Case Study Summarizer #1 — Free Summaries!

Have you ever thought of how many case studies must a student in medicine or business read in their lifetime? Tens, hundreds, or even thousands! As practice shows, the case study’s content is jam-packed with information and broad descriptions that are unnecessary when conducting a review or simply reading the literature.

We offer a Case Study Summarizer to scan any paper in seconds! You will get some valuable insights about our tool that can help with the most extended case studies in a short time! Moreover, we discuss the definition of the case study, its structure, and its main elements. Let’s begin!

- 🧰 How to Use the Tool?

📋 What Is the Case Study Summarizer?

🧩 case study elements & structure, 🧑🏫 how to summarize a case study.

- ✅ 5 Tool’s Benefits

🖇️ References

🧰 how to use the case summarizer.

Our free case study summarizer is so easy to use! Follow these 4 simple steps:

- Enter the text . Paste the text of the case study in the appropriate field of the tool. Ensure that it does not exceed 15,000 characters.

- Adjust settings . You can choose the number of sentences you want in your summary and decide whether to highlight keywords.

- Press the button . Just click the button, and the results will not keep you waiting!

- Copy the result . Your summary will appear in just a few seconds! All you need to do is just copy it in one click.

Do you still have concerns about using our case study summarizer? Then check out its incredible features:

A case study is typically presented as a report, separated into sections with headings and subheadings. It must contain a description of the issue, an explanation of the relevance of the case, and an analysis with conclusions. It ends with implications and recommendations on how to address the issue.

What Is a Case Study?

A case study is a detailed investigation of one person, group, or event. It aims to learn as much as possible about an individual or a group to generalize the findings on other similar cases. The case study can be employed in various fields, including psychology , medicine , social work, etc.

Here are some case study topics from different professional spheres:

- Medicine : Analysis of the medical and occupational records of a non-smoking individual with lung cancer.

- Business : The decision of Warren Buffett to acquire Precision Castparts Corporation and why that acquisition was a mistake.

- Psychology : The case of Bertha Pappenheim , who suffered from hysteria and contributed to the development of talk therapy to treat mental illness.

Case Study Elements

There are 8 essential elements in any case study. Check the table below to learn more details about each component.

Summarizing is a fundamental skill for everyone since it allows you to distinguish essential information and effectively communicate it to others. In the following paragraphs, we will share a case study summary tutorial.

Executive Summary Case Study

An executive summary is a detailed overview of a report. It saves readers time by summarizing the essential points of the study. It is frequently written to be shared with people who may not have time to read the complete report, for example, CEOs or department heads.

Although the format may vary, the primary elements of an executive summary are as follows:

- An opening statement and some background information .

- The purpose of the report.

- Methodology.

- Summarized and justified recommendations.

How Long Is an Executive Summary?

Your executive summary’s length will vary depending on the text it summarizes. Typically, it takes 10-15% of the full report’s length . Therefore, an executive summary can range from 1 paragraph to 10 pages.

Case Study Summary Guide

Take these 5 steps to write a compelling case study summary:

Step 1 – Read the entire study

Before writing the summary, carefully read the research study from beginning to end.

Step 2 – Highlight the major points

As you read, make notes and underline significant facts, relevant conclusions, and suggested actions.

Step 3 – Divide the document into main sections

Determine what each part of the report is about, and summarize each in a few sentences. You can use the executive summary structure mentioned above to guide your writing.

Step 4 – Be concise

Do not write more than 10% of the length of the original document.

Step 5 – Proofread your summary

Reread your case study summary to ensure it makes sense as an independent piece of writing. Set it aside for a while and look at it with fresh eyes to notice any incoherence and redundant or lacking details.

✒️️ Case Study Summary Example

We have prepared an example of a case study summary for you to see how everything works in practice!

Here is the full report: Akron’s Children’s Hospital: Case Study .

Now, check its summarized version:

Akron Children’s Hospital is a leading pediatric hospital in Northeastern Ohio that faces competition and needs to differentiate itself to attract more patients. To gain insight into the decision-making process of patients' parents, the hospital hired a team of researchers led by Marcus Thomas LLC to conduct business and market analysis.

An observational study was conducted to collect consumer data, including perceptions of the hospital and the criteria used to select it. The problem was that a highly competitive medical industry in Northeastern Ohio resulted in reduced patient volume and financial losses at Akron Children’s Hospital.

The proposed solution was to rethink the hospital’s operations and marketing approach to differentiate it from the competitors and attract more patients. Furthermore, the treatment of certain groups of children had to be improved by increasing the number of specializations available at the hospital.

The organization was recommended to develop an efficient marketing strategy, enhance service delivery, and implement highly innovative medical technologies and procedures.

✅ 5 Benefits of the Case Summarizer You Should Consider

Still in doubt whether our case study summary tool is worth using? Check out its benefits:

- It is time-saving . The online tool is perfect for students in medicine or psychology since it allows for consuming a lot of information in a short time.

- It is easy to use . The interface of our case summarizer is so simple to navigate that even a child can handle it.

- It is unlimited . Try our online summarizer as many times as you need. There are no limitations!

- It is free . You can summarize a case study online in a few minutes without spending money. Such a considerable benefit for prudent students!

- It is accurate . The case summary generator uses essential keywords and phrases to isolate only the most relevant information.

- Executive Summary | USC Libraries

- Case Studies | Carnegie Mellon University

- Writing a Case Study | Monash University

- Guidelines for Writing a Summary | Hunter College

- Executive Summaries | Colorado State University

How to Summarize a Case Study Effectively

Saving time and effort with Notta, starting from today!

There are hundreds of marketing methods today, but a written case study remains a tried and tested practice to attract new customers. A few months ago, I started working on the case studies — and that's when I learned so much about what works — and what doesn't.

By the time a reader decides to take a look at your case study, they're seriously considering your offering. It's the time when the prospect will either engage more or lose their interest completely. But before the reader thinks of looking at the case study, they'll need a short, meaningful summary.

But how to summarize a case study that's short, simple, and informative? I've written over 50+ case studies, and each one has a short summary. In this detailed guide, I'll show you some tried and tested methods of summarizing long documents.

What is a Case Study Summary?

A case study summary is a short recap of a detailed case, interview, or other document. It has all of the same traits as that of a good summary: it's clean, short, straightforward, and flows naturally for the reader. But in the business world, a case study has the job of connecting customers with business, and a great summary also does the same.

A lead decides to look at the case study summary only if they're seriously interested in the products/services you offer. After reading, your reader's reaction will likely come down to this: did the case study summary make the benefits seem necessary or just nice to have?

If it's the latter, your prospects will probably avoid reading the detailed case study and pass on the opportunity. That's why the summary should include the key points and highlights from the case study and showcase to customers that your product or service is a necessity for their business growth.

How to Summarize a Case Study (with Guidelines)

I have recently read a statement: 'An educated client is a secure client.' Business typically boils down to two priorities: creating a useful product and then making people realize how it can help them. Both of these things mainly revolve around customer education, and both require a case study summary to get the job done.

Here, I'll reveal some simple steps that will help you summarize a case study.

Read the Case Study

When it comes to summarizing a case study, think about how effective it will be from the reader's perspective. You can even take notes and formulate an information architecture into proper formatting, headers, and bullet points to manage content better.

Understand the Goal

A business case study, for example, is a detailed document that defines how a business and its product helped a client improve sales. You should apply the same story and approach to write a case study summary — ensuring it sticks in the heart and mind of the reader.

Identify the Main Points

A good case study teaches prospects something — related to your products, services, new features, or how you're different. Think about the main points of the case study and why people should bother to read it. One of the biggest keys to a great summary is to speak to the customers' pain points directly and immediately offer the solution.

Write a Clear Summary

Now, write the way you talk — with clear ideas, concise language, and a welcoming tone. You need to hold onto your reader's attention with appropriate words and interesting facts. My number one tip is to be creative — even if the case study is boring. Here, your ultimate goal is to be engaging and creative — and, that too, within the confines of the industry.

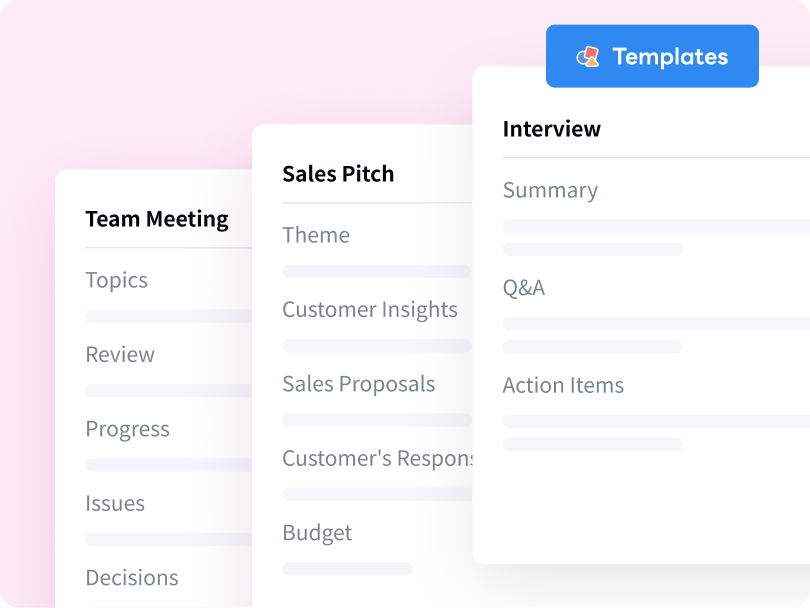

Ready to revolutionize your post-meeting workflow? Give Notta's AI Summary Templates a try today and experience the difference for yourself. Simply select the template that best fits your needs, and watch as Notta transforms your raw notes into polished, concise summaries. Your time is precious – let Notta help you make the most of it.

Read and Revise

When you're done writing, read the summary aloud to yourself. Give it some emotions (if you can and if the topic allows you) while ensuring there is no fluff in the summary.

Depending on the type of case study summary , you might include different elements — but here's a general breakdown of the guidelines that you should keep in mind while summarizing.

Length : A good summary should have everything — from an attention-grabbing headline to a detailed explanation of the product, service, concept, or project. But that doesn't mean it can be a seven-page-long document. You must stick to the important facts and keep it pretty short — a few paragraphs or one page maximum .

Problem & Solution: Next, clearly state the problem (or issue) you want to solve and then briefly explain how the information provided in the case study solves it.

End with CTA: You'll need to tell your readers what to do next. For example, add the contact information if you want them to contact you or add links to more articles so they can continue reading.

Example of a Case Study Summary

Let's take a look at one example of how people summarize case studies. The example below is technically one page but packs a lot of information into it.

Here's an example of how to write an executive summary for a case study .

[Introduction]: The case study explains how the leading eCommerce platform (Company X) improved its customer experience with the digital tool. [Challenge]: Digital presence and customer satisfaction were the two key challenges faced by Company X. [Approach]: With the help of AI and automation, Company X implemented a robust CRM system and even launched a mobile app for user interaction. [Solution]: The approach helped the client improve their sales by 20% — in only three months.

Tips for Summarizing a Case Study

One of my responsibilities as a freelancer is creating case studies and sending them to potential clients. They're busy people, so I include a case study summary at the beginning that briefs the ten pages of detailed information into a few bullet points — the must-knows. Here’s how to write a case study summary — faster and better.

Write Great Hook Lines

Any article, blog, interview, email, or summary with an annoying hook line is going to get sent to spam right away. You should check and make sure the hook line is short enough to be read in seconds and grabs the attention of the reader. The point is to place the important or value-added material at the top of the summary.

Keep Things Scannable

People are busy, and only a few of them have the time to read a summary that's packed with text. If you take some time to think about what case study summaries work best, you'll likely find that the most effective ones are pretty brief. Smart formatting (with a strategic design) can keep the summary short while ensuring it has enough substance.

Automate Tasks with AI

With an AI case study summary tool, you can skip the blank-page stage of the summarizing process. These tools can analyze the content and come up with a short, informative summary — freeing up your time for other work. Notta is one of the popular AI note-taking and summarizing apps out there right now.

Whether you want to summarize interviews or voice memos, Notta Web App can help you with the job. It's particularly helpful if you've case studies in audio or video format: just upload the file, and Notta will generate a transcript and well-structured summary with an overview, key chapters, and action items.

Try Notta - the best online transcription & summarization tool. Transcribe and summarize your conversations and meetings quickly with high accuracy.

Start for Free

How Long Should a Case Study Summary Be?

While the exact length of a case study summary will depend on what you're summarizing, it typically ranges from a few paragraphs (2 or 3) to one single page . For example, if you're writing a customer case study with your storytelling skills, it can go as long as one page. But if you are summarizing an interview for the recruiting team, a paragraph or two would help them understand the candidate's skills.

How to Write a Good Case Study?

Even the most trusted marketers or businesses will tell you how much case studies have boosted their business. It's like a customer review that can get you more business — only if you write it properly. If you're new to writing case studies, here are simple steps to make the process a lot easier.

Start your research: Like anything else you write, you'll need to do proper research for a case study. For example, this includes the target audience, the message you're trying to convey, and the value your case study will provide.

Write the key highlights : A good case study summary is typically short and sweet, so don't defeat the whole purpose by adding unnecessary things. You'll need to include only the key highlights that matter the most to the reader.

Choose the format: While you may feel tempted to use all the space you have — don't. Some empty space around the text keeps the summary look uncluttered and easy to read.

Include a social proof: Reading a case study is like reading a review — but it mainly relies on storytelling. Including social proof in the case study will push leads to book their first call, send an email, or even sign up for a newsletter.

Be honest: The goal of your case study isn't to win over every single person reading it — instead, it's to win over the people who'll be your potential customers. Being honest is the key here.

Key Takeaways

It takes some time and effort to learn how to summarize a case study and condense all the important information into only a few paragraphs. If you don’t have enough time, check out my favorite AI note-taker and summarizer , Notta . It’s pretty easy to use — just upload the case study video, and the AI tool will quickly transcribe and summarize the information.

Chrome Extension

Help Center

vs Otter.ai

vs Fireflies.ai

vs Happy Scribe

vs Sonix.ai

Integrations

Microsoft Teams

Google Meet

Google Drive

Audio to Text Converter

Video to Text Converter

Online Video Converter

Online Audio Converter

Online Vocal Remover

YouTube Video Summarizer

University of Vermont

Tim plante, md mhs, part 5: baseline characteristics in a table 1 for a prospective observational study, what’s the deal with table 1.

Tables describing the baseline characteristics of your analytical sample are ubiquitous in observational epidemiology manuscripts. They are critical to help the reader understand the study population and potential limitations of your analysis. A table characterizing baseline characteristics is so important that it’s typically the first table that appears in any observational epidemiology (or clinical trial) manuscript, so it’s commonly referred to as a “ Table 1 “. Table 1s are critically important because they help the readers understand internal validity of your study. If your study has poor internal validity, then your results and findings aren’t useful.

The details here are specific to prospective observational studies (e.g., cohort studies), but are generalizable to other sorts of studies (e.g., RCTs, case-control studies).

If you are a Stata user, you might be interested into my primer of using Table1_mc to generate a Table 1 .

Guts of a Table 1

There are several variations of the Table 1, here’s how I do it.

COLUMNS : This is your exposure of interest (i.e., dependent variable). This is not the outcome of interest . There’s a few way to divvy up these columns, depending on what sort of data you have:

- Continuous exposure (e.g., baseline LDL-cholesterol level): Cut this up into quantiles. I commonly use tertiles (3 groups) or quartiles (4 groups). People have very, very strong opinions about whether you use tertiles or quartiles. I don’t see much of a fuss in using either. Of note, there usually is no need to transform your data prior to splitting into quantiles. (And, log transforming continuous data that includes values of zero will replace those zeros with missing data!)

- Dichotomous/binary exposure (e.g., prevalent diabetes status as no/0 or yes/1): This is easy, column headers should be 0 or 1. Make sure to use a descriptive column header like “No prevalent diabetes” and “Prevalent diabetes” instead of numbers 0 and 1.

- Ordinal exposure, not too many groups (e.g., never smoker/0, former smoker/1, current smoker/2): This is also easy, column headers should be 0, 1, or 2. Make sure to use descriptive column headers.

- Ordinal exposure, a bunch of groups (e.g., extended Likert scale ranging from super unsatisfied/1 to super satisfied/7): This is a bit tricker. On one hand, there isn’t any real limitation on how wide a table can be in a software package so you could have columns 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ,6 and 7. This is a bit unwieldy for the reader, however. I personally think it’s better to collapse really wide groupings into a few groups. Here, you could collapse all of the negative responses (1, 2 and 3), leave the neutral response as its own category (4), and collapse all of the positive responses (5, 6, and 7). Also use descriptive column headers, but also be sure to describe how you collapsed groups in the footer of the table.

- Nominal exposure, not too many groups (e.g., US Census regions of Northeast, Midwest, South, and West): This is easy, just use the groups. Be thoughtful about using a consistent order of these groups throughout your manuscript.

- Nominal exposure, a bunch of groups (e.g., favorite movie): As with ‘Ordinal data, a bunch of groups’ above, I would collapse these into groups that relate to each other, such as genre of movie.

- (Optional) Additional first column showing “Total” summary statistics. This presents summary statistics for the entire study population as a whole, instead of by quantile or discrete groupings. I don’t see much value in these and typically don’t include them.

- Note: Table1_mc for Stata cannot generate a “missingness” row .

- (Optional, but suggest to avoid) Following P-value column that shows comparisons across rows. These have fallen out of favor for clinical trial Table 1s . I see little value of them for prospective observational studies and also avoid them.

ROWS: These include the N for each column, the range of values for continuous exposures, and baseline values. Note that the data here are from baseline.

- N for each group. Make sure that these Ns add up to the expected N in your analytical population at the bottom of your inclusion flow diagram. If it doesn’t match, you’ve done something wrong.

- (For continuous exposures) Range of values for your quantiles and yes I mean minimum and maximum for each quantile, not IQRs.

- Sociodemographics (age, sex, race, ± income, ± region, ± education level, etc.)

- Anthropometrics (height, weight, waist circumference, BMI, etc.)

- Medical problems as relevant to your study (eg, proportion with hypertension, diabetes, etc.)

- Medical data as relevant to your study (eg, laboratory assays, details with radiological imaging, details from cardiology reports)

- Suggest avoiding the outcome(s) of interest as additional rows. I think that presenting the outcomes in this table is inadequate. I prefer to have a separate table or figure dedicated to the outcome of interest that goes much more in-depth than a Table 1 does. Plus, the outcome isn’t ascertained at baseline in a prospective observational study, and describing the population at baseline is the general purpose of Table 1.

- And for the love of Pete, please make sure that all covariates in your final model appear as rows. If you have a model that adjusts for Epworth Sleepiness Score, for example, make sure that fits in somewhere above.

The first column of your Table 1 will describe each row. The appearance of this row will vary based upon the type of data you have.

- N row – I suggest simply using “N”, though some folks use N (upper case) to designate the entire population and n (lower case) to designate subpopulations, so perhaps you might opt to put “n”.

- Continuous variables (including the row for range) – I suggest a descriptive name and the units. Eg, “Height, cm”

- Dichotomous/binary values – In this example, sex is dichotomous (male vs. female) since that’s how it has historically been collected in NIH studies. For dichotomous variables, you can include either (1) a row for ‘Male’ and a row for ‘Female’, or (2) simply a row for one of the two sexes (eg, just ‘Female’) since the other row will be the other sex.

- Other discrete variables (eg, ordinal or nominal) – In this example, we will consider the nominal variable of Race. I suggest having a leading row that provides description of the following rows (eg, “Race group”) then add two spaces before each following race group so the nominal values for the race groups seem nested under the heading.

- (Optional) Headings for groupings of rows – I like including bold/italicized headings for groupings of data to help keep things organized.

Here’s an example of how I think a blank table should appear:

Table 1 – Here is a descriptive title of your Table 1 followed by an asterix that leads to the footer. I suggest something like “Sociodemographics, anthropometrics, medical problems, and medical data ascertained baseline among [#] participants in [NAME OF STUDY] with [BRIEF INCLUSION CRITERIA] and without [BRIEF EXCLUSION CRITERIA] by [DESCRIPTION OF EXPOSURE LIKE ‘TERTILE OF CRP’ OR ‘PREVALENT DIABETES STATUS’]*”

*Footer of your Table 1. I suggest describing the appearance of the cells, eg “Range is minimum and maximum of the exposure for each quantile. Presented as mean (SD) for normally distributed and median (IQR) for skewed continuous variables. Discrete data are presented as column percents.”

Cell contents

The cell contents varies by type of variable and your goal in this table:

- Normally distributed continuous variables : Mean (SD)

- Non-normally distributed continuous variables : Median (IQR)

- Discrete variables : Present column percentages . Not row percentages. For example we’ll consider “income >$75k” by tertile of CRP. A column percentage would show the % of participants in that specific quantile have an income >$75k. A row percentage would show the percentage of participants with income >$75K who were in that specific tertile.

- Note: Table1_mc in Stata cannot report an ‘n’ with continuous variables.

- Dichotomous variables : Present column percentage plus ‘n’. Example for female sex: “45%, n=244”.

A word on rounding: I think there is little value on including numbers after the decimal place. I suggest aggressively rounding at the decimal for most things. For example, for BMI, I suggest showing “27 (6)” and not “26.7 (7.2)”. For things that are obtained at the decimal place, I strongly recommend reporting at the decimal. For example, BP is always measured as a whole number, so reporting out a tenth place for BP isn’t of much value. For example, systolic BP is measured as 142, 112, and 138 — not 141.8, 111.8 and 138.4. For discrete variables, I always round the proportion/percentage at the decimal, but clarify very small proportions to be “<1%" if there are any in that group, but it would round to zero or "0%" if there are none in that group.

The one exception to my aggressive “round at the decimal place” strategy is variables that are commonly reported past the decimal place, such as many laboratory values. Serum creatinine is commonly reported to the hundredths place (e.g., “0.88”), so report the summary statistic for that value to the hundredths place, like 0.78 (0.30).

- About WordPress

- Get Involved

- WordPress.org

- Documentation

- Learn WordPress

- UVM Blogs Home

- Site Directory

- Content Writing Services

- Get in Touch

How to Write an Executive Summary for a Case Study

Updated February 2022: The first thing you do when faced with any study or report is read the executive summary or overview—right? Then you decide if reading the rest of the material is worth your time. This is why it is so important for you to learn how to write an executive summary for a case study.

The executive summary of your case study serves exactly the same function. If the reader sees nothing beyond this section, they will still walk away with a good understanding of your service.

A great summary might even be enough for a reader to pass the information along to the decision-makers in their organization.

In this post, we’ll discuss what makes a compelling executive summary for case studies, and provide you with 4 examples from leading B2B SaaS companies. This is the third post in a 9-part series on how to write a case study .

Every word counts when writing an executive summary

When thinking about how to write an executive summary for a case study, you need to create 2 or 3 crucial sentences that provide a concise overview of the case study. It must be informative and:

- summarize the story by introducing the customer and their pain points

- explain what your organization did

- highlight the key results, including 1 or 2 statistics that drive home the takeaway message

Write the executive summary first to help you focus the rest of the case study. But don’t be too rigid: in the process of reviewing the interview transcript or writing the main copy, another point or statistic may emerge as having more impact than what you’ve chosen to highlight. Revisit your executive summary after writing the case study to make sure it’s as strong and accurate as possible.

If you need a hand with your SaaS case studies, have a look at our case study writing service .

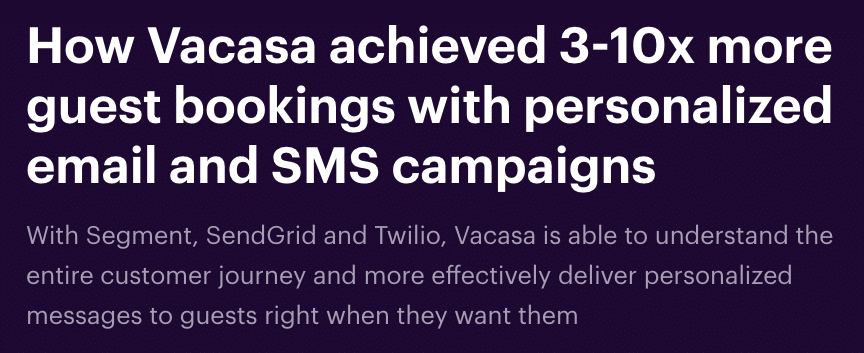

Executive summaries can be short and sweet

This executive summary example from Segment is just a headline followed by a glorified subhead—but it does the trick!

Here’s another great example of a quick, yet helpful executive summary for Plaid’s case study:

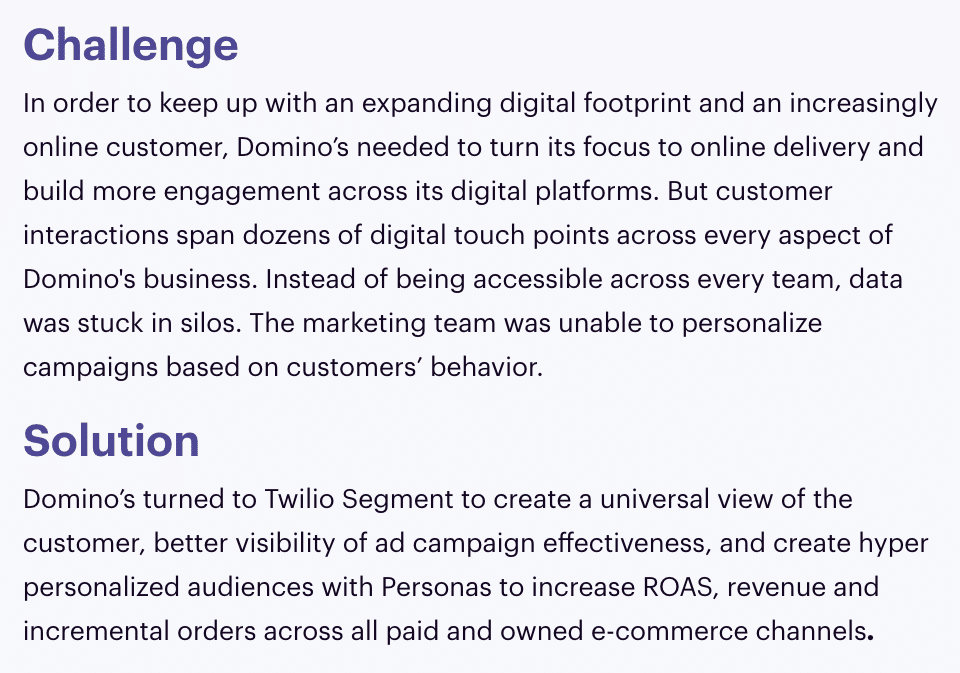

Sometimes you may need a longer executive summary

For complex case studies, you may need a more in-depth executive summary to give readers an overview of the case study.

Here’s a more fleshed-out executive summary from Segment:

It’s a bit lengthy, but it effectively introduces the challenge. This executive summary could be more powerful if it included a section for results.

Sometimes executive summaries miss the mark entirely

This is not an executive summary. It is merely an introduction. We have no idea what the problem or solution is, and there’s nothing to motivate us to read further.

You can do better with your executive summaries

Be precise. Impress the reader with key results. Let them see that you offer solutions that matter.

Get the help you need

As a SaaS company, you need to partner with someone who “gets it”. We are a SaaS content marketing agency that works with high-growth companies like Calendly, ClickUp and WalkMe. Check out our done-for-you case study writing service .

As the founder of Uplift Content, Emily leads her team in creating done-for-you case studies, ebooks and blog posts for high-growth SaaS companies like ClickUp, Calendly and WalkMe. Connect with Emily on Linkedin

Sign up for the Content Huddle newsletter

Learn from Emily’s 17 years of aha moments, mistakes, observations, and insights—and find out how you can apply these lessons to your own marketing efforts.

You can unsubscribe any time. Visit our Terms of Use for information on our privacy practices.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 30 January 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organisation, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating, and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyse the case.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

Unlike quantitative or experimental research, a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

If you find yourself aiming to simultaneously investigate and solve an issue, consider conducting action research . As its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time, and is highly iterative and flexible.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience, or phenomenon.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews, observations, and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data .

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis, with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results , and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyse its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, January 30). Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 15 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/case-studies/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, correlational research | guide, design & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, descriptive research design | definition, methods & examples.

What to Include in a Case Study: Layout, Content & Visuals

Learn what info to include in a business case study and how to structure it for maximum conversion, and see real-life examples and templates.

Dominika Krukowska

9 minute read

Short answer

What to include in a case study?

A successful case study should include the following elements:

- Introduction (what was the problem and how it was solved in 1-2 sentences)

- Client overview

- The problem or challenge

- How they solved their problem (with your solution)

- Customer quotes and testimonials

For a case study to work all critical components must be in place.

Case studies can be gold mines for conversions, but extracting that gold isn't as straightforward as it seems.

What goes into a case study that tells a compelling story and draws your prospects down the conversion funnel?

There are some critical elements that you must include in your case study if you hope to generate conversions.

Yes, you read that right— making a partial case study could very well mean leaving money on the table.

In this post, I’ll share with you the secrets to creating a case study that’ll turn it from ‘blah’ to ‘bingo’.

You’ll learn what you must include in your case study to convert readers into buyers.

Let’s go!

What to include in your case study structure?

Crafting your case study is like writing a gripping novel, filled with characters, conflicts, and resolutions. Each component of your case study serves a unique purpose in narrating the story of how your product or service helps your clients conquer their challenges.

Here are the main chapters of your case study structure:

1. Introduction

Think of the introduction as your story's opening scene. It's your first impression, your initial hook, the gateway to the world you're about to unfold. Here, you aim to spark curiosity and give your reader a taste of the journey ahead.

How to create an introduction slide:

Include a video —this will get 32% more people to interact with your case study .

Create an opening line that instantly hooks your reader —think surprising statistics, bold statements, or intriguing questions.

Introduce the central theme of your case study —what's the big challenge or opportunity at play?

Connect with the reader's pain points to foster engagement right from the start.

Here’s an example of an introduction slide that hooks attention:

2. Company overview

Here, you introduce your main hero—your client. You want to provide a clear and relatable backdrop that helps your audience understand who your client is, what they do, and what stakes are at play for them.

How to create a company overview slide:

Offer key details about the client's business —what's their industry? What's their market position?

Highlight the client's aspirations and values —this helps to humanize the company and build emotional connection.

Make sure to relate the company's context back to your reader. How does this company's situation reflect the challenges or opportunities your reader might face?

Here’s an example of a company overview slide:

3. The problem or challenge

This is the conflict that propels your story. It's the mountain your client needs to climb, the dragon they must slay. Without a significant problem or challenge, there's no tension, and without tension, there's no story and no engagement.

How to create a problem slide:

Clearly articulate the problem or challenge. Make it tangible and relatable.

Explore the implications of this problem. What's at stake for the client if it goes unresolved?

Aim to evoke emotion here. The more your reader feels the weight of the problem, the more invested they'll be in the solution.

Here’s an example of a problem slide:

4. Your solution

Enter the trusted guide and confidant—your product or service. This is the pivotal moment where your client's fortunes begin to turn. Show how your offering comes into play, lighting the way toward resolution.

How to create a solution slide:

Detail how your solution addresses the client's problem. Show how the features of your product or service connect to the challenges at hand.

Walk your reader through the implementation process. Offer insights into the collaborative efforts and innovative approaches that made the difference.

Don’t shy away from any obstacles or setbacks that occurred during the solution phase. Showing how you overcame these can actually make your story more credible and relatable.

Here’s an example of a solution slide:

This is the climax of your story, where all the tension that's been built up finally gets released. You need to demonstrate the transformation that occurred as a result of your solution.

How to create a results slide:

Show, don't tell. Use numbers, stats, and graphs to make your results concrete and impactful.

Discuss not just quantitative, but also qualitative results. How did your solution affect the client's morale, their customer satisfaction, their market reputation? Give detailed examples set in short anecdotes as experienced by a person (not an organization).

A side-by-side comparison of the 'before' and 'after' can be a powerful visual aid to highlight your impact.

Here’s an example of a results slide:

6. Customer quotes/testimonials

Nothing reinforces a story better than having the hero vouch for its authenticity. Direct quotes from your client add depth, credibility, and emotional resonance to your case study.

How to create a testimonials slide:

Select quotes that reinforce the narrative of your case study.

The more genuine and heartfelt, the better. Authenticity speaks volumes.

Consider sprinkling testimonials throughout the case study rather than bunching them together to keep the reader engaged.

Here’s an example of a testimonials slide:

7. Next steps

Your story doesn’t end when the problem is solved. This is where you guide your reader toward the future, inspiring them to take action based on the journey they've just been through.

How to create a next steps slide:

Provide clear and compelling calls-to-action. What do you want the reader to do next? Download a whitepaper? Request a demo? Sign up and try your solution? Make it a small concession, not a big ask. The next reasonable action they can take to establish the relationship a tiny bit further.

Make it simple for readers to take the next step. Include links, contact information, or even embed your calendar into the case study.

Here’s an example of a next steps slide:

What storytelling elements to include in a case study?

Compelling storytelling is an art, and when applied to business case studies, it can turn a rather dry piece of data into a riveting tale of success.

It's a chance to illustrate your value proposition in the real world, giving prospective clients a peek at what they could experience when they choose to work with you.

Here are some storytelling elements to include in your case study:

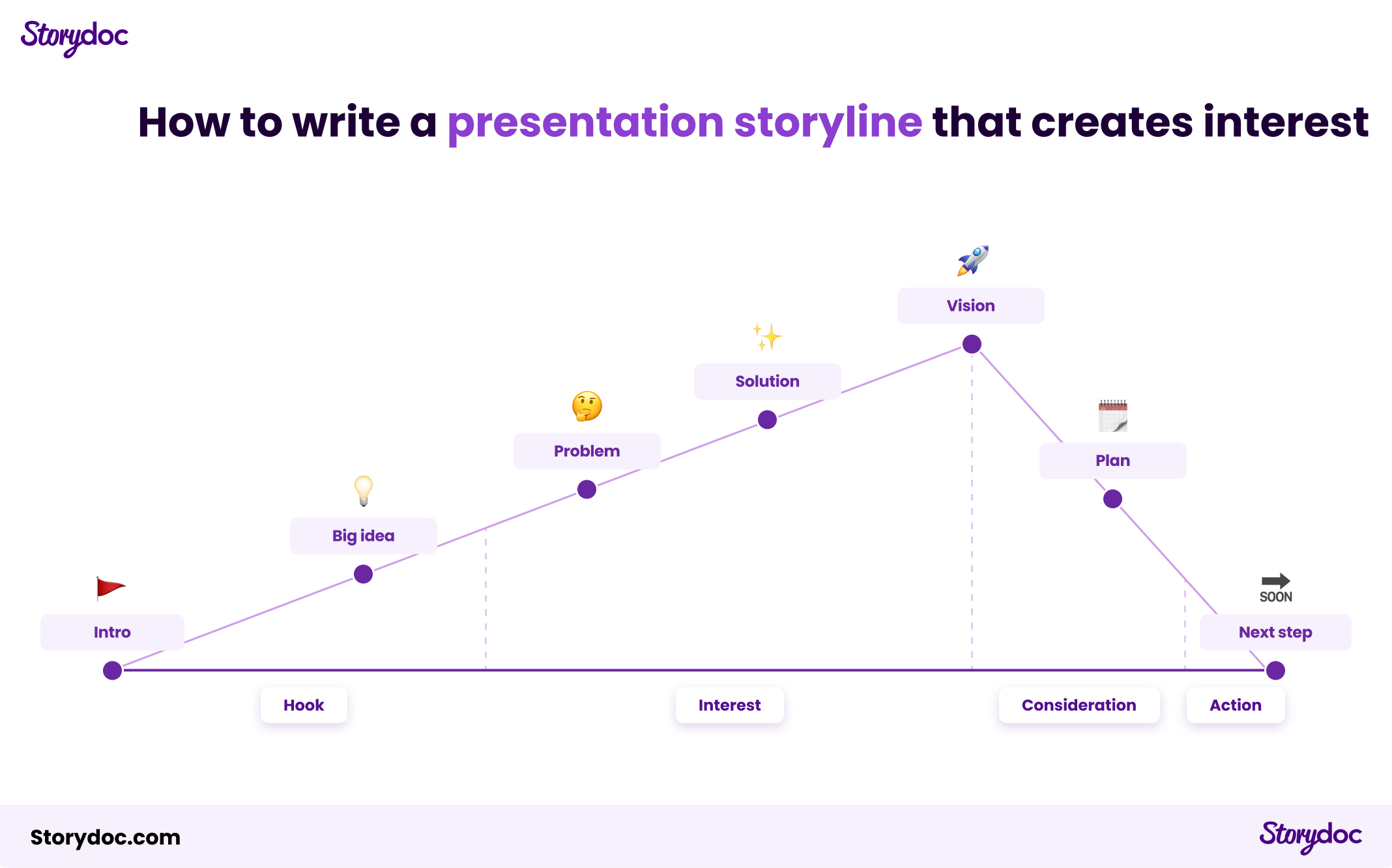

1. A clear storyline

Start with the basics: Who is your customer? What was their challenge? How did your product or service solve their problem? And, what was the outcome?

This forms the narrative arc of your case study, providing a backbone for your story. Ensure it’s a seamless narrative, taking the reader along a journey of transformation.

Here’s our recommended presentation storyline:

2. Concrete outcomes

Data provides the meat of your case study. Numbers, percentages, and concrete results serve as proof that your solution works.

It's one thing to claim that your product or service is effective, but showcasing the results achieved by a real customer through hard data adds credence to your assertions.

3. Visuals that support and expand on the text

Just as a picture is worth a thousand words, well-placed visuals in your case study can make the message clearer and more compelling.

Graphs, charts, and infographics can help break down complex data, making it easier for the audience to digest. Furthermore, they break up long blocks of text, making your case study more engaging.

4. Interactive elements

In a world where scrolling has become second nature, your case study needs to be more than a static document.

Incorporating interactive elements like tabs to click through benefits, live data calculators, or sliders with case studies and customer testimonials invites your audience to engage with your content actively.

Our research showed that decks with interactive elements got scrolled to the bottom 41% more often and had a 21% longer average reading time than non-interactive ones.

Making interactive case studies sounds complicated but it’s actually very easy if you do it with our AI case study creator . You can send it to prospects directly from Storydoc or embed it as part of your website.

By making your reader an active participant in the story, you boost their engagement and increase the chances of them reading your content through to the end.

Benefits of including interactive elements in your case study presentation

More decks read in full

Longer average reading time

5. Testimonials and quotes directly from customers

Customer testimonials and direct quotes inject a sense of authenticity and credibility into your case study.

They bring a human touch to your narrative and foster trust in potential clients.

It's no longer just your voice touting the effectiveness of your solution; it's the voice of a satisfied customer who has personally experienced the benefits of your product or service.

6. Clear call to action

Finally, after painting a vivid picture of your product or service in action, you need to tell your audience what to do next.

A clear CTA—whether it’s to learn more, book a demo, or sign up—makes the next step evident for your audience.

Our data reveals that decks with a clear next step had a conversion rate 27% higher than those that ended with a generic "thank you."

Make the next step simple, straightforward, and compelling, so your reader knows precisely what to do to start their own success story with you.

What not to include in your case study?

While we've covered the essentials to include in your case study, it's equally important to identify elements that could distract from your message, decrease trust, or even confuse your audience.

Here's what you should avoid including in your case study:

1. Unverified claims / data

Every claim you make and every piece of data you share in your case study must be true and easy to check.

Trust is crucial in a case study, and even one bit of wrong information can damage trust and hurt your image.

So, make sure all your facts, figures, and results are correct, and always get the right permissions to share them.

2. Confidential or sensitive information

When writing a case study, it's crucial to remember that privacy matters. Even though it's exciting to share all the details, you need to protect your client's private information.

Always get clear permission before using any client data and remember to hide any information that could identify specific individuals.

This careful approach shows your respect for privacy and builds trust with your audience, making your case study not just engaging, but also responsible and professional.

3. Technical jargon

A case study should be easy for everyone to understand, so avoid using industry-specific language. Even if you know the jargon, your audience might not.

Keeping your language simple and clear will help more people understand your case study. Too much technical language can confuse readers and distract from the story you're trying to tell.

4. Salesy language

While a case study is designed to show prospective clients how valuable your offer is, it's important not to sound too pushy.

A case study should tell a story, not sound like a sales pitch. Keep your language helpful and interesting. The success story should be enough to sell itself.

Create your best case study yet from ready-made templates

Now that you're equipped with all the essentials of crafting a compelling case study, it's time to bring your narrative to life.

Don’t work hard if you can work easy and get better results.

Interactive case study templates are your shortcut to creating engaging and informative case studies. They provide a clear path for your narrative, intuitive ways to present your data, and an engaging space for sharing customer testimonials.

Grab a template, and let your story do the talking!

Hi, I'm Dominika, Content Specialist at Storydoc. As a creative professional with experience in fashion, I'm here to show you how to amplify your brand message through the power of storytelling and eye-catching visuals.

Found this post useful?

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Get notified as more awesome content goes live.

(No spam, no ads, opt-out whenever)

You've just joined an elite group of people that make the top performing 1% of sales and marketing collateral.

Create your best case study to date

Try Storydoc interactive case study creator for 14 days free (keep any presentation you make forever!)

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Definition and Introduction

Case analysis is a problem-based teaching and learning method that involves critically analyzing complex scenarios within an organizational setting for the purpose of placing the student in a “real world” situation and applying reflection and critical thinking skills to contemplate appropriate solutions, decisions, or recommended courses of action. It is considered a more effective teaching technique than in-class role playing or simulation activities. The analytical process is often guided by questions provided by the instructor that ask students to contemplate relationships between the facts and critical incidents described in the case.

Cases generally include both descriptive and statistical elements and rely on students applying abductive reasoning to develop and argue for preferred or best outcomes [i.e., case scenarios rarely have a single correct or perfect answer based on the evidence provided]. Rather than emphasizing theories or concepts, case analysis assignments emphasize building a bridge of relevancy between abstract thinking and practical application and, by so doing, teaches the value of both within a specific area of professional practice.

Given this, the purpose of a case analysis paper is to present a structured and logically organized format for analyzing the case situation. It can be assigned to students individually or as a small group assignment and it may include an in-class presentation component. Case analysis is predominately taught in economics and business-related courses, but it is also a method of teaching and learning found in other applied social sciences disciplines, such as, social work, public relations, education, journalism, and public administration.

Ellet, William. The Case Study Handbook: A Student's Guide . Revised Edition. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2018; Christoph Rasche and Achim Seisreiner. Guidelines for Business Case Analysis . University of Potsdam; Writing a Case Analysis . Writing Center, Baruch College; Volpe, Guglielmo. "Case Teaching in Economics: History, Practice and Evidence." Cogent Economics and Finance 3 (December 2015). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1120977.

How to Approach Writing a Case Analysis Paper

The organization and structure of a case analysis paper can vary depending on the organizational setting, the situation, and how your professor wants you to approach the assignment. Nevertheless, preparing to write a case analysis paper involves several important steps. As Hawes notes, a case analysis assignment “...is useful in developing the ability to get to the heart of a problem, analyze it thoroughly, and to indicate the appropriate solution as well as how it should be implemented” [p.48]. This statement encapsulates how you should approach preparing to write a case analysis paper.

Before you begin to write your paper, consider the following analytical procedures:

- Review the case to get an overview of the situation . A case can be only a few pages in length, however, it is most often very lengthy and contains a significant amount of detailed background information and statistics, with multilayered descriptions of the scenario, the roles and behaviors of various stakeholder groups, and situational events. Therefore, a quick reading of the case will help you gain an overall sense of the situation and illuminate the types of issues and problems that you will need to address in your paper. If your professor has provided questions intended to help frame your analysis, use them to guide your initial reading of the case.

- Read the case thoroughly . After gaining a general overview of the case, carefully read the content again with the purpose of understanding key circumstances, events, and behaviors among stakeholder groups. Look for information or data that appears contradictory, extraneous, or misleading. At this point, you should be taking notes as you read because this will help you develop a general outline of your paper. The aim is to obtain a complete understanding of the situation so that you can begin contemplating tentative answers to any questions your professor has provided or, if they have not provided, developing answers to your own questions about the case scenario and its connection to the course readings,lectures, and class discussions.

- Determine key stakeholder groups, issues, and events and the relationships they all have to each other . As you analyze the content, pay particular attention to identifying individuals, groups, or organizations described in the case and identify evidence of any problems or issues of concern that impact the situation in a negative way. Other things to look for include identifying any assumptions being made by or about each stakeholder, potential biased explanations or actions, explicit demands or ultimatums , and the underlying concerns that motivate these behaviors among stakeholders. The goal at this stage is to develop a comprehensive understanding of the situational and behavioral dynamics of the case and the explicit and implicit consequences of each of these actions.

- Identify the core problems . The next step in most case analysis assignments is to discern what the core [i.e., most damaging, detrimental, injurious] problems are within the organizational setting and to determine their implications. The purpose at this stage of preparing to write your analysis paper is to distinguish between the symptoms of core problems and the core problems themselves and to decide which of these must be addressed immediately and which problems do not appear critical but may escalate over time. Identify evidence from the case to support your decisions by determining what information or data is essential to addressing the core problems and what information is not relevant or is misleading.

- Explore alternative solutions . As noted, case analysis scenarios rarely have only one correct answer. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind that the process of analyzing the case and diagnosing core problems, while based on evidence, is a subjective process open to various avenues of interpretation. This means that you must consider alternative solutions or courses of action by critically examining strengths and weaknesses, risk factors, and the differences between short and long-term solutions. For each possible solution or course of action, consider the consequences they may have related to their implementation and how these recommendations might lead to new problems. Also, consider thinking about your recommended solutions or courses of action in relation to issues of fairness, equity, and inclusion.

- Decide on a final set of recommendations . The last stage in preparing to write a case analysis paper is to assert an opinion or viewpoint about the recommendations needed to help resolve the core problems as you see them and to make a persuasive argument for supporting this point of view. Prepare a clear rationale for your recommendations based on examining each element of your analysis. Anticipate possible obstacles that could derail their implementation. Consider any counter-arguments that could be made concerning the validity of your recommended actions. Finally, describe a set of criteria and measurable indicators that could be applied to evaluating the effectiveness of your implementation plan.

Use these steps as the framework for writing your paper. Remember that the more detailed you are in taking notes as you critically examine each element of the case, the more information you will have to draw from when you begin to write. This will save you time.

NOTE : If the process of preparing to write a case analysis paper is assigned as a student group project, consider having each member of the group analyze a specific element of the case, including drafting answers to the corresponding questions used by your professor to frame the analysis. This will help make the analytical process more efficient and ensure that the distribution of work is equitable. This can also facilitate who is responsible for drafting each part of the final case analysis paper and, if applicable, the in-class presentation.

Framework for Case Analysis . College of Management. University of Massachusetts; Hawes, Jon M. "Teaching is Not Telling: The Case Method as a Form of Interactive Learning." Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education 5 (Winter 2004): 47-54; Rasche, Christoph and Achim Seisreiner. Guidelines for Business Case Analysis . University of Potsdam; Writing a Case Study Analysis . University of Arizona Global Campus Writing Center; Van Ness, Raymond K. A Guide to Case Analysis . School of Business. State University of New York, Albany; Writing a Case Analysis . Business School, University of New South Wales.

Structure and Writing Style

A case analysis paper should be detailed, concise, persuasive, clearly written, and professional in tone and in the use of language . As with other forms of college-level academic writing, declarative statements that convey information, provide a fact, or offer an explanation or any recommended courses of action should be based on evidence. If allowed by your professor, any external sources used to support your analysis, such as course readings, should be properly cited under a list of references. The organization and structure of case analysis papers can vary depending on your professor’s preferred format, but its structure generally follows the steps used for analyzing the case.

Introduction

The introduction should provide a succinct but thorough descriptive overview of the main facts, issues, and core problems of the case . The introduction should also include a brief summary of the most relevant details about the situation and organizational setting. This includes defining the theoretical framework or conceptual model on which any questions were used to frame your analysis.

Following the rules of most college-level research papers, the introduction should then inform the reader how the paper will be organized. This includes describing the major sections of the paper and the order in which they will be presented. Unless you are told to do so by your professor, you do not need to preview your final recommendations in the introduction. U nlike most college-level research papers , the introduction does not include a statement about the significance of your findings because a case analysis assignment does not involve contributing new knowledge about a research problem.

Background Analysis

Background analysis can vary depending on any guiding questions provided by your professor and the underlying concept or theory that the case is based upon. In general, however, this section of your paper should focus on:

- Providing an overarching analysis of problems identified from the case scenario, including identifying events that stakeholders find challenging or troublesome,

- Identifying assumptions made by each stakeholder and any apparent biases they may exhibit,

- Describing any demands or claims made by or forced upon key stakeholders, and

- Highlighting any issues of concern or complaints expressed by stakeholders in response to those demands or claims.

These aspects of the case are often in the form of behavioral responses expressed by individuals or groups within the organizational setting. However, note that problems in a case situation can also be reflected in data [or the lack thereof] and in the decision-making, operational, cultural, or institutional structure of the organization. Additionally, demands or claims can be either internal and external to the organization [e.g., a case analysis involving a president considering arms sales to Saudi Arabia could include managing internal demands from White House advisors as well as demands from members of Congress].

Throughout this section, present all relevant evidence from the case that supports your analysis. Do not simply claim there is a problem, an assumption, a demand, or a concern; tell the reader what part of the case informed how you identified these background elements.

Identification of Problems

In most case analysis assignments, there are problems, and then there are problems . Each problem can reflect a multitude of underlying symptoms that are detrimental to the interests of the organization. The purpose of identifying problems is to teach students how to differentiate between problems that vary in severity, impact, and relative importance. Given this, problems can be described in three general forms: those that must be addressed immediately, those that should be addressed but the impact is not severe, and those that do not require immediate attention and can be set aside for the time being.

All of the problems you identify from the case should be identified in this section of your paper, with a description based on evidence explaining the problem variances. If the assignment asks you to conduct research to further support your assessment of the problems, include this in your explanation. Remember to cite those sources in a list of references. Use specific evidence from the case and apply appropriate concepts, theories, and models discussed in class or in relevant course readings to highlight and explain the key problems [or problem] that you believe must be solved immediately and describe the underlying symptoms and why they are so critical.

Alternative Solutions

This section is where you provide specific, realistic, and evidence-based solutions to the problems you have identified and make recommendations about how to alleviate the underlying symptomatic conditions impacting the organizational setting. For each solution, you must explain why it was chosen and provide clear evidence to support your reasoning. This can include, for example, course readings and class discussions as well as research resources, such as, books, journal articles, research reports, or government documents. In some cases, your professor may encourage you to include personal, anecdotal experiences as evidence to support why you chose a particular solution or set of solutions. Using anecdotal evidence helps promote reflective thinking about the process of determining what qualifies as a core problem and relevant solution .

Throughout this part of the paper, keep in mind the entire array of problems that must be addressed and describe in detail the solutions that might be implemented to resolve these problems.

Recommended Courses of Action

In some case analysis assignments, your professor may ask you to combine the alternative solutions section with your recommended courses of action. However, it is important to know the difference between the two. A solution refers to the answer to a problem. A course of action refers to a procedure or deliberate sequence of activities adopted to proactively confront a situation, often in the context of accomplishing a goal. In this context, proposed courses of action are based on your analysis of alternative solutions. Your description and justification for pursuing each course of action should represent the overall plan for implementing your recommendations.

For each course of action, you need to explain the rationale for your recommendation in a way that confronts challenges, explains risks, and anticipates any counter-arguments from stakeholders. Do this by considering the strengths and weaknesses of each course of action framed in relation to how the action is expected to resolve the core problems presented, the possible ways the action may affect remaining problems, and how the recommended action will be perceived by each stakeholder.

In addition, you should describe the criteria needed to measure how well the implementation of these actions is working and explain which individuals or groups are responsible for ensuring your recommendations are successful. In addition, always consider the law of unintended consequences. Outline difficulties that may arise in implementing each course of action and describe how implementing the proposed courses of action [either individually or collectively] may lead to new problems [both large and small].

Throughout this section, you must consider the costs and benefits of recommending your courses of action in relation to uncertainties or missing information and the negative consequences of success.

The conclusion should be brief and introspective. Unlike a research paper, the conclusion in a case analysis paper does not include a summary of key findings and their significance, a statement about how the study contributed to existing knowledge, or indicate opportunities for future research.

Begin by synthesizing the core problems presented in the case and the relevance of your recommended solutions. This can include an explanation of what you have learned about the case in the context of your answers to the questions provided by your professor. The conclusion is also where you link what you learned from analyzing the case with the course readings or class discussions. This can further demonstrate your understanding of the relationships between the practical case situation and the theoretical and abstract content of assigned readings and other course content.

Problems to Avoid

The literature on case analysis assignments often includes examples of difficulties students have with applying methods of critical analysis and effectively reporting the results of their assessment of the situation. A common reason cited by scholars is that the application of this type of teaching and learning method is limited to applied fields of social and behavioral sciences and, as a result, writing a case analysis paper can be unfamiliar to most students entering college.

After you have drafted your paper, proofread the narrative flow and revise any of these common errors:

- Unnecessary detail in the background section . The background section should highlight the essential elements of the case based on your analysis. Focus on summarizing the facts and highlighting the key factors that become relevant in the other sections of the paper by eliminating any unnecessary information.

- Analysis relies too much on opinion . Your analysis is interpretive, but the narrative must be connected clearly to evidence from the case and any models and theories discussed in class or in course readings. Any positions or arguments you make should be supported by evidence.

- Analysis does not focus on the most important elements of the case . Your paper should provide a thorough overview of the case. However, the analysis should focus on providing evidence about what you identify are the key events, stakeholders, issues, and problems. Emphasize what you identify as the most critical aspects of the case to be developed throughout your analysis. Be thorough but succinct.

- Writing is too descriptive . A paper with too much descriptive information detracts from your analysis of the complexities of the case situation. Questions about what happened, where, when, and by whom should only be included as essential information leading to your examination of questions related to why, how, and for what purpose.

- Inadequate definition of a core problem and associated symptoms . A common error found in case analysis papers is recommending a solution or course of action without adequately defining or demonstrating that you understand the problem. Make sure you have clearly described the problem and its impact and scope within the organizational setting. Ensure that you have adequately described the root causes w hen describing the symptoms of the problem.

- Recommendations lack specificity . Identify any use of vague statements and indeterminate terminology, such as, “A particular experience” or “a large increase to the budget.” These statements cannot be measured and, as a result, there is no way to evaluate their successful implementation. Provide specific data and use direct language in describing recommended actions.

- Unrealistic, exaggerated, or unattainable recommendations . Review your recommendations to ensure that they are based on the situational facts of the case. Your recommended solutions and courses of action must be based on realistic assumptions and fit within the constraints of the situation. Also note that the case scenario has already happened, therefore, any speculation or arguments about what could have occurred if the circumstances were different should be revised or eliminated.

Bee, Lian Song et al. "Business Students' Perspectives on Case Method Coaching for Problem-Based Learning: Impacts on Student Engagement and Learning Performance in Higher Education." Education & Training 64 (2022): 416-432; The Case Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing and Michigan Authors. Grand Valley State University; Georgallis, Panikos and Kayleigh Bruijn. "Sustainability Teaching using Case-Based Debates." Journal of International Education in Business 15 (2022): 147-163; Hawes, Jon M. "Teaching is Not Telling: The Case Method as a Form of Interactive Learning." Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education 5 (Winter 2004): 47-54; Georgallis, Panikos, and Kayleigh Bruijn. "Sustainability Teaching Using Case-based Debates." Journal of International Education in Business 15 (2022): 147-163; .Dean, Kathy Lund and Charles J. Fornaciari. "How to Create and Use Experiential Case-Based Exercises in a Management Classroom." Journal of Management Education 26 (October 2002): 586-603; Klebba, Joanne M. and Janet G. Hamilton. "Structured Case Analysis: Developing Critical Thinking Skills in a Marketing Case Course." Journal of Marketing Education 29 (August 2007): 132-137, 139; Klein, Norman. "The Case Discussion Method Revisited: Some Questions about Student Skills." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 30-32; Mukherjee, Arup. "Effective Use of In-Class Mini Case Analysis for Discovery Learning in an Undergraduate MIS Course." The Journal of Computer Information Systems 40 (Spring 2000): 15-23; Pessoa, Silviaet al. "Scaffolding the Case Analysis in an Organizational Behavior Course: Making Analytical Language Explicit." Journal of Management Education 46 (2022): 226-251: Ramsey, V. J. and L. D. Dodge. "Case Analysis: A Structured Approach." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 27-29; Schweitzer, Karen. "How to Write and Format a Business Case Study." ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/how-to-write-and-format-a-business-case-study-466324 (accessed December 5, 2022); Reddy, C. D. "Teaching Research Methodology: Everything's a Case." Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 18 (December 2020): 178-188; Volpe, Guglielmo. "Case Teaching in Economics: History, Practice and Evidence." Cogent Economics and Finance 3 (December 2015). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1120977.

Writing Tip

Ca se Study and Case Analysis Are Not the Same!

Confusion often exists between what it means to write a paper that uses a case study research design and writing a paper that analyzes a case; they are two different types of approaches to learning in the social and behavioral sciences. Professors as well as educational researchers contribute to this confusion because they often use the term "case study" when describing the subject of analysis for a case analysis paper. But you are not studying a case for the purpose of generating a comprehensive, multi-faceted understanding of a research problem. R ather, you are critically analyzing a specific scenario to argue logically for recommended solutions and courses of action that lead to optimal outcomes applicable to professional practice.

To avoid any confusion, here are twelve characteristics that delineate the differences between writing a paper using the case study research method and writing a case analysis paper:

- Case study is a method of in-depth research and rigorous inquiry ; case analysis is a reliable method of teaching and learning . A case study is a modality of research that investigates a phenomenon for the purpose of creating new knowledge, solving a problem, or testing a hypothesis using empirical evidence derived from the case being studied. Often, the results are used to generalize about a larger population or within a wider context. The writing adheres to the traditional standards of a scholarly research study. A case analysis is a pedagogical tool used to teach students how to reflect and think critically about a practical, real-life problem in an organizational setting.

- The researcher is responsible for identifying the case to study; a case analysis is assigned by your professor . As the researcher, you choose the case study to investigate in support of obtaining new knowledge and understanding about the research problem. The case in a case analysis assignment is almost always provided, and sometimes written, by your professor and either given to every student in class to analyze individually or to a small group of students, or students select a case to analyze from a predetermined list.

- A case study is indeterminate and boundless; a case analysis is predetermined and confined . A case study can be almost anything [see item 9 below] as long as it relates directly to examining the research problem. This relationship is the only limit to what a researcher can choose as the subject of their case study. The content of a case analysis is determined by your professor and its parameters are well-defined and limited to elucidating insights of practical value applied to practice.

- Case study is fact-based and describes actual events or situations; case analysis can be entirely fictional or adapted from an actual situation . The entire content of a case study must be grounded in reality to be a valid subject of investigation in an empirical research study. A case analysis only needs to set the stage for critically examining a situation in practice and, therefore, can be entirely fictional or adapted, all or in-part, from an actual situation.

- Research using a case study method must adhere to principles of intellectual honesty and academic integrity; a case analysis scenario can include misleading or false information . A case study paper must report research objectively and factually to ensure that any findings are understood to be logically correct and trustworthy. A case analysis scenario may include misleading or false information intended to deliberately distract from the central issues of the case. The purpose is to teach students how to sort through conflicting or useless information in order to come up with the preferred solution. Any use of misleading or false information in academic research is considered unethical.

- Case study is linked to a research problem; case analysis is linked to a practical situation or scenario . In the social sciences, the subject of an investigation is most often framed as a problem that must be researched in order to generate new knowledge leading to a solution. Case analysis narratives are grounded in real life scenarios for the purpose of examining the realities of decision-making behavior and processes within organizational settings. A case analysis assignments include a problem or set of problems to be analyzed. However, the goal is centered around the act of identifying and evaluating courses of action leading to best possible outcomes.

- The purpose of a case study is to create new knowledge through research; the purpose of a case analysis is to teach new understanding . Case studies are a choice of methodological design intended to create new knowledge about resolving a research problem. A case analysis is a mode of teaching and learning intended to create new understanding and an awareness of uncertainty applied to practice through acts of critical thinking and reflection.