7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Describe the functionalist view of deviance in society through four sociologist’s theories

- Explain how conflict theory understands deviance and crime in society

- Describe the symbolic interactionist approach to deviance, including labeling and other theories

Why does deviance occur? How does it affect a society? Since the early days of sociology, scholars have developed theories that attempt to explain what deviance and crime mean to society. These theories can be grouped according to the three major sociological paradigms: functionalism, symbolic interactionism, and conflict theory.

Functionalism

Sociologists who follow the functionalist approach are concerned with the way the different elements of a society contribute to the whole. They view deviance as a key component of a functioning society. Strain theory and social disorganization theory represent two functionalist perspectives on deviance in society.

Émile Durkheim: The Essential Nature of Deviance

Émile Durkheim believed that deviance is a necessary part of a successful society. One way deviance is functional, he argued, is that it challenges people’s present views (1893). For instance, when Black students across the United States participated in sit-ins during the civil rights movement, they challenged society’s notions of segregation. Moreover, Durkheim noted, when deviance is punished, it reaffirms currently held social norms, which also contributes to society (1893). Seeing a student given detention for skipping class reminds other high schoolers that playing hooky isn’t allowed and that they, too, could get detention.

Durkheim’s point regarding the impact of punishing deviance speaks to his arguments about law. Durkheim saw laws as an expression of the “collective conscience,” which are the beliefs, morals, and attitudes of a society. “A crime is a crime because we condemn it,” he said (1893). He discussed the impact of societal size and complexity as contributors to the collective conscience and the development of justice systems and punishments. For example, in large, industrialized societies that were largely bound together by the interdependence of work (the division of labor), punishments for deviance were generally less severe. In smaller, more homogeneous societies, deviance might be punished more severely.

Robert Merton: Strain Theory

Sociologist Robert Merton agreed that deviance is an inherent part of a functioning society, but he expanded on Durkheim’s ideas by developing strain theory , which notes that access to socially acceptable goals plays a part in determining whether a person conforms or deviates. From birth, we’re encouraged to achieve the “American Dream” of financial success. A person who attends business school, receives an MBA, and goes on to make a million-dollar income as CEO of a company is said to be a success. However, not everyone in our society stands on equal footing. That MBA-turned-CEO may have grown up in the best school district and had means to hire tutors. Another person may grow up in a neighborhood with lower-quality schools, and may not be able to pay for extra help. A person may have the socially acceptable goal of financial success but lack a socially acceptable way to reach that goal. According to Merton’s theory, an entrepreneur who can’t afford to launch their own company may be tempted to embezzle from their employer for start-up funds.

Merton defined five ways people respond to this gap between having a socially accepted goal and having no socially accepted way to pursue it.

- Conformity : Those who conform choose not to deviate. They pursue their goals to the extent that they can through socially accepted means.

- Innovation : Those who innovate pursue goals they cannot reach through legitimate means by instead using criminal or deviant means.

- Ritualism : People who ritualize lower their goals until they can reach them through socially acceptable ways. These members of society focus on conformity rather than attaining a distant dream.

- Retreatism : Others retreat and reject society’s goals and means. Some people who beg and people who are homeless have withdrawn from society’s goal of financial success.

- Rebellion : A handful of people rebel and replace a society’s goals and means with their own. Terrorists or freedom fighters look to overthrow a society’s goals through socially unacceptable means.

Social Disorganization Theory

Developed by researchers at the University of Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s, social disorganization theory asserts that crime is most likely to occur in communities with weak social ties and the absence of social control. An individual who grows up in a poor neighborhood with high rates of drug use, violence, teenage delinquency, and deprived parenting is more likely to become engaged in crime than an individual from a wealthy neighborhood with a good school system and families who are involved positively in the community.

Social disorganization theory points to broad social factors as the cause of deviance. A person isn’t born as someone who will commit crimes but becomes one over time, often based on factors in their social environment. Robert Sampson and Byron Groves (1989) found that poverty and family disruption in given localities had a strong positive correlation with social disorganization. They also determined that social disorganization was, in turn, associated with high rates of crime and delinquency—or deviance. Recent studies Sampson conducted with Lydia Bean (2006) revealed similar findings. High rates of poverty and single-parent homes correlated with high rates of juvenile violence. Research into social disorganization theory can greatly influence public policy. For instance, studies have found that children from disadvantaged communities who attend preschool programs that teach basic social skills are significantly less likely to engage in criminal activity. (Lally 1987)

Conflict Theory

Conflict theory looks to social and economic factors as the causes of crime and deviance. Unlike functionalists, conflict theorists don’t see these factors as positive functions of society. They see them as evidence of inequality in the system. They also challenge social disorganization theory and control theory and argue that both ignore racial and socioeconomic issues and oversimplify social trends (Akers 1991). Conflict theorists also look for answers to the correlation of gender and race with wealth and crime.

Karl Marx: An Unequal System

Conflict theory was greatly influenced by the work of German philosopher, economist, and social scientist Karl Marx. Marx believed that the general population was divided into two groups. He labeled the wealthy, who controlled the means of production and business, the bourgeois. He labeled the workers who depended on the bourgeois for employment and survival the proletariat. Marx believed that the bourgeois centralized their power and influence through government, laws, and other authority agencies in order to maintain and expand their positions of power in society. Though Marx spoke little of deviance, his ideas created the foundation for conflict theorists who study the intersection of deviance and crime with wealth and power.

C. Wright Mills: The Power Elite

In his book The Power Elite (1956), sociologist C. Wright Mills described the existence of what he dubbed the power elite , a small group of wealthy and influential people at the top of society who hold the power and resources. Wealthy executives, politicians, celebrities, and military leaders often have access to national and international power, and in some cases, their decisions affect everyone in society. Because of this, the rules of society are stacked in favor of a privileged few who manipulate them to stay on top. It is these people who decide what is criminal and what is not, and the effects are often felt most by those who have little power. Mills’ theories explain why celebrities can commit crimes and suffer little or no legal retribution. For example, USA Today maintains a database of NFL players accused and convicted of crimes. 51 NFL players had been convicted of committing domestic violence between the years 2000 and 2019. They have been sentenced to a collective 49 days in jail, and most of those sentences were deferred or otherwise reduced. In most cases, suspensions and fines levied by the NFL or individual teams were more severe than the justice system's (Schrotenboer 2020 and clickitticket.com 2019).

Crime and Social Class

While crime is often associated with the underprivileged, crimes committed by the wealthy and powerful remain an under-punished and costly problem within society. The FBI reported that victims of burglary, larceny, and motor vehicle theft lost a total of $15.3 billion dollars in 2009 (FB1 2010). In comparison, when former advisor and financier Bernie Madoff was arrested in 2008, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission reported that the estimated losses of his financial Ponzi scheme fraud were close to $50 billion (SEC 2009).

This imbalance based on class power is also found within U.S. criminal law. In the 1980s, the use of crack cocaine (a less expensive but powerful drug) quickly became an epidemic that swept the country’s poorest urban communities. Its pricier counterpart, cocaine, was associated with upscale users and was a drug of choice for the wealthy. The legal implications of being caught by authorities with crack versus cocaine were starkly different. In 1986, federal law mandated that being caught in possession of 50 grams of crack was punishable by a ten-year prison sentence. An equivalent prison sentence for cocaine possession, however, required possession of 5,000 grams. In other words, the sentencing disparity was 1 to 100 (New York Times Editorial Staff 2011). This inequality in the severity of punishment for crack versus cocaine paralleled the unequal social class of respective users. A conflict theorist would note that those in society who hold the power are also the ones who make the laws concerning crime. In doing so, they make laws that will benefit them, while the powerless classes who lack the resources to make such decisions suffer the consequences. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, states passed numerous laws increasing penalties, especially for repeat offenders. The U.S. government passed an even more significant law, the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (known as the 1994 Crime Bill), which further increased penalties, funded prisons, and incentivized law enforcement agencies to further pursue drug offenders. One outcome of these policies was the mass incarceration of Black and Hispanic people, which led to a cycle of poverty and reduced social mobility. The crack-cocaine punishment disparity remained until 2010, when President Obama signed the Fair Sentencing Act, which decreased the disparity to 1 to 18 (The Sentencing Project 2010).

Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic interactionism is a theoretical approach that can be used to explain how societies and/or social groups come to view behaviors as deviant or conventional.

Labeling Theory

Although all of us violate norms from time to time, few people would consider themselves deviant. Those who do, however, have often been labeled “deviant” by society and have gradually come to believe it themselves. Labeling theory examines the ascribing of a deviant behavior to another person by members of society. Thus, what is considered deviant is determined not so much by the behaviors themselves or the people who commit them, but by the reactions of others to these behaviors. As a result, what is considered deviant changes over time and can vary significantly across cultures.

Sociologist Edwin Lemert expanded on the concepts of labeling theory and identified two types of deviance that affect identity formation. Primary deviance is a violation of norms that does not result in any long-term effects on the individual’s self-image or interactions with others. Speeding is a deviant act, but receiving a speeding ticket generally does not make others view you as a bad person, nor does it alter your own self-concept. Individuals who engage in primary deviance still maintain a feeling of belonging in society and are likely to continue to conform to norms in the future.

Sometimes, in more extreme cases, primary deviance can morph into secondary deviance. Secondary deviance occurs when a person’s self-concept and behavior begin to change after his or her actions are labeled as deviant by members of society. The person may begin to take on and fulfill the role of a “deviant” as an act of rebellion against the society that has labeled that individual as such. For example, consider a high school student who often cuts class and gets into fights. The student is reprimanded frequently by teachers and school staff, and soon enough, develops a reputation as a “troublemaker.” As a result, the student starts acting out even more and breaking more rules; the student has adopted the “troublemaker” label and embraced this deviant identity. Secondary deviance can be so strong that it bestows a master status on an individual. A master status is a label that describes the chief characteristic of an individual. Some people see themselves primarily as doctors, artists, or grandfathers. Others see themselves as beggars, convicts, or addicts.

Techniques of Neutralization

How do people deal with the labels they are given? This was the subject of a study done by Sykes and Matza (1957). They studied teenage boys who had been labeled as juvenile delinquents to see how they either embraced or denied these labels. Have you ever used any of these techniques?

Let’s take a scenario and apply all five techniques to explain how they are used. A young person is working for a retail store as a cashier. Their cash drawer has been coming up short for a few days. When the boss confronts the employee, they are labeled as a thief for the suspicion of stealing. How does the employee deal with this label?

The Denial of Responsibility: When someone doesn’t take responsibility for their actions or blames others. They may use this technique and say that it was their boss’s fault because they don’t get paid enough to make rent or because they’re getting a divorce. They are rejecting the label by denying responsibility for the action.

The Denial of Injury: Sometimes people will look at a situation in terms of what effect it has on others. If the employee uses this technique they may say, “What’s the big deal? Nobody got hurt. Your insurance will take care of it.” The person doesn’t see their actions as a big deal because nobody “got hurt.”

The Denial of the Victim: If there is no victim there’s no crime. In this technique the person sees their actions as justified or that the victim deserved it. Our employee may look at their situation and say, “I’ve worked here for years without a raise. I was owed that money and if you won’t give it to me I’ll get it my own way.”

The Condemnation of the Condemners: The employee might “turn it around on” the boss by blaming them. They may say something like, “You don’t know my life, you have no reason to judge me.” This is taking the focus off of their actions and putting the onus on the accuser to, essentially, prove the person is living up to the label, which also shifts the narrative away from the deviant behavior.

Appeal to a Higher Authority: The final technique that may be used is to claim that the actions were for a higher purpose. The employee may tell the boss that they stole the money because their mom is sick and needs medicine or something like that. They are justifying their actions by making it seem as though the purpose for the behavior is a greater “good” than the action is “bad.” (Sykes & Matza, 1957)

Social Policy and Debate

The right to vote.

Before she lost her job as an administrative assistant, Leola Strickland postdated and mailed a handful of checks for amounts ranging from $90 to $500. By the time she was able to find a new job, the checks had bounced, and she was convicted of fraud under Mississippi law. Strickland pleaded guilty to a felony charge and repaid her debts; in return, she was spared from serving prison time.

Strickland appeared in court in 2001. More than ten years later, she is still feeling the sting of her sentencing. Why? Because Mississippi is one of twelve states in the United States that bans convicted felons from voting (ProCon 2011).

To Strickland, who said she had always voted, the news came as a great shock. She isn’t alone. Some 5.3 million people in the United States are currently barred from voting because of felony convictions (ProCon 2009). These individuals include inmates, parolees, probationers, and even people who have never been jailed, such as Leola Strickland.

Under the Fourteenth Amendment, states are allowed to deny voting privileges to individuals who have participated in “rebellion or other crime” (Krajick 2004). Although there are no federally mandated laws on the matter, most states practice at least one form of felony disenfranchisement .

Is it fair to prevent citizens from participating in such an important process? Proponents of disfranchisement laws argue that felons have a debt to pay to society. Being stripped of their right to vote is part of the punishment for criminal deeds. Such proponents point out that voting isn’t the only instance in which ex-felons are denied rights; state laws also ban released criminals from holding public office, obtaining professional licenses, and sometimes even inheriting property (Lott and Jones 2008).

Opponents of felony disfranchisement in the United States argue that voting is a basic human right and should be available to all citizens regardless of past deeds. Many point out that felony disfranchisement has its roots in the 1800s, when it was used primarily to block Black citizens from voting. These laws disproportionately target poor minority members, denying them a chance to participate in a system that, as a social conflict theorist would point out, is already constructed to their disadvantage (Holding 2006). Those who cite labeling theory worry that denying deviants the right to vote will only further encourage deviant behavior. If ex-criminals are disenfranchised from voting, are they being disenfranchised from society?

Edwin Sutherland: Differential Association

In the early 1900s, sociologist Edwin Sutherland sought to understand how deviant behavior developed among people. Since criminology was a young field, he drew on other aspects of sociology including social interactions and group learning (Laub 2006). His conclusions established differential association theory , which suggested that individuals learn deviant behavior from those close to them who provide models of and opportunities for deviance. According to Sutherland, deviance is less a personal choice and more a result of differential socialization processes. For example, a young person whose friends are sexually active is more likely to view sexual activity as acceptable. Sutherland developed a series of propositions to explain how deviance is learned. In proposition five, for example, he discussed how people begin to accept and participate in a behavior after learning whether it is viewed as “favorable” by those around them. In proposition six, Sutherland expressed the ways that exposure to more “definitions” favoring the deviant behavior than those opposing it may eventually lead a person to partake in deviance (Sutherland 1960), applying almost a quantitative element to the learning of certain behaviors. In the example above, a young person may find sexual activity more acceptable once a certain number of their friends become sexually active, not after only one does so.

Sutherland’s theory may explain why crime is multigenerational. A longitudinal study beginning in the 1960s found that the best predictor of antisocial and criminal behavior in children was whether their parents had been convicted of a crime (Todd and Jury 1996). Children who were younger than ten years old when their parents were convicted were more likely than other children to engage in spousal abuse and criminal behavior by their early thirties. Even when taking socioeconomic factors such as dangerous neighborhoods, poor school systems, and overcrowded housing into consideration, researchers found that parents were the main influence on the behavior of their offspring (Todd and Jury 1996).

Travis Hirschi: Control Theory

Continuing with an examination of large social factors, control theory states that social control is directly affected by the strength of social bonds and that deviance results from a feeling of disconnection from society. Individuals who believe they are a part of society are less likely to commit crimes against it.

Travis Hirschi (1969) identified four types of social bonds that connect people to society:

- Attachment measures our connections to others. When we are closely attached to people, we worry about their opinions of us. People conform to society’s norms in order to gain approval (and prevent disapproval) from family, friends, and romantic partners.

- Commitment refers to the investments we make in the community. A well-respected local businessperson who volunteers at their synagogue and is a member of the neighborhood block organization has more to lose from committing a crime than a person who doesn’t have a career or ties to the community.

- Similarly, levels of involvement , or participation in socially legitimate activities, lessen a person’s likelihood of deviance. A child who plays little league baseball and takes art classes has fewer opportunities to ______.

- The final bond, belief , is an agreement on common values in society. If a person views social values as beliefs, they will conform to them. An environmentalist is more likely to pick up trash in a park, because a clean environment is a social value to them (Hirschi 1969).

| Strain Theory | Robert Merton | A lack of ways to reach socially accepted goals by accepted methods |

| Social Disorganization Theory | University of Chicago researchers | Weak social ties and a lack of social control; society has lost the ability to enforce norms with some groups |

| Unequal System | Karl Marx | Inequalities in wealth and power that arise from the economic system |

| Power Elite | C. Wright Mills | Ability of those in power to define deviance in ways that maintain the status quo |

| Labeling Theory | Edwin Lemert | The reactions of others, particularly those in power who are able to determine labels |

| Differential Association Theory | Edwin Sutherland | Learning and modeling deviant behavior seen in other people close to the individual |

| Control Theory | Travis Hirschi | Feelings of disconnection from society |

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Sociology 3e

- Publication date: Jun 3, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime

© Aug 5, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Sociology of Deviance and Crime

The Study of Cultural Norms and What Happens When They Are Broken

- News & Issues

- Key Concepts

- Major Sociologists

- Research, Samples, and Statistics

- Recommended Reading

- Archaeology

Sociologists who study deviance and crime examine cultural norms, how they change over time, how they are enforced, and what happens to individuals and societies when norms are broken. Deviance and social norms vary among societies, communities, and times, and often sociologists are interested in why these differences exist and how these differences impact the individuals and groups in those areas.

Sociologists define deviance as behavior that is recognized as violating expected rules and norms . It is simply more than nonconformity, however; it is behavior that departs significantly from social expectations. In the sociological perspective on deviance, there is a subtlety that distinguishes it from our commonsense understanding of the same behavior. Sociologists stress social context, not just individual behavior. That is, deviance is looked at in terms of group processes, definitions, and judgments, and not just as unusual individual acts. Sociologists also recognize that not all behaviors are judged similarly by all groups. What is deviant to one group may not be considered deviant to another. Further, sociologists recognize that established rules and norms are socially created, not just morally decided or individually imposed. That is, deviance lies not just in the behavior itself, but in the social responses of groups to behavior by others.

Sociologists often use their understanding of deviance to help explain otherwise ordinary events, such as tattooing or body piercing, eating disorders, or drug and alcohol use. Many of the kinds of questions asked by sociologists who study deviance deal with the social context in which behaviors are committed. For example, are there conditions under which suicide is acceptable ? Would one who commits suicide in the face of a terminal illness be judged differently from a despondent person who jumps from a window?

Four Theoretical Approaches

Within the sociology of deviance and crime, there are four key theoretical perspectives from which researchers study why people violate laws or norms, and how society reacts to such acts. We'll review them briefly here.

Structural strain theory was developed by American sociologist Robert K. Merton and suggests that deviant behavior is the result of strain an individual may experience when the community or society in which they live does not provide the necessary means to achieve culturally valued goals. Merton reasoned that when society fails people in this way, they engage in deviant or criminal acts in order to achieve those goals (like economic success, for example).

Some sociologists approach the study of deviance and crime from a structural functionalist standpoint . They would argue that deviance is a necessary part of the process by which social order is achieved and maintained. From this standpoint, deviant behavior serves to remind the majority of the socially agreed upon rules, norms, and taboos , which reinforces their value and thus social order.

Conflict theory is also used as a theoretical foundation for the sociological study of deviance and crime. This approach frames deviant behavior and crime as the result of social, political, economic, and material conflicts in society. It can be used to explain why some people resort to criminal trades simply in order to survive in an economically unequal society.

Finally, labeling theory serves as an important frame for those who study deviance and crime. Sociologists who follow this school of thought would argue that there is a process of labeling by which deviance comes to be recognized as such. From this standpoint, the societal reaction to deviant behavior suggests that social groups actually create deviance by making the rules whose infraction constitutes deviance, and by applying those rules to particular people and labeling them as outsiders. This theory further suggests that people engage in deviant acts because they have been labeled as deviant by society, because of their race, or class, or the intersection of the two, for example.

Updated by Nicki Lisa Cole, Ph.D.

- Sutherland's Differential Association Theory Explained

- Sociologists Take Historic Stand on Racism and Police Brutality

- What Sociology Can Teach Us About Thanksgiving

- Studying Race and Gender with Symbolic Interaction Theory

- What Is Feminism Really All About?

- What Makes Christmas So Special

- Conflict Theory Case Study: The Occupy Central Protests in Hong Kong

- Why We Selfie

- How to Tell If You've Been Unintentionally Racist

- What's the Difference Between Prejudice and Racism?

- The Critical View on Global Capitalism

- How to Be an Ethical Consumer in Today's World

- How Sociology Can Prepare You for a Career in Business

- Full Transcript of Emma Watson's 2016 U.N. Speech on Gender Equality

- Understanding Segregation Today

- Everything You Need to Know About Anti-Vaxxers

The Sociology Guy

Helping students understand society

The content checklist for what you need to know for the crime and deviance module can be downloaded from the link below. some of the key debates that you need to be aware of are shown in the title image, but can be downloaded in pdf format as well from the link below.

Crime Checklist

Crime and deviance is one of the core modules on the AQA A level Sociology specification. Examining theories of crime, deviance, social control and social order is one of the first stages of gaining an understanding into why people commit crime, what crime does to society and how people’s behaviours are controlled by social institutions. The first gallery focuses on Functionalist and subcultural theories of crime and deviance.

These can also be downloaded as pdfs to stick into your notes. Just click on the links below:

The next gallery focuses on the different Marxist and Neo-Marxist theories of crime and deviance – focusing on capitalism as a cause of crime, the ideological functions of crime and the role of the ruling class in making the laws and enforcing the laws.

These theories can also be downloaded as pdf files to put in your notes:

The content below is from previous years and will be uploaded to REVISION as this page continues to be updated throughout the academic year

8 Great – Crime and Media

5 reasons – white collar crime

5 reasons for working class crime

5 reasons for Green Crime

5 reasons for cyber crime

Functions of Crime

Share this:

The Functionalist Perspective on Crime and Deviance

Table of Contents

Last Updated on June 5, 2024 by Karl Thompson

The Functionalist perspective on crime and deviance starts with society as a whole. It seeks to explain crime by looking at the nature of society, rather than at individuals. Most functionalist thinkers argue that crime contributes to social order, even though it seems to undermine it.

This post provides a summary of Durkheim’s Functionalist Theory of why crime is inevitable and functional for society. It then looks at some other Functionalist theories of crime and finally evaluates.

Durkheim: Three Key Ideas About Crime

Crime is inevitable.

Durkheim argued that crime is an inevitable and normal aspect of social life. He pointed out that crime is inevitable in all societies, and that the crime rate was in fact higher in more advanced, industrial societies.

Durkheim theorised crime was inevitable because not every member of society can be equally committed to the collective sentiments (the shared values and moral beliefs of society). Since individuals are exposed to different influences and circumstances, it was ‘impossible for them to be all alike’ and hence some people would inevitably break the law.

A good example of this are the laws surrounding grass cutting in many towns in America. These laws stipulate a maximum grass height, typically of eight inches. If the grass grows above this, the local council may fine them, and they can even go to jail. Some people have been fined thousands of dollars for letting their lawns grow too long .

Crime Performs Positive Functions

Social regulation.

Crime performs the function of social regulation by reaffirming the boundaries of acceptable behaviour.

In effect, the courts and the media are ‘broadcasting’ the boundaries of acceptable behaviour, warning others not to breach the walls of the law (and therefore society)

Social Integration

Social change.

Durkheim further argued deviance was necessary for social change to occur because all social change began with some form of deviance . In order for changes to occur, yesterday’s deviance becomes today’s norm .

Too much Crime is Dysfunctional

Durkheim’s view of punishment.

Durkheim suggested that the function of punishment was not to remove crime from society altogether, because society ‘needed’ crime. The point of punishment was to control crime and to maintain the collective sentiments. In Durkheim’s own words punishment ‘serves to heal the wounds done to the collective sentiments’.

More Functionalist Perspectives on Crime and Deviance

Some other functionalist sociologists have developed Durkheim’s theory of crime, applying it to specific crimes.:

Daniel Bell showed that racketeering provided ‘queer ladders for success’ and political and social stability for workers labouring in the New York docks (1960);

Evaluation of the Functionalist View of Crime

In defence of functionalism…., functionalism and crime: faqs.

Durkheim argued that crime was inevitable because societies could never fully constrain individual freedom. This freedom meant some individuals were always going to be criminal. Durkheim argued crime performed three positive functions: it allowed social change to occur, and it resulted in social regulation and social integration.

Revision Bundle for Sale

It contains

Related Posts

Sources used to write this post.

Liebling , Maruna and McAra (2023) The Oxford Handbook of Criminology

Share this:

2 thoughts on “the functionalist perspective on crime and deviance”, leave a reply cancel reply, discover more from revisesociology.

7.3 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime

Sociologists have tried to understand why people engage in deviance or crime by developing theories to help explain this behavior. It is important to note that these theories focus primarily on why people engage in crime, why some behaviors are defined as criminal while others aren’t, and how people learn criminal behavior rather than on deviance more broadly. The focus of these theories reflects that society is much more concerned about crime than people who break other kinds of social or cultural norms.

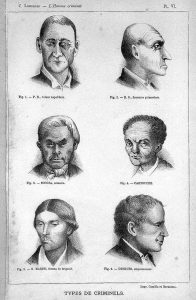

7.3.1 Historical Theories of Deviance

Inspired by Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species , early scholars trying to explain crime turned to the concept of evolution to understand differences among humans by claiming physical features were identifying markers of criminals. Several characteristics were said to indicate criminality, including skull shape, size, body type, and facial features. For example, Cesare Lombroso (1911), the father of positivist criminology, claimed that criminals were evolutionary throwbacks. He claimed that criminals can be identified by their abnormal apelike facial and physical features. A visual depiction of these features can be seen below in figure 7.4 .This school of thought is closely associated with the eugenics movement, discussed more in-depth in Chapter 11 . These theories were quickly disproven and have received harsh critiques for their blatantly racist foundation.

7.3.1.1 Durkheim and Functionalism

Émile Durkheim believed that deviance is a necessary part of a successful society. One way deviance is functional, he argued, is that it challenges people’s present views (1893). For instance, Colin Kaepernick taking a knee during the national anthem to protest police violence challenged people’s ideas about racial inequality in the United States. Moreover, Durkheim noted, when deviance is punished, it reaffirms currently held social norms, which also contributes to society (1960[1893]). Seeing a student given detention for skipping class reminds other high schoolers that playing hooky isn’t allowed and that they, too, could get detention.

Durkheim’s point regarding the impact of punishing deviance speaks to his arguments about law. Durkheim saw laws as an expression of the collective conscience, which are the beliefs, morals, and attitudes of a society. He discussed the impact of societal size and complexity as contributors to the collective conscience and the development of justice systems and punishments. In large, industrialized societies that were largely bound together by the interdependence of work (the division of labor), punishments for deviance were generally less severe. In smaller, more homogeneous societies, deviance might be punished more severely.

Modern theories have a few significant critiques of Durkheim’s perspective on crime. Sociologists have critiqued Durkheim’s argument that deviance is functional for not being generalizable to all crimes. For instance, it can be hard to argue that murder is functional for society solely because it reaffirms currently held social norms. Moreover, the idea that law is an expression of collective consciousness has also been critiqued. Conflict theorists argue that the bourgeois or elite have significant influence over political and legal institutions, allowing them to pass laws that benefit their interests and avoid harsh punishments when they commit crimes. This challenges the idea that the law reflects what society thinks is just or right.

7.3.1.2 Social Disorganization Theory

Developed by researchers at the University of Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s, social disorganization theory asserts that crime is most likely to occur in communities with weak social ties and the absence of social control.

Some research supports this theory. Even today, crimes like theft or murder are more likely to occur in low-income neighborhoods with many social problems. Still, a critique of this research is that many of these studies rely on official crime rates, much of which reflect police surveillance rather than actual crime rates. For this reason, social disorganization theory does not adequately explain white collar crimes committed by individuals living in wealthy neighborhoods, such as financial fraud or insider trading. Similarly, research from a social disorganization theory often uses circular logic: an area with a high crime rate is assumed to signal a disorganized neighborhood, leading to a high crime rate (Bursik 1988).

7.3.1.3 Cultural Deviance Theory

Cultural deviance theory suggests that conformity to the prevailing cultural norms of lower-class society causes crime. Researchers Clifford Shaw and Henry McKay (1942) studied crime patterns in Chicago in the early 1900s. They found that violence and crime were at their worst in the middle of the city and gradually decreased the farther someone traveled from the urban center toward the suburbs. Shaw and McKay noticed that this pattern matched the migration patterns of Chicago citizens. As the urban population expanded, wealthier people moved to the suburbs and left behind the less privileged. Shaw and McKay concluded that socioeconomic status correlated to race and ethnicity resulted in a higher crime rate.

This theory has many similar critiques to social disorganization theory, as they were developed around the same time and strongly emphasize the role of the environment on crime and deviance. One other critique of cultural deviance theory is that while it attributes crime to lower class cultures and values, there is no substantial evidence that these attitudes are limited to people in this class.

7.3.2 Modern Theories of Deviance

In response to the historical theories of deviance, new theories emerged that critiqued or expanded upon them to address shortfalls in their explanations. At the end of this section, figure 7.6 summarizes these key theories.

7.3.2.1 Robert Merton’s Strain Theory: Rethinking Durkheim

Sociologist Robert Merton agreed that deviance is an inherent part of a functioning society, but he expanded on Durkheim’s ideas by developing strain theory , which notes that access to socially acceptable goals plays a part in determining whether a person conforms or deviates. Merton defined five ways people respond to this gap between having a socially accepted goal and having no socially accepted way to pursue it. To understand the five ways people respond, we’ll look at the example of the American Dream: the idea that to be successful, you should own a house, car, and have a happy and functional family.

Example: “I may not be able to afford to buy a house in my lifetime, but I have a working car, a loving partner, and a cute dog. I’m content with the lot I’ve been given in life.”

Example: “I grew up in a neighborhood that didn’t have good schools, and I never had an opportunity to get ahead. I want a house, nice car, and to take care of my family, but the only way I can see myself doing that is by continuing to sell cocaine and counterfeit goods.”

Example: “I’m never going to be able to afford a nice home and car, but I don’t need those things anyways! I like the apartment I rent, and my cat’s only other form of life I want to be responsible for. Why not just love the things that I do have?”

Example: “ Why would I even participate in society at all? The deck is stacked against me. I know I’m only 20, but (illegally) hopping on trains and travelling around the country with my friends is where it’s at! ”

Example: “I’m gonna overthrow the government, that’s what I’m going to do! The system is unjust and it’s not one that’s designed for how humans really are!”

7.3.2.2 William Julius Wilson: Rethinking the Role of Neighborhoods

William Julius Wilson refined ideas in social disorganization theory to explain why people in poverty, particularly those living in black and immigrant communities, are more likely to live in high-crime neighborhoods. Rather than focusing on the role of cultural factors like previous theorists, Wilson (1987) focused on how economic changes have contributed to these groups being more likely to live in high-crime neighborhoods.

Wilson (1997) argued that before the decline of industrial and manufacturing jobs, these groups could be economically successful despite having low levels of education given their access to high paying factory jobs. After manufacturing jobs left these cities, black people and recent immigrants became trapped in low-income high-crime areas with few jobs or low-wage, service sector jobs. According to Wilson’s (1997) theory, crime emerges because policy leads to little economic opportunity and traps disadvantaged groups in poor, high-crime areas where turning to crime is one of the few opportunities for advancement.

7.3.2.3 Karl Marx’s Unequal System Theory

Karl Marx believed that the bourgeoisie centralized their power and influence through government and law. Though Marx spoke little of deviance, his ideas created the foundation for other theorists who study the intersection of deviance and crime with wealth and power. Later Marxists, such as Richard Quinney (1974), expanded upon these ideas. He believed that the bourgeoisie set up laws to maintain their class rankings rather than to reduce crime. Similarly, he argued that the legal system is uninterested in addressing the root causes of crime. Instead, the legal system is preoccupied with controlling the lower class.

7.3.2.4 C. Wright Mills’ Power Elite Theory

Power Elite theory differs from unequal system theory in that it further refines the ideas of unequal system theory. It more clearly specifies which actors influence laws, rather than broadly characterizing the bourgeois as having this power. Still, many similarities exist between the two theories in that they both look at how the groups in power exploit their influence for their benefit at the expense of marginalized populations.

In his book The Power Elite (1956), sociologist C. Wright Mills described the existence of what he dubbed the power elite, a small group of wealthy and influential people at the top of society who hold the power and resources. Wealthy executives, politicians, celebrities, and military leaders often have access to national and international power, and in some cases, their decisions affect everyone in society. Because of this, the rules of society are stacked in favor of a privileged few who manipulate them to stay on top. It is these people who decide what is criminal and what is not, and the effects are often felt most by those who have little power.

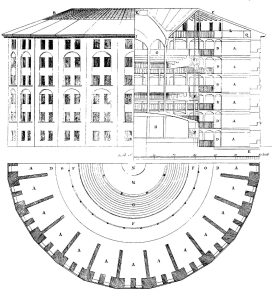

7.3.2.5 Michele Foucault: Discipline and Punishment Theory

The panopticon, as seen below in figure 7.5, is a late eighteenth century circular prison designed by philosopher Jeremy Bentham. In the panopticon prison design, guards could continuously monitor prisoners without the prisoners knowing if guards were watching. Since prisoners would not know when guards were watching them, they would constantly surveil their behavior to avoid punishment. French philosopher Michele Foucault (1977) drew parallels between Jeremy Benthan’s panopticon and how modern institutions control the population. He argued that punishment currently occurs through discipline and surveillance by institutions, such as prisons, mental hospitals, schools, and workplaces. These institutions produce compliant citizens without the threat of violence.

Ultimately, Foucault (1977) argued that surveillance created an effect where individuals conformed to society since they never knew if they were being watched. His ideas have gained new importance with the rise of surveillance technologies, which make it harder to engage in deviance without getting caught. Examples of this phenomenon are federal mass surveillance policies and the rise of police departments using technologies to scour social media networks for information about criminal activities. Broadly, Foucault (1977) proposed that social control and punishment are not just formal sanctions, like a prison sentence or ticket, but also something more mundane and built into social institutions.

7.3.2.6 Lemert’s Labeling Theory

Rooted in symbolic interactionism, labeling theory examines the ascribing of a deviant behavior to another person by members of society. What is considered deviant is determined not so much by the behaviors themselves or the people who commit them, but by the reactions of others to these behaviors. As a result, what is considered deviant changes over time and can vary significantly across cultures.

Sociologist Edwin Lemert expanded on the concepts of labeling theory and identified two types of deviance that affect identity formation. Primary deviance is a violation of norms that does not result in any long-term effects on the individual’s self-image or interactions with others. Speeding is a deviant act, but receiving a speeding ticket generally does not make others view you as a bad person, nor does it alter your own self-concept. Individuals who engage in primary deviance still maintain a feeling of belonging in society and are likely to continue to conform to norms in the future.

Sometimes, in more extreme cases, primary deviance can morph into secondary deviance . In secondary deviance a person may begin to take on and fulfill the role of a “deviant” as an act of rebellion against the society that has labeled that individual as such. In many ways, secondary deviance is captured by the phrase, “If you tell a child enough that they’re a bad kid, they’ll eventually believe that they’re a bad kid.” This perspective hits on how negative social labels, especially of juveniles, have the power to create more deviant or criminal behavior.

7.3.2.7 Sykes and Matza’s Techniques of Neutralization

How do people deal with the labels they are given? This was the subject of a study done by Gresham Sykes and David Matza (1957). They studied teenage boys who had been labeled as juvenile delinquents to see how they either embraced or denied these labels. They argued that criminals don’t have vastly different cultural values but rather adopt attitudes to justify criminal behavior at times. Sykes and Matza developed five techniques of neutralization to capture how people justify engaging in criminal acts. Individuals may not necessarily internalize labels if they have developed strategies to reject associating their actions with these labels.

Let’s apply each of these techniques by pretending to be a teenager justifying shoplifting at a major retail chain department store. From this example, we can see how individuals can justify engaging in an act that may be illegal and violates social norms through these kinds of cognitive strategies

Example: “I don’t want to steal from this store, but I’ve applied to so many jobs and no one seems to want to hire a teenager these days.”

Example: “It’s not like anyone is being hurt by me stealing.”

Example: “Who am I hurting anyways? This is a big corporation! They expect some level of theft.”

Example: “This corporation is way more corrupt considering the fact most of their goods come from sweatshops where there is child labor.

Example: “I’m only stealing because I really don’t have enough money to get my sister a nice birthday present and she matters way more to me than any stupid corporation does. I’m a modern day Robin Hood.”

7.3.2.8 Sutherland’s Differential Association Theory

In the early 1900s, sociologist Edwin Sutherland sought to understand how deviant behavior developed among people. Since criminology was a young field, he drew on other aspects of sociology including social interactions and group learning (Laub 2006) and the work of George Herbert Mead, whose ideas are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 4 . His conclusions established differential association theory , which suggested that individuals learn deviant behavior from those close to them who provide models of and opportunities for deviance.

According to Sutherland, deviance is less a personal choice and more a result of differential socialization processes. He argues that people learn all aspects of criminal behavior through interacting with others and being part of intimate personal groups. Sutherland’s theory captures not only how people learn criminal behavior, but also how people learn motives, rationalizations, and attitudes towards crime. Differential association theory also demystifies crime, conceptualizing it as a behavior just like any other: a radical departure from early theories of crime that viewed criminals as inherently biologically different or all individuals as naturally pleasure seeking, selfish, and prone to crime. In Sutherland’s theory, anyone has the potential to engage in crime if they learn how to commit crime and embrace favorable definitions of crime. This theory also helps explain why not all children who grow up in poverty end up engaging in criminal activity—as historical theories such as cultural deviance theory suggest—because they encounter different situations that shape their definitions towards violating the law.

| Theory | Associated Theorist | Contribution to the Study of Deviance and Crime |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Association Theory | Edwin Sutherland | Argues that deviance arises from learning and modeling deviant behavior seen in other people close to the individual |

| Discipline and Punishment Theory | Michel Foucault | Highlights how social control mechanisms are not just formal sanctions, but also built into modern institutions |

| Labeling Theory | Edwin Lemert | Argues that deviance arises from the reactions of others, particularly those in power who are able to determine labels |

| Power Elite Theory | C. Wright Mills | Argues that deviance arises from the ability of those in power to define deviance in ways that maintain the status quo |

| Revised Social Disorganization Theory | William Julius Wilson | Argues that crime emerges because policy leads to little economic opportunity and traps disadvantaged groups in poor, high crime areas where turning to crime is one of the few opportunities for advancement |

| Strain Theory | Robert Merton | Argues that deviance arises from a lack of ways to reach socially accepted goals by accepted methods |

| Techniques of Neutralization | Gresham Sykes and David Matza | Developed five techniques of neutralization to capture how people justify engaging in criminal acts |

| Unequal System Theory | Karl Marx | Argues that deviance arises from inequalities in wealth and power that arise from the economic system |

Figure 7.6. Modern Theories of Deviance and Crime

7.3.3 Licenses and Attributions for Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime

“Durkheim and Functionalism” paragraphs 1 and 2 edited for clarity and brevity are from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime

“Social Disorganization Theory” paragraph 1 edited for clarity and brevity is from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime

“Cultural Deviance Theory” paragraph 1 is from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance” by Heather Griffiths and Nathan Keirns in Openstax Sociology 2e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance

“Robert Merton’s Strain Theory: Rethinking Durkheim” modified from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime

“Karl Marx’s Unequal System Theory” modified from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime

“C. Wright Mills’ Power Elite Theory” paragraph two edited for clarity and brevity from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime

“Lemert’s Labeling Theory” paragraphs 1 and 2, and sentences 1 and 2 in paragraph 3 edited for clarity and brevity from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime

“Sutherland’s Differential Association Theory” modified from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime

Figure 7.4. Plate 6 of L’Homme Criminel by Cesar Lombroso, Public domain , via the Wellcome Collection .

Figure 7.5. Jeremy Bentham, Panopticon Prison Design, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons .

Figure 7.6 is from “7.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance and Crime” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang in Openstax Sociology 3e , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/7-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-deviance-and-crime . Substantial modifications and additions have been made.

All other content in this section is original content by Alexandra Olsen and licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

Sociology in Everyday Life Copyright © by Matt Gougherty and Jennifer Puentes. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

Social Construction of Crime & Deviance

Charlotte Nickerson

Research Assistant at Harvard University

Undergraduate at Harvard University

Charlotte Nickerson is a student at Harvard University obsessed with the intersection of mental health, productivity, and design.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Social construction of crime and deviance is the theory that behaviors and actions are not inherently criminal, but are labeled deviant by those in power within a social context. What a society defines as deviant depends on norms, values, and interests of the powerful and privileged at a particular time and place.

Key Takeaways

- Social constructionism holds that the meaning of acts, behaviors, and events is not an objective quality of phenomena but one assigned to them by people through social interactions . Shifts in public perception can lead to an act taking on a different meaning than it once had.

- Spector and Kitusee introduced the idea of social constructionism into criminality.

- Social constructionism can influence whether or not something is seen as a crime, its severity, and the extent to which it is feared. How societies define and remedy crime is the outcome of numerous complex factors between different groups of actors.

- Sociologists can study crime on a systematic level, as well as through an examination of public reaction and the crimes themselves.

- There are numerous examples of crimes that were once considered not to be social problems, and actions that were once illegal that are now not widely considered to be crimes. For example, various laws have been created and nullified against homosexuality, bullying, and drug use depending on public perception.

Is Crime Socially Constructed?

Behaviors become crimes through a process of social construction . While a behavior may be considered criminal in one society, it may be considered benign, or even honorific, in another.

Thus, sociologists consider whether or not a behavior is defined as a crime to depend on the social response to the behavior or the persons who engage in it, whether in the content of the behavior itself.

The social response to crime is based not only on the qualities of the act but also on the social and moral standing of the offender and the victim. Theories of crime are ancient. Plato put forward theories of punishment.

An influential and infamous text published in Nuremberg in 1494 detailed the types of witches, as well as procedures for torture and extermination. However, the history of modern criminology is widely considered to have begun with the work of Cesar Beccaria, who published Essays on Crime and Punishment in 1764.

Sociologists have presented the most successful theories of crime (Heidensohn, 1989). In essence, sociologists see crime as a socially situated and defined problem (Morris and Tonry, 1980).

Overview of Social Constructionism

Social constructionism holds that the meaning of acts, behaviors, and events is not an objective quality of those phenomena but is assigned to them through social interactions.

In this view, meaning is socially defined and organized and thus subject to social change.

Spector and Kitsuse (1973) introduced social constructionism into the vocabulary of social problems theory – otherwise known as criminology (Schneider, 1985).

From the social constructionist perspective, any given behavior becomes a social problem through social movements or groups successfully convincing the general public that a phenomenon is a problem and advocating for a particular response to that problem.

Defining Crime

Early sociologists such as Paul Tappan (1947) defined crime as all actions in “violation of the criminal law.” However, this approach gave rise to many problems.

Criminal laws are not fixed or permanent in any society. The formal limits of criminal law can be shifted by many different social pressures. For example, in the 20th century, many countries removed sanctions against abortion under certain conditions.

Class and power have also influenced the scope of criminal law (Hay, 1975). In the first decades of the 20th century, middle-class American women and other anti-alcohol groups combined to introduce prohibition.

If criminal laws constitute the norms for behavior in a society, they must change to reflect social changes. This change can be technological in nature. For instance, the proliferation of car ownership has provided new opportunities for criminal behavior, such as causing death by reckless driving.

This has been accompanied by a host of laws regarding the speed, use, and parking of vehicles (Heidensohn, 1989). Crimes can also have different levels of severity, and be completely unrelated. The severity of crimes can also be subjective.

A starving person stealing a loaf of bread would be, in many eyes, a lesser crime than stealing luxurious mink coats intending not to pay for them (Heidensohn, 1989).

How Crimes Become Crimes: Complexity and Interaction

What is taken to be called crime is the outcome of a large number of complex interactions and negotiations between different groups of actors (Gibbons, 1968).

Records about the people who commit crimes, as many crimes have unknown perpetrators. Further, these so-called clear-up rates can vary — while most homicides result in an offender being found, most burglaries are left unsolved (Kinsey et al., 1986).

For sociologists, this means that concepts of crime — and deviance, for that matter, will likely remain both arbitrary and contested (Crime and Societal; Becker, 1963).

Researchers have studied what causes fear of crime, suggesting that the fear of crime in itself is a product of the relations between social vulnerability, perceived and actual, and the risks of victimization (Maxfield, 1984; Smith, 1986; Jones, 1987).

Crime can be examined as a social phenomenon on at least three levels. It can be studied systematically, using concepts, theories, and available data to test ideas.

Public reaction can also provide another level to studying crime, as it plays an important part in shaping responses to crime — and even crime itself. Finally, sociologists can study the phenomenon of crime itself.

Face Coverings (Coronavirus: The Lockdown Laws)

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, face coverings were not commonly worn by members of the public in most Western countries. However, as COVID-19 became a major public health issue, public perception shifted.

Not wearing a face mask, particularly in crowded indoor areas such as subways and grocery stores, began to be seen as reckless to both one’s own health and the health of others.

Eventually, municipalities, as well as national-level governments, began to enforce laws around wearing face masks in public, in some cases enforcing what types of face coverings needed to be worn.

Those who did not comply with these regulations risked denial of entry, fines, or, in rare cases, arrest.

Although there was push-back against wearing face masks by certain segments of the public, not wearing a face covering largely went from being seen as normal to between irresponsible and endangering in the public eye. Quickly, public perception shifted in favor of wearing face masks.

The War on Drugs

The spring of 1986 to 1992 saw a widespread push to solve the problem of drug use, especially crack cocaine. Politicians from both American political parties made increasingly strident calls for a “War on Drugs” (Reinarman and Levine, 1995).

Reinarmean and Levine note several reasons why crack cocaine in particular sparked the war on drugs. In 1985, the National Institute on Drug Abuse noted that, while more than 22 million Americans had tried cocaine, all phases of drug use tended to take place in the privacy of the homes and offices of middle and upper-class users.

In 1986, however, cocaine spread visibly to the lower classes, with increased visibility in ghettos and barrios. Crack was sold in small, cheap units on ghetto streets to poor, young buyers who were already seen as a threat.

During this time, politicians and the media depicted crack as “supremely evil — the most important cause of America’s problems”. This was surrounded by the political context of the emergence of a heavily fundamentalism-influenced new right republican party and competition between both political parties to be seen as “harder on drugs.”

All in all, the war on drugs resulted in the rejection of syringe distribution and exchange programs implemented in other countries to reduce AIDS prevalence, greatly stigmatized drug users, and resulted in the imprisonment of many, disproportionately from the lower classes, for drug-related crimes.

The Sociology Teacher

CRIME & DEVIANCE

The 'nutshells' provide concentrated summaries. use the arrows or swipe across to explore topics in more detail, including key perspectives and sociologists ..

Want a more engaging way of revising key terms and sociologists? Download our revision app from the App Store!

Topic 1 - Functionalism & CRIME

In a nutshell

Functionalists believe that crime is inevitable in society; poor socialisation and inequality result in the absence of norms and values being taught. In addition, functionalists believe crime is positive for society because it allows boundary maintenance, and allows a scope for adaptation and change.

Topic 2 - Interactionism theory

Interactionists focus on the social construction of crime, whereby an act only becomes deviant when labelled as such, through societal reaction. However, not every deviant act or criminal is labelled, and labelling theory is selectively enforced against some groups. Some sociologists believe labelling may cause an individual to be defined a master status.

Topic 3 - Class, Power & Crime

Marxists believe crime is inevitable in a capitalist society because it encourages poverty, competition and greed. Although all classes commit crime, the working class are largely criminalised for their actions because the ruling class control the state and can make and enforce laws in their own interests. In this instance, white collar and corporate crimes are often ignored.

Topic 4 - Realist Approaches TO Crime

Right realists see crime as a real problem for society; they see the cause of it as partly biological and party social. Because these causes cannot easily be changed, they focus on deterring offenders. Left realists, on the other hand, believe crime is caused by relative deprivation, subcultures and marginalisation. Their solution for such stems from reducing societal inequality.

topic 5 - GENDER AND CRIME

Official statistics show men commit more crime than women, however sociologists disagree on the reasons why. Some sociologists argue female offending rates go unnoticed and unpunished because the criminal justice system treats women more leniently, through ideas such as the chivalry thesis (Pollak). However, some sociologists believe the gender differences in offending are due to the way women are socialised meaning they have less opportunity or desire to commit crime. On the other hand, other sociologists argue women do commit crime, but men merely commit more due to the idea of ‘masculinity’.

topic 6 - ethnicity and crime

Official statistics highlight that black people are more likely to be stopped, arrested and imprisoned. Some sociologists argue this is because they are more likely to offend, due to poor educational achievement, dysfunctional family structure and racist stereotypes portrayed in the media. However, some sociologists they merely appear more criminal due to discrimination in wider society.

topic 7 - MEDIA AND CRIME

The media give an overly distorted image of crime - for instance, by over-representing violent crimes. This is because the news is a social construction based on news values that explain the media's interest in crime. Some sociologists see media as a cause of crime through imitation and the deviance amplification of moral panics.

topic 8 - GLOBALISATION, GREEN CRIME & STATE CRIME

Globalisation has allowed transnational organised crime to flourish - for instance, the trafficking of arms, drugs and people. We now live in a global risk society where human-made threats include large environmental damage. Green criminology adopts an ecocentric view based on harm rather than the law, and identified both primary and secondary green crimes. The state also contributes to green crime through the exploitation of health and safety laws, for example.

topic 9 - CONROL, PUNISHMENT & VICTIMS

Sociologists believe that the ability to control criminal behaviour takes several different measures - notably, it is targeted at situational crime prevention and environmental crime prevention. In addition, surveillance is another method used to control and punish criminals. Sociologists also focus on victimisation, in which positive victimology focuses on victim proneness or precipitation, whilst critical victimology emphasises structural factors such as poverty.

Crime and Deviance Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Sociological perspective.

Deviance is an act perceived to be against one cultural belief and the act cannot be tolerated. Deviance acts are different from one community to another and also can vary depending on generational time.

For example, the homosexuality is allowed in American society, but in Africa the act is seen as satanic and can make the victims to be stoned to death. In some decades ago, divorce was seen to be against the rule of the church society, but with modernization, divorced has grown to be accepted as part of marriage life (Lukes 28).

Crime is an act that is against the norm of a society and the registered law of the entire country. If a person breaks a certain section of a country law, there is a correction sanction to that person. A person is usually taken to the court of law where the offence is listened to, by the judge and the person is either proven guilty or innocent.

A criminal can be put in jail for some time or for life, sentenced to death and even pay some money as a penalty (Lukes 28). A country law which is constitution is mostly formed by the parliament of that country.

Introduction . Sociologists have tried to understand crime and deviance in different ways. Most of the ancient sociologists have come up with different sociological perspectives that try to explain crime and deviance.

Emile Durkheim came up with rule of sociological methods that explained crime as part of society norms. Durkheim believed crime to be higher in modernized and industrialized society as compared to less modernized. In industrialized society, division of labor is the norm of life and each person is exposed to different work experiences (Moyer 54).

Division of labor exists in two ways, one is mechanical solidarity whereby the members of the society are similar and the organic solidarity in which society members creates a relationship among themselves through the division of labor. As in the division of labor, society people have different influences and situational experiences that distinguish one person from the other.

The personal differences make some people to be criminals and other to be good. No society lacks deviance or crime however perfect it could be. Every community has norms and traditions that put the members together and if the norms are broken, there is state of anomie and lawlessness.

Advantages of the perspective . Durkheim argued that besides division of labor helping to make production rise and improve the human capital it also possessed a moral character that created a sense of solidarity in humans. He explained with a married couple arguing that sexual desire would only exist after the material life has disappeared if the division of labor was to be reduced between the marriage partners.

Durkheim suggested that division of labor has more of social and moral order therefore married couple is bided by their common things they do. Durkheim saw that crime was beneficial to the society in some instances. Crime builds future morality by showing what law is to be followed.

For example a committed crime will lead to establishment of an order that will be followed by the people to avoid repetition of the same crime. Crime corrections or rewards were put not to punish a criminal and make the person stop the crime, but the punishment was to strengthen the entire law to help control crime. Durkheim saw that punishment and crime go together and cannot be separated (Marsh 98).

Drawbacks of the perspective . Crime is has negative impacts and dangerous to the people and the community at large if is at high levels. If crime is not controlled and increases more and more each day, the society can be unable to prevent the criminals. On the other hand, if the crime rate is too low, the society maybe abnormal.

According to Durkheim the breaking of the society way of living or the norms is what brings in the social change which is very important in community development. Otherwise the social change should be controlled or moderate to avoid social problem. In any case the deviance which motivate the social change should be regulated so that to prevent the loss of criminal identity which it is important in the future (Marsh 95).

Durkheim failed to explain how for example division of labor would be used to control crime in the society. Also not all crimes would be beneficial to the society because if a crime resulted to killing or a big damage then the society will drag behind on development.

Lukes, Steven. The rules of the sociological method . New York: Free press, 2007.

Marsh, Ian., Melville, Gaynor. Theories of crime . Canada: Routledge, 2006

Moyer, Imogene. Criminological theories: traditional and non traditional voices . London: sage publishers, 2001.

- Importance of Adopting Children

- Banning Violent Video Games Argumentative Essay

- Marxists and Functionalists' Views on Crime and Deviance

- Durkheim’s Methodology and Theory of Suicide

- Emile Durkheim's Theories

- Stereotypes of American Citizens

- Social Care in Ireland

- Evaluating the debate between proponents of qualitative and quantitative inquiries

- The Effects of Social Networking Sites on an Individual's Life

- Parenting's Skills, Values and Styles

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, May 29). Crime and Deviance. https://ivypanda.com/essays/crime-and-deviance/

"Crime and Deviance." IvyPanda , 29 May 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/crime-and-deviance/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Crime and Deviance'. 29 May.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Crime and Deviance." May 29, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/crime-and-deviance/.

1. IvyPanda . "Crime and Deviance." May 29, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/crime-and-deviance/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Crime and Deviance." May 29, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/crime-and-deviance/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.