We’re independently supported by our readers and we may earn a commission when you buy through our links.

What are you looking for?

Search ideas for you, thesis nootropics review.

Sheridan Grant

Content Specialist

Sheridan is a writer from Hamilton, Ontario. She has a passion for writing about what she loves and learning new things along the way. Her topics of expertise include skincare and beauty, home decor, and DIYing.

Table of Contents

About Thesis Nootropics

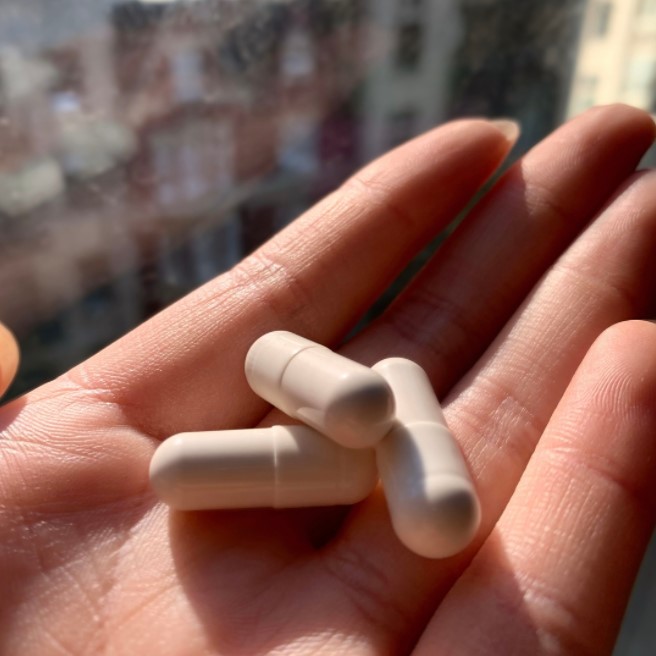

Hands up if you guzzle five coffees a day to stay awake, have tried all the supplements in the book desperate to improve your headspace, and aren’t interested in prescribed medications. Designed to increase focus , Thesis nootropics might be for you.

Thesis offers a customized blend of ingredients designed to optimize your cognitive function , with personalized details that tackle your specific needs. Nootropics boost brain performance in the same way a stimulant would, without the common negative effects.

A study published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease found that nootropics may help improve cognitive function in people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Interested in finding out more about the brand and how it works? Leaf through our Thesis Nootropics review. We’ll be your guide through the company and the process, as well as details on the treatments, highlights from customer reviews, answers to important FAQs, and more, to help you decide if it’s worth the try.

Pros and Cons

- Multiple cognitive benefits: Thesis Nootropics offers a variety of blends that cater to multiple aspects of cognitive function.

- Long-term effects: On top of short term benefits for daily life, Thesis nootropics ingredients are designed to impact the brain in the long-term.

- Personalized recommendations: Thesis Nootropics makes personalized recommendations based on your goals and unique brain chemistry.

- Potential side effects: The most common side effects to watch out for when you start taking Thesis Nootropics include heartburn, headaches, confusion, dizziness, loss of appetite, and digestive issues.

- Need to stop taking if issues arise: If you experience a headache or an upset stomach that won’t go away while taking their nootropics, Thesis recommends that you stop taking them.

What is Thesis Nootropics?

Nootropics are nutrient compounds and substances that are known to improve brain performance , such as caffeine and creatine. They help with issues that affect motivation, creativity, mood, memory, focus, and cognitive processing.

Nootropics are the ideal addition to an already healthy lifestyle that consists of exercise, proper nutrition, and enjoyable activities. Thesis nootropics are carefully formulated to target specific needs, ranging from energy to creativity. The brand focuses on safety, ensuring that all supplements adhere to FDA guidelines and go through multiple clinical trials.

How Thesis Nootropics Works

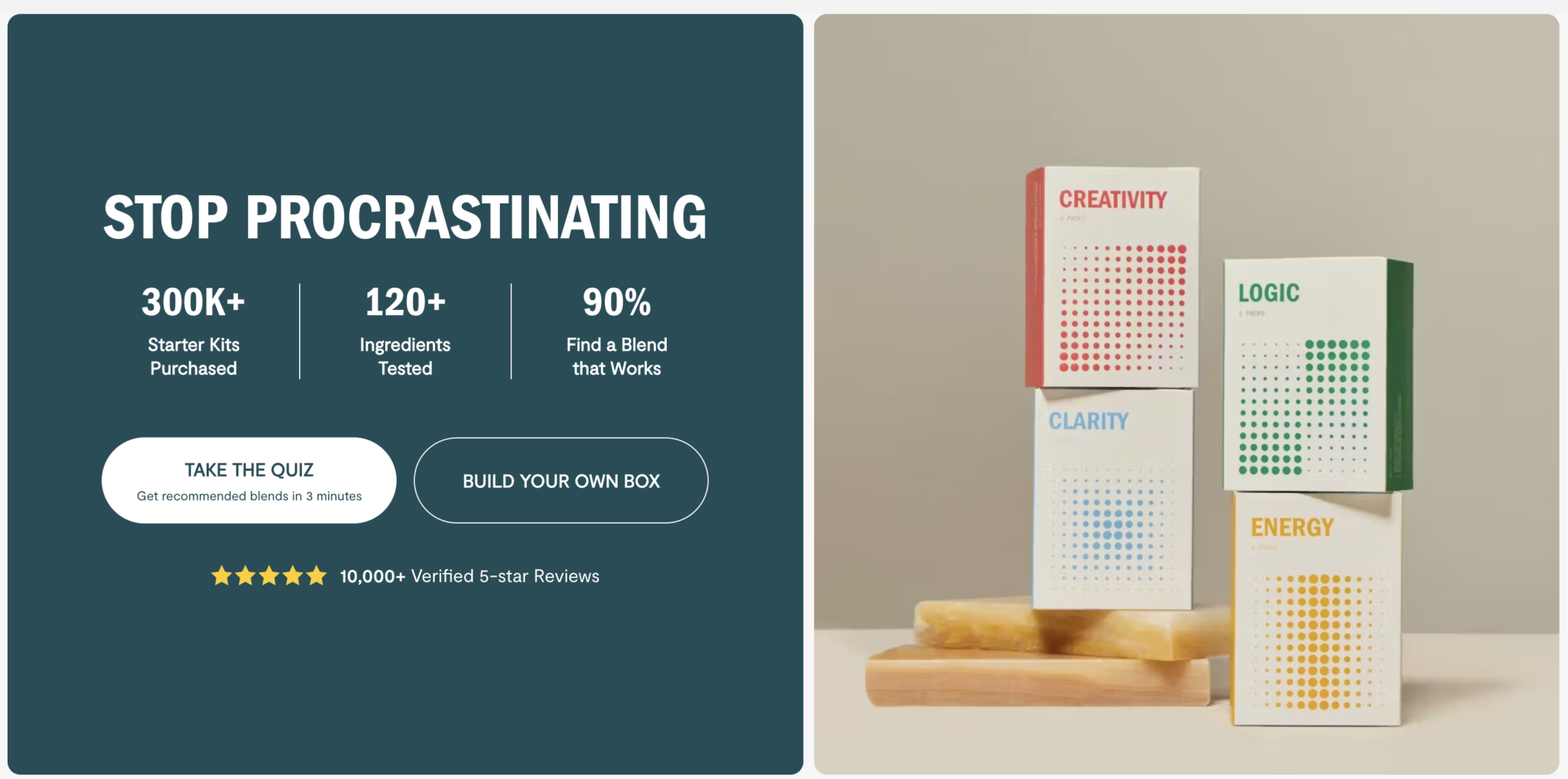

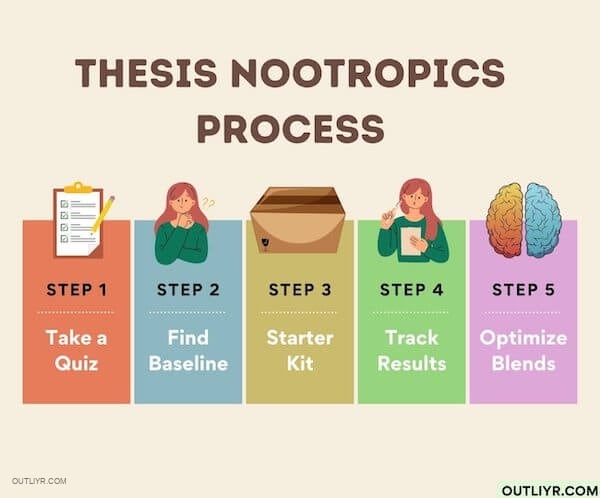

With all that being said, you may be wondering how Thesis provides users with an option that is specific to their needs. Fortunately, the process is simple and hassle free. Here’s how it works:

- Take the Thesis nootropics quiz

- Answer questions about your basic information

- Receive personalized recommendations

- Get your starter kit for $120 , or $79 monthly when you subscribe

After that, you’ll select one formula to take each week, taking one day off in between each different option. You’ll also track your results in the daily journal over the month to see how they affect your daily life.

From there, it operates as a subscription service. Users will be able to optimize their next shipment by telling the brand which formulas worked best.

If you don’t like any of the blends in your box, let the company know and they’ll switch it for something that’s a better fit for your lifestyle, genetics, and goals.

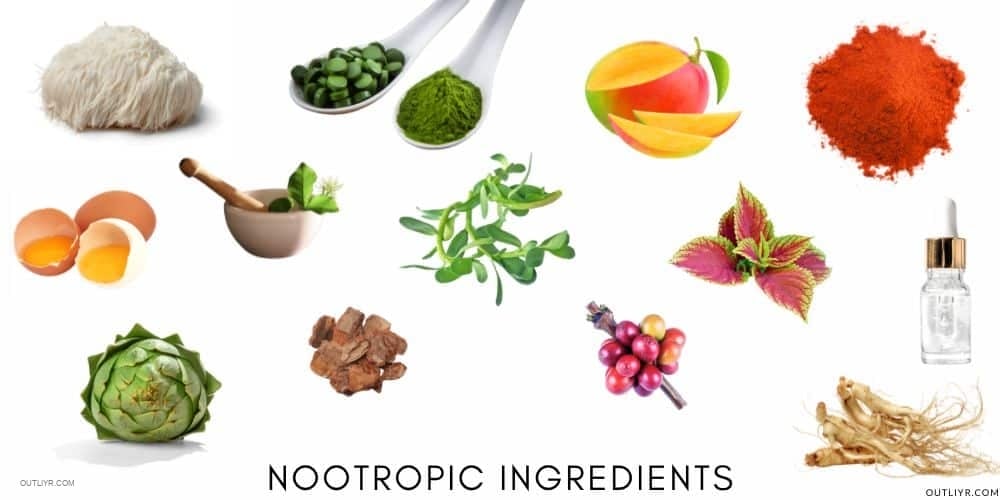

Thesis Nootropics Ingredients

Thesis Nootropics is a brand that offers personalized nootropics designed to enhance cognitive function and overall brain health. Their blends contain a variety of ingredients that are carefully chosen for their cognitive-boosting properties. Here are some of the key ingredients in Thesis Nootropics:

- Cognizin (Citicoline) : Cognizin is a type of choline that is known for its ability to enhance cognitive function, including memory and focus.

- L-Theanine : L-Theanine is an amino acid that is found in green tea, and is known for its ability to promote relaxation and reduce stress and anxiety.

- Lion’s Mane Mushroom : Lion’s Mane Mushroom is a type of medicinal mushroom that is believed to have cognitive-boosting properties, including improved memory and focus.

- Rhodiola Rosea : Rhodiola Rosea is an adaptogenic herb that is known for its ability to reduce stress and fatigue, and improve mental clarity and cognitive function.

- Ashwagandha : Ashwagandha is an adaptogenic herb that is known for its ability to reduce stress and anxiety, and improve memory and cognitive function.

- Phosphatidylserine : Phosphatidylserine is a type of phospholipid that is found in high concentrations in the brain, and is believed to support cognitive function, including memory and focus³

- Alpha-GPC : Alpha-GPC is a type of choline that is known for its ability to enhance cognitive function, including memory and focus.

- TAU (uridine): TAU is a blend of uridine, choline, and DHA, which is believed to support brain health and cognitive function.

- Artichoke extract : Artichoke extract is believed to enhance cognitive function by increasing levels of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that is important for memory and learning.

- Dynamine : Dynamine is a type of alkaloid that is believed to enhance cognitive function by increasing levels of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that is important for mood and motivation.

Overall, the ingredients in Thesis Nootropics are carefully chosen for their cognitive-boosting properties, and are designed to work together to enhance overall brain health and cognitive function.

Thesis Nootropics Health Benefits

Thesis Nootropics is a brand that offers personalized nootropics designed to enhance cognitive function and overall brain health. Their blends contain a variety of ingredients that are carefully chosen for their cognitive-boosting properties, and offer numerous health benefits. Here are some of the health benefits of Thesis Nootropics:

- Increased cognitive energy : One of the key benefits of Thesis Nootropics is increased cognitive energy, which can help improve productivity, mental alertness, and motivation, as it contains cognizin .

- Enhanced mental clarity : Another benefit of Thesis Nootropics is enhanced mental clarity,given from Lion’s Mane Mushroom which can help reduce brain fog and improve focus.

- Improved memory and learning abilities : Thesis Nootropics contains ingredients that are believed to improve memory and learning abilities, like Phosphatidylserine , which can help users retain information more effectively.

- Elevated mood : Thesis Nootropics may help elevate mood and reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression, thanks to ingredients like L-Theanine and Ashwagandha .

- Lowered stress levels : The adaptogenic herbs in Thesis Nootropics, such as Rhodiola Rosea and Ashwagandha , are known for their ability to lower stress levels and promote relaxation.

- Boosted focus : Thesis Nootropics contains ingredients like Alpha-GPC and Artichoke extract , which are believed to boost focus and concentration.

While Thesis Nootropics offers numerous health benefits, it’s important to note that the long-term effects of nootropics are not yet fully understood and more research is needed.

3 Thesis Nootropics Bestsellers

Thesis energy review.

If you’re constantly struggling to keep up with the demands of your busy life, it might be time to try a natural energy booster like Thesis Energy. This powerful nootropic blend is specifically designed to increase energy, overcome fatigue, and build mental stamina.

Thesis Energy is caffeine-free, making it a great option for those who are sensitive to caffeine or looking for a natural alternative to traditional energy drinks. The Energy formulation is designed to help improve focus and mental clarity, increase cognitive energy, and reduce fatigue. Whether you’re facing a busy day at work, recovering after a night of poor sleep, or gearing up for an intense workout, Thesis Energy can help you power through.

Each ingredient in Thesis Energy is carefully chosen for its energy-boosting properties. The specific ingredients can vary depending on your needs, but they work together to help increase energy, improve mental clarity, and reduce fatigue.

To get the most out of Thesis Energy, take it every morning on an empty stomach. You can also take it again after lunch if you need an extra boost. It’s designed to help you tackle busy, hectic days, recover from poor sleep, and power through intense workouts.

If you’re tired of relying on coffee and energy drinks to get through the day, it might be time to give Thesis Energy a try. Check availability and start boosting your energy naturally today!

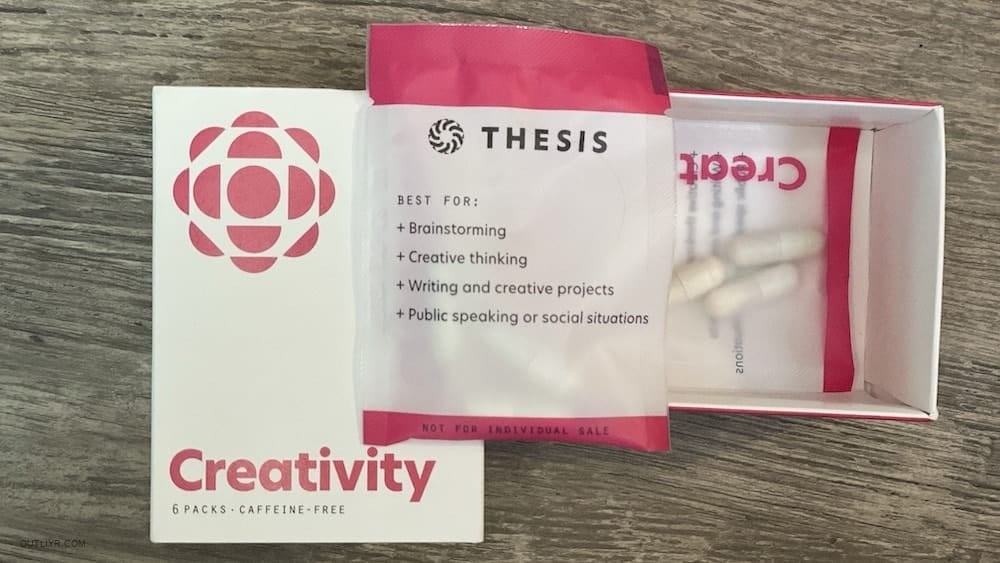

Thesis Creativity

If you’re someone who struggles with creativity or finds yourself feeling stuck in your creative endeavors, Thesis Creativity may be worth considering. This nootropic supplement is designed to help spark inspiration, enhance verbal fluency, and boost confidence in your own great ideas.

So what’s in Thesis Creativity? The ingredients may vary depending on your specific needs, but these ingredients work together to support stress management, memory function, mood regulation, and energy production.

By supporting stress management, memory function, and mood regulation, Thesis Creativity can help free up mental space for more creative thinking. Additionally, the caffeine and L-theanine combo can provide a boost of energy and focus without the jitters and crash that can come with caffeine alone.

To get the most out of Thesis Creativity, it is recommended to take it every morning on an empty stomach and again after lunch if you need an extra boost. This nootropic blend is particularly helpful for brainstorming and creative thinking, writing and creative projects, and public speaking and social situations.

As with any nootropic supplement, it’s important to note that the long-term effects of Thesis Creativity are not yet fully understood and more research is needed. It’s always a good idea to speak with a healthcare professional before adding any new supplements to your routine.

In summary, if you’re looking for a little extra help in the creativity department, Thesis Creativity may be a valuable addition to your nootropic lineup. Its unique blend of ingredients can help support mental clarity, mood regulation, and energy production, making it a valuable tool for any creative individual.

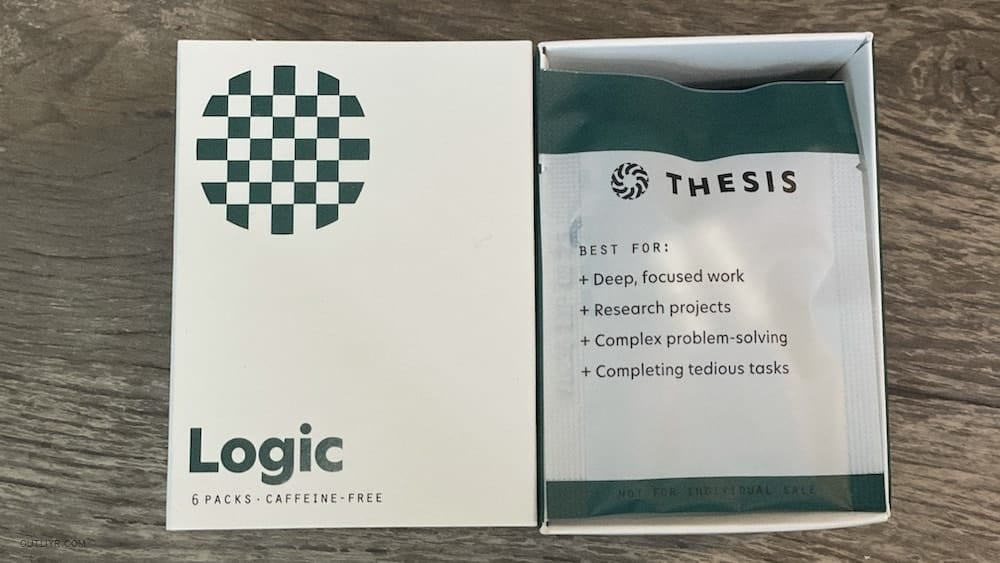

Thesis Logic

If you’ve been having trouble with your memory lately, such as forgetting what you had for lunch yesterday or struggling to recall common words, then Thesis Logic may be just what you need. This formula is designed to help enhance your processing speed, boost your memory, and deepen your thinking.

Thesis Logic is caffeine-free, making it a great option for those who are sensitive to caffeine. The formula is ideal for use during deep, focused work, complex problem-solving, research projects, and completing tedious tasks.

Taking Thesis Logic is easy – simply take it every morning on an empty stomach, and take it again after lunch if you need an extra boost. By incorporating Thesis Logic into your daily routine, you may notice improvements in your cognitive function and overall mental performance.

Who Is Thesis Nootropics For?

Thesis nootropics are designed for a number of different specific needs, including anyone who wants to focus better, have more energy, and maintain mental clarity. All in all, the products are specifically formulated to improve day to day life and target your specific needs .

Thesis Nootropics Side Effects

While Thesis nootropics are designed to enhance cognitive performance and provide a range of benefits, it’s important to be aware of the potential side effects that can occur. As with any supplement, individual reactions can vary, and some people may experience side effects while others may not.

Some of the potential side effects of Thesis nootropics include:

- Insomnia : Some nootropics contain caffeine or other stimulants that can disrupt sleep patterns and lead to difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep.

- Blurry vision : Certain nootropics, such as those containing alpha GPC, have been linked to temporary blurry vision.

- High blood pressure : Stimulant-based nootropics can increase blood pressure, which can be dangerous for people with hypertension or other heart conditions.

- Fast heart rate : Similarly, stimulants can also increase heart rate, leading to palpitations or a rapid pulse.

- Circulation problem s: Certain nootropics, such as vinpocetine, can affect blood flow and circulation, leading to issues like dizziness, nausea, or headaches.

- Addiction : Some nootropics, such as those containing racetams, have been associated with the potential for addiction or dependence if used long-term.

It’s important to remember that not all nootropics will produce these side effects, and the severity of any reactions will depend on individual factors such as dosage, duration of use, and underlying health conditions. However, it’s always wise to discuss any potential risks with a healthcare professional before starting any new supplement regimen.

Additionally, it’s important to follow dosage instructions carefully and not to exceed recommended amounts, as this can increase the risk of side effects. By being mindful of potential risks and using nootropics responsibly, users can reap the benefits of these supplements without experiencing adverse effects.

Thesis Nootropics Reviews: What Do Customers Think?

At this point in our Thesis nootropics review, it’s time to turn to what customers are saying. So, we sourced testimonials from the brand’s website, Reddit, and ZenMasterWellness. And spoiler alert, the Thesis nootropics reviews we came across have nothing but good things to say.

On takethesis.com , the brand earns 4.4/5 stars out of 7,956 reviews. One patron describes their particular blend as the perfect alternative to prescription meds :

“ I have been off stimulants for months now and these formulas are far superior. My husband and daughter both noticed the change and said I have been more productive, focused, less anxious, and more “thinking outside the box”. I have tried for years to get off stims and nothing would work .”

On Reddit, many reviewers share similar sentiments about how effective the products are. One buyer shares that they tried tons of different nootropics on the market, and Thesis stands out amongst the crowd .

On ZenMasterWellness, one reviewer states that their blend provided the exact results they were looking for :

“ They offer notable improvements to how well I’m able to focus, stay on task, and grind when it’s time to grind. In practice, this usually looks like a clearer mind and an improved ability to just… chill. With the Clarity and Creativity blends, in particular, I just feel leveled out .”

Backed by clinical trials and real customer experiences, Thesis stands out in the world of nootropics and supplements. The personalized selections prove effective, while the quality ingredients live up to expectations.

Is Thesis Nootropics Legit?

If you’re wondering if this brand offers products that are too good to be true, this Thesis nootropics review is here to say that it is the real deal .

The brand is backed by numerous clinical trials, which highlight how 86% of customers reported improvements in a wide range of cognitive challenges, while 89% noticed an improvement in their ability to reduce stress and maintain energy.

Is Thesis Nootropics Worth It?

Thesis is an appealing choice in the world of nootropics because it provides a completely customized selection based on your needs and goals. Plus, the ingredients are potent and ensure the best effects—and you only end up paying for the benefits you actually need.

With that in mind, this Thesis nootropics review deems the brand worth the try.

Alternatives

Here are some alternatives to Thesis Nootropics that you might find interesting:

- Mind Lab Pro – This nootropic supplement is designed to improve cognitive function and mental performance. It contains 11 ingredients that work together to enhance memory, focus, and overall brain health.

- Thorne Supplements : If you’re looking for high-quality, science-based supplements, Thorne is a great choice. Their products are designed with the latest research in mind and are rigorously tested for quality and purity. Some of their popular offerings include multivitamins, protein powders, and omega-3 supplements.

- WeAreFeel Supplements : WeAreFeel is a supplement brand that offers a variety of products designed to support different aspects of your health. Their supplements are vegan-friendly and free from artificial colors, flavors, and preservatives. Some of their popular offerings include multivitamins, probiotics, and omega-3 supplements.

- Neuro Gum : If you’re looking for a quick and easy way to boost your focus and energy levels, Neuro Gum is a great option. This gum is infused with caffeine and other natural ingredients that can help improve mental clarity and alertness. Plus, it’s sugar-free and comes in a variety of delicious flavors.

- Neuriva Plus : Neuriva Plus is a brain supplement that’s designed to improve memory, focus, and cognitive performance. It contains a blend of natural ingredients, including coffee fruit extract and phosphatidylserine, that have been shown to support brain health. If you’re looking for a natural way to boost your cognitive function, Neuriva Plus is worth considering.

Thesis Nootropics Promotions & Discounts

There aren’t currently any Thesis promos or discounts available. That being said, if you subscribe for recurring shipments of your recommended products, you’ll save $40 monthly .

Where to Buy Thesis Nootropics

At the time of this Thesis nootropics review, the products are exclusively available on the brand’s website, takethesis.com .

Is Thesis Nootropics vegan?

Thesis nootropics are made with only vegan ingredients . That being said, while the brand has taken precautions to protect against cross contamination, the products are not certified vegan.

Is Thesis Nootropics gluten-free?

On top of being vegan, Thesis products are made without gluten, eggs, or nuts . Again, while the brand strives to protect users against cross contamination, the products are not certified gluten free.

What is Thesis Nootropics’ Shipping Policy?

If you’re anxiously awaiting your order from this Thesis nootropics review, you’ll be happy to hear that the company offers speedy shipping, sending orders out within 1 business day. After that, packages should arrive within only 1-3 business days . Costs are calculated at checkout.

At this time, Thesis is not able to offer international shipping. This Thesis nootropics review recommends following the brand on social media and signing up for the newsletter to stay up to date with shipping policies.

What is Thesis Nootropics’ Return Policy?

If you find that your Thesis formula isn’t working out, the company requests that you contact them to make changes and adjustments to ensure you are able to receive the proper help.

If you would still like to make a return, follow these simple steps for a refund:

- Submit your refund request

- Ship the items back within 30 days of the original delivery

- Send an email with your tracking number to the brand

- Return any remaining product in their original packaging to:

Thesis Returns 902 Broadway

6th Floor New York, NY

Once your return has been received, a refund will be processed and email confirmation will be sent. It’s also important to note that the brand can only refund one month’s supply per customer and return shipping is the customer’s responsibility.

How to Contact Thesis Nootropics

We hope you enjoyed this Thesis nootropics review! If you have any further questions about the brand or its products, you can contact them using the following methods:

- Call 1 (646) 647-3599

- Email [email protected]

902 Broadway Floor 6 New York, NY 10010

If you’re looking for other ways to boost your productivity via supplements, check out these other brands we’ve reviewed:

Thorne Supplements Review

WeAreFeel Supplements Review

Neuro Gum Review

Neuriva Plus Review

Our team is dedicated to finding and telling you more about the web’s best products. If you purchase through our links, we may receive a commission. Our editorial team is independent.

Ask the community or leave a comment

Customer reviews, leave a review, ask the community or leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This field is required

This field is required Please use a valid email

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

You may also be interested in

Online Pharmacies

Hims Review

Keeps Review

Keeps vs Hims

BlueChew Review

Rugiet Review

Hims ED Review

Online Therapy

BetterHelp Review

BetterHelp vs Talkspace

General Health Tests

Best DNA Health Test

Best Microbiome Test

Viome Review

Best At-Home Herpes Test

STDcheck Review

Hair and Hair Loss

Best Hair Loss Treatment for Men

Best Laser Cap for Hair Loss

Kiierr Laser Cap Review

Relationships & Sexual Health

Best STD Dating Websites

Best Herpes Dating Websites

Best Erectile Dysfunction Treatment

Best Delay Spray

Best Prostate Massager

BlueChew Free Trial

Nutrition Guide

Found Weight Loss Review

BlueChew Promo Code

Best CBD for Arthritis

Best Incontinence Underwear for Women

Best Incontinence Underwear for Men

Fitness and Weight

Best Amino Acid Supplements

Best Muscle Building Stack

Vital Reds Review

Total Restore Review

Best NMN Supplement

Best NAC Supplement

Best NAD Supplement

Best Berberine Supplement

Mood and Energy

Best Nootropics

Best Saffron Supplement

Sexual Health

Best Testosterone Booster

Best Male Enhancement Pills

Best Volume Pills

Skeletal System

Muscular System

Cardiovascular System

Digestive System

Nervous System

Respiratory System

Urinary System

Integumentary System

Thesis Nootropics Review

Thesis has a range of targeted nootropics you can combine to optimize your results. our team will help you decide which ones are right for you..

Daniel is a senior editor and writer at Innerbody Research. After receiving his bachelor’s degree in writing, he attended post-graduate studies at George Mason University and pursued a career in nutritional science.

Dr. Segar is a cardiology fellow at the Texas Heart Institute and a member of Innerbody Research's Medical Review Board.

In this Review

Nootropics in general offer the potential to improve cognitive abilities and regulate mood without the need for a prescription. And while more research is necessary, current data suggests that they consist of ingredients that are generally safe and effective for healthy adults. 35 However, Thesis isn’t the only provider of high-quality nootropics, nor do they offer especially low prices. In this review, we'll compare and contrast Thesis’ six formulas and see how they stack up against a growing field of competitors.

Our Findings

Despite the somewhat high price, we recommend Thesis to anyone looking for a nootropic subscription that can be tailored to their specific needs. The formulas from Thesis provide tangible benefits with minimal ingredients, and each formula is available with or without caffeine. Thesis also offers stellar customer service and delivers their product in individually packed doses you can take just about anywhere.

- You can feel most results within an hour

- Products are third-party-tested for purity

- All options available without stimulants

- Outstanding phone support

- Subscriptions include complimentary wellness coaching

- Free shipping on all orders

- Use code INNERBODY for 10% off your first order

- Somewhat more expensive than competitors

- Up to four large pills per dose

GREAT PICKS FROM THESIS

Special Offer: Take 10% OFF with code INNERBODY

Why you should trust us

Over the past two decades, Innerbody Research has helped tens of millions of readers make more informed decisions about staying healthy and living healthier lifestyles. As nootropics have become more important players in the supplements landscape, we’ve taken a serious look at the key players to see which ones are worthwhile.

Thesis exists in a class of nootropics that combines multiple nootropic ingredients to achieve specific goals. We’ve spent hundreds of hours researching and testing various nootropics, including both individual ingredients and combinations like Thesis offers. In researching Thesis and their competitors, our team has read more than 100 clinical studies examining the efficacy and safety of nootropic ingredients, and we’ve combined all of that knowledge with our experiences to create this review.

If you're curious about our team's experience using Thesis nootropics and wondering how the products will arrive at your door, we made this handy, 5-minute video summarizing those details:

Additionally, like all health-related content on this website, this review was thoroughly vetted by one or more members of our Medical Review Board for accuracy.

How we evaluated Thesis

To evaluate Thesis, we examined the extensive research available on each ingredient the company uses and compared them to a growing marketplace of nootropics, many of which our testing team has tried over the past few years. Specifically, we assessed how effectively Thesis' formulas work, as well as their safety, cost, and the convenience of acquiring and taking them.

Ultimately, we found Thesis to be one of the more reliable companies in terms of product quality and customer care, even if they are among the more expensive nootropic brands. For any nootropic, you’re looking to create a noticeable effect in brain performance, and altering anything to do with that sensitive chemistry likely warrants a fair investment. The bargain bin is not typically where you want to shop for mind-enhancing substances.

We’ll get into a more direct comparison between Thesis and their competitors a little later, and you’ll see that the balance between their price and overall value is quite reasonable. For now, let’s look at each criterion in more detail.

Effectiveness

Nootropic companies have a plethora of ingredients at their fingertips when they formulate their products. Some companies take a modern approach, focusing on the latest research into established Western medicines. Others look to the past, where ancient Chinese and Ayurvedic practices employed various botanicals to achieve cognitive effects. The best companies combine these approaches, using potentially beneficial ingredients that science supports.

Thesis takes this combined approach, employing just under three dozen ingredients from amino acids to ancient herbs across their six products. The company scores highly in effectiveness thanks to the ingredients they choose and the doses they offer for each, making it likely that you can notice their combined effects.

Individual results will vary due to everything from sleep patterns to diet, but most people should find benefits in at least one of Thesis' six formulas. Caffeinated formulas generally have more pronounced effects than stimulant-free versions, but the value of Thesis offering every formula with or without stimulants cannot be overstated.

One minor knock against Thesis is that, unlike some of their competitors, Thesis does not have a nootropic blend designed for improved sleep. Better sleep supports cognition and mood, so some companies offer formulas designed specifically for sleep promotion with ingredients like melatonin. That said, some of Thesis’ formulas contain lion’s mane or Zembrin (a branded form of Sceletium tortuosum that’s been shown to reduce anxiety and promote sleep). 2 3 And the amount of Zembrin used in Thesis’ Creativity and Confidence blends is the exact same amount used in these successful studies — 25mg.

Good nootropics are, unfortunately, a bit expensive. You can find less expensive options than Thesis, but their $79 monthly rate is right in the middle of what the market demands. You could also argue that the ingredient quality, customization options, and overall efficacy Thesis offers make it a superior value to many less expensive alternatives. Still, the price remains a sticking point for some.

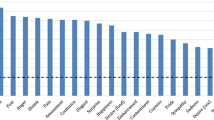

Let's compare the monthly and per-dose costs with some of Thesis' closest competition. The prices below reflect subscription savings where available.

Three of the seven competitors included in the chart above are more expensive than Thesis, and another three are no more than $15 less expensive, revealing their generally average cost. Focus Factor — consistently our top budget pick among nootropics — costs much less than others in the field and includes many ingredients with associated clinical research. The downside is that increasing the number of ingredients (even when they seem to work) increases the odds of an adverse reaction.

TruBrain is the only company that truly compares to Thesis from a quality and variety standpoint. Other companies offer only one or two formulas, whereas Thesis and TruBrain each offer several more targeted products. TruBrain allows you to spend just $69 on your first jar when you subscribe — $10 less than Thesis — but that price shoots up to $119 every month after that, making Thesis the superior value.

When we consider the safety of any supplement, we look at available research into individual ingredients and compare those dosages with what the supplement offers. Whenever possible, we also test the product ourselves to observe its effects on us. Additionally, we look for safety standards in manufacturing that can provide added peace of mind, like third-party testing and compliance with the FDA’s Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP).

Thesis manufactures their products in GMP-compliant facilities and has third-party testing performed to assess the purity of each ingredient and formula. And the clinical research involving the lion's share of their ingredients reveals minimal risk profiles with few to no adverse effects reported. That said, ashwagandha isn’t safe for pregnant or breastfeeding individuals, and it can stimulate thyroid activity, so anyone with thyroid concerns (hyper- or hypothyroidism) or on medication to regulate thyroid function should be careful. 36 37

Thesis also limits their formulas to a handful of ingredients, which reduces the likelihood that any one of them would cause an adverse reaction. This is pretty typical of nootropics in Thesis’ class, but less expensive nootropics might try to convince you of their value by stuffing a single blend with several dozen components. That might increase the chances you feel some positive effect, but the side effect risk goes up by the same token.

Convenience

Our convenience rating considers various aspects of a user's experience. It usually starts with the quality of a product's website design and whether or not its pages are easy to navigate. We also consider the presence of subscription systems that make reordering easier and money-back guarantees that protect your investment. A company's customer service is another vital aspect of convenience, especially if you need questions answered. The quality of an FAQ section, the availability of representatives via chat or phone call, and the responsiveness to email inquiries all play a part here.

Our convenience rating is also informed by the steps required to actually take the product. Nootropics often consist of large capsules, and doses can contain anywhere from 1-7 capsules, which is awful for anyone with difficulty taking pills. Smaller capsules, fewer capsules per dose, and simple dosing schedules are ideal. Thesis’ capsule count varies per formula, ranging from 2-4 mid-size capsules you can take 30 minutes before you might want or need their effects.

To summarize some important aspects of nootropic company convenience, let's look at which companies have large capsule counts, good money-back guarantees, and subscription systems.

Thesis also provides a service that few other companies offer: free consultations with in-house nootropic coaches. These experts can help you figure out the best time to take specific Thesis formulas and guide your experience so you can tell whether or not they're working for you. Follow-up consultations are also free as long as you subscribe to the product.

What are nootropics?

Nootropic is a term most people use to refer to any non-prescription supplement that can boost brainpower. 4 The technical definition is a little more nuanced — encompassing prescription medications like Ritalin and Adderall — but the supplement industry has largely co-opted it to categorize the new class of non-prescription products. The word loosely translates from its Greek origins to mean mind-changing, and the majority of ingredients in a given nootropic seek to alter the brain’s cognitive abilities, as well as its governance of mood and energy.

Most nootropic supplements contain botanical ingredients, vitamins, minerals, and amino acids that boast at least some clinical research connecting them with improvements in any of the following:

Compared to their prescription cousins, nootropic supplements aren't particularly strong. Still, limited clinical research indicates a tangible benefit to taking them.

What is Thesis?

Thesis is a supplement company with a focus on nootropics. Their founders each had experiences growing up with what would today be considered learning disabilities, and they credit nootropics for changing their lives. They make six distinct nootropic formulas, each with a specific ingredient profile.

Thesis differentiates themselves from their competitors in several critical ways:

- They offer a starter kit containing a personalized combination of four blends.

- You have the option to remove caffeine by request from any formula.

- They provide some of the best phone support we've ever experienced.

- Their targeted formulas conform to changing needs.

By providing you with a mix of formulas, Thesis gives you the ability to enhance the aspects of your cognitive and emotional life that need it the most on any given day. Maybe you know you have low energy levels on Mondays and Wednesdays, so you can take the Energy formula on those days. Maybe you want to devote your weekends to artistic pursuits. You can use the Creativity blend for that. Or you might find that one of their six blends works well for you in any situation. In that case, you can adjust your order to receive only that formula.

Thesis' customer service — particularly over the phone — is outstanding. While many customers might find chat support more convenient, our testers rarely waited more than a minute to speak to someone, and Thesis employs phone operators who are extraordinarily knowledgeable about the product and nootropics in general. Their email support is fine, and their chat support often redirects to an email inquiry. But that phone support is some of the best our testing team has experienced.

Is Thesis safe?

Most of the ingredients that Thesis uses in their nootropics exhibit minimal side effects in clinical research, so there’s a good chance that Thesis' various formulas will be safe for most people. But Thesis has nearly three dozen ingredients in their catalog, and not all of them will be safe for all users, including those who are pregnant or breastfeeding. Of course, the most important thing you can do is talk to your doctor before taking Thesis.

The most common side effects to watch out for when you start taking Thesis nootropics include:

- Loss of appetite

- Digestive issues

Thesis advises discontinuing their nootropics if you experience persistent headaches or an upset stomach.

Some Thesis products may present contraindications with certain prescription medicines. For example, ashwagandha has been shown to normalize thyroid hormone levels in people with hypothyroidism. 5 This has led some to believe that it could conversely cause thyrotoxicity in people with hyperthyroidism, though it’s worth noting that the study in question employed double the highest ashwagandha dose you’ll find in Thesis nootropics — the study used 600mg, and the ashwagandha dose in Thesis’ Creativity is 300mg.

Still, this should make abundantly clear the case for speaking with your doctor prior to taking Thesis. This is especially true considering the lack of research into the specific ingredient combinations you’ll find in Thesis products. There is also very little research looking into the risks of combining nootropic supplements with prescription stimulants such as Ritalin, Adderall, or Vyvanse.

Some side effects, such as jitteriness, can be attributed to the caffeine in Thesis formulas. The fact that you can elect to remove caffeine from any formula expands the company’s reach to anyone with caffeine sensitivities and those who really don’t want to give up their morning cup of coffee. If you want caffeine in your Thesis formula, we recommend trying it without having had any coffee first, so you can see how it affects you.

Insider Tip: If you’re not sure whether to get your formula with or without caffeine, we recommend getting it with caffeine. Thesis isolates the included caffeine in a single capsule separate from other ingredients. Caffeinated formulas cost the same as uncaffeinated ones, and you can always elect not to take the caffeine capsule (the smallest capsule in any formula, containing a white powder).

What are the ingredients in Thesis?

Thesis uses an impressive set of ingredients, many of which have been part of respectable clinical research. Not all of the effects they hope these ingredients provide have been proven with sufficient statistical significance or over multiple studies in different populations, but what we do know strongly suggests efficacy.

Here's a look at several Thesis ingredients that have encouraging research behind them:

Several studies on mice show that dihydrohonokiol-B (DHH-B) has potent anxiolytic effects. 6 That means it may be able to help combat anxiety. However, we can’t say this for sure since there haven’t been any studies conducted on humans yet, so any potential benefits are speculative at this time. 25 Converting the successful dose used in mice (1mg) to the equivalent human amount (4.86 mg) is about half the amount used in Thesis’ Confidence (10mg). 6

In numerous studies, ashwagandha has been shown to reduce stress and anxiety. 32 Thesis uses a branded KSM-66 ashwagandha, which has a high standardized count of withanolides — the component of ashwagandha responsible for its positive effects. 33 This ensures both efficacy and consistency from doses that align with those used in successful studies.

While every formula is different, you'll notice that each contains caffeine and L-theanine. The nootropic properties of caffeine are well established. 19 L-theanine — a non-stimulant derived from green tea — has been shown to smooth out the jittery effects of caffeine. You can easily have caffeine removed from any Thesis formula for no extra cost, which is unique in the nootropic market. The L-theanine will remain, as it has its own set of cognitive benefits in addition to its ability to tame caffeine. 20

Saffron offers multiple benefits, including increased levels of dopamine and glutamate, that are dose-dependent. Human studies have also shown positive effects on depression symptoms. Thesis’ Confidence uses 28mg, which is 2mg less than what was used in many of the studies on saffron’s antidepressant effects. However, one study did find success with as little as 15mg. 7

A review of more than 120 scientific articles looking into the cognitive effects of phosphatidylserine concluded that it “safely slows, halts, or reverses biochemical alterations and structural deterioration in nerve cells.” The study goes on to say that it “supports human cognitive functions, including the formation of short-term memory, the consolidation of long-term memory, the ability to create new memories, the ability to retrieve memories, the ability to learn and recall information, the ability to focus attention and concentrate, the ability to reason and solve problems, language skills, and the ability to communicate.” 34

Derived from a South African plant, Zembrin appears to provide cognitive and anti-anxiety effects as demonstrated in clinical studies on human participants that used the same 25mg dose found in Thesis Creativity and Confidence. 8

Synapsa is a patented form of Bacopa extract, a traditional Ayurvedic memory enhancer. Studies on humans resulted in statistically significant improvements in cognitive tests. The study used 150mg twice daily (300mg total), which is only 20mg less than the 320mg used in Thesis’ Logic. 9

7,8 DHF is a small molecular TrkB agonist that can easily cross the blood-brain barrier. It can increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that improves neuroplasticity, learning, and memory. BDNF deficiencies are connected to numerous cognitive ailments as well. However, no human studies have been conducted. 26 In mice, 7,8 DHF appears to enhance spatial memory. When converting the effective dose for mice to humans, Thesis’ Clarity offers roughly 6mg more (about 24mg compared to Thesis’ 30mg). 27

Choline is a precursor to acetylcholine, a powerful neurotransmitter in the peripheral, autonomic, and enteric nervous systems. 10 One study on older adult human participants found that taking 187-399mg per day of choline reduced the risk of low cognitive functioning by nearly 50% compared to an intake under 187mg per day. 28 The CDP choline content in Thesis’ Energy is 300mg.

A 2010 clinical study on 485 older adult (over 55 years old) subjects found that 900mg per day of DHA improved memory and learning in those with age-related cognitive decline. 11 And another study in healthy adults 18-90 years old found that 580mg per day helped improve memory. 29 Unfortunately, the amounts used in many studies to improve cognitive function are quite a bit more than the 200mg (which is DHA and L-lysine combined) found in Thesis’ Logic.

Like choline, Alpha-GPC acts as an effective acetylcholine precursor. Studies also show that supplementation with Alpha-GPC can stave off exercise-induced reductions in choline levels. The effective amount used in the mentioned study is 200mg, which is less than half of what you’ll find in Thesis’ Clarity (500mg). 12

In addition to being an effective treatment for neuropathic pain, agmatine appears to have potent effects as an antidepressant. A five-year safety case report study concluded that there are no long-term side effect risks. Thesis’ Creativity only contains 250mg, which is well below the amount tolerated by study participants (2.67g per day). 13

Research into epicatechin indicates that it can enhance cerebral blood flow, delivering more oxygen to the brain to ensure it operates at its highest efficiency. The most effective dose for cognitive benefits appears to be over 50mg per day, and Thesis’ Clarity contains 278mg. 14

Lion's mane has been shown to increase nerve growth factor and promote neurite outgrowth of specific neural cells. It's a safe and reliable neurotrophic, but studies have debunked claims of neuroprotective properties. 15 A very small study of only 41 participants found that 1.8g of Lion’s mane may reduce stress and improve cognitive performance. 30 Thesis’ Clarity contains 500mg of Lion’s mane.

Hyperphenylalaninemia, a severe deficiency in phenylalanine, results in reduced dopamine, serotonin, and noradrenaline levels in the brain. 16 It can also alter cerebral myelin and protein synthesis. Supplementing with phenylalanine may provide neuroprotective benefits.

In a 2020 study, phenylalanine was a large component in a mix of seven amino acids that appeared to improve cognitive, psychological, and social functioning in middle-aged and older adults. Effective doses ranged from 0.85g to 1.7g of phenylalanine. A serving of Thesis’ Motivation contains 500mg, a bit under half of the average amount. 31

Examining the six formulas

Thesis has six nootropic formulas in their lineup (even though you can only choose up to four of them per box). Several other nootropic companies like TruBrain and BrainMD boast targeted lineups, as well, but Thesis is the Goldilocks of the bunch. Where BrainMD’s hyper-specific formulas rely on perhaps too few ingredients to make them worthwhile, many of TruBrain’s complex blends lack real specificity. With Thesis, you get targeted effects from numerous ingredients in moderately complex and reasonably priced combinations.

Each Thesis formula has a blend of ingredients that addresses specific needs. Their names give you a pretty big clue as to what the company intends each to do, but a closer look at their ingredients will help you understand how they achieve this.

Their formulas are:

Interestingly, the company thinks of its formulas as working well in pairs. You don't have to utilize them as such, but it's helpful to know how they view their most effective combinations. The following list details their purported combined benefits.

Enhances focus, eliminates brain fog, and lets thoughts flow naturally

Gets you going, keeps you going, and never crashes

Sparks new ideas, inspires extroversion, and revels in openness

You'll usually only take one formula at a time, but these pairs may act synergistically for specific personality types or cognitive needs.

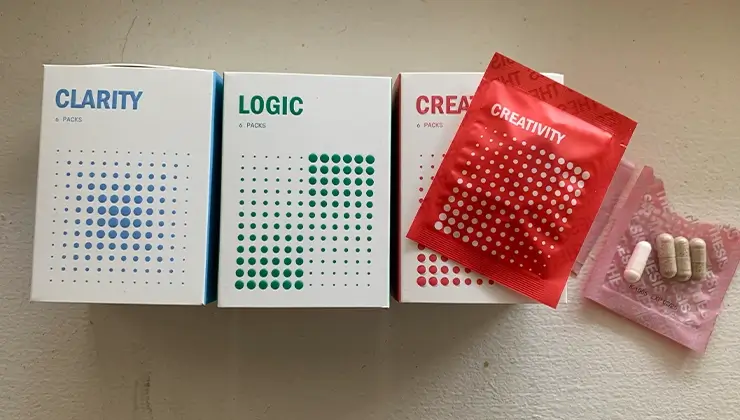

Note that your first shipment of Thesis will contain six individually packed doses for four of these six formulas. Thesis chooses these formulas for you based on the results of an intake questionnaire, but you can make adjustments to that shipment on the customer dashboard before the shipment leaves their warehouse.

Let's take a closer look at each formula as they would appear with caffeine included.

Thesis Clarity

Thesis Clarity relies on 7,8 DHF (dihydroxyflavone), Alpha GPC (glycerylphosphorylcholine), epicatechin, and lion's mane to increase blood flow to the brain and stimulate the production of acetylcholine, a powerful neurotransmitter associated with learning, memory, and attention. It's particularly adept at cutting through brain fog.

Here's a look at Clarity's full ingredients list:

- Alpha GPC: 500mg

- Lion's Mane Mushroom: 500mg

- Camellia sinensis tea leaf: 278mg

- Dihydroxyflavone: 30mg

- Caffeine: 100mg

- L-Theanine: 200mg

One dose of Clarity consists of four capsules for the caffeinated formula and three capsules for the stimulant-free formula.

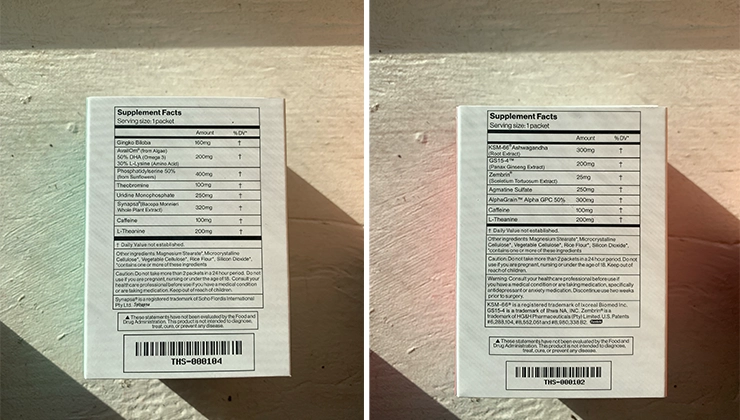

Thesis Logic

Thesis Logic contains triacetyluridine (TAU), which caters to the health of the entire central nervous system. It also uses phosphatidylserine to help facilitate communication between and protection of brain cells. 17

This is Logic’s complete ingredients list:

- Ginkgo Biloba: 160mg

- Theobromine: 100mg

- Phosphatidylserine: 400mg

- High DHA Algae: 200mg

- Triacetyluridine: 30mg

- Bacopa Monnieri: 320mg

One dose of Logic consists of four capsules for the caffeinated formula and three capsules for the stimulant-free formula.

Thesis Energy

Thesis Energy uses cysteine and tyrosine alongside caffeine to deliver a steady energy supply. It also includes TeaCrine, a branded form of theacrine, which partners with caffeine to affect adenosine signaling and prevent fatigue.

Here’s a full list of Energy’s ingredients:

- Citicoline: 300mg

- Mango leaf: 300mg

- Theacrine: 100mg

- N-Acetyl cysteine: 500mg

- Indian trumpet tree: 100mg

- N-Acetyl L-tyrosine: 300mg

One dose of Energy consists of three capsules for the caffeinated formula and two capsules for the stimulant-free formula.

Thesis Motivation

Blood flow and cellular function are at the core of Thesis Motivation . It employs artichoke extract, forskolin, and B12 to achieve these goals, with a healthy dose of phenylalanine for added focus and motivation.

Here's Motivation's full ingredients list:

- L-Phenylalanine: 500mg

- Methylliberine: 100mg

- Vitamin B12: 1000mcg

- Forskolin: 250mg

- Artichoke: 450mg

One dose of Motivation consists of three capsules for the caffeinated formula and two capsules for the stimulant-free formula.

Thesis Creativity

Thesis Creativity aims to realign you with your inspiration by removing barriers caused by stress, anxiety, and depression. It contains ingredients with powerful anxiolytic properties and 5-HT reuptake inhibition.

Here's a look at Creativity’s ingredients list:

- Alpha GPC: 150mg

- Agmatine sulfate: 250mg

- Panax ginseng: 200mg

- Ashwagandha root: 300mg

- Sceletium tortuosum : 25mg

One dose of Creativity consists of three capsules for the caffeinated formula and two capsules for the stimulant-free formula.

Thesis Confidence

Confidence is designed to work hand-in-hand with Creativity, using saffron and DHH-B from magnolia bark to increase dopamine levels and decrease anxiety. One fascinating ingredient in this formula is sage extract, which one 2021 study showed can help with various memory tasks, including name and face recognition. 18 It’s worth noting, though, that this study employed a 600mg dose compared to Thesis’ 333mg dose.

Here is Confidence's complete ingredients list:

- Saffron: 28mg

- Magnesium bisglycinate: 500mg

- Sage: 333mg

- Magnolia Bark: 10mg

- Ashwagandha leaf & root: 120mg

One dose of Confidence consists of three capsules for the caffeinated formula and two capsules for the stimulant-free formula.

Our Thesis testing results

Our testing team has tried every Thesis formula (with and without caffeine) to determine their short- and long-term efficacy, at least at an anecdotal level. Here’s a quick summary of our experiences:

Clarity provided our testers with a combined sense of focus and mental ease, though we mostly found that it worked best from its second day forward. The very first dose is mildly effective, but it served us better as a loading dose. We had no crash from either caffeinated or uncaffeinated formulas.

Our testers found that Logic provided a similar experience as Clarity, increasing focus and mental acuity, but the caffeinated formula caused a crash in two of our testers. By excluding the caffeine, that crash can be avoided, though that comes at the expense of some efficacy.

We were very curious about how this formula would perform without the caffeine. Our testers had a noticeable increase in energy without jitteriness about one hour after taking Energy. The caffeinated version caused the worst crash of all the formulas, but we were pleased to find that the formula without caffeine still provided noticeable energy increases without a crash.

Our testers are generally a pretty motivated bunch, so we might not have been the best group to evaluate this particular formula. The testers who felt an uptick in a sense of motivation described it more like a feeling of being able to follow through on tasks with less distraction and completion anxiety.

Creativity, like Clarity, seemed to work better for our testers on its second and third days than on its first. Testers generally described a sensation similar to Motivation but without the feeling of being “on rails,” as one tester put it. It seems to allow for more curiosity and exploration, though not necessarily as much follow-through.

This is Thesis’ newest formula, so fewer of our testers have tried it. Among those who have, one tester with a mild case of social anxiety described feeling a bit more relaxed among groups of people. Testers preferred this formula without caffeine.

Thesis pricing, shipping, and returns

Thesis keeps their price structure decidedly simple. This is refreshing, considering the range of nootropics they offer. You don't have to worry about one formula costing you more than another. However, Thesis doesn't make a non-subscription approach economically feasible.

Every Thesis shipment — including the starter pack — consists of four small boxes, each containing six doses of a single formula. That’s 24 doses/month.

Here's how it works:

- Any one-time purchase of a one-month supply, including the starter kit, costs $119.

- When you subscribe, that monthly cost is only $79.

- You can take an extra 10% off your first order with the coupon code INNERBODY

Subscriptions require an account with Thesis, which gives you access to a well-designed customer dashboard. This is where you can easily make formula adjustments, alter your shipping schedule, or cancel your subscription entirely.

Shipping from Thesis is free in the U.S., and the company offers a 30-day money-back guarantee. In our testing experience, we attempted a return on a second shipment into the subscription. While it isn’t the company’s policy to do so, they refunded our money and let us keep the product. This is similar to some other “Keep it” guarantees we’ve seen from competitors, and we appreciated it.

Getting started with Thesis Nootropics

Thesis' website is easy to navigate, but it is inconvenient that you must complete the signup questionnaire before accessing formula-specific pages. There are ways around this — like direct searching or just knowing the formula URLs — but we think reviewing formulas should be a little easier when you first get to the site. And you won’t be able to place an order for anything until you complete the questionnaire.

The user interface for managing your subscription is exceptionally intuitive. You can quickly adjust your formula combinations, specifying whether or not you want specific formulas to contain caffeine.

Setting up a subscription with Thesis is a straightforward process. Here are the basic steps:

- Take the Thesis quiz . This will create a starter kit specific to your results. (You can also build a box from scratch if you know which formulas you want to try.)

- Order your starter kit. We recommend going with the kit Thesis creates after your quiz, but if you change your mind, you can use the customer portal after placing your order to make any changes to the formula combination before it ships.

- Set up a coaching consultation. This is an optional step, but we recommend it and encourage you to have your first consultation before your kit arrives.

- Take your nootropics as needed. Most people can experience some of Thesis nootropics' benefits within a few hours of ingestion. Some ingredients and formulas may take a few days to produce results.

- Refine your order. As you near the end of your first month, you can head over to the Thesis website and customize your next order to include the formula or formulas you like most.

- Set up follow-up consultations as needed. These will help you refine your future orders and maximize your results.

When you subscribe to the starter kit, you will continue receiving that kit every month until you customize your order. Thesis divides their boxes into four six-dose supplies, and you can mix and match those supplies to suit your needs. For example, you could boost energy on the weekdays and creativity on the weekends by getting a one-month supply with 18 servings of Energy in three packages and six servings of Creativity in a single package.

Personalized insights and coaching

When you take the quiz on the Thesis website, you'll get personalized insights comparing your results to other quiz-takers and a data set developed from nearly 500 scientific studies. The parameters in your results cover don’t completely line up with their formulas, but they include:

These results inform the system to make recommendations for your starter kit. After you order, you can set up a consultation with a Thesis coach. These consultations are free, and you can have as many follow-up sessions as you like. Other companies have apps or online resources like blogs or courses to help you on your nootropic journey, but Thesis’ personalized coaching offers a unique approach and execution.

Consultation calls last around 15 minutes, though some of our testers had their sessions go longer as their coaches' schedules allowed. We received best practices information about taking nootropics that covered dose timing, formula application, and more. Some of our testers also received diet and exercise advice that coincided with their formulas.

Alternatives to Thesis

There are generally two tiers of products in the nootropics landscape. The lower tier consists of products that cost between $20 and $40. Many of these nootropics contain proprietary blends that obscure the exact quantities of ingredients, presumably so companies can use more of the least expensive components. Some companies in this tier disclose their ingredient quantities but may not source them from the highest quality suppliers or perform third-party testing of any kind.

Top brands in this tier include:

- Onnit Alpha BRAIN

- Moon Juice Brain Dust

- Focus Factor

The second tier — where you'll find Thesis — consists of more expensive nootropics that spell their contents out clearly, use high-quality ingredients, and often perform third-party testing to ensure safety and potency. Top brands in this tier include:

- Qualia Mind

Hunter Focus

We have a comprehensive breakdown of our top nootropics , but here's a concise breakdown of Thesis' most comparable competition.

TruBrain offers one of the widest varieties of nootropics of any company — one of the few catalogs that rivals the variety Thesis offers. They also have some novel and beneficial delivery methods for their nootropic ingredients. Those include energy bars and liquid shots that are outstanding for anyone with difficulty swallowing pills.

TruBrain offers their nootropics in a targeted fashion, not unlike what you get from Thesis. They formerly offered their targeted blends in shot form only, but now you can get any of these targeted blends in capsule or liquid shot form. The shots come in small 1oz pouches that make them easy to take anywhere.

TruBrain's targeted blends include:

This is TruBrain's original blend. It contains seven nootropics, including Noopept, a branded form of N-phenylacetyl-L-prolylglycine ethyl ester. This blend is caffeine-free.

The Strong blend is identical to the Medium formulation in contents and doses, but it also contains 100mg of caffeine.

The Extra Strong formula builds on the Strong blend by adding 150mg of adrafinil (2-(diphenylmethyl)sulfinyl-N-hydroxyacetamide). 21 This wakefulness-promoting substance may also help with weight loss and athletic performance.

TruBrain's Sleep formula contains just four nootropic ingredients: GABA, melatonin, 5-HTP, and a blend that TruBrain calls "functional oils."

Mellow is identical to the medium strength formula, but it adds the functional oil combination used in Sleep.

This formula contains Lion's mane, a mushroom that may promote neural growth , though human studies are necessary to determine if this is true. 22 Its other nootropic ingredients are rhodiola, guayusa, and rosehips.

A 30-day supply of TruBrain nootropic shots costs $89. That's $10 more than the subscription cost for a one-month supply of Thesis. Some of their shots contain caffeine, and others don't. If it already contains caffeine, there's no way to alter a TruBrain formula to be stimulant-free.

The first month of TruBrain capsules costs a bit less, coming in at $69. After your first month, however, the price goes up to $119. That makes Thesis the better value, but if you want the best possible nootropics for sleep support, it might be worth the extra money to check out TruBrain.

Qualia Mind is a brand under the Neurohacker Collective, a company that offers several products to address things like sleep quality, skin health, and vision. They have three nootropics available:

- Qualia Mind Caffeine-Free

- Qualia Mind Focus

Their original blend is comprehensive, consisting of nearly 30 ingredients in high doses. That means it's liable to provide you with noticeable effects. It also means you might not know which of those effects are coming from which ingredients, and some of the less beneficial components in your body may also have side effects you'd rather avoid.

The caffeine-free version is identical to the original formula but leaves the caffeine out. Qualia Focus is a more streamlined offering with only seven nootropic ingredients, including caffeine, L-theanine, and L-ornithine. 23

Initial shipments from Qualia Mind are significantly discounted, but after the first month, the price makes theirs one of the most expensive nootropics we've tested. For example, the first month of a subscription to Qualia Mind costs just $39. After that, it costs $139/month. And a one-time purchase is $159.

One inconvenient aspect of Qualia Mind is that a single dose consists of seven capsules, which can get tiresome even for people who don't have trouble swallowing pills. On the bright side, Qualia's 100-day money-back guarantee allows you to try it for a little over three months to determine if you can handle that kind of daily dosing.

Hunter Focus is one of three supplements in the Hunter stack alongside the company's Test and Burn supplements. The stack is intended for male use — Test is a testosterone supplement — but Focus and Burn are suitable for men and women.

Like Qualia Mind, Focus has a long list of ingredients in generous doses. In fact, one serving of Hunter Focus is like taking all six of Thesis' formulas at once. That said, the serving itself is difficult to swallow, as it consists of six large pills.

Another knock on Hunter is that they don't offer a subscription system. That means you can't get an extra discount, and you must remember to reorder when you're running low (theoretically, a nootropic like this should boost your memory). There's also no money-back guarantee to speak of, only a return policy with a relatively short window that only applies to unopened products.

One bottle of Hunter Focus costs $90, and shipping is $8.95 unless you buy more than one bottle at a time. The company will throw a fourth in for free if you buy three bottles at once. That's the only way to get any savings through Hunter.

Individual nootropic components

Many companies offer combinations of nootropic ingredients to perform specific brain-related tasks or even provide globally positive cognitive benefits. However, the scientific research behind most of these ingredients almost always includes just one rather than a combination. Some people prefer to try one at a time to minimize the potential for side effects and determine if one particular ingredient works for them. A few companies offer single-ingredient nootropic supplements for this specific purpose.

Our favorite company dealing in individual nootropic components is Nootropics Depot. They offer a wide variety of single-ingredient supplements and a few targeted blends. The prices are generally fair, with an average range running from $16-$70. A 30-day money-back guarantee covers every purchase, and you get free shipping on orders over $50.

Nootropics FAQ

.css-1ygl3x{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;width:100%;outline:2px solid transparent;outline-offset:2px;transition-property:var(--chakra-transition-property-common);transition-duration:var(--chakra-transition-duration-normal);font-size:1rem;-webkit-padding-start:var(--chakra-space-4);padding-inline-start:var(--chakra-space-4);-webkit-padding-end:var(--chakra-space-4);padding-inline-end:var(--chakra-space-4);padding-top:var(--chakra-space-2);padding-bottom:var(--chakra-space-2);}.css-1ygl3x:focus,.css-1ygl3x[data-focus]{box-shadow:var(--chakra-shadows-outline);}.css-1ygl3x:hover,.css-1ygl3x[data-hover]{background:var(--chakra-colors-blackalpha-50);}.css-1ygl3x[disabled],.css-1ygl3x[aria-disabled=true],.css-1ygl3x[data-disabled]{opacity:0.4;cursor:not-allowed;} .css-1eziwv{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;text-align:left;} how do nootropics affect the brain .css-1eok0x8{width:1em;height:1em;display:inline-block;line-height:1em;-webkit-flex-shrink:0;-ms-flex-negative:0;flex-shrink:0;color:#e22c3e;opacity:1;-webkit-transition:-webkit-transform 0.2s;transition:transform 0.2s;transform-origin:center;font-size:1.25em;vertical-align:middle;}.

Specific nootropics affect different parts of the brain in their own ways. Some — like caffeine — reduce fatigue by blocking adenosine receptors, while others act to protect neural connections that are already present while possibly contributing to new neural growth. 24 Some also mitigate depression and anxiety, which frees up the brain to perform at its best.

Are nootropics safe?

The safety of a nootropic depends on the specific ingredients involved. Many are perfectly safe in the doses commonly employed by nootropic companies, but some can cause reactions like increased heart rate, gastrointestinal discomfort, headache, and even tremors. The smartest thing to do is to talk to your doctor before introducing any new supplement to your regimen.

Do nootropics really work?

Many nootropic supplements are noticeably effective — caffeine is a great example. Efficacy varies depending on the specific component or combination. Fortunately, a lot of companies offer money-back guarantees, so you can try their products to see if they work for you without much financial risk.

Will nootropics make me smarter?

Nootropics won't necessarily make you smarter, but many can increase your alertness, improve short-term recall, and promote neural growth and protection. That creates a great environment for learning if you apply yourself while using nootropics, and many ingredients can help you with the motivation it takes to do so.

How do you pronounce nootropics?

The 'noo' in nootropics comes from the Greek nous , which philosophers use to mean mind or intelligence. The 'tropic' in nootropic comes from the Greek tropikos , which relates to turning or changing. So, nootropic roughly translates to mind-changing. You pronounce the 'noo' like 'new' and the 'tropic' with a long O sound, like 'toe pick.'

Innerbody uses only high-quality sources, including peer-reviewed studies, to support the facts within our articles. Read our editorial process to learn more about how we fact-check and keep our content accurate, reliable, and trustworthy.

Mayo Clinic. (2022). Memory lapses: Normal aging or something more? Mayo Clinic Press.

Reay, J., Wetherell, M. A., Morton, E., Lillis, J., & Badmaev, V. (2020). Sceletium tortuosum (Zembrin®) ameliorates experimentally induced anxiety in healthy volunteers . Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 35 (6), 1-7.

Chiu, S., Gericke, N., Farina-Woodbury, M., Badmaev, V., Raheb, H., Terpstra, K., Antongiorgi, J., Bureau, Y., Cernovsky, Z., Hou, J., Sanchez, V., Williams, M., Copen, J., Husni, M., & Goble, L. (2014). Proof-of-Concept Randomized Controlled Study of Cognition Effects of the Proprietary Extract Sceletium tortuosum (Zembrin) Targeting Phosphodiesterase-4 in Cognitively Healthy Subjects: Implications for Alzheimer’s Dementia . Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine , 2014, 682014.

Suliman, N. A., Mat Taib, C. N., Mohd Moklas, M. A., Adenan, M. I., Hidayat Baharuldin, M. T., & Basir, R. (2016). Establishing Natural Nootropics: Recent Molecular Enhancement Influenced by Natural Nootropic . Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine: ECAM, 2016.

Sharma, A. K., Basu, I., & Singh, S. (2018). Efficacy and Safety of Ashwagandha Root Extract in Subclinical Hypothyroid Patients: A Double-Blind, Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial . Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 24 (3), 243–248.

Kuribara, H., Kishi, E., & Maruyama, Y. (2010). Does Dihydrohonokiol, a Potent Anxiolytic Compound, Result in the Development of Benzodiazepine-like Side Effects? Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 52 (8), 1017-1022.

Siddiqui, M. J., M. Saleh, M. S., B. Binti Basharuddin, S. N., Binti Zamri, S. H., Najib, M., Ibrahim, C., Noor, M., Binti Mazha, H. N., Hassan, N. M., & Khatib, A. (2018). Saffron (Crocus sativus L.): As an Antidepressant . Journal of Pharmacy & Bioallied Sciences, 10 (4), 173-180.

Terburg, D., Syal, S., Rosenberger, L. A., Heany, S., Phillips, N., Gericke, N., Stein, D. J., & Van Honk, J. (2013). Acute Effects of Sceletium tortuosum (Zembrin), a Dual 5-HT Reuptake and PDE4 Inhibitor, in the Human Amygdala and its Connection to the Hypothalamus . Neuropsychopharmacology, 38 (13), 2708-2716.

Kumar, N., Abichandani, L. G., Thawani, V., Gharpure, K. J., Naidu, U. R., & Ramana, G. V. (2015). Efficacy of Standardized Extract of Bacopa monnieri (Bacognize®) on Cognitive Functions of Medical Students: A Six-Week, Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial . Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine: eCAM, 2016 .

Colucci, L., Bosco, M., Ziello, A. R., Rea, R., Amenta, F., & Fasanaro, A. M. (2012). Effectiveness of nootropic drugs with cholinergic activity in treatment of cognitive deficit: A review . Journal of Experimental Pharmacology, 4 , 163-172.

Yurko-Mauro, K., McCarthy, D., Rom, D., Nelson, E. B., Ryan, A. S., Blackwell, A., Salem, N., Jr, Stedman, M., & MIDAS Investigators (2010). Beneficial effects of docosahexaenoic acid on cognition in age-related cognitive decline . Alzheimer's & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association, 6 (6), 456–464.

Parker, A. G., Byars, A., Purpura, M., & Jäger, R. (2015). The effects of alpha-glycerylphosphorylcholine, caffeine or placebo on markers of mood, cognitive function, power, speed, and agility . Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 12 (Suppl 1), P41.

Gilad, G. M., & Gilad, V. H. (2014). Long-term (5 years), high daily dosage of dietary agmatine--evidence of safety: a case report . Journal of Medicinal Food, 17 (11), 1256–1259.

Haskell-Ramsay, C. F., Schmitt, J., & Actis-Goretta, L. (2018). The Impact of Epicatechin on Human Cognition: The Role of Cerebral Blood Flow . Nutrients, 10 (8).

Lai, P. L., Naidu, M., Sabaratnam, V., Wong, K. H., David, R. P., Kuppusamy, U. R., Abdullah, N., & Malek, S. N. (2013). Neurotrophic properties of the Lion's mane medicinal mushroom, Hericium erinaceus (Higher Basidiomycetes) from Malaysia . International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms, 15 (6), 539–554.

Ashe, K., Kelso, W., Farrand, S., Panetta, J., Fazio, T., De Jong, G., & Walterfang, M. (2019). Psychiatric and Cognitive Aspects of Phenylketonuria: The Limitations of Diet and Promise of New Treatments . Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10 , 434708.

Dobolyi, A., Juhász, G., Kovács, Z., & Kardos, J. (2011). Uridine function in the central nervous system . Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry, 11 (8), 1058–1067.

Wightman, E. L., Jackson, P. A., Spittlehouse, B., Heffernan, T., Guillemet, D., & Kennedy, D. O. (2021). The Acute and Chronic Cognitive Effects of a Sage Extract: A Randomized, Placebo Controlled Study in Healthy Humans . Nutrients, 13 (1), 218.

Cappelletti, S., Daria, P., Sani, G., & Aromatario, M. (2015). Caffeine: Cognitive and Physical Performance Enhancer or Psychoactive Drug? Current Neuropharmacology, 13 (1), 71-88.

Hidese, S., Ogawa, S., Ota, M., Ishida, I., Yasukawa, Z., Ozeki, M., & Kunugi, H. (2019). Effects of L-Theanine Administration on Stress-Related Symptoms and Cognitive Functions in Healthy Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial . Nutrients, 11 (10), 2362.

Lowe, D.W., Dobson, E., Jewett, A.G., Whisler, E.E. (2021). Adrafinil: Psychostimulant and Purported Nootropic? The American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal, 17 (1).

Sabaratnam, V., Kah-Hui, W., Naidu, M., & David, P. R. (2013). Neuronal Health – Can Culinary and Medicinal Mushrooms Help? Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine, 3 (1), 62-68.

Miyake, M., Kirisako, T., Kokubo, T., Miura, Y., Morishita, K., Okamura, H., & Tsuda, A. (2014). Randomised controlled trial of the effects of L-ornithine on stress markers and sleep quality in healthy workers . Nutrition Journal, 13 , 53.

P., E., Rábano, A., Cafini, F., & Ávila, J. (2019). Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is abundant in neurologically healthy subjects and drops sharply in patients with Alzheimer’s disease . Nature Medicine, 25 (4), 554-560.

Rauf, A., Olatunde, A., Imran, M., Alhumaydhi, F. A., Aljohani, A. S., Khan, S. A., Uddin, M. S., Mitra, S., Emran, T. B., Khayrullin, M., Rebezov, M., Kamal, M. A., & Shariati, M. A. (2021). Honokiol: A review of its pharmacological potential and therapeutic insights . Phytomedicine, 90 , 153647.

Yang, S., & Zhu, G. (2022). 7,8-Dihydroxyflavone and Neuropsychiatric Disorders: A Translational Perspective from the Mechanism to Drug Development . Current Neuropharmacology, 20 (8), 1479-1497.

Lazari, A., Tisca, C., Tachrount, M., B., A., Miller, K. L., & Lerch, J. P. (2023). 7,8-dihydroxyflavone enhances long-term spatial memory and alters brain volume in wildtype mice . Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 17 , 1134594.

Liu, L., Qiao, S., Zhuang, L., Xu, S., Chen, L., Lai, Q., & Wang, W. (2021). Choline Intake Correlates with Cognitive Performance among Elder Adults in the United States . Behavioural Neurology, 2021 .

Li, J., R. Pora, B. L., Dong, K., & Hasjim, J. (2021). Health benefits of docosahexaenoic acid and its bioavailability: A review . Food Science & Nutrition, 9 (9), 5229-5243.

Docherty, S., Doughty, F. L., & Smith, E. F. (2023). The Acute and Chronic Effects of Lion’s Mane Mushroom Supplementation on Cognitive Function, Stress and Mood in Young Adults: A Double-Blind, Parallel Groups, Pilot Study . Nutrients, 15 (22).

Suzuki, H., Yamashiro, D., Ogawa, S., Kobayashi, M., Cho, D., Iizuka, A., Takada, M., Isokawa, M., Nagao, K., & Fujiwara, Y. (2020). Intake of Seven Essential Amino Acids Improves Cognitive Function and Psychological and Social Function in Middle-Aged and Older Adults: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial . Frontiers in Nutrition, 7 , 586166.

Chandrasekhar, K., Kapoor, J., & Anishetty, S. (2012). A Prospective, Randomized Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Safety and Efficacy of a High-Concentration Full-Spectrum Extract of Ashwagandha Root in Reducing Stress and Anxiety in Adults . Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 34 (3), 255-262.

Mirjalili, M. H., Moyano, E., Bonfill, M., Cusido, R. M., & Palazón, J. (2009). Steroidal Lactones from Withania somnifera, an Ancient Plant for Novel Medicine . Molecules, 14 (7), 2373-2393.

Glade, M. J., & Smith, K. (2015). Phosphatidylserine and the human brain . Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.), 31 (6), 781–786.

Malík, M., & Tlustoš, P. (2022). Nootropics as Cognitive Enhancers: Types, Dosage and Side Effects of Smart Drugs . Nutrients, 14 (16).

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. (2023). Ashwagandha . NIH.

Kamal, H. I., Patel, K., Brdak, A., Heffernan, J., & Ahmad, N. (2022). Ashwagandha as a Unique Cause of Thyrotoxicosis Presenting With Supraventricular Tachycardia . Cureus, 14 (3).

No spam! Your privacy is important to us.

Copyright © Innerbody Research 1997 - 2024. All Rights Reserved.

Innerbody Research does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. You must consult your own medical professional.

I Tried 4 Thesis Nootropic Blends (My 2024 Review)

Alpha Brain vs. Focus Factor (I Tried Both For 30 Days): Who Wins In 2024?

Focus Factor vs. Prevagen (I Tried Both): Who Wins In 2024?

Mind Lab Pro vs. Prevagen (I Tried Both): Who Wins In 2024?

Alpha Brain vs. Prevagen (I Tried Both): Who Wins In 2024?

I Took Prevagen For 30 Days (My 2024 Review)

NooCube vs. Prevagen (I Tried Both): Who Wins In 2024?

Best Nootropics For Athletic Performance (2024)

Qualia Mind vs. Alpha Brain (I Tried Both): Who Wins In 2024?

Qualia Mind vs. NooCube (I Tried Both): Who Wins In 2024?

Mind Lab Pro vs. Qualia Mind (I Tried Both): Who Wins In 2024?

Thesis stands out in the wellness industry with its personalized nootropic supplements, designed to cater to the individual’s specific cognitive needs. It has been pushed by health and wellness celebrities, causing a wave of popularity.

Do Thesis nootropics live up to the hype?

- Variety Of Blends: Various nootropic blends based on individual brain chemistry, maximizing effectiveness for each user.

- Strong Advocacy and Support: Gained endorsements from notable wellness advocates and public figures, like Andrew Huberman, enhancing credibility.

- Limited Clinical Research: While the company plans clinical trials, the current scientific backing may be limited.

- Price: The ongoing cost of customized nootropics may be higher than standard off-the-shelf supplements or medications.

- Dependence on Self-Reporting: The effectiveness of blends relies partly on user feedback, which may not always be accurate or consistent.