- International Network

- Policy Papers

- Opinion Articles

- Historians' Books

- History of Government Blog

- Editorial Guidelines

- Case Studies

- Consultations

- Hindsight Perspectives for a Safer World Project

- Global Economics and History Forum

- Trade Union and Employment Forum

- Parenting Forum

Renewing the War on Waste

Dr henry irving | 24 september 2021.

Executive Summary

- The Environment Bill contains ambitious provisions for waste collection and has the potential to transform recycling in England.

- DEFRA’s proposals echo those of the Ministry of Supply during the Second World War. An understanding of this history draws attention to lessons and warnings that are applicable today.

- The implementation of a compulsory recycling scheme in summer 1940 led to a short term reduction in collections and long term doubts about the system. The staged implementation of consistent collections would avoid similar problems in October 2023 and could lead to higher rates of adoption in the long term.

- Wartime encouraged a temporary shift from private to communal dustbins. DEFRA should require local authorities to consider the viability of similar schemes before granting technical exemptions to consistent collection for reasons of urban geography.

- Surveys carried out in the 1940s showed that local messages were effective but had a greater impact when combined with other appeals, especially personal ones. DEFRA needs to devote more resources to explaining the historic changes included in the Environment Bill.

- A lengthy delay between the implementation of consistent collections and the introduction of clear labelling risks causing frustration – with people being told to do the right thing, only to find that the system makes it hard for them to do so. Similar problems in summer 1940 made later appeals less effective.

Introduction

The government’s long-awaited Environment Bill is passing through the final stages of Parliamentary scrutiny and is on track to become law around the time of the United Nation’s COP26 climate conference in Glasgow. The bill contains wide-ranging provisions that are designed to address climate change and biodiversity loss, while improving resource management.

One of its least controversial parts will signal a historical change to the way waste is managed in the United Kingdom, with far reaching provisions for waste collection in England (it is a devolved responsibility).This part of the Environment Bill is rooted in the 2018 resource and waste strategy published by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). That document established a commitment to ‘move towards a circular economy’ by minimising waste and promoting reuse and recycling. The ambition remains for England to ‘become a world leader in using resources efficiently and reducing the amount of waste we create as a society’ .

The most significant of DEFRA’s proposals echo policies that were introduced by the Ministry of Supply in 1940. An understanding of this history is necessary to avoid repeating wartime mistakes and retain support for the proposals.

Words and Actions

The Environment Bill has been broadly welcomed by campaigners and green groups, many of whom have warned of a gulf between words and actions since 2018. The scope of legislative change is a marked advance on the government’s previous waste prevention plan . Published in 2013, this aimed to reduce ‘the quantity and impact of waste produced’ by introducing incentives for behaviour change. The waste reduction charity WRAP calculates that 387,000 tonnes of waste were prevented between 2013-19, 103,000 tonnes of which would not have been prevented in the absence of the plan. The larger figure accounts for roughly 0.002 per cent of the waste produced during the same period. ‘We have a very long way to go indeed’ , warns Libby Peak, Green Alliance’s head of resource strategy.

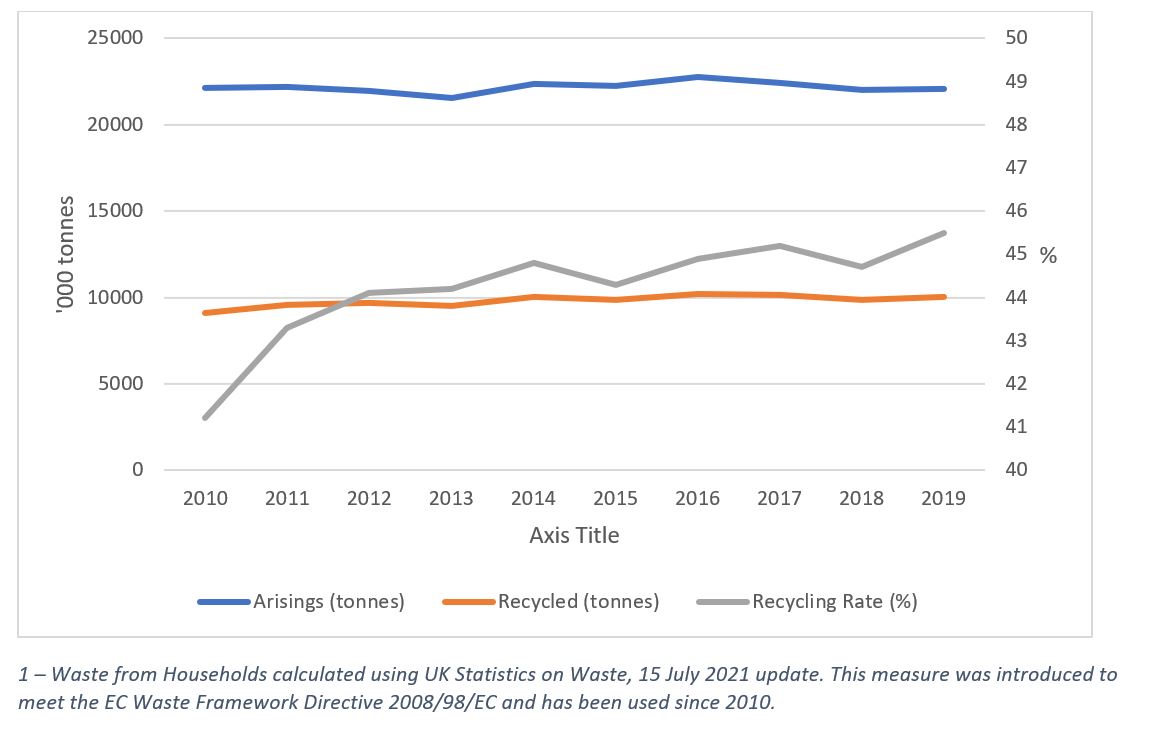

In their defence, DEFRA points to a rise in English household recycling rates from 11 per cent in 2001 to 45.5 per cent in 2019, and a fall in the amount of household waste produced in the same period. The pace of change has, however, slowed considerably since 2011 and statistics collected by DEFRA and show that English recycling rates have been stuck around 45 per cent for the past seven years. The current target of 65 per cent by 2035 will require a significant change in behaviour.

The lack of progress has been variously attributed to a lack of funding from central government and a lack of consistency between local authorities. The national average certainly conceals significant variations. The 2019-20 figures show that household recycling rates in England ranged from 18.8 per cent (in Barrow in Furness, Cumbria) to 64. 1 per cent (in Three Rivers, Hertfordshire). At a UK-level, England has lagged behind Wales (56.4 per cent in 2019) since 2010 and was overtaken by Northern Ireland (50.6 per cent in 2019) in 2017.

In practice, these figures mean that the average household refuse bin in England contains large amounts of material that simply should not be there. A WRAP study carried out in 2017 found that discarded food made up 18 per cent of the household waste stream, paper and card another 18 per cent, plastic 9 per cent, glass 7 per cent, metals 4 per cent and textiles 4 per cent. The majority of this waste was recyclable, and able to be collected or deposited at communal facilities like bottle and textile banks.

The COVID-19 pandemic and Britain’s departure from the European Union have created new challenges. Local authority services have been seriously disrupted by illness, self-isolation and the shortage of HGV drivers in the UK. At least 18 local authorities have had to delay bin collections as a result of these factors. The pandemic has also led to shifts in consumer behaviour. Plastic waste has increased sharply , due to a fall in the price of virgin materials and an increased demand for single-use items like masks, while the boom in online shopping has upset the market for recycled cardboard as so many boxes ended up contaminated. At the same time, most local authorities have seen – sometimes dramatic – increases in household recycling. In Leeds, for instance, the closure of hospitality venues led to an estimated 37 per cent increase in the amount of glass recycled at communal bottle banks.

Echoes from 1940

The Environment Bill is designed to reinvigorate recycling by transforming existing practises. If passed, it will lead to:

- Consistent recycling collections by local councils in England.

- Weekly food waste collections by local councils in England.

- Additional charges on single use plastics and a deposit return scheme for drinks containers.

- An extension to producer responsibility schemes for packaging.

- Clearer labelling so consumers can easily identify recyclable and non-recyclable materials.

These policies are designed to work in combination. The aim is for all households to have access to a food waste and recycling service for the same ‘core set’ of materials (including, at a minimum, paper and cardboard, plastic, cans and glass). This standardisation will in turn allow all packaging to be labelled simply ‘Recycle’ or ‘Do not recycle’. The initial costs of collection and communication will be funded by central government, but eventually recouped from the producer responsibly scheme.

To make this work, DEFRA has developed an implementation plan with support from WRAP and has consulted with local authorities and the waste industry. It hopes consistent collections and the first phase of the producer responsibility scheme will begin in October 2023, with mandatory labelling from 2025-27. This timeline will be confirmed when the Environment Bill becomes law.

This is not the first time the UK government have sought to rationalise and reinvigorate household recycling. During the Second World War, the government used emergency legislation to divert materials into the war economy. The declaration of hostilities and prospect of material shortages jolted the government into action. On 5 October 1939, the Ministry of Supply established a special directorate to develop a system for both civilian and military recycling – which was then called ‘salvage’. Its work on the home front was developed in three phases.

The first was focused on increasing capacity and ran until June 1940. At the start of the war, only a handful of local authorities collected salvage directly from households, although around 70 had mechanical separation and reclamation plants capable of extracting materials from the waste stream after collection. The amount returned to industry was estimated to account for at most 2.5 per cent of peacetime refuse. To increase this number, the Ministry of Supply encouraged local authorities to develop plans for the collection or reclamation of recyclable materials and required councils to submit monthly salvage statistics.

In the second phase, from June 1940, a series of minimum standards were enforced by emergency powers. In line with the Environment Bill, a compulsory direction required local authorities to implement a ‘regular and dependable’ scheme for the collection of paper, metal and household bones. These rules were the first legal powers to compel kerbside recycling in the UK and remained in force until 1949. The change was supported by a large-scale publicity campaign, which is considered in more detail below.

The third phase involved the tightening of controls over the public. In November 1940, it became an offense to remove salvageable material without the owner’s consent. These rules were strengthened in March 1942, when the Salvage of Waste Materials (No. 2) Order made it a criminal offence to burn, throw away or contaminate waste paper or cardboard. This was subsequently extended to cover rags, rope, string and rubber. Although these orders introduced fines and even the prospect of prison sentences, they were primarily designed to emphasise the importance of engagement and used to caution against careless behaviour.

These measures sat alongside legal controls capping prices and limiting the amount of materials available for civilian uses. In February 1940, for example, a quota control was introduced for paper. This was a form of industrial rationing that imposed limits on the amount of paper available compared to a baseline of pre-war consumption. The quota was initially set at 60 per cent and was progressively reduced to 37.5 per cent by the end of 1941.

Consistent Collections

The current government’s plan for consistent recycling collection extends beyond the system introduced in June 1940. Despite the wartime emergency, there was never a one-sized-fits-all approach during the Second World War. Proposals to nationalise the waste system were rejected as impractical and local authorities remained free to choose the most suitable forms of collection for their area. The government also recognised the additional challenges faced in rural areas and the head start enjoyed by larger councils with more established refuse collection services. For these reasons, the compulsory direction to collect paper, metal and bones was initially limited to local authority areas with populations over 10,000, before being extended to smaller towns with 5-10,000 inhabitants in March 1941.

Services are today more consistent and DEFRA acknowledge that exceptions may be applied in places where consistent collections are technically or economically impractical, or where the environmental benefit cannot be proven. These caveats are designed to account for issues arising from the geographical location of properties or the availability of recycling infrastructure. However, the disparities in recycling rates within England suggest that the implementation of a consistent system to level up recycling rates will not be unproblematic, even where exemptions do not apply.

DEFRA explains its decision to apply rules uniformly by noting that their core materials are currently collected by 76 per cent of local authorities. It is impossible to accurately calculate the percentage of local authorities collecting paper, metal and bones prior to the compulsory direction in June 1940 as the wartime government did not know how many councils should have submitted returns. However, the self-reported statistics collated by the Ministry of Supply show that the number fell by roughly 16 per cent during the summer of 1940 because of problems with collection and processing caused by the new rules. This highlights the need to tackle the root causes of current disparities rather than hoping consistent collections will be a magic bullet. It also hints at the importance of secure markets for secondary materials, which are far from certain in the case of plastics. A deliberately staged approach to implementation could avoid teething problems and ensure a higher rates adoption in the long term by safeguarding against claims of economic impracticality.

Wartime experience also highlights just how important bins will be to the success of the DEFRA scheme. This is another example where the one-sized-fits-all approach risks increased levels of opting out. The proposal that core materials will be ‘collected separately from each other’ has already led to questions about how households will store multiple bins and containers, while DEFRA explains that ‘type of housing stock’ could be a legitimate reason for an exception. Its suggestion that new bins could be introduced across England was strongly rejected in an earlier consultation.

Most urban households before the Second World War disposed of their refuse in a metal dustbin that was either approved of or supplied by their council. On collection days, refuse workers would empty the bin and return it to the property, whether to a backyard, front doorstep, or communal store. The implementation of recycling schemes led to a proliferation of bins and containers and increased the time taken to complete collection rounds.

As the war went on, many councils replaced private dustbins with communal ones. Existing bins were moved from backyards and onto the street, where they were repainted and labelled for specific materials. Such moves were not unanimously welcomed (there were frequent complaints about foul smelling food waste bins, for example) but the use of communal facilities allowed local authorities to increase the frequency of collection from a smaller number of sites. If DEFRA retains its commitment to uniform separation, it should also require local authorities to consider the viability of similar strategies before granting technical exemptions for reasons of urban geography.

Communal approaches will be most important in high-density settings. During the Second World War, flats were commonly identified as having the lowest recycling rates and most problems with compliance. DEFRA has specifically included flats in its for plan consistent collection but has also identified them as a likely example where exemptions will apply. To avoid a repeat of wartime problems, work needs to be done in advance of implementation, rather than waiting for issues to arise.

Explaining Changes

The provisions in the Environment Bill are primarily focused on businesses and local government, reflecting its emphasis on producer responsibility and the legal responsibility of local councils to collect household waste. Nevertheless, changes in waste management ultimately depends on individual behaviour change. Household recycling is, after all, an activity that starts in the home.

DEFRA’s 2018 waste strategy argued that ‘incentives and nudges, when they accompany good services and communications, can make a real difference to people’s engagement in recycling’. This belief is reflected in various studies of recycling behaviour. It is accepted that the availability of recycling services has the greatest impact on participation, but that engagement can be significantly improved through active promotion. The latest guidance from DEFRA notes that it will develop advice on communications for local authorities, as well as working with WRAP to support a national publicity campaign.

The value of local messaging emerged clearly during the Second World War. In August 1943, the government’s wartime social survey asked people what spurred them to recycle. Of the 46 per cent who said there were times they made ‘a special effort’, 32 per cent referred to local campaigns compared to 21 per cent for national appeals. These findings were echoed in similar surveys about other publicity campaigns. The success of localised appeals encouraged the Ministry of Supply to establish a regional publicity machinery responsible for working with local authorities to adapt publicity to suit local practices.

DEFRA is right to place emphasis on local communication and should be applauded for its commitment to fund councils to carry out this work. Wartime experience suggests they will be best placed to explain how consistent collections will be introduced in their areas. This point is backed up by a recent YouGov poll commissioned by the author based on the wartime social survey. This found that the best remembered recycling publicity today is found on bins and waste collection vehicles (being mentioned by 60% of respondents). Yet the wartime example also suggests that these messages need to be accompanied by a more ambitious national campaign.

WRAP estimates that recognition of its ‘Recycle Now’ symbol is 66 per cent, but that only 7 per cent have seen or heard of its annual ‘Recycle Week’ (held since 2004) and 14 per cent recognise its ‘Britain Recycles’ campaign. By contrast, a May 1942 wartime social survey about attitudes towards government instructions found that recycling was the most recognised campaign on the home front, being mentioned by some 31 per cent of respondents. This finding can be explained by both the strength of local campaigns during 1942 and the sustained national publicity that accompanied the compulsory direction to collect paper, metal and bones in summer 1940.

The publicity campaign that accompanied the 1940 change included an instructional leaflet, various broadcasts and newsreel interviews, a newspaper advertising campaign, posters and a film. Its scale resulted from a belief that national salience was a necessary foundation for targeted local appeals. While the specific messages used does not easily translate into the twenty first century, wartime techniques could be harnessed to explain the changes that will take place in October 2023. The move to consistent collections is a historic change and should be treated as such.

The most important single part of the 1940 campaign was the involvement of ordinary citizens through a nationwide canvass organised by the Women’s Voluntary Services with support from the Ministry of Supply. Between August and October 1940, these volunteers hand delivered almost 9 million copies of the government’s instructional leaflet. In almost all cases, they also spoke with the householder about the scheme in their area. Personal appeals like these were frequently cited as having had most impact – a belief that is echoed by contemporary studies finding that community norms have a significant impact on recycling rates. The success of mutual assistance schemes and community litter picks during the COVID-19 pandemic suggests that there is scope to organise similar activities through local Zero Waste groups or national bodies like Keep Britain Tidy. The planning and funding for such activities needs to begin now.

After Implementation

The wartime history of recycling also contains clear warnings about public attitudes after implementation. As noted in the section on ‘Consistent Collections’, the number of local authorities collecting paper and metal fell in summer 1940. The uneven working of the system coloured public perceptions and led to scepticism about local authorities’ abilities to manage. The push-back would likely have been more serious had it not been for a late decision to delay enforcing controls over the public until the system had bedded in. Those responsible for promoting the scheme nevertheless complained that publicity had outrun machinery – making future appeals more difficult.

At various points during the war, frustrations about service delivery spilled over into a more general scepticism about recycling in general. In March 1942, for instance, the Wartime Social Survey found that 40 per cent of people expressed doubt about the uses to which salvage was put. Towards the end of the war, the suspension of the collection of tins (which only very few local authorities had the capacity to process) seems to have increased doubts about the need to recycle, leading to a wider falling-off of engagement.

The YouGov poll commissioned by the author show that people are currently willing to give the benefit of the doubt. The survey found that 46 per cent thought that ‘good use’ was made of recycling in their area, compared to 13 per who disagreed. High levels of engagement have nevertheless created comparable problems to those experienced during the war

WRAP has measured recycling attitudes and behaviours since 2004. Its most recent survey show that recycling is very well-established in the UK, with 89 per cent of respondents saying that they recycled ‘regularly’ compared to just 3 per cent who said ‘rarely’ or ‘never’. However, the same data reveals that 80 per cent were putting items into their recycling bin that could not be processed in their local area. Put simply, most households act based on what they think ‘should’ – rather than ‘can’ – be recycled. A recent project in Reading came to a similar conclusion, finding that residents with contaminated bins often ‘felt like they were exemplary recyclers as they had [their own] ideas of what could be recycled’.

DEFRA hopes that the roll out of consistent collection and clear labelling will overcome these problems, but its current timetable for implementation will not see the introduction of mandatory label changes until 2025 at the earliest. The risk is that this will cause similar frustrations to those experienced in the summer of 1940 – with people being told to do the right thing, only to find that the system makes it hard for them to do so. The introduction of consistent collections for glass bottles and jars will reduce some contamination but will do nothing to resolve the confusion caused by different forms of plastic packaging. History suggests that, to be most effective, either both changes need to be brought into line or additional funding needs to be assigned to tackle contamination during the transition.

The wartime government’s compulsory direction to collect paper, metal and bones was an attempt to rationalise a recycling system that had been hastily constructed. The Ministry of Supply accepted that a one-sized-fits-all approach was impractical and thought carefully about how to communicate the policy. However, the implementation was still botched, creating frictions that had a long-term impact on public attitudes.

Recycling is today far more entrenched than in 1940 and DEFRA’s goals are more ambitious than the Ministry of Supply’s. The challenge is to get the implementation right. An understanding of what happened during the Second World War highlights that DEFRA should:

- Consider the staged implementation of consistent collections to avoid problems in implementation and ensure a secure market for secondary materials.

- Promote communal collection as an alternative to multiple containers or expensive standardised bins.

- Commit to a more ambitious communication strategy, with local instructions supported by a national campaign and community-led activities.

- Bring forward the roll out of clear labelling to tackle contamination and avoid potential frustration.

- Irving, Henry

- Environment

Further Reading

Tim Cooper, ‘Challenging the “refuse revolution”: war, waste and the rediscovery of recycling, 1900–50’, Historical Research , 81:214 (2008), 710-3

Henry Irving, ‘Paper Salvage in Britain during the Second World War’, Historical Research , 89:244 (2016), 373-93

Henry Irving, ‘The War on Waste: Using urban history to inspire behavioural change’, Urban History , 48:2 (2021), 307-319

Henry Irving, ‘“We want everybody’s salvage!”: Recycling, voluntarism and the people’s war’, Cultural and Social History , 16:2 (2019), 165-84

Mark Riley, ‘From salvage to recycling: New agendas or same old rubbish’, Area , 40:1 (2008), 79-89.

Susan Strasser, Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash (New York: Metropolitan Books, 1999)

Peter Thorsheim, Waste into Weapons: Recycling in Britain during the Second World War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015)

About the author

Henry Irving is a senior lecturer in public history at Leeds Beckett University. He is a historian of the British Home Front during the Second World War, specialising in popular responses to wartime conditions, legislation, and propaganda.

Related Opinion Articles

The blitz can show us how to respond to a tragedy, henry irving | 16 june 2017, wars on waste, then and now, henry irving | 22 january 2018, papers by author, papers by theme, popular papers, subscribe to our newsletter.

Sign up to receive announcements on events, the latest research and more!

To complete the subscription process, please click the link in the email we just sent you.

We will never send spam and you can unsubscribe any time.

H&P is based at the Institute of Historical Research, Senate House, University of London.

We are the only project in the UK providing access to an international network of more than 500 historians with a broad range of expertise. H&P offers a range of resources for historians, policy makers and journalists.

Publications

Policy engagement, news & events.

Keep up-to-date via our social networks

- Follow on Twitter

- Like Us on FaceBook

- Watch Us on Youtube

- Listen to us on SoundCloud

- See us on flickr

- Listen to us on Apple iTunes

War on Waste: From Waste to Resource

ABC Education

- X (formerly Twitter)

Curated clips from Series 2 of War on Waste. How can we reuse or recycle our waste?

Have you ever thought about what happens to the empty plastic bottles and packaging that once held your favourite drinks and snacks? Or where your old mobile phone or tablet might end up after you've upgraded to the latest model?

Since we started using plastic 65 years ago, we have generated 6.3 billion tonnes of plastic waste globally. Out of all this, 9 percent has been recycled and 12 percent has been incinerated. This means that 79 percent is either still in landfills or drifting in our oceans.

Australian households create more than 666,000 tonnes of plastic packaging waste every year. More than 5 million tonnes of food in Australia also ends up in landfill each year, which is enough to fill 9000 Olympic sized swimming pools.

So what can we do to tackle our waste problem? Read on to find out more about where our waste ends up and how we can reduce, reuse and recycle more of it.

Table of contents:

- 1. What happens to plastic packaging?

- 2. Misconceptions lead to unnecessary waste

- 3. Why go straw-free?

- 4. Ditching unnecessary plastic packaging

- 5. Changing our perspective on waste

- 6. Food waste can be valuable

- 7. E-waste: What happens to your old electronics?

- 8. Improving our recycling systems

- 9. How to make reusable t-shirt bags

- 10. Recycling e-waste to raise money for food charities

- 11. Fighting hospital waste

War on Waste

10 ideas for teaching kids about sustainable living

ABC 7.30: Cash for cans in Western Australia?

Essay: IN DEFENSE OF WASTE

VISITORS are invariably shocked. They see Americans cheerfully discarding cars, refrigerators or washing machines from which a French peasant, say, or a Greek shopkeeper would still get years of use. They are amazed at the serviceable suits that an American sends off to the Salvation Army the minute an elbow gives way or a knee frays. Tin cans that would roof a million Caribbean cottages are tossed onto scrap heaps. Perfectly good buildings are torn down and replaced by new ones with an economic life expectancy of only 50 years. Waste, outrageous waste, cry the critics—and by no means only foreign critics. U.S. social commentators loudly deplore the “waste makers,” as do politicians and poets. “In America everything goes to waste,” complains Poet Karl Shapiro. “Waste in the States is the national industry.” “I regard waste as the continuing enemy of our society,” Lyndon Johnson has warned.

Different critics mean different things by waste. The most obvious definitions are heedless opulence, which, as it were, drops too much from the table, and the readiness to discard the only slightly old. A secondary target is the artificial stimulation of the consumer to buy in vast quantities things he never wanted until he was told. Often such complaints sound highly plausible, particularly when reinforced by a wrecking ball hitting an old landmark or an infuriating commercial peddling a clearly needless “improvement” in some trivial product. Yet waste is not what it seems to be. The term implies a moral as well as an economic judgment, and its meaning varies with both setting and purpose.

Taking a shower may be a waste in the desert but not in a city. Blowing up a $16 million rocket to get to the moon may seem wasteful to some—but it scarcely is, in view of what space exploration contributes to science and the economy, not to say the human spirit. War is undoubtedly wasteful, not only in matériel but also in the irretrievable waste of lost lives. Yet even here, it is a question of values—most American wars have been fought for human causes and values that its citizens considered no waste, whether it was abolition of slavery at home or freedom in the world at large.

Time v. Trouble

The concept of waste still held by most of the world grows out of scarcity, a situation in which materials are short and labor is the cheapest thing around—a situation that in many cases socialism has helped to perpetuate. In the U.S., the notion of waste also grows from the Puritan belief that negligent use of material things is sinful. “Waste not, want not,” saith the preacher, and the phrase still echoes in the minds of older Americans not too far removed from the time when wax drippings were conserved to recast into new candles, or when boys made pocket money by straightening out bent nails.

Today people who save string or old clothes in attics are likely to run into psychologists who tell them that such hoarding is neurotic, or economists who prove it uneconomical, or architects who simply do not provide enough storage space for it. The new American maxim, Columbia University’s John Kouwenhoven has suggested, should be: “Waste not, have not.” This does not signify that waste has become accepted in the U.S.—on the contrary. It is only that its meaning has changed. Neither Cotton Mather nor Malthus nor Marx anticipated a society in which only 15% of the population would produce all the food and goods that the whole nation could reasonably need or, for that matter, a society so productive that it could afford, for the first time in history, to have more people in services than in production.

The result is that the modern American is not bothered by the waste of materials. What concerns him is time—his time. In the abundant U.S. economy, materials are relatively cheaper than labor. If something he can buy and throw away can save an American time, he does not feel it is a real waste.

Viewed in this light, much that appears materially wasteful becomes economically unwasteful. The American businessman, whose profits may depend on his avoidance of waste, has known this for a long time. The consumer is now learning it on a broad scale, and the evidence can be found in any American kitchen. Take the case of the housewife who reels out a yard or so of expensive aluminum foil to catch the drippings from her Sunday chicken. Her husband may argue that this is waste. The wife will contend that it saves her the work of scrubbing the oven. Worth it? In a peasant economy, the wife’s time would be worth very little, the aluminum a lot. But in the U.S., the husband can afford the aluminum, and his wife sets a high value on her time.

Throwing out bottles may seem wasteful; but considering the total cost of the time and trouble it takes to return, store, ship back and resterilize a bottle, it is often cheaper to use a new one. In the case of appliances, a dishwasher might cost $150; after some years, it may cost $100 to repair it, since a highly paid repairman’s individual labor is immensely less efficient than the assembly-line labor that produces the machine. In this instance, it would clearly be wasteful not to buy a new washer. Says Sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset: “The day may come when it is more expensive to launder a shirt than to buy a new one. Which is more wasteful then—to clean the shirt or throw it away?”

Best v. Latest

Americans are buying not only time but use. Social Security, unemployment insurance and now Medicare relieve them of the once-imperative necessity of squirreling away savings for times of trouble. Installment buying has contributed to the notion of having the good things of life while you are living it, not waiting until you are too old to enjoy it. The curious result is that the modern American is in one sense much less “materialistic” than his father or his father’s father. He is more interested in the use of things to give him the good life than in the possession of perdurable objects that will reassure him. U.S. culture is based far more on achievement and productivity than on possessions. Says Buckminster Fuller: “Man used to feel secure when he owned things. Now he may feel insecure when he owns something like a house because it makes him feel encumbered.”

A dramatic illustration is the proliferation of disposable materials from cutlery to paper dresses that last for a couple of enchanted evenings (and how many times can any single dress enchant?). One of the latest manufacturers to enter the field cheerfully labels his new line Waste Basket Boutique. Some economists argue enthusiastically that disposable togs may become great waste and money savers, particularly as once-only dresses for a graduation or wedding—thus casually dismissing an older generation’s tradition of laying away wedding dresses as semisacred household lares. This may be the outer limit (there are still girls who like the idea of walking to the altar in grandma’s wedding dress), but the principle of use rather than possession is evident all over, particularly in the fact that people rent everything from skis to dance floors, at great savings of space and trouble.

There is undoubtedly too much buying for show, status and the sheer pleasure of expensive gadgetry. Perhaps the audio addict spent ridiculous amounts of money on massive monaural hi-fi rigs. But he later switched to stereo and small speakers not out of mere faddism but because they were better. Basically, the American wants what is best, not what will last forever. What upwardly mobile American really wants a car that will last 30 years, as he watches newer models go by, with power steering and brakes, pushbutton windows, et al. Or the refrigerator without automatic defrosting? The stove without a self-cleaning oven?

If it seems outrageous to tear down a handsome masonry building dating from Victorian times, one must consider the waste of energy and efficiency that would result from having people work in its non-air-conditioned rooms—or alternatively, the expense of air-conditioning them. Today, one in every four Americans changes houses each year, and a majority of them move within the same community or market area—they have simply traded in the old house for a better one. The same is true in all other fields. Less-developed countries may welcome a hand-me-down DC-3, even in the time of the jet. But the U.S. expects the best and can produce it. The price may seem like waste to some, but it can also be construed as “research” cost from which the whole world may ultimately profit.

Luxury v. Necessity

What spoils this picture of constant improvement is the sneaking suspicion that the improvement is not always real—in other words, the old bogy of planned obsolescence. Advertising, so goes the argument, not only exaggerates the improvements in many products but also relentlessly creates demands that never existed before. Obviously this is true; yet there is a limit to the process. Detroit may be able to get away with a mere face lifting on its cars for a season or two, but sooner or later there has to be genuine innovation, or else the consumer will simply not respond. Similarly, Madison Avenue may create less-than-essential needs, from deodorants to wigs, but somehow, somewhere, products must appeal to genuine human wants. Yesterday’s luxury is today’s necessity, and tastes are real even if they are acquired tastes. “The biggest waste in our society is feeding grain to animals,” says Harvard Economist Thomas Schelling. “We lose nine-tenths of the calories in the grain. As for the proteins, we could easily get all we need out of soybeans. But we like the taste of meat, and we can afford to produce it. Is this waste?”

A new car every three years may not be necessary, but if a consumer wants it and has the money, it is his choice—and his demand for a new car keeps many a Detroit factory worker busy and gives him enough money to buy a new car himself. “Buy now—the job you save may be your own” is only a slogan, but one that today’s economists recognize as sound doctrine. “So we’re making something that we only half need, but we’ve got people busy making, and people selling it,” observes University of Southern California Economist E. Bryant Phillips. Fancy packaging may not be vital, but it can be useful, and housewives like it—enough to pour nearly $11 billion into American workers’ pockets.

Many economists feel that artificially stimulated demand is preferable to a slack economy and unemployment. Not that capitalism would collapse without it, as is often charged. But if this constant stimulation were removed, it would have to be replaced by something else—public works, massive government spending, a shortened week. To some, America’s hyped-up consumption seems vaguely immoral as well as untenable in the long run. John Kenneth Galbraith has likened it to the squirrel on a treadwheel. Yet he and other economists agree that there is really nothing wrong with the process, provided that a sufficient share of a growing economy goes into social improvement.

Even taking waste in its narrowest terms, the U.S. is not so profligate as it seems. Every U.S. citizen throws away some 41 pounds of solid waste every day: garbage, tin cans, bottles, paper. It is estimated that it costs the economy $3 billion a year to do away with all this. One Rand Corp. scientist figures that it costs more to dispose of the New York Sunday Times than it does a subscriber to buy it.

But considerable ingenuity goes into the recovery and reuse of waste materials. Some industrial waste is saved and reprocessed at the plant itself; the rest comes through the scrap and salvage industry, which buys up wastes from plants, offices and homes. The copper in a skillet, for instance, may have an indefinite series of incarnations over a cycle of many years, moving from smelter to refinery to brass mill to the factory to housewife’s kitchen to junk collector to a secondary refinery where it is smelted into ingots and sold back to the factory. Overall, only an estimated 15% of all the copper ever mined has been lost.

That most conspicuous waste—paper—is less serious than it looks. Paper that starts as office stationery may be reprocessed several times to reappear as wrapping or wallboard. Some 25% of all paper now derives from this “secondary forest,” and there is so much reforestation that 60% more timber is maturing every year than is cut. A new process breaks up old cars into tiny bits and magnetically extracts the steel to produce a 97%-pure scrap, offering a hope that most of the nation’s automobile graveyards can eventually be eliminated. Fly ash is converted to make lightweight bricks, panels and construction blocks. Celotex is using blast-furnace slag to make mineral wool.

The slaughtering industry has long boasted that it used up everything but the squeal. Together with the utilization of other wastes—such as corncobs and tobacco shreddings to produce face powder and insecticides—the agriculture-waste industry is a $5.9 billion business. The squeezings from soybean oil are used for oral contraceptives. Hiram Walker says, only half in jest, that it recovers “the hangover from whisky” —fusel oil, usually blamed for hangovers, can now be largely removed from whisky and sold to paint and perfume makers. Poultry processors, confronted with smothering stockpiles of chicken feathers that would not burn, came up with a new process that breaks down the feathers into a mealy, protein-rich substance. Today, many chickens are growing fat faster on the feathers of their predecessors.

Even in the lowliest problem, the disposal of municipal and industrial wastes that pollute the air and the streams of the U.S., there has been some progress. In a process now being established in Houston and three other cities, tin cans and other ferrous-metal objects are separated magnetically from other wastes. Rags, paper, plastics and aluminum, wood and rubber are hand-picked from the conveyer belt, each for assignment to reprocessing and recovery. The remaining organic material is “cooked” and deodorized to produce fertilizer. The object in view is that each city will become a closed loop—like a space capsule—and completely reuse all the water and solids that pass through the system.

The ultimate concern is that waste will end in consuming basic resources. It is an insistent theme of conservationists, but it does not presently worry serious economists. Herbert Schiller of the University of Illinois speaks for most of his colleagues when he says flatly: “We won’t be overwhelmed by the disaster aspects of waste.” Not only is the U.S. constantly developing substitutes (aluminum for iron, oil for coal, synthetic fabrics for wool), but detection and discovery techniques have so greatly improved that the reserves known to be available are actually larger than before.

Material v. Human

The only real waste that bothers Americans is not of material but of human resources. Lack of education for gifted children, the 24.9% of draftees rejected for “functional illiteracy” or other educational deficiencies, the victims of all kinds of diseases that could be cured or alleviated —these represent human waste. On a different level, there is immeasurable wasted energy in bureaucracy, both in Government and in private business. There is waste of time, if nothing else, in the innumerable non-books published and in countless empty entertainments. Some modern puritans see shocking waste in the fees paid to chic hairdressers or in the salaries handed to television comedians, which includes paying them not to perform for somebody else. But it would take an intolerable regime of tyrannical bookkeepers to determine which activities, which pleasures, are wasteful and which are useful.

No society has ever solved the problem of waste—as archaeologists from Iraq to Denmark can testify, as they rummage through ziggurats and kitchen middens. The crucial thing is to keep alive a sense of freedom, possibility and enterprise—and in that sense the U.S. is the least-wasteful society in history. Essentially, nothing is wasted that helps fulfill a legitimate purpose. With their wild-wheeling economy, a phenomenon so extraordinary that they cannot quite believe it themselves, Americans can do anything they choose. All they have to do is make their choices.

Your browser is out of date. Please update your browser at http://update.microsoft.com

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

War on Waste: Craig Reucassel wants to change behaviour, and the law

The Chaser star’s ABC series investigates the 52 mega tonnes of waste discarded by Australians every year. He says it’s not just hearts and minds that need changing

The “It bag” of 2002 was rectangular, made of lightweight canvas – and green.

That was the year when, after a sustained marketing push from the supermarket giants, millions of Australians stop packing their shopping into plastic bags and switched to reusable green bags.

But despite this early enthusiasm, we’ve slid back and these days Australians use five billion plastic bags each year, with 85% winding up in landfill or waterways.

It’s not just this mountain of plastic bags that Australians are discarding: our waste is growing at double the rate of the population. That’s 52 megatons of coffee cups, food waste, clothes, household items and more discarded each year.

This overwhelming problem is the subject of War on Waste , a new three-part ABC documentary presented by Craig Reucassel, of The Chaser and The Checkout fame.

In the show, Reucassel deep dives – sometimes quite literally – into the world of waste. In the first episode he goes dumpster diving after midnight and also hand sorts through the rubbish of an entire street. “That was a special day,” he says, with a laugh.

There are plenty of other Chaser-esque stunts in the show including filling a Melbourne tram to the brim with the number of coffee cups discarded every 10 minutes by Australians, building a mountain of clothes in Martin Place to demonstrate how many garments go to landfill and collecting a giant ball of plastic bags to chase the Queensland minister for the environment down the street.

Are these stunts what Australians need to wake up to the problem of waste? Reucassel believes there’s a general desire to do better for those who are aware, but he hopes the stunts – and the show – will increase awareness. “I think it’s about making people aware of alternatives and [offering] answers to questions.”

Of all the different types of waste Reucassel looked into, it was the amount of food waste that shocked him most. Indeed seeing the vast piles of bananas discarded each day by Queensland banana farmers because they are too long, too short, too wide, too narrow, too bent or too straight is a particular eye-opening segment of the show. “To see so much fruit being thrown out because it doesn’t meet the cosmetic standards [of the supermarkets] was quite shocking.”

Similarly when Reucassel visited the warehouse of food relief organisation Foodbank , the enormous stocks of packaged food, well within their use-by date and discarded for flimsy reasons, is disheartening.

This was one of the more positive stories however, says Reucassel, as much of that food is repackaged and redistributed to those who need it. “All day you’ve got these cars and vans rolling up [with] all of these people donating their time, picking up food and making it into food and hampers for other people, it was really one of the positives of the experience.”

Yet while there are undoubtedly changes happening, such as Foodbank and the food waste supermarket that was recently opened in Sydney by food rescue charity OzHarvest , there is still so much that could be done.

Last year the French government banned supermarkets from discarding good quality food before its best-before date. Reucassel doesn’t believe that could happen in Australia. Although he approached a number of politicians for comment for the show, it was to no avail. “In some cases we are still waiting to get written responses from them.”

From talking to people during the making of the show, he does believe many consumers will change their behaviour but the laws need to change too. “There are obviously a lot of consumers out there who will change their behaviour because they believe in it but I think you need to have legislation that’s broader than that.

“For the people who don’t care as much, or who struggle with that change, you need to have legislation … that encourages the change. Other countries have done it. Ireland had over 90% turnaround because they put in place a piece of legislation [banning plastic bags in 2002] which totally changed people’s behaviour. So you need to have it from both sides.”

- War on Waste starts on ABC on Tuesday 16 May at 8.30pm

- Life and style

- Conscious living

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation

- Australian media

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Articles on War on Waste

Displaying all articles.

Here’s how a TV series inspired the KeepCup revolution. What’s next in the war on waste?

Danie Nilsson , CSIRO and Rachael Vorwerk , RMIT University

Time to make fast fashion a problem for its makers, not charities

Mark Liu , University of Technology Sydney

Reducing food waste can protect our health, as well as our planet’s

Liza Barbour , Monash University and Julia McCartan , Monash University

How to turn the waste crisis into a design opportunity

Tom Lee , University of Technology Sydney ; Berto Pandolfo , University of Technology Sydney ; Nick Florin , University of Technology Sydney , and Rachael Wakefield-Rann , University of Technology Sydney

Here’s a funny thing: can comedy really change our environmental behaviours?

Kim Borg , Monash University and Denise Goodwin , Monash University

For a true war on waste, the fashion industry must spend more on research

Companies should take charge of the potential toxins in common products

Dana Cordell , University of Technology Sydney ; Dena Fam , University of Technology Sydney , and Nick Florin , University of Technology Sydney

Related Topics

- Fast fashion

- Global perspectives

- Group behaviour

- Manufacturing

- Recycling crisis

- Reusable cups

- Water pollution

Top contributors

Associate Professor and Research Director, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney

Visiting Scholar: School of Architecture and School of Engineering, University of Technology Sydney

Research Director, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney

Senior Lecturer Product Design, University of Technology Sydney

Lecturer, Monash University

Senior Research Consultant, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney

Research Fellow, BehaviourWorks Australia, Monash Sustainable Development Institute, Monash University

Research Fellow at BehaviourWorks Australia, Monash Sustainable Development Institute, Monash University

Research Officer, Monash University

Behavioural Scientist, CSIRO

Associate Professor, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney

Science Communicator, ARC Centre of Excellence in Optical Microcombs for Breakthrough Science (COMBS), RMIT University

Senior Lecturer, School of Design, University of Technology Sydney

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

- Search entire site

- Search for a course

- Browse study areas

Analytics and Data Science

- Data Science and Innovation

- Postgraduate Research Courses

- Business Research Programs

- Undergraduate Business Programs

- Entrepreneurship

- MBA Programs

- Postgraduate Business Programs

Communication

- Animation Production

- Business Consulting and Technology Implementation

- Digital and Social Media

- Media Arts and Production

- Media Business

- Media Practice and Industry

- Music and Sound Design

- Social and Political Sciences

- Strategic Communication

- Writing and Publishing

- Postgraduate Communication Research Degrees

Design, Architecture and Building

- Architecture

- Built Environment

- DAB Research

- Public Policy and Governance

- Secondary Education

- Education (Learning and Leadership)

- Learning Design

- Postgraduate Education Research Degrees

- Primary Education

Engineering

- Civil and Environmental

- Computer Systems and Software

- Engineering Management

- Mechanical and Mechatronic

- Systems and Operations

- Telecommunications

- Postgraduate Engineering courses

- Undergraduate Engineering courses

- Sport and Exercise

- Palliative Care

- Public Health

- Nursing (Undergraduate)

- Nursing (Postgraduate)

- Health (Postgraduate)

- Research and Honours

- Health Services Management

- Child and Family Health

- Women's and Children's Health

Health (GEM)

- Coursework Degrees

- Clinical Psychology

- Genetic Counselling

- Good Manufacturing Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Speech Pathology

- Research Degrees

Information Technology

- Business Analysis and Information Systems

- Computer Science, Data Analytics/Mining

- Games, Graphics and Multimedia

- IT Management and Leadership

- Networking and Security

- Software Development and Programming

- Systems Design and Analysis

- Web and Cloud Computing

- Postgraduate IT courses

- Postgraduate IT online courses

- Undergraduate Information Technology courses

- International Studies

- Criminology

- International Relations

- Postgraduate International Studies Research Degrees

- Sustainability and Environment

- Practical Legal Training

- Commercial and Business Law

- Juris Doctor

- Legal Studies

- Master of Laws

- Intellectual Property

- Migration Law and Practice

- Overseas Qualified Lawyers

- Postgraduate Law Programs

- Postgraduate Law Research

- Undergraduate Law Programs

- Life Sciences

- Mathematical and Physical Sciences

- Postgraduate Science Programs

- Science Research Programs

- Undergraduate Science Programs

Transdisciplinary Innovation

- Creative Intelligence and Innovation

- Diploma in Innovation

- Transdisciplinary Learning

- Postgraduate Research Degree

Fighting the war on waste

The ABC's War on Waste is sparking national action against waste levels.

The ABC’s War on Waste has sparked major social and environmental change across Australia, triggering more than 450 initiatives by schools, hospitals, businesses, governments and community groups to slash their waste footprint.

A report by the University of Technology Sydney’s Institute for Sustainable Futures and the ABC found many people who were inspired by the ABC television program to reduce waste at home went on to drive or demand similar changes across the public, private and community sectors – greatly amplifying the impact of the series.

The report identified 452 high-impact waste-reduction initiatives triggered by War on Waste , including:

- Woolworths’ decision to remove plastic straws from its stores in Australia and New Zealand

- The Western Australian Government’s banning of single-use plastic bags

- A surge in cafes offering discounts to customers with reusable cups, preventing almost 61 million single-use cups from ending up in landfill

- Schools introducing co-mingled recycling and e-waste collections

- Hospitality businesses banning single-use plastic straws

- Hospitals and clinics introducing recycling systems and replacing single-use plastics and polystyrene with reusable products

War on Waste has triggered systems-wide changes, driving high-impact waste-reduction initiatives, models and practices across Australia. Jenni Downes Institute for Sustainable Futures

Almost half the 280 organisations in the report reduced waste in their operations, services or products based on ideas from War on Waste . Schools and universities introduced more than 200 initiatives, including e-waste collections and composting.

The snapshot of changes introduced over the six months after the broadcast of Series 2 of War on Waste in 2018 was only the “tip of the iceberg”, the report found, with the total number of waste-reduction initiatives likely to be much higher still.

"War on Waste has triggered systems-wide changes, driving high-impact waste-reduction initiatives, models and practices across Australia," said Jenni Downes, Research Lead at the Institute for Sustainable Futures and report co-author. "The universal adoption of the ‘war on waste’ slogan demonstrates a new consciousness in communities everywhere and has raised expectations and demand for change."

Teri Calder, ABC Impact Producer and report co-author, said: “ War on Waste has provided the foundations for policy change and driven widespread action to reduce Australia’s waste footprint. The biggest impact of the program has been in inspiring those with the power to make changes – in businesses, governments, education institutions and community organisations. The ABC is proud to have sparked a national conversation and inspired action to reduce our collective waste footprint.”

Craig Reucassel with students from Kiama High School doing a waste audit.

The report found that while many public education campaigns struggle to shift behaviours, viewers responded well to War on Waste’ s “motivating and uplifting” format, “solutions-focused” approach and stunts, such as an enormous footprint of plastic waste on Manly Beach in Sydney.

More than two-thirds of the 3.3 million viewers of the second seriesreported changes in waste behaviours, according to separate ABC audience data.

The War on Waste impact report is available here: https://www.abc.net.au/ourfocus/waronwaste/

UTS acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, the Boorooberongal people of the Dharug Nation, the Bidiagal people and the Gamaygal people, upon whose ancestral lands our university stands. We would also like to pay respect to the Elders both past and present, acknowledging them as the traditional custodians of knowledge for these lands.

War On Waste

Video share options, share this on, send this by.

Planet advocate and prankster Craig Reucassel takes a deep dive into Australia's waste crisis to sort the facts from the PR spin, tracking down everyday solutions to help all of us do our part in the war on waste.

- Craig Reucassel

- Join the War on Waste: Take Action

- Series 3 Credits

- Youth Waste Warriors Education Resources

- Letters and Responses Series 3

- Education Resources

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Author Guidelines

International Journal of Applied Sociology

p-ISSN: 2169-9704 e-ISSN: 2169-9739

2013; 3(2): 19-27

doi:10.5923/j.ijas.20130302.02

Consumers, Waste and the ‘Throwaway Society’ Thesis: Some Observations on the Evidence

Martin O’Brien

School of Education and Social Science, University of Central LancashirePreston PR1 2HE,UK

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The ‘throwaway society’ thesis – invariably attributed to Vance Packard (1967) – is widespread in social commentary on post-war social change.It represents, simultaneously, a sociological analysis and a moral critique of recent social development. In this article I take a brief look at the core of the ‘throwaway society’ thesis and make some comment on its modern origins before presenting and discussing data on household waste in Britain across the twentieth century.I conclude that there is nothing peculiarly post-war about dumping huge quantities of unwanted stuff and then lambasting the waste that it represents.When the historical evidence on household waste disposal is investigated, together with the historical social commentary on household wastefulness, it appears that the ‘throwaway society’ is a great deal older than Packard’s analysis has been taken to suggest.

Keywords: Consumerism, Waste, Crisis, Throwaway Society, History

Cite this paper: Martin O’Brien, Consumers, Waste and the ‘Throwaway Society’ Thesis: Some Observations on the Evidence, International Journal of Applied Sociology , Vol. 3 No. 2, 2013, pp. 19-27. doi: 10.5923/j.ijas.20130302.02.

Article Outline

1. introduction, 2. ‘the great curse of gluttony’, 3. disposable history, 4. concluding remarks.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Thanks for signing up as a global citizen. In order to create your account we need you to provide your email address. You can check out our Privacy Policy to see how we safeguard and use the information you provide us with. If your Facebook account does not have an attached e-mail address, you'll need to add that before you can sign up.

This account has been deactivated.

Please contact us at [email protected] if you would like to re-activate your account.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has caused catastrophic loss of life , widespread displacement , and a growing global food crisis .

The conflict has also extensively harmed Ukraine’s natural environment , highlighting the many ways in which war devastates biodiversity and contributes to the climate crisis.

Advocates and organizers within Ukraine have documented hundreds of environmental crimes that together, they argue, warrant the charge of ecocide by international courts. These crimes include attacks on industrial facilities that contaminate groundwater supplies and airways and the deliberate bombing of wildlife refuges and other important ecosystems.

With each additional day of warfare, Ukraine’s ability to recover its vibrant society and environment wanes, and its capacity for transitioning to an economy that excludes fossil fuels shrinks.

In recent years, a growing narrative has argued that the climate crisis is a national security threat that demands military investments. But while a deteriorating environment does, in fact, threaten people, few things fuel the crisis quite like war, which props up the global fossil fuel industry by locking in oil, gas, and coal demand, according to the Conflict and Environment Observatory (CEOBS).

War also inevitably entails destruction, resulting in widespread toxic substances, dead wildlife, and an atmosphere choked with fumes.

3 Key Facts About How War Impacts the Climate Crisis and the Environment

- Militaries consume enormous amounts of fossil fuels, which contributes directly to global warming. If the US military were a country, for example, it would have the 47th highest emissions total worldwide.

- Bombings and other methods of modern warfare directly harm wildlife and biodiversity. The collateral damage of conflict can kill up to 90% of large animals in an area.

- Pollution from war contaminates bodies of water, soil, and air, making areas unsafe for people to inhabit.

Warfare Releases Greenhouse Gas Emissions

The world’s militaries account for an estimated 6% of all greenhouse gas emissions, and many governments don’t even report data on emissions from military activities, according to the Guardian .

“Those that do often report partial figures,” Dr. Stuart Parkinson, executive director of the Scientists for Global Responsibility, told the Guardian. “So figures for military aircraft could be hidden under ‘aviation,’ military tech industry under ‘industry,’ military bases under ‘public buildings,’ etc. Indeed, it’s not just the public who are unaware, the policymakers are also unaware, and even the researchers.”

Even in peacetime, militaries consume extreme amounts of dirty energy. The US Department of Defense’s 566,000 buildings, for example, account for 40% of its fossil fuel use . These include training facilities, dormitories, manufacturing plants, and other buildings on the department’s nearly 800 bases worldwide . In countries like Switzerland and the United Kingdom, defense ministries similarly consume the most fossil fuels among government agencies. Other countries with massive militaries like China, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and Israel do not report their emissions totals , but the pattern is expected to be the same.

As countries worldwide give more money to their militaries , fossil fuel use rises both with and without conflict. And while simply maintaining a military contributes to climate change, active warfare maximizes this potential.

The US and allied forces, for example, have fired more than 337,000 bombs and missiles on other countries over the past 20 years, according to Salon. The jets carrying those weapons can burn through 4.28 gallons of gasoline per mile , with each detonation releasing additional greenhouse gas emissions, and destroying natural carbon sinks like soil, vegetation, and trees.

The US’ broader “War on Terror” has released 1.2 billion metric tons of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, according to the Watson Institute at Brown University, which has more of a warming effect on the planet than the annual emissions of 257 million cars.

If the US military were itself a country, it would have the 47th highest emissions total worldwide , greater than the countries of Denmark, Sweden, and Portugal overall.

War Causes Pollution

The environmental impact of war is far more immediate than greenhouse gases warming the atmosphere.

Pollution, in particular, is immediately felt by people stuck in conflict zones who have to contend with unsafe air, water, and soil.

People in Afghanistan, in addition to the nonstop pollution caused by bombs, have been exposed to open-air burn pits used by the army to dispose of waste. The resulting fumes from these pits have led to increases in cancer rates for both veterans and locals.

Waste management in general tends to collapse during conflict , and it's not uncommon for households to burn household trash and dump human waste in bodies of water and unlined holes.

All of the tanks and heavy vehicles driving around in conflicts kick up abrasive particles, while discarded ammunition leaks uranium into water systems, according to CEOBS .

The vacuums of power created by war can lead to illegal competition over natural resources, according to the United Nations , with examples including illegal logging, the intentional setting of forest fires to clear land, and the extraction of precious minerals using highly toxic methods.

In Colombia, rebel groups have engaged in illegal mining that filled bodies of water with mercury .

In the Vietnam War, the US army took a “scorched-earth” form of chemical warfare that destroyed landscapes with substances like “Agent Orange” that still impact people to this day .

Warfare in urban areas, like what’s happening in Ukraine right now, causes extensive damage to buildings, roads, and infrastructure, which can fill the air with debris and rubble , making it much harder to breathe.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has also featured attacks on facilities that process dangerous chemicals such as ammonia, which has threatened the safety of nearby communities.

In Yemen, Saudi Arabia has continuously bombed infrastructure like desalination plants, dams, and reservoirs , depriving communities of easy access to water.

Marine ecosystems are not shielded from this pollution. In fact, warships release extreme amounts of waste into bodies of water , degrading marine habitats and coastlines.

Even during peacetime, military testing exercises and manufacturing leads to widespread pollution. The world’s militaries occupy around 1% to 6% of all land, according to CEOBS . On these lands, they face little environmental regulation and experiment with chemicals that are banned in many places.

War Destroys Wildlife and Biodiversity

It’s never been calculated how much wildlife is lost to war — the animals killed, the plant life incinerated, the endless biodiversity erased.

But some of the approximations are mind-blowing. The number of large animals present in an area can decline by up to 90% during human conflict, and even a single year of warfare causes long-term wildlife loss, according to a study published in Nature .

Another study found that the Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique lost 95% of its biodiversity after a long civil war.

During the Vietnam War, more than 5 million acres of forest and 500,000 acres of farmland were destroyed. Lush marshlands in Iraq were reduced to 10% of their historic size after former President Saddam Hussein ordered major rivers stopped to squash an uprising. Afghanistan has lost nearly 95% of its forest cover in recent decades.

And years after a war, landmines can continue to explode and kill wildlife .

Conservationists have grown increasingly vocal in their opposition to war to prevent the demise of ecosystems that are essential to our collective well-being, whether it’s forests, grasslands, or bodies of water. Other advocates of peace note that environmental destruction becomes fuel for more war, as it deprives people and community of essential resources and ways of life.

The climate crisis itself has been labeled a threat to global security, but ending war and securing peace is the surest way to protect both ourselves and the planet.

What Can Global Citizens Do to Help?

Global Citizens can call on their governments to pursue peace and the end of conflicts worldwide by addressing root causes, while also taking steps to rapidly phase out fossil fuels and support a just transition that focuses more on people’s well-being than violence.

You can take action with us here and demand climate action now.

Global Citizen Explains

Defend the Planet

How War Impacts Climate Change and the Environment

April 6, 2022

Essay on Waste Management for Students and Teacher

500+ essay on waste management.

Essay on Waste Management -Waste management is essential in today’s society. Due to an increase in population, the generation of waste is getting doubled day by day. Moreover, the increase in waste is affecting the lives of many people.

For instance, people living in slums are very close to the waste disposal area. Therefore there are prone to various diseases. Hence, putting their lives in danger. In order to maintain a healthy life, proper hygiene and sanitation are necessary. Consequently, it is only possible with proper waste management .

The Meaning of Waste Management

Waste management is the managing of waste by disposal and recycling of it. Moreover, waste management needs proper techniques keeping in mind the environmental situations. For instance, there are various methods and techniques by which the waste is disposed of. Some of them are Landfills, Recycling , Composting, etc. Furthermore, these methods are much useful in disposing of the waste without causing any harm to the environment.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Methods for Waste Management

Recycling – Above all the most important method is the recycling of waste. This method does not need any resources. Therefore this is much useful in the management of waste . Recycling is the reusing of things that are scrapped of. Moreover, recycling is further converting waste into useful resources.

Landfills – Landfills is the most common method for waste management. The garbage gets buried in large pits in the ground and then covered by the layer of mud. As a result, the garbage gets decomposed inside the pits over the years. In conclusion, in this method elimination of the odor and area taken by the waste takes place.

Composting – Composting is the converting of organic waste into fertilizers. This method increases the fertility of the soil. As a result, it is helpful in more growth in plants. Furthermore it the useful conversion of waste management that is benefiting the environment.

Advantages of Waste Management

There are various advantages of waste management. Some of them are below:

Decrease bad odor – Waste produces a lot of bad odor which is harmful to the environment. Moreover, Bad odor is responsible for various diseases in children. As a result, it hampers their growth. So waste management eliminates all these problems in an efficient way.

Reduces pollution – Waste is the major cause of environmental degradation. For instance, the waste from industries and households pollute our rivers. Therefore waste management is essential. So that the environment may not get polluted. Furthermore, it increases the hygiene of the city so that people may get a better environment to live in.

Reduces the production of waste -Recycling of the products helps in reducing waste. Furthermore, it generates new products which are again useful. Moreover, recycling reduces the use of new products. So the companies will decrease their production rate.

It generates employment – The waste management system needs workers. These workers can do various jobs from collecting to the disposing of waste. Therefore it creates opportunities for the people that do not have any job. Furthermore, this will help them in contributing to society.

Produces Energy – Many waste products can be further used to produce energy. For instance, some products can generate heat by burning. Furthermore, some organic products are useful in fertilizers. Therefore it can increase the fertility of the soil.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

- Place order

How to Write a Perfect Essay On/About War (A Complete Guide)

War is painful. It causes mass death and the destruction of infrastructure on an unimaginable scale. Unfortunately, as humans, we have not yet been able to prevent wars and conflicts from happening. Nevertheless, we are studying them to understand them and their causes better.

In this post, we will look at how to write a war essay. The information we will share here will help anyone craft a brilliant war essay, whatever their level of education.

Let?s commence.

What Is a War Essay?

A war essay is an essay on an armed conflict involving two states or one state and an armed group. You will be asked to write a war essay at some point if you are taking a history course, diplomacy course, international relations course, war studies course, or conflict management course.

When asked to write about a war, it is important to consider several things. These include the belligerents, the location of the conflict, the leading cause or causes of the conflict, the course of the event so far, and the possible solutions to the conflict.

The sections below will help you discover everything you need to know about how to write war essays.

An essay about war can take many forms, including:

- Expository essay ? where you explore the timeline of the wars (conflicts), losses/consequences, significant battles, and notable dates.

- Argumentative essay . A war essay that debates an aspect of a certain war.

- Cause and Effect essay examines the events leading to war and its aftermath.

- Compare and contrast a war essay that pits one war or an aspect of the war against an

- Document-based question (DBQ) that analyzes the historical war documentation to answer a prompt.

- Creative writing pieces where you narrate or describe an experience of or with war.

- A persuasive essay where use ethos, pathos, and logos (rhetorical appeals) to convince your readers to adopt your points.

The Perfect Structure/Organization for a War Essay

To write a good essay about war, you must understand the war essay structure. The war essay structure is the typical 3-section essay structure. It starts with an introduction section, followed by a body section, and then a conclusion section. Find out what you need to include in each section below:

1. Introduction

In the introduction paragraph , you must introduce the reader to the war or conflict you are discussing. But before you do so, you need to hook the reader to your work. You can only do this by starting your introduction with an attention-grabbing statement . This can be a fact about the war, a quote, or a statistic.

Once you have grabbed the reader's attention, you should introduce the reader to the conflict your essay is focused on. You should do this by providing them with a brief background on the conflict.

Your thesis statement should follow the background information. This is the main argument your essay will be defending.

The introduction section of a war essay is typically one paragraph long. But it can be two paragraphs long for long war essays.

In the body section of your war essay, you need to provide information to support your thesis statement. A typical body section of a college essay will include three to four body paragraphs. Each body paragraph starts with a topic sentence and solely focuses on it. This is how your war essay should be.

Once you develop a thesis statement, you should think of the points you will use to defend it and then list them in terms of strength. The strongest of these points should be your topic sentences.

When developing the body section of your war essay, make sure your paragraphs flow nicely. This will make your essay coherent. One of the best ways to make your paragraphs flow is to use transition words, phrases, and sentences.

The body section of a war essay is typically three to four paragraphs long, but it can be much longer.

3. Conclusion