1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Philosophy, One Thousand Words at a Time

The Meaning of Life: What’s the Point?

Author: Matthew Pianalto Categories: Ethics , Phenomenology and Existentialism , Philosophy of Religion Word Count: 1000

Editors’ note: this essay and its companion essay, Meaning in Life: What Makes Our Lives Meaningful? both explore the concept of meaning in relation to human life. This essay focuses on the meaning of life as a whole, whereas the other addresses meaning in individual human lives.

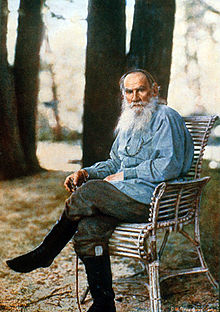

At the height of his literary fame, the novelist Leo Tolstoy was gripped by suicidal despair. [1] He felt that life is meaningless because, in the long run, we’ll all be dead and forgotten. Tolstoy later rejected this pessimism in exchange for religious faith in life’s eternal, divine significance.

Tolstoy’s outlook—both before and after his conversion—raises many questions:

- Does life’s having meaning depend on a supernatural reality?

- Is death a threat to life’s meaning?

- Is life the sort of thing that can have a “meaning”? In what sense?

Here we will consider some approaches to questions about the meaning of life. [2]

1. Questioning the Question

Many philosophers begin thinking about the meaning of life by asking what the question itself means. [3] Life could refer to all lifeforms or to human life specifically. This essay focuses on human life, but it is worth considering how other things might have or lack meaning, too. [4] This can help illuminate the different meanings of meaning .

Sometimes, we use “meaning” to refer to the origin or cause of something’s existence. If I come home to a trashed house, I might wonder, “What is the meaning of this?” Similarly, we might wonder where life comes from or how it began; our origins may tell us something about other meanings, like our value or purpose.

We also use “meaning” to refer to something’s significance or value . Something can be valuable in various ways, such as by being useful, pleasing, or informative. We might call something meaningless if it is trivial or unimportant.

“Meaning” can also refer to something’s point or purpose . [5] Life could have some overarching purpose as part of a divine plan, or it might have no such purpose. Perhaps we can give our lives purpose that they did not previously possess.

Notice that even divine purposes may not always satisfy our desire for meaning: suppose our creator made us to serve as livestock for hyper-intelligent aliens who will soon arrive and begin to farm us. [6] We might protest that this is not the most meaningful use of our human potential! We may not want our life-story to end as a people-burger.

Indeed, a thing’s meaning can also be its story . The meaning of life might be the true story of life’s origins and significance. [7] In this sense, life cannot be meaningless, but its meaning might be pleasing or disappointing to us. When people like Tolstoy regard life as meaningless, they seem to be thinking that the truth about life is bad news. [8]

2. Supernaturalism

Supernaturalists hold that life has divine significance. [9] For example, from the perspective of the Abrahamic religions, life is valuable because everything in God’s creation is good . Our purpose is to love and glorify God. We are all part of something very important and enduring : God’s plan.

Much of the contemporary discussion about the meaning of life is provoked by skepticism about traditional religious answers. [10] The phrase “the meaning of life” came into common usage only in the last two centuries, as advances in science, especially evolutionary theory, led many to doubt that life is the product of intelligent, supernatural design. [11] The meaning of life might be an especially perplexing issue for those who reject religious answers.

3. Nihilism

Nihilists think that life, on balance, lacks positive meaning. [12] Nihilism often arises as a pessimistic reaction to religious skepticism: life without a divine origin or purpose has no enduring significance.

Although others might counter that life can have enduring significance that doesn’t depend on a supernatural origin, such as our cultural legacy, nihilists are skeptical. From a cosmic perspective, we are tiny specks in a vast universe–and often miserable to boot! Even our most important cultural icons and achievements will likely vanish with the eventual extinction of the species and the collapse of the solar system.

4. Naturalism

Naturalists suggest that the meaning of life is to be found within our earthly lives. Even if life possesses no supernatural meaning, life itself may have inherent significance. [13] Things are not as bad as nihilists claim.

Some naturalists argue that life—at least human life—has objectively valuable features, such as our intellectual, moral, and creative abilities. [14] The meaning of life may be to develop these capacities and put them to good use. [15]

Other naturalists are subjectivists about life’s meaning. [16] Existentialists , for example, argue that life has no meaning until we give it meaning by choosing to live for something that we find important. [17]

Critics (including nihilists and supernaturalists) argue that the naturalists are fooling themselves. What naturalists propose as sources of meaning in life are at best a distraction from life’s lack of ultimate or cosmic significance (if naturalism is true). What is the point of personal development and good works if we’ll all be dead sooner or later?

Naturalists may respond that the point is in how these activities affect our lives and relationships now rather than in some distant, inhuman future. [18] Feeling sad or distressed over our lack of cosmic importance might be a kind of vanity we should overcome. [19] Some also question whether living forever would necessarily add meaning to life; living forever might be boring! [20] Having limited time may be part of what makes some of our activities and experiences so precious. [21]

5. Conclusion

In Douglas Adams’ novel The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy , the supercomputer Deep Thought is prompted to discover “the meaning of life, the universe, and everything.” After 7 ½ million years of computation, Deep Thought determines that the answer is…

forty-two .

Reflecting on this bizarre result, Deep Thought muses, “I think the problem, to be quite honest with you, is that you’ve never actually known what the question is.” [22]

Adams may be wise to offer some comic relief. [23] Furthermore, given the various meanings of “meaning,” perhaps there is no single question to ask and thus no single correct answer.

Tolstoy’s crisis is a reminder that feelings of meaninglessness can be distressing and dangerous. [24] However, continuing to search for meaning in times of doubt may be one of the most meaningful things we can do. [25]

[1] Tolstoy (2005 [1882]). For discussion of Tolstoy’s rediscovery of meaning that extends his ideas beyond the specific religious outlook he adopted, see Preston-Roedder (2022).

[2] For more detailed overviews of the meaning of life, see Metz (2021) and the entries on the meaning of life by Joshua Seachris and Wendell O’Brien in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

[3] Ayer (2008) suspects the question is incoherent. For a response, see Nielsen (2008). For helpful discussion of the meanings of meaning, see Thomas (2019).

[4] For discussion of meaning beyond humans (and agents), see Stevenson (2022).

[5] Notice that purpose appears to be one type of value, as discussed in the preceding paragraph.

[6] Nozick (1981) develops this point about purpose; Nozick (2008) offers the key points, too. In a different spirit, the ancient Daoist philosophy of Zhuangzi (2013) provides some perspective on the advantages of being “useless” (having no purpose) and the dangers of being “useful.”

[7] On this proposal of the meaning of life as narrative, see Seachris (2009). A similar approach that emphasizes the notion of interpretation rather than story or narrative is proposed in Prinzing (2021).

[8] A starter list of life’s features that might lead one to tell such a story about life: war, poverty, physical and mental illness, natural disasters, addiction, labor exploitation and other injustices, and pollution. For more, see Benatar (2017).

[9] Some, like Craig (2013), argue vigorously that life can have meaning only if supernaturalism is true. For further discussion and examples, see discussions of supernaturalism in Seachris, “The Meaning of Life: Contemporary Analytic Perspectives” and Metz (2021).

[10] See Landau (1997) and Setiya (2022), Ch. 6, for discussion of the origin of the phrase.

[11] Nietzsche’s discussion of the “death of God” in The Gay Science (2001 [1882]) reflects these sorts of concerns.

[12] For recent defenses of this view, see Benatar (2017) and Weinberg (2021).

[13] See I. Singer (2009) for a wide-ranging naturalist approach. Wolf’s (2010, 2014) approach to meaning in life is one of the most widely accepted views amongst contemporary philosophers.

[14] For a helpful discussion of the idea that some things might be objectively valuable, see Ethical Realism by Thomas Metcalf.

[15] Metz (2013) and P. Singer (1993) defend this sort of view of meaning in life. Transhumanists would argue that the best uses of our abilities will be those that help us overcome the problems, like disease and mortality, that beset humans and may transform us in substantial ways: perhaps we can achieve a natural form of immortality through technology! On transhumanism, see Messerly (2022).

[16] Representative subjectivists include Taylor (2000) and Calhoun (2015). Susan Wolf’s works (2010 and 2014) develop a “hybrid” account of meaning that combines objective and subjective elements.

[17] For classic expressions of this existentialist view, see Sartre (2021 [1943]) and Beauvoir (2018 [1947]). For a brief overview of existentialist philosophy, see Existentialism by Addison Ellis. For a more detailed, contemporary overview, see Gosetti-Ferencei (2020).

[18] On this point, see Nagel (1971), Nagel (1989), and “The Meanings of Lives” in Wolf (2014). For further discussion see Kahane (2014).

[19] Marquard (1991); see Hosseini (2015) for additional discussion. Albert Camus makes a similar point, invoking the notion of “moderation,” at the end of The Rebel (1992 [1951]).

[20] Williams (1973) gives the classic expression of this idea. For a brief overview of Williams’ argument, see Is Immortality Desirable? , by Felipe Pereira.

[21] Of course, this outlook does mean that death can sometimes rob people of potential meaning, since death can be untimely. But death would not erase the meaningfulness of whatever one had already experienced or achieved. For arguments concerning whether death harms the individual who dies, see Is Death Bad? Epicurus and Lucretius on the Fear of Death by Frederik Kaufman.

[22] Adams (2017), Chapters 27-28. Asking a computer to give us the answer might also be a problem.

[23] For additional comic relief, see the film Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life (1983). Such playfulness may seem irreverent of these “deep” philosophical questions, but Schlick (2017 [1927]) argued that the meaning of life is to be found in play!

[24] For discussion of crises of meaning and an introduction to psychological research on meaning in life, see Smith (2017).

[25] William Winsdale relates that the existential psychiatrist Viktor Frankl was once asked to “express in one sentence the meaning of his own life” (in Frankl (2006), 164-5). After writing his answer, he asked his students to guess what he wrote. A student said, “The meaning of your life is to help others find the meaning of theirs.” Frankl responded, “That is it exactly. Those are the very words I had written.”

Adams, Douglas (2017). The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy . Del Rey. Originally published in 1979.

Ayer, A.J. (2008). “The Claims of Philosophy.” In: E.D. Klemke and Seven M. Cahn, eds. The Meaning of Life, Third Edition . Oxford University Press: 199-202.

Beauvoir, Simone de (2018). The Ethics of Ambiguity . Open Road Media. Originally published in French in 1947.

Benatar, David (2017). The Human Predicament . Oxford University Press.

Calhoun, Cheshire (2015). “Geographies of Meaningful Living,” Journal of Applied Philosophy 32(1): 15-34.

Camus, Albert (1992). The Rebel . Vintage. Originally published in French in 1951.

Craig, William Lane (2013). “The Absurdity of Life Without God.” In: Jason Seachris, ed. Exploring the Meaning of Life . Wiley-Blackwell: 153-172.

Frankl, Viktor E. (2006). Man’s Search for Meaning . Beacon Press.

Gosetti-Ferencei, Jennifer Anna (2020). On Being and Becoming: An Existentialist Approach to Life . Oxford University Press.

Hosseini, Reza (2015). Wittgenstein and Meaning in Life . Palgrave Macmillan.

Kahane, Guy (2014). “Our Cosmic Insignificance.” Noûs 48(4): 745–772.

Landau, Iddo (2017). Finding Meaning in an Imperfect World . Oxford University Press.

— (1997). “Why Has the Question of the Meaning of Life Arisen in the Last Two and a Half Centuries?” Philosophy Today 41(2): 263-269.

Marquard, Odo (1991). “On the Dietetics of the Expectation of Meaning.” In: In Defense of the Accidental . Translated by Robert M. Wallace. Oxford University Press: 29-49.

Messerly, John (2022). Short Essays on Life, Death, Meaning, and the Far Future .

Metz, Thaddeus (2013). Meaning in Life . Oxford University Press .

— (2021). “The Meaning of Life.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2022 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.).

Nagel, Thomas (1971). “The Absurd,” Journal of Philosophy 68(20): 716-727.

— (1989). The View From Nowhere . Oxford University Press.

Nielsen, Kai (2008). “Linguistic Philosophy and ‘The Meaning of Life.’” In: E.D. Klemke and Seven M. Cahn, eds. The Meaning of Life, Third Edition . Oxford University Press: 203-219.

Nietzsche, Friedrich (2001). The Gay Science . Translated by Josephine Nauckhoff. Cambridge University Press. Originally published in German in 1882.

Nozick, Robert (1981). Philosophical Explanations . Harvard University Press.

— (2018), “Philosophy and the Meaning of Life,” in: E.D. Klemke and Seven M. Cahn, eds. The Meaning of Life, Fourth Edition . Oxford University Press: 197-204.

O’Brien, Wendell. “The Meaning of Life: Early Continental and Analytic Perspectives.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Last Accessed 12/19/2022.

Preston-Roedder, Ryan (2022). “Living with absurdity: A Nobleman’s guide,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research (Early View) .

Prinzing, Michael M. (2021). “The Meaning of ‘Life’s Meaning,’” Philosopher’s Imprint 21(3).

Sartre, Jean-Paul (2021). Being and Nothingness . Washington Square Press. Originally published in French in 1943.

Schlick, Moritz (2017). “On the Meaning of Life,” in: In: E.D. Klemke and Seven M. Cahn, eds. The Meaning of Life, Third Edition . Oxford University Press: 56-65. Originally published in 1927.

Seachris, Joshua. “The Meaning of Life: Contemporary Analytic Perspectives.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Last Accessed 12/19/2022.

— (2009). “The Meaning of Life as Narrative.” Philo 12(1): 5-23.

Setiya, Kieran (2022). Life is Hard: How Philosophy Can Help Us Find Our Way . Riverhead Books.

Singer, Irving (2009). Meaning in Life, Vol. 1: The Creation of Value . MIT Press.

Singer, Peter (1993). How Are We to Live? Ethics in an Age of Self-Interest . Prometheus.

Smith, Emily E. (2017). The Power of Meaning . Crown.

Stevenson, Chad Mason (2022). “Anything Can Be Meaningful.” Philosophical Papers (forthcoming).

Taylor, Richard (2000). Good and Evil . Prometheus. Originally published in 1970.

Thomas, Joshua Lewis (2019). “Meaningfulness as Sensefulness,” Philosophia 47: 1555-1577.

Tolstoy, Leo (2005). A Confession . Translated by Aylmer Maude. Dover. Originally published in Russian in 1882.

Weinberg, Rivka (2021). “Ultimate Meaning: We Don’t Have It, We Can’t Get It, and We Should Be Very, Very Sad,” Journal of Controversial Ideas 1(1), 4.

Williams, Bernard (1973). “The Makropulos case: reflections on the tedium of immortality.” In: Problems of the Self: Philosophical Papers, 1956-1972 . Cambridge University Press: 82-100.

Wolf, Susan (2010). Meaning in Life and Why It Matters . Princeton University Press. ( Wolf’s lecture is also available at the Tanner Lecture Series website ).

— (2014). The Variety of Values . Oxford University Press.

Zhuangzi (2013). The Complete Works of Zhuangzi . Translated by Burton Watson. Columbia University Press.

Related Essays

Meaning in Life: What Makes Our Lives Meaningful? by Matthew Pianalto

Existentialism by Addison Ellis

Camus on the Absurd: The Myth of Sisyphus by Erik Van Aken

Nietzsche and the Death of God by Justin Remhof

Is Death Bad? Epicurus and Lucretius on the Fear of Death by Frederik Kaufman

Ancient Cynicism: Rejecting Civilization and Returning to Nature by G. M. Trujillo, Jr.

The Badness of Death by Duncan Purves

Is Immortality Desirable? by Felipe Pereira

Hope by Michael Milona & Katie Stockdale

Ethical Realism by Thomas Metcalf

PDF Download

Download this essay in PDF .

About the Author

Matthew Pianalto is a Professor of Philosophy at Eastern Kentucky University. He is the author of On Patience (2016) and several articles and book chapters on ethics. philosophy.eku.edu/pianalto

Follow 1000-Word Philosophy on Facebook and Twitter and subscribe to receive email notifications of new essays at 1000WordPhilosophy.com .

Share this:, 5 thoughts on “ the meaning of life: what’s the point ”.

- Pingback: Meaning in Life: What Makes Our Lives Meaningful? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Online Philosophy Resources Weekly Update | Daily Nous

- Pingback: Aristotle on Friendship: What Does It Take to Be a Good Friend? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Ancient Cynicism: Rejecting Civilization and Returning to Nature – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Qual o sentido da vida? (S03E06) – Esclarecimento

Comments are closed.

Discover more from 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

The Meaning of Life, Essay Example

Pages: 3

Words: 939

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

The meaning of life is one of the fundamental questions of philosophy. But what are the presuppositions that frame this question? On the one hand, the very question “what is the meaning of life?” means that life poses us with a problem about its meaning. This is to say that even if we accept a nihilistic position and state that life has no meaning, there is still the appearance of this question of meaning within a meaningless existence. This ties into a second presupposition at stake in this question: what do we intend by the concept of meaning and what do we intend by the concept of life? It would seem that on an intuitive level, when we talk about life, we are talking about any living thing. But is a living thing only something material, or can we consider immaterial phenomena, such as souls, as also living? From another perspective, when we talk about the meaning of life, are we therefore talking about the meaning of all life, such as plants and animals, or are we just talking about human beings? Are we discussing a multitude of meanings, for example, a specific meaning for a plant and a specific meaning for a human being, or are we discussing a singular meaning to which we belong?

In order to provide an entrance-way into these questions, I would like to use this opening discussion to set the framework for my approach: I would like to use the scientific tool of Ockham’s razor to minimize the number of propositions. When we are talking about meaning, therefore, we are talking about a singular meaning for everything. To say that everyone has their own meaning, in other words, is a rejection of the concept of meaning, because it takes on so many possible definitions that the particularity of the concept loses its force. At the same time, when we use the term life, I would like to mention all forms of life, human, plant, animal, and even possible immaterial forms of life, such as the soul. In other words, the meaning of life is one of the big questions of philosophy and therefore should have a universal answer, precisely because the extent of this question itself is one that is universal: in other words, the very power of this question lies in its apparent universality. My meaning of life cannot be different from your meaning of life, in other words, for the question to not merely be trivial: we need to think about a common meaning for all life to avoid this problem of triviality.

The question of meaning is often related to purpose. Why are we here? There is a reason for this presupposed in the question. From one perspective, I would like to believe that there is a purpose and a meaning, precisely for the reason stated above: even if we accept a nihilistic world in which there is no meaning and there is no purpose, we still have to accept that the question of meaning and purpose exists. In other words, if life is meaningless, where does the question of the meaning of life even come from? Is it merely an error of our consciousness? Is it merely a linguistic mistake, an illusion? If we cannot explain how the question emerges against a meaningless backdrop of nihilism, I think then we have to assume that the meaningless backdrop is flawed, and we have to pursue the question of meaning itself.

If our concept of the question of meaning and purpose therefore infers a meaning or purpose because of the very possibility of asking the question, and, furthermore, if this question must be universal, considering the totality of life, for the question itself to have any meaning, we must look for equally universal answers to this question. Here, I believe that the concept of happiness can play an important role. Happiness, of course, is also a notoriously difficult term to define. But we can approach it from its negative element: there are people who are unhappy, who are suffering. Certainly, there may be also some people who think they are happy but are not – in this case, they may be happy because they live in an illusion. But if we accept that the meaning of life is the same for all, that it is universal, then we can also make the proposition that happiness is also universal – namely, if unhappiness exists in the world and the meaning of life is universal then life as a whole must be driven towards happiness as opposed to the happiness of individuals.

This helps elucidate a possible definition of the meaning and purpose of life. We accept that we all have the same purpose and meaning for this question itself to have any meaning. Therefore, the concept of meaning holds for us all. Happiness is something desired, but not possessed by all. Accordingly, the meaning of life would be the movement to this universal happiness, the happiness of the creation as a whole. This is not an absurd idea and finds analogues in religious and secular thought. For example, in Christian philosophy as well as Islamic philosophy, we find the idea of the resurrection of the world and the justice for all. In Marxist philosophy, we find the common task of eliminating inequality in the world to create a happiness for all. In other words, our meaning of life is a process, a type of goal that we move towards that must be universal in its scope, since it addresses the fate of the universe as such and an attempt to improve life in all its forms.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

The Conduct of Monetary Policy, Essay Example

Effects of a Mobile Web-Based Pregnancy, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Question of the Month

What is the meaning of life, the following answers to this central philosophical question each win a random book. sorry if your answer doesn’t appear: we received enough to fill twelve pages….

Why are we here? Do we serve a greater purpose beyond the pleasure or satisfaction we get from our daily activities – however mundane or heroic they may be? Is the meaning of life internal to life, to be found inherently in life’s many activities, or is it external, to be found in a realm somehow outside of life, but to which life leads? In the internal view it’s the satisfaction and happiness we gain from our actions that justify life. This does not necessarily imply a selfish code of conduct. The external interpretation commonly makes the claim that there is a realm to which life leads after death. Our life on earth is evaluated by a supernatural being some call God, who will assign to us some reward or punishment after death. The meaning of our life, its purpose and justification, is to fulfill the expectations of God, and then to receive our final reward. But within the internal view of meaning, we can argue that meaning is best found in activities that benefit others, the community, or the Earth as a whole. It’s just that the reward for these activities has to be found here, in the satisfactions that they afford within this life, instead of in some external spirit realm.

An interesting way to contrast the internal and external views is to imagine walking through a beautiful landscape. Your purpose in walking may be just to get somewhere else – you may think there’s a better place off in the distance. In this case the meaning of your journey through the landscape is external to the experience of the landscape itself. On the other hand, you may be intensely interested in what the landscape holds. It may be a forest, or it may contain farms, villages. You may stop along the way, study, learn, converse, with little thought about why you are doing these things other than the pleasure they give you. You may stop to help someone who is sick: in fact, you may stay many years, and found a hospital. What then is the meaning of your journey? Is it satisfying or worthwhile only if you have satisfied an external purpose – only if it gets you somewhere else? Why, indeed, cannot the satisfactions and pleasures of the landscape, and of your deeds, be enough?

Greg Studen, Novelty, Ohio

A problem with this question is that it is not clear what sort of answer is being looked for. One common rephrasing is “What is it that makes life worth living?”. There are any number of subjective answers to this question. Think of all the reasons why you are glad you are alive (assuming you are), and there is the meaning of your life. Some have attempted to answer this question in a more objective way: that is to have an idea of what constitutes the good life . It seems reasonable to say that some ways of living are not conducive to human flourishing. However, I am not convinced that there is one right way to live. To suggest that there is demonstrates not so much arrogance as a lack of imagination.

Another way of rephrasing the question is “What is the purpose of life?” Again we all have our own subjective purposes but some would like to think there is a higher purpose provided for us, perhaps by a creator. It is a matter of debate whether this would make life a thing of greater value or turn us into the equivalent of rats in a laboratory experiment. Gloster’s statement in King Lear comes to mind: “As flies to wanton boys we are to the gods – they kill us for their sport.” But why does there have to be a purpose to life separate from those purposes generated within it? The idea that life needs no external justification has been described movingly by Richard Taylor. Our efforts may ultimately come to nothing but “the day was sufficient to itself, and so was the life.” ( Good and Evil , 1970) In the “why are we here?” sense of the question there is no answer. It would be wrong, however, to conclude that life is meaningless. Life is meaningful to humans, therefore it has meaning.

Rebecca Linton, Leicester

When the question is in the singular we search for that which ties all values together in one unity, traditionally called ‘the good’. Current consideration of the good demands a recognition of the survival crises which confront mankind. The threats of nuclear war, environmental poisoning and other possible disasters make it necessary for us to get it right. For if Hannah Arendt was correct concerning the ‘banality of evil’ which affected so many Nazi converts and contaminated the German population by extension, we may agree with her that both Western rational philosophy and Christian teaching let the side down badly in the 20th century.

If we then turn away from Plato’s philosophy, balanced in justice, courage, moderation and wisdom; from Jewish justice and Christian self-denial; if we recognize Kant’s failure to convince populations to keep his three universal principles, then shall we look to the moral relativism of the Western secular minds which admired Nietzsche? Stalin’s purges of his own constituents in the USSR tainted this relativist approach to the search for the good. Besides, if nothing is absolute, but things have value only relative to other things, how do we get a consensus on the best or the worst? What makes your social mores superior to mine – and why should I not seek to destroy your way? We must also reject any hermit, monastic, sect or other loner criteria for the good life. Isolation will not lead to any long-term harmony or peace in the Global Village.

If with Nietzsche we ponder on the need for power in one’s life, but turn in the opposite direction from his ‘superman’ ideal, we will come to some form of the Golden Rule [‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you’]. However, we must know this as an experiential reality. There is life-changing power in putting oneself in the place of the other person and feeling for and with them. We call this feeling empathy .

Persons who concentrate on empathy should develop emotional intelligence. When intellectual intelligence does not stand in the way of this kind of personal growth, but contributes to it, we can call this balance maturity . Surely the goal or meaning of human life is therefore none other than finding oneself becoming a mature adult free to make one’s own decisions, yet wanting everyone in the world to have this same advantage. This is good!

Ernie Johns, Owen Sound, Ontario

‘Meaning’ is a word referring to what we have in mind as ‘signification’, and it relates to intention and purpose. ‘Life’ is applied to the state of being alive; conscious existence. Mind, consciousness, words and what they signify, are thus the focus for the answer to the question. What seems inescapable is that there is no meaning associated with life other than that acquired by our consciousness, inherited via genes, developed and given content through memes (units of culture). The meanings we believe life to have are then culturally and individually diverse. They may be imposed through hegemony; religious or secular, benign or malign; or identified through deliberate choice, where this is available. The range is vast and diverse; from straightforward to highly complex. Meaning for one person may entail supporting a football team; for another, climbing higher and higher mountains; for another, being a parent; for another, being moved by music, poetry, literature, dance or painting; for another the pursuit of truth through philosophy; for another through religious devotions, etc. But characteristic of all these examples is a consciousness that is positively and constructively absorbed, engaged, involved, fascinated, enhanced and fulfilled. I would exclude negative and destructive desires; for example of a brutal dictator who may find torturing others absorbing and engaging and thus meaningful. Such cases would be too perverse and morally repugnant to regard as anything other than pathological.

The meaning of life for individuals may diminish or fade as a consequence of decline or difficult or tragic circumstances. Here it might, sadly, be difficult to see any meaning of life at all. The meaning is also likely to change from one phase of life to another, due to personal development, new interests, contexts, commitments and maturity.

Colin Brookes, Woodhouse Eaves, Leicestershire

It is clearly internet shopping, franchised fast food and surgically-enhanced boobs. No, this is not true. I think the only answer is to strip back every layer of the physical world, every learnt piece of knowledge, almost everything that seems important in our modern lives. All that’s left is simply existence. Life is existence: it seems ‘good’ to be part of life. But really that’s your lot! We should just be thankful that our lifespan is longer than, say, a spider, or your household mog.

Our over-evolved human minds want more, but unfortunately there is nothing more. And if there is some deity or malignant devil, then you can be sure they’ve hidden any meaning pretty well and we won’t see it in our mortal lives. So, enjoy yourself; be nice to people, if you like; but there’s no more meaning than someone with surgically-enhanced boobs, shopping on the net while eating a Big Mac.

Simon Maltman, By email

To ask ‘What is the meaning of life?’ is a poor choice of words and leads to obfuscation rather than clarity. Why so?

To phrase the question in this fashion implies that meaning is something that inheres in an object or experience – that it is a quality which is as discernible as the height of a door or the solidity of matter. That is not what meaning is like. It is not a feature of a particular thing, but rather the relationship between a perceiver and a thing, a subject and an object, and so requires both. There is no one meaning of, say, a poem, because meaning is generated by it being read and thought about by a subject. As subjects differ so does the meaning: different people evaluate ideas and concepts in different ways, as can be seen from ethical dilemmas. But it would be wrong to say that all these meanings are completely different, as there are similarities between individuals, not least because we belong to the same species and are constructed and programmed in basically the same way. We all have feelings of fear, attachment, insecurity and passion, etc.

So to speak of ‘the meaning of life’, is an error. It would be more correct to refer to the ‘meanings of life’, but as there are currently around six billion humans on Earth, and new psychological and cultural variations coming into being all the time, to list and describe all of these meanings would be a nigh on impossible task.

To ‘find meaning in life’ is a better way of approaching the issue, ie, whilst there is no single meaning of life, every person can live their life in a way which brings them as much fulfilment and contentment as possible. To use utilitarian language, the best that one can hope for is a life which contains as great an excess of pleasure over pain as possible, or alternatively, a life in which as least time as possible is devoted to activities which do not stimulate, or which do nothing to promote the goals one has set for oneself.

Steve Else, Swadlincote, Derbyshire

The meaning of life is not being dead.

Tim Bale, London

The question is tricky because of its hidden premise that life has meaning per se . A perfectly rational if discomforting position is given by Nietzsche, that someone in the midst of living is not in a position to discern whether it has meaning or not, and since we cannot step outside of the process of living to assess it, this is therefore not a question that bears attention.

However, if we choose to ignore the difficulties of evaluating a condition while inside it, perhaps one has to ask the prior question, what is the meaning of meaning ? Is ‘meaning’ given by the greater cosmos? Or do we in our freedom construct the category ‘meaning’ and then fill in the contours and colours? Is meaning always identical with purpose? I might decide to dedicate my life to answering this particular question, granting myself an autonomously devised purpose. But is this identical with the meaning of my life? Or can I live a meaningless life with purpose? Or shall meaning be defined by purpose? Some metaphysics offer exactly this corollary – that in pursuing one’s proper good, and thus one’s meaning, one is pursuing one’s telos or purpose. The point of these two very brief summaries of approaches to the question is to show the hazards in this construction of the question.

Karen Zoppa, The University of Winnipeg

One thing one can hardly fail to notice about life is that it is self-perpetuating. Palaeontology tells us that life has been perpetuating itself for billions of years. What is the secret of this stunning success? Through natural selection, life forms adapt to their environment, and in the process they acquire, one might say they become , knowledge about that environment, the world in which they live and of which they are part. As Konrad Lorenz put it, “Life itself is a process of acquiring knowledge.” According to this interpretation of evolution, the very essence of life (its meaning?) is the pursuit of knowledge : knowledge about the real world that is constantly tested against that world. What works and is in that sense ‘true’, is perpetuated. Life is tried and proven knowledge that has withstood the test of geological time. From this perspective, adopting the pursuit of knowledge as a possible meaning of one’s life seems, literally, a natural choice. The history of science and philosophy is full of examples of people who have done just that, and in doing so they have helped human beings to earn the self-given title of Homo sapiens – man of knowledge.

Axel Winter, Wynnum, Queensland

Life is a stage and we are the actors, said William Shakespeare, possibly recognizing that life quite automatically tells a story just as any play tells a story. But we are more than just actors; we are the playwright too, creating new script with our imaginations as we act in the ongoing play. Life is therefore storytelling. So the meaning of life is like the meaning of ‘the play’ in principle: not a single play with its plot and underlying values and information, but the meaning behind the reason for there being plays with playwright, stage, actors, props, audience, and theatre. The purpose of the play is self-expression , the playwright’s effort to tell a story. Life, a grand play written with mankind’s grand imagination, has this same purpose.

But besides being the playwright, you are the audience too, the recipient of the playwrights’ messages. As playwright, actor, and audience you are an heir to both growth and self-expression. Your potential for acquiring knowledge and applying it creatively is unlimited. These two concepts may be housed under one roof: Liberty. Liberty is the freedom to think and to create. “Give me liberty or give me death,” said Patrick Henry, for without liberty life has no meaningful purpose. But with liberty life is a joy. Therefore liberty is the meaning of life.

Ronald Bacci, Napa, CA

The meaning of life is understood according to the beliefs that people adhere to. However, all human belief systems are accurate or inaccurate to varying degrees in their description of the world. Moreover, belief systems change over time: from generation to generation; from culture to culture; and era to era. Beliefs that are held today, even by large segments of the population, did not exist yesterday and may not exist tomorrow. Belief systems, be they religious or secular, are therefore arbitrary. If the meaning of life is wanted, a meaning that will transcend the test of time or the particulars of individual beliefs, then an effort to arrive at a truly objective determination must be made. So in order to eliminate the arbitrary, belief systems must be set aside. Otherwise, the meaning of life could not be determined.

Objectively however, life has no meaning because meaning or significance cannot be obtained without reference to some (arbitrary) belief system. Absent a subjective belief system to lend significance to life, one is left with the ‘stuff’ of life, which, however offers no testimony as to its meaning. Without beliefs to draw meaning from, life has no meaning, but is merely a thing ; a set of facts that, in and of themselves, are silent as to what they mean. Life consists of a series of occurrences in an infinite now, divorced of meaning except for what may be ascribed by constructed belief systems. Without such beliefs, for many the meaning of life is nothing .

Surely, however, life means something . And indeed it does when an individual willfully directs his/her consciousness at an aspect of life, deriving from it an individual interpretation, and then giving this interpretation creative expression. Thus the meaning in the act of giving creative expression to what may be ephemeral insights. Stated another way, the meaning of life is an individual’s acts of creation . What, exactly is created, be it artistic or scientific, may speak to the masses, or to nobody, and may differ from individual to individual. The meaning of life, however, is not the thing created, but the creative act itself ; namely, that of willfully imposing an interpretation onto the stuff of life, and projecting a creative expression from it.

Raul Casso, Laredo, Texas

Rather than prattle on and then discover that I am merely deciding what ‘meaning’ means, I will start out with the assumption that by ‘meaning’ we mean ‘purpose.’ And because I fear that ‘purpose’ implies a Creator, I will say ‘best purpose.’ So what is the best purpose for which I can live my life? The best purpose for which I can live my life is, refusing all the easy ways to destroy. This is not as simple as it sounds. Refusing to destroy life – to murder – wouldn’t just depend on our lack of homicidal impulses, but also on our willingness to devote our time to finding out which companies have murdered union uprisers; to finding out whether animals are killed out of need or greed or ease; to finding the best way to refuse to fund military murder, if we find our military to be murdering rather than merely protecting. Refusing to destroy resources, to destroy loves, to destroy rights, turns out to be a full-time job. Oh sure, we can get cocky and say “Well, oughtn’t we destroy injustice? Or bigotry? Or hatred?” But we would be only fooling ourselves. They’re all already negatives: to destroy injustice, bigotry, and hatred is to refuse the destruction of justice, understanding, and love. So, it turns out, we finally say “Yes” to life, when we come out with a resounding, throat-wrecking “NO!”

Carrie Snider, By email

I propose that the knowledge we have now accumulated about life discloses quite emphatically that we are entirely a function of certain basic laws as they operate in the probably unique conditions prevailing here on Earth.

The behaviour of the most elementary forms of matter we know, subatomic particles, seems to be guided by four fundamental forces, of which electromagnetism is probably the most significant here, in that through the attraction and repulsion of charged particles it allows an almost infinite variation of bonding: it allows atoms to form molecules, up the chain to the molecules of enormous length and complexity we call as nucleic acids, and proteins. All these are involved in a constant interaction with surrounding chemicals through constant exchanges of energy. From these behaviour patterns we can deduce certain prime drives or purposes of basic matter, namely:

1. Combination (bonding).

2. Survival of the combination, and of any resulting organism.

3. Extension of the organism, usually by means of replication.

4. Acquisition of energy.

Since these basic drives motivate everything that we’re made of, all the energy, molecules and chemistry that form our bodies, our brains and nervous systems, then whatever we think, say and do is a function of the operation of those basic laws Therefore everything we think, say and do will be directed towards our survival, our replication and our demand for energy to fuel these basic drives. All our emotions and our rational thinking, our loves and hates, our art, science and engineering are refinements of these basic drives. The underlying drive for bonding inspires our need for interaction with other organisms, particularly other human beings, as we seek ever wider and stronger links conducive to our better survival. Protection and extension of our organic integrity necessitates our dependence on and interaction with everything on Earth.

Our consciousness is also necessarily a function of these basic drives, and when the chemistry of our cells can no longer operate due to disease, ageing or trauma, we lose consciousness and die. Since I believe we are nothing more than physics and chemistry, death terminates our life once and for all. There is no God, there is no eternal life. But optimistically, there is the joy of realising that we have the power of nature within us, and that by co-operating with our fellow man, by nurturing the resources of the world, by fighting disease, starvation, poverty and environmental degradation, we can all conspire to improve life and celebrate not only its survival on this planet, but also its proliferation. So the purpose of life is just that: to involve all living things in the common purpose of promoting and enjoying what we are – a wondrous expression of the laws of Nature, the power of the Universe.

Peter F. Searle, Topsham, Devon

“What is the meaning of life?” is hard to get a solid grip on. One possible translation of it is “What does it all mean?” One might spend a lifetime trying to answer such a heady question. Answering it requires providing an account of the ultimate nature of the world, our minds, value and how all these natures interrelate. I’d prefer to offer a rather simplistic answer to a possible interpretation of our question. When someone asks “What is the meaning of life?,” they may mean “What makes life meaningful?” This is a question I believe one can get a grip on without developing a systematic philosophy.

The answer I propose is actually an old one. What makes a human life have meaning or significance is not the mere living of a life, but reflecting on the living of a life.

Even the most reflective among us get caught up in pursuing ends and goals. We want to become fitter; we want to read more books; we want to make more money. These goal-oriented pursuits are not meaningful or significant in themselves. What makes a life filled with them either significant or insignificant is reflecting on why one pursues those goals. This is second-order reflection; reflection on why one lives the way one does. But it puts one in a position to say that one’s life has meaning or does not.

One discovers this meaning or significance by evaluating one’s life and meditating on it; by taking a step back from the everyday and thinking about one’s life in a different way. If one doesn’t do this, then one’s life has no meaning or significance. And that isn’t because one has the wrong sorts of goals or ends, but rather has failed to take up the right sort of reflective perspective on one’s life. This comes close to Socrates’ famous saying that the unexamined life is not worth living. I would venture to say that the unexamined life has no meaning.

Casey Woodling, Gainesville, FL

For the sake of argument, let’s restrict the scope of the discussion to the human species, and narrow down the choices to

1) There is no meaning of life, we simply exist;

2) To search for the meaning of life; and

3) To share an intimate connection with humankind: the notion of love.

Humans are animals with an instinct for survival. At a basic level, this survival requires food, drink, rest and procreation. In this way, the meaning of life could be to continue the process of evolution. This is manifested in the modern world as the daily grind.

Humans also have the opportunity and responsibility of consciousness. With our intellect comes curiosity, combined with the means to understand complex problems. Most humans have, at some point, contemplated the meaning of life. Some make it a life’s work to explore this topic. For them and those like them, the question may be the answer.

Humans are a social species. We typically seek out the opposite sex to procreate. Besides the biological urge or desire, there is an interest in understanding others. We might simply gain pleasure in connecting with someone in an intimate way. Whatever the specific motivation, there is something that we crave, and that is to love and be loved.

The meaning of life may never be definitively known. The meaning of life may be different for each individual and/or each species. The truth of the meaning of life is likely in the eye of the beholder. There were three choices given at the beginning of this essay, and for me, the answer is all of the above.

Jason Hucsek, San Antonio, TX

Next Question of the Month

The next question is: What Is The Nature Of Reality? Answers should be less than 400 words. Subject lines or envelopes should be marked ‘Question Of The Month’. You will be edited.

This site uses cookies to recognize users and allow us to analyse site usage. By continuing to browse the site with cookies enabled in your browser, you consent to the use of cookies in accordance with our privacy policy . X

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

The Oxford Handbook of Meaning in Life

Iddo Landau is a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Haifa, Israel. His publications include ‘The Meaning of Life sub specie aeternitatis ’ ( Australasian Journal of Philosophy , 2011) and Finding Meaning in an Imperfect World (Oxford University Press, 2017).

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions