- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Emancipation Proclamation

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 29, 2023 | Original: October 29, 2009

On September 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that as of January 1, 1863, all enslaved people in the states currently engaged in rebellion against the Union “shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

Lincoln didn’t actually free all of the approximately 4 million men, women and children held in slavery in the United States when he signed the formal Emancipation Proclamation the following January. The document applied only to enslaved people in the Confederacy, and not to those in the border states that remained loyal to the Union.

But although it was presented chiefly as a military measure, the proclamation marked a crucial shift in Lincoln’s views on slavery. Emancipation would redefine the Civil War , turning it from a struggle to preserve the Union to one focused on ending slavery, and set a decisive course for how the nation would be reshaped after that historic conflict.

Abe Lincoln's Developing Views on Slavery

Sectional tensions over slavery in the United States had been building for decades by 1854, when Congress’ passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act opened territory that had previously been closed to slavery according to the Missouri Compromise . Opposition to the act led to the formation of the Republican Party in 1854 and revived the failing political career of an Illinois lawyer named Abraham Lincoln, who rose from obscurity to national prominence and claimed the Republican nomination for president in 1860.

Lincoln personally hated slavery, and considered it immoral. "If the negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that 'all men are created equal;' and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man's making a slave of another," he said in a now-famous speech in Peoria, Illinois, in 1854. But Lincoln didn’t believe the Constitution gave the federal government the power to abolish it in the states where it already existed, only to prevent its establishment to new western territories that would eventually become states. In his first inaugural address in early 1861, he declared that he had “no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with slavery in the States where it exists.” By that time, however, seven Southern states had already seceded from the Union, forming the Confederate States of America and setting the stage for the Civil War.

First Years of the Civil War

At the outset of that conflict, Lincoln insisted that the war was not about freeing enslaved people in the South but about preserving the Union. Four border slave states (Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri) remained on the Union side, and many others in the North also opposed abolition. When one of his generals, John C. Frémont, put Missouri under martial law, declaring that Confederate sympathizers would have their property seized, and their enslaved people would be freed (the first emancipation proclamation of the war), Lincoln directed him to reverse that policy, and later removed him from command.

But hundreds of enslaved men, women and children were fleeing to Union-controlled areas in the South, such as Fortress Monroe in Virginia, where Gen. Benjamin F. Butler had declared them “contraband” of war, defying the Fugitive Slave Law mandating their return to their owners. Abolitionists argued that freeing enslaved people in the South would help the Union win the war, as enslaved labor was vital to the Confederate war effort.

In July 1862, Congress passed the Militia Act, which allowed Black men to serve in the U.S. armed forces as laborers, and the Confiscation Act, which mandated that enslaved people seized from Confederate supporters would be declared forever free. Lincoln also tried to get the border states to agree to gradual emancipation, including compensation to enslavers, with little success. When abolitionists criticized him for not coming out with a stronger emancipation policy, Lincoln replied that he valued saving the Union over all else.

“My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union and is not either to save or to destroy slavery,” he wrote in an editorial published in the Daily National Intelligencer in August 1862. “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.”

From Preliminary to Formal Emancipation Proclamation

At the same time however, Lincoln’s cabinet was mulling over the document that would become the Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln had written a draft in late July, and while some of his advisers supported it, others were anxious. William H. Seward, Lincoln’s secretary of state, urged the president to wait to announce emancipation until the Union won a significant victory on the battlefield, and Lincoln took his advice.

On September 17, 1862, Union troops halted the advance of Confederate forces led by Gen. Robert E. Lee near Sharpsburg, Maryland, in the Battle of Antietam . Days later, Lincoln went public with the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which called on all Confederate states to rejoin the Union within 100 days—by January 1, 1863—or their slaves would be declared “thenceforward, and forever free.”

On January 1, Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, which included nothing about gradual emancipation, compensation for enslavers or Black emigration and colonization, a policy Lincoln had supported in the past. Lincoln justified emancipation as a wartime measure, and was careful to apply it only to the Confederate states currently in rebellion. Exempt from the proclamation were the four border slave states and all or parts of three Confederate states controlled by the Union Army.

Impact of the Emancipation Proclamation

As Lincoln’s decree applied only to territory outside the realm of his control, the Emancipation Proclamation had little actual effect on freeing any of the nation’s enslaved people. But its symbolic power was enormous, as it announced freedom for enslaved people as one of the North’s war aims, alongside preserving the Union itself. It also had practical effects: Nations like Britain and France, which had previously considered supporting the Confederacy to expand their power and influence, backed off due to their steadfast opposition to slavery. Black Americans were permitted to serve in the Union Army for the first time, and nearly 200,000 would do so by the end of the war.

Finally, the Emancipation Proclamation paved the way for the permanent abolition of slavery in the United States. As Lincoln and his allies in Congress realized emancipation would have no constitutional basis after the war ended, they soon began working to enact a Constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. By the end of January 1865, both houses of Congress had passed the 13th Amendment , and it was ratified that December.

"It is my greatest and most enduring contribution to the history of the war,” Lincoln said of emancipation in February 1865, two months before his assassination. “It is, in fact, the central act of my administration, and the great event of the 19th century."

HISTORY Vault: Abraham Lincoln

A definitive biography of the 16th U.S. president, the man who led the country during its bloodiest war and greatest crisis.

The Emancipation Proclamation, National Archives

10 Facts: The Emancipation Proclamation, American Battlefield Trust

Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York: W.W. Norton, 2010)

Allen C. Guelzo, “Emancipation and the Quest for Freedom.” National Park Service .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Preliminary and Final Emancipation Proclamations

- September 22, 1862

- January 1, 1863

No related resources

Introduction

After the war began, enslaved African Americans sought to free themselves by heading for Union Army encampments and installations. Union officers and enlisted men dealt with them in a variety of ways, sometimes putting them to work, but in some cases returning them to their so-called owners. Both Lincoln and Congress sought to regularize the treatment of the escapees, as well as protect them, through their respective constitutional powers and as the necessities of war dictated. In the preliminary Proclamation, Lincoln mentioned two of the laws Congress had passed to that effect.

The Emancipation Proclamations in a sense developed from the effort to deal with those who freed themselves by escaping to Union lines, because it justified emancipation as a war measure under the president’s powers as commander in chief of the armed forces. The Proclamations, however, covered not just the enslaved persons who escaped to freedom but, under the same presidential power, all those held in territory in rebellion against the United States. The final Proclamation declared furthermore that freedmen would be “received into the armed service of the United States.” As a war measure, the Proclamations did not apply to slaves in states that remained loyal. In this case, Lincoln proposed to compensate slave owners who freed their slaves. The preliminary Proclamation also stated that voluntary colonization measures would continue.

Lincoln knew that emancipation would not be universally approved (for opposition to Lincoln’s policies, see To Erastus Corning et al. ). In fact, it seems to have cost the Republicans at the midterm elections in 1862. But African Americans and opponents of slavery alike recognized it as the beginning of the end of slavery in the United States. The final Proclamation made the Union Army a liberating force as it advanced into rebel territory and brought freedom to every person that the Proclamation had made legally free. The Proclamation also built momentum for an amendment to the Constitution to ban slavery in the nation forever.

Abraham Lincoln, Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, 1862, Abraham Lincoln papers: Series 1, General Correspondence, Manuscript/Mixed Material, Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/item/mal1859300/

Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, September 22, 1862 By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation.

I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States of America, and Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy thereof, do hereby proclaim and declare that hereafter, as heretofore, the war will be prosecuted for the object of practically restoring the constitutional relation between the United States and each of the states, and the people thereof, in which states that relation is, or may be, suspended or disturbed.

That it is my purpose upon the next meeting of Congress to again recommend the adoption of a practical measure tendering pecuniary aid to the free acceptance or rejection of all slave states, so called, the people whereof may not then be in rebellion against the United States and which states may then have voluntarily adopted, or thereafter may voluntarily adopt, immediate or gradual abolishment of slavery within their respective limits; and that the effort to colonize persons of African descent, with their consent, upon this continent, or elsewhere, with the previously obtained consent of the governments existing there, will be continued.

That on the first day of January in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any state, or designated part of a state, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

That the executive will, on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the states, and part of states, if any, in which the people thereof respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any state, or the people thereof shall, on that day be, in good faith represented in the Congress of the United States, by members chosen thereto, at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such state shall have participated, shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such state and the people thereof, are not then in rebellion against the United States.

That attention is hereby called to an act of Congress entitled “An Act to make an additional Article of War” approved March 13, 1862, and which act is in the words and figure following:

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, that hereafter the following shall be promulgated as an additional article of war for the government of the army of the United States, and shall be obeyed and observed as such:

Article—All officers or persons in the military or naval service of the United States are prohibited from employing any of the forces under their respective commands for the purpose of returning fugitives from service or labor, who may have escaped from any persons to whom such service or labor is claimed to be due, and any officer who shall be found guilty by a court martial of violating this article shall be dismissed from the service.

Sec. 2. And be it further enacted, that this act shall take effect from and after its passage.

Also to the ninth and tenth sections of an act entitled “An Act to suppress Insurrection, to punish Treason and Rebellion, to seize and confiscate property of rebels, and for other purposes,” approved July 17, 1862, and which sections are in the words and figures following:

Sec. 9. And be it further enacted, That all slaves of persons who shall hereafter be engaged in rebellion against the government of the United States, or who shall in any way give aid or comfort thereto, escaping from such persons and taking refuge within the lines of the army; and all slaves captured from such persons or deserted by them and coming under the control of the government of the United States; and all slaves of such persons found on (or) being within any place occupied by rebel forces and afterward occupied by the forces of the United States, shall be deemed captives of war, and shall be forever free of their servitude and not again held as slaves.

Sec. 10. And be it further enacted, That no slave escaping into any state, territory, or the District of Columbia from any other state shall be delivered up, or in any way impeded or hindered of his liberty, except for crime or some offense against the laws, unless the person claiming said fugitive shall first make oath that the person to whom the labor or service of such fugitive is alleged to be due is his lawful owner, and has not borne arms against the United States in the present rebellion, nor in any way given aid and comfort thereto; and no person engaged in the military or naval service of the United States shall, under any pretense whatever, assume to decide on the validity of the claim of any person to the service or labor of any other person, or surrender up any such person to the claimant, on pain of being dismissed from the service.

And I do hereby enjoin upon and order all persons engaged in the military and naval service of the United States to observe, obey, and enforce, within their respective spheres of service, the act, and sections above recited.

And the Executive will in due time recommend that all citizens of the United States who shall have remained loyal thereto throughout the rebellion, shall (upon the restoration of the constitutional relation between the United States, and their respective states, and people, if that relation shall have been suspended or disturbed) be compensated for all losses by acts of the United States, including the loss of slaves.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand, and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington this twenty-second day of September, in the year of our Lord, one thousand, eight hundred and sixty-two, and of the Independence of the United States the eighty-seventh.

Emancipation Proclamation, January 1, 1863 By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation.

Whereas, on the twenty-second day of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-two, a proclamation was issued by the president of the United States, containing, among other things, the following, to wit:

That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any state or designated part of a state, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

That the Executive will, on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the states and parts of states, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any state, or the people thereof, shall on that day be, in good faith, represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such state shall have participated, shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such state, and the people thereof, are not then in rebellion against the United States.

Now, therefore I, Abraham Lincoln, president of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as commander in chief of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do, on this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and in accordance with my purpose so to do publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days, from the day first above mentioned, order and designate as the states and parts of states wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States, the following, to wit:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, (except the parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans) Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth), and which excepted parts are for the present left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated states, and parts of states, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defense; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God. In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the city of Washington, this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and of the Independence of the United States of America the eighty-seventh.

Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation

Proclamation suspending the writ of habeas corpus, see our list of programs.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

Check out our collection of primary source readers

Our Core Document Collection allows students to read history in the words of those who made it. Available in hard copy and for download.

Emancipation Proclamation — One of President Abraham Lincoln's Greatest Accomplishments

January 1, 1863

The Emancipation Proclamation was issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863. It stated that people held as slaves in areas that were in rebellion against the United States were free.

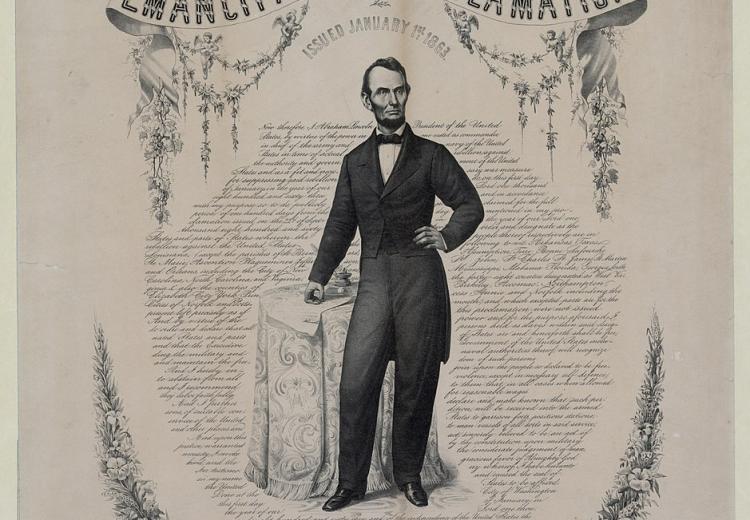

On January 1, 1863, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing slaves in areas in rebellion against the United States. Just before signing his executive order, Lincoln declared, “I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right than I do in signing this paper.” Image Source: Wikipedia.

Emancipation Proclamation Summary

The Emancipation Proclamation was a proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, that declared all “all persons held as slaves” in the states that were in rebellion against the United States were “henceforward…free.”

After decades of division over slavery, the Secession Crisis erupted after Abraham Lincoln won the Presidential Election of 1860. Southern states left the Union, starting on December 20, 1860. They believed they had the right to secede, but Lincoln and others saw it as a rebellion against the government, and that it was necessary to preserve the Union.

Soon after the war started, Federal officials started looking at ways to keep the Confederacy from utilizing enslaved people in the war effort. Congress passed two laws for the purpose of depriving the Southern states of slaves that were captured by the Union Army, but it failed to turn the tide of the war.

In the North, there were people who believed emancipation would strengthen the war effort. In July 1862, President Lincoln introduced the concept of emancipation for Southern slaves to the members of his cabinet. His cabinet agreed but also wanted to wait to go public with the announcement until the Union had won a major victory on the battlefield.

On September 17, 1862, Union forces won a strategic victory at the Battle of Antietam and five days later, Lincoln signed the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation . In the proclamation, Lincoln said the ongoing purpose of the war was to restore the Union, but also said anyone held in slavery in any territory in rebellion against the United States would be “forever free.”

The Southern states had 100 days to rejoin the Union or risk losing their slaves. None of them withdrew from the Confederacy and Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863 , which declared slaves in rebellious territories to be free.

The proclamation was an important step toward the abolition of slavery in the United States, which culminated in the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment on December 18, 1865.

Emancipation Proclamation Facts and Dates

- On August 6, 1861, Congress passed the First Confiscation Act conferring “contraband” status on slaves being used in direct support of the Confederate war effort.

- On March 13, 1862, Congress enacted an article of war that stated prohibited all officers or persons in the military or naval service of the United States from returning fugitives slaves to their owners.

- On July 17, 1862, Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act.

- President Lincoln began drafting the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in early July 1862.

- President Lincoln introduced the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation to his cabinet at a meeting on July 22, 186.

- President Lincoln publicly introduced the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, five days after the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam.

- The Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation stated that people held in slavery in designated areas in rebellion against the United States as of January 1, 1863, would be freed.

- President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863.

- In February 1865, shortly before his assassination, President Lincoln described the Emancipation Proclamation as “the central act of my administration and the great event of the nineteenth century.”

Emancipation Proclamation Overview and History

For over fifty years, the practice of slavery in the United States engendered a sectional schism between the North and the South that became so deep that the two sides could no longer peacefully coexist. When Southern states began leaving the Union on December 20, 1860, their secessionist leaders asserted that they were exercising their inherent right to leave an alliance of states based on the “consent of the governed.” Unionists, including President-Elect Abraham Lincoln , painted the conflict as a rebellion against the United States government. For them, the war was about preserving the Union.

When war erupted in April 1861 at Fort Sumter, South Carolina , many believed that the conflict would not last long. They reasoned that the newly forming Confederacy of Southern states stood little chance against the might of the more densely populated North. Despite an embarrassing defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run , predictions of an early Union victory seemed accurate by June 1862. With Major General George McClellan and his massive Army of the Potomac camped within sight of the church spires of Richmond, the fall of the Confederate capital seemed inevitable. Events soon proved that conclusion to be incorrect.

After severe wounds incapacitated General Joseph Johnston at the Battle of Seven Pines on May 31, 1862 , Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed General Robert E. Lee to command what would become the Army of Northern Virginia. Lee assumed the burden of saving Richmond.

Rather than continuing the defensive posture of his predecessor, Lee went on the offensive. In a stunning series of six engagements between June 25 to July 2, 1862, known as the Seven Days Battles , Lee drove McClellan’s Army away from Richmond and nearly back to the Atlantic Ocean.

Sensing that McClellan no longer posed a serious threat, Lee pushed his army north and defeated Major General John Pope and his newly created Army of Virginia at the Second Battle of Bull Run (August 28–30, 1862) . Emboldened by the defeat of both major Union armies in the Eastern Theater, Lee next took the war to Northern soil in the late summer of 1862. On September 4, the Army of Northern Virginia began crossing the Potomac River into Maryland.

August 1861 — First Confiscation Act

As the war dragged on, federal officials stepped up their efforts to deprive the Confederacy of services being rendered by slaves. As early as August 6, 1861, Congress passed the First Confiscation Act conferring “contraband” status on slaves being used to support the Confederate war effort. In effect, the bill made slaves captured by Union armies the property of the U.S. government, much like any other contraband captured during combat.

On March 13, 1862, Congress strengthened the intent of the First Confiscation Act by enacting an article of war that stated:

All officers or persons in the military or naval service of the United States are prohibited from employing any of the forces under their respective commands for the purpose of returning fugitives from service or labor, who may have escaped from any persons to whom such service or labor is claimed to be due, and any officer who shall be found guilty by a court-martial of violating this article shall be dismissed from the service.

July 1862 — Second Confiscation Act

On July 17, 1862, Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act . Applicable only in areas occupied by Union armies, the new measure required individuals in rebellion against the United States to surrender within sixty days of the legislation’s enactment. The act provided that slaves owned by those who did not comply were to “be deemed captives of war, and shall be forever free of their servitude, and not again held as slaves.” The law inched closer to general emancipation by further stipulating that no fugitive slave “shall be delivered up . . . unless the person claiming said fugitive shall first make oath” to be the “lawful owner” and that the claimant was not in rebellion against the United States.

July 22, 1862 — Lincoln Presents the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation

As the Union’s fortunes on the battlefield languished, the claim that emancipation would strengthen the federal war effort became increasingly compelling. By early July, President Lincoln was already drafting a presidential proclamation for blanket emancipation. At a cabinet meeting on July 22, 1862, the President formally introduced the idea .

Lincoln was not seeking guidance or approval regarding his decision; he had decided to proceed. Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles, recalled the president stated that he, “had made a covenant with God. . . . that if the army drove the enemy from Maryland he would issue his Emancipation Proclamation.”

According to Welles, Lincoln presented emancipation as “a military necessity, absolutely essential to the preservation of the Union. We must free the slaves or be ourselves subdued. The slaves were undeniably an element of strength to those who had their service, and we must decide whether that element should be with us or against us.”

The only item open for discussion was the timing of the announcement. Lincoln agreed with the suggestion of Secretary of State William H. Seward that the decision not be disclosed publicly until Union forces could back it with a major victory on the battlefield.

The president had to wait nearly two months for the victory he needed. On September 17, 1862, the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia engaged near Sharpsburg, Maryland. In the bloodiest single day of fighting in the American Civil War, the Battle of Antietam ended in a tactical draw . Still, the Union claimed a strategic victory when Robert E. Lee withdrew his forces from Maryland two days after the battle.

September 22, 1862 — Lincoln Signs the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation

On September 22, 1862, Lincoln signed the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Calling upon his authority as President of the United States and Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy, Lincoln proclaimed,

That on the first day of January in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

Although Lincoln asserted in the opening paragraph of the document that “the war will be prosecuted for the object of practically restoring the constitutional relation between the United States, and each of the States,” the presidential proclamation redefined the purpose of the Civil War . Lincoln’s disclaimer aside, henceforward, the document made it clear that freeing the slaves was as much of the focus of the war as it was about restoring the Union.

January 1, 1863 — Lincoln Signs the Emancipation Proclamation

Initially, the proclamation had little impact on the prosecution of the war. Lee won another great victory at the Battle of Fredericksburg (December 11–15, 1862) . Not surprisingly, no southern states withdrew from the Confederacy during the 100-day grace period the president proposed. Despite Republican setbacks in the November, mid-term congressional elections, Lincoln did not back down. On January 1, 1863, just before signing a revised and expanded version of the executive order, Lincoln stated,

I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right than I do in signing this paper.

In the final draft of the Emancipation Proclamation , President Lincoln did four important things:

- He placed greater emphasis on his authority as Commander-in-Chief to justify his actions. After summarizing the contents of the preliminary document, the president characterized his decision as “a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion.” Toward the end, he described the proclamation as “an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity.”

- He specifically designated the areas in rebellion against the United States where slaves were freed. Those areas included, “Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, (except the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans) Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia, (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth, and which excepted parts, are for the present, left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.”

- He enjoined “upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence.”

- He declared that freed slaves of “suitable condition” would “be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.” This provision significantly impacted the outcome of the war. Not only was the Confederacy deprived of the benefit of forced labor, but some blacks who escaped slavery during the rest of the war joined the Union forces in droves. In the east, men volunteered and joined the 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry Regiment . In the west, volunteers signed up for the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry Regiment .

Outcome of the Emancipation Proclamation

Reaction to the proclamation may have been as significant as the document itself. Critics were quick to note that the executive order freed few, if any, slaves since it applied only to areas in rebellion, where the government had no effective authority. Although applauded by many abolitionists, the document did not go far enough to appease others who had been clamoring for blanket emancipation since before the beginning of the Civil War.

On the international stage, the transformation of the war from a political event to a moral crusade may have been influential in preventing foreign intervention by European powers. At home, some Northerners who initially supported the war to preserve the Union lost their enthusiasm for continuing the conflict because they refused to champion a crusade to free slaves. As expected, the proclamation was nearly universally condemned in the South and undoubtedly steeled the resolve of Southerners to continue the conflict.

Through it all, Lincoln stood by his conviction that he did all he could within the bounds of his constitutional authority as President of the United States and as Commander-in-Chief to bring an end to slavery. In February 1865, shortly before his assassination, Lincoln described the Emancipation Proclamation as “the central act of my administration and the great event of the nineteenth century.”

Emancipation Proclamation Significance

While the Emancipation Proclamation freed slaves only in areas in rebellion against the United States, it was a crucial step toward the adoption of a national policy abolishing slavery.

In 1864 and 1865, the states of Arkansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Missouri, and Tennessee passed new state constitutions outlawing the peculiar institution. With Lincoln’s support, on April 8, 1864, the U.S. Senate passed a proposed amendment to the constitution abolishing slavery nationwide.

The House of Representatives followed suit on January 31, 1865. On December 6, 1865, Georgia became the twenty-seventh state to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment , which outlawed “slavery and involuntary servitude” in the United States.

On December 18, Secretary of State William Henry Seward declared the Thirteenth Amendment officially ratified and part of the United States Constitution.

Emancipation Proclamation APUSH, Review, Notes, Study Guide

Use the following links and videos to study Abolition, the Secession Crisis, and the Civil War for the AP US History Exam. Also, be sure to look at our Guide to the AP US History Exam .

Emancipation Proclamation Definition APUSH

The Emancipation Proclamation is defined as an executive order issued by President Abraham Lincoln in 1862 during the American Civil War. The proclamation, which declared that all slaves in the Confederate States and rebellious territories were to be “thenceforward and forever free,” was seen as a major turning point in the Civil War and as a key moment in the history of the United States. The proclamation, which did not apply to the Border States or to slaves in the Northern states, was seen as a way to weaken the Confederacy and to encourage enslaved people to flee to Union lines.

Emancipation Proclamation Video for APUSH Notes

This video from the Daily Bellringer discusses the Emancipation Proclamation.

- Written by Harry Searles

Chapter 15: The Civil War, 1860-1865

Primary source reading: the emancipation proclamation, introduction.

The Emancipation Proclamation was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, as a war measure during the American Civil War, directed to all of the areas in rebellion and all segments of the executive branch (including the Army and Navy) of the United States. It proclaimed the freedom of slaves in the ten states that were still in rebellion. Because it was issued under the President’s war powers, it necessarily excluded areas not in rebellion – it applied to more than 3 million of the 4 million slaves in the U.S. at the time. The Proclamation was based on the president’s constitutional authority as commander in chief of the armed forces; it was not a law passed by Congress. The Proclamation also ordered that suitable persons among those freed could be enrolled into the paid service of United States’ forces, and ordered the Union Army (and all segments of the Executive branch) to “recognize and maintain the freedom of” the ex-slaves. The Proclamation did not compensate the owners, did not outlaw slavery, and did not grant citizenship to the ex-slaves (called freedmen). It made the eradication of slavery an explicit war goal, in addition to the goal of reuniting the Union.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emancipation_Proclamation

The Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation is the popular name given to two complementary Presidential Proclamations issued 100 days apart from each other by United States President Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War. These are officially known as Proclamation 93 and Proclamation 95.

Proclamation 93, the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, was issued on September 22, 1862. It declared the freedom of all slaves in any state of the Confederate States of America as did not return to Union control by January 1, 1863. Proclamation 95, the final Emancipation Proclamation was issued on January 1, 1863. This enumerated the specific states where it applied.

Proclamation 95

By the President of the United States of America:

A PROCLAMATION.

Whereas, on the twenty-second day of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-two, a proclamation was issued by the President of the United States, containing, among other things, the following, to wit:

‘‘That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

‘‘That the Executive will, on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State, or the people thereof, shall on that day be, in good faith, represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such State shall have participated, shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State, and the people thereof, are not then in rebellion against the United States.’’

Now, Therefore, I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief, of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do, on this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and in accordance with my purpose so to do publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days, from the day first above mentioned, order and designate as the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States, the following, to wit:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana (except the parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James, Ascension, Assumption, Terrebone, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the city of New Orleans), Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkeley, Accomac, Northhampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Anne, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth), and which excepted parts, are for the present, left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

In Witness Whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done US Great Seal 1877 drawing.png at the City of Washington, this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty three, and of the Independence of the United States of America the eighty-seventh.

- Introduction to the Emancipation Proclamation. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emancipation_Proclamation . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Emancipation Proclamation. Provided by : Wikisource. Located at : https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Emancipation_Proclamation . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

The Emancipation Proclamation: Freedom's First Steps

Portrait of President Abraham Lincoln surrounded by the words of the Emancipation Proclamation (1863).

Wikipedia Commons

"And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God." –Abraham Lincoln, The Emancipation Proclamation, Jan. 1, 1863

While the Civil War began as a war to restore the Union, not to end slavery, by 1862 President Abraham Lincoln came to believe that he could save the Union only by broadening the goals of the war. The Emancipation Proclamation is generally regarded as marking this sharp change in the goals of Lincoln's war policy. Under his authority as the Commander in Chief, President Lincoln proclaimed the emancipation, or freeing, of the enslaved African Americans living in the states of the Confederacy which were in rebellion.

The Proclamation was, in the words of Frederick Douglass, "the first step on the part of the nation in its departure from the thralldom of the ages." Through examination of the original document, related writings of Lincoln as well as little known first person accounts of African Americans during the war, students can return to this "first step" and explore the obstacles and alternatives we faced in making the journey toward "a more perfect Union."

Guiding Questions

Why and how did President Abraham Lincoln issue the Emancipation Proclamation?

What was its impact on the course of the war?

Learning Objectives

Evaluate the provisions of the Emancipation Proclamation and its intended effect on the waging of the Civil War

Trace the stages that led to Lincoln's formulation of this policy

Explore African American opinion on the Proclamation

Document the multifaceted significance of the Emancipation Proclamation within the context of the Civil War era

Lesson Plan Details

President Abraham Lincoln and the Northern States entered the Civil War to preserve the Union rather than to free the slaves, but within a relatively short time emancipation became a necessary war aim. Yet neither Congress nor the president knew exactly what constitutional powers they had in this area; according to the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Roger Brooks Taney, they had none. Lincoln believed that the Constitution gave the Union whatever powers it needed to preserve itself, and that he, as commander-in-chief in a time of war, had the authority to use those powers.

Between March and July of 1862, Lincoln advocated compensated emancipation of slaves living in the "border states", i.e., slave states of Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri which remained loyal to the Union. He also endorsed colonization of freed slaves to foreign lands. But by July 1862, the Union war efforts in Virginia were going badly and pressure was growing to remove the Union commander, General George B. McClellan. Mr. Lincoln decided that emancipation of slaves in areas in rebellion was militarily necessary to put an end to secession and was constitutionally justified by his powers as commander in chief.

Members of Abraham Lincoln's cabinet gathered at the White House on July 22, 1862, to hear the president read his draft of the Emancipation Proclamation . Written by Lincoln alone, without consultation from his cabinet, the proclamation declared that all persons held as slaves in states that were still in rebellion on January 1, 1863, "shall be then, thenceforward, and forever, free."

In September 22 1862, after the Union's victory at Antietam, Lincoln met with his cabinet to refine his July draft and announce what is now known as the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation . In this document, he issued an ultimatum to the seceded states: Return to the Union by New Year's Day or freedom will be extended to all slaves within your borders.

The decree also left room for a plan of compensated emancipation. No Confederate states took the offer, and on January 1 Lincoln presented the Emancipation Proclamation. At one stroke, Lincoln declared that over 3 million African American slaves "henceforward shall be free," that the "military and naval authorities" would now "recognize and maintain" that freedom, and that these newly freed slaves would "be received into the armed service of the United States" in order to make war on their former masters. This allowed black soldiers to fight for the Union -- soldiers that were desperately needed. It also tied the issue of slavery directly to the war. By the end of the war, almost 200,000 black soldiers and sailors had fought for the Union and freedom.

It is important to remember that the Emancipation Proclamation did not free all slaves in the United States. Rather, it declared free only those slaves living in states not under Union control. William Seward, Lincoln's secretary of state, commented, "We show our sympathy with slavery by emancipating slaves where we cannot reach them and holding them in bondage where we can set them free." Lincoln was fully aware of the irony, but he did not want to antagonize the "border states" by setting their slaves free.

Intended both as a war and propaganda measure, the Emancipation Proclamation initially had far more symbolic than real impact, because the federal government had no means to enforce it at the time. But the document clearly and irrevocably notified the South and the world that the war was being fought not just to preserve the Union, but to put an end to the "peculiar institution." Eventually, as Union armies occupied more and more southern territory, the Proclamation turned into reality, as thousands of slaves were set free by the advancing federal troops.

The proclamation set a national course toward the final abolition of slavery in the United States. No one appreciated better than Lincoln that to make good on the Emancipation Proclamation was dependent on a Union victory. No one was more anxious than Lincoln to take the necessary additional steps to bring about actual freedom. Thus, he proposed that the Republican Party include in its 1864 platform a plank calling for the abolition of slavery by constitutional amendment. The passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution on December 18, 1865 declared slavery illegal in every part of the newly restored Union.

The Emancipation Proclamation was, in the words of Professor Allen Guelzo, "the single most far-reaching, even revolutionary, act of any American president." Lincoln rated the Proclamation as the greatest of his accomplishments: "It is the central act of my administration and the great event of the nineteenth century."

NCSS.D2.His.1.9-12. Evaluate how historical events and developments were shaped by unique circumstances of time and place as well as broader historical contexts.

NCSS.D2.His.2.9-12. Analyze change and continuity in historical eras.

NCSS.D2.His.3.9-12. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to assess how the significance of their actions changes over time and is shaped by the historical context.

NCSS.D2.His.4.9-12. Analyze complex and interacting factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras.

NCSS.D2.His.14.9-12. Analyze multiple and complex causes and effects of events in the past.

NCSS.D2.His.15.9-12. Distinguish between long-term causes and triggering events in developing a historical argument.

NCSS.D2.His.16.9-12. Integrate evidence from multiple relevant historical sources and interpretations into a reasoned argument about the past.

- Review the lesson plan and the websites used throughout. Locate and bookmark suggested materials and websites. Download and print out documents you will use and duplicate copies as necessary for student viewing.

- The PDF contains an excerpted version of the document used in Activity 2, as well as questions for students to answer. Print out and make an appropriate number of copies of the handouts you plan to use in class.

- Students can access the websites used in this lesson and some of the activities via the Study Activities for Activities 1 , 2 , and 3 . Bookmark the Study Activities URLs for student use.

- View the above video lecture on Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation by close reading of a document by Dickinson College historian Matthew Pinsker.

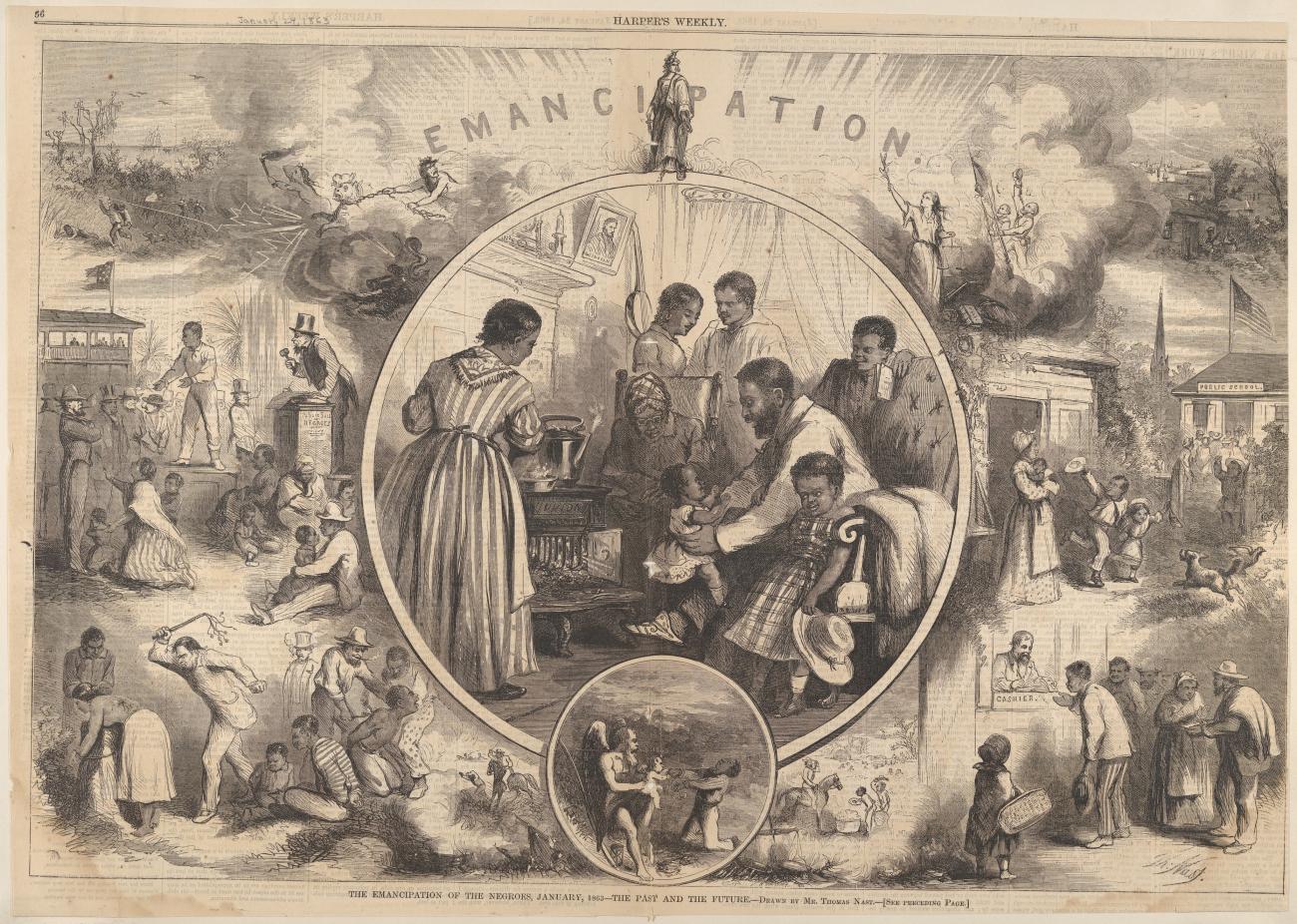

- Read the background information for this lesson and the short introduction to the document from the National Archives Education site, an EDSITEment-reviewed website. There is useful chapter on President Lincoln's Emancipation Policies, a section of The End of Slavery: The Creation of 13th Amendment from the EDSITEment-reviewed HarpWeek .

- This lesson assumes some knowledge of the political realities and constitutional doctrines which limited President Lincoln's options regarding emancipation during the Civil War. One of the leading scholars on the subject, Allen C. Guelzo, has written an excellent short account of these issues in " The Great Event of the Nineteenth Century": Lincoln Issues the Emancipation Proclamation " available through the EDSITEment-reviewed website Internet Public Library.

- The story of how the nation greeted the Proclamation is told by John Hope Franklin in The Emancipation Proclamation: An Act of Justice at the National Archives site.

- Finally, for a fascinating account of how the document's reputation has changed over the last century and a half, teachers can listen to a podcast of a seminar by Professor Guelzo available at the EDSITEment-reviewed Teaching American History .

Activity 1. An Introduction to the Emancipation Proclamation

Note: This activity is available as a Study Activity.

Begin by having students view the above video produced by the History Channel and then do a careful reading of both the brief description of The Emancipation Proclamation and the text itself available at the National Archives and Records Administration . Have students identify the main features of Proclamation by answering these questions of the document:

- Upon what authority does Lincoln issue this proclamation?

- Why is emancipation proclaimed as a "fit and necessary war measure"?

- Why does the proclamation only apply to slaves in certain states? Why is the geographical location significant?

- What does Lincoln encourage these freed slaves to do and to refrain from doing?

- Explain how each of these provisions was expected to contribute to the Union war effort.

- Invite student comment on the relatively limited emancipation Lincoln proclaimed.

- How does language of this document contrast with that of Lincoln's more famous speeches like the Gettysburg Address or the Second Inaugural Address? Why might the bland, legalistic language of the Proclamation be more appropriate in this situation and its purpose?

Activity 2. The Steps that led to the Emancipation Proclamation

Note: This activity is available as a Study Activity .

After viewing the National Geographic video on the Emancipation Proclamation , have students organize research teams to investigate the steps that led to the Emancipation Proclamation. In order for students to understand how President Lincoln's war plans changed in the course of the war, have them read the short discussion of President Lincoln's Emancipation Policies . This section includes a timeline, newspaper editorials and cartoons illustrating the issues surrounding emancipation. Call attention to the passages from the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation of 1862 included in the final document. Have student research teams prepare class reports on this preliminary proclamation and other documents that record Lincoln's deliberations on the issue of emancipation. Students will be able to search for terms such as "emancipation" throughout the Lincoln writings online in The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln available via the EDSITEment-reviewed American Memory .

- How did Lincoln view the "cause" of emancipation in offering this plan?

- Why might his plan have been rejected by abolitionists?

- Why might it have been rejected by the "border states"?

- What might have been the reaction of African Americans?

- What does this document reveal about Lincoln's views on the relationship between emancipation and the essential principles of American constitutional democracy?

- What can we infer from the document about the views held by those to whom he wrote?

- In his Annual Message to Congress, Lincoln's proposal for emancipation has three elements. What are they? Which ones are absent from the Emancipation Proclamation?

- Why does Lincoln's proposal require several constitutional amendments?

- How did these official pronouncements fit into Lincoln's war plans?

- What do they reveal about his struggle to attract and maintain political support?

- From Lincoln's point of view, how significant was the Emancipation Proclamation in his effort to define and exert his leadership in the crisis of the Civil War?

- How significant has it become in our view of him as a national leader?

- Have students share their reports in class and comment on the various pressures and personal beliefs that influenced Lincoln as he shaped his final policy on emancipation.

Activity 3. The African American Perspective

An important perspective on emancipation is that of African Americans on both sides of the battle lines. For insight into the attitudes of this segment of the population, direct students to the documents in Free at Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom, and the Civil War which is part of the EDSITEment reviewed Freedmen and Southern Society Project . Ask students to read the letter from the Mother of a Northern Black Soldier to the President, July 31, 1863 and consider the following questions:

- Who wrote this letter?

- What do you know about this individual from the letter?

- Under what circumstances was this letter written?

- Why was this letter written, i.e., what action(s) does the author request of President Lincoln?

- Upon what grounds does she make her request?

- What most concerns her regarding the Proclamation?

- What do we learn from this letter about emancipation?

- How would you describe the tone of this letter? Is the tone important? Why or why not?

Next have students read the letter of a Massachusetts Black Corporal to the President, September 28, 1863 written by Corporal James H. Gooding of the 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry (the troops celebrated in the film Glory ), which complains to Lincoln of unequal pay for white and African American soldiers and consider these questions:

- What do we know about this individual?

- Why was this letter written, i.e., what "common grievance" motivates the author to write to Lincoln?

- What important distinction does he bring to the attention of Lincoln?

- List some of the facts which he uses to support this distinction.

- Why does the author not consider himself and his men "fit subjects for the Contraband act"?

- Why does he address Lincoln as the "chief Magistrate of the Nation"?

Selected EDSITEment Websites

- Mr. Lincoln's Virtual Library

- The Emancipation Proclamation

- Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation

- Reply to a committee of Chicago religious leaders September 13, 1862

- Annual Message to Congress, December 1, 1862

- Emancipation Proclamation

- A House Divided

- Mother of a Northern Black Soldier to the President, July 31, 1863

- Massachusetts Black Corporal to the President, September 28, 1863

Lincoln's Emancipation Policies

- The Great Event of the Nineteenth Century: Lincoln Issues the Emancipation Proclamation

- Appeal to Border-State Representatives for Compensated Emancipation, Washington, DC. July 12, 1862

- The Fight for Equal Rights Black Soldiers in the Civil War

- The Emancipation Proclamation Seminar

- J.H. Gooding's Letter to President Lincoln

Materials & Media

The emancipation proclamation: freedom's first steps: worksheet 1, related on edsitement, activity 1. introduction to the emancipation proclamation, emancipation proclamation: activity 2. the steps that led to emancipation, emancipation proclamation: activity 3. the african american perspective, lincoln on the american union: a word fitly spoken.

National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Plan Your Visit

- Group Visits

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility Options

- Sweet Home Café

- Museum Store

- Museum Maps

- Our Mobile App

- Search the Collection

- Exhibitions

- Initiatives

- Museum Centers

- Publications

- Digital Resource Guide

- The Searchable Museum

- Freedmen's Bureau Search Portal

- Early Childhood

- Talking About Race

- Digital Learning

- Strategic Partnerships

- Ways to Give

- Internships & Fellowships

- Today at the Museum

- Upcoming Events

- Ongoing Tours & Activities

- Past Events

- Host an Event at NMAAHC

- About the Museum

- The Building

- Meet Our Curators

- Founding Donors

- Corporate Leadership Councils

- NMAAHC Annual Reports

The Emancipation Proclamation: Striking a Mighty Blow to Slavery

The year 2023 marks the 160th anniversary of one of the most important documents in the nation’s history, the Emancipation Proclamation. The Executive Order issued by President Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War provided freedom to enslaved Black people in the rebelling states. Though slavery continued to legally exist in the nation, in slave-holding states that had not left the union, the Emancipation Proclamation marked a major turning point in the hard fought battle to end slavery nationwide.

Well before the creation of the Emancipation Proclamation African Americans, enslaved and free, understood the meaning and importance of freedom. They resisted the bondage of slavery and sought freedom by any means, through thought, word, and deed. Faith provided a foundation for Black people to seize moments of meditation to envision freedom. Through oral and written traditions of speeches, sermons, and printed publications, including news articles and abolitionist pamphlets, Black people forced the discussion on freedom and its inclusive application. They seized freedom through their actions including running away from enslavement and towards freedom.

We use the video player Able Player to provide captions and audio descriptions. Able Player performs best using web browsers Google Chrome, Firefox, and Edge. If you are using Safari as your browser, use the play button to continue the video after each audio description. We apologize for the inconvenience.

The museum commemorates the 160th Anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation by publishing a video featuring NMAAHC historians and staff reading the Emancipation Proclamation in its entirety and reflecting on its significance today. The video also includes footage from the museum’s galleries and the Searchable Museum.

The 1820s and 1830s saw a growth in interracial alliances that formed the small but mighty Abolitionist Movement to end slavery. By the 1850s the country was heading toward war as states fought over whether the expanding nation would be bound by slavery or live up to the ideal of liberty, indeed freedom for all. The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act required everyone in the nation to enforce enslavement by turning in all Black freedom-seekers. Federal officials were bound to returning human property to enslavers. Additionally, the Supreme Court majority opinion also known as the “Dred Scott decision” – declared Black people were not citizens and that “a Black man has no rights which a white man must respect.”

The Case of Dred Scott in the United States Supreme Court

Large group of slaves standing in front of buildings on Smith's Plantation, Beaufort, South Carolina

Membership certificate to the American Colonization Society

Gallery Modal

In November 1860, Republican presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln was elected President of the United States. Though Lincoln was an advocate for ending the spread of slavery, he strategically prioritized keeping the Union together in the splintering nation. He favored gradual emancipation and colonization of free African Americans.

Just one month after Lincoln was elected to the highest office in the nation, the slave-holding state of South Carolina seceded from the Union. Other states soon followed. The states’ secession documents clearly indicate that slavery was at the heart of the matter:

Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery-- the greatest material interest of the world. Its labor supplies the product which constitutes by far the largest and most important portions of commerce of the earth. . . a blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization. A Declaration of the Immediate Causes which Induce and Justify the Secession of the State of Mississippi from the Federal Union.

The people of Georgia having dissolved their political connection with the Government of the United States of America, present to their confederates, and the world, the causes which have led to the separation. For the last ten years we have had numerous and serious causes of complaint against our non-slaveholding confederate States, with reference to the subject of African slavery. They have endeavored to weaken our security, to disturb our domestic peace and tranquility, and persistently refused to comply with their express constitutional obligations to us in reference to that property. Georgia Declaration of Secession

“She [Texas] was received as a commonwealth holding, maintaining, and protecting the institution known as negro slavery--the servitude of the African to the white race within her limits--a relation . . . which her people intended should exist in all future time.” A Declaration of the Causes which Impel the State of Texas to Secede from the Federal Union.

By February 1861, the seceding states formed the Confederate States of America and appointed Jefferson Davis as the provisional President. Two months later the Civil War began as the Confederates fired upon Fort Sumter in S.C. Lincoln’s battle to keep the Union together was spurred on by the seceding Southern states demand that the institution of slavery be upheld.

Frederick Douglass and other influential Black men and women used their influence, as they urged President Lincoln to emancipate all enslaved people in the nation. Abolitionist Frederick Douglas declared “Fire must be met with water, darkness with light, and war for the destruction of liberty must be met with war for the destruction of slavery.” He also advocated for Black men to serve in the military and join the fight for freedom. Douglass saw military service to ensure a Union success and a pathway to citizenship for the formerly enslaved.

In April 1862, President Lincoln successfully worked with Congress to pass a bill for the emancipation of African Americans enslaved in the nation’s capital. Washington, D.C. was not only the seat of political power, but it was also a hub for slave trading activity, home to many fugitive enslaved people and in close proximity to many sites of rebellion. The Act required a form of reparations for former enslavers as they were granted ninety days to file claims for compensation for their loss of human property. A few months later, Lincoln issued the Confiscation Act of 1862, expanding the Union’s ability to seize enemy property, including human property enslavers in the seceding states. A surge of enslaved Black men, women and children seized their freedom and fled to Union Army lines.

Tintype of a Civil War soldier

![emancipation proclamation essay intro Albumen print stereograph titled [No. 2594 "Contrabands" made happy by employment as army teamsters. This shows a glimpse of their first "free" home; being their winter quarters near City Point, Va.] from the series [1861-1865 The War for the Union: --Photographic History] published by John C. Taylor. The streograph images depict eight men standing in a line looking directly at the camera. The men wear a variety of uniforms and all are wearing hats. The men stand in front of a large wagon with wheels visibl](https://nmaahc.si.edu/sites/default/files/styles/max_1300x1300/public/2022-12/NMAAHC-2018_105_9_001.jpeg?itok=syy0e5VR)

No. 2594: "Contrabands" made happy by employment as army teamsters. This shows a glimpse of their first "free" home; being their winter quarters near City Point, Va.

Read an Introduction to the Emancipation Proclamation, Smithsonian Edition, written by NMAAHC curator Paul Gardullo.

Following the success of the Union Army at Antietam, on Sept. 22, 1862, Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Under his wartime authority as Commander-in-Chief, he ordered that, as of Jan. 1, 1863, all enslaved individuals in all areas still in rebellion against the United States “henceforward shall be free.”

On December 31st, 1862, African Americans both free and enslaved, along with others who supported the end of slavery, waited for the midnight hour for the Emancipation Proclamation to go into effect. They gathered in churches across the nation praying their way to freedom. The occasion came to be known as “Watch Night,” a New Year’s Eve ritual still practiced among Black church congregations today. President Lincoln signed the Executive Order on January 1, 1863, granting freedom to enslaved African American men, women, and children in the rebelling states. Pastor John C. Gibbs of Philadelphia’s First African Presbyterian Church declared, “The Proclamation has gone forth, and God is saying to this nation by its legitimate constitute head, Man must be free.”

The Proclamation also enabled African American men to enlist in the Union Army and stand on the frontlines in the battle for freedom. They fought to liberate themselves, their loved ones, and their community.

Waiting for the Hour

Emancipation Day, Richmond, Va.

The Emancipation Proclamation went into effect immediately freeing enslaved Black people in the rebelling states, but it took the Civil war to enforce the order. The Union secured victory in April 1865 when the Confederates surrendered at Appomattox. On June 19th, 1865, the Union Army arrived in Galveston, TX, the rebelling state farthest west, enforcing the freedom guaranteed over two years earlier in the Emancipation Proclamation. The moment is known as Juneteenth .

The Civil War was the battle cry for the country to define itself once and for all as an enslaving or free nation. Though the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery throughout the nation, it struck a mighty blow to the system of slavery. The passage of the 13th Amendment, ratified in December 1865, declared the legal end of slavery in the United States.

Ambrotype of three women in dotted calico dresses

Through great sacrifice many American men and women fought for and supported the Union victory.

Black people, enslaved and free, held on to their humanity and fought for freedom from as early as the Colonial period. They pushed the country to fulfill the highest ideal of liberty, by ensuring a more inclusive manifestation of freedom. Their unyielding efforts brought the country out of the bondage of enslavement.

Sources: Rothman, Adam. Slave Country: American Expansion and the Origins of the Deep South. 3/31/07 ed., Harvard UP, 2007.

Holt, Michael. The Fate of Their Country: Politicians, Slavery Extension, and the Coming of the Civil War. First, Hill and Wang, 2005.

Foner, Eric. Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction. Illustrated, Vintage, 2006.

Jones, Martha. Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America (Studies in Legal History). Cambridge UP, 2018.

Bois, Du W. E. B., et al. W.E.B. Du Bois: Black Reconstruction (LOA #350): An Essay Toward A History of The Part whichBlack Folk Played in The Attempt to ReconstructDemocracy in America, 1860–1880 (Library of America, 350). Library of America, 2021.

Jay, Bethany, et al. Understanding and Teaching American Slavery (the Harvey Goldberg Series for Understanding and Teaching History). 1st ed., University of Wisconsin Press, 2016.

Daniel R. Biddle, and Murray Dubin. “‘God Is Settleing the Account’: African American Reaction to Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 137, no. 1, Project Muse, 2013, p. 57. https://doi.org/10.5215/pennmaghistbio.137.1.0057.

Subtitle here for the credits modal.

Emancipation Proclamation

27 pages • 54 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Essay Analysis

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Summary and Study Guide

Summary: “the emancipation proclamation”.

Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was issued on January 1, 1863, during the US Civil War. The order declared all enslaved people inside the Confederacy to be free, effective immediately. It promised them protection by the US military, and it invited them to join the Union Army in the fight against the Confederacy. The Emancipation Proclamation was widely celebrated as a major turning point in the movement for abolition, though the Union had no means of enforcing it inside the Confederate states where it applied. Upon its release, the document was published in newspapers and, later, often read aloud by Union soldiers to enslaved people when they were freed. It paved the way for the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery, and for decades after its release, the Emancipation Proclamation was celebrated each January 1 in towns across the nation. This study guide refers to the transcript of the proclamation at the website of the US National Archives .

Content Warning : This guide discusses the enslavement of Black people and the US Civil War.

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,450+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,900+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Lincoln was initially reluctant to make emancipation or abolition an important part of his wartime agenda. Although he personally abhorred slavery and campaigned on an anti-slavery platform, he recognized that he had no constitutional authority to abolish it. In his first inaugural address in March 1861, shortly before the outbreak of the war, he said, “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so” (“ Lincoln’s First Inaugural .” Dickinson.edu). When the Confederate States seceded anyway, Lincoln gradually incorporated emancipation as an important war aim in addition to restoring the Union.

This change occurred across 1861 and 1862. There were the voices of abolitionists who loudly called on the president to emancipate enslaved people, but there was also the practical and legal matter of enslaved people escaping to the Union side—something that began almost immediately and set in motion the legal responses that culminated in the Emancipation Proclamation. Such formerly enslaved people were declared free by the Confiscation Acts of 1861 and 1862, and these acts raised the profile of the emancipation idea. After the passage of the Second Confiscation Act of 1862, for example, Horace Greeley published a strongly worded editorial “The Prayer of Twenty Millions,” calling on the president to use his war powers to emancipate those individuals bound by slavery.

The SuperSummary difference

- 8x more resources than SparkNotes and CliffsNotes combined

- Study Guides you won ' t find anywhere else

- 100+ new titles every month