How to go to Heaven

How to get right with god.

What is the documentary hypothesis?

For further study, related articles, subscribe to the, question of the week.

Get our Question of the Week delivered right to your inbox!

The documentary hypothesis – What is it?

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

10 The Documentary Hypothesis

Baruch J. Schwartz holds the J. L. Magnes Chair in Biblical Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Published: 12 May 2021

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The Documentary Hypothesis was the most influential and widespread theory of the composition of the Pentateuch for most of the twentieth century. This essay examines the literary indicators that underlie the Documentary Hypothesis, the development of the theory, and its salient claims and features.

This chapter deals with the theory that four pre-existing, independent literary works, referred to as sources or documents, were combined to form the canonical Torah: the theory known as the Documentary Hypothesis. The discussion is confined to the literary evidence leading to the realization that the Torah is the work of more than one author, the grounds for the four-source hypothesis, the overall character of the sources themselves, and the manner in which they appear to have been combined. How the sources came into existence and the historical circumstances that gave rise to their ultimately being combined are not discussed, nor is a detailed description of each source provided. The role of the Documentary Hypothesis within Biblical scholarship and the different forms it has assumed over the centuries are also beyond the scope of the discussion. 1

The Documentary Hypothesis, long considered to be the standard explanation for the formation of the Torah and still accepted by many scholars, is grounded not in any scholarly desire to discover multiple sources in the text, but on the existence of literary phenomena for which the most economical and convincing explanation is that the Torah is not a unified text, but is rather the product of multiple authorial and editorial hands. The indications that the Torah is a composite literary work may be classified into four types: redundancy, contradiction, discontinuity, and inconsistency of terminology and style. Three of these—redundancy, contradiction and linguistic inconsistency—are found both in the narrative and in the legal portions of the Torah; the fourth, discontinuity, is found principally in the narrative sections. As one might expect, there is some overlap between these categories, and in many cases a single discrepancy may fall into more than one of them. Still it is essential to distinguish the four phenomena from one another in order to gain a proper understanding of their contours and their import.

A case of redundancy in the Torah is essentially an instance of unexplained and unwarranted repetition of what has already been said. In the narrative portions of the Torah, redundancy is present whenever each of two or more passages purports to provide the one and only account of an event that can logically have occurred only once. In the legal sections of the Torah, redundancy is a case in which two or more passages purport to provide the legal stipulation that is to be fulfilled in a given, uniquely defined situation.

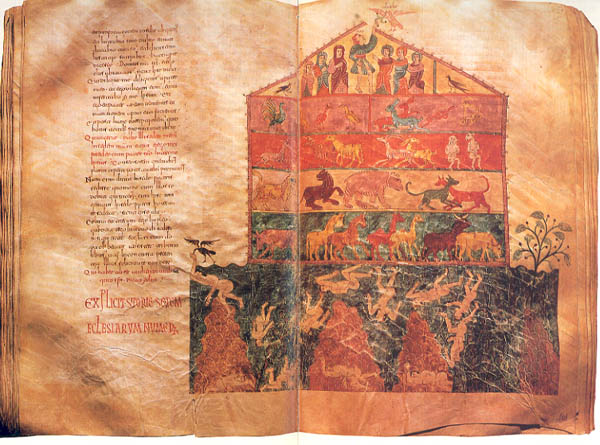

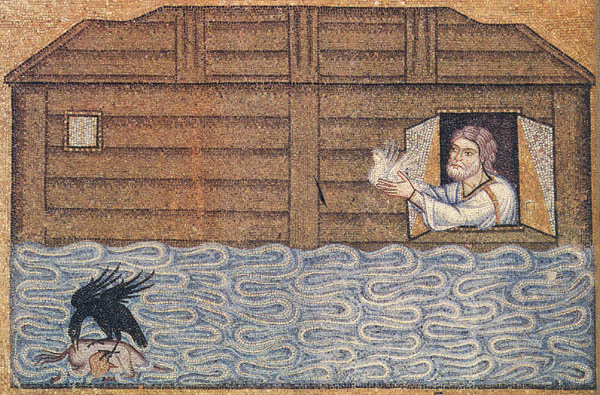

This phenomenon is extremely widespread. The creation of the cosmos, of humans, and of animals is described twice (Gen 1:1–2:4a and 2:4b–25); the establishment of the covenant with Abraham is recounted twice (Gen 15:1–21 and 17:1–27); the changing of Jacob’s name to Israel is related twice (Gen 32:28–29 and 35:9–10); the divine name, Yahweh, is revealed to Moses twice (Exod 3:13–15 and 6:2–9), among many others. Redundancy is also rife within individual narratives. For example, in the course of the story of the flood (Gen 6:5–9:17), the narrator twice describes the evil that spurred Yahweh’s decision to bring about the flood (Gen 6:5–6 and 6:11–12); we read twice that Yahweh informed Noah of his decision (6:17 and 7:4); twice we learn that he conveyed his instructions to Noah (6:18–21 and 7:1–3), and more. In the course of the account of Moses’s commissioning (Exod 3:1–4:17), Yahweh twice mentions that he has seen the affliction of his people and has decided to act (3:7–8 and 3:9); Moses twice expresses his objections to having the task imposed upon him (3:11, 13 and 4:1, 10, 13); twice Yahweh responds to his reservations (3:12, 14–15 and 4:2–9, 11–12, 14–16), and so forth. In all these cases and innumerable others, the individual passages provide no recognition that the event itself has already transpired or that it might not be the only such event. Every such narrative, and every similarly duplicated subsection of a repetitive narrative text, presents itself as the one and only account of the event described, as does its counterpart.

Turning to the legal portions of the Torah: twice the Israelites are commanded with regard to permitted and forbidden foods (Lev 11 and Deut 14:3–21), the prohibition of usury (Lev 25:35–37 and Deut 23:20–21), the sustenance of the poor from the produce of one’s field and vineyard (Lev 19:9–10 and Deut 24:19–21), the sabbatical year (Exod 23:10–11 and Lev 25:1–7, 20–22), and more. Three times they are given the laws pertaining to the manumission of slaves (Exod 21:1–11, Lev 25:39–46 and Deut 15:12–18), talionic restitution (Exod 21:22–25, Lev 24:17–22, and Deut 19:21), murder, manslaughter and asylum (Exod 21:12–13, Num 35:9–34, and Deut 19:1–13), and more. They are commanded with regard to the annual festivals four times (Exod 23:14–19, Exod 34:18–26, Lev 23:1–44, Deut 16:1–17; an additional section in Num 28–29, dedicated to the unique sacrifices offered on each festival day, complements the law in Lev 23). Just as in the narrative portions of the Torah, each of these passages is always presented as the sole and complete account of the legislation that it claims to convey, never as an addendum, continuation, or even emphatic reiteration of one or more of its counterparts. They thus compete with one another for the status of the authoritative promulgation of the command in question (see Deut 4:2, 13:1). Furthermore, these competing passages appear in completely different places in the Torah—a fact that cannot be explained reasonably under the assumption that the Torah is a unified work.

Not every case of formal or substantive similarity should be mistaken for redundancy. A single storyteller may recount two similar episodes, if he maintains that they both occurred and there is no categorical impossibility for this to have been so. For example, even if Abram’s wife Sarai was abducted by Pharaoh (Gen 12:10–20), she may also have been abducted later by Abimelech (Gen 20:1–18), and Isaac’s wife Rebecca may have subsequently been abducted by Abimelech as well (26:6–11) since, despite the similarity, the three accounts do not purport to be reports of a single event. Only mutually exclusive competition between two accounts constitutes redundancy.

The most conspicuous and serious instance of redundancy is not limited to two or three competing passages but is woven through the entire Torah. This is the account of how Israel received its laws. The story of the proclamation of the Decalogue and the establishment of a covenant at Horeb (Exod 19:2b–9a, 16aα2–17, 19; 20—23; 24:3–8, 11bβ–15a; 32:1–8, 10–25, 30–35; 33:6–11; 34:1, 4, 28) relates that the laws were written down and that the covenant that Yahweh made with the Israelites was concluded “on the basis of these words” (Exod 24:8), i.e. the written text of the laws. With regard to these laws the people said: “All that Yahweh has spoken (i.e. Exod 20:19–23:33) we will faithfully do” (Exod 24:7), and the story concludes with no expectation of additional laws to be given at some future time. This account thus purports to be the sole report of the lawgiving. Nonetheless, the reader is also presented with a second story of a covenant made at the same time, in the course of which Moses ascended a mountain—Sinai, according to this account—to hear the attributes of Yahweh’s mercy (Exod 19:9b–16aα1, 18, 20–25; 24:1–2, 9–11bα; 32:9, 26–29; 33:1–5, 12–23; 34:2–3, 5–27). Here too, a corpus of laws is given to Moses (Exod 34:11–26), he is commanded to record them in writing, and it is they that are referred to in the statement: “In accordance with these words I have made a covenant with you and with Israel” (Exod 34:27). This second account shows no signs of continuing, adding to, affirming, replacing, or denying the first; it too is presented as the one and only story of the conclusion of a covenant between Yahweh and Israel, in the course of which Yahweh conveyed his laws to Moses.

Interspersed between these two stories and extending over the long text that follows, a third account emerges, according to which Moses is told that the lawgiving will commence only after Yahweh’s portable dwelling, the tabernacle, has been constructed at the foot of Mount Sinai. Only then, by means of divine speech emanating from between the cherubim on the cover of the ark, will Yahweh communicate to Moses “all that I will command you concerning the Israelite people” (Exod 25:22). This plan too is then carried out exactly as promised (see Schwartz 1996a ). Just as neither of the other two stories offers any intimation that the legislation it contains is only part of a larger body of laws and that more legislation will follow, this third story contains no indication that the legislation it contains (which extends throughout Leviticus and Numbers) is intended to supplement what preceded. All three accounts ignore each other’s existence entirely, and the author of one cannot be the author of either of the other two.

The same goes for the account of the lawgiving given in Moses’s second valedictory oration. Moses affirms (Deut 5:19–6:3) that the full body of Yahweh’s commandments was given to him at Horeb “on the day of the Assembly” (Deut 9:10; 10:4; 18:16), that is, on the same day that the Decalogue was proclaimed for the entire Israelite people to hear, but he goes on to relate that he did not convey this legislation to the people at the time but has rather kept it to himself until the present, four decades later (see Weinfeld 1991 , 236–327; Nelson 2002 , 73–85; Vogt 2006 , 113–159). This thus constitutes a fourth independent and complete report of how and when Yahweh’s laws were conveyed to the Israelites.

Not only do we possess four independent accounts of the time, manner, and location of the lawgiving, each alleging to be the only such account, but each of the four also includes its own version of the laws themselves, each version purporting to be the laws and statutes commanded by Yahweh through the agency of Moses. The existence of four mutually ignorant legal corpora on the one hand, and of four mutually exclusive stories functioning as distinct narrative frameworks for them on the other, is incontrovertible evidence that the writings of several authors have been incorporated in the Torah.

Contradictions

Competing reports of a single event that cannot logically be deemed to have occurred more than once should not be understood as the work of a single author precisely because they are set side by side in a single literary work without explanation; so too the numerous contradictions that appear in the Torah cannot be the work of a single hand. Defined precisely, a contradiction in the narrative portion of the Torah is an instance in which incompatible factual claims are made with regard to an event that can only have occurred once. For instance, it emerges from several passages in the story of Abraham that the patriarch’s birthplace is Aram-naharaim (Gen 24:4, 10). Yet in other equally explicit passages, it is asserted that he originated from Ur of the Chaldeans (e.g. Gen 15:7). These are not two names for one place, and one person cannot have two countries of origin; this is therefore a blatant contradiction. Similarly, in the story of the men sent by Moses to explore the land of Canaan (Num 13–14), it is expressly stated that Caleb was the only one of the scouts to dissent from the negative report given by the rest of the delegation (13:30; cf. 14:24), but it is stated no less explicitly that both Caleb and Joshua dissented (14:6–9). These two claims are irreconcilable. Was Noah commanded to take two of each animal aboard the ark, or only two of each impure animal and seven pairs of each pure species? Taken at its word, the Torah provides no unequivocal answer to this question, since both claims are made unambiguously (Gen 6:19–20; 7:9 vs. 7:2–3, 8; see Schwartz 2007 , 147).

In a certain sense, all instances of redundancy in the Torah are also contradictions, since whenever we encounter two or more reports of a single event there are also irreconcilable discrepancies between them. Was the human race created “male and female” simultaneously and at the end of the process of creation, as stated in the first account of Creation (Gen 1:27; 5:2), or was woman created after man, from one of his ribs, at the beginning of the process, as related in the second story (2:21–25)? Here too the Torah relates two contradictory events and makes no effort to resolve them. Another example: when Moses received the laws from Yahweh, did he present them to the people immediately, as stated in the account of the covenant at Horeb (Exod 24:3)? Or did he keep them to himself for forty years and disclose them to the Israelites only just prior to his death, as he claims in Deuteronomy (Deut 4:14; 5:19–6:3; 11:32–12:1)? In these instances and in many others (see e.g. Schwartz 2012 ), repetition and contradiction intersect. The contradictions are to be found in the particulars of the repeated accounts, so that two competing narratives serving only one narrative purpose contradict each other at every turn.

One particularly well-known example of contradiction in the narrative portion of the Torah is that concerning the name of Israel’s deity, Yahweh. When biblical scholarship was still in its infancy, early critics noticed that among the many events that are inexplicably reported twice are several in which the two reports refer to the deity differently, both in the quoted speech of the characters and in the narrator’s own words, with one version using the generic noun Elohim (“god” or “God”), with or without the definite article, and the other using the tetragrammaton, Yahweh. At first, some critics imagined that this issue was simply a matter of differing style, and as such could be used, like other stylistic peculiarities, to distinguish between two different narrators, with each presumed to have had a preference for one or another of the two divine appellations. Occasionally even later critics have continued, erroneously, to assume this. However, as has become abundantly clear over time, these separate sets of narratives differ not on a matter of nomenclature or terminology but rather on a point of historical fact : the twofold question of when in history the tetragrammaton was revealed and to whom. One set of stories maintains unambiguously that the name Yahweh was known to all of humanity and was in common use throughout humankind since the beginning of time (Gen 4:1, 26), while according to another it is equally undisputed that this name was completely unknown until the lifetime of Moses, when it was first revealed, and even then only to him, and through him, to the Israelites (Exod 3:13–15; 6:1–3). This is no stylistic inconsistency; it too, like the examples above, is a substantive contradiction in the storyline itself. In this case, the contradiction is not localized within two identifiable, conflicting passages, but is rather spread out over numerous episodes, where entire narrative threads reflect conflicting historical assumptions.

The contradictions in the legal portion of the Torah are just as numerous and just as irreconcilable. The following are but a few examples. The command in Exodus states emphatically that the pesaḥ ritual must be performed with a sheep or a goat and that the animal’s flesh must be roasted rather than boiled or eaten uncooked (Exod 12:3–5, 8–9), but the corresponding command in Deuteronomy includes cattle among the animals that may be sacrificed and specifies that the flesh is in fact to be boiled (Deut 16:2, 7). Two legal passages mandate that Hebrew slaves be freed after six years of service (Exod 21:2; Deut 15:12–18), while a third stipulates that they be freed only in the Jubilee year (Lev 25:39–43). In Deuteronomy we read that the harvest pilgrimage, sukkôt , lasts only seven days (Deut 16:13–15); Leviticus and Numbers mandate an eighth day (Lev 23:33–36; Num 29:35–38). The law in Leviticus permits the slaughter of sheep and cattle for sacrificial offerings only, ruling out the non-sacrificial consumption of the flesh of these quadrupeds as an eternal, unchanging statute (Lev 17:3–7); Deuteronomy stipulates that after reaching Canaan, the Israelites will be permitted to slaughter sheep and cattle non-sacrificially and consume their flesh with impunity (Deut 12:15, 20–22; see Schwartz 1996b ; Chavel 2012).

In the most blatant case of contradiction in the narrative portion of the Torah, which is of course the aforementioned existence of mutually exclusive and conflicting accounts of how Israel received Yahweh’s laws, with each account enumerating the laws that its author maintains were given, narrative and legal inconsistency reach their crucial point of intersection. Each narrator claims that the laws that he cites, and they alone, constitute the legislation imparted by Yahweh to Israel through Moses. It follows that every case of contradiction between laws is also a narrative contradiction , with one narrator claiming that, in the course of historical time, Yahweh commanded something, with another claiming that he commanded precisely the opposite.

Discontinuity

Although the question of literary flow is at times significant even in legal passages, discontinuity is most apparent in the narrative portions of the Torah. Yet it should be stressed from the outset that even in narrative, not every digression from the main plotline constitutes evidence of multiple authorship. Literary techniques such as parenthesis, flashback, tangential expansion, internal monologue, simultaneity, summary, recapitulation, editorializing, cross-reference, elaboration, and resumptive repetition (Kuhl 1952 ; Talmon 1978 ), which can be found in all literature, are among the recognized hallmarks of biblical prose and do not serve as indications of multiple authorship or strata of redaction. In fact, as the most basic tools of the biblical narrator, they can and should be seen as evidence of literary unity. They embody authorial planning, logic, and intentionality; they can be discerned with common literary-critical tools and their function in crafting the story’s form and meaning is apparent to the trained reader. The discontinuities that serve as evidence for the composite nature of the Torah are of an entirely different sort. They are cases in which the thread of narration is first cut off, as if in mid-air, and what follows appears to be unconnected, often contradicting or needlessly repeating what preceded it, reporting another event whose relationship to the first is unclear, drawing on assumptions that are at odds with those of the initial story and incomprehensible as its natural continuation, and then, at some later point in the text, the thread of the first narrative picks up exactly where it left off.

The phenomenon can be illustrated through an attempt to make sense of the account of the plague of blood reported to have struck the Egyptians (Exod 7:14–25; for the analysis, cf. Greenberg 1972 , 65–75). The story begins with Yahweh’s instructions to Moses:

14 And Yahweh said to Moses, “Pharaoh’s heart is heavy; he has refused to let the people go. 15 Go to Pharaoh in the morning, as he is coming out to the water, and station yourself before him at the edge of the Nile, taking with you the rod that turned into a snake. 16 Say to him, ‘Yahweh, the God of the Hebrews, sent me to you to say, “Let My people go that they may worship Me in the wilderness,” but you have paid no heed until now. 17 Thus says Yahweh, “By this you shall know that I am Yahweh.” See, I shall strike the water in the Nile with the rod that is in my hand, and it will be turned into blood, 18 and the fish in the Nile will die. The Nile will stink so that the Egyptians will find it impossible to drink the water of the Nile.’”

With these instructions given clearly and unambiguously, it stands to reason that the reader will next be informed of their prompt implementation. However, at this point, inexplicably, we are met by another set of instructions, clearly and unambiguously contradicting the first:

19 And Yahweh said to Moses, “Say to Aaron: Take your rod and hold out your arm over the waters of Egypt—its rivers, its canals, its ponds, all its bodies of water—that they may become blood; there shall be blood throughout the land of Egypt, even in vessels of wood and stone.”

According to these new instructions, Moses is not to confront Pharaoh or to threaten him with the approaching plague. Rather, Aaron is to be ordered to bring about the plague with his own rod, not Moses with his, whereupon not only the water in the Nile but all of the water in Egypt, including that stored in vessels (see Targum Onqelos, Rashi, and ibn Ezra), will become blood. Did Yahweh change his mind? If so, why? If not, what is the purpose of the second set of instructions, and why is it not stated in the text? The Torah passes over these questions in silence.

After the two sets of instructions, we read of their implementation:

21aα1 Moses and Aaron did so, just as Yahweh commanded.

But Yahweh issued two contradictory commands. Which did they follow?

21aα2–b He lifted up the rod and struck the water in the Nile in the sight of Pharaoh and his courtiers, and all the water in the Nile was turned into blood, 21a and the fish in the Nile died. The Nile stank so that the Egyptians could not drink water from the Nile.

How is one to explain the transition from the first part of verse 20, which speaks in the plural of Moses and Aaron, and the remainder, which speaks in the singular (“he lifted up”)? Who is the subject of the second part of the verse, carrying out the instructions? Apparently Moses, because it seems to be the initial instructions, in which he was told to lift his own rod, that are being carried out. The precise phrasing of the initial instructions is even echoed in this report of what transpired. But if so, what of the second instructions? Why were they issued? Furthermore, how did Moses and Aaron know which of the two sets of directives to carry out?

The text of the Torah answers none of these questions, but it does state the outcome of the event:

21b The blood was throughout the land of Egypt.

This statement conforms to the second set of instructions, but has nothing to do with the first. If there was indeed blood “throughout the land of Egypt,” exactly as predicted in the second set of instructions, why does the beginning of the verse single out the water in the Nile? Here is a case of discontinuity within a single verse. This problem too is left unaddressed.

The Torah describes Pharaoh’s reaction to the plague thus:

22b Pharaoh’s heart stiffened and he did not heed them, as Yahweh had spoken.

As set forth in the prologue to the plague story (Exod 7:1–7), Yahweh resolved in advance that, in order to maximize the number of signs and wonders in his impending display of might, he would “harden Pharaoh’s heart” (7:3), that is, embolden him, so that he would overcome his dread (cf. Deut 2:30) and refuse to submit to Moses’s and Aaron’s demand to free the Israelites. As the story develops, and as is repeated in its concluding summary (11:9–10), this intent is carried out to the letter, and the description of Pharaoh’s reaction to the blood here is fully consistent with the plan. Pharaoh becomes over-confident, his impaired judgment inducing him to pay no heed to Moses and Aaron, precisely as was announced in advance and just as he does repeatedly throughout the story (8:15; 9:12, 35; 10:20, 27).

However, immediately following this statement, we hear of another response to the plague of blood, first on the part of Pharaoh and then on the part of the populace.

23 Pharaoh turned and went into his palace, paying no regard even to this. 24 And all the Egyptians had to dig round about the Nile for drinking water, because they could not drink the water of the Nile.

This passage proceeds from the assumption that only in the Nile has the water turned to blood while the water found elsewhere in Egypt has remained potable. The Egyptians therefore dig in surrounding areas, where they indeed find drinking water. As for Pharaoh himself, he is utterly unaffected; he simply returns home where, presumably, he has drinking water stored away or will have it brought to him by his courtiers from locations other than the Nile. This clearly reflects the plague of blood as it was foretold in vv. 17–18 and as it is said to have transpired in vv. 20aα2–21a: only the water in the Nile has turned to blood. But it is quite the opposite of what was announced in v. 19 and described in v. 21b, according to which all of the water in Egypt—including any water one may have stored away—was turned to blood. Moreover it is incompatible with the preceding v. 22b—yet another example of discontinuity between immediately adjacent verses—since it relates that Pharaoh’s behavior, rather than being the work of Yahweh, is the result of conscious, deliberate, and impeccable reasoning on his own part. Pharaoh here is sovereign, autonomous, and eminently logical; it is he who decides to pay no mind to what has occurred, since there is other potable water nearby and his servants will surely obtain it for him. How can one harmonize these two mutually exclusive reactions to the bloodied waters? The text, again, is silent.

Finally, how did the plague of blood finally come to an end? The first answer is implied in what precedes the notice of Pharaoh’s reaction:

22a The Egyptian magicians did the same with their spells.

If Pharaoh’s magicians were able precisely to replicate the action performed by Moses and Aaron, that is, to turn the water to blood, it follows that the blood must have turned back to water in the meantime. The miraculous event was of momentary duration: Moses and Aaron transformed the water to blood; it soon became water again. Afterward, the magicians performed exactly the same feat, and the water again returned to its normal state.

This picture is belied, however, by the concluding verse of the passage, which leads directly to the account of the next plague, that of frogs:

25 When seven days had passed after Yahweh struck the Nile…

Here it would seem that after a week had elapsed from the moment the Nile—and only the Nile—was turned to blood, the next plague simply commenced, without any specific action being taken to repair the state of the Nile. Evidently the natural flow of the great waterway gradually replaced all the blood with fresh water, and this brought the episode to its close. After a week, all was forgotten, necessitating the infliction of another plague.

The contradiction between these two distinct denouements is unmistakable; one or the other may be said to have occurred, but not both. More important, each separate denouement aligns with the assumptions of one or another description of the plague itself. The narrator who confined the blood to the Nile relates that the bloody water was gradually washed away and that meanwhile it was necessary, and possible, to obtain water elsewhere, and the narrator who maintained that all the water in Egypt became undrinkable indicates that the plague lasted only a short while, which is why the Egyptians did not perish of thirst.

Terminology and Style

These twelve verses illustrate all of the three phenomena discussed above: repetition, contradiction, and discontinuity. In the course of examining them, a fourth phenomenon surfaces as well: unexplained variations in vocabulary and usage. Two different verbs are used to express what was done with the rod: “stretch out” (נטה—v. 19) and “lift up” (וירם—v. 20a1b); two distinct phrases refer to the action of turning the water into blood: “strike” (מכה, ויך, הכות—vv. 17, 20a1b, 25) and “do so” (ויעשו כן—vv. 20a1a, 22); two separate idioms express Pharaoh’s intransigence: his heart was “stiffened” (ויחזק—v. 22), which means he recklessly imperiled himself and his people, and his heart was “heavy” (כבד—v. 14), i.e. he willfully refused; two different terms are used for what actually happened to the water: it “turned into” blood (ויהפכו, ונהפכו—vv. 17, 20) and it “became” blood (והיה—v. 19); there are two different uses of the word יאור: to refer to the Nile (vv. 15, 17, 18, 20, 21, 24, 25) and to refer to any one of an unspecified number of streams or channels (v. 19). These stylistic inconsistencies do not render the text unintelligible as do the others, but their existence calls for explanation.

The Solution

The brief but baffling account of the plague of blood was introduced as a convenient means of illustrating the phenomenon of narrative discontinuity, but it has shown itself to exhibit each of the other literary indications of multiple authorship as well: competing, functionally equivalent components; mutually exclusive, contradictory reports of events and seemingly random terminological variation. A closer look at these irreconcilable discrepancies reveals precisely how they have arisen. The explanation emerges when the passages that compete with and contradict each other are viewed in separate columns.

First, the two sets of instructions:

On one side, in roman, we have Moses alone, who is told to threaten Pharaoh that he will strike the Nile only, with his own rod, and to accuse him of having paid no heed thus far. On the other side, in italics, we have Moses and Aaron, who are told to issue no threat but simply to act, using Aaron’s rod and affecting Egypt’s entire water supply.

Next, the two reports of the implementation of the instructions:

It is immediately apparent that the roman section not only corresponds to the roman section that precedes it; it is in fact its direct continuation. Moses lifts his rod and strikes the Nile only—note the verbal correspondences between command and fulfillment. And the same is true on the italic side: the implementation section is the direct continuation of the command section, echoing it fully.

Placing side by side the two competing reports of Pharaoh’s reaction to the blood and of the eventual outcome of the episode, we obtain identical results:

On the roman side, where Pharaoh is said simply to have withdrawn to his palace and both he and his subjects obtain water from sources other than the Nile, after which the plague gradually disappears, the text is without any doubt the direct sequel to the two roman sections preceding. On the italic side as well, where the magicians replicate Yahweh’s ominous act but Pharaoh is unable to respond rationally because Yahweh has instilled him with false courage, the words of the text follow directly upon the preceding italic section.

The moment the competing and contradicting passages are disentangled in their entirety, we have before us not one but two self-contained narratives:

Each of the two is a complete, continuous, internally consistent and literarily smooth account. Each is also consistent in its style and usage. While both tell of the miraculous transformation of the water to blood in the course of Moses’s confrontation with Pharaoh, and are therefore essentially two accounts of a single event, they differ greatly, not only in their form but in the specifics of the occurrences that they relate and in their theological and thematic content as well.

The conclusion is inescapable. The reason the account of the blood appearing in the canonical Torah is rife with contradictions, redundancies, and discontinuities is that it is in fact a combination of two accounts, a passage compiled from two texts that were originally independent and were ultimately fused into one—in the following manner:

14 Yahweh said to Moses, “Pharaoh’s heart is heavy; he refuses to let the people go. 15 Go to Pharaoh in the morning, as he is coming out to the water, and station yourself before him at the edge of the Nile, taking with you the rod that turned into a snake. 16 Say to him, ‘Yahweh, the God of the Hebrews, sent me to you to say, “Let My people go that they may worship Me in the wilderness,” but you have paid no heed until now. 17 Thus says Yahweh, “By this you shall know that I am Yahweh.” See, I shall strike the water in the Nile with the rod that is in my hand, and it will be turned into blood; 18 and the fish in the Nile will die. The Nile will stink so that the Egyptians will find it impossible to drink the water of the Nile.’” 19 Yahweh said to Moses, “Say to Aaron: Take your rod and hold out your arm over the waters of Egypt—its rivers, its canals, its ponds, all its bodies of water—that they may become blood; there shall be blood throughout the land of Egypt, even in vessels of wood and stone.” 20 Moses and Aaron did just as Yahweh commanded ; he lifted up the rod and struck the water in the Nile in the sight of Pharaoh and his courtiers, and all the water in the Nile was turned into blood, 21 and the fish in the Nile died. The Nile stank so that the Egyptians could not drink water from the Nile. The blood was throughout the land of Egypt . 22 But when the Egyptian magicians did the same with their spells, Pharaoh’s heart stiffened and he did not heed them, as Yahweh had spoken . 23 Pharaoh turned and went into his palace, paying no regard even to this. 24 And all the Egyptians had to dig round about the Nile for drinking water, because they could not drink the water of the Nile. 25 When seven days had passed after Yahweh struck the Nile…

The two have been woven together meticulously, strictly according to the dictates of chronology and logic. For instance, not only are the two sets of instructions placed first and only thereafter the two accounts of their implementation, the instructions that include the order that Moses “go to Pharaoh” and announce the impending plague before its onset precede those that begin with the command to instruct Aaron to perform the act immediately.

Most important, it appears that the compiled text rigidly preserves all of the words of each of the two accounts, in their original order, and without addition.

The Documentary Hypothesis

The results of this analysis of the account of the plague of blood are not the exception but the rule. When the same method is applied throughout the narrative portion of the Torah, time and again similar results are obtained. Whether within relatively brief passages such as this one or in passages extending over many chapters, it repeatedly becomes clear that independent narrative texts—not oral traditions, but complete written documents—have intentionally and ingeniously been woven together. This discovery is the key to understanding how the Torah was compiled, for pursuant to these findings it emerges that the same narrative threads are present over the course of the entire Torah ; that is, the threads that may be detected within a given passage are in fact the continuations of threads that are already intertwined prior to it. Each of the two accounts of the plague of blood, to return to the example presented above, is the continuation of a narrative thread that earlier told of the enslavement and oppression of the Israelites in Egypt, each of which in turn continues a narrative thread that recounted the descent of Jacob and his family into Egypt. Each of these is the continuation of one of the threads discernible in the accounts of creation, the flood, the lives of the patriarchs, and the exploits of Jacob and his children. After telling its version of the plague of blood, each thread continues immediately to tell of the remaining plagues inflicted on the Egyptians, each according to its own version of the story, and each of these in turn continues with its own account of the exodus from Egypt, the miracle at the sea, and the journey through the wilderness. These narrative threads thus once constituted separate, continuous, and coherent literary sources , which were subsequently combined, from beginning to end, in the way demonstrated by the brief example above: by painstakingly alternating from one document to another, faithfully preserving the precise text and order of each source to the fullest extent achievable, and with as little interference on the part of the compiler as possible.

While the text examined above resolved itself into precisely two narrative threads, the total number of sources interwoven throughout the Torah is not two or even three but four. Not all four are detectable at every point in the Torah, however, because the four sources do not relate all of the same events . A large number of events are told by one source only (e.g. the Tower of Babel, Gen 11:1–9, from J; the near-sacrifice of Isaac, Gen 22:1–13, from E; the building of the tabernacle, Exod 35–40, from P); when this is the case, the passage appearing in the Torah is remarkably coherent, free of internal contradiction, redundancy, and discontinuity. This is not surprising, since it is composed entirely of the words of a single narrator. Other events, described by two of the four sources, result either in doublets or in unintelligible passages like the one above, in which two differing accounts of a single event have been combined and in which literary chaos consequently reigns. There are also instances in which accounts from three of the sources have been combined in a single passage. These, however, are rare, since relatively few events are related by more than two of the Torah’s sources. The lengthier the section of text being examined, the more likely it is that a third source will eventually come into view. There are almost no passages that include all four sources, for the simple reason that one source, unlike the other three, does not appear intermittently throughout the Torah but is entirely contiguous, introduced in its entirety near the end of the other three interwoven threads, as we shall see.

This realization enables us to formulate a host of other questions. What is the nature of these four sources? When did they come into existence, and who created them? Exactly how, when, and why were they combined? Biblical scholarship has devoted itself to the study of these issues since they first presented themselves. The discovery of the precise number of sources—four, their disentanglement from one another and the concomitant reconstruction of each source or what remains of it, the appreciation of the unique version of Israel’s pre-history told by each one, and the characterization of each source’s unique content, language, worldview, and historical background has been a complex process. It began toward the end of the eighteenth century, reached a peak at the end of the nineteenth, and became increasingly refined in the first half of the twentieth. The stages of this process and its central findings and accomplishments have been studied by many scholars and have been presented in great detail numerous times, and for that reason we will not review them again here (see Nicholson 1998 ; Arnold 2003 ; Baker 2003 ). Nevertheless, two factors that played a central role in the discovery process do require elaboration. The first is the question of the use of the name Yahweh, the tetragrammaton, to refer to the Israelite deity. As noted, according to one entire group of narratives in the Torah, the name Yahweh was known to all of humankind from the very beginning of time, while according to another group of narratives, it was revealed only in the time of Moses, and even then, at first, only to the Israelites. When, with the advent of modern scholarship, it was first suggested that the texts in each of the two groups combine to form separate narrative sequences (Astruc 1753 ), this was one of the first intimations that the Torah in its entirety might have been compiled from preexisting literary sources of considerable scope and completeness. But biblical scholarship did not arrive at this conclusion in one leap. At first, critics assumed that since the Torah reflects two opposing views regarding the tetragrammaton, the Torah must be comprised of two sources, one “Yahwistic,” after its widespread use of the name Yahweh when referring to Israel’s deity, and thus designated by scholars as “J” in keeping with the German spelling “ Jahwe ,” and one “Elohistic” for its use of the general term for God, Elohim , when relating events that occurred, according to this source’s reconstruction of history, before the name Yahweh was disclosed, and designated in scholarship as “E.” Only much later was it realized that while the Yahwistic stories do indeed merge into what appears to have been a generally coherent, sequential narrative, all of the rest, the narratives that refrain from using the tetragrammaton before the time of Moses and their logical sequels that continue the same plot lines, still exhibit the features that indicate multiple authorship: redundancies (most notably two separate accounts of the revelation of the name Yahweh to Moses! Exod 3:11–15; 6:2–9), contradictions, discontinuities, and stylistic and conceptual inconsistencies beyond what would be expected in a work by a single author. Only at this stage was it discovered that the many passages initially classified as E actually comprise two interwoven narrative threads, one of them long, exquisitely structured, intricately detailed, and literarily and conceptually consistent beyond any other narrative source in the Bible, and the other modest in its scope, fragmentary in several places, and literarily and conceptually less complex (see Seidel 1993 ; Baden 2009 , 11–19). One cannot overestimate the importance of this discovery: it enabled scholarship to recognize the existence of the three separate narrative sources that compose the greater part of Torah, three sources distinct from one another in numerous and readily apparent ways.

This discovery also led to the realization that the fact that two of the sources share a single historical assumption with regard to the revelation of the tetragrammaton was essentially a coincidence of minor import. The disclosure of the name Yahweh, for all its significance, is not the central question on which the sources differ with one another; indeed very few of the differences between the sources stem from this issue. Still, this feature was canonized in scholarly terminology, and to this day biblical scholarship has retained the designations J and E. For a time, the two seemingly Elohistic sources were even designated as E1 and E2, but this classification fell out of favor, as the larger, more structured and consistent of the two (E1) began increasingly to be viewed as a sort of infrastructure for the other sources. It was hypothesized that this source, so broad in its scope and so detailed in all its particulars—including a precise and consistent chronology—must have served as the Torah’s framework, a literary receptacle into which the other sources were inserted. In keeping with the evolutionary approach to historical phenomena that dominated the humanities during the period that these discoveries were made, many claimed—with a certain naiveté, as it turned out—that this was also the most ancient of the four sources. It was therefore termed the Grundschrift or Foundational Text, and it received the designation G (Ewald 1831 )—but this too was not to last.

The role played by the Torah’s legal passages in the process of identifying the sources was no less important than that played by its narratives. In fact, even before biblical scholarship discovered that the narrative portion of the Torah was woven from separate threads that can be disentangled, earlier critics had noted that the legislation in the Torah readily divides into distinct, self-contained legal corpora. When the Enlightenment dawned in Western Europe and commentators began to abandon midrashic, homiletic, and allegorical methods of reconciling the interminable discrepancies between one law in the Torah and another, they realized that when each text is taken at its word rather than being forced into artificial harmony with the others, these inconsistencies indicate that each legal corpus is the work of a different legislator. Here too, owing to the impact of the newly ascendant historical sciences, the differences between the separate legal codes were viewed as evidence of different stages in ancient Israel’s legal and cultic development. It became only natural to regard each code of legislation as a link in the chain of historical progress in Israelite belief and religious practice.

The attempt to reconstruct the history of ancient Israelite religion by comparing and contrasting the different codes of law in the Torah was originally undertaken completely apart from the dissection of the threads that comprise the Torah’s narrative. For the most part, attention was initially focused on the laws of the Sabbath and festivals, as well as those of the sacrificial cult, the temple, and the priesthood, both because commands pertaining to these matters appear in each of the codes, providing an abundance of material for comparison, and because the development of these laws, which deal with the main practical manifestations of Israel’s religious faith, were thought to provide the best indication of the development of Israel’s faith itself.

A truly epoch-making finding in this connection concerned the unique character of the corpus of laws appearing within the framework of Moses’s parting orations, all of which are contained in the canonical book of Deuteronomy (Deut 12–26). The distinctive character of these laws enabled early critics to posit with rare unanimity that at least the greater part of the book of Deuteronomy constitutes an independent literary source and is not the continuation of the four preceding books. A number of unique characteristics typify this “Deuteronomic” law code. Its quintessential feature is the repeated demand to centralize Israel’s religious life, as well as aspects of its monarchic regime and the administration of justice, around a sacrificial cult practiced in a single, central temple—“the site that Yahweh will choose,” in the language of Deuteronomy (Deut 12:5 and passim)—and utterly to eradicate all localized places of worship, along with anything that might facilitate the practice of sacrificial worship “inside your gates” (Deut 12:17, et al.), which Deuteronomy’s law code views as tantamount to idolatry (Deut 11:31–12:8, 29–13:1). To this unique characteristic of Deuteronomy may be added two more. Firstly, of all the law codes in the Torah, only the code appearing in Deuteronomy is said to have been written down in the form of a sēfer or “book,” that is, a scroll, to be transmitted for use by later generations; secondly, only in Deuteronomy is there any mention of such a thing as sēfer ha-tôrâ —“the scroll of the torah ,” which is the term used by Deuteronomy to refer to the book in which the laws were written (Deut 28:61; 29:20; 30:10; 31:24, 26; see Haran 2003 , 35).

These realizations regarding Deuteronomy inevitably led scholars to address the question of a possible connection between the Deuteronomic legislation and the events reported to have taken place during the reign of King Josiah of Judah. According to the account in the book of Kings (2 Kgs 22–23), in the eighteenth year of Josiah’s reign, 622 bce , a scroll referred to as “the scroll of the torah ” was found in the house of Yahweh—the Jerusalem temple—the contents of which impelled Josiah immediately to initiate a comprehensive religious reform throughout the entire kingdom of Judah. The main objective of the reform, implemented by royal decree, was to rid Judah of all local cultic installations, repeatedly referred to in the book of Kings as the “high places”—במות—along with their cultic functionaries and furnishings, and to centralize the worship of Yahweh, thoroughly cleansed of all foreign influences, in the Jerusalem temple. The fact that the three components of Josiah’s reform—a long-lost scroll of legislation said to be from the time of Moses suddenly discovered in the temple, the name of this scroll, sēfer ha-tôrâ , and the nature of the religious reform carried out in accordance with its contents, namely the purification of worship and its centralization in the royal temple city—correspond fully to the three outstanding characteristics of the Deuteronomic law code cannot be mere coincidence. Already in late antiquity, a few of the church fathers held the opinion that the scroll found in the temple during the reign of Josiah was none other than the book of Deuteronomy. In the Middle Ages, an anonymous Jewish commentator whose commentary on Chronicles came erroneously to be attributed to Rashi arrived at the same conclusion (Viezel 2007 ). These early speculations were forgotten over time, however, and only in 1805 did the German scholar Wilhelm Martin Leberecht de Wette raise the possibility anew. De Wette went beyond his premodern predecessors, arriving at the inescapable historical implication of their suggestion, so inconceivable to them, namely that the scroll of Torah said to have been found in the temple during the reign of Josiah was in fact written at that time, in order to provide Mosaic—i.e. divine—authority for the religious reform undertaken by Josiah and his followers.

The distinctive character of the Deuteronomic source, which was thenceforth labeled “D” even though its contents do not comprise the whole of the book of Deuteronomy, was thus first recognized in its unique laws, specifically its cultic legislation. This new awareness led directly to an appreciation of the decisive role that this document played in Israelite history, as the “scroll of torah ” whose provisions the religious reform undertaken in the latter days of the kingdom of Judah sought to implement. These findings soon became axiomatic within critical scholarship. For over two centuries they have served as the basis for dating the other documents of the Torah and other biblical texts as well, and they remain the starting point for all discussion of the history of Israelite religion and the literary components of the Torah.

The second corpus of legislation whose unique character became apparent in the early days of biblical criticism, once again independently of the analysis of the narrative portion of the Torah, is the detailed series of commands occupying most of the central portion of the Torah and said to have been communicated orally to Moses in the tabernacle during the Israelites’ stay at Mount Sinai and thereafter. These laws deal at length and in precise detail with the sacrificial cult, the tabernacle and its accoutrements, the uninterrupted regimen of statutory worship conducted within its confines, the types of ritual impurity and the means of their eradication, permitted and forbidden foods, priests, Levites, and their respective functions, the Sabbath and festivals, the Sabbatical Year, the Jubilee, and related topics. Moreover even those laws said to have been given to Moses in the tabernacle and appearing to address secular issues such as sexual behavior, slavery, theft, jurisprudence, land tenure, and homicide do so from a decidedly sacral perspective, viewing all such matters through the lens of their impact on the cult and ritual purity. It became self-evident that this corpus of legislation, all of which displays a unique and readily identifiable style and all of whose provisions express a cult-focused ideology, is the work of a priestly school of scribal activity, most likely the priesthood of the Jerusalem temple. Scholarly recognition of the priestly provenance of this legislation began to coalesce well before its place among the narrative threads was recognized, and it was unanimously assigned the title Priesterkodex or “Priestly Code.”

Classical pentateuchal criticism reached its maturity when it finally arrived at an appreciation of the nature of the relationship between the separate legal corpora contained in the Torah and the independent threads interwoven in the narrative. This awareness too proceeded in stages. Early critics, heavily influenced both by the specific evolutionary model of Israel’s religious history prevalent at the time and by the dominant Protestant theology widespread among so many of them, assumed that the relationship between law and narrative is a chronological one. It seemed obvious that the authentic, ancient biblical tradition must have consisted of the tales of the Israelites and their ancestors, while the interminable lists of commandments, laws, and statutes presumably reflected a later development, wherein Israel’s natural, popular faith was transformed into an orderly, established religion, decaying into a pedantic, “Jewish” legalism (Baden 2009 , 19–43). This bipartite classification of the Torah literature became untenable, however, when it was realized that the Priestly law code was of a single piece with the detailed narrative thread then known as G. For once these two components had been discerned and isolated, it was impossible to ignore the thoroughgoing literary correlation between the two. Everything in the “G” narrative, from the first creation story on, is directed toward the erection of the tabernacle in the wilderness, the establishment of the sacrificial cult of Yahweh practiced therein, and the series of meetings between Yahweh and Moses that took place there, in the course of which all of Yahweh’s commands—the contents of the Priestly Code, all focused on the worship of Yahweh in the tabernacle and prescribing the measures needed to ensure his continued presence in his earthly abode—were imparted to Moses. A single literary style, a single terminology, a single religious outlook, a single chronology, and a single set of concepts and historical assumptions characterize both the continuous “G” narrative and the corpus of “Priestly” legislation, and the legislation is smoothly and flawlessly incorporated within G’s narrative thread. Once it was acknowledged that a single literary source clearly contained both a complete, sustained narrative thread and a detailed, comprehensive corpus of laws, it became impossible to uphold the theory of an “original,” early narrative to which the laws were a late accretion. Moreover, the two components not only exist side by side within a single literary source; they are entirely interdependent. The Priestly legislation is part of the historical narrative of G, while G’s narrative exists for the sake of the laws it relates and for their sake alone. The designations E1 and G were thus consigned to the dustbin of history, and scholars came to refer to this literary source as a whole—with both its components, the narrative and the laws, comprising one continuous strand—as the Priestly document, or P.