Literature Review: Google Scholar

- Sample Searches

- Examples of Published Literature Reviews

- Researching Your Topic

- Subject Searching

- Google Scholar

- Track Your Work

- Citation Managers This link opens in a new window

- Citation Guides This link opens in a new window

- Tips on Writing Your Literature Review This link opens in a new window

- Research Help

Google Scholar Library Links

To see links to BenU Library subscription content in your Google Scholar search results:

- Go to Google Scholar > Settings > Library Links

- Search " Benedictine "

- Check the boxes

- Click Save and you're done!

- Google Scholar Library Links Tutorial This tutorial will guide you step-by-step through the quick setup process.

Finding Academic Literature

- 8 Winning hacks to use Google Scholar for your research paper

Ask a Librarian

Chat with a Librarian

Lisle: (630) 829-6057 Mesa: (480) 878-7514 Toll Free: (877) 575-6050 Email: [email protected]

Book a Research Consultation Library Hours

- << Previous: Subject Searching

- Next: Track Your Work >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 3:34 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.ben.edu/lit-review

Kindlon Hall 5700 College Rd. Lisle, IL 60532 (630) 829-6050

Gillett Hall 225 E. Main St. Mesa, AZ 85201 (480) 878-7514

Reference management. Clean and simple.

Google Scholar: the ultimate guide

What is Google Scholar?

Why is google scholar better than google for finding research papers, the google scholar search results page, the first two lines: core bibliographic information, quick full text-access options, "cited by" count and other useful links, tips for searching google scholar, 1. google scholar searches are not case sensitive, 2. use keywords instead of full sentences, 3. use quotes to search for an exact match, 3. add the year to the search phrase to get articles published in a particular year, 4. use the side bar controls to adjust your search result, 5. use boolean operator to better control your searches, google scholar advanced search interface, customizing search preferences and options, using the "my library" feature in google scholar, the scope and limitations of google scholar, alternatives to google scholar, country-specific google scholar sites, frequently asked questions about google scholar, related articles.

Google Scholar (GS) is a free academic search engine that can be thought of as the academic version of Google. Rather than searching all of the indexed information on the web, it searches repositories of:

- universities

- scholarly websites

This is generally a smaller subset of the pool that Google searches. It's all done automatically, but most of the search results tend to be reliable scholarly sources.

However, Google is typically less careful about what it includes in search results than more curated, subscription-based academic databases like Scopus and Web of Science . As a result, it is important to take some time to assess the credibility of the resources linked through Google Scholar.

➡️ Take a look at our guide on the best academic databases .

One advantage of using Google Scholar is that the interface is comforting and familiar to anyone who uses Google. This lowers the learning curve of finding scholarly information .

There are a number of useful differences from a regular Google search. Google Scholar allows you to:

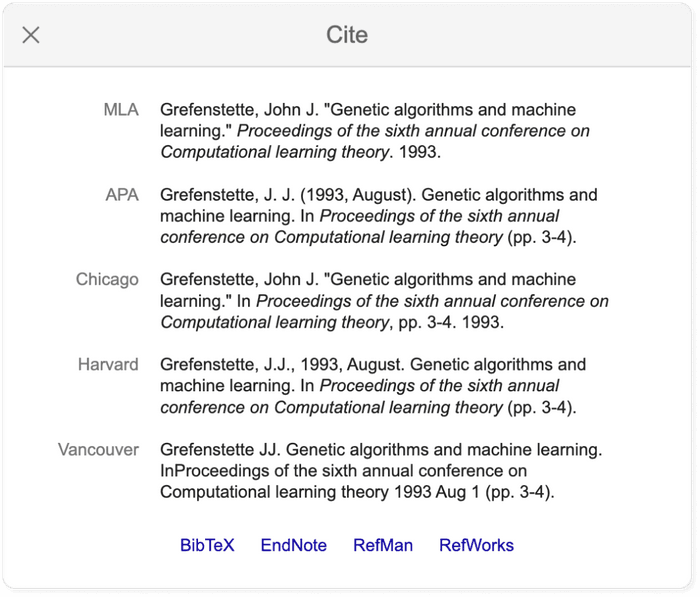

- copy a formatted citation in different styles including MLA and APA

- export bibliographic data (BibTeX, RIS) to use with reference management software

- explore other works have cited the listed work

- easily find full text versions of the article

Although it is free to search in Google Scholar, most of the content is not freely available. Google does its best to find copies of restricted articles in public repositories. If you are at an academic or research institution, you can also set up a library connection that allows you to see items that are available through your institution.

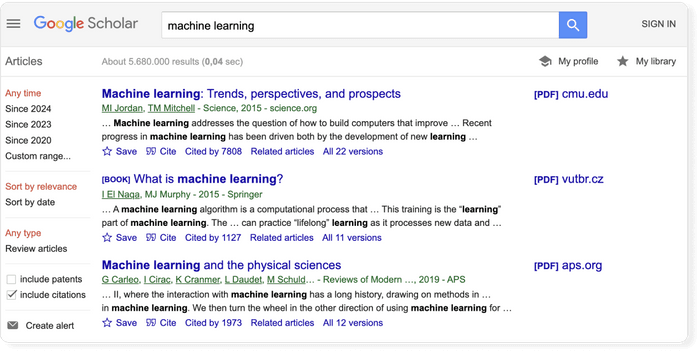

The Google Scholar results page differs from the Google results page in a few key ways. The search result page is, however, different and it is worth being familiar with the different pieces of information that are shown. Let's have a look at the results for the search term "machine learning.”

- The first line of each result provides the title of the document (e.g. of an article, book, chapter, or report).

- The second line provides the bibliographic information about the document, in order: the author(s), the journal or book it appears in, the year of publication, and the publisher.

Clicking on the title link will bring you to the publisher’s page where you may be able to access more information about the document. This includes the abstract and options to download the PDF.

To the far right of the entry are more direct options for obtaining the full text of the document. In this example, Google has also located a publicly available PDF of the document hosted at umich.edu . Note, that it's not guaranteed that it is the version of the article that was finally published in the journal.

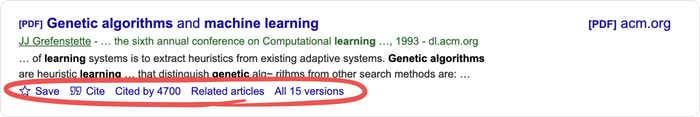

Below the text snippet/abstract you can find a number of useful links.

- Cited by : the cited by link will show other articles that have cited this resource. That is a super useful feature that can help you in many ways. First, it is a good way to track the more recent research that has referenced this article, and second the fact that other researches cited this document lends greater credibility to it. But be aware that there is a lag in publication type. Therefore, an article published in 2017 will not have an extensive number of cited by results. It takes a minimum of 6 months for most articles to get published, so even if an article was using the source, the more recent article has not been published yet.

- Versions : this link will display other versions of the article or other databases where the article may be found, some of which may offer free access to the article.

- Quotation mark icon : this will display a popup with commonly used citation formats such as MLA, APA, Chicago, Harvard, and Vancouver that may be copied and pasted. Note, however, that the Google Scholar citation data is sometimes incomplete and so it is often a good idea to check this data at the source. The "cite" popup also includes links for exporting the citation data as BibTeX or RIS files that any major reference manager can import.

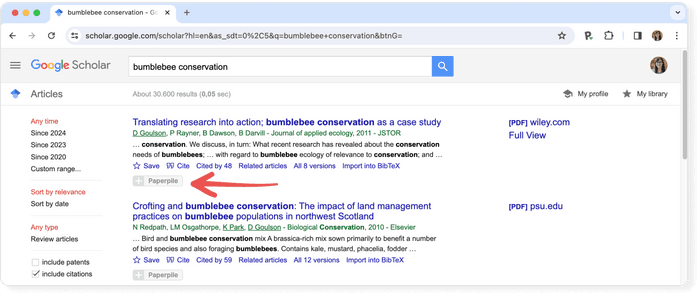

Pro tip: Use a reference manager like Paperpile to keep track of all your sources. Paperpile integrates with Google Scholar and many popular academic research engines and databases, so you can save references and PDFs directly to your library using the Paperpile buttons and later cite them in thousands of citation styles:

Although Google Scholar limits each search to a maximum of 1,000 results , it's still too much to explore, and you need an effective way of locating the relevant articles. Here’s a list of pro tips that will help you save time and search more effectively.

You don’t need to worry about case sensitivity when you’re using Google scholar. In other words, a search for "Machine Learning" will produce the same results as a search for "machine learning.”

Let's say your research topic is about self driving cars. For a regular Google search we might enter something like " what is the current state of the technology used for self driving cars ". In Google Scholar, you will see less than ideal results for this query .

The trick is to build a list of keywords and perform searches for them like self-driving cars, autonomous vehicles, or driverless cars. Google Scholar will assist you on that: if you start typing in the search field you will see related queries suggested by Scholar!

If you put your search phrase into quotes you can search for exact matches of that phrase in the title and the body text of the document. Without quotes, Google Scholar will treat each word separately.

This means that if you search national parks , the words will not necessarily appear together. Grouped words and exact phrases should be enclosed in quotation marks.

A search using “self-driving cars 2015,” for example, will return articles or books published in 2015.

Using the options in the left hand panel you can further restrict the search results by limiting the years covered by the search, the inclusion or exclude of patents, and you can sort the results by relevance or by date.

Searches are not case sensitive, however, there are a number of Boolean operators you can use to control the search and these must be capitalized.

- AND requires both of the words or phrases on either side to be somewhere in the record.

- NOT can be placed in front of a word or phrases to exclude results which include them.

- OR will give equal weight to results which match just one of the words or phrases on either side.

➡️ Read more about how to efficiently search online databases for academic research .

In case you got overwhelmed by the above options, here’s some illustrative examples:

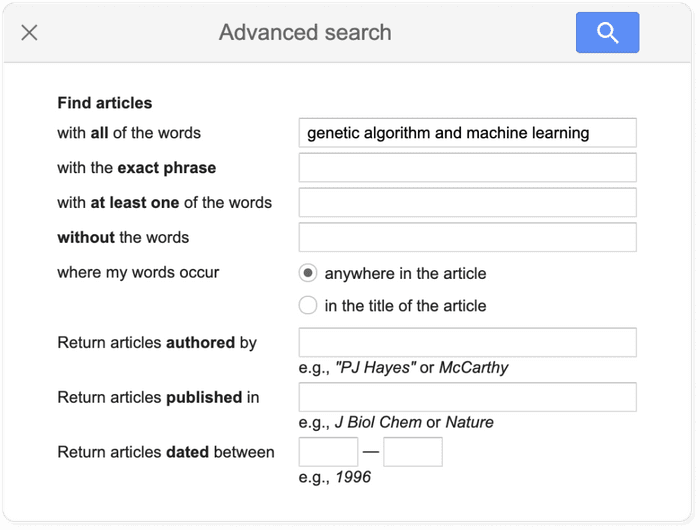

Tip: Use the advanced search features in Google Scholar to narrow down your search results.

You can gain even more fine-grained control over your search by using the advanced search feature. This feature is available by clicking on the hamburger menu in the upper left and selecting the "Advanced search" menu item.

Adjusting the Google Scholar settings is not necessary for getting good results, but offers some additional customization, including the ability to enable the above-mentioned library integrations.

The settings menu is found in the hamburger menu located in the top left of the Google Scholar page. The settings are divided into five sections:

- Collections to search: by default Google scholar searches articles and includes patents, but this default can be changed if you are not interested in patents or if you wish to search case law instead.

- Bibliographic manager: you can export relevant citation data via the “Bibliography manager” subsection.

- Languages: if you wish for results to return only articles written in a specific subset of languages, you can define that here.

- Library links: as noted, Google Scholar allows you to get the Full Text of articles through your institution’s subscriptions, where available. Search for, and add, your institution here to have the relevant link included in your search results.

- Button: the Scholar Button is a Chrome extension which adds a dropdown search box to your toolbar. This allows you to search Google Scholar from any website. Moreover, if you have any text selected on the page and then click the button it will display results from a search on those words when clicked.

When signed in, Google Scholar adds some simple tools for keeping track of and organizing the articles you find. These can be useful if you are not using a full academic reference manager.

All the search results include a “save” button at the end of the bottom row of links, clicking this will add it to your "My Library".

To help you provide some structure, you can create and apply labels to the items in your library. Appended labels will appear at the end of the article titles. For example, the following article has been assigned a “RNA” label:

Within your Google Scholar library, you can also edit the metadata associated with titles. This will often be necessary as Google Scholar citation data is often faulty.

There is no official statement about how big the Scholar search index is, but unofficial estimates are in the range of about 160 million , and it is supposed to continue to grow by several million each year.

Yet, Google Scholar does not return all resources that you may get in search at you local library catalog. For example, a library database could return podcasts, videos, articles, statistics, or special collections. For now, Google Scholar has only the following publication types:

- Journal articles : articles published in journals. It's a mixture of articles from peer reviewed journals, predatory journals and pre-print archives.

- Books : links to the Google limited version of the text, when possible.

- Book chapters : chapters within a book, sometimes they are also electronically available.

- Book reviews : reviews of books, but it is not always apparent that it is a review from the search result.

- Conference proceedings : papers written as part of a conference, typically used as part of presentation at the conference.

- Court opinions .

- Patents : Google Scholar only searches patents if the option is selected in the search settings described above.

The information in Google Scholar is not cataloged by professionals. The quality of the metadata will depend heavily on the source that Google Scholar is pulling the information from. This is a much different process to how information is collected and indexed in scholarly databases such as Scopus or Web of Science .

➡️ Visit our list of the best academic databases .

Google Scholar is by far the most frequently used academic search engine , but it is not the only one. Other academic search engines include:

- Science.gov

- Semantic Scholar

- scholar.google.fr : Sur les épaules d'un géant

- scholar.google.es (Google Académico): A hombros de gigantes

- scholar.google.pt (Google Académico): Sobre os ombros de gigantes

- scholar.google.de : Auf den Schultern von Riesen

➡️ Once you’ve found some research, it’s time to read it. Take a look at our guide on how to read a scientific paper .

No. Google Scholar is a bibliographic search engine rather than a bibliographic database. In order to qualify as a database Google Scholar would need to have stable identifiers for its records.

No. Google Scholar is an academic search engine, but the records found in Google Scholar are scholarly sources.

No. Google Scholar collects research papers from all over the web, including grey literature and non-peer reviewed papers and reports.

Google Scholar does not provide any full text content itself, but links to the full text article on the publisher page, which can either be open access or paywalled content. Google Scholar tries to provide links to free versions, when possible.

The easiest way to access Google scholar is by using The Google Scholar Button. This is a browser extension that allows you easily access Google Scholar from any web page. You can install it from the Chrome Webstore .

How To Write An A-Grade Literature Review

3 straightforward steps (with examples) + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2019

Quality research is about building onto the existing work of others , “standing on the shoulders of giants”, as Newton put it. The literature review chapter of your dissertation, thesis or research project is where you synthesise this prior work and lay the theoretical foundation for your own research.

Long story short, this chapter is a pretty big deal, which is why you want to make sure you get it right . In this post, I’ll show you exactly how to write a literature review in three straightforward steps, so you can conquer this vital chapter (the smart way).

Overview: The Literature Review Process

- Understanding the “ why “

- Finding the relevant literature

- Cataloguing and synthesising the information

- Outlining & writing up your literature review

- Example of a literature review

But first, the “why”…

Before we unpack how to write the literature review chapter, we’ve got to look at the why . To put it bluntly, if you don’t understand the function and purpose of the literature review process, there’s no way you can pull it off well. So, what exactly is the purpose of the literature review?

Well, there are (at least) four core functions:

- For you to gain an understanding (and demonstrate this understanding) of where the research is at currently, what the key arguments and disagreements are.

- For you to identify the gap(s) in the literature and then use this as justification for your own research topic.

- To help you build a conceptual framework for empirical testing (if applicable to your research topic).

- To inform your methodological choices and help you source tried and tested questionnaires (for interviews ) and measurement instruments (for surveys ).

Most students understand the first point but don’t give any thought to the rest. To get the most from the literature review process, you must keep all four points front of mind as you review the literature (more on this shortly), or you’ll land up with a wonky foundation.

Okay – with the why out the way, let’s move on to the how . As mentioned above, writing your literature review is a process, which I’ll break down into three steps:

- Finding the most suitable literature

- Understanding , distilling and organising the literature

- Planning and writing up your literature review chapter

Importantly, you must complete steps one and two before you start writing up your chapter. I know it’s very tempting, but don’t try to kill two birds with one stone and write as you read. You’ll invariably end up wasting huge amounts of time re-writing and re-shaping, or you’ll just land up with a disjointed, hard-to-digest mess . Instead, you need to read first and distil the information, then plan and execute the writing.

Step 1: Find the relevant literature

Naturally, the first step in the literature review journey is to hunt down the existing research that’s relevant to your topic. While you probably already have a decent base of this from your research proposal , you need to expand on this substantially in the dissertation or thesis itself.

Essentially, you need to be looking for any existing literature that potentially helps you answer your research question (or develop it, if that’s not yet pinned down). There are numerous ways to find relevant literature, but I’ll cover my top four tactics here. I’d suggest combining all four methods to ensure that nothing slips past you:

Method 1 – Google Scholar Scrubbing

Google’s academic search engine, Google Scholar , is a great starting point as it provides a good high-level view of the relevant journal articles for whatever keyword you throw at it. Most valuably, it tells you how many times each article has been cited, which gives you an idea of how credible (or at least, popular) it is. Some articles will be free to access, while others will require an account, which brings us to the next method.

Method 2 – University Database Scrounging

Generally, universities provide students with access to an online library, which provides access to many (but not all) of the major journals.

So, if you find an article using Google Scholar that requires paid access (which is quite likely), search for that article in your university’s database – if it’s listed there, you’ll have access. Note that, generally, the search engine capabilities of these databases are poor, so make sure you search for the exact article name, or you might not find it.

Method 3 – Journal Article Snowballing

At the end of every academic journal article, you’ll find a list of references. As with any academic writing, these references are the building blocks of the article, so if the article is relevant to your topic, there’s a good chance a portion of the referenced works will be too. Do a quick scan of the titles and see what seems relevant, then search for the relevant ones in your university’s database.

Method 4 – Dissertation Scavenging

Similar to Method 3 above, you can leverage other students’ dissertations. All you have to do is skim through literature review chapters of existing dissertations related to your topic and you’ll find a gold mine of potential literature. Usually, your university will provide you with access to previous students’ dissertations, but you can also find a much larger selection in the following databases:

- Open Access Theses & Dissertations

- Stanford SearchWorks

Keep in mind that dissertations and theses are not as academically sound as published, peer-reviewed journal articles (because they’re written by students, not professionals), so be sure to check the credibility of any sources you find using this method. You can do this by assessing the citation count of any given article in Google Scholar. If you need help with assessing the credibility of any article, or with finding relevant research in general, you can chat with one of our Research Specialists .

Alright – with a good base of literature firmly under your belt, it’s time to move onto the next step.

Need a helping hand?

Step 2: Log, catalogue and synthesise

Once you’ve built a little treasure trove of articles, it’s time to get reading and start digesting the information – what does it all mean?

While I present steps one and two (hunting and digesting) as sequential, in reality, it’s more of a back-and-forth tango – you’ll read a little , then have an idea, spot a new citation, or a new potential variable, and then go back to searching for articles. This is perfectly natural – through the reading process, your thoughts will develop , new avenues might crop up, and directional adjustments might arise. This is, after all, one of the main purposes of the literature review process (i.e. to familiarise yourself with the current state of research in your field).

As you’re working through your treasure chest, it’s essential that you simultaneously start organising the information. There are three aspects to this:

- Logging reference information

- Building an organised catalogue

- Distilling and synthesising the information

I’ll discuss each of these below:

2.1 – Log the reference information

As you read each article, you should add it to your reference management software. I usually recommend Mendeley for this purpose (see the Mendeley 101 video below), but you can use whichever software you’re comfortable with. Most importantly, make sure you load EVERY article you read into your reference manager, even if it doesn’t seem very relevant at the time.

2.2 – Build an organised catalogue

In the beginning, you might feel confident that you can remember who said what, where, and what their main arguments were. Trust me, you won’t. If you do a thorough review of the relevant literature (as you must!), you’re going to read many, many articles, and it’s simply impossible to remember who said what, when, and in what context . Also, without the bird’s eye view that a catalogue provides, you’ll miss connections between various articles, and have no view of how the research developed over time. Simply put, it’s essential to build your own catalogue of the literature.

I would suggest using Excel to build your catalogue, as it allows you to run filters, colour code and sort – all very useful when your list grows large (which it will). How you lay your spreadsheet out is up to you, but I’d suggest you have the following columns (at minimum):

- Author, date, title – Start with three columns containing this core information. This will make it easy for you to search for titles with certain words, order research by date, or group by author.

- Categories or keywords – You can either create multiple columns, one for each category/theme and then tick the relevant categories, or you can have one column with keywords.

- Key arguments/points – Use this column to succinctly convey the essence of the article, the key arguments and implications thereof for your research.

- Context – Note the socioeconomic context in which the research was undertaken. For example, US-based, respondents aged 25-35, lower- income, etc. This will be useful for making an argument about gaps in the research.

- Methodology – Note which methodology was used and why. Also, note any issues you feel arise due to the methodology. Again, you can use this to make an argument about gaps in the research.

- Quotations – Note down any quoteworthy lines you feel might be useful later.

- Notes – Make notes about anything not already covered. For example, linkages to or disagreements with other theories, questions raised but unanswered, shortcomings or limitations, and so forth.

If you’d like, you can try out our free catalog template here (see screenshot below).

2.3 – Digest and synthesise

Most importantly, as you work through the literature and build your catalogue, you need to synthesise all the information in your own mind – how does it all fit together? Look for links between the various articles and try to develop a bigger picture view of the state of the research. Some important questions to ask yourself are:

- What answers does the existing research provide to my own research questions ?

- Which points do the researchers agree (and disagree) on?

- How has the research developed over time?

- Where do the gaps in the current research lie?

To help you develop a big-picture view and synthesise all the information, you might find mind mapping software such as Freemind useful. Alternatively, if you’re a fan of physical note-taking, investing in a large whiteboard might work for you.

Step 3: Outline and write it up!

Once you’re satisfied that you have digested and distilled all the relevant literature in your mind, it’s time to put pen to paper (or rather, fingers to keyboard). There are two steps here – outlining and writing:

3.1 – Draw up your outline

Having spent so much time reading, it might be tempting to just start writing up without a clear structure in mind. However, it’s critically important to decide on your structure and develop a detailed outline before you write anything. Your literature review chapter needs to present a clear, logical and an easy to follow narrative – and that requires some planning. Don’t try to wing it!

Naturally, you won’t always follow the plan to the letter, but without a detailed outline, you’re more than likely going to end up with a disjointed pile of waffle , and then you’re going to spend a far greater amount of time re-writing, hacking and patching. The adage, “measure twice, cut once” is very suitable here.

In terms of structure, the first decision you’ll have to make is whether you’ll lay out your review thematically (into themes) or chronologically (by date/period). The right choice depends on your topic, research objectives and research questions, which we discuss in this article .

Once that’s decided, you need to draw up an outline of your entire chapter in bullet point format. Try to get as detailed as possible, so that you know exactly what you’ll cover where, how each section will connect to the next, and how your entire argument will develop throughout the chapter. Also, at this stage, it’s a good idea to allocate rough word count limits for each section, so that you can identify word count problems before you’ve spent weeks or months writing!

PS – check out our free literature review chapter template…

3.2 – Get writing

With a detailed outline at your side, it’s time to start writing up (finally!). At this stage, it’s common to feel a bit of writer’s block and find yourself procrastinating under the pressure of finally having to put something on paper. To help with this, remember that the objective of the first draft is not perfection – it’s simply to get your thoughts out of your head and onto paper, after which you can refine them. The structure might change a little, the word count allocations might shift and shuffle, and you might add or remove a section – that’s all okay. Don’t worry about all this on your first draft – just get your thoughts down on paper.

Once you’ve got a full first draft (however rough it may be), step away from it for a day or two (longer if you can) and then come back at it with fresh eyes. Pay particular attention to the flow and narrative – does it fall fit together and flow from one section to another smoothly? Now’s the time to try to improve the linkage from each section to the next, tighten up the writing to be more concise, trim down word count and sand it down into a more digestible read.

Once you’ve done that, give your writing to a friend or colleague who is not a subject matter expert and ask them if they understand the overall discussion. The best way to assess this is to ask them to explain the chapter back to you. This technique will give you a strong indication of which points were clearly communicated and which weren’t. If you’re working with Grad Coach, this is a good time to have your Research Specialist review your chapter.

Finally, tighten it up and send it off to your supervisor for comment. Some might argue that you should be sending your work to your supervisor sooner than this (indeed your university might formally require this), but in my experience, supervisors are extremely short on time (and often patience), so, the more refined your chapter is, the less time they’ll waste on addressing basic issues (which you know about already) and the more time they’ll spend on valuable feedback that will increase your mark-earning potential.

Literature Review Example

In the video below, we unpack an actual literature review so that you can see how all the core components come together in reality.

Let’s Recap

In this post, we’ve covered how to research and write up a high-quality literature review chapter. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- It is essential to understand the WHY of the literature review before you read or write anything. Make sure you understand the 4 core functions of the process.

- The first step is to hunt down the relevant literature . You can do this using Google Scholar, your university database, the snowballing technique and by reviewing other dissertations and theses.

- Next, you need to log all the articles in your reference manager , build your own catalogue of literature and synthesise all the research.

- Following that, you need to develop a detailed outline of your entire chapter – the more detail the better. Don’t start writing without a clear outline (on paper, not in your head!)

- Write up your first draft in rough form – don’t aim for perfection. Remember, done beats perfect.

- Refine your second draft and get a layman’s perspective on it . Then tighten it up and submit it to your supervisor.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

38 Comments

Thank you very much. This page is an eye opener and easy to comprehend.

This is awesome!

I wish I come across GradCoach earlier enough.

But all the same I’ll make use of this opportunity to the fullest.

Thank you for this good job.

Keep it up!

You’re welcome, Yinka. Thank you for the kind words. All the best writing your literature review.

Thank you for a very useful literature review session. Although I am doing most of the steps…it being my first masters an Mphil is a self study and one not sure you are on the right track. I have an amazing supervisor but one also knows they are super busy. So not wanting to bother on the minutae. Thank you.

You’re most welcome, Renee. Good luck with your literature review 🙂

This has been really helpful. Will make full use of it. 🙂

Thank you Gradcoach.

Really agreed. Admirable effort

thank you for this beautiful well explained recap.

Thank you so much for your guide of video and other instructions for the dissertation writing.

It is instrumental. It encouraged me to write a dissertation now.

Thank you the video was great – from someone that knows nothing thankyou

an amazing and very constructive way of presetting a topic, very useful, thanks for the effort,

It is timely

It is very good video of guidance for writing a research proposal and a dissertation. Since I have been watching and reading instructions, I have started my research proposal to write. I appreciate to Mr Jansen hugely.

I learn a lot from your videos. Very comprehensive and detailed.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge. As a research student, you learn better with your learning tips in research

I was really stuck in reading and gathering information but after watching these things are cleared thanks, it is so helpful.

Really helpful, Thank you for the effort in showing such information

This is super helpful thank you very much.

Thank you for this whole literature writing review.You have simplified the process.

I’m so glad I found GradCoach. Excellent information, Clear explanation, and Easy to follow, Many thanks Derek!

You’re welcome, Maithe. Good luck writing your literature review 🙂

Thank you Coach, you have greatly enriched and improved my knowledge

Great piece, so enriching and it is going to help me a great lot in my project and thesis, thanks so much

This is THE BEST site for ANYONE doing a masters or doctorate! Thank you for the sound advice and templates. You rock!

Thanks, Stephanie 🙂

This is mind blowing, the detailed explanation and simplicity is perfect.

I am doing two papers on my final year thesis, and I must stay I feel very confident to face both headlong after reading this article.

thank you so much.

if anyone is to get a paper done on time and in the best way possible, GRADCOACH is certainly the go to area!

This is very good video which is well explained with detailed explanation

Thank you excellent piece of work and great mentoring

Thanks, it was useful

Thank you very much. the video and the information were very helpful.

Good morning scholar. I’m delighted coming to know you even before the commencement of my dissertation which hopefully is expected in not more than six months from now. I would love to engage my study under your guidance from the beginning to the end. I love to know how to do good job

Thank you so much Derek for such useful information on writing up a good literature review. I am at a stage where I need to start writing my one. My proposal was accepted late last year but I honestly did not know where to start

Like the name of your YouTube implies you are GRAD (great,resource person, about dissertation). In short you are smart enough in coaching research work.

This is a very well thought out webpage. Very informative and a great read.

Very timely.

I appreciate.

Very comprehensive and eye opener for me as beginner in postgraduate study. Well explained and easy to understand. Appreciate and good reference in guiding me in my research journey. Thank you

Thank you. I requested to download the free literature review template, however, your website wouldn’t allow me to complete the request or complete a download. May I request that you email me the free template? Thank you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- +91-0000000000

- [email protected]

- Research Gate

Koshal Research Support

—Information | Knowledge | Wisdom—

How To Conduct A Literature Review Using Google Scholar Step By Step Guide

A free academic search engine known as Google Scholar (GS) is sometimes referred to as the academic counterpart of Google. Instead of searching all of the online content that has been indexed, it searches publisher repositories, academic databases, or scholarly websites.

Typically, a smaller portion of the pool gets searched by Google in this manner. Even though everything is done automatically, the majority of search results come from trustworthy academic sources. In contrast to highly moderated subscription-based academic databases like Scopus and Web of Science, Google is also less selective about what it includes in search results, therefore it is important to determine the authority of the sources linked through Google Scholar on your own.

When conducting thorough searches, such as systematic reviews, Google Scholar (and Web of Science ) shouldn’t be used as a stand-alone resource for locating evidence and finding: Title searches rather than full-text searches in Google Scholar get much more results for ancient literature.

When you are going to complete a literature review , it’s essential to collect research information from many domains and eras, and google scholar is helpful in that regard.

Now, there are a few different reasons why I prefer using Google Scholar while conducting a literature review study.

The first is that Google does a reasonably good job of discovering all of the relevant work that is available online and indexing journals, conference papers, and research databases.

The second is that Google provides us with a few useful tools that we may use to browse the literature and find new information as we search.

- Tools for Automatic Referencing

- Free Online Citation Generator Tools

In order to show you how to use Google Scholar, allow me to give you an example. Consider that our literature review is looking for information on social eye observation in robotics.

Step By Step Guide of using Google Scholar for Literature search

Step 1: Type “ Google Schola r” into the search bar and click and find the google scholar dashboard

Note: The first thing to keep in mind is that you may type “google scholar” in the search field and use the same Google tactics as you would when conducting a regular Google search.

Step 2: Now you can search any topic of your interest on the search bar of google scholar For example, you can Search Fish farming by typing the word in the search bar and clicking the enter button.

Note: Add the word(s) in question to the search tab and press Enter to look for the exact phrase. And it’s clear that Google provides us with a lengthy list of results with the same outcomes. Additionally, it provides us with the paper’s title, the authors who wrote it (although it can be difficult to see on other platforms), where it was published, and the year (see above screenshot) So feel free to click on any of these sites immediately and find the articles details.

Despite these details, Google Scholar Dashboard will also indicate on the right-hand side of this page whether the article is directly available as a PDF (see above screenshot). If so, it will also let you know which website is hosting the PDF. This is due to the fact that PDFs aren’t always hosted by the journal or conference that published the work; instead, writers may upload the PDFs on their own personal pages, for instance.

If you want to find older works that may have been published a little while ago as well as more recent publications that really show the recent R&D in the field of the subject selected.

Step 3: Google scholar allows us to search for articles based on their publication date and years and if you wish to restrict our search, you can search articles starting in the year (as shown below ) 2022, we will only see paper those that have been released in the selected years and this aids in limiting the scope to the most recent work.

As shown above, we are obtaining all 2022 academic research papers (shown in the above screenshot) that have been published in that particular field, complete with source information If you wish to look for research within specific timeframes, you may also build a custom range of your search.

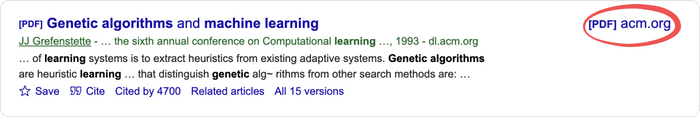

Now, if you read the references in a certain paper, you can locate pertinent articles that were released earlier than that paper. But google scholar offers us a convenient way to locate publications citation and cite scores (see inside the red circle in below screenshot)

Note: If you are enjoying a specific research article and also wanted to see whether there was any additional research that was interested in it and had cited the publication. To view a list of publications that have mentioned the article we are most interested in, click the “cited by” (as shown in the red circle of below screenshot) link and see results and use these papers for your literature review.

Step 4: Google Scholar also offers the ability to automatically generate references, and you can easily obtain several citation types or styles by simply checking the cite button and finding the results as displayed below screenshot.

As mentioned above, you can find references for citations in several citation formats. To use them, just copy and paste the references into your written document’s references area.

- Citation Writing Pattern

- How to Increase Your Citation

You can see that you may acquire the citations in a variety of different standardized formats by clicking the cite link that is located beneath each article as shown in the picture above.

In fact, if you read down to the bottom, you may also find the citation in BibTeX style (see in the red circle below screenshot) a text format that you can copy and paste directly into your bib file, which is particularly useful for students studying computer science field.

You can also use one more useful feature of Google Scholar is the ability to conduct a fresh Google search inside the articles that are quoting the article we’re most interested in by selecting “search within citing articles” from the drop-down menu. And by doing so, you can significantly hone in on your area of interest.

Step 5: Google scholar dashboard also provides us with the beneficial feature of occasionally being able to click on individual author names to access that author’s research profile.

As an illustration, by clicking on my name (Koshal Kumar) here, you can find a Google Scholar profile which I set up with a picture of myself and my affiliation and citation I received till date (see below red circle) and Google automatically indexes all of the articles online that are published by me.

In this way, you can find the literature you want, and google scholar is also automatically ordered by how frequently they have been cited, but you can manually sort by recency by clicking the year or by author name and titles of the paper. Additionally, it might occasionally be helpful to research recent works by a particular author while building your literature review, and finally, Google provides us with a convenient way to cite, allowing us to determine how to cite specific articles.

I do recommend checking the citation over, because oftentimes Google automatically generates it, and there may be some weirdness or errors in the way it has handled the title or the journal-title. So that was a whirlwind tour of how to use Google Scholar to do a literature review.

This is all about this article, and we sincerely hope that these steps and advice of using google scholar in the literature review will be useful to you as you are going to search for literature review online in your journey of research and you are familiar with the online literature review process. KressUp is an online learning platform that occasionally publishes new articles; stay connected to more updates

Please share and subscribe to our website so that it can help as many people as possible. You can also write to us at [email protected] for a free consultation if you’re looking for further E-content or research support.

If you find this article useful, don’t forget to share it!

Related Articles:

- What is A literature Review and Types of Literature Review

- How to write A literature Review paper II Literature Review Paper structure

- 4 Easy Steps To Writing A Literature Review Paper

- Important Purpose of Literature Review in Research

One thought on “How To Conduct A Literature Review Using Google Scholar Step By Step Guide”

- Pingback: What Are Citation Metrics And Why Are They Important | Koshal Research Support

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Literature Review & Research Skills Guide: Use Google Scholar

- Introduction

- What is a Literature Review?

- Your research topic

- Topic Analysis

- Developing a Search Strategy

- Preliminary Reading

- Use Primo Search

- Use Google Scholar

- Use Journal Databases

- Sage Research Methods

- Managing your literature review

- Evaluation & Critical Appraisal

- Referencing

Using Google Scholar

Google Scholar allows you to locate resources such as articles, theses and books.

Unlike Primo Search, which is set to search the Library's holdings only, Google Scholar searches beyond Charles Sturt University Library and will include resources that are not available to you.

Set up Library Links to access the Library's online resources using these instructions .

Google Scholar

Google Scholar is a search engine for scholarly information. It makes available information records that its 'robots' find or that an author, university repository, or journal publisher have chosen to list. It is useful because it searches across many resources and returns many resource types, including journal articles and book chapters, though it is important to note that results are not always from academic-quality sources and it will return both results you do have access to via Charles Sturt Library, and those you do not.

The video to the right provides you with an overview of Google Scholar, including how to change the settings so that it shows you which search results are held in Charles Sturt Library's collection:

Citation Searching

You can see who has cited a resource from the results page in Google Scholar. Once you've located a source you like, you can view who has cited that resource by clicking on the 'Cited by x' link beneath the item record.

You will then see all of the resources that have cited the original item. Keep in mind that this does not include every resource that has ever cited the original item - it only includes those resources that are indexed in Google Scholar.

In the Google Scholar Search box at the top of the page, enter some keywords that you identified in your topic analysis

- Use the left hand menu to limit by date.

- Have you set your library links? Select the Find it at CSU links to access articles in our collection.

- You may notice that there is a mix of topics, including health, education etc. Add more keywords to your search to narrow it down.

Search Google Scholar

Using Google effectively

Citation searching

- << Previous: Use Primo Search

- Next: Use Journal Databases >>

- Last Updated: Apr 8, 2024 11:56 AM

- URL: https://libguides.csu.edu.au/education-research

Charles Sturt University is an Australian University, TEQSA Provider Identification: PRV12018. CRICOS Provider: 00005F.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

Want to make a difference? Try working at an environmental non-profit organization

Career Feature 26 APR 24

Scientists urged to collect royalties from the ‘magic money tree’

Career Feature 25 APR 24

NIH pay rise for postdocs and PhD students could have US ripple effect

News 25 APR 24

Algorithm ranks peer reviewers by reputation — but critics warn of bias

Nature Index 25 APR 24

Researchers want a ‘nutrition label’ for academic-paper facts

Nature Index 17 APR 24

How young people benefit from Swiss apprenticeships

Spotlight 17 APR 24

Retractions are part of science, but misconduct isn’t — lessons from a superconductivity lab

Editorial 24 APR 24

Berlin (DE)

Springer Nature Group

ECUST Seeking Global Talents

Join Us and Create a Bright Future Together!

Shanghai, China

East China University of Science and Technology (ECUST)

Position Recruitment of Guangzhou Medical University

Seeking talents around the world.

Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

Guangzhou Medical University

Junior Group Leader

The Imagine Institute is a leading European research centre dedicated to genetic diseases, with the primary objective to better understand and trea...

Paris, Ile-de-France (FR)

Imagine Institute

Director of the Czech Advanced Technology and Research Institute of Palacký University Olomouc

The Rector of Palacký University Olomouc announces a Call for the Position of Director of the Czech Advanced Technology and Research Institute of P...

Czech Republic (CZ)

Palacký University Olomouc

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Literature Reviews and Annotated Bibliographies

Initial databases for a literature review.

What is a Literature Review?

- How to Write a Literature Review?

- Graduate Research and the Literature Review

- What is an Annotated Bibliography?

- How to Evaluate Sources?

- Citation & Avoiding Plagiarism

The databases listed here are interdisciplinary and suitable for most disciplines. For databases specific to your discipline see our Research Guides

Academic Search Ultimate Includes some full text

A great place to start to search for magazine and journal articles on almost all topics. Tip : Check "peer reviewed" box to limit your search to scholarly journals.

Dissertations and Theses (1861+) Indexes dissertations accepted for doctoral degrees by accredited North American educational institutions and over 200 other institutions. Also covers masters theses since 1962. Starting in the early to mid-1900's, the full text is included for an increasingly comprehensive number of dissertations and theses.

Google Scholar Enables you to search specifically for scholarly literature, including peer-reviewed papers, theses, books, preprints, abstracts and technical reports from all broad areas of research. Use Google Scholar to find articles from a widevariety of academic publishers, professional societies, preprint repositories and universities, as well as scholarly articles available across the web

Humanities and Social Science Retrospective Bibliographic database that provides citations to articles in a wide range of English language journals in the humanities and social sciences for the period 1907-1984.

JSTOR Includes full text Includes long runs of backfiles of scholarly journals. Subjects covered include Anthropology, Asian Studies, Ecology, Economics, Education, Finance, History, Mathematics, Philosophy, Political Science, Population Studies, and Sociology.

Periodical Archives Online- (1770-1995) Includes full text; Full text archive of hundreds of periodicals in the humanities and social sciences from their first issues to 1995 Allows date-limited searching. Periodical Index Online, 1665 - 1995

"A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. Occasionally you will be asked to write one as a separate assignment, ..., but more often it is part of the introduction to an essay, research report, or thesis. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries."

--Written by Dena Taylor, Health Sciences Writing Centre and available at http://www.writing.utoronto.ca/advice/specific-types-of-writing/literature-review (Accessed August 8th, 2011)

Writing the Literature Review sites :

Literature Reviews: UNC - Chapel Hill

Write a Literature Review: UC-Santa Cruz

Writing a Literature Review: Perdue OWL

Methods Map: Literature Review

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review?

- To develop a new theory

- To evaluate a theory or theories

- To survey what’s known about a topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

- Provide a historical overview of the development of a topic

Type of Literature Reviews:

- Mature and/or established topic: Topic is well-known and the purpose of this type of review is to analyze and synthesize this accumulated body of research.

- Emerging Topic: The purpose of this type of review to identify understudy or new emerging research area.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: How to Write a Literature Review? >>

- Last updated: Jan 8, 2024 2:52 PM

- URL: https://libguides.asu.edu/LiteratureReviews

The ASU Library acknowledges the twenty-three Native Nations that have inhabited this land for centuries. Arizona State University's four campuses are located in the Salt River Valley on ancestral territories of Indigenous peoples, including the Akimel O’odham (Pima) and Pee Posh (Maricopa) Indian Communities, whose care and keeping of these lands allows us to be here today. ASU Library acknowledges the sovereignty of these nations and seeks to foster an environment of success and possibility for Native American students and patrons. We are advocates for the incorporation of Indigenous knowledge systems and research methodologies within contemporary library practice. ASU Library welcomes members of the Akimel O’odham and Pee Posh, and all Native nations to the Library.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Clinics (Sao Paulo)

Approaching literature review for academic purposes: The Literature Review Checklist

Debora f.b. leite.

I Departamento de Ginecologia e Obstetricia, Faculdade de Ciencias Medicas, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, SP, BR

II Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Pernambuco, PE, BR

III Hospital das Clinicas, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Pernambuco, PE, BR

Maria Auxiliadora Soares Padilha

Jose g. cecatti.

A sophisticated literature review (LR) can result in a robust dissertation/thesis by scrutinizing the main problem examined by the academic study; anticipating research hypotheses, methods and results; and maintaining the interest of the audience in how the dissertation/thesis will provide solutions for the current gaps in a particular field. Unfortunately, little guidance is available on elaborating LRs, and writing an LR chapter is not a linear process. An LR translates students’ abilities in information literacy, the language domain, and critical writing. Students in postgraduate programs should be systematically trained in these skills. Therefore, this paper discusses the purposes of LRs in dissertations and theses. Second, the paper considers five steps for developing a review: defining the main topic, searching the literature, analyzing the results, writing the review and reflecting on the writing. Ultimately, this study proposes a twelve-item LR checklist. By clearly stating the desired achievements, this checklist allows Masters and Ph.D. students to continuously assess their own progress in elaborating an LR. Institutions aiming to strengthen students’ necessary skills in critical academic writing should also use this tool.

INTRODUCTION

Writing the literature review (LR) is often viewed as a difficult task that can be a point of writer’s block and procrastination ( 1 ) in postgraduate life. Disagreements on the definitions or classifications of LRs ( 2 ) may confuse students about their purpose and scope, as well as how to perform an LR. Interestingly, at many universities, the LR is still an important element in any academic work, despite the more recent trend of producing scientific articles rather than classical theses.

The LR is not an isolated section of the thesis/dissertation or a copy of the background section of a research proposal. It identifies the state-of-the-art knowledge in a particular field, clarifies information that is already known, elucidates implications of the problem being analyzed, links theory and practice ( 3 - 5 ), highlights gaps in the current literature, and places the dissertation/thesis within the research agenda of that field. Additionally, by writing the LR, postgraduate students will comprehend the structure of the subject and elaborate on their cognitive connections ( 3 ) while analyzing and synthesizing data with increasing maturity.

At the same time, the LR transforms the student and hints at the contents of other chapters for the reader. First, the LR explains the research question; second, it supports the hypothesis, objectives, and methods of the research project; and finally, it facilitates a description of the student’s interpretation of the results and his/her conclusions. For scholars, the LR is an introductory chapter ( 6 ). If it is well written, it demonstrates the student’s understanding of and maturity in a particular topic. A sound and sophisticated LR can indicate a robust dissertation/thesis.

A consensus on the best method to elaborate a dissertation/thesis has not been achieved. The LR can be a distinct chapter or included in different sections; it can be part of the introduction chapter, part of each research topic, or part of each published paper ( 7 ). However, scholars view the LR as an integral part of the main body of an academic work because it is intrinsically connected to other sections ( Figure 1 ) and is frequently present. The structure of the LR depends on the conventions of a particular discipline, the rules of the department, and the student’s and supervisor’s areas of expertise, needs and interests.

Interestingly, many postgraduate students choose to submit their LR to peer-reviewed journals. As LRs are critical evaluations of current knowledge, they are indeed publishable material, even in the form of narrative or systematic reviews. However, systematic reviews have specific patterns 1 ( 8 ) that may not entirely fit with the questions posed in the dissertation/thesis. Additionally, the scope of a systematic review may be too narrow, and the strict criteria for study inclusion may omit important information from the dissertation/thesis. Therefore, this essay discusses the definition of an LR is and methods to develop an LR in the context of an academic dissertation/thesis. Finally, we suggest a checklist to evaluate an LR.

WHAT IS A LITERATURE REVIEW IN A THESIS?

Conducting research and writing a dissertation/thesis translates rational thinking and enthusiasm ( 9 ). While a strong body of literature that instructs students on research methodology, data analysis and writing scientific papers exists, little guidance on performing LRs is available. The LR is a unique opportunity to assess and contrast various arguments and theories, not just summarize them. The research results should not be discussed within the LR, but the postgraduate student tends to write a comprehensive LR while reflecting on his or her own findings ( 10 ).

Many people believe that writing an LR is a lonely and linear process. Supervisors or the institutions assume that the Ph.D. student has mastered the relevant techniques and vocabulary associated with his/her subject and conducts a self-reflection about previously published findings. Indeed, while elaborating the LR, the student should aggregate diverse skills, which mainly rely on his/her own commitment to mastering them. Thus, less supervision should be required ( 11 ). However, the parameters described above might not currently be the case for many students ( 11 , 12 ), and the lack of formal and systematic training on writing LRs is an important concern ( 11 ).

An institutional environment devoted to active learning will provide students the opportunity to continuously reflect on LRs, which will form a dialogue between the postgraduate student and the current literature in a particular field ( 13 ). Postgraduate students will be interpreting studies by other researchers, and, according to Hart (1998) ( 3 ), the outcomes of the LR in a dissertation/thesis include the following:

- To identify what research has been performed and what topics require further investigation in a particular field of knowledge;

- To determine the context of the problem;

- To recognize the main methodologies and techniques that have been used in the past;

- To place the current research project within the historical, methodological and theoretical context of a particular field;

- To identify significant aspects of the topic;

- To elucidate the implications of the topic;

- To offer an alternative perspective;

- To discern how the studied subject is structured;

- To improve the student’s subject vocabulary in a particular field; and

- To characterize the links between theory and practice.

A sound LR translates the postgraduate student’s expertise in academic and scientific writing: it expresses his/her level of comfort with synthesizing ideas ( 11 ). The LR reveals how well the postgraduate student has proceeded in three domains: an effective literature search, the language domain, and critical writing.

Effective literature search

All students should be trained in gathering appropriate data for specific purposes, and information literacy skills are a cornerstone. These skills are defined as “an individual’s ability to know when they need information, to identify information that can help them address the issue or problem at hand, and to locate, evaluate, and use that information effectively” ( 14 ). Librarian support is of vital importance in coaching the appropriate use of Boolean logic (AND, OR, NOT) and other tools for highly efficient literature searches (e.g., quotation marks and truncation), as is the appropriate management of electronic databases.

Language domain

Academic writing must be concise and precise: unnecessary words distract the reader from the essential content ( 15 ). In this context, reading about issues distant from the research topic ( 16 ) may increase students’ general vocabulary and familiarity with grammar. Ultimately, reading diverse materials facilitates and encourages the writing process itself.

Critical writing

Critical judgment includes critical reading, thinking and writing. It supposes a student’s analytical reflection about what he/she has read. The student should delineate the basic elements of the topic, characterize the most relevant claims, identify relationships, and finally contrast those relationships ( 17 ). Each scientific document highlights the perspective of the author, and students will become more confident in judging the supporting evidence and underlying premises of a study and constructing their own counterargument as they read more articles. A paucity of integration or contradictory perspectives indicates lower levels of cognitive complexity ( 12 ).

Thus, while elaborating an LR, the postgraduate student should achieve the highest category of Bloom’s cognitive skills: evaluation ( 12 ). The writer should not only summarize data and understand each topic but also be able to make judgments based on objective criteria, compare resources and findings, identify discrepancies due to methodology, and construct his/her own argument ( 12 ). As a result, the student will be sufficiently confident to show his/her own voice .

Writing a consistent LR is an intense and complex activity that reveals the training and long-lasting academic skills of a writer. It is not a lonely or linear process. However, students are unlikely to be prepared to write an LR if they have not mastered the aforementioned domains ( 10 ). An institutional environment that supports student learning is crucial.

Different institutions employ distinct methods to promote students’ learning processes. First, many universities propose modules to develop behind the scenes activities that enhance self-reflection about general skills (e.g., the skills we have mastered and the skills we need to develop further), behaviors that should be incorporated (e.g., self-criticism about one’s own thoughts), and each student’s role in the advancement of his/her field. Lectures or workshops about LRs themselves are useful because they describe the purposes of the LR and how it fits into the whole picture of a student’s work. These activities may explain what type of discussion an LR must involve, the importance of defining the correct scope, the reasons to include a particular resource, and the main role of critical reading.

Some pedagogic services that promote a continuous improvement in study and academic skills are equally important. Examples include workshops about time management, the accomplishment of personal objectives, active learning, and foreign languages for nonnative speakers. Additionally, opportunities to converse with other students promotes an awareness of others’ experiences and difficulties. Ultimately, the supervisor’s role in providing feedback and setting deadlines is crucial in developing students’ abilities and in strengthening students’ writing quality ( 12 ).

HOW SHOULD A LITERATURE REVIEW BE DEVELOPED?

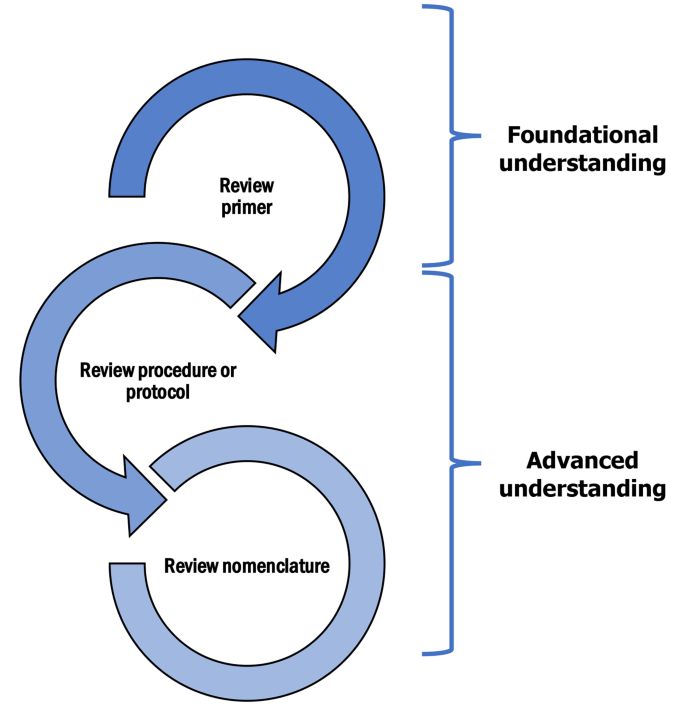

A consensus on the appropriate method for elaborating an LR is not available, but four main steps are generally accepted: defining the main topic, searching the literature, analyzing the results, and writing ( 6 ). We suggest a fifth step: reflecting on the information that has been written in previous publications ( Figure 2 ).

First step: Defining the main topic

Planning an LR is directly linked to the research main question of the thesis and occurs in parallel to students’ training in the three domains discussed above. The planning stage helps organize ideas, delimit the scope of the LR ( 11 ), and avoid the wasting of time in the process. Planning includes the following steps:

- Reflecting on the scope of the LR: postgraduate students will have assumptions about what material must be addressed and what information is not essential to an LR ( 13 , 18 ). Cooper’s Taxonomy of Literature Reviews 2 systematizes the writing process through six characteristics and nonmutually exclusive categories. The focus refers to the reviewer’s most important points of interest, while the goals concern what students want to achieve with the LR. The perspective assumes answers to the student’s own view of the LR and how he/she presents a particular issue. The coverage defines how comprehensive the student is in presenting the literature, and the organization determines the sequence of arguments. The audience is defined as the group for whom the LR is written.

- Designating sections and subsections: Headings and subheadings should be specific, explanatory and have a coherent sequence throughout the text ( 4 ). They simulate an inverted pyramid, with an increasing level of reflection and depth of argument.

- Identifying keywords: The relevant keywords for each LR section should be listed to guide the literature search. This list should mirror what Hart (1998) ( 3 ) advocates as subject vocabulary . The keywords will also be useful when the student is writing the LR since they guide the reader through the text.

- Delineating the time interval and language of documents to be retrieved in the second step. The most recently published documents should be considered, but relevant texts published before a predefined cutoff year can be included if they are classic documents in that field. Extra care should be employed when translating documents.

Second step: Searching the literature

The ability to gather adequate information from the literature must be addressed in postgraduate programs. Librarian support is important, particularly for accessing difficult texts. This step comprises the following components:

- Searching the literature itself: This process consists of defining which databases (electronic or dissertation/thesis repositories), official documents, and books will be searched and then actively conducting the search. Information literacy skills have a central role in this stage. While searching electronic databases, controlled vocabulary (e.g., Medical Subject Headings, or MeSH, for the PubMed database) or specific standardized syntax rules may need to be applied.

In addition, two other approaches are suggested. First, a review of the reference list of each document might be useful for identifying relevant publications to be included and important opinions to be assessed. This step is also relevant for referencing the original studies and leading authors in that field. Moreover, students can directly contact the experts on a particular topic to consult with them regarding their experience or use them as a source of additional unpublished documents.

Before submitting a dissertation/thesis, the electronic search strategy should be repeated. This process will ensure that the most recently published papers will be considered in the LR.

- Selecting documents for inclusion: Generally, the most recent literature will be included in the form of published peer-reviewed papers. Assess books and unpublished material, such as conference abstracts, academic texts and government reports, are also important to assess since the gray literature also offers valuable information. However, since these materials are not peer-reviewed, we recommend that they are carefully added to the LR.

This task is an important exercise in time management. First, students should read the title and abstract to understand whether that document suits their purposes, addresses the research question, and helps develop the topic of interest. Then, they should scan the full text, determine how it is structured, group it with similar documents, and verify whether other arguments might be considered ( 5 ).

Third step: Analyzing the results

Critical reading and thinking skills are important in this step. This step consists of the following components:

- Reading documents: The student may read various texts in depth according to LR sections and subsections ( defining the main topic ), which is not a passive activity ( 1 ). Some questions should be asked to practice critical analysis skills, as listed below. Is the research question evident and articulated with previous knowledge? What are the authors’ research goals and theoretical orientations, and how do they interact? Are the authors’ claims related to other scholars’ research? Do the authors consider different perspectives? Was the research project designed and conducted properly? Are the results and discussion plausible, and are they consistent with the research objectives and methodology? What are the strengths and limitations of this work? How do the authors support their findings? How does this work contribute to the current research topic? ( 1 , 19 )

- Taking notes: Students who systematically take notes on each document are more readily able to establish similarities or differences with other documents and to highlight personal observations. This approach reinforces the student’s ideas about the next step and helps develop his/her own academic voice ( 1 , 13 ). Voice recognition software ( 16 ), mind maps ( 5 ), flowcharts, tables, spreadsheets, personal comments on the referenced texts, and note-taking apps are all available tools for managing these observations, and the student him/herself should use the tool that best improves his/her learning. Additionally, when a student is considering submitting an LR to a peer-reviewed journal, notes should be taken on the activities performed in all five steps to ensure that they are able to be replicated.

Fourth step: Writing

The recognition of when a student is able and ready to write after a sufficient period of reading and thinking is likely a difficult task. Some students can produce a review in a single long work session. However, as discussed above, writing is not a linear process, and students do not need to write LRs according to a specific sequence of sections. Writing an LR is a time-consuming task, and some scholars believe that a period of at least six months is sufficient ( 6 ). An LR, and academic writing in general, expresses the writer’s proper thoughts, conclusions about others’ work ( 6 , 10 , 13 , 16 ), and decisions about methods to progress in the chosen field of knowledge. Thus, each student is expected to present a different learning and writing trajectory.

In this step, writing methods should be considered; then, editing, citing and correct referencing should complete this stage, at least temporarily. Freewriting techniques may be a good starting point for brainstorming ideas and improving the understanding of the information that has been read ( 1 ). Students should consider the following parameters when creating an agenda for writing the LR: two-hour writing blocks (at minimum), with prespecified tasks that are possible to complete in one section; short (minutes) and long breaks (days or weeks) to allow sufficient time for mental rest and reflection; and short- and long-term goals to motivate the writing itself ( 20 ). With increasing experience, this scheme can vary widely, and it is not a straightforward rule. Importantly, each discipline has a different way of writing ( 1 ), and each department has its own preferred styles for citations and references.

Fifth step: Reflecting on the writing

In this step, the postgraduate student should ask him/herself the same questions as in the analyzing the results step, which can take more time than anticipated. Ambiguities, repeated ideas, and a lack of coherence may not be noted when the student is immersed in the writing task for long periods. The whole effort will likely be a work in progress, and continuous refinements in the written material will occur once the writing process has begun.

LITERATURE REVIEW CHECKLIST

In contrast to review papers, the LR of a dissertation/thesis should not be a standalone piece or work. Instead, it should present the student as a scholar and should maintain the interest of the audience in how that dissertation/thesis will provide solutions for the current gaps in a particular field.

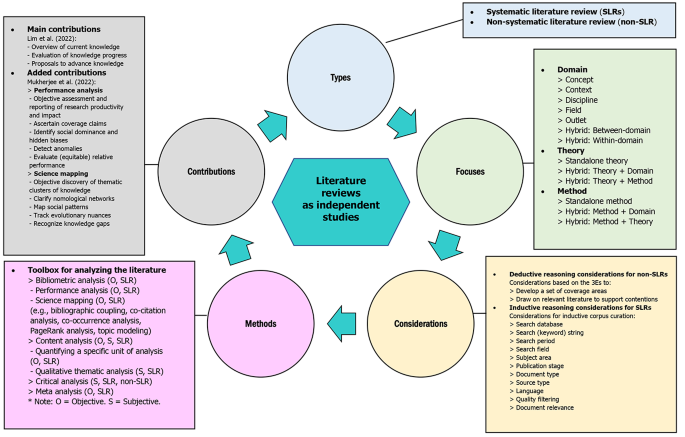

A checklist for evaluating an LR is convenient for students’ continuous academic development and research transparency: it clearly states the desired achievements for the LR of a dissertation/thesis. Here, we present an LR checklist developed from an LR scoring rubric ( 11 ). For a critical analysis of an LR, we maintain the five categories but offer twelve criteria that are not scaled ( Figure 3 ). The criteria all have the same importance and are not mutually exclusive.

First category: Coverage

1. justified criteria exist for the inclusion and exclusion of literature in the review.