Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 17 January 2023

A mixed-method study on adolescents’ well-being during the COVID-19 syndemic emergency

- Alessandro Pepe 1 , 2 &

- Eleonora Farina 1 , 2

Scientific Reports volume 13 , Article number: 871 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2749 Accesses

5 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health care

In this study, we set out to investigate adolescents’ levels of perceived well-being and to map how they went about caring for their well-being during the COVID-19 syndemic. Participants were 229 Italian adolescent high school students (48.9% males, mean age = 16.64). The research design was based on an exploratory, parallel, mixed-method approach. A multi-method, student-centered, computer-assisted, semi-structured online interview was used as the data gathering tool, including both a standardized quantitative questionnaire on perceived well-being and an open-ended question about how adolescents were taking charge of their well-being during the COVID-19 health emergency. Main findings reveal general low levels of perceived well-being during the syndemic, especially in girls and in older adolescents. Higher levels of well-being are associated with more affiliative strategies (we-ness/togetherness) whereas low levels of well-being are linked with more individualistic strategies (I-ness/separatedness) in facing the health emergency. These findings identify access to social support as a strategy for coping with situational stress and raise reflection on the importance of balancing the need for physical distancing to protect from infection, and the need for social closeness to maintain good mental health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

People are surprisingly hesitant to reach out to old friends

Effect of breathwork on stress and mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised-controlled trials

Introduction.

Officially declared a pandemic on 11 March 2020, the COVID-19 outbreak has resulted so far in over 550million cases and 6.3million deaths worldwide 1 . Although it appeared at the start of the pandemic that all populations around the world would be affected to the same extent, we now know that this is not the case. Indeed, while multiple sources initially claimed that "we were all in the same boat," two years after the onset of the pandemic, we are now in a position to state that "We are all on the same sea, but the boats from which we are dealing with the effects of COVID-19 are very different." Not only have the more strictly medical aspects differentially affected different populations (with the outcome of exacerbating inequalities), but the measures implemented by various governments for reducing the spread of the disease (e.g., lockdowns, restrictions on movement, school closures, and the adoption of distance education) have differentially affected different segments of the population in each country 2 .

Covid-19 from a syndemic perspective

Variability in the evidence reported in the literature regarding the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on different populations of interest and in different contexts may be explained by drawing on the concept of syndemic 3 . A syndemic is a situation in which two or more health conditions co-occur in environments of aggravated adversity and interact synergistically to yield worse health outcomes than each affliction would likely generate on its own 4 . Limiting the harms caused by COVID-19 will require paying far greater attention to so-called noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and socioeconomic inequality than has been done up to now. Although NCDs have conventionally been analyzed in relation to the risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic pulmonary diseases, and diabetes, scholars have recently emphasized 5 that cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancer, and respiratory diseases frequently co-occur with both common mental disorders (such as depression and anxiety) and severe mental illnesses (such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder). A syndemic is more than the outcome of a pandemic in terms of comorbidities; rather, it is an intertwining of biological and social conditions that increases an individual's susceptibility to harm or worsens their health outcomes. The most important implication of viewing the COVID-19 outbreak as a syndemic is that this helps to focus on its social origins. The vulnerability of younger and older citizens, ethnic minority communities, and key workers, who are frequently underpaid and enjoy less social welfare protection, points to an unacknowledged truth: no matter how effective a treatment or protective a vaccine, any exclusively biomedical solution for COVID-19 will fail.

Impact of syndemic on adolescents’ well-being and mental health

The international scientific literature presents extensive research on the effects of the syndemic on individual well-being in different age groups and based on different methods of inquiry 6 . Adolescents, although at lower risk of death or severe illness due to COVID-19 than the adult population, are still having to cope at different levels with the negative impact of the public health emergency on their mental health 7 . Among other manifestations, the literature highlights anxiety-related, depressive, psychosomatic symptoms, as well as high levels of post-traumatic stress; these symptoms are more marked in girls, older adolescents, and adolescents with pre-existing vulnerabilities 8 . A recent review of 156 studies on changes in adolescents’ mental health during the COVID-19 emergency showed that outcomes had significantly worsened in several areas 9 . Among studies of depression, some 79% of studies found that participants’ symptoms had worsened, while 76% of studies of anxiety identified a worsening of symptoms, especially in girls and young women. Similarly, 70% of the research on stress and distress observed a clear increase in these phenomena with respect to the pre-pandemic period. Also considered in the review were studies—both longitudinal and cross-sectional—that found changes in subjective well-being, quality of life, and life satisfaction: the vast majority of authors identified a worsening of these dimensions. On the other hand, contrary to fears that adolescents would engage in greater substance abuse during the COVID-19 health emergency, findings regarding the use of substances have been mixed. A recent report by the U.S. National Institutes of Health identified a sharp decline in adolescent substance use in 2021 10 . The syndemic’s impact on substance use has likely been moderated by a number of factors, including changes in the social settings in which young people normally have the opportunity to use substances. In-person social interaction was drastically reduced in many contexts, thus reducing opportunities to drink alcohol 11 . In contrast, other studies showed that young people who remained more isolated during stay-at-home regimes used more cannabis than those who continued to socialize in person 12 .

However, in relation to mental health problems, contrasting results have been found both within and between categories. The overall decline in mental health is likely related to multiple factors implicated in the COVID-19 emergency internationally, including the specifics of different socioeconomic backgrounds 13 as the concept of syndemic also reflects. Although most longitudinal studies on depression, anxiety and stress have documented an increase in symptoms over the period of the COVID-19 emergency, others have found no change or even a decrease in the incidence of these symptoms. Increases in suicide ideation and suicide attempts have been reported in several countries, but in one of the few studies conducted with a subgroup of marginalized youth, a significant reduction in episodes of self-harm was reported during the pandemic, potentially attributable to good service response 14 . Furthermore, different aspects of the syndemic setting likely generated different mental health problems. For example, a survey of U.S. students found that school-related concerns (e.g., lower quality online courses) were associated with increased depressive symptoms, while concerns related to home confinement per se (e.g., “cabin fever”) were associated with increased generalized anxiety symptoms 15 . It is also worth reporting the various studies during these syndemic years that also noted people's ability to detect positive aspects related to the emergency situation. For example, one line of research focused on the development of a form of wisdom derived from the ability to detect positive opportunities (such as spending more time with family members, developing forms of solidarity with other people) to develop new attitudes, behaviors, and values 16 . Other studies have pointed out that the emotional impact of syndemia, although predominantly characterized by emotions such as anxiety, sadness, and fear, over time also brings out positive emotions such as hope, trust, and tranquility 17 .

Maintaining personal well-being during the syndemic

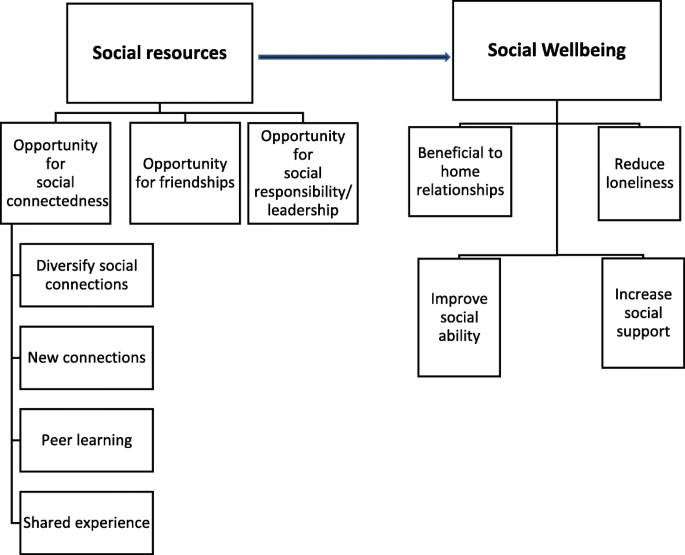

Studies that did not find significant changes in levels of well-being among youth have identified an association with the use of positive coping strategies in many cases 18 , 19 . Young people report that they used different ways to sustain resilience: in most cases, these strategies involved trying to maintain relational connections with significant others who were physically out of reach (friends and relatives), combined with more individual approaches to maintaining physical and mental well-being (exercising, spending time outdoors, meditating…).

Among the different factors that can reduce the risk of non-communicable disease during a syndemic, the literature recognizes coping strategies, along with perceived social support, as protective against the development of acute symptoms following exposure to particularly stressful events. Coping is the deployment of behavioral and cognitive strategies to modify negative aspects of one’s environment, and to minimize or escape internal threats induced by stress or trauma. Such strategies are diverse and can be more or less adaptive 20 , 21 . A more active coping style includes problem-oriented strategies, for example target the context as a means of solving difficulties, create an action plan, referring to someone, and be free to express and share feelings. Avoidance strategies include denial, substance use, and behavioral and mental detachment: trying to suppress emotions, withdrawing from people and enacting risky behaviors can be examples of avoidant coping style. Social support can be sought with a view to acquiring understanding or information or as an emotional outlet, which is a crucial resource to cope with stressful events and develop a positive attitude of acceptance, containment, and positive reinterpretation of events. In literature emerged that the use of avoidant coping strategies among adolescents was associated with overall higher levels of anxiety and depression and with other factors related to living conditions, such as having three or more siblings, having separated parents with low educational level 22 .

The restrictions imposed in the context of the COVID-19 health emergency have drastically reduced and disrupted access to many forms of social support, meaning that one coping strategy is less available or completely unavailable. However, studies show that family life during the initial severe lockdown of 2020, although it severely constrained adolescents’ drive for autonomy—hindering the fulfillment of a fundamental developmental task—acted as a key protective factor in their mental well-being 23 , 24 .

In light of the strong association between adolescents’ interactions with peers, friends, and family and their psychological well-being, it is of crucial importance to examine the factors that could further hinder or damage interpersonal interactions during this vulnerable stage of life.

The present study

In this study, we set out to investigate adolescents’ levels of perceived well-being and to map how they went about caring for their well-being during the COVID-19 syndemic. In keeping with the literature reviewed above, we hypothesized that they would have drawn on both individual and social resources to feel good and safe, as well as making novel use—and possibilities to use—of indoor and outdoor spaces. We expected that different strategies would be associated with differential levels of well-being. More specifically, we hypothesized that a strategy of seeking to maintain satisfying and supportive relationships with family and peers would foster the deployment of more proactive coping attitudes and consequently higher levels of perceived well-being. In contrast, we predicted that more individualistic and inward-looking coping strategies would be associated with a tendency toward passivity, a diminished perception of being in control of the situation, and consequent lower levels of well-being.

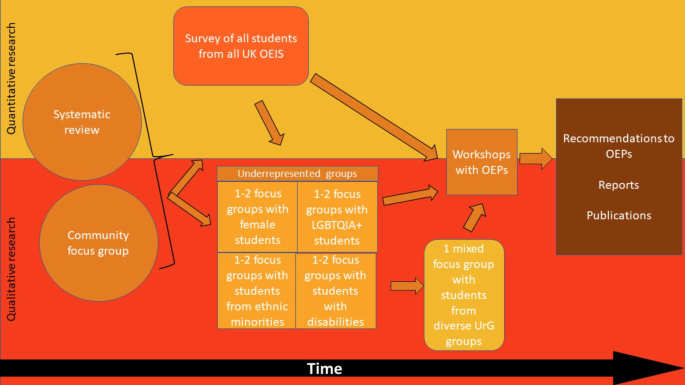

Participants were 229 Italian adolescent high school students. The sample was balanced in terms of gender, comprising 48.9% males (n = 112) and 48% females (n = 110); seven participants (3.1%) did not specify their gender. Participants’ ages ranged from 14 to 19 years ( M = 16.64, SD = 1.46). The inclusion criteria were: (1) attending high school, (2) being aged between 14 and 19 years, (3) accepting the terms of participation in the research. We did not apply any exclusion criteria. We recruited a convenience sample via a non-probability sampling technique whereby participants are selected from the population only because they agree to participate 25 . We collected the data during the period from April 2021 to June 2021.

Procedure and materials

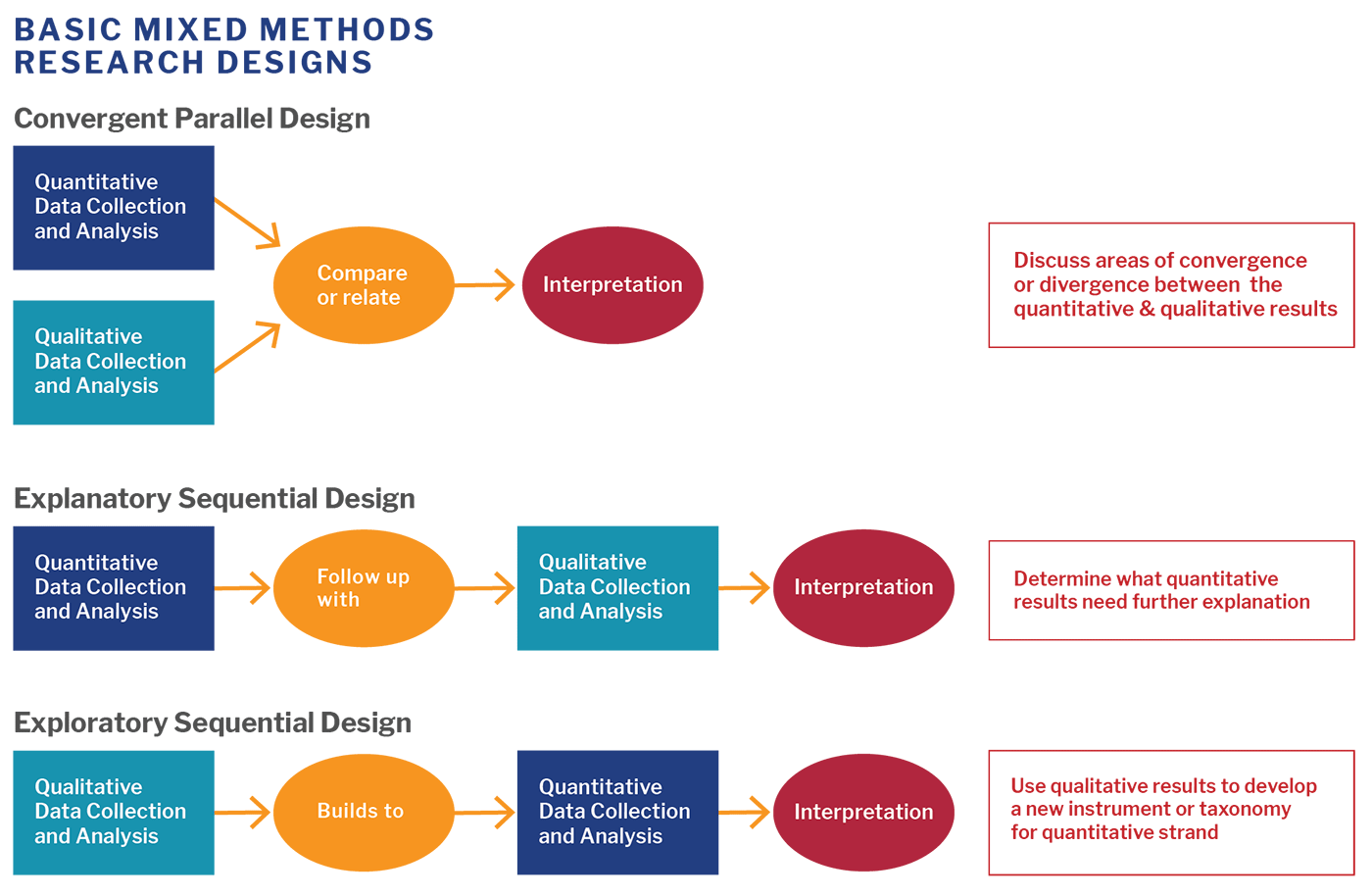

This exploratory study was underpinned by a parallel mixed-method research design 26 and its primary source of data was a multi-method, student-centered, computer-assisted web interview (CAWI) 27 , 28 . The research protocol comprised three main sections: (1) demographic background, (2) closed items about well-being, (3) two open-ended question about being an adolescent during the COVID-19 public health emergency (“At this time, what are the times, situations, or events that help you feel good?” and “If you were to describe, using a phrase, image, or metaphor, what it is like to be a girl/boy of your age these days, what would you write?”). With regards to demographic data, the research plan included age and gender as variable of interest since the study was exploratory and used a convenience sample. Data were collected anonymously, and all participants were briefed about the research aims and procedure. Participation in the study was on a voluntary basis, meaning that participants received no monetary or financial rewards. The study was approved by the Ethics Board at Milano-Bicocca University (prot. N. 0059806/21) and was conducted in keeping with the ethical principles laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki 29 and the American Psychological Association code of conduct 30 . Informed consent was obtained from all participants and from parents for underage participants. During data collection (i.e., April to June 2021, a zoning policy was still in effect, based on the rate of contagion, while secondary school students were attending in-person classes 50% to 100% of the time, depending on the zone and the internal organization of schools.

World Health Organization Well-Being Index (WHO-5) The five-item World Health Organization Well-Being Index (WHO-5) is a short rating scale measuring global subjective well-being 31 . The instrument has been used in many different settings to assess positive well-being and as a proxy for mental health 32 . The questionnaire items are: (1) ‘I have felt cheerful and in good spirits’, (2) ‘I have felt calm and relaxed’, (3) ‘I have felt active and vigorous’, (4) ‘I woke up feeling fresh and rested’ and (5) ‘My daily life has been filled with things that interest me’. Respondents rate each item on a Likert scale ranging from 5 (all of the time) to 0 (none of the time). The raw WHO-5 scores are computed by summing the scores for the individual items, yielding global scores ranging from 0 (no well-being) to 25 (maximal well-being) which are then conventionally converted to a scale of 0–100. A generally accepted threshold for poor well-being and the risk of developing depressive symptoms is less than 50 33 . In this study, Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient (α) 34 was 0.817.

Qualitative material In line with our research aims, we analyzed the open-ended question “At this time, what are the times, situations, or events that help you feel good?” with a view to gathering direct information about how adolescents tried to taking care of their well-being during the COVID-19 health emergency. A total of 223 responses were collected, totaling 1915 words, with an average response length of 8.6 words. In terms of missing values, 6 participants did not respond or responded "I don't know," resulting in a missing value rate of around 2.5%.

Data analysis strategy

We analyzed the data from our mixed-method questionnaire using quantitative textual analysis (QTA) 35 . QTA is a form of qualitative content analysis and assumes that (1) words that tend to appear together (i.e. close proximity) in a given context may be interpreted as related to a common lexical theme or concept within the discourse under study 36 and (2) traditional statistical techniques may be used to analyze narrative data 37 . Hence, we analyzed the adolescents’ replies to the question “If you were to describe, using a phrase, image, or metaphor, what it is like to be a girl/boy of your age these days, what would you write?” via co-word analysis of correspondence based on our research interests (CA) 38 . The advantage of using CA to analyze this kind of material is that this method allows the researcher to examine the structure of a dataset by rescaling a set of proximity measures into visual distances representing specific locations in a spatial (Cartesian coordinate system) configuration 39 . The analysis yields word-maps which allow the researcher to identify recurring themes, their degree of salience, and how they relate to one another. We assessed similarities via the chi-square and Salton’s cosine indexes 40 along with their statistical significance (set at p < 0.05). Salton’s cosine allows us to organize the relations geometrically so that they can be visualized as structural patterns of relations 41 .

To make the results of the co-word analysis more understandable, word-based concept mapping tools based on multivariate QTA methodologies may be used to identify dominant themes, their relative weight, and how they relate to one another within a given set of textual data 42 . Many studies in the field of health psychology and health promotion 43 , 44 have suggested that common cluster analysis of textual data may be an interesting solution when researchers wish to gain meaningful insight into participants' words by bringing a positivist approach to bear on qualitative data 45 . In the present study, we used the k-means cluster analysis algorithm 46 . The k-means algorithm first groups objects into an arbitrary number of clusters, then computes cluster centroids and assigns each object in such a way that the squared error between it and the empirical mean of a cluster is minimized (i.e., Euclidean distance is used). K-means, like other techniques, seeks to minimize variability within clusters while maximizing variability between clusters 47 . A second critical issue in performing k-means cluster analysis in exploratory QTA is determining the optimal cluster configuration, where optimal refers to the outcome among all possible grouping combinations that presents the full set of the most meaningful associations 48 . Determining what distribution of clusters provides a better understanding of data requires the selection of an objective 'measure of optimal partitioning' (or clustering validity criteria). We chose Calinski- Harabasz index, which is also known as the Variance Ratio Criterion (VRC) 49 from among the available measures because it evaluates the quality of data partitions according to a standard formula. Specifically, the greater the value of the between variance-within variance ratio normalized with respect to the number of clusters, the superior the data partition. To find the best configuration, we ran cluster analysis on the word co-occurrence matrix with varying numbers of clusters (from three to nine), choosing the solution with the best local VRC peak. For all analyses, the alpha level was set at 0.05. In the context of the present study, we expected that the output of the CU would allow us to analyze adolescents’ chosen metaphors by grouping “naturally” occurring emerging themes as a function of lexical similarity and in relation to well-being scores. All analyses were conducted using TLAB 5.0 and SPSS 21.0.

Data cleaning and general descriptive statistics for the lexical corpus

As with other data exploration techniques, QTA required a pre-processing stage to prepare data for analysis. As recommended in the literature, we conducted normalization (removing all general function words such as articles, connection forms, and prepositions); lemmatization (reducing all inflected words to their root form as found in the dictionary) and synonimization (reducing words that may be considered equivalent from the semantic point of view—e.g., illness and sickness—ì to the same root form) with a view to preserving the accuracy of the textual data and preparing the database for running algorithms designed to generate both occurrence and co-occurrence matrices (for details about the process, see 50 , 51 , 52 ).

The resulting qualitative database comprised 1616 occurrences, 652 raw forms, and 439 hapaxes (i.e., words that occurred only once in the text). By adopting a threshold of at least four occurrences (text coverage 83%), root type/token ratio (an index of text richness 53 ) was 16.21, suggesting that the data were suitable for multiple correspondence analysis.

The results are divided into two sections. In the first section, we present quantitative data (i.e., descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations) concerning the levels of general well-being recorded in the adolescent sample using the World Health Organization threshold. In the second section, we summarize the results of the co-word correspondence analysis and subsequent clustering procedure.

The quantitative data outcomes are reported in Table 1 .

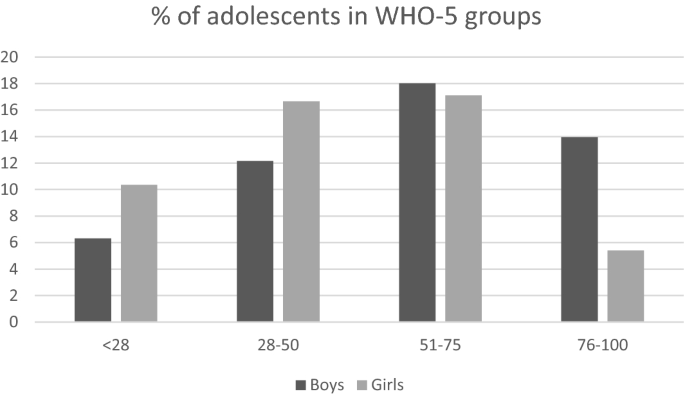

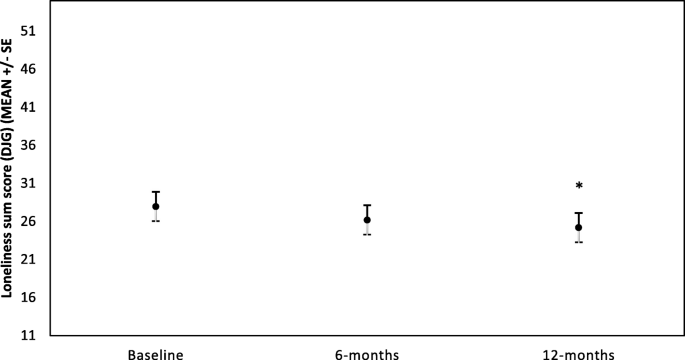

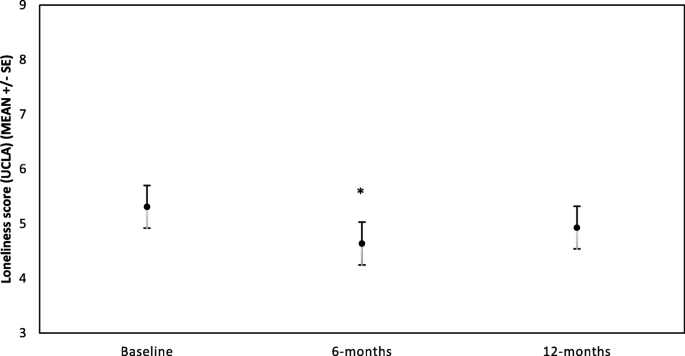

The zero-order correlations suggest that the adolescents’ levels of well-being were negatively associated with age and gender, with younger participants reporting greater well-being and girls (WHO-5 mean score = 47.6) reporting less happiness than boys (WHO-5 mean score = 57.9). In this regard, analysis of variance revealed that the difference in levels of well-being between gender-based groups was statistically significant [t(1,220) = 3.54, p 0.001]. In addition, 36.6% of boys and 54.5% of girls obtained scores of less than 50, indicating that they were at risk of developing depressive symptoms. Furthermore, 12.5% of boys and 20.9% of girls scored less than 28, suggesting that they were at risk of clinical depression. Before moving on to the qualitative analyses, in Fig. 1 we show the percentages of boys and girls classified according to the World Health Organization’s well-being spectra. This figure illustrates the differences in well-being scores between boys and girls, particularly in the group at risk of developing clinical symptoms of depression and the group reporting high well-being.

Adolescents grouped according WHO5 scores. Participants with scores of under 28 were at risk of clinical depression, while those with scores of over 75 displayed high levels of well-being.

The first result of the QTA concerned the words most frequently used by the cohort of adolescents to describe the moments, situations, or events that help them feel good during the COVID-19 syndemic. Given that frequently occurring words reflect recurring themes in a textual corpus and serve as the foundation for more complex coding categories, this is a preliminary form of analysis. The most frequently occurring words in the data set (with the number of occurrences reported in brackets) were: friends (137), family (51), to hang out (38), sport (18), music (18), boyfriend (16), to play (15), time (15), to meet (10), to chat (9), to watch (8), to listen (8), home (7), to help (7), people (6), on-line (5), to sleep (5) and alcohol (4). Even this initial look at the data provides some insight into the contents of adolescents’ strategies for coping with difficulties related to the syndemic; however, this level of interpretation is still quite biased (e.g., word frequency count is not weighted in relation to the length of responses), and it does not reveal the underlying structures in the data or the associations between words. When cluster analysis is used, it provides a more detailed picture. Because the evidence reviewed in the literature does not provide a theoretical framework for the structure of coping strategies, we began our exploratory analysis by determining the most appropriate cluster configuration for our qualitative data. Table 2 displays the values obtained for this purpose via the Calinski-Harabasz index.

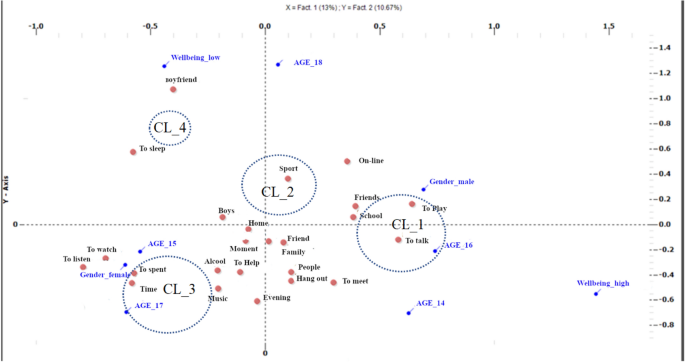

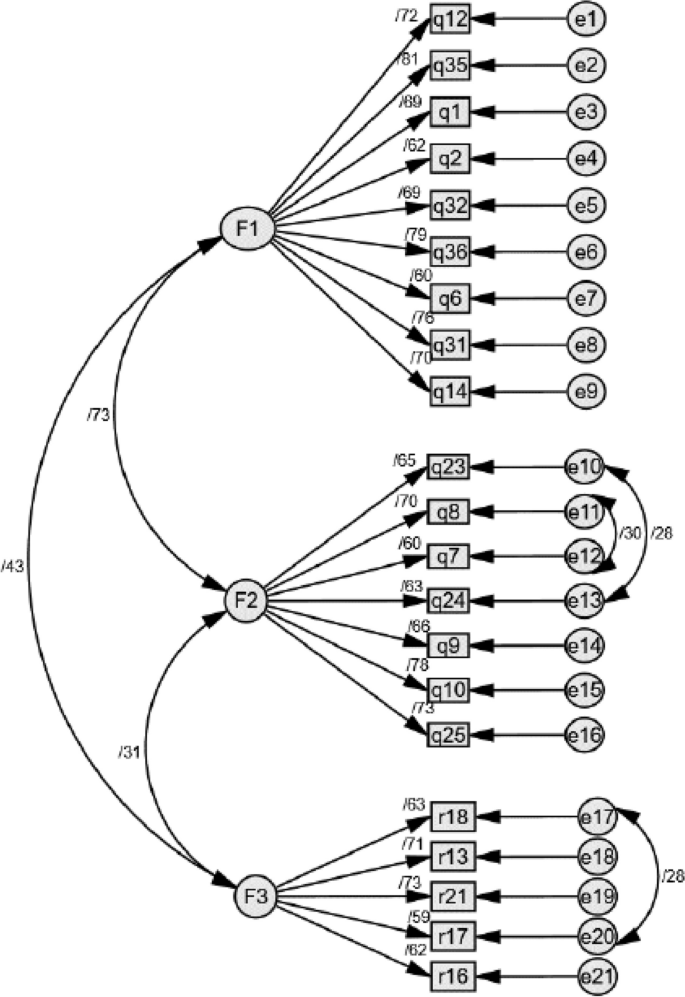

The VRC values revealed that, based on the defined word co-occurrence matrix, the optimal configuration was a solution with four distinct clusters. Peak VRC was found to explain 66.2% of total variance, with low within-variance values: cluster_1 (CL1, ssw = 0.162), cluster_2 (CL2, ssw = 0.131), cluster_3 (CL3, ssw = 0.081) and cluster_4 (CL4, ssw = 0.073). In terms of cluster density, the partition of words across the clusters was relatively even and satisfactory, with CL1 including 35.1% of replies and CL2, CL3 and CL4 including 22.8%, 31.9% and 10.1%, respectively. We then investigated the main contents of the coping strategies adopted by adolescents by calculating the association between the replies grouped in each cluster and the cluster itself (in terms of distance from the centroids). In addition, we evaluated the associations between variables (e.g. age, gender and levels of well-being) and clusters by calculating χ 2 and its statistical significance. Finally, we plotted the cluster coordinates in two-dimensional factorial space to bring to light the meaning of the individual factors. Figure 2 offers a graphical representation of the four-cluster solution.

Graphical representation of clusters and occurrences in a Cartesian Space.

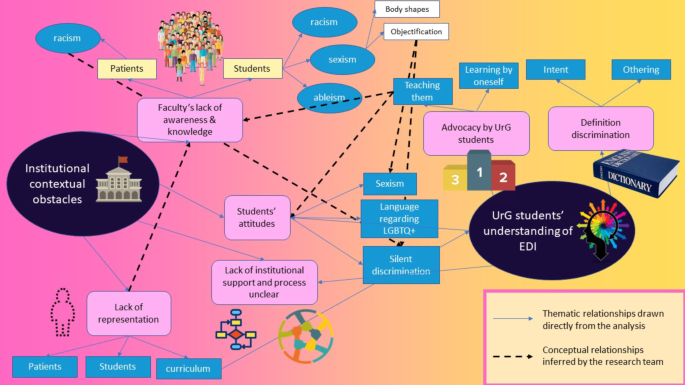

Cluster 1: In general, this cluster was associated with boys (χ 2 = 6.35, p = 0.012) aged 16 years (χ 2 = 5.85, p = 0.016) who reported a high level of well-being (χ 2 = 6.31, p = 0.012). Quotes from this first cluster include: “ hanging out with friends, family, music ” (Boy, 16 y.o, WHO5 = 64), “ the rare evenings when I get together with my group of friends to quietly play some board games ” (Boy, 17 y.o., WHO5 = 72), “ being with my friends, going out, and talking to people close to me .” (Girl, 16 y.o., WHO5 = 64) and “ being with my friends ” (Girl, 16 y.o., WHO5 = 72).

Cluster 2: This cluster grouped 18-year-old adolescents of (χ 2 = 11.85, p = 0.001) with low levels of well-being (χ 2 = 9.42, p = 0.002). Representative quotes included in the cluster were: “ Being with my family or boyfriend, or practicing sports ” (Girl, 18 y.o., WHO5 = 44), “ being with myself ” (Boy, 18 y.o., WHO5 = 38), “ Resting, going out, shopping ” (Male, 16 y.o., WHO5 = 24), “ I listen to music very often, in the evening I sometimes spend time on video calls with "friends" I met online who are from different countries ” (Male, 16.y.o, WHO5 = 36).

Cluster 3: this cluster was associated with 17-year-old adolescents (χ 2 = 4.60, p = 0.032) with a medium–low level of well-being (χ 2 = 4.11, p = 0.042). Quotes include: “ Nighttime, when all is silent and the thoughts screaming in the head fly away ” (Male, 19 y.o., WHO5 = 44), “ sport, alcohol, family ” (Male, 18 y.o., WHO5 = 40), “ Making music, being with my family, and going out for leisurely walks ” (Girl, 17 y.o., WHO5 = 54) and “ I do well in class, in the afternoon I never go out except sometimes with only one friend, so being in class with my classmates makes me feel good because there is no need for me to arrange to be with them ” (Male, 15 y.o., WHO5 = 48).

Cluster 4: The final cluster, which was the least dense accounting for approximately 10% of responses, was exclusively associated with “older” participants aged 19 years (χ 2 = 16.18, p = 0.032). In this case, representative quotes included: “ Seeing my mother happy, feeling right with myself ” (Male, 19 y.o., WHO5 = 44), “ Dancing ” (Girl, 16 y.o., WHO5 = 60), “ Playing online games, watching anime, and talking with friends ” (Male, 17 y.o., WHO5 = 76) and “ taking advantage of my free time ” (Male, 18 y.o., WHO5 = 56).

Before proceeding with the last step in the data analysis, we deemed it of interest to list all the coping strategies deployed by the adolescents with a WHO-5 well-being score of under 28: “ leisure time”, “my family”, “no one”, “Being with friends”, “listening to music and playing with the Xbox”, “seeing my friends outside of school”, “seeing friends and sleeping”, “Seeing my friends and playing football with my team”, “being with friends”, “spending time with my friends”, “there is no time”, “going to school”, “I have no idea”, “sleeping and eating” and “resting, going out, shopping ”. With a view to comparison, we similarly listed all the coping strategies drawn on by the adolescents with a WHO-5 well-being score of over 75: “ My friends, soccer, and my girlfriend's love”, “My family and my girlfriend”, “Family and friends”, “Being with friends”, “Being with family during the holidays”, “My parents' affection and my friends' trust”, “When I am with friends, when I am with my family at home or outside”, ”hanging out with friends”, “being with the people who make me happy, friends and family”, “hanging out with friends and family”, “family, hanging out with friends and playing soccer”, “soccer”, “sports, hanging out with friends and playing” and “Being with people who love me”. It should be noted here that there are substantial differences in the well-being strategies described by these two groups of adolescents (high vs. low well-being). In the descriptions of the high well-being group, for example, both the actions taken to feel better and the different social actors (friends, family members, boyfriends) involved, as well as the positive emotions and feelings felt (love, affection, happiness), were also present. This component (positive emotion and feelings) was lacking in the descriptions of the group with low well-being.

The final step in our data analysis was to label the two axes of Cartesian space with a view to defining a framework of meaning within which to organize the clusters. The principal axis is the straight line that runs closest to the profile point and passes through the zero point, hence meaning is identified first along the y -axis and then along the x -axis (Fig. 2 ). Conventionally, this type of graph in QTA cluster analysis is interpreted in terms of the geometric figures that can be drawn between the representation’s outermost points (see 35 ): in this case, the “triangle” drawn between CL1 (center-right), CL4 (top-left and bottom-center), CL3 (bottom-left). Looking at the first axis (X), we can see that this dimension has two poles: the negative extreme to the left is constituted by CL4 and CL3, whereas the positive extreme to the right is CL1 (the terms positive and negative are only artifacts of the calculus process, and they could easily be inverted within this framework). CL1 was associated with high levels of well-being, while CL4 and CL3, at the opposite pole, grouped adolescents reporting low or medium–low levels of well-being. Consequently, the x dimension may be labeled level of well-being. Similarly, the second axis ( y ) divides CL4 at the positive extreme from CL3 at the negative extreme, with CL2 and CL1 remaining in the middle. CL4 (and CL2, whose projection on the Cartesian axis is very close to that of CL4) included coping strategies that may be conducted alone or with a limited number of people, such as: dancing, playing online games, shopping, and making music. On the other side, CL3 (and CL1, whose projection on the Cartesian axis resembles that of CL2) seemed to group coping strategies that were more social and collective in nature, such as: spending time with family and friends. Hence, the y -axis may be labeled as a second dimension of coping strategies that reflects a notion of I-ness as opposed to a sense of We-ness 54 .

To summarize our findings from this QTA of qualitative data collected from adolescents during the COVID-19 syndemic and integrate them into the existing framework of coping strategies for well-being, the cluster analysis results implies the existence of two 'macro-dimensions' that allow us to organize otherwise apparently “atomized” elements of subjective experience during a time of health emergencies and existential uncertainty. A first factor termed level of well-being and a second termed i-ness/we-ness. In this sense, coping strategies of adolescent during COVID-19 syndemic seem not only to range from individuation (I-ness) to affiliation (we-ness)—or, to draw on the words of Wiekens and Stapel, from a sense of togetherness (We-ness) to a sense of separateness (I-ness); rather, they also seem to be strongly associated with different levels of well-being.

The aim of the present study was to advance our understanding of adolescents’ perceived personal well-being during the COVID-19 public health emergency. Besides assessing participants’ levels of well-being by means of a validated and standardized instrument such as the WHO-5, we were interested in exploring the way adolescents were taking care of their mental health during the syndemic period. Our results were generally in line with the hypotheses that we had formulated, offering insights into how best to support adolescents’ mental health trajectories, informing a complex interpretation of the concept of wellbeing, and calling for further, more in-depth investigation.

The role of age and gender in adolescents’ wellbeing

Looking at the results for gender and age differences in relation to perceived well-being, our data support the findings already reported in the literature: girls perceive significantly lower levels of well-being than their male peers 55 , 56 . In addition, older ages are correlated with lower levels of well-being with a general decline in mental well-being with increasing age, whereby older adolescents experience lower levels of life satisfaction, are less likely to report excellent health, and suffer more frequent mental health problems 57 . Furthermore, the same study showed that, by age 15, girls report poorer mental well-being than boys. The COVID-19 syndemic has confirmed and in some cases accentuated these differences, with older female adolescents suffering more from anxiety and depressive symptoms 58 . This situation is part of a broader picture whereby adolescent mental health has been undergoing a general decline in recent years 59 : for example, a study 60 identified, from 2018 to 2020, a decrease in mean perceived well-being, as measured by the WHO-5, from 43.7 to 35.8 (albeit that both of these scores invite reflection on the state of mental health in adolescence more generally). Thus, it seems that the COVID-19 emergency has accelerated a process that had already been underway for some years, and which requires policy makers to urgently examine the adequacy of current mental health promotion services and practices.

Self-care practices

The results of the QTA offer us a more in-depth and nuanced understanding of the conditions that influence adolescents’ well-being, including the role of gender and age. If we examine cluster 1, we find mainly younger male adolescents, who, when asked the open-ended question about how they take care of their personal well-being, answer by naming strategies chiefly aimed at maintaining peer relationships and teams sports-playing. This cluster is associated with high levels of well-being. On the other hand, in clusters where levels of well-being are lower, adolescents refer to the use of more individualistic and intimate, but also more "passive" strategies (music, shopping…). When looking at the coping strategies reported by those with "extreme" scores on the well-being curve (under 28 and over 75), key differences emerge. Adolescents with scores of < 28 (who are thus potentially at risk of depression) report seeking support from relationships, yet positive affective states rarely feature in their responses, and they make greater use of "static" verbs ("I'm with," "I see…"). Furthermore, in the responses of the group of adolescents with very low levels of well-being, food or alcohol intake (about 5%) also appeared as—dysfunctional—coping strategies, along with higher levels of apathy ("sleep longer"…). In contrast, adolescents with high levels of perceived well-being reported actively seeking out social support and positive relationships, within their families and among their friends, and these efforts were more frequently and explicitly associated with affective and emotional states. This finding corroborates studies in the literature which suggest that adolescents’ growing desire for autonomy and independence from parents and to belonging to a peer group 61 , 62 takes shape in parallel with the maintenance of close and positive relationships with family as a key requirement for psychological well-being and adjustment 63 . In particular, adolescents who have poorer and dysfunctional family interactions and relationships experience greater psychological maladjustment. In the context of the public health emergency, everyday living conditions, especially the fact of sharing the same spaces with family for a prolonged length of time, likely amplified the impact of positive vs dysfunctional family relationships on levels of well-being. We might speculate that the participants in the present study who most frequently mentioned their family as a positive resource are those who were already embedded in more protective and functional systems. Nevertheless, examining the levels of well-being of clusters 1 and 2 (medium–high) versus cluster 3 (medium–low), it seems that it is the combination of family-friends (as in cluster 1 and 2) as sources of support, as opposed to "just" family (as in cluster 3), that makes the difference with respect to levels of perceived well-being.

When the dimensions of well-being and coping strategies are jointly represented along Cartesian axes, a continuum emerges from high levels of well-being associated with more affiliative strategies (we-ness/togetherness) to low levels of well-being associated with more individualistic strategies (I-ness/separatedness). Again, the collective dimension emerges as a resource. However, this result prompts reflection about access to social support as a strategy for coping with situational stress. Thinking "we are all on the same sea" is a view that may help, but it is also true that "everyone has a different boat": those who experience positive and satisfying family and extra-familial relationships may be more likely to identify and seek out the collective dimension as a potential source of protection against stress, while those who had already been experiencing conditions of marginality or dysfunctional family relationships or vulnerability prior to the advent of COVID-19 may find it more difficult and/or unhelpful to turn to more "social" coping strategies. We might reflect on how much this syndemic has widened such gaps, which are not only economic but also social and political, among people in general and among adolescents in particular. Studies have proven that in fragile adolescents (suffering from anxiety and depression), the impact of the public health emergency has further exacerbated their situation and increased the distance between these youths and peers with good levels of mental health who are well integrated at the socio-relational level: indeed, the literature shows that adolescents who experience greater symptoms of anxiety and depression experience a deterioration in social well-being over time, and receive less social support and greater victimization from peers 64 . Other similar studies have shown how the COVID-19 outbreak and the related risk-reduction strategies have changed the social contexts of adolescents in low- and middle-income countries, with profound implications for their well-being, especially in the case of vulnerable adolescents, including those affected by poverty and armed conflict. In such contexts, pre-existing conditions of disadvantage have had a negative impact on the mental health of adolescents, especially that of girls 65 .

Thus, in the current syndemic setting, the issue of "non-communicable disease" emerges strongly, coupled with, and exacerbating the impact of the virus on the physical health of self and significant others. In this scenario, it is not difficult to discern whether the increase in mental health symptoms is the result of the disease itself (directly or indirectly experienced, or as a source of concern for one’s own safety) or the related restrictive measures (e.g., separation from friends, disruption of school, etc.). In any case, it is crucial to carefully weigh the potential benefits of reduced COVID-19 transmission against the detrimental effects on mental health of social isolation, especially in adolescents. From this perspective, insistent calls for social distancing from the authorities seem unfair and counterproductive: while physical distancing may offer protection from a physical health perspective, we need social closeness to maintain good mental health.

Limitations

This study, like others of its kind, features several limitations that should be noted. First, the study is cross-sectional, which means that the teenagers were questioned at a point in time when the COVID-19 epidemic was still ongoing. While this was congruent with the research aims, the research design offers no information about the dynamic evolution of the phenomena under observation, either in terms of well-being or in terms of self-care strategies. A second limitation concerns the fact that the interviews were administered online. Although this approach facilitated data collection at a time when mobility constraints and public health measures made it difficult to gather data directly in the field, it raises concerns regarding the sample's effective representativeness. The most susceptible groups of teenagers or those with educational and economic difficulties may have had restricted access to the Internet and computer technologies, affecting their ability to respond the survey. This means that caution is required in generalizing our findings to all Italian teenagers. Another limitation is that the research plan only considered demographic variables such as age and gender. Instead, studies are needed to detect the effects of other contextual variables that may be associated with adolescent well-being in order to better assess the dynamics of syndemics. In the future, follow-up studies within this line of inquiry should be conducted with larger samples and longitudinal designs, in order to gain a clearer picture of the variables studied, in terms of both the stability of the identified associations and the scope for change, especially given the fact that adolescence in general is a period of transition and rapid transformation.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Health Organization, W. Infection Prevention and Control in the Context of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): A Living Guideline . https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/353565/WHO-2019-nCoV-ipc-guideline-2022.2-eng.pdf?sequence=1 . (2022).

Blundell, R. et al. Inequality and the COVID-19 Crisis in the United Kingdom. Annu. Rev. Econ. 14 , 607–636 (2022).

Article Google Scholar

Horton, R. Offline: COVID-19 is not a pandemic. Lancet 396 , 874 (2020).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Willen, S. S., Knipper, M., Abadía-Barrero, C. E. & Davidovitch, N. Syndemic vulnerability and the right to health. Lancet 389 , 964–977 (2017).

Stein, D. J. et al. Integrating mental health with other non-communicable diseases. BMJ 364 , l295 (2019).

de Figueiredo, C. S. et al. COVID-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents’ mental health: Biological, environmental, and social factors. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 106 , 110171 (2021).

Bhatia, R. Editorial: Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on child and adolescent mental health. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 33 , 568–570 (2020).

Magson, N. R. et al. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Youth Adolesc. 50 , 44–57 (2021).

Zolopa, C. et al. Changes in youth mental health, psychological wellbeing, and substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 7 , 161–177 (2022).

Capasso, A. et al. Increased alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic: The effect of mental health and age in a cross-sectional sample of social media users in the U.S.. Prev. Med. 145 , 106422 (2021).

White, H. R., Stevens, A. K., Hayes, K. & Jackson, K. M. Changes in alcohol consumption among college students due to COVID-19: Effects of campus closure and residential change. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 81 , 725–730 (2020).

Bartel, S. J., Sherry, S. B. & Stewart, S. H. Self-isolation: A significant contributor to cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Subst. Abus. 41 , 409–412 (2020).

Adegboye, D. et al. Understanding why the COVID-19 pandemic-related lockdown increases mental health difficulties in vulnerable young children. JCPP Adv. 1 , e12005 (2021).

Kasinathan, J. et al. Keeping COVID out: A collaborative approach to COVID-19 is associated with a significant reduction in self-harm in young people in custody. Austr. Psychiatry 29 , 412–416 (2021).

Hawes, M. T., Szenczy, A. K., Klein, D. N., Hajcak, G. & Nelson, B. D. Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Med. 2021 , 1–9 (2021).

CAS Google Scholar

Flebus, G. B., Tagini, A., Minonzio, M., Dushku, E. & Crippa, F. The Wisdom acquired during emergencies scale-development and validity. Front. Psychol. 12 , 713404 (2021).

Pepe, A., Biffi, E. & Farina, E. Feeling the emotions, finding the resources: A pathway toward balanced parenting?. Aula Abierta 50 , 807–814 (2021).

Hussong, A. M., Midgette, A. J., Thomas, T. E., Coffman, J. L. & Cho, S. Coping and mental health in early adolescence during COVID-19. Res. Child. Adolesc. Psychopathol. 49 , 1113–1123 (2021).

van de Groep, S., Zanolie, K., Green, K. H., Sweijen, S. W. & Crone, E. A. A daily diary study on adolescents’ mood, empathy, and prosocial behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 15 , e0240349 (2020).

Zeidner, M. & Endler, N. S. Handbook of Coping: Theory, Research, Applications (Wiley, 1995).

Google Scholar

Sica, M. G. & Altoè, M. Coping orientation to problems experienced-nuova Versione Italiana (COPE-NVI): uno strumento per la misura degli stili di coping. Psicoter. Cogn. Comport. 14 , 27 (2008).

Turk, F., Aykut, K. & Kilinç, E. Depression-anxiety and coping strategies of adolescents during the Covid-19 pandemic. Turk. J. Educ. 10 , 58–75 (2021).

Fioretti, C., Palladino, B. E., Nocentini, A. & Menesini, E. Positive and negative experiences of living in COVID-19 pandemic: Analysis of Italian adolescents’ narratives. Front. Psychol. 11 , 599531 (2020).

Pigaiani, Y. et al. Adolescent lifestyle behaviors, coping strategies and subjective wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic: An online student survey. Healthcare (Basel) 8 , 472 (2020).

Emerson, R. W. Convenience sampling, random sampling, and snowball sampling: How does sampling affect the validity of research?. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 109 , 164–168 (2015).

Östlund, U., Kidd, L., Wengström, Y. & Rowa-Dewar, N. Combining qualitative and quantitative research within mixed method research designs: A methodological review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 48 , 369–383 (2011).

Creswell, J. W. & Plano Clark, V. L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (SAGE Publications, 2017).

Couper, M. P. & Hansen, S. E. Computer-Assisted Interviewing. Handbook of Interview Research (Sage, 2002).

World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 284 , 3043–3045 (2000).

Knapp, S. & Vande-Creek, L. A principle-based analysis of the 2002 American Psychological association ethics code. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 41 , 247–254 (2004).

Topp, C. W., Østergaard, S. D., Søndergaard, S. & Bech, P. The WHO-5 well-being index: A sistematic review of the literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 84 , 167–176 (2015).

Hoffman, C. J., Ersser, S. J. & Hopkinson, J. B. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction in mood, breast-and endocrine-related quality of life, and well-being in stage 0 to III breast cancer: Randomized, controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 30 , 1335–1342 (2012).

Jahoda, M. The psychological meaning of various criteria for positive mental health. In Current Concepts of Positive Mental Health vol. 136 22–64 (Basic Books, 2006).

Cronbach, L. J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16 , 297–334 (1951).

Article MATH Google Scholar

Jason, L. & Glenwick, D. Handbook of Methodological Approaches to Community-based Research: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods (Oxford University Press, 2016).

Brier, A. & Hopp, B. Computer assisted text analysis in the social sciences. Qual. Quant. 45 , 103–112 (2011).

Miller, M. & Riechert, B. P. Frame mapping: A quantitative method for investigating issues in the public sphere. Progress Commun. Sci. 2001 , 61–76 (2001).

Greenacre, M. & Blasius, J. Multiple Correspondence Analysis and Related Methods (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2006).

Book MATH Google Scholar

Borg, I., Groenen, P. J. F. & Mair, P. MDS Algorithms. In Applied Multidimensional Scaling (eds. Borg, I. et al .) 81–86 (Springer, 2013).

Hamers, L. & Others, A. Similarity measures in scientometric research: The Jaccard index versus Salton’s cosine formula. Inf. Process. Manag. 25 , 315–318 (1989).

Wagner, C. S. & Leydesdorff, L. Network structure, self-organization, and the growth of international collaboration in science. Res. Policy 34 , 1608–1618 (2005).

Hobro, N., Weinman, J. & Hankins, M. Using the self-regulatory model to cluster chronic pain patients: The first step towards identifying relevant treatments?. Pain 108 , 276–283 (2004).

Matura, L. A., McDonough, A. & Carroll, D. L. Cluster analysis of symptoms in pulmonary arterial hypertension: A pilot study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 11 , 51–61 (2012).

Clatworthy, J., Buick, D., Hankins, M., Weinman, J. & Horne, R. The use and reporting of cluster analysis in health psychology: A review. Br. J. Health Psychol. 10 , 329–358 (2005).

Yadav, J. & Sharma, M. A review of k-mean algorithm. Int. J. Eng. Trends Technol. 4 , 2972–2976 (2013).

Omran, M. G. H., Engelbrecht, A. P. & Salman, A. An overview of clustering methods. Intell. Data Anal. 11 , 583–605 (2007).

Kaur, N. K., Kaur, U. & Singh, U. K-Medoid clustering algorithm-a review. Int. J. Comput. Appl. Technol. 1 , 42–45 (2014).

Maulik, U. & Bandyopadhyay, S. Performance evaluation of some clustering algorithms and validity indices. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 24 , 1650–1654 (2002).

Li, P., Burgess, C. & Lund, K. The acquisition of word meaning through global lexical co-occurrences. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth Annual Child (2000).

Recchia, G. & Louwerse, M. M. Reproducing affective norms with lexical co-occurrence statistics: Predicting valence, arousal, and dominance. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 68 , 1584–1598 (2015).

Veronese, G., Pepe, A. & Afana, A. Conceptualizing the well-being of helpers living and working in war-like conditions: A mixed-method approach. Int. Soc. Work 59 , 938–952 (2016).

Veronese, G., Pepe, A. & Vigliaroni, M. An exploratory multi-site mixed-method study with migrants at Niger transit centers: The push factors underpinning outward and return migration. Int. Soc. Work 64 , 539–555 (2021).

Richards, B. Type/Token Ratios: What do they really tell us?*. J. Child. Lang. 14 , 201–209 (1987).

Pollack, W. S. ‘I’ness and ‘We’ness: Parallel Lines of Development (Boston University Graduate School, 1982).

Farina, E., Ornaghi, V., Pepe, A., Fiorilli, C. & Grazzani, I. High school student burnout: Is empathy a protective or risk factor?. Front. Psychol. 11 , 897 (2020).

Farina, E., Pepe, A., Ornaghi, V. & Cavioni, V. Trait emotional intelligence and school burnout discriminate between high and low alexithymic profiles: A study with female adolescents. Front. Psychol. 12 , 645215 (2021).

Inchley, J. C., Stevens, G. W. J. M., Samdal, O. & Currie, D. B. Enhancing understanding of adolescent health and well-being: The health behaviour in school-aged children study. J. Adolesc. Health 66 , S3–S5 (2020).

Elmer, T., Mepham, K. & Stadtfeld, C. Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLoS ONE 15 , e0236337 (2020).

Strittmatter, E. et al. Pathological Internet use among adolescents: Comparing gamers and non-gamers. Psychiatry Res. 228 , 128–135 (2015).

Pieh, C., Plener, P. L., Probst, T., Dale, R. & Humer, E. Mental health in adolescents during COVID-19-related social distancing and home-schooling. SSRN Electron. J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3795639 (2021).

Casey, B. J. et al. The storm and stress of adolescence: Insights from human imaging and mouse genetics. Dev. Psychobiol. 52 , 225–235 (2010).

Laursen, B. & Hartl, A. C. Understanding loneliness during adolescence: Developmental changes that increase the risk of perceived social isolation. J. Adolesc. 36 , 1261–1268 (2013).

Singer, M., Bulled, N., Ostrach, B. & Mendenhall, E. Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. Lancet 389 , 941–950 (2017).

Chervonsky, E. & Hunt, C. Emotion regulation, mental health, and social wellbeing in a young adolescent sample: A concurrent and longitudinal investigation. Emotion 19 , 270–282 (2019).

Jones, N. et al. Compounding inequalities: Adolescent psychosocial wellbeing and resilience among refugee and host communities in Jordan during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 17 , e0261773 (2022).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

“R.Massa” Department of Human Sciences for Education, University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy

Alessandro Pepe & Eleonora Farina

LAB300, University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

A.P. and E.F. conceived the research, wrote the first draft of the article and contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Alessandro Pepe .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Pepe, A., Farina, E. A mixed-method study on adolescents’ well-being during the COVID-19 syndemic emergency. Sci Rep 13 , 871 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24007-w

Download citation

Received : 07 August 2022

Accepted : 08 November 2022

Published : 17 January 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24007-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

The Use of Mixed Methods in Research

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 13 January 2019

- Cite this reference work entry

- Kate A. McBride 2 ,

- Freya MacMillan 3 ,

- Emma S. George 4 &

- Genevieve Z. Steiner 5

2523 Accesses

9 Citations

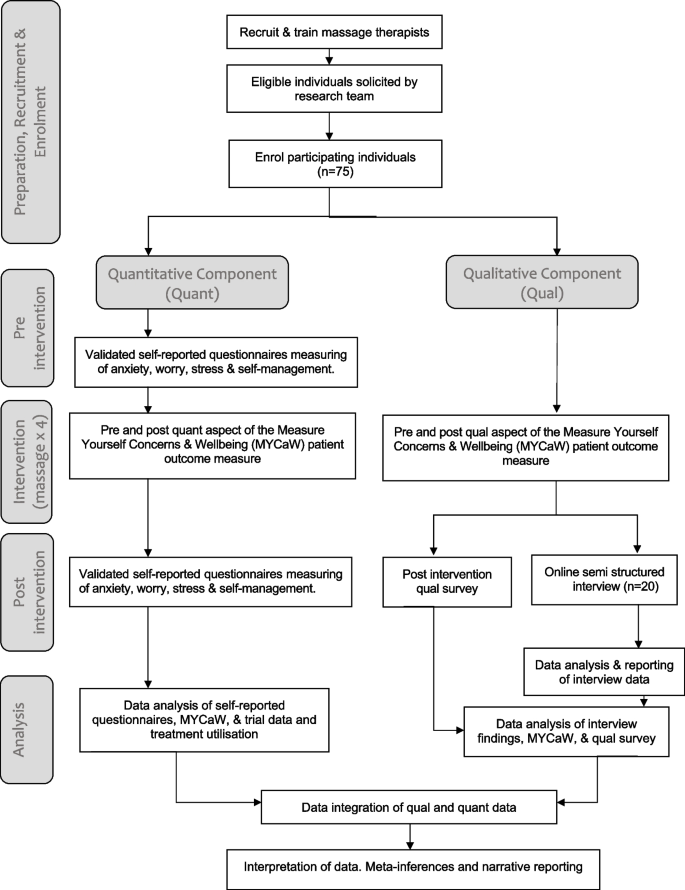

Mixed methods research is becoming increasingly popular and is widely acknowledged as a means of achieving a more complex understanding of research problems. Combining both the in-depth, contextual views of qualitative research with the broader generalizations of larger population quantitative approaches, mixed methods research can be used to produce a rigorous and credible source of data. Using this methodology, the same core issue is investigated through the collection, analysis, and interpretation of both types of data within one study or a series of studies. Multiple designs are possible and can be guided by philosophical assumptions. Both qualitative and quantitative data can be collected simultaneously or sequentially (in any order) through a multiphase project. Integration of the two data sources then occurs with consideration is given to the weighting of both sources; these can either be equal or one can be prioritized over the other. Designed as a guide for novice mixed methods researchers, this chapter gives an overview of the historical and philosophical roots of mixed methods research. We also provide a practical overview of its application in health research as well as pragmatic considerations for those wishing to undertake mixed methods research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Appleton JV, King L. Journeying from the philosophical contemplation of constructivism to the methodological pragmatics of health services research. J Adv Nurs. 2002;40(6):641–8.

Article Google Scholar

Baba CT, Oliveira IM, Silva AEF, Vieira LM, Cerri NC, Florindo AA, de Oliveira Gomes GA. Evaluating the impact of a walking program in a disadvantaged area: using the RE-AIM framework by mixed methods. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):709. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4698-5 .

Bryman A. The research question in social research: what is its role? Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2007;10(1):5–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570600655282 .

Bryman A. The end of the paradigm wars. In: Alasuutari P, Bickman L, Brannen J, editors. The Sage handbook of social research methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2008. p. 13–25.

Google Scholar

Caracelli VJ, Greene JC. Data-analysis strategies for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 1993;15(2):195–207. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737015002195 .

Castro FG, Kellison JG, Boyd SJ, Kopak A. A methodology for conducting integrative mixed methods research and data analyses. J Mixed Methods Res. 2010;4(4):342–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689810382916 .

Center for Innovation in Teaching in Research. Choosing a mixed methods design. 2017. Retrieved 15 Nov 2017 from https://cirt.gcu.edu/research/developmentresources/research_ready/mixed_methods/choosing_design .

Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2018.

Curry LA, Krumholz HM, O’Cathain A, Clark VLP, Cherlin E, Bradley EH. Mixed methods in biomedical and health services research. Circ-Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(1):119–23. https://doi.org/10.1161/circoutcomes.112.967885 .

Denscombe M. Communities of practice: a research paradigm for the mixed methods approach. J Mixed Methods Res. 2008;2(3):270–83.

Doyle L, Brady A-M, Byrne G. An overview of mixed methods research. J Res Nurs. 2009;14(2):175–85.

Foster NE, Bishop A, Bartlam B, Ogollah R, Barlas P, Holden M, … Young J. Evaluating acupuncture and standard carE for pregnant women with back pain (EASE back): a feasibility study and pilot randomised trial. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(33):1–236. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta20330 .

Haider AH, Schneider EB, Kodadek LM, Adler RR, Ranjit A, Torain M, … Lau BD. Emergency department query for patient-centered approaches to sexual orientation and gender identity the EQUALITY study. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):819–828. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0906 .

Harding KE, Taylor NF, Bowers B, Stafford M, Leggat SG. Clinician and patient perspectives of a new model of triage in a community rehabilitation program that reduced waiting time: a qualitative analysis. Aust Health Rev. 2013;37(3):324–30. https://doi.org/10.1071/ah13033 .

Hoddinott P, Britten J, Prescott GJ, Tappin D, Ludbrook A, Godden DJ. Effectiveness of policy to provide breastfeeding groups ( BIG) for pregnant and breastfeeding mothers in primary care: cluster randomised controlled trial. Br Med J. 2009;338:a3026, 10. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a3026 .

Ivankova NV, Creswell JW, Stick SL. Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: from theory to practice. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822x05282260 .

Johnson B, Gray R. A history of philosophical and theoretical issues for mixed methods research. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. Sage handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2010. p. 69–94.

Chapter Google Scholar

Johnson BR, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Mixed methods research: a research paradigm whose time has come. Educ Res. 2004;33(7):14–26. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x033007014 .

Keeney S, McKenna H, Fleming P, McIlfatrick S. Attitudes to cancer and cancer prevention: what do people aged 35–54 years think? Eur J Cancer Care. 2010;19(6):769–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01137.x .

McBride KA, Ballinger ML, Schlub TE, Young MA, Tattersall MHN, Kirk J, et al. Psychosocial morbidity in TP53 mutation carriers: is whole-body cancer screening beneficial? Familial Cancer. 2017;16(3):423–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-016-9964-7 .

Mertens DM. Transformative mixed methods: addressing inequities. Am Behav Sci. 2012;56(6):802–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764211433797 .

Moffatt S, White M, Mackintosh J, Howel D. Using quantitative and qualitative data in health services research – what happens when mixed method findings conflict? BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:28. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-6-28 .

Morse JM. Approaches to qualitative-quantitative methodological triangulation. Nurs Res. 1991a;40(2):120–3.

Morse JM. Principles of mixed methods and multimethod research design. In: Tashakkori A, Teddilie C, editors. SAGE handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1991b.

Mutrie N, Doolin O, Fitzsimons CF, Grant PM, Granat M, Grealy M, et al. Increasing older adults’ walking through primary care: results of a pilot randomized controlled trial. Fam Pract. 2012;29(6):633–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cms038 .

Newman I, Ridenour C, Newman C, De Marco G. A typology of research purposes and its relationship to mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2003. p. 167–88.

O’Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. The quality of mixed methods studies in health services research. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008;13(2):92–8. https://doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2007.007074 .

Onwuegbuzie AJ, Collins KMT. A typology of mixed methods sampling designs in social science research. Qual Rep. 2007;12(2):281–316.

Plano Clark VL, Badiee M. Research questions in mixed methods research. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. SAGE handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2010. p. 275–304.

Prades, J., Algara, M., Espinas, J. A., Farrus, B., Arenas, M., Reyes, V., . . . Borras, J. M. (2017). Understanding variations in the use of hypofractionated radiotherapy and its specific indications for breast cancer: a mixed-methods study. Radiother Oncol, 123(1), 22–28. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2017.01.014 .

Tariq S, Woodman J. Using mixed methods in health research. JRSM Short Rep. 2013; 4 (6):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042533313479197 .

Tashakkori A, Creswell JW. Editorial: the new era of mixed methods. J Mixed Methods Res. 2007;1(1):3–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/2345678906293042 .

Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. The past and future of mixed methods research: from data triangulation to mixed model designs. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2003. p. 671–701.

Teddlie C, Tashakkori A. Foundations of mixed methods research: integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2009.

Teddlie C, Yu F. Mixed methods sampling a typology with examples. J Mixed Methods Res. 2007;1(1):77–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/2345678906292430 .

Wellard SJ, Rasmussen B, Savage S, Dunning T. Exploring staff diabetes medication knowledge and practices in regional residential care: triangulation study. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(13–14):1933–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12043 .

Zhang W. Mixed methods application in health intervention research: a multiple case study. Int J Mult Res Approaches. 2014;8(1):24–35. https://doi.org/10.5172/mra.2014.8.1.24 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Medicine and Translational Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Kate A. McBride

School of Science and Health and Translational Health Research Institute (THRI), Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia

Freya MacMillan

School of Science and Health, Western Sydney University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Emma S. George

NICM and Translational Health Research Institute (THRI), Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia

Genevieve Z. Steiner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kate A. McBride .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Science and Health, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia

Pranee Liamputtong

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

McBride, K.A., MacMillan, F., George, E.S., Steiner, G.Z. (2019). The Use of Mixed Methods in Research. In: Liamputtong, P. (eds) Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_97

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_97

Published : 13 January 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-10-5250-7

Online ISBN : 978-981-10-5251-4

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- News & Highlights

- Publications and Documents

- Postgraduate Education

- Browse Our Courses

- C/T Research Academy

- K12 Investigator Training

- Translational Innovator

- SMART IRB Reliance Request

- Biostatistics Consulting

- Regulatory Support

- Pilot Funding

- Informatics Program

- Community Engagement

- Diversity Inclusion

- Research Enrollment and Diversity

- Harvard Catalyst Profiles

Community Engagement Program

Supporting bi-directional community engagement to improve the relevance, quality, and impact of research.

- Getting Started

- Resources for Equity in Research

- Community-Engaged Student Practice Placement

- Maternal Health Equity

- Youth Mental Health

- Leadership and Membership

- Past Members

- Study Review Rubric

- Community Ambassador Initiative

- Implementation Science Working Group

- Past Webinars & Podcasts

- Policy Atlas

- Community Advisory Board

For more information:

Mixed methods research.

According to the National Institutes of Health , mixed methods strategically integrates or combines rigorous quantitative and qualitative research methods to draw on the strengths of each. Mixed method approaches allow researchers to use a diversity of methods, combining inductive and deductive thinking, and offsetting limitations of exclusively quantitative and qualitative research through a complementary approach that maximizes strengths of each data type and facilitates a more comprehensive understanding of health issues and potential resolutions.¹ Mixed methods may be employed to produce a robust description and interpretation of the data, make quantitative results more understandable, or understand broader applicability of small-sample qualitative findings.

Integration

This refers to the ways in which qualitative and quantitative research activities are brought together to achieve greater insight. Mixed methods is not simply having quantitative and qualitative data available or analyzing and presenting data findings separately. The integration process can occur during data collection, analysis, or in the presentation of results.

¹ NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research: Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences

Basic Mixed Methods Research Designs

View image description .

Five Key Questions for Getting Started

- What do you want to know?

- What will be the detailed quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research questions that you hope to address?

- What quantitative and qualitative data will you collect and analyze?

- Which rigorous methods will you use to collect data and/or engage stakeholders?

- How will you integrate the data in a way that allows you to address the first question?

Rationale for Using Mixed Methods

- Obtain different, multiple perspectives: validation

- Build comprehensive understanding

- Explain statistical results in more depth

- Have better contextualized measures

- Track the process of program or intervention

- Study patient-centered outcomes and stakeholder engagement

Sample Mixed Methods Research Study

The EQUALITY study used an exploratory sequential design to identify the optimal patient-centered approach to collect sexual orientation data in the emergency department.

Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis : Semi-structured interviews with patients of different sexual orientation, age, race/ethnicity, as well as healthcare professionals of different roles, age, and race/ethnicity.

Builds Into : Themes identified in the interviews were used to develop questions for the national survey.

Quantitative Data Collection and Analysis : Representative national survey of patients and healthcare professionals on the topic of reporting gender identity and sexual orientation in healthcare.

Other Resources:

Introduction to Mixed Methods Research : Harvard Catalyst’s eight-week online course offers an opportunity for investigators who want to understand and apply a mixed methods approach to their research.

Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences [PDF] : This guide provides a detailed overview of mixed methods designs, best practices, and application to various types of grants and projects.

Mixed Methods Research Training Program for the Health Sciences (MMRTP ): Selected scholars for this summer training program, hosted by Johns Hopkins’ Bloomberg School of Public Health, have access to webinars, resources, a retreat to discuss their research project with expert faculty, and are matched with mixed methods consultants for ongoing support.

Michigan Mixed Methods : University of Michigan Mixed Methods program offers a variety of resources, including short web videos and recommended reading.

To use a mixed methods approach, you may want to first brush up on your qualitative skills. Below are a few helpful resources specific to qualitative research:

- Qualitative Research Guidelines Project : A comprehensive guide for designing, writing, reviewing and reporting qualitative research.

- Fundamentals of Qualitative Research Methods – What is Qualitative Research : A six-module web video series covering essential topics in qualitative research, including what is qualitative research and how to use the most common methods, in-depth interviews, and focus groups.

View PDF of the above information.

- What is mixed methods research?

Last updated

20 February 2023

Reviewed by

Miroslav Damyanov

By blending both quantitative and qualitative data, mixed methods research allows for a more thorough exploration of a research question. It can answer complex research queries that cannot be solved with either qualitative or quantitative research .

Analyze your mixed methods research

Dovetail streamlines analysis to help you uncover and share actionable insights

Mixed methods research combines the elements of two types of research: quantitative and qualitative.

Quantitative data is collected through the use of surveys and experiments, for example, containing numerical measures such as ages, scores, and percentages.

Qualitative data involves non-numerical measures like beliefs, motivations, attitudes, and experiences, often derived through interviews and focus group research to gain a deeper understanding of a research question or phenomenon.

Mixed methods research is often used in the behavioral, health, and social sciences, as it allows for the collection of numerical and non-numerical data.

- When to use mixed methods research

Mixed methods research is a great choice when quantitative or qualitative data alone will not sufficiently answer a research question. By collecting and analyzing both quantitative and qualitative data in the same study, you can draw more meaningful conclusions.

There are several reasons why mixed methods research can be beneficial, including generalizability, contextualization, and credibility.

For example, let's say you are conducting a survey about consumer preferences for a certain product. You could collect only quantitative data, such as how many people prefer each product and their demographics. Or you could supplement your quantitative data with qualitative data, such as interviews and focus groups , to get a better sense of why people prefer one product over another.

It is important to note that mixed methods research does not only mean collecting both types of data. Rather, it also requires carefully considering the relationship between the two and method flexibility.

You may find differing or even conflicting results by combining quantitative and qualitative data . It is up to the researcher to then carefully analyze the results and consider them in the context of the research question to draw meaningful conclusions.

When designing a mixed methods study, it is important to consider your research approach, research questions, and available data. Think about how you can use different techniques to integrate the data to provide an answer to your research question.

- Mixed methods research design

A mixed methods research design is an approach to collecting and analyzing both qualitative and quantitative data in a single study.

Mixed methods designs allow for method flexibility and can provide differing and even conflicting results. Examples of mixed methods research designs include convergent parallel, explanatory sequential, and exploratory sequential.