Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Quantitative Methods

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Quantitative methods emphasize objective measurements and the statistical, mathematical, or numerical analysis of data collected through polls, questionnaires, and surveys, or by manipulating pre-existing statistical data using computational techniques . Quantitative research focuses on gathering numerical data and generalizing it across groups of people or to explain a particular phenomenon.

Babbie, Earl R. The Practice of Social Research . 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage, 2010; Muijs, Daniel. Doing Quantitative Research in Education with SPSS . 2nd edition. London: SAGE Publications, 2010.

Need Help Locating Statistics?

Resources for locating data and statistics can be found here:

Statistics & Data Research Guide

Characteristics of Quantitative Research

Your goal in conducting quantitative research study is to determine the relationship between one thing [an independent variable] and another [a dependent or outcome variable] within a population. Quantitative research designs are either descriptive [subjects usually measured once] or experimental [subjects measured before and after a treatment]. A descriptive study establishes only associations between variables; an experimental study establishes causality.

Quantitative research deals in numbers, logic, and an objective stance. Quantitative research focuses on numeric and unchanging data and detailed, convergent reasoning rather than divergent reasoning [i.e., the generation of a variety of ideas about a research problem in a spontaneous, free-flowing manner].

Its main characteristics are :

- The data is usually gathered using structured research instruments.

- The results are based on larger sample sizes that are representative of the population.

- The research study can usually be replicated or repeated, given its high reliability.

- Researcher has a clearly defined research question to which objective answers are sought.

- All aspects of the study are carefully designed before data is collected.

- Data are in the form of numbers and statistics, often arranged in tables, charts, figures, or other non-textual forms.

- Project can be used to generalize concepts more widely, predict future results, or investigate causal relationships.

- Researcher uses tools, such as questionnaires or computer software, to collect numerical data.

The overarching aim of a quantitative research study is to classify features, count them, and construct statistical models in an attempt to explain what is observed.

Things to keep in mind when reporting the results of a study using quantitative methods :

- Explain the data collected and their statistical treatment as well as all relevant results in relation to the research problem you are investigating. Interpretation of results is not appropriate in this section.

- Report unanticipated events that occurred during your data collection. Explain how the actual analysis differs from the planned analysis. Explain your handling of missing data and why any missing data does not undermine the validity of your analysis.

- Explain the techniques you used to "clean" your data set.

- Choose a minimally sufficient statistical procedure ; provide a rationale for its use and a reference for it. Specify any computer programs used.

- Describe the assumptions for each procedure and the steps you took to ensure that they were not violated.

- When using inferential statistics , provide the descriptive statistics, confidence intervals, and sample sizes for each variable as well as the value of the test statistic, its direction, the degrees of freedom, and the significance level [report the actual p value].

- Avoid inferring causality , particularly in nonrandomized designs or without further experimentation.

- Use tables to provide exact values ; use figures to convey global effects. Keep figures small in size; include graphic representations of confidence intervals whenever possible.

- Always tell the reader what to look for in tables and figures .

NOTE: When using pre-existing statistical data gathered and made available by anyone other than yourself [e.g., government agency], you still must report on the methods that were used to gather the data and describe any missing data that exists and, if there is any, provide a clear explanation why the missing data does not undermine the validity of your final analysis.

Babbie, Earl R. The Practice of Social Research . 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage, 2010; Brians, Craig Leonard et al. Empirical Political Analysis: Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods . 8th ed. Boston, MA: Longman, 2011; McNabb, David E. Research Methods in Public Administration and Nonprofit Management: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches . 2nd ed. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2008; Quantitative Research Methods. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Singh, Kultar. Quantitative Social Research Methods . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2007.

Basic Research Design for Quantitative Studies

Before designing a quantitative research study, you must decide whether it will be descriptive or experimental because this will dictate how you gather, analyze, and interpret the results. A descriptive study is governed by the following rules: subjects are generally measured once; the intention is to only establish associations between variables; and, the study may include a sample population of hundreds or thousands of subjects to ensure that a valid estimate of a generalized relationship between variables has been obtained. An experimental design includes subjects measured before and after a particular treatment, the sample population may be very small and purposefully chosen, and it is intended to establish causality between variables. Introduction The introduction to a quantitative study is usually written in the present tense and from the third person point of view. It covers the following information:

- Identifies the research problem -- as with any academic study, you must state clearly and concisely the research problem being investigated.

- Reviews the literature -- review scholarship on the topic, synthesizing key themes and, if necessary, noting studies that have used similar methods of inquiry and analysis. Note where key gaps exist and how your study helps to fill these gaps or clarifies existing knowledge.

- Describes the theoretical framework -- provide an outline of the theory or hypothesis underpinning your study. If necessary, define unfamiliar or complex terms, concepts, or ideas and provide the appropriate background information to place the research problem in proper context [e.g., historical, cultural, economic, etc.].

Methodology The methods section of a quantitative study should describe how each objective of your study will be achieved. Be sure to provide enough detail to enable the reader can make an informed assessment of the methods being used to obtain results associated with the research problem. The methods section should be presented in the past tense.

- Study population and sampling -- where did the data come from; how robust is it; note where gaps exist or what was excluded. Note the procedures used for their selection;

- Data collection – describe the tools and methods used to collect information and identify the variables being measured; describe the methods used to obtain the data; and, note if the data was pre-existing [i.e., government data] or you gathered it yourself. If you gathered it yourself, describe what type of instrument you used and why. Note that no data set is perfect--describe any limitations in methods of gathering data.

- Data analysis -- describe the procedures for processing and analyzing the data. If appropriate, describe the specific instruments of analysis used to study each research objective, including mathematical techniques and the type of computer software used to manipulate the data.

Results The finding of your study should be written objectively and in a succinct and precise format. In quantitative studies, it is common to use graphs, tables, charts, and other non-textual elements to help the reader understand the data. Make sure that non-textual elements do not stand in isolation from the text but are being used to supplement the overall description of the results and to help clarify key points being made. Further information about how to effectively present data using charts and graphs can be found here .

- Statistical analysis -- how did you analyze the data? What were the key findings from the data? The findings should be present in a logical, sequential order. Describe but do not interpret these trends or negative results; save that for the discussion section. The results should be presented in the past tense.

Discussion Discussions should be analytic, logical, and comprehensive. The discussion should meld together your findings in relation to those identified in the literature review, and placed within the context of the theoretical framework underpinning the study. The discussion should be presented in the present tense.

- Interpretation of results -- reiterate the research problem being investigated and compare and contrast the findings with the research questions underlying the study. Did they affirm predicted outcomes or did the data refute it?

- Description of trends, comparison of groups, or relationships among variables -- describe any trends that emerged from your analysis and explain all unanticipated and statistical insignificant findings.

- Discussion of implications – what is the meaning of your results? Highlight key findings based on the overall results and note findings that you believe are important. How have the results helped fill gaps in understanding the research problem?

- Limitations -- describe any limitations or unavoidable bias in your study and, if necessary, note why these limitations did not inhibit effective interpretation of the results.

Conclusion End your study by to summarizing the topic and provide a final comment and assessment of the study.

- Summary of findings – synthesize the answers to your research questions. Do not report any statistical data here; just provide a narrative summary of the key findings and describe what was learned that you did not know before conducting the study.

- Recommendations – if appropriate to the aim of the assignment, tie key findings with policy recommendations or actions to be taken in practice.

- Future research – note the need for future research linked to your study’s limitations or to any remaining gaps in the literature that were not addressed in your study.

Black, Thomas R. Doing Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences: An Integrated Approach to Research Design, Measurement and Statistics . London: Sage, 1999; Gay,L. R. and Peter Airasain. Educational Research: Competencies for Analysis and Applications . 7th edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merril Prentice Hall, 2003; Hector, Anestine. An Overview of Quantitative Research in Composition and TESOL . Department of English, Indiana University of Pennsylvania; Hopkins, Will G. “Quantitative Research Design.” Sportscience 4, 1 (2000); "A Strategy for Writing Up Research Results. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper." Department of Biology. Bates College; Nenty, H. Johnson. "Writing a Quantitative Research Thesis." International Journal of Educational Science 1 (2009): 19-32; Ouyang, Ronghua (John). Basic Inquiry of Quantitative Research . Kennesaw State University.

Strengths of Using Quantitative Methods

Quantitative researchers try to recognize and isolate specific variables contained within the study framework, seek correlation, relationships and causality, and attempt to control the environment in which the data is collected to avoid the risk of variables, other than the one being studied, accounting for the relationships identified.

Among the specific strengths of using quantitative methods to study social science research problems:

- Allows for a broader study, involving a greater number of subjects, and enhancing the generalization of the results;

- Allows for greater objectivity and accuracy of results. Generally, quantitative methods are designed to provide summaries of data that support generalizations about the phenomenon under study. In order to accomplish this, quantitative research usually involves few variables and many cases, and employs prescribed procedures to ensure validity and reliability;

- Applying well established standards means that the research can be replicated, and then analyzed and compared with similar studies;

- You can summarize vast sources of information and make comparisons across categories and over time; and,

- Personal bias can be avoided by keeping a 'distance' from participating subjects and using accepted computational techniques .

Babbie, Earl R. The Practice of Social Research . 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage, 2010; Brians, Craig Leonard et al. Empirical Political Analysis: Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods . 8th ed. Boston, MA: Longman, 2011; McNabb, David E. Research Methods in Public Administration and Nonprofit Management: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches . 2nd ed. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2008; Singh, Kultar. Quantitative Social Research Methods . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2007.

Limitations of Using Quantitative Methods

Quantitative methods presume to have an objective approach to studying research problems, where data is controlled and measured, to address the accumulation of facts, and to determine the causes of behavior. As a consequence, the results of quantitative research may be statistically significant but are often humanly insignificant.

Some specific limitations associated with using quantitative methods to study research problems in the social sciences include:

- Quantitative data is more efficient and able to test hypotheses, but may miss contextual detail;

- Uses a static and rigid approach and so employs an inflexible process of discovery;

- The development of standard questions by researchers can lead to "structural bias" and false representation, where the data actually reflects the view of the researcher instead of the participating subject;

- Results provide less detail on behavior, attitudes, and motivation;

- Researcher may collect a much narrower and sometimes superficial dataset;

- Results are limited as they provide numerical descriptions rather than detailed narrative and generally provide less elaborate accounts of human perception;

- The research is often carried out in an unnatural, artificial environment so that a level of control can be applied to the exercise. This level of control might not normally be in place in the real world thus yielding "laboratory results" as opposed to "real world results"; and,

- Preset answers will not necessarily reflect how people really feel about a subject and, in some cases, might just be the closest match to the preconceived hypothesis.

Research Tip

Finding Examples of How to Apply Different Types of Research Methods

SAGE publications is a major publisher of studies about how to design and conduct research in the social and behavioral sciences. Their SAGE Research Methods Online and Cases database includes contents from books, articles, encyclopedias, handbooks, and videos covering social science research design and methods including the complete Little Green Book Series of Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences and the Little Blue Book Series of Qualitative Research techniques. The database also includes case studies outlining the research methods used in real research projects. This is an excellent source for finding definitions of key terms and descriptions of research design and practice, techniques of data gathering, analysis, and reporting, and information about theories of research [e.g., grounded theory]. The database covers both qualitative and quantitative research methods as well as mixed methods approaches to conducting research.

SAGE Research Methods Online and Cases

- << Previous: Qualitative Methods

- Next: Insiderness >>

- Last Updated: Apr 5, 2024 1:38 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

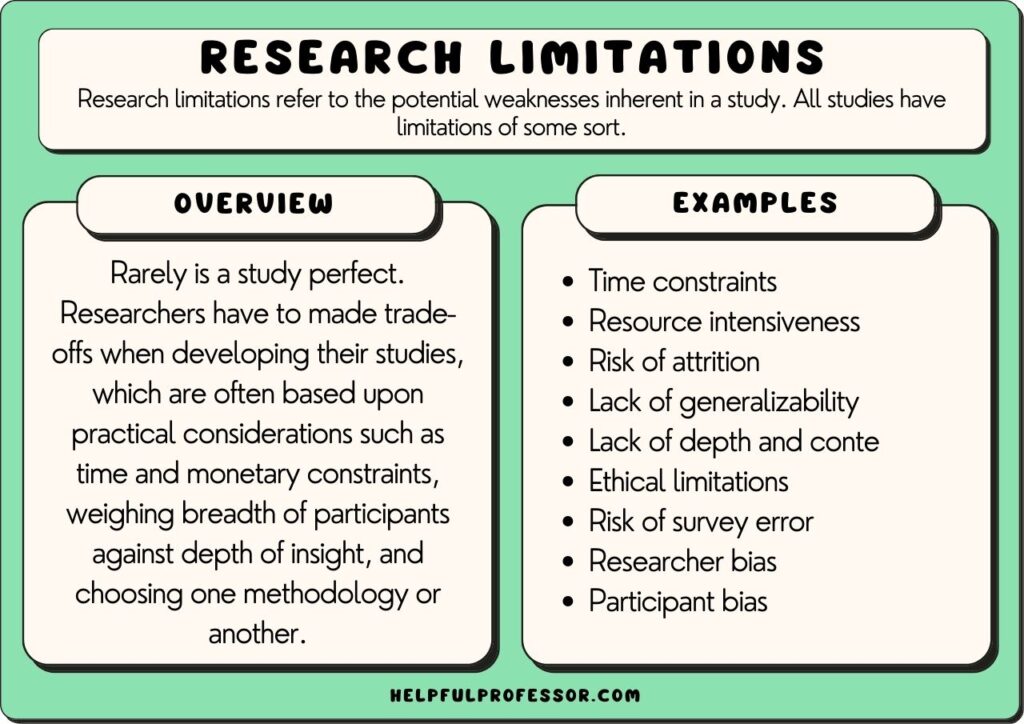

21 Research Limitations Examples

Research limitations refer to the potential weaknesses inherent in a study. All studies have limitations of some sort, meaning declaring limitations doesn’t necessarily need to be a bad thing, so long as your declaration of limitations is well thought-out and explained.

Rarely is a study perfect. Researchers have to make trade-offs when developing their studies, which are often based upon practical considerations such as time and monetary constraints, weighing the breadth of participants against the depth of insight, and choosing one methodology or another.

In research, studies can have limitations such as limited scope, researcher subjectivity, and lack of available research tools.

Acknowledging the limitations of your study should be seen as a strength. It demonstrates your willingness for transparency, humility, and submission to the scientific method and can bolster the integrity of the study. It can also inform future research direction.

Typically, scholars will explore the limitations of their study in either their methodology section, their conclusion section, or both.

Research Limitations Examples

Qualitative and quantitative research offer different perspectives and methods in exploring phenomena, each with its own strengths and limitations. So, I’ve split the limitations examples sections into qualitative and quantitative below.

Qualitative Research Limitations

Qualitative research seeks to understand phenomena in-depth and in context. It focuses on the ‘why’ and ‘how’ questions.

It’s often used to explore new or complex issues, and it provides rich, detailed insights into participants’ experiences, behaviors, and attitudes. However, these strengths also create certain limitations, as explained below.

1. Subjectivity

Qualitative research often requires the researcher to interpret subjective data. One researcher may examine a text and identify different themes or concepts as more dominant than others.

Close qualitative readings of texts are necessarily subjective – and while this may be a limitation, qualitative researchers argue this is the best way to deeply understand everything in context.

Suggested Solution and Response: To minimize subjectivity bias, you could consider cross-checking your own readings of themes and data against other scholars’ readings and interpretations. This may involve giving the raw data to a supervisor or colleague and asking them to code the data separately, then coming together to compare and contrast results.

2. Researcher Bias

The concept of researcher bias is related to, but slightly different from, subjectivity.

Researcher bias refers to the perspectives and opinions you bring with you when doing your research.

For example, a researcher who is explicitly of a certain philosophical or political persuasion may bring that persuasion to bear when interpreting data.

In many scholarly traditions, we will attempt to minimize researcher bias through the utilization of clear procedures that are set out in advance or through the use of statistical analysis tools.

However, in other traditions, such as in postmodern feminist research , declaration of bias is expected, and acknowledgment of bias is seen as a positive because, in those traditions, it is believed that bias cannot be eliminated from research, so instead, it is a matter of integrity to present it upfront.

Suggested Solution and Response: Acknowledge the potential for researcher bias and, depending on your theoretical framework , accept this, or identify procedures you have taken to seek a closer approximation to objectivity in your coding and analysis.

3. Generalizability

If you’re struggling to find a limitation to discuss in your own qualitative research study, then this one is for you: all qualitative research, of all persuasions and perspectives, cannot be generalized.

This is a core feature that sets qualitative data and quantitative data apart.

The point of qualitative data is to select case studies and similarly small corpora and dig deep through in-depth analysis and thick description of data.

Often, this will also mean that you have a non-randomized sample size.

While this is a positive – you’re going to get some really deep, contextualized, interesting insights – it also means that the findings may not be generalizable to a larger population that may not be representative of the small group of people in your study.

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that take a quantitative approach to the question.

4. The Hawthorne Effect

The Hawthorne effect refers to the phenomenon where research participants change their ‘observed behavior’ when they’re aware that they are being observed.

This effect was first identified by Elton Mayo who conducted studies of the effects of various factors ton workers’ productivity. He noticed that no matter what he did – turning up the lights, turning down the lights, etc. – there was an increase in worker outputs compared to prior to the study taking place.

Mayo realized that the mere act of observing the workers made them work harder – his observation was what was changing behavior.

So, if you’re looking for a potential limitation to name for your observational research study , highlight the possible impact of the Hawthorne effect (and how you could reduce your footprint or visibility in order to decrease its likelihood).

Suggested Solution and Response: Highlight ways you have attempted to reduce your footprint while in the field, and guarantee anonymity to your research participants.

5. Replicability

Quantitative research has a great benefit in that the studies are replicable – a researcher can get a similar sample size, duplicate the variables, and re-test a study. But you can’t do that in qualitative research.

Qualitative research relies heavily on context – a specific case study or specific variables that make a certain instance worthy of analysis. As a result, it’s often difficult to re-enter the same setting with the same variables and repeat the study.

Furthermore, the individual researcher’s interpretation is more influential in qualitative research, meaning even if a new researcher enters an environment and makes observations, their observations may be different because subjectivity comes into play much more. This doesn’t make the research bad necessarily (great insights can be made in qualitative research), but it certainly does demonstrate a weakness of qualitative research.

6. Limited Scope

“Limited scope” is perhaps one of the most common limitations listed by researchers – and while this is often a catch-all way of saying, “well, I’m not studying that in this study”, it’s also a valid point.

No study can explore everything related to a topic. At some point, we have to make decisions about what’s included in the study and what is excluded from the study.

So, you could say that a limitation of your study is that it doesn’t look at an extra variable or concept that’s certainly worthy of study but will have to be explored in your next project because this project has a clearly and narrowly defined goal.

Suggested Solution and Response: Be clear about what’s in and out of the study when writing your research question.

7. Time Constraints

This is also a catch-all claim you can make about your research project: that you would have included more people in the study, looked at more variables, and so on. But you’ve got to submit this thing by the end of next semester! You’ve got time constraints.

And time constraints are a recognized reality in all research.

But this means you’ll need to explain how time has limited your decisions. As with “limited scope”, this may mean that you had to study a smaller group of subjects, limit the amount of time you spent in the field, and so forth.

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will build on your current work, possibly as a PhD project.

8. Resource Intensiveness

Qualitative research can be expensive due to the cost of transcription, the involvement of trained researchers, and potential travel for interviews or observations.

So, resource intensiveness is similar to the time constraints concept. If you don’t have the funds, you have to make decisions about which tools to use, which statistical software to employ, and how many research assistants you can dedicate to the study.

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will gain more funding on the back of this ‘ exploratory study ‘.

9. Coding Difficulties

Data analysis in qualitative research often involves coding, which can be subjective and complex, especially when dealing with ambiguous or contradicting data.

After naming this as a limitation in your research, it’s important to explain how you’ve attempted to address this. Some ways to ‘limit the limitation’ include:

- Triangulation: Have 2 other researchers code the data as well and cross-check your results with theirs to identify outliers that may need to be re-examined, debated with the other researchers, or removed altogether.

- Procedure: Use a clear coding procedure to demonstrate reliability in your coding process. I personally use the thematic network analysis method outlined in this academic article by Attride-Stirling (2001).

Suggested Solution and Response: Triangulate your coding findings with colleagues, and follow a thematic network analysis procedure.

10. Risk of Non-Responsiveness

There is always a risk in research that research participants will be unwilling or uncomfortable sharing their genuine thoughts and feelings in the study.

This is particularly true when you’re conducting research on sensitive topics, politicized topics, or topics where the participant is expressing vulnerability .

This is similar to the Hawthorne effect (aka participant bias), where participants change their behaviors in your presence; but it goes a step further, where participants actively hide their true thoughts and feelings from you.

Suggested Solution and Response: One way to manage this is to try to include a wider group of people with the expectation that there will be non-responsiveness from some participants.

11. Risk of Attrition

Attrition refers to the process of losing research participants throughout the study.

This occurs most commonly in longitudinal studies , where a researcher must return to conduct their analysis over spaced periods of time, often over a period of years.

Things happen to people over time – they move overseas, their life experiences change, they get sick, change their minds, and even die. The more time that passes, the greater the risk of attrition.

Suggested Solution and Response: One way to manage this is to try to include a wider group of people with the expectation that there will be attrition over time.

12. Difficulty in Maintaining Confidentiality and Anonymity

Given the detailed nature of qualitative data , ensuring participant anonymity can be challenging.

If you have a sensitive topic in a specific case study, even anonymizing research participants sometimes isn’t enough. People might be able to induce who you’re talking about.

Sometimes, this will mean you have to exclude some interesting data that you collected from your final report. Confidentiality and anonymity come before your findings in research ethics – and this is a necessary limiting factor.

Suggested Solution and Response: Highlight the efforts you have taken to anonymize data, and accept that confidentiality and accountability place extremely important constraints on academic research.

13. Difficulty in Finding Research Participants

A study that looks at a very specific phenomenon or even a specific set of cases within a phenomenon means that the pool of potential research participants can be very low.

Compile on top of this the fact that many people you approach may choose not to participate, and you could end up with a very small corpus of subjects to explore. This may limit your ability to make complete findings, even in a quantitative sense.

You may need to therefore limit your research question and objectives to something more realistic.

Suggested Solution and Response: Highlight that this is going to limit the study’s generalizability significantly.

14. Ethical Limitations

Ethical limitations refer to the things you cannot do based on ethical concerns identified either by yourself or your institution’s ethics review board.

This might include threats to the physical or psychological well-being of your research subjects, the potential of releasing data that could harm a person’s reputation, and so on.

Furthermore, even if your study follows all expected standards of ethics, you still, as an ethical researcher, need to allow a research participant to pull out at any point in time, after which you cannot use their data, which demonstrates an overlap between ethical constraints and participant attrition.

Suggested Solution and Response: Highlight that these ethical limitations are inevitable but important to sustain the integrity of the research.

For more on Qualitative Research, Explore my Qualitative Research Guide

Quantitative Research Limitations

Quantitative research focuses on quantifiable data and statistical, mathematical, or computational techniques. It’s often used to test hypotheses, assess relationships and causality, and generalize findings across larger populations.

Quantitative research is widely respected for its ability to provide reliable, measurable, and generalizable data (if done well!). Its structured methodology has strengths over qualitative research, such as the fact it allows for replication of the study, which underpins the validity of the research.

However, this approach is not without it limitations, explained below.

1. Over-Simplification

Quantitative research is powerful because it allows you to measure and analyze data in a systematic and standardized way. However, one of its limitations is that it can sometimes simplify complex phenomena or situations.

In other words, it might miss the subtleties or nuances of the research subject.

For example, if you’re studying why people choose a particular diet, a quantitative study might identify factors like age, income, or health status. But it might miss other aspects, such as cultural influences or personal beliefs, that can also significantly impact dietary choices.

When writing about this limitation, you can say that your quantitative approach, while providing precise measurements and comparisons, may not capture the full complexity of your subjects of study.

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest a follow-up case study using the same research participants in order to gain additional context and depth.

2. Lack of Context

Another potential issue with quantitative research is that it often focuses on numbers and statistics at the expense of context or qualitative information.

Let’s say you’re studying the effect of classroom size on student performance. You might find that students in smaller classes generally perform better. However, this doesn’t take into account other variables, like teaching style , student motivation, or family support.

When describing this limitation, you might say, “Although our research provides important insights into the relationship between class size and student performance, it does not incorporate the impact of other potentially influential variables. Future research could benefit from a mixed-methods approach that combines quantitative analysis with qualitative insights.”

3. Applicability to Real-World Settings

Oftentimes, experimental research takes place in controlled environments to limit the influence of outside factors.

This control is great for isolation and understanding the specific phenomenon but can limit the applicability or “external validity” of the research to real-world settings.

For example, if you conduct a lab experiment to see how sleep deprivation impacts cognitive performance, the sterile, controlled lab environment might not reflect real-world conditions where people are dealing with multiple stressors.

Therefore, when explaining the limitations of your quantitative study in your methodology section, you could state:

“While our findings provide valuable information about [topic], the controlled conditions of the experiment may not accurately represent real-world scenarios where extraneous variables will exist. As such, the direct applicability of our results to broader contexts may be limited.”

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will engage in real-world observational research, such as ethnographic research.

4. Limited Flexibility

Once a quantitative study is underway, it can be challenging to make changes to it. This is because, unlike in grounded research, you’re putting in place your study in advance, and you can’t make changes part-way through.

Your study design, data collection methods, and analysis techniques need to be decided upon before you start collecting data.

For example, if you are conducting a survey on the impact of social media on teenage mental health, and halfway through, you realize that you should have included a question about their screen time, it’s generally too late to add it.

When discussing this limitation, you could write something like, “The structured nature of our quantitative approach allows for consistent data collection and analysis but also limits our flexibility to adapt and modify the research process in response to emerging insights and ideas.”

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will use mixed-methods or qualitative research methods to gain additional depth of insight.

5. Risk of Survey Error

Surveys are a common tool in quantitative research, but they carry risks of error.

There can be measurement errors (if a question is misunderstood), coverage errors (if some groups aren’t adequately represented), non-response errors (if certain people don’t respond), and sampling errors (if your sample isn’t representative of the population).

For instance, if you’re surveying college students about their study habits , but only daytime students respond because you conduct the survey during the day, your results will be skewed.

In discussing this limitation, you might say, “Despite our best efforts to develop a comprehensive survey, there remains a risk of survey error, including measurement, coverage, non-response, and sampling errors. These could potentially impact the reliability and generalizability of our findings.”

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will use other survey tools to compare and contrast results.

6. Limited Ability to Probe Answers

With quantitative research, you typically can’t ask follow-up questions or delve deeper into participants’ responses like you could in a qualitative interview.

For instance, imagine you are surveying 500 students about study habits in a questionnaire. A respondent might indicate that they study for two hours each night. You might want to follow up by asking them to elaborate on what those study sessions involve or how effective they feel their habits are.

However, quantitative research generally disallows this in the way a qualitative semi-structured interview could.

When discussing this limitation, you might write, “Given the structured nature of our survey, our ability to probe deeper into individual responses is limited. This means we may not fully understand the context or reasoning behind the responses, potentially limiting the depth of our findings.”

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that engage in mixed-method or qualitative methodologies to address the issue from another angle.

7. Reliance on Instruments for Data Collection

In quantitative research, the collection of data heavily relies on instruments like questionnaires, surveys, or machines.

The limitation here is that the data you get is only as good as the instrument you’re using. If the instrument isn’t designed or calibrated well, your data can be flawed.

For instance, if you’re using a questionnaire to study customer satisfaction and the questions are vague, confusing, or biased, the responses may not accurately reflect the customers’ true feelings.

When discussing this limitation, you could say, “Our study depends on the use of questionnaires for data collection. Although we have put significant effort into designing and testing the instrument, it’s possible that inaccuracies or misunderstandings could potentially affect the validity of the data collected.”

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will use different instruments but examine the same variables to triangulate results.

8. Time and Resource Constraints (Specific to Quantitative Research)

Quantitative research can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, especially when dealing with large samples.

It often involves systematic sampling, rigorous design, and sometimes complex statistical analysis.

If resources and time are limited, it can restrict the scale of your research, the techniques you can employ, or the extent of your data analysis.

For example, you may want to conduct a nationwide survey on public opinion about a certain policy. However, due to limited resources, you might only be able to survey people in one city.

When writing about this limitation, you could say, “Given the scope of our research and the resources available, we are limited to conducting our survey within one city, which may not fully represent the nationwide public opinion. Hence, the generalizability of the results may be limited.”

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will have more funding or longer timeframes.

How to Discuss Your Research Limitations

1. in your research proposal and methodology section.

In the research proposal, which will become the methodology section of your dissertation, I would recommend taking the four following steps, in order:

- Be Explicit about your Scope – If you limit the scope of your study in your research question, aims, and objectives, then you can set yourself up well later in the methodology to say that certain questions are “outside the scope of the study.” For example, you may identify the fact that the study doesn’t address a certain variable, but you can follow up by stating that the research question is specifically focused on the variable that you are examining, so this limitation would need to be looked at in future studies.

- Acknowledge the Limitation – Acknowledging the limitations of your study demonstrates reflexivity and humility and can make your research more reliable and valid. It also pre-empts questions the people grading your paper may have, so instead of them down-grading you for your limitations; they will congratulate you on explaining the limitations and how you have addressed them!

- Explain your Decisions – You may have chosen your approach (despite its limitations) for a very specific reason. This might be because your approach remains, on balance, the best one to answer your research question. Or, it might be because of time and monetary constraints that are outside of your control.

- Highlight the Strengths of your Approach – Conclude your limitations section by strongly demonstrating that, despite limitations, you’ve worked hard to minimize the effects of the limitations and that you have chosen your specific approach and methodology because it’s also got some terrific strengths. Name the strengths.

Overall, you’ll want to acknowledge your own limitations but also explain that the limitations don’t detract from the value of your study as it stands.

2. In the Conclusion Section or Chapter

In the conclusion of your study, it is generally expected that you return to a discussion of the study’s limitations. Here, I recommend the following steps:

- Acknowledge issues faced – After completing your study, you will be increasingly aware of issues you may have faced that, if you re-did the study, you may have addressed earlier in order to avoid those issues. Acknowledge these issues as limitations, and frame them as recommendations for subsequent studies.

- Suggest further research – Scholarly research aims to fill gaps in the current literature and knowledge. Having established your expertise through your study, suggest lines of inquiry for future researchers. You could state that your study had certain limitations, and “future studies” can address those limitations.

- Suggest a mixed methods approach – Qualitative and quantitative research each have pros and cons. So, note those ‘cons’ of your approach, then say the next study should approach the topic using the opposite methodology or could approach it using a mixed-methods approach that could achieve the benefits of quantitative studies with the nuanced insights of associated qualitative insights as part of an in-study case-study.

Overall, be clear about both your limitations and how those limitations can inform future studies.

In sum, each type of research method has its own strengths and limitations. Qualitative research excels in exploring depth, context, and complexity, while quantitative research excels in examining breadth, generalizability, and quantifiable measures. Despite their individual limitations, each method contributes unique and valuable insights, and researchers often use them together to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon being studied.

Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative research , 1 (3), 385-405. ( Source )

Atkinson, P., Delamont, S., Cernat, A., Sakshaug, J., & Williams, R. A. (2021). SAGE research methods foundations . London: Sage Publications.

Clark, T., Foster, L., Bryman, A., & Sloan, L. (2021). Bryman’s social research methods . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Köhler, T., Smith, A., & Bhakoo, V. (2022). Templates in qualitative research methods: Origins, limitations, and new directions. Organizational Research Methods , 25 (2), 183-210. ( Source )

Lenger, A. (2019). The rejection of qualitative research methods in economics. Journal of Economic Issues , 53 (4), 946-965. ( Source )

Taherdoost, H. (2022). What are different research approaches? Comprehensive review of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method research, their applications, types, and limitations. Journal of Management Science & Engineering Research , 5 (1), 53-63. ( Source )

Walliman, N. (2021). Research methods: The basics . New York: Routledge.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Limitations in Research – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Limitations in Research – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Limitations in Research

Limitations in research refer to the factors that may affect the results, conclusions , and generalizability of a study. These limitations can arise from various sources, such as the design of the study, the sampling methods used, the measurement tools employed, and the limitations of the data analysis techniques.

Types of Limitations in Research

Types of Limitations in Research are as follows:

Sample Size Limitations

This refers to the size of the group of people or subjects that are being studied. If the sample size is too small, then the results may not be representative of the population being studied. This can lead to a lack of generalizability of the results.

Time Limitations

Time limitations can be a constraint on the research process . This could mean that the study is unable to be conducted for a long enough period of time to observe the long-term effects of an intervention, or to collect enough data to draw accurate conclusions.

Selection Bias

This refers to a type of bias that can occur when the selection of participants in a study is not random. This can lead to a biased sample that is not representative of the population being studied.

Confounding Variables

Confounding variables are factors that can influence the outcome of a study, but are not being measured or controlled for. These can lead to inaccurate conclusions or a lack of clarity in the results.

Measurement Error

This refers to inaccuracies in the measurement of variables, such as using a faulty instrument or scale. This can lead to inaccurate results or a lack of validity in the study.

Ethical Limitations

Ethical limitations refer to the ethical constraints placed on research studies. For example, certain studies may not be allowed to be conducted due to ethical concerns, such as studies that involve harm to participants.

Examples of Limitations in Research

Some Examples of Limitations in Research are as follows:

Research Title: “The Effectiveness of Machine Learning Algorithms in Predicting Customer Behavior”

Limitations:

- The study only considered a limited number of machine learning algorithms and did not explore the effectiveness of other algorithms.

- The study used a specific dataset, which may not be representative of all customer behaviors or demographics.

- The study did not consider the potential ethical implications of using machine learning algorithms in predicting customer behavior.

Research Title: “The Impact of Online Learning on Student Performance in Computer Science Courses”

- The study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have affected the results due to the unique circumstances of remote learning.

- The study only included students from a single university, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other institutions.

- The study did not consider the impact of individual differences, such as prior knowledge or motivation, on student performance in online learning environments.

Research Title: “The Effect of Gamification on User Engagement in Mobile Health Applications”

- The study only tested a specific gamification strategy and did not explore the effectiveness of other gamification techniques.

- The study relied on self-reported measures of user engagement, which may be subject to social desirability bias or measurement errors.

- The study only included a specific demographic group (e.g., young adults) and may not be generalizable to other populations with different preferences or needs.

How to Write Limitations in Research

When writing about the limitations of a research study, it is important to be honest and clear about the potential weaknesses of your work. Here are some tips for writing about limitations in research:

- Identify the limitations: Start by identifying the potential limitations of your research. These may include sample size, selection bias, measurement error, or other issues that could affect the validity and reliability of your findings.

- Be honest and objective: When describing the limitations of your research, be honest and objective. Do not try to minimize or downplay the limitations, but also do not exaggerate them. Be clear and concise in your description of the limitations.

- Provide context: It is important to provide context for the limitations of your research. For example, if your sample size was small, explain why this was the case and how it may have affected your results. Providing context can help readers understand the limitations in a broader context.

- Discuss implications : Discuss the implications of the limitations for your research findings. For example, if there was a selection bias in your sample, explain how this may have affected the generalizability of your findings. This can help readers understand the limitations in terms of their impact on the overall validity of your research.

- Provide suggestions for future research : Finally, provide suggestions for future research that can address the limitations of your study. This can help readers understand how your research fits into the broader field and can provide a roadmap for future studies.

Purpose of Limitations in Research

There are several purposes of limitations in research. Here are some of the most important ones:

- To acknowledge the boundaries of the study : Limitations help to define the scope of the research project and set realistic expectations for the findings. They can help to clarify what the study is not intended to address.

- To identify potential sources of bias: Limitations can help researchers identify potential sources of bias in their research design, data collection, or analysis. This can help to improve the validity and reliability of the findings.

- To provide opportunities for future research: Limitations can highlight areas for future research and suggest avenues for further exploration. This can help to advance knowledge in a particular field.

- To demonstrate transparency and accountability: By acknowledging the limitations of their research, researchers can demonstrate transparency and accountability to their readers, peers, and funders. This can help to build trust and credibility in the research community.

- To encourage critical thinking: Limitations can encourage readers to critically evaluate the study’s findings and consider alternative explanations or interpretations. This can help to promote a more nuanced and sophisticated understanding of the topic under investigation.

When to Write Limitations in Research

Limitations should be included in research when they help to provide a more complete understanding of the study’s results and implications. A limitation is any factor that could potentially impact the accuracy, reliability, or generalizability of the study’s findings.

It is important to identify and discuss limitations in research because doing so helps to ensure that the results are interpreted appropriately and that any conclusions drawn are supported by the available evidence. Limitations can also suggest areas for future research, highlight potential biases or confounding factors that may have affected the results, and provide context for the study’s findings.

Generally, limitations should be discussed in the conclusion section of a research paper or thesis, although they may also be mentioned in other sections, such as the introduction or methods. The specific limitations that are discussed will depend on the nature of the study, the research question being investigated, and the data that was collected.

Examples of limitations that might be discussed in research include sample size limitations, data collection methods, the validity and reliability of measures used, and potential biases or confounding factors that could have affected the results. It is important to note that limitations should not be used as a justification for poor research design or methodology, but rather as a way to enhance the understanding and interpretation of the study’s findings.

Importance of Limitations in Research

Here are some reasons why limitations are important in research:

- Enhances the credibility of research: Limitations highlight the potential weaknesses and threats to validity, which helps readers to understand the scope and boundaries of the study. This improves the credibility of research by acknowledging its limitations and providing a clear picture of what can and cannot be concluded from the study.

- Facilitates replication: By highlighting the limitations, researchers can provide detailed information about the study’s methodology, data collection, and analysis. This information helps other researchers to replicate the study and test the validity of the findings, which enhances the reliability of research.

- Guides future research : Limitations provide insights into areas for future research by identifying gaps or areas that require further investigation. This can help researchers to design more comprehensive and effective studies that build on existing knowledge.

- Provides a balanced view: Limitations help to provide a balanced view of the research by highlighting both strengths and weaknesses. This ensures that readers have a clear understanding of the study’s limitations and can make informed decisions about the generalizability and applicability of the findings.

Advantages of Limitations in Research

Here are some potential advantages of limitations in research:

- Focus : Limitations can help researchers focus their study on a specific area or population, which can make the research more relevant and useful.

- Realism : Limitations can make a study more realistic by reflecting the practical constraints and challenges of conducting research in the real world.

- Innovation : Limitations can spur researchers to be more innovative and creative in their research design and methodology, as they search for ways to work around the limitations.

- Rigor : Limitations can actually increase the rigor and credibility of a study, as researchers are forced to carefully consider the potential sources of bias and error, and address them to the best of their abilities.

- Generalizability : Limitations can actually improve the generalizability of a study by ensuring that it is not overly focused on a specific sample or situation, and that the results can be applied more broadly.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

The Strengths and Limitations of Social Work

- First Online: 15 November 2023

Cite this chapter

- Fiona McDermott ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9362-1441 6 ,

- Kerry Brydon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4373-8112 7 ,

- Alex Haynes 8 &

- Felicity Moon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0317-8598 9

126 Accesses

The focus of this chapter is on describing the strengths of social work in order to present the case for building upon these strengths as social work continues to evolve and adapt in a world at the beginning of the twenty-first century, which has altered in so many ways due to such profound influences as advances in telecommunications and social media, climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic, mass migrations, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, to name just a few. These strengths are explored. This is followed by discussion of some limitations of current social work theorising particularly in relation to ‘wicked problems’; social workers’ responses to risk and uncertainty; the weaknesses of current static or fixed depictions of social reality at micro, meso and macro ‘levels’; and the inability of person-in-environment formulations to explain how exactly person and environment intersect and mutually influence each other. This critique provides the springboard for a discussion of complexity theory, which will be more fully explored in subsequent chapters.

- Social work strengths

- Social work limitations

- Reflective practice

- Social work theory

- Wicked problems

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

AASW. (2020). Code of ethics https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/92

Asquith, S., Clark, C., & Waterhouse, L. (2005). The role of the social worker in the 21st century – A literature review, Edinburgh: Scottish Executive Education Department. Retrieved from: https://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/3000/https://www.gov.scot/Resource/Doc/47121/0020821.pdf

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2022). Social determinants of health . https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/social-determinants-of-health

Cameron, N., & McDermott, F. (2007). Social work and the body . Palgrave Macmillan.

Book Google Scholar

Cree, V., & Wallace, S. (2009). Risk and protection. In R. Adams, L. Dominelli, & M. Payne (Eds.), Practising social work in a complex world (2nd ed., pp. 42–56). Palgrave Macmillan.

Chapter Google Scholar

Davies, M. (1994). The essential social worker: An introduction to professional practice in the 1990s (3rd ed.). Ashgate.

Google Scholar

Dominelli, L. (2002). Anti-oppressive social work theory and practice . Palgrave.

Evans, T., & Hardy, M. (2010). Skills in contemporary social work . Polity Press.

Flack, J., & Mitchell, M. (2020), Uncertain times: The pandemic is an unprecedented opportunity – Seeing human society as a complex systems opens a better future for us all, Aeon Essay . Retrieved from: https://aeon.co/essays/complex-systems-science-allows-us-to-see-new-paths-forward .

Furlong, M. (2013). Building the client’s relational base . The Policy Press.

Gitterman, A., & Germain, C. B. (2008). The life model of social work practice: Advances in knowledge and practice (3rd ed.). Columbia University Press.

Glass, D. (2021). The Ombudsman for human rights: A case book , Melbourne: Victorian Government Printer. Retrieved from: https://assets.ombudsman.vic.gov.au/assets/The-Ombudsman-for-Human-Rights-A-Casebook-Aug-2021.pdf .

Grant, S. (2021). With the falling of dusk . Harper Collins.

Hare, I. (2004). Defining social work for the 21st century: The International Federation of Social Workers revised definition of social work. International Social Work, 47 (3), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872804043973

Article Google Scholar

Howe, D. (2014). The compleat social worker . Palgrave.

International Federation of Social Workers. (2014). Global definition of social work. International Federation of Social Workers. Retrieved from: https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/ .

International Federation of Social Workers. (2018). Global social work statement of ethical principles . https://www.ifsw.org/global-social-work-statement-of-ethical-principles/

Jackson, M. (2019). Critical systems thinking and the management of complexity . Wiley.

McDermott, F. (2014). Complexity theory, transdisciplinary working and reflective practice. In A. Pycroft & C. Bartollas (Eds.), Applying complexity theory . Policy Press.

McDermott, F., Henderson, A., & Quayle, C. (2017). Health social workers’ sources of knowledge for decision making in practice. Social Work in Health Care, 56 , 794. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2017.1340391

Milner, J., Myers, S., & O’Byrne, P. (2020). Assessment in social work (5th ed.). Macmillan Education Ltd.

Payne, M. (2014). Modern social work theory (4th ed.). Lyceum Books.

Peters, B. (2017). What is so wicked about wicked problems? A conceptual analysis and a research program. Policy and Society, 36 (3), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2017.1361633

Rittell, H. W. J. & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4 , 155–169.

Rollins, W. (2019). Social worker-client relationships: Social worker perspectives. Australian Social Work, 73 (4), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2019.1669687

Schon, D. (1992). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action . Routledge.

Scoones, I. (2019). What is uncertainty and why does it matter . STEPS Centre Working Paper 105. Retrieved from: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/14470/STEPSWP_105_Scoones_final.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Smith, J., Puckett, C., & Simon, W. (2016). Indigenous allyship: An overview . Wilfred Laurier University.

Social Determinants of Health. (n.d.). https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/social-determinants-of-health

Termeer, C., Dewulf, A., & Biesbroek, R. (2019). A critical assessment of the wicked problem concept and usefulness for policy science and practice. Policy and Society, 38 (2), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2019.1617971

Warren, K., Franklin, C., & Streeter, C. (1998). New directions in systems theory: Chaos and complexity. Social Work, 43 (4), 357–372.

Watts, L. (2021). Values, beliefs, and attitudes about reflective practice in Australian social work education and practice. Australian Social Work , 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2021.1874031

Wolf-Branigin, M. (2009). Applying complexity and emergence in social work education. Social Work Education, 28 (2), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470802028090

Zajda, J., Majhanovich, S., & Rust, V. (2006). Introduction: Education and social justice. International Review of Education, 52 (1), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-005-5614-2

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Social Work, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing & Health Sciences, School of Primary & Allied Health Care, Monash University, Caulfield East, VIC, Australia

Fiona McDermott

Social Work Practitioner, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Kerry Brydon

Whittlesea Community Connections Inc., Epping, VIC, Australia

Alex Haynes

Emergency Department, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, VIC, Australia

Felicity Moon

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Fiona McDermott .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

McDermott, F., Brydon, K., Haynes, A., Moon, F. (2024). The Strengths and Limitations of Social Work. In: Complexity Theory for Social Work Practice. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38677-0_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38677-0_2

Published : 15 November 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-38676-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-38677-0

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The limitations of social research

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

obscured text

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

Download options.

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station16.cebu on December 10, 2019

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

How to Write Limitations of the Study (with examples)

This blog emphasizes the importance of recognizing and effectively writing about limitations in research. It discusses the types of limitations, their significance, and provides guidelines for writing about them, highlighting their role in advancing scholarly research.

Updated on August 24, 2023

No matter how well thought out, every research endeavor encounters challenges. There is simply no way to predict all possible variances throughout the process.

These uncharted boundaries and abrupt constraints are known as limitations in research . Identifying and acknowledging limitations is crucial for conducting rigorous studies. Limitations provide context and shed light on gaps in the prevailing inquiry and literature.

This article explores the importance of recognizing limitations and discusses how to write them effectively. By interpreting limitations in research and considering prevalent examples, we aim to reframe the perception from shameful mistakes to respectable revelations.

What are limitations in research?

In the clearest terms, research limitations are the practical or theoretical shortcomings of a study that are often outside of the researcher’s control . While these weaknesses limit the generalizability of a study’s conclusions, they also present a foundation for future research.

Sometimes limitations arise from tangible circumstances like time and funding constraints, or equipment and participant availability. Other times the rationale is more obscure and buried within the research design. Common types of limitations and their ramifications include:

- Theoretical: limits the scope, depth, or applicability of a study.

- Methodological: limits the quality, quantity, or diversity of the data.

- Empirical: limits the representativeness, validity, or reliability of the data.

- Analytical: limits the accuracy, completeness, or significance of the findings.

- Ethical: limits the access, consent, or confidentiality of the data.

Regardless of how, when, or why they arise, limitations are a natural part of the research process and should never be ignored . Like all other aspects, they are vital in their own purpose.

Why is identifying limitations important?

Whether to seek acceptance or avoid struggle, humans often instinctively hide flaws and mistakes. Merging this thought process into research by attempting to hide limitations, however, is a bad idea. It has the potential to negate the validity of outcomes and damage the reputation of scholars.

By identifying and addressing limitations throughout a project, researchers strengthen their arguments and curtail the chance of peer censure based on overlooked mistakes. Pointing out these flaws shows an understanding of variable limits and a scrupulous research process.

Showing awareness of and taking responsibility for a project’s boundaries and challenges validates the integrity and transparency of a researcher. It further demonstrates the researchers understand the applicable literature and have thoroughly evaluated their chosen research methods.

Presenting limitations also benefits the readers by providing context for research findings. It guides them to interpret the project’s conclusions only within the scope of very specific conditions. By allowing for an appropriate generalization of the findings that is accurately confined by research boundaries and is not too broad, limitations boost a study’s credibility .

Limitations are true assets to the research process. They highlight opportunities for future research. When researchers identify the limitations of their particular approach to a study question, they enable precise transferability and improve chances for reproducibility.

Simply stating a project’s limitations is not adequate for spurring further research, though. To spark the interest of other researchers, these acknowledgements must come with thorough explanations regarding how the limitations affected the current study and how they can potentially be overcome with amended methods.

How to write limitations

Typically, the information about a study’s limitations is situated either at the beginning of the discussion section to provide context for readers or at the conclusion of the discussion section to acknowledge the need for further research. However, it varies depending upon the target journal or publication guidelines.

Don’t hide your limitations

It is also important to not bury a limitation in the body of the paper unless it has a unique connection to a topic in that section. If so, it needs to be reiterated with the other limitations or at the conclusion of the discussion section. Wherever it is included in the manuscript, ensure that the limitations section is prominently positioned and clearly introduced.

While maintaining transparency by disclosing limitations means taking a comprehensive approach, it is not necessary to discuss everything that could have potentially gone wrong during the research study. If there is no commitment to investigation in the introduction, it is unnecessary to consider the issue a limitation to the research. Wholly consider the term ‘limitations’ and ask, “Did it significantly change or limit the possible outcomes?” Then, qualify the occurrence as either a limitation to include in the current manuscript or as an idea to note for other projects.

Writing limitations

Once the limitations are concretely identified and it is decided where they will be included in the paper, researchers are ready for the writing task. Including only what is pertinent, keeping explanations detailed but concise, and employing the following guidelines is key for crafting valuable limitations:

1) Identify and describe the limitations : Clearly introduce the limitation by classifying its form and specifying its origin. For example:

- An unintentional bias encountered during data collection

- An intentional use of unplanned post-hoc data analysis

2) Explain the implications : Describe how the limitation potentially influences the study’s findings and how the validity and generalizability are subsequently impacted. Provide examples and evidence to support claims of the limitations’ effects without making excuses or exaggerating their impact. Overall, be transparent and objective in presenting the limitations, without undermining the significance of the research.

3) Provide alternative approaches for future studies : Offer specific suggestions for potential improvements or avenues for further investigation. Demonstrate a proactive approach by encouraging future research that addresses the identified gaps and, therefore, expands the knowledge base.

Whether presenting limitations as an individual section within the manuscript or as a subtopic in the discussion area, authors should use clear headings and straightforward language to facilitate readability. There is no need to complicate limitations with jargon, computations, or complex datasets.

Examples of common limitations

Limitations are generally grouped into two categories , methodology and research process .

Methodology limitations

Methodology may include limitations due to:

- Sample size

- Lack of available or reliable data

- Lack of prior research studies on the topic

- Measure used to collect the data

- Self-reported data

The researcher is addressing how the large sample size requires a reassessment of the measures used to collect and analyze the data.

Research process limitations

Limitations during the research process may arise from:

- Access to information

- Longitudinal effects

- Cultural and other biases

- Language fluency

- Time constraints

The author is pointing out that the model’s estimates are based on potentially biased observational studies.

Final thoughts

Successfully proving theories and touting great achievements are only two very narrow goals of scholarly research. The true passion and greatest efforts of researchers comes more in the form of confronting assumptions and exploring the obscure.

In many ways, recognizing and sharing the limitations of a research study both allows for and encourages this type of discovery that continuously pushes research forward. By using limitations to provide a transparent account of the project's boundaries and to contextualize the findings, researchers pave the way for even more robust and impactful research in the future.

Charla Viera, MS

See our "Privacy Policy"

Ensure your structure and ideas are consistent and clearly communicated

Pair your Premium Editing with our add-on service Presubmission Review for an overall assessment of your manuscript.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

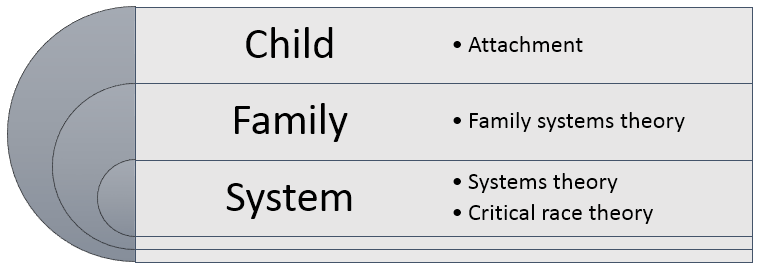

2.2 Paradigms, theories, and how they shape a researcher’s approach

Learning objectives.

- Define paradigm, and describe the significance of paradigms

- Identify and describe the four predominant paradigms found in the social sciences

- Define theory

- Describe the role that theory plays in social work research

The terms paradigm and theory are often used interchangeably in social science, although social scientists do not always agree whether these are identical or distinct concepts. This text makes a clear distinction between the two ideas because thinking about each concept as analytically distinct provides a useful framework for understanding the connections between research methods and social scientific ways of thinking.

Paradigms in social science