Understanding Creativity

- Posted June 25, 2020

- By Emily Boudreau

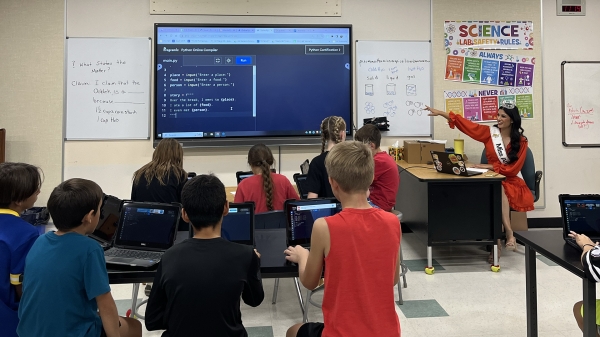

Understanding the learning that happens with creative work can often be elusive in any K–12 subject. A new study from Harvard Graduate School of Education Associate Professor Karen Brennan , and researchers Paulina Haduong and Emily Veno, compiles case studies, interviews, and assessment artifacts from 80 computer science teachers across the K–12 space. These data shed new light on how teachers tackle this challenge in an emerging subject area.

“A common refrain we were hearing from teachers was, ‘We’re really excited about doing creative work in the classroom but we’re uncertain about how to assess what kids are learning, and that makes it hard for us to do what we want to do,’” Brennan says. “We wanted to learn from teachers who are supporting and assessing creativity in the classroom, and amplify their work, and celebrate it and show what’s possible as a way of helping other teachers.”

Create a culture that values meaningful assessment for learning — not just grades

As many schools and districts decided to suspend letter grades during the pandemic, teachers need to help students find intrinsic motivation. “It’s a great moment to ask, ‘What would assessment look like without a focus on grades and competition?’” says Veno.

Indeed, the practice of fostering a classroom culture that celebrates student voice, creativity, and exploration isn’t limited to computer science. The practice of being a creative agent in the world extends through all subject areas.

The research team suggests the following principles from computer science classrooms may help shape assessment culture across grade levels and subject areas.

Solicit different kinds of feedback

Give students the time and space to receive and incorporate feedback. “One thing that’s been highlighted in assessment work is that it is not about the teacher talking to a student in a vacuum,” says Haduong, noting that hearing from peers and outside audience members can help students find meaning and direction as they move forward with their projects.

- Feedback rubrics help students receive targeted feedback from audience members. Additionally, looking at the rubrics can help the teacher gather data on student work.

Emphasize the process for teachers and students

Finding the appropriate rubric or creating effective project scaffolding is a journey. Indeed, according to Haduong, “we found that many educators had a deep commitment to iteration in their own work.” Successful assessment practices conveyed that spirit to students.

- Keeping design journals can help students see their work as it progresses and provides documentation for teachers on the student’s process.

- Consider the message sent by the form and aesthetics of rubrics. One educator decided to use a handwritten assessment to convey that teachers, too, are working on refining their practice.

Scaffold independence

Students need to be able to take ownership of their learning as virtual learning lessens teacher oversight. Students need to look at their own work critically and know when they’ve done their best. Teachers need to guide students in this process and provide scaffolded opportunities for reflection.

- Have students design their own assessment rubric. Students then develop their own continuum to help independently set expectations for themselves and their work.

Key Takeaways

- Assessment shouldn’t be limited to the grade a student receives at the end of the semester or a final exam. Rather, it should be part of the classroom culture and it should be continuous, with an emphasis on using assessment not for accountability or extrinsic motivation, but to support student learning.

- Teachers can help learners see that learning and teaching are iterative processes by being more transparent about their own efforts to reflect and iterate on their practices.

- Teachers should scaffold opportunities for students to evaluate their own work and develop independence.

Additional Resources

- Creative Computing curriculum and projects

- Karen Brennan on helping kids get “unstuck”

- Usable Knowledge on how assessment can help continue the learning process

Usable Knowledge

Connecting education research to practice — with timely insights for educators, families, and communities

Related Articles

Strategies for Leveling the Educational Playing Field

New research on SAT/ACT test scores reveals stark inequalities in academic achievement based on wealth

How to Help Kids Become Skilled Citizens

Active citizenship requires a broad set of skills, new study finds

Extra Credit

- Become a Member

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computational Thinking

- Digital Citizenship

- Edtech Selection

- Global Collaborations

- STEAM in Education

- Teacher Preparation

- ISTE Certification

- School Partners

- Career Development

- ISTELive 24

- 2024 ASCD Annual Conference

- Solutions Summit

- Leadership Exchange

- 2024 ASCD Leadership Summit

- Edtech Product Database

- Solutions Network

- Sponsorship & Advertising

- Sponsorship & Advertising

- Learning Library

5 Reasons Why It Is More Important Than Ever to Teach Creativity

- Education Leadership

On the laundry list of skills and content areas teachers have to cover, creativity doesn’t traditionally get top billing. It’s usually lumped together with other soft skills like communication and collaboration: Great to have, though not as important as reading or long division.

But research is showing that creativity isn’t just great to have. It’s an essential human skill — perhaps even an evolutionary imperative in our technology-driven world.

“The pace of cultural change is accelerating more quickly than ever before,” says Liane Gabora , associate professor of psychology and creative studies at the University of British Columbia. “In some biological systems, when the environment is changing quickly, the mutation rate goes up. Similarly, in times of change we need to bump up creativity levels — to generate the innovative ideas that will keep us afloat.”

From standardized tests to one-size-fits-all curriculum, public education often leaves little room for creativity, says EdNews Daily founder Robyn D. Shulman . This puts many schools out of sync with both global demand and societal needs, leaving students poorly prepared for future success.

What can education leaders do about it? For starters, they can make teaching creativity a priority. Here are five reasons to encourage teachers to bring more creativity into the classroom:

1. Creativity motivates kids to learn.

Decades of research link creativity with the intrinsic motivation to learn. When students are focused on a creative goal, they become more absorbed in their learning and more driven to acquire the skills they need to accomplish it.

As proof, education leader Ryan Imbriale cites his young daughter, who loves making TikTok videos showcasing her gymnastics skills. “She spends countless hours on her mat, working over and over again to try to get her gymnastics moves correct so she can share her TikTok video of her success,” says the executive director of innovative learning for Baltimore County Public Schools.

Students are most motivated to learn when certain factors are present: They’re able to tie their learning to their personal interests, they have a sense of autonomy and control over their task, and they feel competent in the work they’re doing. Creative projects can easily meet all three conditions.

2. Creativity lights up the brain.

Teachers who frequently assign classwork involving creativity are more likely to observe higher-order cognitive skills — problem solving, critical thinking, making connections between subjects — in their students. And when teachers combine creativity with transformative technology use, they see even better outcomes.

Creative work helps students connect new information to their prior knowledge, says Wanda Terral, director of technology for Lakeland School System outside of Memphis. That makes the learning stickier.

“Unless there’s a place to ‘stick’ the knowledge to what they already know, it’s hard for students to make it a part of themselves moving forward,” she says. “It comes down to time. There’s not enough time to give them the flexibility to find out where the learning fits in their life and in their brain.”

3. Creativity spurs emotional development.

The creative process involves a lot of trial and error. Productive struggle — a gentler term for failure — builds resilience, teaching students to push through difficulty to reach success. That’s fertile soil for emotional growth.

“Allowing students to experience the journey, regardless of the end result, is important,” says Terral, a presenter at ISTE Creative Constructor Lab .

Creativity gives students the freedom to explore and learn new things from each other, Imbriale adds. As they overcome challenges and bring their creative ideas to fruition, “students begin to see that they have limitless boundaries,” he says. “That, in turn, creates confidence. It helps with self-esteem and emotional development.”

4. Creativity can ignite those hard-to-reach students.

Many educators have at least one story about a student who was struggling until the teacher assigned a creative project. When academically disinclined students are permitted to unleash their creativity or explore a topic of personal interest, the transformation can be startling.

“Some students don’t do well on tests or don’t do well grade-wise, but they’re super-creative kids,” Terral says. “It may be that the structure of school is not good for them. But put that canvas in front of them or give them tools so they can sculpt, and their creativity just oozes out of them.”

5. Creativity is an essential job skill of the future.

Actually, it’s an essential job skill right now.

According to an Adobe study , 85% of college-educated professionals say creative thinking is critical for problem solving in their careers. And an analysis of LinkedIn data found that creativity is the second most in-demand job skill (after cloud computing), topping the list of soft skills companies need most. As automation continues to swallow up routine jobs, those who rely on soft skills like creativity will see the most growth.

“We can’t exist without the creative thinker. It’s the idea generation and the opportunity to collaborate with others that moves work,” Imbriale says.

“It’s one thing to be able to sit in front of computer screen and program something. But it’s another to have the conversations and engage in learning about what somebody wants out of a program to be written in order to be able to deliver on that. That all comes from a creative mindset.”

Nicole Krueger is a freelance writer and journalist with a passion for finding out what makes learners tick.

- artificial intelligence

About The Education Hub

- Course info

- Your courses

- ____________________________

- Using our resources

- Login / Account

What is creativity in education?

- Curriculum integration

- Health, PE & relationships

- Literacy (primary level)

- Practice: early literacy

- Literacy (secondary level)

- Mathematics

Diverse learners

- Gifted and talented

- Neurodiversity

- Speech and language differences

- Trauma-informed practice

- Executive function

- Movement and learning

- Science of learning

- Self-efficacy

- Self-regulation

- Social connection

- Social-emotional learning

- Principles of assessment

- Assessment for learning

- Measuring progress

- Self-assessment

Instruction and pedagogy

- Classroom management

- Culturally responsive pedagogy

- Co-operative learning

- High-expectation teaching

- Philosophical approaches

- Planning and instructional design

- Questioning

Relationships

- Home-school partnerships

- Student wellbeing NEW

- Transitions

Teacher development

- Instructional coaching

- Professional learning communities

- Teacher inquiry

- Teacher wellbeing

- Instructional leadership

- Strategic leadership

Learning environments

- Flexible spaces

- Neurodiversity in Primary Schools

- Neurodiversity in Secondary Schools

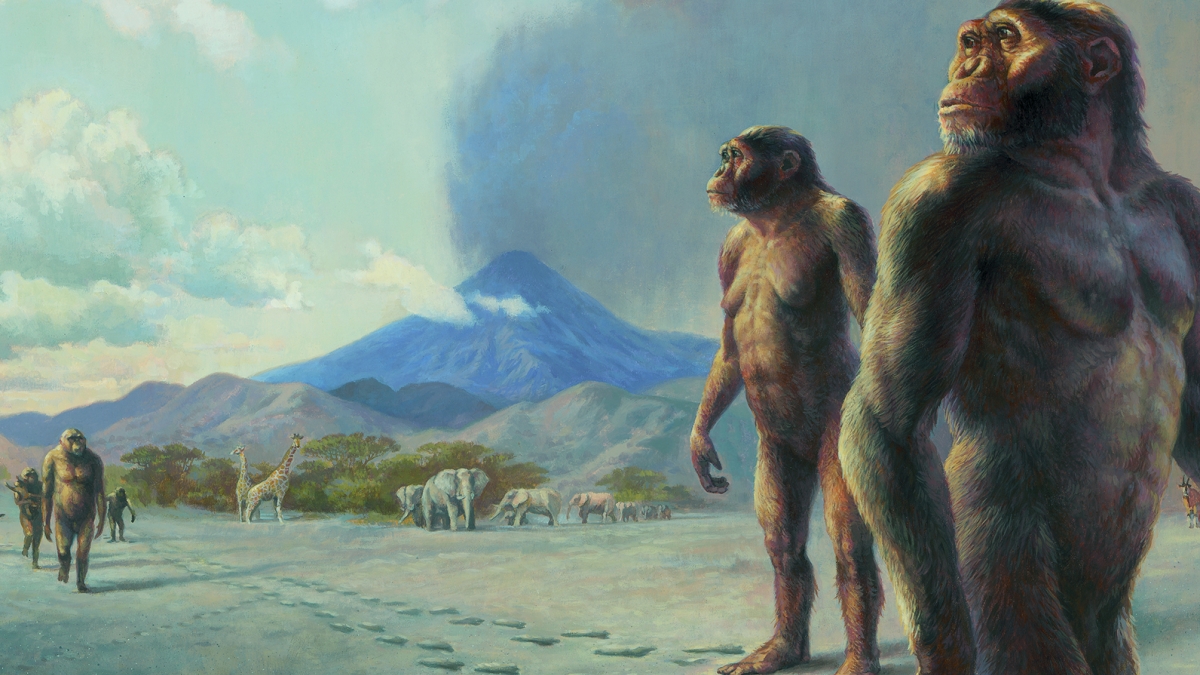

Human beings have always been creative. The fact that we have survived on the planet is testament to this. Humans adapted to and then began to modify their environment. We expanded across the planet into a whole range of climates. At some point in time we developed consciousness and then language. We began to question who we are, how we should behave, and how we came into existence in the first place. Part of human questioning was how we became creative.

The myth that creativity is only for a special few has a long, long history. For the Ancient Chinese and the Romans, creativity was a gift from the gods. Fast forward to the mid-nineteenth century and creativity was seen as a gift, but only for the highly talented, romantically indulgent, long-suffering and mentally unstable artist. Fortunately, in the 1920s the field of science began to look at creativity as a series of human processes. Creative problem solving was the initial focus, from idea generation to idea selection and the choice of a final product. The 1950s were a watershed moment for creativity. After the Second World War, the Cold War began and competition for creative solutions to keep a technological advantage was intense. It was at this time that the first calls for STEM in education and its associated creativity were made. Since this time, creativity has been researched across a whole range of human activities, including maths, science, engineering, business and the arts.

The components of creativity

So what exactly is creativity? In the academic field of creativity, there is broad consensus regarding the definition of creativity and the components which make it up. Creativity is the interaction between the learning environment, both physical and social, the attitudes and attributes of both teachers and students, and a clear problem-solving process which produces a perceptible product (that can be an idea or a process as well as a tangible physical object). Creativity is producing something new, relevant and useful to the person or people who created the product within their own social context. The idea of context is very important in education. Something that is very creative to a Year One student – for example, the discovery that a greater incline on a ramp causes objects to roll faster – would not be considered creative in a university student. Creativity can also be used to propose new solutions to problems in different contexts, communities or countries. An example of this is having different schools solve the same problem and share solutions.

Creativity is an inherent part of learning. Whenever we try something new, there is an element of creativity involved. There are different levels of creativity, and creativity develops with both time and experience. A commonly cited model of creativity is the 4Cs [i] . At the mini-c level of creativity, what someone creates might not be revolutionary, but it is new and meaningful to them. For example, a child brings home their first drawing from school. It means something to the child, and they are excited to have produced it. It may show a very low level of skill but create a high level of emotional response which inspires the child to share it with their parents.

The little-c level of creativity is one level up from the mini-c level, in that it involves feedback from others combined with an attempt to build knowledge and skills in a particular area. For example, the painting the child brought home might receive some positive feedback from their parents. They place it on the refrigerator to show that it has value, give their child a sketchbook, and make some suggestions about how to improve their drawing. In high school the student chooses art as an elective and begins to receive explicit instruction and assessed feedback. In terms of students at school, the vast majority of creativity in students is at the mini-c and little-c level.

The Pro-c level of creativity in schools is usually the realm of teachers. The teacher of art in this case finds a variety of pedagogic approaches which enhance the student artist’s knowledge and skills in art as well as building their creative competencies in making works of art. They are a Pro-c teacher. The student will require many years of deliberate practice and training along with professional levels of feedback, including acknowledgement that their work is sufficiently new and novel for them to be considered a creative professional artist at the pro-c level.

The Big-C level of creativity is the rarefied territory of the very few. To take this example to the extreme, the student becomes one of the greatest artists of all time. After they are dead, their work is discussed by experts because their creativity in taking art to new forms of expression is of the highest level. Most of us operate at the mini-c and little-c level with our hobbies and activities. They give us great satisfaction and enjoyment and we enjoy building skills and knowledge over time. Some of us are at the pro-c level in more than one area.

The value of creativity in education

Creativity is valuable in education because it builds cognitive complexity. Creativity relies on having deep knowledge and being able to use it effectively. Being creative involves using an existing set of knowledge or skills in a particular subject or context to experiment with new possibilities in the pursuit of valued outcomes , thus increasing both knowledge and skills. It develops over time and is more successful if the creative process begins at a point where people have at least some knowledge and skills. To continue the earlier example of the ramp, a student rolling a ball down an incline may notice that the ball goes faster if they increase the incline, and slower if they decrease it. This discovery may lead to other possibilities – the student might then go on to observe how far the ball rolls depending on the angle of the incline, and then develop some sort of target for the ball to reach. What started as play has developed in a way that builds the student’s knowledge, skills and reasoning. It represents the beginning of the scientific method of trial and error in experimentation.

Creativity is not just making things up. For something to meet the definition of creativity, it must not only be new but also relevant and useful. For example, if a student is asked to make a new type of musical instrument, one made of salami slices may be original and interesting, but neither relevant nor useful. (On the other hand, carrots can make excellent recorders). Creativity also works best with constraints, not open-ended tasks. For example, students can be given a limit to the number of lines used when writing a poem, or a set list of ingredients when making a recipe. Constrained limits lead to what cognitive scientists call desirable difficulties as students need to make more complex decisions about what they include and exclude in their final product. A common STEM example is to make a building using drinking straws but no sticky tape or glue. Students need to think more deeply about how the various elements of a building connect in order for the building to stand up.

Creativity must also have a result or an outcome . In some cases the result may be a specific output, such as the correct solution to a maths problem, a poem in the form of a sonnet, or a scientific experiment to demonstrate a particular type of reaction. As noted above, outputs may also be intangible: they might be an idea for a solution or a new way of looking at existing knowledge and ideas. The outcome of creativity may not necessarily be pre-determined and, when working with students, generating a specific number of ideas might be a sufficient creative outcome.

Myths about creativity

It is important that students are aware of the components that make up creativity, but it is also critical that students understand what creativity is not, and that the notion of creativity has been beset by a number of myths. The science of creativity has made great progress over the last 20 years and research has dispelled the following myths:

- Creativity is only for the gifted

- Creativity is only for those with a mental illness

- Creativity only lives in the arts

- Creativity cannot be taught

- Creativity cannot be learned

- Creativity cannot be assessed

- Schools kill creativity in their students

- Teachers do not understand what creativity is

- Teachers do not like creative students

The science of creativity has come a long way from the idea of being bestowed by the gods of ancient Rome and China. We now know that creativity can be taught, learned and assessed in schools. We know that everyone can develop their creative capacities in a wide range of areas, and that creativity can develop from purely experiential play to a body of knowledge and skills that increases with motivation and feedback.

Creativity in education

The world of education is now committed to creativity. Creativity is central to policy and curriculum documents in education systems from Iceland to Estonia, and of course New Zealand. The origins of this global shift lie in the 1990s, and it was driven predominantly by economics rather than educational philosophy.

There has also been a global trend in education to move from knowledge acquisition to competency development. Creativity often is positioned as a competency or skill within educational frameworks. However, it is important to remember that the incorporation of competencies into a curriculum does not discount the importance of knowledge acquisition. Research in cognitive science demonstrates that students need fundamental knowledge and skills. Indeed, it is the sound acquisition of knowledge that enables students to apply it in creative ways . It is essential that teachers consider both how they will support their students to acquire the necessary knowledge and skills in their learning area as well as the opportunities they will provide for applying this knowledge in ways that support creativity. In fact, creativity requires two different sets of knowledge: knowledge and skills in the learning area, and knowledge of and skills related to the creative process, from idea generation to idea selection, as well as the appropriate attitudes, attributes and environment.

Supporting students to be creative

In order for teachers to support students to be creative, they should attend to four key areas. Firstly, creativity needs an appropriate physical and social environment . Students need to feel a sense of psychological safety when being creative. The role of the teacher is to ensure that all ideas are listened to and given feedback in a respectful manner. In terms of the physical environment, a set of simple changes rather than a complete redesign of classrooms is required: modifying the size and makeup of student groups, working on both desks and on whiteboards, or taking students outside as part of the idea generation process can develop creative capacity. Even something as simple as making students more aware of the objects and affordances which lie within a classroom may help with the creative process.

Secondly, teachers can support students to develop the attitudes and attributes required for creativity , which include persistence, discipline, resilience, and curiosity. Students who are more intellectually curious are open to new experiences and can look at problems from multiple perspectives, which builds creative capacity. In maths, for example, this can mean students being shown three or four different ways to solve a problem and selecting the method that best suits them. In Japan, students are rewarded for offering multiple paths to a solution as well as coming up with the correct answer.

Thirdly, teachers can support the creative process . It begins with problem solving, or problem posing, and moves on to idea generation. There are a number of methods which can be used when generating ideas such as brainstorming, in which as many ideas as possible are generated by the individual or by a group. Another effective method, which has the additional benefit of showing the relationships between the ideas as they are generated, is mind-mapping. For example, rather than looking at possible causes of World War Two as a list, it might be better to categorise them into political, social and economic categories using a mind map or some other form of graphic organiser. This creative visual representation may provide students with new and useful insights into the causes of the war. Students may also realise that there are more categories that need to be considered and added, thus allowing them to move from surface to deep learning as they explore relationships rather than just recalling facts. Remember that creativity is not possible without some knowledge and skills in that subject area. For instance, proposing that World War Two was caused by aliens may be considered imaginative, but it is definitely not creative.

The final element to be considered is that of the outcomes – the product or results – of creativity . However, as with many other elements of education, it may be more useful to formatively assess the process which the students have gone through rather than the final product. By exploring how students generated ideas, whether the method of recording ideas was effective, whether the final solutions were practical, and whether they demonstrated curiosity or resilience can often be more useful than merely grading the final product. Encouraging the students to self-reflect during the creative process also provides students with increased skills in metacognition, as well as having a deeper understanding of the evolution of their creative competencies. It may in fact mean that the final grade for a piece of work may take into account a combination of the creative process as observed by the teacher, the creative process as experienced and reported by the student, and the final product, tangible or intangible.

Collard, P., & Looney, J. (2014). Nurturing creativity in education . European Journal of Education, 49 (3), 348-364.

Craft, A. (2001). An analysis of research and literature on creativity in education : Report prepared for the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority.

Runco, M. (2008). Creativity and education . New Horizons in Education, 56 (1), 96-104.

[i] Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond big and little: The four C model of creativity . Review of General Psychology, 13(1), 1-12.

By Tim Patston

PREPARED FOR THE EDUCATION HUB BY

Dr Tim Patston

Dr Tim Patston is a researcher and educator with more than thirty years’ experience working with Primary, Secondary and Tertiary education providers and currently is the leader of consultancy activities for C reative Actions . He also is a senior adjunct at the University of South Australia in UniSA STEM and a senior fellow at the University of Melbourne in the Graduate School of Education. He publishes widely in the field of Creative Education and the development of creative competencies and is the featured expert on creativity in the documentary Finding Creativity, to be released in 2021.

Download this resource as a PDF

Please provide your email address and confirm you are downloading this resource for individual use or for use within your school or ECE centre only, as per our Terms of Use . Other users should contact us to about for permission to use our resources.

Interested in * —Please choose an option— Early childhood education (ECE) Schools Both ECE and schools I agree to abide by The Education Hub's Terms of Use.

Did you find this article useful?

If you enjoyed this content, please consider making a charitable donation.

Become a supporter for as little as $1 a week – it only takes a minute and enables us to continue to provide research-informed content for teachers that is free, high-quality and independent.

Become a supporter

Get unlimited access to all our webinars

Buy a webinar subscription for your school or centre and enjoy savings of up to 25%, the education hub has changed the way it provides webinar content, to enable us to continue creating our high-quality content for teachers., an annual subscription of just nz$60 per person gives you access to all our live webinars for a whole year, plus the ability to watch any of the recordings in our archive. alternatively, you can buy access to individual webinars for just $9.95 each., we welcome group enrolments, and offer discounts of up to 25%. simply follow the instructions to indicate the size of your group, and we'll calculate the price for you. , unlimited annual subscription.

- All live webinars for 12 months

- Access to our archive of over 80 webinars

- Personalised certificates

- Group savings of up to 25%

The Education Hub’s mission is to bridge the gap between research and practice in education. We want to empower educators to find, use and share research to improve their teaching practice, and then share their innovations. We are building the online and offline infrastructure to support this to improve opportunities and outcomes for students. New Zealand registered charity number: CC54471

We’ll keep you updated

Click here to receive updates on new resources.

Interested in * —Please choose an option— Early childhood education (ECE) Schools Both ECE and schools

Follow us on social media

Like what we do please support us.

© The Education Hub 2024 All rights reserved | Site design: KOPARA

- Terms of use

- Privacy policy

Privacy Overview

Thanks for visiting our site. To show your support for the provision of high-quality research-informed resources for school teachers and early childhood educators, please take a moment to register.

Thanks, Nina

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Creativity in education.

- Anne Harris Anne Harris RMIT University

- and Leon De Bruin Leon De Bruin RMIT University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.383

- Published online: 26 April 2018

Creativity is an essential aspect of teaching and learning that is influencing worldwide educational policy and teacher practice, and is shaping the possibilities of 21st-century learners. The way creativity is understood, nurtured, and linked with real-world problems for emerging workforces is significantly changing the ways contemporary scholars and educators are now approaching creativity in schools. Creativity discourses commonly attend to creative ability, influence, and assessment along three broad themes: the physical environment, pedagogical practices and learner traits, and the role of partnerships in and beyond the school. This overview of research on creativity education explores recent scholarship examining environments, practices, and organizational structures that both facilitate and impede creativity. Reviewing global trends pertaining to creativity research in this second decade of the 21st century, this article stresses for practicing and preservice teachers, schools, and policy makers the need to educationally innovate within experiential dimensions, priorities, possibilities, and new kinds of partnerships in creativity education.

- creative ecologies

- creative environments

- creative industries

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 19 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|45.133.227.243]

- 45.133.227.243

Character limit 500 /500

- Skip to Nav

- Skip to Main

- Skip to Footer

Sir Ken Robinson: Creativity Is In Everything, Especially Teaching

Please try again

From Creative Schools by Ken Robinson and Lou Aronica, published April 21, 2015, by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright by Ken Robinson , 2015.

Creative Teaching

Let me say a few words about creativity. I’ve written a lot about this theme in other publications. Rather than test your patience here with repetition of those ideas, let me refer you to them if you have a special interest. In Out of Our Minds: Learning to Be Creative , I look in some detail at the nature of creativity and how it relates to the idea of intelligence in the arts, the sciences, and other areas of human achievement. In 1997, I was asked by the U.K. government to convene a national commission to advise on how creativity can be developed throughout the school system from ages five through eighteen. That group brought together scientists, artists, educators, and business leaders in a common mission to explain the nature and critical importance of creativity in education. Our report, All Our Futures: Creativity, Culture and Education , set our detailed proposals for how to make this happen in practice and was addressed to people working at all levels of education, from schools to government.

It’s sometimes said that creativity cannot be defined. I think it can. Here’s my definition, based on the work of the All Our Futures group: Creativity is the process of having original ideas that have value.

There are two other concepts to keep in mind: imagination and innovation. Imagination is the root of creativity. It is the ability to bring to mind things that aren’t present to our senses.

Creativity is putting your imagination to work. It is applied imagination. Innovation is putting new ideas into practice. There are various myths about creativity. One is that only special people are creative, another is that creativity is only about the arts, a third is that creativity cannot be taught, and a fourth is that it’s all to do with uninhibited “self-expression.”

None of these is true. Creativity draws from many powers that we all have by virtue of being human. Creativity is possible in all areas of human life, in science, the arts, mathematics, technology, cuisine, teaching, politics, business, you name it. And like many human capacities, our creative powers can be cultivated and refined. Doing that involves an increasing mastery of skills, knowledge, and ideas.

Creativity is about fresh thinking. It doesn’t have to be new to the whole of humanity— though that’s always a bonus— but certainly to the person whose work it is. Creativity also involves making critical judgments about whether what you’re working on is any good, be it a theorem, a design, or a poem. Creative work often passes through typical phases. Sometimes what you end up with is not what you had in mind when you started. It’s a dynamic process that often involves making new connections, crossing disciplines, and using metaphors and analogies. Being creative is not just about having off-the-wall ideas and letting your imagination run free. It may involve all of that, but it also involves refining, testing, and focusing what you’re doing. It’s about original thinking on the part of the individual, and it’s also about judging critically whether the work in process is taking the right shape and is worthwhile, at least for the person producing it.

Creativity is not the opposite of discipline and control. On the contrary, creativity in any field may involve deep factual knowledge and high levels of practical skill. Cultivating creativity is one of the most interesting challenges for any teacher. It involves understanding the real dynamics of creative work.

Creativity is not a linear process, in which you have to learn all the necessary skills before you get started. It is true that creative work in any field involves a growing mastery of skills and concepts. It is not true that they have to be mastered before the creative work can begin. Focusing on skills in isolation can kill interest in any discipline. Many people have been put off by mathematics for life by endless rote tasks that did nothing to inspire them with the beauty of numbers. Many have spent years grudgingly practicing scales for music examinations only to abandon the instrument altogether once they’ve made the grade. The real driver of creativity is an appetite for discovery and a passion for the work itself. When students are motivated to learn, they naturally acquire the skills they need to get the work done. Their mastery of them grows as their creative ambitions expand. You’ll find evidence of this process in great teaching in every discipline from football to chemistry.

Why is Creativity Important in Education?

At its core, creativity is the expression of our most essential human qualities: our curiosity, our inventiveness, and our desire to explore the unknown. As we navigate an increasingly complex and changing world, promoting creativity in education is more important than ever before.

Prisma is the world’s most engaging virtual school that combines a fun, real-world curriculum with powerful mentorship from experienced coaches and a supportive peer community

The Importance of Creativity

We are all creative people, whether you think of yourself as creative or not. It takes creative thinking to paint a picture, but it also takes creative thinking to figure out the right formula to use in a spreadsheet, to invent a twist on a chocolate chip cookie recipe, or to plan a birthday party. But some people are more practiced and comfortable in the creative process than others.

At its core, creativity is the expression of our most essential human qualities: our curiosity, our inventiveness, and our desire to explore the unknown. Using creativity, we are able to push the boundaries of what is possible, imagine new worlds, and find solutions to the most pressing problems facing our society.

In a world where automation looms to take over all but the most innovative tasks—ones that truly require unique thinking—how can we make sure the next generation is capable of creatively solving these problems? We founded Prisma precisely because we were concerned traditional forms of education weren’t up to the challenge of creating future innovators.

In this post, we will explore the importance of creativity in the education system, the role of creativity in students' emotional development, and the ways in which it can be taught .

Creativity in Education

Despite the vital role creativity plays in our lives, it is often undervalued and neglected in our educational system. We are taught to memorize facts and figures, follow rules and procedures, and conform to the expectations of others. This approach may produce technically proficient students, but it fails to cultivate the spirit of creativity at the heart of true innovation.

In a rapidly evolving world with increasing automation, the ability to think creatively and come up with innovative solutions to problems is critical. This is particularly true in education, where fostering creativity can help students develop important critical thinking skills, as well as prepare them for the 21st-century workforce.

Creativity=Critical Thinking

“There’s no doubt that creativity is the most important human resource of all. Without creativity, there would be no progress, and we would forever be repeating the same patterns.” -Edward de Bono

What does creativity have to do with critical thinking ? At its core, creativity is about problem-solving . This is a skill becoming increasingly important right now as the world rapidly changes. To keep up with these changes, young people need to be able to come up with creative ways to solve problems, and be able to adapt to new situations quickly.

At Prisma, learners engage in a workshop called Collaborative Problem-Solving twice per week. These workshops might involve a critical thinking simulation, like when learners had to choose which businesses to invest in, Shark Tank style; or a science simulation where they had to figure out how to power a city using a combination of resources. In real life, much of creative problem solving happens in teams, yet in many traditional schools, kids are asked to solve problems on their own.

To build the form of creativity that leads to innovative thinking, learners need complex, interesting problems to solve. Education needs to figure out ways to design these kinds of authentic problems to prepare learners to succeed.

Creativity & Social Emotional Skills

“The most regretful people on Earth are those who felt the call to creative work, who felt their own creative power restive and uprising, and gave it neither power nor time.” -Mary Oliver

One of the benefits of creativity is the role it can play in the development of emotional intelligence . As mentioned above, creativity is an essential part of what it means to be human. It feels good to make something and be proud of it! When learners are given the opportunity for creative expression, it can help them develop their self-esteem and build confidence .

Prisma learners complete a creative project every 6 weeks based on our interdisciplinary learning themes , and present their final projects during a celebratory “Expo Day.” LaShonda S., a Prisma parent, described how making a creative project for the first time impacted her son this way: “His sense of pride and accomplishment has gone through the roof. He has told all of our family and friends about his podcast.”

Building students’ creativity isn’t just about the warm and fuzzy feelings, though. Going through a creative process is tough, and can build resilience, grit , and tenacity. It’s much easier to follow step-by-step instructions than it is to brainstorm, ideate, and iterate on your own idea. Creative projects can help kids learn to take risks and embrace failure, which is always an important part of the creative process.

In addition, creativity can help students develop important social skills. When learners work on creative projects together, they learn to collaborate and communicate effectively. This is an important skill for the 21st-century workforce , where teamwork and collaboration are essential. Since Prisma is a virtual school, our learners go even further, learning how to collaborate on creative projects virtually with young people all over the world, much like many adults do in their jobs today.

Sign up for more research-backed guides in your inbox

- Prisma is an accredited, project-based, online program for grades 4-12.

- Our personalized curriculum builds love of learning and prepares kids to thrive.

- Our middle school , high school , and parent-coach programs provide 1:1 coaching and supportive peer cohorts .

Role of Creativity in the Education System

The education system has not always prioritized creativity. In fact, many education systems around the world have placed a greater emphasis on rote learning and standardized testing than on creativity and innovation.

Chen Jining, the president of Tsinghua University in China, once described the dichotomy between “A students” And “X students.” “A students” were those who followed all the rules, achieved excellent grades from kindergarten through high school, and aced standardized tests. Jining noticed what these Chinese students often lacked, however, was an aptitude for risk taking, trying new things, and “defining their own problems rather than simply solving the ones in the textbook.” (Mitchell Resnick, Lifelong Kindergarten ). The kind of creative people who could do those things could be thought of as “X students.”

High-achieving students who lack creativity are a major problem for any society who wants to solve problems, invent solutions, and innovate. What kind of learning environment might create a society of “X students” rather than just “A students”?

Creative Thinkers in Education

Fortunately, there are many educators and thinkers working to promote creativity in education. Sir Ken Robinson made a splash when he argued in a highly popular TedTalk and other writing & speeches that traditional education systems kill creativity.

Prisma’s curriculum was inspired by Seymour Papert , a mathematician and computer scientist who was a pioneer in the field of educational technology. Papert believed technology could be used to promote creativity and empower students to learn in new and innovative ways. He also believed creativity was a key component of the learning process, and that students should be given the freedom to explore and experiment to develop their creative thinking skills. His philosophy that learners learn most when engaged in a process of “ hard fun ” inspired the design of Prisma’s engaging curriculum themes & creative projects.

Another influential thinker in the field of creativity in education is Peter Gray , a psychologist and author who has written extensively on the importance of play and creative expression in children's lives. Gray argues play and creativity are essential for children's emotional and cognitive development and that schools should prioritize these activities to promote social skills and academic success.

Assessing Creativity

Unlike standardized tests, which (arguably) provide a clear measure of students' knowledge and understanding, creativity is more difficult to assess. This prompts some educators to dismiss its importance. However, there are ways to measure creativity, such as through creative projects and assessments focusing on problem-solving and critical thinking skills.

Before joining the founding team of Prisma, I researched creative assessment at Harvard. We discovered strategies such as assessing the process as well as the final product, allowing opportunities for peer & family feedback, and incorporating self-assessment and self-reflection helped reliably assess students’ creativity.

4 Ways to Teach Creativity

So how can teachers and homeschool parents foster creativity?

- Design a creative classroom environment , or make your home workspace more creatively inspiring. Of course, at a baseline, a creative learning environment may include materials like art supplies, building blocks, and maker tools, but kids can also be creative with digital tools like Procreate , TinkerCad , Canva , and plain old pen and paper. Remember, creativity is about ideas, not materials!

- Provide opportunities for brainstorming , encouraging students to come up with their own ideas. Instead of deciding in advance what learners will create and what the steps will be, consider coming up with the project together, or letting learners design their own . At Prisma, learners get multiple options each cycle for projects they can complete, and also have the opportunity to propose and design their own projects.

- Foster a creative mindset . This involves encouraging students to take risks and embrace failure, and helping them understand creativity is a process, not a product. At Prisma, this looks like using badges instead of traditional grades , and offering lots of opportunities for kids to reflect on not only what they made, but what they learned along the way. Don’t just give praise for what a learner completed, but their behavior during the process: for example, “I noticed how you changed your idea after you got peer feedback, what a great creative mindset!” instead of “Your drawing is really good!”

- Teach creative thinking skills explicitly . This can involve teaching students how to brainstorm effectively, how to find a creative flow state , and how to give & get feedback on their ideas. At Prisma, we use design thinking frameworks and teach learners the steps.

So what happens when schools decide to emphasize these strategies? Kids can do amazing things! As one Prisma parent describes, “ This year, my 10 year old designed her own ecosystem in TinkerCAD, started her own business with a functioning website, served as "Swedish Ambassador to the UN council" where she debated how to resolve the Syrian refugee crisis, coded her own game to educate others on Audio-Sensory-Processing-Disorder, and wrote her own fairy tale.”

Creativity is a critical component of education in the 21st century. By promoting creativity, you can help students develop important problem-solving and critical thinking skills, as well as foster their emotional and social development. While there are challenges to promoting creativity in the education system, there are also many educators and thinkers who are working to make creativity a priority in education. As we navigate an increasingly complex and changing world, promoting creativity in education is more important than ever before.

More Resources for Creative Education

Our Guide to Design Thinking For Kids

Our Guide to Entrepreneurship For Kids

Our Guide to Curiosity in Education

Our Guide to Interdisciplinary Education

Our Guide to Real-World Education

Join our community of families all over the world doing school differently.

Want to learn more about how Prisma can empower your child to thrive?

More from our blog

Recommendations.

Prisma Newsletter

- Our Mission

Creativity and Academics: The Power of an Arts Education

Increased self-confidence and self-understanding, enhanced communication skills, and improved cognition are among the many reasons for teaching the arts.

The arts are as important as academics, and they should be treated that way in school curriculum. This is what we believe and practice at New Mexico School for the Arts (NMSA). While the positive impact of the arts on academic achievement is worthwhile in itself, it's also the tip of the iceberg when looking at the whole child. Learning art goes beyond creating more successful students. We believe that it creates more successful human beings.

NMSA is built upon a dual arts and academic curriculum. Our teachers, students, and families all hold the belief that both arts and academics are equally important. Our goal is to prepare students for professional careers in the arts, while also equipping them with the skills and content knowledge necessary to succeed in college. From our personal experience ( and research ), here are five benefits of an arts education:

1. Growth Mindset

Through the arts, students develop skills like resilience, grit, and a growth mindset to help them master their craft, do well academically, and succeed in life after high school. (See Embracing Failure: Building a Growth Mindset Through the Arts and Mastering Self-Assessment: Deepening Independent Learning Through the Arts .) Ideally, this progression will happen naturally, but often it can be aided by the teacher. By setting clear expectations and goals for students and then drawing the correlation between the work done and the results, students can begin to shift their motivation, resulting in a much healthier and more sustainable learning environment.

For students to truly grow and progress, there has to be a point when intrinsic motivation comes into balance with extrinsic motivation. In the early stages of learning an art form, students engage with the activity because it's fun (intrinsic motivation). However, this motivation will allow them to progress only so far, and then their development begins to slow -- or even stop. At this point, lean on extrinsic motivation to continue your students' growth. This can take the form of auditions, tests, or other assessments. Like the impact of early intrinsic motivation, this kind of engagement will help your students grow and progress. While both types of motivation are helpful and productive, a hybrid of the two is most successful. Your students will study or practice not only for the external rewards, but also because of the self-enjoyment or satisfaction this gives them.

2. Self-Confidence

A number of years ago, I had a student enter my band program who would not speak. When asked a question, she would simply look at me. She loved being in band, but she would not play. I wondered why she would choose to join an activity while refusing to actually do the activity. Slowly, through encouragement from her peers and myself, a wonderful young person came out from under her insecurities and began to play. And as she learned her instrument, I watched her transform into not only a self-confident young lady and an accomplished musician, but also a student leader. Through the act of making music, she overcame her insecurities and found her voice and place in life.

3. Improved Cognition

Research connects learning music to improved "verbal memory, second language pronunciation accuracy, reading ability, and executive functions" in youth ( Frontiers in Neuroscience ). By immersing students in arts education, you draw them into an incredibly complex and multifaceted endeavor that combines many subject matters (like mathematics, history, language, and science) while being uniquely tied to culture.

For example, in order for a student to play in tune, he must have a scientific understanding of sound waves and other musical acoustics principles. Likewise, for a student to give an inspired performance of Shakespeare, she must understand social, cultural, and historical events of the time. The arts are valuable not only as stand-alone subject matter, but also as the perfect link between all subject matters -- and a great delivery system for these concepts, as well. You can see this in the correlation between drawing and geometry, or between meter and time signatures and math concepts such as fractions .

4. Communication

One can make an argument that communication may be the single most important aspect of existence. Our world is built through communication. Students learn a multitude of communication skills by studying the arts. Through the very process of being in a music ensemble, they must learn to verbally, physically, and emotionally communicate with their peers, conductor, and audience. Likewise, a cast member must not only communicate the spoken word to an audience, but also the more intangible underlying emotions of the script. The arts are a mode of expression that transforms thoughts and emotions into a unique form of communication -- art itself.

5. Deepening Cultural and Self-Understanding

While many find the value of arts education to be the ways in which it impacts student learning, I feel the learning of art is itself a worthwhile endeavor. A culture without art isn’t possible. Art is at the very core of our identity as humans. I feel that the greatest gift we can give students -- and humanity -- is an understanding, appreciation, and ability to create art.

What are some of the benefits of an arts education that you have noticed with your students?

New Mexico School for the Arts

Per pupil expenditures, free / reduced lunch, demographics:.

This post is part of our Schools That Work series, which features key practices from New Mexico School for the Arts .

- +44 (0)1782 491098

- Request information

- MSc Management

- MSc Management with Marketing

- MSc Management with Sustainability

- MSc Management with Data Analytics

- MSc Computer Science

- MSc Computer Science with Data Analytics

- MSc Computer Science with Artificial Intelligence

- MA Education

- MA International Education

- MA Education Leadership and Management

- MA Early Childhood Education

- MA Education Technology

- MPH Global Health

- MPH with Leadership

- On-campus courses

- Start application

- Complete existing application

- Admission requirements

- Start dates

The importance of embedding creativity in education

Creativity in an educational context is often thought of in terms of creative subjects such as music, art, and drama. These subjects certainly nurture creativity, but creativity is an integral part of teaching and learning across all subjects. It involves an active curiosity when seeing something for the first time and how we react to it. Sometimes this involves an element of risk-taking, which can be developed in the safe environment of learning.

Cultivating creative thinking amongst students is highly dependent on creative leaders being visible within the learning and work environments. For this reason it’s important that creative leadership is evident from primary school to high school or college, and on into higher education. Creative thinking should be encouraged amongst all stakeholders and considered a valuable quality that initiates individuals into responding flexibly and adaptively in their problem-solving and decision-making.

Creative leadership during the Covid-19 pandemic

The ongoing impact of the global pandemic upon the learning environment and how educational institutions respond, means that the need for school leadership which takes a creative approach is greater than ever. In the introduction to the final report on the Creating Socially Distanced Campuses and Education Project launched by Advance HE, it is noted that there are five faces of transformational leadership that have come to the fore:

- Crisis leadership

- Courageous leadership

- Compassionate leadership

- Collaborative leadership

- Creative leadership

Elaborating upon creative leadership, Doug Parkin, Principal Adviser for Leadership and Management at Advance HE, says,

“The academic endeavour is at its core a creative one. Even very technical and rigorously precise research has a creative basis. From the most complex curriculum review challenge to the most wicked interdisciplinary research question, creativity and positivity unlocks human potential at every stage. It ignites ideas, inspires, and develops focus, commitment and energy. And leadership can and should complement this by being creative and using creativity as the basis for communication, positivity and engagement.”

He also quotes Kimsey-House et al when he writes “People are naturally creative, resourceful and whole.” This is an important point as people sometimes believe that they are not creative when being creative is an inherently human trait that often simply hasn’t been developed. Continued professional learning and development can support head teachers and staff in fostering creative processes so that they can use them both in their approach to management and their teaching practice.

Expressing creativity in teaching

Teacher creativity can be expressed through preparation and development, originality and novelty, fluency, freedom in thinking and acting, sensitivity to problems, and flexibility in finding alternative solutions to problems. School leaders and principals are key role models in promoting creativity in the education system and when they lead by example, it’s easier for creative learning to take hold amongst both teachers and students. Professor Louise Stoll from the UCL Centre for Educational Leadership states that, “Creative leaders…provide the conditions, environment and opportunities for others to be creative.”

No matter how many inputs and initiatives towards creative learning are suggested by staff or students, if headteachers do not embrace a creative methodology, the outputs will be subpar. For this reason, leadership development is also a critical factor in school improvement through creativity. Those who are creative know that a school culture in which stakeholders are always learning only leads to more creativity, and that creativity is itself a vital part of facilitating learning – it becomes a virtuous cycle.

An interesting case study that involved both pupils and teachers is that of Manorfield Primary School in Tower Hamlets. Head teacher Paul Jackson explained in an article in Headteacher Update,

“We engaged an architect to design us a model classroom that would put teaching and learning at the centre. Pupils and teachers worked with him on ideas. The idea was that if that worked, it would become a ‘lab’ where we tested things and if they worked we would roll it out elsewhere. Our children visited hotels and offices to get design ideas and then reported their ideas back to the architect. The result was the transformation of a previously cluttered classroom into a modern, light, and airy space and we’re now applying the lessons that we learned to the conversion of two redundant offices into a new, inspiring Key Stage 1 library area. I think it was a good example of using outside expertise to challenge our thinking.”

This kind of creative work is hugely beneficial to learners of all ages, but particularly to young minds. By involving them in the shaping of their environment, their opinions on high level decision-making are validated. The children are the ones who will primarily be learning in the school space, so letting them know that their input is important has a positive impact on their learning and sense of agency. When learning spans both the classroom and real-world scenarios, creativity can really come to fruition as students see the real-life effect of their decisions.

How important is creativity in education?

Creativity is sometimes referred to as one of the key competencies of the 21 st century and is also intrinsic to sustainable development.

As the world increasingly faces challenges related to climate change, the education of the next generation is pivotal in helping to cultivate innovative thinking and problem solving to address sustainability issues. Creative education is not just a more fun and resourceful way of learning, it helps prepare children and young adults for creative work and the challenges of everyday life.

Take a creative approach with an MA Education Leadership and Management

The educational sector is changing in the wake of Covid-19 and the weak points that the pandemic restrictions exposed in the current structures of pedagogy. Educational leaders want their schools to be more resilient and their staff and students to be actively learning and collaborating beyond the restraints of traditional learning methodologies. When it comes to the success of remote learning, there are more dynamic ways to share information than simply through webinars, and creativity has shown how limits can be overcome.

If you’re looking for professional development that lets you consider these challenges of teaching and many more, while exploring creative leadership styles and leadership roles, a master’s in education could be for you. Find out more about the learning opportunities offered by a 100% online MA Education Leadership and Management and how you can register today.

Quick Links

- Accessibility statement

Advertisement

Creativity and Technology in Education: An International Perspective

- Original research

- Published: 09 August 2018

- Volume 23 , pages 409–424, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

- Danah Henriksen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5109-6960 1 ,

- Michael Henderson 2 ,

- Edwin Creely 2 ,

- Sona Ceretkova 3 ,

- Miroslava Černochová 4 ,

- Evgenia Sendova 5 ,

- Erkko T. Sointu 6 &

- Christopher H. Tienken 7

6902 Accesses

44 Citations

16 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

In this article, we consider the benefits and challenges of enacting creativity in the K-12 context and examine educational policy with regard to twenty-first century learning and technology. Creativity is widely considered to be a key construct for twenty-first century education. In this article, we review the literature on creativity relevant to education and technology to reveal some of the complex considerations that need to be addressed within educational policy. We then review how creativity emerges, or fails to emerge, in six national education policy contexts: Australia, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Finland, Slovakia, and the U.S. We also locate the connections, or lack of, between creativity and technology within those contexts. While the discussion is limited to these nations, the implications strongly point to the need for a coherent and coordinated approach to creating greater clarity with regards to the rhetoric and reality of how creativity and technology are currently enacted in educational policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Creativity and technology in teaching and learning: a literature review of the uneasy space of implementation

Danah Henriksen, Edwin Creely, … Punya Mishra

Sociocultural Perspectives on Creativity, Learning, and Technology

Creativity, Culture, and the Digital Revolution: Implications and Considerations for Education

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Creativity is commonly viewed as critical for twenty-first century learning and teaching (Craft 2010 ). Both scholarly and popular discourse point to the importance of creative thinking skills for learners, and much rhetoric focuses on the need to infuse it into education systems (Harris 2016 ; Runco 2014 ). Similar to the positioning of creativity, the ability to use digital technologies is also commonly seen as a core skill in twenty-first century. Indeed, it is often argued that the connection between technology and creativity is a key issue for twenty-first century education (for example see Page and Thorsteinsson 2017 ). On the surface, one might assume that education systems emphasize and support creativity in schools, or that teachers and learners are afforded opportunities in policy and practice to engage in creative work and thinking. However, the reality beyond the surface is not so simple, and the challenges of enacting creativity in education are substantial (Feldman and Benjamin 2006 ). It is not uncommon for creativity to be talked about as being enabled by and through technologies. It is no surprise that enacting creativity with and through digital technology is equally unclear and in need of greater clarity (Mishra and Henriksen 2018 ).

In this article, we the authors use our shared international context of EDUsummIT 2017 to review how creativity emerges in education systems across several national education policies—considering if, where and how this intersects with issues of educational technology. We begin by discussing and defining creativity in the literature. We then consider how creativity intersects with issues of educational technology, followed by consideration of the benefits and challenges to instantiating creativity in education. Drawing on our shared international context of EDUsummIT, the article explores what basic policy content around creativity looks like across several educational contexts. Following this, we consider how several national education policies enact (or fail to enact) creativity for teachers and/or learners. We end by identifying some broad themes and recommendations for policy makers.

2 Defining Creativity

The multifaceted and complex nature of creativity presents a challenge for many educational systems, which are often bound to standards or norms that seek clear, fixed or internally and externally consistent framing (Csikszentmihalyi and Wolfe 2014 ). School cultures can vary dramatically even within a single district, town, or region, let alone at national or international levels—and culture informs the distinctive ways that policy emerges into real-world practices (Jurasaite-Harbison and Rex 2010 ). There are a multitude of ways in which systems and cultures might enact (or fail to enact) creativity, and this is a concern for schools and systems that require clear guidance in policy and practice (Caena 2014 ).

Most definitions of creativity identify novelty and effectiveness as being two key characteristics of creative ideas or solutions (Plucker et al. 2004 ). Creativity, thus, can be described as the production of useful solutions to problems, or novel and interesting ideas and artifacts across domains (Amabile 1996 ; Oldham and Cummings 1996 ; Zhou and George 2001 , 2003). Beyond these common themes of newness or effectiveness, there are variations in definitions. The broadness, or lack of specificity, in how creativity is defined makes it difficult for practitioners to identify and facilitate it, in situ. Henriksen et al. ( 2016 ) explored where and how creativity is located as an interaction within a system of actors in education. They suggested that to infuse creativity into education systems, the field must attend to it at multiple systemic levels, including teaching, assessment, and notably, policy. This systemic view provides a foundation for the idea that it is valuable to consider systems of policy contexts for creativity in education.

The definitional challenge of creativity speaks to its ill-structured, multi-faceted nature, which is emergent, contextual, and complex in expression. This complexity and diversity of emergence within systems makes it challenging to instantiate creativity within the concrete realities of schooling. Creativity is clearly important for twenty-first century education, yet it is also open-ended and contested ground (Runco 2014 ). The problematic nature of and inconsistent understandings about creativity may make it difficult for teachers to know how to enact—particularly in the absence of policy guidance or exemplars. Likewise, policymakers often do not have an understanding of what creativity means in education (Craft 2003 ; Beghetto and Kaufman 2013 ); thus there are few clear parameters which educators can use to recognize and thus enhance creativity.

Perhaps it is only by recognizing the complexity and definitional challenges, and looking across policy contexts, that we can approach policy discourse in meaningful ways. Taking into account the complexity of creativity may help educators, researchers and policy makers understand the challenges of instantiating the concept into the bounded space of schooling.

3 Creativity and Technology in Twenty-First Century Education

Given the digital world in which education is increasingly situated, there has been much consideration of what teachers need to know to use technology effectively in the classroom, and the competencies needed to develop digitally-fluent, creative students (Mishra and Mehta 2017 ). This is partly due to what scholars refer to as an important emergent relationship between creativity and technology, and the apparent connection between innovation and digital technologies (Mishra and Deep-Play Research Group 2012 ). Unquestionably, the effects of globalization and digital technology advancement in our world have an impact on how humans now live, work, think, communicate and create (Zhao 2012 ). Digital tools, digital devices and applications are affording a new world of opportunities in which people can imagine, make and share in creative ways (Zhao 2012 ). As knowledge bases expand and our world becomes more complex, we need creative thinking to address twenty-first century problems (Florida 2014 ). Amid the shifting context of globalization and rapid digital change, creativity becomes that much more necessary in contemporary society. It also becomes increasingly vital in discussions of learning, particularly in technology-rich contexts (as described by Henriksen et al. 2016 ).

Yet before the field of education can address the complex relationship between creativity and technology, it must consider how creativity can be enacted in classroom settings and student learning experiences.

This is because, despite the rhetoric about the importance of supporting creativity in education (Runco 2014 ) scholars have noted that school systems still function in traditional ways, with rigid boundary lines between subjects, linear single-answer assessments, and restrictive practices for students and teachers (Collins and Halverson 2018 ). These constraints emerge largely due to broader policy goals that define what ought to be in the curriculum, and how this curriculum is to be instantiated. In this context that it becomes imperative to consider educational policies across the globe. Before delving into national educational policies, we examine some of the benefits and challenges of infusing creativity in education.

4 The Value of Creativity: In Education and Beyond

Creativity is closely connected not only with the artistic world and the creation of products, but also with science, engineering, innovative thinking and problem-solving. Creative people are increasingly demanded in the labor market (Ambrose 2017 ). Companies and entrepreneurs are cognizant that the key to success is an ability to create new knowledge (Žahour 2016 ).

Education has a pivotal role in fostering creativity and creative practices, and thus the skills needed to create new knowledge. Indeed, “schools and initial education play a key role in fostering and developing people’s creative and innovative capacities for further learning and their working lives” (Cachia et al. 2010 , p. 5). Creativity is central to societal progress and the formation of new knowledge—thus it is necessary for schools to pay attention to the construct. According to Loveless:

Education systems in the twenty-first century are having to adapt to the changes, aspirations and anxieties about the role of creativity in our wider society, not only in realising personal learning potential in an enriching curriculum, but also in raising achievement, skill and talent for economic innovation and wealth creation” (Loveless 2007 , p. 5).

Since the 1950s, psychologists have empirically examined the concept of human creativity (Plucker et al. 2004 ). Research has demonstrated substantial and lifelong intellectual, educational and developmental advantages associated with creative thinking (Torrance 1995 ; Blicblau and Steiner 1998 ). Educational psychologists and researchers have noted strong positive correlations between creativity and life outcomes, including life success (Torrance 1995 ), leadership in the workplace (Williams 2002 ), healthy psychological functioning, and strong intellectual/emotional growth (Runco 1997 ). Maslow ( 1962 ) and Rogers ( 1976 ) noted the overall beneficial impact that creativity has upon human development, mental health and self-actualization. In any of these studies done through the latter part of the twentieth century, creativity was viewed as a kind of thinking skill or habit of mind—whereas in earlier history it had often been thought of as an inherent talentor trait for special and gifted people. In viewing it as a thinking skill, it becomes more accessible through learning, growth and change.

Creativity is recognized as one of the most coveted psychological qualities; yet it is often misperceived as an inherent trait limited to unique individuals (Sternberg and Lubart 1991 ). This view has created a tension: educators recognize the importance of creativity but are unclear if or how it could be facilitated in classrooms. The problem of concrete implementation of creativity is at odds with the conviction across educational discourse that creative thinking is important (Sawyer 2015 ).

The international implementation of technologies in educational settings may be a way of grounding creativity in practice or could provide a tangible mechanism for fostering its development. However, there is comparatively little scholarship that has explored the complex relationship between technology and creativity, though some work has recently begun to emphasize the connection (Henriksen et al. 2016 ). This connection between creativity and technology may have stemmed in part from changes in the economy and workforce, which has shifted dramatically in the last 50 years, due to accelerating shifts in digitization and mechanization. Specifically, more of the workforce has shifted from lower-skilled labor or manual jobs, to what Davenport ( 2005 ) referred to as knowledge work. Florida ( 2014 ) has spoken of this shift, warning the education and management sectors to avoid class divides between creative and non-creative knowledge workers. Given these new trends in the labor force, he notes that, “the only way forward is to make all jobs creative jobs, infusing…every form of human endeavour with creativity and human potential” (Florida 2014 , xiv). In other words, workers must not only develop knowledge-based skills, but also embody creative practices in work situations. However, it is not clear that there is any consensus on what these changes mean in the realities of policy and practice in work places, industry and in education.

5 National Policy Contexts