Your Article Library

Essay on realism.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Read this essay to learn about Realism. After reading this Essay you will learn about: 1. Introduction to Realism 2. Fundamental Philosophical Ideas of Realism 3. Forms 4. Realism in Education 5. Curriculum 6. Evaluation

- Essay on the Evaluation

Essay # 1. Introduction to Realism:

Emerged as a strong movement against extreme idealistic view of the world around.

Realism changed the contour of education in a systematic way. It viewed external world as a real world; not a world of fantasy.

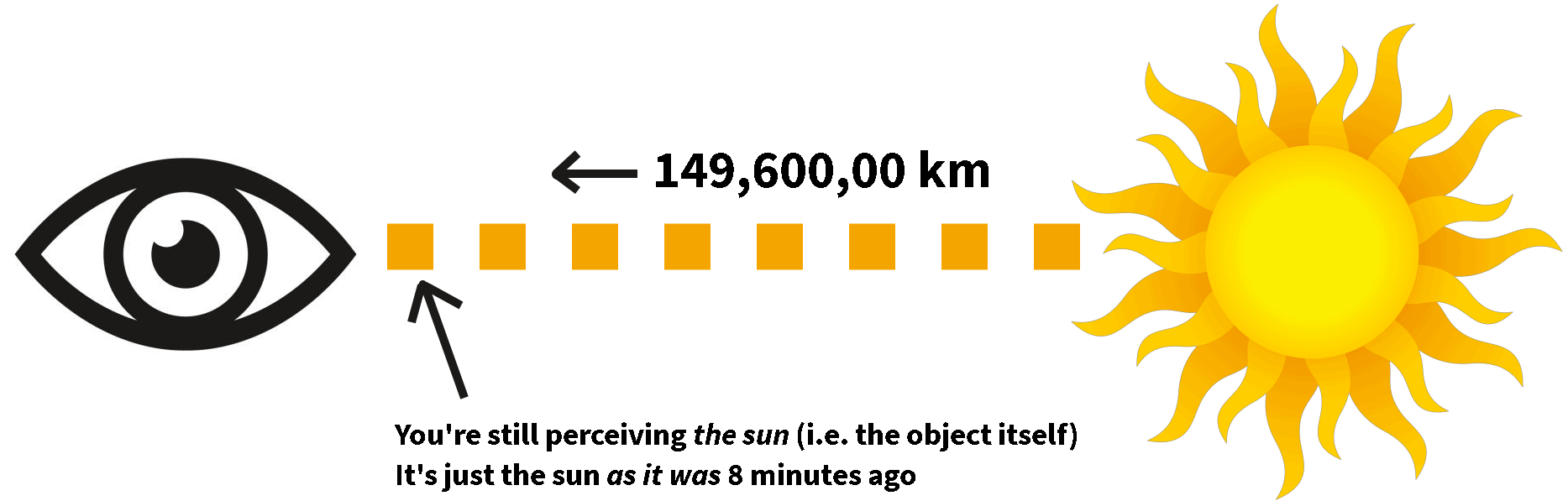

It is not based upon perception of the individuals but is an objective reality based on reason and science.

The Realist trend in philosophical spectrum can be traced back to Aristotle who was interested in particular facts of life as against Plato who was interested in abstractions and generalities. Therefore, Aristotle is rightly called as the father of Realism. Saint Thomas Aquinas and Comenius infused realistic spirit in religion.

John Locke, Immanuel Kant, John Freiderich Herbart and William James affirmed that external world is a real world. In the 20th century, two sections of realist surfaced the area of philosophy. Six American professors led by Barton Perry and Montague are neo-realists. Another section spearheaded by Arthur Lovejoy, Johns Hopkins and George Santayana emerged are called as critical realists.

Essay # 2. Fundamental Philosophical Ideas of Realism :

(i) phenomenal world is true:.

Realists believe in the external world which is true as against the idealist world-a world d this life. It is a world of objects and not ideas. It is a pluralistic world. Ross has commented, “Realism simply affirms the existence of an external world and is therefore the antithesis of subjective idealism.”

There is an order and design of the external world in which man is a part and the world idealism by the laws of cause and effect relationships. As such there is no freedom of the will for man.

(ii) Opposes to Idealist Values :

In realism, there is no berth for imagination and speculation. Entities of God, soul and other world are nothing; they are mere figments of human imagination. Only objective world is real world which a man can know with the help of his mind. Realism does not believe in ideal values, would discover values in his immediate social life. The external world would provide the work for the discovery and realization of values.

(iii) Theory of Organism :

Realists believe that an organism is formed by conscious and unconscious things. Mind is regarded as the function of organism. Whitehead, a Neo-realist remarks “ The universe is a vibrating organism in the process of evolution. Change is the fundamental feature of this vibrating universe. The very essence of real actuality is process. Mind must be regarded as the function of the organism.”

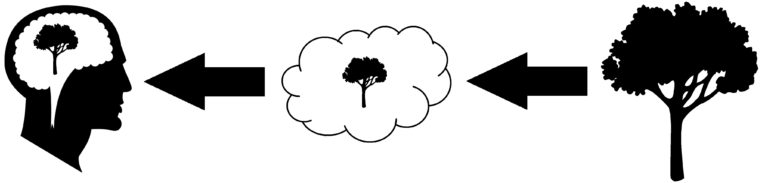

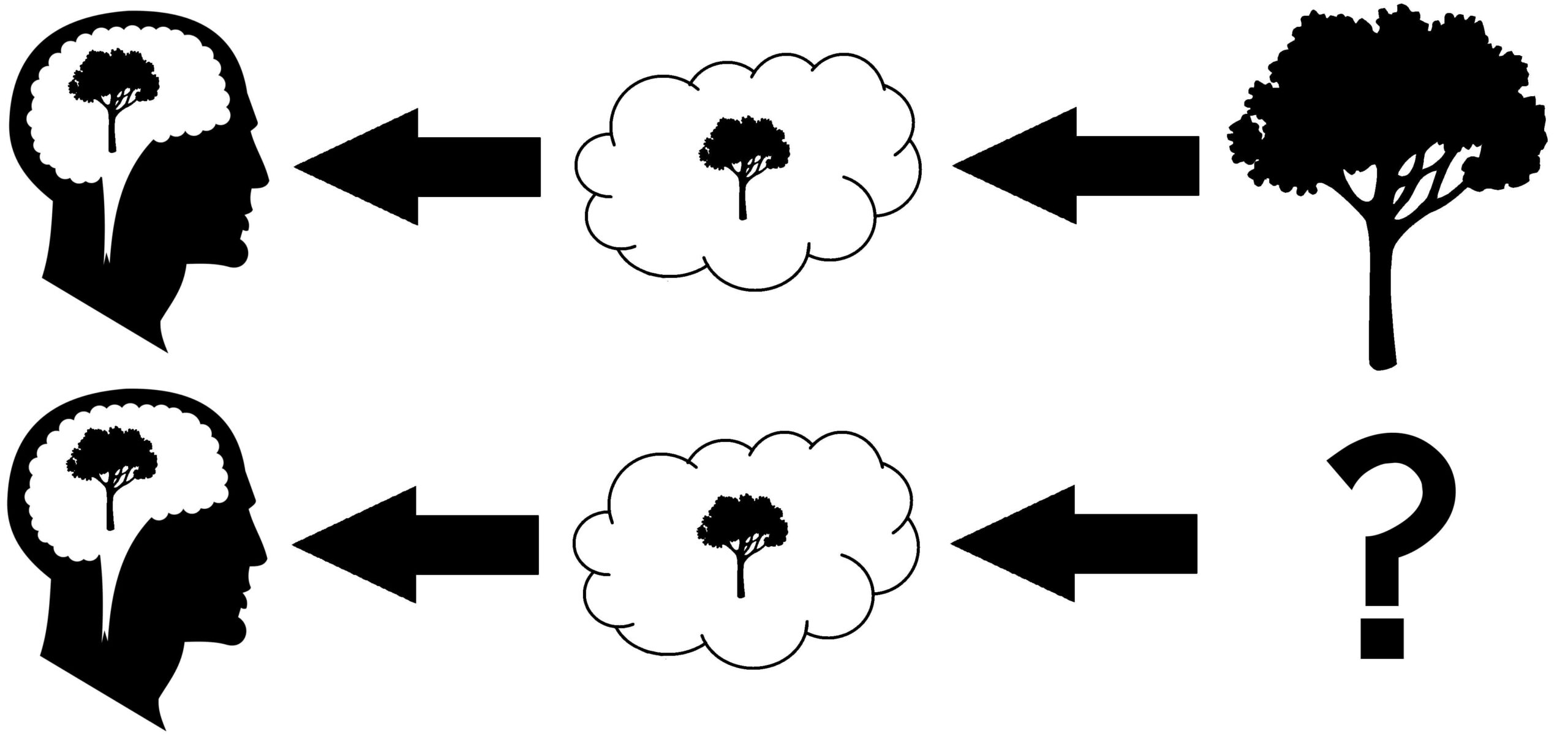

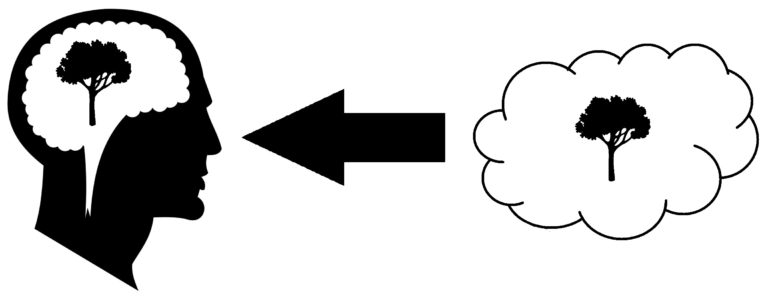

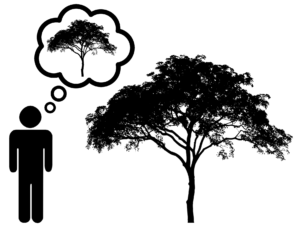

(iv) Theory of Knowledge :

According to realists, the world around us is a reality; the real knowledge is the knowledge of the surrounding world. Senses are the gateways of knowledge of the external world. The impressions and sensations as a result of our communication with external world through our sense organs result in knowledge which is real.

The best method to acquire the knowledge of the external world is the experiment or the scientific method. One has to define the problem, observe all the facts and phenomena pertaining to the problem, formulate a hypothesis, test and verify it and accept the verified solution. Alfred North, Whitehead, and Bertrand Russel have stressed on the use of this scientific method.

(v) Stress on Present Applied Life :

According to realists, spiritual world is not real and cannot be realized. They believed in the present world-physical or material which can be realized. Man is a part and parcel of this material world. They put premium upon the molding and directing of human behaviour as conditioned by the physical and material facts of the present life, for this can promote happiness and welfare.

Therefore, metaphysics according to realism is that the external world is a reality-it is a world of objects and not ideas. Epistemology deals with the knowledge-knowledge of this external world through the senses and scientific method and enquiry. Axiology in it is that realists reject idealistic values, favour discovering values in the immediate social life.

Essay # 3. Forms of Realism :

There are four forms of realism, viz., humanistic realism, social realism, sense realism and neo-realism.

(i) Humanistic Realism :

The advocates of this form of realism are Irasmus, Rebelias and Milton. The supporters of the realism firmly believed that education should be realistic which can promote human welfare and success. They favoured the study of Greek & Roman literature for individual, social and spiritual development.

Irasmus (1446-1536) castigated narrow educational system and in its place. favoured broad and liberal education. Rebelias (1483-1553) also advocated liberal education, opposed theoretical knowledge and said that education should be such as to prepare the individual to face all the problems of life with courage and solve them successfully.

He suggested scientific and psychological methods and techniques. Milton (1608-1674) also stressed liberal and complete education. He, in this connection, writes, “I call therefore a complete and generous education that which fits a man to perform justly, skillfully and magnanimously all the offices both private and public of peace and war.”

He opposed mere academic education and insisted that education should give knowledge of things and objects. He prescribed language, literature and moral education is main subjects of study; and physiology, agriculture and sculpture as subsidiary subjects of study for children.

(ii) Social Realism :

Social realists opposed academic and bookish knowledge and advocated that education should promote working efficiency of men and women in the society. Education aims at making human life happier and successful. They suggested that curriculum should include History, Geography. Law, Diplomacy, Warfare, Arithmetic’s, Dancing, Gymnastics etc. for the development of social qualities.

Further, with a view to making education practical and useful, the realists stressed upon Travelling, Tour, observation and direct experience. Lord Montaigne (1533-1552) condemned cramming and favored learning by experience through tours and travels. He opposed knowledge for the sake of knowledge and strongly advocated practical and useful knowledge.

John Locke (1635-1704) advocated education through the mother tongue and lively method of teaching which stimulates motivation and interest in the children. As an individualist, he believed that the mind of a child is a clean slate on which only experiences write. He prescribed those subjects which are individually and socially useful in the curriculum.

(iii) Sense Realism :

Developed in the Seventeenth century sense realism upholds the truth that real knowledge comes through our senses. Further, sense realists believed all forms of knowledge spring from the external world. They viewed that education should provide plethora of opportunities to the children to observe and study natural phenomena and come in contact with external objects through the senses.

Therefore, true knowledge is gained by the child about natural objects, natural phenomena and laws through the exercises of senses. They favoured observation, scientific subjects, inductive method and useful education. Mulcaster (1530—1611) advocated physical and mental development aims of education.

Reacted against any forced impressions upon the mind of the child, he upheld use of psychological methods of teaching for the promotion of mental faculties-intelligence, memory and judgement.

Francis Bacon (1562-1623) writes, “The object of all knowledge is to give man power over nature.” He, thus, advocated inductive method of teaching-the child is free to observe and experiment by means of his senses and limbs. He emphasised science and observation of nature as the real methods to gain knowledge.

Ratke (1571-1625) said that senses are the gateways of knowledge and advocated the following maxims:

a. One thing at a time,

b. Follow nature,

c. Repetition,

d. Importance on mother-tongue,

e. No rote learning,

f. Sensory knowledge,

g. Knowledge through experience and uniformity of all things.

Comenius (1592-1671) advocated universal education and natural method of education. He said that knowledge comes not only through the senses but through man’s intelligence and divine inspiration. He favoured continuous teaching till learning is achieved and advocated mother-tongue to precede other subjects.

(iv) Neo-Realism :

The positive contribution of neo-realism is its acceptance of the methods and results of modern development in physics. It believes that rules and procedures of science are changeable from time to time according to the conditions of prevailing circumstances.

Whitehead said that an organism is formed by the consciousness and the unconsciousness, the moveable and immovable thing. Education should give to child full-scale knowledge of an organism. Man should understand all values very clearly for getting full knowledge about organism. Bertrand Russell emphasized sensory development of the child.

He favoured analytical method and classification. He assigned no place to religion and supported physics to be included as one of the foremost subjects of study. Further, he opposed emotional strain in children as it leads to development of fatigue.

Essay # 4. Realism in Education :

Realism asserts that education is a preparation for life, for education equips the child by providing adequate training to face the crude realities of life with courage as he or she would perform various roles such as a citizen, a worker, a husband, a housewife, a member of the group, etc. As such, education concerns with problems of life of the child.

Chief Characteristics of Education :

The following are the chief characteristics of realistic education:

(i) Based on Science:

Realism emphasized scientific education. It favored the inclusion of scientific subjects in he curriculum and of natural education. Natural education is based on science which is real.

(ii) Thrust upon present Life of the Child :

The focal point of realistic education is the present life of the child. As it focuses upon the real and practical problems of the life, it aims at welfare and happiness of the child.

(iii) Emphasis on Experiment and Applied life :

It emphasizes experiments, experience and practical knowledge. Realistic education supports learning by doing and practical work for enabling the child to solve his or her immediate practical problems for leading a happy and successful life.

(iv) Opposes to Bookish Knowledge :

Realistic education strongly condemned all bookish knowledge, for it does not help the child to face the realities of life adequately. It does not enable the child to decipher the realities of external things and natural phenomena. The motto of realistic education is ”Not Words but Things.”

(v) Freedom of Child:

According to realists, child should be given full freedom to develop his self according to his innate tendencies. Further, they view that such freedom should promote self-discipline and self-control the foundation of self development.

(vi) Emphasis on Training of Senses:

Unlike idealists who impose knowledge from above, realists advocated self-learning through senses which need to be trained. Since, senses are the doors of knowledge, these needs to be adequately nurtured and trained.

(vii) Balance between Individuality and Sociability :

Realists give importance to individuality and sociability of the child equally. Bacon lucidly states that realistic education develops the individual on the one hand and tries to develop social trails on the other through the development of social consciousness and sense of service of the individual.

Aims of Education :

The following aims of education are articulated by the realists:

(i) Preparation for the Good life:

The chief aim of realistic education is to prepare the child to lead a happy and good life. Education enables the child to solve his problems of life adequately and successfully. Leading ‘good life’ takes four important things-self-preservation, self-determination, self-realization and self-integration.

(ii) Preparation for a Real Life of the Material World:

Realists believe that the external material world is the real world which one must know through the senses. The aim of education is to prepare a child for real life of material world.

(iii) Development of Physical and Mental Powers:

According to realists, another important aim of education is to enable the child to solve different life problems by using the faculty of mind: intelligence, discrimination and judgement.

(iv) Development of Senses:

Realists thought that development of senses is the sine-qua-non for realization of the material world. Therefore, the aim of education is to help the development of senses fully by providing varied experiences.

(v) Acquainting with External Nature and Social Environment:

It is an another aim of realistic education to help the child to know the nature and social environment for leading a successful life.

(vi) Imparting Vocational Knowledge and Skill :

According to realists, another important aim of education is to provide vocational knowledge, information, skill etc., to make the child vocationally efficient for meeting the problems of livelihood.

(vii) Development of Character :

Realistic education aims at development of character for leading a successful and balanced life.

(viii) Enabling the Child to Adjust with the Environment :

According to realists, education should aim at enabling the child to adapt adequately to the surroundings.

Essay # 5. Curriculum of Realism :

Realists wanted to include those subjects and activities which would prepare the children for actual day to day living. As such, they thought it proper to give primary place to nature, science and vocational subjects whereas secondary place to Arts, literature, biography, philosophy, psychology and morality.

Besides, they have laid stress upon teaching of mother- tongue as the foundation of all development. It is necessary for reading, writing and social interaction but not for literary purposes.

(i) Methods of Teaching :

Realists favoured principles of observation and experience as imparting knowledge of objects and external world can be given properly through the technique of observation and experience. Further, they encouraged use of audio-visual aids in education as they would develop sensory powers in the children.

Children would have “feel” of reality through them. Realists also encouraged the use of lectures, discussions and symposia. Socratic and inductive methods were also advocated. Memorization at early stage was also recommended.

Besides, learning by travelling was also suggested. The maxims of teaching are to proceed from easy to difficult, simple to complex, known to unknown, definite to indefinite, concrete to abstract and particular to general. In addition, realists give importance on the principle of correlation as they consider all knowledge as one unit.

(ii) Discipline :

Realists decry expressionistic discipline and advocate self-discipline to make good adjustment in the external environment. They, further, assert that virtues can be inculcated for withstanding realities of physical world. Children need to be disciplined to become a part of the world around in and to understand reality.

(iii) Teacher :

Under the realistic school, the teacher must be a scholar and his duty is to guide the children towards the hard core realities of life. He must expose them to the problems of life and the world around. The teacher should have full knowledge of the content and needs of the children.

He should present the content in a lucid and intelligible way by employing scientific and psychological methods is also the duty of the teacher to tell children about scientific discoveries, researches and inventions id he should inspire them to undertake close observation and experimentation for finding out new facts and principles.

Moreover, he himself should engage in research activities. Teachers, in order to be good and effective, should get training before making a foray into the field of teaching profession.

(iv) School :

Some realists’ view that school is essential as it looks like a mirror of society reflecting its real picture of state of affairs. It is the school which provides for the fullest development of the child in accordance with his needs and aspirations and it prepares the child for livelihood. According to Comenius, “The school should be like the lap of mother full of affection, love and sympathy. Schools are true foregoing places of men.”

Essay # 6. Evaluation of Realism :

Proper evaluation of realism can be made possible by throwing a light on its merits and demerits.

(i) Realism is a practical philosophy preaching one to come to term with reality. Education which is non-realistic cannot be useful to the humanity. Now, useless education has come to be considered as waste of time, energy and resources.

(ii) Scientific subjects have come to stay in our present curriculum due to the impact of realistic education.

(iii) In the domain of methods of teaching the impact of realistic education is ostensible. In modern education, inductive, heuristic, objective, experimentation and correlation methods have been fully acknowledged all over the globe.

(iv) In the area of discipline, realism is worth its name as it favours impressionistic and self-discipline which have been given emphasis in modern educational theory and practice in a number of countries in the globe.

(v) Realistic philosophy has changed the organisational climate of schools. Now, schools have been the centres of joyful activities, practical engagements and interesting experiments. Modern school is a vibrant school.

(i) Realism puts emphasis on facts and realities of life. It neglects ideals and values of life. Critics argue that denial of ideals and values often foments helplessness and pessimism which mar the growth and development of the individuals. This is really lop-sided philosophy.

(ii) Realism emphasizes scientific subjects at the cost of arts and literature. This affair also creates a state of imbalance in the curriculum. It hijacks ‘humanities’ as critics’ label.

(iii) Realism regards senses as the gateways of knowledge. But the question comes to us, how does illusion occur and how do we get faulty knowledge? It does not provide satisfactory answer.

(iv) Realism accepts the real needs and feelings of individual. It does not believe in imagination, emotion and sentiment which are parts and parcel of individual life.

(v) Although realism stresses upon physical world, it fails to provide answers to the following questions pertaining to physical world.

(i) Is the physical world absolute ?

(ii) Is there any limits of physical world ?

(iii) Is the physical world supreme or powerful?

(vi) Realism is often criticized for its undue emphasis on knowledge and it neglects the child. As the modern trend in education is paedocentric, realism is said to have put the clock behind the times by placing its supreme priority on knowledge.

In-spite of the criticisms, realism as a real philosophy stands to the tune of time and it permeates all aspects of education. It is recognized as one of the best philosophies which need to be browsed cautiously. It has its influence in modern educational theory and practice.

Related Articles:

- Influence of Sense-Realism on Education | J. A. Comenius

- Importance of Realism in Geography

Comments are closed.

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Home ›

- Reviews ›

Truth, Meaning and Realism: Essays in the Philosophy of Thought

A. C. Grayling, Truth, Meaning and Realism: Essays in the Philosophy of Thought , Continuum, 2007, 173pp., $19.95 (pbk), ISBN 9781847061546.

Reviewed by Alexander Miller, University of Birmingham

This volume is a collection of revised versions of ten essays apparently written in the 1980s or thereabouts, mainly as invited contributions to conferences. As Grayling admits in his preface, "All the papers are of their time". British philosophy in the 1970s and 1980s was dominated by an approach to the debate between realism and antirealism that was associated with Oxford and championed by Michael Dummett, and according to which the key issue was whether the theory of meaning should take as its central concept the notion of truth or the notion of assertibility , with realism favouring the former and antirealism favouring the latter. Much of the book concerns the realism debate conceived in these terms, and although there are also extended discussions of Putnam's twin-earth examples these are mainly in the context of an exchange with David Wiggins. Grayling's essays are thus also very much "of their place" (Oxford) as well as of their time (1980s).

Although in his early works Dummett had defended the idea that assertibility, and not truth, should be the central concept of the theory of meaning, in later work he -- and Crispin Wright -- suggested that antirealism could after all take the notion of truth to be the central notion of the theory of meaning so long as it was an epistemically constrained notion. Given this way of formulating antirealism there is no need to argue that the notion of assertion can be explained in terms that don't presuppose the notion of truth: even the antirealist can admit that it is a platitude that "to assert is to present as true".

In Essay 1, Grayling puts forward a view of assertion that contrasts with the approach of Wright and the later Dummett. Whereas the Wright-later Dummett view sees the aim of assertion as "the presentation of or laying claim to truth" (p.10), Grayling sees it as "the realisation of certain cognitive and practical goals" (ibid.).

Essay 2 proposes a recasting of the debate between realism and antirealism. Grayling suggests that (a) properly understood realism is not a metaphysical but an epistemological thesis: "that the domains or entities to which ontological commitment is made exist independently of knowledge of them" (p.26); and that (b) it is in fact a second-order debate about whether the realistic commitments of ordinary, first-order discourse are literally true or not, and as such has no implications for "logic, linguistic practice, or mundane metaphysics" (p.30). Grayling returns to these issues in Essays 8 and 9.

An alternative to deflationary and indefinabilist conceptions of truth is offered in Essay 3: "The predicate 'is true' is a lazy predicate. It holds a place for more precise predicates, denoting evaluatory properties appropriate to the discourse in which possession of those properties is valued" (p.32). On this view "there are, literally, different kinds of truth, individuated by subject-matter" (p.36). Grayling backs this up in Essay 4 (which, like Essay 3, is a reworked chapter from Grayling's An Introduction to Philosophical Logic , first published in 1982) with a critique of the indefinabilist position Davidson recommends in "The Folly of Trying to Define Truth". This essay also argues that Davidson's "The Coherence Theory of Truth and Knowledge" fails to yield a satisfying account of objectivity: in particular "the principle of charity is questionable beyond its heuristic applications" (p.49).

Putnam's famous "twin-earth" argument appears to some to establish that it is essential to Jones's thinking the thought that someone is drinking water in the next room that there is (or has been) some H 2 0 in Jones's environment. In Essay 5 Grayling considers Wiggins's attempt to fuse this construal of Putnam's insight -- "the extension-involvingness of natural kind terms" (p.62) -- with a Fregean theory distinguishing between the sense and reference of such a term. For Wiggins,

Taking the sense of a name as its mode of presentation of an object means that we have two things … : an object that the name presents, and a way in which it is presented. This latter [is] the 'conception' of the object … 'a body of information' -- typically open-ended and imperfect, and hence rarely if ever condensable into a complete description of the object -- in which the object itself plays a role (p.62),

and something similar holds for natural kind terms: "the sense of a natural kind term is correlative to a recognitional conception that is unspecifiable except as the conception of things like this, that and the other specimens exemplifying the concept that this conception is a conception of" (p.65). Grayling suggests that instead of taking senses to be "correlative" to "conceptions" we should instead identify senses with conceptions: "a term's sense is: an open-ended extensible body of information, possession of which enables speakers to identify the term's reference" (p.69). However, this modified account has consequences for the notion of extension-involving sense:

on the minimum specification given for the grasp of the sense of a concept-word, any concept word which applies to nothing retains its sense because what is known by one who understands it is what would count as an exemplary instance of its application if ever one were offered. (p.74)

In consequence, Wiggins was wrong to take it "that the extension-involvingness constraint ensured the realism of the reality-involvingness he took this to entail" (p.75). Related matters are pursued in Essay 6. Grayling rejects Frege's "strong objectivism" about sense, and argues that since the publicity of sense "is essentially a matter of speakers' mutual constrainings of use", it is best construed in terms of "intersubjective agreement in use" (p.85). This has implications for the externalist arguments of Putnam and Burge. Although it is true that meanings are not in the head of any single speaker, "they are in our heads, collectively understood … meaning is the artefact of intersubjectively constituted conventions governing the use of sounds and marks to communicate, and therefore resides in the language itself" (p.89). This shows -- contra Putnam -- that "facts about the physical environment of language-use are not essential to meaning" (p.89). Grayling reaches this conclusion by reflecting on what he calls an "Explicit Speaker", an idealised speaker who knows everything contained in "some best and latest dictionary [which] pooled a community's knowledge of meanings" (p.87). It follows that

when he [an individual speaker with the linguistic community's best joint knowledge at his disposal] says 'water' he intends to refer to water, that is, H 2 0, or if he lives on twin-earth, then to water on twin-earth, that is, XYZ; and so in either case his grasp of the expression's meaning determines its extension, and the psychological state in which his grasp of the meaning consists is broad. But this is not because it is related, causally or in some other way, to water, but rather to theories of water, because he is speaking in conformity with the best dictionary, that is, with the fullest available knowledge of meaning, in accord with the best current theories held by the linguistic community. (p.88)

Grayling does not consider the obvious reply that a defender of Putnam might give: that a 10 th century English peasant's application of "water" to a sample of XYZ is incorrect, and clearly not because of anything to do with the best current theory held by his linguistic community. Moreover, it appears to beg the question against Putnam to assume that, in the late-20 th century scenario that Grayling is concerned with, facts about the physical environment are not essential to grasp the meanings of some of the expressions that appear in "the best current theories held by the linguistic community".

The "Explicit Speaker" reappears in Essay 7. As Grayling advertises in the preface, this chapter suggests that " point is the driving force in interpretation of implicatures by competent speakers of a natural language" (p.vi), and that "this simple insight reveals certain puzzles to be artefacts of inexplictness" (ibid.). According to Grayling:

An Explicit Speaker of his language is one who so uses it whenever he makes an assertion (and mutatis mutandis for other kinds of utterance) he: (1) expresses his intended meaning as fully as, if not more fully than, his audience needs in the circumstances; (2) expresses his intended meaning as exactly as, if not more exactly than, his audience, etc; and (3) is as epistemically cautious as the circumstances do or might require, if not more so, with respect to the claims made or presupposed by what he says. (p.93)

Grayling proposes to deploy this notion of an Explicit Speaker to shed light on the analogues in natural language of the logical constants, presupposition-failure in uses of the likes of "Jones omitted to turn out the light", the distinction between referential and attributive uses of definite descriptions, and Putnam's use of twin-earth type examples. This chapter is difficult to follow. Although it is titled "Explicit Speaker Theory", and although the expression "Explicit Speaker Theory" is mentioned throughout, Grayling never gives a clear and explicit statement of what the theory actually is. The reader is left to work this out from inexplicit hints. We are told, for example, that according to Explicit Speaker Theory "the crux in meaning is the point, which is to be explained in terms of speakers' intentions to mean something on an occasion" (p.92), that "conventional meaning is to be characterised as the dry residue of speakers' meanings, agreed in the language community under constraints of publicity and stability" (ibid.), that "the meanings of expressions in a language are the agreed dry residue of speakers' meanings" (p.105), and that "what the Explicit Speaker does [when he says "the man whom I take to be drinking champagne is happy tonight"] is what all speakers are enthymematically doing anyway" (p.102). (Grayling does not attempt to explain what it is to do something enthymematically: again, the reader is left to work this out for himself.) In the light of this, readers with less sunny temperaments than the present reviewer are likely to be irritated by comments like "One should surely recognise all this as obvious" (p.100).

That Essay 8 is very much of its time and place is evident from its characterisation as "current orthodoxy" of the view that the realism/antirealism dispute is a debate about whether linguistic understanding is a matter of grasp of epistemically unconstrained truth-conditions or a matter of grasp of assertion conditions. For "current orthodoxy" read "orthodoxy in Oxford in the 1980s", and -- accordingly -- the essay is largely taken up with a discussion of Dummett's analysis of realism as the view that grasp of sentence-meaning is grasp of potentially evidence-transcendent truth-conditions. Grayling argues that rather than attempting in this way to bring all realist/antirealist controversies under one label, we should instead "recognise that they are controversies of different kinds" (p.126). This point is now well-taken -- and indeed defended -- even by philosophers out of the Dummettian stable (cf. Crispin Wright, Truth and Objectivity (Harvard University Press 1992)). However, in contrast to Wright, Grayling argues not that we can develop different realism-relevant considerations that can be brought to bear in different combinations as we move across different discourses, but rather that "we do well to restrict talk of realism to the case where controversy concerns unmetaphorical claims about the knowledge-independent existence of entities or realms of entities -- namely, the 'external world' case" (p.126).

Grayling's argument for this surprising claim is unconvincing. Dummett argues that realism is most fundamentally a semantic thesis, "a doctrine about the sort of thing that makes our statements true when they are true" (quoted by Grayling on p.120), since in some cases a straightforwardly ontological characterisation in terms of the existence of entities is not possible because there are no entities for the realist and antirealist to debate about (Dummett mentions realism about the future and realism about ethics as examples). Grayling argues against this that the semantic thesis is actually less fundamental than realism characterised in metaphysical and epistemological terms on the grounds that Dummett "goes on to unpack the expression 'sort of thing' in a way which shows that its being a semantic thesis comes courtesy of something else" (p.120). To display this Grayling quotes the following passage from Dummett:

the fundamental thesis of realism, so regarded, is that we really do succeed in referring to external objects, existing independently of our knowledge of them, and that the statements we make about them are rendered true or false by an objective reality the constitution of which is, again, independent of our knowledge. (Note that this is not, as Grayling refers to it, on p.55 of Dummett's 1982 "Realism" article, but actually on p.104.)

Grayling takes the reference to external objects in this latter characterisation to show that the semantic characterisation of realism presupposes the ontological characterisation rather than, as Dummett has it, vice versa. It then follows from this that "what we should say about those 'realisms' which are not readily classifiable in terms of entities is, simply, and on Dummett's own reasoning, that they are not realisms" (p.125), and it is this that leads in part to Grayling's restriction of talk of realism to the 'external world' case.

But this is an uncharitable interpretation of Dummett. I take it that what Dummett is saying in the passage quoted by Grayling is actually along the following lines: "the fundamental thesis of realism, so regarded, is that in cases where there is a relevant class of entities whose existence can be a matter of debate , the statements we make about them are rendered true or false by an objective reality the constitution of which is independent of our knowledge, so that in this sense we really do succeed in referring to external objects, existing independently of our knowledge of them; and that in cases where there is no relevant class of entities whose existence can be a matter of debate , the canonical statements of the discourse concerned are rendered true or false by an objective reality the constitution of which is independent of our knowledge". Read in this more charitable way it is clear that the class of entities mentioned is secondary to the mention of knowledge-independent truth, and so there is no implication that talk of realism should be restricted to the "external world" case, so that the way is left open for a Wright-style broadening of the realist/antirealist canvass.

Essay 9 is an extended discussion of McGinn, Nagel and McFetridge on the realism debate, while the final Essay 10 offers some brief reflections on evidence and judgement.

It is not straightforward to appraise this collection, as it is not clear what its target audience is. The various debates have moved on quite a way since Grayling's conference papers were written, and I can't help feeling that they should have been updated and submitted to the rigours of peer-review in the journals before being issued in a collection. To be fair to Grayling, though, he does attempt to pre-empt this kind of worry in his preface, where he points to the "exploratory character" of the essays and says that he "in no case take[s] them to be remotely near a final word on the debates they relate to" (p.v). But I'm not sure that this is enough to get Grayling off the hook. My main problem with the book is not that it is exploratory (there's nothing wrong with that), or that its approach is parochial and somewhat dated, but that the writing style displays some of the worst vices of philosophical writing a la 1980s Oxford, where writing clearly and succinctly appears to be regarded as a mark of superficiality, and where as you get nearer to the nub of an argument, the cruder the stylistic barbarities become. The following example -- of a single sentence! -- from Essay 5 is, unfortunately, not atypical:

Generalising from natural kind terms, we might wish to say that concept words which, in Frege's terminology, refer to empty concepts, can nevertheless be understood, because we can be (so to say) lexically exposed to -- it is more accurate to say: given an understanding of what it would be for something to fall into -- the extensions they would, in better or fuller worlds, have. (p.74)

I'm here reminded of Schopenhauer's comment that "when parentheses are inserted into sentences that have been broken up to accommodate them" the result is "unnecessary and wanton confusion" ( Essays and Aphorisms , trans. R.J. Hollingdale (Penguin 1970), p.207). At any rate, the cause of serious philosophy is not furthered by the poor attempt at Henry James impersonation. Grayling writes:

Too many gifted colleagues publish too little for fear of having every nut and bolt tightened into place; those who venture ideas as if they were letters to friends, trying out a way of thinking about something, and knowing that they will learn from the mistakes they make, do more both for the conversation and themselves thereby. (p.v)

Far be it from me to dictate Grayling's epistolary habits, but if his style in this book is typical of the way he writes to his friends, I'll give his collected correspondence a miss.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Realism and Anti-Realism

Introduction.

- Mind-Independence

- Realism and the Idea of a Ready-Made World

- Examples of Ontologically Realist Views

- Arguments for Ontological Realism

- Ontological Realism and Skepticism

- Varieties of Ontological Anti-realism

- Varieties of Epistemological Realism

- Sources of Unknowability

- Epistemological Realism and Truth

- Arguments for Recognition-Transcendence

- Arguments for Epistemological Anti-realism

- Epistemological Realism and Bivalence

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Metametaphysics

- Nonexistent Objects

- Philosophy of Language

- Richard Rorty

- Scientific Representation

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Alfred North Whitehead

- Feminist Aesthetics

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Realism and Anti-Realism by Sven Rosenkranz LAST REVIEWED: 19 March 2013 LAST MODIFIED: 19 March 2013 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195396577-0098

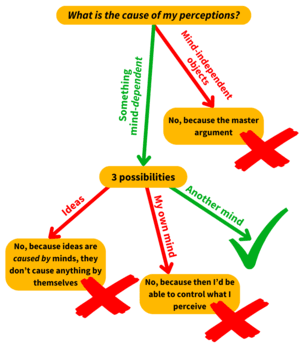

The realism/anti-realism divide has its proper place in metaphysics, but it also has important implications for epistemology and for the philosophy of thought and language. Anti-realism is defined in opposition to realism, and so it is natural to ask first what realism is and to arrive at a characterization of anti-realism on this basis. Sometimes, however, the positions put forward as competitors to realism provide us with clues as to what realism involves. Realism is not a monolithic doctrine. For one thing, one may be a realist about this but not about that. So there are differences in scope, even if not all scope restrictions allow for sensible combinations of realist and anti-realist views. For instance, realism about chemistry does not sit well with anti-realism about physics. Besides differences in scope, there are also differences in kind. Thus we must distinguish between realism as an ontological thesis and realism as an epistemological thesis. The former is concerned with what there is and how it is and argues that there are certain things that exist mind-independently. The latter is concerned with how far our epistemic powers reach and argues that there may be parts of reality in principle beyond our ken. Note that the latter thesis does not merely say something about our epistemic powers. Like the former, it also says something about reality itself, and so is just as much a metaphysical claim as the former. The need to distinguish between these kinds of realism does not imply that there are no connections between them. On the contrary, under suitable interpretations of mind-independence there may be facts about mind-independent things that are in principle beyond our reach because of the mind-independence of those things.

Realism as an Ontological Thesis

Realism as an ontological thesis always concerns things, particular or universal, of a given category (where “things” is construed broadly so as to subsume states of affairs). It contends that there are things of that category, but that things of that category exist mind-independently. Thus ontological realism combines a claim of existence with a claim of mind-independence ( Devitt 1997 , Brock and Mares 2007 ). To say that things of category C exist mind-independently is systematically ambiguous: one may read it to mean that the things that belong to C exist mind-independently; alternatively, one may read it to mean that whether a thing belongs to C is a mind-independent matter. The same distinction can be applied to the individual kinds into which things of the relevant category C might be classified: natural caves may serve as places of worship, but while, plausibly, natural caves exist mind-independently, nothing would be a place of worship without there being any minds who take it to be such. Similarly, a particular piece of brass may not exist mind-independently insofar as it was manufactured by humans with a specific purpose in mind, and yet, plausibly, its being a piece of brass is not in turn a mind-dependent matter. Even if artifacts may not be the best examples of mind-dependent existents in the intended sense, the first example is already sufficient to show the need to distinguish between two types of claims: that certain portions of reality are not in any relevant sense of our making, and that certain partitions of reality, or groupings into kinds, are not of our making in any such sense. Typically, ontological realists commit themselves to both types of claims, which is why their position naturally generalizes so as to cover the subject matter of statements about a given area or the facts , if any, these statements are apt to state, and not just the referents of the singular terms these statements contain.

Brock, Stuart, and Edwin Mares. Realism and Anti-realism . Durham, UK: Acumen, 2007.

This is one of the many helpful introductions to the realism/anti-realism debate. The authors discuss various ontologically realist views and their anti-realist competitors, concerning, for example, colors, morals, modality, and the unobservable entities posited by science, mathematics.

Devitt, Michael. Realism and Truth . 2nd ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Devitt explicates and defends the central tenets of realism as an ontological thesis and gives an account of mind-independence. Devitt furthermore argues that, quite generally, realism has nothing to do with epistemological matters, thereby denying that there is any genuinely realist position that answers to the label “realism as an epistemological thesis,” contrary to what we have assumed.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Philosophy »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- A Priori Knowledge

- Abduction and Explanatory Reasoning

- Abstract Objects

- Addams, Jane

- Adorno, Theodor

- Aesthetic Hedonism

- Aesthetics, Analytic Approaches to

- Aesthetics, Continental

- Aesthetics, Environmental

- Aesthetics, History of

- African Philosophy, Contemporary

- Alexander, Samuel

- Analytic/Synthetic Distinction

- Anarchism, Philosophical

- Animal Rights

- Anscombe, G. E. M.

- Anthropic Principle, The

- Anti-Natalism

- Applied Ethics

- Aquinas, Thomas

- Argument Mapping

- Art and Emotion

- Art and Knowledge

- Art and Morality

- Astell, Mary

- Aurelius, Marcus

- Austin, J. L.

- Bacon, Francis

- Bayesianism

- Bergson, Henri

- Berkeley, George

- Biology, Philosophy of

- Bolzano, Bernard

- Boredom, Philosophy of

- British Idealism

- Buber, Martin

- Buddhist Philosophy

- Burge, Tyler

- Business Ethics

- Camus, Albert

- Canterbury, Anselm of

- Carnap, Rudolf

- Cavendish, Margaret

- Chemistry, Philosophy of

- Childhood, Philosophy of

- Chinese Philosophy

- Cognitive Ability

- Cognitive Phenomenology

- Cognitive Science, Philosophy of

- Coherentism

- Communitarianism

- Computational Science

- Computer Science, Philosophy of

- Computer Simulations

- Comte, Auguste

- Conceptual Role Semantics

- Conditionals

- Confirmation

- Connectionism

- Consciousness

- Constructive Empiricism

- Contemporary Hylomorphism

- Contextualism

- Contrastivism

- Cook Wilson, John

- Cosmology, Philosophy of

- Critical Theory

- Culture and Cognition

- Daoism and Philosophy

- Davidson, Donald

- de Beauvoir, Simone

- de Montaigne, Michel

- Decision Theory

- Deleuze, Gilles

- Derrida, Jacques

- Descartes, René

- Descartes, René: Sensory Representations

- Descriptions

- Dewey, John

- Dialetheism

- Disagreement, Epistemology of

- Disjunctivism

- Dispositions

- Divine Command Theory

- Doing and Allowing

- du Châtelet, Emilie

- Dummett, Michael

- Dutch Book Arguments

- Early Modern Philosophy, 1600-1750

- Eastern Orthodox Philosophical Thought

- Education, Philosophy of

- Engineering, Philosophy and Ethics of

- Environmental Philosophy

- Epistemic Basing Relation

- Epistemic Defeat

- Epistemic Injustice

- Epistemic Justification

- Epistemic Philosophy of Logic

- Epistemology

- Epistemology and Active Externalism

- Epistemology, Bayesian

- Epistemology, Feminist

- Epistemology, Internalism and Externalism in

- Epistemology, Moral

- Epistemology of Education

- Ethical Consequentialism

- Ethical Deontology

- Ethical Intuitionism

- Eugenics and Philosophy

- Events, The Philosophy of

- Evidence-Based Medicine, Philosophy of

- Evidential Support Relation In Epistemology, The

- Evolutionary Debunking Arguments in Ethics

- Evolutionary Epistemology

- Experimental Philosophy

- Explanations of Religion

- Extended Mind Thesis, The

- Externalism and Internalism in the Philosophy of Mind

- Faith, Conceptions of

- Feminist Philosophy

- Feyerabend, Paul

- Fichte, Johann Gottlieb

- Fictionalism

- Fictionalism in the Philosophy of Mathematics

- Film, Philosophy of

- Foot, Philippa

- Foreknowledge

- Forgiveness

- Formal Epistemology

- Foucault, Michel

- Frege, Gottlob

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg

- Geometry, Epistemology of

- God and Possible Worlds

- God, Arguments for the Existence of

- God, The Existence and Attributes of

- Grice, Paul

- Habermas, Jürgen

- Hart, H. L. A.

- Heaven and Hell

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich: Aesthetics

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich: Metaphysics

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich: Philosophy of History

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich: Philosophy of Politics

- Heidegger, Martin: Early Works

- Hermeneutics

- Higher Education, Philosophy of

- History, Philosophy of

- Hobbes, Thomas

- Horkheimer, Max

- Human Rights

- Hume, David: Aesthetics

- Hume, David: Moral and Political Philosophy

- Husserl, Edmund

- Idealizations in Science

- Identity in Physics

- Imagination

- Imagination and Belief

- Immanuel Kant: Political and Legal Philosophy

- Impossible Worlds

- Incommensurability in Science

- Indian Philosophy

- Indispensability of Mathematics

- Inductive Reasoning

- Instruments in Science

- Intellectual Humility

- Intentionality, Collective

- James, William

- Japanese Philosophy

- Kant and the Laws of Nature

- Kant, Immanuel: Aesthetics and Teleology

- Kant, Immanuel: Ethics

- Kant, Immanuel: Theoretical Philosophy

- Kierkegaard, Søren

- Knowledge-first Epistemology

- Knowledge-How

- Kristeva, Julia

- Kuhn, Thomas S.

- Lacan, Jacques

- Lakatos, Imre

- Langer, Susanne

- Language of Thought

- Language, Philosophy of

- Latin American Philosophy

- Laws of Nature

- Legal Epistemology

- Legal Philosophy

- Legal Positivism

- Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm

- Levinas, Emmanuel

- Lewis, C. I.

- Literature, Philosophy of

- Locke, John

- Locke, John: Identity, Persons, and Personal Identity

- Lottery and Preface Paradoxes, The

- Machiavelli, Niccolò

- Martin Heidegger: Later Works

- Martin Heidegger: Middle Works

- Material Constitution

- Mathematical Explanation

- Mathematical Pluralism

- Mathematical Structuralism

- Mathematics, Ontology of

- Mathematics, Philosophy of

- Mathematics, Visual Thinking in

- McDowell, John

- McTaggart, John

- Meaning of Life, The

- Mechanisms in Science

- Medically Assisted Dying

- Medicine, Contemporary Philosophy of

- Medieval Logic

- Medieval Philosophy

- Mental Causation

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice

- Meta-epistemological Skepticism

- Metaepistemology

- Metaphilosophy

- Metaphysical Grounding

- Metaphysics, Contemporary

- Metaphysics, Feminist

- Midgley, Mary

- Mill, John Stuart

- Mind, Metaphysics of

- Modal Epistemology

- Models and Theories in Science

- Montesquieu

- Moore, G. E.

- Moral Contractualism

- Moral Naturalism and Nonnaturalism

- Moral Responsibility

- Multiculturalism

- Murdoch, Iris

- Music, Analytic Philosophy of

- Nationalism

- Natural Kinds

- Naturalism in the Philosophy of Mathematics

- Naïve Realism

- Neo-Confucianism

- Neuroscience, Philosophy of

- Nietzsche, Friedrich

- Normative Ethics

- Normative Foundations, Philosophy of Law:

- Normativity and Social Explanation

- Objectivity

- Occasionalism

- Ontological Dependence

- Ontology of Art

- Ordinary Objects

- Other Minds

- Panpsychism

- Particularism in Ethics

- Pascal, Blaise

- Paternalism

- Peirce, Charles Sanders

- Perception, Cognition, Action

- Perception, The Problem of

- Perfectionism

- Persistence

- Personal Identity

- Phenomenal Concepts

- Phenomenal Conservatism

- Phenomenology

- Philosophy for Children

- Photography, Analytic Philosophy of

- Physicalism

- Physicalism and Metaphysical Naturalism

- Physics, Experiments in

- Political Epistemology

- Political Obligation

- Political Philosophy

- Popper, Karl

- Pornography and Objectification, Analytic Approaches to

- Practical Knowledge

- Practical Moral Skepticism

- Practical Reason

- Probabilistic Representations of Belief

- Probability, Interpretations of

- Problem of Divine Hiddenness, The

- Problem of Evil, The

- Propositions

- Psychology, Philosophy of

- Quine, W. V. O.

- Racist Jokes

- Rationalism

- Rationality

- Rawls, John: Moral and Political Philosophy

- Realism and Anti-Realism

- Realization

- Reasons in Epistemology

- Reductionism in Biology

- Reference, Theory of

- Reid, Thomas

- Reliabilism

- Religion, Philosophy of

- Religious Belief, Epistemology of

- Religious Experience

- Religious Pluralism

- Ricoeur, Paul

- Risk, Philosophy of

- Rorty, Richard

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques

- Rule-Following

- Russell, Bertrand

- Ryle, Gilbert

- Sartre, Jean-Paul

- Schopenhauer, Arthur

- Science and Religion

- Science, Theoretical Virtues in

- Scientific Explanation

- Scientific Progress

- Scientific Realism

- Scientific Revolutions

- Scotus, Duns

- Self-Knowledge

- Sellars, Wilfrid

- Semantic Externalism

- Semantic Minimalism

- Senses, The

- Sensitivity Principle in Epistemology

- Shepherd, Mary

- Singular Thought

- Situated Cognition

- Situationism and Virtue Theory

- Skepticism, Contemporary

- Skepticism, History of

- Slurs, Pejoratives, and Hate Speech

- Smith, Adam: Moral and Political Philosophy

- Social Aspects of Scientific Knowledge

- Social Epistemology

- Social Identity

- Sounds and Auditory Perception

- Space and Time

- Speech Acts

- Spinoza, Baruch

- Stebbing, Susan

- Strawson, P. F.

- Structural Realism

- Supererogation

- Supervenience

- Tarski, Alfred

- Technology, Philosophy of

- Testimony, Epistemology of

- Theoretical Terms in Science

- Thomas Aquinas' Philosophy of Religion

- Thought Experiments

- Time and Tense

- Time Travel

- Transcendental Arguments

- Truth and the Aim of Belief

- Truthmaking

- Turing Test

- Two-Dimensional Semantics

- Understanding

- Uniqueness and Permissiveness in Epistemology

- Utilitarianism

- Value of Knowledge

- Vienna Circle

- Virtue Epistemology

- Virtue Ethics

- Virtues, Epistemic

- Virtues, Intellectual

- Voluntarism, Doxastic

- Weakness of Will

- Weil, Simone

- William of Ockham

- Williams, Bernard

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig: Early Works

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig: Later Works

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig: Middle Works

- Wollstonecraft, Mary

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.151.9]

- 185.80.151.9

An Essay for Educators: Epistemological Realism Really is Common Sense

- Published: 15 June 2007

- Volume 17 , pages 425–447, ( 2008 )

Cite this article

- William W. Cobern 1 &

- Cathleen C. Loving 2

1099 Accesses

28 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

“What is truth?” Pontius Pilot asked Jesus of Nazareth. For many educators today this question seems quaintly passé. Rejection of “truth” goes hand-in-hand with the rejection of epistemological realism. Educational thought over the last decade has instead been dominated by empiricist, anti-realist, instrumentalist epistemologies of two types: first by psychological constructivism and later by social constructivism. Social constructivism subsequently has been pressed to its logical conclusion in the form of relativistic multiculturalism. Proponents of both psychological constructivism and social constructivism value knowledge for its utility and eschew as irrelevant speculation any notion that knowledge is actually about reality. The arguments are largely grounded in the discourse of science and science education where science is “western” science; neither universal nor about what is really real. The authors defended the notion of science as universal in a previous article. The present purpose is to offer a commonsense argument in defense of critical realism as an epistemology and the epistemically distinguished position of science (rather than privileged) within a framework of epistemological pluralism. The paper begins with a brief cultural survey of events during the thirty-year period from 1960–1990 that brought many educators to break with epistemological realism and concludes with comments on the pedagogical importance of realism. Understanding the cultural milieu of the past forty years is critical to understanding why traditional philosophical attacks on social constructivist ideas have proved impotent defenders of scientific realism.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Rivers and Fireworks: Social Constructivism in Education

Comparing radical, social and psychological constructivism in Australian higher education: a psycho-philosophical perspective

Toward a new philosophical anthropology of education: fuller considerations of social constructivism.

Traditionally realism refers to ontology. However, especially in education circles, realism is taken as an epistemology. Few anti-realist in the education community are ontological anti-realists––the issue is epistemology.

Our cultural survey is of necessity very brief. First, our argument is meant as an hypothesis to stimulate further study and discussion. Second, a longer treatment would be beyond the scope of the journal. Third, our focus is limited to American culture. Other countries and societies would undoubtedly tell the story differently.

It should be noted that logical positivism , in its doctrinaire form, was never a realist position. Early positivists like Carnap and Ayer rejected the idea that science aims to describe an independent reality, not because they thought it was false, but because they saw no way to confirm or disconfirm it by experience. Later (long before the 1960s), many former positivists abandoned this position in favor of a form of realism known as logical empiricism . The two positions have significant similarities but should not be confused (Salmon 2000 ).

There were other reasons for reforming science education. See Rudolph ( 2002 ) for a thorough discussion of economic and political pressures for science education reform prominent in the early Cold War period.

For an excellent discussion of the difference between the interests of science and public interest in science, see Eger ( 1989 ).

For examples of socially relevant science curriculum ideas of the period, see Baird ( 1937 ) or Zechiel ( 1937 ).

One indication that the critics failed in their efforts is that the Kromhout and Good title reappears thirteen years later in Gross et al. ( 1996 ). Indeed, in the eyes of many in science, the situation had only worsened as indicated by the two-word addition in the Gross et al title, The Flight From Science and Reason .

See < http://www.emory.edu/EDUCATION/mfp/Kuhnsnap.html > for a brief biographical sketch of Kuhn’s life and work. See also Science & Education vol.9 nos.1–2 for discussion of Kuhn’s impact on science educators.

We are not indicating a chronological order. For the most part, these were simultaneous events during the decade.

Although our focus is the United States, Kuhn’s book had more immediate impact in Great Britain during the late 1960s founding of the University of Edinburgh’s Strong Program in the sociology of science. This school of sociology was “in direct conflict with all philosophical theories that seek to distinguish logic or rationality from psychology or sociology” (Giere 1991 , p. 51). On the Continent, while no direct influence is claimed here between Kuhn’s science writings and the European literary “deconstructionists,” it is interesting to note some similar revolutionary writings. While Kuhn was revising the first edition of his magnum opus in an attempt to deal with criticisms of his myriad uses of “paradigms” in science communities, Jacque Derrida was, at about the same time, “deconstructing” literary texts in articles with titles like Ends of Man (Derrida 1969 ), The Purveyor of Truth (Derrida ( 1975 ), or his psychoanalysis of the “truth factor” ( 1975 ).

See RachelCarson.org (“a website devoted to the life and legacy of Rachel Carson”) at: http://www.rachelcarson.org/.

The education and social science literatures often overstate Kuhn’s influence in academic philosophy. As a counterbalance, consider that in Wesley Salmon's ( 1989 ) Four Decades of Scientific Explanation , Kuhn is mentioned only once in over 200 pages of meticulous historical survey.

The notion that Copernicus was an instrumentalist is an historical myth. “All of the evidence is that Copernicus was a robust realist and that it is Osiander, not Copernicus, who bears responsibility for the instrumentalism here. When Copernicus's disciple Georg Joachim Rheticus (author of the famous “Narratio Prima”) read the unsigned preface, he was furious and said that if he had positive proof that Osiander had inserted this he would personally give him such a thrashing that Osiander would never again interfere in the affairs of scientific men! Many good scientists who read further than the preface realized that Copernicus is an earnest realist: Maestlin and his famous pupil Kepler, Thomas Digges in England, etc.” (McGrew 2002 )

We quote Vico because Glasersfeld does; however, we do not necessarily agree with Glasersfeld’s interpretation of Vico’s work. For a different perspective on Vico, see Lilla ( 1993 ).

For a discussion on types of multiculturalism, see: Haack ( 1998 , Ch. 8).

It should be apparent that epistemological realism and ontological realism go hand in hand.

The inability to have direct access to reality is a key supposition for anti-realists. For an incisive rebuttal and defense of the theory of direct perception, see Nola ( 2003 ).

Along with the sociology of science, critical realism agrees that constructing goes on in science––that science is not about discovering “already categorized objects and relations.” The difference comes, however, in that scientists can legitimately claim “genuine similarities” between logical constructs and aspects of reality. Rather than “critical,” Giere ( 1999 ) refers to “perspectival” realism to emphasize that scientific theories never capture completely the “totality of reality” but provide us with only—perspectives “…science that is perspectival rather than absolute” (Giere 1999 , p. 79). Our use of “critical realism” is in this vein. For a philosophical introduction to critical realism, see Bhaskar ( 1989 ), Harré ( 1975 ), Putman ( 1987 ) or Salmon ( 1989 ). There are different varieties of critical realism such as Giere’s ( 1999 ) “constructive realism” but what they have in common is nicely described by Polkinghorne ( 1991 , p. 304): “epistemology models ontology.”

For more on Traditional Ecological Knowledge, see Snively and Corsiglia ( 2001 ).

Adams III HH (1986) African and African-American contributions to science and technology. In the Portland African-American Baseline Essays. Portland Public Schools, Portland, OR

Adas M (1989) Machines as the measure of man: Science, technology, and ideologies of western dominance. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY

Google Scholar

Adler MJ (1974) Little errors in the beginning. The Thomist 38:27–48

Alexander D (2001) Science in search of God. Guardian Unlimited. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/Archive/Article/0,4273,4245372,00.html>

Aronowitz S (1988) Science as power: Discourse and ideology in modern society. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN

Atwater MM (1994) Research on cultural diversity in the classroom. In: Gabel DL (ed) Handbook of research on science teaching and learning. MacMillan Publishing Company, New York, pp 558–576

Atwater MM (1995) The multicultural science classroom. The Science Teacher 62(2):21–23

Baird H (1937). Teaching the physical sciences from a functional point of view. Educational Method 16: 407–412

Bhaskar R (1989) Reclaiming reality: a critical introduction to contemporary philosophy. Verso, London

Bell D (1976) The cultural contradictions of capitalism. Basic Books, New York

Boswell J (1998) Life of Johnson (abridged and edited) -project Gutenberg’s etext of life of Johnson by [James] Boswell, Release #1564. In: CG Osgood (ed) Boswell’s Life of Johnson. P. O. Box 2782, Champaign, IL 61825: Project Gutenberg. http://digital.library.upenn.edu/webbin/gutbook/lookup?num=1564

Boyd RN (1983) On the current status of scientific realism. Erkenntnis 19:45–90

Article Google Scholar

Brickhouse NW (2001) Embodying science: A feminist perspective on learning. J Res Sci Teach 38(3):282–295

Bruner JS (1960) The process of education. Vintage Books, New York

Bunge M (1996) In praise of intolerance to charlatanism in academia. In: Gross PR, Levitt N, Lewis MW (eds) The flight from science and reason. New York Academy of Sciences, New York, pp 96–115

Bush V (1945) Science, the endless frontier; A report to the President. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

Byrds (Musical group) (Composer) (1965) Greatest hits. Columbia, New York

Capra F (1977) The tao of physics: reflections on the cosmic dance. Saturday Rev 5:21–8

Carson R (1962) Silent spring. Fawcett, Greenwich, CN

Cobern WW (1997) Public understanding of science as seen by the scientific community: Do we need to re-conceptualize the challenge and to re-examine our own assumptions? In: Sjøberg S, Kallerud E (eds) Science, technology and citizenship: The public understanding of science and technology in science education and research policy. Norwegian Institute for Studies in Research and Higher Education, Oslo, Norway, pp 51–74

Cobern WW, Loving CC (2001) Defining ‘science’ in a multicultural world: Implications science education. Scie Edu 85(1):50–67

Collins H (1981) Stages in the empirical programme of relativism - introduction. Soc Stud Sci 11(1):3–10

Crouch S (1995) Melting pot blues. Am Enterp 6(2):51–55

Dawkins R (1986) The blind watchmaker: why the evidence of evolution reveals a universe without design. W.W. Norton & Company, New York

DeBoer GE (1991) A history of ideas in science education: Implications for practice. Teachers College Press, New York

Dedijer S (1962) Measuring the growth of science. Science 138(3542):781–788

Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (1994) Introduction: entering the field of qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds) Handbook of qualitative research. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp 1–17

Derrida J (1969) Ends of man. Philos Phenomenol Res 30(1):31–57

Derrida J (1975) The purveyor of truth. Yale Fr Stud 52:31–113

Derrida J (1975) The truth factor + separating the essence from the pretext in the psychoanalytic interpretation of literary texts, particularly the works of Edgar Allan Poe. Poetique 21:96–147

Donovan AL, Laudan L, Laudan R (1988) Scrutinizing science: empirical studies of scientific change. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Duschl RA (1985) Science education and the philosophy of science: Twenty-five years of mutually exclusive development. Sch Sci Math 85(7):541–555

Eflin JT, Glennan S, Reisch G (1999) The nature of science: A perspective from the philosophy of science. J Res Sci Teach 36(1):107–116

Eger M (1989) The ‘interests’ of science and the problems of education. Synthese 81(1):81–106

Elkana Y (1970/2000) Science, philosophy of science and science teaching. Sci Edu 9(5):463–485

Fox-Genovese E (1999) Ideologies and realities. Orbis 43(4):531–539. WilsonSelectPlus_FT

Friberg SR (2000) Science and Religion: Paradigm Shifts, Silent Springs, and Eastern Wisdom. World Order 31(3):49–52

Garrison JW, Bentley ML (1990) Teaching scientific method: The logic of confirmation and falsification. Sch Sci Math 90(3):188–197

Geelan DR (1997) Epistemological Anarchy and the Many Forms of Constructivism. Sci Edu 6(1–2):15–28

Gergen K (1988) Feminist critique of science and the challenge of social epistemology. In: Gergen MM (ed) Feminist thought and the structure of knowledge. New York University Press, New York, pp 27–48

Giere RN (1988) Explaining Science: A Cognitive Approach. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Giere RN (1991) Understanding scientific reasoning. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston

Giere RN (1999) Science without laws. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Glasersfeld EV (1988) Constructivism as a scientific method. Sci Reason Res Inst News Lett 3(2):8–9

Glasersfeld EV (1989) Cognition, construction of knowledge, and teaching. Synthese 80(1):121–140

Glasersfeld EV (2001) Learning as constructive activity. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the proceedings of the 5th annual meeting of the North American group of PME (1983). UMass Scientific Reasoning Research Institute, Amherst, MA

Glazer N, Moynihan DP (1979) Beyond the melting pot; the Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Jews, Italians, and Irish of New York City, 2nd edn. The M.I.T. Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Gollnick DM, Chinn PC (1986) Multicultural education in a pluralistic society. Merrill, Columbus, OH

Good RG (1991) Theoretical bases for science education research: Contextual realism in science and science education. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching. The Abbey, Fontane, WI

Gross PR, Levitt N, Lewis MW (1996) The flight from science and reason. New York Academy of Sciences, New York

Guba EG, Lincoln YS (1994) Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds) Handbook of qualitative research. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp 105–117

Haack S (1998) Manifesto of a passionate moderate. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL

Hanson NR (1958) Patterns of discovery: an inquiry into the conceptual foundations of science. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Harré R (1975) Causal powers: a theory of natural necessity. Basil Blackwell, Oxford

Hofstein A, Yager RE (1982) Societal issues as organizers for science education in the ‘80s. Sch Sci Math 82(7):539–547

Holton G (2000) The Rise of Postmodernisms and the “End of Science”. J Hist Ideas 61(2):327–341

Hurd PD (1998) Scientific literacy: New minds for a changing world. Sci Edu 82(3):407–416

Hurd PD (2000) Science education for the 21 st century. Sch Sci Math 100(6):282–238

Johnson S (1969/1752) Elementa philosophica: containing chiefly Noetica, or things relating to the mind or understanding; and Ethica, or things relating to the moral behaviour. Kraus Reprint Co, New York

Khlentzos D (2000) Semantic challenges to realism. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Kromhout R, Good R (1983) Beware of societal issues as organizers for science education. Sch Sci Math 83(8):647–650

Kuhn TS (1962/1970) The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Ladriere J (1977) The challenge presented to cultures by science and technology. UNESCO, Paris, France

Laudan L (1990) Science and relativism: some key controversies in the philosophy of science. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Lear L (1998) Rachel Louise Carson [Web Page]. URL http://www.rachelcarson.org/biography.htm [2001, July 19]

Lilla M (1993) G. B. Vico: The antimodernist. The Wilson Quarterly XVII(3):32–39

Lillegard N (2001) Meaning, language, rules, social construction under philosophy of social science (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy) [Web Page]. URL http://www.utm.edu/research/iep/s/socscien.htm#Meaning, Language, Rules, Social Construction

Loving CC (1991) The scientific theory profile: A philosophy of science models for science teachers. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 28(9): 823–838

Loving CC (1997) From the summit of truth to its slippery slopes: science education’s journey through positivist-postmodern territory. Am Edu Res J 34(3):421–452

Loving CC, Cobern WW (2000) Invoking Thomas Kuhn: What citation analysis reveals for science education. Sci Edu 9(1/2):187–206

Loving CC, Ortiz de Montellano B (2000) Classical and reform curriculum analysis: How do multicultural science curricula fare? Can culturally relevant science be taught? Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA

Luft J (1998) Multicultural science education: An overview. J Sci Teach Edu 9(2):103–122

Lyons S (2001) Health care fraud: Medical ‘quackery’ booming in America. American Health Line, pp 1–2

Mahner M, Bunge M (1996) Is religious education compatible with science education? Sci Edu 5(2):101–123

Mallinson GG (1984) Leastwise, not much. Sch Sci Math 84(1):1–6

Matthews MR (1994) Science teaching: The role of history and philosophy of science. New York, Routledge

Matthiessen P (Environmentalist: Rachel Carson [Web Page]. URL http://www.time.com/time/time100/scientist/profile/carson.html [2001, July 19]

McDowell SA, Ray BD (issue ed) (2000) Home schooling. Peabody J Edu 75(1&2)

McGuire B (Composer) (1960–1969) Eve of destruction. Beverly Hills, CA, Dunhill

McGrew T (2002) Personal communication

Nadeau R, Desautels J (1984) Epistemology and the teaching of science. Science Council of Canada, Ottawa, Canada

Nola R (1997) Constructivism in science and in science education: a philosophical critique, Science & education 6(1–2):55–83. Reproduced in M.R. Matthews (ed), Constructivism in science education: A philosophical debate, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1998

Nola R (2003) ‘Naked before reality; Skinless before the absolute’: A Critique of the inaccessibility of reality argument in constructivism. Sci Edu 12(2):131–166

O’Neil, J. (1991) On the Portland Plan: a conversation with Matthew Prophet. Educational Leadership, 24–27

Ortiz de Montellano B (1996) Afrocentric pseudoscience: The miseducation of African Americans. In: Gross PR, Levitt N, Lewis MW (eds) The flight from science and reason. The New York Academy of Sciences, NY, pp 561–572

Peirce CS (1931) Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Phillips DC, Burbules NC (2000) Postpositivism and educational research. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, MD

Polkinghorne JC (1991) God’s action in the world. Cross Currents 41(3):293–307

Powell CF (1972) The aims of science in our time. In: Burhop EHS, Lock WO, Memon MGK (eds) Collected papers of Cecil Frank Powell. American Elsevier Publishing Co, New York, NY, pp 434–446

Prather JP (1990) Tracing science teaching. National Science Teachers Association, Washington, DC

Putman H (1987) The many faces of realism. Open Court Press, LaSalle, IL

Randall JH Jr (1940) The making of the modern mind. Columbia University Press, New York

Reid T (1764/1997) An inquiry into the human mind: on the principles of common sense. University Park, PA, Pennsylvania State University Press

Reiff D (1993) Multiculturalism’s silent partner - It’s the newly globalized economy, stupid. Harper’s 287(1719):62–72

Rosenblatt B (2001 May) Say ‘Aaah’: Alternative-treatment trend raises insurance issues. Los Angeles Times, p. 2

Rostow WW (1971) The stages of economic growth: a non-communist manifesto. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Roth W-M., Roychdhury A (1994) Physics students epistemologies and views about knowing and learning. J Res Sci Teach 31(1):5–30

Rudolph JL (2002) Scientists in the classroom: the cold war reconstruction of American science education. Palgave, New York

Salmon WC (1989) Four decades of scientific explanation. In: W. Salmon, Kitcher (eds), Scientific explanation. University of Minnesota Press. Notes, Minneapolis: Call Number: Q174.8 .S26 1989

Salmon WC (2000) Logical empiricism. In: Newton-Smith WH (ed) A companion to the philosophy of science. Blackwell Publishers, Malden, MA, pp 233–242

Sankey H (2001) Scientific realism: An elaboration and a defense. PhilSci Archive. <http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/documents/disk0/00/00/03/04/index.html>