An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Healthc Policy

- v.7(Spec Issue); 2011 Dec

Language: English | French

An Overview of Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Item Response Analysis Applied to Instruments to Evaluate Primary Healthcare

Aperçu de l'analyse factorielle confirmatoire et de l'analyse de réponse par item appliquées aux instruments d'évaluation des soins primaires, darcy a. santor.

School of Psychology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON

Jeannie L. Haggerty

Department of Family Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, QC

Jean-Frédéric Lévesque

Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC

Frederick Burge

Department of Family Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS

Marie-Dominique Beaulieu

Chaire Dr Sadok Besrour en médecine familiale, Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC

Raynald Pineault

This paper presents an overview of the analytic approaches that we used to assess the performance and structure of measures that evaluate primary healthcare; six instruments were administered concurrently to the same set of patients. The purpose is (a) to provide clinicians, researchers and policy makers with an overview of the psychometric methods used in this series of papers to assess instrument performance and (b) to articulate briefly the rationale, the criteria used and the ways in which results can be interpreted. For illustration, we use the case of instrument subscales evaluating accessibility. We discuss (1) distribution of items, including treatment of missing values, (2) exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis to identify how items from different subscales relate to a single underlying construct or sub-dimension and (3) item response theory analysis to examine whether items can discriminate differences between individuals with high and low scores, and whether the response options work well. Any conclusion about the relative performance of instruments or items will depend on the type of analytic technique used. Our study design and analytic methods allow us to compare instrument subscales, discern common constructs and identify potentially problematic items.

Cet article présente un aperçu des approches analytiques que nous avons utilisées pour évaluer le rendement et la structure des mesures qui servent à évaluer les soins de santé primaires : six instruments ont été appliqués simultanément au même groupe de patients. L'objectif est (a) de fournir aux cliniciens, aux chercheurs et aux responsables de politiques, un aperçu des méthodes psychométriques utilisées dans cette série pour évaluer le rendement de l'instrument et (b) d'articuler brièvement l'analyse raisonnée, les critères employés et les façons dont peuvent être interprétés les résultats. À titre d'exemple, nous avons utilisé le cas des sous-échelles qui servent à évaluer l'accessibilité. Nous discutons (1) la distribution des items, y compris le traitement des valeurs manquantes, (2) les analyses factorielles exploratoires et confirmatoires afin de voir comment les items de différentes sous-échelles sont liés à un seul construit (ou sous-dimension) sous-jacent et (3) l'analyse de réponse par item pour voir si les items permettent de discriminer les différences entre les unités qui présentent des scores élevés et faibles, et pour voir si les choix de réponses fonctionnent bien. Toute conclusion sur le rendement relatif des instruments ou des items dépend du type de technique analytique employé. La conception et les méthodes analytiques de cette étude permettent de comparer les sous-échelles des instruments, de discerner les construit communs et de repérer les items potentiellement problématiques.

Psychometric scales and instruments have been used to assess virtually every component of healthcare, whether to identify gaps in service, to assess special needs of patients, or to evaluate the performance and efficiencies of programs, organizations or entire healthcare systems. In this special issue of Healthcare Policy , we examine the performance of several instruments that assess different attributes of primary healthcare from the patient's perspective. Any conclusion about the relative performance of instruments and items from those instruments will depend on the type of analytic technique used to assess performance.

The purpose of this paper is to describe the analytic approach and psychometric methods that we used to assess and compare the performance of the instrument subscales. We articulate the rationale of different approaches, the criteria we used and how results can be interpreted. For illustration, we use the case of instrument subscales evaluating accessibility, described in detail elsewhere in this special issue ( Haggerty, Lévesque et al. 2011 ).

Data Sources

All the instruments used in this study have previously been validated and meet standard criteria for validity and reliability. The goal of the study was to extend this process of validation and compare the performance of the six instruments for measuring core attributes of primary healthcare for the Canadian context. Our intention is not to recommend one instrument over another, but to provide insight into how different subscales measure various primary healthcare attributes, such as accessibility and care.

We administered the six instruments to 645 health service users in Nova Scotia and Quebec: the Primary Care Assessment Survey (PCAS, Safran et al. 1998 ); the adult version of the Primary Care Assessment Tool – Short (PCAT-S, Shi et al. 2001 ); the Components of Primary Care Index (CPCI, Flocke 1997 ); the first version of the EUROPEP ( EUROPEP-I, Grol et al. 2000 ); the Interpersonal Processes of Care – 18-item version (IPC-II, Stewart et al. 2007 ); and the Veterans Affairs National Outpatient Customer Satisfaction Survey (VANOCSS, Borowsky et al. 2002 ). The sample was balanced by overall rating of primary healthcare, high and low level of education, rural and urban location, and English and French language ( Haggerty, Burge et al. 2011 ).

Distribution of Responses

The first step was to examine the distribution of the responses, flagging as problematic items where a high proportion of respondents select the most negative (floor effect) or the most positive (ceiling effect) response options, or have missing values. Missing values, where respondents failed to respond or wrote in other answers, may indicate questions that are not clear or are difficult to understand. We expected low rates of true missing values because truly problematic items would be eliminated during initial validation by the instrument developers, but remained sensitive to items that are problematic in the Canadian context.

However, some instruments offer response options such as “not applicable” (EUROPEP-I) or “not sure” (PCAT-S), which count as missing values in analysis because they cannot be interpreted as part of the ordinal response scale. They represent a loss of information as they cannot be interpreted.

Missing information, for whatever reason, is problematic for our study given that missing information on any item means that data for the entire participant is excluded from factor analysis (listwise missing), compromising statistical power and potentially introducing bias. In the case of accessibility subscales, 340 of the 645 respondents (53%) were excluded from factor analysis because of missing values, of which 267 (79%) were for selecting “not sure” or “not applicable” options. We examined the potential for bias by testing for differences between included and excluded respondents on all relevant demographic and healthcare use variables. We also imputed values for most of the missing values using maximum likelihood imputation ( Jöreskog and Sörbom 1996 ), which uses the subject's responses to other items and characteristics to impute a likely value. Then, we repeated all the factor analyses to ensure that our conclusions and interpretations remained unchanged, and reducing the possibility of bias. Nonetheless, the high proportion of missing values in some instances is an important limitation of our study, and needs to be considered in the selection of instruments.

Subscale Scores

Next, we examined the performance by subscale. Subscale scores were mostly calculated as the mean of item values if over 50% of the items were complete. This score was not affected by the number of items, and it reflects the response options. For example, a subscale score of 3.9 in Organizational Access on the PCAS corresponds approximately to the “4=good” option on the response scale of 1 (very poor) to 6 (excellent). But it is difficult to know how this compares to the score of 3.6 on the EUROPEP-I Organization of Care for a similar dimension of accessibility from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent). To compare the subscales between different response scales, we normalized scores to a common 0-to-10 metric using the following formula:

New score = {(raw score − minimum possible) / (raw maximum − raw minimum)} * 10

So, the normalized mean for PCAS Organizational Access, 5.9, is seen to be considerably lower than 6.5 on the EUROPEP-I Organization of Care, and the PCAS variance is lower than the EUROPEP-I (1.8 vs. 2.4). Thus, if accessibility were measured in one population using the PCAS and in another using the EUROPEP-I, the scores of the EUROPEP-I would be expected to be higher than the PCAS, even if there were no difference in accessibility between the two populations.

Reliabilities

The reliability of each subscale was evaluated using Cronbach's coefficient a, which estimates how much each item functions as a parallel, though correlated, test of the underlying construct. Cronbach's a ranges from 0 (items completely uncorrelated, all variance is random) to 1 (each item yields identical information), with the convention of .70 indicating a minimally reliable subscale. The subscales included in our study all reported adequate to good internal consistency. The coefficient a is sensitive to sample variation as well as the number and quality of items. Given that our study sample was selected to overrepresent the extremes of poor and excellent experience with primary healthcare relative to a randomly selected sample, we expected our alpha estimates to meet or exceed the reported values.

We then calculated Pearson correlations among the subscale scores, controlling for educational level, geography and language (partial correlation coefficients) to account for slight deviations from our original balanced sampling design. We expect high correlations between subscales mapped to the same attribute (convergent validity) and lower correlations with subscales from other attributes (some degree of divergent validity), indicating that the items in the subscales are indeed specific to that attribute and that respondents appropriately distinguish between attributes. Pearson correlation coefficients indicate expected relationships observed in factor analysis. If we observe high correlations within an attribute, then we would expect all the items from those subscales to “load” on a common factor. So, for example, after the correlation analysis for accessibility, we observed that the PCAT-S First-Contact Utilization subscale correlated less strongly with the other accessibility subscales than it did with relational continuity. We had high expectations that its items would not only form a separate factor, but also that it would relate poorly to accessibility as a whole.

Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Subscales from different instruments that were designed to assess the same primary healthcare attribute should relate to a single underlying factor or construct. We used both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis to examine this premise, as well as to determine whether items across subscales related to sub-dimensions within the attribute.

Exploratory analyses

Exploratory factor analysis is a descriptive technique that can detect an overarching structure that explains the relationships between items in a parsimonious way. We used the common factor analysis procedure computed in SAS v. 9.1 ( SAS 2003 ). This procedure identifies how much items can be represented by a smaller group of variables (i.e., common factors) that account for as much of the variability in the data as possible. The procedure assigns an eigenvalue to each factor that corresponds to the total variance in item responses that can be explained by the factor. Typically, factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0 are retained.

This procedure also computes how strongly each individual item maps on to each factor. “Factor loadings” range from –1.0 to 1.0 and can be interpreted much like a correlation coefficient. These indicate (a) the extent to which all items relate to one or more distinctive factors, (b) how strongly each item is related to each factor (and whether the item should be retained or eliminated within a factor) and (c) how much variation in responses to items can be accounted for by each factor or subgroup. We considered items with factor loadings ≥| .4 | as strongly related to the underlying factor. It is important to note that common factor analysis assumes a normal distribution; items with highly skewed distributions will affect both the loadings and the extent to which factors can be easily interpreted ( Gorsuch 1983 ).

Results of an exploratory factor analysis for items in subscales from three different instruments assessing accessibility are presented in Table Table1. 1 . Factor loadings are presented for each item showing how each item is related to three distinct factors. The first factor has a large eigenvalue (7.84) and accounts for approximately 41% of variance in the responses given to items, compared to just 6% for the second factor (eigenvalue=1.19) and less than 1% for the third. As a result, only two factors would be considered worth interpreting. This confirms our expectation based on the correlation analysis that the PCAT-S First-Contact Utilization subscale might not fit with other accessibility subscales. The two important underlying factors could be characterized as timeliness and accommodation ( Haggerty, Lévesque et al. 2011 ).

Factor loadings from an oblique exploratory principal component analysis for accessibility items drawn from four measures of accessibility

Note: Factor loadings smaller than 0.40 have not been presented.

Confirmatory analyses

Confirmatory factor analysis differs from exploratory factor analysis by allowing the investigator to impose a structure or model on the data and test how well that model “fits.” The “model” is a hypothesis about (a) the number of factors, (b) whether the factors are correlated or uncorrelated and (c) how items are associated with the factor. Models with different configurations are compared using structural equation modelling. Statistical software packages produce various “goodness-of-fit” statistics that capture how well the implied variance–covariance matrix of the proposed model corresponds to the observed variance–covariance matrix (i.e., how items from the instrument actually correlate). Confirmatory factor analysis attempts to account for the covariation among items (ignoring error variance), whereas common factor analysis accounts for the “common variance” shared among items, differentiating variance attributable to an underlying factor and error variance. Although similar in spirit, factor loadings are computed in fundamentally different ways from common factor analysis and should be interpreted differently.

Our premise was that different measures of an attribute can still be viewed as indicators (i.e., items) assessing the same underlying construct despite being drawn from different instruments employing different phrasing and response scales. Testing this hypothesis allows researchers and policy makers to view similarly the results obtained from different measures of, say, accessibility.

Figure Figure1 1 presents the results of a confirmatory factor analysis for accessibility subscales. Figure Figure1A 1 A depicts a standard unidimensional model, where every item is linked to the same, single underlying construct, namely accessibility. Constructs (designated with ellipses) are linked to (designated with arrows with loading coefficients) individual items (designated with rectangular boxes). The model shows that most items load strongly (i.e., factor loading greater than .90) on the latent construct called Access, but that some items do not (e.g., loadings of .71 and .78) or they have high residual error, shown to the right of the item.

Results of a confirmatory factor analysis for accessibility subscales

The performance of the model is evaluated by examining the ensemble of “goodness-of-fit” statistics, such as the comparative fit index (CFI), the normed fit index (NFI), consistent Akaike's information criterion (CAIC) or the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA). They all assess in different ways the discrepancy between the pattern of variances and covariances implied by the model and the actual pattern of variances and covariances observed in the data (see Kline 1998 for an in-depth review of basic issues in structural equation modelling). If the implied pattern is close to what is observed in the data, then the model is said to fit – it accurately accounts for the manner in which items are interrelated.

Fit statistics for the model in Figure Figure1A 1 A were all good. Unlike the usual interpretation of significance, lower chi-squared (χ 2 ) values suggest better fit. The χ 2 value was 649 with 152 degrees of freedom and was significant, which might indicate the model does not fit well (though χ 2 is sensitive to large samples such as ours). However, other fit statistics, such as NFI, CAIC and GFI (results not shown), which take into consideration both the sample size and model complexity, were all well above the conventional criterion of .90 of “good fit.” The RMS EA of .104 is higher than the .05 criterion indicating good fit, but is still reasonable. Altogether, these results suggest that although items were drawn from distinct subscales, response to questions can be accounted for by a single underlying construct, namely, accessibility.

However, we might hypothesize that because items were drawn from subscales with different numbers of response options and formats, the pattern of responses would be even better explained by a model that explicitly locates individual items with the subscale from their parent instrument (first-order factor) and then links these first-order factors within the general construct of accessibility (a second-order factor). Figure Figure1B 1 B depicts this second-order, multidimensional model. Fit statistics for this model were also extremely good. Again, NFI, CAIC and GFI were all .98. The χ 2 value was 514 (with 148 degrees of freedom).

Comparing models

One of the strengths of a confirmatory factor analysis is the ability to compare “nested” models, where one model is a simpler version of a more complex model. Because these models differ only in the number of paths that are being estimated, χ 2 values for one model can be subtracted from the other and the significance of the difference evaluated. The χ 2 difference between the simple model in Figure Figure1A 1 A and the more complex model in Figure Figure1B 1 B (649 – 514 = 135, 4 df ) is statistically significant, so we can infer that the complex model is more valid. Some of the variability in how individuals respond to questions is not just determined by the underlying construct of accessibility, but also by the specific measure from which the question is drawn.

We also test a model that groups items within sub-dimensions of accessibility. Figure Figure1C 1 C depicts a second-order, multidimensional model in which items are grouped within two first-order factors, namely, the timeliness of service and the extent to which patients' access barriers are accommodated, which are themselves part of a broader, second-order factor: accessibility. This model says there are two components of the more general construct of accessibility, and that these transcend specific instrument subscales.

It is important to note that not all models can be compared directly. The model in Figure Figure1C 1 C does not include the items from the PCAT First-Contact Utilization subscale; it differs from the model in Figure Figure1A 1 A by more than the number of paths. To test the validity of this model, we compared its own restricted version rather than the model depicted in Figure Figure1A 1 A and found that grouping items within sub-factors of timeliness and accommodation is superior to the one-dimensional model (χ 2 426 – 364 = 52, 3 degrees of freedom).

Item Response Models

Item response analysis evaluates how well questions and individual response options perform at different levels of the underlying construct being evaluated. They provide a fine-grained level of analysis that can be used to evaluate how well individual items and options discriminate among individuals at both high and low levels of the construct and can identify items and options that should ideally be revised or, if necessary, discarded.

Defining a shared or common underlying continuum against which items can be compared is crucial, because any result will be contingent on the appropriateness of this common underlying dimension. Each item's performance was modelled two ways, as a function of (1) items drawn from the single original subscale and (2) all items from any subscale that appear to measure a common construct, for example, timeliness within accessibility. Items are likely to perform better when modelled as a function of just the instrument from which they were drawn. However, because our goal is to compare the relative performance of all items (which may come from different instruments) that are believed to assess a similar construct (i.e., accessibility), we report on items modelled on the shared or common underlying dimension (e.g., timeliness within accessibility).

We used a non-parametric item response model to examine item performance on the common underlying factor ( Ramsay 2000 ). This is an exploratory approach ( Santor and Ramsay 1998 ), and these techniques have been used previously to examine the psychometric properties of self-report items and to evaluate item bias ( Santor et al. 1994 ; Santor et al. 1995 ; Santor and Coyne 2001 ). A detailed description of the algorithm used to estimate response curves has been published elsewhere ( Ramsay 1991 ).

We supplemented our non-parametric models with parametric item response modelling to estimate the discriminatory capacity of each item within its own original subscale using Multilog ( Du Toit 2003 ). Discriminability (the “a” parameter) indicates an item's sensitivity to detect differences among individuals ranked on the construct being measured (e.g., accessibility). It can be viewed as a slope, with a value of 1 considered the lower limit for acceptable discriminability, i.e., each unit increase in the item predicts a unit increase in the underlying construct. Items with lower discriminability in the parent construct invariably performed poorly on the common underlying dimension with non-parametric item response modelling.

Examining item performance

To illustrate how item response models can be used to evaluate item and response option performance, Figures Figures2A, 2 A, A,2B 2 B and and2C 2 C show item response graphs for three items drawn from the PCAT-S and EUROPEP-I subscales assessing construct of timeliness within accessibility. Figure Figure2A 2 A presents a relatively well-performing item from the PCAT-S; Figures Figures2B 2 B and and2C 2 C illustrate some difficulties in the other two items.

Response graphs for three items drawn from the PCAT-S and EUROPEP-I subscales assessing construct of timeliness within accessibility

In the Figure Figure2 2 graphs, the total expected score for timeliness is presented at the top of the plot; below the horizontal axis on the bottom, it is represented as standard normal scores. Expressing scores as standard normal scores is useful because it is informative about the proportion of a population above or below integer values of standard deviations from the mean score. So in the graphs we can see that −2 SD corresponds to a total timeliness score of 18.3, the mean is 30.8, and +2 SD is 27.1. Extreme values on curves need to be interpreted with caution because, by definition, sample sizes are small in the tails of the overall distribution of scores.

The overall performance of the item is captured in the steepness of the slope of the characteristic curve (the topmost dashed lines in Figure Figure2A–C), 2 A–C), which expresses item discriminability, the relationship between the cumulated item score and the total score in the construct (e.g., total timeliness). Given that we calculated items from different instruments as a function of a common continuum, slopes can be compared directly to assess performance across different subscales.

Several important features of item performance are illustrated in Figure Figure2A 2 A for an item from the PCAT-S. First, each of the option characteristic curves (a solid line probability curve for each response option) increases rapidly with small increases in timeliness. For example, the probability of option 1 being endorsed increases rapidly from 0.0 to 0.6 over a narrow region of timeliness, –3.0 to –1.5. Second, each option tends to be endorsed most frequently in a specific range of timeliness. For example, option 2 is more likely to be endorsed than any other option within the timeliness range of –1.0 to 0.0. Third, the regions over which each option is most likely to be endorsed are ordered, left to right, in the same way as the option scores (weights, 1 to 4). That is, the region in which option 2 is most likely to be endorsed falls between the regions in which option 1 and option 3 are most likely to be endorsed. Finally, together, the options for an item span the full continuum of accessibility, from –3 to +3. Most positive options are endorsed only at high levels of timeliness (e.g., option 5), whereas most negative options are endorsed only at low levels of timeliness (e.g., option 1).

In contrast, Figure Figure2B 2 B shows an item from the PCAT-S with four response options, but only options 1 and 4 are endorsed frequently. Options 2 and 3 do not provide any meaningful additional information, and the response scale functions essentially as a binary option. However, the responses cover specific and distinct areas of timeliness, making the item very discriminating, as illustrated by the steep slope of the item characteristic curve.

Figure Figure2C 2 C illustrates a problematic item. The response option curves do not peak rapidly nor in specific areas of timeliness, and the response options do not seem to be ordinal. The item characteristic curve is almost flat, showing little capacity for discrimination. It does not perform well to measure timeliness, which may not be surprising given that it asks about helpfulness of staff.

Each of the techniques described above offers a different method of examining item and subscale performance; applied together, they offer a comprehensive assessment of how the selected instruments measure performance of core primary healthcare attributes. The attribute-specific results are presented in individual papers elsewhere in this special issue.

The strength of this study was our analysis across instruments, which allowed us to identify sub-dimensions within an attribute. Sometimes a sub-dimension is unique to one subscale; sometimes, more than one is represented. This approach will help program evaluators select the measures appropriate for their needs. Another consideration will be the missing values, and evaluators may choose not to offer “not sure” or “not applicable” options to minimize information loss. As with any study, results are sample-dependent, and items that do not function well in the present sample may still function well in a different sample of individuals or a different healthcare setting. However, the results of our study show that most of these measures can be used with confidence in the Canadian context. Ideally, any difficulties identified should be viewed as opportunities for improvement, potentially by rewriting, rewording or clarifying questions.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).

Contributor Information

Darcy A. Santor, School of Psychology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON.

Jeannie L. Haggerty, Department of Family Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, QC.

Jean-Frédéric Lévesque, Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC.

Frederick Burge, Department of Family Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS.

Marie-Dominique Beaulieu, Chaire Dr Sadok Besrour en médecine familiale, Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC.

David Gass, Department of Family Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS.

Raynald Pineault, Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC.

- Borowsky S.J., Nelson D.B., Fortney J.C., Hedeen A.N., Bradley J.L., Chapko M.K. 2002. “VA Community-Based Outpatient Clinics: Performance Measures Based on Patient Perceptions of Care.” Medical Care 40 ( 7 ): 578–86 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Du Toit M. 2003. IRT from SSI: Bilog-mg, Multilog, Parscale, Testfact. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International [ Google Scholar ]

- Flocke S. 1997. “Measuring Attributes of Primary Care: Development of a New Instrument.” Journal of Family Practice 45 ( 1 ): 64–74 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gorsuch R.L. 1983. Factor Analysis (2nd ed). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum [ Google Scholar ]

- Grol R., Wensing M.Task Force on Patient Evaluations of General Practice 2000. “Patients Evaluate General/Family Practice: The EUROPEP Instrument.” Nijmegen, Netherlands: Centre for Quality of Care Research, Raboud University [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haggerty J.L., Burge F., Beaulieu M.-D., Pineault R., Beaulieu C., Lévesque J.-F., et al. 2011. “Validation of Instruments to Evaluate Primary Healthcare from the Patient Perspective: Overview of the Method.” Healthcare Policy 7 ( Special Issue ): 31–46 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haggerty J.L., Lévesque J.-F., Santor D.A., Burge F., Beaulieu C., Bouharaoui F., et al. 2011. “Accessibility from the Patient Perspective: Comparison of Primary Healthcare Evaluation Instruments.” Healthcare Policy 7 ( Special Issue ): 94–107 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jöreskog K.G., Sörbom D. 1996. LISREL 8: User's Reference Guide. Chicago: Scientific Software International [ Google Scholar ]

- Kline R.B. 1998. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford Press [ Google Scholar ]

- Ramsay J.O. 1991. “Kernel Smoothing Approaches to Nonparametric Item Characteristic Curve Estimation.” Psychometrika 56 : 611–30 [ Google Scholar ]

- Ramsay J.O. 2000. TESTGRAF: A Program for the Graphical Analysis of Multiple-Choice Test and Questionnaire Data (Computer Program and Manual). Montreal: McGill University, Department of Psychology; Retrieved June 11, 2011. < ftp://ego.psych.mcgill.ca/pub/ramsay/testgraf/TestGrafDOS.dir/testgraf1.ps >. [ Google Scholar ]

- Safran D.G., Kosinski J., Tarlov A.R., Rogers W.H., Taira D.A., Lieberman N., Ware J.E. 1998. “The Primary Care Assessment Survey: Tests of Data Quality and Measurement Performance.” Medical Care 36 ( 5 ): 728–39 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Santor D.A., C. Coyne J. 2001. “Examining Symptom Expression as a Function of Symptom Severity: Item Performance on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression.” Psychological Assessment 13 : 127–39 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Santor D.A., Ramsay J.O. 1998. “Progress in the Technology of Measurement: Applications of Item Response Models.” Psychological Assessment 10: 345–59 [ Google Scholar ]

- Santor D.A., Ramsay J.O., Zuroff D.C. 1994. “Nonparametric Item Analyses of the Beck Depression Inventory. Examining Gender Item Bias and Response Option Weights in Clinical and Nonclinical Samples.” Psychological Assessment 6 : 255–70 [ Google Scholar ]

- Santor D.A., Zuroff D.C., Ramsay J.O., Cervantes P., Palacios J. 1995. “Examining Scale Discriminability in the BDI and CES-D as a Function of Depressive Severity.” Psychological Assessment 7 : 131–39 [ Google Scholar ]

- SAS Institute 2003. SAS User's Guide: Statistics (Version 9.1). Cary, NC: SAS Institute [ Google Scholar ]

- Shi L., Starfield B., Xu J. 2001. “Validating the Adult Primary Care Assessment Tool.” Journal of Family Practice 50 ( 2 ): n161w–n171w [ Google Scholar ]

- Stewart A.L., Nápoles-Springer A.M., Gregorich S.E., Santoyo-Olsson J. 2007. “Interpersonal Processes of Care Survey: Patient-Reported Measures for Diverse Groups. Health Services Research 42 ( 3 Pt. 1 ): 1235–56 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Introduction to Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling

Cite this chapter.

- Matthew W. Gallagher &

- Timothy A. Brown

8103 Accesses

24 Citations

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is a powerful and flexible statistical technique that has become an increasingly popular tool in all areas of psychology including educational research. CFA focuses on modeling the relationship between manifest (i.e., observed) indicators and underlying latent variables (factors).

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Allison, P. D. (2003). Missing data techniques for structural equation models. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112 , 545–557.

Article Google Scholar

Arbuckle, J. L. (2010). IBM SPSS Amos 19 User’s Guide . Crawfordville, FL: Amos Development Corporation.

Google Scholar

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2009). Exploratory structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 16 , 397–438.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 51 , 1173–1182.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indices in structural equation models. Psychological Bulletin, 28 , 97–104.

Bentler, P. M. (2006). EQS for Windows (Version 6.0) [Computer software]. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software.

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin , 88 , 588–606.

Bollen, K. A., & Curran, P. J. (2006). Latent curve models: A structural equation perspective. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience.

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research . New York: Guilford Press.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research , 21 , 230–258.

Burkholder, G. J., & Harlow, L. L. (2003). An illustration of a longitudinal cross-lagged design for larger structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling , 10 , 465–486.

Campbell, D. T., & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitraitmultimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56 , 81–105.

Chemers, M. M., Hu, L., & Garcia, B. (2001). Academic self-efficacy and first-year college student performance and adjustment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93 , 55–65.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9 , 233–255.

Cole, D. A., & Maxwell, S. E. (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Myths and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112 , 558–577.

Collins, L. M. (2006): Analysis of longitudinal data; The integration of theoretical model, temporal design, and statistical model, Annual Review of Psychology 57 , 505–528.

Eliason, S. R. (1993), Maximum likelihood estimation . Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis . New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Fox, J. (2006). Structural equation modeling with the sem package In R. Structural Equation Modeling, 13 , 465–486.

Gallagher, M. W., & Lopez, S. J. (2008, August). The unique effects of hope and self-efficacy on academic performance . Poster presented at the American Psychological Association 116th Annual Convention, Boston, MA.

Hu, L., & Benter, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6 , 1–55.

Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1996). LISREL 8: User’s reference guide . Chicago: Scientific Software International.

Kenny, D. A., & Kashy, D. A. (1992). The analysis of the multitrait-multimethod matrix using confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 112 , 165–172.

Kline, R. B. (2010). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Little, T. D., Bovaird, J. A., & Card, N. A. (Eds.). (2007). Modeling contextual effects in longitudinal studies . Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Little, T. D., Bovaird, J. A., & Widaman, K. F. (2006). On the merits of orthogonalizing powered and interaction terms: Implications for modeling interactions among latent variables. Structural Equation Modeling, 13 , 497–519.

Little, T. D., Slegers, D. W., & Card, N. A. (2006). A non-arbitrary method of identifying and scaling latent variables in SEM and MACS models. Structural Equation Modeling, 13 , 59–72.

MacCallum, R. C., & Austin, J. T. (2000). Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annual Review of Psychology, 51 , 201–226.

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1 , 130–149

MacCallum, R. C., Roznowski, M., & Necowitz, L. (1992). Model modifications in covariance structure analysis: The problem of capitalization on chance. Psychological Bulletin, 111 , 490–504.

MacKinnon, D. P. (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis . Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

McArdle, J. J. (2009). Latent variable modeling of differences and changes with longitudinal data. Annual Review of Psychology, 60 , 577–605.

McDonald, R. P., & Ho, M. R. (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods , 7 , 64–82.

Muthén, B. O., & Asparouhov, T. (2008). Growth mixture modeling: Analysis with non-Gaussian random effects. In G. Fitzmaurice, M. Davidian, G. Verbeke, & G. Molenberghs (Eds.), Longitudinal data analysis (pp. 143–165). Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC.

Muthén, B. O., & Muthén, L. K. (2008–2012). Mplus user’s guide . Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA.

Muthén, L. K. and Muthén, B. O. (2002). How to use a Monte Carlo study to decide on sample size and determine power. Structural Equation Modeling, 4 , 599–620.

Neale, M. C., Boker, S. M., Xie, G., Maes, H. H. (2003). Mx: Statistical modeling. 6 . Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Commonwealth University/.

Preacher, K. J., & Coffman, D. L. (2006, May). Computing power and minimum sample size for RMSEA [Computer software]. Available from http://www.quantpsy.org/ .

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891.

Preacher, K. J., Wichman, A. L., MacCallum, R. C., & Briggs, N. E. (2008). Latent growth curve modeling . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15 , 209–233.

SAS Institute (2005). SAS/STAT User’s Guide , Version 9. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

Schafer. J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7 , 147–177.

Schoemann, A. D. (2010). Latent variable moderation . Retrieved January 22nd, 2012, from http://www.quant.ku.edu/pdf/16.1%20latent%20variable%20moderation.pdf .

Selig, J. P., & Preacher, K. J. (2009). Mediation models for longitudinal data in developmental research. Research in Human Development, 6 , 144–164

Steiger, J. H., & Lind, J. C. (1980). Statistically-based tests for the number of common factors . Paper presented at the annual Spring Meeting of the Psychometric Society in Iowa City. May 30, 1980.

Teo, T., & Khine, M. S. (Eds.) (2009). Structural equation modeling in educational research: Concepts and applications . Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Thurstone, L. L. (1947). Multiple-Factor Analysis . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Auckland, New Zealand

Timothy Teo

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Sense Publishers

About this chapter

Gallagher, M.W., Brown, T.A. (2013). Introduction to Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling. In: Teo, T. (eds) Handbook of Quantitative Methods for Educational Research. SensePublishers, Rotterdam. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6209-404-8_14

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6209-404-8_14

Publisher Name : SensePublishers, Rotterdam

Online ISBN : 978-94-6209-404-8

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of the 9-item utrecht work engagement scale in a multi-occupational female sample: a cross-sectional study.

- 1 Department of Health and Caring Sciences, Faculty of Health and Occupational Studies, University of Gävle, Gävle, Sweden

- 2 Department of Public Health and Caring Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

Objective: The aim of the present study was to use exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to investigate the factorial structure of the 9-item Utrecht work engagement scale (UWES-9) in a multi-occupational female sample.

Methods: A total of 702 women, originally recruited as a general population of 7–15-year-old girls in 1995 for a longitudinal study, completed the UWES-9. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed on half the sample, and CFA on the other half.

Results: Exploratory factor analysis showed that a one-factor structure best fit the data. CFA with three different models (one-factor, two-factor, and three-factor) was then conducted. Goodness-of-fit statistics showed poor fit for all three models, with RMSEA never going lower than 0.166.

Conclusion: Despite indication from exploratory factor analysis (EFA) that a one-factor structure seemed to fit the data, we were unable to find good model fit for a one-, two-, or three-factor model using CFA. As previous studies have also failed to reach conclusive results on the optimal factor structure for the UWES-9, further research is needed in order to disentangle the possible effects of gender, nationality and occupation on work engagement.

Introduction

Work engagement has been described as the conceptual opposite of burnout ( González-Romá et al., 2006 ), and as such belongs in the area of positive psychology, or “the study of the conditions and processes that contribute to the flourishing or optimal functioning of people, groups, and institutions”( Gable and Haidt, 2005 ). In occupational health, the study of work engagement focuses on factors that contribute to job satisfaction as well as long-term mental and physical health ( Torp et al., 2013 ).

Work engagement has been described as “a positive work-related state of mind characterized by vigor, dedication and absorption.” ( Schaufeli et al., 2002 ). These three concepts are in their turn described as “characterized by high levels of energy and mental resilience while working, the willingness to invest effort in one’s work, and persistence even in the face of difficulties” (Vigor), “characterized by a sense of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, pride and challenge” (Dedication) and “characterized by being fully engrossed in one’s work, so that time passes quickly and one has difficulties in detaching oneself from work” (Absorption) ( Schaufeli et al., 2002 ).

The idea that these three concepts – Vigor, Dedication and Absorption – together form the foundation of work engagement forms the basis of the Utrecht work engagement scale (UWES) ( Schaufeli et al., 2002 ). Originally a 17-item questionnaire (UWES-17), the original authors have shortened it to a 9-item version (UWES-9) in order to reduce the burden on the respondents and minimize attrition ( Schaufeli et al., 2006 ). The items are in the form of statements (for example “At my work, I feel bursting with energy” (Vigor); “I find the work that I do full of meaning and purpose” (Dedication); “When I am working, I forget everything else around me” (Absorption) which the respondent reads and reacts to by indicating one of 7 points on a scale ranging from 0 (“Never”) to 6 (“All the time”). The 9-item version, which has been psychometrically tested in various countries and samples ( Ho Kim et al., 2017 ; Petrović et al., 2017 ), will be the focus of the present study.

In a number of studies, conducted in different countries and with samples of various make-ups, UWES-9 scores have been found to be associated with work performance, job satisfaction, and mental and physical health ( Bakker and Matthijs Bal, 2010 ; Christian et al., 2011 ). The scores have also been found to predict general life satisfaction and the frequency of sickness absence ( Leijten et al., 2015 ).

Despite its wide-spread use, both the UWES-17 and the UWES-9 have been the subject of some criticism. Mills et al. (2012) have argued that the methodology when developing the original scale contained flaws in relation to the establishment of its factorial structure. Criticism has also been voiced regarding the factor structure of the instrument, one of the main points being that the three subscales Vigor, Dedication and Absorption are very closely correlated with each other, casting doubt on the three-factor structure’s superiority to a one-factor structure using only the total score on the scale ( Kulikowski, 2017 ). For example, Shirom has argued that the three dimensions of Vigor, Dedication, and Absorption were not theoretically deduced and that they overlap each other conceptually ( Shirom, 2003 ). In support of this, several studies have failed to confirm the three-factor structure in their samples. Previous studies have also tested other factor structures – for example, Kulikowski (2019) tested a two-factor structure, with Dedication and Vigor merged into a single factor and Absorption constituting a second factor ( Kulikowski, 2019 ). A 2017 review by Kulikowski investigated the factorial structure of the UWES-17 and UWES-9 as reported in 21 different studies, conducted in 24 countries using samples from a variety of occupations and countries. The author found that of the 11 studies investigating the UWES-9, three confirmed the one-factor structure, three the three-factor structure, four studies found these two factor structures to be equivalent, and one study failed to support either alternative ( Kulikowski, 2017 ). Thus, Kulikowski (2017) concluded that no definitive recommendations could be made based on the review. He also pointed out the importance, in light of these inconclusive results, that further research be conducted on the factorial structure of the UWES-9 in different samples ( Kulikowski, 2017 ).

Only one previous study has tested the factorial validity of the UWES-9 in a Swedish sample ( Hallberg and Schaufeli, 2006 ). In their sample of 186 information communication technology consultants (of whom 37% were women), both the one-factor and three-factor structures were supported by data, leading the authors to draw the conclusion that both options were equally strong. If the scope is broadened to take in all the Scandinavian countries, a Norwegian study using a large multi-occupational sample ( n = 1266, 67% women) found support for the three-factor structure, but also found that the three latent factors were strongly correlated, leading the authors to suggest that a one-factor structure might also be suitable (Nerstad, Richardsen and Martinussen, 2010). In addition to this, a Finnish study found, in a sample of 9404 workers in several different occupational sectors, that both the one-factor and three-factor structures may reasonably be used ( Seppälä et al., 2009 ). Similarly to the Norwegian study, the results showed that the three subscales of Vigor, Dedication, and Absorption were highly correlated.

Interestingly, it has been suggested that as a rule, levels of work engagement tend to be higher in countries in Northwestern Europe, and lower in Southern Europe, on the Balkans and in Turkey ( Schaufeli, 2018 ). However, Sweden is identified as an exception to this rule, with relatively low levels of work engagement compared to, for example, Norway, where levels were found to be higher ( Schaufeli, 2018 ).

The 9-item UWES is a widely used instrument to measure work engagement. Despite this, the optimal factorial structure of the UWES-9 remains unknown. A recent review of factorial structure for the UWES-9 and UWES-17 failed to reach conclusive results, and indicated that more research was needed to determine the appropriate default factorial structure ( Kulikowski, 2017 ). Many previous studies have used relatively small samples, and many have reached inconclusive results, including the only previously published Swedish study. In order to adequately assess and potentially target work engagement in future interventions using Swedish populations, it is important to examine and ascertain whether Swedish people hold the same representation of work engagement. Thus, the aim of the present study was to use exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to investigate the factorial structure of the 9-item UWES in a multi-occupational Swedish sample.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

The women in the all-female sample used for the current study were originally recruited in 1995, when they were aged between 7 and 15 years, through stratified randomization from a number of school classes in Sweden. They were sampled to represent a general population of girls, and were participants in a longitudinal study aiming to identify risk and protective factors for the development of eating disorders. More details about the recruitment and follow-up can be found elsewhere ( Westerberg-Jacobson et al., 2010 ). The data used in the current study was collected in 2015, as part of the 20-year follow-up data collection. The participants remaining in the study were asked to complete a number of questionnaires, including the UWES-9, and those who indicated that they were currently working full-time or part-time (not on long-term sick-leave, parental leave, unemployed, or studying full-time) were included in the current study. Thus, the final sample consisted of 702 women, aged between 26 and 37, who completed a Swedish translation of the 9-item UWES ( Schaufeli et al., 2006 ). Aside from the UWES-9, data was collected on level of education (primary school, secondary education or university education), although not on specific occupation.

Ethics Statement

The project was approved by the Regional Ethics Board in Uppsala, Sweden (2014/401). At the time of the original recruitment, in 1995, the participants and their parents gave written informed consent to take part in the study. At the time of the data collection for the present study, the participants again gave their written informed consent and were reminded that their participation was voluntary, could be withdrawn any time without giving a reason, and that all information would be treated confidentially. All participants who completed the data collection were offered a cinema ticket or a department store gift voucher as thanks.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using Stata 14 ( StataCorp, 2015 ) and SPSS ( IBM Corp, 2016 ) statistical software packages. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity were used to assess the suitability of the data for factor analysis ( Dziuban and Shirkey, 1974 ). Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was first performed unrotated, using maximum likelihood extraction and eigenvalues > 1. Additionally, we performed EFA with promax rotation and enforcing three-factor solution in order to test the theoretical structure of the UWES-9. In this analysis, we also used maximum likelihood extraction. Additionally, Parallel Analysis (using principal axis factoring) and Velicer’s Minimum Average Partial test were conducted ( O’Connor, 2000 ).

CFA was then performed using maximum likelihood estimation.

In order to investigate the models’ goodness of fit, a number of statistics were used: Overall χ 2 ( Hooper et al., 2008 ), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ( Steiger, 1990 ; Hooper et al., 2008 ), Akaike’s information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-lewis index (TLI) ( Bentler, 1990 ), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMSR) ( Hooper et al., 2008 ).

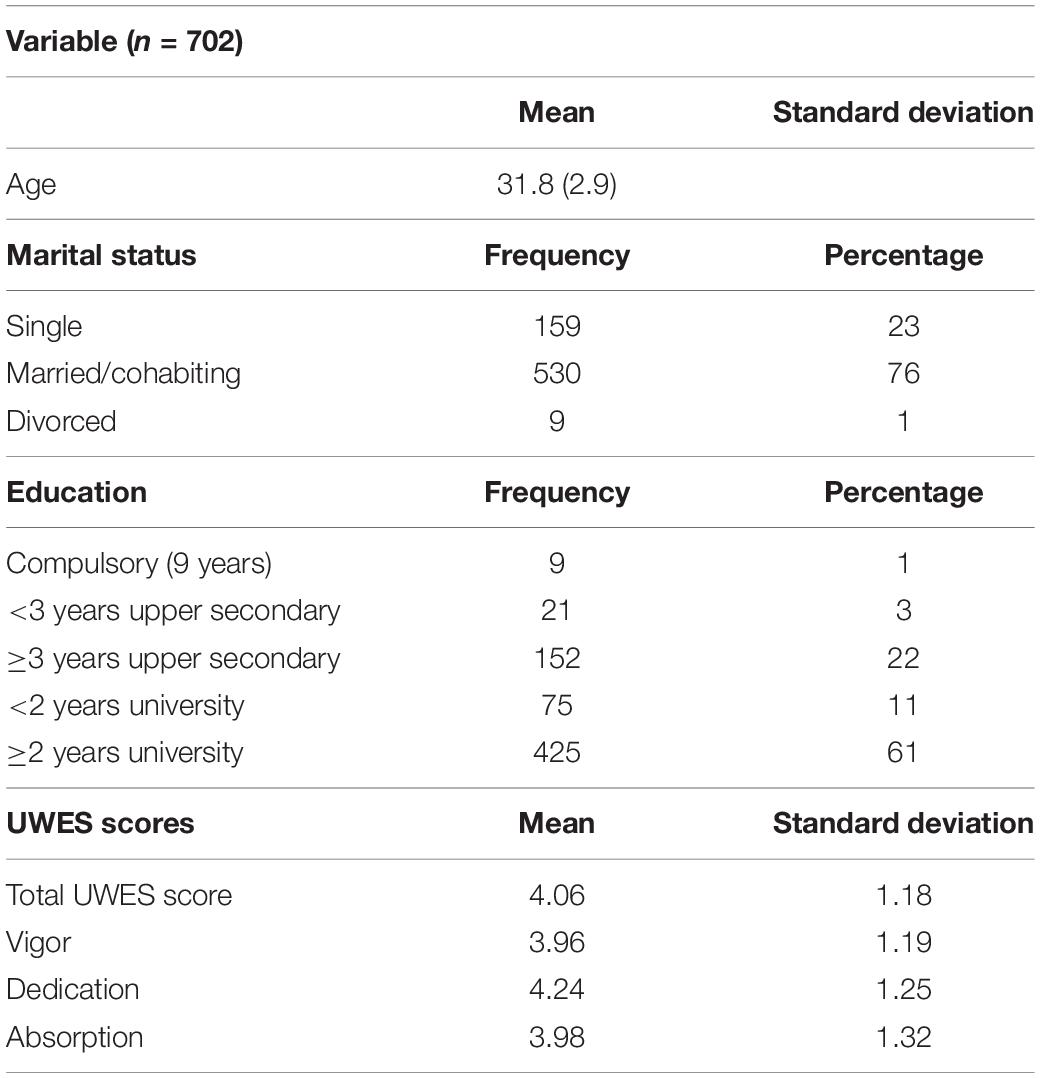

Demographic information about the participants can be seen in Table 1 . Data on highest attained educational level was collected, and showed that the majority of the sample had attended at least 3 years of higher education.

Table 1. Demographic information about the participants.

The inter-item correlation was relatively high for all items of the UWES-9, ranging between 0.524 and 0.849. The three subscales Vigor (V), Dedication (D), and Absorption (A) also showed high correlation with each other (0.79–0.84). In addition to this, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated and found to be 0.947, indicating very good internal consistency.

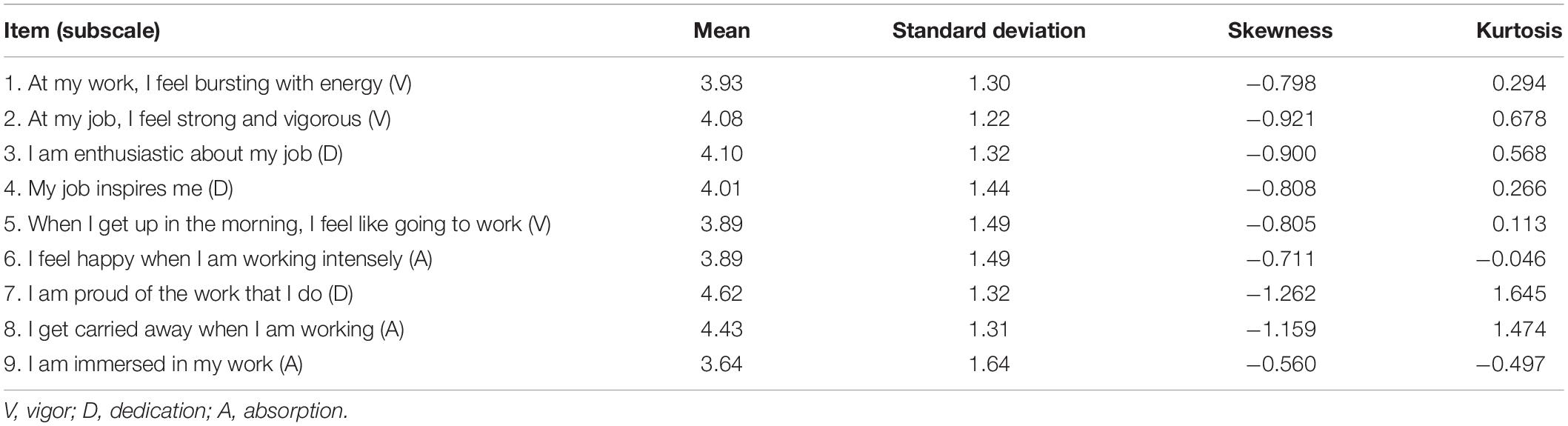

The items were checked for skewness and kurtosis and these are shown in Table 2 , together with the wording of the items, their respective subscales, mean scores and standard deviations. Based on the Shapiro-Wilks test and a visual inspection of their histograms, normal Q-Q plots and box-plots, we concluded that the UWES item distributions had a skewness range between −0.560 and −1.262 (SE = 0.094) and a kurtosis range between −0.046 and 1.645 (SE = 0.187) ( Table 2 ). The values for skewness and kurtosis were deemed to be within the range for maximum likelihood estimation. We also tested the multivariate normality using Doornik-Hansen test, the Mardia skewness test and Mardia kurtosis test. For all of these, the p -value was <0.0001, indicating non-normality.

Table 2. Items with their subscales, mean scores, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis.

In the next step, the sample was randomly divided in two, so that mutually independent samples were obtained for the EFA and CFA, respectively. As the number of participants with missing values was very low (19 individuals, corresponding to 3% of the entire sample), only observations without any missing items were used, resulting in 683 observations in total, 341 for the EFA and 342 for the CFA.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

The results of the EFA suggested that one factor explained over 70% of the variance. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy was 0.922, indicating that the sample was adequate, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity gave a p -value of <0.001. A Scree plot of the eigenvalues was constructed (not shown) and shown to be strongly in favor of the one-factor structure. The χ2 for this model was 332,43 (df 27).

Velicer’s MAP test was also performed, both in the original ( Velicer, 1976 ) and revised version ( O’Connor, 2000 ). This also strongly pointed toward a one-factor solution.

Finally, in the Parallel Analysis, the raw data eigenvalue from the actual data was greater than eigenvalues of the 95th percentile of the distribution of random data for four factors, in disagreement with the MAP test and the EFA ( O’Connor, 2000 ).

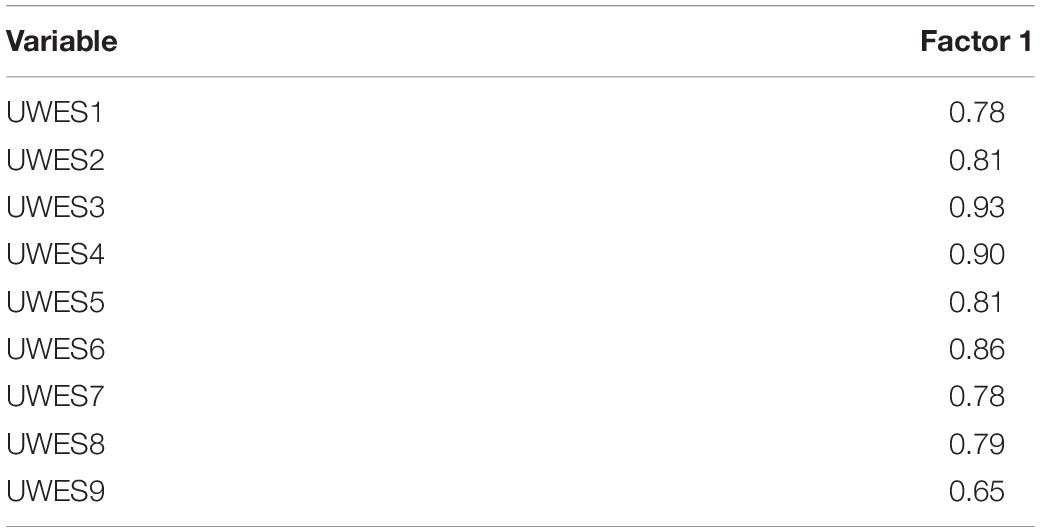

Table 3 shows the factor loadings. As the table shows, all loadings were relatively high, ranging from 0.65 to 0.93.

Table 3. Factor loadings.

In addition to this, we also conducted EFA using promax rotation and enforcing a three-factor structure, in order to compare the fit of the theoretical dimensionality of the UWES-9 with the one-factor solution we found in our sample. The χ2 for this model was 45,72 (df 12) ( p < 0.001). The items did not load on their expected factors “Dedication” had 4 items (3, 4, 5, 6), “Vigor” had 2 items (1, 2), and “Absorption” had 3 items (7, 8, 9).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

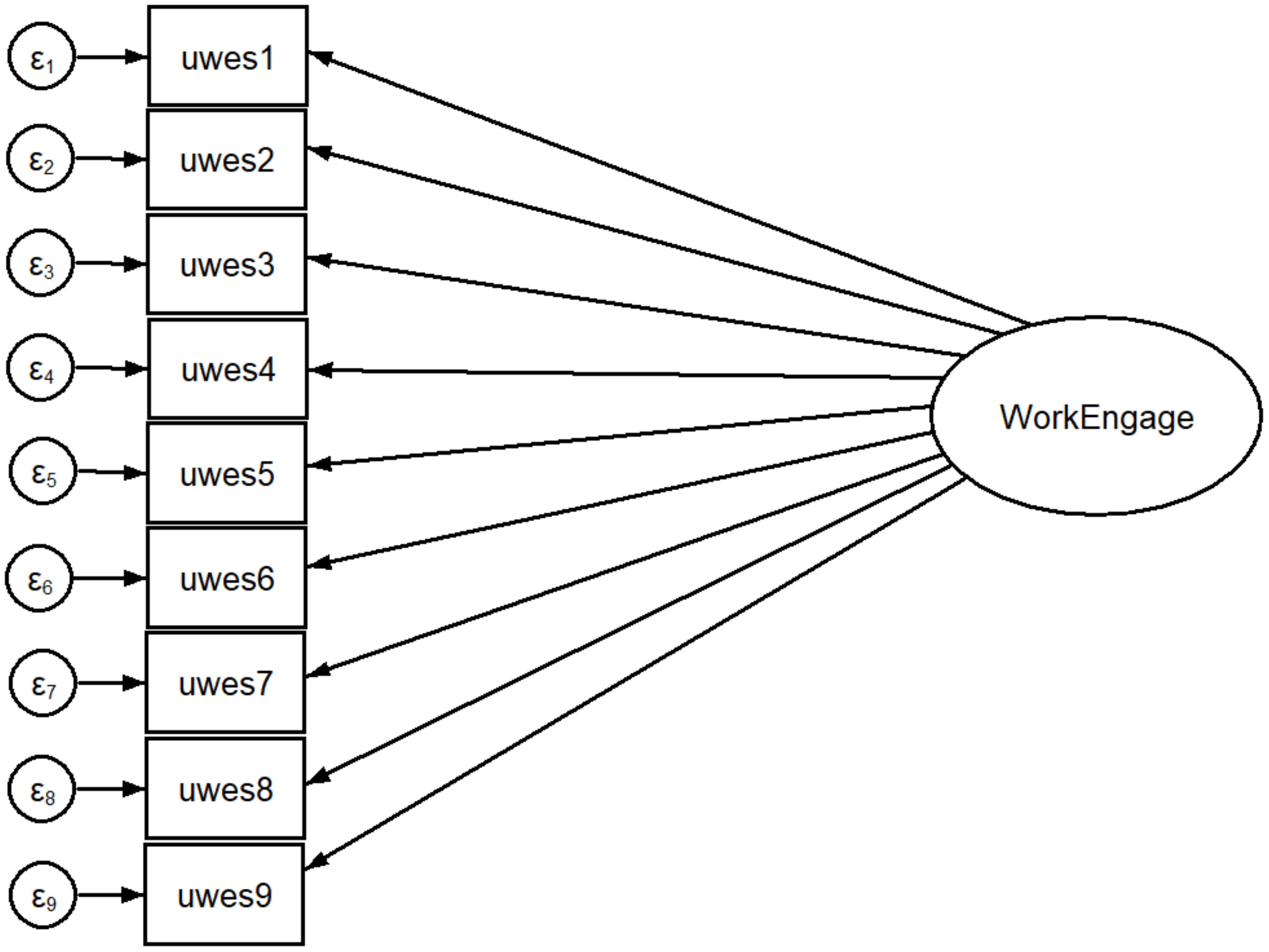

As the EFA suggested a one-factor solution, as described above, the model was first specified with just one latent factor (Work Engagement). Standardized coefficients were used and the estimation model was maximum likelihood, since the items showed acceptable skewness and kurtosis ( Table 2 ). Observations with missing values were excluded.

In order to also test the theoretical foundation of the UWES-9, we performed CFA with the original three subscales Vigor, Dedication and Absorption. Additionally, inspired by a previous study by Kulikowski (2019) , who also tested a two-factor model, we also performed CFA using this structure.

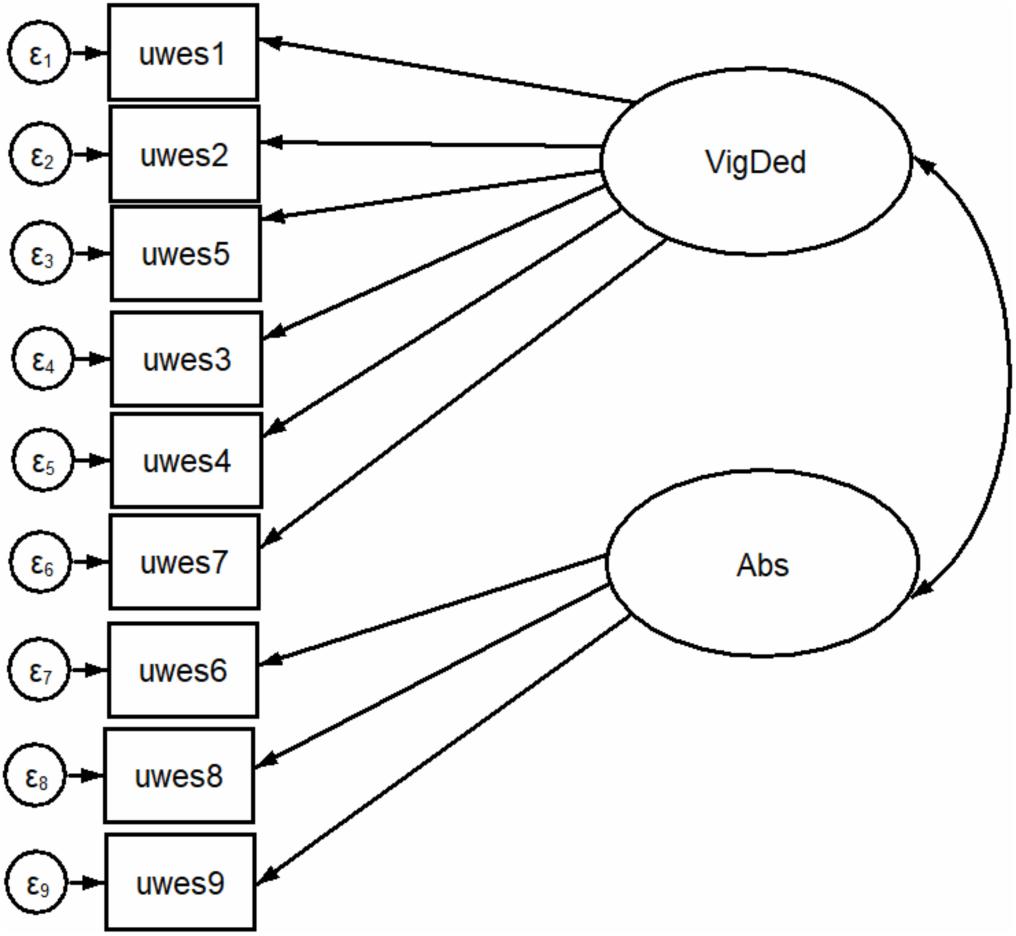

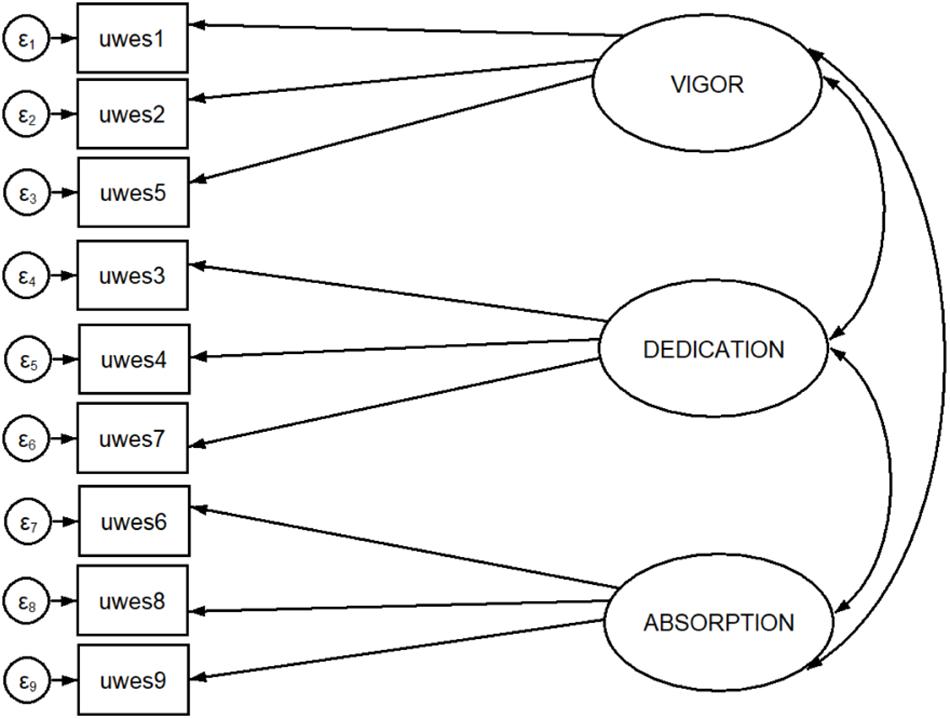

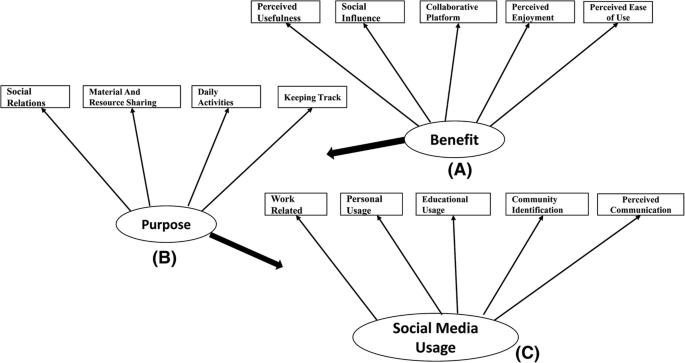

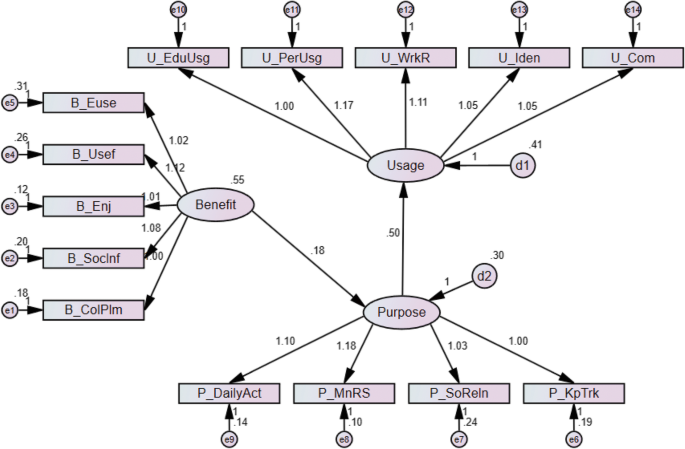

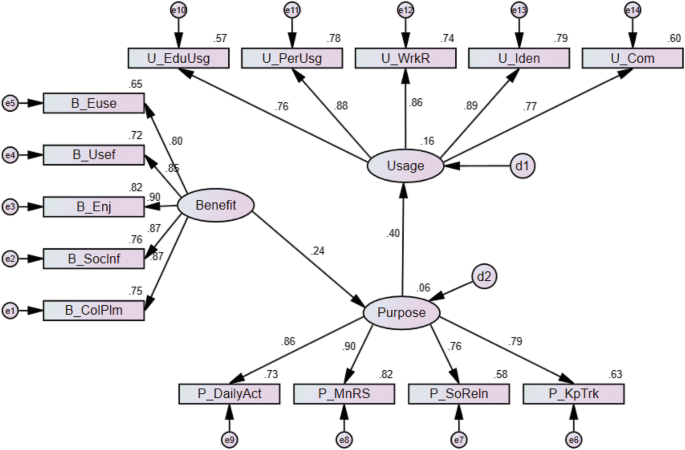

Figures 1 – 3 show all the attempted models.

Figure 1. One-factor structure with maximum likelihood estimation.

Figure 2. Two-factor structure with maximum likelihood estimation.

Figure 3. Three-factor structure with maximum likelihood estimation.

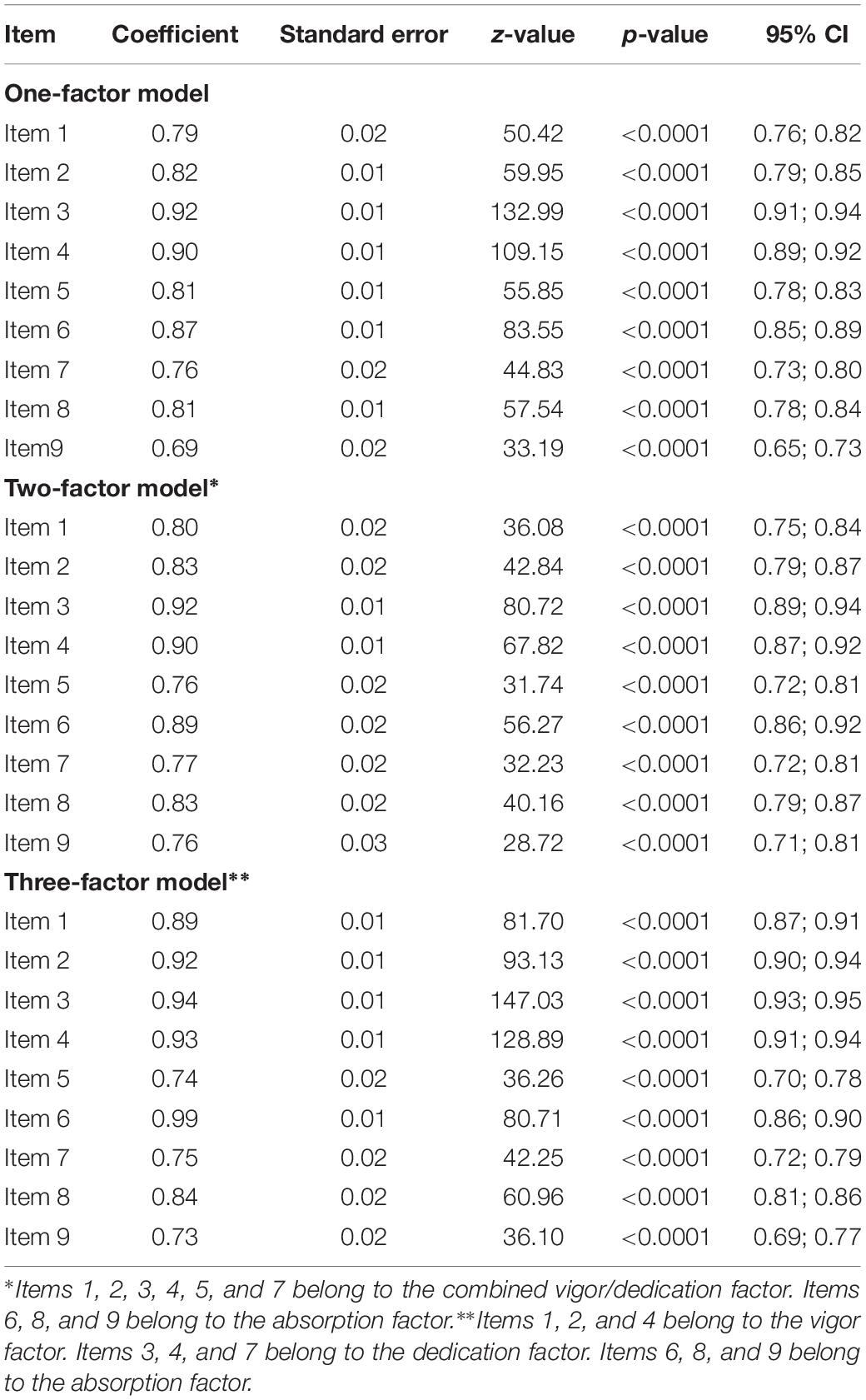

Table 4 shows the coefficients of the hypothesized relationships, together with their z -values, standard errors, 95% confidence intervals and p -values, for all tested models.

Table 4. All models’ standardized coefficients and associated data.

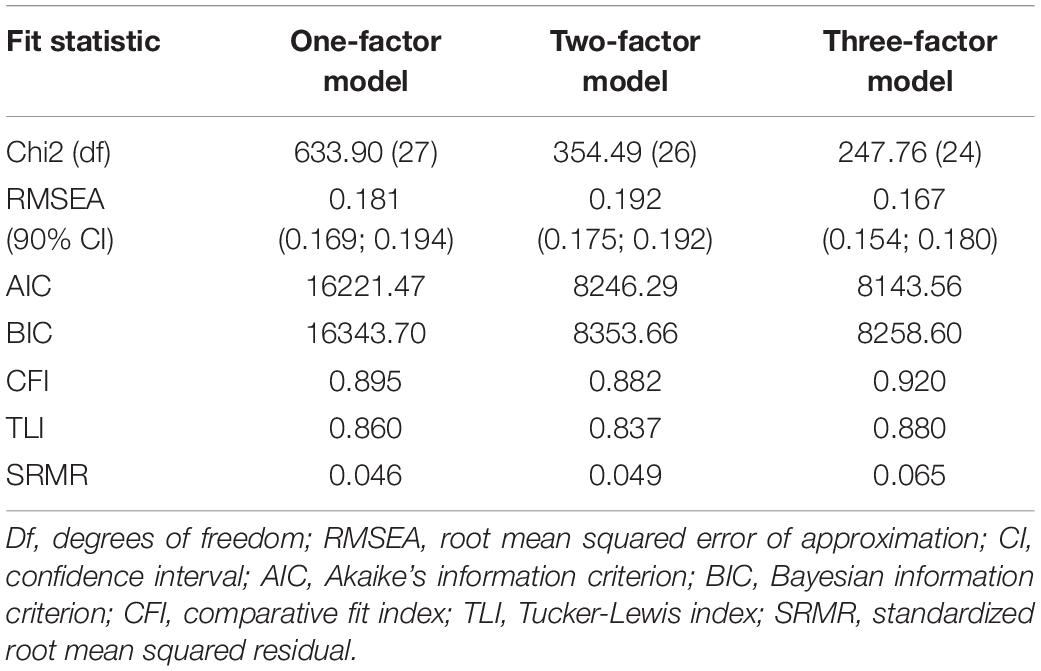

After estimating the models, goodness-of-fit statistics were obtained, as described in the section “Materials and Methods,” above. As can be seen in Table 5 , none of the models showed very good fit, with RMSEA ranging between 0.181 and 0.167. Also, CFI and TLI, which should preferably be above 0.95 ( Hooper et al., 2008 ) remained below this value for all tested models.

Table 5. Goodness-of-fit statistics for all models.

The aim of the present study was to use exploratory and CFA to investigate the factorial structure of the UWES in a multi-occupational sample of Swedish women. The EFA seemed to mainly favor a one-factor solution, which was shown to explain over 70% of the variance.

Confirmatory factor analysis was then performed using three different models: one-factor, two-factor, and three-factor. Goodness-of-fit statistics were obtained for all models and showed that none of them showed overall good fit, with RMSEA never going below 0.167 and CFI and TLI remaining relatively low ( Table 5 ).

As previously mentioned, a recent review of the factorial structure of the UWES showed inconclusive results, with some included studies showing best fit for a one-factor structure, some showing best fit for a three-factor structure, and some showing an equally good (or poor) fit for both ( Kulikowski, 2017 ). This indicates a need for further research into the underlying factors impacting the factor structures in various samples.

One of the studies included in the Kulikowski review found that neither the one-factor nor the three-factor structure of the UWES-9 was a good fit for their data ( Wefald et al., 2012 ). This used a sample similar to ours, both in terms of size (382 vs. 342) and level of education (in both samples, around 60% had a university degree or higher). The RMSEA was 0.18 and 0.16 for the one-factor and three-factor structures, in the Wefald study, almost identical to 0.181 and 0.167 for our study.

A previous study by Kulikowski (2019) has also attempted a two-factor structure, merging Dedication and Vigor into a single factor, letting Absorption constitute the second factor ( Kulikowski, 2019 ). We attempted the same model in the present study, but in agreement with Kulikowski’s results, failed to obtain satisfactory goodness of fit.

The only previous Swedish study using the UWES used a sample consisting of 186 information technology (IT) consultants (37% women) and found that both the one-factor and three-factor structure showed similar fit, with RMSEA of 0.13 and CFI of 0.97 for both ( Hallberg and Schaufeli, 2006 ). Although this sample was Swedish, it was different from that of the present study in other significant ways, such as gender (a majority were male) and occupation (all the participants were IT consultants, whilst ours was a multi-occupational sample), which may explain the differences in the results.

If our results are compared with those of other studies also using multi-occupational samples, several of them have, in agreement the Swedish study by Hallberg and Schaufeli (2006) , found that both the one-factor and three-factor structures may be used. For example, this was the case for Schaufeli et al. (2006) with a very large multinational sample of 14521 individuals.

These differing results support the recommendation made by Kulikowski (2017) , namely that each study using the UWES-9 should undertake their own factor analysis based on their own sample, and make a decision on which structure to use based on their own results ( Kulikowski, 2017 ). In addition to this, and in agreement with the current study, several previous studies have found that none of the factor structures tested have shown an acceptable fit ( Hallberg and Schaufeli, 2006 ; Wefald et al., 2012 ). Subsequently, researchers looking to use a measure of work engagement may wish to use another instrument in parallel with the UWES.

The present study has strengths, as well as weaknesses. The relatively large sample size of approximately 700 women made it possible to randomly divide the group into half so that both an exploratory and a CFA could be undertaken. The fact that the sample consisted exclusively of women may be seen both as a strength and as a weakness. On the one hand, it ensures that the results are not skewed by an uneven gender balance, but on the other hand our results should not be assumed to be generalizable to males. An Iranian study investigating determinants of work engagement in hospital staff found no significant effect of gender ( Mahboubi et al., 2014 ). However, a Dutch study exploring work engagement and burnout in veterinarians found that women rated their work engagement lower than men, indicating that gender differences may vary with different occupational groups, nationalities, or other, hitherto unknown factors ( Mastenbroek et al., 2014 ).

In addition to this, in terms of generalizability, it should be acknowledged that the sample used in the present study should be considered to represent the white-collar population, based on the higher-than-average level of education. More than 60% of the participants reported having at least 3 years of university education, whilst the national average for women between the ages of 25 and 34 is 35%, according to Statistics Sweden ( Statistics Sweden, 2017 ). In addition to this, only Swedish-speaking girls participated. However, 21.6% had immigrated or had parents who had immigrated to Sweden, which is in line with the population in general ( Statistics Sweden, 2018 ).

The present study used a large, multi-occupational female sample to explore the factorial structure of the UWES-9. Despite indication from EFA that a one-factor structure best fit the data, we were unable to find good model fit for a one-, two-, or three-factor model using CFA. As previous studies have also failed to reach conclusive results on the optimal factor structure for the UWES-9, further research is needed in order to disentangle the possible effects of gender, nationality and occupation on work engagement. Until such data exists, researchers would be wise to conduct their own factor analysis in order to determine whether the total score, the three dimensions representing Vigor, Dedication and Absorption, or even a two-factor structure is applicable for their sample.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

This project was approved by the Regional Ethics Board (2014/401). At the time of the data collection for the present study, the participants were again asked to give their consent and reminded that their participation was voluntary, could be withdrawn any time without giving a reason, and that all information would be treated confidentially. All participants who completed the data collection were offered a cinema ticket or a department store gift voucher as thanks.

Author Contributions

MW contributed to the conception and design of the work, performed the analyses, and drafted the manuscript. JW and ML contributed to the conception and design of the work, took part in the data collection and analyses, and revised the work critically. All authors approved the final version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

This work was supported by Capio Research Foundation, the Signe and Olof Wallenius Foundation, and the Thuring Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Bakker, A. B., and Matthijs Bal, P. (2010). Weekly work engagement and performance: a study among starting teachers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 83, 189–206. doi: 10.1348/096317909X402596

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 107, 238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bollen, K. A. (2014). Structural Equations with Latent Variables. New York, NY: Wiley.

Google Scholar

Christian, M. S., Adela, S. G., and Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work engagement: a quantitative review and test of its relation with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 64, 89–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01203.x

IBM Corp (2016). SPSS for Windows. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Dziuban, C. D., and Shirkey, E. C. (1974). When is a correlation matrix appropriate for factor analysis? Some decision rules. Psychol. Bull. 81, 358–361. doi: 10.1037/h0036316

Gable, S. L., and Haidt, J. (2005). What (and why) is positive psychology? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 9, 103–110. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.103

González-Romá, V., Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., and Lloret, S. (2006). Burnout and work engagement: independent factors or opposite poles? J. Vocat. Behav. 68, 165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2005.01.003

Hallberg, U. E., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2006). “Same same” but different? Can work engagement be discriminated from job involvement and organizational commitment? Eur. Psychol. 11, 119–127. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.11.2.119

Ho Kim, W., Park, J. G., and Kwon, B. (2017). Work engagement in South Korea. Psychol. Rep. 120, 561–578. doi: 10.1177/0033294117697085

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., and Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 6, 53–60.

Kulikowski, K. (2017). Do we all agree on how to measure work engagement? Factorial validity of Utrecht work engagement scale as a standard measurement tool – A literature review. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 30, 161–175. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.00947

Kulikowski, K. (2019). One, two or three dimensions of work engagement? Testing the factorial validity of the Utrecht work engagement scale on a sample of Polish employees. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 25, 241–249. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2017.1371958

Leijten, F., van den Heuvel, S. G., van der Beek, A. J., Ybema, J. F., Robroek, S. J., and Burdorf, A. (2015). ‘Associations of work-related factors and work engagement with mental and physical health: a 1-year follow-up study among older workers. J. Occup. Rehabil. 25, 86–95. doi: 10.1007/s10926-014-9525-6

Mahboubi, M., Ghahramani, F., Mohammadi, M., Amani, N., Mousavi, S. H., Moradi, F., et al. (2014). Evaluation of work engagement and its determinants in Kermanshah hospitals staff in 2013. Glob. J. Health Sci. 7, 170–176. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v7n2p170

Mastenbroek, N. J., Jaarsma, A. D., Demerouti, E., Muijtjens, A. M., Scherpbier, A. J., and van Beukelen, P. (2014). Burnout and engagement, and its predictors in young veterinary professionals: the influence of gender. Vet. Rec. 174:144. doi: 10.1136/vr.101762

Mills, M., Culbertson, S., and Fullagar, C. (2012). Conceptualizing and measuring engagement: an analysis of the Utrecht work engagement scale. J. Happiness Stud. 13, 519–545. doi: 10.1007/s10902-011-9277-3

Nerstad, C. G. L., Richardsen, A. M., and Martinussen, M. (2010). Factorial validity of the Utrecht work engagement scale (UWES) across occupational groups in Norway. Scand. J. Psychol. 51, 326–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00770.x

O’Connor, B. P. (2000). SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer’s MAP test. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 32, 396–402. doi: 10.3758/bf03200807

Petrović, I. B., Vukelić, M., and čizmić, S. (2017). Work engagement in Serbia: psychometric properties of the Serbian version of the Utrecht work engagement scale (UWES). Front. Psychol. 8:1799. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01799

Schaufeli, W. (2018). Work engagement in Europe: relations with national economy, governance and culture. Organ. Dyn. 47, 99–106.

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., and Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire a cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 66, 701–716. doi: 10.1177/0013164405282471

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-romá, V., and Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 3, 71–92.

Seppälä, P., Mauno, S., Feldt, T., Hakanen, J., Kinnunen, U., Tolvanen, A., et al. (2009). The construct validity of the Utrecht work engagement scale: multisample and longitudinal evidence. J. Happiness Stud. 10, 459–481. doi: 10.1007/s10902-008-9100-y

Shirom, A. (2003). “Feeling vigorous at work? The construct of vigor and the study of positive affect in organizations,” in Emotional and Physiological Processes and Positive Intervention Strategies (Research in Occupational Stress and Well-being , Vol. 3, eds P. L. Perrewe and D. C. Ganster, (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 135–164. doi: 10.1016/s1479-3555(03)03004-x

StataCorp (2015). Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp.

Statistics Sweden (2017). Befolkningens Utbildning. Available at: http://www.scb.se/uf0506 (accessed July 2, 2018).

Statistics Sweden (2018). Folkmängd Och Befolkningsförändringar 2017. Available at: http://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/statistik-efter-amne/befolkning/befolkningens-sammansattning/befolkningsstatistik/pong/statistiknyhet/folkmangd-och-befolkningsforandringar-20172/ (accessed July 2, 2018).

Steiger, J. H. (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: an interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behav. Res. 25, 173–180. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4

Torp, S., Grimsmo, A., Hagen, S., Duran, A., and Gudbergsson, S. B. (2013). Work engagement: a practical measure for workplace health promotion? Health Promot. Int. 28, 387–396. doi: 10.1093/heapro/das022

Velicer, W. F. (1976). Determining the number of components from the matrix of partial correlations. Psychometrika 41, 321–327. doi: 10.1007/bf02293557

Wefald, A. J., Mills, M. J., Smith, M. R., and Downey, R. G. (2012). A comparison of three job engagement measures: examining their factorial and criterion-related validity. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 4, 67–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-0854.2011.01059.x

Westerberg-Jacobson, J., Edlund, B., and Ghaderi, A. (2010). A 5-year longitudinal study of the relationship between the wish to be thinner, lifestyle behaviours and disturbed eating in 9-20-year old girls. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 18, 207–219. doi: 10.1002/erv.98

Keywords : confirmatory factor analysis, exploratory factor analysis, Utrecht work engagement scale, work engagement, occupational psychology

Citation: Willmer M, Westerberg Jacobson J and Lindberg M (2019) Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the 9-Item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale in a Multi-Occupational Female Sample: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychol. 10:2771. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02771

Received: 10 April 2019; Accepted: 25 November 2019; Published: 06 December 2019.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2019 Willmer, Westerberg Jacobson and Lindberg. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mikaela Willmer, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution