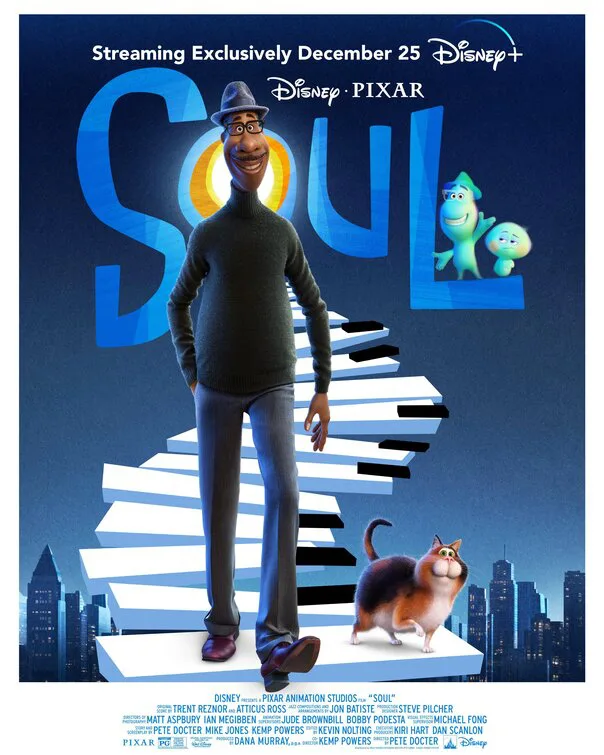

Pixar’s “Soul” is about a jazz pianist who has a near-death experience and gets stuck in the afterlife, contemplating his choices and regretting the existence that he mostly took for granted. Pixar veteran Pete Docter is the credited co-director, alongside playwright and screenwriter Kemp Powers , who wrote Regina King’s outstanding “One Night in Miami.” Despite its weighty themes, the project has a light touch. A musician might liken “Soul” to an extended riff, or a five-finger exercise, which is very much in the spirit of jazz, an improvisation-centered art that’s honorably and accurately depicted onscreen whenever Joe or another musician character starts to perform.

The prologue peaks with Joe (voiced by Jamie Foxx ) falling into an open manhole and ending up comatose in a hospital. It’s a bummer twist ending to a great day in which Joe was finally offered a staff job at his school, then nailed an audition with a visiting jazz legend named Dorothea Williams ( Angela Bassett ) who had invited him to play with her that night. After his near-lethal pratfall, Joe’s soul is sent to the Great Beyond—basically a cosmic foyer with a long walkway, where souls line up before heading toward a white light. Joe isn’t ready for The End, so he flees in the other direction, falls off the walkway, and ends up in a brightly colored yet still-purgatorial zone known as The Great Before.

The Great Before is a bit like the setting of Albert Brooks’ metaphysical comedy “ Defending Your Life .” It has its own rules and procedures, and is part of a larger spiritual ecosystem wherein certain things have to happen for other things to happen. There’s a touch of video game structure/plotting to the entire premise, and it’s reinforced by the stylized drawing of Great Before characters in supervisory positions over mentors and proto-souls: they’re two-dimensional, shape-shifting Cubist figures made of elegant neon lines.

The purpose of the Great Before is to mentor fresh souls so that they can discover a “spark” that will drive them to a happy and productive life down on earth. Joe is motivated mainly by a desire to avoid the white light and get back to earth somehow (and play that amazing gig he’d been waiting his whole life for), so he assumes the identity of an acclaimed Swedish psychologist and mentors a problem blip known only by her number, 22 ( Tina Fey ). Twenty-two is a blasé cynic who has rejected mentorship from some of the greatest figures in mortal history, including Carl Jung and Abraham Lincoln. Can Joe break the streak and help her find her purpose? Have you ever seen a Pixar film before? Of course. It’s mainly about how things happen in these films, rarely about what happens.

That having been said, there’s a nifty comic twist about halfway through the film that livens up “Soul” just when it was starting to drag, and it’s best not to spoil it here (even though trailers and ads already have). Suffice to say that 22 eventually does find her spark, although it takes a lot of effort and more than a few wild misadventures to get there; and that Joe reexamines his years on earth as a genial but meek teacher and finds them wanting. He didn’t make as many friends as he should have and was consumed by fears that he traded his childhood dream of becoming a working jazz artist for a more ordinary life. (Joe’s mother, played by Phylicia Rashad , is not supportive of his music.) The downside is that this turns “Soul” into another of a string of animated films (including “ The Princess and the Frog ” and “ Spies in Disguise “) in which a rare Black leading character is transformed into something else for the majority of a film’s running time.

Is this the first midlife crisis movie released by Pixar? Possibly, although Woody in the “ Toy Story ” films seemed to have a touch of that affliction as well. The movie is a bit shaggy and disorganized with its mythology/rules—something that Pixar is usually meticulous about, to the point of being obsessive. I’m not convinced it adds up to all much in the grand scheme by the time the final sequence arrives. The film’s message could be summed up as, “Don’t get so hung up on ambition that you forget to stop and smell the flowers.” A birthday card could’ve told you that. And some of the jokes are a tad DreamWorksy, like the bit where a lost soul returns to earth and realizes that he’s completely wasted his life by working in hedge funds; a ruthless international mega-corporation like Disney— which stuck most of its 20th Century Fox repertory holdings in a “vault” last year to push people to rent or purchase new Disney product, and that once sued day care centers for putting its characters on murals without permission—has no business lecturing anybody else about the moral emptiness of materialism.

And yet, “ Cars ” and its various derivatives aside, Pixar has never released a flat-out bad film. And this is a good one: pleasant and clever, with a generous heart, committed voice acting, and some of the kookiest images in Pixar history (including a ghostly, pink, land-bound pirate vessel belonging to a “mystic without borders,” with tie-died sails, a peace symbol anchor, and Bob Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues” blasting on a continuous loop). The company has been entrenched at the center of popular culture for decades, its reputation fortified by animated features that blend innovative design and graphics, lively physical and verbal comedy, impeccably staged action, and a sensibility that one of my old college film textbooks called “sprezzatura”—described in Baldassare Castiglione’s 1528 The Book of the Courtier as ” … a certain nonchalance, so as to conceal all art, and make whatever one does or says seem to be without effort, and almost without any thought about it.” In other words, Pixar makes it all look easy, even when hundreds of people worked on the project long enough to justify a “production babies” section of the end credits.

Despite feeling like rather minor Pixar overall, “Soul” will prove to be of historical interest because, despite the transformation issue, and when it isn’t getting wrapped up in goofy afterlife shenanigans, it’s the most unapologetically Black Pixar project yet released. Its portrayal of jazz is not only accurate in terms of its soundtrack of classic cuts and depiction of performance (the piano and trumpet playing is as correct as anything in Spike Lee’s “ Mo' Better Blues “) but also its wider cultural context.

In a flashback, Joe’s dad, who introduced him to jazz, describes the music as one of the greatest African-American contributions to world culture. There are many other touches in the film that testify to the story’s anchoring in an experience beyond the white, middle-class suburban norms that Pixar embraces by default. There’s even a visit to a Black barbershop showcasing an array of male hairstyles; a joke about the difficulty of a Black man hailing a taxi in New York City (“This would be hard even if I wasn’t wearing a hospital gown!”); and a reference to Charles Drew, a Black physician credited with pioneering the blood transfusion. This distinction gives weight to lines that might not have registered in a Pixar film with white protagonists, such as 22’s quip, “You can’t crush a soul here. That’s what life on earth is for.”

Available on Disney+ on December 25.

Matt Zoller Seitz

Matt Zoller Seitz is the Editor-at-Large of RogerEbert.com, TV critic for New York Magazine and Vulture.com, and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in criticism.

- Jamie Foxx as Joe Gardner (voice)

- Tina Fey as 22 (voice)

- Ahmir-Khalib Thompson as Curly (voice)

- Phylicia Rashād as Libba Gardner (voice)

- Daveed Diggs as Paul (voice)

- John Ratzenberger as (voice)

- Richard Ayoade as Jerry (voice)

- Graham Norton as Moonwind (voice)

- Rachel House as Terry (voice)

- Alice Braga as Jerry (voice)

- Angela Bassett as Dorothea

- Atticus Ross

- Trent Reznor

Cinematographer

- Ian Megibben

- Matt Aspbury

Composer (jazz compositions and arrangements by)

- Jon Batiste

Co-Director

- Kemp Powers

Writer (story and screenplay by)

- Pete Docter

- Kevin Nolting

Leave a comment

Now playing.

Look Into My Eyes

The Front Room

Matt and Mara

The Thicket

The Mother of All Lies

The Paragon

My First Film

Don’t Turn Out the Lights

I’ll Be Right There

The Greatest of All Time

The Substance

Latest articles.

TIFF 2024: Dahomey, Bird, Oh Canada

TIFF 2024: The Cut, The Luckiest Man in America, Nutcrackers

The Telluride Tea: My Diary of the 2024 Telluride Film Festival

Wrapping Up My Experiences at the 2024 Telluride Film Festival

The best movie reviews, in your inbox.

- Editor's Pick

‘A Big Win’: Harvard Expands Kosher Options in Undergraduate Dining Halls

Top Republicans Ask Harvard to Detail Plans for Handling Campus Protests in New Semester

Harvard’s Graduate Union Installs Third New President in Less Than 1 Year

Harvard Settles With Applied Physics Professor Who Sued Over Tenure Denial

Longtime Harvard Social Studies Director Anya Bassett Remembered As ‘Greatest Mentor’

Pixar's 'Soul’ Offers a Thesis on the Meaning of Life, and It’s a Pretty Good One

Dir. pete docter––4.5 stars.

There are technically no rules against an animated film winning the Academy Award for Best Picture. In the 93-year history of the Oscars, however, only three have ever received a nomination (“Beauty and the Beast,” “Up,” and “Toy Story 3”), and none have ever won. When “Wall-E” wasn’t nominated in 2008, critics began to raise questions about whether the existence of the separate “Best Animated Feature” category was inherently harmful — an implicitly degrading statement that animated films must be judged by different standards than live-action ones.

This, in some ways, is besides the point; to delve into a discussion of the Academy’s inner machinations would probably make this review about 20 times longer. But the “Best Animated Feature” category is, in many ways, symptomatic of the way many Americans view animation: as a genre, rather than as a medium. The way we associate animation with fart jokes and cheesy endings makes it difficult to think broader, to produce something mature and thoughtful like “Spirited Away” or “Your Name” — leaving us to define animated movies as “just for kids”

Pixar’s “Soul,” however, blows this definition out of the water.

The film follows Joe Gardner (Jamie Foxx), a middle-school band teacher who’s always dreamed of being a professional jazz pianist. On the day he finally gets his big break — literally moments after being offered the chance to play with one of the jazz greats — he falls into an open manhole and, well, dies.

What follows is a bit less realistic. Instead of proceeding to The Great Beyond like all the other souls, Joe (now an ethereal, glowing, light teal-colored soul) flees to The Great Before — the fantastical celestial plane where new souls get their personalities before proceeding to Earth. There, he meets 22 (Tina Fey), a petulant, jaded new soul who’s not all that jazzed about going to Earth, and together, they devise a plan to return Joe to his earthly body in time for his big gig.

Much like in “Inside Out” (another brainchild of director and Pixar Chief Creative Officer Pete Docter), the far-fetched premise of “Soul” is balanced by how grounded it is in the human condition. It’s okay, for instance, that Joe’s soul inhabits a therapy cat named Mr. Mittens for a good chunk of the second act, because this ultimately allows 22 to recognize the true meaning of life on Earth. And the slapstick is kept to a minimum — replaced with humor that is either very clever or uncannily mature (“Can’t crush a soul here,” 22 says as a building collapses onto a group of new souls in The Great Before. “That’s what life on Earth is for”).

The astral landscapes of The Great Before are just as lush, beautiful, and imaginative as Riley’s mind in “Inside Out.” Purple “trees” are scattered on hills of turquoise “grass” in this land of blue-green pastels and incoherent, fuzzy forms — making for a world that is dream-like in the most literal sense of the word. Particularly striking are the Counselors: the kind, gentle giants that guide new souls through The Great Before. The way they are animated to look both two-dimensional and three-dimensional (sort of like a Picasso portrait brought to life) is visually stunning: a refreshing take on CG animation from the studio that pioneered the craft.

The other half of the film is set in New York, a city that Pixar managed to make just as visually interesting as a literal astral plane. Docter achieves a frenetic, energized depiction of the city that never sleeps and the diverse people it comprises, and everything about the film — from the cinematography to the crowds animation — imbibes Joe’s New York with gritty authenticity. The contrast in scoring, too — between composer Jon Batiste’s jazzy, piano-heavy New York and Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’ (the duo behind “Mank” and “The Social Network”) ethereal, airy underscore to The Great Before — does more than its fair share of narrative and emotional heavy lifting.

And as beautiful as the animation and music are, the real soul (pun intended) of the film lies in its writing. It does, for the most part, follow the typical Pixar story beats, but the way it builds to its final point is masterful: scattering seemingly insignificant plot points throughout the second act, shepherding an ostensibly well-adjusted protagonist through a series of adventures, and having him discover the flaw in his thinking just as the audience does — a puzzle that the viewer assembles right alongside Joe.

The final act is a masterclass in storytelling: in particular, a four-minute sequence near the end manages to — wordlessly, sublimely, poignantly — capture the beauty of the human condition. It is an ending that feels earned, one that will not only leave the viewer (as most good films do) reflecting on their own life, but also (as not many animated films do) wondering if their child can fully grasp its meaning.

“Soul” offers a thesis on the meaning of human life — a difficult question to answer in a 200-page philosophy dissertation, much less a 104-minute animated film. And it does so with all the beauty, detail, and imagination that audiences have come to expect from Pixar. It is a good animated film (indeed, probably an Oscar-worthy one), but more importantly, it is a good film, period. And it is films like “Soul” that prove that animation isn’t just as good as live-action, but — quite often — better.

Pixar's "Soul" is available to stream on Disney+ beginning on Dec. 25.

—Staff writer Kalos K. Chu can be reached at [email protected] . Follow him on Twitter @kaloschu .

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

‘Soul’ Review: From the Minds Behind ‘Inside Out’ Comes an Even Deeper Look at What Makes People Tick

Pixar gives audiences a fresh way to think about the dimension that defines their personality, while broadening its cultural horizons to feature the studio's first predominantly Black cast.

By Peter Debruge

Peter Debruge

Chief Film Critic

- ‘Nutcrackers’ Review: Ben Stiller Gets Saddled With a Farm and Four Rowdy Kids in Easy-Target Heart-Tugger 17 hours ago

- ‘Bonjour Tristesse’ Review: Chloë Sevigny Feels Miscast in Female-Driven Retelling of Françoise Sagan’s Novel 19 hours ago

- ‘The Piano Lesson’ Review: The Washington Family Comes Together Around August Wilson’s Legacy-Themed Masterwork 1 day ago

Where do people get their personalities? Do parents play a part, or are such things somehow determined before birth? For centuries, doctors of psychology, doctors of philosophy and doctors of theology have contributed their thoughts on the subject, but the latest breakthrough comes from another kind of doctor entirely: Pete Docter , the big-idea Pixar brain behind outside-the-box toons “Inside Out” and “Up,” who takes a look deep inside and comes up with another intuitive, easy-to-embrace metaphor for — dare I say it — the meaning of life.

The result is “ Soul ,” a whimsical, musical and boldly metaphysical dramedy about what makes each and everybody tick, featuring a cast of characters who don’t have bodies at all. “Soul” opens with the death of its down-on-his-luck hero, middle school band teacher Joe Gardner (Jamie Foxx), a frustrated pianist who aces a jazz band audition, then steps out into the street, where he narrowly avoids being smushed by construction workers and crushed by an oncoming car, only to fall through a manhole to his untimely end.

Related Stories

High-Resolution 8K Has Its Places, but TV Might Not Be One of Them

'Sunshine' Trailer Debuts Ahead of Toronto Premiere, Spotlights Teenage Pregnancy and Olympic Dreams in the Philippines (EXCLUSIVE)

This is not at all where one expects a kids movie to begin. Not even “Bambi” went so far as to kill its main character before the opening credits. But then, “Soul” plays hardly anything by the rules. Frankly, this may not be a kids movie at all, although releasing directly to Disney Plus subscription service on Dec. 25 (amid COVID-19’s second wave) suggests the studio is treating it as such. Joe’s death isn’t scary, but it asks young audiences to acknowledge the issue of mortality in a way that few films dare. And then, it proceeds to bend — although “shape” might be a more accurate word — their understanding of what happens before and after people’s lives on Earth.

Popular on Variety

Just before he bites the dust, Joe lands his big break, earning a shot to play with jazz legend Dorothea Williams (Angela Bassett) at the Half Note club. Nearly all his life, Joe has wanted nothing more than to be a musician. He’s good, too, given the improvisations we’re privy to here — in class, in rehearsal and later, in the solitude of his own apartment. So it’s not surprising that he might be alarmed to find himself on a conveyor belt through the Great Beyond, the void-like zone Docter and production designer Steve Pilcher have imagined late souls enter just before they are zapped into oblivion.

Again, this sequence could have been intimidating for young viewers — or old ones, for that matter — though the movie treats it lightly, allowing Joe (who’s the only soul with second thoughts about the afterlife) to fall off the escalator and plunge through several dimensions to the Great Before, a more Elysian Fields-ian place with lilac skies and periwinkle grass where giggly, vaguely Casper the Friendly Ghost-like souls are prepped for Earth.

It’s an awe-inspiring answer to an impossible challenge: How to animate the not-yet-animate? But this is a Pixar movie, so it’s no surprise that the team opts to cutesify the abstract idea of a pre-corporeal self, giving each soul googly eyes and a pure glow. What we see are adorable amorphous blobs with trippy chromatic aberration around the edges — color fringing that suggests the virtual lenses can barely capture their elusive luminosity (and the opposite of old-school animation, where characters were “contained” by thick black lines).

There are rules for this realm, which recall the ingenious way Docter translated the notion of human emotion into clean cartoon terms with “Inside Out.” Nascent souls appear here and are guided along by mentors — those who have already lived and seem keen to pass their passions along to the next generation. Once new souls discover their “spark,” they’re given an entry pass to Earth, where they’re presumably assigned to an infant body. (It’s a far more sophisticated explanation of where babies come from than the delivery storks of “Dumbo” — or Pixar’s own “Partly Cloudy” short.)

That’s where Docter’s groundbreaking theory of where people get their personalities factors in: Some components are imprinted at the “You Seminar” (another, more corporate-sounding name for the Great Before), and others are discovered with a little helpful guidance from the older souls. The model isn’t perfect, but there’s a certain brilliance in encouraging kids to identify what excites them in life. One can imagine “Soul” leading to early “eureka” moments in some viewers. Still, the film seems better suited to adult audiences, the way Capra’s “It’s a Wonderful Life” or Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol” resonates differently with a little life experience.

Joe wants to get back to the body that (we learn) is still hooked up to life support. But he’s mistaken for a mentor and randomly assigned to a “soul mate,” No. 22 (Tina Fey), a misfit who’s been around for ages and who seems perfectly content never to “get a life.” In fact, 22 prefers it in the Great Before, where countless, more accomplished mentors than Joe — from Abraham Lincoln to Mother Theresa — have tried (and failed) to find her spark. But the overseers — a trio of classic UPA-style line drawings (Alice Braga, Richard Ayoade and Wes Studi), each named Jerry — are easygoing enough to let these two give it a go, and before long, they find a loophole that lands them both on earth.

It’s going to be hard for “Soul” audiences to keep this next twist a secret, but for the sake of the review, let it be a surprise how the pair manifest on earth. Joe’s desperate to get back to that jazz club, while 22 would give anything not to be dragged along on his single-minded — and clearly selfish — mission to make his jazz dreams come true. (She far prefers her comfortable nonexistence to the assault of overwhelming noises and smells of New York City.) But now that she is alive, 22 starts to realize that it’s not as bad as she imagined.

That’s not a message kids need to hear, though there is surely no shortage of adults out there who wish they’d “never been born at all,” and “Soul” has the generous, big-hearted quality of so many Pixar movies before it that makes even a mediocre life seem like something to be appreciated. Docter and co-writers Mike Jones and Kemp Powers (the latter also co-directed) have filled the back half of the film with scenes that uplift and set receptive souls a-tingling.

First, there’s the barbershop, where Joe comes to realize that his obsession with music has interfered with his ability to make meaningful friendships. There’s the face-to-face with tough-love mom Libba (Phylicia Rashad) that puts some of his parental issues in perspective. And there’s the truly magical moment when Joe sits down at his piano and just starts playing, drifting off into what the movie refers to as “The Zone.” As the sage and slightly kooky-sounding British talkshow host Graham Norton puts it, in character as a mystic named Moonwind, “When joy becomes an obsession, one becomes disconnected from life.”

Of all the movie’s gambles — those big risks that might have caused this dazzling house of cards to collapse upon itself — the most unexpected is Pixar vet Docter telling fellow adults that there’s such a thing as being too focused on one’s dreams. Here’s a lesson coming from a studio where artists notoriously sacrifice their private lives to fulfill their passions, where long hours and absolute focus are expected of their employees. And then Docter goes and pushes his luck one step further with a life lesson hardly any family movie dares acknowledge: Sometimes, achieving your dream can leave you feeling emptier than you did before.

Like it or not, that’s a truth worth telling — a sincere, dark-night-of-the-“Soul” revelation —and one that feels far more radical than the long-overdue decision to center this film on a predominantly Black cast. Pixar’s been way behind the diversity curve for far too long: From its inception, the company has been a boys club in which the core team of (bright) white guys have taken turns directing movies about white characters: white toys, white fish, white cars, white ideas. They’ve made room to mentor, but have been slow to diversify their characters and stories onscreen.

And now this. It will be up to audiences of color to decide whether this exceptional film satisfies Pixar’s long void of near total nonrepresentation. “Coco” was a start, though this feels like a breakthrough: a cartoon where the hero could be any race, and his creators opted to project their imaginations beyond the mirror. And though it’s almost impossible to reverse-engineer who did what in a co-directing situation, one has to imagine that some of the film’s cultural perspective owes to co-director Powers (whose play, “One Night in Miami,” also reaches screen this fall). Judging by Mr. Mittens, the movie’s feline sidekick, the crew was light on cat lovers.

In any case, the unsung hero here — the heart of “Soul,” if you will — can be found in the music. From Betty Boop to the Pink Panther, jazz has shaped and inspired the medium of animation (especially in its more avant garde experiments). Pixar rekindles that connection, enlisting Jon Batiste to create the jazz portion of the score — from the fleet-fingered, Keith Jarrett-like improvisations Joe performs to the vibe of city life itself — while Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross delivered the New Agey sound of the before- and after-life.

It all blends together beautifully, a marriage of Pixar’s square, safe, feel-good sensibility with what could be described as the “real world” — and one that, much as “Inside Out” anthropomorphized the mind, will leave audiences young and old imagining their own souls as glowing idiosyncratic cartoon characters. And that’s just what the Docter ordered.

Reviewed online, Los Angeles, Nov. 22, 2020. MPAA Rating: PG. Running time: 100 MIN.

- Production: (Animated) A Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures release of a Disney presentation of a Pixar Animation Studios production. Producer: Dana Murray. Executive producers: Dan Scanlon, Kiri Hart.

- Crew: Director: Pete Docter. Co-director: Kemp Powers. Screenplay, story: Pete Docter, Mike Jones, Kemp Powers. Editor: Kevin Nolting. Music: Trent Reznor, Atticus Ross. Jazz compositions and arrangements: Jon Batiste.

- With: Jamie Foxx, Tina Fey, Graham Norton, Rachel House, Alice Braga, Richard Ayoade, Phylicia Rashad, Donnell Rawlings, Ahmir-Khalib Thompson aka Questlove, Angela Bassett, Cora Champommier, Margo Hall, Daveed Diggs, Rhodessa Jones, Wes Studi.

More from Variety

How Much Should AI Giants Pay Hollywood? What Insiders Say Has Stalled Any Licensing Deals

Hollywood Must Define AI Technical Standards to Prep for Its Future

More from our brands, celebs serve dinner at glitzy fundraiser in support of fair restaurant wages.

McLaren’s CEO on Supercars, Decarbonization, and Why He’s Optimistic About the Future

Sportico Transactions: Moves and Mergers Roundup for Sept. 6

The Best Loofahs and Body Scrubbers, According to Dermatologists

Beacon 23 and The Winter King Not Returning on MGM+ (Exclusive)

Screen Rant

Soul ending explained: pixar's meaning of life revealed.

Your changes have been saved

Email is sent

Email has already been sent

Please verify your email address.

You’ve reached your account maximum for followed topics.

Soul: 14 Easter Eggs & Secret Pixar References

Pixar's soul: 25 best quotes from the movie, wolfgang van halen: net worth, age, height & everything you need to know about eddie van halen's son.

- 22's spark is simply an appreciation for living, as shown by her excitement for the little things on Earth.

- Joe's life on Earth will be different after his time in the afterlife, focusing on what makes him and others happy.

- It is implied that 22 is living a fulfilled and happy life on Earth after learning valuable lessons from Joe.

Pixar's Soul comes to an emotional conclusion after a harrowing journey between dimensions, so it's no surprise some viewers came away from the film with a few lingering questions. The film imagines a "Great Before," where souls find their "spark" before joining the mortal coil and being born as babies on Earth. With such heady concepts and profound themes as the purpose of life, Soul requires some thinking before all facets of its ending fully take shape.

In Soul , down-on-his-luck jazz musician/middle school band teacher Joe Gardner (Jamie Foxx) finally gets what he hopes will be his big break in the competitive professional scene of New York City jazz, but just before he can seal the deal, he dies, sending him to the Great Before. Despite the fact that Soul seems like Pixar's "first adult movie", as with most Pixar movies, Soul explores existential ideas close to its surface, taking in mortality, the meaning of life, and what life without purpose truly means. Those questions have been a major part of Pixar's pantheon all the way back to Toy Story , but here's how Soul tackles it.

As is tradition with any Pixar movie, the new Disney+ release includes all sorts of hidden references that keen-eyed fans are sure to pick up on.

What 22's Spark Is In Soul & Meaning Of The Maple Leaf Seed

-Cropped.jpg)

One of the biggest mysteries throughout Soul is what 22's spark is , something that isn't explicitly revealed at the end of the film. However, the movie heavily implies that 22's spark is simply an appreciation for living, with her being excited by all the little things on Earth that Joe overlooked in his life. This theme of appreciating life is reinforced when the maple leaf seed lands in Joe's hand at the end of the film. In this moment, Joe takes notice of the leaf and appreciates it, showing his new perspective on life and the joy that he now finds in the little things thanks to 22.

How Joe's Life On Earth Will Be Different

Although Soul ends with Joe being brought back to life, his life on Earth will be much different after his time in the afterlife. Joe has found a newfound appreciation for life, something that he picked up from spending time with 22. Joe realizes that he will not be fulfilled by making big career moves or by being accepted, with Joe presumably using the rest of his life to instead focus on what makes him and those around him happy.

What Happens To 22 After Soul's Ending

One of the biggest questions at the end of Soul is what happens to 22, as she is unseen after she leaves Joe. After giving 22 the maple seed she collected, 22 is prepared to go to Earth, with Joe accompanying her on her journey. After she departs. 22 is most likely living a life on Earth, with her hopefully being fulfilled and happy due to what she learned from Joe before starting her life.

How Is The Cat Still Alive In Soul?

Another major Soul plot hole has to do with how the cat survived , as it would have had no soul after Joe left the cat's body. However, the cat is seen alive again after Joe departs, which is incredibly confusing to some audiences. It could be that another soul jumped into the cat's body right as Joe left. It could also have to do with animal souls working differently from human souls, as animal souls aren't really explained in the film.

How Does Joe Get Back to the You Seminar?

With all this dimension-hopping, audiences would be forgiven for wondering just how Joe returns to the You Seminar after having left the Jerrys for good with 22's Earth badge. The answer lies in his piano. Let's recall that Moonwind and his merry pranksters each gain access to The Zone every Tuesday by meditating in whatever way they can immerse themselves. Joe's chosen form of meditation is music, so he retreats to his piano, enters the zone, and follows a wild, lost 22 through her box portal from The Zone back to the You Seminar to achieve his true goal and make things right.

How Lost Souls and the You Seminar Work

Tina Fey's 22 embodies on her journey to self-actualization after struggling with self-doubt and apathy. Soul suggests that when these feelings take hold of you, as they do 22 during the film's climax, your soul becomes encased in a cocoon of negative feelings. Such is the two-sided coin of The Zone, as Moonbeam describes: passion can consume them in a positive way, but passions and negative feelings alike can lead a soul astray.

The You Seminar is the preceding counterpart to the afterlife. It is run by the Jerrys: various manifestations of " the coming together of all quantized fields of the universe " which take a form legible to the human mind for the benefit of Joe and the audience. Early in Soul , it's established that it's the You Seminar's job to prepare souls to begin life by creating their personalities and helping them find their spark, but it's in the third act that it becomes clear precisely what that spark is , or perhaps more importantly, what it is not .

Joe operates for most of the movie on the mistaken assumption that the You Seminar is meant to give souls their singular purpose, with this being his fatal flaw in the film. However, as a Jerry explains before Joe returns to Earth to play in the Quartet, that understanding is far too simplistic.

The thoughtful and funny dialogue in Pixar's Soul illustrates how it might just be one of the studio's most poignant and touching movies yet.

The Real Meaning Of Soul’s Ending

This is the message writer/director Pete Docter hopes to leave with audiences: l ives don't boil down to some binary success or failure, but rather it's in the way each moment is lived, no matter how small, that gives all time on Earth meaning . Soul posits that one of the best way to be fulfilled is to simply find fulfillment in the small things by living in the moment rather than always being concerned about what is to come.

Furthermore, the film's exploration of lost souls through 22's incapacitating pessimism touches on themes of self-worth, which Soul producer Dana Murray describes as learning to love one's self. The ethereal film continues the existential discussions from Docter's 2015 effort Inside Out , but rest assured, Soul stands on its own two feet as another intriguing investigation into the mortal experience.

Pixar's Soul follows Joe Gardner (Jamie Foxx), a pianist, who is killed in an accident just before his big opportunity to finally succeed in the world of jazz music. Joe's soul gets stuck in the "Great Before", a purgatory which gives him the idea of reuniting his body and soul. Alongside Foxx, Soul features the voices of Tina Fey, Graham Norton, Rachel House, Alice Braga, Richard Ayoade, Phylicia Rashad, and Angela Bassett.

- SR Originals

Disney Pixar’s Soul: how the moviemakers took Plato’s view of existence and added a modern twist

Reader in Historical and Philosophical Theology, King's College London

Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology, University of Oxford

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

King's College London and University of Oxford provide funding as members of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Ideas about the soul have been powerful throughout the history of religion and philosophy. Until the 19th-century, most people took the existence of souls for granted. With the rise of modern psychology, this belief lost its plausibility, and today it is largely absent from academic philosophical and even theological writing.

Many now deny the existence of a soul, considering human emotions and motives simply a function of neurons firing. Disney Pixar’s new film Soul seems to go against the grain of this development.

It presents its viewers with two realms of being. The first is the realm of human activity, where life occurs. The second realm is of the soul – where life has yet to begin, the great before, and where it ends, the great beyond. In their conception of the soul, the producers hark back to some of the most influential ideas of western intellectual history but in an unmistakably 21st-century way.

Souls, bodies and death

The film follows Joe Gardner, an aspiring jazz pianist who is stuck in the rut of his daily life as a part-time middle school music teacher. At the beginning of the film, Joe suffers an accident which leaves him hovering between life and death. The viewer observes Joe’s soul separate from its body as it journeys to the great beyond.

This starting point accurately mirrors the historical origins of western ideas about the soul. The Greek word for soul – psyche – was originally restricted in its use to the context of dying . Homer describes death as the soul’s departure from its body. At the beginning of its history in the west, the soul was evident primarily in its absence from a dead body.

With the rise of Greek philosophy in the 6th century BC, the soul was also seen as the force animating the living body . Meanwhile, the idea of death as the separation of body and soul remained generally accepted.

This created tension. If souls were supposed to enliven a particular body, they had to interact closely with the body and arguably form a unity with it. But then how could the soul survive the body’s decay or even exist separately?

A further difficulty arose from the widely shared belief in reincarnation. Could human souls be born again into the bodies of animals or even plants? And if so, how could they then constitute the operational centre, so to speak, of their current host?

Plato and Aristotle parted ways over these questions. For Plato , the soul’s connection with the body was only accidental. The hero of Plato’s dialogues, Socrates, explained to his friends, hours before his execution, that the philosopher yearns for his death because it marks the liberation of the soul into its true existence.

Plato’s student Aristotle , by contrast, denied that there even was a proper afterlife for the soul. Insofar as the soul was simply the life of the body, he urged, the two formed an indissoluble unity, which death brought to an end.

Things took a further turn with the rise of Christianity. Overall, Christians were more sympathetic to the Platonist view than to its alternatives, because they believed in a life after death . But they rejected the idea of an accidental connection between soul and body. The classical Christian view of the soul as found in Thomas Aquinas fused Platonic with Aristotelian ideas: the soul is immortal but tied in eternity to the identity of a body-soul compound. As such, it will be brought back to life at the end of time.

Pixar’s Platonist conception of the soul

Against this rough sketch of the western history of the soul, Pixar’s position comes closest to the Platonic view. Souls depart from the dying person and travel to the great beyond. Souls also pre-exist their earthly incarnation, and some of them at least don’t seem overly keen to embark on this journey into life. Souls are immaterial - another tenet of Platonic philosophy - although in the movie they are understandably not invisible. Finally, reincarnation seems possible, even across species as Joe finds out when, for a while, he enters the body of a cat.

Yet the parallels only go so far.

Joe Gardner is unwilling to accept his departure from earthly life, and much of the movie deals with his attempts to return to his previous existence. For Plato, this would indicate that Joe was a bad person unable to detach himself from material pleasures. In the film, however, it is this desire that makes Joe remarkable.

His companion, a not-yet-born soul introduced only as number 22, learns more from Joe, due to his unbending will to return to Earth, than she did from the souls of Gandhi, Einstein and Jung, who had previously tutored her in preparation for her birth. In the world of 21st-century New York, into which the two enter through an extraordinary series of events, number 22 suddenly develops a lust for life after experiencing the simple pleasures of living — from eating pizza to watching the leaves fall from a tree.

None of this would have made much sense to Plato. Rather, the film relies on distinctly modern ideas about the affirmation of the present life as worth living on its own terms. The ultimate “purpose” of the soul is to be the “spark” that imparts the simple gift of life.

Joe’s conclusion from his experience as a disembodied soul is to savour every remaining moment of the earthly life he regains at the end of the film. And even number 22 comes to embrace the value of an embodied existence, despite its risks and limitations.

These are ideas well known from romantic and existentialist philosophers of the 19th and 20th centuries. Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834) sneered at the notion of personal immortality as the ridiculous wish to perpetuate one’s own miserable existence . Instead, he posited the idea of “immortality in this moment”. The lesson Joe learns, and wants us to learn, from his unusual experience is rather similar, and points to the thoroughly modern cast into which traditional ideas about the soul have been moulded by the makers of this film.

- Christianity

Service Centre Senior Consultant

Director of STEM

Community member - Training Delivery and Development Committee (Volunteer part-time)

Chief Executive Officer

Head of Evidence to Action

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Movie Reviews

'soul' surprises with its messages about finding purpose.

Eric Deggans

Pixar's new film stars Jamie Foxx as a jazz musician whose soul gets separated from his body. The animated feature explores themes of music and transformation.

Copyright © 2020 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

‘Soul’ Review: Life, and How to Live It

- By David Fear

What is “soul”? ? Is it that feeling you get when you tap into the flow between emotion and expression, the spiritual and the physical? Is it something personal percolating within you, waiting to be unleashed? Is it the essence of humanity in a nutshell? Defining the concept is like aiming at a constantly skittering target. You sense it when you sense it. I know you’ve got soul.

No questions necessary, however, when it comes to understanding what Soul is — all you need to hear is the phrase “the new movie from Pixar .” (Or for that matter, where you can see it: on Disney+, starting Christmas Day .) It’s an animated movie, located right at the crossroads of absurdity and profundity, and likely to tickle funny bones as well as lubricate tear ducts. It will feature celebrity voices, be filled with both pop-culture parodies and high-art references, and present a depth and sophistication far above the usual family-friendly fare. A certain amount of quality is a given. (Unless it involves nothing but anthropomorphic cars. Then all bets are off.) And while Pete Docter’s follow-up to Inside Out is nowhere near that particular Pixar highpoint’s resonance and ingenuity, it does make for an odd fraternal twin to his 2015 teen-angst magnum opus. Whereas that candy-colored trip through an adolescent girl’s cerebral cortex concentrated on the brain, Soul naturally focuses on pinpointing the anima. And that existential query posed up top is one of many deep thoughts that are very much on the movie’s mind. Why are we here? What’s your spark? What makes your life worth living?

For Joe Gardner (voiced by Jamie Foxx ), the answer is: music. Ever since his dad took him downtown to see a performance at the Half Note when he was a boy, all he’s ever wanted to do is to become the next Duke Ellington. Except the now middle-aged Average Joe is stuck teaching standards to mostly disinterested middle-school kids. (The name of the composition his band class is currently butchering: “Things Ain’t What They Used to Be.”) He has the chance to turn this part-time gig into his full-time job, which means stability, a steady paycheck and a dream of a Monk-ish life permanently deferred. Then a call from an old pupil, a drummer (Questlove, because of course!), presents an opportunity. The pianist for the legendary Dorothea Williams Quartet has dropped out at the last second. Would Joe wanna throw his fedora in the ring to replace him?

Editor’s picks

Every awful thing trump has promised to do in a second term, the 250 greatest guitarists of all time, the 500 greatest albums of all time, 25 most influential creators of 2024.

Joe passes both the muster of the skeptical, take-no-shit bandleader (Angela Bassett) and the audition. He’s so ecstatic about his big break that he’s oblivious to the open manhole he falls in, which is where Soul ‘s narrative proper sputters to life. Or rather, into the void: a cosmic conveyor belt carries a small, blobbish figure with glasses and a porkpie-shaped noggin — I Am Joe’s Lifeforce — toward the Great Beyond. He isn’t ready to go into the light, jumps off the heavenly treadmill and soon finds himself in “the Great Before.” Imagine if Fischer-Price designed a pastel purgatory. This is where souls-to-be reside before they fly down to earth, lorded over by walking, talking one-dimensional Picasso sketches all named Jerry. According to those Cubist bureaucrats, the little blue soul-toddlers need mentorship first. They need likes, dislikes, passions, characteristics. They must form a nature-not-nurture personality (“I’m an agreeable skeptic who’s cautious yet flamboyant!”) before they can enter their corporeal phase. Our fugitive from death hatches an escape plan: steal an identity, help a newbie, swipe their “earth pass” and get back to his body before the gig. Easy-peasy, until No. 22 enter the picture.

That’s the Little Soul Who Wouldn’t, a tenacious pain of a shmoo who’s stymied the efforts of past mentors such as Abraham Lincoln and Copernicus, once made Mother Theresa cry and, as voiced by Tina Fey , No. 22 is blessed with a maximum girlboss puckishness that singlehandedly sells the character. No. 22 doesn’t want to discover her purpose for existing. She does not even want to be alive. Joe has to inspire her or perish before he can show the world he’s more than the guy he sees in this limbo’s flashback-accomplishments hallway, i.e. someone who seems to be killing time while waiting for an already-in-progress life to start.

Without venturing too deep into spoiler territory, it’s safe to say they do both end up together on the third rock from the sun, just not how they imagined. Fans of a certain strain of popular ’80s comedies (notably one featuring a famous stand-up, a pioneer of one-woman shows and a magic bowl) are likely to find themselves in pleasantly familiar territory. The fact that Soul features an African-American lead, was cowritten and codirected by the playwright Kemp Powers ( One Night in Miami …) and weaves in aspects of middle-class African-American culture while treating race as a matter of fact — rather than a back-patting novelty, a look-ma-I’m-woke box to be ticked or Hollywoodized exotica — feels quietly revolutionary. So does the rainbow coalition of supporting voices here, which includes Sonia Braga, Rachel House, Wes Studi and Richard Aayode. You’re constantly reminded that no one in the animation game can marshal a mix-and-match of creative talent and a Stradivarius-maestro level of heartstring plucking with such accessibility and verve.

25 Best Pixar Movie Characters

Year in review: the 20 best movies of 2020.

Which is why Soul soars above its two-dimensional ‘toon peers, even if sort of pales in comparison to Pixar’s previous milestones. It doesn’t have the eye-popping wow of Coco (2017), another netherworld jaunt that turned a Dia de los Muertos visual palette into something both culturally specific and universal. There are a number of moments, however, where you can feel the animators’ imagination kick into fourth gear, notably via a psychedelic galleon used by “Mystics Without Borders” and the be-bop aurora borealis that appears when Joe is lost in his own playing, courtesy of Jon Batiste’s vigorous jazz compositions. The rubber-limbed human characters, who come in caricaturish shapes ranging from pear to stringbean, get more of a chance to strut and fret (and wobble and flop and shudder and leap) upon the stage once things switch from Great Before to terra firma, and it’s the slice of life stuff that works even better than the admittedly deft slapstick bits. For that matter, a sequence in a barbershop and a brief heart to heart in the tailor shop Joe’s mom (Phylicia Rashad) do more heavy emotional lifting than the more obvious tearjerking climax(es) as the clock ticks down. Per most Pixar joints, a box of Kleenex is a must-have accessory, though New Yorkers may find themselves welling up more at the sight of our photorealistic city rendered in all its autumnal late-afternoon glory, and still forever blessed with jazz clubs, used bookstores and bustling street life, more than anything else.

Still, there’s a tendency for its story of midlife crises and posthumous second chances to tonally devolve into a self-help guide — a Zen and the Art of Emotional-Cycle Maintenance 101 primer that gets a little touchy-feely about following your bliss by the end. (Though is it preferable to, say, going full Ayn Rand a la The Incredibles ? Yes.) For all of the ways Pixar has helped evolve kids-movie parables as a genre and animation as an art form, it’s still prone to a pop-psychology default mode that can border on platitude pimping — an accusation that won’t necessarily be discounted after dinging Joe for not fulfilling his potential, or seeing the forest for the trees, or acknowledging that the mere notion of a forest full of trees is a joyous miracle unto itself.

There are many elaborate lessons on life and how to live it in Soul, though its best may ironically be its simplest: Look. Listen. Learn. Enjoy. You may not turn the film off with an answer to what a soul is. But you may find yourself wondering if you’re forgetting to occasionally connect with your own.

Jimi Hendrix Documentary Film Coming From 'Greatest Night in Pop' Director

- Life on Screen

- By Tomás Mier

‘His Three Daughters’ Turns a Familiar Family Drama Into the Best Movie of the Year

- MOVIE REVIEW

'Wise Guy: David Chase and The Sopranos' Looks Back at the Iconic Mob Series — and the Man Who Made It

- don't stop believin'

- By Alan Sepinwall

Doug Emhoff Addresses Donald Trump's Attacks on Kamala Harris: 'It’s a Distraction'

- Late-Night TV

- By Emily Zemler

SAG-AFTRA Reaches Interim Agreement on AI Protections With 80 Video Games

- Press Start

Most Popular

Brad pitt and george clooney dance to 4-minute standing ovation for ‘wolfs’ during chaotic venice premiere, richard gere jokes he had "no chemistry" with julia roberts in 'pretty woman', demi moore fuels speculation that she doesn't approve of channing tatum's plans to remake ghost, navarro, pegula highlight billionaire parents at u.s. open, you might also like, ‘the perfect couple’ ending explained: how the netflix series changed the book’s killer finale, grazia usa names very first beauty director, the best yoga mats for any practice, according to instructors, gia coppola ‘tries to not listen to the outside’ when it comes to critics of the coppola dynasty, sportico transactions: moves and mergers roundup for sept. 6.

Rolling Stone is a part of Penske Media Corporation. © 2024 Rolling Stone, LLC. All rights reserved.

Advertisement

Supported by

Critic’s pick

‘Soul’ Review: Pixar’s New Feature Gets Musical, and Metaphysical

This inventive tale stars Jamie Foxx as a jazz musician caught in a world that human souls pass through on their way into and out of life.

- Share full article

By A.O. Scott

In about 100 jaunty, poignant minutes, “ Soul ,” the new Pixar Animation feature, tackles some of the questions that many of us have been losing sleep over since childhood. Why do I exist? What’s the point of being alive? What comes after?

It’s rare for any movie, let alone an all-ages cartoon, to venture into such deep and potentially scary metaphysical territory, but this is hardly the first time that the studio has directed its visual and storytelling resources toward mighty philosophical themes. “Soul” follows “Coco” in conjuring a detailed vision of the afterlife — and also, in this case, the before-life — and joins “Inside Out” in turning abstract concepts into funny characters and vivid landscapes. The world that human souls pass through on our way into and out of life is a glowing, minimalist realm of embodied metaphors and galaxy-brain jokes, populated by blobby, ectoplasmic souls and squiggly bureaucratic “counselors” named Jerry.

But at the same time, “Soul,” directed by Pete Docter and Kemp Powers from a screenplay they wrote with Mike Jones, represents a new chapter in Pixar’s expansion of realism. (Slated to open in theaters earlier this year, it is streaming on Disney+ .) Having conquered fish scales in “Finding Nemo,” beastly fur in “Monsters Inc.,” metal in “Cars” and vermin in “ Ratatouille ,” the animators have set themselves more subtle challenges.

Though other Pixar projects have visited actual places (Paris, San Francisco, the Great Barrier Reef), this is the first to dive fully into the multisensory moods of a living city, chasing after its rhythms, its folkways, its architectural details. “Soul” is a movie about death, about jazz, about longing and limitation. It’s also a New York movie.

As such, it traffics in a brusque urbanist sentimentality that isn’t immune to or afraid of cliché. The sensory riot of the city includes squalling car horns, clattering trains, bagels, slices of pizza, barbershops, subway platforms and the perpetual-motion bustle of pedestrians, strollers, yellow cabs and more. Everything we used to complain about and miss desperately now.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Down The Hobbit Hole Blog

7 Lessons from Soul + Discussion Questions and Parent Review

7 Lessons from Soul + Soul Discussion Questions written by the Elf and the Ent . This post contains affiliate links, you can find out more on our policies page or in the disclaimer at the bottom of the blog.

Know Before You Watch the movie Soul

Quick summary of the movie soul:, -is soul appropriate-, -plot/story of the movie soul-, -character development in soul-, soul discussion questions, final thoughts.

Movie : Soul Rating : PG Run time : 1 hr. 30 mins. Genre : Family, Comedy Age suggested : 5 and up Release Date : December 25th, 2020 Where to Stream It? : As of December 25th, it is streaming exclusively to Disney Plus subscribers at no additional cost. Themes : Purpose, Drive, Beauty of Life and Music Warnings : Main plot revolves around a character who has died, slight toilet and crude humor, minimal scary images. And, as with any Pixar/Disney movie, have those tissues handy.

Joe Gardener is passionate about Jazz but not as excited about his teaching gig. He is just about to fulfill his lifelong dream when something goes terribly wrong and he ends up in the Soul world. He’s got to figure out how to help someone else as well as himself before he can get back to earth.

While the movie goes to incredibly deep and sometimes confusing depths in it’s plot, it’s a beautiful watch for the whole family! This movie is one that will naturally spark great conversations about your passions, differences, dreams, and hopefully even about your Creator.

Keep reading for our parent review of soul and 7 lessons from soul…

Parent Review of Soul *Minimal Spoilers*

Besides a couple of crude (but fairly innocent) jokes, there isn’t much inappropriate in the movie. The movie does deal a lot with the concept of death and the afterlife, so be prepared to discuss this with your kids. There are a few image that might be a little scary for younger viewers- namely the lost souls- , but not nearly as scary as in most Disney/Pixar movies. And while younger viewers might be easily bored by the movie, I would not say that it’s inappropriate or very scary.

You can also get plushies for Joe here and 22 here !

The Story of Soul goes through several different twists and turns while having a consistent through line that lasts the entire movie. It may get a little complicated for younger viewers as it goes in and out of the Soul world. This is compensated for by the art style and design as the people and surroundings look very different in each world, which makes it a little easier to follow. Both styles are absolutely fantastic, balancing very well between cartoon and realism. (I loved this article by Crosswalk that talks about the fact that you might not be able to answer all of your or your kids questions about the plot of the movie- but there is still a TON to discuss!

Joe’s journey through the afterlife is absolutely wonderful. The plot follows him as he must learn what it truly means to live while also mentoring a being who has never understood why anyone would ever want to live on earth. Although not quite as emotional as other Pixar movies (which makes it more appropriate for whole family viewing), Soul is filled with just as much heart and passion. The plot is boldly complex, but not one that lost my kids or myself in the process.

Joe and 22 are polar opposites at the beginning of the movie, and this provides a great backdrop for everything they go through. All of the characters, including the side ones, add so much depth to their respective worlds. The beings who are in charge of the soul world come of as completely different creatures than humans while still showing all the human like qualities. Perhaps the most heartbreaking characters are the “lost souls” because unfortunately they can be the most relatable for adults.

During a year when so much racism has been brought out into the sunlight, it’s great to see a leading family that’s Black and positive, happy, Black life stories. As a teacher, I really cannot stress the depth and importance of representation. It really does matter to kids. Not only does the movie do it well onscreen, but the cast and movie makers are diverse as well- and it’s wonderful!

Overall, the characters in Soul make for a great movie that simultaneously drags adults into the plot while remaining goofy and silly enough for the younger viewers.

Keep reading for our Lessons from Soul and Soul discussion questions.

7 Lessons from Soul **SPOILERS Beyond This Point**

Another line to tell you that there are SPOILERS ahead!!

1) It’s the little things which make life beautiful

From the taste of pizza to the leaves of trees, there are so many things in our life that we really do find lovely that we have stopped appreciating. It is important to be intentional about taking the time to rediscover these things.

2) There’s always time to find your spark

22 shows us that there is always time to find your spark. She seemingly has been in the soul world for several millennia and simply never found her spark for life. Her impressive mentor list is so much fun. But she finds out that there is still time for her.

3) Life is worth living

Although life can have many setbacks and difficulties, it is also filled with potential, love, beauty and glory. We have to pay attention and look for it. At the end of film, Joe doesn’t exactly know what he wants to do with his life, but he does know one thing: he wants to live his life.

**I’d like to note here as well that I think the film did a good job bringing up things that keep us stuck in life, like depression, in a kid friendly, but also responsible way. The stuck, or lost, souls in the movie can’t just shake off whatever is literally plaguing them. They have to have help. And reader, if you’re stuck, now is the time to ask for help from a counselor or doctor- even reaching out to a trusted mentor or friend!**

4) Our different passions make us and life beautiful.

There is no one thing that gives everyone a spark, or that brings you to the plane between eternity and earth. And we don’t always understand each others.

Positive representation of diverse characters is important. I love that the lead in this movie was an Arts centric Black man with a cast of strong supportive females behind him. And that the secondary lead was voiced my a strong female. (There is also room her to discuss gender fluidity and that people all have souls and are all just people if it’s something you want to dive into with your kids after viewing.)

5) Our positive and negative words IMPACT people.

Joe’s mothers words stick with him in ways she didn’t intend. When he expresses that, there’s a beautiful moment of positive impact as well. Students talk about how much Joe has impacted their lives, even helping them get through school. The leaders of the souls are constantly working to inspire. And, in one of the more heartbreaking scenes, we see the words of past mentors that 22 has joked about as she really feels them- they torment her.

One of life’s most important lessons. Your life matters, and how you use your life and your words impacts others in ways you will never fully know.

6) You and your life are more than your spark and purpose.

Your spark and those moments of feeling your purpose are important and amazing. But life is about a lot more than those plateaus. Joe’s afraid that he’s wasted his life but when he looks back, he sees how beautiful and wonderful his life has been. And he’s been given the chance to appreciate all those little moments again.

There are lots of different things that can make us happy and help us bring joy to the world. Life is amazing! I would discuss with my kids again how God made each of us unique.

7) Achieving a dream, or starting a new year, doesn’t fix your life.

When one of the characters finally reaches what they’ve been wanting to get to- it’s not as fulfilling as they were expecting. It reminds me of Tangled when Rapunzel finally gets to see the lanterns fill up the night sky. Something she’s wanted for years. But it doesn’t solve her problems and now that she’s achieved her dream, what’s left? She enjoyed it, took stock of what was important, (got kidnapped again) and started to dream again. What a marvelous lesson (besides the kidnapping drama) as we go into a year that we’re collectively putting so much weight on. We can hope for a lot of wonderful, life-changing, positive moments in 2021- but it’s not going to heal all our underlying wounds by itself.

What did you take from this movie?! Keep reading for our Soul Discussion questions!

- Who was your favorite character in the movie and why?

- Why do you think God give us different personalities when we’re born?

- People have different things that allow them to enter the Soul world momentarily. What brings you enough happiness to enter that in between plane in the Soul world?

- What is something simple in life that you underappreciate? (If younger kids: what things do you like that you do everyday?)

- 22 finds herself surrounded by negative comments that were made to her. How does she overcome this negativity? How do you or can you overcome negativity?

- Who are you a positive voice for? Who can you be a positive voice for in the future?

- What is something you can appreciate in life now more than before after seeing this movie?

- What is the most amazing thing you’ve ever seen?

- What is one of your dreams that you would like to accomplish?

- What’s something that God’s gifted you with that feels like one of your sparks?

While it would have been amazing to see on the big screen, I can’t think of a better movie to watch at home with your whole family before the start of the new year. We would highly encourage you to watch this one WITH your kids and take some time to talk about your sparks and discuss happy moments and dreams together afterwards. You may no be able to answer every question about the story or plot- but don’t miss the amazing opportunity this movie provides us in talking about how amazing life and people are.

Thanks for checking out our Lessons from Soul and Soul Discussion Questions. Before you go- check out these other posts :

– Parent review of Coco : A little boy with a love of music finds himself celebrating Dia De Muertes in an unexpecting way.

– 5 Lessons from Frozen 2 : the sequel to Disney’s big hit that dives further into the fantastical world of Arendelle

– 3 Lessons From Trolls: World Tour : The worlds of music collide as rock music tries to take over all of the Troll worlds

– 3 Lessons from Spies in Disguise : Tom Holland and Will Smith team up in this great movie about a bumbling engineering genius and world renowned spy.

Down The Hobbit Hole Blog and this Soul discussion questions, Lessons from Soul and Soul review post uses affiliate links, we only link products we think you’ll like and you are never charged extra for them. As Amazon Associates, we earn from qualifying purchases at no additional cost to you. We also use cookies to gather analytics and present advertisements. This allows us to keep writing discussion questions and telling ridiculous dad jokes.

31 thoughts on “7 Lessons from Soul + Discussion Questions and Parent Review”

I love reading your reviews, and this parent review for Soul and the lessons from the movie are terrific. I only have so much time to watch movies. This looks very worthwhile!

This Soul Parent Review sounds quite interesting. It is good to know that it is appropriate for children. Thanks for sharing.

Thank you for your review! I have been thinking of watching this movie, and now I feel like I really want to! 🙂

I really enjoyed reading your review. We plan to watch Soul tomorrow night since it will be our last day having Disney= and I’m really looking forward to it. I’ve seen a lot of positive reviews about this movie so I’m hoping we all enjoy it.

thanks for sharing. I had not been interested in seeing the movie but maybe I’ll take a peek.

p.s. great discussion questions

Thanks so much for the compliment! I wasn’t super excited about watching it at first, but I’m so glad I did! Hope you enjoy it!

Soul is one of my favorite animated movies of the past 10 years. I watched it as soon as it came out on Disney+, and it blew me away. There really is a lot to be learned from it.

I agree! Definitely deserves to be on top 10 lists! Thanks for stopping by and commenting 🙂

My three kids AND my husband and I all loved this movie. Of course, they kids loved it for all the reasons that kids normally love Pixar movies, but my husband and I actually took quite a lot away from its message, too.

Yes!! So many good messages!! I’m so glad that you all enjoyed it!! 🙂

One of the reasons I love Soul so much is that it teaches such valuable lessons to both children and adults. Kids aren’t the only ones who need refreshers on so many parts of life.

That’s so true!! Kid’s definitely are not the only ones who can take away some great lessons from the movie. It reminded me of so many things, but especially to remember to value the things I think are mundane.

I haven’t seen Soul yet, but it sounds like it deals with some complex themes while still being entertaining for the kids. I love your discussion guide for after the film!

It really does deal with a lot while also being super entertaining! Thanks for the complement- hope it’s useful!

We have seen Soul three times since it came out. I love the message and the delivery. It was perfect!

We agree! So glad you loved it too!

A lot of people seems to be impressed with Disney Plus and it’s content, and I have been a bit… naah, not right now, my kid dont need more movies, but you’ve got a great way of watching with the kids 🙂 I loved reading your review!

That absolutely makes sense! We understand that! It is wonderful to watch some of them with the kids. Thanks so much for the compliment and for stopping by to comment 🙂

I’ve seen so many mixed reviews on the film. But I do also think it’s a great way to start discussions on death and the afterlife. There’s not another film like it, so I think that’s why many people are undecided on watching.

That makes sense! It is such a great way to discuss big life topics for sure!

I really enjoyed watching this with my daughter. It is nice to watch a movie that has so many wonderful messages!

I absolutely agree! Thanks for commenting 🙂

It sounds really interesting and I enjoy a good comedy these days at home. Thanks for letting us know about this and I will bookmark this one for the weekend 🙂 Knycx Journeying

I hope that you get to watch it and enjoy it! Thanks for stopping by

That was a super interesting review of the movie Soul. I think I will give it a shot with my girlfriend.

Thanks for the compliment. I hope that you get to watch it and enjoy it!

I have never seen movie Soul, but I love family comedies. Thanks for this review!

Thanks for stopping by!! It really is a great movie for the whole family.

Many people recommended me to watch this animated movie. And I hear that it’s truly great. Now you confirm that again in your post. Ok, I will go to the cinema tomorrow for this.

Thanks for stopping by! Hope you enjoy the movie!!

I loved reading your review. So well-executed… Although I rarely watch movies these days but I’ll take a peek.

Comments are closed.

The Film “Soul” by Pixar: Understanding Plato’s Rhetoric Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Plato’s account of the soul, the pixar’s account of the soul, how the film soul helps to understand plato’s noble rhetoric, works cited.

Throughout the history of religion and philosophy, ideas about the soul have dominated the various views and thoughts about life on earth. In western philosophy and religion, the central belief about the soul resides in a living being but departs from a dying individual and travels to another spiritual world beyond the earth. Moreover, the soul pre-exists in its earthly incarnation and is immaterial. These views appear in Plato’s writings and Disney Pixar’s film Soul .

Plato, in his noble rhetoric, views the soul as the spirit or force that gives life to the body. The soul comes from the great beyond into the body of a person before birth but departs the dying body and travels far away beyond human knowledge. In Pixar’s film, there are two realms of the soul- human activity and the soul. Life is yet to begin in the soul realm, before its end, and beyond. Using scenarios and characters that represent real-life situations, Pixar’s film Soul helps the viewers develop a good understanding of Plato’s noble rhetoric about the soul by simply defining the nature of the soul as pre-existing, body-soul dualism, afterlife, and immortality.

Plato believes that the function of the soul in the conception of noble rhetoric is the ability of the orator to understand other people and execute the art of rhetoric. The rhetorical method consists of determining the nature of the soul in rhetoric, which is the only way to understand the body (Yunis 106). As Socrates says, one cannot understand the nature of something without studying it as a whole. Therefore, determining the heart of the soul means exploring the whole world.

The orator determines when to speak or hold back, appeal for pity, and exaggerate in a speech. That is the only way to know that they have mastered the art of rhetoric (Herrick 147). It is doing what the souls desire without any prior knowledge. It is being able to stand before a person and recognize their character, which assists in securing a conviction about specific issues (The School of Life 0:57-1:07). It is also easy to know a person’s character by listening to their opinions about a particular subject and contribution.

Plato uses the concept of charioteers to represent intellect, reason, and truth. He figuratively uses the charioteers to show the two outcomes of soul recognition. The chariot represents the souls, while the charioteer is the one who steers the chariot or the soul (The School of Life 1:09-1:28). One horse has a noble character, while the other is the opposite. The excellent horse represents the rational and moral impulse of a character’s nature. The other represents a particular soul’s irrational passions, appetites, and desires. The work of the charioteer is to guide the soul toward the truth.

Pixar’s film Soul is about the three dimensions of the soul- Great Before, the earth, and the Great beyond. According to Plato, the body is just the carrier of the soul. However, the soul is what gives the body life and character. When Joe’s soul leaves his body, he lies unconscious. When 22’s soul inhabits Joe’s body, she gives it a different character or at least one who speaks something apart from jazz with the barber, Dez.

Unlike the immortal soul, the body can experience harm and decay. The charioteers steer the soul in the right direction. In this case, the collaboration between the counselors, Jerry, Joe, and Moonwind, assists in steering 22 in the right direction. She finds her spark somewhere in between the earth and the great before. When she is forced back to the great early, she becomes a lost soul. The film directs the viewers to the notion that people get their spark from the minor things in life, such as watching the stars, walking, and eating pizza. Even though Joe took it as a regular old living, 22 shows her otherwise.

When Joe falls into the manhole of a sewer, the viewers see his soul leave the body and start its journey to the great beyond. This confirms that death separates the body and soul, as Joe’s body lies in the sewer while his soul wanders between life and death. Plato points out that death marks the soul’s liberation from its natural and authentic existence (White 230). The existence of the Great Before confirms that souls pre-exist before birth, with a purpose, personality, and character. The presence of the great beyond shows that souls do not die.

The soul is formed to signify the soul’s willingness to deal with society’s expectations alongside individual dreams. It represents the individuals stuck in a trance where they cannot find their true purpose in life. The movie goes beyond personal ambition and achievements. It emphasizes living in the moment and enjoying life. It is about those who think a purpose has a daily job, a monthly salary, or a considerable achievement recognizable to the whole world. It is formed to inform, persuade and awaken people from a state of trance for them to start living.

Joe is a nobleman who tries to make ends meet as he lives his dream in music. According to her mother, plans do not pay bills or provide food, which is true. Regardless, it is beautiful how he is willing to trade that for chasing his dreams. It is closely connected to the idea of the ancient Greek concept of Philautia, or self-love and devotion to one’s desires (Bucibo, 3:55-5:27). Joe is not planning to take a full-time job at the school. The good in the movie is portrayed by how Joe helped 22 to find her spark. He was ready to sacrifice his position on earth for 22 and proceed to the “Great Beyond.”

In the film, several persuades the viewer to think about the soul, its nature, and its concept as it relates to human life. To many people, understanding the noble rhetoric about the soul by Platos could be difficult because it is presented in a philosophical approach. However, Pixar’s film uses real-life characters and scenarios to offer concrete examples that show the nature of the soul, as Plato suggests, which helps achieve soul suasion among the audience.

The film uses real-life scenarios and characters to picture better Plato’s account of how lost souls are led to enlightenment. Joe and 22 are presented as good examples of those souls. Plato’s analogy of the charioteers is perfectly explained in the film. Joe’s soul strongly resists going to the ‘Great Beyond’ and directs him to the ‘Great Before’. This is because of his desire to go back to earth and live his life. However, later, he returns to find his purpose and his spark. Just like the charioteer steers the wrong horse go the right direction when 22 becomes a lost soul in a trance, Joe goes to find her. He uses the objects she collected while on earth to lead her to the right direction. When the horse loses its wings and falls to the ground, it symbolizes the lost souls who could not find their purpose in life.

Secondly, the film provides strong evidence that the soul is immortal. In this case, it is essential to note that the soul is eternal and indestructible, as shown in the film’s scenes when 22 was a lost soul. The visuals showed Joe penetrating a dark substance that resembled evil and self-judgment to get to her soul. It means that not even evil can destroy the soul. The film shows that the soul is where the desires are aligned with the moral compass and enlightenment. With the art of rhetoric, one can understand the language of other souls.