- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write the Rationale of the Study in Research (Examples)

What is the Rationale of the Study?

The rationale of the study is the justification for taking on a given study. It explains the reason the study was conducted or should be conducted. This means the study rationale should explain to the reader or examiner why the study is/was necessary. It is also sometimes called the “purpose” or “justification” of a study. While this is not difficult to grasp in itself, you might wonder how the rationale of the study is different from your research question or from the statement of the problem of your study, and how it fits into the rest of your thesis or research paper.

The rationale of the study links the background of the study to your specific research question and justifies the need for the latter on the basis of the former. In brief, you first provide and discuss existing data on the topic, and then you tell the reader, based on the background evidence you just presented, where you identified gaps or issues and why you think it is important to address those. The problem statement, lastly, is the formulation of the specific research question you choose to investigate, following logically from your rationale, and the approach you are planning to use to do that.

Table of Contents:

How to write a rationale for a research paper , how do you justify the need for a research study.

- Study Rationale Example: Where Does It Go In Your Paper?

The basis for writing a research rationale is preliminary data or a clear description of an observation. If you are doing basic/theoretical research, then a literature review will help you identify gaps in current knowledge. In applied/practical research, you base your rationale on an existing issue with a certain process (e.g., vaccine proof registration) or practice (e.g., patient treatment) that is well documented and needs to be addressed. By presenting the reader with earlier evidence or observations, you can (and have to) convince them that you are not just repeating what other people have already done or said and that your ideas are not coming out of thin air.

Once you have explained where you are coming from, you should justify the need for doing additional research–this is essentially the rationale of your study. Finally, when you have convinced the reader of the purpose of your work, you can end your introduction section with the statement of the problem of your research that contains clear aims and objectives and also briefly describes (and justifies) your methodological approach.

When is the Rationale for Research Written?

The author can present the study rationale both before and after the research is conducted.

- Before conducting research : The study rationale is a central component of the research proposal . It represents the plan of your work, constructed before the study is actually executed.

- Once research has been conducted : After the study is completed, the rationale is presented in a research article or PhD dissertation to explain why you focused on this specific research question. When writing the study rationale for this purpose, the author should link the rationale of the research to the aims and outcomes of the study.

What to Include in the Study Rationale

Although every study rationale is different and discusses different specific elements of a study’s method or approach, there are some elements that should be included to write a good rationale. Make sure to touch on the following:

- A summary of conclusions from your review of the relevant literature

- What is currently unknown (gaps in knowledge)

- Inconclusive or contested results from previous studies on the same or similar topic

- The necessity to improve or build on previous research, such as to improve methodology or utilize newer techniques and/or technologies

There are different types of limitations that you can use to justify the need for your study. In applied/practical research, the justification for investigating something is always that an existing process/practice has a problem or is not satisfactory. Let’s say, for example, that people in a certain country/city/community commonly complain about hospital care on weekends (not enough staff, not enough attention, no decisions being made), but you looked into it and realized that nobody ever investigated whether these perceived problems are actually based on objective shortages/non-availabilities of care or whether the lower numbers of patients who are treated during weekends are commensurate with the provided services.

In this case, “lack of data” is your justification for digging deeper into the problem. Or, if it is obvious that there is a shortage of staff and provided services on weekends, you could decide to investigate which of the usual procedures are skipped during weekends as a result and what the negative consequences are.

In basic/theoretical research, lack of knowledge is of course a common and accepted justification for additional research—but make sure that it is not your only motivation. “Nobody has ever done this” is only a convincing reason for a study if you explain to the reader why you think we should know more about this specific phenomenon. If there is earlier research but you think it has limitations, then those can usually be classified into “methodological”, “contextual”, and “conceptual” limitations. To identify such limitations, you can ask specific questions and let those questions guide you when you explain to the reader why your study was necessary:

Methodological limitations

- Did earlier studies try but failed to measure/identify a specific phenomenon?

- Was earlier research based on incorrect conceptualizations of variables?

- Were earlier studies based on questionable operationalizations of key concepts?

- Did earlier studies use questionable or inappropriate research designs?

Contextual limitations

- Have recent changes in the studied problem made previous studies irrelevant?

- Are you studying a new/particular context that previous findings do not apply to?

Conceptual limitations

- Do previous findings only make sense within a specific framework or ideology?

Study Rationale Examples

Let’s look at an example from one of our earlier articles on the statement of the problem to clarify how your rationale fits into your introduction section. This is a very short introduction for a practical research study on the challenges of online learning. Your introduction might be much longer (especially the context/background section), and this example does not contain any sources (which you will have to provide for all claims you make and all earlier studies you cite)—but please pay attention to how the background presentation , rationale, and problem statement blend into each other in a logical way so that the reader can follow and has no reason to question your motivation or the foundation of your research.

Background presentation

Since the beginning of the Covid pandemic, most educational institutions around the world have transitioned to a fully online study model, at least during peak times of infections and social distancing measures. This transition has not been easy and even two years into the pandemic, problems with online teaching and studying persist (reference needed) .

While the increasing gap between those with access to technology and equipment and those without access has been determined to be one of the main challenges (reference needed) , others claim that online learning offers more opportunities for many students by breaking down barriers of location and distance (reference needed) .

Rationale of the study

Since teachers and students cannot wait for circumstances to go back to normal, the measures that schools and universities have implemented during the last two years, their advantages and disadvantages, and the impact of those measures on students’ progress, satisfaction, and well-being need to be understood so that improvements can be made and demographics that have been left behind can receive the support they need as soon as possible.

Statement of the problem

To identify what changes in the learning environment were considered the most challenging and how those changes relate to a variety of student outcome measures, we conducted surveys and interviews among teachers and students at ten institutions of higher education in four different major cities, two in the US (New York and Chicago), one in South Korea (Seoul), and one in the UK (London). Responses were analyzed with a focus on different student demographics and how they might have been affected differently by the current situation.

How long is a study rationale?

In a research article bound for journal publication, your rationale should not be longer than a few sentences (no longer than one brief paragraph). A dissertation or thesis usually allows for a longer description; depending on the length and nature of your document, this could be up to a couple of paragraphs in length. A completely novel or unconventional approach might warrant a longer and more detailed justification than an approach that slightly deviates from well-established methods and approaches.

Consider Using Professional Academic Editing Services

Now that you know how to write the rationale of the study for a research proposal or paper, you should make use of our free AI grammar checker , Wordvice AI, or receive professional academic proofreading services from Wordvice, including research paper editing services and manuscript editing services to polish your submitted research documents.

You can also find many more articles, for example on writing the other parts of your research paper , on choosing a title , or on making sure you understand and adhere to the author instructions before you submit to a journal, on the Wordvice academic resources pages.

How to Write the Rationale for a Research Paper

- Research Process

- Peer Review

A research rationale answers the big SO WHAT? that every adviser, peer reviewer, and editor has in mind when they critique your work. A compelling research rationale increases the chances of your paper being published or your grant proposal being funded. In this article, we look at the purpose of a research rationale, its components and key characteristics, and how to create an effective research rationale.

Updated on September 19, 2022

The rationale for your research is the reason why you decided to conduct the study in the first place. The motivation for asking the question. The knowledge gap. This is often the most significant part of your publication. It justifies the study's purpose, novelty, and significance for science or society. It's a critical part of standard research articles as well as funding proposals.

Essentially, the research rationale answers the big SO WHAT? that every (good) adviser, peer reviewer, and editor has in mind when they critique your work.

A compelling research rationale increases the chances of your paper being published or your grant proposal being funded. In this article, we look at:

- the purpose of a research rationale

- its components and key characteristics

- how to create an effective research rationale

What is a research rationale?

Think of a research rationale as a set of reasons that explain why a study is necessary and important based on its background. It's also known as the justification of the study, rationale, or thesis statement.

Essentially, you want to convince your reader that you're not reciting what other people have already said and that your opinion hasn't appeared out of thin air. You've done the background reading and identified a knowledge gap that this rationale now explains.

A research rationale is usually written toward the end of the introduction. You'll see this section clearly in high-impact-factor international journals like Nature and Science. At the end of the introduction there's always a phrase that begins with something like, "here we show..." or "in this paper we show..." This text is part of a logical sequence of information, typically (but not necessarily) provided in this order:

Here's an example from a study by Cataldo et al. (2021) on the impact of social media on teenagers' lives.

Note how the research background, gap, rationale, and objectives logically blend into each other.

The authors chose to put the research aims before the rationale. This is not a problem though. They still achieve a logical sequence. This helps the reader follow their thinking and convinces them about their research's foundation.

Elements of a research rationale

We saw that the research rationale follows logically from the research background and literature review/observation and leads into your study's aims and objectives.

This might sound somewhat abstract. A helpful way to formulate a research rationale is to answer the question, “Why is this study necessary and important?”

Generally, that something has never been done before should not be your only motivation. Use it only If you can give the reader valid evidence why we should learn more about this specific phenomenon.

A well-written introduction covers three key elements:

- What's the background to the research?

- What has been done before (information relevant to this particular study, but NOT a literature review)?

- Research rationale

Now, let's see how you might answer the question.

1. This study complements scientific knowledge and understanding

Discuss the shortcomings of previous studies and explain how'll correct them. Your short review can identify:

- Methodological limitations . The methodology (research design, research approach or sampling) employed in previous works is somewhat flawed.

Example : Here , the authors claim that previous studies have failed to explore the role of apathy “as a predictor of functional decline in healthy older adults” (Burhan et al., 2021). At the same time, we know a lot about other age-related neuropsychiatric disorders, like depression.

Their study is necessary, then, “to increase our understanding of the cognitive, clinical, and neural correlates of apathy and deconstruct its underlying mechanisms.” (Burhan et al., 2021).

- Contextual limitations . External factors have changed and this has minimized or removed the relevance of previous research.

Example : You want to do an empirical study to evaluate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the number of tourists visiting Sicily. Previous studies might have measured tourism determinants in Sicily, but they preceded COVID-19.

- Conceptual limitations . Previous studies are too bound to a specific ideology or a theoretical framework.

Example : The work of English novelist E. M. Forster has been extensively researched for its social, political, and aesthetic dimensions. After the 1990s, younger scholars wanted to read his novels as an example of gay fiction. They justified the need to do so based on previous studies' reliance on homophobic ideology.

This kind of rationale is most common in basic/theoretical research.

2. This study can help solve a specific problem

Here, you base your rationale on a process that has a problem or is not satisfactory.

For example, patients complain about low-quality hospital care on weekends (staff shortages, inadequate attention, etc.). No one has looked into this (there is a lack of data). So, you explore if the reported problems are true and what can be done to address them. This is a knowledge gap.

Or you set out to explore a specific practice. You might want to study the pros and cons of several entry strategies into the Japanese food market.

It's vital to explain the problem in detail and stress the practical benefits of its solution. In the first example, the practical implications are recommendations to improve healthcare provision.

In the second example, the impact of your research is to inform the decision-making of businesses wanting to enter the Japanese food market.

This kind of rationale is more common in applied/practical research.

3. You're the best person to conduct this study

It's a bonus if you can show that you're uniquely positioned to deliver this study, especially if you're writing a funding proposal .

For an anthropologist wanting to explore gender norms in Ethiopia, this could be that they speak Amharic (Ethiopia's official language) and have already lived in the country for a few years (ethnographic experience).

Or if you want to conduct an interdisciplinary research project, consider partnering up with collaborators whose expertise complements your own. Scientists from different fields might bring different skills and a fresh perspective or have access to the latest tech and equipment. Teaming up with reputable collaborators justifies the need for a study by increasing its credibility and likely impact.

When is the research rationale written?

You can write your research rationale before, or after, conducting the study.

In the first case, when you might have a new research idea, and you're applying for funding to implement it.

Or you're preparing a call for papers for a journal special issue or a conference. Here , for instance, the authors seek to collect studies on the impact of apathy on age-related neuropsychiatric disorders.

In the second case, you have completed the study and are writing a research paper for publication. Looking back, you explain why you did the study in question and how it worked out.

Although the research rationale is part of the introduction, it's best to write it at the end. Stand back from your study and look at it in the big picture. At this point, it's easier to convince your reader why your study was both necessary and important.

How long should a research rationale be?

The length of the research rationale is not fixed. Ideally, this will be determined by the guidelines (of your journal, sponsor etc.).

The prestigious journal Nature , for instance, calls for articles to be no more than 6 or 8 pages, depending on the content. The introduction should be around 200 words, and, as mentioned, two to three sentences serve as a brief account of the background and rationale of the study, and come at the end of the introduction.

If you're not provided guidelines, consider these factors:

- Research document : In a thesis or book-length study, the research rationale will be longer than in a journal article. For example, the background and rationale of this book exploring the collective memory of World War I cover more than ten pages.

- Research question : Research into a new sub-field may call for a longer or more detailed justification than a study that plugs a gap in literature.

Which verb tenses to use in the research rationale?

It's best to use the present tense. Though in a research proposal, the research rationale is likely written in the future tense, as you're describing the intended or expected outcomes of the research project (the gaps it will fill, the problems it will solve).

Example of a research rationale

Research question : What are the teachers' perceptions of how a sense of European identity is developed and what underlies such perceptions?

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology , 3(2), 77-101.

Burhan, A.M., Yang, J., & Inagawa, T. (2021). Impact of apathy on aging and age-related neuropsychiatric disorders. Research Topic. Frontiers in Psychiatry

Cataldo, I., Lepri, B., Neoh, M. J. Y., & Esposito, G. (2021). Social media usage and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence: A review. Frontiers in Psychiatry , 11.

CiCe Jean Monnet Network (2017). Guidelines for citizenship education in school: Identities and European citizenship children's identity and citizenship in Europe.

Cohen, l, Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education . Eighth edition. London: Routledge.

de Prat, R. C. (2013). Euroscepticism, Europhobia and Eurocriticism: The radical parties of the right and left “vis-à-vis” the European Union P.I.E-Peter Lang S.A., Éditions Scientifiques Internationales.

European Commission. (2017). Eurydice Brief: Citizenship education at school in Europe.

Polyakova, A., & Fligstein, N. (2016). Is European integration causing Europe to become more nationalist? Evidence from the 2007–9 financial crisis. Journal of European Public Policy , 23(1), 60-83.

Winter, J. (2014). Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning: The Great War in European Cultural History . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

The AJE Team

See our "Privacy Policy"

Ensure your structure and ideas are consistent and clearly communicated

Pair your Premium Editing with our add-on service Presubmission Review for an overall assessment of your manuscript.

Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

How do you Write the Rationale for Research?

- By DiscoverPhDs

- October 21, 2020

What is the Rationale of Research?

The term rationale of research means the reason for performing the research study in question. In writing your rational you should able to convey why there was a need for your study to be carried out. It’s an important part of your research paper that should explain how your research was novel and explain why it was significant; this helps the reader understand why your research question needed to be addressed in your research paper, term paper or other research report.

The rationale for research is also sometimes referred to as the justification for the study. When writing your rational, first begin by introducing and explaining what other researchers have published on within your research field.

Having explained the work of previous literature and prior research, include discussion about where the gaps in knowledge are in your field. Use these to define potential research questions that need answering and explain the importance of addressing these unanswered questions.

The rationale conveys to the reader of your publication exactly why your research topic was needed and why it was significant . Having defined your research rationale, you would then go on to define your hypothesis and your research objectives.

Final Comments

Defining the rationale research, is a key part of the research process and academic writing in any research project. You use this in your research paper to firstly explain the research problem within your dissertation topic. This gives you the research justification you need to define your research question and what the expected outcomes may be.

The term rationale of research means the reason for performing the research study in question.

This article will answer common questions about the PhD synopsis, give guidance on how to write one, and provide my thoughts on samples.

An abstract and introduction are the first two sections of your paper or thesis. This guide explains the differences between them and how to write them.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

PhD stress is real. Learn how to combat it with these 5 tips.

Fieldwork can be essential for your PhD project. Use these tips to help maximise site productivity and reduce your research time by a few weeks.

Ellen is in the third year of her PhD at the University of Oxford. Her project looks at eighteenth-century reading manuals, using them to find out how eighteenth-century people theorised reading aloud.

Annabel is a third-year PhD student at the University of Glasgow, looking at the effects of online self-diagnosis and health information seeking on the patient-healthcare professional relationship.

Join Thousands of Students

Setting Rationale in Research: Cracking the code for excelling at research

Knowledge and curiosity lays the foundation of scientific progress. The quest for knowledge has always been a timeless endeavor. Scholars seek reasons to explain the phenomena they observe, paving way for development of research. Every investigation should offer clarity and a well-defined rationale in research is a cornerstone upon which the entire study can be built.

Research rationale is the heartbeat of every academic pursuit as it guides the researchers to unlock the untouched areas of their field. Additionally, it illuminates the gaps in the existing knowledge, and identifies the potential contributions that the study aims to make.

Table of Contents

What Is Research Rationale and When Is It Written

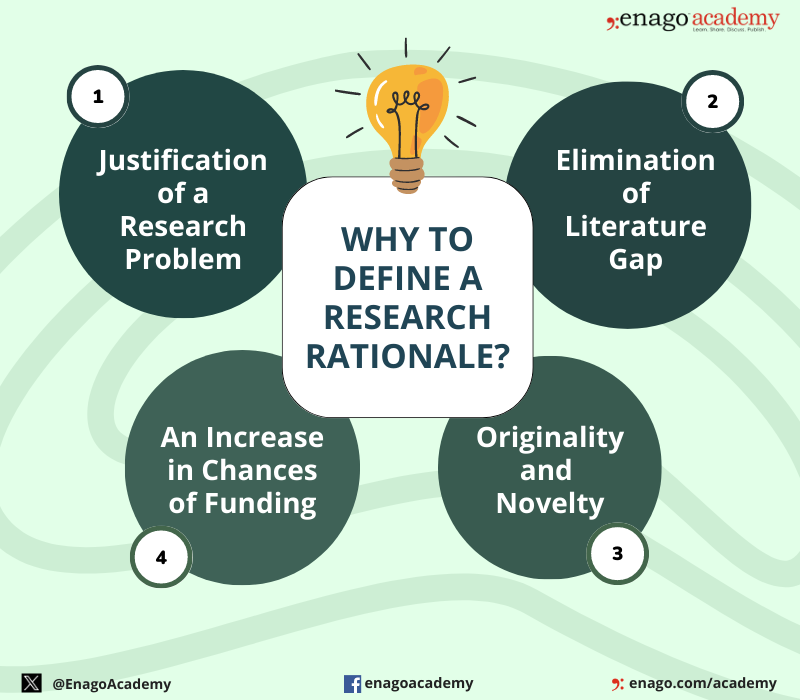

Research rationale is the “why” behind every academic research. It not only frames the study but also outlines its objectives , questions, and expected outcomes. Additionally, it helps to identify the potential limitations of the study . It serves as a lighthouse for researchers that guides through data collection and analysis, ensuring their efforts remain focused and purposeful. Typically, a rationale is written at the beginning of the research proposal or research paper . It is an essential component of the introduction section and provides the foundation for the entire study. Furthermore, it provides a clear understanding of the purpose and significance of the research to the readers before delving into the specific details of the study. In some cases, the rationale is written before the methodology, data analysis, and other sections. Also, it serves as the justification for the research, and how it contributes to the field. Defining a research rationale can help a researcher in following ways:

1. Justification of a Research Problem

- Research rationale helps to understand the essence of a research problem.

- It designs the right approach to solve a problem. This aspect is particularly important for applied research, where the outcomes can have real-world relevance and impact.

- Also, it explains why the study is worth conducting and why resources should be allocated to pursue it.

- Additionally, it guides a researcher to highlight the benefits and implications of a strategy.

2. Elimination of Literature Gap

- Research rationale helps to ideate new topics which are less addressed.

- Additionally, it offers fresh perspectives on existing research and discusses the shortcomings in previous studies.

- It shows that your study aims to contribute to filling these gaps and advancing the field’s understanding.

3. Originality and Novelty

- The rationale highlights the unique aspects of your research and how it differs from previous studies.

- Furthermore, it explains why your research adds something new to the field and how it expands upon existing knowledge.

- It highlights how your findings might contribute to a better understanding of a particular issue or problem and potentially lead to positive changes.

- Besides these benefits, it provides a personal motivation to the researchers. In some cases, researchers might have personal experiences or interests that drive their desire to investigate a particular topic.

4. An Increase in Chances of Funding

- It is essential to convince funding agencies , supervisors, or reviewers, that a research is worth pursuing.

- Therefore, a good rationale can get your research approved for funding and increases your chances of getting published in journals; as it addresses the potential knowledge gap in existing research.

Overall, research rationale is essential for providing a clear and convincing argument for the value and importance of your research study, setting the stage for the rest of the research proposal or manuscript. Furthermore, it helps establish the context for your work and enables others to understand the purpose and potential impact of your research.

5 Key Elements of a Research Rationale

Research rationale must include certain components which make it more impactful. Here are the key elements of a research rationale:

By incorporating these elements, you provide a strong and convincing case for the legitimacy of your research, which is essential for gaining support and approval from academic institutions, funding agencies, or other stakeholders.

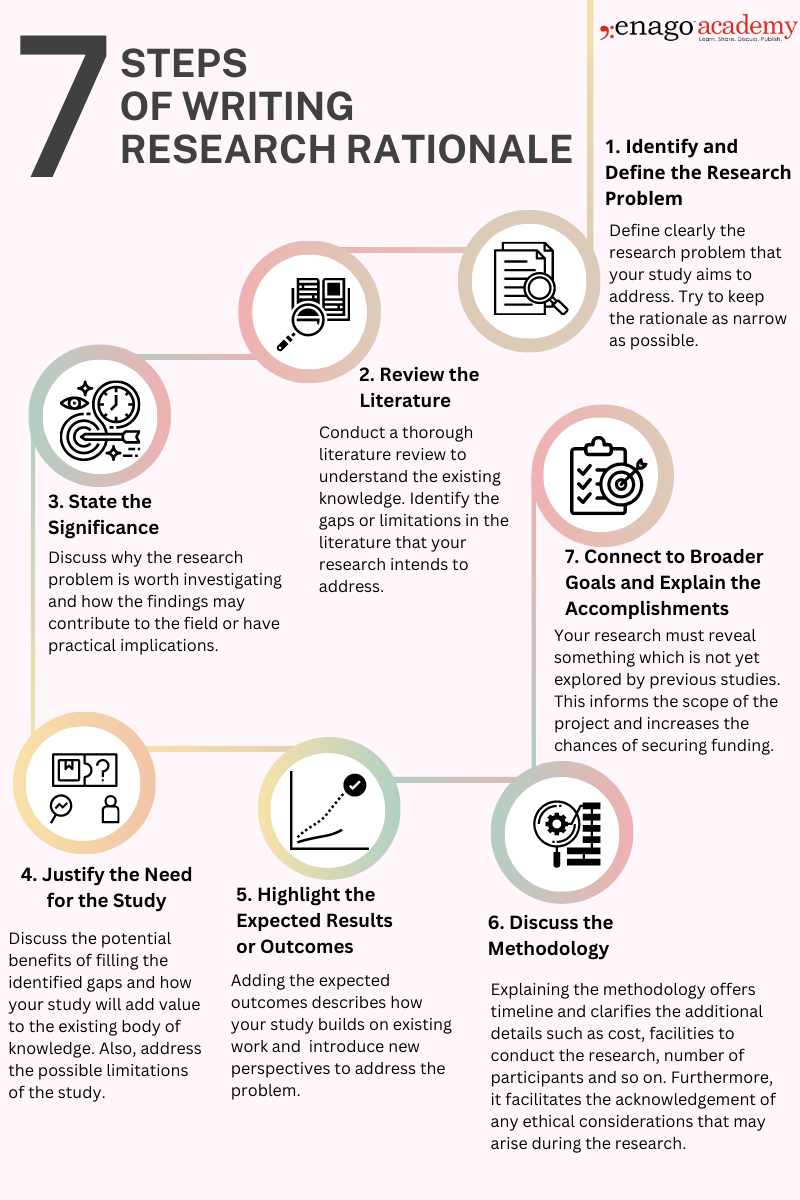

How to Write a Rationale in Research

Writing a rationale requires careful consideration of the reasons for conducting the study. It is usually written in the present tense.

Here are some steps to guide you through the process of writing a research rationale:

After writing the initial draft, it is essential to review and revise the research rationale to ensure that it effectively communicates the purpose of your research. The research rationale should be persuasive and compelling, convincing readers that your study is worthwhile and deserves their attention.

How Long Should a Research Rationale be?

Although there is no pre-defined length for a rationale in research, its length may vary depending on the specific requirements of the research project. It also depends on the academic institution or organization, and the guidelines set by the research advisor or funding agency. In general, a research rationale is usually a concise and focused document.

Typically, it ranges from a few paragraphs to a few pages, but it is usually recommended to keep it as crisp as possible while ensuring all the essential elements are adequately covered. The length of a research rationale can be roughly as follows:

1. For Research Proposal:

A. Around 1 to 3 pages

B. Ensure clear and comprehensive explanation of the research question, its significance, literature review , and methodological approach.

2. Thesis or Dissertation:

A. Around 3 to 5 pages

B. Ensure an extensive coverage of the literature review, theoretical framework, and research objectives to provide a robust justification for the study.

3. Journal Article:

A. Usually concise. Ranges from few paragraphs to one page

B. The research rationale is typically included as part of the introduction section

However, remember that the quality and content of the research rationale are more important than its length. The reasons for conducting the research should be well-structured, clear, and persuasive when presented. Always adhere to the specific institution or publication guidelines.

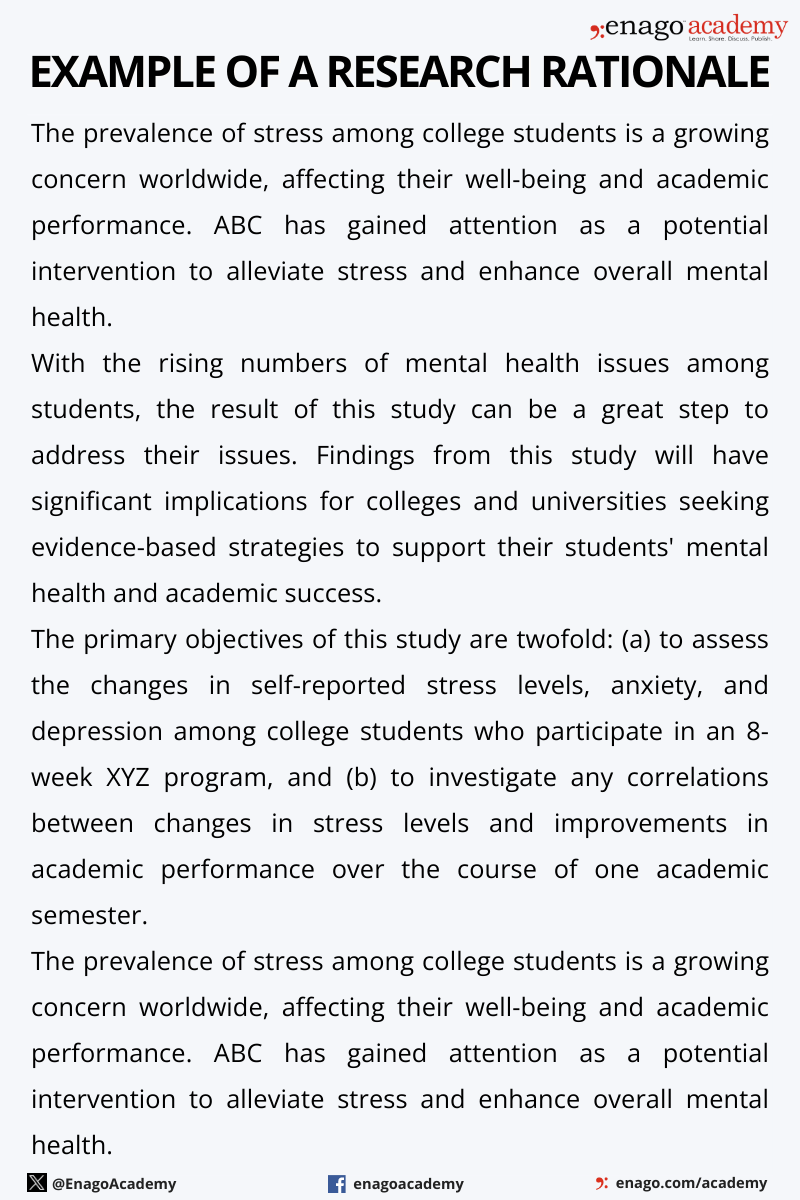

Example of a Research Rationale

In conclusion, the research rationale serves as the cornerstone of a well-designed and successful research project. It ensures that research efforts are focused, meaningful, and ethically sound. Additionally, it provides a comprehensive and logical justification for embarking on a specific investigation. Therefore, by identifying research gaps, defining clear objectives, emphasizing significance, explaining the chosen methodology, addressing ethical considerations, and recognizing potential limitations, researchers can lay the groundwork for impactful and valuable contributions to the scientific community.

So, are you ready to delve deeper into the world of research and hone your academic writing skills? Explore Enago Academy ‘s comprehensive resources and courses to elevate your research and make a lasting impact in your field. Also, share your thoughts and experiences in the form of an article or a thought piece on Enago Academy’s Open Platform .

Join us on a journey of scholarly excellence today!

Frequently Asked Questions

A rationale of the study can be written by including the following points: 1. Background of the Research/ Study 2. Identifying the Knowledge Gap 3. An Overview of the Goals and Objectives of the Study 4. Methodology and its Significance 5. Relevance of the Research

Start writing a research rationale by defining the research problem and discussing the literature gap associated with it.

A research rationale can be ended by discussing the expected results and summarizing the need of the study.

A rationale for thesis can be made by covering the following points: 1. Extensive coverage of the existing literature 2. Explaining the knowledge gap 3. Provide the framework and objectives of the study 4. Provide a robust justification for the study/ research 5. Highlight the potential of the research and the expected outcomes

A rationale for dissertation can be made by covering the following points: 1. Highlight the existing reference 2. Bridge the gap and establish the context of your research 3. Describe the problem and the objectives 4. Give an overview of the methodology

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

Science under Surveillance: Journals adopt advanced AI to uncover image manipulation

Journals are increasingly turning to cutting-edge AI tools to uncover deceitful images published in manuscripts.…

Mitigating Survivorship Bias in Scholarly Research: 10 tips to enhance data integrity

The Power of Proofreading: Taking your academic work to the next level

Facing Difficulty Writing an Academic Essay? — Here is your one-stop solution!

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

We use cookies on this site to enhance your experience

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

A link to reset your password has been sent to your email.

Back to login

We need additional information from you. Please complete your profile first before placing your order.

Thank you. payment completed., you will receive an email from us to confirm your registration, please click the link in the email to activate your account., there was error during payment, orcid profile found in public registry, download history, how to write the rationale for your research.

- Charlesworth Author Services

- 19 November, 2021

The rationale for one’s research is the justification for undertaking a given study. It states the reason(s) why a researcher chooses to focus on the topic in question, including what the significance is and what gaps the research intends to fill. In short, it is an explanation that rationalises the need for the study. The rationale is typically followed by a hypothesis/ research question (s) and the study objectives.

When is the rationale for research written?

The rationale of a study can be presented both before and after the research is conducted.

- Before : The rationale is a crucial part of your research proposal , representing the plan of your work as formulated before you execute your study.

- After : Once the study is completed, the rationale is presented in a research paper or dissertation to explain why you focused on the particular question. In this instance, you would link the rationale of your research project to the study aims and outcomes.

Basis for writing the research rationale

The study rationale is predominantly based on preliminary data . A literature review will help you identify gaps in the current knowledge base and also ensure that you avoid duplicating what has already been done. You can then formulate the justification for your study from the existing literature on the subject and the perceived outcomes of the proposed study.

Length of the research rationale

In a research proposal or research article, the rationale would not take up more than a few sentences . A thesis or dissertation would allow for a longer description, which could even run into a couple of paragraphs . The length might even depend on the field of study or nature of the experiment. For instance, a completely novel or unconventional approach might warrant a longer and more detailed justification.

Basic elements of the research rationale

Every research rationale should include some mention or discussion of the following:

- An overview of your conclusions from your literature review

- Gaps in current knowledge

- Inconclusive or controversial findings from previous studies

- The need to build on previous research (e.g. unanswered questions, the need to update concepts in light of new findings and/or new technical advancements).

Example of a research rationale

Note: This uses a fictional study.

Abc xyz is a newly identified microalgal species isolated from fish tanks. While Abc xyz algal blooms have been seen as a threat to pisciculture, some studies have hinted at their unusually high carotenoid content and unique carotenoid profile. Carotenoid profiling has been carried out only in a handful of microalgal species from this genus, and the search for microalgae rich in bioactive carotenoids has not yielded promising candidates so far. This in-depth examination of the carotenoid profile of Abc xyz will help identify and quantify novel and potentially useful carotenoids from an untapped aquaculture resource .

In conclusion

It is important to describe the rationale of your research in order to put the significance and novelty of your specific research project into perspective. Once you have successfully articulated the reason(s) for your research, you will have convinced readers of the importance of your work!

Maximise your publication success with Charlesworth Author Services.

Charlesworth Author Services , a trusted brand supporting the world’s leading academic publishers, institutions and authors since 1928.

To know more about our services, visit: Our Services

Share with your colleagues

Related articles.

How to identify Gaps in research and determine your original research topic

Charlesworth Author Services 14/09/2021 00:00:00

Tips for designing your Research Question

Charlesworth Author Services 01/08/2017 00:00:00

Why and How to do a literature search

Charlesworth Author Services 17/08/2020 00:00:00

Related webinars

Bitesize Webinar: How to write and structure your academic article for publication - Module 1: Know when are you ready to write

Charlesworth Author Services 04/03/2021 00:00:00

Bitesize Webinar: How to write and structure your academic article for publication- Module 3: Understand the structure of an academic paper

Bitesize Webinar: How to write and structure your academic article for publication: Module 4: Prepare to write your academic paper

Bitesize Webinar: How to write and structure your academic article for publication: Module 5: Conduct a Literature Review

Article sections.

How to write an Introduction to an academic article

Writing a strong Methods section

Charlesworth Author Services 12/03/2021 00:00:00

Strategies for writing the Results section in a scientific paper

Charlesworth Author Services 27/10/2021 00:00:00

How to Write a Rationale: A Guide for Research and Beyond

Ever found yourself scratching your head, wondering how to justify your choice of a research topic or project? You’re not alone! Writing a rationale, which essentially means explaining the ‘why’ behind your decisions, is crucial to any research process. It’s like the secret sauce that adds flavour to your research recipe. So, the only thing you need to know is how to write a rationale.

What is a Rationale?

A rationale in research is essentially the foundation of your study. It serves as the justification for undertaking a particular research project. At its core, the rationale explains why the research was conducted or needs to be conducted, thus addressing a specific knowledge gap or research question.

Here’s a breakdown of the key elements involved in crafting a rationale:

Linking Background to Research Question:

The rationale should connect the background of the study to your specific research question. It involves presenting and discussing existing data on your topic, identifying gaps or issues in the current understanding, and explaining why addressing them is important.

Objectives and Significance:

Your rationale should clearly outline your research objectives – what you hope to discover or achieve through the study. It should also emphasize the subject’s significance in your field and explain why more or better research is needed.

Methodological Approach:

The rationale should briefly describe your proposed research method , whether qualitative (descriptive) or quantitative (experimental), and justify this choice.

Justifying the Need for Research:

The rationale isn’t just about what you’re doing and why it’s necessary. It can involve highlighting methodological, contextual, or conceptual limitations in previous studies and explaining how your research aims to overcome these limitations. Essentially, you’re making a case for why your research fills a crucial gap in existing knowledge.

Presenting Before and After Research:

Interestingly, the rationale can be presented before and after the research. Before the research, it forms a central part of the research proposal, setting out the plan for the work. After the research, it’s presented in a research article or dissertation to explain the focus on a specific research question and link it to the study’s aims and outcomes.

Elements to Include:

A good rationale should include a summary of conclusions from your literature review, identify what is currently unknown, discuss inconclusive or contested results from previous studies, and emphasize the necessity to improve or build on previous research.

Creating a rationale is a vital part of the research process, as it not only sets the stage for your study but also convinces readers of the value and necessity of your work.

How to Write a Rationale:

Writing a rationale for your research is crucial in conducting and presenting your study. It involves explaining why your research is necessary and important. Here’s a guide to help you craft a compelling rationale:

Identify the Problem or Knowledge Gap:

Begin by clearly stating the issue or gap in knowledge that your research aims to address. Explain why this problem is important and merits investigation. It is the foundation of your rationale and sets the stage for the need for your research.

Review the Literature:

Conduct a thorough review of existing literature on your topic. It helps you understand what research has already been done and what gaps or open questions exist. Your rationale should build on this background by highlighting these gaps and emphasizing the importance of addressing them.

Define Your Research Questions/Hypotheses:

Based on your understanding of the problem and literature review, clearly state the research questions or hypotheses that your study aims to explore. These should logically stem from the identified gaps or issues.

Explain Your Research Approach:

Describe the methods you will use for your research, including data collection and analysis techniques. Justify why these methods are appropriate for addressing your research questions or hypotheses.

Discuss the Potential Impact of Your Research: Explain the significance of your study. Consider both theoretical contributions and practical implications. For instance, how does your research advance existing knowledge? Does it have real-world applications? Is it relevant to a specific field or community?

Consider Ethical Considerations:

If your research involves human or animal subjects, discuss the ethical aspects and how you plan to conduct your study responsibly.

Contextualise Your Study:

Justify the relevance of your research by explaining how it fits into the broader context. Connect your study to current trends, societal needs, or academic discussions.

Support with Evidence:

Provide evidence or examples that underscore the need for your research. It could include citing relevant studies, statistics, or scenarios that illustrate the problem or gap your research addresses.

Methodological, Contextual, and Conceptual Limitations:

Address any limitations of previous research and how your study aims to overcome them. It can include methodological flaws in previous studies, changes in external factors that make past research less relevant, or the need to study a phenomenon within a new conceptual framework.

Placement in Your Paper:

Typically, the rationale is written toward the end of the introduction section of your paper, providing a logical lead-in to your research questions and methodology.

By following these steps and considering your audience’s perspective, you can write a strong and compelling rationale that clearly communicates the significance and necessity of your research project.

Frequently Asked Questions:

What makes a good research rationale.

A good rationale clearly identifies a gap in existing knowledge, builds on previous research, and outlines why your study is necessary and significant.

How detailed should my literature review be in the rationale?

Your literature review should be comprehensive enough to highlight the gaps your research aims to fill, but it should not overshadow the rationale itself.

Conclusion:

A well-crafted rationale is your ticket to making your research stand out. It’s about bridging gaps, challenging norms, and paving the way for new discoveries. So go ahead, make your rationale the cornerstone of your research narrative!

Award-Winning Results

Team of 11+ experts, 10,000+ page #1 rankings on google, dedicated to smbs, $175,000,000 in reported client revenue.

Up until working with Casey, we had only had poor to mediocre experiences outsourcing work to agencies. Casey & the team at CJ&CO are the exception to the rule.

Communication was beyond great, his understanding of our vision was phenomenal, and instead of needing babysitting like the other agencies we worked with, he was not only completely dependable but also gave us sound suggestions on how to get better results, at the risk of us not needing him for the initial job we requested (absolute gem).

This has truly been the first time we worked with someone outside of our business that quickly grasped our vision, and that I could completely forget about and would still deliver above expectations.

I honestly can't wait to work in many more projects together!

Related Articles

View All Post

Conversion Rate Optimization , Copywriting , Customer Experience

How to Tap Into What Your Customers Love & Hate

Casey Jones

Advertising , Copywriting

What does a Copywriter do at an Ad Agency: Things You Should Know if You’re a Copywriter

Copywriting

How to Write a Marketing Script: Take Your Marketing to the Next Level in 2023

*The information this blog provides is for general informational purposes only and is not intended as financial or professional advice. The information may not reflect current developments and may be changed or updated without notice. Any opinions expressed on this blog are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the author’s employer or any other organization. You should not act or rely on any information contained in this blog without first seeking the advice of a professional. No representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this blog. The author and affiliated parties assume no liability for any errors or omissions.

Think of yourself as a member of a jury, listening to a lawyer who is presenting an opening argument. You'll want to know very soon whether the lawyer believes the accused to be guilty or not guilty, and how the lawyer plans to convince you. Readers of academic essays are like jury members: before they have read too far, they want to know what the essay argues as well as how the writer plans to make the argument. After reading your thesis statement, the reader should think, "This essay is going to try to convince me of something. I'm not convinced yet, but I'm interested to see how I might be."

An effective thesis cannot be answered with a simple "yes" or "no." A thesis is not a topic; nor is it a fact; nor is it an opinion. "Reasons for the fall of communism" is a topic. "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" is a fact known by educated people. "The fall of communism is the best thing that ever happened in Europe" is an opinion. (Superlatives like "the best" almost always lead to trouble. It's impossible to weigh every "thing" that ever happened in Europe. And what about the fall of Hitler? Couldn't that be "the best thing"?)

A good thesis has two parts. It should tell what you plan to argue, and it should "telegraph" how you plan to argue—that is, what particular support for your claim is going where in your essay.

Steps in Constructing a Thesis

First, analyze your primary sources. Look for tension, interest, ambiguity, controversy, and/or complication. Does the author contradict himself or herself? Is a point made and later reversed? What are the deeper implications of the author's argument? Figuring out the why to one or more of these questions, or to related questions, will put you on the path to developing a working thesis. (Without the why, you probably have only come up with an observation—that there are, for instance, many different metaphors in such-and-such a poem—which is not a thesis.)

Once you have a working thesis, write it down. There is nothing as frustrating as hitting on a great idea for a thesis, then forgetting it when you lose concentration. And by writing down your thesis you will be forced to think of it clearly, logically, and concisely. You probably will not be able to write out a final-draft version of your thesis the first time you try, but you'll get yourself on the right track by writing down what you have.

Keep your thesis prominent in your introduction. A good, standard place for your thesis statement is at the end of an introductory paragraph, especially in shorter (5-15 page) essays. Readers are used to finding theses there, so they automatically pay more attention when they read the last sentence of your introduction. Although this is not required in all academic essays, it is a good rule of thumb.

Anticipate the counterarguments. Once you have a working thesis, you should think about what might be said against it. This will help you to refine your thesis, and it will also make you think of the arguments that you'll need to refute later on in your essay. (Every argument has a counterargument. If yours doesn't, then it's not an argument—it may be a fact, or an opinion, but it is not an argument.)

This statement is on its way to being a thesis. However, it is too easy to imagine possible counterarguments. For example, a political observer might believe that Dukakis lost because he suffered from a "soft-on-crime" image. If you complicate your thesis by anticipating the counterargument, you'll strengthen your argument, as shown in the sentence below.

Some Caveats and Some Examples

A thesis is never a question. Readers of academic essays expect to have questions discussed, explored, or even answered. A question ("Why did communism collapse in Eastern Europe?") is not an argument, and without an argument, a thesis is dead in the water.

A thesis is never a list. "For political, economic, social and cultural reasons, communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" does a good job of "telegraphing" the reader what to expect in the essay—a section about political reasons, a section about economic reasons, a section about social reasons, and a section about cultural reasons. However, political, economic, social and cultural reasons are pretty much the only possible reasons why communism could collapse. This sentence lacks tension and doesn't advance an argument. Everyone knows that politics, economics, and culture are important.

A thesis should never be vague, combative or confrontational. An ineffective thesis would be, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because communism is evil." This is hard to argue (evil from whose perspective? what does evil mean?) and it is likely to mark you as moralistic and judgmental rather than rational and thorough. It also may spark a defensive reaction from readers sympathetic to communism. If readers strongly disagree with you right off the bat, they may stop reading.

An effective thesis has a definable, arguable claim. "While cultural forces contributed to the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, the disintegration of economies played the key role in driving its decline" is an effective thesis sentence that "telegraphs," so that the reader expects the essay to have a section about cultural forces and another about the disintegration of economies. This thesis makes a definite, arguable claim: that the disintegration of economies played a more important role than cultural forces in defeating communism in Eastern Europe. The reader would react to this statement by thinking, "Perhaps what the author says is true, but I am not convinced. I want to read further to see how the author argues this claim."

A thesis should be as clear and specific as possible. Avoid overused, general terms and abstractions. For example, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because of the ruling elite's inability to address the economic concerns of the people" is more powerful than "Communism collapsed due to societal discontent."

Copyright 1999, Maxine Rodburg and The Tutors of the Writing Center at Harvard University

Rationale for the Study

It is important for you to be able to explain the importance of the research you are conducting by providing valid arguments. Rationale for the study, also referred to as justification for the study, is reason why you have conducted your study in the first place. This part in your paper needs to explain uniqueness and importance of your research. Rationale for the study needs to be specific and ideally, it should relate to the following points:

1. The research needs to contribute to the elimination of a gap in the literature. Elimination of gap in the present literature is one of the compulsory requirements for your study. In other words, you don’t need to ‘re-invent the wheel’ and your research aims and objectives need to focus on new topics. For example, you can choose to conduct an empirical study to assess the implications of COVID-19 pandemic on the numbers of tourists visitors in your city. This might be previously undressed topic, taking into account that COVID-19 pandemic is a relatively recent phenomenon.

Alternatively, if you cannot find a new topic to research, you can attempt to offer fresh perspectives on existing management, business or economic issues. For example, while thousands of studies have been previously conducted to study various aspects of leadership, this topic as far from being exhausted as a research area. Specifically, new studies can be conducted in the area of leadership to analyze the impacts of new communication mediums such as TikTok, and other social networking sites on leadership practices.

You can also discuss the shortcomings of previous works devoted to your research area. Shortcomings in previous studies can be divided into three groups:

a) Methodological limitations . Methodology employed in previous study may be flawed in terms of research design, research approach or sampling.

b) Contextual limitations . Relevance of previous works may be non-existent for the present because external factors have changed.

c) Conceptual limitations . Previous studies may be unjustifiably bound up to a particular model or an ideology.

While discussing the shortcomings of previous studies you should explain how you are going to correct them. This principle is true to almost all areas in business studies i.e. gaps or shortcomings in the literature can be found in relation to almost all areas of business and economics.

2. The research can be conducted to solve a specific problem. It helps if you can explain why you are the right person and in the right position to solve the problem. You have to explain the essence of the problem in a detailed manner and highlight practical benefits associated with the solution of the problem. Suppose, your dissertation topic is “a study into advantages and disadvantages of various entry strategies into Chinese market”. In this case, you can say that practical implications of your research relates to assisting businesses aiming to enter Chinese market to do more informed decision making.

Alternatively, if your research is devoted to the analysis of impacts of CSR programs and initiatives on brand image, practical contributions of your study would relate to contributing to the level of effectiveness of CSR programs of businesses.

Additional examples of studies that can assist to address specific practical problems may include the following:

- A study into the reasons of high employee turnover at Hanson Brick

- A critical analysis of employee motivation problems at Esporta, Finchley Road, London

- A research into effective succession planning at Microsoft

- A study into major differences between private and public primary education in the USA and implications of these differences on the quality of education

However, it is important to note that it is not an obligatory for a dissertation to be associated with the solution of a specific problem. Dissertations can be purely theory-based as well. Examples of such studies include the following:

- Born or bred: revising The Great Man theory of leadership in the 21 st century

- A critical analysis of the relevance of McClelland’s Achievement theory to the US information technology industry

- Neoliberalism as a major reason behind the emergence of the global financial and economic crisis of 2007-2009

- Analysis of Lewin’s Model of Change and its relevance to pharmaceutical sector of France

3. Your study has to contribute to the level of professional development of the researcher . That is you. You have to explain in a detailed manner in what ways your research contributes to the achievement of your long-term career aspirations.

For example, you have selected a research topic of “ A critical analysis of the relevance of McClelland’s Achievement theory in the US information technology industry ”. You may state that you associate your career aspirations with becoming an IT executive in the US, and accordingly, in-depth knowledge of employee motivation in this industry is going to contribute your chances of success in your chosen career path.

Therefore, you are in a better position if you have already identified your career objectives, so that during the research process you can get detailed knowledge about various aspects of your chosen industry.

My e-book, The Ultimate Guide to Writing a Dissertation in Business Studies: a step by step assistance offers practical assistance to complete a dissertation with minimum or no stress. The e-book covers all stages of writing a dissertation starting from the selection to the research area to submitting the completed version of the work within the deadline.

John Dudovskiy

Independent Study – Skills Guide

- Formulating the Research Question

Introduction and Rationale of the Study

- Literature Review

- Research Methodology

- Research Design

- Ethical Considerations

- Data Findings

- Data Analysis

- Conclusions

Introduction and rationale of the study

This should briefly outline your area of interest and what has led you to research your chosen area. The rationale section of the dissertation describes why a particular concept, concern or problem is important within the field you are researching.

A well-constructed rationale demonstrates that you understand your chosen field of research, the competing perspectives that exist, and what you hope to gain by carrying out the research.

At undergraduate level you will be illuminating your understanding and should be aware that whilst the research you undertake can make a positive contribution to the field (on a small scale) you will not be making a new contribution to knowledge which will improve an entire profession.

A message from a former student:

"Your Independent Study research is a tremendous opportunity to pursue and discover new knowledge in the field of education. For me, producing a research project was so intellectually liberating, I was encouraged to be critical, critical , critical - and once you become an employee in any educational institution it all changes - you will never get that level of academic freedom again!"

- Introduction and rationale example 1

- Introduction and rationale example 2

- << Previous: Formulating the Research Question

- Next: Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Sep 9, 2022 9:55 AM

- URL: https://libguides.derby.ac.uk/independent

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Write a Study Rationale

Last Updated: May 19, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Jake Adams and by wikiHow staff writer, Jennifer Mueller, JD . Jake Adams is an academic tutor and the owner of Simplifi EDU, a Santa Monica, California based online tutoring business offering learning resources and online tutors for academic subjects K-College, SAT & ACT prep, and college admissions applications. With over 14 years of professional tutoring experience, Jake is dedicated to providing his clients the very best online tutoring experience and access to a network of excellent undergraduate and graduate-level tutors from top colleges all over the nation. Jake holds a BS in International Business and Marketing from Pepperdine University. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 54,310 times.

A study rationale explains the reason for a study and the importance of its findings for a particular field. Commonly, you'll need to write a study rationale as part of a university course of study, although you may also need to write one as a professional researcher to apply for funding or other support. As a student, your study rationale also justifies how it fulfills the requirements for your degree program or course of study. Do research before you write your study rationale so that you can discuss the previous work your study builds on and explain its significance to your field. Thorough research is also important in the professional context because your rationale will likely become part of the contract if funding or support is approved. [1] X Research source

Describing What You Hope to Accomplish

- For example, suppose you want to study how working the night shift affects the academic performance of college students who are taking classes during the day. A narrow question would measure a specific impact based on a specific amount of hours worked.

- Justify the methodology you're using. If there's another methodology that might accomplish the same result, describe it and explain why your methodology is superior — perhaps because it's more efficient, takes less time, or uses fewer resources. For example, you might get more information out of personal interviews, but creating an online questionnaire is more cost-effective.

- Particularly if you're seeking funding or support, this section of your rationale will also include details about the cost of your study and the facilities or resources you'll need. [3] X Research source

Tip: A methodology that is more complex, difficult, or expensive requires more justification than one that is straightforward and simple.

- For example, if you're studying the effect of working the night shift on academic performance, you might hypothesize that working 4 or more nights a week lowers students' grade point averages by more than 1 point.

- Use action words, such as "quantify" or "establish," when writing your goals. For example, you might write that one goal of your study is to "quantify the degree to which working at night inhibits the academic performance of college students."

- If you are a professional researcher, your objectives may need to be more specific and concrete. The organization you submit your rationale to will have details about the requirements to apply for funding and other support. [5] X Research source

Explaining Your Study's Significance

- Going into extensive detail usually isn't necessary. Instead, highlight the findings of the most significant work in the field that addressed a similar question.

- Provide references so that your readers can examine the previous studies for themselves and compare them to your proposed study.

- Methodological limitations: Previous studies failed to measure the variables appropriately or used a research design that had problems or biases

- Contextual limitations: Previous studies aren't relevant because circumstances have changed regarding the variables measured

- Conceptual limitations: Previous studies are too tied up in a specific ideology or framework

- For example, if a previous study had been conducted to support a university's policy that full-time students were not permitted to work, you might argue that it was too tied up in that specific ideology and that this biased the results. You could then point out that your study is not intended to advance any particular policy.

Tip: If you have to defend or present your rationale to an advisor or team, try to anticipate the questions they might ask you and include the answers to as many of those questions as possible.

Including Academic Proposal Information

- As a student, you might emphasize your major and specific classes you've taken that give you particular knowledge about the subject of your study. If you've served as a research assistant on a study with a similar methodology or covering a similar research question, you might mention that as well.

- If you're a professional researcher, focus on the experience you have in a particular field as well as the studies you've done in the past. If you have done studies with a similar methodology that were important in your field, you might mention those as well.

Tip: If you don't have any particular credentials or experience that are relevant to your study, tell the readers of your rationale what drew you to this particular topic and how you became interested in it.

- For example, if you are planning to conduct the study as fulfillment of the research requirement for your degree program, you might discuss any specific guidelines for that research requirement and list how your study meets those criteria.

- In most programs, there will be specific wording for you to include in your rationale if you're submitting it for a certain number of credits. Your instructor or advisor can help make sure you've worded this appropriately.

Study Rationale Outline and Example

Expert Q&A

- This article presents an overview of how to write a study rationale. Check with your instructor or advisor for any specific requirements that apply to your particular project. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://research.com/research/how-to-write-research-methodology

- ↑ https://ris.leeds.ac.uk/applying-for-funding/developing-your-proposal/resources-and-tips/key-questions-for-researchers/

- ↑ https://www.cwauthors.com/article/how-to-write-the-rationale-for-your-research

- ↑ http://www.writingcentre.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/167/Rationale.pdf

- ↑ https://www.niaid.nih.gov/grants-contracts/write-research-plan

- ↑ https://www.esc.edu/degree-planning-academic-review/degree-program/student-degree-planning-guide/rationale-essay-writing/writing-tips/

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Did this article help you?

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples

How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples

Published on January 11, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on August 15, 2023 by Eoghan Ryan.

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . It usually comes near the end of your introduction .

Your thesis will look a bit different depending on the type of essay you’re writing. But the thesis statement should always clearly state the main idea you want to get across. Everything else in your essay should relate back to this idea.

You can write your thesis statement by following four simple steps:

- Start with a question

- Write your initial answer

- Develop your answer

- Refine your thesis statement

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is a thesis statement, placement of the thesis statement, step 1: start with a question, step 2: write your initial answer, step 3: develop your answer, step 4: refine your thesis statement, types of thesis statements, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about thesis statements.

A thesis statement summarizes the central points of your essay. It is a signpost telling the reader what the essay will argue and why.

The best thesis statements are:

- Concise: A good thesis statement is short and sweet—don’t use more words than necessary. State your point clearly and directly in one or two sentences.

- Contentious: Your thesis shouldn’t be a simple statement of fact that everyone already knows. A good thesis statement is a claim that requires further evidence or analysis to back it up.

- Coherent: Everything mentioned in your thesis statement must be supported and explained in the rest of your paper.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

The thesis statement generally appears at the end of your essay introduction or research paper introduction .

The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education. The use of the internet in academic contexts and among young people more generally is hotly debated. For many who did not grow up with this technology, its effects seem alarming and potentially harmful. This concern, while understandable, is misguided. The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its many benefits for education: the internet facilitates easier access to information, exposure to different perspectives, and a flexible learning environment for both students and teachers.

You should come up with an initial thesis, sometimes called a working thesis , early in the writing process . As soon as you’ve decided on your essay topic , you need to work out what you want to say about it—a clear thesis will give your essay direction and structure.

You might already have a question in your assignment, but if not, try to come up with your own. What would you like to find out or decide about your topic?

For example, you might ask:

After some initial research, you can formulate a tentative answer to this question. At this stage it can be simple, and it should guide the research process and writing process .

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Now you need to consider why this is your answer and how you will convince your reader to agree with you. As you read more about your topic and begin writing, your answer should get more detailed.

In your essay about the internet and education, the thesis states your position and sketches out the key arguments you’ll use to support it.

The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its many benefits for education because it facilitates easier access to information.

In your essay about braille, the thesis statement summarizes the key historical development that you’ll explain.

The invention of braille in the 19th century transformed the lives of blind people, allowing them to participate more actively in public life.

A strong thesis statement should tell the reader:

- Why you hold this position

- What they’ll learn from your essay

- The key points of your argument or narrative

The final thesis statement doesn’t just state your position, but summarizes your overall argument or the entire topic you’re going to explain. To strengthen a weak thesis statement, it can help to consider the broader context of your topic.

These examples are more specific and show that you’ll explore your topic in depth.

Your thesis statement should match the goals of your essay, which vary depending on the type of essay you’re writing:

- In an argumentative essay , your thesis statement should take a strong position. Your aim in the essay is to convince your reader of this thesis based on evidence and logical reasoning.

- In an expository essay , you’ll aim to explain the facts of a topic or process. Your thesis statement doesn’t have to include a strong opinion in this case, but it should clearly state the central point you want to make, and mention the key elements you’ll explain.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . Everything else you write should relate to this key idea.

The thesis statement is essential in any academic essay or research paper for two main reasons:

- It gives your writing direction and focus.