Afghanistan

Afghanistan is located in Central Asia with Iran to the west and Pakistan to the east.

Afghanistan is located in Central Asia with Iran to the west and Pakistan to the east. Tall, forbidding mountains and dry deserts cover most of the landscape of Afghanistan. The jagged mountain peaks are treacherous, and are snow covered for most of the year.

Many Afghans live in the fertile valleys between the mountains and grow their crops and tend to their animals. Only 20 percent of the land is used as fields.

Summers are hot and dry but the winters are very cold, especially north of the Hindu Kush, which is located in the eastern part of the country near Pakistan and Tajikistan. Many rivers flow through the mountain gorges. Snow melt and rain that flow out of the Hindu Kush pool into a low area and never reach the ocean.

The mountain passes in Afghanistan allow travelers passage across Asia. The country was a busy section of the Silk Road, a route that merchants have traveled over land between China , India , and Europe for over 2,000 years.

Map created by National Geographic Maps

PEOPLE & CULTURE

The country is made of many different groups. About 15 million people, nearly half of Afghanistan's population are Pashtuns and live in the south around Kandahar. They are descendants of people who came to the country 3,200 years ago.

Many other groups live in the country as well—Pashtuns are related to the Persian people of Iran, the Tajiks are also Persian, but speak another language called Dari, and the Uzbeks speak a language similar to Turkish.

The Hazaras live in the mountains of central Afghanistan and are believed to be descendents of the Mongols because their Dari language contains many Mongol words.

Due to many years of war, the countryside is littered with unexploded mines and children who herd animals are often killed by stepping on mines. Many schools have been destroyed, but children, including girls, go to school in ruins or wherever possible.

Over the centuries, travelers have braved the dangerous high mountain passes to find shelter in the valleys and plains of Afghanistan. Today nomads called Kuchi lead their herds of animals across the country and into the mountain pastures for grazing.

Afghans take pride in making and flying their own kites. They even have kite fights and use wire or glass in their kites to cut the kite strings of rival kite flyers.

Tea is the favorite Afghan drink and a popular meal is palau, made from rice, sheep and goat meats, and fruit.

Decades of war, hunting, and years of drought have reduced the wildlife population in Afghanistan. Tigers used to roam the hills, but they are now extinct. Bears and wolves have been hunted nearly to extinction.

Endangered snow leopards live in the cold Hindu Kush, but rely on their thick fur to stay warm. Hunters sell the soft leopard skins in the markets in the capital Kabul. The rhesus macaque and the red flying squirrel are found in the warmer southern areas of the country.

The country is rich in the vibrant blue stone, lapis lazuli, which was used to decorate the tomb of the Egyptian king Tutankhamun .

Until very recently, Afghanistan was considered a newly formed democracy. However in mid-August 2021, the Taliban—a religious and political group that ruled the country from the mid-1990s until 2001—took control of the country's major cities and regained power. (Taliban means “students” in Pashto, one of the languages spoken in Afghanistan.)

Afghanistan was settled around 7000 B.C. and has been in transition for most of its history. Alexander the Great conquered Afghanistan in 330 B.C. and brought the Greek language and culture to the region. Genghis Khan's Mongols invaded in the 13th century. In 1747, Pashtun elders held a council meeting called a Loya Jirga and created the kingdom of the Afghans.

The British and Afghans fought in three wars in the 19th and 20th centuries, but the Afghans finally defeated the British in 1919 and formed an independent monarchy in 1921.

In 1978, the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) seized power in the country, setting in motion a series of events that would turn the poor, mostly peaceful country into a breeding ground for terrorism. The PDPA’s occupation of Afghanistan eventually led to civil war, or a war between citizens of the same country.

Afghan fighters called the mujahedin fought against the PDPA; these rebels later received aid from the United States , Pakistan, China , and Iran . The Soviet Union, now called Russia , supported the PDPA regime. Soviet forces invaded Afghanistan in 1979 and remained in the country until 1989. Civil war continued in Afghanistan after the Soviet departure until the fall of the PDPA regime in 1992.

After the PDPA’s fall, various groups fought to gain control of the country. The Taliban emerged in 1994 and quickly began to take over cities across Afghanistan, with military support from Pakistan. During the Taliban's rule, the group was condemned by the international community for murdering innocent Afghan civilians and denying food supplies to starving citizens.

In 2001, following the terrorist attacks in the United States on September 11 of that year, the U.S. government demanded that the Taliban hand over Osama bin Laden, the leader of a terrorist group called al Qaeda, which was based in Afghanistan. The Taliban refused. The United States and its allies then took military action in Afghanistan and drove the Taliban from power in December 2001.

Both the Taliban and al Qaeda fled Afghanistan and relocated to nearby Pakistan, where they set up political and military outposts. Meanwhile, in Afghanistan, the United States and its allies worked with Afghans to set up schools, hospitals, and public facilities following the Taliban’s departure. Thousands of girls—who were banned from being educated under Taliban rule—went to school for the first time. Women were free to get jobs and take part in government activities, both of which were forbidden under the Taliban.

In 2004, Afghanistan adopted its current constitution and became an internationally recognized government, electing Hamid Karzai as its first president. Under its constitution, the president and two vice presidents are elected every five years. But the government struggled to extend its authority beyond the capital city of Kabul because the Taliban forces continued to try to regain control of the country.

In 2020, the Taliban and the Afghan government began to discuss a peace treaty, and though some people were concerned that the talks wouldn't progress, U.S. president Donald Trump planned to remove U.S. troops from the country by May 2021. His successor, Joe Biden , extended the date for the withdrawal to August 31 of that year. After nearly 20 years of U.S. occupation in Afghanistan, the United States’ longest war was going to end.

But the people who were concerned about the peace treaty talks stalling were right: Following Biden’s official announcement in July and the start of the withdrawal of international troops, the Taliban quickly took over multiple cities by force and brought back their extreme practices. By August 15, 2021, the Taliban had taken control of all major cities, including the capital of Kabul. President Ashraf Ghani fled the country, and the Afghan government all but collapsed.

The United States sent military troops to the country to help the American diplomats and support staff at the U.S. embassy in Kabul evacuate safely.

Watch "Destination World"

North america, south america, more to explore, u.s. states and territories facts and photos, destination world.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your California Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell My Info

- National Geographic

- National Geographic Education

- Shop Nat Geo

- Customer Service

- Manage Your Subscription

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Afghanistan 20/20: The 20-Year War in 20 Documents

Primary sources contradict Pentagon optimism over decades

Pakistan sanctuaries, Afghan corruption enabled Taliban resurgence

Bush nation-building, Obama surge, Trump deal all failed

Washington, D.C., August 19, 2021 – The U.S. government under four presidents misled the American people for nearly two decades about progress in Afghanistan, while hiding the inconvenient facts about ongoing failures inside confidential channels, according to declassified documents published today by the National Security Archive. The documents include highest-level “snowflake” memos written by then Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld during the George W. Bush administration, critical cables written by U.S. ambassadors back to Washington under both Bush and Barack Obama, the deeply flawed Pentagon strategy document behind Obama’s “surge” in 2009, and multiple “lessons learned” findings by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) – lessons that were never learned.

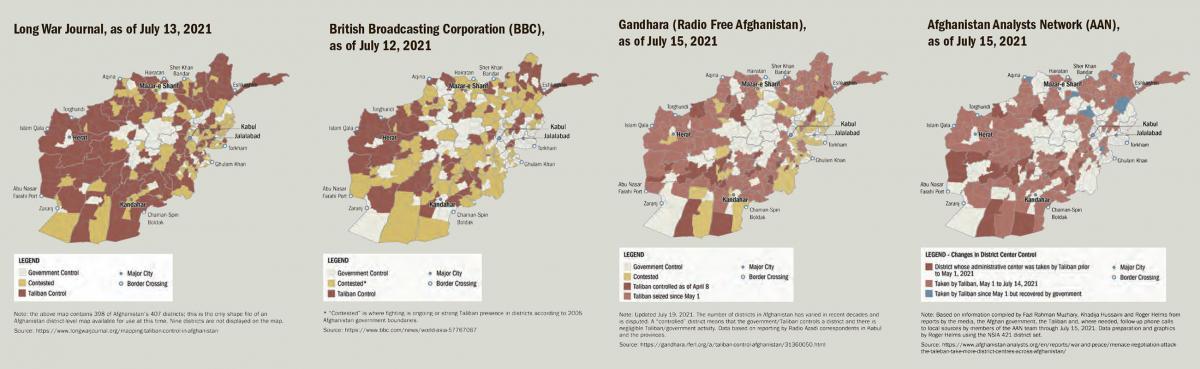

Estimates of Taliban controlled districts in Afghanistan as of mid-July 2021 ranged as high as more than half, according to the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, Quarterly Report, July 31, 2021, p. 55. The number had increased from 73 in April to 221 in July, a harbinger of the August takeover in Kabul.

The recent SIGAR report to Congress, from July 31, 2021, just as multiple provincial centers were falling to the Taliban, quotes repeated assurances from top U.S. generals (David Petraeus in 2011, John Campbell in 2015, John Nicholson in 2017, and Pentagon press secretary John Kirby in 2021) about the “increasingly capable” Afghan security forces. The SIGAR ends that section with the warning: “More than $88 billion has been appropriated to support Afghanistan’s security sector. The question of whether that money was well spent will ultimately be answered by the outcome of the fighting on the ground, perhaps the purest M&E [monitoring and evaluation] exercise.” Results are now in with the total collapse of the Afghan government and a looming humanitarian crisis. The documents detail ongoing problems that bedeviled the American war in Afghanistan from the beginning: lack of “visibility into who the bad guys are;” Pakistan’s double game of taking U.S. aid while providing a sanctuary to the Taliban; “mission creep” as a counterterror effort against al-Qaeda morphed into a nation-building war against the Taliban; Washington’s attention deficit disorder as the Bush administration pivoted to invading and occupying Iraq; endemic corruption driven in large part by American billions and secret intelligence payments to warlords; fake statistics and gassy metrics not only by the military but also the State Department, US AID, and their many contractors; the mismatch between Afghan realities and American designs for a new centralized government and modernized army; and more.

Read the Documents

Digital National Security Archive, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit

This is the foundational document for the first phase of U.S. strategy in Afghanistan, approved by the National Security Council on October 16, 2001 (just five weeks after the 9/11 attacks). This copy carries Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld’s personal handwritten edits, with an October 30 cover note to his top policy aide Douglas Feith about crafting a new updated version, emphasizing that "The U.S. should not commit to any post-Taliban military involvement since the U.S. will be heavily engaged in the anti-terrorism effort worldwide." The follow-on peacekeeping force in Afghanistan “could be UN-based or an ad hoc collection of volunteer states … but not the U.S.” Rumsfeld adds the word “military” as in “not the U.S. military.” The strategy emphasizes the destruction of al-Qaeda and the Taliban, and is careful not to commit the U.S. to extensive rebuilding activities in post-Taliban Afghanistan. "The USG [U.S. Government] should not agonize over post-Taliban arrangements to the point that it delays success over Al Qaida and the Taliban.” Operationally, the U.S. will "use any and all Afghan tribes and factions to eliminate Al-Qaida and Taliban personnel," while inserting "CIA teams and special forces in country operational detachments (A teams) by any means, both in the North and the South." Diplomacy is important "bilaterally, particularly with Pakistan, but also with Iran and Russia," however "engaging UN diplomacy… beyond intent and general outline could interfere with U.S. military operations and inhibit coalition freedom of action." U.S. bombing began in Afghanistan on October 7, 2001, the special forces teams arrived October 19, and in the second week of November, in a stunning cascade of Taliban surrenders, all major cities except Kandahar fell to the U.S.-backed Northern Alliance. Taliban leaders took refuge mostly in Pakistan but also around Kandahar, Taliban soldiers melted into the population, and the sequence provided almost a mirror image of the rapid August 2021 implosion of the Afghan government and security forces.

Exhilarated by swift victory over the Taliban in late 2001, the Bush administration quickly switched its attention to Iraq, but by March 2002 Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld was worried again about Afghanistan, writing a snowflake to top aides about setting up a weekly meeting because the situation was “drifting.” Later the same day, Rumsfeld would do a long interview with MSNBC, never mentioning his worries about drift, but rather arguing there was no point in negotiating with Taliban remnants – “the only thing you can do is to bomb them and try to kill them. And that’s what we did, and it worked. They’re gone. And the Afghan people are a lot better off.”

On April 17, 2002, President George W. Bush announced new objectives for Afghanistan in a speech at the Virginia Military Institute, including a stable government, a new army, and a new education system for boys and girls. In effect, Bush’s speech revoked the previous Rumsfeld insistence about not committing “to any post-Taliban military involvement.” That same day when the stated U.S. goals moved to nation building, Rumsfeld’s concerns about no clear exit strategy from Afghanistan crystallized in a short snowflake addressed to his top policy aide Douglas Feith and copied to his deputy Paul Wolfowitz and to the chair and vice-chair of the Joint Chiefs. “I know I’m a bit impatient,” he writes, but “We are never going to get the U.S. military out of Afghanistan unless we take care to see that there is something going on that will provide the stability that will be necessary for us to leave.” “Help!”

This Rumsfeld memo to his policy aide, Douglas Feith, on June 25, 2002 captures how naïve top American officials were about Pakistani motivations, and how throwing money at any problem came to be the core U.S. modus operandi around Afghanistan. Rumsfeld asks, “If we are going to get the Paks to really fight the war on terror where it is, which is in their country, don’t you think we ought to get a chunk of money, so that we can ease Musharraf’s transition from where he is to where we need him.” Rumsfeld does not see how Pakistan and its intelligence service were playing both sides in Afghanistan, and the net for Pakistani leader Musharraf was some $10 billion in U.S. aid over the following six years.

Obtained through FOIA by the National Security Archive

This 14-page email written between August 11 and August 15, 2002, by a Green Beret member of a commando team hunting “high-value” targets circulated at the highest levels of the Pentagon, not least because of its humor and its candor about actual conditions in Afghanistan, and the author’s previous position as a deputy assistant secretary of defense before his Reserve unit mobilized. Roger Pardo-Maurer opened with his “Greetings from scenic Kandahar” which he went on to describe as “Formerly known as ‘Home of the Taliban.’ Now known as ‘Miserable Rat-Fuck Shithole.” “Kandahar is like sitting in a sauna and having a bag of cement shaken over your head.” To those who call it dry heat, Pardo-Maurer, a member of Yale’s class of 1984, rejoins, “you don’t stay dry for long when you are the Lobster Thermidor inside a carapace of about 50 lbs. of Kevlar and ceramic plate armor, with a sweltering chamber pot on your head.” “If there is a landscape less welcoming to humans anywhere on earth, apart from the Sahara, the Poles, and the cauldrons of Kilauea [Hawaii], I cannot imagine it, and I certainly don’t intend to go there.”

Alluding to the continuing role of Pakistan as a Taliban sanctuary, Pardo-Maurer warned, “The shooting match is still very much on. Along the border provinces, you can’t kick a stone over without Bad Guys swarming out like ants and snakes and scorpions.” He recommends staying with a Special Forces strategy “fighting along the Afghans, rather than against them” – “the number one military mistake we could make here is to ‘go conventional’ in this war.” As for “the number one political mistake,” that would be “to actually believe that this place is a country, and that there is such a thing as an Afghan. It is not, and there is not.” “Afghanistan is the place where the world saw fit to stash all the tribes it could not handle elsewhere.” Rumsfeld specifically asked for a copy of the Pardo-Maurer document in a snowflake on September 13, 2002, included here as the cover memo.

In the ongoing debates inside the U.S. government about nation-building in Afghanistan, Rumsfeld insisted that more troops were not the answer, and blamed agencies like State and U.S. AID for the lack of progress. They in turn blamed Rumsfeld for not cooperating with their reconstruction plans and not providing security. He wrote President Bush on August 20, 2002, arguing, “the critical problem in Afghanistan is not really a security problem. Rather, the problem that needs to be addressed is the slow progress that is being made on the civil side.” More troops would backfire, “we could run the risk of ending up being as hated as the Soviets were,” and “without successful reconstruction, no amount of added security forces would be enough.” Yet, because of the “perception that does exist” about security problems, Rumsfeld has assigned a brigadier general (and future U.S. ambassador), Karl Eikenberry, to serve as security coordinator on the staff of the Embassy.

By the fall of 2002, the White House focus centered on the buildup to invading Iraq, to the point that President Bush didn’t even know who his latest commander was in Kabul. This Rumsfeld snowflake, likely to a secretary whose name is redacted on privacy grounds (b6), recounts seeing Bush in the Oval Office on October 21, 2002, asking if he wanted to meet with General Franks (head of Central Command) and General McNeill, and noticing that Bush was quite puzzled. “He said, ‘Who is General McNeill?’ I said he is the general in charge of Afghanistan. He said, ‘Well, I don’t need to meet with him.”

This September 2003 memo from the Secretary of Defense to his top intelligence aide, Steve Cambone, laments that nearly two years into the Afghan war, they still don’t know the enemy. “I have no visibility into who the bad guys are in Afghanistan or Iraq. I read all the intel from the community and it sounds as thought [sic] we know a great deal, but in fact, when you push at it, you find out we haven’t got anything that is actionable.”

Three years into the U.S. nation building project, the Combined Forces Command Afghanistan sent Washington one of its regular “Security Updates” with a two-page list of “ANP Horror Stories” on pages 41 and 42. Police training at that point was in the hands of the State Department (or more precisely, its contractors), which took over from an early failed attempt led by the Germans. So the Secretary of Defense makes sure to alert the Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice, about this “serious problem,” claiming that the two pages “were written in as graceful and non-inflammatory a way as is humanly possible.” Illiterate, underequipped, and unprepared, the police force seemingly had gained little from years of training by State Department contractors, perhaps mainly because police pay was so low that they extorted the very people they were supposed to protect. Later in 2005, the U.S. military would take over police training, and still fail to produce a professional force, not least because the whole idea was foreign to rural Afghans, who settled disputes primarily through village elders.

Document 10

Freedom of Information Act request to the State Department

Ronald Neumann arrived in Kabul as the U.S. ambassador in July 2005, with a long history of connection there as the son of a former U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan. He quickly sized up corruption as “a major threat to the country’s future” describing it as a “long tradition [that] grows like Topsy.” Neumann’s cable ascribes the endemic corruption to multiple factors, “privation” in the form of low official salaries, “insecurity” in the form of 35 years of war, “more foreign ‘loot’” especially the billions coming in from the U.S., “exposure to the outside world” of people better off materially, and “universality” in the sense that everyone was doing it. Neumann also acknowledges the reality that the U.S. was working with “some unsavory political figures” out of necessity. Redacted when the cable was declassified in 2011 are the specific names Neumann reported, and the specific actions he was recommending, but the full version released in 2014 revealed that at the top of his list was an untouchable – Afghan President Hamid Karzai’s half-brother, whom the CIA had paid for years, along with a number of provincial governors, most on U.S. covert payrolls as well. The cable also flags the second front in the Bush Afghan war – narcotics – reporting “opium could strangle the legitimate Afghanistan state in its cradle;” yet, rural Afghans relied on poppy production as their only lucrative crop.

Document 11

In this cable framed as a personal letter to the Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice, U.S. Ambassador Ronald Neumann leads off with an ominous quote from a Taliban leader: "You have all the clocks but we have all the time." Neumann’s plea is for more resources in order to achieve “victory.” He says the U.S. is failing to fund and support fully the activities needed to bolster the Afghan economy, infrastructure, and reconstruction, and that failure is harming the American mission. "We have dared so greatly, and spent so much in blood and money that to try to skimp on what is needed for victory seems to me too risky." The Ambassador notes, "the supplemental decision recommendation to minimize economic assistance and leave out infrastructure plays into the Taliban strategy, not to ours." He warns that Taliban leaders are issuing statements that the U.S. would grow increasingly weary, while they gained momentum.

Document 12

U.S. Ambassador Ronald Neumann writes Washington again in February 2006 with some prescient warnings. He reports that violence in Afghanistan is on the rise but claims “violence does not indicate a failing policy; on the contrary we need to persevere in what we are doing.” Large unit force-on-force engagements devastated the Taliban in previous years, but “the Taliban now seems to understand the propaganda value of the [suicide] bomb and will use it to maximum advantage.” Ambassador Neumann defends the importance of “our work with the GOA [Government of Afghanistan] to extend and deepen its reach nationwide.” “The Taliban need not be intellectual giants to understand that their long-term strategy depends on keeping the government weak in the provinces.” Neumann says the insurgency is getting stronger largely due to the “four years that the Taliban has had to reorganize and think about their approach in a sanctuary [tribal areas in Pakistan] beyond the reach of either [Kabul or Islamabad].” If this sanctuary is “left unaddressed, it will also lead to the re-emergence of the same strategic threat to the United States that prompted our OEF [Operation Enduring Freedom] intervention over 4 years ago.”

Document 13

During May 2006, U.S. Central Command asked the eminent retired four-star general, Barry McCaffrey, to visit Afghanistan and Pakistan and make an assessment of the war (as he had done several times in Iraq). Gen. McCaffrey had served as the drug czar under President Clinton, commanded the “left hook” in the first Gulf War that destroyed so much of the Iraqi army, and won multiple medals for valor and for wounds during the Vietnam war, so his views had significant credibility. Here Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld recommends McCaffrey to the chairman of the Joint Chiefs. The McCaffrey document is couched as a report to his department chairs at the U.S. Military Academy (West Point) where he was an adjunct professor. The cover “snowflake” from Rumsfeld catches only a couple of points from McCaffrey: the lack of small arms for Afghan forces, and the recommendation for almost doubling the size of the Afghan army.

The full document presents a fascinating on-the-one-hand and on-the-other-hand story, praising U.S. and allied troops as well as Hamid Karzai while acknowledging rising violence and Taliban regrouping to the level of battalion-size engagements. McCaffrey warns that the Afghan leadership are “collectively terrified that we will tip-toe out of Afghanistan in the coming few years” and do not believe the U.S. is committed “to stay with them for the fifteen years required to create an independent functional nation-state which can survive in this dangerous part of the world.” He recommends almost doubling the size of the Afghan army (whose “courageous” troops “operate like armed mountain goats in the severe terrain”), claiming “[a] well-equipped, multi-ethnic, literate, and trained Afghan National Army is our ticket to be fully out of country in the year 2020.” A different ticket would be punched in 2021, not least because the Army never achieved any of McCaffrey’s four objectives. McCaffrey saw the Afghan police as “disastrous” but could only think of more money plus adding “a thousand jails, a hundred courts, and a dozen prisons.”

McCaffrey provocatively leads his section on Pakistan with this query: “The central question seems to be – are the Pakistanis playing a giant double-cross in which they absorb one billion dollars a year from the U.S. while pretending to support U.S. objectives to create a stable Afghanistan – while in fact actively supporting cross-border operations of the Taliban (that they created) – in order to give themselves a weak rear area threat for their central struggle with the Indians?” He goes on to doubt that Pakistani leader Pervez Musharraf was playing a deliberate double game, yet even phrasing the question in this way was striking, compared to Rumsfeld’s repeated public praise for Musharraf. Only two months later, Rumsfeld’s own civilian adviser, Dr. Marin Strmecki, would give him an even more detailed report entitled “Afghanistan at a Crossroads,” in which Strmecki doesn’t even see it as a question: “Since 2002, the Taliban has enjoyed a sanctuary in Pakistan.”

Document 14

U.S. Ambassador Ronald Neumann warns Washington in this cable that "we are not winning in Afghanistan; although we are far from losing" (that would take another 14 years). Echoing Gen. McCaffrey’s conclusions (Document 13), Neumann says the primary problem is a lack of political will to provide additional resources to bolster current strategy and to match increasing Taliban offensives. "At the present level of resources we can make incremental progress in some parts of the country, cannot be certain of victory, and could face serious slippage if the desperate popular quest for security continues to generate Afghan support for the Taliban .... Our margin for victory in a complex environment is shrinking, and we need to act now." The Taliban believe they are winning. That perception "scares the hell out of Afghans." "We are too slow." Rapidly increasing certain strategic initiatives such as equipping Afghan forces, taking out the Taliban leadership in Pakistan, and investing heavily in infrastructure can help the Americans regain the upper hand, Neumann declares. "We can still win. We are pursuing the right general policies on governance, security and development. But because we have not adjusted resources to the pace of the increased Taliban offensive and loss of internal Afghan support we face escalating risks today."

Document 15

Declassified by Department of Defense, September 2009

This is the key document behind the Obama “surge” in Afghanistan that produced the highest U.S. troop levels in the whole 20-year war. President Obama’s holdover Secretary of Defense, Robert Gates, had abruptly fired the U.S. commander in Afghanistan, Gen. David McKiernan, after only 11 months, and replaced him with a Special Operations general named Stanley McChrystal, a favorite of Central Command head Gen. David Petraeus, and an acolyte of the Petraeus counterinsurgency approach that had apparently succeeded in Iraq (critics said top Iraqi clerics had simply ordered a truce, for their own reasons). This 66-page assessment had a convoluted public history: written in August 2009, it leaked to the Washington Post in September, likely as part of Pentagon pressure on Obama to approve more troops, and the Pentagon declassified it right away. The McChrystal strategy called for a “properly resourced” counterinsurgency campaign, with at least 40,000 and as many as 60,000 more U.S. troops and massive aid, especially to build up the Afghan army. He wrote, “I believe the short-term fight will be decisive. Failure to gain the initiative and reverse insurgent momentum in the near-term (next 12 months) – while Afghan security capacity matures – risks an outcome where defeating the insurgency is no longer possible.”

McChrystal asked for 60,000 troops, Obama gave him 30,000 but with an 18-month deadline before they would start coming home, and neither the surge nor the deadline ever produced any “maturity” in Afghan security capacity. Testifying to the Senate in December 2009, McChrystal flatly declared “the next eighteen months will likely be decisive and ultimately enable success. In fact, we are going to win.” His 66 pages remain a testament to American military hubris, full of questionable assumptions – that most Afghans saw the Taliban as oppressors and would side with a government installed by foreigners, that most Afghans shared a national identity, and that the Pakistan sanctuaries would not keep the Taliban going indefinitely.

Document 16

The New York Times, Eric Schmitt, “U.S. Envoy’s Cables Show Worries on Afghan Plans,” January 25, 2010

During the Obama debate over whether to surge or not in Afghanistan, some of the strongest criticism of the McChrystal and Pentagon proposals for expanding the military footprint came from inside the government in classified channels – specifically from the former general who had served multiple tours in Afghanistan (Rumsfeld’s first “security coordinator”) and now served as Obama’s ambassador, Karl Eikenberry. This highly classified November 6, 2009, cable, captioned NODIS ARIES, is couched as a personal letter from Eikenberry to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, opposing the proposed troop influx, the vastly increased costs, the concomitant need for yet more civilians, and the resulting increase in Afghan dependency. Eikenberry spells out his reasons: first that Hamid Karzai “is not an adequate strategic partner” – “[h]e and much of his circle are only too happy to see us invest further. They assume we covet their territory for a never-ending war on terror and for military bases to use against surrounding powers.” Second, “we overestimate the ability of Afghan security forces to take over.” Perhaps most important, “[m]ore troops won’t end the insurgency as long as Pakistan sanctuaries remain,” and “Pakistan will remain the single greatest source of Afghan instability.”

Document 17

This follow-up cable (see Document 16) by Ambassador Eikenberry to Secretary Clinton, for her “eyes only,” may have undercut his earlier strong argument against the proposed troop surge. It’s possible that Clinton may have pushed back, or Eikenberry got word his opposition was unwelcome – her side of the correspondence is still classified. Here, Eikenberry just asks for more time to deliberate, a more wide-ranging process, looking at more options other than military counterinsurgency, and convening a high-level expert panel. He admits that more troops “will yield more security wherever they deploy, for as long as they stay.” But he points to the previous troop increase in 2008-2009, amounting to 30,000 soldiers, and says “overall violence and instability in Afghanistan intensified.” Neither the Afghan army nor government “has demonstrated the will or ability to take over lead security responsibility,” he continues. There is “scant reason to expect that further increases will further advance our strategic purposes; instead, they will dig us in more deeply.” Eikenberry lost this debate, and the Obama-Gates-McChrystal troop surge produced all-time high levels of U.S. troops in Afghanistan.

Document 18

Washington Post, The Afghanistan Papers, Freedom of Information lawsuit against SIGAR

Among the hundreds of “lessons learned” interviews undertaken by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction and obtained by Craig Whitlock of the Washington Post through two Freedom of Information lawsuits, this one stands out for its long view, its self-critical perspective, and its high policy level. Richard Boucher was the longest-serving State Department spokesman in history, starting under Madeline Albright, continuing under Colin Powell and even Condoleezza Rice, before taking over the South Asia portfolio at State from 2006 through 2009. Boucher candidly told the SIGAR interviewers in October 2015, “Did we know what we were doing – I think the answer is no. First we went in to get al-Qaeda, and to get al-Qaeda out of Afghanistan, and even without killing Bin Laden we did that. The Taliban was shooting back at us so we started shooting at them and they became the enemy. Ultimately, we kept expanding the mission.” Boucher confessed, “If there was ever a notion of mission creep it is Afghanistan.” His 12 pages of interview transcript include multiple striking observations worth reading in full, about corruption, about local governance and the lack thereof, about the U.S. military’s can-do attitude and where it leads, about roads not taken. His judgment about Afghanistan comes down to a long view: “The only time this country has worked properly was when it was a floating pool of tribes and warlords presided over by someone who had a certain eminence who was able to centralize them to the extent that they didn’t fight each other too much. I think this idea that we went in with, that this was going to become a state government like a U.S. state or something like that, was just wrong and is what condemned us to fifteen years of war instead of two or three.”

Document 19

SIGAR https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/testimony/SIGAR-20-19-TY.pdf

Congress created the SIGAR office in 2008 to combat waste, fraud, and abuse in the U.S. reconstruction effort in Afghanistan, and this statement marked the 22nd time the incumbent, John Sopko, had testified before Congress. The proximate cause of this hearing was the Washington Post publication in December 2019 of “The Afghanistan Papers” series by Craig Whitlock, based in large part on the Post’ s successful lawsuit against SIGAR to obtain copies of the hundreds of “lessons learned” interviews Sopko’s office had done with former policy makers, contractors, and military veterans of Afghanistan. Whitlock also relied on documents the National Security Archive had won through FOIA, notably the Donald Rumsfeld “snowflakes,” and concluded that the U.S. government had systematically misled the public about ostensible progress over nearly two decades in Afghanistan.

Whitlock himself covered this hearing, and his story included even more colorful quotations, apparently from the Q&A period, than can be found in this prepared testimony. For example, “There’s an odor of mendacity throughout the Afghanistan issue … mendacity and hubris.” “The problem is there is a disincentive, really, to tell the truth. We have created an incentive to almost require people to lie.” “When we talk about mendacity, when we talk about lying, it’s not just lying about a particular program. It’s lying by omissions. It turns out that everything that is bad news has been classified for the last few years.” (See Craig Whitlock, “Afghan war plagued by ‘mendacity’ and lies, inspector general tells Congress,” Washington Post , January 15, 2020.)

But the prepared statement is almost as chilling. Sopko told Congress that the system of rotation of U.S. personnel after a year or less in Afghanistan amounted to an “annual lobotomy.” Sopko gave specific examples of fake data and faulty metrics permeating the reconstruction effort: “Unfortunately, many of the claims that State, USAID, and others have made over time simply do not stand up to scrutiny.” Not least, Sopko concluded that “Unchecked corruption in Afghanistan undermined U.S. strategic goals – and we helped to foster that corruption” through “alliances of convenience with warlords” and “flood[ing] a small, weak economy with too much money, too fast.”

Document 20

SIGAR https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/quarterlyreports/2021-07-30qr-section2-security.pdf

This most recent quarterly report from the Special Inspector General provides some noteworthy evidence explaining why Washington would be so surprised by the rapid collapse of Afghan government forces in the two weeks after this was published. The 34-page “security” section leads with the ongoing withdrawal of U.S. and international troops, and the Taliban offensive that “avoided attacking U.S. and Coalition forces.” Maps in the middle of this section (pp. 54-56) show various open-source estimates for Taliban control over Afghani districts, and the report notes that the U.S. military ceased providing any unclassified estimates in 2019. From April to July, apparently, the number of Taliban-controlled districts went from 73 to 221, or more than half the total. Perhaps the most interesting page is page 62, with the sidebar on “the core challenge of properly assessing reconstruction’s effectiveness.” “For years, U.S. taxpayers were told that, although circumstances were difficult, success was achievable.” The document quotes Gen. David Petraeus in 2011, Gen. John Campbell in 2015, Gen. John Nicholson in 2017, and the Pentagon press secretary in 2021 all endorsing the effectiveness of the Afghan security forces. The SIGAR report comments on the $88 billion invested in those forces: “The question of whether that money was well spent will ultimately be answered by the fighting on the ground.”

Afghan Culture

Afghanistan

Core Concepts

- Independence

- Hospitality

Afghanistan is a landlocked south-central Asian country bordering Iran, Pakistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. It is a multi-ethnic society, containing diverse ethnic, linguistic and tribal groups. The government is an Islamic Republic and Islamic values, concepts and practices inform many social and behavioural norms throughout society. Afghans generally have a strong sense of personal honour and are highly aware of their community’s opinion of them. Hospitality, loyalty and modesty are highly valued. However, Afghan culture and daily life have been significantly impacted by constant conflict. Resilience is now an essential trait that has become instilled within the Afghan character as a result of these experiences.

National Identity

The relentless conflicts of the late 20th and 21st century have produced generations of Afghans who have rarely experienced peace. They have resisted invasions from Great Britain and the Soviet Union, and continue to persevere despite the ongoing insurgency by the Taliban and others. Consequently, many Afghans think of themselves as survivors. Further, people are often strongly opposed to outside interference in internal politics. This has translated into a prevailing national attitude that strongly favours independence from controlling bodies. However, the assertion of the country’s independence has not necessarily resulted in national cohesiveness. Afghans tend to hold a stronger sense of loyalty for their kin, tribe or ethnicity than their national identity (see Ethnicity below).

Some older Afghans may see the hardship and political turmoil of the past few decades as a recent devastating chapter in a much longer peaceful history. Prior to the Soviet invasion, Afghanistan was widely considered to be a peaceful country in the Asia region. For example, the country remained neutral during World War II. People may express disappointment or dismay at the fact that most Western perceptions of their country are formulated around news of terrorism and turmoil without insight into the geopolitical factors that caused such conflicts.

Such perceptions overlook many of the positive aspects of the culture, such as its respect for artistry and intellectualism. For example, the Afghan artistic style is very decorative and embellished. Many Afghan items are beautifully embroidered in woven finery, including those that are used for everyday purposes (e.g. grain bags). Embellishment is also noticeable in the language, with poetry being one of the most admired art forms. Respect is shown to those who have proof of expertise and can speak eloquently.

Community Organisation

According to the most recently available estimates, over 60% of the Afghan population is under 25 years of age. 1 This young age structure reflects the impact of decades of conflict, widespread poverty, political instability, displacement and the lack of substantial infrastructure. Most reside in rural areas, as Afghan culture is traditionally agricultural. Many people are produce or livestock farmers living at a subsistence level. Generally, all Afghans have to work very hard to make ends meet (child labour is common from the age of five and involves both genders).

Most villages and rural regions tend to govern themselves. In small villages, there is a lack of schools, stores or government representation. There may be three authority figures: the village head man ( malik ), the master of water distribution ( mirab ) and the teacher of Islamic laws ( mullah ) whose role is to make judgements as to whether someone’s behaviour is observing of the Qur’an. Often a village will have a large landowner ( khan ) who governs by assuming the role of both the malik and mirab. However, an assembly of men ( jirga ) usually vote on the important decisions that affect the whole village or tribe.

Dependence upon kin and community is particularly crucial to survival as there is a broad absence and mistrust of government involvement in people’s personal lives. This is exacerbated by the underfunded social services that are often unable to meet basic needs due to corruption and lack of security. Therefore, if an Afghan is in crisis and essential needs must be met, they usually have no choice but to turn to those of the same family, village/community, tribe or ethnicity for assistance (in that general order of preference).

One’s ethnicity is an instant cultural identifier in Afghanistan and usually defines people’s social organisation. The most common ethnic groups are the Pashtuns, Tajiks and Hazaras. However, there are also significant populations of Uzbeks, Nuristani, Aimak, Turkmen and Baloch (among others).

The Pashtun are the largest ethnic group in Afghanistan. Most speak Pashto and are Sunni Muslims. Pashtun culture and social organisation have been traditionally influenced by tribal codes of honour and interpretations of Islamic law. This is recognised as ‘ Pashtunwali ’ – a moral and legal code that determines the social expectations one should follow to honour Islamic and cultural values. Pashtunwali, in its strictest form, is mostly only followed in rural tribes. However, its influence can still be seen in much of Pashtun behaviour. For example, values such as honour, loyalty, hospitality and protection of female relatives remain important principles of social responsibility throughout Afghanistan.

The Pashtun are widely regarded as the most politically influential and dominant group in Afghanistan. 2 Successive governments have formed via the political expansion of Pashtun tribes with international assistance. Members of minority ethnicities have argued that the national identity of the country is exclusionary of non-Pashtun ethnicities. “ Afghanistan ” actually means “ Land of the Pashtun ” in Dari. Indeed, “ Afghan ” exclusively referred to Pashtuns before it came to refer to the citizens of the state.

Nevertheless, while Pashtuns have continuously held advantage in the political domain, many do not see or receive the privileges that come from being a member of the most dominant ethnic group. Political power and economic wealth definitively lies in the hands of the few. Many Pashtuns earn subsistence-level or very modest incomes as traders, farmers, livestock breeders and merchants.

The Tajiks have Persian heritage and are Afghanistan’s second largest ethnicity . Unlike most other ethnicities, they are not tribal and do not organise themselves by tribal association. Instead, their loyalty revolves around their family and village (or local community for those living in urban areas). This is evident in the way many Tajik last names tend to reflect their place of origin, rather than their tribe or ethnicity .

Tajiks are majority Sunni Muslim and generally speak a dialect of Persian found in Eastern Iran. The Tajiks tend to be more urbanised than many other ethnicities and are relatively less rigid in their adherence to provincial attitudes. Some reside in Kabul or the north-eastern part of the country. Many also live in the west, close to the Iranian border. Those who live in the cities are usually traders or skilled artisans. However, the majority are farmers and herders.

Tajiks commonly have a high level of education and wealth (in comparison to some of Afghanistan’s more impoverished ethnicities), which has seen them be widely considered to be among Afghanistan’s elite. According to Minority Rights Group International, this accumulated privilege gives them quite a high social status as an ethnic group. However, the Tajik political influence is not very dominant. Many Tajiks have been persecuted amidst the unrest of the past 35 years and discussions over their political representation in government continue.

The Hazara people are widely understood to be one of the most socially and politically marginalised ethnic groups in Afghanistan. They speak a dialect of Dari known as ‘ Hazaragi ’ and make up the largest Shi’a Muslim population in the country. Most Hazaras live in the central mountain region (called the Hazarajat ) and in certain districts of Kabul.

The Hazaras have been persecuted by Pashtun leaders, civil warlords, the Taliban , ISIS and others due to their Shi’a Muslim beliefs. For example, government policies have excluded them from public service and capped their ranks in the military. This has resulted in their systemic lack of political power and influence in a Sunni Muslim majority country. The persecution of Hazaras has been particularly fierce as they have hereditary features (from distant Mongol ancestry) that physically distinguish their ethnicity from other Afghans.

Many Hazaras have lived through raids and massacres of their people, both in past and recent years. Some have escaped this danger in neighbouring Pakistan where other Sunni extremists have also sought to target and kill them. Consequently, many have been left with no choice but to flee to more distant countries. As a result, a large portion of the Afghans in Western countries are Hazara refugees who have sought asylum from this situation.

The Hazarajat region remains very poor, meaning many Hazaras are economically supported by a male family member who has journeyed to a city or neighbouring country to find work. Being at the bottom of the economic and social hierarchy has also stigmatised Hazaras in the minds of most other ethnic groups. This is acutely reflected in the lack of inter-ethnic marriages with Hazaras. Nevertheless, more recently, Hazaras have been pursuing higher education and political positions to represent their people and become leaders in the newly emerging democracy .

Within many ethnic groups, there are long-standing tribal clans formed through kinships. These tribes often live as local communities in villages. Most tribes inherit the land and means of production from their ancestors. Others may continue the nomadic lifestyle their forebears lived. In small villages and rural areas, there is usually little social mobility between occupations as people are expected to take over their parents’ form of economic contribution, which may also be circumscribed by tribal positioning.

Some Afghans’ affiliations to their tribes have been disrupted as conflict has forced people to prioritise their individual family’s survival. However, those who have remained connected and united with their tribe continue to be extremely loyal. For those people, loyalty to their tribe is secondary only to their obligation to their family. Tribes generally uphold:

- the right and duty to avenge any wrong against its people;

- the right of fugitives to seek refuge and sanctuary;

- the duty to show hospitality to guests and protect them if need be;

- the need to defend their property and honour; and

- the need to defend and protect one’s female relatives.

Over the centuries, rival tribal groups have constantly competed over rights to land, resources, power and even women. This has engendered a competitive spirit in Afghan culture and has been the cause of a great deal of recurrent violence and disharmony between tribes and ethnicities.

Much social behaviour is influenced by Afghans’ awareness of their personal honour. ‘Honour’ in this sense encompasses an individual’s reputation, prestige and worth. Preservation of honour and community opinion is often at the forefront of people’s minds. It influences people to behave conservatively in accordance with social expectations to avoid drawing attention to themselves or risk doing something perceived to be dishonourable.

As members of a collectivist society, most Afghans consider a person’s behaviour to be reflective of the family, tribe or ethnicity they belong to. Thus, when a person’s behaviour is perceived to be dishonourable, their family shares the shame. When the dishonourable behaviour occurs outside of a person’s community, other Afghans can often quickly implicate that person’s ethnic group, tribe and/or religion as the cause of their behaviour. As a result, Afghans can be wary of the fact that they need to give a public impression of dignity and integrity to protect the honour of those they are associated with. To prevent indignity, criticism is rarely given directly and praise is expected to be generously offered.

The senior male of a family is considered to be responsible for protecting the honour of the family. They are often particularly concerned with the behaviour of the women in their family, as females have many social expectations to comply with. These relate to their moral code, dress, social interactions, education, economic activity and public involvement (visit Family for more information). A breach of social compliance by a woman can be perceived as a failure on the man’s behalf (her father, husband or brother) to protect her from doing so.

Ethnic Relations and Politics

Relationships between different ethnic groups can be tense. Minority ethnic groups have often argued that the national identity, politics and civil service of Afghanistan exclude non-Pashtuns. Pashtun public interests commonly supersede those of other ethnicities that seek greater recognition. This has been exacerbated by the fact that insurgency groups, such as the Taliban , are predominantly made up of Pashtun men. The Taliban is not only a religious extremist group, but also a Pashtun nationalist group aiming to establish an Afghan emirate. 3

In addition to the mistreatment some ethnicities have suffered under others in the recent decades of war, there are many ethnic feuds that have been passed down through generations. For example, Pashtuns may fault the Uzbeks for the actions of the previous generations, and the violent conflict between Pashtuns and Hazaras can be traced back to the 19th century. Sometimes the Afghan sense of honour means that different groups feel old injustices need to be avenged. The loyalty to blood ties and ethnicity reflects the deep tribalism and collectivism of Afghan society.

Current Experiences

More recently, the ethno-linguistic groups of Afghanistan have experienced a degree of unity through the shared experience of unremitting war, displacement and survival. This has given rise to cultural resilience but also national exhaustion. As the source of the world’s largest and most enduring refugee population, many Afghans have a shared experience of exile. Millions have been involuntarily displaced to surrounding countries such as Pakistan and Iran where they reside as refugees in dangerous, marginalising and uncertain conditions. Some have fled to the West to escape capture, torture or death. The majority of Afghan-born people residing in Western countries share this war-torn experience. Today, most people wish for peaceful relations.

The Afghan people have also been slowly reclaiming their freedom of expression since the early 2000s. Communications have improved and developed quickly in the last 10 years or so. Today, many people have up-to-date technology and smartphones that allow them to access the internet and media outlets. Social media is also widely used, which has led to a flourishing involvement of youth who are highly politically engaged. The modern aspirations of the younger generation have changed with the arrival of the internet and mass media.

_____________________

1 Central Intelligence Agency, 2018

2 Minority Rights Group International, 2018

3 Seerat, 2017

Get a downloadable PDF that you can share, print and read.

Develop diverse workforces, markets and communities with our new platform

Mobile Menu Overlay

The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Ave NW Washington, DC 20500

Remarks by President Biden on the Way Forward in Afghanistan

Treaty Room

2:29 P.M. EDT THE PRESIDENT: Good afternoon. I’m speaking to you today from the Roosevelt — the Treaty Room in the White House. The same spot where, on October of 2001, President George W. Bush informed our nation that the United States military had begun strikes on terrorist training camps in Afghanistan. It was just weeks — just weeks after the terrorist attack on our nation that killed 2,977 innocent souls; that turned Lower Manhattan into a disaster area, destroyed parts of the Pentagon, and made hallowed ground of a field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, and sparked an American promise that we would “never forget.” We went to Afghanistan in 2001 to root out al Qaeda, to prevent future terrorist attacks against the United States planned from Afghanistan. Our objective was clear. The cause was just. Our NATO Allies and partners rallied beside us. And I supported that military action, along with overwhelming majority of the members of Congress. More than seven years later, in 2008, weeks before we swore the oath of office — President Obama and I were about to swear — President Obama asked me to travel to Afghanistan and report back on the state of the war in Afghanistan. I flew to Afghanistan, to the Kunar Valley — a rugged, mountainous region on the border with Pakistan. What I saw on that trip reinforced my conviction that only the Afghans have the right and responsibility to lead their country, and that more and endless American military force could not create or sustain a durable Afghan government. I believed that our presence in Afghanistan should be focused on the reason we went in the first place: to ensure Afghanistan would not be used as a base from which to attack our homeland again. We did that. We accomplished that objective. I said, among — with others, we’d follow Osama bin Laden to the gates of hell if need be. That’s exactly what we did, and we got him. It took us close to 10 years to put President Obama’s commitment to — into form. And that’s exactly what happened; Osama bin Laden was gone. That was 10 years ago. Think about that. We delivered justice to bin Laden a decade ago, and we’ve stayed in Afghanistan for a decade since. Since then, our reasons for remaining in Afghanistan are becoming increasingly unclear, even as the terrorist threat that we went to fight evolved. Over the past 20 years, the threat has become more dispersed, metastasizing around the globe: al-Shabaab in Somalia; al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula; al-Nusra in Syria; ISIS attempting to create a califit [caliphate] in Syria and Iraq, and establishing affiliates in multiple countries in Africa and Asia. With the terror threat now in many places, keeping thousands of troops grounded and concentrated in just one country at a cost of billions each year makes little sense to me and to our leaders. We cannot continue the cycle of extending or expanding our military presence in Afghanistan, hoping to create ideal conditions for the withdrawal, and expecting a different result. I’m now the fourth United States President to preside over American troop presence in Afghanistan: two Republicans, two Democrats. I will not pass this responsibility on to a fifth. After consulting closely with our allies and partners, with our military leaders and intelligence personnel, with our diplomats and our development experts, with the Congress and the Vice President, as well as with Mr. Ghani and many others around the world, I have concluded that it’s time to end America’s longest war. It’s time for American troops to come home. When I came to office, I inherited a diplomatic agreement, duly negotiated between the government of the United States and the Taliban, that all U.S. forces would be out of Afghanistan by May 1, 2021, just three months after my inauguration. That’s what we inherited — that commitment. It is perhaps not what I would have negotiated myself, but it was an agreement made by the United States government, and that means something. So, in keeping with that agreement and with our national interests, the United States will begin our final withdrawal — begin it on May 1 of this year. We will not conduct a hasty rush to the exit. We’ll do it — we’ll do it responsibly, deliberately, and safely. And we will do it in full coordination with our allies and partners, who now have more forces in Afghanistan than we do. And the Taliban should know that if they attack us as we draw down, we will defend ourselves and our partners with all the tools at our disposal. Our allies and partners have stood beside us shoulder-to-shoulder in Afghanistan for almost 20 years, and we’re deeply grateful for the contributions they have made to our shared mission and for the sacrifices they have borne. The plan has long been “in together, out together.” U.S. troops, as well as forces deployed by our NATO Allies and operational partners, will be out of Afghanistan before we mark the 20th anniversary of that heinous attack on September 11th. But — but we’ll not take our eye off the terrorist threat. We’ll reorganize our counterterrorism capabilities and the substantial assets in the region to prevent reemergence of terrorists — of the threat to our homeland from over the horizon. We’ll hold the Taliban accountable for its commitment not to allow any terrorists to threaten the United States or its allies from Afghan soil. The Afghan government has made that commitment to us as well. And we’ll focus our full attention on the threat we face today. At my direction, my team is refining our national strategy to monitor and disrupt significant terrorist threats not only in Afghanistan, but anywhere they may arise — and they’re in Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and elsewhere. I spoke yesterday with President Bush to inform him of my decision. While he and I have had many disagreements over policies throughout the years, we’re absolutely united in our respect and support for the valor, courage, and integrity of the women and men of the United States Armed Forces who served. I’m immensely grateful for the bravery and backbone that they have shown through nearly two decades of combat deployments. We as a nation are forever indebted to them and to their families. You all know that less than 1 percent of Americans serve in our armed forces. The remaining 99 percent of them — we owe them. We owe them. They have never backed down from a single mission that we’ve asked of them. I’ve witnessed their bravery firsthand during my visits to Afghanistan. They’ve never wavered in their resolve. They’ve paid a tremendous price on our behalf. And they have the thanks of a grateful nation. While we will not stay involved in Afghanistan militarily, our diplomatic and humanitarian work will continue. We’ll continue to support the government of Afghanistan. We will keep providing assistance to the Afghan National Defenses and Security Forces. And along with our partners, we have trained and equipped a standing force of over 300,000 Afghan personnel today and hundreds of thousands over the past two decades. And they’ll continue to fight valiantly, on behalf of the Afghans, at great cost. They’ll support peace talks, as we will support peace talks between the government of Afghanistan and the Taliban, facilitated by the United Nations. And we’ll continue to support the rights of Afghan women and girls by maintaining significant humanitarian and development assistance. And we’ll ask other countries — other countries in the region — to do more to support Afghanistan, especially Pakistan, as well as Russia, China, India, and Turkey. They all have a significant stake in the stable future for Afghanistan. And over the next few months, we will also determine what a continued U.S. diplomatic presence in Afghanistan will look like, including how we’ll ensure the security of our diplomats. Look, I know there are many who will loudly insist that diplomacy cannot succeed without a robust U.S. military presence to stand as leverage. We gave that argument a decade. It’s never proved effective — not when we had 98,000 troops in Afghanistan, and not when we were down to a few thousand. Our diplomacy does not hinge on having boots in harm’s way — U.S. boots on the ground. We have to change that thinking. American troops shouldn’t be used as a bargaining chip between warring parties in other countries. You know, that’s nothing more than a recipe for keeping American troops in Afghanistan indefinitely. I also know there are many who will argue that we should stay — stay fighting in Afghanistan because withdrawal would damage America’s credibility and weaken America’s influence in the world. I believe the exact opposite is true. We went to Afghanistan because of a horrific attack that happened 20 years ago. That cannot explain why we should remain there in 2021. Rather than return to war with the Taliban, we have to focus on the challenges that are in front of us. We have to track and disrupt terrorist networks and operations that spread far beyond Afghanistan since 9/11. We have to shore up American competitiveness to meet the stiff competition we’re facing from an increasingly assertive China. We have to strengthen our alliances and work with like-minded partners to ensure that the rules of international norms that govern cyber threats and emerging technologies that will shape our future are grounded in our democratic values — values — not those of the autocrats. We have to defeat this pandemic and strengthen the global health system to prepare for the next one, because there will be another pandemic. You know, we’ll be much more formidable to our adversaries and competitors over the long term if we fight the battles for the next 20 years, not the last 20. And finally, the main argument for staying longer is what each of my three predecessors have grappled with: No one wants to say that we should be in Afghanistan forever, but they insist now is not the right moment to leave. In 2014, NATO issued a declaration affirming that Afghan Security Forces would, from that point on, have full responsibility for their country’s security by the end of that year. That was seven years ago. So when will it be the right moment to leave? One more year, two more years, ten more years? Ten, twenty, thirty billion dollars more above the trillion we’ve already spent? “Not now” — that’s how we got here. And in this moment, there’s a significant downside risk to staying beyond May 1st without a clear timetable for departure. If we instead pursue the approach where America — U.S. exit is tied to conditions on the ground, we have to have clear answers to the following questions: Just what conditions require to — be required to allow us to depart? By what means and how long would it take to achieve them, if they could be achieved at all? And at what additional cost in lives and treasure? I’m not hearing any good answers to these questions. And if you can’t answer them, in my view, we should not stay. The fact is that, later today, I’m going to visit Arlington National Cemetery, Section 60, and that sacred memorial to American sacrifice. Section sisty [sic] — Section 60 is where our recent war dead are buried, including many of the women and men who died fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq. There’s no — there’s no comforting distance in history in Section 60. The grief is raw. It’s a visceral reminder of the living cost of war. For the past 12 years, ever since I became Vice President, I’ve carried with me a card that reminds me of the exact number of American troops killed in Iraq and Afghanistan. That exact number, not an approximation or rounded-off number — because every one of those dead are sacred human beings who left behind entire families. An exact accounting of every single solitary one needs to be had. As of the day — today, there are two hundred and forty- — 2,488 [2,448] U.S. troops and personnel who have died in Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Freedom’s Sentinel — our Afghanistan conflicts. 20,722 have been wounded. I’m the first President in 40 years who knows what it means to have a child serving in a warzone. And throughout this process, my North Star has been remembering what it was like when my late son, Beau, was deployed to Iraq — how proud he was to serve his country; how insistent he was to deploy with his unit; and the impact it had on him and all of us at home. We already have service members doing their duty in Afghanistan today whose parents served in the same war. We have service members who were not yet born when our nation was attacked on 9/11. War in Afghanistan was never meant to be a multi-generational undertaking. We were attacked. We went to war with clear goals. We achieved those objectives. Bin Laden is dead, and al Qaeda is degraded in Iraq — in Afghanistan. And it’s time to end the forever war. Thank you all for listening. May God protect our troops. May God bless all those families who lost someone in this endeavor. 2:45 P.M. EDT

Stay Connected

We'll be in touch with the latest information on how President Biden and his administration are working for the American people, as well as ways you can get involved and help our country build back better.

Opt in to send and receive text messages from President Biden.

Got any suggestions?

We want to hear from you! Send us a message and help improve Slidesgo

Top searches

Trending searches

solar eclipse

25 templates

autism awareness

28 templates

26 templates

16 templates

6 templates

32 templates

History Subject for High School: Afghanistan Independence Day

History subject for high school: afghanistan independence day presentation, premium google slides theme and powerpoint template.

Teach high school students about Afghanistan Independence Day with this wonderful template! It has everything you could want: lots of illustrations of the Afghan flag, photos, graphs… It’s a great way to introduce the subject to young people who might not be familiar with the country. Simply add the information you want to discuss, and you’ll have an attractive presentation that can help you broaden your students’ horizons. And it’s all designed in the colors of the country’s flag!

Features of this template

- 100% editable and easy to modify

- 35 different slides to impress your audience

- Contains easy-to-edit graphics such as graphs, maps, tables, timelines and mockups

- Includes 500+ icons and Flaticon’s extension for customizing your slides

- Designed to be used in Google Slides and Microsoft PowerPoint

- 16:9 widescreen format suitable for all types of screens

- Includes information about fonts, colors, and credits of the resources used

What are the benefits of having a Premium account?

What Premium plans do you have?

What can I do to have unlimited downloads?

Don’t want to attribute Slidesgo?

Gain access to over 22300 templates & presentations with premium from 1.67€/month.

Are you already Premium? Log in

Related posts on our blog

How to Add, Duplicate, Move, Delete or Hide Slides in Google Slides

How to Change Layouts in PowerPoint

How to Change the Slide Size in Google Slides

Related presentations.

Premium template

Unlock this template and gain unlimited access

- Conflicts and crisis management

- Defence and deterrence

- Global security challenges

- Historical republications

- NATO and its member countries

- NATO partners and cooperative security

- Personal perspectives

- Terrorism and violent extremism

- Wider aspects of defence and security

- Women, peace and security

- Miscellaneous

What is published in NATO Review does not constitute the official position or policy of NATO or member governments. NATO Review seeks to inform and promote debate on security issues. The views expressed by authors are their own.

NATO's engagement in Afghanistan, 2003-2021: a planner’s perspective

- Diego A. Ruiz Palmer

- 20 June 2023

This coming summer will mark the twentieth anniversary of the initiation of NATO's engagement in Afghanistan in August 2003, which ended in August 2021 as a result of the collapse of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (GIRoA) and the return to power of the Taliban.

This endeavour, extraordinary in both ambition and scope, brought together the commitments and contributions of troops and other resources by nearly 50 NATO and non-NATO nations from around the world, with the goal of building a stable Afghanistan freed from use as a safe haven for terrorism. Many obstacles stood in the way, from the troubled legacy of three decades of internal strife and invasion following the fall of the monarchy in 1973, to complex regional dynamics and challenges associated with frequent troop rotations and civil-military cooperation across the security, governance and development nexus.

Spanish and U.S. troops who participated in the International Security Assistance Force board a CH-47 helicopter at Bala Murghab Forward Operating Base on Sept. 27, 2008. © ISAF Public Affairs via DVIDS

This article takes a longer view of the goals and achievements of NATO’s engagement in Afghanistan, and offers a planner’s perspective on the conditions and constraints under which the planning for, and the implementation of, that engagement were executed. The record of policy guidance and planning addressed below indicates that, far from neglecting the principles and practices that should guide interventions by the international community, NATO strove persistently and resolutely to follow them, notably in relation to the genuine inclusion of Afghans, local ownership by the Afghan people and regional cooperation with Afghanistan’s neighbours.

NATO’s evolving planning framework for Afghanistan

NATO assumed command of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in August 2003 in the wake of the exceptional circumstances that had been created by the terrorist attacks on the United States of 11 September, 2001. The planning for these attacks had originated on the territory of Afghanistan. In response, Allies took the unanimous position that the attacks represented an aggression against them all and, accordingly, invoked Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty for the first time in NATO’s history.

What Allies could not have known in 2003-2006 is that the insurgency would prove to be more capable and resilient than expected. This was due to domestic and regional dynamics… over which NATO had limited influence, and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan proved to have a limited willingness and capacity to control.

NATO acknowledged early on in its planning the challenges stemming from the ISAF commitment to help establish a safe and secure environment throughout Afghanistan under a United Nations Security Council mandate. For example, such planning recognised that, as ISAF gradually assumed command of international forces across the country between August 2003 and October 2006, this widening footprint would require deeper commitment by the Allies and other ISAF troop contributing nations (TCN), in terms of political resolve, forces and financial resources. This higher ambition also mandated developing a longer-term vision for NATO’s engagement across a broad spectrum of tasks, as well as reaching out to an increasing number of non-NATO nations that had expressed a wish to contribute forces or resources to ISAF. Drawing on its experience in helping bring wars to an end in the former Yugoslavia, NATO, a collective defence alliance, became the core of a wider security assistance coalition.

What Allies could not have known in 2003-2006 is that the insurgency would prove to be more capable and resilient than expected. This was due to domestic and regional dynamics – including grievances driven by pervasive bad governance and the use of safe havens across the region – over which NATO had limited influence, and the GIRoA proved to have a limited willingness and capacity to control. Despite this enduring challenge, NATO stayed the course, widened the scope of its strategic planning and deepened its engagement. This involved training the Afghan National Army, helping to mentor the nascent Afghan National Police and supporting broader stabilisation and reconstruction efforts, in close coordination with a range of actors, notably the United Nations and the European Union.

Two advisers from Task Force Forge demonstrated how to clear a room during security operations training at the Regional Military Training Center in Helmand Province, Afghanistan, March 8, 2017. Task Force Forge was a train, advise and assist unit which supported the NATO Resolute Support mission. © NATO

To capture this broader commitment, Allies agreed that a comprehensive plan, setting out NATO’s near and longer-term objectives and tasks, and aimed at better harmonising ISAF's military activities with other dimensions of NATO's engagement and with that of the wider international community, was necessary. Accordingly, planning efforts at NATO Headquarters gathered strength and culminated in the approval of a Comprehensive, Strategic, Political-Military Plan by Heads of State and Government (HoSG) of the ISAF TCNs at NATO's Bucharest Summit in spring 2008.

The design of the plan closely followed the precepts of the “Comprehensive Approach” concept, in relation to consultation and cooperation with the GIRoA and with other stakeholders, as well as its implications for interagency coordination within the governments of TCNs. While mindful that ISAF was responsible only for the military line of effort, NATO was aware that helping the Afghan people assume ownership of their future required a broad approach to restoring a shared sense of the country. Contrary to the assertions that NATO lacked a comprehensive and coherent approach and a long-term strategic plan, and that Allies were obsessed with (military) state building, the strengthening of state institutions was pursued as a means to anchor the ties between the Afghan people and their recovered nation.

The wider, fluid context of NATO’s engagement in Afghanistan

NATO also recognised early in its engagement in Afghanistan that the success of ISAF in helping establish a safe and secure environment in southern and eastern Afghanistan – the traditional Pashtun lands and Taliban strongholds along Afghanistan's borders with Pakistan – would be dependent on rallying the Pashtun tribes in support of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (GIRoA). It would also require working with Pakistan to prevent the Taliban from using tribal territories in western Pakistan as a rear area for the insurgency. To those ends, NATO made Kandahar Province the centre of gravity of ISAF operations and NATO’s assistance to wider stabilisation and reconstruction efforts, and engaged Pakistan alongside the United States in facilitating bilateral talks between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

In this endeavour, NATO was mindful of the importance of respecting Afghanistan's sovereignty, promoting Afghan ownership and accountability, and encouraging the GIRoA to implement inclusive policies. These goals were pursued against the backdrop of widespread corruption and complex and often obscure tribal dynamics at play among the various ethnic groups and between the provinces and Kabul, as well as the absence of a virtuous regional dynamic among Afghanistan’s neighbours that would have made the prospect of a peaceful and prosperous Afghanistan a worthy common cause.

A vehicle mounted with Afghan National Police officers led a patrol of dismounted U.S. soldiers from the 18th Military Police company into the village of Woluswali Kolangar, Pole-Elam District, Logar Province, Afghanistan, 17 March 2010. The purpose of this patrol was to show presence in the village and keep security. © U.S. Army