- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Art of Persuasion Hasn’t Changed in 2,000 Years

- Carmine Gallo

What Aristotle can teach us about making an argument.

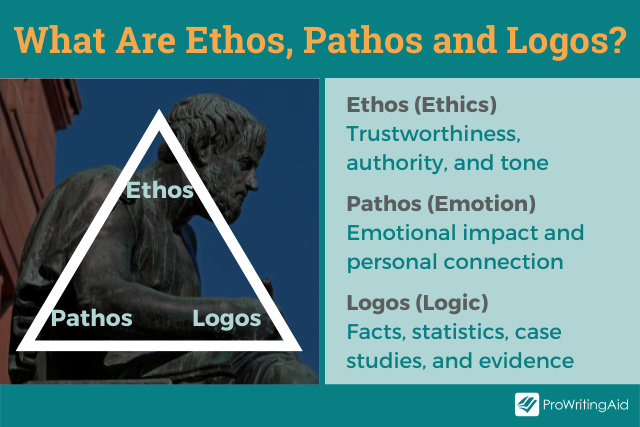

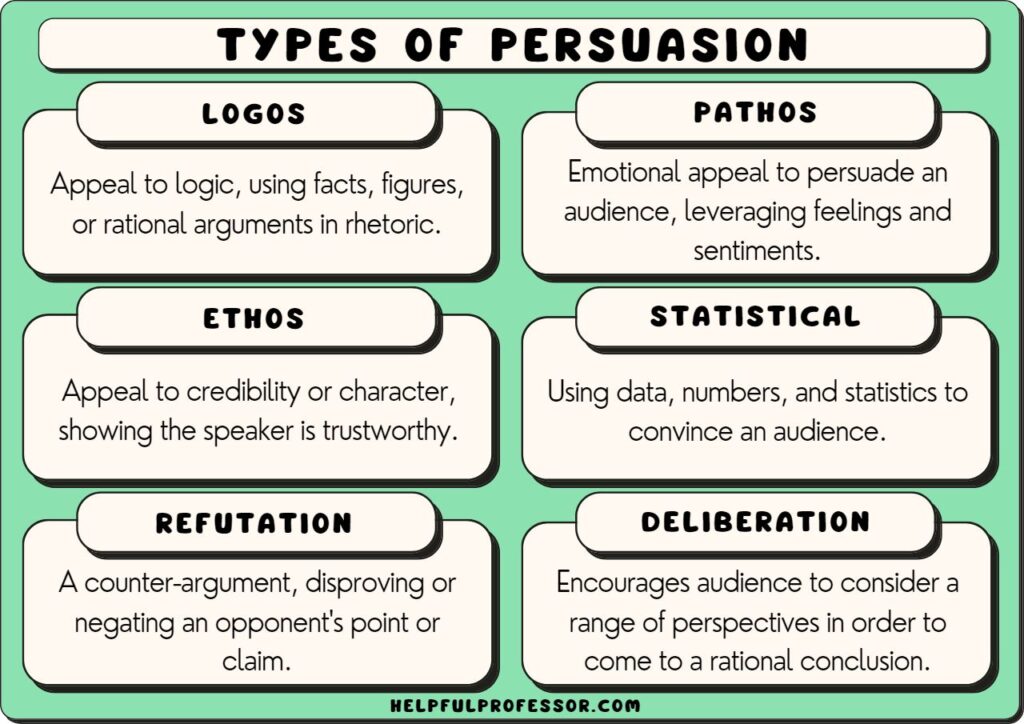

More than 2,000 years ago Aristotle outlined a formula on how to become a master of persuasion in his work Rhetoric . To successfully sell your next idea, try using these five rhetorical devices that he identified in your next speech or presentation: The first is egos or “character.” In order for your audience to trust you, start your talk by establishing your credibility. Then, make a logical appeal to reason, or “logos.” Use data, evidence, and facts to support your pitch. The third device, and perhaps the most important, is “pathos,” or emotion. People are moved to action by how a speaker makes them feel. Aristotle believed the best way to transfer emotion from one person to another is through storytelling. The more personal your content is the more your audience will feel connected to you and your idea.

Ideas are the currency of the twenty-first century. The ability to persuade, to change hearts and minds, is perhaps the single greatest skill that will give you a competitive edge in the knowledge economy — an age where ideas matter more than ever.

- Carmine Gallo is a Harvard University instructor, keynote speaker, and author of 10 books translated into 40 languages. Gallo is the author of The Bezos Blueprint: Communication Secrets of the World’s Greatest Salesman (St. Martin’s Press).

Partner Center

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

12 Persuasion: So Easily Fooled

This module introduces several major principles in the process of persuasion. It offers an overview of the different paths to persuasion. It then describes how mindless processing makes us vulnerable to undesirable persuasion and some of the “tricks” that may be used against us.

Learning Objectives

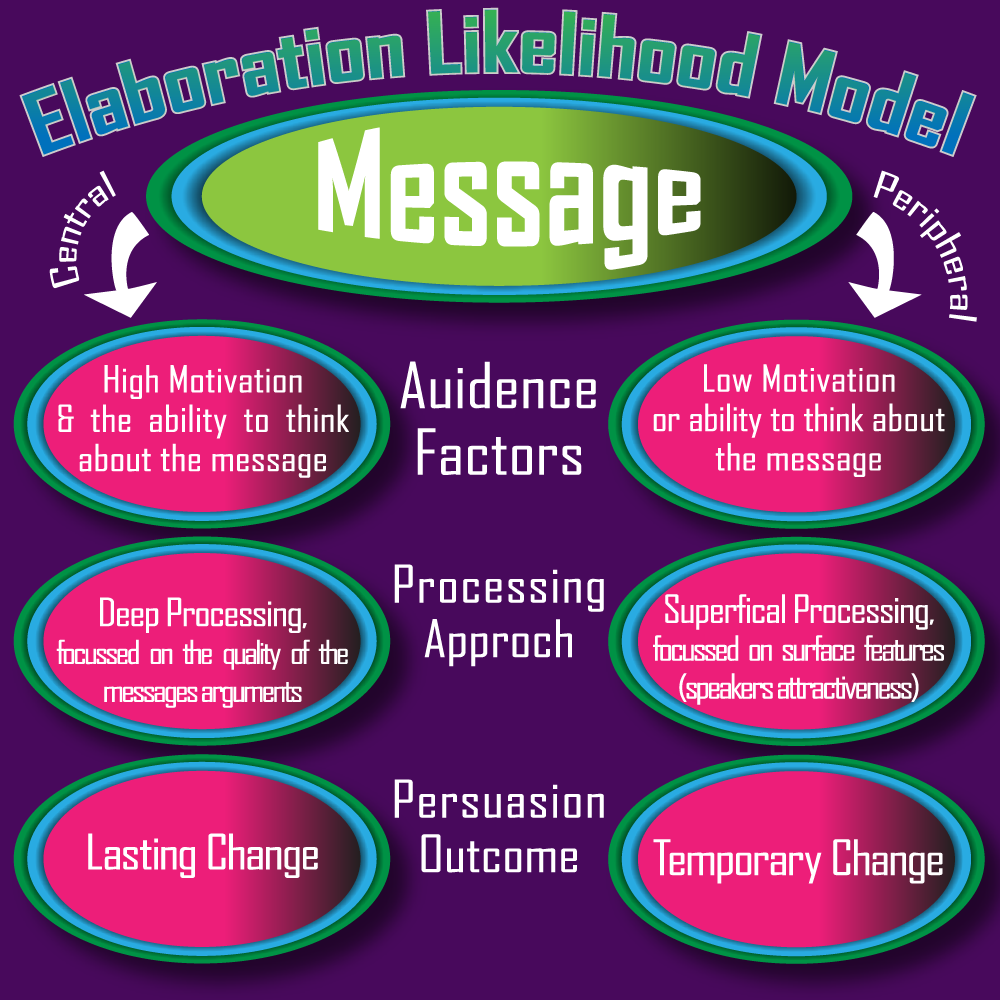

- Recognize the difference between the central and peripheral routes to persuasion.

- Understand the concepts of trigger features, fixed action patterns, heuristics, and mindless thinking, and how these processes are essential to our survival but, at the same time, leave us vulnerable to exploitation.

- Understand some common “tricks” persuasion artists may use to take advantage of us.

- Use this knowledge to make you less susceptible to unwanted persuasion.

Introduction

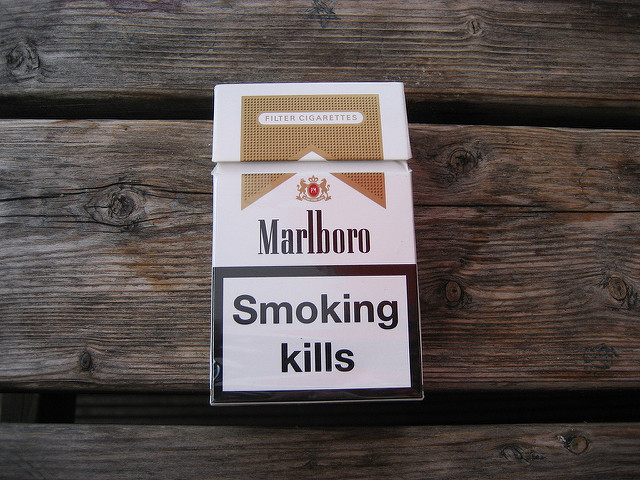

Have you ever tried to swap seats with a stranger on an airline? Ever negotiated the price of a car? Ever tried to convince someone to recycle, quit smoking, or make a similar change in health behaviors? If so, you are well versed with how persuasion can show up in everyday life.

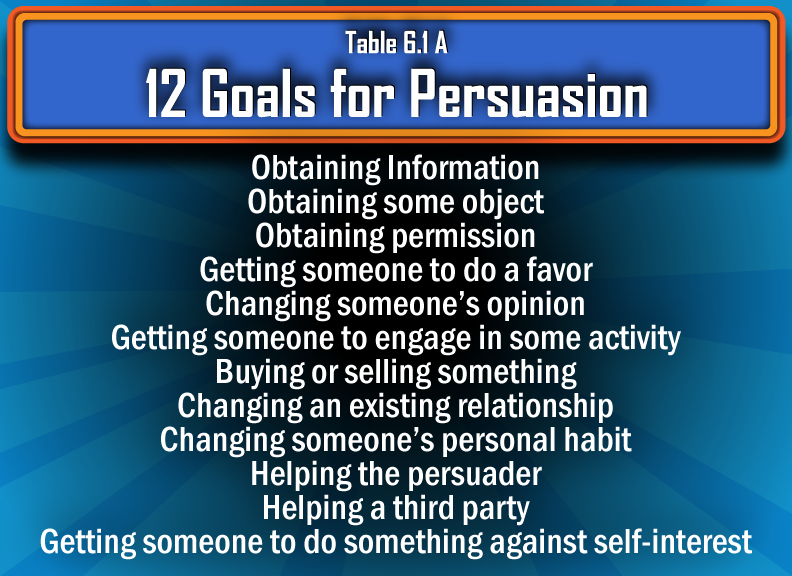

Persuasion has been defined as “the process by which a message induces change in beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors” ( Myers, 2011 ). Persuasion can take many forms. It may, for example, differ in whether it targets public compliance or private acceptance, is short-term or long-term, whether it involves slowly escalating commitments or sudden interventions and, most of all, in the benevolence of its intentions. When persuasion is well-meaning, we might call it education. When it is manipulative, it might be called mind control ( Levine, 2003 ).

Whatever the content, however, there is a similarity to the form of the persuasion process itself. As the advertising commentator Sid Bernstein once observed, “Of course, you sell candidates for political office the same way you sell soap or sealing wax or whatever; because, when you get right down to it, that’s the only way anything is sold” ( Levine, 2003 ).

Persuasion is one of the most studied of all social psychology phenomena. This module provides an introduction to several of its most important components.

Two Paths to Persuasion

Persuasion theorists distinguish between the central and peripheral routes to persuasion ( Petty & Cacioppo, 1986 ). The central route employs direct, relevant, logical messages. This method rests on the assumption that the audience is motivated, will think carefully about what is presented, and will react on the basis of your arguments. The central route is intended to produce enduring agreement. For example, you might decide to vote for a particular political candidate after hearing her speak and finding her logic and proposed policies to be convincing.

The peripheral route, on the other hand, relies on superficial cues that have little to do with logic. The peripheral approach is the salesman’s way of thinking. It requires a target who isn’t thinking carefully about what you are saying. It requires low effort from the target and often exploits rule-of-thumb heuristics that trigger mindless reactions (see below). It may be intended to persuade you to do something you do not want to do and might later be sorry you did. Advertisements, for example, may show celebrities, cute animals, beautiful scenery, or provocative sexual images that have nothing to do with the product. The peripheral approach is also common in the darkest of persuasion programs, such as those of dictators and cult leaders. Returning to the example of voting, you can experience the peripheral route in action when you see a provocative, emotionally charged political advertisement that tugs at you to vote a particular way.

Triggers and Fixed Action Patterns

The central route emphasizes objective communication of information. The peripheral route relies on psychological techniques. These techniques may take advantage of a target’s not thinking carefully about the message. The process mirrors a phenomenon in animal behavior known as fixed action patterns (FAPs) . These are sequences of behavior that occur in exactly the same fashion, in exactly the same order, every time they’re elicited. Cialdini ( 2008 ) compares it to a prerecorded tape that is turned on and, once it is, always plays to its finish. He describes it is as if the animal were turning on a tape recorder ( Cialdini, 2008 ). There is the feeding tape, the territorial tape, the migration tape, the nesting tape, the aggressive tape—each sequence ready to be played when a situation calls for it.

In humans fixed action patterns include many of the activities we engage in while mentally on “auto-pilot.” These behaviors are so automatic that it is very difficult to control them. If you ever feed a baby, for instance, nearly everyone mimics each bite the baby takes by opening and closing their own mouth! If two people near you look up and point you will automatically look up yourself. We also operate in a reflexive, non-thinking way when we make many decisions. We are more likely, for example, to be less critical about medical advice dispensed from a doctor than from a friend who read an interesting article on the topic in a popular magazine.

A notable characteristic of fixed action patterns is how they are activated. At first glance, it appears the animal is responding to the overall situation. For example, the maternal tape appears to be set off when a mother sees her hungry baby, or the aggressive tape seems to be activated when an enemy invades the animal’s territory. It turns out, however, that the on/off switch may actually be controlled by a specific, minute detail of the situation—maybe a sound or shape or patch of color. These are the hot buttons of the biological world—what Cialdini refers to as “ trigger features ” and biologists call “releasers.”

Humans are not so different. Take the example of a study conducted on various ways to promote a campus bake sale for charity ( Levine, 2003 ). Simply displaying the cookies and other treats to passersby did not generate many sales (only 2 out of 30 potential customers made a purchase). In an alternate condition, however, when potential customers were asked to “buy a cookie for a good cause” the number rose to 12 out of 30. It seems that the phrase “a good cause” triggered a willingness to act. In fact, when the phrase “a good cause” was paired with a locally-recognized charity (known for its food-for-the-homeless program) the numbers held steady at 14 out of 30. When a fictional good cause was used instead (the make believe “Levine House”) still 11 out of 30 potential customers made purchases and not one asked about the purpose or nature of the cause. The phrase “for a good cause” was an influential enough hot button that the exact cause didn’t seem to matter.

The effectiveness of peripheral persuasion relies on our frequent reliance on these sorts of fixed action patterns and trigger features. These mindless, rules-of-thumb are generally effective shortcuts for coping with the overload of information we all must confront. They serve as heuristics—mental shortcuts– that enable us to make decisions and solve problems quickly and efficiently. They also, however, make us vulnerable to uninvited exploitation through the peripheral route of persuasion.

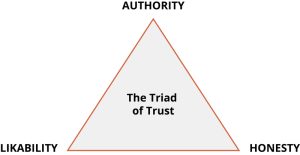

The Source of Persuasion: The Triad of Trustworthiness

Effective persuasion requires trusting the source of the communication. Studies have identified three characteristics that lead to trust: perceived authority, honesty, and likability.

When the source appears to have any or all of these characteristics, people not only are more willing to agree to their request but are willing to do so without carefully considering the facts. We assume we are on safe ground and are happy to shortcut the tedious process of informed decision making. As a result, we are more susceptible to messages and requests, no matter their particular content or how peripheral they may be.

From earliest childhood, we learn to rely on authority figures for sound decision making because their authority signifies status and power, as well as expertise. These two facets often work together. Authorities such as parents and teachers are not only our primary sources of wisdom while we grow up, but they control us and our access to the things we want. In addition, we have been taught to believe that respect for authority is a moral virtue. As adults, it is natural to transfer this respect to society’s designated authorities, such as judges, doctors, bosses, and religious leaders. We assume their positions give them special access to information and power. Usually we are correct, so that our willingness to defer to authorities becomes a convenient shortcut to sound decision making. Uncritical trust in authority may, however, lead to bad decisions. Perhaps the most famous study ever conducted in social psychology demonstrated that, when conditions were set up just so, two-thirds of a sample of psychologically normal men were willing to administer potentially lethal shocks to a stranger when an apparent authority in a laboratory coat ordered them to do so ( Milgram, 1974 ; Burger, 2009 ).

Uncritical trust in authority can be problematic for several reasons. First, even if the source of the message is a legitimate, well-intentioned authority, they may not always be correct. Second, when respect for authority becomes mindless, expertise in one domain may be confused with expertise in general. To assume there is credibility when a successful actor promotes a cold remedy, or when a psychology professor offers his views about politics, can lead to problems. Third, the authority may not be legitimate. It is not difficult to fake a college degree or professional credential or to buy an official-looking badge or uniform.

Honesty is the moral dimension of trustworthiness. Persuasion professionals have long understood how critical it is to their efforts. Marketers, for example, dedicate exorbitant resources to developing and maintaining an image of honesty. A trusted brand or company name becomes a mental shortcut for consumers. It is estimated that some 50,000 new products come out each year. Forrester Research, a marketing research company, calculates that children have seen almost six million ads by the age of 16. An established brand name helps us cut through this volume of information. It signals we are in safe territory. “The real suggestion to convey,” advertising leader Theodore MacManus observed in 1910, “is that the man manufacturing the product is an honest man, and the product is an honest product, to be preferred above all others” ( Fox, 1997 ).

If we know that celebrities aren’t really experts, and that they are being paid to say what they’re saying, why do their endorsements sell so many products? Ultimately, it is because we like them. More than any single quality, we trust people we like. Roger Ailes, a public relations adviser to Presidents Reagan and George H.W. Bush, observed: “If you could master one element of personal communication that is more powerful than anything . . . it is the quality of being likable. I call it the magic bullet, because if your audience likes you, they’ll forgive just about everything else you do wrong. If they don’t like you, you can hit every rule right on target and it doesn’t matter.”

The mix of qualities that make a person likable are complex and often do not generalize from one situation to another. One clear finding, however, is that physically attractive people tend to be liked more. In fact, we prefer them to a disturbing extent: Various studies have shown we perceive attractive people as smarter, kinder, stronger, more successful, more socially skilled, better poised, better adjusted, more exciting, more nurturing, and, most important, of higher moral character. All of this is based on no other information than their physical appearance (e.g., Dion, Berscheid, & Walster, 1972 ).

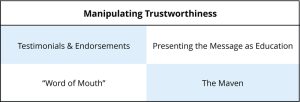

Manipulating the Perception of Trustworthiness

The perception of trustworthiness is highly susceptible to manipulation. Levine ( 2003 ) lists some of the most common psychological strategies that are used to achieve this effect:

Testimonials and Endorsement

This technique employs someone who people already trust to testify about the product or message being sold. The technique goes back to the earliest days of advertising when satisfied customers might be shown describing how a patent medicine cured their life-long battle with “nerves” or how Dr. Scott’s Electric Hair Brush healed their baldness (“My hair (was) falling out, and I was rapidly becoming bald, but since using the brush a thick growth of hair has made its appearance, quite equal to that I had before previous to its falling out,” reported a satisfied customer in an 1884 ad for the product). Similarly, Kodak had Prince Henri D’Orleans and others endorse the superior quality of their camera (“The results are marvellous[sic]. The enlargements which you sent me are superb,“ stated Prince Henri D’Orleans in a 1888 ad).

Celebrity endorsements are a frequent feature in commercials aimed at children. The practice has aroused considerable ethical concern, and research shows the concern is warranted. In a study funded by the Federal Trade Commission, more than 400 children ages 8 to 14 were shown one of various commercials for a model racing set. Some of the commercials featured an endorsement from a famous race car driver, some included real racing footage, and others included neither. Children who watched the celebrity endorser not only preferred the toy cars more but were convinced the endorser was an expert about the toys. This held true for children of all ages. In addition, they believed the toy race cars were bigger, faster, and more complex than real race cars they saw on film. They were also less likely to believe the commercial was staged ( Ross et al., 1984 ).

Presenting the Message as Education

The message may be framed as objective information. Salespeople, for example, may try to convey the impression they are less interested in selling a product than helping you make the best decision. The implicit message is that being informed is in everyone’s best interest, because they are confident that when you understand what their product has to offer that you will conclude it is the best choice. Levine ( 2003 ) describes how, during training for a job as a used car salesman, he was instructed: “If the customer tells you they do not want to be bothered by a salesperson, your response is ‘I’m not a salesperson, I’m a product consultant. I don’t give prices or negotiate with you. I’m simply here to show you our inventory and help you find a vehicle that will fit your needs.’”

Word of Mouth

Imagine you read an ad that claims a new restaurant has the best food in your city. Now, imagine a friend tells you this new restaurant has the best food in the city. Who are you more likely to believe? Surveys show we turn to people around us for many decisions. A 1995 poll found that 70% of Americans rely on personal advice when selecting a new doctor. The same poll found that 53% of moviegoers are influenced by the recommendation of a person they know. In another survey, 91% said they’re likely to use another person’s recommendation when making a major purchase.

Persuasion professionals may exploit these tendencies. Often, in fact, they pay for the surveys. Using this data, they may try to disguise their message as word of mouth from your peers. For example, Cornerstone Promotion, a leading marketing firm that advertises itself as under-the-radar marketing specialists, sometimes hires children to log into chat rooms and pretend to be fans of one of their clients or pays students to throw parties where they subtly circulate marketing material among their classmates.

More persuasive yet, however, is to involve peers face-to-face. Rather than over-investing in formal advertising, businesses and organizations may plant seeds at the grassroots level hoping that consumers themselves will then spread the word to each other. The seeding process begins by identifying so-called information hubs—individuals the marketers believe can and will reach the most other people.

The seeds may be planted with established opinion leaders. Software companies, for example, give advance copies of new computer programs to professors they hope will recommend it to students and colleagues. Pharmaceutical companies regularly provide travel expenses and speaking fees to researchers willing to lecture to health professionals about the virtues of their drugs. Hotels give travel agents free weekends at their resorts in the hope they’ll later recommend them to clients seeking advice.

There is a Yiddish word, maven, which refers to a person who’s an expert or a connoisseur, as in a friend who knows where to get the best price on a sofa or the co-worker you can turn to for advice about where to buy a computer. They (a) know a lot of people, (b) communicate a great deal with people, (c) are more likely than others to be asked for their opinions, and (d) enjoy spreading the word about what they know and think. Most important of all, they are trusted. As a result, mavens are often targeted by persuasion professionals to help spread their message.

Other Tricks of Persuasion

There are many other mindless, mental shortcuts—heuristics and fixed action patterns—that leave us susceptible to persuasion. A few examples:

- “Free Gifts” & Reciprocity

Social Proof

- Getting a Foot-in-the-Door

- A Door-in-the-Face

- “And That’s Not All”

The Sunk Cost Trap

- Scarcity & Psychological Reactance

Reciprocity

“There is no duty more indispensable than that of returning a kindness,” wrote Cicero. Humans are motivated by a sense of equity and fairness. When someone does something for us or gives us something, we feel obligated to return the favor in kind. It triggers one of the most powerful of social norms, the reciprocity rule, whereby we feel compelled to repay, in equitable value, what another person has given to us.

Gouldner ( 1960 ), in his seminal study of the reciprocity rule, found it appears in every culture. It lays the basis for virtually every type of social relationship, from the legalities of business arrangements to the subtle exchanges within a romance. A salesperson may offer free gifts, concessions, or their valuable time in order to get us to do something for them in return. For example, if a colleague helps you when you’re busy with a project, you might feel obliged to support her ideas for improving team processes. You might decide to buy more from a supplier if they have offered you an aggressive discount. Or, you might give money to a charity fundraiser who has given you a flower in the street ( Cialdini, 2008 ; Levine, 2003 ).

If everyone is doing it, it must be right. People are more likely to work late if others on their team are doing the same, to put a tip in a jar that already contains money, or eat in a restaurant that is busy. This principle derives from two extremely powerful social forces—social comparison and conformity. We compare our behavior to what others are doing and, if there is a discrepancy between the other person and ourselves, we feel pressure to change ( Cialdini, 2008 ).

The principle of social proof is so common that it easily passes unnoticed. Advertisements, for example, often consist of little more than attractive social models appealing to our desire to be one of the group. For example, the German candy company Haribo suggests that when you purchase their products you are joining a larger society of satisfied customers: “Kids and grown-ups love it so– the happy world of Haribo”. Sometimes social cues are presented with such specificity that it is as if the target is being manipulated by a puppeteer—for example, the laugh tracks on situation comedies that instruct one not only when to laugh but how to laugh. Studies find these techniques work. Fuller and Skeehy-Skeffington ( 1974 ), for example, found that audiences laughed longer and more when a laugh track accompanied the show than when it did not, even though respondents knew the laughs they heard were connived by a technician from old tapes that had nothing to do with the show they were watching. People are particularly susceptible to social proof (a) when they are feeling uncertain, and (b) if the people in the comparison group seem to be similar to ourselves. As P.T. Barnum once said, “Nothing draws a crowd like a crowd.”

Commitment and Consistency

Westerners have a desire to both feel and be perceived to act consistently. Once we have made an initial commitment, it is more likely that we will agree to subsequent commitments that follow from the first. Knowing this, a clever persuasion artist might induce someone to agree to a difficult-to-refuse small request and follow this with progressively larger requests that were his target from the beginning. The process is known as getting a foot in the door and then gradually escalating the commitments .

Paradoxically, we are less likely to say “No” to a large request than we are to a small request when it follows this pattern. This can have costly consequences. Levine ( 2003 ), for example, found ex-cult members tend to agree with the statement: “Nobody ever joins a cult. They just postpone the decision to leave.”

A Door in the Face

Some techniques bring a paradoxical approach to the escalation sequence by pushing a request to or beyond its acceptable limit and then backing off. In the door-in-the-face (sometimes called the reject-then-compromise) procedure, the persuader begins with a large request they expect will be rejected. They want the door to be slammed in their face. Looking forlorn, they now follow this with a smaller request, which, unknown to the customer, was their target all along.

In one study, for example, Mowen and Cialdini ( 1980 ), posing as representatives of the fictitious “California Mutual Insurance Co.,” asked university students walking on campus if they’d be willing to fill out a survey about safety in the home or dorm. The survey, students were told, would take about 15 minutes. Not surprisingly, most of the students declined—only one out of four complied with the request. In another condition, however, the researchers door-in-the-faced them by beginning with a much larger request. “The survey takes about two hours,” students were told. Then, after the subject declined to participate, the experimenters retreated to the target request: “. . . look, one part of the survey is particularly important and is fairly short. It will take only 15 minutes to administer.” Almost twice as many now complied.

And That’s Not All!

The that’s-not-all technique also begins with the salesperson asking a high price. This is followed by several seconds’ pause during which the customer is kept from responding. The salesperson then offers a better deal by either lowering the price or adding a bonus product. That’s-not-all is a variation on door-in-the-face. Whereas the latter begins with a request that will be rejected, however, that’s-not-all gains its influence by putting the customer on the fence, allowing them to waver and then offering them a comfortable way off.

Burger ( 1986 ) demonstrated the technique in a series of field experiments. In one study, for example, an experimenter-salesman told customers at a student bake sale that cupcakes cost 75 cents. As this price was announced, another salesman held up his hand and said, “Wait a second,” briefly consulted with the first salesman, and then announced (“that’s-not-all”) that the price today included two cookies. In a control condition, customers were offered the cupcake and two cookies as a package for 75 cents right at the onset. The bonus worked magic: Almost twice as many people bought cupcakes in the that’s-not-all condition (73%) than in the control group (40%).

Sunk cost is a term used in economics referring to nonrecoverable investments of time or money. The trap occurs when a person’s aversion to loss impels them to throw good money after bad, because they don’t want to waste their earlier investment. This is vulnerable to manipulation. The more time and energy a cult recruit can be persuaded to spend with the group, the more “invested” they will feel, and, consequently, the more of a loss it will feel to leave that group. Consider the advice of billionaire investor Warren Buffet: “When you find yourself in a hole, the best thing you can do is stop digging” ( Levine, 2003 ).

Scarcity and Psychological Reactance

People tend to perceive things as more attractive when their availability is limited, or when they stand to lose the opportunity to acquire them on favorable terms ( Cialdini, 2008 ). Anyone who has encountered a willful child is familiar with this principle. In a classic study, Brehm & Weinraub ( 1977 ), for example, placed 2-year-old boys in a room with a pair of equally attractive toys. One of the toys was placed next to a plexiglass wall; the other was set behind the plexiglass. For some boys, the wall was 1 foot high, which allowed the boys to easily reach over and touch the distant toy. Given this easy access, they showed no particular preference for one toy or the other. For other boys, however, the wall was a formidable 2 feet high, which required them to walk around the barrier to touch the toy. When confronted with this wall of inaccessibility, the boys headed directly for the forbidden fruit, touching it three times as quickly as the accessible toy.

Research shows that much of that 2-year-old remains in adults, too. People resent being controlled. When a person seems too pushy, we get suspicious, annoyed, often angry, and yearn to retain our freedom of choice more than before. Brehm ( 1966 ) labeled this the principle of psychological reactance .

The most effective way to circumvent psychological reactance is to first get a foot in the door and then escalate the demands so gradually that there is seemingly nothing to react against. Hassan ( 1988 ), who spent many years as a higher-up in the “Moonies” cult, describes how they would shape behaviors subtly at first, then more forcefully. The material that would make up the new identity of a recruit was doled out gradually, piece by piece, only as fast as the person was deemed ready to assimilate it. The rule of thumb was to “tell him only what he can accept.” He continues: “Don’t sell them [the converts] more than they can handle . . . . If a recruit started getting angry because he was learning too much about us, the person working on him would back off and let another member move in …..”

Defending Against Unwelcome Persuasion

The most commonly used approach to help people defend against unwanted persuasion is known as the “inoculation” method. Research has shown that people who are subjected to weak versions of a persuasive message are less vulnerable to stronger versions later on, in much the same way that being exposed to small doses of a virus immunizes you against full-blown attacks. In a classic study by McGuire ( 1964 ), subjects were asked to state their opinion on an issue. They were then mildly attacked for their position and then given an opportunity to refute the attack. When later confronted by a powerful argument against their initial opinion, these subjects were more resistant than were a control group. In effect, they developed defenses that rendered them immune.

Sagarin and his colleagues have developed a more aggressive version of this technique that they refer to as “stinging” ( Sagarin, Cialdini, Rice, & Serna, 2002 ). Their studies focused on the popular advertising tactic whereby well-known authority figures are employed to sell products they know nothing about, for example, ads showing a famous astronaut pontificating on Rolex watches. In a first experiment, they found that simply forewarning people about the deviousness of these ads had little effect on peoples’ inclination to buy the product later. Next, they stung the subjects. This time, they were immediately confronted with their gullibility. “Take a look at your answer to the first question. Did you find the ad to be even somewhat convincing? If so, then you got fooled. … Take a look at your answer to the second question. Did you notice that this ‘stockbroker’ was a fake?” They were then asked to evaluate a new set of ads. The sting worked. These subjects were not only more likely to recognize the manipulativeness of deceptive ads; they were also less likely to be persuaded by them.

Anti-vulnerability trainings such as these can be helpful. Ultimately, however, the most effective defense against unwanted persuasion is to accept just how vulnerable we are. One must, first, accept that it is normal to be vulnerable and, second, to learn to recognize the danger signs when we are falling prey. To be forewarned is to be forearmed.

This module has provided a brief introduction to the psychological processes and subsequent “tricks” involved in persuasion. It has emphasized the peripheral route of persuasion because this is when we are most vulnerable to psychological manipulation. These vulnerabilities are side effects of “normal” and usually adaptive psychological processes. Mindless heuristics offer shortcuts for coping with a hopelessly complicated world. They are necessities for human survival. All, however, underscore the dangers that accompany any mindless thinking.

Text Attribution

Media attributions.

- if winter ends

- Bake Sale Cupcakes and M&M Cookies

- Figure 12.1

- Idris Elba at the ‘Defeating Ebola in Sierrra Leone’ conference

- Figure 12.2

- New Orleans LA ~ Acme Oyster House ~ Famous Restaurant

- 99c Store Going Out of Business

Persuasion that employs direct, relevant, logical messages.

Persuasion that relies on superficial cues that have little to do with logic.

A mental shortcut or rule of thumb that reduces complex mental problems to more simple rule-based decisions.

Sequences of behavior that occur in exactly the same fashion, in exactly the same order, every time they are elicited.

Specific, sometimes minute, aspects of a situation that activate fixed action patterns.

The act of exchanging goods or services. By giving a person a gift, the principle of reciprocity can be used to influence others; they then feel obligated to give back.

The mental shortcut based on the assumption that, if everyone is doing it, it must be right.

Obtaining a small, initial commitment.

A pattern of small, progressively escalating demands is less likely to be rejected than a single large demand made all at once.

A reaction to people, rules, requirements, or offerings that are perceived to limit freedoms.

An Introduction to Social Psychology Copyright © 2022 by Thomas Edison State University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Social Psychology

Learning objectives.

- Explain how people’s attitudes are externally changed through persuasion

- Compare the peripheral and central routes to persuasion

Figure 1. We encounter persuasion attempts everywhere. Persuasion is not limited to formal advertising; we are confronted with it throughout our everyday world. (credit: Robert Couse-Baker)

Yale Attitude Change Approach

The topic of persuasion has been one of the most extensively researched areas in social psychology (Fiske et al., 2010). During the Second World War, Carl Hovland extensively researched persuasion for the U.S. Army. After the war, Hovland continued his exploration of persuasion at Yale University. Out of this work came a model called the Yale attitude change approach , which describes the conditions under which people tend to change their attitudes. Hovland demonstrated that certain features of the source of a persuasive message, the content of the message, and the characteristics of the audience will influence the persuasiveness of a message (Hovland, Janis, & Kelley, 1953).

Features of the source of the persuasive message include the credibility of the speaker (Hovland & Weiss, 1951) and the physical attractiveness of the speaker (Eagly & Chaiken, 1975; Petty, Wegener, & Fabrigar, 1997). Thus, speakers who are credible, or have expertise on the topic, and who are deemed as trustworthy are more persuasive than less credible speakers. Similarly, more attractive speakers are more persuasive than less attractive speakers. The use of famous actors and athletes to advertise products on television and in print relies on this principle. The immediate and long-term impact of the persuasion also depends, however, on the credibility of the messenger (Kumkale & Albarracín, 2004).

Features of the message itself that affect persuasion include subtlety (the quality of being important, but not obvious) (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986; Walster & Festinger, 1962); sidedness (that is, having more than one side) (Crowley & Hoyer, 1994; Igou & Bless, 2003; Lumsdaine & Janis, 1953); timing (Haugtvedt & Wegener, 1994; Miller & Campbell, 1959), and whether both sides are presented. Subtle messages are more persuasive than direct messages. Arguments that occur first, such as in a debate, are more influential if messages are given back-to-back. However, if there is a delay after the first message, and before the audience needs to make a decision, the last message presented will tend to be more persuasive (Miller & Campbell, 1959).

Features of the audience that affect persuasion are attention (Albarracín & Wyer, 2001; Festinger & Maccoby, 1964), intelligence, self-esteem (Rhodes & Wood, 1992), and age (Krosnick & Alwin, 1989). In order to be persuaded, audience members must be paying attention. People with lower intelligence are more easily persuaded than people with higher intelligence; whereas people with moderate self-esteem are more easily persuaded than people with higher or lower self-esteem (Rhodes & Wood, 1992). Finally, younger adults aged 18–25 are more persuadable than older adults.

Elaboration Likelihood Model

An especially popular model that describes the dynamics of persuasion is the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). The elaboration likelihood model considers the variables of the attitude change approach—that is, features of the source of the persuasive message, contents of the message, and characteristics of the audience are used to determine when attitude change will occur. According to the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion, there are two main routes that play a role in delivering a persuasive message: central and peripheral (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Persuasion can take one of two paths, and the durability of the end result depends on the path.

The central route is logic-driven and uses data and facts to convince people of an argument’s worthiness. For example, a car company seeking to persuade you to purchase their model will emphasize the car’s safety features and fuel economy. This is a direct route to persuasion that focuses on the quality of the information. In order for the central route of persuasion to be effective in changing attitudes, thoughts, and behaviors, the argument must be strong and, if successful, will result in lasting attitude change.

The central route to persuasion works best when the target of persuasion, or the audience, is analytical and willing to engage in the processing of the information. From an advertiser’s perspective, what products would be best sold using the central route to persuasion? What audience would most likely be influenced to buy the product? One example is buying a computer. It is likely, for example, that small business owners might be especially influenced by the focus on the computer’s quality and features such as processing speed and memory capacity.

The peripheral route is an indirect route that uses peripheral cues to associate positivity with the message (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Instead of focusing on the facts and a product’s quality, the peripheral route relies on association with positive characteristics such as positive emotions and celebrity endorsement. For example, having a popular athlete advertise athletic shoes is a common method used to encourage young adults to purchase the shoes. This route to attitude change does not require much effort or information processing. This method of persuasion may promote positivity toward the message or product, but it typically results in less permanent attitude or behavior change. The audience does not need to be analytical or motivated to process the message. In fact, a peripheral route to persuasion may not even be noticed by the audience, for example in the strategy of product placement. Product placement refers to putting a product with a clear brand name or brand identity in a TV show or movie to promote the product (Gupta & Lord, 1998). For example, one season of the reality series American Idol prominently showed the panel of judges drinking out of cups that displayed the Coca-Cola logo. What other products would be best sold using the peripheral route to persuasion? Another example is clothing: A retailer may focus on celebrities that are wearing the same style of clothing.

Foot-in-the-door Technique

Researchers have tested many persuasion strategies that are effective in selling products and changing people’s attitude, ideas, and behaviors. One effective strategy is the foot-in-the-door technique (Cialdini, 2001; Pliner, Hart, Kohl, & Saari, 1974). Using the foot-in-the-door technique , the persuader gets a person to agree to bestow a small favor or to buy a small item, only to later request a larger favor or purchase of a bigger item. The foot-in-the-door technique was demonstrated in a study by Freedman and Fraser (1966) in which participants who agreed to post small sign in their yard or sign a petition were more likely to agree to put a large sign in their yard than people who declined the first request (Figure 3). Research on this technique also illustrates the principle of consistency (Cialdini, 2001): Our past behavior often directs our future behavior, and we have a desire to maintain consistency once we have a committed to a behavior.

Figure 3 . With the foot-in-the-door technique, getting someone to agree to a small request such as (a) wearing a campaign button can make them more likely to agree to a larger request, such as (b) putting campaigns signs in your yard. (credit a: modification of work by Joe Crawford; credit b: modification of work by “shutterblog”/Flickr)

A common application of foot-in-the-door is when teens ask their parents for a small permission (for example, extending curfew by a half hour) and then asking them for something larger. Having granted the smaller request increases the likelihood that parents will acquiesce with the later, larger request.

How would a store owner use the foot-in-the-door technique to sell you an expensive product? For example, say that you are buying the latest model smartphone, and the salesperson suggests you purchase the best data plan. You agree to this. The salesperson then suggests a bigger purchase—the three-year extended warranty. After agreeing to the smaller request, you are more likely to also agree to the larger request. You may have encountered this if you have bought a car. When salespeople realize that a buyer intends to purchase a certain model, they might try to get the customer to pay for many or most available options on the car. Another example of the foot-in-the-door technique would be applied to an individual in the market for a used car who decides to buy a fully loaded new car. Why? Because the salesperson convinced the buyer that they need a car that has all of the safety features that were not available in the used car.

Link to Learning

Read more about persuasion at The Noba Project website .

Think It Over

Describe a time when you or someone you know used the foot-in-the-door technique to gain someone’s compliance.

Contribute!

Improve this page Learn More

- Modification and adaptation, addition of link to learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Attitudes and Persuasion. Authored by : OpenStax College. Located at : https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/12-3-attitudes-and-persuasion . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Psychological Persuasion Techniques

Persuasion Techniques That Really Work

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Shereen Lehman, MS, is a healthcare journalist and fact checker. She has co-authored two books for the popular Dummies Series (as Shereen Jegtvig).

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Shereen-Lehman-MS-1000-b8eb65ee2fd1437094f29996bd4f8baa.jpg)

Sam Edwards / Getty Images

Persuasion Techniques in Daily Life

Key persuasion techniques.

- Effects of Persuasion Techniques

- Resisting Persuasion

Persuasion techniques are strategies that can help you convince people to see things your way. Marketers often use these tactics to get people to buy their products or sign up for their services.

It's not uncommon for people to see or hear hundreds of advertisements each day on websites, television programs, podcasts, and social media. Such messages can vary in their effectiveness, but changes are good that they are employing some type of psychological persuasion technique to try to get you to buy something.

At a Glance

Because persuasion is such a pervasive component of our lives, it is often too easy to overlook how outside sources influence us. Learning more about these tactics can help you become more aware of when you've been influenced. It can also help you become more persuasive in your own life, whether you are advocating for a promotion at work or convincing your friends to try the newest restaurant in town.

Persuasion is not just something that is useful to marketers and salesmen, however. Learning how to utilize these techniques in daily life can help you become a better negotiator and make it more likely that you will get what you want, whether you are trying to convince your kids to eat their vegetables or persuade your boss to give you that raise.

Because influence is so useful in so many aspects of daily life, persuasion techniques have been studied and observed since ancient times. It wasn’t until the early 20th century, however, that social psychologists began to formally study these powerful tools of human influence.

The ultimate goal of persuasion is to convince the target to internalize the persuasive argument and adopt this new attitude as a part of their core belief system.

The following are just a few of the highly effective persuasion techniques . Other methods include the use of rewards, punishments, positive or negative expertise, and many others.

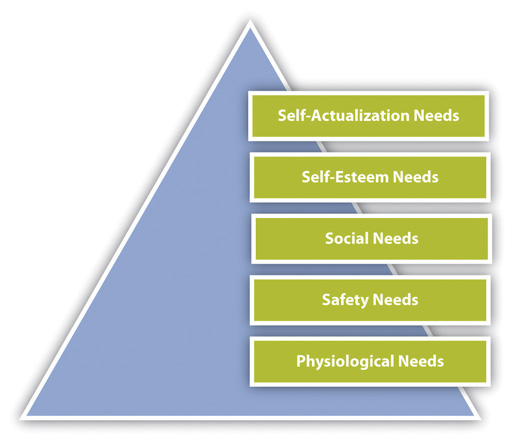

Create a Need

One method of persuasion involves creating a need or appealing to a previously existing need. This type of persuasion appeals to a person's fundamental needs for shelter, love, self-esteem, and self-actualization.

Marketers often use this strategy to sell their products. Consider, for example, how many advertisements suggest that people need to purchase a particular product in order to be happy, safe, loved, or admired.

By creating a need, marketers can then offer their goods or services as the tool necessary to satisfy the need.

Appeal to Social Needs

Another very effective persuasive method appeals to the need to be popular, prestigious, or similar to others, often referred to as social proof. Television commercials provide many examples of this type of persuasion, where viewers are encouraged to purchase items to be like everyone else or be like a well-known or well-respected person.

Television advertisements are a significant source of exposure to persuasion considering that the average American watches between 2.79 hours per day.

Social media advertising relies on appealing to these social needs. Online influencers create images that depict appealing and aspirational imagery. People then feel persuaded to purchase the items they hope will give them the same look or lifestyle.

Use Loaded Words and Images

Persuasion also often makes use of loaded words and images. Loaded words and evocative images can create emotional responses that go beyond what the literal meaning.

Advertisers are well aware of the power of positive words, which is why so many advertisers utilize phrases such as "New and Improved" or "All Natural."

Get Your Foot in the Door

Another approach that is often effective in getting people to comply with a request is known as the "foot-in-the-door" technique. This persuasion strategy involves getting a person to agree to a small request, like asking them to purchase a small item, followed by making a much larger request.

By getting the person to agree to the small initial favor, the requester already has their "foot in the door," so to speak. We are then more likely to comply with the larger request.

For example, a neighbor asks you to babysit their two children for an hour or two. Once you agree to the smaller request, they then ask if you can just babysit the kids for the rest of the day.

This is a great example of what psychologists refer to as the rule of commitment , and marketers often use this strategy to encourage consumers to buy products and services.

How It Works

Once you have already agreed to a smaller request, you might feel a sense of obligation to also agree to a larger request.

Go Big and Then Small

This approach is the opposite of the foot-in-the-door approach. A salesperson will begin by making a large, often unrealistic request. The individual responds by refusing, figuratively slamming the door on the sale.

The salesperson responds by making a much smaller request, which often comes off as conciliatory. People often feel obligated to respond to these offers. Since they refused that initial request, people often feel compelled to help the salesperson by accepting the smaller request.

Utilize the Power of Reciprocity

When people do you a favor, you probably feel an almost overwhelming obligation to return the favor in kind. This is known as the norm of reciprocity , a social obligation to do something for someone else because they first did something for you.

Marketers might utilize this tendency by making it seem like they are doing you a kindness, such as including "extras" or discounts, which then compels people to accept the offer and make a purchase.

Create an Anchor Point

The anchoring bias is a subtle cognitive bias that can have a powerful influence on negotiations and decisions. When trying to arrive at a decision, the first offer has the tendency to become an anchoring point for all future negotiations.

So, if you are trying to negotiate a pay increase, being the first person to suggest a number, especially if that number is a bit high, can help influence the future negotiations in your favor. That first number will become the starting point.

While you might not get that amount, starting high might lead to a higher offer from your employer.

Limit Your Availability

Psychologist Robert Cialdini is famous for the six principles of influence. One of the key principles he identified is known as scarcity or limiting the availability of something. Cialdini suggests that things become more attractive when they are scarce or limited.

People are more likely to buy something if they learn that it is the last one or that the sale will be ending soon.

An artist, for example, might only make a limited run of a particular print. Since there are only a few prints available for sale, people might be more likely to make a purchase before they are gone.

Recognizing the Effects of Persuasion Techniques

The examples above are just a few of the many persuasion techniques described by social psychologists. Look for examples of persuasion in your daily experience.

An interesting experiment is to view a half-hour of a random television program and note every instance of persuasive advertising. You might be surprised by the sheer amount of persuasive techniques used in such a brief period of time.

How People Resist Persuasion Techniques

It is also important to remember that persuasion isn't always effective. In many cases, we tend to resist influence, particularly if we are worried that we are being deceived or are reluctant to change.

Counter-Arguments

We may contest the message and provide opposing arguments. Sometimes, this involves contesting the message, such as finding facts or counterarguments that present opposing information. In other cases, we might try to discredit the source of the information.

In other cases, we may simply try to avoid the message. Examples can include muting advertisements on tv commercials or installing ad blockers when browsing online. It isn't unusual to physically avoid such messages. We might avoid shopping centers or other places where we are likely to encounter salespeople.

Certain types of bias can also contribute to persuasion resistance. For example, many people now recognize the serious health risks of smoking, the optimism bias often leads them to think that these hazards are not likely to affect them.

Resistance to persuasive messages can come in many forms. We may present counter arguments, try to avoid persuasive messages, or fall prey to biases that affect our interpretation of the messages we hear.

Cialdini R, Cliffe S. The uses (and abuses) of influence . Harv Bus Rev . 2013;91(7-8):76-132.

Alkış N, Taşkaya Temizel T. The impact of individual differences on influence strategies . Personality and Individual Differences . 2015;87:147-152. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.07.037

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. American Time Use Survey Summary.

Comello ML, Myrick JG, Raphiou AL. A health fundraising experiment using the "foot-in-the-door" technique . Health Mark Q . 2016;33(3):206-220. doi:10.1080/07359683.2016.1199209

Alslaity A, Tran T. Users' responsiveness to persuasive techniques in recommender systems . Front Artif Intell . 2021;4:679459. doi:10.3389/frai.2021.679459

Cialdini R, Cliffe S. The uses (and abuses) of influence . Harv Bus Rev . 2013;91(7-8):76‐132.

Fransen ML, Smit EG, Verlegh PW. Strategies and motives for resistance to persuasion: an integrative framework . Front Psychol . 2015;6:1201. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01201

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Learning Objectives

- Explain how people’s attitudes are externally changed through persuasion

- Compare the peripheral and central routes to persuasion

Yale Attitude Change Approach

The topic of persuasion has been one of the most extensively researched areas in social psychology (Fiske et al., 2010). During the Second World War, Carl Hovland extensively researched persuasion for the U.S. Army. After the war, Hovland continued his exploration of persuasion at Yale University. Out of this work came a model called the Yale attitude change approach , which describes the conditions under which people tend to change their attitudes. Hovland demonstrated that certain features of the source of a persuasive message, the content of the message, and the characteristics of the audience will influence the persuasiveness of a message (Hovland, Janis, & Kelley, 1953).

Features of the source of the persuasive message include the credibility of the speaker (Hovland & Weiss, 1951) and the physical attractiveness of the speaker (Eagly & Chaiken, 1975; Petty, Wegener, & Fabrigar, 1997). Thus, speakers who are credible, or have expertise on the topic, and who are deemed as trustworthy are more persuasive than less credible speakers. Similarly, more attractive speakers are more persuasive than less attractive speakers. The use of famous actors and athletes to advertise products on television and in print relies on this principle. The immediate and long term impact of the persuasion also depends, however, on the credibility of the messenger (Kumkale & Albarracín, 2004).

Features of the message itself that affect persuasion include subtlety (the quality of being important, but not obvious) (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986; Walster & Festinger, 1962); sidedness (that is, having more than one side) (Crowley & Hoyer, 1994; Igou & Bless, 2003; Lumsdaine & Janis, 1953); timing (Haugtvedt & Wegener, 1994; Miller & Campbell, 1959), and whether both sides are presented. Messages that are more subtle are more persuasive than direct messages. Arguments that occur first, such as in a debate, are more influential if messages are given back-to-back. However, if there is a delay after the first message, and before the audience needs to make a decision, the last message presented will tend to be more persuasive (Miller & Campbell, 1959).

Features of the audience that affect persuasion are attention (Albarracín & Wyer, 2001; Festinger & Maccoby, 1964), intelligence, self-esteem (Rhodes & Wood, 1992), and age (Krosnick & Alwin, 1989). In order to be persuaded, audience members must be paying attention. People with lower intelligence are more easily persuaded than people with higher intelligence; whereas people with moderate self-esteem are more easily persuaded than people with higher or lower self-esteem (Rhodes & Wood, 1992). Finally, younger adults aged 18–25 are more persuadable than older adults.

Elaboration Likelihood Model

An especially popular model that describes the dynamics of persuasion is the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). The elaboration likelihood model considers the variables of the attitude change approach—that is, features of the source of the persuasive message, contents of the message, and characteristics of the audience are used to determine when attitude change will occur. According to the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion, there are two main routes that play a role in delivering a persuasive message: central and peripheral (Figure 2).

The central route is logic driven and uses data and facts to convince people of an argument’s worthiness. For example, a car company seeking to persuade you to purchase their model will emphasize the car’s safety features and fuel economy. This is a direct route to persuasion that focuses on the quality of the information. In order for the central route of persuasion to be effective in changing attitudes, thoughts, and behaviors, the argument must be strong and, if successful, will result in lasting attitude change.

The central route to persuasion works best when the target of persuasion, or the audience, is analytical and willing to engage in processing of the information. From an advertiser’s perspective, what products would be best sold using the central route to persuasion? What audience would most likely be influenced to buy the product? One example is buying a computer. It is likely, for example, that small business owners might be especially influenced by the focus on the computer’s quality and features such as processing speed and memory capacity.

The peripheral route is an indirect route that uses peripheral cues to associate positivity with the message (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Instead of focusing on the facts and a product’s quality, the peripheral route relies on association with positive characteristics such as positive emotions and celebrity endorsement. For example, having a popular athlete advertise athletic shoes is a common method used to encourage young adults to purchase the shoes. This route to attitude change does not require much effort or information processing. This method of persuasion may promote positivity toward the message or product, but it typically results in less permanent attitude or behavior change. The audience does not need to be analytical or motivated to process the message. In fact, a peripheral route to persuasion may not even be noticed by the audience, for example in the strategy of product placement. Product placement refers to putting a product with a clear brand name or brand identity in a TV show or movie to promote the product (Gupta & Lord, 1998). For example, one season of the reality series American Idol prominently showed the panel of judges drinking out of cups that displayed the Coca-Cola logo. What other products would be best sold using the peripheral route to persuasion? Another example is clothing: A retailer may focus on celebrities that are wearing the same style of clothing.

Foot-in-the-door Technique

Researchers have tested many persuasion strategies that are effective in selling products and changing people’s attitude, ideas, and behaviors. One effective strategy is the foot-in-the-door technique (Cialdini, 2001; Pliner, Hart, Kohl, & Saari, 1974). Using the foot-in-the-door technique , the persuader gets a person to agree to bestow a small favor or to buy a small item, only to later request a larger favor or purchase of a bigger item. The foot-in-the-door technique was demonstrated in a study by Freedman and Fraser (1966) in which participants who agreed to post small sign in their yard or sign a petition were more likely to agree to put a large sign in their yard than people who declined the first request (Figure 3). Research on this technique also illustrates the principle of consistency (Cialdini, 2001): Our past behavior often directs our future behavior, and we have a desire to maintain consistency once we have a committed to a behavior.

A common application of foot-in-the-door is when teens ask their parents for a small permission (for example, extending curfew by a half hour) and then asking them for something larger. Having granted the smaller request increases the likelihood that parents will acquiesce with the later, larger request.

How would a store owner use the foot-in-the-door technique to sell you an expensive product? For example, say that you are buying the latest model smartphone, and the salesperson suggests you purchase the best data plan. You agree to this. The salesperson then suggests a bigger purchase—the three-year extended warranty. After agreeing to the smaller request, you are more likely to also agree to the larger request. You may have encountered this if you have bought a car. When salespeople realize that a buyer intends to purchase a certain model, they might try to get the customer to pay for many or most available options on the car.

Link to Learning

Read more about persuasion at The Noba Project website .

Think It Over

Describe a time when you or someone you know used the foot-in-the-door technique to gain someone’s compliance.

attribution

Modification and adaptation, addition of link to learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

Attitudes and Persuasion. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/12-3-attitudes-and-persuasion . License: CC BY: Attribution . License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

process of changing our attitude toward something based on some form of communication

logic-driven arguments using data and facts to convince people of an argument’s worthiness

one person persuades another person; an indirect route that relies on association of peripheral cues (such as positive emotions and celebrity endorsement) to associate positivity with a message

persuasion of one person by another person, encouraging a person to agree to a small favor, or to buy a small item, only to later request a larger favor or purchase of a larger item

Introduction to Psychology Copyright © by Utah Tech University Psychology Department is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

The Psychology of Persuasion: Persuasion Techniques Essay

Persuasion techniques are the tools a person uses to influence others to do according to his/her wishes. There are many persuasion tools such as consistency, authority, social proof, and reciprocation. Authority is used to influence when the person at a higher position of power demands obedience from the subjects. Obedience to authority becomes enough justification or motivation to act against our good judgment. The ‘Compliance professionals’ use appearance of authority to influence us to obey them or do their wishes. They adopt titles, clothes, and trappings of authority like tone of voice, language, elegant automobiles, and pieces of jewelry among others.

The appearance of authority was used on me a few years ago. One could have thought I was smart enough to see through this, but con artists are also smarter and catch us by surprise. I went to deposit my college fees in one of the bank’s local branches in our small town. The bank is usually crowded especially at the end month. I was not to report to school for another month but, my parent insisted I do so since we had already budgeted for it. There was a long queue ahead of me since the ATMs weren’t working for the second day due to cable problems where sewerage pipes were being repaired. I choose to sit on the bench as I waited for my turn to be served.

Out of nowhere, an elegantly dressed gentleman excused himself and sat down beside me. He started a friendly conversation and we both began to complain about the long queues. He asked me whether I always banked there and I told him I was just depositing my college fees and since I can’t travel with cash I had to wait. Taking the cue he told me he was a CEO with a computer technology firm in the city which surprised and left me wondering what he was doing in a bank in the small town. He could read my mind and he conspiratorially told me he had around 50,000 dollars in his persona which he wanted to deposit. He then proceeded to tell me the source of the money. It was an investment scheme in town were as he explained was very profitable. An investment of any amount doubled within three months and if reinvested back one could fetch thrice the amount in just since months. He continued to tell me that as an experienced businessman, he knew a good investment and the scheme was good and insisted I should try. Obedience to authority has practical advantages for those obeying. In the case of business figures, their positions allow them to have superior access to information and power and it is sensible for the subjects to believe them and so I told myself he knew what he was talking about.

After some time he offered to buy me a cup of coffee in a café next door to while the time away while the queue moves. In the café, they supposedly met with the manager of the scheme and after the small talk, they launched on the virtues of the scheme. Due to curiosity, I went along with them as they took me to the scheme’s offices. There were long queues too of people supposed to be depositing their money which they called ‘planting’ and another for those withdrawing which again was called ‘harvesting’. A smartly dressed lady came from the head of the harvesting queue directly to me and told me that she had just harvested after six months of investing. Some things struck me odd such as the absence of the usual security guards as common in most organizations in town. I also questioned the wisdom of customers carrying with them a lot of cash; couldn’t they just make transactions in their banks? And again the interest rate of investments was too high to be real. I excused myself and left the premises. Later on after inquiry I learnt that it was a pyramid scheme and my friendly gentleman was another con artist used by the scheme together with the supposedly manager.

The scheme was later discovered by the authorities a few months later and before they could be arrested they had conned people all over the country millions of dollars. People could not believe that they had just lost their money so easily, they just did not stop to ask questions but that is the use of authority in persuasion. Authority produces an automatic behavior. When we realize that obedience produces rewards and disobedience punishment we do not stop to think, rather, we tune ourselves to convenience of automatic compliance and therefore mechanical character. This, in most cases produce desirable results but, in other cases undesirable results. It was hard to imagine I could have my college fees to a bogus scheme due to well presented conartists as many people had.

Persuasion techniques are the tools a person uses to influence others to do according to his/her wishes. Obedience to authority becomes enough justification or motivation to act against our good judgment. We can resist this by removing the element of surprise. This is by being aware of authority power and that it can be unreal. The ‘compliance professionals’ expects us to be deferent to them. They will be surprised if we ask questions and become cautious of them which can put them of guard but this can protect us from their con games.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, November 24). The Psychology of Persuasion: Persuasion Techniques. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-psychology-of-persuasion-persuasion-techniques/

"The Psychology of Persuasion: Persuasion Techniques." IvyPanda , 24 Nov. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/the-psychology-of-persuasion-persuasion-techniques/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'The Psychology of Persuasion: Persuasion Techniques'. 24 November.

IvyPanda . 2021. "The Psychology of Persuasion: Persuasion Techniques." November 24, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-psychology-of-persuasion-persuasion-techniques/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Psychology of Persuasion: Persuasion Techniques." November 24, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-psychology-of-persuasion-persuasion-techniques/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Psychology of Persuasion: Persuasion Techniques." November 24, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-psychology-of-persuasion-persuasion-techniques/.

- Waiting Times and Formation of Queues in Banks

- Stacks, Queues, and Search Algorithms in Programming

- Proxemics: Four Distances During Communication

- Solution of Patient’s Queues Problem

- The Negative Impact of Soil Pollution

- Banking System: The Brief Analysis

- Deviant Behavior in the Public Space

- The Effects of Stimulus Checks on the Economy

- The Movement of Funds Through the Economy

- Money Laundering Scene in Police Drama "Ozark"

- An Audit of the Accessibility of the College of the North Atlantic-Qatar to Individuals With Physical Disabilities

- Motivational Speaking: Types of Motivators

- The Influence of Nature and Nurture on Human Behavior

- Pain Management Through Psychology

- The Nocebo Effect: Term Definition

Persuasion Techniques: Master the Art of Influencing Others

Have you ever wondered how some people are able to effortlessly sway others to their way of thinking? It’s not magic, but rather a skill that can be learned and mastered. In this article, I’ll delve into the fascinating world of persuasion techniques and explore the strategies behind effectively influencing others.

At its core, persuasion is about understanding human psychology and using that knowledge to convince others to take a specific action or adopt a particular viewpoint. Whether you’re in sales, leadership, or simply aiming to improve your communication skills, knowing how to employ persuasive techniques can give you a significant advantage.

Throughout history, great leaders and influential individuals have harnessed the power of persuasion to rally support for their causes. From ancient philosophers like Aristotle to modern-day marketing experts, countless theories and tactics have been developed. Join me as we uncover the secrets behind these techniques and discover how they can be applied in various aspects of our lives.

So sit back, buckle up, and get ready for an enlightening journey into the art of persuasion. We’ll explore key concepts such as building rapport, appealing to emotions, utilizing social proof, and much more. By the end of this article, you’ll have a toolbox full of effective persuasion techniques that will help you navigate any situation with confidence and influence those around you positively.

Understanding Persuasion Techniques

Let’s delve into the intriguing world of persuasion techniques. In this section, we’ll explore the various strategies that individuals use to influence others and achieve their desired outcomes. By understanding these techniques, you can become more aware of when they are being used on you and even employ them yourself in ethical ways.

- Reciprocity : One powerful persuasion technique is reciprocity – the idea that if someone does something for us, we feel obligated to return the favor. For example, imagine a friend offers to help you move apartments. You’d likely feel compelled to assist them with a future task. This principle works because humans have an innate desire for fairness and balance in relationships.

- Social Proof : Humans tend to follow the crowd and seek validation from others. That’s where social proof comes into play as a persuasive tool. Think about how often you make decisions based on online reviews or recommendations from friends. When we see evidence that others have chosen a particular option or behavior, it becomes easier for us to justify adopting it ourselves.

- Scarcity : Have you ever noticed how our desire for something intensifies if it’s scarce? The scarcity principle states that people perceive limited availability as valuable and desirable. Advertisers often use this technique by highlighting exclusive deals or limited-time offers to create a sense of urgency and push us towards making quick decisions before missing out.

- Authority : People naturally tend to trust those who appear knowledgeable and credible in their field of expertise. This is why authority figures like doctors, experts, or celebrities are frequently used in advertising campaigns as endorsers or spokespeople. Their association with a product or service lends credibility and influences our decision-making process.

- Consistency : We humans have an inherent need to be consistent with our beliefs, attitudes, and actions over time. Persuaders leverage this tendency by getting us to commit verbally or in writing to certain ideas or goals. Once we make a public commitment, we feel compelled to follow through to remain true to ourselves and maintain a consistent self-image.

Understanding these persuasion techniques is crucial for navigating the complex world of influence. By being aware of these strategies, you can better evaluate the messages and appeals that come your way, making more informed decisions based on your own values and needs. So next time you find yourself in a persuasive situation, keep an eye out for reciprocity, social proof, scarcity, authority, and consistency at play.

Remember, knowledge is power when it comes to persuasion techniques. Stay curious and observant as you navigate the fascinating realm of human influence!

Building Rapport with Your Audience

When it comes to effective persuasion techniques, one key aspect that should never be overlooked is building rapport with your audience. Establishing a connection and fostering trust can significantly enhance your ability to influence others. In this section, we’ll explore some strategies on how to build rapport and create a strong bond with your audience.

- Show genuine interest : People appreciate when you show sincere interest in them. Take the time to listen actively, ask thoughtful questions, and demonstrate that you value their perspective. By doing so, you not only make them feel important but also establish yourself as someone who cares about their needs and wants.

- Mirror body language : Non-verbal cues play a crucial role in communication. Mirroring the body language of your audience can help create an unconscious sense of familiarity and harmony between you. Pay attention to their posture, gestures, and facial expressions, and subtly align yours accordingly. This subtle mirroring can enhance the sense of connection between you.

- Use inclusive language : An effective way to build rapport is by using inclusive language that makes your audience feel involved and valued. Instead of focusing solely on yourself or using detached pronouns like “I” or “you,” opt for more inclusive words like “we” or “us.” This simple shift in language can foster a sense of unity and shared goals.

- Empathize with their experiences : To truly connect with your audience, put yourself in their shoes and understand their experiences, challenges, and emotions. Show empathy by acknowledging their feelings without judgment or criticism. By demonstrating understanding, you create a safe space for dialogue where they are more likely to open up to your ideas.

5.Support common interests: Finding common ground is an excellent way to create rapport quickly. Identify shared interests or values between yourself and your audience members, whether it’s a hobby, passion for a cause or industry-related knowledge. Highlighting these commonalities can help establish a sense of camaraderie and build trust.

Remember, building rapport with your audience is an ongoing process that requires genuine effort and attention. By employing these techniques, you can create a strong bond that enhances your persuasive abilities and paves the way for meaningful connections.

Utilizing the Power of Social Proof

When it comes to persuasion techniques, one powerful tool that can greatly influence our decision-making is social proof. Social proof is the idea that people tend to look to others for guidance on how to behave or what choices to make. We often assume that if others are doing something, it must be the right thing to do.

Here are a few examples of how social proof can be utilized effectively:

- Testimonials and Reviews: When we see positive reviews or testimonials from satisfied customers, it creates a sense of trust and reassurance. Knowing that others have had a positive experience with a product or service increases our confidence in making a similar purchase.

- Celebrity Endorsements: Many companies leverage the power of celebrity endorsements because they know that seeing someone famous using their product or supporting their cause can sway consumer opinions and influence buying decisions.

- User-generated Content: The rise of social media has given individuals the ability to share their experiences and opinions with a wide audience. Brands often encourage users to generate content related to their products or services, as this user-generated content serves as social proof and builds credibility.

- Influencer Marketing: Influencers have become an integral part of marketing strategies in recent years. By partnering with influencers who have large followings on platforms like Instagram, YouTube, or TikTok, brands tap into their influence over their audience’s purchasing behaviors.

- Popularity Indicators: Showing numbers such as “10 million sold” or “bestseller” can create a perception of popularity and desirability around a product or service. This information acts as social proof by suggesting that many other people have already made the same choice.

Social proof taps into our innate desire for belongingness and conformity; we naturally feel more comfortable aligning ourselves with the actions and preferences of others rather than being outliers in society.