The Soviet Union: Achieving full employment

[Part of the Soviet Union series ]

The Soviet labour 'market' was a peculiar one. Rather than the prevalence of unemployment, as we are used to, the Soviet Union not only achieved full employment, but also got to a situation where there were_shortages of labour,_even though a significant share of the population was working. In this post I clarify what does full employment mean in the Soviet context, and explain some aspects of their labour 'market' not covered in my previous post on this topic. As usual, this post covers the post-Stalin era. [1]

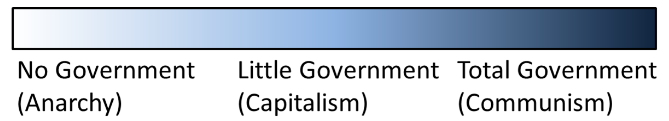

The official Soviet ideology contends that socialism is not only completely different from capitalism, but also in all respects (i.e. socially, economically, politically, culturally, and morally) superior to it. In order to substantiate this claim, the ideology cites a long list of achievements, one of them being that while unemployment is an endemic feature of capitalism, socialism abolishes it entirely and once and for all. If the term 'unemployment' denotes exclusively open unemployment of the registered kind or the dole, then the assertion is fully justified, because in the Soviet Union the payment of unemployment benefits was stopped as early as October 1930. On top of that, over the years the Soviet regime has succeeded in mobilizing for participation in the social economy the vast majority of able-bodied men and women of working age.*** (Porket, 1989)

This post draws mainly on János Kornai's The Socialist System (1992) and J.L. Porket's Work, Employment, and Unemployment in the Soviet Union (1989).

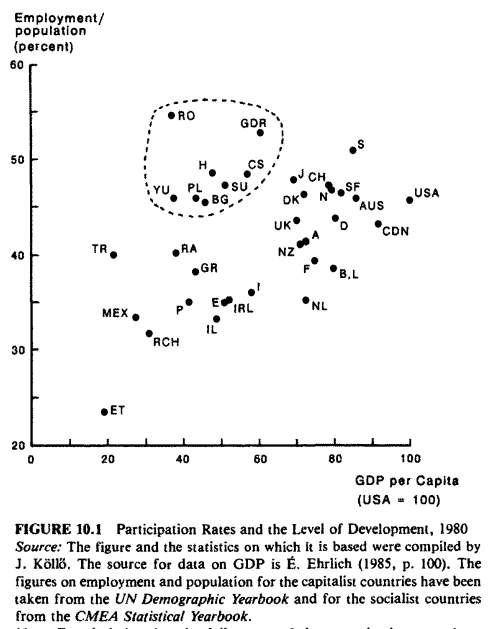

The first point I'll mention is the data backing up the claims in the introductory paragraph: The activity rates in socialist countries were far higher than the ones in the West

Kornai warns that economic development increases the participation rate, but even when taking this into account, the socialist economies still shine in that sense.

There is a loose positive relationship between the level of economic development and the participation rate. If one compares the participation rates of socialist and capitalist countries at the same level of economic development, it turns out that the socialist countries' participation rates are the highest on each level of economic development.

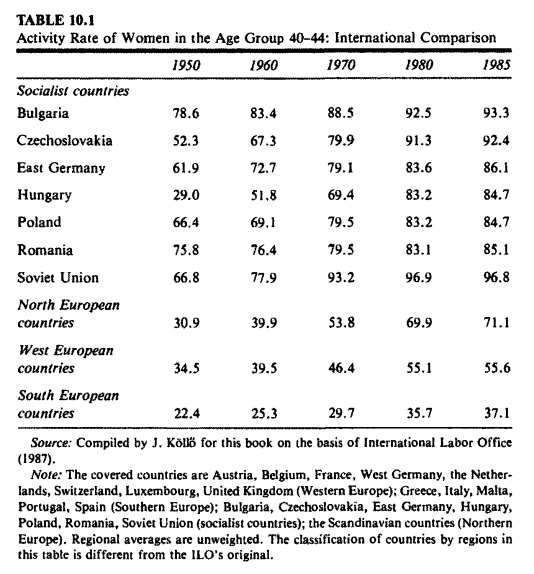

One key difference between the socialist systems and the West was a massive socialist lead in women's activity rate, which contributed to the overall participation rate. Assuming crudely that women are half of the population, in 1980, assuming South European levels of women's activity rate implies a difference of 61.2 percentage points. Half of that is roughly 30 percentage points, which then have to be translated to employment/population, which will be less, because not everyone works. While I don't have data at hand for this final step, it is plausible that the higher rate of activity of women explain a big part of this increased overall activity rate.

We could think that this was due to an underlying feminist trend, where the Soviet State pursued and achieved gender equality. In the West, women entering the workforce was a result of changing norms of what was admissible for women to do, where previously some occupations were seen as male-only. The reason for this increased women activity rate in the USSR was that the socialist system needed workers, and women make up half of the population. The feminist interpretation, that seems plausible given de jure legislation regarding maternity leave, for example, faces several issues, like the abortion ban (reversed after Stalin in 1955)[2] and legal barriers to divorce in 1936 (to encourage population growth), the fact that there were almost no women in the higher echelons of the Party, and that women were still the main carers of children and main doers of household chores ( Mespoulet, 2015 )

But why full employment and labour shortages? Kornai argues that this wasn't because of an explicit policy to ensure full employment (even though the right and the duty to work were enshrined in the Constitution of the USSR). Achievement of full employment was a by-product of the socialist system in its pursuit of growth. This right to work, however, wasn't present from the beginning, but it's granted once the system has reached a point where full employment obtains.

Once this process has occurred and been rated by the official ideology among the system's fundamental achievements, it becomes an "acquired right" of the workers, a status quo that the classical system cannot and does not wish to reverse. Thenceforth full employment is laid down as a guaranteed right (and to a degree, so is a permanent workplace, as will be seen later). This is an actual, not just a nominally proclaimed right, ensured not only by the principles and practical conventions of employment policy but by the operating mechanism of the classical system, above all the chronic, recurrent shortage of labor. Permanent full employment certainly is a fundamental achievement of the classical system, in terms of several ultimate moral values. It has vast significance, and not simply in relation to the direct financial advantage in steady earnings. It plays additionally a prominent part in inducing a sense of financial security, strengthening the workers' resolve and firmness toward their employers, and helping to bring about equal rights for women.

The situation of chronic labour shortage (In Poland, for example, there were over 90 vacancies per job seeker) is seen as problematic by the Party, as labour shortage means the productive plans are harder to fulfill, and so planners tend to react by investments in labour saving capital goods, promoting population growth, etc.

From the factory manager's point of view, this situation induces them to 'hoard' workers: perhaps more workers will be needed in the future, but maybe they will not be available for hire, so they hire them now. At a given point in time, then, a factory will have more workers than it actually needs. This, combined with low job activity from some (demotivated) workers leads to the concept that Kornai terms 'unemployment on the job'.

***While open unemployment of the registered kind is absent and the labour force participation rate is high, open unemployment of the unregistered kind has not disappeared. In addition, there is chronic and general overmanning as well as voluntary and involuntary employment below skill level, i.e. underutilization of employed persons in terms of both working time and educational qualifications. Although underutilization of employed persons keeps open unemployment down, it has a number of adverse consequences, which should not be overlooked. Amongst other things it contributes to slack work discipline, low labour productivity, divorce of rewards from performance, low real wages, inflation, and shortages of consumer goods and services. Thus, from the point of view of the situation in the labour market or the relation between the supply of and demand for labour the official Soviet economy may be characterized as a high-employment one; from that of the utilization of the employed labour force or the relation between labour input and the output of economic values it may be characterized as a low-productivity one; and from that of the income received by individuals for playing the role of employed persons it may be characterized as a low-incentive one. (Porket, 1989)

One way to think about this: Assume that we have two economies that consist of people digging ditches (people like ditches in this world) and related activities. Economy A uses the most efficient arrangement of people and capital for the task, but there exists some unemployment due to inefficiencies here and there, so that only 95% of working age people who want to work actually do so.

Economy B is the same as Economy A, but it has 100% employment, due to a government mandate that those who would be unemployed are to be hired. People take shifts to dig ditches.

At the end of the day, the same length/number of ditches are dug in both economies.

Some people would like Economy B: everyone has a salary, and people work less. Great, isn't it? But the problem is that -assuming no companies go bankrupt- a) Salaries are lower b) No extra labor is easily available for new projects c) Some people work and earn less than they would like to

At the end of the day, it comes to a redistribution of wages and work time: Some win and some lose. Alternatively, this could be seen as a tax on the employed to redistribute to the unemployed. But the economic consequences of doing that in the long term are problematic [3].

This is overmanning, a form of hidden unemployment. If Economy B actually used the efficient number of workers, they would have, say, an employment rate of 80%. In this case, the economy would be producing the same in aggregate.

Overmanning is a type of hidden unemployment. Porket distinguishes three kinds:

- Employment in part-time jobs when a full-time job is desired

- Employment where people are forced to work in jobs for which they are overqualified

- Employment where companies employ more people than they need, given their technological conditions (the case of Economy B)

He estimates overmanning to be 10-15% of the total workforce.

We now jump to post-Stalin history.

Between 1957 and 1961, so called 'antiparasite laws' were adopted in most of the USSR. These measures were to force everyone to have a 'socially useful work', and noncompliers were punished with 2-10 years of forced labour.

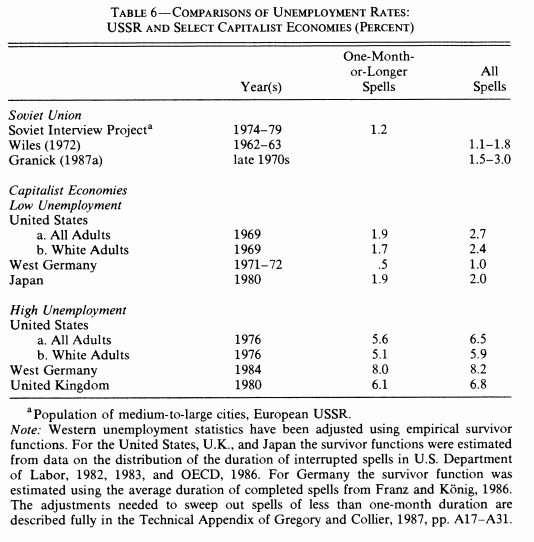

Some open unregistered unemployment existed, but was low:

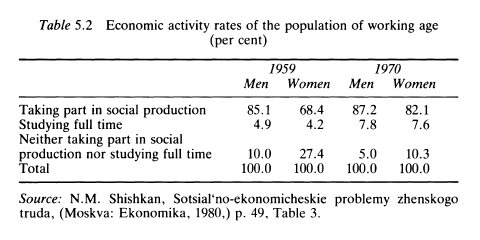

Not surprisingly, this open unemployment stemming from a lack of vacancies was not officially quantified, so that its accurate volume remains a guess. But it is known that in 1959 10.0 per cent of men of working age and 27.4 per cent of women of working age neither participated in social production nor studied full time (see Table 5.2 below). And six years later E. Manevich asserted that 20 per cent of the able-bodied population did not take part in social production. Obviously, the 1959 figures did not refer exclusively to jobless persons keen to have a job, yet unable to get it because of a lack of vacancies. They also covered non-employed persons uninterested in playing the roles of workers or collective farmers. Nevertheless, they clearly indicate the existence of at least some involuntary open unemployment, albeit unregistered. Concerning specifically youth unemployment, it was reported (although not documented) by Basile Kerblay that 'according to Gosplan statistics, 25.2 per cent of young people aged between 16 and 17 and 13.9 per cent of those aged between 18 and 19 were unemployed in medium-sized towns in 1965, compared with 1. 7 per cent for other age groups'. Besides admitting the occurrence of both non-employment and involuntary open unemployment, naturally without using the term 'unemployment' which was reserved for capitalism, Soviet sources further admitted that employed persons were frequently underutilized, either because of involuntary employment below skill level, or because of overmanning. In order to remove this particular cause of overmanning, E. Manevich proposed in 1965 and again in 1969 a solution that in fact amounted to open registered unemployment. Instead of enterprises, special organizations should be responsible for the placement of the workers made redundant in connection with technological progress. Simultaneously, while between jobs, the workers in question should be provided for materially by the state. Not surprisingly, the proposal was not implemented. Open registered unemployment and unemployment benefits were unacceptable to the regime, because its ideology contended that socialism liquidated unemployment entirely and once for all and that under it technological progress went hand in hand with full employment of the able-bodied population. Thus, restrictions on dismissals were not lifted, so that enterprises shedding surplus workers remained responsible for their placement. (Porket, 1989)

Under the (1976) constitution, citizens had the right to work (i.e. to guaranteed employment and pay in accordance with the quantity and quality of their work, and not below the state-established minimum), including the right to choose their trade or profession, type of job and work in accorance with their inclinations, abilities, training and education, albeit subject to the caveat of taking into account the needs of socieety. On the other hand, it was the duty of and a matter of honour for every able-bodied citizen to work conscientiously in his/her chosen, socially useful occupation, and strictly to observe work discipline. Socially useful work and its results determined a person's status in society. Evasion of socially useful work was incompatible with the principles of socialist society [...] Moreover, the labour situation was contradictory. 34 On the one hand, open registered unemployment was absent, economic activity rates were high, full employment of the able-bodied population was alleged, and complaints of labour-deficit areas and a shortage of labour at the national level abounded. On the other hand, open unregistered unemployment was not unknown, overmanning at the enterprise level was chronic and general, quite a few qualified individuals were voluntarily or involuntarily employed below their skill level, labour-surplus areas were to be found, and employment in the official economy was evaded. This contradiction was reflected in Soviet discussions on the country's manpower resources. The prevailing view asserted that labour resources were inadequate, meaning by it that the available labour supplies lagged behind the effective demand that was incorporated in enterprise plans and backed up with funds. In contrast, a minority view contended that labour resources were completely adequate, but were utilized irrationally.

To sum up, the official unemployment rate was zero, almost by institutional definition: You couldn't sign up for unemployment benefits. Companies hoarded labour

However, non-registered unemployment existed for people who had quit their jobs and moved to another location, or had just begun working. While at an aggregate level, there were many more jobs than workers, in a micro scale, the geographical and skill distribution of these jobs did not match efficiently with the location and skills of the workforce. Despite this, the Soviet Union managed a very high employment rate, on par with the concept of full employment in the west.

Breaking down this by parts, a fraction were people switching jobs: since a) there were no unemployment benefits, people had lots of incentives to quickly look for another job. b) There were lots of vacancies c) 'Uninterrupted service' a legal concept that had an impact in social security benefits. If a worker was without employment for more than three weeks, they would lose that status d) Antiparasite laws that made punishable not having a 'socially useful' job for more than four months.

Other part of this unregistered unemployment were women who quit their jobs to be mothers.

Yet another part was youth unemployment. Young (<18) people were entitled to a variety of privileges, like having to work less hours for the same pay a full time worker would get. Ceteris paribus, companies preferred older workers. The USSR reacted to this by imposing quotas on companies (Between 0.5 and 10% of the workforce had to be <18). The rate of (unregistered) unemployment for this group was 1-5%.

Further, to easen up the transition from school or university to work, the State planned which companies would hire which worker in advance, which sounds like it would solve any problem, but

In practice, the system functions far from smoothly. It has difficulties in balancing supply and demand. There are exemptions from it, particularly on grounds of health and family circumstances. Due to changes in their plans or needs, enterprises frequently refuse to hire the graduates directed to them. Some graduates fail to show up at their assigned posts. Others do turn up, but leave before the expiry of the three-year period, inter alia, because they are not given work

Conclusion

Taking into account unregistered unemployment the Soviet economy achieved what in the West is typically called full employment (At least in the sense that almost everyone who wanted to work had a job), with rates below 5%. This compares favourably with capitalist economies at their best, and it's significantly better than capitalist economies undergoing a recession ( Gregory and Collier, 1988 , Ellman 1979 )

Rates of activity among women were high due to the need for more workers.

However, companies was plagued by overmanning due to the incentives mentioned above, and while measures were taken to try to reduce it, it still persisted.

David, H. P. (1974). Abortion and family planning in the Soviet Union: public policies and private behaviour. Journal of biosocial science , 6 (04), 417-426.

Ellman, M. (1979). Full employment—lessons from state socialism. De Economist , 127 (4), 489-512.

Field, M. G. (1956). The re-legalization of abortion in Soviet Russia. New England Journal of Medicine , 255 (9), 421-427.

Gregory, P. R., & Collier Jr, I. L. (1988). Unemployment in the Soviet Union: Evidence from the Soviet interview project. The American Economic Review , 613-632.

Kornai, J. (1992). The socialist system: The political economy of communism . Oxford University Press.

Mespoulet, M. (2006). Women in Soviet society. Cahiers du CEFRES , (30), 7.

Porket, J. L. (1989). Work, employment and unemployment in the Soviet Union . Springer.

Spufford, F. (2010). Red plenty . Faber & Faber.

[1] During Stalin's time, until 1956, workers couldn't legally quit their jobs without permission from the company's management. Quitting was a criminal offence. The State could compulsorily move workers from one company to another. Work discipline was enforced throughout the Soviet era, but the harshness of punishments decreased after Stalin.

Explicity, the official attitude was reiterated by L.F. Il'ichev in ecember 1961: communism and work were inseparable, communism was not a society of lazy-bones, an aggregate of loafers. (Porket, 1989)

Even after Stalin, worker strikes remained illegal, but some incidents did occur.

[2] An even then, it wasn't because of a greater respect for women's rights, but because women were having abortions anyways, and illegal abortions are generally less safe. The relegalisation decree wasn't publicised, to avoid further increases in abortion rates, which illustrates that the Party attitude towards abortion was closer to a technical problem (Will this measure promote growth?) rather than a matter of rights, which was closer to Lenin's views. (Field, 1956 )

While no official policy has been publicly promulgated, much emphasis is placed on 'the fight against abortion'. Potential dangers are publicized through extensive dissemination of brochures, medical bulletins, posters, and related materials. Some Soviet literature expresses a sense of moral indignation and censures women seeking abortion. Most research focuses on possible somatic sequelae. As one Soviet colleague explained to me, 'Every child must be wanted . . . abortion is available . . . but we must restrict abortion in spite of the permission for abortion.' Legal abortion is viewed as only a slightly lesser evil than illegal abortion. ( David, 1974 )

[3] Both economies have the same citizens and preferences, so citizens in Economy A already have a job-length distribution that they like. In Economy B, people would want to earn more (by working more), but they can't.

What about the unemployed in Economy A? If there are unemployment benefits, that will come from the incomes of workers, so perhaps the final distribution of salaries could be the same as in Economy B. If there were no productivity losses from job and wages redistribution, it would be a zero sum game. If there are, however -and Porket mentions that that was the case - then forcing full employment makes everyone worse off in the aggregate, and in the long run.

Workers, having now an advantage over employers displayed less work ethic, absenteeism, and could threaten employers with leaving if they were to be disciplined (This, after the Stalin period).

[4] Under Stalin, higher education mostly meant engineering. Half of university students pursued degrees in engineering, the rest were pure sciences, agricultural sciences, and medicine. Humanities and social science departments were mostly defunded. ( Spufford, 2011 )

Comments from WordPress

[…] How the Soviets achieved full employment. […]

[…] The Soviet Union: Achieving full employment […]

The Soviet Union had full employment and labor shortages simply because the government monopolistically set wages below the market-clearing equilibrium. Some firms avoided labor shortages by paying extra (in cash or in kind) under the table.

[…] workers had to be repressed and coerced into working as the State demanded. (I talked about this here and here) The problems the forced translation of labour from farm to factory caused with […]

"At least in the sense that almost everyone who wanted to work had a job" 'not working' was illegal in ussr, you were forced to work.

[…] I think it serves as a first approximation. One possible explanation for this particular table is overmanning: Employing more people than necessary for a variety of reasons explored in the linked post. Other […]

In academic work, please cite this essay as:

Ricón, José Luis, “The Soviet Union: Achieving full employment”, Nintil (2016-07-30), available at https://nintil.com/the-soviet-union-achieving-full-employment/.

- The Soviet Union: From farm to factory. Stalin's Industrial Revolution

- The Soviet Union series

Communism and Computer Ethics

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

The Life of the Soviet Worker

Mark B. Smith, University of Cambridge.

- Published: 06 January 2015

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The Soviet Union was the workers’ state and worker culture, broadly defined, coloured the whole of the Soviet experience. At the centre of the most transformative Soviet project of all, Stalin’s industrial revolution of 1928–41, workers benefited from specific privileges and from affirmative action, though they also suffered the misery of rapid industrial change. After 1953, they enjoyed a heyday of modest material advances and moral certainties, marked by the sense that society respected at least some of their values and would do so forever. But this sense was not shared by all Soviet workers, and lifestyles varied by industry, skill level, and region. And the heyday faded as shortages became increasingly difficult to endure, and then ended, as Gorbachev’s reforms destroyed the comforts that remained. A positive worker identity, but not a coherent class consciousness, survived through to perestroika , and helped to sustain the dynamic of Soviet history.

More than any other Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev had something of the worker about him. Sometimes labelled a peasant at heart, with his obsession with maize and his earthy wit, Khrushchev was certainly born in the countryside. But he moved to the city and became a skilled metalworker; he joined the party as an industrial recruit during the civil war; and he was promoted through the hierarchy of the party bureaucracy thanks to the affirmative action that favoured the industrial proletariat during the First Five-Year plan.

Khrushchev’s manners, enthusiasms, successes, his unpredictable rise, the crises that conditioned him—up to a point, the very trajectory of his biography—were inseparable from those of the ordinary Soviet worker. It was during the Khrushchev era that the Soviet Union belatedly became a majority urban society; soon after that, industrial labour displaced all other groups to become the statistically dominant section of the Soviet workforce. In power, Khrushchev reformed the political economy of the USSR sufficiently to transform many workers’ living standards. His own perceptions of justice, equality, and popular material improvement, monstrously refracted as they might have been by his participation in Stalin’s terror and by his own privileged existence at the top of the Soviet elite, converged, in important ways, with the moral economy of the Soviet worker.

What happened after 1953 to Soviet workers—primarily full-time factory workers, but those in other working-class occupations too—was thus as important as what happened before. But what happened before was the creation of a whole new sense, historically unparalleled, of what it meant to be a worker. The Soviet Union was the workers’ state, and while historians have often emphasized the exploitation of the working class during and after Stalinism, worker culture, broadly defined, nevertheless coloured the whole of the Soviet experience. Workers were always celebrated. They were at the centre of the most transformative Soviet project of all, Stalin’s industrial revolution of 1928–41. Especially during the first half of that revolution, workers benefited from specific privileges and from affirmative action, though they also suffered the dreadful misery of rapid industrial change. Many in the Brezhnev generation, born in the decade or so before 1917, started their careers as workers before gaining an industrial higher education and entering the ranks of the technical intelligentsia. Later in Soviet history, many such men and women, who had been formed by working class culture, could be found higher in the ruling order.

Capable, at a stretch, of remembering what it was like to be a worker, such people had nevertheless risen out of the working class. For this lucky minority, the workers’ state offered a ladder into the technical and administrative elites. For those who remained, by the post-Stalin era, it offered a workers’ standard of living that was much closer to that of the bosses than in capitalist economies. But it did not offer a framework in which Soviet working-class consciousness could solidify. Many historical investigations have sought to resolve a related paradox. For a large phalanx of leading labour historians writing in the 1970s and 1980s, the Russian working class in 1917 was so aware of its own class interests and so capable of projecting them in the wider social and political arena of national life that it accomplished the historic achievement of the Russian Revolution. Yet by the 1930s, Soviet workers had lost their sense of belonging to a class that could systematically take collective action to enhance its own interests. Why was this? Perhaps it was a consequence of Stalinist repression and thus working class atomization—and perhaps, or perhaps not, this process dated back to the revolution and civil war. Perhaps it was a result of the mass influx of peasants into the cities, undermining conventional self-understandings of worker identity. Or perhaps workers played the game according to the rules of material advance that Stalin laid down, making rational calculations to serve their own self-interest rather than that of their class as a whole: perhaps they took the chance when it came to rise out of their class rather than to improve their lot alongside their fellow workers. 1

Lacking its own representation and its own unmediated voice, the Soviet working class atrophied. In some ways it was exploited and repressed. But Soviet workers, as individuals, families, and working collectives, remained at the centre of the Soviet project. After 1953, they enjoyed a timeless heyday of modest material advances and moral certainties, marked by the sense that society respected at least some of their basic values and would do so forever. 2 But this sense was not shared by all Soviet workers, and lifestyles (and in all probability attitudes) varied by industry, skill level, and region. And the heyday faded as shortages became increasingly difficult to endure, especially in the provinces, and then it ended, as Gorbachev’s reforms suddenly destroyed the comforts that remained. A positive worker identity, but not a coherent class consciousness, survived through to perestroika , and helped to sustain the dynamic of Soviet history.

The Decline and Fall of the Soviet Working Class, 1917–53

It all started so well. The Bolsheviks took power in October 1917 thanks to the support of a radicalized working class, especially in the bigger cities. As a result, the political mythology of the Soviet Union from start to end derived in substantial measure from the heroism of the working class.

In 1917, skilled workers in Petrograd and Moscow, those who were the most aware of their class identity, led the struggle for workers’ control, and for collective wage bargaining across ever larger units of the working population. As 1917 went on, workers and Bolsheviks converged on the most revolutionary of paths. Women played their part. Fundamental to the street protests of the February Revolution, they were incorporated into the labour movement as the revolutionary year progressed. Male workers took seriously women’s workplace grievances but had no time for gender as a broader issue: feminism was bourgeois, and the position of women in the movement was decisively subordinate. Factory committees and soviets were naturally masculine arenas, where decisions were taken by acclamation and the workers with the loudest voices and the most fearsome presence carried the day. Gender differences fed into the iconography of the workers’ revolution. One of its most enduring symbols was the burly, red, unshiftable blacksmith, lit by the sun, gatekeeper of the future workers’ state. 3

It became clear very quickly that the workers’ state would not be an arena of working-class power. The working class of the revolution started to come apart during the civil war. As Petrov-Vodkin showed in his 1920 painting of an echoing cityscape at the back of Our Lady of Petrograd, 1918 , the population of the great cities had fallen dramatically. Petrograd itself saw a decline from 2.5 million residents to 700,000 between 1917 and 1920. 4 Many workers returned to their villages, diluting class identity, endangering their mutual understanding with the Bolsheviks. By the end of the civil war, the Bolsheviks still wanted to build a workers’ socialism, but they had to rebuild the economy first; they had to raise productivity and reinstitute labour discipline. It was at the Tenth Party Congress in 1921 that they introduced the New Economic Policy and a way of doing politics that was formally less receptive to dissent. In order to attain their goals of a workers’ state governed by the ethics of socialism, therefore, Lenin and the ruling circle agreed to introduce shop floor relations that would undermine working-class organization and autonomy.

In this sense, an original sin had been committed. The immediate interests of the workers diverged from those of their new masters, a process that accelerated during the 1930s when the Stalinist elite effectively smashed the remnants of working-class consciousness. Yet the Soviet leadership could never depart, and perhaps it never wanted to, from one of the revolution’s ultimate logics, the elevation of the workers. This was, after all, the workers’ state. All sorts of people enjoyed the capitalist-style good life in the 1920s, arguably at the expense of the workers. But a raft of careful rhetorical strategies placed workers at the heart of Soviet life. From the earliest part of the Soviet era, citizens were invited to construct their own identities, to ascribe themselves to classes, to write their own biographies. 5

It was in this context that industrial relations settled down during the New Economic Policy (NEP) after a rash of strikes in 1920 and 1921. Perhaps workers were exhausted and hoodwinked, perhaps they were sufficiently class conscious to make appropriate use of their unions and to press their interests within the boundaries of the possible. Perhaps they were prepared to accept a trade-off: in exchange for abandoning working class involvement in politics, they accepted an improving standard of living, diminishing their class identity in the process. 6 Workers’ sense of themselves as a class was probably also undermined by the conflicting demands of their urban and rural selves (many workers continued to spend time in their native villages). On the Soviet periphery, in particular, ethnicity added further complexity to the mix. 7 Trade unions had certainly been weakened—undermined by the logic that going on strike put one in opposition to the requirements of the workers’ state, and thinned out by the removal of practical functions, including some of the administration of welfare payments—but in some industries, they retained the respect of their members.

The First Five-Year Plan (1928–32) marked the onset of Stalinism. In crude economic terms it amounted to breakneck industrialization, urbanization, and agricultural collectivization, bringing all the premature death and misery to workers and peasants that one might expect from a speeded-up industrial revolution. Stalinism was a ruthlessly extractive political economy which viciously subordinated the living standards of workers (and much more, of peasants) to the promise of a soi-disant socialist order, and ultimately a communist utopia. It also sought to entrench the elite, the boss class in the factories, party, and local soviets: though in Stalin’s ideology-obsessed ruling circle, many of whose members continued to live relatively modestly, this seems to have been a secondary consideration, or an intermediate necessity. Workers faced a horrible reality: their society cared nothing for them as individual human beings, and valued them instead as mere units of production.

And these units were to be replicated on a mass scale. Cities were built out of nothing, gargantuan industrial plants were constructed on barren steppe, existing factories and workers’ districts grew until they were unrecognizable. The flood of peasants caused a ‘ruralization of the cities’. In little more than a decade, workers had increased by almost three times as a sector of the population; 12 per cent in 1928, they were 32.5 per cent in 1939. The industrial workforce doubled between 1928 and 1932; the number of construction workers rose by four times. The impact on workers’ living standards was catastrophic. Wages fell rapidly during the First Five-Year Plan, in contradistinction to what the plan had laid down. True, wages improved for a spell in the middle 1930s. But wages only reflected part of the terrible impoverishment wreaked by industrialization; in Leningrad, a well-provisioned city, workers’ consumption of meat dropped 72 per cent and fruit by 63 per cent between 1928 and 1933. Fatal workplace accidents were widespread. The welfare provisions that had been introduced after the revolution were puny in the face of this onslaught. Some of them, notably unemployment benefit, were eliminated altogether. 8

The workers’ world turned upside down. This was the result of deliberate disruption on the epic scale: during the Cultural Revolution (1928–30), youth thumbed its nose at experience. At the same time, central planning, charged with creating economic order, instead unleashed chaos. Dealing with chaos was the workers’ new reality. Labour exchanges should have methodically matched workers to vacancies, but many workers simply downed tools and followed the rumour of better paid work, better conditions, and better housing, travelling hundreds of miles on the off chance. Or they fled misery, trouble, and episodes of unemployment. Peasants left their villages in huge numbers, running away from collectivization, spurning even the best jobs in a new kolkhoz for what they deemed a better chance in a factory. In Magnitogorsk, a tent city grew up around the emerging steelworks on the empty steppe. On Turksib, a prestige railway project in the Kazakh republic, men and women desperate for work turned up at the site and were hired without reference to the proper procedures. 9

As Wendy Goldmam has shown, women workers underwrote industrialization. By 1935, 42 per cent of the industrial workforce was female. They worked in industries, such as construction, which had been closed to them under capitalism, though they often found themselves confined to certain roles and skill levels, so a form of sex segregation remained. Women’s unpaid domestic labour helped to pay for this industrial revolution, in effect releasing capital that could be invested in industrial expansion. The chaos unleashed by breakneck industrialization, combined with the strict penal code by which it was formally governed, ensured that a reserve of labour was required to keep the system fluid: very often, this reserve was provided by flexible but geographically tied women. Industrial and social policy seemed to play with women’s aspirations; some of the helpful welfare measures that had been introduced in the 1920s were rolled back in the mid-1930s, especially with the introduction of a pro-natalist family agenda. 10

The other side of chaos was repression. This could amount to outright violence, as in the crushing of strikes and rebellions, such as at Teikovo, in Ivanovo oblast’ , in 1932. Or repression might consist in implied violence. In December 1938, for example, workers who left their jobs could be prosecuted; the following month, if they were twenty minutes late for the start of the work day, they had to answer to the criminal law. In 1940, the laws were tightened further. And repression could be pernicious: in 1932, internal passports were introduced, formally, at least, making it more difficult for an urban worker to up sticks and tramp off to find better work in a different town (for peasants, it was even worse). For Donald Filtzer, everything about Stalinist industrialization was repressive. It was the elite and workers in conflict: it wilfully destroyed working-class solidarity. Wage differentiation set worker against worker. Robbed of recognizable class consciousness, Filtzer goes on, workers resisted in ways that reflected their very atomization. They worked slowly or carelessly, chatted too much or took too many breaks. In a sense this was resistance; in another sense, it was a reconfiguration of shop floor culture. This reconfiguration depended on the reduction of unemployment, eliminating one of the great working class horrors (levels had run at 10 per cent during the NEP). And it changed the way that workers exercised control over the processes of production. Before, this control had been a product, for example, of the workplace arteli , self-organizing groups of workers, which recruited new labour as well as helping with such things as the housing of their members. Such explicitly organized groups were inimical to Stalinism, which eliminated them, but the workers informally retained some of the functions of autonomy: management was unable systematically to regulate factory life because of the chaos that the industrial revolution had unleashed. 11

Even in the midst of immiseration, workers were thus able to extract some control over their lives. Yet conditions which so damaged basic standards—sanitation, nutrition, safety—were only one half of workers’ experience. The other half was an extraordinary enhancement of their formal status and their ability to construct a sense of who they were. The problem was that this did not enhance workers as a class; it enhanced them as individuals, and some more than others. Some of the same processes of positive discrimination that had applied in the early years of Soviet power were dramatically amplified during the First Five-Year plan. Sheila Fitzpatrick describes how workers were promoted through the ranks, especially during the Cultural Revolution, when the regime encouraged aggressive rhetorical assaults on ‘bourgeois’ specialists. Those with the right proletarian credentials were fast-tracked into institutes of higher technical education, appointments in factory management, senior engineering roles, and positions in the Komsomol and party. 12 In November 1929, the quota for working-class entry to industrial educational institutes was shifted upwards to 70 per cent. In 1933 and 1934, 65 per cent of the students at these institutions had a worker heritage. But social mobility took people out of the working class, gave such ex-workers new ‘class’ interests, and set in train the stratification of society that would be more apparent after the war. In any case, pro-worker affirmative action largely ceased in 1935. By 1938, only 44 per cent of students at industrial institutes were working class. Soviet workers made up a smaller proportion of party members, falling from 40.9 per cent of the party in 1933 to 18.2 per cent in 1941. 13

In 1929, shock workers arrived on the scene. The title and some associated material advantages were awarded to better performing workers. By the summer of 1931, two-thirds of workers enjoyed the designation. While Donald Filtzer puts forward evidence that the remainder expressed their dislike and anger, Hiroaki Kuromiya argues that the shock worker principle created new networks of support for the Soviet project that eclipsed and then dismantled the opposition that it prompted. 14 Shock work most likely elevated the status of the Soviet worker as a symbol and of some Soviet workers as individuals, rather than of the working class as a class. Later, in August 1935, coalminer Aleksei Stakhanov hewed fourteen times the target for his shift. In an initially uncertain sequence of steps, the regime seized on the achievement and used the Stakhanovite label to reward norm-busting workers, often young men in priority industries. During the period through to the war, as many as a third of trade union members were Stakhanovites. Once awarded a high-end separate apartment, or a new motorcycle, or other material inducements, top Stakhanovites would become part of the high culture of the Soviet workplace, participating in an ongoing ritual of special conferences and festivals that constantly displayed the significance of the proletarian achievement. But for their leading Western historian, Lewis Siegelbaum, the top echelon of the Stakhanovites was not a workers’ aristocracy, but ‘part of the highest stratum of Soviet society’. They transcended their status as workers. ‘Never before,’ Siegelbaum argues, ‘had workers been the object of such attention and adulation.’ Yet Stakhanovism further differentiated wages, forcing lower-level workers to work harder to earn an adequate wage, often on piece rates, subduing the workforce as a whole. 15 Inevitably, Stakhanovites infuriated some of their co-workers. At the moment when workers were extravagantly celebrated in national culture, the working class was losing further coherence.

After the Germans invaded, many workers who were not drafted into the army were required to remain in their factory, back in the rear, subject to a still tougher regimen of working practices. Others, who lived in territory more directly threatened by the Nazis, were forced to evacuate, complete with their plant, to new locations further east. Hatred of the enemy and determination to defend the motherland kept productivity high: workers played their part in the Soviet industrial triumph of the Second World War. The experience strengthened ethnic rather than class ties (and Russianness was especially celebrated). 16 And they were still finding their own individual way to survive gross material desperation. Not all workers embraced the shift to the even greater self-sacrifice which the regime required for victory. In September 1941, officials noted that groups of textile workers in Ivanovo oblast’ had downed tools before the end of the working day, with the intention of protesting against their ten-hour shifts; a rash of incidents amounted to a ‘strike mood’. Other workers continued the illegal tramp to new factories, running away from difficulties or towards a better opportunity. A tough 1944 decree re-targeted the ‘deserters’. 17 Yet out of the mass destruction of the war came a new approach to industrial labour.

The late Stalinist era (1945–53) occasioned very significant changes, though the evidence is contradictory. Dense archival research has proved that ordinary workers’ living conditions in many cities were unspeakable: malfunctioning sanitation, no domestic water, feeble local infrastructure, desperate overcrowding. Crime was rife. Meanwhile, most of the draconian Stalinist labour code remained intact. Young workers suffered especially. Many had lost close relatives during the war; some were orphans. Their crude training programmes amounted even to indentured labour. Yet the war still changed everything. It had created expectations, however transient, that sacrifice deserved reward; it reminded all kinds of citizens, including many officials, that the promise of the revolution must now be renewed; and its physical destructiveness was so great that new policies were needed simply to rebuild industry and allow basic urban life to go on. The end of rationing in 1947 was often remembered as a populist measure. Legal changes of 1951 were a faint harbinger of the gentler labour code that is associated with Khrushchev. Work attendance was now no longer formally connected to the disbursement of welfare benefits. Most striking of all, a housing construction programme got under way, and significant numbers of workers were rehoused in better conditions. 18

The Soviet Worker’s Heyday of Mixed Comforts, 1953–91

Although some essential foundations of social reform were laid between 1945 and 1953, the life of the Soviet worker still reached a nadir during late Stalinism. Stalinist government remained arbitrary, uninterested in the fate of individual workers, and thus incapable of adequately alleviating the catastrophic impact of the war on their living standards. For all the complexity of periodization, 1953 was a great disjuncture, leading to de-Stalinization, which redefined the relationship between the newly normalized application of power and the fate of individually respected citizens. In 1956, the year of the secret speech, the labour code was greatly lightened. It was no longer a criminal offence to move of one’s own volition to a new job, and the aggressive punishments for workplace infractions were shelved. Trade unions became more substantial. The right to work was more obviously protected, as managers could no longer sack workers so easily. 19 More generally, the social rights that were laid down most extensively, but during the Stalin years meretriciously, in the 1936 constitution, started to gain meaning. The most dramatic change in workers’ lives came about because of the mass housing programme. While the origins of this epochal social reform lay in the Second World War and late Stalinism, the programme only took off in the mid-1950s, after Khrushchev had decided that it should. He claimed in December 1963 that 108 million Soviet citizens had improved their housing conditions since 1954; and it was certainly true that Soviet per capita construction towered over that of all other European countries between 1957 and 1963. 20 With the programme focused on the cities, and with much new housing formally owned by industrial plants, workers disproportionately benefited.

The result of this was a highly imperfect equalization of living standards. ‘Obsessing about equality’ ( uravnilovka ) had been rejected as a principle during the early years of Stalinism. By contrast, an egalitarian ambition and ethic was crucial to the development of policy during the Khrushchev and Brezhnev years, notwithstanding the ongoing formal rejection of ‘petty equalization’, and the corruption and declining social mobility of late socialism. It was a complicated and untidy process, but one which gave a very distinctive quality to Soviet working class life between the 1950s and 1980s. Over the two decades from 1956 the difference between higher and lower wages fell, the lowest wages rose disproportionately, and incomes for higher groups (excluding their additional privileges) often remained steady. The ratio of average wages among the top 10 per cent to the bottom 10 per cent fell from 8:1 to 5:1; the income of engineering-technical employees was 166 per cent that of workers in 1955, but only 127 per cent in 1973. On the one hand, this was the improvement of workers’ conditions, and on the other it was the ‘proletarianization’ of some engineering–technical intelligentsia (ITR) jobs. 21 On a micro scale, the gap between workers and their bosses in any given factory was smaller than in capitalist countries. Workers, trade union officials, and management at certain favoured plants all enjoyed access to some of the same privileges; at the Kirov Metal Works in Leningrad, the polyclinics had a high reputation, and so a worker there might have enjoyed easier access to good healthcare than a manager elsewhere. True, workers in certain industries retained their privileges. In 1975, a coal miner still earned more than double the wages of a textile worker, and 1.7 times the average wage. Nevertheless, the shift towards greater equality was deliberate. Khrushchev-era reforms increased the minimum wage, part of the wider programme of making workers’ living standards a priority, and subsequent wage reforms in the 1960s and 1970s further narrowed the gap between higher and lower earners. Thus the director of an industrial trust earned eleven times the minimum wage in 1960, but 6.5 times the minimum in 1975 (admittedly, he also enjoyed many non-monetary privileges and the benefits of his profitable connections). 22

Workers retained their cachet in the workers’ state. They were at the centre of the utopian aspirations of the Khrushchev era. At the completion of one construction project, and before starting the next, the main heroic worker in the film The Heights ( Vysota , dir. A. Zarkhi, 1957) promises to build a Soviet industrial cityscape that will be visible ‘from Mars’. Even during the Brezhnev period, workers continued to be co-opted into participation in the vanguard of the socialist project. A member of the Saratov intelligentsia, born around 1950, remembered in 2002 that during late socialism she had ‘sincerely wanted’ to join the party, ‘but conditions were such that they picked party members from among workers. I never was a worker. I have nothing against physical labour, but nowhere could I write on an application that I had been a proletarian’. 23 Meanwhile, the privileges of workers in climatically extreme zones, especially the Far North and Far East, were entrenched. People travelled there in their hundreds of thousands to triple their pay. Conditions were arduous. Facilities were often crude. In Bratsk, in Siberia, 30,000 workers moved on from the hydroelectric plant between 1966 and 1970, one third, apparently, because of poor quality housing and childcare. 24 They did not fear unemployment. Neither did workers in conventional factories in more ordinary places, where shop floor discipline suffered and payment incentives were inadequate to prevent the uncontrollable growth of the second economy. But in 1962, the population faced price rises on basic goods, and workers believed they were worst affected.

Women workers remained central to the industrial project, not least because of their combined domestic and factory duties. In both arenas, women were subordinate, and subordination in one reinforced subordination in the other. They made a disproportionate contribution to the ranks of the low paid and badly skilled. Yet they might be glamorized; the film Mum got Married ( Mama vyshla zamuzh , dir. Vitalii Mel’nikov, 1969) shows female building workers sunbathing in their underwear. In other contexts, women were valorized. Female workers on one of the signature construction projects of late socialism, the Baikal-Amur Railway (BAM), were described in heroic terms in media profiles. The gap between representation and reality was wide, or perhaps cultural representations of all types made female workers vulnerable; many women left the BAM worksite prematurely, and cases of sexual abuse and verbal bullying, and this in the 1970s and 1980s, were legion. 25 It did not seem much advance on 1917. Seventy years after the revolution, the lifecycle of the Soviet worker had reached a dead end.

If Soviet workers were central to the success of the revolution in 1917, they were part of the problem by the 1980s. As they had done since the 1930s, workers exercised personal autonomy in ways that could be inconsistent with high productivity and thus with the grander goals of the Soviet project. During late socialism a lax shop floor culture was exacerbated by excessive time spent moonlighting and queuing. Andropov’s anti-corruption drive and Gorbachev’s perestroika were both, in part, responses. But the latter was the bluntest of reform programmes. Many workers sensed this: that they were at risk of losing a social system that in important ways had served them well. Finally, some of them found their voice. Miners struck in the summer of 1989. Their demands were inconsistent with the trajectory of Gorbachev’s economic policies. They wanted better wages and working conditions, and a measure of control over the workplace, at the expense of the central ministries. Although the latter demand suggested something of Gorbachev’s decentralizing vision, the miners, like many other workers, voiced mistrust of the Government. 26 Their failed intervention was the last episode in the mythology of the Soviet working class.

Cultures of Working-class Life

The discussion so far has focused on work and living standards, broadly defined. Yet from its earliest days, the Bolshevik regime announced its determination to eliminate illiteracy and to create a revolutionary culture that specifically fostered, rather than excluded, the working class. Founded in 1917, the Proletkult was charged with making existing forms of high culture more accessible to a proletarian audience, and making it easier for workers themselves to participate in the creation of cultural forms. The Proletkult limped on to 1932, but was really a phenomenon of the revolutionary period. 27 Other organizations, such as the Russian Association of Proletarian Writers, were also associated with the mission. This was a fundamentally optimistic vision of the possibilities of working class life, but it was replaced by a top-down approach to cultural production during the Stalin period, albeit one founded on the accessible aesthetic of Socialist Realism.