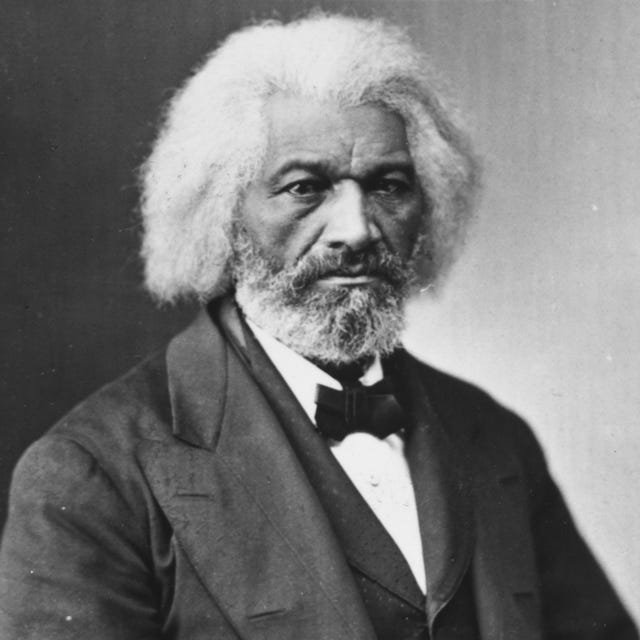

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass was a leader in the abolitionist movement, an early champion of women’s rights and author of ‘Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.’

(1818-1895)

Who Was Frederick Douglass?

Among Douglass’ writings are several autobiographies eloquently describing his experiences in slavery and his life after the Civil War , including the well-known work Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave .

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born around 1818 into slavery in Talbot County, Maryland. As was often the case with slaves, the exact year and date of Douglass' birth are unknown, though later in life he chose to celebrate it on February 14.

Douglass initially lived with his maternal grandmother, Betty Bailey. At a young age, Douglass was selected to live in the home of the plantation owners, one of whom may have been his father.

His mother, who was an intermittent presence in his life, died when he was around 10.

Learning to Read and Write

Defying a ban on teaching slaves to read and write, Baltimore slaveholder Hugh Auld’s wife Sophia taught Douglass the alphabet when he was around 12. When Auld forbade his wife to offer more lessons, Douglass continued to learn from white children and others in the neighborhood.

It was through reading that Douglass’ ideological opposition to slavery began to take shape. He read newspapers avidly and sought out political writing and literature as much as possible. In later years, Douglass credited The Columbian Orator with clarifying and defining his views on human rights.

Douglass shared his newfound knowledge with other enslaved people. Hired out to William Freeland, he taught other slaves on the plantation to read the New Testament at a weekly church service.

Interest was so great that in any week, more than 40 slaves would attend lessons. Although Freeland did not interfere with the lessons, other local slave owners were less understanding. Armed with clubs and stones, they dispersed the congregation permanently.

With Douglass moving between the Aulds, he was later made to work for Edward Covey, who had a reputation as a "slave-breaker.” Covey’s constant abuse nearly broke the 16-year-old Douglass psychologically. Eventually, however, Douglass fought back, in a scene rendered powerfully in his first autobiography.

After losing a physical confrontation with Douglass, Covey never beat him again. Douglass tried to escape from slavery twice before he finally succeeded.

Wife and Children

Douglass married Anna Murray, a free Black woman, on September 15, 1838. Douglass had fallen in love with Murray, who assisted him in his final attempt to escape slavery in Baltimore.

On September 3, 1838, Douglass boarded a train to Havre de Grace, Maryland. Murray had provided him with some of her savings and a sailor's uniform. He carried identification papers obtained from a free Black seaman. Douglass made his way to the safe house of abolitionist David Ruggles in New York in less than 24 hours.

Once he had arrived, Douglass sent for Murray to meet him in New York, where they married and adopted the name of Johnson to disguise Douglass’ identity. Anna and Frederick then settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts, which had a thriving free Black community. There they adopted Douglass as their married name.

Douglass and Anna had five children together: Rosetta, Lewis Henry, Frederick Jr., Charles Redmond and Annie, who died at the age of 10. Charles and Rosetta assisted their father in the production of his newspaper The North Star . Anna remained a loyal supporter of Douglass' public work, despite marital strife caused by his relationships with several other women.

After Anna’s death, Douglass married Helen Pitts, a feminist from Honeoye, New York. Pitts was the daughter of Gideon Pitts Jr., an abolitionist colleague. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College , Pitts worked on a radical feminist publication and shared many of Douglass’ moral principles.

Their marriage caused considerable controversy, since Pitts was white and nearly 20 years younger than Douglass. Douglass’ children were especially displeased with the relationship. Nonetheless, Douglass and Pitts remained married until his death 11 years later.

Abolitionist

After settling as a free man with his wife Anna in New Bedford in 1838, Douglass was eventually asked to tell his story at abolitionist meetings, and he became a regular anti-slavery lecturer.

The founder of the weekly journal The Liberator , William Lloyd Garrison , was impressed with Douglass’ strength and rhetorical skill and wrote of him in his newspaper. Several days after the story ran, Douglass delivered his first speech at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society's annual convention in Nantucket.

Crowds were not always hospitable to Douglass. While participating in an 1843 lecture tour through the Midwest, Douglass was chased and beaten by an angry mob before being rescued by a local Quaker family.

Following the publication of his first autobiography in 1845, Douglass traveled overseas to evade recapture. He set sail for Liverpool on August 16, 1845, and eventually arrived in Ireland as the Potato Famine was beginning. He remained in Ireland and Britain for two years, speaking to large crowds on the evils of slavery.

During this time, Douglass’ British supporters gathered funds to purchase his legal freedom. In 1847, the famed writer and orator returned to the United States a free man.

'The North Star'

Upon his return, Douglass produced some abolitionist newspapers: The North Star , Frederick Douglass Weekly , Frederick Douglass' Paper , Douglass' Monthly and New National Era .

The motto of The North Star was "Right is of no Sex – Truth is of no Color – God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren."

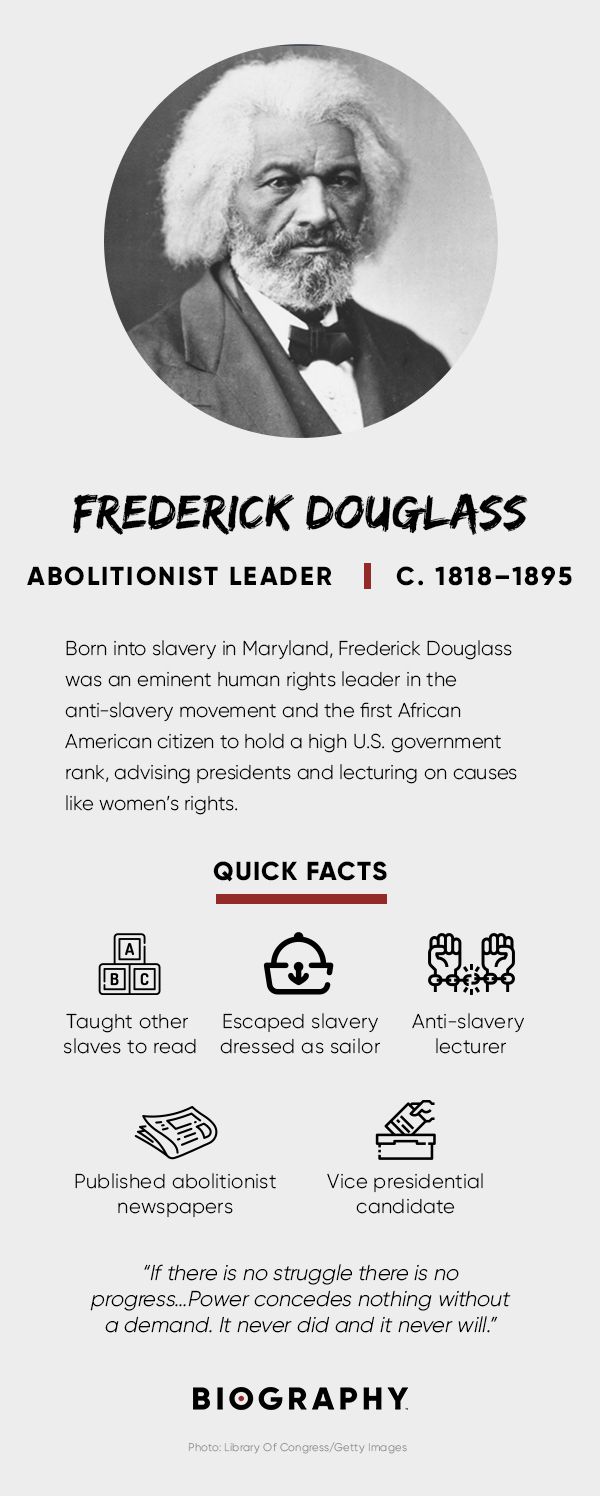

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S FREDERICK DOUGLASS FACT CARD

'Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass'

In New Bedford, Massachusetts, Douglass joined a Black church and regularly attended abolitionist meetings. He also subscribed to Garrison's The Liberator .

At the urging of Garrison, Douglass wrote and published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave , in 1845. The book was a bestseller in the United States and was translated into several European languages.

Although the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass garnered Douglass many fans, some critics expressed doubt that a former enslaved person with no formal education could have produced such elegant prose.

Other Books by Frederick Douglass

Douglass published three versions of his autobiography during his lifetime, revising and expanding on his work each time. My Bondage and My Freedom appeared in 1855.

In 1881, Douglass published Life and Times of Frederick Douglass , which he revised in 1892.

Women’s Rights

In addition to abolition, Douglass became an outspoken supporter of women’s rights. In 1848, he was the only African American to attend the Seneca Falls convention on women's rights. Elizabeth Cady Stanton asked the assembly to pass a resolution stating the goal of women's suffrage. Many attendees opposed the idea.

Douglass, however, stood and spoke eloquently in favor, arguing that he could not accept the right to vote as a Black man if women could not also claim that right. The resolution passed.

Yet Douglass would later come into conflict with women’s rights activists for supporting the Fifteenth Amendment , which banned suffrage discrimination based on race while upholding sex-based restrictions.

Civil War and Reconstruction

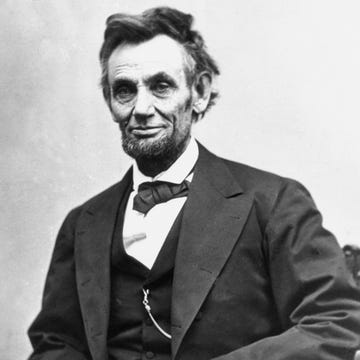

By the time of the Civil War , Douglass was one of the most famous Black men in the country. He used his status to influence the role of African Americans in the war and their status in the country. In 1863, Douglass conferred with President Abraham Lincoln regarding the treatment of Black soldiers, and later with President Andrew Johnson on the subject of Black suffrage.

President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation , which took effect on January 1, 1863, declared the freedom of enslaved people in Confederate territory. Despite this victory, Douglass supported John C. Frémont over Lincoln in the 1864 election, citing his disappointment that Lincoln did not publicly endorse suffrage for Black freedmen.

Slavery everywhere in the United States was subsequently outlawed by the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution .

Douglass was appointed to several political positions following the war. He served as president of the Freedman's Savings Bank and as chargé d'affaires for the Dominican Republic.

After two years, he resigned from his ambassadorship over objections to the particulars of U.S. government policy. He was later appointed minister-resident and consul-general to the Republic of Haiti, a post he held between 1889 and 1891.

In 1877, Douglass visited one of his former owners, Thomas Auld. Douglass had met with Auld's daughter, Amanda Auld Sears, years before. The visit held personal significance for Douglass, although some criticized him for the reconciliation.

Vice Presidential Candidate

Douglass became the first African American nominated for vice president of the United States as Victoria Woodhull 's running mate on the Equal Rights Party ticket in 1872.

Nominated without his knowledge or consent, Douglass never campaigned. Nonetheless, his nomination marked the first time that an African American appeared on a presidential ballot.

Douglass died on February 20, 1895, of a massive heart attack or stroke shortly after returning from a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C. He was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Frederick Douglass

- Birth Year: 1818

- Birth State: Maryland

- Birth City: Tuckahoe

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Frederick Douglass was a leader in the abolitionist movement, an early champion of women’s rights and author of ‘Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.’

- Interesting Facts

- Frederick Douglass first learned to read and write at the age of 12 from a Baltimore slaveholder's wife.

- To much controversy, Douglass married white abolitionist feminist Helen Pitts.

- Douglass became the first African American nominated for vice president of the United States.

- Death Year: 1895

- Death date: February 20, 1895

- Death City: Washington, D.C.

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Frederick Douglass Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/activists/frederick-douglass

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E Television Networks

- Last Updated: July 15, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- If there is no struggle there is no progress. . . . Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.

- Find out just what any people will quietly submit to and you have the exact measure of the injustice and wrong which will be imposed on them.

- I prefer to be true to myself, even at the hazard of incurring the ridicule of others, rather than to be false, and to incur my own abhorrence.

- No man can put a chain about the ankle of his fellow man without at last finding the other end fastened about his own neck.

- People might not get all they work for in this world, but they must certainly work for all they get.

- I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong.

- Where justice is denied, where poverty is enforced, where ignorance prevails, and where any one class is made to feel that society is an organized conspiracy to oppress, rob and degrade them, neither persons nor property will be safe.

- The life of the nation is secure only while the nation is honest, truthful, and virtuous.

- [I]n all the relations of life and death, we are met by the color line. We cannot ignore it if we would, and ought not if we could.

- If I ever had any patriotism, or any capacity for the feeling, it was whipt out of me long since by the lash of the American soul-drivers.

- The ground which a colored man occupies in this country is, every inch of it, sternly disputed.

- The lesson of all the ages on this point is, that a wrong done to one man is a wrong done to all men. It may not be felt at the moment, and the evil day may be long delayed, but so sure as there is a moral government of the universe, so sure will the harvest of evil come.

- Believing, as I do firmly believe, that human nature, as a whole, contains more good than evil, I am willing to trust the whole, rather than a part, in the conduct of human affairs.

- To educate a man is to unfit him to be a slave.

- To deny education to any people is one of the greatest crimes against human nature. It is easy to deny them the means of freedom and the rightful pursuit of happiness and to defeat the very end of their being.

- There is no negro problem. The problem is whether the American people have loyalty enough, honor enough, patriotism enough, to live up to their own constitution.

- Let us have no country but a free country, liberty for all and chains for none. Let us have one law, one gospel, equal rights for all, and I am sure God's blessing will be upon us and we shall be a prosperous and glorious nation.

Abolitionists

Harriet Tubman

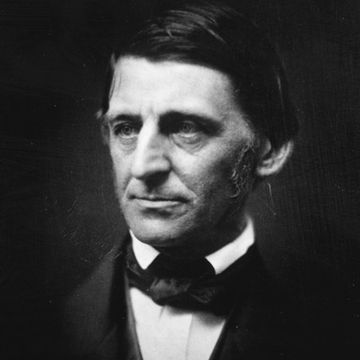

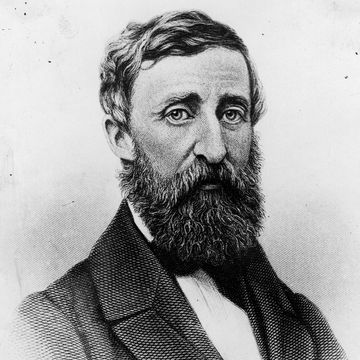

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Abraham Lincoln

Susan B. Anthony

Lucretia Mott

Harriet Beecher Stowe

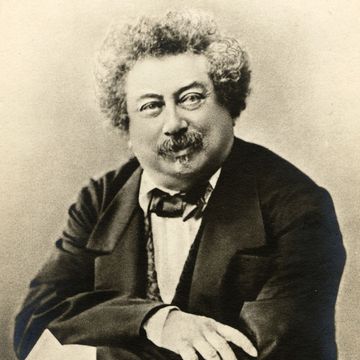

Alexandre Dumas

Henry David Thoreau

Mary Ann Shadd Cary

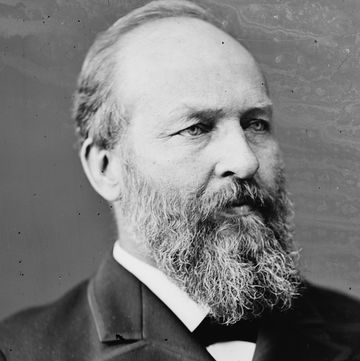

James Garfield

Jean-Jacques Dessalines

Frederick Douglass

February 1818–February 20, 1895

After escaping from bondage on September 3, 1838, Frederick Douglass became a highly-acclaimed orator and writer supporting the abolition of slavery before the Civil War and the enactment of African American rights during Reconstruction.

On July 5, 1852, during a holiday celebration sponsored by the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society, Douglass delivered what many consider to be his most famous speech, entitled “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” [ Wikimedia Commons ]

Birth and Early Life

Acclaimed abolitionist and women’s rights supporter Frederick Douglass was born into slavery in Talbot County, Maryland, near the Chesapeake Bay. His birth name was Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey. As with many slaves, Douglass did not know the exact date of his birth, but he celebrated it on February 14. Douglass was of mixed ancestry. His mother, Harriet Bailey, was an African American whose lineage may have included some Native American forebears. Douglass’ father was an unknown white man, possibly his mother’s owner.

Separated from his mother as an infant, Douglass lived the first years of his life with his maternal grandmother, Betty Bailey, on another plantation. Douglass’ mother died when the boy was about seven years old. Later, writing in his autobiography, Douglass recalled that his master refused to allow him:

to be present during her illness, at her death, or burial. She was gone long before I knew anything about it. Never having enjoyed, to any considerable extent, her soothing presence, her tender and watchful care, I received the tidings of her death with much the same emotions I should have probably felt at the death of a stranger.

About the time his mother died, Douglass became the property of Lucretia Auld, wife of Thomas Auld. The Aulds subsequently sent Douglass to Baltimore to serve Thomas’ brother Hugh Auld. When Douglass arrived in Baltimore, Hugh Auld’s wife, Sophia, began teaching him the alphabet, a clear violation of statutes against educating slaves. When Auld’s husband learned of his wife’s activities, he forbade her from continuing the lessons. Afterward, Douglass learned to read by trading scraps of food for lessons from poor white boys he met on the streets of Baltimore.

Douglass lived in Baltimore for about seven years. In March 1832, when he was fourteen years old, Douglass returned to Thomas Auld’s custody at St. Michael’s plantation in eastern Maryland. On January 1, 1833, Auld sent Douglass to toil as a field hand on the small farm of Edward Covey. Covey had a notorious reputation for breaking young slaves, and it took him only a week to inflict the first of many severe whippings to his new rented laborer. Douglass later recorded that “During the first six months, of that year, scarce a week passed without his whipping me.” The abuse went on until August when Douglass resolved to take no more and “seized Covey hard by the throat” as he attempted to administer another whipping. The two then engaged in a fiery brawl that eventually brought Covey to his knees. Douglass recalled that “The whole six months afterwards, that I spent with Mr. Covey, he never laid the weight of his finger upon me in anger.” Afterward, Douglass suggested that the reason Covey never reported him for committing the criminal act of laying his hands on a white man was that it would have tarnished his reputation as “a first-rate overseer and negro-breaker” if people learned that a fourteen-year-old boy bested him>

Douglass’ term of service to Covey ended on Christmas Day, 1833. Thomas Auld next hired out Douglas to William Freeland. Douglass found Freeland to be more lenient than Covey. While toiling on Freeland’s farm about three miles from St. Michael’s, Douglass secretly began teaching other slaves in the area to read during “Sabbath school” at “the house of a free colored man.” When Freeland did nothing to stop the meetings after learning of them, armed whites, enraged that Douglass was educating slaves, stormed into a session and permanently dispersed the congregation.

In 1835, Thomas Auld indentured Douglass to Freeland for another year. When authorities arrested Douglass for plotting an escape with two other slaves, he expected Auld to end his indenture and sell him into the Deep South. It elated Douglass to learn that Auld planned to send him back to live with his brother in Baltimore under the watch of Hugh Auld.

Upon Douglass’ return to Baltimore, Hugh Auld hired him out to William Gardner. Working as a caulker for Gardner’s shipbuilding company, Douglass earned a dollar and a half a day, all of which went to Auld. Understandably, Douglass “could see no reason why . . . at the end of each week” he should “pour the reward of (his) toil into the purse of my master.” Gradually, his resentment renewed his longing to escape to the North.

Escape from Slavery

While living in Baltimore, Douglass began a love affair with Anna Murray, a free black woman. When Douglass shared his desire to escape from bondage, the two conspired to secure his freedom. On September 3, 1838, dressed as a sailor, Douglass used funds provided by Murray to board a train under an assumed identity in Baltimore bound for Wilmington, Delaware. From Wilmington, the fugitive sailed by steamboat to Philadelphia, where he caught a train to New York. Upon his arrival in New York, Douglass continued on to the home of noted abolitionist David Ruggles, a free black man who reportedly helped over 600 African Americans escape bondage. Douglass’ uneventful journey to freedom spanned fewer than twenty-four hours.

Days after Douglass’ arrival in New York, Murray joined him. On September 15, 1838, the Reverend James Pennington, who was also a fugitive slave from Maryland, married the couple at Ruggles’ home. To avoid discovery by bounty hunters, the newlyweds assumed the surname of Johnson and heeded Ruggles’ advice and moved farther north to New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Upon his arrival in New Bedford, Nathan Johnson befriended Douglass. Douglass also changed his surname. Johnson was reading Sir Walter Scott’s Lady of the Lake at the time and suggested the name of the poem’s heroine, Ellen Douglas. From that time forward, Frederick Bailey became Frederick Douglass.

Although Douglass escaped slavery in New Bedford, he did not escape prejudice. When white caulkers refused to work beside him, Douglass had to abandon his craft and toil as a common laborer at any job he could secure for the next three years.

While living in New Bedford, Douglass began reading The Liberator , a weekly newspaper published by William Lloyd Garrison and Isaac Knapp in Boston. During its thirty-one years in publication, the weekly championed abolishing slavery and expanding women’s rights in the United States. Inspired by the paper’s message, Douglass began attending anti-slavery meetings and became active in the abolitionist movement. After rising to speak at an anti-slavery convention at Nantucket, on August 11, 1841, Douglass recalled that:

I spoke but a few moments, when I felt a degree of freedom, and said what I desired with considerable ease. From that time until now, I have been engaged in pleading the cause of my brethren . . . .

John A. Collins, the general agent for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, attended the meeting that evening. Upon hearing the former slave’s stirring speech, Collins met with Douglass and hired him as a speaker on the spot. Douglass soon began traveling throughout New England speaking before large audiences. He also delivered speeches on behalf of the American Anti-Slavery Society .

In 1843, the New England Anti-Slavery Society resolved to host 100 meetings across the North. At the urging of William Lloyd Garrison, the group hired Douglass to join its corps of speakers. The escaped slave drew large audiences, but the possibility of being apprehended by bounty hunters prevented him from providing specific details that might reveal his true identity. When detractors began challenging the veracity of Douglass’ recollections of his life in bondage, he countered by publishing the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, in 1845, the first of several autobiographical works he penned during his life. Receiving positive reviews, the book quickly became a bestseller.

Life in Europe

On August 16, 1845, following the successful debut of his book, Douglass set sail for Europe where he spent the next two years lecturing, primarily in England and Ireland. During his stay, Douglass legally escaped the clutches of slavery when British supporters purchased his freedom from Hugh Auld at a cost of 150 pounds sterling ($711.66 in American currency) on December 5, 1846.

Newspaper Publisher

When Douglass returned to Boston in April 1847, determined to publish his own abolitionist newspaper, William Lloyd Garrison disapproved. Hoping to avoid competing with Garrison in Boston, the home of Garrison’s The Liberator , Douglass moved to the progressive city of Rochester, in western New York. There, on December 3, 1847, he issued the first edition of the North Star , under the masthead “Right is of no Sex—Truth is of no Color—God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren.” The weekly publication remained in circulation until June 1851 when it merged with Gerrit Smith’s Liberty Party Paper (based in Syracuse, New York) to form Frederick Douglass’ Paper .

During the same month that Douglass published the first issue of the North Star , he also had his first meeting with the radical abolitionist John Brown in Springfield, Massachusetts. Over the course of their discussions, Brown revealed his plan to invade the South secretly with a small band of insurgents and encourage slaves to escape their bondage. Douglass did not endorse Brown’s scheme because he believed that it had little chance to succeed. Still, Douglass left the meeting convinced of the dwindling chances of ending slavery in the United States without bloodshed.

Women’s Rights Activist

Douglass did not limit his progressive views to the abolition of slavery. In July 1848, he was the only African American to attend the Seneca Falls Convention. Elizabeth Cady Stanton , Martha Coffin Wright, Mary Ann M’Clintock, Lucretia Mott , and Jane Hunt organized the event. They advertised it as “a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman.” Historians often credit the two-day gathering, as the catalyst for the women’s rights movement in the United States.

The organizers invited men to attend the convention on the second day, and roughly forty did. Many of them joined with the first day’s participants in adopting twelve resolutions endorsing specific equal rights for women. Only the ninth resolution, which stated that “it is the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise,” did not pass unanimously. When it seemed that the ninth resolution might not pass at all, Douglass delivered an impassioned speech in favor of enfranchising women. Following Douglass’ powerful address, a small majority of the delegates approved the resolution.

Abolitionist

During the 1850s, Douglass became increasingly active in the anti-slavery Liberty Party and later with the fledgling Republican Party. In 1851, he openly split with William Lloyd Garrison . The more-radical Garrison believed that the U.S. Constitution sanctioned slavery, and he publicly condemned it. Douglass, however, defended the document, arguing that its lofty rhetoric aspiring to “establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty” confirmed the “unconstitutionality of slavery.” The two friends afterward became bitter enemies.

On July 5, 1852, during a holiday celebration sponsored by the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society, Douglass delivered what many consider his most famous speech. Over 500 enrapt abolitionists packed Corinthian Hall and listened to Douglass pose the question, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” He praised the vision of the Founding Fathers for a nation based upon “justice, liberty and humanity.” However, he also noted that “The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me.” Finally, Douglass declared that Independence Day to the slave is:

a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.

Predictably, after publication Douglass’ provocative words kindled mixed but strong reactions, ranging from anger to empathy. Despite the discord they may have evoked, however, his stinging, yet accurate, observations have withstood the test of time. They remain a powerful reminder that the pursuit of “liberty and justice for all” is still a work in progress.

John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry

As the specter of slavery further divided the United States following the Compromise of 1850 and the Dred Scott decision in 1857, Douglass began to accept the inevitability of impending bloodshed. During the latter half of the decade, Douglass met with John Brown, spoke on his behalf, and solicited funds for the zealous abolitionist’s militant exploits to end slavery. When the two men secretly met at a stone quarry near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, on August 20, 1859, to discuss Brown’s plan to take up arms against the U.S. government and attack the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry , Virginia, Douglass disapproved of the scheme and refused to get involved.

When Brown followed through with his plot on October 16, 1859, Douglass was addressing a crowd in Philadelphia. Upon learning of Brown’s raid and subsequent arrest, Douglass quickly made his way home to Rochester and then fled to Canada for fear of being falsely implicated in the conspiracy. His concerns were not unfounded. On November 13, 1859, Virginia Governor Richard Wise requested President James Buchanan ‘s help in apprehending Douglass who officials charged with “murder, robbery, and inciting servile insurrection in the State of Virginia.” On November 12, 1859, Douglass left Canada for the distant shores of England where he remained for six months, far from the reach of southern kidnappers.

In 1860, Douglass returned to the United States, passing through Canada to avoid detection. Not surprisingly, he supported President Abraham Lincoln ‘s call to arms after the Southern attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. However, when Lincoln proclaimed his goals were to quell the Southern insurrection and preserve the Union, he disappointed Douglass who viewed the ensuing conflict as a struggle to end slavery.

Despite his frustration, Douglass supported the war, especially after Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. Two months later, on February 24, Douglass signed on as an agent for the government to recruit black soldiers for the volunteer army. Douglass was largely responsible for the successful recruitment of the Massachusetts 54th and 55th regiments, the former of which included his sons Lewis and Charles. As the war progressed, Douglass became one of Lincoln’s trusted advisors, and he endorsed the president’s reelection in 1864.

Reconstruction

Following the Civil War, Douglass actively crusaded for the enactment of the 13th , 14th , and 15th amendments to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery, conferred citizenship on African Americans, and granted black Americans the right to vote. Douglass’ support of the 14th and 15th amendments led to a rift with leading members of the American Equal Rights Association, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony , because the proposed reforms granted voting rights to African American men, but did not enfranchise women. Douglass had been a vocal supporter of women’s rights for two decades, but he feared that linking the causes of black suffrage with female suffrage could doom the attainment either.

Return to Newspaper Publishing

Douglass had retired from journalism in 1863 when he ceased publication of Douglass’ Monthly , the successor of The North Star and Frederick Douglass’ Papers. In January 1870, Douglas re-entered the profession when he joined the staff of the New National Era as a corresponding editor. In December, he purchased the weekly publication and became editor-in-chief. Published until 1874, the newspaper provided a voice for black perspectives on national and local events in the Washington, DC. area.

During his stint as owner-editor of the New National Era , Douglass achieved a measure of political fame in 1872 when the Equal Rights Party nominated him as the vice-presidential running-mate of their U.S. presidential candidate Victoria Claflin Woodhull. Douglass did not seek the position, nor, in fact, was he aware that he had become the first African American nominated for Vice-President of the United States until after the party’s delegates selected him. Apparently unimpressed, Douglass did not acknowledge the nomination, and he actively campaigned for President Ulysses S. Grant ‘s re-election.

Post-Civil War Private Life

Also in 1872, on a more somber note, Douglass’ home in Rochester burned to ruins on June 2. Officials suspected arson but could never prove it. Following the fire, Douglass moved to the Washington, DC. area where he lived for the rest of his life.

In March 1874, trustees of the Freedmen’s Savings and Trust Company (also known as Freedmen’s Bank) appointed Douglass as president of the institution. Incorporated by an act of Congress on March 3, 1865, the privately chartered bank’s purpose was to assist newly emancipated African-Americans deal with their personal financial matters. During its short existence, the bank suffered from a series of fraudulent financial decisions by its managers, which imperiled the savings of thousands of freedmen. The Panic of 1873 , which triggered a worldwide economic depression, left the bank nearly in ruins.

Desperate to forestall a run against the bank’s assets, the institution’s trustees persuaded Douglass to assume oversight. Hoping to restore confidence among depositors, Douglass selflessly deposited thousands of dollars of his own money with the troubled institution. Unfortunately, neither Douglass’ personal sacrifice, nor his name and leadership were enough to avert disaster. On June 29, 1874, the Freedmen’s Bank collapsed, financially ruining tens of thousands of African Americans who had entrusted their savings to it.

Shortly after Rutherford B. Hayes took the oath of office as President of the United States on March 4, 1877, he nominated Douglass for the position of United States Marshal for the District of Columbia. When the U.S. Senate approved the nomination on March 18, Douglass became the first African American confirmed for a presidential appointment in U.S. history. Douglass held the office throughout the four years of Hayes’ presidency.

Six months after his confirmation, Douglass purchased an estate of nearly ten acres overlooking the Anacostia River, which he and his wife, Anna, named Cedar Hill. A year later he bought an adjacent tract of land that expanded the area of his holdings to over ten acres. The National Park Service now preserves the home at 1411 W Street SE, Washington, D.C., as the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

After President Hayes left office, his successor James A. Garfield installed Douglass as the Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia in 1881. During the same year, Douglass published his third autobiography, entitled Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. Sales of the book and a revised edition, published the following year, were disappointing.

Overshadowing the disappointment of his books’ sales, Douglass suffered a much larger personal tragedy in 1882 when his wife died unexpectedly of a stroke on August 4. Married for nearly forty-four years, the couple raised five children.

Two years after Anna’s death, Douglass married his former secretary and notable feminist, Helen Pitts, on January 24, 1884. Because Helen was white and nearly twenty years younger than Douglass, many people (including his family) did not approve of the marriage.

On January 5, 1886, Douglass resigned from his position as Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia and embarked on an extended tour of Europe, visiting England, Ireland, France, Switzerland, Italy, Egypt, and Greece. After Douglass returned home in 1887, President Benjamin Harrison appointed him as Minister Resident and Consul General to Haiti on July 1, 1889. Two months later, Harrison also named Douglass as Chargé d’affaires for Santo Domingo and Minister to Haiti. 1891, Douglass resigned from his appointments following a dispute with the state department. In 1893, Haiti named Douglass a co-commissioner of its pavilion at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Death and Burial

On February 20, 1895, Douglass attended a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C. During that meeting, he received a standing ovation after being welcomed to the speaker’s platform. When Douglass returned home that evening, he suffered a massive heart attack and died at age seventy-seven. Following funeral services at Cedar Hill, on February 25, thousands of mourners viewed Douglass’ body as it lay in state at Metropolitan African Methodist Church in Washington. Douglass’ remains were transported to Rochester where they were interred at Mount Hope Cemetery after additional memorial services.

- Written by Harry Searles

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to this park navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to this park information section

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Alerts in effect, frederick douglass.

Last updated: March 2, 2024

Park footer

Contact info, mailing address:.

1411 W Street SE Washington, DC 20020

771-208-1499 This phone number is to the ranger offices at the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

Stay Connected

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Why Frederick Douglass Matters

By: Yohuru Williams

Updated: September 28, 2023 | Original: February 10, 2018

Frederick Douglass sits in the pantheon of Black history figures. Born into slavery, he made a daring escape North, wrote best-selling autobiographies and went on to become one of the nation’s most powerful voices against human bondage. He stands as the most influential civil and human rights advocate of the 19th century.

Perhaps his greatest legacy? He never shied away from hard truths.

Because even as he wowed 19th-century audiences in the U.S. and England with his soaring eloquence and patrician demeanor, even as he riveted readers with his published autobiographies, Douglass kept them focused on the horrors he and millions of others endured as enslaved Americans: the relentless indignities, the physical violence, the families ripped apart. And he blasted the hypocrisy of a slave-holding nation touting liberty and justice for all.

He wanted to rouse the nation's conscience—and expose its hypocrisy

Douglass’s voluminous writings and speeches reveal a man who believed fiercely in the ideals on which America was founded, but understood—with the scars to prove it—that democracy would never be a destination of comfort and repose, but a journey of ongoing self-criticism and struggle. He knew it when he lobbied relentlessly to abolish slavery . And he knew it after Emancipation, when he continued to battle for equal rights under the law .

Indeed, Douglass knew, as he argued so ardently in his famed 1852 July Fourth speech , that for democracy to thrive, the nation’s conscience must be roused, its propriety startled and its hypocrisy exposed. Not once, but continually and for the good of the nation, he argued, we must bring the “thunder.”

Douglass’s extraordinary life and legacy can be understood best through his autobiographies and his countless articles and speeches. But they weren't his only activities. He also published an abolitionist newspaper for 16 years...supported the Underground Railroad by which enslaved people escaped north...became the first African American to receive a vote for President of the United States during roll call at the 1888 Republican National Convention...and even was known to play America’s national anthem on the violin.

Underpinning it all was his relentless process of self-education—a theme that runs throughout Douglass’s life story.

Education, abuse and escape

Born in Maryland in 1818, Douglass, like many enslaved children, was separated from his mother at birth; he resided with his loving maternal grandmother until he turned seven.

At the age of eight, he became a servant in the home of Hugh Auld in Baltimore. In defiance of the codes that explicitly forbade teaching enslaved people how to read, Mrs. Auld taught Douglass the alphabet, unlocking the gateway to education—which he would extol the rest of his life. Over time Douglass surreptitiously continued to teach himself to read and write, all the while strengthening his resolve to escape the confines of slavery. He defied the law in not only learning to read and write, but in teaching other enslaved people to do so. As he observed: “Some know the value of education by having it. I know its value by not having it.”

In the early 1830s, Douglass was shipped to the plantation of Hugh’s brother Thomas. In an effort to break his spirit, Thomas loaned Douglass to Edward Covey, a sadistic local slave master with a reputation for cruelty. Covey mercilessly beat and abused the teenager until one day Douglass decided to fight back, knocking Covey to the ground. Covey, tempered, never mentioned the encounter, but he also never laid hands on him again.

As for Douglass, he called the battle with Covey “the turning point” in his life as an enslaved person: “It rekindled the few expiring embers of freedom, and revived within me my own sense of manhood. It recalled the departed self-confidence, and inspired me again with a determination to be free.”

In September of 1838 Douglass, disguised as a sailor and with borrowed free papers, managed to board a train to Havre de Grace, Maryland. He continued on to New York and ultimately, New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he settled, a free man. He married Anna Murray , a free woman of color who he had met and fallen in love with while in bondage in Baltimore. The couple had five children. The Douglasses made a commitment to eradicating the evil of slavery.

The authoritative voice of Abolition

After speaking at an anti-slavery meeting in 1841, Douglass met William Lloyd Garrison , one of the leading proponents calling for an immediate end to slavery. The two became friends and with Garrison’s support, Douglass became one of the most sought-after speakers on the abolitionist circuit, not only for his searing testimony but his powerful oratory. In time, he lent his voice to the emerging women’s-rights movement as well. He once reflected: “I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong.”

In 1845, Douglass committed his story to print, publishing the first of three autobiographies , Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave , with the support of Garrison and other abolitionists. The book gained international acclaim, confounding critics who argued that such fluid writing and penetrating thought could not be the product of a Black mind. Nevertheless, the Narrative catapulted Douglass to success outside the ranks of reformers, stoking fears that his celebrity might result in attempts by Auld to reclaim the man he had enslaved. To avoid this fate, Douglass traveled to England, where he remained for two years until a group of supporters there successfully negotiated payment for his freedom.

Back in the United States, Douglass navigated the tumultuous decade of the 1850s, steering a course between extremists like John Brown , who believed the only way to abolish slavery was through armed insurrection, and old friends like Garrison. Douglass published his own newspaper , The North Star . On the masthead, he inserted the motto “Right is of no sex—Truth is of no color—God is the Father of us all, and we are brethren,” incorporating both Douglass’s anti-slavery and pro-women’s rights views.

On the eve of the Civil War , Douglass used his fame and influence to petition the Lincoln Administration to press for emancipation . As he remarked: “The thing worse than the rebellion is the thing that causes the rebellion.” He further demanded that the Union allow Black men to enlist and aided the war effort by promoting recruitment .

Without struggle, he learned, there is no progress

Despite the hope engendered by the passage of the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery following the war, Douglass remained cautious, observing: “Verily, the work does not end with the abolition of slavery, but only begins.” Over the course of the next few years, he remained a strong voice advocating for the passage of additional legislation to ensure absolute equality for Black people. By the end of the decade, however, he was also painfully aware of the mounting efforts to suspend Reconstruction and return Black people to a state of quasi-slavery—measures he continued to fight. His experience had taught him: “Without a struggle, there can be no progress.”

Douglass died on February 20, 1895. While his life mapped the triumphant journey from slavery to freedom, the seeds of division had already been sown on the eve of his death. Three years earlier, Homer Plessy challenged Louisiana’s law that required “all railway companies [to] provide equal but separate accommodations for the white, and colored races,” leading to the landmark 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision upholding racial segregation. In spite of the failure of Reconstruction and the assault on Black equality, Douglass had still remained hopeful of a different outcome.

Of all the inspiring things to be recovered in Douglass life, his work in pursuit of social justice remains the most compelling. An uncompromising critic of American hypocrisy rather than American democracy, his critique was anchored much more in what could be.

Far from “slandering Americans” as he called it, Douglass appealed to them to remember the oppression that led to revolution, the desire for liberty that fueled its leaders and the vigilance necessary to maintain freedom. He warned against the denial of the most basic of human rights and the betrayal of revolutionary values in thoughts and actions.

That, today, is perhaps the most important lesson to be gleaned from Douglass’s life. We would do well to acknowledge his daring escape from slavery, powerful oratory, leadership on civil and women’s rights. But we shouldn't separate that from his ultimate message, which compelled us to be better—and more vocal—in the messy, ongoing process of pursuing social justice and perfecting our democracy. That, he believed, is what would make America great.

Yohuru Williams, an American academic, author and activist, serves as Distinguished University Chair, Professor and Founding Director of the Racial Justice Initiative at the University of St. Thomas.

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (c. 1817–1895) is a central figure in U.S. and African American history. [ 1 ] He was born into slavery circa 1817; his mother was an enslaved black woman, while his father was reputed to be his white master. Douglass escaped from slavery in 1838 and rose to become a principal leader and spokesperson for the U.S. Abolition movement. [ 2 ] He would eventually develop into a towering figure for the U.S. Civil Rights Movement and American politics, and his legacy would be claimed by a diverse span of groups, from liberals and integrationists to conservatives to nationalists, within and without black America.

He wrote three autobiographies, each one expanding on the details of his life. The first was Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written By Himself (1845); the second was My Bondage and My Freedom (1855); and the third was Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881/1893). [ 3 ] They are now foremost examples of the American slave narrative. In addition to being autobiographical, they are also, as is standard, explicitly works of political and social criticism and moral suasion; they aim at the hearts and minds of the readers. Their greater purpose was to attack slavery, contribute to its abolition in the United States, and argue for black Americans’ full inclusion into the nation.

Shortly after escaping from slavery, Douglass began operating as a spokesperson, giving numerous speeches about his life and experiences for William Lloyd Garrison’s American Anti-Slavery Society. To spread his story and assist the abolitionist cause and counter early charges that someone so eloquent as he could not have been a slave, Douglass wrote and published his first autobiography, The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written By Himself . It brought Douglass fame throughout the United States and the United Kingdom, and it provided the funds to purchase his freedom. Douglass eventually broke with Garrison and founded his first paper, the North Star . He served as its chief editor and authored a considerable body of letters, editorials, and speeches from then on. These writings are collected in Philip Foner’s multi-volume, The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass (1950–1975), and John W. Blassingame and John R. McKivigan’s multi-volume, The Frederick Douglass Papers (1979–1992). [ 4 ]

Douglass’s advocacy in the abolition movement and his continued work after the U.S. Civil War, and his writings and participation in national discussions about the nature and future of the American Republic, made him a significant figure in American history and the history of American political ideas. His writings, speeches, and his national and international work have inspired many lines of discussion in debate within the fields of American and African American history and political science. Moreover, political thinkers representing different ideological positions, including liberals, libertarians, and economic and social conservatives, claim his legacy.

But what does anything about this have to do with philosophy? The connections between Douglass’s legacy and social and political philosophy are numerous and ongoing. His ideas about humanity, liberty, equality, property, democracy, and individual and social development addressed immediately pressing concerns, but they were also theoretical—he self-consciously addressed their moral and theological foundations. Furthermore, his work is connected to academic philosophy through the uptake of his political and social legacy and writings by later African American philosophers such as W.E.B. Du Bois (1868–1963) and Alain Locke (1884–1954). [ 5 ] In contemporary philosophy, Douglass’s work is usually taken up within American philosophy, Africana philosophy, black political philosophy, and moral, social, and political philosophy more broadly. In particular, the discussions that involve Douglass focus on his views concerning some of the topics reviewed in this entry: slavery and racial segregation; natural law and the U.S. constitution; liberalism and republicanism; violence, self-respect, and dignity; racial integration versus emigration or separation; cultural assimilation and racial amalgamation; democratic action; and women’s suffrage. Additionally, just as there is a rich discussion about Douglass in philosophy and political theory, there is a related discussion about Douglass’s rhetoric, particularly the structure and meaning of his political rhetoric as displayed in his speeches, autobiographies, and other writings. [ 6 ]

For students and teachers first learning about Douglass, there is no better place to start than his first autobiography, The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845). Next, read some of his speeches and writings referenced in this entry, especially “What To the Slave Is The Fourth of July?” (1852 [SFD: 55–92]). Then dive into the historical, political, literary, and philosophical literature about Douglass.

2. Natural Law

3. on liberty, 4. the u.s. constitution, 5. violence and self-defense, 6. respect and dignity, 7. universal human brotherhood, 8. amalgamation and assimilation, 9. integration versus emigration, 10. leadership, 11. women’s suffrage, 12. at the dawn of jim crow, a.1 collections and abbreviations, a.2 works by douglass, b. secondary literature, other internet resources, related entries.

In his narratives, speeches, and articles leading up to the U.S. Civil War, Douglass vigorously argued against slavery. He sought to demonstrate that it was cruel, unnatural, ungodly, immoral, and unjust. Douglass laid out his arguments, first in his speeches while allied with William Lloyd Garrison’s American Anti-Slavery Society, and then in his first autobiography, the Narrative . As the U.S. Civil War drew closer, he expanded his arguments in many speeches, editorials, and his second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom. [ 7 ]

His definition of slavery identified its immorality and injustice by pinpointing its core wrong in the brutalization and the literal commodification of another human being and the stripping of them of their natural rights:

Slavery in the United States is the granting of that power by which on man exercises and enforces a right of property in the body and soul of another. The condition of a slave is simply that of the brute beast . He is a piece of property—a marketable commodity in the language of the law, to be bought and sold at the will and caprice of the master who claims him to be his property; he is spoken of, thought of, and treated as property. His own good, his conscience, his intellect, his affections are all set aside by the master. The will and the wishes of the master are the law of the slave. He is as much a piece of property as a horse. (1846 [SFD: 23]; my emphasis) [ 8 ]

In his own words, he worked to pour out “scorching irony” to expose the evil of slavery (1852 [SFD: 71]). His rebellion against slavery began, as he recounted, while he was enslaved. In his narratives, the depiction of his early recognition and general recognition among blacks and some whites of the injustice, unnaturalness, and cruelty of slavery was a significant element of his argument. It marks his first argument against slavery. Some of the apologists for slavery claimed that blacks were beasts, subhuman, or at least a degenerated form of the human species, drawing on a racial ideology that went back to at least the fifteenth century and that was common in the British American Colonies and then the United States. [ 9 ] Thomas Jefferson, for example, infamously intimates this racist view in his Notes on the State of Virginia (1785: Query 14). Against such racist ideology, Douglass argued that blacks were human, rational, and capable of the full range of human emotions and sensitivity. He mocked slavery’s apologists for their hypocrisies and contradictions when they claimed otherwise. In “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro”, he is derisive of the idea that he would even need to argue this point (1852 [SFD: 55–92]). [ 10 ]

Against the claim that blacks were beasts, he argued that instead, slavery had brutalized them. He pointed to the obviousness of blacks’ humanity and mocked the hypocrisy of slavery’s apologists. He rhetorically asked: Why should there be special laws prohibiting the free actions of blacks, such as rebelling against slave masters, or any other white person, if slaves were merely bestial and incapable of independent, responsible behavior? Indeed, why had slave masters encouraged their slaves’ Christianization and then forbade their religious gatherings? Along with this hypocrisy, American slaveholders feared and banned the education of blacks while demanding and profiting from their learning and development in the skilled trades. Thus, Douglass argued the accusation that blacks were beasts was predicated on the guilty knowledge that they were humans. Additionally, it subverted not only the natural goodness of blacks by brutalizing them, but it also did so to white slaveholders and those otherwise innocent whites affected by this wicked institution. Slavery, Douglass pointed out, consistent with Jefferson’s anxieties in Query 18 of the Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), was a poison in the body of the republic.

Second, since blacks were humans, Douglass argued they were entitled to the natural rights that natural law mandated ( §2 and §3 ) and that the United States recognized in the Declaration of Independence and Constitution ( §4 ). Slavery subverted the natural rights of blacks by subjugating and brutalizing them: taking men and turning them, against God’s will and nature, into beasts. Third, as an affront to natural law, slavery contradicted God’s laws and corresponding moral duties to others. As a witness and participant of the second Great Awakening, he took the politicized rhetoric of Christian redemption—personal and social liberation from sin—seriously. Douglass viewed redemption as intrinsically wrapped up with freedom from slavery and national liberation like other abolitionists. Fourth, he argued that slavery was inconsistent with the idea of America, with its national narrative and highest ideals, and not just with its founding documents. Fifth, drawing on theories of providential historical development (echoing common American views of manifest destiny), he argued that slavery was inconsistent with moral, political, economic, and social progress. Insofar as it propagated and protected slave power, America was on the wrong side of history on the question of slavery.

The apologists of slavery drew on the same ideological vein of historical progress to offer the defense that slavery was a benevolent and paternal system for the mutual benefit of whites and blacks. Douglass countered that calumny by drawing on his experiences, and the experiences of other enslaved black Americans, that American slavery was in no way benevolent. It brutalized black people. Slavery subjected them to debilitating, murderous violence, sexual violence and exploitation, split up families, denied them education, exploited their labor, and denied their natural property rights. Slavery, as Douglass’s relentlessly argued, was a deep and enduring injustice and evil. Enslaved black people were not happy slaves benefiting from the largess of kind, gentile white masters. Neither were they lacking in agency, self-esteem, self-respect, or a sense of dignity. They were moral beings, fully aware of the rights and capabilities they were unjustly deprived of. As Douglass proclaimed to the nation and world, black Americans wanted freedom, independence, the recognition of their full personhood, moral equality, and their rights as U.S. citizens (McGary and Lawson, 1992). [ 11 ]

The ideas that Douglass drew on in his arguments against slavery originate from natural law theory and Christian theology. Douglass was an Enlightenment thinker, a nineteenth-century modernist, and a Protestant, so natural law in his view was a combination of the prescriptions of reason and revelation evident in the historical and civilizational progress of humanity. One of his clearest articulations of this combined view is from a 1853 speech, “The Present Condition And Future Prospects of the Negro People” (1853b [FDSW: 250–259]), where condemns declares,

Slavery has no means within itself of perpetuation or permanence. It is a huge lie. It is of the Devil, and it will go to its place. It is against nature, against progress, against improvement, and against the Government of God. It cannot stand. It has an enemy in every bar of railroad iron, in every electric wire, in every improvement in navigation, in the growing intercourse of nations, in cheap postage, in the relaxation of tariffs, in common schools, in the progress of education, the spread of knowledge, in the steam engine, and in the World’s Fair…and in everything that will be exhibited there. (1853b [FDSW: 259]) [ 12 ]

The sources for his driving belief in natural law and its moral implications were many: the founding documents of the United States; popular intellectuals, such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and his colleagues and acquaintances in the American Abolition movement; the allies he encountered abroad; and his appreciation of George Combe’s The Constitution of Man , from 1834 (Van Wyhe 2004). However, given the numerous religious references in his speeches and writings, a primary source for his employment of the idea of natural law was his adaptation of the American Protestantism of the Second Great Awakening, with its democratic and republican values and generally independent spirit. All of this is on prominent display at the conclusion of his famous speech, “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro”:

The arm of the Lord is not shortened“, and the doom of slavery is certain. I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope. While drawing encouragement from the Declaration of Independence, the great principles it contains, and the genius of American Institutions, my spirit is also cheered by the obvious tendencies of the age. (1852 [SFD: 90])

Relying on the deus ex machina was not enough for Douglass. His vision of natural rights involved action; his image of civic republicanism emphasized the need for active participation to claim or earn one’s rights and status as a citizen (Davis 1971; Pettit 1997; Myers 2008; Gooding-Williams 2009). As Douglass scathingly pointed out, the slave-holding states resisted the abolition of slavery, and many Americans were apathetic about its cruel injustices—humans resist providential justice. Therefore, he argued, the end of slavery required agitation, protest, and, if needed, military intervention.

Douglass longed for God to cast his thunderbolts of judgment at American slave power, but he knew that human action was needed to abolish slavery in America (Blight 1989: 26–58). His view of, if you will, enacted providence is on full display at the end of his famous Fourth of July speech of 1852, where he cited Psalm 68:31 and paired the idea of God’s fiat with the image of Africa and Asia rising:

The far off and almost fabulous Pacific rolls in grandeur at our feet. The Celestial Empire, the mystery of ages, is being solved. The fiat of the Almighty, ”Let there be Light“, has not yet spent its force. No abuse, no outrage whether in taste, sport or avarice, can now hide itself from the all-pervading light. The iron shoe, and crippled foot of China must be seen, in contrast with nature. Africa must rise and put on her yet unwoven garment. ”Ethiopia shall stretch out her hand unto God“. (1852 [SFD: 91]) [ 13 ]

There are many possible concerns about Douglass’s view of natural law, manifest destiny, and providence, which we can discern from a careful reading of the passage above; they involve a belief in historical teleological development and the human costs of that assumption. These costs include affirming nineteenth-century conceptions of civilizational backwardness of non-European societies or peoples. Thus, he is relatively silent about the United States’ destructive actions against indigenous peoples.

This aspect of Douglass’s views led Wilson Jeremiah Moses to characterize him and other early black political figures as ”Moses“ figures: exodus leaders, recipients of natural law for a chosen people. The chosen people, in this case, are African Americans in their travail for freedom, as well as the American Republic as a whole. Douglass—twinned eternally with Abraham Lincoln—is a lawgiver in the American civil religion (Moses 1978). This monumental, world-historical vita aside, Douglass’s faith in progress, although tested to its breaking point, resulted in his putting too much belief in the inevitability of progress. Nonetheless, his faith had a moral, social, and political purpose. He had no time for political pessimism, which is either a narcotizing sentiment for those who have surrendered to despair or a performative luxury whose decadence only those secure in their liberty can afford.

Instead of surrendering to despair, he joined the abolition movement after escaping slavery. And for that grand purpose, natural law and rights were ideas he believed in and used to significant effect. Thus, in his writings, his writings he repeatedly makes clear and direct references to concepts that flow from liberalism: liberty; moral and social equality; individuality; property rights, self-defense, and speech; the moral and instrumental value of labor; democracy; and composite (what we would call multiethnic or multiracial) nationality. This is why he is rightly associated with liberalism (Myers 2008; Buccola 2012). The relation between Douglass’s works and those ideas is apparent; however, three merit highlighting because they are not typically emphasized in the theoretical literature about Douglass: free speech, property, and composite nationality.

Douglass’s life after abolition speaks to the importance of the freedoms of speech, thought, and opinion and the great value he placed on them. From his efforts to learn how to read and write to his desire to start his own newspaper, his attitude and actions aggressively asserted the indivisible links between equal liberty and the right to think and speak one’s mind. Like the name of his first newspaper, this value was his North Star . So, on 9 December 1860, in response to the violent disruption of a meeting he was participating in, Douglass directly addressed the matter in his speech, ”A Plea for Freedom of Speech in Boston“, wherein he delivered a classic liberal defense of it that still resonates:

There can be no right where any man however, lifted up or humble, however young or however old, is overawed by force, and compelled to suppress his honest sentiments. (1860c [FDP1 v.3: 423])

The silencing of speech squashes thought, opinion, and discussion, and doing so, as Douglass pointed out—consistent with other philosophers on liberty—commits a ”double wrong. It violates the right of the hearer as well as those of the speaker (Ibid.). [ 14 ]

On property, Douglass argues, as expected, against human bondage. That, however, was not the only thing he had to say about it. The positive right to property, the right of black Americans to their bodies, the labor of their bodies, and the wealth generated from their productivity are ideas that feature prominently throughout the narratives. Douglass wrote movingly about the productivity of his labor, the exploitation of it by his enslavers and those in their employ, the theft of his rightfully earned wages, and the anger of some white laborers who resented having to work and compete with free black workers. The right to self-ownership, labor, and property were not just mere things denied to him—they were expressions, products, and symbols of his liberty and liberty in general. In the Narrative , for example, on the theft of his wages by Hugh Auld, his master’s brother, Douglass wrote,

I was now getting, as I have said, one dollar and fifty cents per day. I contracted for it; I earned it; it was paid to me; it was rightfully my own; yet, upon each returning Saturday night, I was compelled to deliver every cent of that money to Master Hugh. And why? Not because he earned it,—not because he had any hand in earning it,—not because I owed it to him, nor because he possessed the slightest shadow of a right to it; but solely because he had the power to compel me to give it up. The right of the grim-visaged pirate upon the high seas is exactly the same. (FDAB: 84)

From the Civil War through Reconstruction and its betrayal, Douglass continued to see the right to property as a necessary part of genuine emancipation. He wrote and frequently spoke about the ennobling, moral, and economic power of labor, private property, and individual productivity in articles before emancipation like, “What Shall be Done with the Slave if Emancipated” from 1862 (FDSW: 470–473) to speeches like “Self-Made Men” from 1893 (SFD: 414–453).

On composite nationality, or what we would call multiethnic democracy, Douglass’s “Our Composite Nationality” from 1869a (SFD: 278–303) is a ringing endorsement of a robust vision of civic belonging and national identification. It is an outlook that reflects his support for organic processes of assimilation and amalgamation and social reform. More on that below ( §§6–8 and §12 ).

Just as he drew on liberal ideas, he repeatedly invoked ideas of American civic republicanism and advocated for democratic reform, action, and, eventually, universal suffrage ( §11 ). This democratic advocacy has led some philosophers to view Douglass as a civic republican as much as he was a liberal (Gooding-Williams 2009). The evidence for that connection naturally arises from the wide variety of his democratic associational activity. It is modeled in his narratives, particularly in My Bondage and My Freedom , in its depictions of social organization, action, solidarity, friendship, and affection among black men and women (FDAB: 305–306).

Whether we understand Douglass as a liberal or civic republican (or even as a type of black nationalist or black radical liberal), the values and ideas he drew on were the foundation of his fierce denunciations of and active resistance to American slavery and his interpretation of the U.S. Constitution.

In 1851 Douglass broke from William Lloyd Garrison’s position that the U.S. Constitution was a pro-slavery document and that the free states should peacefully secede from the Union. In a letter to Gerrit Smith, he reported that he was “sick and tired of arguing on the slaveholder’s side…” (21 January 1851 [FDSW: 171–173]). So, he decided to break with Garrison and side with Smith and the Liberty party’s position that the United States’ founding documents were anti-slavery (Blight 1989: 26–58; Root 2020).

In his famous speech on the topic, “What To the Slave Is The Fourth of July?” (1852 [SFD: 55–92]), he detailed his signature positions on the U.S. Constitution: that slavery is contrary to natural law, that blacks are self-evidently human and entitled to natural rights, and that slavery is inconsistent with the Constitution, American Republicanism, and Christian doctrine, and that it should be forcefully—violently—resisted. [ 15 ] A principal example of this shift is the changes in his second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855, FDAB); particularly relevant is the extra and weighty meaning he imparts to the famous scene of his fight with the slave breaker Covey ( §5 ).

Douglass acknowledged that initially, he accepted the view, promoted by William Lloyd Garrison and allies aligned with him, that the framers intended to allow slavery to continue in the slave states and that the Constitution was thereby consistent with the institution of slavery. However, the Garrisonian view of the Constitution resulted in passivity in the face of the Slave-holding states’ threat of succession. That position did not sit well with Douglass because he wanted a more aggressive stance and strategy for abolishing slavery and the emancipation of the enslaved, including in the southern slave-holding states. Plus, he became convinced of the natural law reading of the U.S. Constitution that foregrounded the values outlined in the U.S. Declaration of Independence. What convinced him were the arguments of Gerrit Smith, Lysander Spooner, William Goddell, and Samuel E. Sewall that the Constitution was an anti-slavery document and that the founders were at cross-purposes on the question of slavery. Douglass argued that the general ideas of America’s founding documents supported an interpretation of the U.S. Constitution as an evolving document in tune with the development of civilization. Thus, he intoned the call, “let there be light”, to capture his hope for abolition, emancipation, and universal political and social progress (1852 [SFD: 91]).

Douglass’s view of the Constitution is one of the reasons why he is associated with the assimilationist (or what is better understood as the integrationist tradition) tradition in African American political thought. It sets him up for the criticism that he did not squarely recognize the racialized character of the nation, how deeply embedded race and racism were in its institutions, and that it was in many respects a racial state. [ 16 ] Douglass, however, was not blithe to the nation’s sins—he repeatedly and forcefully condemned them through the end of his life ( §12 ). His reading of the Constitution was reasonable, grounded in his affirmation of natural law theory, and it was an essential part of the history of abolition (Sinha 2016; Delbanco 2018).

Douglass remained active in the years leading up to the U.S. Civil War. He advocated for the abolition of slavery, worked against the expansion of slavery into new U.S. territories, and vigorously protested the Dred Scott decision and related laws that protected the property rights of slaveholders over slaves who escaped to the Free States in the North.

He was a member of the Liberty party, was involved in other political parties, including the Radical and Free Soil parties, and eventually became involved with the Republican party—all for the sake of abolition and the support of equal citizenship for all Americans (Blight 1989 and 2018). Douglass even met the militant abolitionist, John Brown. Although Douglass declined to join Brown’s militia—he sensed the deadly potential of Brown’s zealotry and the likelihood of its failure—he defended Brown’s ideals and denounced claims that Brown was merely mad. Although Douglass distanced himself from Brown’s plans and destructive actions, he appropriated Brown as a symbol of righteous violence against the national sin of slavery and used the raid at Harper’s Ferry to criticize President Lincoln’s reluctance to support abolitionism (1859 [FDSW: 372–376]; 1860b [FDSW: 417–421]; Myers 2008: 63–73; Blight 1989: 95–100).

Douglass’s rejection of pacifism and his support for Federal military intervention to end slavery was a significant turning point in his thought about natural law, divine providence and manifest destiny, and constitutional interpretation. Douglass’s defense of jus ad Bellum greatly affected his contemporaries and the resulting debate on slavery, struggle, and self-respect. The modern debate over violence and self-respect in African American philosophy, critical race theory, and black political theory begins with Douglass’s narratives, particularly his famous fight with the “Negro breaker”, Edward Covey. This incident plays a significant role in all of Douglass’s narratives: Covey represents the brutalizing institution of American slavery, and Douglass’s fight and victory represent the assertion of manhood, self-respect, dignity, and freedom. However, Douglass’s time with Covey and the suffering he endured by Covey’s hand is given a lengthier description in My Bondage and My Freedom than in the Narrative . In the former, the depiction of the fight explicitly draws parallels between Douglass’s battle with Covey and the struggles of black Americans against slavery and racial degradation.

Additionally, his fight has explicit national political connotations (Gooding-Williams 2009; Myers 2008). The scene’s depiction in each autobiography is powerful and indicates its narrative brilliance (literary, rhetorical, and philosophical), so it deserves to be quoted at length. In the Narrative (1845), Douglass wrote:

The battle with Mr. Covey was the turning-point in my career as a slave. It rekindled the few expiring embers of freedom, and revived within me a sense of my own manhood. It recalled the departed self-confidence, and inspired me again with a determination to be free. The gratification afforded by the triumph was a full compensation for whatever else might follow, even death itself. He only can understand the deep satisfaction which I experienced, who has himself repelled by force the bloody arm of slavery. I felt as I never felt before. It was a glorious resurrection, from the tomb of slavery, to the heaven of freedom. My long-crushed spirit rose, cowardice departed, bold defiance took its place; and I now resolved that, however long I might remain a slave in form, the day had passed forever when I could be a slave in fact. I did not hesitate to let it be known of me, that the white man who expected to succeed in whipping, must also succeed in killing me. (FDAB: 65)

In My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), he gives the following expanded interpretation:

Well, my dear reader, this battle with Mr. Covey,—undignified as it was, and as I fear my narration of it is—was the turning point in my “life as a slave”. It rekindled in my breast the smouldering embers of liberty; it brought up my Baltimore dreams, and revived a sense of my own manhood. I was a changed being after that fight. I was nothing before; I WAS A MAN NOW. It recalled to life my crushed self-respect and my self-confidence, and inspired me with a renewed determination to be a FREEMAN. A man, without force, is without the essential dignity of humanity. Human nature is so constituted, that it cannot honor a helpless man, although it can pity him; and even this it cannot do long, if the signs of power do not arise. (FDAB: 286, original emphases)

The first passage displays Douglass’s romantic and religious influences; it swells with the longing for the freedom of the soul. The second passage, written without the demands of Garrison’s pacifist politics directing his pen, screams independence and force. It recommends violence—it advocates for the coming U.S. Civil War—to throw off tyranny and claim, defend, and even fulfill one’s honor and humanity.