Summary of Cubism

Cubism developed in the aftermath of Pablo Picasso's shocking 1907 Les Demoiselles d'Avignon in a period of rapid experimentation between Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque . Drawing upon Paul Cezanne’s emphasis on the underlying architecture of form, these artists used multiple vantage points to fracture images into geometric forms. Rather than modelled forms in an illusionistic space, figures were depicted as dynamic arrangements of volumes and planes where background and foreground merged. The movement was one of the most groundbreaking of the early-20 th century as it challenged Renaissance depictions of space, leading almost directly to experiments with non-representation by many different artists. Artists working in the Cubist style went on to incorporate elements of collage and popular culture into their paintings and to experiment with sculpture. A number of artists adopted Picasso and Braque's geometric faceting of objects and space including Fernand Léger and Juan Gris , along with others that formed a group known as the Salon Cubists .

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The artists abandoned perspective, which had been used to depict space since the Renaissance, and they also turned away from the realistic modeling of figures.

- Cubists explored open form, piercing figures and objects by letting the space flow through them, blending background into foreground, and showing objects from various angles. Some historians have argued that these innovations represent a response to the changing experience of space, movement, and time in the modern world. This first phase of the movement was called Analytic Cubism .

- In the second phase of Cubism, Synthetic Cubism practicioners explored the use of non-art materials as abstract signs. Their use of newspaper would lead later historians to argue that, instead of being concerned above all with form, the artists were also acutely aware of current events, particularly World War I.

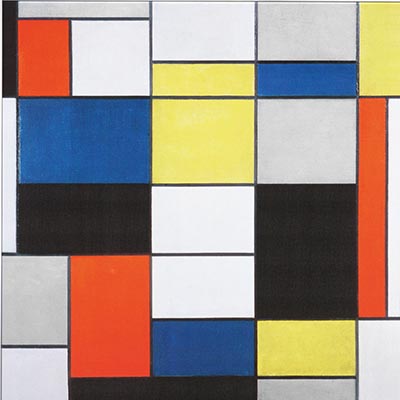

- Cubism paved the way for non-representational art by putting new emphasis on the unity between a depicted scene and the surface of the canvas. These experiments would be taken up by the likes of Piet Mondrian , who continued to explore their use of the grid, abstract system of signs, and shallow space.

Key Artists

Overview of Cubism

From 1907 to 1914 Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso worked so closely together, they dressed alike and joked that they were like the Wright brothers who invented the airplane - Picasso even called Braque "Wilbourg." Braque said, "The things that Picasso and I said to one another during those years will never be said again, and even if they were, no one would understand them anymore. It was like being roped together on a mountain," as the two spearheaded the development of the movement.

Artworks and Artists of Cubism

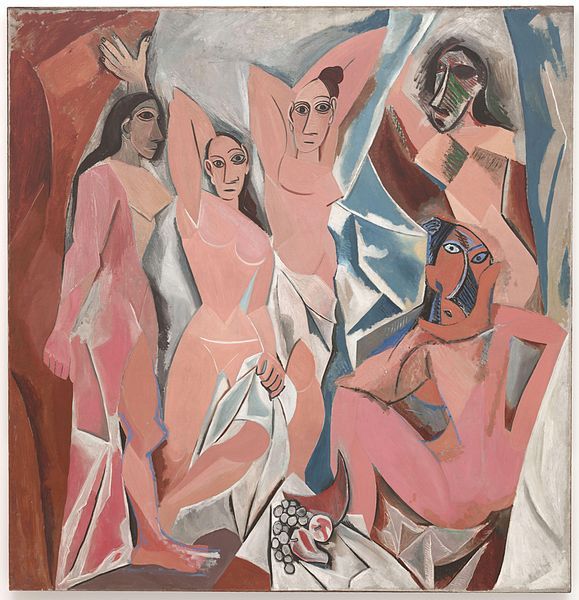

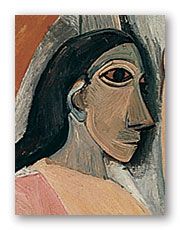

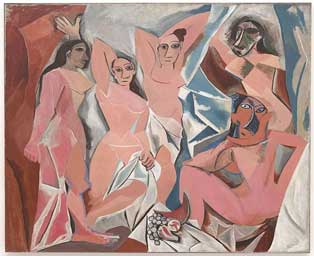

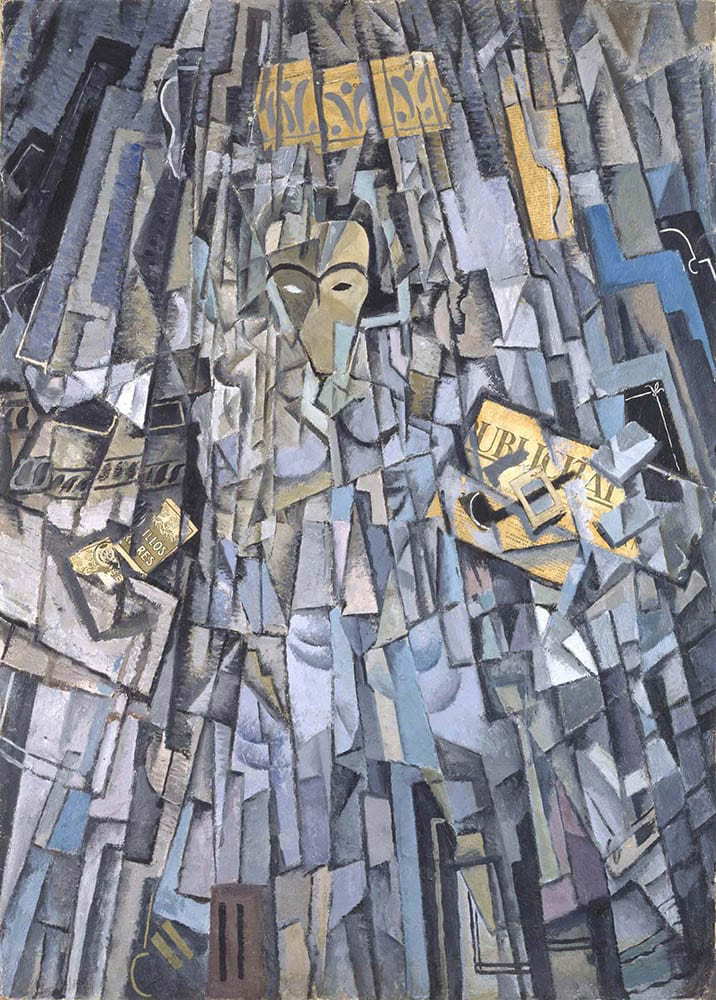

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon

Artist: Pablo Picasso

Picasso's painting was shocking even to his closest artist friends both for its content and for its formal experimentation. The subject matter of nude women was not in itself unusual, but the fact that Picasso painted the women as prostitutes in aggressively sexual postures was novel. Their blatant sexuality was heightened by Picasso's influence from non-Western art that is most evident in the faces of three of the women, which are rendered as mask-like, suggesting that their sexuality is not just aggressive, but also primitive. The unusual formal elements of the painting were also part of its shock value. Picasso abandoned the Renaissance illusion of three-dimensionality, instead presenting a radically flattened picture plane that is broken up into geometric shards. For instance, the body of the standing woman in the center is composed of angles and sharp edges. Both the cloth wrapped around her lower body and her body itself are given the same amount of attention as the negative space around them as if all are in the foreground and all are equally important. The painting was widely thought to be immoral when it was finally exhibited in public in 1916. Braque is one of the few artists who studied it intently in 1907, leading directly to his later collaboration with Picasso. Because it predicted some of the characteristics of Cubism, Les Demoiselles is considered proto or pre-Cubist.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Houses at L'Estaque

Artist: Georges Braque

In this painting, Braque shows the influence of Picasso's Les Demoiselles of the previous year and the work of Paul Cézanne. From Cézanne, he adapted the uni-directional, uniform brushwork, and flat spacing, while from Picasso he took the radical simplification of form and use of geometric shapes to define objects. There is, for example, no horizon line and no use of traditional shading to add depth to objects, so that the houses and the landscape all seem to overlap and to occupy the foreground of the picture plane. As a whole, this work made obvious his allegiance to Picasso's experiments and led to their collaboration.

Oil on Canvas - Hermann and Margrit Rupf Foundation, Bern

Violin and Palette

By 1909, Picasso and Braque were collaborating, painting largely interior scenes that included references to music, such as musical instruments or sheet music. In this early example of Analytic Cubism, Braque was experimenting further with shallow spacing by reducing the color palette to neutral browns and grays that further flatten out the space. The piece is also indicative of Braque's attempts to show the same item from different points of view. Some shading is used to create an impression of bas-relief with the various geometric shapes seeming to overlap slightly. Musical instruments such as guitars, violins, and clarinets show up frequently in Cubist paintings, particularly in the works of Braque who trained as a musician. By relying on such repeated subject matter, the works also encourage the viewer to concentrate on the stylistic innovations of Cubism rather than on the specificity of the subject matter.

Oil on Canvas - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

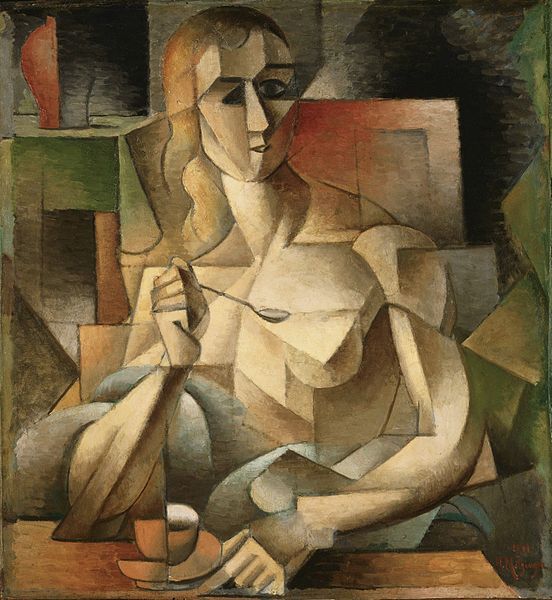

Artist: Jean Metzinger

When this painting was shown at the 1911 Salon d'Automne, the critic Andre Salmon dubbed it "The Mona Lisa of Cubism." While Picasso and Braque were dematerializing figures and objects in their works, Metzinger remained committed to legibility, reconciling modernity with classicism, thus Salmon's nickname for the work. Despite the realism of the painting, like other Cubists, Metzinger abandons the single point of view in use since the Renaissance. The female figure and the still life elements are shown from differing angles as if the artist had physically moved around the subject to capture it from different points of view at successive moments in time. The teacup is shown in both profile and from above, while the figure of the centrally positioned woman is shown both straight on and in profile. The painting was reproduced in Metzinger and Gleizes's book Du Cubisme (1912) and in Apollinaire's The Cubist Painters (1913). The work became better known at the time than any work by Picasso or Braque who had removed themselves from the public by not exhibiting at the Salon. For most people in the 1910s, Cubism was associated with artists like Metzinger, rather than its originators Picasso or Braque.

Oil on Cardboard - The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Picasso ups the ante in this work, pushing his experiments in new directions. Building on the overlapping, geometric shapes, Picasso moves further away from the Renaissance illusion of three-dimensionality and towards abstraction by reducing color and by increasing the illusion of low-relief sculpture even further than Braque did in Violin and Palette . Most significantly, however, Picasso included painted words on the canvas. The words, "ma jolie" not only flatten the space further, but they also liken the painting to a poster because they are painted in a font reminiscent of that used in advertising. This is the first time that an artist had so blatantly used elements of popular culture in a work of high art. This melding of high and low culture may have been influenced by the late-19 th -century posters of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Though they were made as advertisements for various entertainment venues, Toulouse-Lautrec's posters were appreciated as high art, perhaps because he was himself also a painter. Further linking Picasso's work to pop culture and to the everyday, "Ma Jolie" was also the name of a popular tune at the time as well as Picasso's nickname for his girlfriend.

Oil on Canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Still Life with Chair Caning

By 1912, Picasso and Braque had exhausted their experiments with monochromatic color and with the illusion of low-relief sculpture across the surface of the canvas. In Still Life with Chair Caning , Picasso reintroduces color and goes further into experimentation with multiple perspectives. The image depicts a tabletop at a café; Picasso shows various objects on the table from multiple points of view including the knife, pieces of fruit, and wine glass that are in the top right of the image. Combining both paint and collage, Picasso also incorporates a piece of oilcloth (a cheap tablecloth) that resembles chair caning to reference to the type of seating common in a traditional café. The work is playful in that Picasso conveys the transparent quality of the tabletop by making it appear as if the caning of the chair can be seen through the glass. The spacing in the image, however, is even flatter than in previous works with no shading of objects, thus the café table is not depicted illusionistically as if in three dimensions, but conceptually. Finally, Picasso paints the words "JOU" that are both the first three letters of the French word for newspaper (Journal), thus referring both to the act of reading a newspaper at a café (the folded newspaper itself can be seen on the left), and also spell the first letters of the French word for "play", signifying the playfulness and experimental quality of the image. Not only is this the first time that collaged elements were included in a work of high art, but it has been argued that the bits of collaged newspaper reference the unstable political situation in Europe and perhaps Picasso's own anarchist tendencies. Even though this work is now synonymous with Cubist experiments, it was seen by few people at the time because Picasso did not show his works at public exhibits, but rather displayed his ideas to like-minded (avant-garde) collaborators.

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery, London

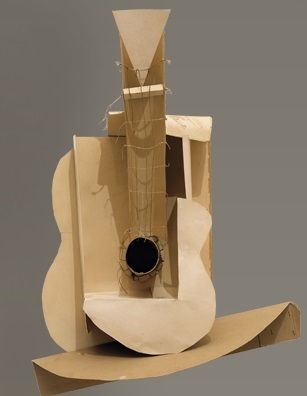

Maquette for Guitar

Picasso's experiments with collaged elements encouraged him to reconsider sculpture as well. Rather than a collage, however, Maquette for Guitar is an assemblage (or three-dimensional collage). While traditional sculpture was made up of a mass (or solid) surrounded by a void, using a material such as wood or marble that was then shaped by the hand of the artist, Picasso here takes pieces of cardboard, paper, string, and wire that he then folded, threaded, and glued together. This is the first time that a sculpture had been assembled from disparate parts. Rather than being a solid material, it fluidly integrates mass and its surrounding void. Picasso translated the Cubist interest in multiple perspectives and geometric form into a three-dimensional medium. The work is also groundbreaking in the history of 20 th -century sculpture in part because of Picasso's use of non-art materials that, like Ma Jolie , challenge the distinction between high art and popular culture.

Paperboard, paper, thread, string, twine, and coated wire - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Conquest of the Air

Artist: Roger de la Fresnaye

La Fresnaye's colorful and optimistic paintings did much to popularize Cubism before World War I. In The Conquest of Air , his most famous work, he depicts himself with his brother Henri, sitting at a table outdoors. The yellow hot-air balloon in the distant background likely refers to the oldest balloon race in the world, the Gordon Bennett cup, which took place annually from 1906 to 1938, with breaks during the war years. The race alternated between European cities, but was held first in Paris in 1906 and again in 1913. A French crew won the race in 1912, adding to their national honor in this arena as the French had invented the hot-air balloon in 1783, no doubt explaining the celebratory French flag in the painting. La Fresnaye's work shows influence from both traditional Cubism in its use of geometrical forms and also from Delaunay's Orphism in its bright color and use of the circle. He was a member of La Section d'Or Cubists from 1912-1914, but after the war became a well-known proponent of more traditional realism.

Oil on Canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York (Not on Display)

Electric Prisms

Artist: Sonia Delaunay

Robert and Sonia Delaunay exhibited with the Salon Cubists, and later founded the Orphism movement that was heavily influenced by Cubism. Like all Cubists, they used geometric forms and flattened perspective to show visual manipulation of their subject, but the Delaunays in particular had metaphysical interests in color and concept, often overlapping multiple scenes and views to suggest a fourth dimension. This multiplicity of scenes (or so-called theory of simultaneity) proposed that events and objects are "inextricably connected in time and space." Electric Prisms uses the sphere to represent this idea of overlap. In the work, different spheres convene into large concentric circles that are arranged to depict dynamic movement of electricity. Orphism was a short-lived movement but was a key phase in the transition from Cubism to non-representational art.

Oil on canvas - Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

Still Life with Open Window, Rue Ravignan

Artist: Juan Gris

Of the Salon Cubists, Juan Gris' work is often considered closest to that of Picasso and Braque with whom Gris was in close contact beginning in 1911. By 1914, Gris had developed collage techniques in which he pasted elements from newspapers and magazines onto deconstructed, abstract scenes. His works were sometimes actual collages, but could also be paintings that resembled collages as in Still Life with Open Window . In this work Gris combined interior and exterior views through interlocking elements and subtle shifts in color, including an intense blue that suffuses the work and, like Synthetic Cubism, reintroduces color to the Cubist style. A still life in the foreground features traditional elements such as a book, a carafe, and a bottle of wine on an upturned tabletop. These objects are refracted through shafts of colored light from the open window that bring the neighboring houses and trees into the composition; the interior electric light contrasts with the moonlit scene outside the window. Gris's compositions were more calculating than those of other Cubists. Every element of the grid-like composition was refined to produce an interlocking arrangement without unnecessary detail. Within the grid, Gris balances different areas of the work: light to dark, monochrome to color, and lamplight inside the room to moonlight outside. The viewer has a sense of the still life as it exists in its surroundings.

Oil on canvas - National Gallery, Washington DC

Three Women

Artist: Fernand Léger

In Three Women , Léger updates the traditional theme of the reclining nude into a modern vocabulary that combines his various influences from Cubism and Futurism. The geometric forms of the figures indicate his Cubist sources, while his reliance on machine-like imagery is borrowed from Futurism. His pristine and colorful geometric forms are, however, much different from the faux low-relief sculptural effects used in Analytic Cubism. The shapes that make up the figures and objects, for example, do not overlap in the foreground, but are used to create an illusion of three-dimensionality. Thus, the furniture, the bodies of the women, and the spaces between them are easily distinguished. Léger's polished forms can be tied to the interest in classicism or "return to order" that was widespread in French art after the chaos of World War I. The machine-like precision and solidity of the objects and figures suggest Léger's faith in the modern world and the hope that technological advances and the machine age would together remake the world. Léger was badly injured in WWI, yet nevertheless presents a cheerful scene that relies on primary colors to convey his positive mindset about the benefits of modernity and technology, ultimately expressing his faith in the future.

Beginnings of Cubism

A watershed moment for the development of Cubism was the posthumous retrospective of Paul Cézanne's work at the Salon d'Automne in 1907. Cézanne's use of generic forms to simplify nature was incredibly influential to both Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque . In the previous year, Picasso was also introduced to non-Western art: seeing Iberian art in Spain, and African-influenced art by Matisse , and at the Trocadero anthropological museum. What drew Picasso to these artistic traditions was their use of an abstract or simplified representation of the human body rather than the naturalistic forms of the European Renaissance tradition.

The Breakthrough: Les Demoiselles d'Avignon

These varying influences can be seen in Picasso's groundbreaking work of 1907, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon , which is considered a work of proto or pre-Cubism. In its radical distortion of figures, its rendering of volumes as fragmented planes, and its subdued palette, this work predicted some of the key characteristics of later Cubism.

Braque, on seeing Picasso's Les Demoiselles at his studio, intensified his similar explorations in simplification of form. He made a series of landscape paintings in the summer of 1908, including Houses at L'Estaque in which trees and mountains were rendered as shaded cubes and pyramids, resembling architectural forms. Cubism was introduced to the public with Braque's one-man exhibition at Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler's gallery on the rue Vignon in November 1908. It was this exhibit that led French art critic Louis Vauxcelles to describe them as "bizarreries cubiques," thus giving the movement its name.

The experiments of Picasso and Braque owe much to Kahnweiler, who was the major supporter of their work. Picasso and Braque were both quite poor in 1907 and Kahnweiler offered to buy their works as they painted them, thus freeing the artists from worrying about pleasing patrons or receiving negative reviews. After the 1908 exhibit, with few exceptions, the two artists exhibited only in Kahnweiler's gallery.

The Cubism of Picasso and Braque

The close collaboration between Picasso and Braque beginning in 1909 was crucial to the style's genesis. The two artists met regularly to discuss their progress, and at times it became hard to distinguish the work of one artist from another (as they liked it). Both were living in the bohemian Montmartre section of Paris in the years before and during World War I, making their collaboration easy.

In 1912, Kahnweiler gave his first public interview on Cubism, no doubt in response to growing public interest in (and some recognition of) the movement. When World War I began, Kahnweiler, as a German, was exiled from France. During the war, Léonce Rosenberg became the main dealer for Cubist art in Paris (including those of the Salon Cubists) with his brother Paul Rosenberg serving as Picasso's dealer during the interwar years.

Though Picasso and Braque returned to Cubist forms periodically throughout their careers and there were some exhibitions of work up until 1925, the two-man movement did not last much beyond World War I.

Salon or Section d'Or Cubism

The Salon Cubists , so-called because they showed their works at public exhibits such as the Salon d'Automne, did not work closely with Picasso and Braque but were influenced by their experiments. It was through the work of the Salon Cubists that the movement became widely known to the public in the early 1910s. These artists included Robert Delaunay , Albert Gleizes, Fernand Léger , Juan Gris , Henri Le Fauconnier, Roger de La Fresnaye, and Jean Metzinger. Metzinger and Delaunay, who had been friends at least since 1906, began collaborating with Gleizes as a result of the yearly Salon d'Automne. It was through Gleizes that they met Le Fauconnier who had published Note sur la peinture (1910) in which he praised Picasso and Braque for their "total emancipation" of painting.

These artists exhibited together at the 1911 Salon des Independants, introducing Cubism to the general public. The Independants was a non-juried exhibition where public reaction depended on how and where paintings were hung. The Cubists got control of the hanging committee from the Neo-Impressionists so that their works could be hung together in one room as a coherent school. The paintings created a stir, as Gleizes noted: "While the newspapers sounded the alarm to alert people to the danger, and while appeals were made to the public authorities to do something about it, song writers, satirists and other men of wit and spirit provoked great pleasure among the leisured classes by playing with the word 'cube', discovering that it was a very suitable vehicle for inducing laughter which, as we all know, is the principle characteristic that distinguishes man from the animals."

In addition to showing their works in large exhibitions, the Salon Cubists were also distinct from Picasso and Braque in that they often worked on a large scale, leading one art historian to coin the term 'Epic Cubism' to distinguish their work from the more intimate paintings of Picasso and Braque. While they broke apart objects and bodies into geometric forms like those of Picasso and Braque, the Salon Cubists did not challenge Renaissance conceptions of space to the same extent nor did they embrace the monochromatic color of Analytic Cubism or the collage elements of Synthetic Cubism .

At the end of 1911 Gleizes and Metzinger, who lived closely together in the Parisian suburbs, and others in the group began meeting in Puteaux, a suburb where the painter and engraver Jacques Villon and his brother, the sculptor Raymond Duchamp-Villon had their studios (leading to them sometimes being called the Puteaux group). It is likely as a result of these meetings that the main ideas for Metzinger and Gleizes' On Cubism (1912) were formalized; it was the first published statement about the style.

The next year the group also planned the launch of the Salon de la Section d'Or (1912) that would bring together the most radical currents in painting. The term Section d'Or was a name the Salon Cubists adopted to show their attachment to the golden mean, i.e. the belief in order and the importance of mathematical proportions in their works that reflected those in nature. The Section d'Or exhibit was held after the 1912 Salon d'Automne at the Galerie La Boetie. It was at this exhibit that the poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire coined the term Orphism to refer to the work of Delaunay. The next year Apollinaire published Aesthetic Meditations: The Cubist Painters (1913). These many exhibits and publications were calculated to make an impact, both in Paris and abroad.

As with the Cubism of Picasso and Braque, the Salon or Section d'Or group did not continue coherently after WWI, having only sporadic exhibits between 1918 and 1925.

Cubism: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

The various stages of development in the Cubist style are based on the work of Picasso and Braque rather than on those of the Salon Cubists. The exact names and dates of the stages are debated and continually reframed to this day.

Early Cubism (1908-09)

This early phase of the movement came in the wake of the Paul Cézanne retrospective in 1907 when many artists were reintroduced or introduced for the first time to the work of Cézanne, who had been living in Aix-en-Provence in the south of France before his death and had not exhibited in Paris for many years. Several artists who saw the retrospective were influenced by his lack of three-dimensionality, the material quality of his brushwork, and his use of uniform brushstrokes. Braque's Houses at L'Estaque (1908) is a good example of this type of Cubism.

Analytic Cubism (1910-12)

In this phase, Cubism developed in a highly systematic fashion. Later to be known as the Analytic period of the style, it was based on close observation of objects in their background contexts, often showing them from various vantage points. Picasso and Braque restricted their subject matter to the traditional genres of portraiture and still life and also limited their palette to earth tones and muted grays in order to lessen the clarity between the fragmented shapes of figures and objects. Although their works were often similar in appearance, their separate interests showed through over time. Braque tended to show objects exploding out or pulled apart into fragments, while Picasso rendered them magnetized, with attracting forces compelling elements of the pictorial space into the center of the composition. Works in this style include Braque's Violin and Palette (1909) and Picasso's Ma Jolie (1911-12).

Towards the end of this stage of Cubism, Juan Gris began to make contributions to the style: he maintained a sharp clarity to his forms, provided suggestions of a compositional grid, and introduced more color to what had been an austere, monochromatic style.

Synthetic Cubism (1912-14)

In 1912 both Picasso and Braque began to introduce foreign elements into their compositions, continuing their experiments with multiple perspectives. Picasso incorporated wall paper that imitated chair caning into Still Life with Chair-Caning (1912), thus initiating Cubist collage, and Braque began to glue newspaper to his canvases, beginning the movement's exploration of papier-colle . In part this may have resulted from the artists' growing discomfort with the radical abstraction of Analytic Cubism, though it could also be argued that these Synthetic experiments touched off an even more radical turn away from Renaissance depictions of space, and towards a more conceptual rendering of objects and figures. Picasso's experiments with sculpture are also included as part of the Synthetic Cubist style as they employ collaged elements.

Crystal Cubism (1915-22)

As a response to the chaos of war, there was a tendency among many French artists to pull back from radical experimentation; this inclination was not unique to Cubism. One art historian has described this stage of Cubism as the "end product of a progressive closing down of possibilities." In Léger's Three Women (1921), for example, the depicted subjects are hard-edged rather than resembling overlapping bits of low-relief sculpture; Léger also did not attempt to show objects from various angles. Crystal Cubism is associated with Salon Cubism as well as with the works of Picasso and Braque. Crystal Cubism is part of the larger trend known as a Return to Order (also known as Interwar Classicism) that was associated with artists in the School of Paris.

Later Developments - After Cubism

Cubism spread quickly throughout Europe in the 1910s, as much because of its systematic approach to rendering imagery as for the openness it offered in depicting objects in new ways. Critics were split over whether Cubists were concerned with representing imagery in a more objective manner - revealing more of its essential character - or whether they were principally interested in distortion and abstraction.

The movement lies at the root of a host of early-20 th century styles including Constructivism , Futurism , Suprematism , Orphism , and De Stijl . Many important artists went through a Cubist phase in their development, perhaps the most notable of whom was Marcel Duchamp whose notorious Nude Descending a Staircase (1912) garnered much attention and many negative reviews at the 1913 Armory Show in New York City.

The ideas in the movement also fed into more popular phenomena, like Art Deco design and architecture. Later movements such as Minimalism were also influenced by the Cubist use of the grid, and it is difficult to imagine the development of non-representational art without the experiments of the Cubists. Like other paradigm changing artistic movements of 20 th -century art, like Dada and Pop , Cubism shook the foundations of traditional artmaking by turning the Renaissance tradition on its head and changing the course of art history with reverberations that continue into the postmodern era.

Useful Resources on Cubism

- The Cubist Painters (Documents of Twentieth-Century Art) Our Pick By Guillaume Apollinaire

- Cubism A&I (Art and Ideas) By Neil Cox

- Picasso and the Invention of Cubism Our Pick By Mr. Pepe Karmel

- A Cubism Reader: Documents and Criticism, 1906-1914 By Mark Antliff, Patricia Leighten

- Cubism: Colour Library (Phaidon Colour Library) By Philip Cooper

- Architecture and Cubism (Centre Canadien d'Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture) By Eve Blau

- Picasso, Braque, and Early Film in Cubism By Tom Gunning

- The Czech Cubism Foundation

- Review of "Picasso: Guitars 1912-1914" at MoMA By Tyler Green / ARTINFO.com / March 23, 2011

- Art in Review; 'Inheriting Cubism' By Ken Johnson / The New York Times / December 7, 2001

- Picasso and Braque, Brothers in Cubism Our Pick By Michael Brenson / The New York Times / September 22, 1989

- Art: The Apprenticeship Of Stuart Davis as a Cubist By Roberta Smith / The New York Times / November 27, 1987

- "Cubism" is the title of a live concert film, from 2007, by the English electronic group The Pet Shop Boys

Similar Art

Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913)

Composition A (1920)

Related artists, related movements & topics.

Content compiled and written by The Art Story Contributors

Edited and published by The Art Story Contributors

Easy Cubism Art Project

Cubism is one of my favorite art genres to teach. Because of the influences of contemporary artists (think Romero Britto), children are familiar with how artists transforms everyday objects into geometric shapes, which is a huge hit with this easy cubism art project.

The earlier influences of cubism (Picasso, Klee, Cézanne and Braque) are just as fun and colorful. When I taught my Cubist-Inspired Picasso lesson to Kinders, I drew a fish, cut the fish into sections and shapes. Then, as a group, we put the fish together again in a new and different way. This exercise was really fun and emphasized the concept of abstraction (to take apart) and ultimately cubism.

My Easy Cubism Activities utilize the same concept: draw a familiar object then divide into shapes and lines. My third graders loved this project and although the instructions are the same, each child produced wildly different pieces.

I used Prismacolor markers for this project and are absolutely lovely. The colors are rich and heavy. Using card stock instead of sulfite paper makes coloring a pleasure. I read that using photo paper is a dream to use with markers so if you have a ream of that laying around, try it out!

Teach art from a cart? Learn why this lesson is a great choice by downloading this free checklist and lesson guide!

What do you think? Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Leave a comment

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Is there a literature book you would recommend to go along with this “easy cubism” lesson? I love how some of your art lessons include reading of a literature book 🙂 Susan

Hi Susan, Great question. You could tie in a book on Picasso or Klee. Laurence Anholt’s The Girl with the Ponytail is and especially good one for cubism.

Does this packet include a picture to color THEN CUT and put back together? I love the fish you did in the beginning, simple enough for my first graders.

Hi Amanda, The package includes two print outs of the same object: one plain and one patterned coloring page. There are a few options to create your own cubist projects. You can color and cut if you wish. Patty

I’m trying to download this, it doesn’t seem to work

It’s in the ART THROUGH THE AGES bundle

Hi, i am very much interested to learn cubism. Mat i know if you have an on-line class on this subject? If you do, may i know how much. Thank you very much.

We have an enrollment right now for The Sparklers Club. Check it out! https://pages.deepspacesparkle.com/the-sparklers-club/

You are so good at this

In stores 8/21

- PRIVACY POLICY & TERMS OF SERVICE

Deep Space Sparkle, 2024

The {lesson_title} Lesson is Locked inside of the {bundle_title}

Unlocking this lesson will give you access to the entire bundle and use {points} of your available unlocks., are you sure, the {bundle_title} is locked, accessing this bundle will use {points} of your available unlocks., to unlock this lesson, close this box, then click on the “lock” icon..

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Modernisms 1900-1980

Course: modernisms 1900-1980 > unit 3.

- Cubist Sculpture II

- The Case for Abstraction

- Picasso's Early Work

- Picasso, Portrait of Gertrude Stein

- Pablo Picasso, Gertrude Stein

- Picasso, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon

- Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon

- Pablo Picasso, Three Women

Inventing Cubism

- Cubism and multiple perspectives

- Synthetic Cubism, Part I

- Synthetic Cubism, Part II

- Salon Cubism

- Pablo Picasso and the new language of Cubism

- Braque, The Viaduct at L'Estaque

- Picasso, The Reservoir, Horta de Ebro

- Georges Braque, Violin and Palette

- Braque, The Portuguese

- Cubist Sculpture I

- Picasso, Guitar

- Picasso, Still Life with Chair Caning

- Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler

- Pablo Picasso, The Three Musicians

- Pablo Picasso, Guitar, Glass, and Bottle

- Conservation | Picasso's Guitars

- Picasso, Guernica

- Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso: Two Cubist Musicians

- Fernand Léger, "Contrast of Forms"

- Robert Delaunay, "Simultaneous Contrasts: Sun and Moon"

- The Cubist City – Robert Delaunay and Fernand Léger

- Juan Gris, The Table

- Cubism and its impact

A New Perspective

It [Cézanne's impact] was more than an influence, it was an invitation. Cézanne was the first to have broken away from erudite, mechanized perspective…[1]

Brothers of Invention

Want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Look Closer

All about cubism

Discover the radical 20th century art movement. This resource introduces cubist artists, ideas and techniques and provides discussion and activities.

Pablo Picasso Bottle of Vieux Marc, Glass, Guitar and Newspaper (1913) Tate

© Succession Picasso/DACS 2024

What is cubism and why was it so radical?

In around 1907 two artists living in Paris called Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque developed a revolutionary new style of painting which transformed everyday objects, landscapes, and people into geometric shapes. In 1908 art critic Louis Vauxcelles, saw some landscape paintings by Georges Braque (similar to the picture shown above) in an exhibition in Paris, and described them as ‘bizarreries cubiques’ which translates as ‘cubist oddities’ – and the term cubism was coined.

By comparing a cubist still life with an earlier still life painted using a more traditional approach, we can see immediately just what it is that made cubism look so radically different from earlier painting styles. Both paintings are of musical instruments. The first is by Edward Collier and was painted in the seventeenth century. The second is by cubist Georges Braque.

Edward Collier Still Life with a Volume of Wither’s ‘Emblemes’ (1696) Tate

Georges Braque Mandora (1909–10) Tate

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2024

Compare the way the instruments are painted in the paintings. Which look the most real? How has Collier made the objects in his painting look realistic? (Look at how he has used shading or tone , colour, perspective and also how he has applied the paint). What rules do you think the cubists broke?

Collier's Still Life looks realistic because...

- His use of colour to help us recognise the objects. A golden brown colour suggests the wood of the stringed instruments and table; the book and sheet music are black (ink) and white (paper); the grapes are a lush dark purple; and he has even cleverly recreated the metallic surface of the two-handled bowl using dark greys and whites

- His use of light and dark tones (shadows and highlights) to suggest the three-dimensional quality of the objects. Look at the side of the stringed instrument at the front of the painting. Light reflects off the raised surface closest to us, but as this curves away from us, the tone used is darker to suggest that it is more in shadow.The background is a shadowy dark space behind the table

- His use of perspective to create the impression of a real space with objects in the foreground looking bigger and clearer and objects behind looking smaller and less clear.

Braque's Mandora is different because...

- Although the shape of the mandora (a stringed instrument similar to a lute) is fairly clear, and if we look closely we can make out a bottle behind it, there is very little difference between the way Braque has painted the objects and the space around them. He has fragmented the whole image into tiny flat geometric shapes so the edges of the objects are less clear

- He has not used realistic colours for the different objects in the painting, instead he has used the same small range of muted colours – black, greys, ochres and earthy greens – for all the objects (no matter what they are) and the background

- He has not used perspective, or tone (light and shadow) to create the illusion of three-dimensional space or three-dimensional objects. Although there are lighter and darker tones within the painting, and these do sometimes create the appearance of three-dimensions (a dark tone is used for the side of the mandora making it look like a solid object); the tone is not always used in this way and sometimes seems confusing. The mandora, the objects behind it, and the background all seem to sit on the same level – on the flat surface of the picture, with no foreground or background, and no illusion of receding space.

Meet the cubists

Brassaï, photo of Picasso in his studio at 23 rue La Boétie, standing in front of Rousseau’s Portrait of a Woman 1932. Musée Picasso © ESTATE BRASSAÏ -R.M.N.

Georges Braque , London 1946 (inner pages) from Tate Publishing

In 1907 Georges Braque visited Pablo Picasso’s studio. This studio visit marked the beginning of one of the most important friendships in the history of art. Over the next few months and years the two artists shared their ideas, scrutinized each other’s work, challenged and encouraged each other. At some stage in around 1907 or 1908 they invented an exciting new style of painting – cubism . Their close working relationship at that time was later described by Georges Braque:

The things that Picasso and I said to one another during those years will never be said again, and even if they were, no one would understand them anymore. It was like being roped together on a mountain

Picasso and Braque were soon joined in their art adventure by other artists who were experimenting with different ways of depicting the world around them. Artists such as Juan Gris , Albert Gleizes , Jean Metzinger and Robert Delaunay who all worked in a cubist style.

Cubism explained

Georges Braque Bottle and Fishes (c.1910–12) Tate

Cubism looks very different to lots of other styles of painting. How does it work? What were Braque and Picasso's reasons for turning their back on traditional techniques? How did the cubists develop their new style?

The illusion of space

Since the Renaissance in the fifteenth century, European artists had aimed to create the illusion of three-dimensional space in their drawings and paintings. They wanted the experience of looking at a painting to be like looking through a window onto a real landscape, interior, person or object.

How do you make things look three-dimensional on a two-dimensional surface? Techniques such as linear perspective and tonal gradation are used. Perspective involves making things look bigger and clearer when they are close up, and smaller and less clear when they are further away. By doing this you can create the illusion of space. Artists also use tones (shadows) to create the illusion of three-dimensional objects. By gradually changing the darkness of a shadow, you can make something look solid.

These drawings by J.M.W Turner show how perspective and tone (or shadow) can be used to create the illusion of real, solid three-dimensional objects.

Joseph Mallord William Turner Lecture Diagram 42: Perspective Construction of a Tuscan Entablature (c.1810) Tate

Joseph Mallord William Turner Lecture Diagram 70: A Ruined Amphitheatre (c.1810) Tate

A new reality

The cubists however, felt that this type of illusion is trickery and does not give a real experience of the object.

Their aim was to show things as they really are, not just to show what they look like. They felt that they could give the viewer a more accurate understanding of an object, landscape or person by showing it from different angles or viewpoints, so they used flat geometric shapes to represent the different sides and angles of the objects. By doing this, they could suggest three-dimensional qualities and structure without using techniques such as perspective and shading.

This breaking down of the real world into flat geometric shapes also emphasized the two-dimensional flatness of the canvas. This suited the cubists’ belief that a painting should not pretend to be like a window onto a realistic scene but as a flat surface it should behave like one.

Look at this painting by Georges Braque of a glass on a table. Can you spot the techniques he has used to emphasize the flatness of the picture, but at the same time, made the objects look solid?

Georges Braque Glass on a Table (1909–10) Tate

The phases of cubism: Analytical vs synthetic

Cubism can be split into two distinct phases. The first phase, analytical cubism , is considered to have run until around 1912. It looks more austere or serious. Objects are split into lots of flat shapes representing the views of them from different angles, and muted colours and darker tones or shades are used. The second phase, synthetic cubism , involves simpler shapes and brighter colours (and looks more light-hearted and fun!)

Practical activities

David Hockney Caribbean Tea Time (1987) Tate

© David Hockney

Use these activity suggestions to explore ideas and create a cubist masterpiece updated for the twenty-first century.

Activity 1: Research influences

Paul Cézanne The Grounds of the Château Noir c.1900–6 Lent by the National Gallery 1997

Carved wooden female figure (minsereh) Mende, probably late 19th century AD, From Sierra Leone Trustees of the British Museum

There were two key influences on the development of cubist style: the paintings of Paul Cézanne and sculptures created by non-European artists. Use these activities to explore these two artistic approaches

Cézanne’s approach

Braque and Picasso greatly admired Paul Cézanne . Cézanne’s paintings of figures and landscapes are made up of small planes (flat shapes) and repeated brush strokes. They often seem to be painted from slightly different viewpoints. It is this influence that we can see in the work of the cubists.

If you look at Cézanne’s painting of trees and rocks in the grounds of the Château Noir, the surface seems to vibrate with a mesh of tiny interlocking planes.

- Select a small section of the image and copy it, enlarging it so that it fills your page

- Use paint, crayons or pastels to copy the marks and colours

Sculptures from non-European cultures

Picasso and Braque were amazed by the sculptures they saw in the Trocadero museum in Paris. Picasso described sculptures from French Polynesia and Africa as ‘the most powerful and most beautiful things the human imagination has ever produced’.

Look closely at the sculpture above. Think about the following and make notes in your sketchbook

- Where is it from?

- How big do you think it is?

- Is it realistic?

- Has the sculptor simplified the figure?

- Do parts of it seem exaggerated or emphasised?

- What does the sculpture make you think and feel?

- What do you think the sculpture was originally made for?

Create a portrait using sculptures from non-European cultures as your inspiration. This can be a self-portrait or a portrait of someone else.

- Use your notes about the sculpture you chose from the slideshow above to help you with approach and technique

- How has the sculptor simplified and exaggerated the forms. What effect does this have on your response to the work?

- Can you create a similar effect in your portrait?

Activity 2: Investigate viewpoints

The cubists wanted to show the whole structure of objects in their paintings without using techniques such as perspective or graded shading to make them look realistic. They wanted to show things as they really are – not just to show what they look like. They did this by:

- Emphasizing the flatness of the picture surface by breaking objects down into geometric shapes

- Depicting objects from lots of different angles. In this way they could suggest the three-dimensional quality of objects without making them look realistic.

Create a simple still life using the cubist technique of multiple viewpoints

- Choose three simple objects and group them together (e.g. trainer, mobile phone, apple, headphones, soft-drink can)

- Sketch or photograph the group of objects from four different viewpoints. (Viewpoints could include from the front, from above, from each side, from close-up, from far away…)

- Cut up each sketch or photograph into eight sections

- Choose two sections from each original sketch / photograph and put them together to form one image .

If you have access to picture editing software you can use this to create your picture. Use the tips below:

- Photograph your still life from four different viewpoints and save these images

- Select a small section from each photograph using the square marquee tool

- Open a new image and paste two sections from each original photograph to form your different viewpoint still life.

Activity 3: Explore shape, pattern, and texture

Juan Gris The Sunblind (1914) Tate

Pablo Picasso Bowl of Fruit, Violin and Bottle (1914) Lent by the National Gallery 1997

Juan Gris Bottle of Rum and Newspaper (1913–14) Tate

From around 1912 Braque , Picasso , and other artists working in a cubist style such as Juan Gris , started to use simpler shapes and lines and brighter colours in their artworks. They also began to add textures and patterns to their work, often collaging newspaper or other patterned paper directly into their paintings. This approach was called synthetic cubism. Browse the slideshow to remind yourself what it looks like.

Create a still life in the synthetic cubist style that explores shape, pattern and texture. Use the three objects you selected earlier, but this time use only flat shapes, simple lines and patterns to depict them in a still life. Here are some ideas.

- You could draw a simple outline of the objects onto brightly coloured or patterned sheets of paper such as newspaper or wrapping paper. Cut these shapes out and collage them into your still life

- Think about the negative shapes (the shapes left in the paper once you have cut your object out of it). Could you add these to your still life?

- Look at the shadows made by the objects. How can you make these shadow shapes part of the work?

- If your objects include text or numbers (such as the title of a book or a brand name on trainers), use numbers or letters cut from a magazine or newspaper

- Don’t be afraid to mix media. Use charcoal or wax crayon to draw shapes or details over collage. Use paint to cover flat bright areas, or to add texture or pattern to your still life.

If you are still stuck for ideas, this animation may help!

- iMap animation: Pablo Picasso, Bowl of Fruit, Violin and Bottle 1913

Activity 4: Be inspired by other artists

John Stezaker Third Person (1988–9) Tate

© John Stezaker

Phoebe Unwin Man with Heavy Limbs (2009) Tate

© Phoebe Unwin

Richard Hamilton Interior (1964–5) Tate

© The estate of Richard Hamilton

Albert Gleizes Painting (1921) Tate

Francis Bacon Three Figures and Portrait (1975) Tate

© Estate of Francis Bacon

Patrick Caulfield Hemingway Never Ate Here (1999) Tate

© The estate of Patrick Caulfield. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2024

Braque and Picasso developed cubism a century ago, but artists and designers have been influenced by the ideas and techniques ever since. How have they updated cubism?

Choose a cubist-inspired artwork from the works above or from Tate’s collection . Make a quick drawing of it in your sketchbook. Think about the following and annotate (add notes to) your drawing with your thoughts:

- How do you think the artist was influenced by cubism?

- Why do you like the artwork? What does it make you think or feel?

- Is there anything in the artist’s approach that gives you ideas for how you could update cubism?

Activity 5: Create your own cubist artwork

You have investigated cubist sources and approaches and have researched how other artists have used cubist ideas and style. Now plan your artwork using what you have discovered, and update cubism for the twenty-first century.

- Review what you have found out about cubism

- Decide what you think are the key features of cubism. Which of these will you make use of in your artwork? List your ideas in your sketchbook

- Braque and Picasso painted ordinary objects that were part of their everyday lives. Think of objects that reflect your lifestyle and interests. Make a note of them in your sketchbook

- Braque and Picasso experimented with techniques and approaches. Can you think of ways you could use technology to make a state-of-the-art still life?

You should now have plenty of ideas for your updated cubist still life. Picasso and Braque were innovators, experimenting with radical new approaches in the way they depicted the world they saw around them. Their artworks still seem exciting and daring to us one hundred years later. Make sure your artwork has what it takes to inspire others and stands the test of time!

Cubist artists in the collection

Pablo picasso, georges braque, related terms and concepts.

Cubism was a revolutionary new approach to representing reality invented in around 1907–08 by artists Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. They brought different views of subjects (usually objects or figures) together in the same picture, resulting in paintings that appear fragmented and abstracted

Orphism was an abstract, cubist influenced painting style developed by Robert and Sonia Delaunay around 1912

Analytical cubism

The term analytical cubism describes the early phase of cubism, generally considered to run from 1908–12, characterised by a fragmentary appearance of multiple viewpoints and overlapping planes

Synthetic cubism

Synthetic cubism is the later phase of cubism, generally considered to run from about 1912 to 1914, characterised by simpler shapes and brighter colours

- PAINTINGS FOR SALE

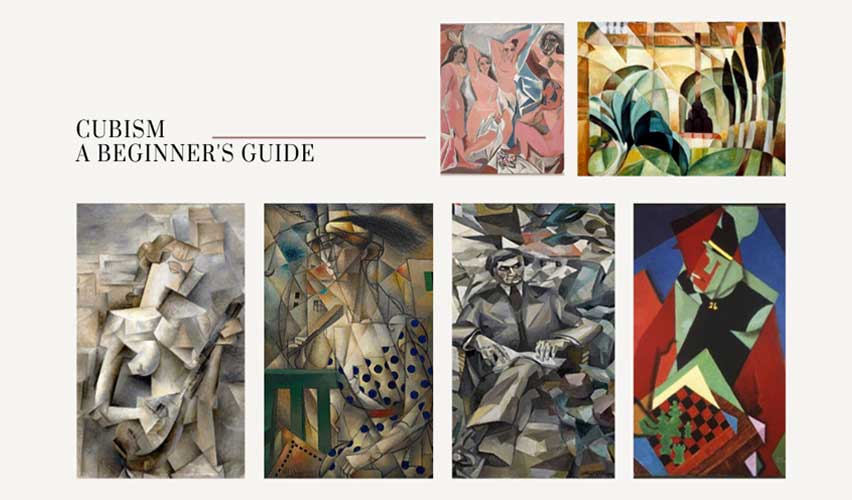

CUBISM A BEGINNER’S GUIDE

Cubism Introduction

Welcome to this month’s Oil Painting Blog. *

Last month, we looked at Post-Impressionism and artists such as Van Gogh, Gauguin and Cezanne.

This month, we will be focusing on another key artist movement – Cubism.

I think this is a natural progression, given that, it is often said that the work of Cezanne set the stage for Cubism. In 1907, a year after his death, a landmark retrospective of his artwork was held at the Salon d’Automne, this proved to have a lasting impact on many influential artists of that time. These artists would go on to echo Cezanne’s train of thought – that all-natural forms could be analysed as cylinders, spheres or cones [1] – essentially, geometric reductions – known as Cezanne Cubism or Proto Cubism.[2]

Cubism was a movement that broke with academic tradition. All rules of modelling, foreshortening and perspective developed and established since the time of the Renaissance masters [3], were basically fired out the window, and completely rejected by all those involved in this art movement.

Instead, over a relatively short period of 6 years (1908 – 1914), Cubists began to analyse structure, simplifying it to a two-dimensional form, but at the same time, fracturing it from multiple viewpoints – this was Stage One – known as ‘Early Cubism’ or ‘Analytic Cubism’ (1908 – 1912).

Girl with a Mandolin (Fanny Tellier) Pablo Picasso 1910

Rhum et Guitare (Rum and Guitar) Georges Braque 1918

Colección Abelló , Madrid

Initially, Cubists used a limited colour pallet but as the movement develop so to, did their use of colour and style, which also underwent a further simplification of form – this was Stage Two – known as ‘Late Cubism’ or ‘Synthetic Cubism’ (1912-1914).

Les Baigneuses (The Bathers) Albert Gleizes 1912

Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

Femme à l’Éventail (Woman with a Fan) Jean Metzinger 1912

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

After 1914, Cubism developed into the overlapping of geometric planes and flat surfaces known as ‘Crystal Cubism’ (1914 – 1918). Thereafter, it went on to influence many new art movements.

Soldat jouant aux échecs (Soldier at a Game of Chess) Jean Metzinger 1914-15

Smart Museum of Art

Cubism – The Beginning

In 1907, Picasso painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon Pablo Picasso 1907

Museum of Modern Art, New York

It took 9 months to complete, and, at the time, was called the most innovative painting since the work of Giotto. [4]

Initially, inspired by Picasso’s fascination with Iberian sculpture and African and Oceanic masks, it depicts a group of nude prostitutes in a brothel in Avignon, Barcelona’s red-light district. The painting is often seen as the starting point for Cubism. [5] It went on to influence Charles Braque, initially a sceptic, like many artists close to Picasso, however, after painting a large nude himself under the influence of this painting, he became a co-creator with Picasso, and together they pushed visual representation to its limits. [6]

Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973)

George Braque (1882 – 1963)

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Inspired by the work of Picasso and Braque, another group of artists, including André Lhote (1885 – 1962) and Albert Gleize (1881 – 1953), helped bring the movement forward, by employing bright colours and paying homage to Cezanne.

French Landscape André Lhote 1912

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux

Portrait de Jacques Nayral Albert Gleizes 1911

Tate Modern, London

However, their exhibitions at the Salon des Independents of 1911 and 1912, were a public scandal, with the artworks being considered as shocking, radical, and leading to questions being asked in government in protest of this apparent waste of money. [7] This all helped however to bring the movement to the attention of Paris and in 1912, the first book on the subject was published by Gleizes and Jean Metzinger (1883 – 1956).

Cubism – The Ending?

With the onset of the Great War in 1914 – 1918, Cubism became less popular.

Many of the artists involved in the movement, had been conscripted into the French Army including Braque who suffered a head wound and parted ways from Picasso thereafter.

Following the War, there was a widespread reaction against Cubism – sometimes called the “Return to Order” [8]. It was the overall impact of trench warfare and the destruction of the human body on an unprecedented scale, that perhaps led to this “Return to Order” and a “Return to Figuration” [9] in the art world.

However, that being said, Cubism, laid the groundwork for the next 50 years in 20 th Century Modern Art, influencing many new art movements including, Futurism, Surrealism, Dada, De Stijl, Bauhaus and Abstract Expressionism.

Cubism and the Irish

After the War ended, it was once again safe for Irish artists to travel and train in Paris. Most notably May Guinness, Jack Hanlon, Evie Hone, Mainie Jellett, Nora McGuinness and Mary Swanzy.

Between 1920 – 1930’s, many of these artists trained and/or were heavily influenced by Lhote and Gleizes and this also helped in the continuation of the Cubist movement.

Oil Painting à la mode d’André Lhote Mary Swanzy undated

Drogheda’s Municipal Art Gallery

Homage to Fra Angelico Maine Jellett 1928

Image from Adams Catalogue

If you would like to learn more on Cubism, the Crawford Art Gallery , Irish Museum of Modern Art and the F.E. McWilliam Gallery & Studio together published Analysing Cubism which is well worth a read.

We will be taking our summer break in June and July. However, our oil painting blogs will be back again on the last Tuesday in August, where we will be looking at some key artists and how their painting style changed over the course of their lives.

Until then have a great Summer!!

Emily May 2022

* As always, I am not affiliated with any brands, stores, or persons I may or may not mention and your use of any of these products, links and the like are your own risk and it’s up to you to do your research/homework before you use them. This is just my opinion and experience.

[1] Paul Cézanne, Letters, ed. John Rewald, 4th ed., New York, 1976, p. 301

[2] Abstract Painting and Sculpture, Crystal Cubism (1915 – 1916), http://www.abstractpaintingsandsculpture.com/artist/crystal-cubism-art-1915-1916/

[3] Kissane S., Analysing Cubism, (Pub Crawford Art Gallery 2013) p.12

[4] Payne, L., Essential Picasso, 1 st edn (2000) (Parragon), p.60.

[5] Hodge, S., Everything you need to know about the greatest artists and their works, 2 nd Edn (Quercus Editions Ltd) (2013), p.186

[6] Artists, Their Lives and Works, 1 st edn (2017) (DK Penguin Random House) p.291

[7] Kissane S., Analysing Cubism, (Pub Crawford Art Gallery 2013) p.13

[8] A, Graham-Dixon, ‘Art – The Definitive Visual Guide’ (1 st edn, Penguin 2008) p.416

[9] Kissane S., Analysing Cubism, (Pub Crawford Art Gallery 2013) p.14

Become an insider, subscribe to receive

Stunning previews of new art, discounts, painting tips and early booking for painting workshops.

Art Studio and Gallery is located in Co. Meath, Ireland – between Kilcock, Maynooth & Dunboyne | Contact

Copyright 2023 Emily McCormack | All Rights Reserved | Privacy Policy | Terms & Conditions | Disclaimer | Website Design

- International

- Schools directory

- Resources Jobs Schools directory News Search

Cubism Lesson and Homework

Subject: Art and design

Age range: 11-14

Resource type: Lesson (complete)

Last updated

14 November 2018

- Share through email

- Share through twitter

- Share through linkedin

- Share through facebook

- Share through pinterest

Tes paid licence How can I reuse this?

Your rating is required to reflect your happiness.

It's good to leave some feedback.

Something went wrong, please try again later.

This resource hasn't been reviewed yet

To ensure quality for our reviews, only customers who have purchased this resource can review it

Report this resource to let us know if it violates our terms and conditions. Our customer service team will review your report and will be in touch.

Not quite what you were looking for? Search by keyword to find the right resource:

Age and G rade Level This is a good lesson for adults and children who have mastered some abstract thinking ability. This lesson is best above second grade, but advanced kindergarten children enjoy it. Teaching the L esson Do NOT show artwork or say the word cubism until near the end of the lesson. Do NOT demonstrate. Students learn by doing.

H ave students practice from the motivations behind cubism without first seeing cubist images. Just like real artists are inventors, guide students to make discoveries , we help students discover cubism themselves. Celebrate with them. Help your students develop the habits of thinking used by highly creative people rather than teaching them to emulate artists by copying the mere look of their work. In order to do this, the teacher has studied cubism and has a working understanding of the theories and aesthetic motivations of historic cubism. Traditionally, art historians have supposed that cubism represented a way of seeing our world from multiple viewpoints simultaneously, but now we have strong evidence that Braque and Picasso were influenced by the invention of motion pictures.

In 2007, there was a ground-breaking exhibition: Picasso, Braque and Early Film in Cubism at the Pace Wildenstein in Brooklyn, New York, April 20 – June 23, 2007. Arne Glimcher and Bernice Rose invented and curated this very innovative exhibition that illustrates the influences of early motion picture film on minds of Picasso and Braque. Numerous art historians and painters have studied cubism for nearly 100 years and have never seen what has long seemed very obvious to Arne Glimcher. See sources below: #1 Micchelli, #2 Rose

Subject Matter The teacher guides the students who learn to set up a large still life in the middle of the room or several small setups in the middle of their work tables. They bring in sporting stuff, stuffed toys, musical instruments, some cloth, a few dry weeds, and so on.

Depending of the season, some teachers bring large sunflowers, grapes, gourds, squash, onions, eggplant, apples, and so forth from the garden. Cut a few of these in half. Taste and smell are excellent multi-sensory motivation.

Another variation uses one or two student models that move according to teacher prompts to simulate a dance motion or an athletic action. In the variation below, two chickens move about while the class draws them.

Instructions for the Creative Process

- If working at tables (observing a still-life or animal), encourage students to stand up while drawing so they use arm motions instead finger motions. Ask them to begin by selecting an interesting area in the setup and drawing very large so things go off the edges. Cardboard viewfinders (or empty 35 mm slide frames) are helpful in finding and sizing things. If it is a still-life, students work for few minutes until the teacher has them move to a completely different position and continue drawing the same objects on the same paper overlapping with the drawing they started (or move the still-life).

- Ask thinking questions and experiment questions. "What happens when you change the size or scale when you change position? For those that have been drawing large: "What happens when you add small detail?" For those that draw small: "What happens when you make the next part very much larger? How does it seem to move in and out in from your paper?" As much as posible, try to use open questions and "what if" questions rather than commands or suggestions.

- Repeat drawing and moving to a new position until the paper begins to fill with overlapping and transparent drawing content.

- After a few moves, invite students to slowly walk around to see how other students have worked at the problem. Affirm a diversity of approaches. Ask them a series of open questions to make them aware of motion and time. "How do the drawings suggest motion? Does anything in the drawings look farther away or closer to you? How does this happen? What things are repeated with variation? Can you see things about the drawings that move you into the drawing or away from the drawing? Do you see the effects of size change, of repetition, of gradation, and so on?"

- As the paper begins to fill with overlapping shapes, ask them what happens when you shade in and color the drawing to create an overall pattern. What is the effect of gradations? What if they include some recognizable places here and there? Can the evaluation is to be more on overall design and movement than on realism? Ask them how they can make adjustments in the compositions to achieve unity and harmony so that no one area becomes too dominant or different than the whole.

- When most of them appear to be nearly complete, or when the first to finish feel they are done, have them all stop and form groups of three.

- Prohibit negative responses. Encourage the use of questions that analyze and speculate.

- Using six eyes instead of two, ask them to look at each other's work and tell them what parts of their pictures they notice first and why. What parts are showing most emphasis and what parts show the least emphasis. Encourage every student to participate, to form questions, to describe what is noticed, to analyze, and to speculate.

- Ask them to discuss time and motion in the works.

- They are not to use judgmental terms like good or bad, just say what they see that shows the most and try to give some reasons and explanations.

Continue the Creative Process If a student asks the teacher to tell what to do next or if it is good enough, the teacher asks them a question that gets them remember the process or to look at parts that they may have missed. The teacher refrains from telling them what to do. The teacher does not make a suggestion . The teacher gives them open choices rather than commands or directions. The product is not supposed to have a certain look, but the students are supposed to learn to make their own artistic choices based on criteria the teacher gives. Resist the temptation to make specific suggestions. Student thinking is cultivated better when the teacher honors the student ideas and does not do the thinking for the students.

Ending Critique

- When they are done, have them post the work for all to see. Discuss the work by again asking what they notice first. Do not allow negative comments.

- Follow the initial response by asking for explanations of why they notice certain things. This is not judging, it is describing and analyzing. If students miss things, the teacher asks about them. "Why do I see motion in this drawing?"

- Sometimes it is also interesting to speculate about the meaning of their pictures (interpretation). Making up titles helps with this.

- Show one or more example(s) of Georges Braque and or Picasso who invented cubism (use any general reference art history book, library books on artists, slides, reproductions, posters, and/or the internet). It is quite easy to print color pictures from the web onto transparencies blanks made for ink jet printers (footnote web sources). These can be shown in a class with an overhead projector if your class does not have a computer projector to show them directly from the web site. Kennedy - Rose

- Ask them to speculate about the process the artist(s) must have used to come up with their compositions. Ask them how they think the artist was looking at the work.

- Ask them to speculate about the reasons the artist decided not to simply show a simple picture of the subject matter.

- Ask them to remember the way motion pictures move from clip to clip to tell a story. Kennedy - Rose

- Explain the word Cubism and give a bit of background on how innovative it was in the art world at the time it was invented.

- David Hockney is a contemporary British artist who has played with these concepts by using photography to make many pictures of of the same thing and putting them all together in a composition that gives what he feels is a much more realistic impression of how we perceive the world. He likens the typical camera's photograph to the view of one eyed single impression Cyclops. He claims that as humans we really see the world by mentally composing reality from many visual impressions of a subject or scene. Which is realism?

- Ask the students to write a short paragraph about what kind of art they think Picasso and Braque would invent if they where living today with cell phones, high speed Internet, and space travel.

- Students are asked to make sketchbook entries that cover a portion of a typical day all in one overlapping and transparent composition. For example, each sketch combines several aspects of the morning trip to school or the afternoon trip home.

- Aesthetically, they are encouraged to reflect on the differences in their feelings in the morning compared to their feelings in the afternoon. How does is difference in feeling represented in their cubist time sequence compositions. Could it be done with color relationships, with size, with line type, or another device?

- Ask a review question.

- Ask an art vocabulary question. What does "emphasis" mean in a composition? What does "unity" mean? What are the differences between "unity" and "harmony"?

- How are artists similar to inventors?

- Is cubism more or less realistic than realism?

- How is the passage of time be shown in a drawing?

- Which is more beautiful, movement or symmetry and stability?

- What are the ways to show motion in a drawing?

- Which of you previous projects would be more fun if they included what we learned about motion today?

Review is even more effective if it is done again at the beginning of the next session a day or more later. When a teacher expects students to remember things from session to session, students thinking habits are gradually trained to remember. They learn to expect that what is being learned has a purpose and it is to be incorporated into the next project. Ask questions that connect previous learning with today's questions and artwork.

To encourage creativity, pose questions that will be coming up in art class in the near future. I try to respond with enthusiasm to unexpected results--even when they are unexpected by me. "Wow! How did you do that?"

<><> END OF LESSON <><>

Credit: This lesson was inspired by a similar lesson developed and taught by Judy Wenig-Horswell , Associate Professor of Art, Goshen College.

Not enough time to do this lesson? Do not take shortcuts. Think of it as a unit that continues for as many sessions as are needed to do it well. Start each session with warm-up and review. Many more things are learned when we take the time to do something well. Teaching many short lessons leaves the impression that art is quick and easy. Art is not a bunch of products. It is a way of thinking and working that materializes and expresses ideas. Artist know that things worth doing take time and may require lots of experimentation.

SOURCES AND REFERENCES USED ABOVE - - - - Top of page

Kennedy, R. (2007) “When Picasso and Braque Went to the Movies.” New York Times, April 15, 2007

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/15/arts/design/15kenn.html [retrieved 12/14/2010]

Rose, C. (2007) “A discussion about Picasso, Braque and Early Film in Cubism with Bernice Rose and Arne Glimcher in Art & Design ” Friday, June 8, 2007 ” Charlie Rose, © 2010

http://www.charlierose.com/view/interview/8540 [retrieved 12/14/2010]

All Rights reserved © 2001, 2nd edition in 2008, by Marvin Bartel, Emeritus Professor of Art, Goshen College. All text and photo rights reserved. You are invited to link this page to your page. For permission to reproduce or place this page on your site or to make printed copies, contact the author. Marvin Bartel, Ed.D., Emeritus Professor of Art Adjunct in Art Education Goshen College , 1700 South Main St., Goshen IN 46526 Author Bio updated: December 2008 A link to lessons on Cubism from New Zealand

GOSHEN COLLEGE Goshen, IN - USA

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Arts and Entertainment

How to Do a Cubist Style Painting

Last Updated: April 4, 2024 Approved

This article was co-authored by Kelly Medford . Kelly Medford is an American painter based in Rome, Italy. She studied classical painting, drawing and printmaking both in the U.S. and in Italy. She works primarily en plein air on the streets of Rome, and also travels for private international collectors on commission. She founded Sketching Rome Tours in 2012 where she teaches sketchbook journaling to visitors of Rome. Kelly is a graduate of the Florence Academy of Art. There are 10 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. This article received 14 testimonials and 84% of readers who voted found it helpful, earning it our reader-approved status. This article has been viewed 271,418 times.

Cubism is a style of painting that originated with Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso between 1907 and 1914. [1] X Research source The Cubist style sought to show the two-dimensional nature of the canvas. Cubist artists fractured their objects into geometric forms and used multiple and contrasting perspectives in a single painting. It was called Cubism when Louis Vauxcelles, a French art critic, called the forms in Braque’s work “cubes.” Creating your own Cubist style painting can be a fun way to connect with art history and look at painting with a fresh perspective.

Preparing to Paint Your Cubist Art

- Lay down newspaper in your work area to keep it clean.

- Use a glass of water and a soft rag to clean your paintbrushes between colors.

- If you just want to practice, you can also create paintings on large multi-media art paper.

- Your local art supply store should carry paper and canvas.

- You can use any type of paint to achieve a Cubist style, but acrylic works well, especially for beginners. Acrylic paints are versatile, often less expensive than oil paints, and make it easier to create crisp lines. [3] X Research source

- Pick paintbrushes that are labeled for acrylic paints. Get a few different sizes for versatility while you paint.

- Make sure you have a pencil and gum eraser on hand to sketch before you begin to paint.

- You may also need a ruler or yardstick to help guide your lines and make them crisp and straight.

- Decide whether you want to paint a human figure, a landscape, or a still life.

- Choose something that you can look at and study in real life while you are painting. For example, if you want to do a figure, see if a friend can pose for you. If you’d like to paint a still life, arrange a group of objects or an object, like a musical instrument, in front of you.

- Once you have a general sketch, use your ruler to sharpen the edges.

- In any place you’ve sketched soft, rounded lines, go back over them and change them into sharp lines and edges.

- For example, if you’re sketching a person, you might go over the rounded line of the shoulder and make it look more like the top of a rectangle.

Putting Your Idea on Canvas

- Look at the light. Instead of shading and blending, in Cubism, you will use the light to create shapes. Outline, in geometric shapes, where the light falls in your painting.

- Also, use geometric lines to show where you would generally shade in a painting.

- Don’t be afraid to overlap your lines.

- If you want to use bright colors, choose to use between one and three main bright colors so that your painting retains its striking geometry.

- You can also use a monochromatic palette in a single color family. For example, Picasso did many paintings mainly in shades of blue.

- Put your paints onto your palette or a paper plate in front of you. Use white to make shades lighter. Mix the colors that you want.

- With acrylic paints, you can layer colors to make your paintings feel more dimensional.

- If you need to do so, use your ruler to guide your paintbrush, like you did your pencil. You want your paint lines to be just as crisp as your pencil lines.

Making a Cubist Painting for Kids

- Washable acrylic paints work well for painting with kids. You can also create a “painting” masterpiece with markers, crayons, or colored pencils.