It takes a village: the Indian farmers who built a wall against drought

In rural Rajasthan, villagers have taken action against climate damage by constructing water-saving walls, trenches and dams to revive their farmland

T he villagers of Surajpura have built a wall: a 15ft (4.5 metre) mud bulwark that snakes through barren land for nearly a mile, with an equally long trench dug beneath it. It might not look like it, but for the 650 residents who toiled on it for six months in 2022, it is an architectural marvel.

The wall passed its strength test last year when it stopped rainwater runoffs, and the trench channelled the water to parched farms in the drought-prone region of Rajasthan in north-west India , reviving them for the first time in more than two decades.

Since then, Surajpura’s residents have seen their farms come back to life, their wells refilled and the land become alive once more with migratory birds. Villagers who had left to find work have also returned to their farms.

“Our village received good rainfall until about 20 years ago” says Hemraj Sharma, standing in the middle of his lush wheat crop fed by water from a nearby well, clean enough to drink. “But major droughts and poor rain led to our wells drying up. Our farm yields hit zero. We had just one harvest cycle for years.”

“We see a drought once every three years. Last year was a drought year, too, but this time around we had water. The wall worked,” says Sharma, who worked in a textile mill in neighbouring Bhilwara city until a few years ago. The water scarcity had also led his brothers to migrate to the city, where, like him, they worked 12-hour shifts for 5,000 rupees (£50) a month.

Sharma had feared that he would lose his farmland to the climate emergency, before the entire village came together to avert the crisis. “More than 40 of the 100 wells in the village have water now,” he says.

R ajasthan, India’s largest state, is among the most vulnerable to droughts, with 98% of its 250 village blocks in sectors marked as “dark zones” – areas with dangerously low groundwater levels – and almost 7% of the land uncultivable, according to Shantanu Sinha Roy, the Rajasthan head of the Foundation for Ecological Security (FES), a land conservation organisation.

More than half of the world’s major aquifers are being depleted faster than they can be naturally replenished, the United Nations warned last year, and India is among the countries most at risk of groundwater plummeting to levels that existing wells cannot access.

In Surajpura, while rain is scarce in the sowing months of July to October, unseasonal rainfall in winter damages standing crops. Worse, the village’s poor soil quality prevents water soaking through.

For climate advocates, Surajpura’s wall is a case study in climate resilience. It was built as part of the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGA), a government-run social welfare policy and one of the world’s biggest job programmes. The scheme guarantees 100 days of manual labour a year to rural households that request it, and has been credited with cushioning some of the country’s poorest communities from the devastating blow of droughts and floods in the past years, as well as during the Covid-19 pandemic. But now, climate activists are increasingly citing its role in building water security in villages, amid growing climate uncertainties.

“The scheme should no longer be viewed as an instrument solely for job creation,” says Roy . “It is a climate action tool. It is the only way to protect our future.”

Surajpura is not the only community in the region that is tackling water scarcity with the help of the MGNREGA scheme. In Baldarkha village, about 10km (6 miles) from Surajpura, villagers dug contours and trenches across 8 acres (3 hectares) of barren land about three years ago turning it into a fertile grazing field for their animals – even when the ponds dried up after no rainfall last year.

In Makarya village, home to about 500 people and about 120km from Surajpura, the villagers have created another pastureland spread over 50 acres. They dug trenches and check dams on the wasteland to stop rainwater runoff and planted medicinal herbs and local tree species . The revived land has inspired a neighbouring village to utilise its wasteland in a similar fashion.

after newsletter promotion

However, there are some concerns about the scheme. Researchers say that its budgetary allocations have fallen over the past three years and its new digital system – whereby a supervisor logs attendance on a smartphone – is a stumbling block in villages with bad network, exacerbating payment delays that have affected job creation and demand.

The government has denied poor funding and says MGNREGA is a demand-driven programme , which has been granted additional funds in the past three years.

B ack in Surajpura, the wheat crop sways in the breeze as villagers gather to tell the story of the wall they built. Among them is Sayari Kumavat, 50, a farmer. “I worked very hard on it,” she says. “I did get paid for each day’s labour but I also volunteered to work for free. This was going to benefit the village and me. I got water in my well.”

More rainwater seeping into the earth has recharged aquifers and improved groundwater quality, which means women in the village no longer have to make a four-hour trek to fetch water from a distant well.

Last year, the village welcomed back painted storks, migratory birds that had disappeared years ago. Several men who had moved to work in Bhilwara’s textile mills or to dig borewells in other states also returned.

Mahavir Jat, 28, worked in Jammu for six years, earning 10,000 rupees a month digging borewells. He now leases a farm and rears two buffaloes, earning 3,000 rupees a day from selling their milk. “I don’t see the need to migrate now,” he says.

Surajpura village council head, Ramlal Jat, a trained lawyer who led the wall project, says nearly 60% of the people who migrated from the village have returned. “People are investing in animals, since water and fodder are now available. We want to revive agriculture-linked livelihoods in our village.”

He is now seeking funds to strengthen the wall.

Meanwhile, farmers like Sharma have found a rare calm in their fields and a feeling of optimism. He plucks a carrot from a friend’s farm and chews on it as he speaks about the 50 quintals of wheat he reaped on his three-acre farm, the first such yield in more than two decades.

“ Gajab hariyali hai (it’s amazingly green),” he says.

- Climate crisis

- South and central Asia

Most viewed

- Firstpost Defence Summit

- Entertainment

- Web Stories

- Health Supplement

- First Sports

- Fast and Factual

- Between The Lines

- Firstpost America

Drought in Rajasthan: Poor groundwater situation, erratic rains in Barmer indicate ecological distress across Thar desert

With agriculture and cattle rearing being the only means of livelihood for locals of Thar desert, persistent drought has forced residents to migrate to other regions within the state while many others continue to cope with cascading effects of drought.

)

Editor’s note: Rajasthan’s relationship with summer is not a pleasant one. The shortage of water in the region only adds to the misery of the people. Even before the onset of summer, over 5,000 villages in nine districts in Rajasthan — Barmer, Churu, Pali, Bikaner, Jaisalmer, Jalore, Jodhpur, Hanumangarh and Nagaur were declared ‘drought-affected’ by the state government. The drought in this area affects the economy of the region as employment options dry up and people start migrating to neighbouring states like Gujarat to survive. This five-part series will examine the reasons and problems related to one of the worst drought conditions in the region. This is the first-part of the series.

Barmer: Barmer district in Rajasthan is evidence of alarming changes in ecological indicators across the Thar desert. While total rainfall received in the region has registered an increase, its uneven distribution during monsoon season has affected crops putting farmers in distress. In 2017, Sheo-Kawas and Dhorimanna-Gudamalani belt of Barmer district received 245 mm rainfall just in last week of July which caused flood-like conditions in many parts of the district, but the state government same year had to declare 1,900 out of 2,775 villages of the district ‘drought-affected’.

With agriculture and cattle rearing being the only means of livelihood for locals of Thar desert, persistent drought has forced residents to migrate to other regions within the state while many others continue to cope with cascading effects of drought, which hampers agricultural production, results in shortage of drinking water and fodder, and affects both, human and animal health. Crop loss and low purchasing power have pushed the region into poverty.

Of the total cultivated 15,73,029 hectare land in 2016, crops on 10,95,230 hectare were destroyed due to the failure of monsoon. While the losses were not as bad in 2017—crop loss of 6,88,095 hectare of the total cultivated 15,50,213 hectare in 2018—saw a severe drought as crops grown on 12,61,513 hectare were lost of the total cultivated 15,18,190 hectare area.

The rural population of Barmer depend on the government to provide relief during times of drought whose inefficient management of relief efforts pushes them towards the common practice of seasonal migration.

Erratic rainfall

This strange phenomenon where the district has registered an increase in average rainfall over the years but also had to face drought almost every year in the last decade has posed a challenge in this largely rainfed agricultural region. While the average rainfall of the district was 275 mm in the last 10 years, it is 343 mm at present.

Of the total geographical area of 28,17,332 hectare, 18,63,365 hectare in Barmer is cultivable area. Of the total cultivable area, about 80 percent is rainfed region while rest is irrigated. Among the irrigated land, 5.15 percent area is irrigated with canal water while 31.09 percent is irrigated with open wells and remaining 63.73 percent using tube wells.

Pradeep Pagariya, a scientist at Krishi Vigyan Kendra in Barmer, says the region has been receiving more rainfall since past few years, but across a shorter period. Away from the normal monsoon of four months, the region now receives rainfall only for two months, which could even be limited to only a month at times.

Barmer in 2017 received 95 mm rainfall in June and 245 mm in July, but only 18 mm in August and saw no rain in September. Some parts of the district, approximately 208 villages of Dhorimanna, Gudamalani, Sindhary, Balotra and parts of Sheo tehsil received excess rainfall and faced flood situation, which also affected the crops. The district administration takes into account the crop assessment report to declare a district ‘drought-hit’.

Overexploitation of groundwater

Western Rajasthan, which encompasses Jalor, Barmer, Jaisalmer, Jodhpur and Bikaner districts, comes under an arid zone that has a high temperature, low humidity, low rainfall, erratic and poor textured soils. Agriculture system in this region is mostly rain-fed, mono-crop and of subsistence type because of climatic constraints. Water scarcity is a serious problem in the region with good rainfall expected only in an interval of three to four years. Rainfall data of the last 100 years shows the region has dealt with famines in 61 seasons, of which 24 were severe famines, while the rest were medium. A recent report of Central Arid Zone Research Institute (CAZRI) claims the Thar desert has been witnessing major climatic changes over past decades. According to the report, Thar witnessed about 17 thunderstorms annually in 1966, which has now reduced up to 2.5 per year. The trend of shifting sand dunes has also affected weather patterns.

These conditions have led the farmers of Barmer to look towards other sources of irrigation for their crops. With easy access to pumping instruments, groundwater is being drafted at an alarming rate. Approximately 2,000 tube wells have been dug in this region and high dependency on groundwater has resulted in its over-exploitation, says Pagariya.

Barmer was declared ‘over exploited’ region in the Ground Water Assessment Report 2013 prepared by Central Ground Water Department, which revealed the overdraft at 123.85 percent per annum. Six out of total eight blocks were categorised as ‘over exploited’ while one was declared ‘critical’. Baitu block in the district, with 226 percent overdraft, was notified as ‘Dark Zone’.

Another alarm in the report was that while the district’s groundwater recharge rate was 278.01 million cubic metre, the consumption rate was 312.14 million cubic metre. The groundwater level in the district has been declining at a rate of 5-6m each decade, according to the report.

Government’s fault: Foreign flora

AK Changani, Head, Department of Environment at MGS University, Bikaner says, “Extraction of groundwater has increased. Population density is increasing. Local flora and fauna are shrinking because of the uncontrolled growth of weeds and shrubs. Sand dunes are now covered with layers of Prosopis Julifolra ( Vilayati Babool ). This affects the natural phenomenon of sandstorm and rainfall distribution.”

In this region, groundwater is available at three to four hundred feet deep. Due to which earlier people could not able to get the water for agricultural purpose. But with advanced technology, people are now able to access deep groundwater. As a consequence of it, there is a sharp increase in tube wells.

Pagariya says that changes in groundwater table and an increase in average rainfall and irrigated area have together increased the humidity in the region. He claims that the humidity in the region was around 10 percent two decades ago but has jumped to 35 percent at present.

The government initiatives, like the Desert Development Programme (DPP) launched around two decades ago to control desertification and adverse effects of drought, have only added to climate woes, according to experts. Sand dunes accounted for 54 percent area of the state in 1990, which has now come down to 48 percent. Pagariya blames this ecological imbalance on plantation of foreign flora species, such as the Israeli Tortilis by the forest department in order to stabilise the sand dunes while ignoring traditional native species such as Khejri (Prosopis Cineraria), Jaal (Salvadora Persica), Kummat (Acacia Senegal), Gunda (Cardio Mixa) and Rohida (Ticumula Undulata). While arguing that the varieties planted by forest department were not conducive to the ecology of the region, Pagariya vies for dense plantation and other sand dune stabilisation methods that haven’t been explored.

Environmentalist Bhuvnesh Jain says traditional plants are familiar with the desert ecology being natural species of the region. Tampering with nature results in punishment, says Jain, adding that traditional plant species not only balance the climate cycle in the desert region but also support the rural economy by providing a source of additional income to rural Indians since decades.

The author is Barmer-based freelance writer and a member of 101Reporters.com.

Find us on YouTube

Related Stories

)

Weather report: Cyclone in early March may damage crops in north India

)

Japan slips into recession, loses spot as world's third-largest economy to Germany

)

Why a legal guarantee of MSP is fraught with challenges

)

Biggest strength under PM Modi is stability in policy, says FM Nirmala Sitharaman

)

Advertisement

Analyzing the extent of drought in the Rajasthan state of India using vegetation condition index and standardized precipitation index

- Original Article

- Published: 30 January 2021

- Volume 8 , pages 601–610, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Deeksha Mishra ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3678-8154 1 ,

- Suresh Goswami 1 ,

- Shafique Matin 2 &

- Jyoti Sarup 1

614 Accesses

19 Citations

Explore all metrics

Drought is the most complex but least understood of all natural hazards that impacts around 55 million people globally every year. A hydrological drought (drought here after) is when the lack of rainfall goes on long enough to empty rivers and lower water tables and causes severe water shortage. In recent years, Geographic Information System (GIS) and remote sensing (RS) have played a crucial role in studying different hazards either natural or man-made. This study stresses upon the use of RS technique for drought risk assessment in Rajasthan state of India for the year 2002 and 2019. In this study, an effort has been made to analyze the extent of drought using two drought indices, namely vegetation-based vegetation condition index (VCI) and meteorology-based standardized precipitation index (SPI). For VCI calculation, which indicates impact of soil moisture on vegetation, we used moderate resolution imaging spectroradiometer (MODIS), Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) data from year 2000 to 2019. Monthly SPI was calculated using rainfall data obtained from the Rajasthan water resource department. SPI values were interpolated to get the spatial pattern of meteorological drought. Whole area categorised into five drought classes including extreme drought, severe drought, moderate drought, mild drought and no drought, following the recommended value breaks. The results revealed that about 83.87% area was under drought in the year 2002 thus considered as drought year. It has also been calculated that only 15.62% area was showing drought condition in year 2019 especially in the western part of Rajasthan. Correlation analysis performed between VCI and SPI resulted in a coefficient of correlation of 0.92 and 0.79 in year 2002 and 2019, respectively. The high correlation endorses the reliability of RS data for drought-related analysis.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Climate change and drought: a perspective on drought indices.

Study loss of vegetative cover and increased land surface temperature through remote sensing strategies under the inter-annual climate variability in Jinhua–Quzhou basin, China

Assessment of inundation extent due to super cyclones Amphan and Yaas using Sentinel-1 SAR imagery in Google Earth Engine

Alam U (2005) Drought and water crises: science, technology, and management issues edited by DA Wilhite. CRC Press, European Environment. 16(6):378-9

Belal A-A, El-Ramady HR, Mohamed ES, Saleh AM (2014) Drought risk assessment using remote sensing and GIS techniques. Arab J Geosci. 7:35–53

Article Google Scholar

Brown JF, Wardlow BD, Tadesse T, Hayes MJ, Reed BC (2008) The vegetation drought response index (VegDRI): a new integrated approach for monitoring drought stress in vegetation. GISci Remote Sens 45(1):16–46

Hagman G (1984) Prevention better than cure: report on human and natural disasters in the third world. Swedish Red Cross, Stockholm

Google Scholar

Justice C, Townshend J (2002) Special issue on the moderate resolution imaging Spectro -radiometer (MODIS): a new generation of land surface monitoring. Remote Sens Environ 83:1

Kogan FN (1995) Application of vegetation index and brightness temperature for drought detection. Adv Space Res 15(11):91–100

Linsley RK Jr, Kohler MA, Paulhus J (1975) Hydrology for engineers, 2nd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Mala S, Jat MK, Pradhan P (2014) An approach to analyse drought occurrences using geospatial techniques. 15th Esri India User Conference

Matin S, Behera MD (2017) Alarming rise in aridity in the Ganga river basin, India, in past 3.5 decades. CurrSci 112(2):229–230

Matin S, Sullivan CA, Finn JA, Green S, Meredith D, Moran J (2019) Assessing the distribution and extent of High Nature Value farmland in the Republic of Ireland. Ecol Indic 108:1–11

Panu US, Sharma TC (2002) Challenges in drought research: some perspectives and future directions. HydrolSci J 47:S1, S19–S30

Rathore MS (2009) State level analysis of drought policies and impacts in Rajasthan, India. Working paper 93, Drought Series, Paper-6 ( http://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/ucldc-nuxeo-ref-media/b104030f-61b9-4a96-83ec-f132df5a00c1 )

Seiler RA, Kogan FN, Wei G (2000) Monitoring weather impact and crop yield from NOAA AVHRR data in Argentina. Adv Space Res 26(7):1177–1185

Thiruvengadachari S, Gopalkrishna HR (1993) An integrated PC environment for assessment of drought. Int J Remote Sens 14(17):3201–3208

Tucker CJ (1979) Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sens Environ 8:127–150

Wilhite DA (2000) Drought as a natural hazard: concepts and definitions. In: Wilhite DA (ed) Drought: a global assessment, vol 1. Routledge Publishers, London, pp 3–18

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Maulana Azad National Institute of Technology, MANIT, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, 462003, India

Deeksha Mishra, Suresh Goswami & Jyoti Sarup

Environment Protection Agency (EPA), Co, Wexford, Ireland

Shafique Matin

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Deeksha Mishra .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Mishra, D., Goswami, S., Matin, S. et al. Analyzing the extent of drought in the Rajasthan state of India using vegetation condition index and standardized precipitation index. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 8 , 601–610 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-021-01102-x

Download citation

Received : 04 July 2020

Accepted : 02 January 2021

Published : 30 January 2021

Issue Date : March 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-021-01102-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Vegetation condition index (VCI)

- Standardize precipitation index (SPI)

- Moderate resolution imaging spectroradiometer (MODIS)

- Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI)

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Personal Finance

Disaster Risk Reduction Drought Mitigation in Rajasthan: A Case Study

Disaster Risk Reduction

Drought mitigation in rajasthan: a case study, storing rainwater in rajasthan.

In Rajasthan, traditional underground cisterns have been established and accepted as good practice by the government who have chosen to build 10 more in Judiya Village to help prevent migration

In the past 15 years, climate extremes such as flooding, drought, cyclones and mud slides have caused about 85% of deaths related to natural disasters and over 60% of the financial damage. Extreme weather events unfortunately are becoming more common due to climate change, so we need to be better prepared.

Communities can make plans to reduce the impact of future hazards such as cyclones, flooding or drought. If outside organisations help to lead community discussions, they can share useful ideas from other places and build people’s confidence to make changes. In India, staff of the

Discipleship Centre (DC), a Tearfund partner, have carried out participatory disaster risk assessments with many vulnerable communities. They help them to consider likely hazards (such as drought or cyclones), and assess who and what would be affected. Then they help them to plan how to reduce the risks, building largely on the skills, resources and abilities available within the communities.

Community Advocacy Work in Rajasthan

Staff from DC work with five villages near Jodhpur. They help local communities to assess the risks of future droughts and other problems and consider how they could develop their capacity to respond. Through this exercise, a Village Development Committee (VDC) was formed. This committee provides the first opportunity for men and women of different castes to meet together to make decisions.

Discipleship Centre staff help the committee members to gain confidence and share ideas from other parts of India. From these meetings, two ideas have proved very successful in lessening the impact of future droughts.

Rainwater Cisterns

Shortages of drinking water are a major concern during times of drought.

The Indian government is opposed to the building of more tube wells as ground water levels have fallen considerably. The VDC made the decision to build rainwater cisterns. These are about 3–4 metres wide and 4 metres deep. During the rainy season, rainwater is collected by channels which run into the cistern. Each cistern can store 40,000 litres and is shared by three families. When full, the cistern can provide drinking water for these families all year round. It could also be used to store water brought in by tankers in times of drought.

Rainwater cistern in a remote village in Rajasthan.

Photo: Oenone Chadburn

Discipleship Centre provided training and materials to help the community build one cistern using cement. However, one cistern was not enough to meet village needs. Motivated by their new awareness and understanding, the village committee decided to take their cause to their local government meeting, the Gram Sabha. DC staff helped the committee to make a formal application and provided advice on how to present their case in the meeting. Both male and female members of the committee attended and the women were highly motivated by their new ability to represent their own causes. As a result of this application, the government have promised to build another ten cisterns for the village over the coming months. Five have so far been completed.

Rainwater Bunds

Another idea which DC staff shared with committee members was to restore traditional practices that had been abandoned or forgotten. One of these was to conserve water by making bunds. A bund is an earth wall, 1 –2 metres in height that is built around the field. A large ditch is then dug out in front of the bund. The bunds must follow the contour lines.

The bunds help to prevent soil erosion from wind and rain. They help to hold water in the soil by preventing rainwater from flowing away.

Villagers were mobilised by the VDC to dig a bund around the field of one of the village widows. This widow could not survive on what she could grow and had been forced to find work in a nearby stone quarry. Her children had to go with her as she had no-one to care for them at home.

This meant they dropped out of school and began working in the stone quarry as well.

Thirty men worked for 20 days for 60 rupees a day to create a bund and

DC paid them on a cash-for-work basis. After the bund was completed, the widow’s yield of millet doubled in the first year, and the field now provides a huge contrast with surrounding fields. Now others in the village also want bunds for their fields.

Rainwater Bunds in Rajasthan

Rajasthan state in India increasingly suffers from droughts. Local communities struggle to cope with the impact of the droughts.

This is because people generally have few reserves. They have small plots of land, use farming practices that depend on fertilisers and irrigation and live in isolated areas with few other work opportunities. Water shortages are becoming more common.

www.tearfund.org

100 Church Road, Teddington, Middlesex TW11 8QE

Challenge House, 29 Canal Street, Glasgow G4 0AD

Rose House, 2 Derryvolgie Avenue, Belfast BT9 6FL

Overseas House, 3 Belgrave Road, Rathmines, Dublin 6

Uned 6, Parc Gwyddoniaeth, Aberystwyth, Ceredigion, SY23 3AH

0845 355 8355 (ROI: 00 44 845 355 8355) [email protected]

Registered Charity No.

We are Christians passionate about the local church bringing justice and transforming lives – overcoming global poverty.

Related documents

Add this document to collection(s)

You can add this document to your study collection(s)

Add this document to saved

You can add this document to your saved list

Suggest us how to improve StudyLib

(For complaints, use another form )

Input it if you want to receive answer

Content Search

India: situation report on rajasthan drought 25 dec 2002.

Drought Situation in Rajasthan Widespread drought has given a tough time to Rajasthan in 2002. Failure of monsoon saw all the 32 districts of the state reeling under drought causing severe shortage of food, fodder, drinking water and employment opportunities. Almost all districts are suffering from sharp depletion of ground water. This year seems to be an extremely bad year for farmers, already hit by drought in the previous couple of years. With little output in kharif season, now the rabi crop is being adversely affected due to non-congenial temperature this winter. If the condition does not change in the coming months, rabi production may fall by 60 percent. This year due to scarce moisture content in soil, only 2586000 hectare area is sown under different rabi crops in comparison to 6097000 hectares of last Rabi season.

State government called upon all sections of societies to work in unison in extending relief to the drought-affected people of the state. The state Government has taken a series of measures to provide relief to the drought-hit people. These initiatives have added the new dimension to drought management in the state. Several Voluntary agencies also stepped in to lend a helping hand in the drought relief measures undertaken by state government, particularly in the field of cattle conservation and provision of drinking water.

A. Livestock and fodder:

Cattle and other livestock are the most important source of livelihood after Agriculture in Rajasthan, especially for the poor and occupy an important role in the economy. Animal Husbandry contributes over 19 percent to the net state domestic product. Rajasthan has, in fact, the highest livestock population in India, contributing nearly 40% of wool production and10% of all milk production in the country.

In the wake of drought conditions the cattle population of Rajasthan is severely affected, especially due to acute scarcity of fodder and water in the state. The state government has taken several measures for special care of cattle population in the state. Voluntary agencies and Gram Panchayats are involved in a big way to procure fodder from neighboring states and distributing the same in the scarcity affected areas. The District Collectors are directed to motivate these organizations to play a leading role.

Government efforts for saving livestock:

It is essential to care the animals as they are more drought prone. To face the problem of fodder scarcity due to severe drought, special measures have been taken from GOR to increase the sowing area and production of fodder to meet the requirements in the coming months. Government has encouraged farmers to increase the fodder production by providing them subsidy. This step resulted in sharp increase in sowing area of fodder during this rabi season. Total area sown under fodder crops is 165000 hectares against the target of 65000 hectares. Presently fodder is being transported from neighboring less affected district/states. Transport charges are being borne by the state government so in spite of fluctuations people get fodder at reasonable rates.

Progress of cattle conservation measures:

The state Government and other agencies have taken up cattle conservation measures and fodder supply in all the districts. As per requirement the fodder depots have been sanctioned and most of them are operational to cater to the fodder needs at subsidized rates. Cattle camps opened in almost all the districts and taking care of thousands of cattle. Ajmer, Bhilwara, Barmer, Bikaner, Churu, Jaisalmer, Jodhpur, Nagaur, Pali, Sawaimadhopur, Tonk and Sirohi districts have been given priority for sanctioning of fodder depot in the state.

So far 3263 depots have been started out of the total sanctioned 4022. Total 271645.53 MT fodder has been distributed through fodder depots. Apart from these, 848 cattle camps have been opened out of 1027 sanctioned and these take care of 250338 cattle. 524 Goshalas are also functioning in the state and these are providing shelter to 195547 cattle. Of these 102 cattle camps, 158 fodder Depots and 119 Goshalas are being run with the help of NGOs/Donors.

B. Drinking water and Health care:

This year, all the 41000 villages of Rajasthan have been declared scarcity hit. As per the assessment of Government, drinking water need to be transported through railways, truck and tankers in 12430 villages. GOR has the provision of Rs.5450 million for making arrangement for the supply of drinking water out of which Rs.2390 million would be granted by GOI. As per govt. sources, the ground water level in 177 blocks out of total 237 blocks has gone down to threatening level. The situation is crucial in the 11 blocks, which are declared as Dark Zones. In addition, per capita water availability is shrinking continuously, and it is currently less than 60% of the average requirement of 1000 cubic mt. /per year. According to Water supply department, presently drinking water is supplied once in three days in 9 towns, once in two days in 25 towns and daily in 188 towns.

At a meeting of the guidelines committee on relief measures, presided over by Chief Minister of Rajasthan, the Govt has decided to electrify the hand pumps to boost water supply. The decision has been taken as part of relief measures for the drought affected people and aims at improving drinking water supply for the villagers and cattle. It has been decided that the electrification of hand pumps in ten villages under every Panchayat samiti to strengthen the water supply system. All District Collectors have been instructed to implement the decision. Under the new system, handpumps in the chosen villages of every Panchayat samity would be given a single phase electric connection. Water from these hand pumps would be supplied through synthetic water tanks. For making water available to cattle, small tanks would be constructed by the PHED near wells. Private hand pumps and tube wells lying unused would be used for irrigation while wells would be used for supplying drinking water.

District Administration, NGOs and other agencies are making efforts to supply drinking water. Ajmer, Jaipur, Kota, Barmer, Churu, Jhalawar, Bhilwara, Rajsamand and Dungarpur have been given highest priority in this regard.

Master plans for Water conservation and water harvesting in 30 districts of Rajasthan have been prepared with the help of Remote Sensing technology.

GoR has prepared an emergency plan of Rs. 5180 million for 22430 habitations for drinking water arrangements in coming summer, out of which Rs.3560 million would be spent in rural areas and Rs.1620 million in urban areas. Government has started work on an emergency plan of Rs 106.5 million for worst drought hit 48 blocks of the state. In these blocks 860 hand pumps and 196 tube wells would be established to strengthen the drinking water supply system. District wise blocks and allocation of funds is as follows:

In the state 1269985 people from 2759 villages have been supplied drinking water through 2910 tankers till Dec.15, 2002. Out of this, 142 tankers with the help of NGOs/private persons benefited 123 villages.

Health and nutritional aspects are becoming a major concern due to recurrence of drought, especially for the vulnerable groups that includes pregnant/lactating mothers, infants, children and old-age people. People are forced to work in quite odd conditions. The administration has taken some measures for strengthening of health delivery system. Medical kits are placed at every work site having ORS packets, Chlorine tablets, folic acids etc. to provide first aid facilities to workers as and when required. Local medical staff has been instructed to visit the respective work sites/village time to time. Malnutrition in children also observed in some severely affected areas. Mid day meal is being given in form of Ghughari to schoolchildren to supplement the nutritional requirement.

C. Food security and employment

Since this is the 5th consecutive year of drought, the state government is under obligation to provide maximum employment to the most vulnerable section of societies namely agriculture labourers, small/marginal farmers and marginal workers. GOR is generating employment opportunities for the people in the state through drought relief as well as other departmental works. The total relief work started (no. of work-sites) are 79746 out of the total sanctioned 133685. The average daily wage per labor is Rs. 52.80. Apart from this 246091 MT of wheat has been distributed out of the total allocation of 700000 MT. Many food-security schemes have been announced by the govt. for different target groups. GOR has decided to extend the ongoing relief works to another 200000 people in the affected areas which would take the tally of those benefiting from drought relief works to 1.65 million. Out of this, 1.05 million would be employed under drought relief works, 0.16 million workers in Sampoorna Gramin Rozgar Yojna (SGRY), and the rest in other schemes.

In another important decision, GOR has decided to include poor people belonging to general category in drought relief works. Under the amended norms, first preference (75% of total labor) would be given to the people living under poverty line, the scheduled caste and scheduled tribe followed by other backward castes. The remaining 25% labor would be from the poor people belonging to general category. In addition to this, it has been decided to provide aid-on-request to old, pregnant and destitute women till July ‘03. To facilitate this aid, the funds sanctioned to district administration have been increased from Rs.200000 to Rs.350000. Under the proposed programme, each beneficiary would be provided with 50 Kg. of wheat and Rs.30.

The state govt. has decided to partly cover certain categories of private constructions under drought relief works. Govt. would pay 75% of the labor wages in the construction of a house by an individual. This would be in the form of wheat, while the individual have to pay the remaining 25% in cash. It would, however be applicable in cases of such individuals whose earnings are not beyond Rs.4000 per month and total cost of construction of the house does not exceed Rs.50000. The individual would have to bear the cost of material. To tap private resources in combating drought, the govt. has decided to extend the same facilities to NGOs and private donors involved in community works like building tanks, wells, ponds or other structures. In another important decision by GoR, Irrigated areas are also exempted from the revenue.

Sources of information:

Dept. of Relief, GoR Dept of Agriculture, GoR Public Health Engineering Department, Rajasthan Website of GoR/ Relief department Newspaper cuttings (Rajasthan Patrika, Hindustan Times, The Hindu, Times of India, Jaipur)

Compiled by National UN Volunteers based in Rajasthan

Related Content

Farmers of bundelkhand get govt relief cheques for rs 10 from state govt, act appeal india: assistance to drought affected - asin42, india: drought appeal no. 16/2003 final report, india: drought appeal no. 16/2003 operations update no. 3.

Researching the spread of drought and its potential negative impacts

I t is important for water management to understand how drought spreads. In a new study, researchers from the WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research SLF show that in every third case, atmospheric drought is followed by low water levels. More rarely does drought have a negative impact on groundwater.

With climate change, extreme climate events such as longer dry spells are becoming more frequent. This can have a negative impact on water management, for example in agriculture. If a large area suffers from drought, it becomes difficult to transport water for irrigation from one area to another.

Therefore, it is important to understand how drought simultaneously affects river levels and groundwater levels over large areas. Researchers at the SLF have now analyzed data from 70 river catchment areas in Central Europe to investigate how likely it is that different areas will be affected by drought at the same time. The study is published in Geophysical Research Letters .

Understanding spatial distribution

In their study, the researchers investigated the question of whether a precipitation deficit leads to a runoff deficit in the rivers and ultimately to a groundwater deficit. Their focus was on the spatial extent.

"We found that 30 percent of precipitation deficits lead to low water levels, which has a negative impact on groundwater in 40 percent of cases," says Manuela Brunner, author of the study.

"I had assumed that the longer a drought lasts, the more widespread it becomes. But this is not the case with groundwater," she explains. While the authors show that a runoff deficit is more widespread than the precipitation deficit causing it, the spatial extent of the groundwater deficit in turn decreases in comparison to the spread of the runoff deficit.

Soil layers influence the runoff

This discrepancy surprised the researchers, but can be explained by the different soil structures: porous material allows the water to seep away better and faster than loamy soil, for example. This is why the spread of the deficit can locally be delayed.

In addition, the aquifer can store a lot of water. Depending on the area, drought has no effect or only a very delayed effect on groundwater levels. "These are good news for irrigation," comments Manuela Brunner. Even if the rivers have dried up, neighboring groundwater reservoirs may still be partially filled.

The study also shows how challenging it is to predict the course of droughts due to the complexity of the water cycle. "The multitude of influencing factors makes it difficult to accurately predict whether a prolonged dry period will lead to dried-up rivers or a groundwater shortage," says the scientist.

More information: Manuela I. Brunner et al, Drought Spatial Extent and Dependence Increase During Drought Propagation From the Atmosphere to the Hydrosphere, Geophysical Research Letters (2024). DOI: 10.1029/2023GL107918

Provided by Eidgenössische Forschungsanstalt für Wald, Schnee und Landschaft WSL

Famines and droughts in Rajasthan

The state of Rajasthan is prone to famine and droughts, particularly the western-most districts consisting of Thar desert which often experience successive years of scarcity and droughts.

Types of droughts:

Put simply, a drought is a failure of rain, leading to moisture stress, that in turn leads to agricultural losses and other forms of social and economic hardship. There are many definitions and classifications of drought, including that of the National Commission on Agriculture (quoted in Bokil 2000) which has defined three types of drought:

- When crops are affected due to moisture stress and lack of rainfall.

- When there is more than 25 per cent decrease (from normal) in rainfall in any area.

- When recurring meteorological droughts result in decrease in surface water and groundwater levels.

Under this classification. if drought occurs in 20 % of the years in any area, it is classified as drought prone area and if the drought occurs in more than 40 % of the years. it is classified as chronically drought prone area .

Causes of droughts in Rajasthan:

Droughts in the Indian sub continent are mainly due to failure of rainfall from southwest monsoon. The root cause for failure of monsoon rainfall is cued to the widespread, persistent atmospheric subsidence, which results from the general circulation of the atmosphere. Recent studies on interactions between global circulations and drought showed that the EI Nino phase of the Southern Oscillations (EN SO) has the largest impact on India though drought.

Declaration of drought in Rajasthan:

The Scarcity Manual (formerly known as the Famine Code) for Rajasthan lays out the rules and procedures to be followed in declaring a drought.

While the Scarcity Manual includes many criteria, in practice, the State government has come to rely almost exclusively on the girdawari report and the losses in sowing and production reported therein. The girdawari report is a land-use report and is prepared by the patwari (land records official) of each panchayat. To calculate the losses, the current year’s figures are compared with area sown and production in “normal” years (defined as the average production for the past few years). On the basis of this, calculations of affected population are made. The other criteria in the Scarcity Manual include distress migrations, increase in thefts, news of starvation deaths, etc.

Difference between droughts and famine

While, droughts and famine may seem referring to same thing. However, in actuality there is a huge difference. F amine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, inflation, crop failure, population imbalance, or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accompanied or followed by regional malnutrition, starvation, epidemic, and increased mortality.

Frequency of Droughts in Rajasthan

Low rainfall coupled with erratic behaviour of the monsoon in the state make Rajasthan the most vulnerable to drought. Based on historical data the frequency of occurrence of droughts in the state is given in following table.

Loss due Famine/Scarcity condition in Rajasthan

Related posts.

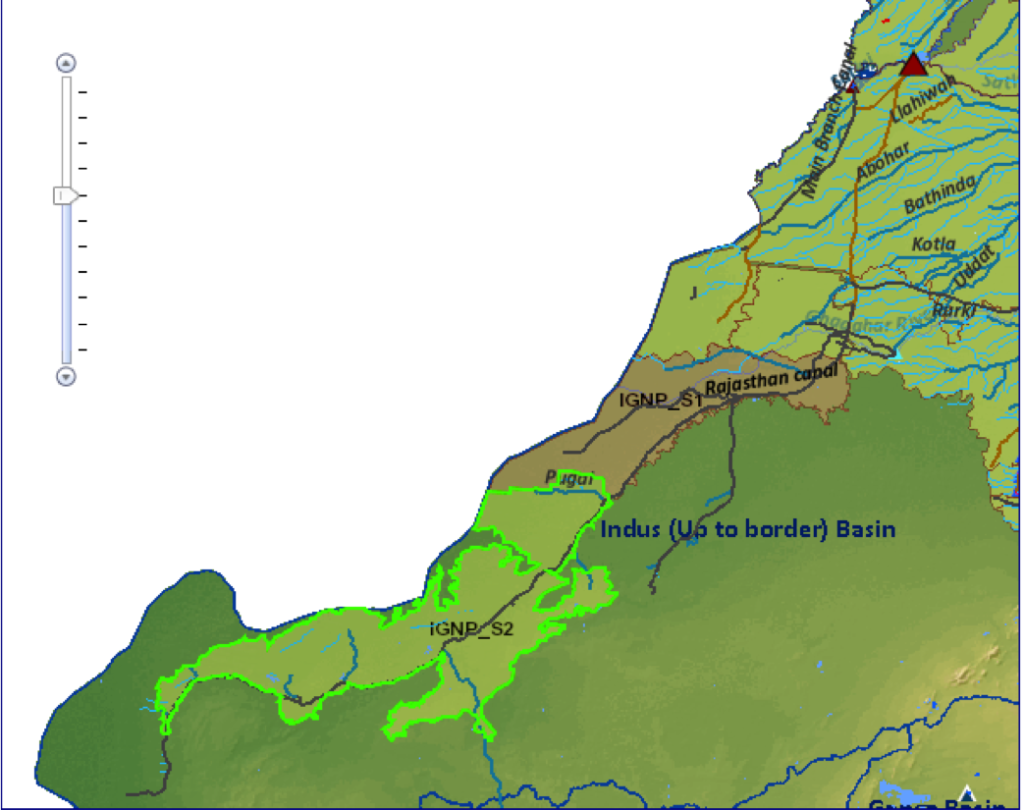

Rajasthan Irrigation: Indira Gandhi Canal

Rajasthan irrigation: list of medium scale irrigation projects, rajasthan budget 2016: snapshot, rajasthan budget analysis by prs.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The wall passed its strength test last year when it stopped rainwater runoffs, and the trench channelled the water to parched farms in the drought-prone region of Rajasthan in north-west India ...

65 percent below normal in Rajasthan and 26 percent below normal in Gujara#. Other States had higher defjciency but had irrigation systems. The impact of the drought of 2002 was felt most in Gujardt and ~ajasthm, which are otherwise also in the arid part of the country. Therefore these two States have been chosen for case studies in this Unit.

Editor's note: Rajasthan's relationship with summer is not a pleasant one.The shortage of water in the region only adds to the misery of the people. Even before the onset of summer, over 5,000 villages in nine districts in Rajasthan — Barmer, Churu, Pali, Bikaner, Jaisalmer, Jalore, Jodhpur, Hanumangarh and Nagaur were declared 'drought-affected' by the state government.

This study stresses upon the use of RS technique for drought risk assessment in Rajasthan state of India for the year 2002 and 2019. In this study, an effort has been made to analyze the extent of drought using two drought indices, namely vegetation-based vegetation condition index (VCI) and meteorology-based standardized precipitation index (SPI).

1.4The Rajasthan case study on linking climate adaptation The case study focuses on traditional adaptation practices used by vulnerable communities in a drought prone area: we have selected the Tonk district, in the state of Rajasthan, which experienced severe drought conditions during 2002. The communities have been chosen as they are the people

Rajasthan has more than 9 per cent of India's geographical area but only one per cent of India's total water resources. The climate is hot and dry in two-third of the State area. The average rainfall varies from 15 cm. in the western districts (50 per cent of the States area) to about 90 cm. in the eastern districts.

A drought is a failure of rain, leading to moisture. Currently, droughts are not treated as a regular feature of Rajasthan, but rather as sporadic events. In this section, we look at various indicators of drought and their shortcomings. The period un-der study spans approximately two de-cades - from 1981-2 to 2002-3.

In the case of Rajasthan, there have been 48 drought years of varied intensity since 1901. (last 102 years). A more detailed analysis reveals that only in 9 out of 102 years were none of the districts ... • Examine issues associated with drought declaration The study is based on secondary data published by various line departments of State ...

A hydrological drought (drought here after) is when the lack of rainfall goes on long enough to empty rivers and lower water tables and causes severe water shortage. In recent years, Geographic Information System (GIS) and remote sensing (RS) have played a crucial role in studying dierent hazards either natural or man-made. This study stresses upon

A case study of a watershed project in southern Rajasthan is used as an illustrative example. The findings demonstrate that watershed interventions focussed on hard adaptation options such as ...

Drought is a very common phenomenon over here. According to the Disaster management and Relief Department, the Western part of Rajasthan experiences drought very frequently (once in 3-4 years) whereas most of the Eastern part of Rajasthan experiences drought once in 5-6 years (Fig. 1). Download : Download full-size image; Figure 1. Study area.

A simplistic approach for monitoring meteorological drought over arid regions: a case study of Rajasthan, India

Click on the article title to read more.

Here, Chatterjee et al. (2005) present a case study of adaptation practices in two drought-prone villages in the Tonk district of Rajasthan. The villages of Dotana and Safipura rely on rain-fed ...

Drought Mitigation in Rajasthan: A Case Study . 2 . Storing rainwater in Rajasthan . ... In the past 15 years, climate extremes such as flooding, drought, cyclones and mud slides have caused about 85% of deaths related to natural disasters and over 60% of the financial damage. Extreme weather events unfortunately are becoming more common due to ...

of Rajasthan on water resources assessment. A summary of the key findings of the study analysis are presented below. Water use intensity analysis The study examines the existing water resources availability and the water allocation pattern with respect to the economic sectors in Rajasthan to calculate the water intensities for each sector:

Further, this study is the first to present a sensitivity analysis to identify significant indicators influencing drought risk in India. Therefore, this study presents an end-to-end drought risk assessment framework with recommendations that can aid long-term drought resilience in the country. Main conclusions of the study are summarised below. 1.

Drought mitigation in Rajasthan, India. Rajasthan, the largest state in India, has an estimated population of 54 million, spreading over 41,500 villages in 32 districts. Out of 32 Districts, 20 ...

In this study, using the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) we examined meteorological drought characteristics in the state of Rajasthan to identify three categories of drought events (mild ...

33 Case Study 2: India Community Adaptation to Drought in Rajasthan Kalipada Chatterjee, Anish Chatterjee and Sarmistha Das 1 Introduction Historic and continued high rates of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from anthr opogenic sources are re sponsible for current climate change. The atmospheric lifetime of these gr eenhouse gases ranges fr om ...

25 Dec 2002. Originally published. 25 Dec 2002. Drought Situation in Rajasthan Widespread drought has given a tough time to Rajasthan in 2002. Failure of monsoon saw all the 32 districts of the ...

It is important for water management to understand how drought spreads. In a new study, researchers from the WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research SLF show that in every third case ...

Droughts have extensive consequences, affecting the natural environment, water quality, public health, and exacerbating economic losses. Precise drought forecasting is essential for promoting sustainable development and mitigating risks, especially given the frequent drought occurrences in recent decades. This study introduces the Improved Outlier Robust Extreme Learning Machine (IORELM) for ...

In 2002, the Government of India acknowledged severe drought and scarcity in all 32 districts of Rajasthan. It recognized large number of deaths in Baran district as a result of this situation.

Recent studies on interactions between global circulations and drought showed that the EI Nino phase of the Southern Oscillations (EN SO) has the largest impact on India though drought. Declaration of drought in Rajasthan: The Scarcity Manual (formerly known as the Famine Code) for Rajasthan lays out the rules and procedures to be followed in ...