- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Tough Decisions About Dementia and End-of-Life Care

Readers discuss Sandeep Jauhar’s guest essay about dementia and advance directives.

To the Editor:

Re “ My Father Didn’t Want to Live if He Had Dementia. But Then He Had It ,” by Sandeep Jauhar (Opinion guest essay, Oct. 28):

As a hale elder, about to become 90, I have a terrible fear of getting dementia. I can relate entirely to the way Dr. Jauhar’s father felt in his healthier days, but I think Dr. Jauhar is missing something that his father likely felt, which he may not have articulated in his advance directive.

I suspect that he never wanted to be a burden on his children. That is certainly what underlies my urgency to beseech my children to allow me to die if I get dementia. The thought of the burden that it would impose on those who love me is unbearable.

Please listen to those advance directives. What good does it do to merely exist without the zest and delight of awareness? I think that a father who loved his sons dearly and expressed those early thoughts would bless them for allowing him to die with dignity, as he wished in his sentient days.

Carol Landau-Meyerson Floral Park, N.Y.

Sandeep Jauhar’s essay should make us think more deeply about assessing quality of life. My father, Eugene Lang , a brilliant philanthropist and entrepreneur, developed outward signs of Alzheimer’s in his late 80s. He remained physically strong and healthy otherwise.

He knew he was diminished. “I think I reduced myself from one thing to something else,” he randomly observed one day.

My father never wept or complained of pain. He claimed to be “consciously content” — more genial than before his illness and rarely angry. He couldn’t read a book or remember what happened either long ago or five minutes before, but he could sing, word for word, all the verses of songs he taught me when I was a toddler.

This is how my father lived in the Alzheimer’s stage of his life. Had I described it to him before the disease took hold, he would have suggested that I shoot him; he was very worried about losing his marbles, as he put it. And so I signed the do-not-resuscitate order with confidence that it was what he had wanted.

But as the months went on, I no longer believed that my father’s wishes from a time before he had experienced his life with Alzheimer’s were dispositive.

Dr. Jauhar’s quandary reminded me of all this. My father never suggested that he didn’t wish to live. He continued to appreciate the pleasures of food, music and company. The circumstances of his life — a walker, fractured words, imbalance, confusion, 24-hour nursing assistance — would have horrified him at one time, but they rarely perturbed him in the moment.

I hear you had a good day, I said to him one night. “I didn’t have a good day,” he replied. “I had a damn good day.”

My father died at home in his sleep in 2017 at 98.

Jane Lang Washington

The loss of a beloved parent is wrenching, but I wonder if Dr. Sandeep Jauhar’s deeply felt ambivalence about respecting his father’s advance directive doesn’t reflect his own inability to accept his father’s decline and death rather than ethical qualms.

Since his father had clearly stated his wishes before he became too impaired to review them, it seems both infantilizing and disrespectful for his children to second-guess these desires when he can no longer defend them himself.

Surely the ability to enjoy a mouthful of ice cream is not a meaningful benchmark for continuing the diminished existence his father had clearly feared and rejected?

Jane Zimmerman Palo Alto, Calif.

Advance care planning is inherently problematic given that we cannot predict our future ailments and, importantly, cannot predict how we will feel about our quality of life when we’re afflicted with serious illness. Discussions with loved ones help, and the legal durable power of attorney is important. However, loving families may disagree about what your wishes are.

Dr. Barak Gaster has published a now widely used Advance Directive for Dementia , which addresses life-support choices in the various stages of dementia. Also, End of Life Washington has developed a more flexible and extensive set of Dementia Directives , allowing revocation and changes by the individual affected.

There ultimately comes a time to “let go” for all of us. Because advance directive documents are always nuanced, the deep discussions we have with our loved ones are critical to help them support our wishes at the end.

Jim deMaine Seattle The writer, a former pulmonary and critical care physician, is the author of “Facing Death: Finding Dignity, Hope and Healing at the End.”

Dr. Sandeep Jauhar’s thoughtful analysis of the conundrum facing caretakers of a loved one with Alzheimer’s disease overlooks what, in my book, is the most important consideration: how my loved ones remember me.

My memory of my father, once a powerful intellectual with a commanding presence, is now overlaid by memories of him lashing out in anger and frustration at everyone around him as his condition worsened. Our relationship was always complex, but he left me with indelible sadness when, in his last somewhat lucid moments, he selfishly demanded that I kill him, with no concern for the possible imprisonment I would face.

My earlier memories of him are now buried under the vision of a man slumped in a wheelchair in diapers, looking at me with empty eyes.

I’ve had seven decades of life; a few more months at the end are nothing compared to what I’ve achieved and how I want to be remembered. I want to die with my dignity intact. I want to be remembered as a whole human, not a hollowed shell. I don’t want the last memories of my loved ones to be of me in a diaper, unable to answer the simplest questions.

Craig James Santa Cruz, Calif.

Both my parents made me promise never to let them linger, like so many of their friends. I’m a retired neurologist who has withdrawn support for hundreds of people. My colleagues told me it would be different when it happened to my parents. No, it wasn’t.

When my parents became incapacitated, my mother from a rapidly progressive dementia, my father from multi-organ failure, I kept them comfortable and did nothing more, offering food and water but no tubes. Both died within six weeks of their beginning to fail.

I was at their bedside when they died. Of course, it hurt, but I kept my promise. It was the second best thing I have ever done in my life (marrying my wife was the best).

I realize today that if I gave any gift at all to medicine, it was not in cures for patients. I was no super doc miracle worker. No, my gift was in facing the end of life, facing reality, which meant using the words death, die and dying, and doing what I could do — comfort, relieve pain and be present at the end.

Michael S. Smith Eugene, Ore.

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

108 Dementia Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Dementia is a complex and challenging condition that affects millions of people worldwide. Writing an essay on dementia can be a great way to raise awareness about this condition, explore its causes and symptoms, and discuss potential treatments and care strategies. However, coming up with a unique and engaging topic can sometimes be a daunting task. To help you get started, here are 108 dementia essay topic ideas and examples:

- The impact of dementia on individuals and their families.

- The role of genetics in the development of dementia.

- Exploring the different stages of dementia.

- The ethical considerations surrounding the care of individuals with dementia.

- The importance of early diagnosis and intervention in dementia.

- The challenges faced by caregivers of individuals with dementia.

- The impact of dementia on cognitive functions.

- Investigating the link between dementia and Alzheimer's disease.

- The role of nutrition in preventing or managing dementia.

- The social stigma associated with dementia and its effects on individuals and families.

- The potential benefits of music therapy for individuals with dementia.

- Examining the role of exercise in improving cognitive function in dementia patients.

- Exploring the impact of sleep disturbances on dementia progression.

- The influence of environmental factors on dementia risk.

- Investigating the effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions in managing dementia symptoms.

- The economic burden of dementia on healthcare systems.

- The impact of dementia on the quality of life of individuals and their caregivers.

- The role of technology in supporting individuals with dementia.

- The potential benefits and risks of pharmacological interventions in dementia treatment.

- Examining the relationship between cardiovascular health and dementia risk.

- The impact of dementia on language and communication abilities.

- Exploring the relationship between depression and dementia.

- The importance of person-centered care in dementia management.

- The role of art therapy in improving emotional well-being in individuals with dementia.

- The potential benefits of reminiscence therapy in dementia care.

- Investigating the impact of social isolation on dementia progression.

- The role of occupational therapy in supporting individuals with dementia.

- The impact of dementia on sensory perception.

- Examining the effectiveness of cognitive stimulation therapy in improving cognitive function in individuals with dementia.

- The potential benefits of aromatherapy in managing behavioral symptoms of dementia.

- Investigating the impact of dementia on motor function and mobility.

- The role of spirituality in supporting individuals with dementia.

- The influence of cultural factors on dementia care.

- The impact of dementia on decision-making abilities.

- Exploring the relationship between diabetes and dementia.

- The potential benefits of pet therapy for individuals with dementia.

- Investigating the impact of traumatic brain injury on dementia risk.

- The role of neuroimaging in the early detection of dementia.

- The impact of dementia on sleep patterns and circadian rhythms.

- Examining the relationship between hearing loss and dementia.

- The potential benefits of mindfulness-based interventions in dementia care.

- Investigating the impact of dementia on social relationships and interactions.

- The role of respite care in supporting caregivers of individuals with dementia.

- The impact of dementia on executive functions and problem-solving abilities.

- Exploring the relationship between dementia and visual perception.

- The potential benefits of horticulture therapy in dementia care.

- Investigating the impact of dementia on emotional regulation.

- The role of nutrition in preventing or delaying dementia onset.

- The impact of dementia on the sense of self and identity.

- Examining the relationship between inflammation and dementia.

- The potential benefits of dance therapy for individuals with dementia.

- Investigating the impact of dementia on the sense of smell.

- The role of mindfulness meditation in reducing caregiver stress in dementia.

- The impact of dementia on personality and behavior.

- Exploring the relationship between traumatic childhood experiences and dementia risk.

- The potential benefits of light therapy in managing sleep disturbances in individuals with dementia.

- Investigating the impact of dementia on the ability to recognize faces.

- The role of laughter therapy in improving emotional well-being in individuals with dementia.

- The impact of dementia on the ability to perform daily living activities.

- Examining the relationship between dementia and social inequality.

- The potential benefits of virtual reality interventions in dementia care.

- Investigating the impact of dementia on the ability to navigate and orient in space.

- The role of cognitive rehabilitation in improving cognitive function in individuals with dementia.

- The impact of dementia on the ability to perceive and interpret emotions.

- Exploring the relationship between dementia and substance abuse.

- The potential benefits of animal-assisted therapy in dementia care.

- Investigating the impact of dementia on the ability to recognize objects and symbols.

- The role of humor therapy in improving emotional well-being in individuals with dementia.

- The impact of dementia on the ability to plan and execute complex tasks.

- Examining the relationship between dementia and post-traumatic stress disorder.

- The potential benefits of drama therapy for individuals with dementia.

- Investigating the impact of dementia on the ability to understand and produce language.

- The role of mindfulness-based stress reduction in supporting caregivers of individuals with dementia.

- The impact of dementia on the ability to learn and remember new information.

- Exploring the relationship between dementia and anxiety disorders.

- The potential benefits of creative writing therapy in dementia care.

- Investigating the impact of dementia on the ability to reason and make logical judgments.

- The role of cognitive-behavioral therapy in managing behavioral symptoms of dementia.

- The impact of dementia on the ability to recognize and interpret music.

- Examining the relationship between dementia and personality disorders.

- The potential benefits of art therapy for individuals with dementia.

- Investigating the impact of dementia on the ability to process and understand visual information.

- The role of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in improving emotional well-being in individuals with dementia.

- The impact of dementia on the ability to recognize and interpret non-verbal cues.

- Exploring the relationship between dementia and sleep disorders.

- The potential benefits of poetry therapy in dementia care.

- Investigating the impact of dementia on the ability to problem-solve and make decisions.

- The role of cognitive training in improving cognitive function in individuals with dementia.

- The impact of dementia on the ability to recognize and interpret facial expressions.

- Examining the relationship between dementia and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

- The potential benefits of dance/movement therapy for individuals with dementia.

- Investigating the impact of dementia on the ability to process and understand auditory information.

- The role of acceptance and commitment therapy in improving emotional well-being in individuals with dementia.

- The impact of dementia on the ability to recognize and interpret body language.

- Exploring the relationship between dementia and eating disorders.

- The potential benefits of storytelling therapy in dementia care.

- Investigating the impact of dementia on the ability to focus and sustain attention.

- The role of cognitive reserve in delaying cognitive decline in individuals with dementia.

- The impact of dementia on the ability to recognize and understand emotions in others.

- Examining the relationship between dementia and bipolar disorder.

- The potential benefits of gardening therapy for individuals with dementia.

- Investigating the impact of dementia on the ability to inhibit impulsive behaviors.

- The role of social engagement in promoting cognitive health in individuals with dementia.

- The impact of dementia on the ability to recognize and interpret humor.

- Exploring the relationship between dementia and schizophrenia.

- The potential benefits of pet therapy for individuals with advanced dementia.

- Investigating the impact of dementia on the ability to switch between tasks and mental states.

- The role of cognitive enhancers in improving cognitive function in individuals with dementia.

Remember, these topics are just a starting point, and you can modify or combine them to suit your interests and research goals. Whether you choose to explore the biological, psychological, social, or environmental aspects of dementia, writing an essay on this topic can contribute to the understanding and improvement of dementia care and support.

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

131 Dementia Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best dementia topic ideas & essay examples, 💡 interesting topics to write about dementia, ⭐ good research topics about dementia, 📝 simple & easy dementia essay titles, ❓ research questions about dementia.

- Care For a Client Suffering From Moderate Dementia One of the problems may be connected to hearing; in this case, it is recommended to arrange clients in positions closer to the caregiver to enhance their ability to hear and follow the narration of […]

- Caring for Clients With Dementia These include Alzheimer’s disease, which is the most common, followed by vascular dementia and dementia, with Lewy bodies as the least common of the three. We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts 808 writers online Learn More

- Care of the Elderly With Dementia When speaking of the ethical issue of autonomy and restraints, it is vital to recognize how Deontology emphasizes respect and support of autonomy when it is the right decision to make.

- The Frontal Lobe and the Impact of Dementia on It When discussing the frontal lobe, it is essential to mention the prefrontal cortex, which is the front part of the frontal lobe.

- Dementia: Non-Drug and Pharmacological Treatment The problem of dementia remains relevant in modern times, and the issue is especially acute in nursing homes. Accordingly, the following organizations should monitor this issue to improve the non-drug and pharmacological treatment of dementia […]

- Dementia in Older Adults: Effects and Prevention As a result, the research questions for the topic of dementia are as follows: How does the body deteriorate with dementia, and how strong can these changes be for the person diagnosed with dementia?

- Therapeutic Dogs, Dementia, Alzheimer’s and Fluid Intelligence It is worth noting that with dementia, the patient has a speech disorder and a personality change in the early stages of the pathology.

- The Alzheimer’s Association Dementia Care Practice Therefore, achieving the philosophy and recommendations of the association is a shared responsibility between doctors, patients, and caregivers. Ultimately, CAPD tests the functionalities of the patient ranging from the psychomotor activities, perceptions, awareness, and orientations, […]

- Dementia, Alzheimer, and Delirium in an Elderly Woman Additionally, she struggles with identifying the appropriate words to use in dialogue and changes the topic. Timing: While in the middle of conversations and public places like supermarkets.

- Diagnosis of Dementia by Machine Learning Methods in Epidemiological Studies Therefore, epidemiological studies directly impact the diagnosis, prognosis, and clinical treatment by presenting medical practitioners with relevant data on the course, presentation, and treatment of an illness.

- The Clock Drawing Test: Dementia Diagnosis Firstly, one should draw attention to the fact that the diagnosis of dementia was made in 2011, and the patient did not experience any evident symptoms of the condition for the next three years.

- Non- and Pharmacological Dementia Care Methods The analysis of the importance of non-pharmacological versus pharmacological methods in providing care for individuals living with dementia formulates the objectives of the health policy.

- Pharmacological Methods to Provide Care to Dementia Patients The aim of this paper is to discuss the non-pharmacological and pharmacological methods of providing care to dementia patients in nursing homes.

- Toxic Environmental Factors and Development of Dementia As a result, at the moment, the study of the influence of environmental particles on the development of diseases in humans is relevant.

- Managing Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease The PICOT question is “In the care of Alzheimer’s and dementia patients, does integrated community-based care as compared to being in a long-term care facility improve outcome throughout the remainder of their lives”.

- Nursing Physical Assessment of Dementia Patient As a nurse, I must care for the patient and provide patient education to the wife and his close relatives. It would help him forget his worries and trigger the brain to function.

- Therapy Approaches to Aphasia and Dementia Aphasia also illustrates various emotional and social impacts, with people facing these issues, and their families, describing the experience as a journey.

- Health Care Within Aging White Veterans With Dementia Since this condition is heavily linked with damage to the brain, these people should be addressed in a friendly manner to avoid misunderstanding.

- Person-Centered Strategy of Diabetes and Dementia Care The population of focus for this study will be Afro-American women aged between sixty and ninety who have diabetes of the second type and dementia or are likely to develop dementia in the future.

- Therapy of Dementia Elderly People The aging process is characterized by a progressive decrease in the functionality of all vital organs, as a result of which elderly patients are more sensitive to both therapeutic and side effects of drugs taken.

- Analysis of Dementia Treatment Cognitive, biographical pieces of training contribute to the tone of memory and intelligence. Furthermore, using these types of therapies will contribute to health education and a decrease in hospitalization.

- Delirium, Dementia and Immobility Disorders The issues of the inability of patients to function properly, the difficulties of identifying the causes of the symptoms and their relation to the disorder, and insufficient research influence the situation in general.

- Frontotemporal Dementia vs. Alzheimer’s Disease in a Patient Moreover, Alzheimer’s disease affects hypertrophies in the hippocampus as the initial part is involved in the brain’s memory areas and spatial orientation.

- A Report on Assessing Aged Patients With Dementia Since assessment forms the main part of treatment and care of patients with dementia, this report gives several assessment tools that could be used in finding the degree of pain, depression and ability to feed […]

- Dementia: Relaxing Music at Mealtime in Nursing Homes Agitated Patients To reinforce the evidence in support of this modality, and supplementing work carried out by Goddaer and Abraham, the present study scrutinizes the relationship between agitation and soothing music in an assembly of aged residents […]

- Dementia in Residential Aged Care Setting Dementia is a health condition which is defined by Bidewell & Chang, as the progressive decline in cognitive function or, simply, the worsening of a person’s ability to process thought.

- Planning Care Delivery in Dementia According to Chinn and Kramer, the failure to address the requirements of each phase undermines the quality of care. The care planning process begins with the assessment of the client’s needs and preferences.

- Dementia: How Individuals Cope With Condition In most cases, individuals living with dementia find it difficult to successfully cope with the situation mainly because they lose their autonomy and are forced to depend on their relatives and friends.

- Urinary Tract Infections and Dementia Management Importance Reporting the History of Dementia Many patients residing in hospitals after being diagnosed with dementia are, usually, very vulnerable to other infections such as pneumonia and UTI. These illnesses take advantage of the weak immunity in the bodies of the patients since most of them are 81 years and above (Fortinash & Holoday-Worret, 2012). […]

- Management of Dementia Condition Dementia is one of the most common disorders in society that is associated with the loss of cognitive ability in aged adults.

- Dementia and Memory Retention Art therapy is an effective intervention in the management of dementia because it stimulates reminiscence and enhances memory retention among patients with dementia.

- The Middle Range Theory and Care to Patients Suffering From Dementia This paper applies the Lazarus and Folkman Stress and Coping Theory to a family providing health support to a family member by the name Martin. From the exercise, I learned that the family members found […]

- Inter-Professional Healthcare Collaboration: 72-Year-Old Dementia Patient The conversational difficulties in Loretta were caused by the decline of the mental processes essential to the communicative functions, including the functions of recognition and usage of language signs.

- Human Disorders: Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia The brain shows notable changes in Alzheimer’s disease notably, development of tangles in deep areas of the brain and also formation of plagues in other areas.

- Family Theory Use With Dementia The theories of the family include the historical theory, the stress theory, the functional-structural theory, and of course the attachment theory.

- Neurological Disorders and Management of TIA, CVA, Delirium and Dementia In the course of the diagnostic it is advisable to handle the patients with care as some patients tend to be bluntly combative or highly agitated and thus may require the use of chemical restraints.

- The Causes Dementia in Older Adults The purpose of this report is to investigate the causes of dementia and explore the role of a mental health nurse in helping patients to manage the condition.

- Pharmacotherapy for Dementia The prevalence of the disease is yet relatively low but is projected to grow, at least in the United States. The individual set of symptoms usually is the basis for the prescription of drug therapy.

- Mental Health Nursing: Dementia Statistics relating to dementia, as a mental health issue, suggest that there will be an increase in the number of patients diagnosed with the disease as more people seek help for their mental health issues […]

- Vulnerable Population: Elderly With Dementia The purpose of this paper is to describe the ways of supporting older people with dementia with the use of several strategies.

- Changes in the Brain: Types of Dementia According to Cavanaugh and Blanchard-Fields, dementia is a “family of disorders” that involves behavioral and cognitive deficits due to permanent adverse changes to the brain structure and its functioning.

- Dementia: Disease Analysis and Treatment Strategies The purpose of this paper is to research this mental condition and present evidence-based ideas that different professionals can utilize to meet the changing health demands of more patients.

- Alcoholic Dementia and the Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome However, this situation can be problematic because of the nature of the two conditions as well as their interactions. As such, medical practitioners struggle to prescribe treatments that are appropriate to the patient’s situation.

- Dementia in Survivors of Ischemic or Hemorrhagic Stroke The incidence of stroke is the highest in older adults, and this condition is also among the leading causes of long-term disability in the country.

- Elderly Kit Business Plan for Dementia in the UAE The research of the situation has opened an opportunity to think about a product that could improve the quality of life of people with dementia in the UAE.

- Frontotemporal Dementia: Causes and Etymology These findings demonstrate that the enhanced tendency to develop Frontotemporal Dementia in these people is not due to a shared environment but to shared genetic material.”One of the major criteria used for distinguishing frontal variant […]

- Reminiscing Group Therapy for Dementia Patients The elderly population which is increasing rapidly due to the rise in longevity is a group that requires plenty of attention by way of therapy and interventions for their several problems of health and disability. […]

- Dementia: Non-Pharmacologic Interventions Inappropriate behaviors in any disease are very common and in dementia different behaviors are common as in this disease memory function involves that’s why patient behaves abnormally.

- Dementia: Ethical Dilemmas Opting to withdraw the tube may lead to the physiological deprivation of the patient and as a result, the worst-case scenario is the death of the patient.

- Geriatric Dementia, Delirium, and Depression I talked to the patient’s daughter to get additional information about the patient’s medical history and symptoms. In the future, I will consider more therapies and lifestyle changes to offer to the patient.

- Dementia, Delirium, and Depression in Older Adults The comparison is no pharmacological treatment or placebo to exclude the use of other medications, and the outcome is the reduction of delirium severity.

- “Knowing Residents With Dementia” by Kasin and Kautz The research works to eliminate all of the unique aspects of the environment in order to apply the results to the largest possible number of subjects and experiments.

- Dementia in Elderly Population While the condition is common for people over 65, dementia is not a part of the aging process. The drugs of dementia symptoms are expensive and are often reported as a source of financial hardships […]

- Diagnosing Neurological Disorders: Dementia The needs of patients with memory issues are quite difficult to address due to the increase in the levels of stress experienced by both a patient and their family members.

- Dementia, Delirium, and Depression in Frail Elders The patient’s daughter should be educated about the necessity of contact with the patient and possible mobility and other aids to help her with ADL.

- Elderly Dementia: Holistic Approaches to Memory Care The CMAI is a nursing-rated questionnaire that evaluates the recurrence of agitation in residents with dementia. Since the research focuses on agitation, the CMAI was utilized to evaluate the occurrence of agitation at baseline.

- Music Intervention’s Effect on Falls in a Dementia Unit That is why the authors investigate the issue of the relation between music and dementia in order to find the best solution to the existing problem.

- Dementia, Aging, Gerontology: Theories and Care Proponents of the theory, Elaine Cumming and William Henry take the psychosocial perspective in explaining the unhealthy collective relationships the aging person’s experience in the latest phases of their lives.

- Down Syndrome and Dementia: Theories and Treatment The genetic material in the chromosome 21 is responsible for the development of the disorder, and its symptoms appear at the infantry stage of development.

- Age Ailment: Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease It is a time for one to clean the mind and take time to do what matters most in life. With an increased level of technological advancements, a digital sabbatical is mandatory to lower the […]

- Dementia Life Expectancy: Developed vs. Developing Countries Analysis of Economic Aspects Influencing the Lifespan of People with Dementia in Developing and Developed Countries On the one hand, the previously discussed studies point to the direct influence of age on life of people […]

- Dementia and Its Connection With Memory Loss

- Behavioral and Psychiatric Symptoms of Dementia and Rate of Decline in Alzheimer’s Disease

- Altered High-Density Lipoprotein Composition in Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia

- Children With Dementia and Parkinson’s Disease

- Early Dementia, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease Pathology

- Determining Modifiable Risk Factors of Dementia

- Accountable Practitioner Consent and Application to Practice Dementia and Ability to Give Informed Consent

- Burden Among Family Caregivers of Dementia in the Oldest-Old: An Exploratory Study

- Learning Language and Acoustic Models for Identifying Alzheimer’s Dementia From Speech

- Music Therapy and Dementia

- Depression and Missed Work Among Informal Caregivers of Older Individuals With Dementia

- Lifestyle and Dietary Factors Associated With Dementia Status in the Elderly Aged 65 and Older

- Cognitive and Neuropsychiatric Manifestations of COVID-19 and Effects on Elderly Individuals With Dementia

- Acoustic and Language-Based Deep Learning Approaches for Alzheimer’s Dementia Detection From Spontaneous Speech

- Links Between Adiponectin and Dementia: From Risk Factors to Pathophysiology

- Dementia and Its Effects on Society

- Anger Management Therapy for Dementia Patients

- Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment of Dementia

- Amidated and Ibuprofen-Conjugated Kyotorphins and Neuronal Rescue and Memory Recovery in Cerebral Hypoperfusion Dementia Model

- Dementia and Its Effects on Mental Health

- Difference Between Dementia, Delirium and Alzheimer’s

- Enable Rights and Choices of Individuals With Dementia

- Big Data and Dementia: Charting the Route-Ahead for Research, Ethics, and Policy

- Depression: Psychology and Subsequent Vascular Dementia

- Alzheimer’s Disease for Dementia With Lewy Bodies

- Dementia Care Pathway-People With Learning Disability

- Dementia and the Different Parts of the Brain Affected

- Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion in Dementia Care

- Background Information About Dementia and Home Care Services

- Cognitive Stimulation and Cognitive and Functional Decline in Alzheimer’s Disease: The Cache County Dementia Progression Study

- Caring for Patients With Dementia

- Affective and Engagement Issues in the Conception and Assessment of a Robot-Assisted Psychomotor Therapy for Persons With Dementia

- Dementia and Its Effect on the Function of the Brain

- Anti-neurotrophic Effects From Autoantibodies in Adult Diabetes Having Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma or Dementia

- Association Between Cortical Superficial Siderosis and Dementia in Patients With Cognitive Impairment: A Meta-Analysis

- Nutritional Status, Oxidative Stress, and Dementia: The Role of Selenium in Alzheimer’s Disease

- Body Weight Variability Increases Dementia Risk Among Older Adults: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study

- Caring for Persons Living With Dementia During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Biomarkers for Dementia, Fatigue, and Depression in Parkinson’s Disease

- Dementia and Evidence-Based Practice

- What Are Antipsychotic Drugs, and Why Are They Used on Dementia Patients?

- What Are the Nurses’ Experiences in Caring for Dementia Patients With Challenging Behavior?

- What Causes Juvenile Dementia?

- Where Would You Turn for Help for Dementia Care?

- How Does Art Therapy Affect a Patient With Dementia?

- How Does Dementia Onset in Parents Influence Unmarried Adult Children’s Wealth?

- How Exercise Delays Onset of Dementia in Alzheimer’s Patients?

- Can Cognitive Training Slow Down the Progression of Dementia?

- Can Doll Therapy Preserve or Promote Attachment in People With Dementia?

- Can Medication Alter the Course of Dementia?

- Can Mobile Technology Help Prevent the Burden of Dementia in Low- And Mid-Income Countries?

- Adult ADHD: Risk Factor for Dementia or Phenotypic Mimic?

- Are Anticholinergic Medications Associated With Increased Risk of Dementia and Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia?

- Dementia: How and Whom Does It Affect?

- Healthy Aging and Dementia: Two Roads Diverging in Midlife?

- Informal and Formal Care: Substitutes or Complements in Care for People With Dementia?

- Vascular Dementia: Are There Any Differences From Vascular Aging?

- Nitrendipine and Dementia: Forgotten Positive Facts?

- What Are the First Signs of Having Dementia?

- What Are the Five Types of Dementia?

- What Does Dementia Do to a Person?

- Do People With Dementia Know They Have It?

- Does a Person With Dementia Know They Are Confused?

- Does Dementia Run in Families?

- What Is the Leading Cause of Dementia?

- Can a Person Recover From Dementia?

- How Long Do Dementia Patients Live?

- Is There a Way to Prevent Dementia?

- What Vitamins Help Prevent Dementia?

- Does Lack Sleep Cause Dementia?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, March 2). 131 Dementia Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/dementia-essay-topics/

"131 Dementia Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 2 Mar. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/dementia-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '131 Dementia Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 2 March.

IvyPanda . 2024. "131 Dementia Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/dementia-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "131 Dementia Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/dementia-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "131 Dementia Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/dementia-essay-topics/.

- ADHD Essay Ideas

- Caregiver Topics

- Alzheimer’s Disease Research Ideas

- Delirium Essay Ideas

- Alcoholism Essay Titles

- Elder Abuse Ideas

- Nervous System Research Topics

- Parkinson’s Disease Questions

- Nursing Home Questions

- Occupational Therapy Titles

- Gerontology Titles

- Schizophrenia Essay Topics

- Aging Ideas

- Sleep Disorders Research Topics

- Arthritis Titles

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Dementia articles from across Nature Portfolio

Dementia is a syndrome that involves severe loss of cognitive abilities as a result of disease or injury. Dementia caused by traumatic brain injury is often static, whereas dementia caused by neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease, is usually progressive and can eventually be fatal.

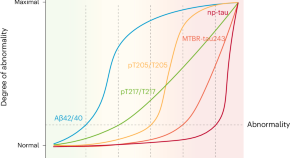

Five biomarkers from one cerebrospinal fluid sample to stage Alzheimer’s disease

Staging Alzheimer’s disease on the basis of the disease’s biological underpinnings might help with stratification and prognostication, both in the clinical setting and in clinical trials. We propose a staging model based on only five biomarkers, which are related to amyloid-β and tau pathologies in different ways and can be measured with a single sample of cerebrospinal fluid.

Related Subjects

- Alzheimer's disease

Latest Research and Reviews

Repurposing non-pharmacological interventions for Alzheimer's disease through link prediction on biomedical literature

- Yongkang Xiao

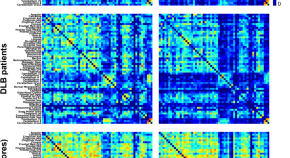

Grey matter networks in women and men with dementia with Lewy bodies

- Annegret Habich

- Javier Oltra

- Daniel Ferreira

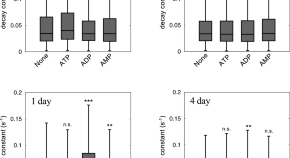

Adenosine triphosphate induces amorphous aggregation of amyloid β by increasing Aβ dynamics

- Masahiro Kuramochi

- Momoka Nakamura

- Kazuaki Yoshimune

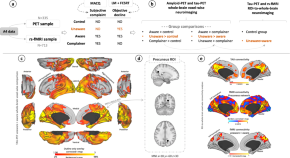

Multi-modal Neuroimaging Phenotyping of Mnemonic Anosognosia in the Aging Brain

Bueichekú et al. use multimodal in vivo neuroimaging to investigate the brain characteristics of individuals presenting unawareness of memory loss who are at risk of Alzheimer’s disease due to age. They find unawareness of memory decline is an early behavioral sign that a person might develop Alzheimer’s disease.

- Elisenda Bueichekú

- Patrizia Vannini

Plasma brain-derived tau is an amyloid-associated neurodegeneration biomarker in Alzheimer’s disease

The authors investigated associations of brain-derived-tau (BD-tau) with Aβ pathology, changes in cognition and MRI signatures. Staging Aβ-pathology according to neurodegeneration, using BD-tau, identifies individuals at risk of near-term cognitive decline and atrophy.

- Fernando Gonzalez-Ortiz

- Bjørn-Eivind Kirsebom

- Kaj Blennow

Influences of amyloid-β and tau on white matter neurite alterations in dementia with Lewy bodies

- Robert I. Reid

- Kejal Kantarci

News and Comment

Neuronal activity drives glymphatic waste clearance.

Two new studies show that clearance of waste, including pathogenic amyloid, through the glymphatic system is driven by synchronized neuronal activity.

Revealing clinical heterogeneity in a large brain bank cohort

Clinical disease trajectories that describe neuropsychiatric symptoms were identified using natural language processing for 3,042 brain donors diagnosed with various neurodegenerative disorders. Trajectories revealed distinct temporal patterns that result in the identification of new clinical subtypes, and a subset of misdiagnosed donors.

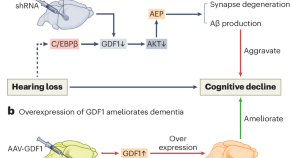

Hearing loss promotes Alzheimer’s disease

Epidemiological studies reveal a correlation between hearing loss and the development and progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but the underlying causal mechanisms remain unclear. A study now provides experimental evidence that hearing loss can promote AD via the growth differentiation factor 1 (GDF1) pathway, which may aid in developing potential AD therapeutic strategies.

- Hong-Bo Zhao

Marker provides 10-year warning of dementia

Changes in plasma levels of specific proteins could predict the development of dementia more than 10 years before clinical diagnosis.

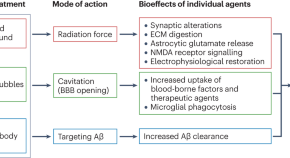

Ultrasound and antibodies — a potentially powerful combination for Alzheimer disease therapy

Success in a trial of low-intensity ultrasound combined with an amyloid-β antibody represents a major stride towards integrating pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches to reduce the amyloid-β load in patients with mild Alzheimer disease. This trial also highlights the potential of therapeutic ultrasound modalities to combat neurodegenerative diseases.

- Jürgen Götz

- Pranesh Padmanabhan

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission

Gill livingston.

a Division of Psychiatry, University College London, London, UK

d Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Jonathan Huntley

Andrew sommerlad.

f National Ageing Research Institute and Academic Unit for Psychiatry of Old Age, University of Melbourne, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, VIC, Australia

Clive Ballard

g University of Exeter, Exeter, UK

Sube Banerjee

h Faculty of Health: Medicine, Dentistry and Human Sciences, University of Plymouth, Plymouth, UK

Carol Brayne

i Cambridge Institute of Public Health, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

Alistair Burns

j Department of Old Age Psychiatry, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

Jiska Cohen-Mansfield

k Department of Health Promotion, School of Public Health, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

l Heczeg Institute on Aging, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

m Minerva Center for Interdisciplinary Study of End of Life, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

Claudia Cooper

Sergi g costafreda.

n Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, Goa Medical College, Goa, India

b Dementia Research Centre, UK Dementia Research Institute, University College London, London, UK

o Institute of Neurology, National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Laura N Gitlin

p Center for Innovative Care in Aging, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MA, USA

Robert Howard

Helen c kales.

r Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, UC Davis School of Medicine, University of California, Sacramento, CA, USA

Mika Kivimäki

c Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University College London, London, UK

Eric B Larson

s Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, WA, USA

Adesola Ogunniyi

t University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria

Vasiliki Orgeta

Karen ritchie.

u Inserm, Unit 1061, Neuropsychiatry: Epidemiological and Clinical Research, La Colombière Hospital, University of Montpellier, Montpellier, France

v Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

Kenneth Rockwood

w Centre for the Health Care of Elderly People, Geriatric Medicine Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada

Elizabeth L Sampson

e Barnet, Enfield, and Haringey Mental Health Trust, London, UK

Quincy Samus

q Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MA, USA

Lon S Schneider

x Department of Psychiatry and the Behavioural Sciences and Department of Neurology, Keck School of Medicine, Leonard Davis School of Gerontology of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Geir Selbæk

y Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Ageing and Health, Vestfold Hospital Trust, Tønsberg, Norway

z Institute of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

aa Geriatric Department, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway

ab Department Psychosocial and Community Health, School of Nursing, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Naaheed Mukadam

Associated data, executive summary.

The number of older people, including those living with dementia, is rising, as younger age mortality declines. However, the age-specific incidence of dementia has fallen in many countries, probably because of improvements in education, nutrition, health care, and lifestyle changes. Overall, a growing body of evidence supports the nine potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia modelled by the 2017 Lancet Commission on dementia prevention, intervention, and care: less education, hypertension, hearing impairment, smoking, obesity, depression, physical inactivity, diabetes, and low social contact. We now add three more risk factors for dementia with newer, convincing evidence. These factors are excessive alcohol consumption, traumatic brain injury, and air pollution. We have completed new reviews and meta-analyses and incorporated these into an updated 12 risk factor life-course model of dementia prevention. Together the 12 modifiable risk factors account for around 40% of worldwide dementias, which consequently could theoretically be prevented or delayed. The potential for prevention is high and might be higher in low-income and middle-income countries (LMIC) where more dementias occur.

Our new life-course model and evidence synthesis has paramount worldwide policy implications. It is never too early and never too late in the life course for dementia prevention. Early-life (younger than 45 years) risks, such as less education, affect cognitive reserve; midlife (45–65 years), and later-life (older than 65 years) risk factors influence reserve and triggering of neuropathological developments. Culture, poverty, and inequality are key drivers of the need for change. Individuals who are most deprived need these changes the most and will derive the highest benefit.

Policy should prioritise childhood education for all. Public health initiatives minimising head injury and decreasing harmful alcohol drinking could potentially reduce young-onset and later-life dementia. Midlife systolic blood pressure control should aim for 130 mm Hg or lower to delay or prevent dementia. Stopping smoking, even in later life, ameliorates this risk. Passive smoking is a less considered modifiable risk factor for dementia. Many countries have restricted this exposure. Policy makers should expedite improvements in air quality, particularly in areas with high air pollution.

We recommend keeping cognitively, physically, and socially active in midlife and later life although little evidence exists for any single specific activity protecting against dementia. Using hearing aids appears to reduce the excess risk from hearing loss. Sustained exercise in midlife, and possibly later life, protects from dementia, perhaps through decreasing obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk. Depression might be a risk for dementia, but in later life dementia might cause depression. Although behaviour change is difficult and some associations might not be purely causal, individuals have a huge potential to reduce their dementia risk.

In LMIC, not everyone has access to secondary education; high rates of hypertension, obesity, and hearing loss exist, and the prevalence of diabetes and smoking are growing, thus an even greater proportion of dementia is potentially preventable.

Amyloid-β and tau biomarkers indicate risk of progression to Alzheimer's dementia but most people with normal cognition with only these biomarkers never develop the disease. Although accurate diagnosis is important for patients who have impairments and functional concerns and their families, no evidence exists to support pre-symptomatic diagnosis in everyday practice.

Our understanding of dementia aetiology is shifting, with latest description of new pathological causes. In the oldest adults (older than 90 years), in particular, mixed dementia is more common. Blood biomarkers might hold promise for future diagnostic approaches and are more scalable than CSF and brain imaging markers.

Wellbeing is the goal of much of dementia care. People with dementia have complex problems and symptoms in many domains. Interventions should be individualised and consider the person as a whole, as well as their family carers. Evidence is accumulating for the effectiveness, at least in the short term, of psychosocial interventions tailored to the patient's needs, to manage neuropsychiatric symptoms. Evidence-based interventions for carers can reduce depressive and anxiety symptoms over years and be cost-effective.

Keeping people with dementia physically healthy is important for their cognition. People with dementia have more physical health problems than others of the same age but often receive less community health care and find it particularly difficult to access and organise care. People with dementia have more hospital admissions than other older people, including for illnesses that are potentially manageable at home. They have died disproportionately in the COVID-19 epidemic. Hospitalisations are distressing and are associated with poor outcomes and high costs. Health-care professionals should consider dementia in older people without known dementia who have frequent admissions or who develop delirium. Delirium is common in people with dementia and contributes to cognitive decline. In hospital, care including appropriate sensory stimulation, ensuring fluid intake, and avoiding infections might reduce delirium incidence.

Key messages

- • New evidence supports adding three modifiable risk factors—excessive alcohol consumption, head injury, and air pollution—to our 2017 Lancet Commission on dementia prevention, intervention, and care life-course model of nine factors (less education, hypertension, hearing impairment, smoking, obesity, depression, physical inactivity, diabetes, and infrequent social contact).

- • Modifying 12 risk factors might prevent or delay up to 40% of dementias.

- • Prevention is about policy and individuals. Contributions to the risk and mitigation of dementia begin early and continue throughout life, so it is never too early or too late. These actions require both public health programmes and individually tailored interventions. In addition to population strategies, policy should address high-risk groups to increase social, cognitive, and physical activity; and vascular health.

- • Aim to maintain systolic BP of 130 mm Hg or less in midlife from around age 40 years (antihypertensive treatment for hypertension is the only known effective preventive medication for dementia).

- • Encourage use of hearing aids for hearing loss and reduce hearing loss by protection of ears from excessive noise exposure.

- • Reduce exposure to air pollution and second-hand tobacco smoke.

- • Prevent head injury.

- • Limit alcohol use, as alcohol misuse and drinking more than 21 units weekly increase the risk of dementia.

- • Avoid smoking uptake and support smoking cessation to stop smoking, as this reduces the risk of dementia even in later life.

- • Provide all children with primary and secondary education.

- • Reduce obesity and the linked condition of diabetes. Sustain midlife, and possibly later life physical activity.

- • Addressing other putative risk factors for dementia, like sleep, through lifestyle interventions, will improve general health.

- • Many risk factors cluster around inequalities, which occur particularly in Black, Asian, and minority ethnic groups and in vulnerable populations. Tackling these factors will involve not only health promotion but also societal action to improve the circumstances in which people live their lives. Examples include creating environments that have physical activity as a norm, reducing the population profile of blood pressure rising with age through better patterns of nutrition, and reducing potential excessive noise exposure.

- • Dementia is rising more in low-income and middle-income countries (LMIC) than in high-income countries, because of population ageing and higher frequency of potentially modifiable risk factors. Preventative interventions might yield the largest dementia reductions in LMIC.

For those with dementia, recommendations are:

- • Post-diagnostic care for people with dementia should address physical and mental health, social care, and support. Most people with dementia have other illnesses and might struggle to look after their health and this might result in potentially preventable hospitalisations.

- • Specific multicomponent interventions decrease neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with dementia and are the treatments of choice. Psychotropic drugs are often ineffective and might have severe adverse effects.

- • Specific interventions for family carers have long-lasting effects on depression and anxiety symptoms, increase quality of life, are cost-effective and might save money.

Acting now on dementia prevention, intervention, and care will vastly improve living and dying for individuals with dementia and their families, and thus society.

Introduction

Worldwide around 50 million people live with dementia, and this number is projected to increase to 152 million by 2050, 1 rising particularly in low-income and middle-income countries (LMIC) where around two-thirds of people with dementia live. 1 Dementia affects individuals, their families, and the economy, with global costs estimated at about US$1 trillion annually. 1

We reconvened the 2017 Lancet Commission on dementia prevention, intervention, and care 2 to identify the evidence for advances likely to have the greatest impact since our 2017 paper and build on its work. Our interdisciplinary, international group of experts presented, debated, and agreed on the best available evidence. We adopted a triangulation framework evaluating the consistency of evidence from different lines of research and used that as the basis to evaluate evidence. We have summarised best evidence using, where possible, good- quality systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or individual studies, where these add important knowledge to the field. We performed systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses where needed to generate new evidence for our analysis of potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia. Within this framework, we present a narrative synthesis of evidence including systematic reviews and meta-analyses and explain its balance, strengths, and limitations. We evaluated new evidence on dementia risk in LMIC; risks and protective factors for dementia; detection of Alzheimer's disease; multimorbidity in dementia; and interventions for people affected by dementia.

Nearly all the evidence is from studies in high-income countries (HIC), so risks might differ in other countries and interventions might require modification for different cultures and environments. This notion also underpins the critical need to understand the dementias related to life-course disadvantage—whether in HICs or LMICs.

Our understanding of dementia aetiology is shifting. A consensus group, for example, has described hippocampal sclerosis associated with TDP-43 proteinopathy, as limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) dementia, usually found in people older than 80 years, progressing more slowly than Alzheimer's disease, detectable at post-mortem, often mimicking or comorbid with Alzheimer's disease. 3 This situation reflects increasing attention as to how clinical syndromes are and are not related to particular underlying pathologies and how this might change across age. More work is needed, however, before LATE can be used as a valid clinical diagnosis.

The fastest growing demographic group in HIC is the oldest adults, those aged over 90 years. Thus a unique opportunity exists to focus on both human biology, in this previously rare population, as well as on meeting their needs and promoting their wellbeing.

Prevention of dementia

The number of people with dementia is rising. Predictions about future trends in dementia prevalence vary depending on the underlying assumptions and geographical region, but generally suggest substantial increases in overall prevalence related to an ageing population. For example, according to the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study, the global age-standardised prevalence of dementia between 1990 and 2016 was relatively stable, but with an ageing and bigger population the number of people with dementia has more than doubled since 1990. 4

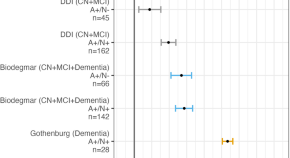

However, in many HIC such as the USA, the UK, and France, age-specific incidence rates are lower in more recent cohorts compared with cohorts from previous decades collected using similar methods and target populations 5 ( figure 1 ) and the age-specific incidence of dementia appears to decrease. 6 All-cause dementia incidence is lower in people born more recently, 7 probably due to educational, socio-economic, health care, and lifestyle changes. 2 , 5 However, in these countries increasing obesity and diabetes and declining physical activity might reverse this trajectory. 8 , 9 In contrast, age-specific dementia prevalence in Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan looks as if it is increasing, as is Alzheimer's in LMIC, although whether diagnostic methods are always the same in comparison studies is unclear. 5 , 6 , 7

Incidence rate ratio comparing new cohorts to old cohorts from five studies of dementia incidence 5

IIDP Project in USA and Nigeria, Bordeaux study in France, and Rotterdam study in the Netherlands adjusted for age. Framingham Heart Study, USA, adjusted for age and sex. CFAS in the UK adjusted for age, sex, area, and deprivation. However, age-specific dementia prevalence is increasing in some other countries. IID=Indianapolis–Ibadan Dementia. CFAS=Cognitive Function and Ageing Study. Adapted from Wu et al, 5 by permission of Springer Nature.

Modelling of the UK change suggests a 57% increase in the number of people with dementia from 2016 to 2040, 70% of that expected if age-specific incidence rates remained steady, 10 such that by 2040 there will be 1·2 million UK people with dementia. Models also suggest that there will be future increases both in the number of individuals who are independent and those with complex care needs. 6

In our first report, the 2017 Commission described a life-course model for potentially modifiable risks for dementia. 2 Life course is important when considering risk, for example, obesity and hypertension in midlife predict future dementia, but both weight and blood pressure usually fall in later life in those with or developing dementia, 9 so lower weight and blood pressure in later life might signify illness, not an absence of risk. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 We consider evidence on other potential risk factors and incorporate those with good quality evidence in our model.

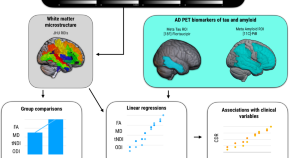

Figure 2 summarises possible mechanisms of protection from dementia, some of which involve increasing or maintaining cognitive reserve despite pathology and neuropathological damage. There are different terms describing the observed differential susceptibility to age-related and disease-related changes and these are not used consistently. 15 , 16 A consensus paper defines reserve as a concept accounting for the difference between an individual's clinical picture and their neuropathology. It, divides the concept further into neurobiological brain reserve (eg, numbers of neurones and synapses at a given timepoint), brain maintenance (as neurobiological capital at any timepoint, based on genetics or lifestyle reducing brain changes and pathology development over time) and cognitive reserve as adaptability enabling preservation of cognition or everyday functioning in spite of brain pathology. 15 Cognitive reserve is changeable and quantifying it uses proxy measures such as education, occupational complexity, leisure activity, residual approaches (the variance of cognition not explained by demographic variables and brain measures), or identification of functional networks that might underlie such reserve. 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20

Possible brain mechanisms for enhancing or maintaining cognitive reserve and risk reduction of potentially modifiable risk factors in dementia

Early-life factors, such as less education, affect the resulting cognitive reserve. Midlife and old-age risk factors influence age-related cognitive decline and triggering of neuropathological developments. Consistent with the hypothesis of cognitive reserve is that older women are more likely to develop dementia than men of the same age, probably partly because on average older women have had less education than older men. Cognitive reserve mechanisms might include preserved metabolism or increased connectivity in temporal and frontal brain areas. 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 People in otherwise good physical health can sustain a higher burden of neuropathology without cognitive impairment. 22 Culture, poverty, and inequality are important obstacles to, and drivers of, the need for change to cognitive reserve. Those who are most deprived need these changes the most and will derive the highest benefit from them.

Smoking increases air particulate matter, and has vascular and toxic effects. 23 Similarly air pollution might act via vascular mechanisms. 24 Exercise might reduce weight and diabetes risk, improve cardiovascular function, decrease glutamine, or enhance hippocampal neurogenesis. 25 Higher HDL cholesterol might protect against vascular risk and inflammation accompanying amyloid-β (Aβ) pathology in mild cognitive impairment. 26

Dementia in LMIC

Numbers of people with dementia in LMIC are rising faster than in HIC because of increases in life expectancy and greater risk factor burden. We previously calculated that nine potentially modifiable risk factors together are associated with 35% of the population attributable fraction (PAFs) of dementia worldwide: less education, high blood pressure, obesity, hearing loss, depression, diabetes, physical inactivity, smoking, and social isolation, assuming causation. 2 Most research data for this calculation came from HIC and there is a relative absence of specific evidence of the impact of risk factors on dementia risk in LMIC, particularly from Africa and Latin America. 27

Calculations considering country-specific prevalence of the nine potentially modifiable risk factors indicate PAF of 40% in China, 41% in India and 56% in Latin America with the potential for these numbers to be even higher depending on which estimates of risk factor frequency are used. 28 , 29 Therefore a higher potential for dementia prevention exists in these countries than in global estimates that use data predominantly from HIC. If not currently in place, national policies addressing access to education, causes and management of high blood pressure, causes and treatment of hearing loss, socio-economic and commercial drivers of obesity, could be implemented to reduce risk in many countries. The higher social contact observed in the three LMIC regions provides potential insights for HIC on how to influence this risk factor for dementia. 30 We could not consider other risk factors such as poor health in pregnancy of malnourished mothers, difficult births, early life malnutrition, survival with heavy infection burdens alongside malaria and HIV, all of which might add to the risks in LMIC.

Diabetes is very common and cigarette smoking is rising in China while falling in most HIC. 31 A meta-analysis found variation of the rates of dementia within China, with a higher prevalence in the north and lower prevalence in central China, estimating 9·5 million people are living with dementia, whereas a slightly later synthesis estimated a higher prevalence of around 11 million. 30 , 32 These data highlight the need for more focused work in LMIC for more accurate estimates of risk and interventions tailored to each setting.

Specific potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia

Risk factors in early life (education), midlife (hypertension, obesity, hearing loss, traumatic brain injury, and alcohol misuse) and later life (smoking, depression, physical inactivity, social isolation, diabetes, and air pollution) can contribute to increased dementia risk ( table 1 ). Good evidence exists for all these risk factors although some late-life factors, such as depression, possibly have a bidirectional impact and are also part of the dementia prodrome. 33 , 34

PAF for 12 dementia risk factors

Data are relative risk (95% CI) or %. Overall weighted PAF=39·7%. PAF=population attributable fraction.

In the next section, we briefly describe relevant newly published and illustrative research studies that add to the 2017 Commission's evidence base, including risks and, for some, mitigation. We have chosen studies that are large and representative of the populations, or smaller studies in areas where very little evidence exists. We discuss them in life-course order and within the life course in the order of magnitude of population attributable factor.

Education and midlife and late-life cognitive stimulation

Education level reached.

Higher childhood education levels and lifelong higher educational attainment reduce dementia risk. 2 , 35 , 36 , 37 New work suggests overall cognitive ability increases, with education, before reaching a plateau in late adolescence, when brain reaches greatest plasticity; with relatively few further gains with education after age 20 years. 38 This suggests cognitive stimulation is more important in early life; much of the apparent later effect might be due to people of higher cognitive function seeking out cognitively stimulating activities and education. 38 It is difficult to separate out the specific impact of education from the effect of overall cognitive ability, 38 , 39 and the specific impact of later-life cognitive activity from lifelong cognitive function and activity. 39 , 40

Cognitive maintenance

One large study in China tried to separate cognitive activity in adulthood from activities for those with more education, by considering activities judged to appeal to people of different levels of education. 40 It found people older than 65 years who read, played games, or bet more frequently had reduced risk of dementia (n=15 882, odds ratio [OR]=0·7, 95% CI 0·6–0·8). The study excluded people developing dementia less than 3 years after baseline to reduce reverse causation.

This finding is consistent with small studies of midlife activities which find them associated with better late-life cognition; so for example, in 205 people aged 30–64 years, followed up until 66–88 years, travel, social outings, playing music, art, physical activity, reading, and speaking a second language, were associated with maintaining cognition, independent of education, occupation, late-life activities, and current structural brain health. 41 Similarly, engaging in intellectual activity as adults, particularly problem solving, for 498 people born in 1936, was associated with cognitive ability acquisition, although not the speed of decline. 42

Cognitive decline

The use it or lose it hypothesis suggests that mental activity, in general, might improve cognitive function. People in more cognitively demanding jobs tend to show less cognitive deterioration before, and sometimes after retirement than those in less demanding jobs. 43 , 44 One systematic review of retirement and cognitive decline found conflicting evidence. 45 Subsequently, a 12-year study of 1658 people found older retirement age but not number of years working, was associated with lower dementia risk. 46 Those retiring because of ill health had lower verbal memory and fluency scores than those retiring for other reasons. 47 Another study found a two-fold increase in episodic memory loss attributable to retirement (n=18 575, mean age 66 years), compared to non-retirees, adjusting for health, age, sex, and wealth. 48 Similarly, in a cohort of 3433 people retiring at a mean age of 61 years, verbal memory declined 38% (95% CI 22–60) faster than before retirement. 44 In countries with younger compared to higher retirement ages, average cognitive performance drops more. 49

Cognitive interventions in normal cognition and mild cognitive impairment

A cognitive intervention or cognition-orientated treatment comprises strategies or skills to improve general or specific areas of cognition. 50 Computerised cognitive training programmes have increasingly replaced tasks that were originally paper-and-pencil format with computer-based tasks for practice and training. 51

Three systematic reviews in the general population found no evidence of generalised cognition improvement from specific cognitive interventions, including computerised cognitive training, although the domain trained might improve. 52 , 53 , 54

A meta-analysis of 17 controlled trials of at least 4 hours of computerised cognitive training, (n=351, control n=335) for mild cognitive impairment, found a moderate effect on general cognition post-training (Hedges' g=0·4, 0·2–0·5); 55 however few high quality studies and no long-term high quality evidence about prevention of dementia currently exists. A meta-analysis of 30 trials of computerised, therapy-based and multimodal interventions for mild cognitive impairment found an effect on activities of daily living (d=0·23) and metacognitive outcomes (d=0·30) compared to control. 56 A third systematic review identified five high quality studies, four group-delivered and one by computer, and concluded the evidence for the effects of cognitive training in mild cognitive impairment was insufficient to draw conclusions. 53 A comprehensive, high quality, systematic overview of meta-analyses of cognitive training in healthy older people, those with mild cognitive impairment and those with dementia, found that most were of low standard, were positive and most reached statistical significance but it was unclear whether results were of clinical value because of the poor standard of the studies and heterogeneity of results ( figure 3 ). 51

Pooled results of meta-analyses investigating objective cognitive outcomes of cognition-oriented treatment in older adults with and without cognitive impairment

K represents the number of primary trials included in the analysis. If a review reported several effect sizes within each outcome domain, a composite was created and k denotes the range of the number of primary trials that contributed to the effect estimate. AMSTAR=A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (max score 16). Adapted from Gavelin et al, 51 by permission of Springer Nature.

In the only randomised controlled trial (RCT) of behavioural activation (221 people) for cognition in amnestic mild cognitive impairment, behavioural activation versus supportive therapy was associated with a decreased 2-year incidence of memory decline (relative risk [RR] 0·12, 0·02–0·74). 57

Hearing impairment

Hearing loss had the highest PAF for dementia in our first report, using a meta-analysis of studies of people with normal baseline cognition and hearing loss present at a threshold of 25 dB, which is the WHO threshold for hearing loss. In the 2017 Commission, we found an RR of 1·9 for dementia in populations followed up over 9–17 years, with the long follow-up times making reverse causation bias unlikely. 2 A subsequent meta-analysis using the same three prospective studies measuring hearing using audiometry at baseline, found an increased risk of dementia (OR 1·3, 95% CI 1·0–1·6) per 10 dB of worsening of hearing loss. 58 A cross-sectional study of 6451 individuals designed to be representative of the US population, with a mean age of 59·4 years, found a decrease in cognition with every 10 dB reduction in hearing, which continued to below the clinical threshold so that subclinical levels of hearing impairment (below 25 dB) were significantly related to lower cognition. 59

Although the aetiology still needs further clarification, a small US prospective cohort study of 194 adults without baseline cognitive impairment, (baseline mean age 54·5 years), and at least two brain MRIs, with a mean of 19 years follow-up, found that midlife hearing impairment measured by audiometry, is associated with steeper temporal lobe volume loss, including in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. 60

Hearing aids

A 25-year prospective study of 3777 people aged 65 years or older found increased dementia incidence in those with self-reported hearing problems except in those using hearing aids. 61 Similarly, a cross–sectional study found hearing loss was only associated with worse cognition in those not using hearing aids. 62 A US nationally representative survey of 2040 people older than 50 years, tested every two years for 18 years, found immediate and delayed recall deteriorated less after initiation of hearing aid use, adjusting for other risk factors. 63 Hearing aid use was the largest factor protecting from decline (regression coefficient β for higher episodic memory 1·53; p<0·001) adjusting for protective and harmful factors. The long follow-up times in these prospective studies suggest hearing aid use is protective, rather than the possibility that those developing dementia are less likely to use hearing aids. Hearing loss might result in cognitive decline through reduced cognitive stimulation.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI)

The International Classification of Disease (ICD) defines mild TBI as concussion and severe TBI as skull fracture, oedema, brain injury or bleed. Single, severe TBI is associated in humans, and mouse models, with widespread hyperphosphorylated tau pathology, and mice with APOE ε4 compared to APOE ε3 allele have more hippocampal hyper-phosphorylated tau after TBI. 64 , 65 TBI is usually caused by car, motorcycle, and bicycle injuries; military exposures; boxing, horse riding, and other recreational sports; firearms; and falls. 66 A nationwide Danish cohort study of nearly 3 million people aged 50 years or older, followed for a mean of 10 years, found an increased dementia (HR 1·2, 95% CI 1·2–1·3) and Alzheimer's disease risk (1·2, 1·1–1·2). 67 Dementia risk was highest in the 6 months after TBI (4·1, 3·8–4·3) and increased with number of injuries in people with TBI (one TBI 1·2, 1·2–1·3; ≥5 TBIs 2·8, 2·1–3·8). Risk was higher for TBI than fractures in other body areas (1·3, 1·3–1·3) and remained elevated after excluding those who developed dementia within 2 years after TBI, to reduce reverse causation bias. 67

Similarly, a Swedish cohort of over 3 million people aged 50 years or older, found TBI increased 1-year dementia risk (OR 3·5, 95% CI 3·2–3·8); and risk remained elevated, albeit attenuated over 30 years (1·3, 1·1–1·4). 68 ICD defined single mild TBI increased the risk of dementia less than severe TBI and multiple TBIs increased the risk further (OR 1·6, 95% CI 1·6–1·7 for single TBI; 2·1, 2·0–2·2 for more severe TBI; and 2·8, 2·5–3·2 for multiple TBI). A nested case control study of early onset clinically diagnosed Alzheimer's disease within an established cohort also found TBI was a risk factor, increasing with number and severity. 69 A stronger risk of dementia was found nearer the time of the TBI, leading to some people with early-onset Alzheimer's disease.