- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- March Madness

- AP Top 25 Poll

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Study: Climate change a major factor in South Africa floods

FILE - Floodwaters wash through a property near Durban, South Africa, Tuesday, April 23, 2019. The fatal floods that wreaked havoc in South Africa in mid-April this year have been attributed to climate change, an analysis published Friday, May 13, 2022 by a team of leading climate scientists said.The World Weather Attribution group analyzed both historical and emerging sets of data from the catastrophic rainfall that led to floods which triggered massive landslides in the Eastern Cape and Kwa-Zulu Natal provinces of South Africa. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - The Vishnu Hindu Temple was severely damaged by flooding on Mhlathuzana river in Chatsworth, outside Durban, South Africa, Tuesday, April 12, 2022. The fatal floods that wreaked havoc in South Africa in mid-April this year have been attributed to climate change, an analysis published Friday, May 13, 2022 by a team of leading climate scientists said. The World Weather Attribution group analyzed both historical and emerging sets of data from the catastrophic rainfall that led to floods which triggered massive landslides in the Eastern Cape and Kwa-Zulu Natal provinces of South Africa. (AP Photo, File)

- Copy Link copied

MOMBASA, Kenya (AP) — The fatal floods that wreaked havoc in South Africa in mid-April this year have been attributed to human-caused climate change, a rapid analysis published Friday by a team of leading international scientists said.

The study by the World Weather Attribution group analyzed both historical and emerging sets of weather data relating to the catastrophic rainfall last month, which triggered massive landslides in South Africa’s Eastern Cape and Kwa-Zulu Natal provinces, and concluded that climate change was a contributing factor to the scale of the damage.

“Human-induced climate change contributed largely to this extreme weather event,” Izidine Pinto, a climate analyst at the University of Cape Town and part of the group that conducted the analysis, said. “We need to drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to a new reality where floods and heatwaves are more intense and damaging.”

The scientists said that extreme rainfall episodes like those in April can now be expected about every twenty years, doubling the number of extreme weather events in the region if human-caused climate change had not been a factor. Rainfall is also expected to be about 4 to 8% heavier, the report said.

The floods resulted in the deaths of more than 400 people and severely affected 40,000 others, with thousands now homeless or living in shelters and property damages estimated at $1.5 billion. The floods also led to the shut down of the Port of Durban for several days, disrupting supply chains.

“The flooding of the Port of Durban, where African minerals and crops are shipped worldwide, is also a reminder that there are no borders for climate impacts. What happens in one place can have substantial consequences elsewhere,” said Friederike Otto, a climate researcher at Imperial College in London, who wasn’t part of the study.

The South African weather service’s Vanetia Phakula said that even though the warning systems that are in place to alleviate the most severe impacts on human life issued an early warning on time, the coordination with disaster management agencies had challenges. The report authors noted that those living in marginalized communities or informal settlements were disproportionately affected by the flooding.

Christopher Jack, the deputy director of the Climate System Analysis group at the University of Cape Town, who participated in the study, says the event exposed and magnified the “structural inequalities and vulnerabilities” in the region.

The analysis used long-established and peer-reviewed climate models to account for various levels of sea surface temperatures and global wind circulation among other factors. The results are consistent with accepted links between increased greenhouse gas emissions and greater rainfall intensity, the scientists said. As the atmosphere warms, it’s able to hold more water, making heavy rainfall more likely.

Earlier this year, as the floods were devastating South Africa, the World Weather Attribution group released another rapid assessment analysis on the intensity of cyclones in southern Africa which concluded that human-caused climate change was also largely to blame.

Associated Press climate and environmental coverage receives support from several private foundations. See more about AP’s climate initiative here . The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Why are floods in South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal so devastating? Urban planning expert explains

Full Professor, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Disclosure statement

Hope Magidimisha-Chipungu does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Kwa-Zulu Natal provides funding as a partner of The Conversation AFRICA.

View all partners

The devastation caused by the recent floods in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa demonstrates again that the country is not moving fast enough to adopt appropriate urban planning. It should be integrating risk assessment and management in the design and development of cities. This is becoming more urgent as the frequency of floods increases.

Most South African cities were built a long time ago, before climate change was predicted. KwaZulu-Natal experienced flooding in July 2016, May 2017, October 2017, March 2019, April 2019, November 2019, November 2020, April 2023, June 2023, and now in January 2024. South Africa has a comprehensive national climate change adaptation strategy , and the authorities are aware of flood damage, but are not able to keep up with the repairs.

I recently edited a book on inclusive cities in which I write about the way South Africa has dealt with natural disasters. There is a lack of risk-informed urban planning. This is an approach to designing and developing urban areas with risk in mind. It aims to create resilient cities that can withstand and adapt to various hazards and challenges, such as natural disasters, climate change and social vulnerabilities.

Cities are not resilient

The devastation caused by the recent floods indicates lack of resilience and increasing social vulnerabilities. More than 45 people have died in the last two months ; more than 250 homes have been severely damaged. Severe flooding and landslides caused by heavy rainfall caused the deaths of at least 459 people in April 2022 . These floods displaced over 40,000 people, destroyed over 12,000 houses, and left 45,000 people temporarily unemployed.

The cost of infrastructure and business losses amounted to about US$2 billion. It was one of the worst flooding events in KwaZulu-Natal’s recorded history and eThekwini (Durban) was the worst affected city in the province.

Climate change means more floods are coming

Studies and scientific evidence have pointed to one significant factor contributing to the occurrence of severe flooding: climate change. 2023 was the hottest year ever recorded . The concentration of carbon emissions in the atmosphere has resulted in drastic shifts in weather patterns, leading to increased rainfall in places and subsequent floods.

Read more: South African floods wreaked havoc because people are forced to live in disaster prone areas

In KwaZulu-Natal, the failure to practise risk-informed urban planning has left the province’s roads and buildings, often poorly designed, crumbling. The authorities have failed to maintain drainage systems. They have not put in place flood control measures, such as river channelisation. This is where rivers are dredged, widened and deepened to improve their flow capacity and reduce the risk of flooding.

Flood retention basins, designed to temporarily store excess water during heavy rainfall or flooding events, would also reduce the risk of downstream flooding. Neglecting to put these measures in place contributes to severe flooding and endangers the safety of communities.

Inadequate waste collection and inappropriate disposal of garbage also blocks the drains, worsening the impact of heavy rainfall. Poor drainage systems are clogged with plastic pollution. Robust waste management systems are needed to ensure that water flows properly through these drains.

Read more: How cities can approach redesigning informal settlements after disasters

In some cases, inappropriate land use and the unchecked expansion of urban areas into flood-prone zones have resulted in increased vulnerability to extreme weather. Strong enforcement of land use policies that restrict development in high-risk areas is essential. Municipalities such as the disaster-hit city of eThekwini in KwaZulu-Natal must not allow people to build in flood-prone areas, because once people settle in an area it becomes expensive to relocate them.

What are the solutions?

Frequent flooding in KwaZulu-Natal will be the new reality. The province urgently needs a comprehensive approach, one that involves the local community in decision-making around urban planning and climate change mitigation. An inclusive approach would recognise local knowledge and encourage innovative solutions suitable for the area.

Prioritising mixed-use development, density, and the preservation of green spaces in city zoning and land-use regulations is essential. Urban sprawl must be curbed. The government must establish compact, walkable neighbourhoods that are not constructed on floodplains, coastal zones, or low-lying areas. By recognising areas of high risk, the damage caused by flooding can be minimised.

Water-sensitive urban design must be encouraged as soon as possible. This includes green roofs and permeable pavements, which allow water to pass through the surface layer and be stored or infiltrated into the underlying soil layers.

More parks, urban forests and other green spaces must be established in cities and towns. They serve as carbon sinks: places that store carbon dioxide, acting as natural reservoirs, and regulating the balance of greenhouse gases. Wetlands, riparian zones and forests must be preserved because they can act as natural buffers against flooding, absorbing excess water and reducing the impact on nearby urban areas.

Developing an efficient network of stormwater drains, sewers and retention ponds to control the flow of water during heavy rainfall events is vital. This infrastructure should be regularly maintained and updated.

The province needs to move towards climate change adaptation. Public awareness and education campaigns on the importance of flood-resistant measures will foster a sense of responsibility in preventing flooding.

The authorities must collaborate with other cities that face similar problems. Nations like Japan , which efficiently manages natural disasters, offer useful examples we could follow.

- Climate change

- Climate change adaptation

- Green roofs

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Senior Disability Services Advisor

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

GRAINS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHAIRPERSON

Advertisement

Flooding trends and their impacts on coastal communities of Western Cape Province, South Africa

- Published: 25 June 2021

- Volume 87 , pages 453–468, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Kaitano Dube ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7482-3945 1 ,

- Godwell Nhamo 2 &

- David Chikodzi 2

24k Accesses

35 Citations

22 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Climate change-induced extreme weather events have been at their worst increase in the past decade (2010–2020) across Africa and globally. This has proved disruptive to global socio-economic activities. One of the challenges that has been faced in this regard is the increased coastal flooding of cities. This study examined the trends and impacts of coastal flooding in the Western Cape province of South Africa. Making use of archival climate data and primary data from key informants and field observations, it emerged that there is a statistically significant increase in the frequency of flooding and consequent human and economic losses from such in the coastal cities of the province. Flooding in urban areas of the Western Cape is a factor of human and natural factors ranging from extreme rainfall, usually caused by persistent cut off-lows, midlatitude cyclones, cold fronts and intense storms. Such floods become compounded by poor drainage caused by vegetative overgrowth on waterways and land pollution that can be traced to poor drainage maintenance. Clogging of waterways and drainage systems enhances the risk of flooding. Increased urbanisation, overpopulation in some areas and non-adherence to environmental laws results in both the affluent and poor settling on vulnerable ecosystems. These include coastal areas, estuaries, and waterways, and this worsens the risk of flooding. The study recommends a comprehensive approach to deal with factors that increase the risk of flooding as informed by the provisions of both the Sustainable Development Goals framework and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 in a bid to de-risking human settlement in South Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Externalities of Climate Change on Urban Flooding of Agartala City, India

Flood risk and adaptation in Indian coastal cities: recent scenarios

Ravinder Dhiman, Renjith VishnuRadhan, … Arun Inamdar

Causes and Management of Damaging Flood Incidences in Rapidly Urbanizing Areas of Kathmandu Valley: A Case Study of Flood Event in Bhaktapur District, Nepal

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The world over, many people are resident in coastal areas. The romantic connection between humanity and coastal communities has a long history dating back to the pre-civilisation era. According to Hallegatte et al. ( 2013 ), coastal cities are witnessing an increase in the frequency, intensity and impact of coastal flooding. The cost of flooding can be attributed to several factors such as rapid urbanisation, the increased construction and installation of other assets along the coastal line and climate change (Amoako & Frimpong Boamah, 2015 ; Dhiman et al., 2019 ). Chan ( 2018 ) argue that hydrological hazards faced by coastal cities emanate from a combination of factors such as uncontrolled urban development, climate change, and sea level rise.

Climate change has ushered in a new era of challenges for coastal towns and cities. These areas experience nature’s backlash in the form of intense rainfall, sea level rise, in some instances, tropical cyclones and increasing tidal activity and storm surges (Dube et al., 2020a , 2020b ). The increasing incidence of extreme weather events is worrying as it presents complex challenges for coastal communities' socio-economic development. According to Ogie et al. ( 2018 ), critical coastal infrastructure such as pumps, flood gates, and embankments are particularly vulnerable to increased floods. In addition, transport networks remain vulnerable to coastal flooding (Duy et al., 2019 ). This is likely to threaten the achievement of the global inclusive Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that are set to be achieved in 2030 (United Nations, 2015 ).

There is, therefore, a growing consensus and worry that coastal areas are increasingly becoming global hotspots for climate change-induced extreme weather disasters (Chan et al., 2018 ). Balica et al. ( 2012 ) indicate the need to enhance understanding of global vulnerability by explicitly focusing on coastal flooding, which is becoming more common and problematic across the world. Regardless of coastal flooding's recognition as a significant challenge to most areas, the knowledge of the actual extent of climate change risk to coastal areas remains a challenge to most areas in Africa (Kithiia, 2011 ). As a consequence, addressing flood resilience in that context is problematic. According to Handayani et al. ( 2019 ), resilience-building must be a key focus in ensuring coastal areas’ sustainability in the wake of climate change. In light of this call, this study examines and documents the trends and impacts of flooding in the coastal province of Western Cape, South Africa. Although the principal aim of the study is to examine trends and impact of floods in the Western Cape province in general, the main focus will be on urban areas where the greatest socio-econimic impacts occur. Two critical research questions are raised: (1) What has been the long-term flood occurrence in the Western Cape province? (2) What has been the socio-economic impact of these floods on the Western Cape province?.

Literature survey

Extreme weather events remain among the global challenges that both inland and coastal communities must contend with in the quest to ensure sustainable development. Apart from the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had a devastating impact on global economies in 2020 (Nhamo et al., 2020 ), climate change is a wicked problem that the world must battle with going forward if development target aspirations are to be met. The challenge of extreme weather events is particularly pronounced and felt by most developing countries, which still lack the means for adaptation or maladapt (Leal Filho, 2018 , 2019 ; Mirza, 2003 ). In most cases, there is a clear link between communities’ income levels and adaptive capacity. By nature, adaptation requires that nations and states invest more resources into climate change resilience initiatives. Experience has often shown that such resources are often not available for most developing countries, even for basic needs. Therefore, it is anticipated that climate change will likely worsen marginalised communities’ poverty levels due to the impacts pf extreme weather events and costs associated with the damage.

One of the impacts of extreme weather events that has caused challenges for development agencies and planners is the issue of flooding in coastal urban spaces. Besides flooding (a process of submerging of land that is usual dry by overflowing water), coastal communities must battle with other climate change induced challenges such as sea level rise, coastal erosion, ocean pollution, rising sea surface temperature, coral bleaching and severe droughts (IPCC, 2019 ). These coastal challenges have disturbed coastal communities' lives and livelihoods with far-reaching implications for inland communities, which often depends on coastal areas for recreation, food, and other critical supplies. This presents severe challenges for coastal urban communities in Sub-Saharan Africa, where coastal areas are also battling the challenges caused by rapid urbanisation (Cian et al., 2019 ; Dodman et al., 2017 ).

Cities and communities in Southern and Eastern Africa have not been spared from climate change-related hazards, with many cities battling flooding. A study by Braccio ( 2014 ) reveals that in Maputo, a coastal city in Mozambique, there have been increasing incidences of flooding due to the compounded impact of rising sea levels and intense rainfall activity attributed to climate change. As Kabanda ( 2020 ) finds, Mombasa's vulnerability in Kenya due to rising sea level has placed infrastructure such as roads and buildings under flood threat. On the other hand, the threat of flooding in South Africa’s coastal areas is not well documented, with very few studies focussing on the issue (see, for example, Fitchett et al., 2016 ; Dalu et al., 2018 ). This is also the picture across many other places in Southern Africa. Consequently, there are fears that this will curtail the adoption of adequate adaptation and resilience measures.

Despite fears by communities and preliminary evidence of the catastrophic impact of floods in coastal areas there has been little effort to adequately address this challenge. According to Fitchett et al. ( 2016 ), the challenge of coastal flooding is a real perceived threat by tourism businesses operating in the coastal towns of the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. In another study, Dalu et al. ( 2018 ) found that informal settlements that were located on high slopes, degraded slopes and those close to drainage channels were likely to experience significant damages from flooding. This raises concerns as to the impact of such shocks on vulnerable groups and their capacity to recover and adapt from such threats.

Cape Town, which is located in the Western Cape, has not been immune to flooding. Taylor and Davies ( 2019 ) note that the city of Cape Town, the 10th most populous city in Africa often suffers from the impacts of flooding with a devastating impact on railway lines, parking lanes, roads, and power supply and communication infrastructure. Fears are also rife that these impacts will worsen due to climate change induced sea level rise in the city and other areas surrounding it (Dube et al., 2021 ). Due to increased urbanisation, stormwater is also presenting unique challenges for the City of Cape Town (Taylor, 2019 ). Climate change studies have established that there are also fears that with the increased frequency and incidence of the El Niño‐Southern Oscillation in the Southern Hemisphere, there is an anticipation that this will likely see an increased frequency in coastal flooding. Rasmusson and Wallace ( 1983 ), established that the El Niño‐Southern Oscillation is closely linked to sea levels’ variability, which can worsen sea level rise and lead to increased coastal flooding.

Western Cape is one of the most urbanised communities and one of the most unequal societies in South Africa (Gwaze et al., 2018 ). As such the threat of flooding affects different communities differently, with the marginalised communities bearing the brunt of such events. The recent drought in Cape Town exposed the vulnerabilities along these economic and social lines (Enqvist & Ziervogel, 2019 ). Given past experiences, droughts require attention as they often result in mass displacements, which undermines peoples’ livelihood security and infrastructural damage (Dube & Nhamo, 2020a , 2020b ). The devastating impacts of floods were also witnessed in 2019 in Mozambique and other Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries in the wake of Tropical Cyclones Idai and Kenneth (Phiri et al., 2020 ). There is therefore a need for a thorough understanding of flood occurrences and associated risks. Such an undertsnading is more critical now than ever before to allow communities to build resilience and adopt risk reduction measures. In as much as single cases of flood events are documented, there is no study in the SADC area that looks at the long-term trends of floods. Hence, this study examines and documents the trends and impact of floods that have occurred in the Western Cape over the last 120 years. The study seeks to understand flood frequency and its impact on the community, development, and society at large.

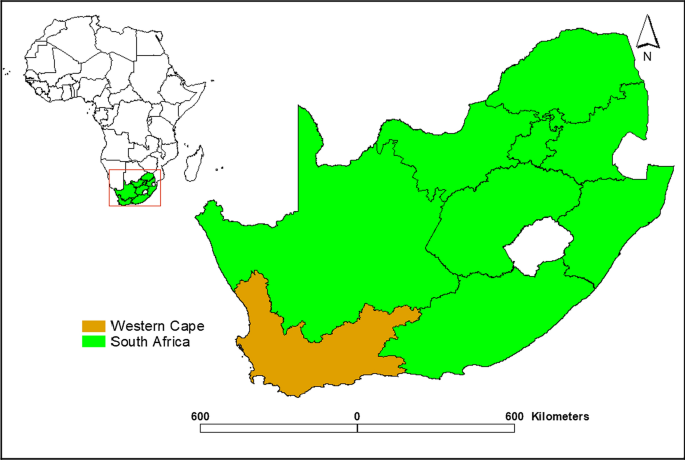

Research design

The Western Cape Province is an area located on the southernmost part of South Africa and the African continent (Fig. 1 ). It is the same place that is home to the populous city of Cape Town and the iconic Table Mountain (Dube et al., 2020a , 2020b ). The province lies between coastlines from two oceans namely: the Indian Ocean on the east and the Atlantic Ocean on the west coast. The two oceans separate at the Cape Agulhas. The province has a predominantly Mediterranean climate that is typified by warm and mostly dry summers and cold wet winters. The two oceans play a critical role in shaping the climatic and weather patterns of the area. The Western Cape Province has been in the news for the devastating impacts of extreme weather events, particularly the recent drought of 2017/18 that threatened the water supply system of one of South Africa’s most populous cities and tourism destinations (Dube et al., 2020a , 2020b ). The City of Cape Town and other places in the Western Cape Province are well known for their vulnerability to extreme weather events, with the City of Cape Town often dubbed the “Cape of Storms” by many of its citizens. Rouault, ( 2002 ) notes that the Agulhas Current, whose location is the east coast of South Africa, with a bearing on and off the Eastern and Western Cape coast, is partly responsible for severe weather events in the province.

Source : Authors

Location of Western Cape Province in relation to South Africa and Africa

In Western Cape latent heat fluxes often causes low-level advection of moisture, which in turn causes the intensification of storms and tornadoes, causing flooding. Stramma and Lutjeharms ( 1997 ) noted that the Agulhas Current is one of the most intense western current boundaries in the Southern Hemisphere, and White ( 2000 ) observed two such severe storms during 1998/99 summer on the Agulhas Current. According to Mukheibir and Ziervogel ( 2007 ), the March 2003 and April 2005 intense storms and flooding were reported in Cape Town and the Western Cape province.

A case study research approach was adopted for this study. The study utilised data obtained from the South African Weather Services’ (SAWS) archives for the period 1900 to 2018. Additional data were obtained from field observations and key informant interviews from various Western Cape admimisttrative districts that took place between February and December 2020. A snow ball sampling technique was followed in the selection of 15 key informants, which formed part of the study. Key informants comprised of staff from the City of Cape Town that included planners, environmental engineers, museum curators, protected area personnel, tradtional community leaders and climate experts from the province. Such key informant interviews took between 45 and 60 min. Questions for key infrmants centered on documenting the climate history of the area, experiences with the floods, possible causes and possible solutions to flooding among other key questions pertinent to the study. The use of key informants interviews is an acceptable standard, methodological approach, which has been used in previous similar studies by Lo et al. (2017) and Twongyirwe et al. (2018). The approach can yield valid results and allows researchers to collect high quality data within a short period of time from fewer people in a cost effective manner. This methodological approach also addreses the constraints posed by the COVID-19 pandemic of ensuring phsycical and social distancing as it minimised contact with a lot of people. SAWS is one of the most resourced meteorological organisations in terms of weather stations that boasts a wide array of weather and climate equipment networks (Fig. 2 ).

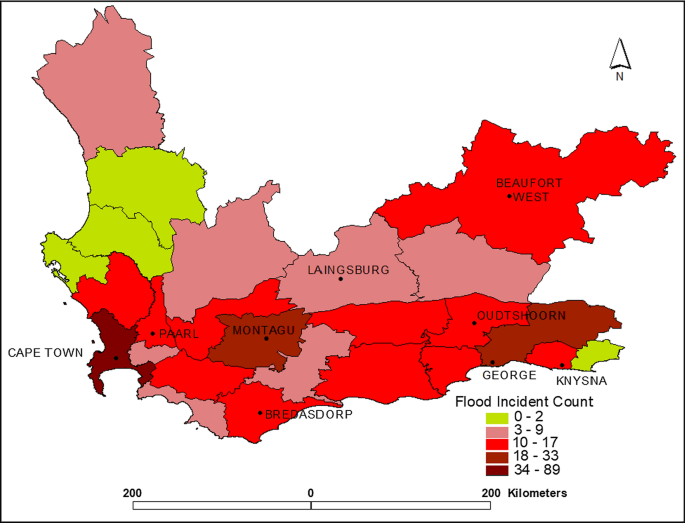

Some Key assets utilised by South African Weather Services

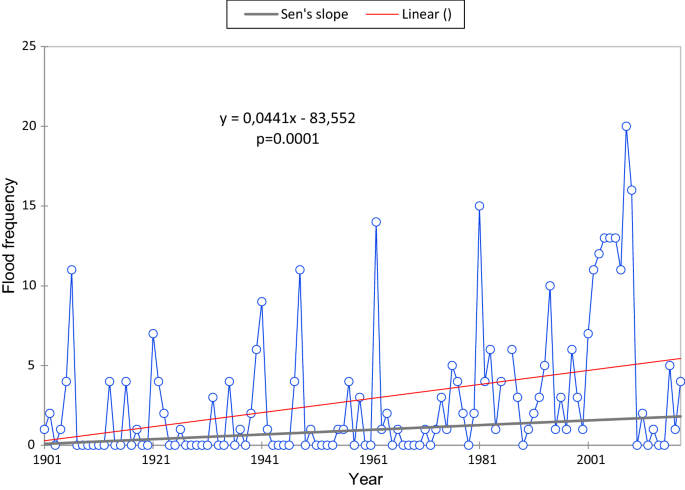

Data analysis was conducted using XLSTAT 2020.5.1 that was run on a Microsoft Excel sheet. A time series was analysed using the Mann–Kendall trend test to determine the presence of trends. The Confidence interval was set at 95%, and the Significance level was set at 5%. The Mann- Kendall trend test was also used to plot the Sen’s Slope. The Mann–Kendall trend test is a commonly used parametric tool used in climate and hydrological studies that enjoys wide usage and has been used in similar studies by other scholars (Hamed, 2008 ; Hu et al., 2020 ). Choropleth maps showing flood hotspots in the study area were produced in a Geographic Information System using flood incident count at local municipality level as a measure. Frequently flooded areas were denoted by increasing the colour intensity on the map. Primary and secondary qualitative data was analysed using content and thematic analysis.

Results and discussion

The study found that between 1900 and 2018, at least 334 major flood events occurred in the Western Cape, with a mean annual number of floods being 2.9. The highest number of annual flood events over the period of study is 20, which occurred in 2008. The second-highest number of flood events were recorded in 1981, where 15 floods were recorded. The third-highest flood years were recorded in 2004, 2005 and 2006, where 13 floods were recorded in each year. Consequently, the frequency of floods has been higher during the past four decades as compared to earlier periods (Fig. 3 ). In the first half-century, the average number of floods was at less than two flood events per year in the province, with the last century having peaked up to slightly more than four flood events per year. Figure 3 shows that there is a statistically significant ( p = 0.0001, α = 0.5) increase in the number of flooding events occurring in Western Cape province over the period of study.

Source : Authors, Data from SAWS (2020)

Flooding frequency and trends in Western Cape province 1900–2018

The observed increase in coastal flooding in the Western Cape Province in Fig. 3 confirms earlier findings in other parts of the world where coastal flooding is on the increase due to extreme weather events induced by climate change and other urban challenges as reported by Hirabayashi, ( 2013 ) and also Kim, ( 2017 ). One of the critical drivers of coastal flooding in Western Cape Province is high sea tides and intense rainfall activity. A study by Dube et al. ( 2021 ) found that some of the recent floodings observed in the City of Cape Town, for example, were worsened by sea level rise confirming earlier findings by Park and Lee ( 2020 ). Flooding in the Western Cape Province is worrying as it has far reaching socio-economic impacts on one of the most urbanised provinces and areas in the entire Southern Africa.

The study found that flooding was mainly concentrated in the areas close to the coast, with the highest flood prevalence concentrated around the City of Cape Town and areas that are to the east of the province (Fig. 4 ). Areas to the South East of the Cape Winelands district and areas to the South of the Cape Winelands seems to be most affected by the number of floods, whereas central Eden also experiences the highest number of floods. In the Cape Winelands District, the areas between Montagu and Ashton town are also considerably affected by flooding. The area which lies along the R62 road is prone to flooding due to several factors. The interviews were conducted with key informants where it was revealed that the area is susceptible to flooding due to its mountainous terrain with water being channelled towards a mountain gorge which the R62 road runs through. Other flood hotspots include areas near South East coastal areas of Overberg District east of Cape Agulhas near Strus Bay. In the Garden route area, areas around Plettenberg Bay were identified as flooding hotspots. From Fig. 4 it emerges that floods tend to be concentrated along the coastline. However, by and large, the West Coast and Central Karoo areas are not as affected due to semi-arid and desert conditions that prevail, with flush floods occurring once in a while.

Flood count and risk analysis map of Western Cape province between 1900 and 2018

Information gathered from the key informants revealed that heavy rainfall along the Kogmanskloof Mountain Pass along the R62 road often results in flooding in areas around the pass. Based on evidence from the Western Cape Provincial Government report and key informants in the area, one of the most memorable floods in the area is the Montagu flood of March 2003 which went on to be declared a national disaster. The record flood occurred as a consequence of a cut-off low that resulted in the Montagu area receiving 178 mm of rainfall in 1 day on the 23rd of March 2003. The total monthly rainfall for that month went up to 241 mm, which became one of the wettest days in the history of the area. That particular flood event damaged roads, factories in Ashton town, farms, schools and had a huge impact on tourism. The De Hoop Nature Reserve’s main road was washed away, and Goukamma Nature Reserve access road was also badly damaged in a development that costed Cape Nature more than R1 million. The traditional leadership in the area fears that the flood event and other subsequent floods washed away several archaeological artefacts from the Khoisan San community in mountains in the area leading to a loss of important historical heritage. The flood also had an adverse impact on the Klein Karoo Arts Festival as the area was declared a disaster zone because of that flood event. The access road between Ashton and Montagu was disrupted just in time for the festival cutting off tourist access.

Field observations and information from key informants revealed that given a significantly large basin and water channelled from mountain zones, flood risk is also high in that area. Another factor that promotes occasional floods is that the area seems to be experiencing successive years of flooding and drought, given its geographic location, which is transitional to the central Karoo, which is semi-desert. Pollution from urban and farming activities in the catchment further promotes the heavy growth of weeds within the Kogmanskloofrivier river. This reduces the rate of water outflow from the area and ultimately increases the risk of flooding in the area.

It emerged during fieldwork that the government is working on upgrading road infrastructure in the area so as to mitigate the increased impact of flooding on human settlements and infrastructure. The infrastructure includes elevating the road and making bigger elevated bridges to allow for more water to flow at any given time without causing flooding. The bridge in Ashton town, for example, was being upgraded to allow more water flow. It remains to be seen how such upgrades will limit the disruptions caused by floods to Montagu and Ashton town’s two communities.

Socio-economic impact of floods in Western Cape

It emerged from the SAWS records, damages induced by flooding in the Western Cape ranged from infrastructure (roads, bridges, and rail lines), loss of properties, homes, damages to vineyards, damages to informal settlements, and injury and loss of human lives. In as much as the increased socio-economic and human cost can be tracked back to increased frequency of flooding events, increased urbanisation and affluence has over the years worsened this phenomenon.

Table 1 shows some of the most significant and high impact floods that have been witnessed in the Western Cape between 1901 and 2018. The flooding incidences recorded in various places in the Western Cape show that the flooding events in the province have led to the death of more than 129 people across province. There were very few deaths witnessed before 1980, with only three fatalities attributed to floods. The single highest number of fatalities were recorded in 1981 when a staggering 104 people were killed in a single incident by a raging flood that wiped away almost the entire small town of Laingsburg. On 25 January 1981, a cloud outburst caused one of the greatest floods in the Great Karoo. Given the geohydrological makeup of the area, where the soil cannot absorb much water, the cloud outburst resulted in a 6 m high flood after the Baviaans and Buffels rivers. The two rivers have their confluence in the town, and they bursted their banks, destroying 185 houses and 23 businesses.

That flooding incident went on to be labelled as one of the worst natural disasters in South Africa. In addition to the destruction of properties and businesses, the flood led to the washing away of animals and the town’s tourism infrastructure. During this 1 in 100 year flood incident, the Great Trek Monument, which is an important Dutch historical monument, which was constructed in 1938, was washed away. While the greater part of the monument was recovered after the flood, the monument’s pedestal was lost and was only found after another flood in June 2015. The impacts of floods are well documented, which have played both a positive and negative role in heritage properties (Liu, 2019 ; Reimann, 2018 ). While floods destroyed the monument, they also created another historical monument. Post the flood a Flood Museum was constructed in the same town.

It would appear from key informants’ accounts that the 1981 Laingsburg natural disaster was partial caused settlements that were established without proper risk analysis and consideration. Settlements, which are established without a proper risk assessment in the form of environmental impact assessment remain a worry across the country. This is particularly so, given the additional vulnerabilities induced by climate change-induced weather extreme events. Climate change-induced extreme weather events have the potential to amplify natural events, including rainfall patterns and intensity. Field observation revealed that even after the disaster, a look at the area shows that human development, including commercial infrastructures such as hotels, lodges, restaurants, and a hospital, is still located in flood zone. The adjustment to address the risk is crucial to current and future urban sustainability as part of disaster risk reduction. In that vein, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, particularly the Sustainable Development Goal Target 11.5, seeks to reduce the number of fatalities and economic losses relative to the gross domestic product caused by disasters, focusing on the poor (United Nations, 2015 ). Similar aspirations are encompassed in the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2015 ).

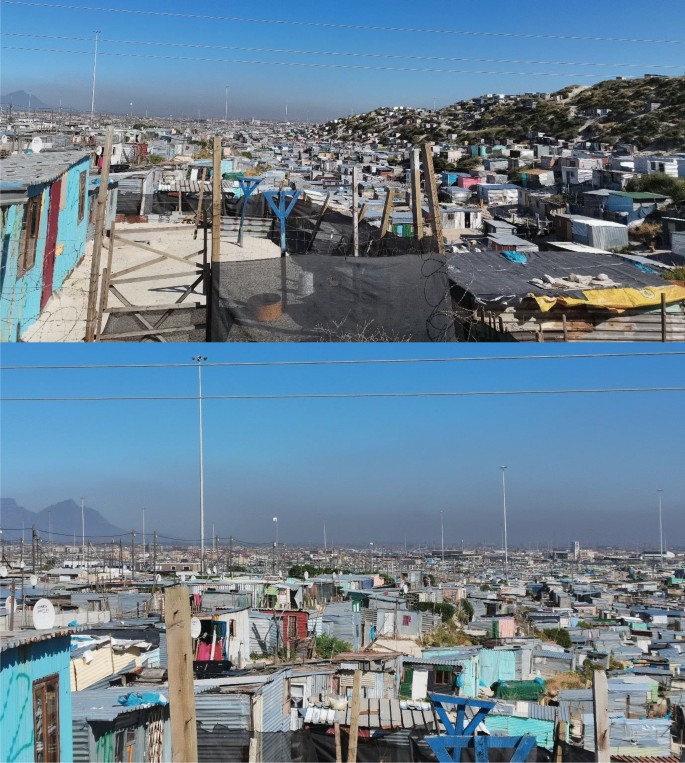

The Western Cape Province case study reveals that flood risks in urban areas are on the increase. Such risks primarily affect the poor. Extreme weather events such as floods often destroys homes and livelihoods. Evidence from the study reveals that flooding has in the past destroyed several shacks and homes. The worst affected areas in the past have been areas around George, Cape Town, Hermanus, Cape Flats and Khayelitsha. Apart from the Western Cape Province, similar observations have been made elsewhere in African states and other developing states that are located in coastal areas. Some of the affected areas includes Manila, Philippines (Zoleta-Nantes, 2002 ), Nigeria, (Adelekan, 2010 ; Echendu, 2020 ) and China (Jiang et al., 2018 ).

According to Douglas ( 2008 ) and Douglas ( 2017 ), the unjust water and climate are flooding the poor along with the coastal towns in Africa. The situation can be attributed to increasing urban poverty and rapid urbanisation and urban sprawl that has left many condemned to a life of squalor. Most urban councils in the coastal Western Cape and, in many respects, other urban areas in South Africa are failing to meet the demands of an ever-increasing housing backlog. Consequently, most urban migrants are settled in informal settlements where the settlements are unplanned and often in disaster-prone areas such as waterways and, in some instances, fragile ecosystems prone to flooding and other disasters. In Cape Town, for example, field observations revealed that the mushrooming of informal settlements magnified by the ongoing land grabs in the Cape Flats resulted in many building houses on waterways and fragile ocean sand dunes in densely populated areas, which exposed thousands to flood and fire disasters (Fig. 5 ). Therefore, it is not surprising that the City of Cape Town has witnessed increased incidences and cost of residents' displacement and property loss due to the combined effect of extreme weather events, urban sprawl and invasion of disaster areas by city dwellers.

Source : Authors, Fieldwork 2020

Informal settlement built on unstable dunes and waterway in Khayelitsha, Cape Town

The debate of flooding and climate change becomes central, as flooding disasters are driving many people around the globe into poverty. This sentiment is shared by Jordhus-Lier et al. ( 2019 ), who noted that the City of Cape Town flooding is a growing concern that requires focus and attention by developing climate change adaptation. In doing so, there is a need to address factors that induce vulnerabilities. According to Ribot ( 2014 ), addressing vulnerabilities requires an approach that considers the root causes of the crises so that transformative solutions can be found, often lacking in climate change adaptation studies. In this regard, addressing vulnerabilities must consider various matrices at play. These include climatic factors and factors that push people into settling in eco-sensitive areas and waterways and considering aspects that deal with rapid rural to urban migration. Finally, dealing with aspects of refuse waste and drainage clogging in many urban setups in the Western Cape and across the country. In recent years, urban inequality has featured storngly in the mix, with politics playing a central role in urban settlement issues, resulting in wanton settlement development and land grabs, in some instances in areas that are not suitable for settlement.

A recent study by Dube et al. ( 2020a , 2020b ) noted that flooding in Cape Town was not only a factor of poverty as the affluent were also being hit hard by the compounded effect of sea-level rise and intense storm activity in the coastal city. Addressing vulnerabilities is, therefore, a wicked problem that requires a holistic approach. It is common knowledge that climate change, apart from civil unrest and wars that ravage the continent, is one of the contributory factors and drivers of rural poverty, which drives rural to urban migration. Therefore, addressing sustainability becomes a complex issue that requires the reconfiguration of governance systems to ensure urban transformation in line with the aspirations of SDG11 as espoused by Patel ( 2017 ).

Besides the City of Cape Town, other coastal urban areas have been threatened by floodings, such as George and Hermanus. There are also other important tourist resort towns where millions of rand worth of property have been damaged. The floods have been blamed for the destruction of tourism infrastructure, often located in pristine areas close to nature. Floods in the Western Cape have often cut off routes to some of the province's tourism destinations, such as Agulhas National Park, where the primary link road becomes flooded during intense rainfall as the road runs through a significant wetland area. Flooding, therefore, undermines economic activities in the province. Figure 6 shows the damage which occurred in May 2005 on the R43 highway, which links Hermanus to Stanford.

Source : Overstrand Municipality

Impacts of severe flooding in Hermanus on transport infrastructure.

Looking at the global scale, addressing global warming that leads to climate change, and in turn, weather extreme events, in this case, the threat of flooding, will require both local and national governments to embrace climate change mitigation strategies. This, therefore, demands implementing measures aimed at reducing the carbon footprint of the province and all its metros. The province has an obligation to reduce its emissions under the Paris Agreement, and one way of doing this is an investment in clean energy such as wind and solar, which requires an investment in energy efficiency technologies. Investment in clean energy should address challenges of energy, climate change and unemployment in the province. One of the ways of decreasing disaster vulnerability in Africa is through the addressing of poverty and inequality.

SDG 16 Target 16.3 speaks about the need to ensure the rule of law. This is a critical issue with regards to developing a sustainable urban community within the province of the Western Cape. One of the challenges faced by urban areas in South Africa is non-adherence to city by-laws and national legislative provisions, with environmental laws often being flouted for political expediency. Strict adherence to environmental laws and enforcement of environmental laws can ensure that people do not settle in fragile and eco-sensitive areas such as wetland, waterways and protected coastal zones and estuaries, which are often risky areas. Adherence and enforcement of environmental laws will ensure that some of the populations now located in risk and disaster areas are relocated to safe zones where proper urban planning has been taken into consideration to reduce flood risk.

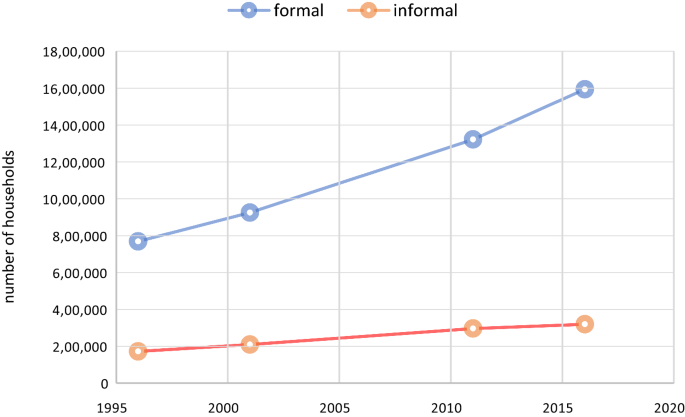

Colenbrander ( 2019 ) argues that despite the transition to democracy and adopting a white paper on sustainable development fairness and inclusivity, the paper is still elusive regarding reducing risk and vulnerability in coastal management in South Africa. SDG Targets 16.6 and Target 16.7 further speak about ensuring the need to develop effective and transparent, and accountable institutions at all levels. They also speak about the need to foster responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision making at all levels. The Western Cape government has often come under fire for directing a considerable share of its resources towards the wealthy elite at the expense of the marginalised (Black et al., 2020 ). This has entrenched and extended inequality in many respects, which has negated the poor to live in squaller conditions. In a bid to reduce risk, the provincial government might need to relook at resource allocation to provide the much needed essential services and deliver on promises of housing for all as a strategy of reducing the housing backlog. This should also provide affordable housing, which will take large segments of the population out of informal settlements. Given the scope and demand for safe housing, there might be a need for the national government, civil society, and private players to roll out housing for the poor and low, middle-income earners who are often at the receiving end of the flooding disasters that affect the province. While there is evidence (Fig. 7 ) that there has been an increase in people living in formal housing, there is a need to arrest the increasing number of people living in informal settlements, most of whom are at the mercy of extreme weather events such as flooding in the Western Cape. A reduction in housing backlog is one good starting point. The Western Cape’s housing backlog is estimated at a staggering 600,000 as of the year 2020, according to a report by Gontsana ( 2020 ).

Source : Authors, Data from Stats SA

Western Cape Household by dwelling type 1995–2016.

One of the challenges that are likely to be faced in housing is the issue of land to relocate people located in climate disaster zones. Releasing state land for human settlement to construct affordable housing and rural development houses is a must in addressing the problem. This has to be done in a holistic manner that does not seek to score cheap political points, as we have seen during the Day Zero drought phenomenon (Nhamo & Agyepong, 2019 ). One other problem from flooding has been the clogging of water systems with either overgrown vegetation or waste, or both. Work by Echendu ( 2020 ) in Nigeria, Abass et al. ( 2020 ) in Ghana, Mahmood et al. ( 2017 ) in Khartoum, and Dalu et al. ( 2018 ) in the Eastern Cape, South Africa, show that poor drainage and drainage clogging, compounds flooding in urban areas. The Western Cape is not unique, as in high density suburbs, the infrastructure maintenance and refuse collection is rather lax. The phenomenon has worsened the impacts of flooding in the city with calls for dredging of weeds overgrowth in waterways; improved refuse collection and waste management calls being made to ensure that there is a substantial reduction of risk of flooding.

Conclusions

The study sought to investigate the trends and impacts of floods in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. Making use of the Mann–Kendall Trend test, the study established that there is a statistically significant increase in the number of flood events that are taking place in the Western Cape province. The study also found that some of the most vulnerable areas to flooding includes Knysna, George, Hermanus and cape flats in Cape Town, to mention but a few. Floods compounded with other urban challenges have led to an increase in the human and economic costs of floods, with some floods costing millions and, in some cases, billions of rand. The loss of property, infrastructure and human lives makes floods an urgent concern that requires urgent attention from development practitioners, city planners, government and ordinary residents to ensure sustainability. Given that flood risk is a result of multiple factors that interact to produce disaster situations for mainly urban areas, there is a need for concerted efforts to put in place measures that build community resilience to floods and build back better thereby producing climate smart societies. The study recommends an integrated approach to the management of flooding in the Western Cape province as part of ensuring urban sustainability. Addressing the flooding challenges further requires a holistic approach that takes into account climate change and other urban challenges such as land grabs, urban sprawling and associated challenges. Lastly, both the private and public sector players need to work together to build climate start infrastructure and insure critical infrastructure against flood hazards given their significant increase over time.

Abass, K., Buor, D., Afriyie, K., Dumedah, G., Segbefi, A. Y., Guodaar, L., Garsonu, E. K., Adu-Gyamfi, S., Forkuor, D., Ofosu, A., & Gyasi, R. M. (2020). Urban sprawl and green space depletion: Implications for flood incidence in Kumasi, Ghana. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 51 (2), 433.

Google Scholar

Adelekan, I. O. (2010). Vulnerability of poor urban coastal communities to flooding in Lagos Nigeria. Environment and Urbanization, 22 (2), 433–450.

Article Google Scholar

Amoako, C., & Frimpong Boamah, E. (2015). The three-dimensional causes of flooding in Accra, Ghana. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 7 (1), 109–129.

Balica, S. F., Wright, N. G., & Van der Meulen, F. (2012). A flood vulnerability index for coastal cities and its use in assessing climate change impacts. Natural Hazards, 64 (1), 73–105.

Black, G. F., Liedeman, R., & Ryklief, F. (2020). Using hand maps to understand how intersecting inequalities affect possibilities for community safety in Cape Town. Community Development Journal, 55 (1), 26–44.

Braccio, S. (2014). Flood-prone areas due to heavy rains and sea level rise in the municipality of Maputo. Climate change vulnerability in Southern African cities (pp. 171–185). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-00672-7_11 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Cian, F., Blasco, J., & Carrera, L. (2018). Towards resilient flood risk management for Asian coastal cities: Lessons learned from Hong Kong and Singapore. Journal of Cleaner Production, 187 (3), 576–589.

Cian, F., Blasco, J. M. D., & Carrera, L. (2019). Sentinel-1 for monitoring land subsidence of coastal cities in Africa using PSInSAR: A methodology based on the integration of SNAP and staMPS. Geosciences, 9 (3), 124.

Colenbrander, D. (2019). Dissonant discourses: Revealing South Africa’s policy-to-praxis challenges in the governance of coastal risk and vulnerability. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 62 (10), 1782–1801.

Dalu, M. T., Shackleton, C. M., & Dalu, T. (2018). Influence of land cover, proximity to streams and household topographical location on flooding impact in informal settlements in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 28 , 481–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.12.009 .

Dhiman, R., VishnuRadhan, R., Eldho, T. I., & Inamdar, A. (2019). Flood risk and adaptation in Indian coastal cities: Recent scenarios. Applied Water Science, 9 (1), 5.

Dodman, D., Leck, H., Rusca, M., & Colenbrander, S. (2017). African urbanisation and urbanism: Implications for risk accumulation and reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 26 , 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.06.029 .

Douglas, I. (2017). Flooding in African cities, scales of causes, teleconnections, risks, vulnerability and impacts. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 26 (1), 34–42.

Douglas, I., Alam, K., Maghenda, M., Mcdonnell, Y., McLean, L., & Campbell, J. (2008). Unjust waters: climate change, flooding and the urban poor in Africa. Environment and urbanization, 20 (1), 187–205.

Dube, K., & Nhamo, G. (2020a). Evidence and impact of climate change on South African national parks. Potential implications for tourism in the Kruger National park. Environmental Development, 33 , 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2019.100485 .

Dube, K., & Nhamo, G. (2020b). Vulnerability of nature-based tourism to climate variability and change: Case of Kariba resort town, Zimbabwe. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 29 , 100281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2020.100281 .

Dube, K., Nhamo, G., & Chikodzi, D. (2020). Climate change-induced droughts and tourism: Impacts and responses of Western Cape province, South Africa. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2020.100319

Dube, K., Nhamo, G., & Chikodzi, D. (2021). Rising sea level and its implications on coastal tourism development in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 33 , 100346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2020.100346 .

Dube, K., Nhamo, G., & Mearns, K. (2020). &Beyond’s Response to the twin challenges of pollution and climate change in the context of SDGs. In G. Nhamo, G. Odularu, & V. Mjimba (Eds.), Scaling up SDGs implementation. Sustainable development goals series (pp. 87–98). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33216-7_6 .

Duy, P. N., Chapman, L., & Tight, M. (2019). Resilient transport systems to reduce urban vulnerability to floods in emerging-coastal cities: A case study of Ho Chi Minh city Vietnam. Travel Behaviour and Society, 15 , 28–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2018.11.001 .

Echendu, A. J. (2020). The impact of flooding on Nigeria’s sustainable development goals (SDGs). Ecosystem Health and Sustainability, 6 (1), 1791735.

Enqvist, J. P., & Ziervogel, G. (2019). Water governance and justice in Cape Town: An overview. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water, 6 (4), e1354.

Fitchett, J. M., Grant, B., & Hoogendoorn, G. (2016). Climate change threats to two low-lying South African coastal towns: Risks and perceptions. South African Journal of Science, 112 (5–6), 1–9.

Gontsana, M., 2020. Daily Maverick . [Online] Available at: Retrieved from 4 January 2021 https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-03-26-housing-backlog-exceeds-half-a-million-in-western-cape/ .

Gwaze, A., Hsu, T. T., Bosch, T., & Luckett, S. (2018). The social media ecology of spatial inequality in Cape Town: Twitter and instagram. Global Media Journal-African Edition, 11 (1), 1–20.

Hallegatte, S., Green, C., Nicholls, R. J., & Corfee-Morlot, J. (2013). Future flood losses in major coastal cities. Nature Climate Change, 3 (9), 802–806.

Hamed, K. H. (2008). Trend detection in hydrologic data: The Mann–Kendall trend test under the scaling hypothesis. Journal of Hydrology, 349 (3–4), 350–363.

Handayani, W., Fisher, M. R., Rudiarto, I., Setyono, J. S., & Foley, D. (2019). Operationalizing resilience: A content analysis of flood disaster planning in two coastal cities in Central Java, Indonesia. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 35 , 101073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101073 .

Hirabayashi, Y., Mahendran, R., Koirala, S., Konoshima, L., Yamazaki, D., Watanabe, S., Kim, H., & Kanaen, S. (2013). Global flood risk under climate change. Nature Climate Change, 3 (9), 816–821.

Hu, Z., Liu, S., Zhong, G., Lin, H., & Zhou, Z. (2020). Modified Mann-Kendall trend test for hydrological time series under the scaling hypothesis and its application. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 45 (14), 2419.

IPCC, 2019. Special report on the ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate, s.l.: IPCC.

Jiang, Y., Zevenbergen, C., & Ma, Y. (2018). Urban pluvial flooding and stormwater management: A contemporary review of China’s challenges and “sponge cities” strategy. Environmental Science & Policy, 80 , 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.11.016 .

Jordhus-Lier, D., Saaghus, A., Scott, D., & Ziervogel, G. (2019). Adaptation to flooding, pathway to housing or ‘wasteful expenditure’? Governance configurations and local policy subversion in a flood-prone informal settlement in Cape Town. Geoforum, 98 , 55–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.029 .

Kabanda, T. (2020). GIS modeling of flooding exposure in Dar es Salaam coastal areas. African Geographical Review, 39 (2), 134–143.

Kim, Y., Eisenberg, D. A., Bondank, E. N., Chester, M. V., Giuseppe Mascaro, B., & Underwood, S. (2017). Fail-safe and safe-to-fail adaptation: decision-making for urban flooding under climate change. Climatic Change, 145 (3–4), 397–412.

Kithiia, J. (2011). Climate change risk responses in East African cities: Need, barriers and opportunities. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 3 (3), 176–180.

Leal Filho, W., Balogun, A. L., Ayal, D. Y., Bethurem, E. M., Murambadoro, M., Mambo, J., & Mugabe, P. (2018). Strengthening climate change adaptation capacity in Africa-case studies from six major African cities and policy implications. Environmental Science & Policy, 86 , 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.05.004 .

Leal Filho, W., Balogun, A. L., Olayide, O. E., Azeiteiro, U. M., Ayal, D. Y., Muñoz, P. D., & Saroar, M. (2019). Assessing the impacts of climate change in cities and their adaptive capacity: Towards transformative approaches to climate change ada. Science of The Total Environment, 692 , 1175–1190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.227 .

Liu, J., Xu, Z., Chen, F., Chen, F., & Zhang, L. (2019). Flood hazard mapping and assessment on the Angkor world heritage site Cambodia. Remote Sensing, 11 (1), 98.

Mahmood, M. I., Elagib, N. A., Horn, F., & Saad, S. A. (2017). Lessons learned from Khartoum flash flood impacts: An integrated assessment. Science of the Total Environment, 601 , 1031–1045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.05.260 .

Mirza, M. M. Q. (2003). Climate change and extreme weather events: Can developing countries adapt? Climate Policy, 3 (3), 233–248.

Mukheibir, P., & Ziervogel, G. (2007). Developing a municipal adaptation plan (MAP) for climate change: The city of Cape Town. Environment and Urbanization, 19 (1), 143–158.

Nhamo, G., & Agyepong, A. O. (2019). Climate change adaptation and local government: Institutional complexities surrounding Cape Town’s day zero. Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 11 (3), 1–9.

Nhamo, G., Dube, K., & Chikodzi, D. (2020). Counting the Cost of COVID-19 on the global tourism industry (1st ed.). Switzerlerland: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56231-1 .

Book Google Scholar

Ogie, R. I., Holderness, T., Dunn, S., & Turpin, E. (2018). Assessing the vulnerability of hydrological infrastructure to flood damage in coastal cities of developing nations. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, 68 , 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2017.11.004 .

Park, S. J., & Lee, D. K. (2020). Prediction of coastal flooding risk under climate change impacts in South Korea using machine learning algorithms. Environmental Research Letters, 15 (9), 094052.

Patel, Z., Greyling, S., Simon, D., Arfvidsson, H., Moodley, N., Primo, N., & Wright, C. (2017). Local responses to global sustainability agendas: learning from experimenting with the urban sustainable development goal in Cape Town. Sustainability science, 12 (5), 785–797.

Phiri, D., Simwanda, M., & Nyirenda, V. (2020). Mapping the impacts of cyclone Idai in Mozambique using Sentinel-2 and OBIA approach. South African Geographical Journal, 103 (2), 237–258.

Rasmusson, E. M., & Wallace, J. M. (1983). Meteorological aspects of the El Nino/southern oscillation. Science, 4629 (222), 1195–1202.

Reimann, L., Vafeidis, A. T., Brown, S., Hinkel, J., & Tol, R. S. J. (2018). Mediterranean UNESCO world heritage at risk from coastal flooding and erosion due to sea-level rise. Nature communications, 9 (1), 1–11.

Ribot, J. (2014). Cause and response: Vulnerability and climate in the Anthropocene. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 41 (5), 667–705.

Rouault, M., White, S. A., Reason, C. J. C., Lutjeharms, J. R. E., & Jobard, I. (2002). Ocean–atmosphere interaction in the Agulhas current region and a South African extreme weather event. Weather and Forecasting, 17 (4), 655–669.

South African Weather Service , 2019. Annual state of climate 2019, s.l.: South African Weather Service.

Stramma, L., & Lutjeharms, J. (1997). The flow field of the subtropical gyre of the South Indian Ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research, 102 (C3), 5513–5530.

Taylor, A. (2019). Managing stormwater and flood risk in a changing climate: Charting urban adaptation pathways in Cape Town. In D. Scott, H. Davies, & M. New (Eds.), Mainstreaming climate change in urban development: Lessons from Cape Town (pp. 224–241). Cape Town: Cape Town University Press.

Taylor, A. & Davies, H., 2019. An overview of climate change and urban development in cape town. Climate change and urban development: lessons from Cape Town. Cape Town: UCT Press.

United Nations, 2015. Agenda 2030 on sustainable development . [Online] Available at: Retrieved from 11 July 2020 https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf .

United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2015. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, s.l.: United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction.

White, S. A., 2000. The influence of the Agulhas Current on two South African extreme weather events , Cape Town: (Doctoral dissertation, University of Cape Town)..

Zoleta-Nantes, D. B. (2002). Differential impacts of flood hazards among the street children, the urban poor and residents of wealthy neighborhoods in Metro Manila, Philippines. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 7 (3), 239–266.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Ecotourism Management, Vaal University of Technology, Private Bag X021, Vanderbijlpark, 1911, South Africa

Kaitano Dube

Institute of Corporate Citizenship, University of South Africa, PO Box 392 Pretoria 002, Pretoria, South Africa

Godwell Nhamo & David Chikodzi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kaitano Dube .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

There is no conflict of interest in conducting and writing the article.

Compliance with ethical standards

This serves to declare that myself Kaitano Dube on my behalf and on behalf of the co-authors Godwell Nhamo and David Chikodzi all from University of South Africa are the sole authors of the article Trends and impacts of floods in coastal communities of the Western Cape province in South Africa which we have submitted for publication consideration in GeoJournal. All the authors participated enough to be considered authors of the article. We further attest that all third-party material has been acknowledged. The research was conducted in line with ethical provisions as provided by researcher institutions.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Dube, K., Nhamo, G. & Chikodzi, D. Flooding trends and their impacts on coastal communities of Western Cape Province, South Africa. GeoJournal 87 (Suppl 4), 453–468 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-021-10460-z

Download citation

Accepted : 15 June 2021

Published : 25 June 2021

Issue Date : October 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-021-10460-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Coastal flooding

- Natural hazards

- Western Cape

- Climate change

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Publications

- Press Releases

- Meet the Team

- Our Ambassadors

- Share our work

- Human Settlements

- Nature & Land Use

- Youth & Civil Society

We’re in a Race.

A race against time and against ourselves. Against the dangerous idea that we can’t do this, that there is no way.

Unlike most races, it won’t have one winner. In this race we all win, or we all lose. Winning it requires a radical, unprecedented level of collaboration, from all corners of our world. From our cities, businesses, regions and investors. From people everywhere.

Together we’re racing for a better world. A zero carbon and resilient world. A healthier, safer, fairer world. A world of wellbeing, abundance and joy, where the air is fresher, our jobs are well-paid and dignified, and our future is clear.

To get there we need to run fast, and get faster. We need more and more people to join the race, and right now. This is not about 2050, it’s about today.

How South Africa’s recent floods compel climate action

- South Africa is recovering from the biggest natural disaster to hit the country in recent history.

- The country is proactively responding to climate change through adaptation-focused regulation and green energy investments.

- A just transition that protects both lives and livelihoods is the best strategy for South Africa.

In April 2022, heavy rains, flooding, and subsequent mudslides hit the KwaZulu-Natal coast in South Africa. While efforts are underway to establish the extent of the damage, hundreds of lives have been lost, with many more still missing. When visiting the disaster-struck areas around the city of Durban, South Africa’s president, Cyril Ramaphosa, shared his perspective on what lay behind the country’s worst natural disaster on record: “We no longer can postpone what we need to do – we must deal with climate change.”

The impact of the disaster was not equally felt . South Africa is the world’s most unequal country , and it was in the poorer regions where the consequences of the extreme weather were most severe. This impact visualises the plea of many African nations: Poor communities contribute the least to global pollution but are suffering the most.

Adaptation through climate law

Disasters such as these can mark a national conscience and drive forward the urgency to act. South Africans are, given the country’s unique history, people of civil action. In the wake of the disaster, thousands of volunteers are assisting in relief efforts, while climate justice movements are calling on the government to take practical action to address the climate crisis. These public calls aren’t falling on deaf ears, with the nation’s parliament currently deliberating a Climate Change Bill . If enacted, this law will place a legal obligation on all local and provincial governments to undertake climate change needs assessments, followed by climate change response implementation plans. These climate change response plans must, as a next step, be integrated into all existing social development plans.

The bill provides for adaptation objectives for the country. These objectives are specific green targets that the government must reach within stringent timeframes. The bill also provides for carbon taxes on heavy polluters and sectoral carbon budgets. Environment minister, Barbara Creecy , has called the bill “a dream come true” and that it brings all the country’s efforts to deal with climate change under one piece of legislation. Creecy has emphasized that “Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the regions of the world that is most vulnerable to climate change. This vulnerability poses an existential threat to human populations and biodiversity.”

A just transition

One of the results of COP26 was the launch of the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP). This partnership between South Africa, France, Germany, the UK, and the USA, aims to support South Africa’s just transition to a low carbon economy and climate-resilient society. As Africa’s most industrialized nation and the world’s 7 th largest coal producer , South Africa is the world’s 12 th largest emitter of carbon dioxide (C02) and is responsible for nearly half of Africa’s C02.

The energy industry is liable for the largest share of emissions, with the country’s energy utility, Eskom, berated as the world’s most polluting power company . While 80% of the country’s energy is still generated from coal , the ongoing war in Ukraine is increasing global demand for South African coal .

With coal mining employing thousands, particularly in the north-eastern province of Mpumalanga, the impact of this industry on the environment and livelihoods is severe. Greenpeace has identified the city of Witbank, in Mpumalanga’s coal belt, as the world’s largest Nitrogen Dioxide hotspot, and a recent court ruling found that air pollution in the area infringes residents’ constitutional right to an environment that isn’t harmful to their health. This just transition away from coal is a necessity not just for those suffering the consequences of extreme weather but for lives indebted to the economic clout of coal in regions like Mpumalanga.

A key mandate of the partnership involves the need for an equitable and inclusive transition for workers and vulnerable communities away from current economic dependencies. While coal mining has been a bedrock of the economy, South Africa is blessed with immense renewable energy potential for the just transition, boasting an average of 2,500 hours of sunshine per year and 4,5 to 6,6 kWh/m 2 of radiation levels for solar power; and wind power potential of up to 6,7000 GWs.

The partnership aims to mobilize $8,5 billion over 3-5 years to bring South Africa’s carbon emissions within the Paris Agreement targets by shifting away from fossil fuels to renewable sources. Renewable energy has already created over 55,000 jobs in the country , and, in Mpumalanga alone, up to 72,000 energy transition jobs can be created through 2030. The adverse, unfortunately, is that roughly 74,000 jobs are at risk. Sustainable job alternatives for such workers are crucial.

Protecting lives and livelihoods

President Ramaphosa’s maxim amidst COVID-19 has been to ‘Protect lives and livelihoods’, speaking of the importance of protecting people both physically and economically. As the nation faces up to the challenge of climate change, this approach will remain relevant. Regulatory action like the Climate Change Bill and proactive green investment drives like the JETP will be crucial as the country gears up for what’s to come. The country’s power landscape is already transforming, with the World Economic Forum ’s Regional Action Group for Africa predicting a power transition to net-zero will be driven by three-D’s: Decarbonization, Decentralization, and Digitalization. Decarbonization sees a move away from fossil fuels, led by major investments such as the Absa-AREP renewable investment platform . Decentralization marks the progress from centralized energy utilities to the incorporation of more independent power producers on the grid, while digitization involves leveraging digital technology to advance the transition.

Former president Thabo Mbeki famously said “I am an African. I owe my being to the hills and the valleys, the mountains and the glades, the rivers, the deserts, the trees, the flowers, the seas, and the ever-changing seasons that define the face of our native land.”

The floods in KwaZulu-Natal may embed a greater sense of urgency among all about transitioning away from fossil fuels and adapting to future threats. Protecting this uniquely beautiful country and the diverse people that call her home may perhaps be the biggest unifying challenge that awaits all South Africans.

- Just Transition

Progressing global adaptation and resilience action: Contribute to the Sharm El-Shiekh Adaptation Agenda annual implementation report

The Climate Champions invite you to participate in the Sharm Adaptation Agenda Public Survey. Your insights will be instrumental in assessing the progress we’ve made across key areas.

How oysters are helping protect Apalachicola’s vulnerable shoreline

This nature-based solution involves creating up to 20 acres of engineered oyster reefs and up to 30 acres of salt marshes to help protect the vulnerable coastline of Florida’s Apalachicola Bay.

Turning money into mortar: Transforming the housing landscape in disaster-prone Philippines

Discover how Race to Resilience partner, Build Change, empowers people in the Philippines with resilient housing, leveraging microfinance solutions to address disaster risks and improve lives.

- Losses & Damages

The Sharm el Sheikh Adaptation Agenda: Catalysing collaborative action towards a resilient future

Resilience experts and members of Race to Resilience’s MAG advisory group, Anand Patwardhan, Emilie Beauchamp, Ana Maria Lobo-Guerrero, and Paulina Aldunce, underline the transformative impact of the Sharm El Sheikh Adaptation Agenda in driving collaboration and fast-tracking action to bridge the adaptation gap and support the world’s most vulnerable communities.

- Climate Justice

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Death Toll in South Africa Floods Passes 306

The devastation fueled criticism that the government should have been better prepared for the weather after intense rain in 2017 and 2019.

By John Eligon

JOHANNESBURG — The death toll from several days of punishing rain that drenched the city of Durban and the surrounding areas near South Africa’s east coast rose to more than 306 on Wednesday, prompting criticism from residents that the government had failed to prepare for what are now increasingly frequent storms.

Although the rain in the region stopped on Tuesday, officials were still trying to fully assess the massive human and infrastructure toll as rescue crews rummaged through muddy hillsides in search of the missing. The dayslong rain was reminiscent of weather around this same time in 2017 and in 2019 but brought more destruction, washing away bridges, leaving gaping holes in roadways, and sweeping homes and shacks from their foundations.

Residents and community leaders recalled promises made by local officials to improve drainage systems, strengthen roadways, and move shack settlers into more stable housing and away from flood-prone areas. But those pledges were not fulfilled, they said.

“When infrastructure fails it leads to human catastrophe,” said Sbu Zikode, the president of Abahlali baseMjondolo, a shack dwellers movement concentrated in KwaZulu-Natal, the province where the rain and flooding occurred.

The recent flooding, he added, exposed the government’s “lack of political will not only to invest in the infrastructure development, but also to maintain the infrastructure that we have.”

The steady rain, which came down in droves at times, started late last week and continued almost nonstop through the weekend. Parts of a national highway were flooded and looked like a river.

President Cyril Ramaphosa traveled on Wednesday to KwaZulu-Natal, meeting with provincial leaders and touring affected regions. The devastation has caused 306 deaths, according to the government.

“You have experienced the biggest tragedy that we have ever seen,” Mr. Ramaphosa told residents of one community, according to television news video of his visit.

But the president’s visit only aggravated the emotions of some residents who felt that the government had failed them.

A local official on Tuesday pushed back against the suggestion that the government’s failure led to the devastation.

The storms this year were different from the devastating ones in 2017 and 2019 because those were concentrated in certain areas, according to Mxolisi Kaunda, the mayor of eThekwini, the municipality that includes Durban and the surrounding area. The rain this past week was more widespread and much of the damage and fatalities resulted from landslides, he said at a news conference.

“So therefore, it has got nothing to do with the drainage system,” he said.

That suggestion did little to satisfy residents like Cosmos Khanyeza, who lives just outside Mega City, a shack settlement south of Durban. The severe weather in 2019 wiped out about 70 homes in the settlement, he said. After that, he and other community members wrote to the municipality, requesting help in building permanent housing for those who were displaced. They received no response, he said.

As a result, many of the same families who were affected in 2019 were still living in shacks that were destroyed or severely damaged this time around. He said at least 15 homes in Mega City were swept away by the recent storms.

Mr. Khanyeza, who is 53 and works in construction, doubted that this would be a wake-up call for the government.

“Nothing,” he said. “Nothing will happen.”

Lynsey Chutel contributed reporting.

John Eligon is the Johannesburg bureau chief, covering southern Africa. He previously worked as a reporter on the National, Sports and Metro desks. His work has taken him from the streets of Minneapolis following George Floyd’s death to South Africa for Nelson Mandela’s funeral. More about John Eligon

South Africa declares national state of disaster over floods