Research Paper Analysis: How to Analyze a Research Article + Example

Why might you need to analyze research? First of all, when you analyze a research article, you begin to understand your assigned reading better. It is also the first step toward learning how to write your own research articles and literature reviews. However, if you have never written a research paper before, it may be difficult for you to analyze one. After all, you may not know what criteria to use to evaluate it. But don’t panic! We will help you figure it out!

In this article, our team has explained how to analyze research papers quickly and effectively. At the end, you will also find a research analysis paper example to see how everything works in practice.

- 🔤 Research Analysis Definition

📊 How to Analyze a Research Article

✍️ how to write a research analysis.

- 📝 Analysis Example

- 🔎 More Examples

🔗 References

🔤 research paper analysis: what is it.

A research paper analysis is an academic writing assignment in which you analyze a scholarly article’s methodology, data, and findings. In essence, “to analyze” means to break something down into components and assess each of them individually and in relation to each other. The goal of an analysis is to gain a deeper understanding of a subject. So, when you analyze a research article, you dissect it into elements like data sources , research methods, and results and evaluate how they contribute to the study’s strengths and weaknesses.

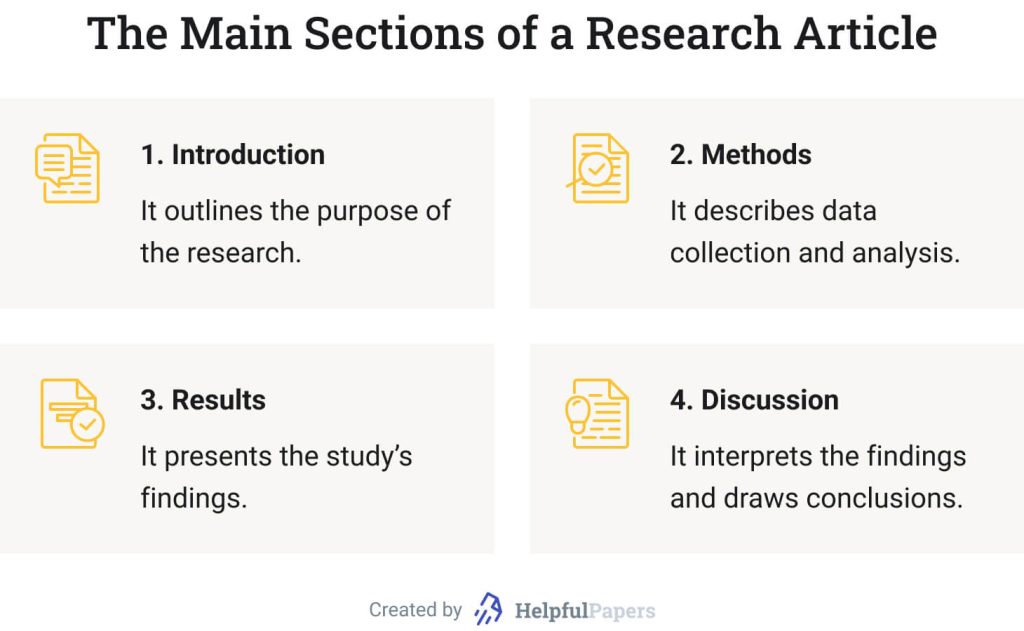

📋 Research Analysis Format

A research analysis paper has a pretty straightforward structure. Check it out below!

Research articles usually include the following sections: introduction, methods, results, and discussion. In the following paragraphs, we will discuss how to analyze a scientific article with a focus on each of its parts.

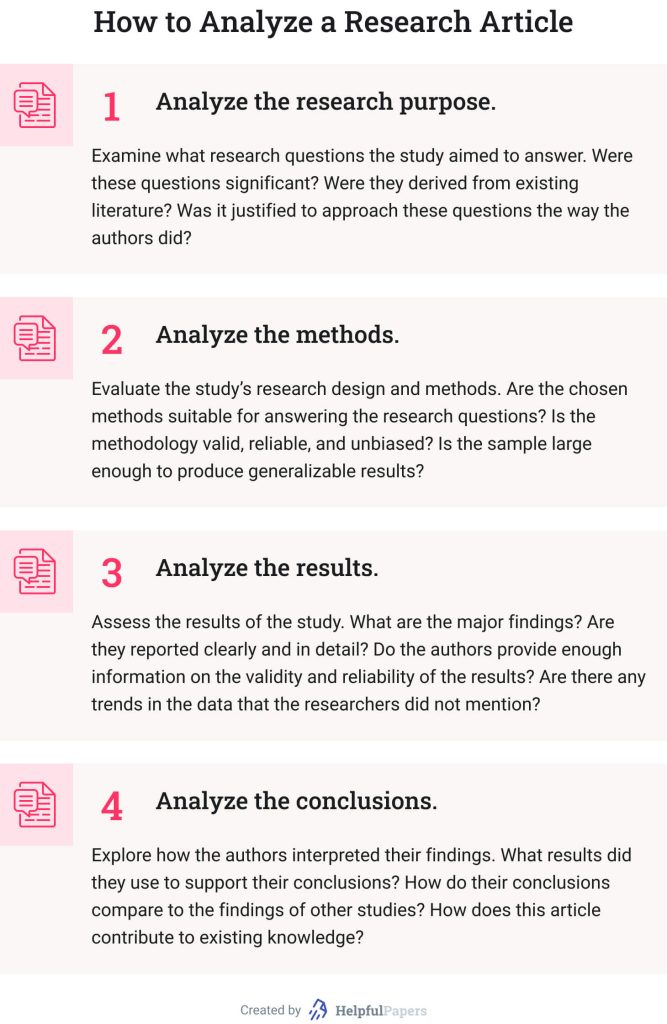

How to Analyze a Research Paper: Purpose

The purpose of the study is usually outlined in the introductory section of the article. Analyzing the research paper’s objectives is critical to establish the context for the rest of your analysis.

When analyzing the research aim, you should evaluate whether it was justified for the researchers to conduct the study. In other words, you should assess whether their research question was significant and whether it arose from existing literature on the topic.

Here are some questions that may help you analyze a research paper’s purpose:

- Why was the research carried out?

- What gaps does it try to fill, or what controversies to settle?

- How does the study contribute to its field?

- Do you agree with the author’s justification for approaching this particular question in this way?

How to Analyze a Paper: Methods

When analyzing the methodology section , you should indicate the study’s research design (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed) and methods used (for example, experiment, case study, correlational research, survey, etc.). After that, you should assess whether these methods suit the research purpose. In other words, do the chosen methods allow scholars to answer their research questions within the scope of their study?

For example, if scholars wanted to study US students’ average satisfaction with their higher education experience, they could conduct a quantitative survey . However, if they wanted to gain an in-depth understanding of the factors influencing US students’ satisfaction with higher education, qualitative interviews would be more appropriate.

When analyzing methods, you should also look at the research sample . Did the scholars use randomization to select study participants? Was the sample big enough for the results to be generalizable to a larger population?

You can also answer the following questions in your methodology analysis:

- Is the methodology valid? In other words, did the researchers use methods that accurately measure the variables of interest?

- Is the research methodology reliable? A research method is reliable if it can produce stable and consistent results under the same circumstances.

- Is the study biased in any way?

- What are the limitations of the chosen methodology?

How to Analyze Research Articles’ Results

You should start the analysis of the article results by carefully reading the tables, figures, and text. Check whether the findings correspond to the initial research purpose. See whether the results answered the author’s research questions or supported the hypotheses stated in the introduction.

To analyze the results section effectively, answer the following questions:

- What are the major findings of the study?

- Did the author present the results clearly and unambiguously?

- Are the findings statistically significant ?

- Does the author provide sufficient information on the validity and reliability of the results?

- Have you noticed any trends or patterns in the data that the author did not mention?

How to Analyze Research: Discussion

Finally, you should analyze the authors’ interpretation of results and its connection with research objectives. Examine what conclusions the authors drew from their study and whether these conclusions answer the original question.

You should also pay attention to how the authors used findings to support their conclusions. For example, you can reflect on why their findings support that particular inference and not another one. Moreover, more than one conclusion can sometimes be made based on the same set of results. If that’s the case with your article, you should analyze whether the authors addressed other interpretations of their findings .

Here are some useful questions you can use to analyze the discussion section:

- What findings did the authors use to support their conclusions?

- How do the researchers’ conclusions compare to other studies’ findings?

- How does this study contribute to its field?

- What future research directions do the authors suggest?

- What additional insights can you share regarding this article? For example, do you agree with the results? What other questions could the researchers have answered?

Now, you know how to analyze an article that presents research findings. However, it’s just a part of the work you have to do to complete your paper. So, it’s time to learn how to write research analysis! Check out the steps below!

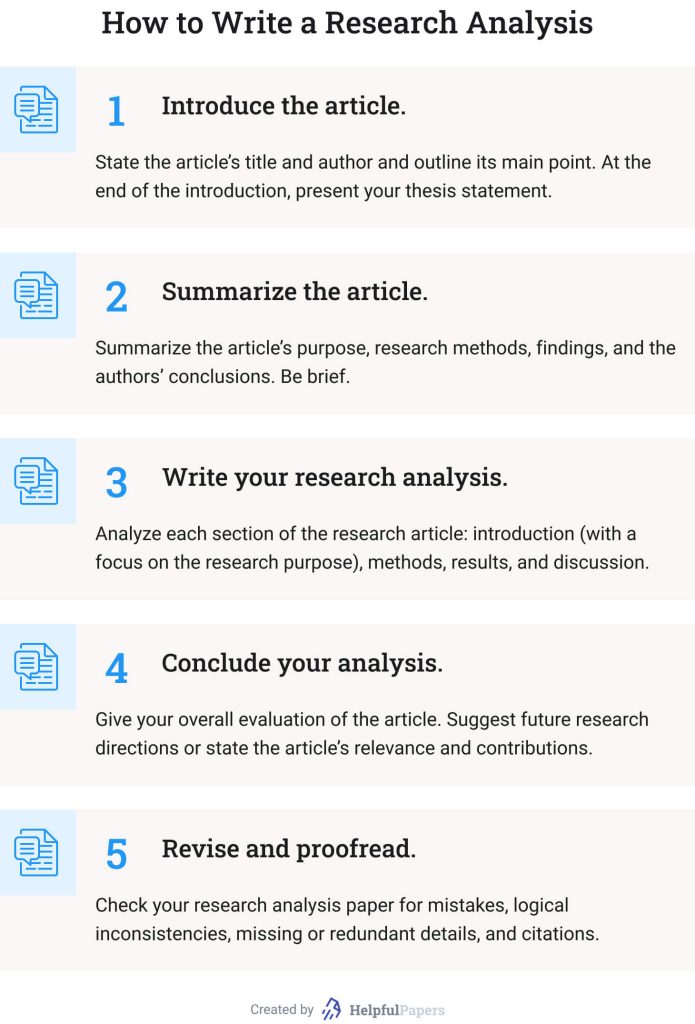

1. Introduce the Article

As with most academic assignments, you should start your research article analysis with an introduction. Here’s what it should include:

- The article’s publication details . Specify the title of the scholarly work you are analyzing, its authors, and publication date. Remember to enclose the article’s title in quotation marks and write it in title case .

- The article’s main point . State what the paper is about. What did the authors study, and what was their major finding?

- Your thesis statement . End your introduction with a strong claim summarizing your evaluation of the article. Consider briefly outlining the research paper’s strengths, weaknesses, and significance in your thesis.

Keep your introduction brief. Save the word count for the “meat” of your paper — that is, for the analysis.

2. Summarize the Article

Now, you should write a brief and focused summary of the scientific article. It should be shorter than your analysis section and contain all the relevant details about the research paper.

Here’s what you should include in your summary:

- The research purpose . Briefly explain why the research was done. Identify the authors’ purpose and research questions or hypotheses .

- Methods and results . Summarize what happened in the study. State only facts, without the authors’ interpretations of them. Avoid using too many numbers and details; instead, include only the information that will help readers understand what happened.

- The authors’ conclusions . Outline what conclusions the researchers made from their study. In other words, describe how the authors explained the meaning of their findings.

If you need help summarizing an article, you can use our free summary generator .

3. Write Your Research Analysis

The analysis of the study is the most crucial part of this assignment type. Its key goal is to evaluate the article critically and demonstrate your understanding of it.

We’ve already covered how to analyze a research article in the section above. Here’s a quick recap:

- Analyze whether the study’s purpose is significant and relevant.

- Examine whether the chosen methodology allows for answering the research questions.

- Evaluate how the authors presented the results.

- Assess whether the authors’ conclusions are grounded in findings and answer the original research questions.

Although you should analyze the article critically, it doesn’t mean you only should criticize it. If the authors did a good job designing and conducting their study, be sure to explain why you think their work is well done. Also, it is a great idea to provide examples from the article to support your analysis.

4. Conclude Your Analysis of Research Paper

A conclusion is your chance to reflect on the study’s relevance and importance. Explain how the analyzed paper can contribute to the existing knowledge or lead to future research. Also, you need to summarize your thoughts on the article as a whole. Avoid making value judgments — saying that the paper is “good” or “bad.” Instead, use more descriptive words and phrases such as “This paper effectively showed…”

Need help writing a compelling conclusion? Try our free essay conclusion generator !

5. Revise and Proofread

Last but not least, you should carefully proofread your paper to find any punctuation, grammar, and spelling mistakes. Start by reading your work out loud to ensure that your sentences fit together and sound cohesive. Also, it can be helpful to ask your professor or peer to read your work and highlight possible weaknesses or typos.

📝 Research Paper Analysis Example

We have prepared an analysis of a research paper example to show how everything works in practice.

No Homework Policy: Research Article Analysis Example

This paper aims to analyze the research article entitled “No Assignment: A Boon or a Bane?” by Cordova, Pagtulon-an, and Tan (2019). This study examined the effects of having and not having assignments on weekends on high school students’ performance and transmuted mean scores. This article effectively shows the value of homework for students, but larger studies are needed to support its findings.

Cordova et al. (2019) conducted a descriptive quantitative study using a sample of 115 Grade 11 students of the Central Mindanao University Laboratory High School in the Philippines. The sample was divided into two groups: the first received homework on weekends, while the second didn’t. The researchers compared students’ performance records made by teachers and found that students who received assignments performed better than their counterparts without homework.

The purpose of this study is highly relevant and justified as this research was conducted in response to the debates about the “No Homework Policy” in the Philippines. Although the descriptive research design used by the authors allows to answer the research question, the study could benefit from an experimental design. This way, the authors would have firm control over variables. Additionally, the study’s sample size was not large enough for the findings to be generalized to a larger population.

The study results are presented clearly, logically, and comprehensively and correspond to the research objectives. The researchers found that students’ mean grades decreased in the group without homework and increased in the group with homework. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that homework positively affected students’ performance. This conclusion is logical and grounded in data.

This research effectively showed the importance of homework for students’ performance. Yet, since the sample size was relatively small, larger studies are needed to ensure the authors’ conclusions can be generalized to a larger population.

🔎 More Research Analysis Paper Examples

Do you want another research analysis example? Check out the best analysis research paper samples below:

- Gracious Leadership Principles for Nurses: Article Analysis

- Effective Mental Health Interventions: Analysis of an Article

- Nursing Turnover: Article Analysis

- Nursing Practice Issue: Qualitative Research Article Analysis

- Quantitative Article Critique in Nursing

- LIVE Program: Quantitative Article Critique

- Evidence-Based Practice Beliefs and Implementation: Article Critique

- “Differential Effectiveness of Placebo Treatments”: Research Paper Analysis

- “Family-Based Childhood Obesity Prevention Interventions”: Analysis Research Paper Example

- “Childhood Obesity Risk in Overweight Mothers”: Article Analysis

- “Fostering Early Breast Cancer Detection” Article Analysis

- Lesson Planning for Diversity: Analysis of an Article

- Journal Article Review: Correlates of Physical Violence at School

- Space and the Atom: Article Analysis

- “Democracy and Collective Identity in the EU and the USA”: Article Analysis

- China’s Hegemonic Prospects: Article Review

- Article Analysis: Fear of Missing Out

- Article Analysis: “Perceptions of ADHD Among Diagnosed Children and Their Parents”

- Codependence, Narcissism, and Childhood Trauma: Analysis of the Article

- Relationship Between Work Intensity, Workaholism, Burnout, and MSC: Article Review

We hope that our article on research paper analysis has been helpful. If you liked it, please share this article with your friends!

- Analyzing Research Articles: A Guide for Readers and Writers | Sam Mathews

- Summary and Analysis of Scientific Research Articles | San José State University Writing Center

- Analyzing Scholarly Articles | Texas A&M University

- Article Analysis Assignment | University of Wisconsin-Madison

- How to Summarize a Research Article | University of Connecticut

- Critique/Review of Research Articles | University of Calgary

- Art of Reading a Journal Article: Methodically and Effectively | PubMed Central

- Write a Critical Review of a Scientific Journal Article | McLaughlin Library

- How to Read and Understand a Scientific Paper: A Guide for Non-scientists | LSE

- How to Analyze Journal Articles | Classroom

How to Write an Animal Testing Essay: Tips for Argumentative & Persuasive Papers

Descriptive essay topics: examples, outline, & more.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to ChatBot Assistant

- Academic Writing

- What is a Research Paper?

- Steps in Writing a Research Paper

- Critical Reading and Writing

- Punctuation

- Writing Exercises

- ELL/ESL Resources

Analysis in Research Papers

To analyze means to break a topic or concept down into its parts in order to inspect and understand it, and to restructure those parts in a way that makes sense to you. In an analytical research paper, you do research to become an expert on a topic so that you can restructure and present the parts of the topic from your own perspective.

For example, you could analyze the role of the mother in the ancient Egyptian family. You could break down that topic into its parts--the mother's duties in the family, social status, and expected role in the larger society--and research those parts in order to present your general perspective and conclusion about the mother's role.

Need Assistance?

If you would like assistance with any type of writing assignment, learning coaches are available to assist you. Please contact Academic Support by emailing [email protected].

Questions or feedback about SUNY Empire's Writing Support?

Contact us at [email protected] .

Smart Cookies

They're not just in our classes – they help power our website. Cookies and similar tools allow us to better understand the experience of our visitors. By continuing to use this website, you consent to SUNY Empire State University's usage of cookies and similar technologies in accordance with the university's Privacy Notice and Cookies Policy .

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Analysis is a type of primary research that involves finding and interpreting patterns in data, classifying those patterns, and generalizing the results. It is useful when looking at actions, events, or occurrences in different texts, media, or publications. Analysis can usually be done without considering most of the ethical issues discussed in the overview, as you are not working with people but rather publicly accessible documents. Analysis can be done on new documents or performed on raw data that you yourself have collected.

Here are several examples of analysis:

- Recording commercials on three major television networks and analyzing race and gender within the commercials to discover some conclusion.

- Analyzing the historical trends in public laws by looking at the records at a local courthouse.

- Analyzing topics of discussion in chat rooms for patterns based on gender and age.

Analysis research involves several steps:

- Finding and collecting documents.

- Specifying criteria or patterns that you are looking for.

- Analyzing documents for patterns, noting number of occurrences or other factors.

How to conduct a meta-analysis in eight steps: a practical guide

- Open access

- Published: 30 November 2021

- Volume 72 , pages 1–19, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Christopher Hansen 1 ,

- Holger Steinmetz 2 &

- Jörn Block 3 , 4 , 5

143k Accesses

44 Citations

157 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

“Scientists have known for centuries that a single study will not resolve a major issue. Indeed, a small sample study will not even resolve a minor issue. Thus, the foundation of science is the cumulation of knowledge from the results of many studies.” (Hunter et al. 1982 , p. 10)

Meta-analysis is a central method for knowledge accumulation in many scientific fields (Aguinis et al. 2011c ; Kepes et al. 2013 ). Similar to a narrative review, it serves as a synopsis of a research question or field. However, going beyond a narrative summary of key findings, a meta-analysis adds value in providing a quantitative assessment of the relationship between two target variables or the effectiveness of an intervention (Gurevitch et al. 2018 ). Also, it can be used to test competing theoretical assumptions against each other or to identify important moderators where the results of different primary studies differ from each other (Aguinis et al. 2011b ; Bergh et al. 2016 ). Rooted in the synthesis of the effectiveness of medical and psychological interventions in the 1970s (Glass 2015 ; Gurevitch et al. 2018 ), meta-analysis is nowadays also an established method in management research and related fields.

The increasing importance of meta-analysis in management research has resulted in the publication of guidelines in recent years that discuss the merits and best practices in various fields, such as general management (Bergh et al. 2016 ; Combs et al. 2019 ; Gonzalez-Mulé and Aguinis 2018 ), international business (Steel et al. 2021 ), economics and finance (Geyer-Klingeberg et al. 2020 ; Havranek et al. 2020 ), marketing (Eisend 2017 ; Grewal et al. 2018 ), and organizational studies (DeSimone et al. 2020 ; Rudolph et al. 2020 ). These articles discuss existing and trending methods and propose solutions for often experienced problems. This editorial briefly summarizes the insights of these papers; provides a workflow of the essential steps in conducting a meta-analysis; suggests state-of-the art methodological procedures; and points to other articles for in-depth investigation. Thus, this article has two goals: (1) based on the findings of previous editorials and methodological articles, it defines methodological recommendations for meta-analyses submitted to Management Review Quarterly (MRQ); and (2) it serves as a practical guide for researchers who have little experience with meta-analysis as a method but plan to conduct one in the future.

2 Eight steps in conducting a meta-analysis

2.1 step 1: defining the research question.

The first step in conducting a meta-analysis, as with any other empirical study, is the definition of the research question. Most importantly, the research question determines the realm of constructs to be considered or the type of interventions whose effects shall be analyzed. When defining the research question, two hurdles might develop. First, when defining an adequate study scope, researchers must consider that the number of publications has grown exponentially in many fields of research in recent decades (Fortunato et al. 2018 ). On the one hand, a larger number of studies increases the potentially relevant literature basis and enables researchers to conduct meta-analyses. Conversely, scanning a large amount of studies that could be potentially relevant for the meta-analysis results in a perhaps unmanageable workload. Thus, Steel et al. ( 2021 ) highlight the importance of balancing manageability and relevance when defining the research question. Second, similar to the number of primary studies also the number of meta-analyses in management research has grown strongly in recent years (Geyer-Klingeberg et al. 2020 ; Rauch 2020 ; Schwab 2015 ). Therefore, it is likely that one or several meta-analyses for many topics of high scholarly interest already exist. However, this should not deter researchers from investigating their research questions. One possibility is to consider moderators or mediators of a relationship that have previously been ignored. For example, a meta-analysis about startup performance could investigate the impact of different ways to measure the performance construct (e.g., growth vs. profitability vs. survival time) or certain characteristics of the founders as moderators. Another possibility is to replicate previous meta-analyses and test whether their findings can be confirmed with an updated sample of primary studies or newly developed methods. Frequent replications and updates of meta-analyses are important contributions to cumulative science and are increasingly called for by the research community (Anderson & Kichkha 2017 ; Steel et al. 2021 ). Consistent with its focus on replication studies (Block and Kuckertz 2018 ), MRQ therefore also invites authors to submit replication meta-analyses.

2.2 Step 2: literature search

2.2.1 search strategies.

Similar to conducting a literature review, the search process of a meta-analysis should be systematic, reproducible, and transparent, resulting in a sample that includes all relevant studies (Fisch and Block 2018 ; Gusenbauer and Haddaway 2020 ). There are several identification strategies for relevant primary studies when compiling meta-analytical datasets (Harari et al. 2020 ). First, previous meta-analyses on the same or a related topic may provide lists of included studies that offer a good starting point to identify and become familiar with the relevant literature. This practice is also applicable to topic-related literature reviews, which often summarize the central findings of the reviewed articles in systematic tables. Both article types likely include the most prominent studies of a research field. The most common and important search strategy, however, is a keyword search in electronic databases (Harari et al. 2020 ). This strategy will probably yield the largest number of relevant studies, particularly so-called ‘grey literature’, which may not be considered by literature reviews. Gusenbauer and Haddaway ( 2020 ) provide a detailed overview of 34 scientific databases, of which 18 are multidisciplinary or have a focus on management sciences, along with their suitability for literature synthesis. To prevent biased results due to the scope or journal coverage of one database, researchers should use at least two different databases (DeSimone et al. 2020 ; Martín-Martín et al. 2021 ; Mongeon & Paul-Hus 2016 ). However, a database search can easily lead to an overload of potentially relevant studies. For example, key term searches in Google Scholar for “entrepreneurial intention” and “firm diversification” resulted in more than 660,000 and 810,000 hits, respectively. Footnote 1 Therefore, a precise research question and precise search terms using Boolean operators are advisable (Gusenbauer and Haddaway 2020 ). Addressing the challenge of identifying relevant articles in the growing number of database publications, (semi)automated approaches using text mining and machine learning (Bosco et al. 2017 ; O’Mara-Eves et al. 2015 ; Ouzzani et al. 2016 ; Thomas et al. 2017 ) can also be promising and time-saving search tools in the future. Also, some electronic databases offer the possibility to track forward citations of influential studies and thereby identify further relevant articles. Finally, collecting unpublished or undetected studies through conferences, personal contact with (leading) scholars, or listservs can be strategies to increase the study sample size (Grewal et al. 2018 ; Harari et al. 2020 ; Pigott and Polanin 2020 ).

2.2.2 Study inclusion criteria and sample composition

Next, researchers must decide which studies to include in the meta-analysis. Some guidelines for literature reviews recommend limiting the sample to studies published in renowned academic journals to ensure the quality of findings (e.g., Kraus et al. 2020 ). For meta-analysis, however, Steel et al. ( 2021 ) advocate for the inclusion of all available studies, including grey literature, to prevent selection biases based on availability, cost, familiarity, and language (Rothstein et al. 2005 ), or the “Matthew effect”, which denotes the phenomenon that highly cited articles are found faster than less cited articles (Merton 1968 ). Harrison et al. ( 2017 ) find that the effects of published studies in management are inflated on average by 30% compared to unpublished studies. This so-called publication bias or “file drawer problem” (Rosenthal 1979 ) results from the preference of academia to publish more statistically significant and less statistically insignificant study results. Owen and Li ( 2020 ) showed that publication bias is particularly severe when variables of interest are used as key variables rather than control variables. To consider the true effect size of a target variable or relationship, the inclusion of all types of research outputs is therefore recommended (Polanin et al. 2016 ). Different test procedures to identify publication bias are discussed subsequently in Step 7.

In addition to the decision of whether to include certain study types (i.e., published vs. unpublished studies), there can be other reasons to exclude studies that are identified in the search process. These reasons can be manifold and are primarily related to the specific research question and methodological peculiarities. For example, studies identified by keyword search might not qualify thematically after all, may use unsuitable variable measurements, or may not report usable effect sizes. Furthermore, there might be multiple studies by the same authors using similar datasets. If they do not differ sufficiently in terms of their sample characteristics or variables used, only one of these studies should be included to prevent bias from duplicates (Wood 2008 ; see this article for a detection heuristic).

In general, the screening process should be conducted stepwise, beginning with a removal of duplicate citations from different databases, followed by abstract screening to exclude clearly unsuitable studies and a final full-text screening of the remaining articles (Pigott and Polanin 2020 ). A graphical tool to systematically document the sample selection process is the PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al. 2009 ). Page et al. ( 2021 ) recently presented an updated version of the PRISMA statement, including an extended item checklist and flow diagram to report the study process and findings.

2.3 Step 3: choice of the effect size measure

2.3.1 types of effect sizes.

The two most common meta-analytical effect size measures in management studies are (z-transformed) correlation coefficients and standardized mean differences (Aguinis et al. 2011a ; Geyskens et al. 2009 ). However, meta-analyses in management science and related fields may not be limited to those two effect size measures but rather depend on the subfield of investigation (Borenstein 2009 ; Stanley and Doucouliagos 2012 ). In economics and finance, researchers are more interested in the examination of elasticities and marginal effects extracted from regression models than in pure bivariate correlations (Stanley and Doucouliagos 2012 ). Regression coefficients can also be converted to partial correlation coefficients based on their t-statistics to make regression results comparable across studies (Stanley and Doucouliagos 2012 ). Although some meta-analyses in management research have combined bivariate and partial correlations in their study samples, Aloe ( 2015 ) and Combs et al. ( 2019 ) advise researchers not to use this practice. Most importantly, they argue that the effect size strength of partial correlations depends on the other variables included in the regression model and is therefore incomparable to bivariate correlations (Schmidt and Hunter 2015 ), resulting in a possible bias of the meta-analytic results (Roth et al. 2018 ). We endorse this opinion. If at all, we recommend separate analyses for each measure. In addition to these measures, survival rates, risk ratios or odds ratios, which are common measures in medical research (Borenstein 2009 ), can be suitable effect sizes for specific management research questions, such as understanding the determinants of the survival of startup companies. To summarize, the choice of a suitable effect size is often taken away from the researcher because it is typically dependent on the investigated research question as well as the conventions of the specific research field (Cheung and Vijayakumar 2016 ).

2.3.2 Conversion of effect sizes to a common measure

After having defined the primary effect size measure for the meta-analysis, it might become necessary in the later coding process to convert study findings that are reported in effect sizes that are different from the chosen primary effect size. For example, a study might report only descriptive statistics for two study groups but no correlation coefficient, which is used as the primary effect size measure in the meta-analysis. Different effect size measures can be harmonized using conversion formulae, which are provided by standard method books such as Borenstein et al. ( 2009 ) or Lipsey and Wilson ( 2001 ). There also exist online effect size calculators for meta-analysis. Footnote 2

2.4 Step 4: choice of the analytical method used

Choosing which meta-analytical method to use is directly connected to the research question of the meta-analysis. Research questions in meta-analyses can address a relationship between constructs or an effect of an intervention in a general manner, or they can focus on moderating or mediating effects. There are four meta-analytical methods that are primarily used in contemporary management research (Combs et al. 2019 ; Geyer-Klingeberg et al. 2020 ), which allow the investigation of these different types of research questions: traditional univariate meta-analysis, meta-regression, meta-analytic structural equation modeling, and qualitative meta-analysis (Hoon 2013 ). While the first three are quantitative, the latter summarizes qualitative findings. Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of the three quantitative methods.

2.4.1 Univariate meta-analysis

In its traditional form, a meta-analysis reports a weighted mean effect size for the relationship or intervention of investigation and provides information on the magnitude of variance among primary studies (Aguinis et al. 2011c ; Borenstein et al. 2009 ). Accordingly, it serves as a quantitative synthesis of a research field (Borenstein et al. 2009 ; Geyskens et al. 2009 ). Prominent traditional approaches have been developed, for example, by Hedges and Olkin ( 1985 ) or Hunter and Schmidt ( 1990 , 2004 ). However, going beyond its simple summary function, the traditional approach has limitations in explaining the observed variance among findings (Gonzalez-Mulé and Aguinis 2018 ). To identify moderators (or boundary conditions) of the relationship of interest, meta-analysts can create subgroups and investigate differences between those groups (Borenstein and Higgins 2013 ; Hunter and Schmidt 2004 ). Potential moderators can be study characteristics (e.g., whether a study is published vs. unpublished), sample characteristics (e.g., study country, industry focus, or type of survey/experiment participants), or measurement artifacts (e.g., different types of variable measurements). The univariate approach is thus suitable to identify the overall direction of a relationship and can serve as a good starting point for additional analyses. However, due to its limitations in examining boundary conditions and developing theory, the univariate approach on its own is currently oftentimes viewed as not sufficient (Rauch 2020 ; Shaw and Ertug 2017 ).

2.4.2 Meta-regression analysis

Meta-regression analysis (Hedges and Olkin 1985 ; Lipsey and Wilson 2001 ; Stanley and Jarrell 1989 ) aims to investigate the heterogeneity among observed effect sizes by testing multiple potential moderators simultaneously. In meta-regression, the coded effect size is used as the dependent variable and is regressed on a list of moderator variables. These moderator variables can be categorical variables as described previously in the traditional univariate approach or (semi)continuous variables such as country scores that are merged with the meta-analytical data. Thus, meta-regression analysis overcomes the disadvantages of the traditional approach, which only allows us to investigate moderators singularly using dichotomized subgroups (Combs et al. 2019 ; Gonzalez-Mulé and Aguinis 2018 ). These possibilities allow a more fine-grained analysis of research questions that are related to moderating effects. However, Schmidt ( 2017 ) critically notes that the number of effect sizes in the meta-analytical sample must be sufficiently large to produce reliable results when investigating multiple moderators simultaneously in a meta-regression. For further reading, Tipton et al. ( 2019 ) outline the technical, conceptual, and practical developments of meta-regression over the last decades. Gonzalez-Mulé and Aguinis ( 2018 ) provide an overview of methodological choices and develop evidence-based best practices for future meta-analyses in management using meta-regression.

2.4.3 Meta-analytic structural equation modeling (MASEM)

MASEM is a combination of meta-analysis and structural equation modeling and allows to simultaneously investigate the relationships among several constructs in a path model. Researchers can use MASEM to test several competing theoretical models against each other or to identify mediation mechanisms in a chain of relationships (Bergh et al. 2016 ). This method is typically performed in two steps (Cheung and Chan 2005 ): In Step 1, a pooled correlation matrix is derived, which includes the meta-analytical mean effect sizes for all variable combinations; Step 2 then uses this matrix to fit the path model. While MASEM was based primarily on traditional univariate meta-analysis to derive the pooled correlation matrix in its early years (Viswesvaran and Ones 1995 ), more advanced methods, such as the GLS approach (Becker 1992 , 1995 ) or the TSSEM approach (Cheung and Chan 2005 ), have been subsequently developed. Cheung ( 2015a ) and Jak ( 2015 ) provide an overview of these approaches in their books with exemplary code. For datasets with more complex data structures, Wilson et al. ( 2016 ) also developed a multilevel approach that is related to the TSSEM approach in the second step. Bergh et al. ( 2016 ) discuss nine decision points and develop best practices for MASEM studies.

2.4.4 Qualitative meta-analysis

While the approaches explained above focus on quantitative outcomes of empirical studies, qualitative meta-analysis aims to synthesize qualitative findings from case studies (Hoon 2013 ; Rauch et al. 2014 ). The distinctive feature of qualitative case studies is their potential to provide in-depth information about specific contextual factors or to shed light on reasons for certain phenomena that cannot usually be investigated by quantitative studies (Rauch 2020 ; Rauch et al. 2014 ). In a qualitative meta-analysis, the identified case studies are systematically coded in a meta-synthesis protocol, which is then used to identify influential variables or patterns and to derive a meta-causal network (Hoon 2013 ). Thus, the insights of contextualized and typically nongeneralizable single studies are aggregated to a larger, more generalizable picture (Habersang et al. 2019 ). Although still the exception, this method can thus provide important contributions for academics in terms of theory development (Combs et al., 2019 ; Hoon 2013 ) and for practitioners in terms of evidence-based management or entrepreneurship (Rauch et al. 2014 ). Levitt ( 2018 ) provides a guide and discusses conceptual issues for conducting qualitative meta-analysis in psychology, which is also useful for management researchers.

2.5 Step 5: choice of software

Software solutions to perform meta-analyses range from built-in functions or additional packages of statistical software to software purely focused on meta-analyses and from commercial to open-source solutions. However, in addition to personal preferences, the choice of the most suitable software depends on the complexity of the methods used and the dataset itself (Cheung and Vijayakumar 2016 ). Meta-analysts therefore must carefully check if their preferred software is capable of performing the intended analysis.

Among commercial software providers, Stata (from version 16 on) offers built-in functions to perform various meta-analytical analyses or to produce various plots (Palmer and Sterne 2016 ). For SPSS and SAS, there exist several macros for meta-analyses provided by scholars, such as David B. Wilson or Andy P. Field and Raphael Gillet (Field and Gillett 2010 ). Footnote 3 Footnote 4 For researchers using the open-source software R (R Core Team 2021 ), Polanin et al. ( 2017 ) provide an overview of 63 meta-analysis packages and their functionalities. For new users, they recommend the package metafor (Viechtbauer 2010 ), which includes most necessary functions and for which the author Wolfgang Viechtbauer provides tutorials on his project website. Footnote 5 Footnote 6 In addition to packages and macros for statistical software, templates for Microsoft Excel have also been developed to conduct simple meta-analyses, such as Meta-Essentials by Suurmond et al. ( 2017 ). Footnote 7 Finally, programs purely dedicated to meta-analysis also exist, such as Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (Borenstein et al. 2013 ) or RevMan by The Cochrane Collaboration ( 2020 ).

2.6 Step 6: coding of effect sizes

2.6.1 coding sheet.

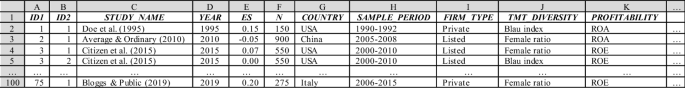

The first step in the coding process is the design of the coding sheet. A universal template does not exist because the design of the coding sheet depends on the methods used, the respective software, and the complexity of the research design. For univariate meta-analysis or meta-regression, data are typically coded in wide format. In its simplest form, when investigating a correlational relationship between two variables using the univariate approach, the coding sheet would contain a column for the study name or identifier, the effect size coded from the primary study, and the study sample size. However, such simple relationships are unlikely in management research because the included studies are typically not identical but differ in several respects. With more complex data structures or moderator variables being investigated, additional columns are added to the coding sheet to reflect the data characteristics. These variables can be coded as dummy, factor, or (semi)continuous variables and later used to perform a subgroup analysis or meta regression. For MASEM, the required data input format can deviate depending on the method used (e.g., TSSEM requires a list of correlation matrices as data input). For qualitative meta-analysis, the coding scheme typically summarizes the key qualitative findings and important contextual and conceptual information (see Hoon ( 2013 ) for a coding scheme for qualitative meta-analysis). Figure 1 shows an exemplary coding scheme for a quantitative meta-analysis on the correlational relationship between top-management team diversity and profitability. In addition to effect and sample sizes, information about the study country, firm type, and variable operationalizations are coded. The list could be extended by further study and sample characteristics.

Exemplary coding sheet for a meta-analysis on the relationship (correlation) between top-management team diversity and profitability

2.6.2 Inclusion of moderator or control variables

It is generally important to consider the intended research model and relevant nontarget variables before coding a meta-analytic dataset. For example, study characteristics can be important moderators or function as control variables in a meta-regression model. Similarly, control variables may be relevant in a MASEM approach to reduce confounding bias. Coding additional variables or constructs subsequently can be arduous if the sample of primary studies is large. However, the decision to include respective moderator or control variables, as in any empirical analysis, should always be based on strong (theoretical) rationales about how these variables can impact the investigated effect (Bernerth and Aguinis 2016 ; Bernerth et al. 2018 ; Thompson and Higgins 2002 ). While substantive moderators refer to theoretical constructs that act as buffers or enhancers of a supposed causal process, methodological moderators are features of the respective research designs that denote the methodological context of the observations and are important to control for systematic statistical particularities (Rudolph et al. 2020 ). Havranek et al. ( 2020 ) provide a list of recommended variables to code as potential moderators. While researchers may have clear expectations about the effects for some of these moderators, the concerns for other moderators may be tentative, and moderator analysis may be approached in a rather exploratory fashion. Thus, we argue that researchers should make full use of the meta-analytical design to obtain insights about potential context dependence that a primary study cannot achieve.

2.6.3 Treatment of multiple effect sizes in a study

A long-debated issue in conducting meta-analyses is whether to use only one or all available effect sizes for the same construct within a single primary study. For meta-analyses in management research, this question is fundamental because many empirical studies, particularly those relying on company databases, use multiple variables for the same construct to perform sensitivity analyses, resulting in multiple relevant effect sizes. In this case, researchers can either (randomly) select a single value, calculate a study average, or use the complete set of effect sizes (Bijmolt and Pieters 2001 ; López-López et al. 2018 ). Multiple effect sizes from the same study enrich the meta-analytic dataset and allow us to investigate the heterogeneity of the relationship of interest, such as different variable operationalizations (López-López et al. 2018 ; Moeyaert et al. 2017 ). However, including more than one effect size from the same study violates the independency assumption of observations (Cheung 2019 ; López-López et al. 2018 ), which can lead to biased results and erroneous conclusions (Gooty et al. 2021 ). We follow the recommendation of current best practice guides to take advantage of using all available effect size observations but to carefully consider interdependencies using appropriate methods such as multilevel models, panel regression models, or robust variance estimation (Cheung 2019 ; Geyer-Klingeberg et al. 2020 ; Gooty et al. 2021 ; López-López et al. 2018 ; Moeyaert et al. 2017 ).

2.7 Step 7: analysis

2.7.1 outlier analysis and tests for publication bias.

Before conducting the primary analysis, some preliminary sensitivity analyses might be necessary, which should ensure the robustness of the meta-analytical findings (Rudolph et al. 2020 ). First, influential outlier observations could potentially bias the observed results, particularly if the number of total effect sizes is small. Several statistical methods can be used to identify outliers in meta-analytical datasets (Aguinis et al. 2013 ; Viechtbauer and Cheung 2010 ). However, there is a debate about whether to keep or omit these observations. Anyhow, relevant studies should be closely inspected to infer an explanation about their deviating results. As in any other primary study, outliers can be a valid representation, albeit representing a different population, measure, construct, design or procedure. Thus, inferences about outliers can provide the basis to infer potential moderators (Aguinis et al. 2013 ; Steel et al. 2021 ). On the other hand, outliers can indicate invalid research, for instance, when unrealistically strong correlations are due to construct overlap (i.e., lack of a clear demarcation between independent and dependent variables), invalid measures, or simply typing errors when coding effect sizes. An advisable step is therefore to compare the results both with and without outliers and base the decision on whether to exclude outlier observations with careful consideration (Geyskens et al. 2009 ; Grewal et al. 2018 ; Kepes et al. 2013 ). However, instead of simply focusing on the size of the outlier, its leverage should be considered. Thus, Viechtbauer and Cheung ( 2010 ) propose considering a combination of standardized deviation and a study’s leverage.

Second, as mentioned in the context of a literature search, potential publication bias may be an issue. Publication bias can be examined in multiple ways (Rothstein et al. 2005 ). First, the funnel plot is a simple graphical tool that can provide an overview of the effect size distribution and help to detect publication bias (Stanley and Doucouliagos 2010 ). A funnel plot can also support in identifying potential outliers. As mentioned above, a graphical display of deviation (e.g., studentized residuals) and leverage (Cook’s distance) can help detect the presence of outliers and evaluate their influence (Viechtbauer and Cheung 2010 ). Moreover, several statistical procedures can be used to test for publication bias (Harrison et al. 2017 ; Kepes et al. 2012 ), including subgroup comparisons between published and unpublished studies, Begg and Mazumdar’s ( 1994 ) rank correlation test, cumulative meta-analysis (Borenstein et al. 2009 ), the trim and fill method (Duval and Tweedie 2000a , b ), Egger et al.’s ( 1997 ) regression test, failsafe N (Rosenthal 1979 ), or selection models (Hedges and Vevea 2005 ; Vevea and Woods 2005 ). In examining potential publication bias, Kepes et al. ( 2012 ) and Harrison et al. ( 2017 ) both recommend not relying only on a single test but rather using multiple conceptionally different test procedures (i.e., the so-called “triangulation approach”).

2.7.2 Model choice

After controlling and correcting for the potential presence of impactful outliers or publication bias, the next step in meta-analysis is the primary analysis, where meta-analysts must decide between two different types of models that are based on different assumptions: fixed-effects and random-effects (Borenstein et al. 2010 ). Fixed-effects models assume that all observations share a common mean effect size, which means that differences are only due to sampling error, while random-effects models assume heterogeneity and allow for a variation of the true effect sizes across studies (Borenstein et al. 2010 ; Cheung and Vijayakumar 2016 ; Hunter and Schmidt 2004 ). Both models are explained in detail in standard textbooks (e.g., Borenstein et al. 2009 ; Hunter and Schmidt 2004 ; Lipsey and Wilson 2001 ).

In general, the presence of heterogeneity is likely in management meta-analyses because most studies do not have identical empirical settings, which can yield different effect size strengths or directions for the same investigated phenomenon. For example, the identified studies have been conducted in different countries with different institutional settings, or the type of study participants varies (e.g., students vs. employees, blue-collar vs. white-collar workers, or manufacturing vs. service firms). Thus, the vast majority of meta-analyses in management research and related fields use random-effects models (Aguinis et al. 2011a ). In a meta-regression, the random-effects model turns into a so-called mixed-effects model because moderator variables are added as fixed effects to explain the impact of observed study characteristics on effect size variations (Raudenbush 2009 ).

2.8 Step 8: reporting results

2.8.1 reporting in the article.

The final step in performing a meta-analysis is reporting its results. Most importantly, all steps and methodological decisions should be comprehensible to the reader. DeSimone et al. ( 2020 ) provide an extensive checklist for journal reviewers of meta-analytical studies. This checklist can also be used by authors when performing their analyses and reporting their results to ensure that all important aspects have been addressed. Alternative checklists are provided, for example, by Appelbaum et al. ( 2018 ) or Page et al. ( 2021 ). Similarly, Levitt et al. ( 2018 ) provide a detailed guide for qualitative meta-analysis reporting standards.

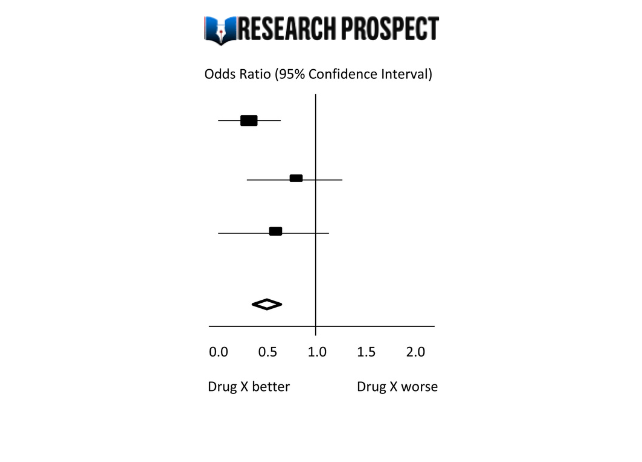

For quantitative meta-analyses, tables reporting results should include all important information and test statistics, including mean effect sizes; standard errors and confidence intervals; the number of observations and study samples included; and heterogeneity measures. If the meta-analytic sample is rather small, a forest plot provides a good overview of the different findings and their accuracy. However, this figure will be less feasible for meta-analyses with several hundred effect sizes included. Also, results displayed in the tables and figures must be explained verbally in the results and discussion sections. Most importantly, authors must answer the primary research question, i.e., whether there is a positive, negative, or no relationship between the variables of interest, or whether the examined intervention has a certain effect. These results should be interpreted with regard to their magnitude (or significance), both economically and statistically. However, when discussing meta-analytical results, authors must describe the complexity of the results, including the identified heterogeneity and important moderators, future research directions, and theoretical relevance (DeSimone et al. 2019 ). In particular, the discussion of identified heterogeneity and underlying moderator effects is critical; not including this information can lead to false conclusions among readers, who interpret the reported mean effect size as universal for all included primary studies and ignore the variability of findings when citing the meta-analytic results in their research (Aytug et al. 2012 ; DeSimone et al. 2019 ).

2.8.2 Open-science practices

Another increasingly important topic is the public provision of meta-analytical datasets and statistical codes via open-source repositories. Open-science practices allow for results validation and for the use of coded data in subsequent meta-analyses ( Polanin et al. 2020 ), contributing to the development of cumulative science. Steel et al. ( 2021 ) refer to open science meta-analyses as a step towards “living systematic reviews” (Elliott et al. 2017 ) with continuous updates in real time. MRQ supports this development and encourages authors to make their datasets publicly available. Moreau and Gamble ( 2020 ), for example, provide various templates and video tutorials to conduct open science meta-analyses. There exist several open science repositories, such as the Open Science Foundation (OSF; for a tutorial, see Soderberg 2018 ), to preregister and make documents publicly available. Furthermore, several initiatives in the social sciences have been established to develop dynamic meta-analyses, such as metaBUS (Bosco et al. 2015 , 2017 ), MetaLab (Bergmann et al. 2018 ), or PsychOpen CAMA (Burgard et al. 2021 ).

3 Conclusion

This editorial provides a comprehensive overview of the essential steps in conducting and reporting a meta-analysis with references to more in-depth methodological articles. It also serves as a guide for meta-analyses submitted to MRQ and other management journals. MRQ welcomes all types of meta-analyses from all subfields and disciplines of management research.

Gusenbauer and Haddaway ( 2020 ), however, point out that Google Scholar is not appropriate as a primary search engine due to a lack of reproducibility of search results.

One effect size calculator by David B. Wilson is accessible via: https://www.campbellcollaboration.org/escalc/html/EffectSizeCalculator-Home.php .

The macros of David B. Wilson can be downloaded from: http://mason.gmu.edu/~dwilsonb/ .

The macros of Field and Gillet ( 2010 ) can be downloaded from: https://www.discoveringstatistics.com/repository/fieldgillett/how_to_do_a_meta_analysis.html .

The tutorials can be found via: https://www.metafor-project.org/doku.php .

Metafor does currently not provide functions to conduct MASEM. For MASEM, users can, for instance, use the package metaSEM (Cheung 2015b ).

The workbooks can be downloaded from: https://www.erim.eur.nl/research-support/meta-essentials/ .

Aguinis H, Dalton DR, Bosco FA, Pierce CA, Dalton CM (2011a) Meta-analytic choices and judgment calls: Implications for theory building and testing, obtained effect sizes, and scholarly impact. J Manag 37(1):5–38

Google Scholar

Aguinis H, Gottfredson RK, Joo H (2013) Best-practice recommendations for defining, identifying, and handling outliers. Organ Res Methods 16(2):270–301

Article Google Scholar

Aguinis H, Gottfredson RK, Wright TA (2011b) Best-practice recommendations for estimating interaction effects using meta-analysis. J Organ Behav 32(8):1033–1043

Aguinis H, Pierce CA, Bosco FA, Dalton DR, Dalton CM (2011c) Debunking myths and urban legends about meta-analysis. Organ Res Methods 14(2):306–331

Aloe AM (2015) Inaccuracy of regression results in replacing bivariate correlations. Res Synth Methods 6(1):21–27

Anderson RG, Kichkha A (2017) Replication, meta-analysis, and research synthesis in economics. Am Econ Rev 107(5):56–59

Appelbaum M, Cooper H, Kline RB, Mayo-Wilson E, Nezu AM, Rao SM (2018) Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: the APA publications and communications BOARD task force report. Am Psychol 73(1):3–25

Aytug ZG, Rothstein HR, Zhou W, Kern MC (2012) Revealed or concealed? Transparency of procedures, decisions, and judgment calls in meta-analyses. Organ Res Methods 15(1):103–133

Begg CB, Mazumdar M (1994) Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50(4):1088–1101. https://doi.org/10.2307/2533446

Bergh DD, Aguinis H, Heavey C, Ketchen DJ, Boyd BK, Su P, Lau CLL, Joo H (2016) Using meta-analytic structural equation modeling to advance strategic management research: Guidelines and an empirical illustration via the strategic leadership-performance relationship. Strateg Manag J 37(3):477–497

Becker BJ (1992) Using results from replicated studies to estimate linear models. J Educ Stat 17(4):341–362

Becker BJ (1995) Corrections to “Using results from replicated studies to estimate linear models.” J Edu Behav Stat 20(1):100–102

Bergmann C, Tsuji S, Piccinini PE, Lewis ML, Braginsky M, Frank MC, Cristia A (2018) Promoting replicability in developmental research through meta-analyses: Insights from language acquisition research. Child Dev 89(6):1996–2009

Bernerth JB, Aguinis H (2016) A critical review and best-practice recommendations for control variable usage. Pers Psychol 69(1):229–283

Bernerth JB, Cole MS, Taylor EC, Walker HJ (2018) Control variables in leadership research: A qualitative and quantitative review. J Manag 44(1):131–160

Bijmolt TH, Pieters RG (2001) Meta-analysis in marketing when studies contain multiple measurements. Mark Lett 12(2):157–169

Block J, Kuckertz A (2018) Seven principles of effective replication studies: Strengthening the evidence base of management research. Manag Rev Quart 68:355–359

Borenstein M (2009) Effect sizes for continuous data. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC (eds) The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. Russell Sage Foundation, pp 221–235

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR (2009) Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley, Chichester

Book Google Scholar

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR (2010) A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 1(2):97–111

Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H (2013) Comprehensive meta-analysis (version 3). Biostat, Englewood, NJ

Borenstein M, Higgins JP (2013) Meta-analysis and subgroups. Prev Sci 14(2):134–143

Bosco FA, Steel P, Oswald FL, Uggerslev K, Field JG (2015) Cloud-based meta-analysis to bridge science and practice: Welcome to metaBUS. Person Assess Decis 1(1):3–17

Bosco FA, Uggerslev KL, Steel P (2017) MetaBUS as a vehicle for facilitating meta-analysis. Hum Resour Manag Rev 27(1):237–254

Burgard T, Bošnjak M, Studtrucker R (2021) Community-augmented meta-analyses (CAMAs) in psychology: potentials and current systems. Zeitschrift Für Psychologie 229(1):15–23

Cheung MWL (2015a) Meta-analysis: A structural equation modeling approach. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester

Cheung MWL (2015b) metaSEM: An R package for meta-analysis using structural equation modeling. Front Psychol 5:1521

Cheung MWL (2019) A guide to conducting a meta-analysis with non-independent effect sizes. Neuropsychol Rev 29(4):387–396

Cheung MWL, Chan W (2005) Meta-analytic structural equation modeling: a two-stage approach. Psychol Methods 10(1):40–64

Cheung MWL, Vijayakumar R (2016) A guide to conducting a meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rev 26(2):121–128

Combs JG, Crook TR, Rauch A (2019) Meta-analytic research in management: contemporary approaches unresolved controversies and rising standards. J Manag Stud 56(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12427

DeSimone JA, Köhler T, Schoen JL (2019) If it were only that easy: the use of meta-analytic research by organizational scholars. Organ Res Methods 22(4):867–891. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428118756743

DeSimone JA, Brannick MT, O’Boyle EH, Ryu JW (2020) Recommendations for reviewing meta-analyses in organizational research. Organ Res Methods 56:455–463

Duval S, Tweedie R (2000a) Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 56(2):455–463

Duval S, Tweedie R (2000b) A nonparametric “trim and fill” method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. J Am Stat Assoc 95(449):89–98

Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315(7109):629–634

Eisend M (2017) Meta-Analysis in advertising research. J Advert 46(1):21–35

Elliott JH, Synnot A, Turner T, Simmons M, Akl EA, McDonald S, Salanti G, Meerpohl J, MacLehose H, Hilton J, Tovey D, Shemilt I, Thomas J (2017) Living systematic review: 1. Introduction—the why, what, when, and how. J Clin Epidemiol 91:2330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.08.010

Field AP, Gillett R (2010) How to do a meta-analysis. Br J Math Stat Psychol 63(3):665–694

Fisch C, Block J (2018) Six tips for your (systematic) literature review in business and management research. Manag Rev Quart 68:103–106

Fortunato S, Bergstrom CT, Börner K, Evans JA, Helbing D, Milojević S, Petersen AM, Radicchi F, Sinatra R, Uzzi B, Vespignani A (2018) Science of science. Science 359(6379). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao0185

Geyer-Klingeberg J, Hang M, Rathgeber A (2020) Meta-analysis in finance research: Opportunities, challenges, and contemporary applications. Int Rev Finan Anal 71:101524

Geyskens I, Krishnan R, Steenkamp JBE, Cunha PV (2009) A review and evaluation of meta-analysis practices in management research. J Manag 35(2):393–419

Glass GV (2015) Meta-analysis at middle age: a personal history. Res Synth Methods 6(3):221–231

Gonzalez-Mulé E, Aguinis H (2018) Advancing theory by assessing boundary conditions with metaregression: a critical review and best-practice recommendations. J Manag 44(6):2246–2273

Gooty J, Banks GC, Loignon AC, Tonidandel S, Williams CE (2021) Meta-analyses as a multi-level model. Organ Res Methods 24(2):389–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428119857471

Grewal D, Puccinelli N, Monroe KB (2018) Meta-analysis: integrating accumulated knowledge. J Acad Mark Sci 46(1):9–30

Gurevitch J, Koricheva J, Nakagawa S, Stewart G (2018) Meta-analysis and the science of research synthesis. Nature 555(7695):175–182

Gusenbauer M, Haddaway NR (2020) Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Res Synth Methods 11(2):181–217

Habersang S, Küberling-Jost J, Reihlen M, Seckler C (2019) A process perspective on organizational failure: a qualitative meta-analysis. J Manage Stud 56(1):19–56

Harari MB, Parola HR, Hartwell CJ, Riegelman A (2020) Literature searches in systematic reviews and meta-analyses: A review, evaluation, and recommendations. J Vocat Behav 118:103377

Harrison JS, Banks GC, Pollack JM, O’Boyle EH, Short J (2017) Publication bias in strategic management research. J Manag 43(2):400–425

Havránek T, Stanley TD, Doucouliagos H, Bom P, Geyer-Klingeberg J, Iwasaki I, Reed WR, Rost K, Van Aert RCM (2020) Reporting guidelines for meta-analysis in economics. J Econ Surveys 34(3):469–475

Hedges LV, Olkin I (1985) Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Academic Press, Orlando

Hedges LV, Vevea JL (2005) Selection methods approaches. In: Rothstein HR, Sutton A, Borenstein M (eds) Publication bias in meta-analysis: prevention, assessment, and adjustments. Wiley, Chichester, pp 145–174

Hoon C (2013) Meta-synthesis of qualitative case studies: an approach to theory building. Organ Res Methods 16(4):522–556

Hunter JE, Schmidt FL (1990) Methods of meta-analysis: correcting error and bias in research findings. Sage, Newbury Park

Hunter JE, Schmidt FL (2004) Methods of meta-analysis: correcting error and bias in research findings, 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Hunter JE, Schmidt FL, Jackson GB (1982) Meta-analysis: cumulating research findings across studies. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills

Jak S (2015) Meta-analytic structural equation modelling. Springer, New York, NY

Kepes S, Banks GC, McDaniel M, Whetzel DL (2012) Publication bias in the organizational sciences. Organ Res Methods 15(4):624–662

Kepes S, McDaniel MA, Brannick MT, Banks GC (2013) Meta-analytic reviews in the organizational sciences: Two meta-analytic schools on the way to MARS (the Meta-Analytic Reporting Standards). J Bus Psychol 28(2):123–143

Kraus S, Breier M, Dasí-Rodríguez S (2020) The art of crafting a systematic literature review in entrepreneurship research. Int Entrepreneur Manag J 16(3):1023–1042

Levitt HM (2018) How to conduct a qualitative meta-analysis: tailoring methods to enhance methodological integrity. Psychother Res 28(3):367–378

Levitt HM, Bamberg M, Creswell JW, Frost DM, Josselson R, Suárez-Orozco C (2018) Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: the APA publications and communications board task force report. Am Psychol 73(1):26

Lipsey MW, Wilson DB (2001) Practical meta-analysis. Sage Publications, Inc.

López-López JA, Page MJ, Lipsey MW, Higgins JP (2018) Dealing with effect size multiplicity in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Res Synth Methods 9(3):336–351

Martín-Martín A, Thelwall M, Orduna-Malea E, López-Cózar ED (2021) Google Scholar, Microsoft Academic, Scopus, Dimensions, Web of Science, and OpenCitations’ COCI: a multidisciplinary comparison of coverage via citations. Scientometrics 126(1):871–906

Merton RK (1968) The Matthew effect in science: the reward and communication systems of science are considered. Science 159(3810):56–63

Moeyaert M, Ugille M, Natasha Beretvas S, Ferron J, Bunuan R, Van den Noortgate W (2017) Methods for dealing with multiple outcomes in meta-analysis: a comparison between averaging effect sizes, robust variance estimation and multilevel meta-analysis. Int J Soc Res Methodol 20(6):559–572

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS medicine. 6(7):e1000097

Mongeon P, Paul-Hus A (2016) The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: a comparative analysis. Scientometrics 106(1):213–228

Moreau D, Gamble B (2020) Conducting a meta-analysis in the age of open science: Tools, tips, and practical recommendations. Psychol Methods. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000351

O’Mara-Eves A, Thomas J, McNaught J, Miwa M, Ananiadou S (2015) Using text mining for study identification in systematic reviews: a systematic review of current approaches. Syst Rev 4(1):1–22

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A (2016) Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 5(1):1–10

Owen E, Li Q (2021) The conditional nature of publication bias: a meta-regression analysis. Polit Sci Res Methods 9(4):867–877

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E,McDonald S,McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Palmer TM, Sterne JAC (eds) (2016) Meta-analysis in stata: an updated collection from the stata journal, 2nd edn. Stata Press, College Station, TX

Pigott TD, Polanin JR (2020) Methodological guidance paper: High-quality meta-analysis in a systematic review. Rev Educ Res 90(1):24–46

Polanin JR, Tanner-Smith EE, Hennessy EA (2016) Estimating the difference between published and unpublished effect sizes: a meta-review. Rev Educ Res 86(1):207–236

Polanin JR, Hennessy EA, Tanner-Smith EE (2017) A review of meta-analysis packages in R. J Edu Behav Stat 42(2):206–242

Polanin JR, Hennessy EA, Tsuji S (2020) Transparency and reproducibility of meta-analyses in psychology: a meta-review. Perspect Psychol Sci 15(4):1026–1041. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916209064

R Core Team (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing . R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/ .

Rauch A (2020) Opportunities and threats in reviewing entrepreneurship theory and practice. Entrep Theory Pract 44(5):847–860

Rauch A, van Doorn R, Hulsink W (2014) A qualitative approach to evidence–based entrepreneurship: theoretical considerations and an example involving business clusters. Entrep Theory Pract 38(2):333–368

Raudenbush SW (2009) Analyzing effect sizes: Random-effects models. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC (eds) The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis, 2nd edn. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, NY, pp 295–315

Rosenthal R (1979) The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychol Bull 86(3):638

Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Borenstein M (2005) Publication bias in meta-analysis: prevention, assessment and adjustments. Wiley, Chichester

Roth PL, Le H, Oh I-S, Van Iddekinge CH, Bobko P (2018) Using beta coefficients to impute missing correlations in meta-analysis research: Reasons for caution. J Appl Psychol 103(6):644–658. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000293

Rudolph CW, Chang CK, Rauvola RS, Zacher H (2020) Meta-analysis in vocational behavior: a systematic review and recommendations for best practices. J Vocat Behav 118:103397

Schmidt FL (2017) Statistical and measurement pitfalls in the use of meta-regression in meta-analysis. Career Dev Int 22(5):469–476

Schmidt FL, Hunter JE (2015) Methods of meta-analysis: correcting error and bias in research findings. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Schwab A (2015) Why all researchers should report effect sizes and their confidence intervals: Paving the way for meta–analysis and evidence–based management practices. Entrepreneurship Theory Pract 39(4):719–725. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12158

Shaw JD, Ertug G (2017) The suitability of simulations and meta-analyses for submissions to Academy of Management Journal. Acad Manag J 60(6):2045–2049

Soderberg CK (2018) Using OSF to share data: A step-by-step guide. Adv Methods Pract Psychol Sci 1(1):115–120

Stanley TD, Doucouliagos H (2010) Picture this: a simple graph that reveals much ado about research. J Econ Surveys 24(1):170–191

Stanley TD, Doucouliagos H (2012) Meta-regression analysis in economics and business. Routledge, London

Stanley TD, Jarrell SB (1989) Meta-regression analysis: a quantitative method of literature surveys. J Econ Surveys 3:54–67

Steel P, Beugelsdijk S, Aguinis H (2021) The anatomy of an award-winning meta-analysis: Recommendations for authors, reviewers, and readers of meta-analytic reviews. J Int Bus Stud 52(1):23–44

Suurmond R, van Rhee H, Hak T (2017) Introduction, comparison, and validation of Meta-Essentials: a free and simple tool for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 8(4):537–553

The Cochrane Collaboration (2020). Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program] (Version 5.4).

Thomas J, Noel-Storr A, Marshall I, Wallace B, McDonald S, Mavergames C, Glasziou P, Shemilt I, Synnot A, Turner T, Elliot J (2017) Living systematic reviews: 2. Combining human and machine effort. J Clin Epidemiol 91:31–37

Thompson SG, Higgins JP (2002) How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med 21(11):1559–1573

Tipton E, Pustejovsky JE, Ahmadi H (2019) A history of meta-regression: technical, conceptual, and practical developments between 1974 and 2018. Res Synth Methods 10(2):161–179

Vevea JL, Woods CM (2005) Publication bias in research synthesis: Sensitivity analysis using a priori weight functions. Psychol Methods 10(4):428–443

Viechtbauer W (2010) Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw 36(3):1–48

Viechtbauer W, Cheung MWL (2010) Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 1(2):112–125

Viswesvaran C, Ones DS (1995) Theory testing: combining psychometric meta-analysis and structural equations modeling. Pers Psychol 48(4):865–885

Wilson SJ, Polanin JR, Lipsey MW (2016) Fitting meta-analytic structural equation models with complex datasets. Res Synth Methods 7(2):121–139. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1199

Wood JA (2008) Methodology for dealing with duplicate study effects in a meta-analysis. Organ Res Methods 11(1):79–95

Download references

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Luxembourg, Luxembourg, Luxembourg

Christopher Hansen

Leibniz Institute for Psychology (ZPID), Trier, Germany

Holger Steinmetz

Trier University, Trier, Germany

Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Wittener Institut Für Familienunternehmen, Universität Witten/Herdecke, Witten, Germany

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jörn Block .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

See Table 1 .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Hansen, C., Steinmetz, H. & Block, J. How to conduct a meta-analysis in eight steps: a practical guide. Manag Rev Q 72 , 1–19 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-021-00247-4

Download citation

Published : 30 November 2021

Issue Date : February 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-021-00247-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Data Analysis in Research: Types & Methods

Content Index

Why analyze data in research?

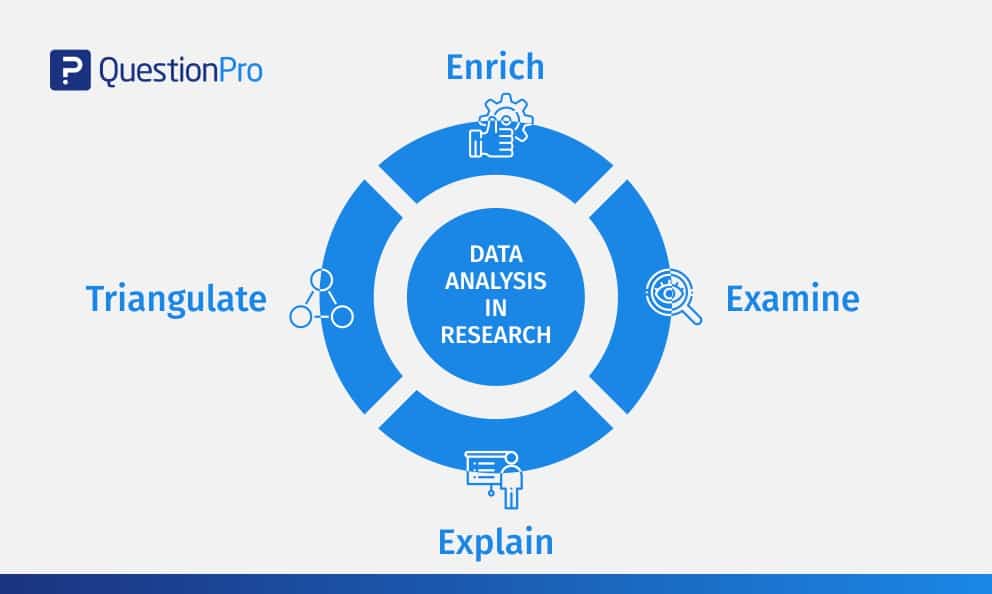

Types of data in research, finding patterns in the qualitative data, methods used for data analysis in qualitative research, preparing data for analysis, methods used for data analysis in quantitative research, considerations in research data analysis, what is data analysis in research.

Definition of research in data analysis: According to LeCompte and Schensul, research data analysis is a process used by researchers to reduce data to a story and interpret it to derive insights. The data analysis process helps reduce a large chunk of data into smaller fragments, which makes sense.

Three essential things occur during the data analysis process — the first is data organization . Summarization and categorization together contribute to becoming the second known method used for data reduction. It helps find patterns and themes in the data for easy identification and linking. The third and last way is data analysis – researchers do it in both top-down and bottom-up fashion.

LEARN ABOUT: Research Process Steps

On the other hand, Marshall and Rossman describe data analysis as a messy, ambiguous, and time-consuming but creative and fascinating process through which a mass of collected data is brought to order, structure and meaning.

We can say that “the data analysis and data interpretation is a process representing the application of deductive and inductive logic to the research and data analysis.”

Researchers rely heavily on data as they have a story to tell or research problems to solve. It starts with a question, and data is nothing but an answer to that question. But, what if there is no question to ask? Well! It is possible to explore data even without a problem – we call it ‘Data Mining’, which often reveals some interesting patterns within the data that are worth exploring.

Irrelevant to the type of data researchers explore, their mission and audiences’ vision guide them to find the patterns to shape the story they want to tell. One of the essential things expected from researchers while analyzing data is to stay open and remain unbiased toward unexpected patterns, expressions, and results. Remember, sometimes, data analysis tells the most unforeseen yet exciting stories that were not expected when initiating data analysis. Therefore, rely on the data you have at hand and enjoy the journey of exploratory research.

Create a Free Account

Every kind of data has a rare quality of describing things after assigning a specific value to it. For analysis, you need to organize these values, processed and presented in a given context, to make it useful. Data can be in different forms; here are the primary data types.