit opinions expressed in interviews and you know what you’re looking for ahead of time (based on a collection of prior studies), you may choose to take a deductive approach with a semantic-level focus.

On the other hand, if you’re looking to explore the underlying meaning expressed by participants in a focus group, and you don’t have any preconceptions about what to expect, you’ll likely opt for an inductive approach with a latent-level focus.

Simply put, the nature and focus of your research, especially your research aims , objectives and questions will inform the approach you take to thematic analysis.

What are the types of thematic analysis?

Now that you’ve got an understanding of the overarching approaches to thematic analysis, it’s time to have a look at the different types of thematic analysis you can conduct. Broadly speaking, there are three “types” of thematic analysis:

- Reflexive thematic analysis

- Codebook thematic analysis

- Coding reliability thematic analysis

Let’s have a look at each of these:

Reflexive thematic analysis takes an inductive approach, letting the codes and themes emerge from that data. This type of thematic analysis is very flexible, as it allows researchers to change, remove, and add codes as they work through the data. As the name suggests, reflexive thematic analysis emphasizes the active engagement of the researcher in critically reflecting on their assumptions, biases, and interpretations, and how these may shape the analysis.

Reflexive thematic analysis typically involves iterative and reflexive cycles of coding, interpreting, and reflecting on data, with the aim of producing nuanced and contextually sensitive insights into the research topic, while at the same time recognising and addressing the subjective nature of the research process.

Codebook thematic analysis , on the other hand, lays on the opposite end of the spectrum. Taking a deductive approach, this type of thematic analysis makes use of structured codebooks containing clearly defined, predetermined codes. These codes are typically drawn from a combination of existing theoretical theories, empirical studies and prior knowledge of the situation.

Codebook thematic analysis aims to produce reliable and consistent findings. Therefore, it’s often used in studies where a clear and predefined coding framework is desired to ensure rigour and consistency in data analysis.

Coding reliability thematic analysis necessitates the work of multiple coders, and the design is specifically intended for research teams. With this type of analysis, codebooks are typically fixed and are rarely altered.

The benefit of this form of analysis is that it brings an element of intercoder reliability where coders need to agree upon the codes used, which means that the outcome is more rigorous as the element of subjectivity is reduced. In other words, multiple coders discuss which codes should be used and which shouldn’t, and this consensus reduces the bias of having one individual coder decide upon themes.

Quick Recap: Thematic analysis approaches and types

To recap, the two main approaches to thematic analysis are inductive , and deductive . Then we have the three types of thematic analysis: reflexive, codebook and coding reliability . Which type of thematic analysis you opt for will need to be informed by factors such as:

- The approach you are taking. For example, if you opt for an inductive approach, you’ll likely utilise reflexive thematic analysis.

- Whether you’re working alone or in a group . It’s likely that, if you’re doing research as part of your postgraduate studies, you’ll be working alone. This means that you’ll need to choose between reflexive and codebook thematic analysis.

Now that we’ve covered the “what” in terms of thematic analysis approaches and types, it’s time to look at the “how” of thematic analysis.

Need a helping hand?

How to “do” thematic analysis

At this point, you’re ready to get going with your analysis, so let’s dive right into the thematic analysis process. Keep in mind that what we’ll cover here is a generic process, and the relevant steps will vary depending on the approach and type of thematic analysis you opt for.

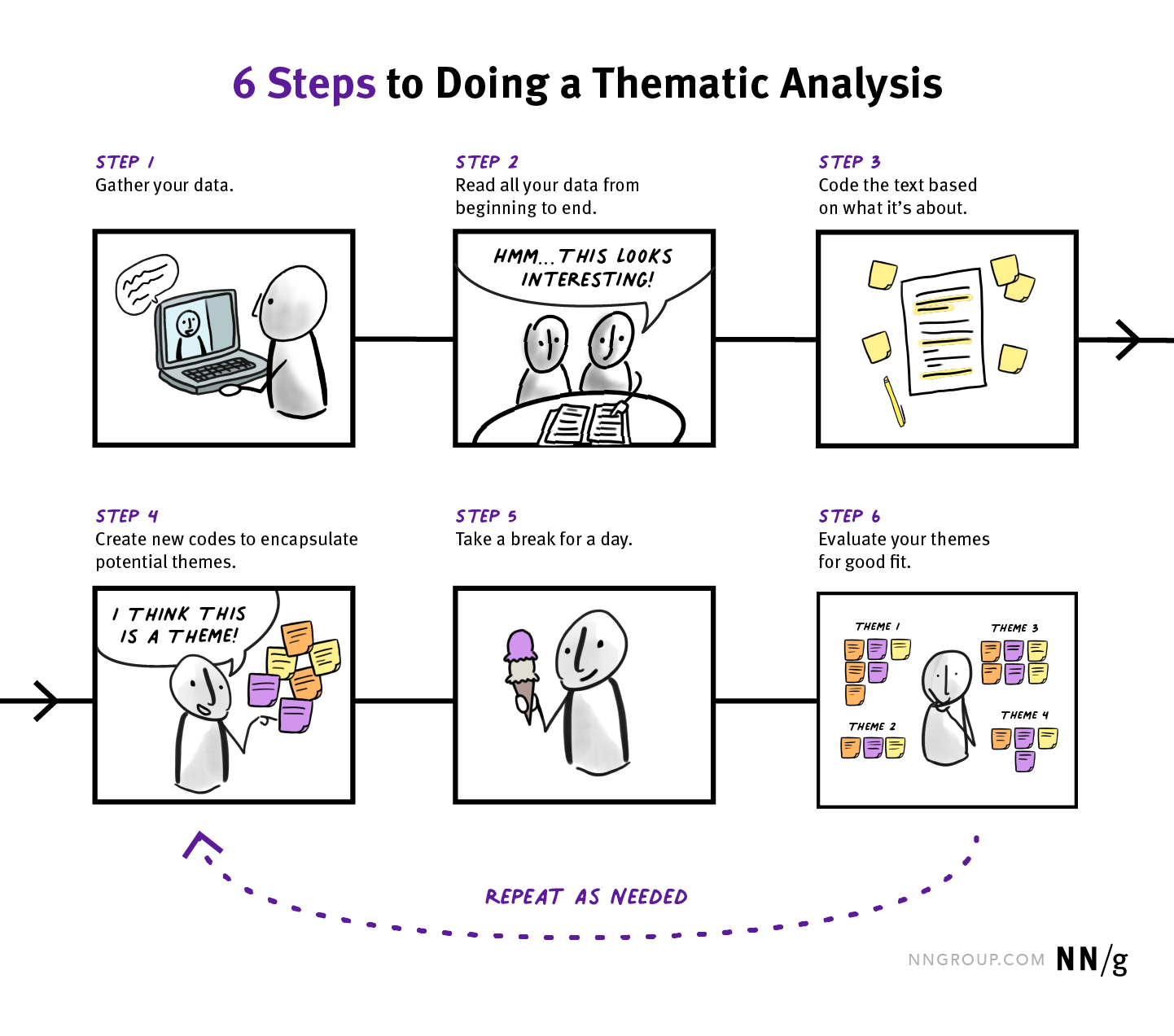

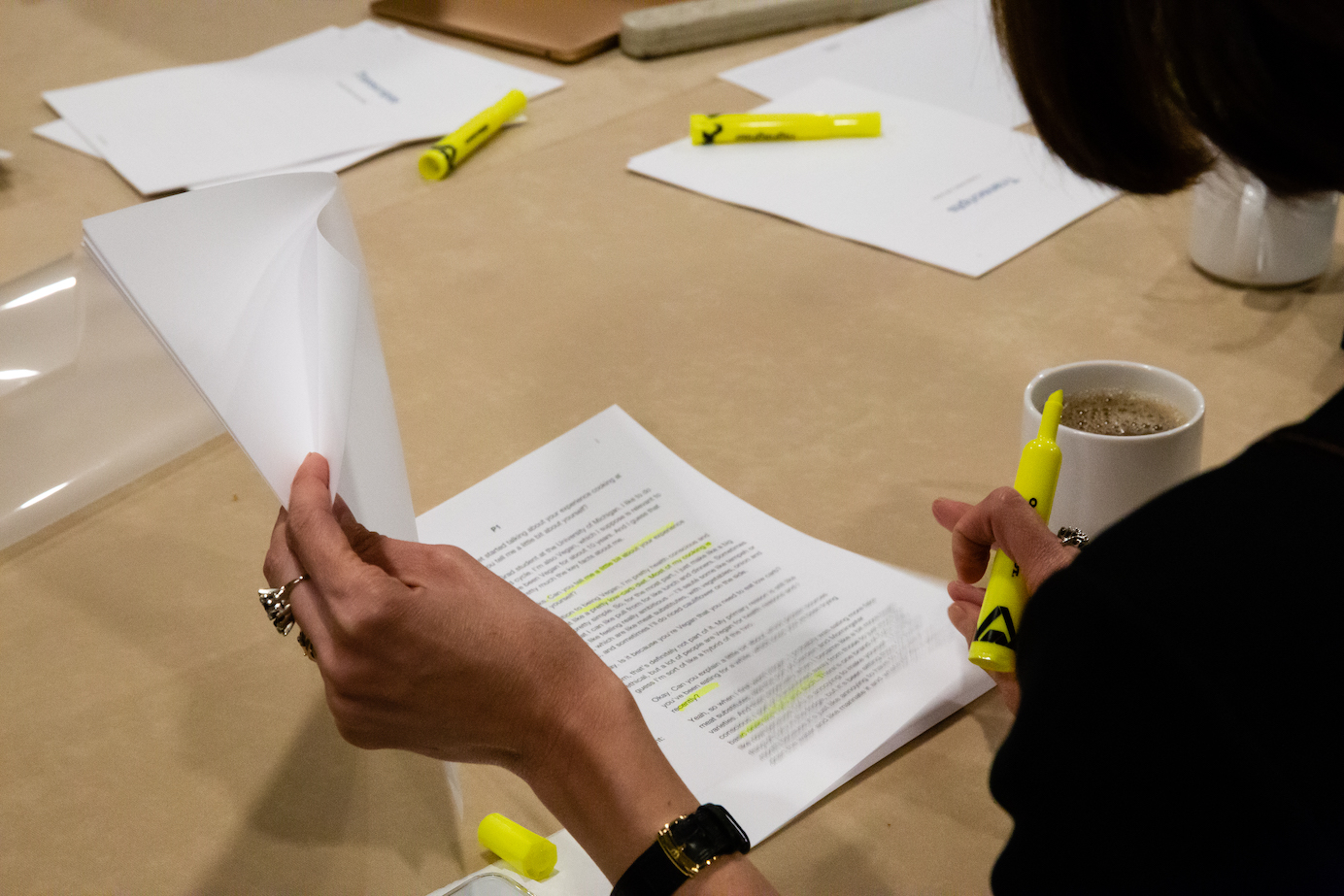

Step 1: Get familiar with the data

The first step in your thematic analysis involves getting a feel for your data and seeing what general themes pop up. If you’re working with audio data, this is where you’ll do the transcription , converting audio to text.

At this stage, you’ll want to come up with preliminary thoughts about what you’ll code , what codes you’ll use for them, and what codes will accurately describe your content. It’s a good idea to revisit your research topic , and your aims and objectives at this stage. For example, if you’re looking at what people feel about different types of dogs, you can code according to when different breeds are mentioned (e.g., border collie, Labrador, corgi) and when certain feelings/emotions are brought up.

As a general tip, it’s a good idea to keep a reflexivity journal . This is where you’ll write down how you coded your data, why you coded your data in that particular way, and what the outcomes of this data coding are. Using a reflexive journal from the start will benefit you greatly in the final stages of your analysis because you can reflect on the coding process and assess whether you have coded in a manner that is reliable and whether your codes and themes support your findings.

As you can imagine, a reflexivity journal helps to increase reliability as it allows you to analyse your data systematically and consistently. If you choose to make use of a reflexivity journal, this is the stage where you’ll want to take notes about your initial codes and list them in your journal so that you’ll have an idea of what exactly is being reflected in your data. At a later stage in the analysis, this data can be more thoroughly coded, or the identified codes can be divided into more specific ones.

Step 2: Search for patterns or themes in the codes

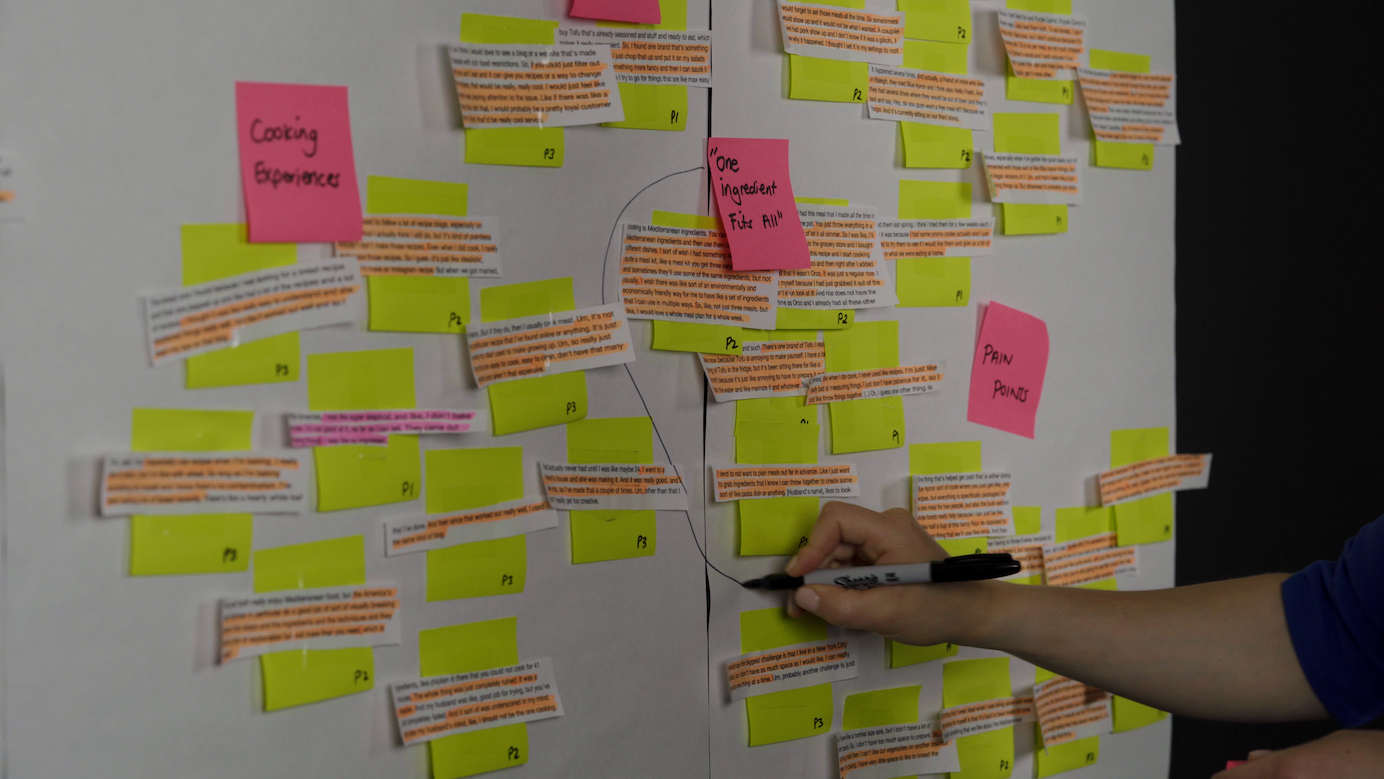

Step 2! You’re going strong. In this step, you’ll want to look out for patterns or themes in your codes. Moving from codes to themes is not necessarily a smooth or linear process. As you become more and more familiar with the data, you may find that you need to assign different codes or themes according to new elements you find. For example, if you were analysing a text talking about wildlife, you may come across the codes, “pigeon”, “canary” and “budgerigar” which can fall under the theme of birds.

As you work through the data, you may start to identify subthemes , which are subdivisions of themes that focus specifically on an aspect within the theme that is significant or relevant to your research question. For example, if your theme is a university, your subthemes could be faculties or departments at that university.

In this stage of the analysis, your reflexivity journal entries need to reflect how codes were interpreted and combined to form themes.

Step 3: Review themes

By now you’ll have a good idea of your codes, themes, and potentially subthemes. Now it’s time to review all the themes you’ve identified . In this step, you’ll want to check that everything you’ve categorised as a theme actually fits the data, whether the themes do indeed exist in the data, whether there are any themes missing , and whether you can move on to the next step knowing that you’ve coded all your themes accurately and comprehensively . If you find that your themes have become too broad and there is far too much information under one theme, it may be useful to split this into more themes so that you’re able to be more specific with your analysis.

In your reflexivity journal, you’ll want to write about how you understood the themes and how they are supported by evidence, as well as how the themes fit in with your codes. At this point, you’ll also want to revisit your research questions and make sure that the data and themes you’ve identified are directly relevant to these questions .

Step 4: Finalise Themes

By this point, your analysis will really start to take shape. In the previous step, you reviewed and refined your themes, and now it’s time to label and finalise them . It’s important to note here that, just because you’ve moved onto the next step, it doesn’t mean that you can’t go back and revise or rework your themes. In contrast to the previous step, finalising your themes means spelling out what exactly the themes consist of, and describe them in detail . If you struggle with this, you may want to return to your data to make sure that your data and coding do represent the themes, and if you need to divide your themes into more themes (i.e., return to step 3).

When you name your themes, make sure that you select labels that accurately encapsulate the properties of the theme . For example, a theme name such as “enthusiasm in professionals” leaves the question of “who are the professionals?”, so you’d want to be more specific and label the theme as something along the lines of “enthusiasm in healthcare professionals”.

It is very important at this stage that you make sure that your themes align with your research aims and questions . When you’re finalising your themes, you’re also nearing the end of your analysis and need to keep in mind that your final report (discussed in the next step) will need to fit in with the aims and objectives of your research.

In your reflexivity journal, you’ll want to write down a few sentences describing your themes and how you decided on these. Here, you’ll also want to mention how the theme will contribute to the outcomes of your research, and also what it means in relation to your research questions and focus of your research.

By the end of this stage, you’ll be done with your themes – meaning it’s time to write up your findings and produce a report.

Step 5: Produce your report

You’re nearly done! Now that you’ve analysed your data, it’s time to report on your findings. A typical thematic analysis report consists of:

- An introduction

- A methodology section

- Your results and findings

- A conclusion

When writing your report, make sure that you provide enough information for a reader to be able to evaluate the rigour of your analysis. In other words, the reader needs to know the exact process you followed when analysing your data and why. The questions of “what”, “how”, “why”, “who”, and “when” may be useful in this section.

So, what did you investigate? How did you investigate it? Why did you choose this particular method? Who does your research focus on, and who are your participants? When did you conduct your research, when did you collect your data, and when was the data produced? Your reflexivity journal will come in handy here as within it you’ve already labelled, described, and supported your themes.

If you’re undertaking a thematic analysis as part of a dissertation or thesis, this discussion will be split across your methodology, results and discussion chapters . For more information about those chapters, check out our detailed post about dissertation structure .

It’s absolutely vital that, when writing up your results, you back up every single one of your findings with quotations . The reader needs to be able to see that what you’re reporting actually exists within the results. Also make sure that, when reporting your findings, you tie them back to your research questions . You don’t want your reader to be looking through your findings and asking, “So what?”, so make sure that every finding you represent is relevant to your research topic and questions.

Quick Recap: How to “do” thematic analysis

Getting familiar with your data: Here you’ll read through your data and get a general overview of what you’re working with. At this stage, you may identify a few general codes and themes that you’ll make use of in the next step.

Search for patterns or themes in your codes : Here you’ll dive into your data and pick out the themes and codes relevant to your research question(s).

Review themes : In this step, you’ll revisit your codes and themes to make sure that they are all truly representative of the data, and that you can use them in your final report.

Finalise themes : Here’s where you “solidify” your analysis and make it report-ready by describing and defining your themes.

Produce your report : This is the final step of your thematic analysis process, where you put everything you’ve found together and report on your findings.

Tips & Suggestions

In the video below, we share 6 time-saving tips and tricks to help you approach your thematic analysis as effectively and efficiently as possible.

Wrapping Up

In this article, we’ve covered the basics of thematic analysis – what it is, when to use it, the different approaches and types of thematic analysis, and how to perform a thematic analysis.

If you have any questions about thematic analysis, drop a comment below and we’ll do our best to assist. If you’d like 1-on-1 support with your thematic analysis, be sure to check out our research coaching services here .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

21 Comments

I really appreciate the help

Hello Sir, how many levels of coding can be done in thematic analysis? We generate codes from the transcripts, then subthemes from the codes and themes from subthemes, isn’t it? Should these themes be again grouped together? how many themes can be derived?can you please share an example of coding through thematic analysis in a tabular format?

I’ve found the article very educative and useful

Excellent. Very helpful and easy to understand.

This article so far has been most helpful in understanding how to write an analysis chapter. Thank you.

My research topic is the challenges face by the school principal on the process of procurement . Thematic analysis is it sutable fir data analysis ?

It is a great help. Thanks.

Best advice. Worth reading. Thank you.

Where can I find an example of a template analysis table ?

Finally I got the best article . I wish they also have every psychology topics.

Hello, Sir/Maam

I am actually finding difficulty in doing qualitative analysis of my data and how to triangulate this with quantitative data. I encountered your web by accident in the process of searching for a much simplified way of explaining about thematic analysis such as coding, thematic analysis, write up. When your query if I need help popped up, I was hesitant to answer. Because I think this is for fee and I cannot afford. So May I just ask permission to copy for me to read and guide me to study so I can apply it myself for my gathered qualitative data for my graduate study.

Thank you very much! this is very helpful to me in my Graduate research qualitative data analysis.

Thank you very much. I find your guidance here helpful. Kindly let help me understand how to write findings and discussions.

i am having troubles with the concept of framework analysis which i did not find here and i have been an assignment on framework analysis

I was discouraged and felt insecure because after more than a year of writing my thesis, my work seemed lost its direction after being checked. But, I am truly grateful because through the comments, corrections, and guidance of the wisdom of my director, I can already see the bright light because of thematic analysis. I am working with Biblical Texts. And thematic analysis will be my method. Thank you.

lovely and helpful. thanks

very informative information.

thank you very much!, this is very helpful in my report, God bless……..

Thank you for the insight. I am really relieved as you have provided a super guide for my thesis.

Thanks a lot, really enlightening

excellent! very helpful thank a lot for your great efforts

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- How to Do Thematic Analysis | Guide & Examples

How to Do Thematic Analysis | Guide & Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Jack Caulfield .

Thematic analysis is a method of analysing qualitative data . It is usually applied to a set of texts, such as an interview or transcripts . The researcher closely examines the data to identify common themes, topics, ideas and patterns of meaning that come up repeatedly.

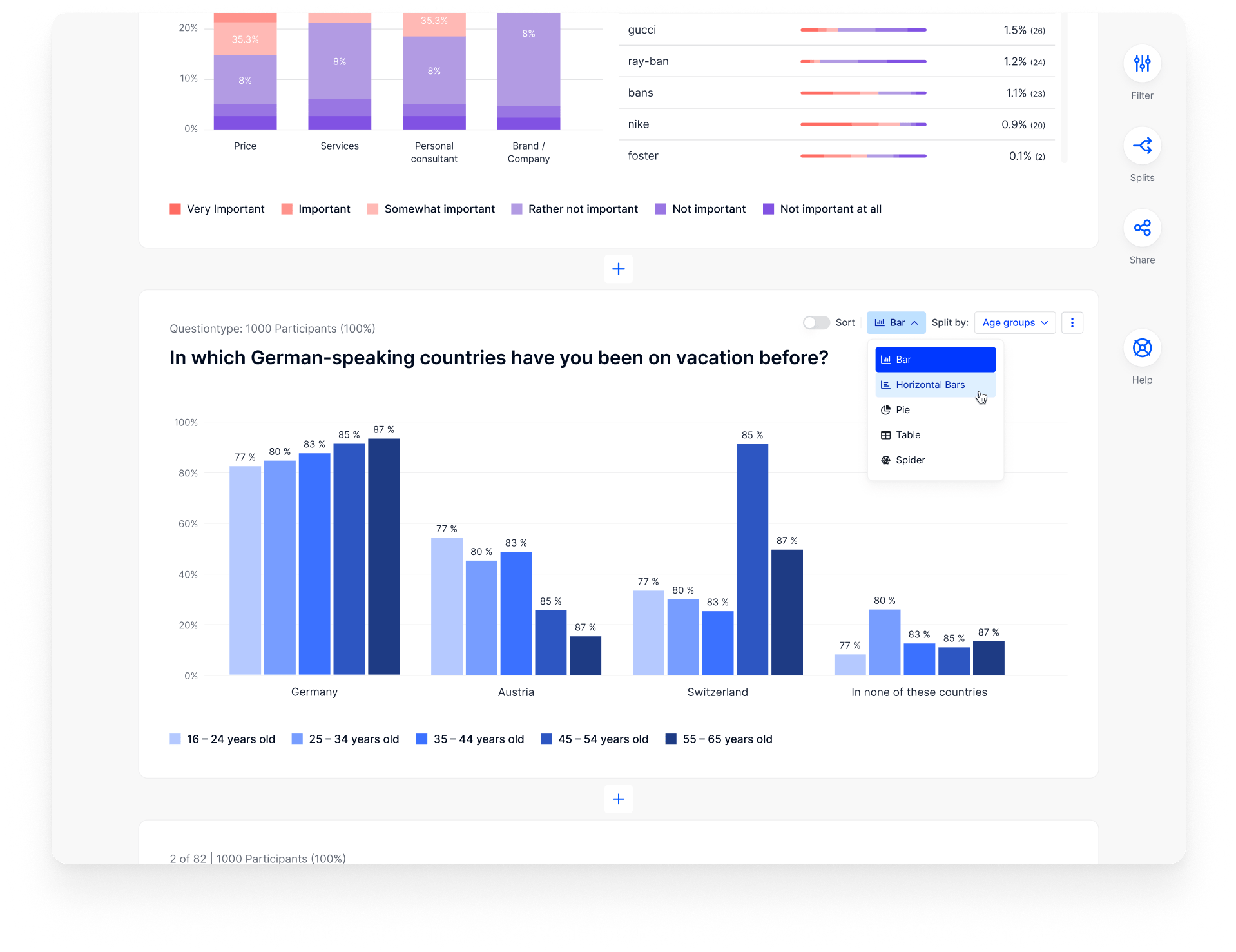

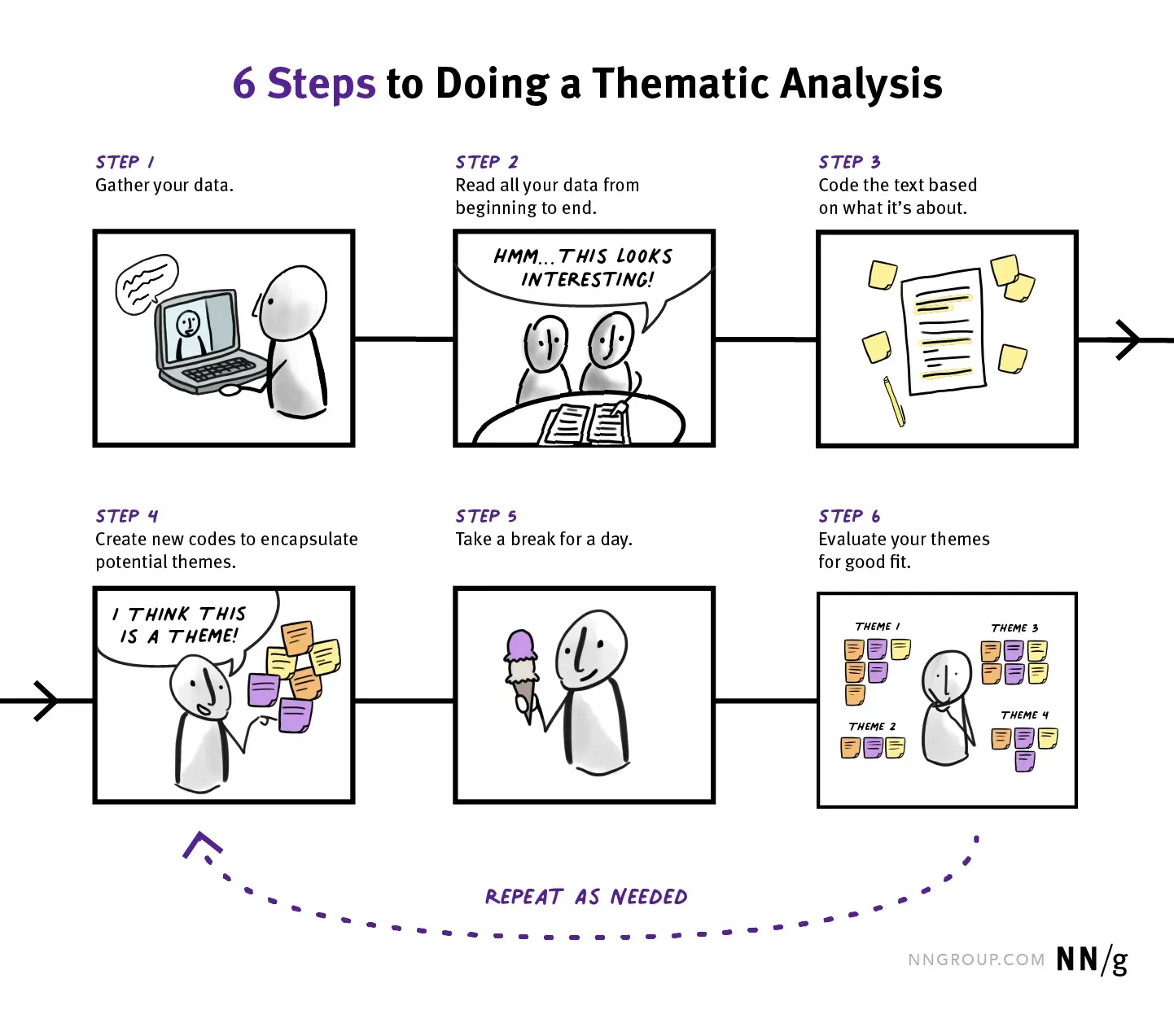

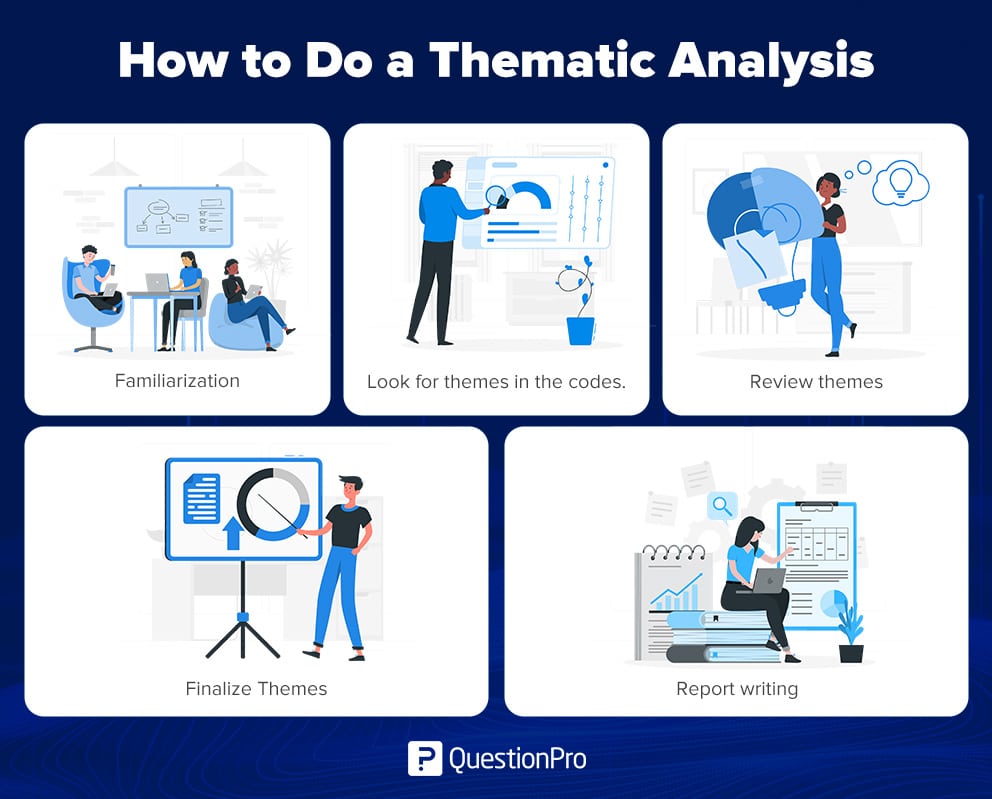

There are various approaches to conducting thematic analysis, but the most common form follows a six-step process:

- Familiarisation

- Generating themes

- Reviewing themes

- Defining and naming themes

This process was originally developed for psychology research by Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke . However, thematic analysis is a flexible method that can be adapted to many different kinds of research.

Table of contents

When to use thematic analysis, different approaches to thematic analysis, step 1: familiarisation, step 2: coding, step 3: generating themes, step 4: reviewing themes, step 5: defining and naming themes, step 6: writing up.

Thematic analysis is a good approach to research where you’re trying to find out something about people’s views, opinions, knowledge, experiences, or values from a set of qualitative data – for example, interview transcripts , social media profiles, or survey responses .

Some types of research questions you might use thematic analysis to answer:

- How do patients perceive doctors in a hospital setting?

- What are young women’s experiences on dating sites?

- What are non-experts’ ideas and opinions about climate change?

- How is gender constructed in secondary school history teaching?

To answer any of these questions, you would collect data from a group of relevant participants and then analyse it. Thematic analysis allows you a lot of flexibility in interpreting the data, and allows you to approach large datasets more easily by sorting them into broad themes.

However, it also involves the risk of missing nuances in the data. Thematic analysis is often quite subjective and relies on the researcher’s judgement, so you have to reflect carefully on your own choices and interpretations.

Pay close attention to the data to ensure that you’re not picking up on things that are not there – or obscuring things that are.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Once you’ve decided to use thematic analysis, there are different approaches to consider.

There’s the distinction between inductive and deductive approaches:

- An inductive approach involves allowing the data to determine your themes.

- A deductive approach involves coming to the data with some preconceived themes you expect to find reflected there, based on theory or existing knowledge.

There’s also the distinction between a semantic and a latent approach:

- A semantic approach involves analysing the explicit content of the data.

- A latent approach involves reading into the subtext and assumptions underlying the data.

After you’ve decided thematic analysis is the right method for analysing your data, and you’ve thought about the approach you’re going to take, you can follow the six steps developed by Braun and Clarke .

The first step is to get to know our data. It’s important to get a thorough overview of all the data we collected before we start analysing individual items.

This might involve transcribing audio , reading through the text and taking initial notes, and generally looking through the data to get familiar with it.

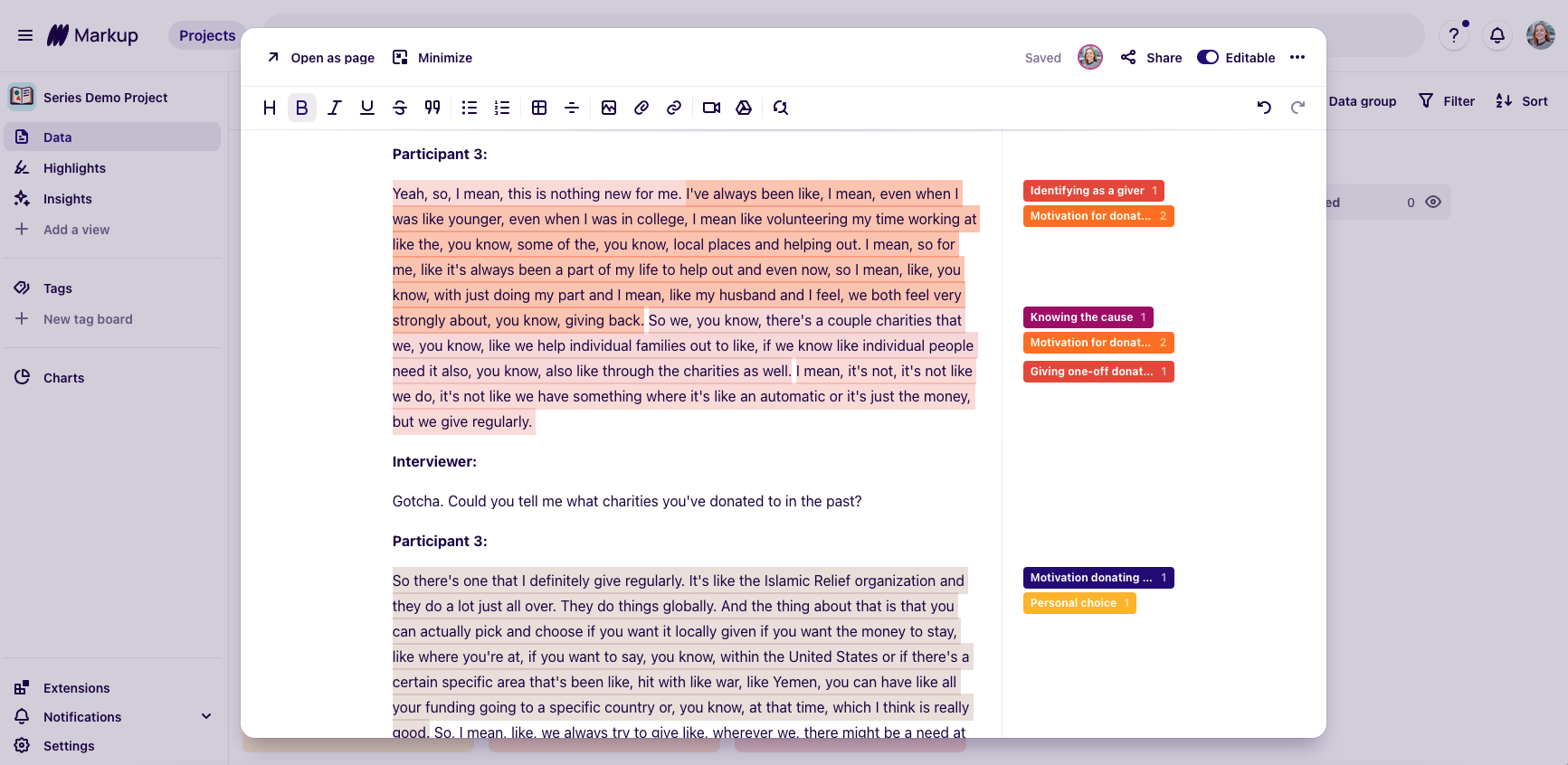

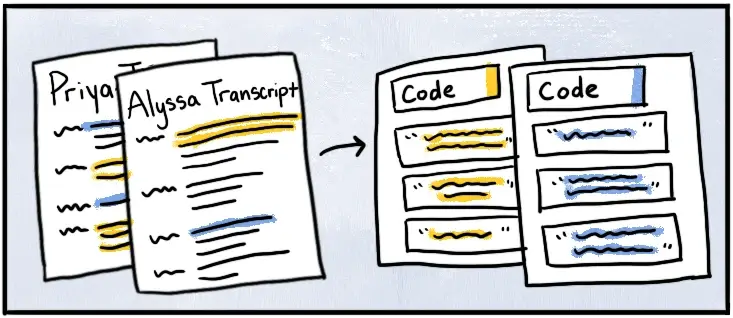

Next up, we need to code the data. Coding means highlighting sections of our text – usually phrases or sentences – and coming up with shorthand labels or ‘codes’ to describe their content.

Let’s take a short example text. Say we’re researching perceptions of climate change among conservative voters aged 50 and up, and we have collected data through a series of interviews. An extract from one interview looks like this:

In this extract, we’ve highlighted various phrases in different colours corresponding to different codes. Each code describes the idea or feeling expressed in that part of the text.

At this stage, we want to be thorough: we go through the transcript of every interview and highlight everything that jumps out as relevant or potentially interesting. As well as highlighting all the phrases and sentences that match these codes, we can keep adding new codes as we go through the text.

After we’ve been through the text, we collate together all the data into groups identified by code. These codes allow us to gain a condensed overview of the main points and common meanings that recur throughout the data.

Next, we look over the codes we’ve created, identify patterns among them, and start coming up with themes.

Themes are generally broader than codes. Most of the time, you’ll combine several codes into a single theme. In our example, we might start combining codes into themes like this:

At this stage, we might decide that some of our codes are too vague or not relevant enough (for example, because they don’t appear very often in the data), so they can be discarded.

Other codes might become themes in their own right. In our example, we decided that the code ‘uncertainty’ made sense as a theme, with some other codes incorporated into it.

Again, what we decide will vary according to what we’re trying to find out. We want to create potential themes that tell us something helpful about the data for our purposes.

Now we have to make sure that our themes are useful and accurate representations of the data. Here, we return to the dataset and compare our themes against it. Are we missing anything? Are these themes really present in the data? What can we change to make our themes work better?

If we encounter problems with our themes, we might split them up, combine them, discard them, or create new ones: whatever makes them more useful and accurate.

For example, we might decide upon looking through the data that ‘changing terminology’ fits better under the ‘uncertainty’ theme than under ‘distrust of experts’, since the data labelled with this code involves confusion, not necessarily distrust.

Now that you have a final list of themes, it’s time to name and define each of them.

Defining themes involves formulating exactly what we mean by each theme and figuring out how it helps us understand the data.

Naming themes involves coming up with a succinct and easily understandable name for each theme.

For example, we might look at ‘distrust of experts’ and determine exactly who we mean by ‘experts’ in this theme. We might decide that a better name for the theme is ‘distrust of authority’ or ‘conspiracy thinking’.

Finally, we’ll write up our analysis of the data. Like all academic texts, writing up a thematic analysis requires an introduction to establish our research question, aims, and approach.

We should also include a methodology section, describing how we collected the data (e.g., through semi-structured interviews or open-ended survey questions ) and explaining how we conducted the thematic analysis itself.

The results or findings section usually addresses each theme in turn. We describe how often the themes come up and what they mean, including examples from the data as evidence. Finally, our conclusion explains the main takeaways and shows how the analysis has answered our research question.

In our example, we might argue that conspiracy thinking about climate change is widespread among older conservative voters, point out the uncertainty with which many voters view the issue, and discuss the role of misinformation in respondents’ perceptions.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2022, May 05). How to Do Thematic Analysis | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 22 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/thematic-analysis-explained/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods, inductive reasoning | types, examples, explanation, what is deductive reasoning | explanation & examples.

How to do thematic analysis

Last updated

8 February 2023

Reviewed by

Miroslav Damyanov

Uncovering themes in data requires a systematic approach. Thematic analysis organizes data so you can easily recognize the context.

- What is thematic analysis?

Thematic analysis is a method for analyzing qualitative data that involves reading through a data set and looking for patterns to derive themes . The researcher's subjective experience plays a central role in finding meaning within the data.

Streamline your thematic analysis

Find patterns and themes across all your qualitative data when you analyze it in Dovetail

- What are the main approaches to thematic analysis?

Inductive thematic analysis approach

Inductive thematic analysis entails deriving meaning and identifying themes from data with no preconceptions. You analyze the data without any expected outcomes.

Deductive thematic analysis approach

In the deductive approach, you analyze data with a set of expected themes. Prior knowledge, research, or existing theory informs this approach.

Semantic thematic analysis approach

With the semantic approach, you ignore the underlying meaning of data. You take identifying themes at face value based on what is written or explicitly stated.

Latent thematic analysis approach

Unlike the semantic approach, the latent approach focuses on underlying meanings in data and looks at the reasons for semantic content. It involves an element of interpretation where you theorize meanings and don’t just take data at face value.

- When should thematic analysis be used?

Thematic analysis is beneficial when you’re working with large bodies of data. It allows you to divide and categorize huge quantities of data in a way that makes it far easier to digest.

The following scenarios warrant the use of thematic analysis:

You’re new to qualitative analysis

You need to identify patterns in data

You want to involve participants in the process

Thematic analysis is particularly useful when you’re looking for subjective information such as experiences and opinions in surveys , interviews, conversations, or social media posts.

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of thematic analysis?

Thematic analysis is a highly flexible approach to qualitative data analysis that you can modify to meet the needs of many studies. It enables you to generate new insights and concepts from data.

Beginner researchers who are just learning how to analyze data will find thematic analysis very accessible. It’s easy for most people to grasp and can be relatively quick to learn.

The flexibility of thematic analysis can also be a disadvantage. It can feel intimidating to decide what’s important to emphasize, as there are many ways to interpret meaning from a data set.

- What is the step-by-step process for thematic analysis?

The basic thematic analysis process requires recognizing codes and themes within a data set. A code is a label assigned to a piece of data that you use to identify and summarize important concepts within a data set. A theme is a pattern that you identify within the data. Relevant steps may vary based on the approach and type of thematic analysis, but these are the general steps you’d take:

1. Familiarize yourself with the data(pre-coding work)

Before you can successfully work with data, you need to understand it. Get a feel for the data to see what general themes pop up. Transcribe audio files and observe any meanings and patterns across the data set. Read through the transcript, and jot down notes about potential codes to create.

2. Create the initial codes (open code work)

Create a set of initial codes to represent the patterns and meanings in the data. Make a codebook to keep track of the codes. Read through the data again to identify interesting excerpts and apply the appropriate codes. You should use the same code to represent excerpts with the same meaning.

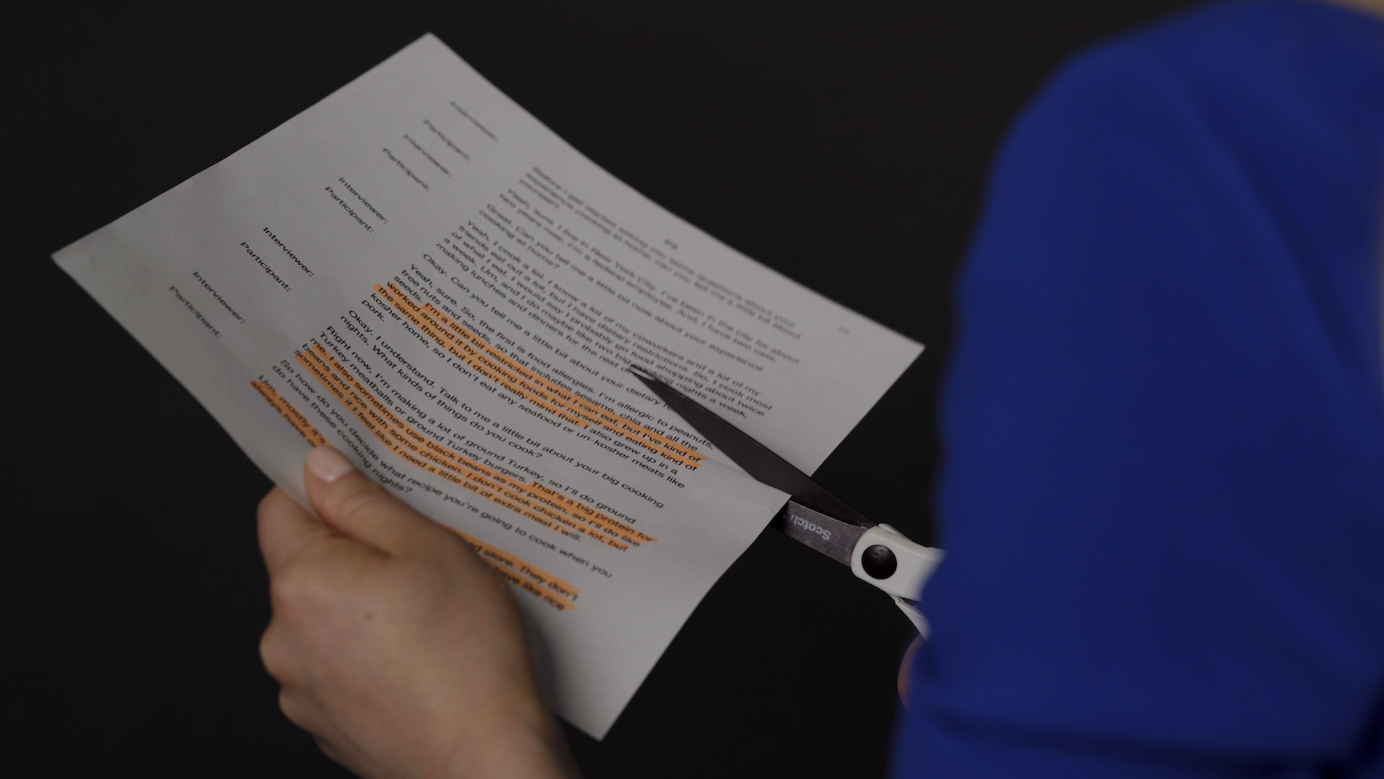

3. Collate codes with supporting data (clustering of initial code)

Now it's time to group all excerpts associated with a particular code. If you’re doing this manually, cut out codes and put them together. Thematic analysis software will automatically collate them.

4. Group codes into themes (clustering of selective codes)

Once you’ve finalized the codes, you can sort them into potential themes. Themes reflect trends and patterns in data. You can combine some codes to create sub-themes.

5. Review, revise, and finalize the themes (final revision)

Now you’ve decided upon the initial themes, you can review and adjust them as needed. Each theme should be distinct, with enough data to support it. You can merge similar themes and remove those lacking sufficient supportive data. Begin formulating themes into a narrative.

6. Write the report

The final step of telling the story of a set of data is writing the report. You should fully consider the themes to communicate the validity of your analysis.

A typical thematic analysis report contains the following:

An introduction

A methodology section

Results and findings

A conclusion

Your narrative must be coherent, and it should include vivid quotes that can back up points. It should also include an interpretive analysis and argument for your claims. In addition, consider reporting your findings in a flowchart or tree diagram, which can be independent of or part of your report.

In conclusion, a thematic analysis is a method of analyzing qualitative data. By following the six steps, you will identify common themes from a large set of texts. This method can help you find rich and useful insights about people’s experiences, behaviors, and nuanced opinions.

- How to analyze qualitative data

Qualitative data analysis is the process of organizing, analyzing, and interpreting non-numerical and subjective data . The goal is to capture themes and patterns, answer questions, and identify the best actions to take based on that data.

Researchers can use qualitative data to understand people’s thoughts, feelings, and attitudes. For example, qualitative researchers can help business owners draw reliable conclusions about customers’ opinions and discover areas that need improvement.

In addition to thematic analysis, you can analyze qualitative data using the following:

Content analysis

Content analysis examines and counts the presence of certain words, subjects, and contexts in documents and communication artifacts, such as:

Text in various formats

This method transforms qualitative input into quantitative data. You can do it manually or with electronic tools that recognize patterns to make connections between concepts.

Narrative analysis

Narrative analysis interprets research participants' stories from testimonials, case studies, interviews, and other text or visual data. It provides valuable insights into the complexity of people's feelings, beliefs, and behaviors.

Discourse analysis

In discourse analysis , you analyze the underlying meaning of qualitative data in a particular context, including:

Historical

This approach allows us to study how people use language in text, audio, and video to unravel social issues, power dynamics, or inequalities.

For example, you can look at how people communicate with their coworkers versus their bosses. Discourse analysis goes beyond the literal meaning of words to examine social reality.

Grounded theory analysis

In grounded theory analysis, you develop theories by examining real-world data. The process involves creating hypotheses and theories by systematically collecting and evaluating this data. While this approach is helpful for studying lesser-known phenomena, it might be overwhelming for a novice researcher.

- Challenges with analyzing qualitative data

While qualitative data can answer questions that quantitative data can't, it still comes with challenges.

If done manually, qualitative data analysis is very time-consuming.

It can be hard to choose a method.

Avoiding bias is difficult.

Human error affects accuracy and consistency.

To overcome these challenges, you should fine-tune your methods by using the appropriate tools in collaboration with teammates.

Learn more about thematic analysis software

What is thematic analysis in qualitative research.

Thematic analysis is a method of analyzing qualitative data. It is applied to texts, such as interviews or transcripts. The researcher closely examines the data to identify common patterns and themes.

Can thematic analysis be done manually?

You can do thematic analysis manually, but it is very time-consuming without the help of software.

What are the two types of thematic analysis?

The two main types of thematic analysis include codebook thematic analysis and reflexive thematic analysis.

Codebook thematic analysis uses predetermined codes and structured codebooks to analyze from a deductive perspective. You draw codes from a review of the data or an initial analysis to produce the codebooks.

Reflexive thematic analysis is more flexible and does not use a codebook. Researchers can change, remove, and add codes as they work through the data.

What makes a good thematic analysis?

The goal of thematic analysis is more than simply summarizing data; it's about identifying important themes. Good thematic analysis interprets, makes sense of data, and explains it. It produces trustworthy and insightful findings that are easy to understand and apply.

What are examples of themes in thematic analysis?

Grouping codes into themes summarize sections of data in a useful way to answer research questions and achieve objectives. A theme identifies an area of data and tells the reader something about it. A good theme can sit alone without requiring descriptive text beneath it.

For example, if you were analyzing data on wildlife, codes might be owls, hawks, and falcons. These codes might fall beneath the theme of birds of prey. If your data were about the latest trends for teenage girls, codes such as mini skirts, leggings, and distressed jeans would fall under fashion.

Thematic analysis is straightforward and intuitive enough that most people have no trouble applying it.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- How it works

Thematic Analysis – A Guide with Examples

Published by Alvin Nicolas at August 16th, 2021 , Revised On August 29, 2023

Thematic analysis is one of the most important types of analysis used for qualitative data . When researchers have to analyse audio or video transcripts, they give preference to thematic analysis. A researcher needs to look keenly at the content to identify the context and the message conveyed by the speaker.

Moreover, with the help of this analysis, data can be simplified.

Importance of Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis has so many unique and dynamic features, some of which are given below:

Thematic analysis is used because:

- It is flexible.

- It is best for complex data sets.

- It is applied to qualitative data sets.

- It takes less complexity compared to other theories of analysis.

Intellectuals and researchers give preference to thematic analysis due to its effectiveness in the research.

How to Conduct a Thematic Analysis?

While doing any research , if your data and procedure are clear, it will be easier for your reader to understand how you concluded the results . This will add much clarity to your research.

Understand the Data

This is the first step of your thematic analysis. At this stage, you have to understand the data set. You need to read the entire data instead of reading the small portion. If you do not have the data in the textual form, you have to transcribe it.

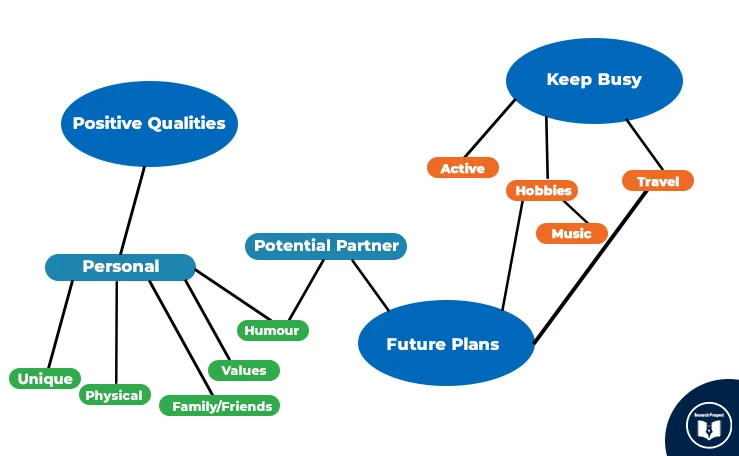

Example: If you are visiting an adult dating website, you have to make a data corpus. You should read and re-read the data and consider several profiles. It will give you an idea of how adults represent themselves on dating sites. You may get the following results:

I am a tall, single(widowed), easy-going, honest, good listener with a good sense of humor. Being a handyperson, I keep busy working around the house, and I also like to follow my favourite hockey team on TV or spoil my two granddaughters when I get the chance!! Enjoy most music except Rap! I keep fit by jogging, walking, and bicycling (at least three times a week). I have travelled to many places and RVD the South-West U.S., but I would now like to find that special travel partner to do more travel to warm and interesting countries. I now feel it’s time to meet a nice, kind, honest woman who has some of the same interests as I do; to share the happy times, quiet times, and adventures together

I enjoy photography, lapidary & seeking collectibles in the form of classic movies & 33 1/3, 45 & 78 RPM recordings from the 1920s, ’30s & ’40s. I am retired & looking forward to travelling to Canada, the USA, the UK & Europe, China. I am unique since I do not judge a book by its cover. I accept people for who they are. I will not demand or request perfection from anyone until I am perfect, so I guess that means everyone is safe. My musical tastes range from Classical, big band era, early jazz, classic ’50s & 60’s rock & roll & country since its inception.

Development of Initial Coding:

At this stage, you have to do coding. It’s the essential step of your research . Here you have two options for coding. Either you can do the coding manually or take the help of any tool. A software named the NOVIC is considered the best tool for doing automatic coding.

For manual coding, you can follow the steps given below:

- Please write down the data in a proper format so that it can be easier to proceed.

- Use a highlighter to highlight all the essential points from data.

- Make as many points as possible.

- Take notes very carefully at this stage.

- Apply themes as much possible.

- Now check out the themes of the same pattern or concept.

- Turn all the same themes into the single one.

Example: For better understanding, the previously explained example of Step 1 is continued here. You can observe the coded profiles below:

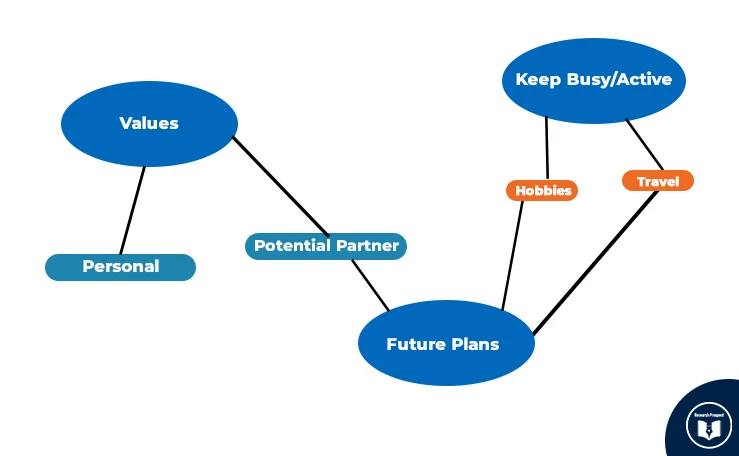

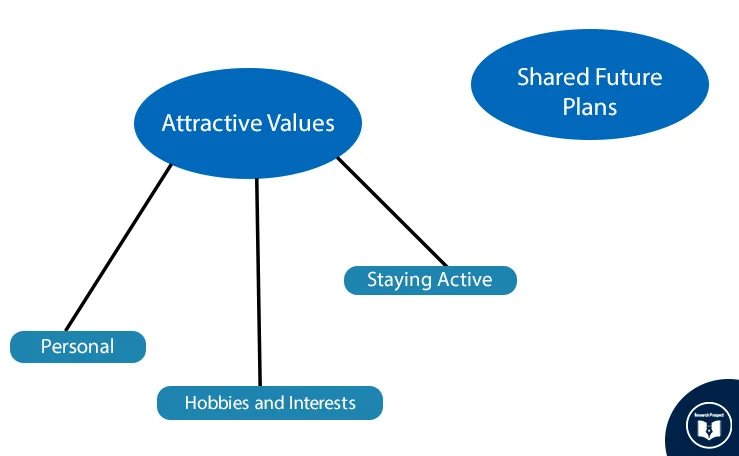

Make Themes

At this stage, you have to make the themes. These themes should be categorised based on the codes. All the codes which have previously been generated should be turned into themes. Moreover, with the help of the codes, some themes and sub-themes can also be created. This process is usually done with the help of visuals so that a reader can take an in-depth look at first glance itself.

Extracted Data Review

Now you have to take an in-depth look at all the awarded themes again. You have to check whether all the given themes are organised properly or not. It would help if you were careful and focused because you have to note down the symmetry here. If you find that all the themes are not coherent, you can revise them. You can also reshape the data so that there will be symmetry between the themes and dataset here.

For better understanding, a mind-mapping example is given here:

Reviewing all the Themes Again

You need to review the themes after coding them. At this stage, you are allowed to play with your themes in a more detailed manner. You have to convert the bigger themes into smaller themes here. If you want to combine some similar themes into a single theme, then you can do it. This step involves two steps for better fragmentation.

You need to observe the coded data separately so that you can have a precise view. If you find that the themes which are given are following the dataset, it’s okay. Otherwise, you may have to rearrange the data again to coherence in the coded data.

Corpus Data

Here you have to take into consideration all the corpus data again. It would help if you found how themes are arranged here. It would help if you used the visuals to check out the relationship between them. Suppose all the things are not done accordingly, so you should check out the previous steps for a refined process. Otherwise, you can move to the next step. However, make sure that all the themes are satisfactory and you are not confused.

When all the two steps are completed, you need to make a more précised mind map. An example following the previous cases has been given below:

Define all the Themes here

Now you have to define all the themes which you have given to your data set. You can recheck them carefully if you feel that some of them can fit into one concept, you can keep them, and eliminate the other irrelevant themes. Because it should be precise and clear, there should not be any ambiguity. Now you have to think about the main idea and check out that all the given themes are parallel to your main idea or not. This can change the concept for you.

The given names should be so that it can give any reader a clear idea about your findings. However, it should not oppose your thematic analysis; rather, everything should be organised accurately.

Does your Research Methodology Have the Following?

- Great Research/Sources

- Perfect Language

- Accurate Sources

If not, we can help. Our panel of experts makes sure to keep the 3 pillars of Research Methodology strong.

Also, read about discourse analysis , content analysis and survey conducting . we have provided comprehensive guides.

Make a Report

You need to make the final report of all the findings you have done at this stage. You should include the dataset, findings, and every aspect of your analysis in it.

While making the final report , do not forget to consider your audience. For instance, you are writing for the Newsletter, Journal, Public awareness, etc., your report should be according to your audience. It should be concise and have some logic; it should not be repetitive. You can use the references of other relevant sources as evidence to support your discussion.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is meant by thematic analysis.

Thematic Analysis is a qualitative research method that involves identifying, analyzing, and interpreting recurring themes or patterns in data. It aims to uncover underlying meanings, ideas, and concepts within the dataset, providing insights into participants’ perspectives and experiences.

You May Also Like

You can transcribe an interview by converting a conversation into a written format including question-answer recording sessions between two or more people.

A case study is a detailed analysis of a situation concerning organizations, industries, and markets. The case study generally aims at identifying the weak areas.

Discourse analysis is an essential aspect of studying a language. It is used in various disciplines of social science and humanities such as linguistic, sociolinguistics, and psycholinguistic.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Practical thematic...

Practical thematic analysis: a guide for multidisciplinary health services research teams engaging in qualitative analysis

- Related content

- Peer review

- Catherine H Saunders , scientist and assistant professor 1 2 ,

- Ailyn Sierpe , research project coordinator 2 ,

- Christian von Plessen , senior physician 3 ,

- Alice M Kennedy , research project manager 2 4 ,

- Laura C Leviton , senior adviser 5 ,

- Steven L Bernstein , chief research officer 1 ,

- Jenaya Goldwag , resident physician 1 ,

- Joel R King , research assistant 2 ,

- Christine M Marx , patient associate 6 ,

- Jacqueline A Pogue , research project manager 2 ,

- Richard K Saunders , staff physician 1 ,

- Aricca Van Citters , senior research scientist 2 ,

- Renata W Yen , doctoral student 2 ,

- Glyn Elwyn , professor 2 ,

- JoAnna K Leyenaar , associate professor 1 2

- on behalf of the Coproduction Laboratory

- 1 Dartmouth Health, Lebanon, NH, USA

- 2 Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College, Lebanon, NH, USA

- 3 Center for Primary Care and Public Health (Unisanté), Lausanne, Switzerland

- 4 Jönköping Academy for Improvement of Health and Welfare, School of Health and Welfare, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden

- 5 Highland Park, NJ, USA

- 6 Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO, USA

- Correspondence to: C H Saunders catherine.hylas.saunders{at}dartmouth.edu

- Accepted 26 April 2023

Qualitative research methods explore and provide deep contextual understanding of real world issues, including people’s beliefs, perspectives, and experiences. Whether through analysis of interviews, focus groups, structured observation, or multimedia data, qualitative methods offer unique insights in applied health services research that other approaches cannot deliver. However, many clinicians and researchers hesitate to use these methods, or might not use them effectively, which can leave relevant areas of inquiry inadequately explored. Thematic analysis is one of the most common and flexible methods to examine qualitative data collected in health services research. This article offers practical thematic analysis as a step-by-step approach to qualitative analysis for health services researchers, with a focus on accessibility for patients, care partners, clinicians, and others new to thematic analysis. Along with detailed instructions covering three steps of reading, coding, and theming, the article includes additional novel and practical guidance on how to draft effective codes, conduct a thematic analysis session, and develop meaningful themes. This approach aims to improve consistency and rigor in thematic analysis, while also making this method more accessible for multidisciplinary research teams.

Through qualitative methods, researchers can provide deep contextual understanding of real world issues, and generate new knowledge to inform hypotheses, theories, research, and clinical care. Approaches to data collection are varied, including interviews, focus groups, structured observation, and analysis of multimedia data, with qualitative research questions aimed at understanding the how and why of human experience. 1 2 Qualitative methods produce unique insights in applied health services research that other approaches cannot deliver. In particular, researchers acknowledge that thematic analysis is a flexible and powerful method of systematically generating robust qualitative research findings by identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data. 3 4 5 6 Although qualitative methods are increasingly valued for answering clinical research questions, many researchers are unsure how to apply them or consider them too time consuming to be useful in responding to practical challenges 7 or pressing situations such as public health emergencies. 8 Consequently, researchers might hesitate to use them, or use them improperly. 9 10 11

Although much has been written about how to perform thematic analysis, practical guidance for non-specialists is sparse. 3 5 6 12 13 In the multidisciplinary field of health services research, qualitative data analysis can confound experienced researchers and novices alike, which can stoke concerns about rigor, particularly for those more familiar with quantitative approaches. 14 Since qualitative methods are an area of specialisation, support from experts is beneficial. However, because non-specialist perspectives can enhance data interpretation and enrich findings, there is a case for making thematic analysis easier, more rapid, and more efficient, 8 particularly for patients, care partners, clinicians, and other stakeholders. A practical guide to thematic analysis might encourage those on the ground to use these methods in their work, unearthing insights that would otherwise remain undiscovered.

Given the need for more accessible qualitative analysis approaches, we present a simple, rigorous, and efficient three step guide for practical thematic analysis. We include new guidance on the mechanics of thematic analysis, including developing codes, constructing meaningful themes, and hosting a thematic analysis session. We also discuss common pitfalls in thematic analysis and how to avoid them.

Summary points

Qualitative methods are increasingly valued in applied health services research, but multidisciplinary research teams often lack accessible step-by-step guidance and might struggle to use these approaches

A newly developed approach, practical thematic analysis, uses three simple steps: reading, coding, and theming

Based on Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis, our streamlined yet rigorous approach is designed for multidisciplinary health services research teams, including patients, care partners, and clinicians

This article also provides companion materials including a slide presentation for teaching practical thematic analysis to research teams, a sample thematic analysis session agenda, a theme coproduction template for use during the session, and guidance on using standardised reporting criteria for qualitative research

In their seminal work, Braun and Clarke developed a six phase approach to reflexive thematic analysis. 4 12 We built on their method to develop practical thematic analysis ( box 1 , fig 1 ), which is a simplified and instructive approach that retains the substantive elements of their six phases. Braun and Clarke’s phase 1 (familiarising yourself with the dataset) is represented in our first step of reading. Phase 2 (coding) remains as our second step of coding. Phases 3 (generating initial themes), 4 (developing and reviewing themes), and 5 (refining, defining, and naming themes) are represented in our third step of theming. Phase 6 (writing up) also occurs during this third step of theming, but after a thematic analysis session. 4 12

Key features and applications of practical thematic analysis

Step 1: reading.

All manuscript authors read the data

All manuscript authors write summary memos

Step 2: Coding

Coders perform both data management and early data analysis

Codes are complete thoughts or sentences, not categories

Step 3: Theming

Researchers host a thematic analysis session and share different perspectives

Themes are complete thoughts or sentences, not categories

Applications

For use by practicing clinicians, patients and care partners, students, interdisciplinary teams, and those new to qualitative research

When important insights from healthcare professionals are inaccessible because they do not have qualitative methods training

When time and resources are limited

Steps in practical thematic analysis

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

We present linear steps, but as qualitative research is usually iterative, so too is thematic analysis. 15 Qualitative researchers circle back to earlier work to check whether their interpretations still make sense in the light of additional insights, adapting as necessary. While we focus here on the practical application of thematic analysis in health services research, we recognise our approach exists in the context of the broader literature on thematic analysis and the theoretical underpinnings of qualitative methods as a whole. For a more detailed discussion of these theoretical points, as well as other methods widely used in health services research, we recommend reviewing the sources outlined in supplemental material 1. A strong and nuanced understanding of the context and underlying principles of thematic analysis will allow for higher quality research. 16

Practical thematic analysis is a highly flexible approach that can draw out valuable findings and generate new hypotheses, including in cases with a lack of previous research to build on. The approach can also be used with a variety of data, such as transcripts from interviews or focus groups, patient encounter transcripts, professional publications, observational field notes, and online activity logs. Importantly, successful practical thematic analysis is predicated on having high quality data collected with rigorous methods. We do not describe qualitative research design or data collection here. 11 17

In supplemental material 1, we summarise the foundational methods, concepts, and terminology in qualitative research. Along with our guide below, we include a companion slide presentation for teaching practical thematic analysis to research teams in supplemental material 2. We provide a theme coproduction template for teams to use during thematic analysis sessions in supplemental material 3. Our method aligns with the major qualitative reporting frameworks, including the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ). 18 We indicate the corresponding step in practical thematic analysis for each COREQ item in supplemental material 4.

Familiarisation and memoing

We encourage all manuscript authors to review the full dataset (eg, interview transcripts) to familiarise themselves with it. This task is most critical for those who will later be engaged in the coding and theming steps. Although time consuming, it is the best way to involve team members in the intellectual work of data interpretation, so that they can contribute to the analysis and contextualise the results. If this task is not feasible given time limitations or large quantities of data, the data can be divided across team members. In this case, each piece of data should be read by at least two individuals who ideally represent different professional roles or perspectives.

We recommend that researchers reflect on the data and independently write memos, defined as brief notes on thoughts and questions that arise during reading, and a summary of their impressions of the dataset. 2 19 Memoing is an opportunity to gain insights from varying perspectives, particularly from patients, care partners, clinicians, and others. It also gives researchers the opportunity to begin to scope which elements of and concepts in the dataset are relevant to the research question.

Data saturation

The concept of data saturation ( box 2 ) is a foundation of qualitative research. It is defined as the point in analysis at which new data tend to be redundant of data already collected. 21 Qualitative researchers are expected to report their approach to data saturation. 18 Because thematic analysis is iterative, the team should discuss saturation throughout the entire process, beginning with data collection and continuing through all steps of the analysis. 22 During step 1 (reading), team members might discuss data saturation in the context of summary memos. Conversations about saturation continue during step 2 (coding), with confirmation that saturation has been achieved during step 3 (theming). As a rule of thumb, researchers can often achieve saturation in 9-17 interviews or 4-8 focus groups, but this will vary depending on the specific characteristics of the study. 23

Data saturation in context

Braun and Clarke discourage the use of data saturation to determine sample size (eg, number of interviews), because it assumes that there is an objective truth to be captured in the data (sometimes known as a positivist perspective). 20 Qualitative researchers often try to avoid positivist approaches, arguing that there is no one true way of seeing the world, and will instead aim to gather multiple perspectives. 5 Although this theoretical debate with qualitative methods is important, we recognise that a priori estimates of saturation are often needed, particularly for investigators newer to qualitative research who might want a more pragmatic and applied approach. In addition, saturation based, sample size estimation can be particularly helpful in grant proposals. However, researchers should still follow a priori sample size estimation with a discussion to confirm saturation has been achieved.

Definition of coding

We describe codes as labels for concepts in the data that are directly relevant to the study objective. Historically, the purpose of coding was to distil the large amount of data collected into conceptually similar buckets so that researchers could review it in aggregate and identify key themes. 5 24 We advocate for a more analytical approach than is typical with thematic analysis. With our method, coding is both the foundation for and the beginning of thematic analysis—that is, early data analysis, management, and reduction occur simultaneously rather than as different steps. This approach moves the team more efficiently towards being able to describe themes.

Building the coding team

Coders are the research team members who directly assign codes to the data, reading all material and systematically labelling relevant data with appropriate codes. Ideally, at least two researchers would code every discrete data document, such as one interview transcript. 25 If this task is not possible, individual coders can each code a subset of the data that is carefully selected for key characteristics (sometimes known as purposive selection). 26 When using this approach, we recommend that at least 10% of data be coded by two or more coders to ensure consistency in codebook application. We also recommend coding teams of no more than four to five people, for practical reasons concerning maintaining consistency.

Clinicians, patients, and care partners bring unique perspectives to coding and enrich the analytical process. 27 Therefore, we recommend choosing coders with a mix of relevant experiences so that they can challenge and contextualise each other’s interpretations based on their own perspectives and opinions ( box 3 ). We recommend including both coders who collected the data and those who are naive to it, if possible, given their different perspectives. We also recommend all coders review the summary memos from the reading step so that key concepts identified by those not involved in coding can be integrated into the analytical process. In practice, this review means coding the memos themselves and discussing them during the code development process. This approach ensures that the team considers a diversity of perspectives.

Coding teams in context

The recommendation to use multiple coders is a departure from Braun and Clarke. 28 29 When the views, experiences, and training of each coder (sometimes known as positionality) 30 are carefully considered, having multiple coders can enhance interpretation and enrich findings. When these perspectives are combined in a team setting, researchers can create shared meaning from the data. Along with the practical consideration of distributing the workload, 31 inclusion of these multiple perspectives increases the overall quality of the analysis by mitigating the impact of any one coder’s perspective. 30

Coding tools

Qualitative analysis software facilitates coding and managing large datasets but does not perform the analytical work. The researchers must perform the analysis themselves. Most programs support queries and collaborative coding by multiple users. 32 Important factors to consider when choosing software can include accessibility, cost, interoperability, the look and feel of code reports, and the ease of colour coding and merging codes. Coders can also use low tech solutions, including highlighters, word processors, or spreadsheets.

Drafting effective codes

To draft effective codes, we recommend that the coders review each document line by line. 33 As they progress, they can assign codes to segments of data representing passages of interest. 34 Coders can also assign multiple codes to the same passage. Consensus among coders on what constitutes a minimum or maximum amount of text for assigning a code is helpful. As a general rule, meaningful segments of text for coding are shorter than one paragraph, but longer than a few words. Coders should keep the study objective in mind when determining which data are relevant ( box 4 ).

Code types in context

Similar to Braun and Clarke’s approach, practical thematic analysis does not specify whether codes are based on what is evident from the data (sometimes known as semantic) or whether they are based on what can be inferred at a deeper level from the data (sometimes known as latent). 4 12 35 It also does not specify whether they are derived from the data (sometimes known as inductive) or determined ahead of time (sometimes known as deductive). 11 35 Instead, it should be noted that health services researchers conducting qualitative studies often adopt all these approaches to coding (sometimes known as hybrid analysis). 3

In practical thematic analysis, codes should be more descriptive than general categorical labels that simply group data with shared characteristics. At a minimum, codes should form a complete (or full) thought. An easy way to conceptualise full thought codes is as complete sentences with subjects and verbs ( table 1 ), although full sentence coding is not always necessary. With full thought codes, researchers think about the data more deeply and capture this insight in the codes. This coding facilitates the entire analytical process and is especially valuable when moving from codes to broader themes. Experienced qualitative researchers often intuitively use full thought or sentence codes, but this practice has not been explicitly articulated as a path to higher quality coding elsewhere in the literature. 6

Example transcript with codes used in practical thematic analysis 36

- View inline

Depending on the nature of the data, codes might either fall into flat categories or be arranged hierarchically. Flat categories are most common when the data deal with topics on the same conceptual level. In other words, one topic is not a subset of another topic. By contrast, hierarchical codes are more appropriate for concepts that naturally fall above or below each other. Hierarchical coding can also be a useful form of data management and might be necessary when working with a large or complex dataset. 5 Codes grouped into these categories can also make it easier to naturally transition into generating themes from the initial codes. 5 These decisions between flat versus hierarchical coding are part of the work of the coding team. In both cases, coders should ensure that their code structures are guided by their research questions.

Developing the codebook

A codebook is a shared document that lists code labels and comprehensive descriptions for each code, as well as examples observed within the data. Good code descriptions are precise and specific so that coders can consistently assign the same codes to relevant data or articulate why another coder would do so. Codebook development is iterative and involves input from the entire coding team. However, as those closest to the data, coders must resist undue influence, real or perceived, from other team members with conflicting opinions—it is important to mitigate the risk that more senior researchers, like principal investigators, exert undue influence on the coders’ perspectives.

In practical thematic analysis, coders begin codebook development by independently coding a small portion of the data, such as two to three transcripts or other units of analysis. Coders then individually produce their initial codebooks. This task will require them to reflect on, organise, and clarify codes. The coders then meet to reconcile the draft codebooks, which can often be difficult, as some coders tend to lump several concepts together while others will split them into more specific codes. Discussing disagreements and negotiating consensus are necessary parts of early data analysis. Once the codebook is relatively stable, we recommend soliciting input on the codes from all manuscript authors. Yet, coders must ultimately be empowered to finalise the details so that they are comfortable working with the codebook across a large quantity of data.

Assigning codes to the data

After developing the codebook, coders will use it to assign codes to the remaining data. While the codebook’s overall structure should remain constant, coders might continue to add codes corresponding to any new concepts observed in the data. If new codes are added, coders should review the data they have already coded and determine whether the new codes apply. Qualitative data analysis software can be useful for editing or merging codes.

We recommend that coders periodically compare their code occurrences ( box 5 ), with more frequent check-ins if substantial disagreements occur. In the event of large discrepancies in the codes assigned, coders should revise the codebook to ensure that code descriptions are sufficiently clear and comprehensive to support coding alignment going forward. Because coding is an iterative process, the team can adjust the codebook as needed. 5 28 29

Quantitative coding in context

Researchers should generally avoid reporting code counts in thematic analysis. However, counts can be a useful proxy in maintaining alignment between coders on key concepts. 26 In practice, therefore, researchers should make sure that all coders working on the same piece of data assign the same codes with a similar pattern and that their memoing and overall assessment of the data are aligned. 37 However, the frequency of a code alone is not an indicator of its importance. It is more important that coders agree on the most salient points in the data; reviewing and discussing summary memos can be helpful here. 5

Researchers might disagree on whether or not to calculate and report inter-rater reliability. We note that quantitative tests for agreement, such as kappa statistics or intraclass correlation coefficients, can be distracting and might not provide meaningful results in qualitative analyses. Similarly, Braun and Clarke argue that expecting perfect alignment on coding is inconsistent with the goal of co-constructing meaning. 28 29 Overall consensus on codes’ salience and contributions to themes is the most important factor.

Definition of themes

Themes are meta-constructs that rise above codes and unite the dataset ( box 6 , fig 2 ). They should be clearly evident, repeated throughout the dataset, and relevant to the research questions. 38 While codes are often explicit descriptions of the content in the dataset, themes are usually more conceptual and knit the codes together. 39 Some researchers hypothesise that theme development is loosely described in the literature because qualitative researchers simply intuit themes during the analytical process. 39 In practical thematic analysis, we offer a concrete process that should make developing meaningful themes straightforward.

Themes in context

According to Braun and Clarke, a theme “captures something important about the data in relation to the research question and represents some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set.” 4 Similarly, Braun and Clarke advise against themes as domain summaries. While different approaches can draw out themes from codes, the process begins by identifying patterns. 28 35 Like Braun and Clarke and others, we recommend that researchers consider the salience of certain themes, their prevalence in the dataset, and their keyness (ie, how relevant the themes are to the overarching research questions). 4 12 34

Use of themes in practical thematic analysis

Constructing meaningful themes

After coding all the data, each coder should independently reflect on the team’s summary memos (step 1), the codebook (step 2), and the coded data itself to develop draft themes (step 3). It can be illuminating for coders to review all excerpts associated with each code, so that they derive themes directly from the data. Researchers should remain focused on the research question during this step, so that themes have a clear relation with the overall project aim. Use of qualitative analysis software will make it easy to view each segment of data tagged with each code. Themes might neatly correspond to groups of codes. Or—more likely—they will unite codes and data in unexpected ways. A whiteboard or presentation slides might be helpful to organise, craft, and revise themes. We also provide a template for coproducing themes (supplemental material 3). As with codebook justification, team members will ideally produce individual drafts of the themes that they have identified in the data. They can then discuss these with the group and reach alignment or consensus on the final themes.