- High contrast

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

- Inclusive education

Every child has the right to quality education and learning.

There are an estimated 240 million children with disabilities worldwide. Like all children, children with disabilities have ambitions and dreams for their futures. Like all children, they need quality education to develop their skills and realize their full potential.

Yet, children with disabilities are often overlooked in policymaking, limiting their access to education and their ability to participate in social, economic and political life. Worldwide, these children are among the most likely to be out of school. They face persistent barriers to education stemming from discrimination, stigma and the routine failure of decision makers to incorporate disability in school services.

Disability is one of the most serious barriers to education across the globe.

Robbed of their right to learn, children with disabilities are often denied the chance to take part in their communities, the workforce and the decisions that most affect them.

Getting all children in school and learning

Inclusive education is the most effective way to give all children a fair chance to go to school, learn and develop the skills they need to thrive.

Inclusive education means all children in the same classrooms, in the same schools. It means real learning opportunities for groups who have traditionally been excluded – not only children with disabilities, but speakers of minority languages too.

Inclusive systems value the unique contributions students of all backgrounds bring to the classroom and allow diverse groups to grow side by side, to the benefit of all.

Inclusive education allows students of all backgrounds to learn and grow side by side, to the benefit of all.

But progress comes slowly. Inclusive systems require changes at all levels of society.

At the school level, teachers must be trained, buildings must be refurbished and students must receive accessible learning materials. At the community level, stigma and discrimination must be tackled and individuals need to be educated on the benefit of inclusive education. At the national level, Governments must align laws and policies with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities , and regularly collect and analyse data to ensure children are reached with effective services.

UNICEF’s work to promote inclusive education

To close the education gap for children with disabilities, UNICEF supports government efforts to foster and monitor inclusive education systems. Our work focuses on four key areas:

- Advocacy : UNICEF promotes inclusive education in discussions, high-level events and other forms of outreach geared towards policymakers and the general public.

- Awareness-raising : UNICEF shines a spotlight on the needs of children with disabilities by conducting research and hosting roundtables, workshops and other events for government partners.

- Capacity-building : UNICEF builds the capacity of education systems in partner countries by training teachers, administrators and communities, and providing technical assistance to Governments.

- Implementation support : UNICEF assists with monitoring and evaluation in partner countries to close the implementation gap between policy and practice.

More from UNICEF

The boy who changed his community in Serbia

How one boy overcame stigma and demonstrated the power of inclusive education.

I want to change how society sees people with disabilities

"When I came to school, I was determined to show everybody I could make it."

Children call for access to quality climate education

On Earth Day, UNICEF urges governments to empower every child with learning opportunities to be a champion for the planet

An entire generation of children in Sudan faces a catastrophe as the war enters its second year

Fixing the Broken Promise of Education for All

This report draws on national studies to examine why millions of children continue to be denied the fundamental right to primary education.

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities adopts a broad categorization of persons with disabilities and reaffirms that all persons with all types of disabilities must enjoy all human rights and fundamental freedoms.

Inclusive Education: Including Children with Disabilities in Quality Learning

This document provides guidance on what Governments can do to create inclusive education systems.

Towards Inclusive Education: The Impact of Disability on School Attendance in Developing Countries

Using cross-nationally comparable and nationally representative data from 18 surveys in 15 countries, this paper investigates how disability affects school attendance.

- IIEP Buenos Aires

- A global institute

- Governing Board

- Expert directory

- 60th anniversary

- Monitoring and evaluation

- Latest news

- Upcoming events

- PlanED: The IIEP podcast

- Partnering with IIEP

- Career opportunities

- 11th Medium-Term Strategy

- Planning and management to improve learning

Inclusion in education

- Using digital tools to promote transparency and accountability

- Ethics and corruption in education

- Digital technology to transform education

- Crisis-sensitive educational planning

- Rethinking national school calendars for climate-resilient learning

- Skills for the future

- Interactive map

- Foundations of education sector planning programmes

- Online specialized courses

- Customized, on-demand training

- Training in Buenos Aires

- Training in Dakar

- Preparation of strategic plans

- Sector diagnosis

- Costs and financing of education

- Tools for planning

- Crisis-sensitive education planning

- Supporting training centres

- Support for basic education quality management

- Gender at the Centre

- Teacher careers

- Geospatial data

- Cities and Education 2030

- Learning assessment data

- Governance and quality assurance

- School grants

- Early childhood education

- Flexible learning pathways in higher education

- Instructional leaders

- Planning for teachers in times of crisis and displacement

- Planning to fulfil the right to education

- Thematic resource portals

- Policy Fora

- Network of Education Policy Specialists in Latin America

- Publications

- Briefs, Papers, Tools

- Search the collection

- Visitors information

- Planipolis (Education plans and policies)

- IIEP Learning Portal

- Ethics and corruption ETICO Platform

- PEFOP (Vocational Training in Africa)

- SITEAL (Latin America)

- Policy toolbox

- Education for safety, resilience and social cohesion

- Health and Education Resource Centre

- Interactive Map

- Search deploy

- Our mission

- Thematic priorities

- Gender and equity in education

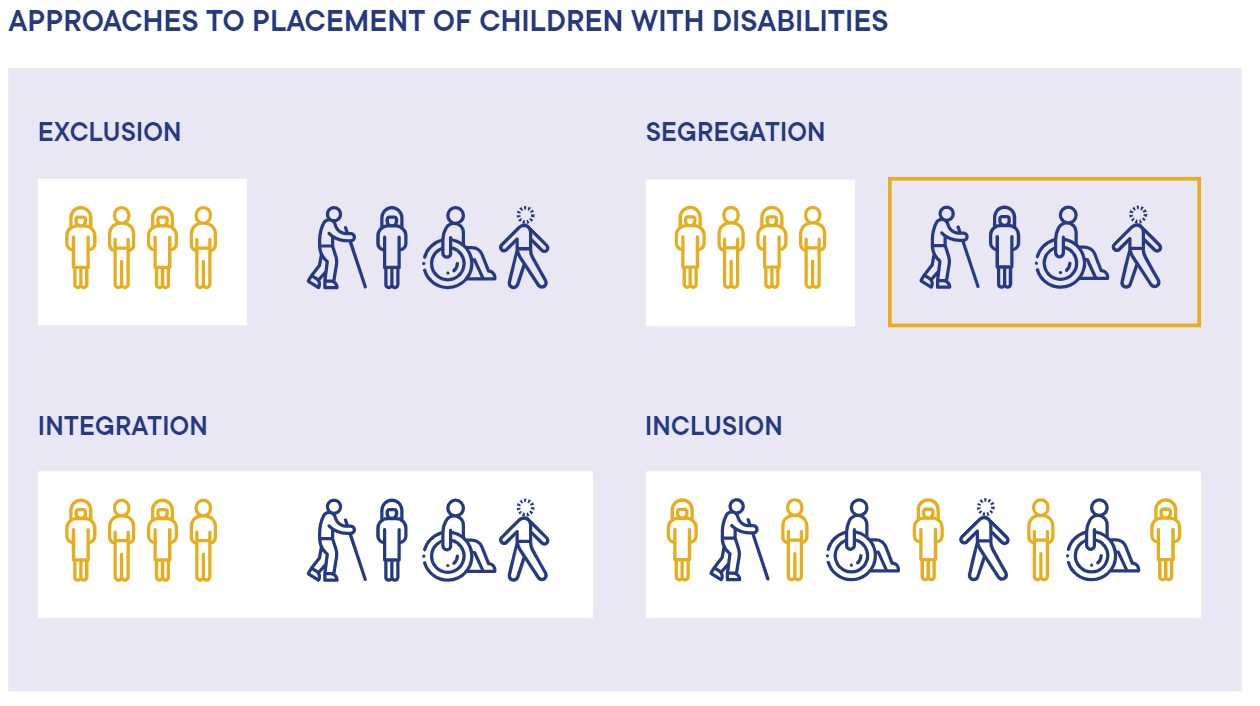

In an inclusive approach to education, all children can learn together, in the same classroom. In schools, disability is one of the main causes of exclusion. In addition, there are other obstacles to inclusive education, relating to social, material, and behavioural issues. Discover all of IIEP-UNESCO’s actions, activities, and resources to strengthen the capacity of countries to plan for inclusive education, which takes everyone’s needs into account.

While millions of children across the world do not have the opportunity to learn, people with sensory, physical, or learning disabilities are two and a half times more likely than their peers to never go to school. Making inclusive education a reality means reaching out to all learners, by eliminating all forms of discrimination. This challenge lies at the heart of the fourth United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal (SDG4) and the Education 2030 Agenda. Nevertheless, inclusive education is a complex process. It depends not only on supportive policies but more broadly on the cultural transformation of educational systems.

Since 2018, IIEP-UNESCO has been working to strengthen States’ strategies for inclusive educational planning and management, through actions to raise awareness and promote political dialogue on these issues, as well as training and research.

Raising awareness of issues in disability-inclusive planning

More than one out of every seven people in the world has a disability , according to the World Health Organization. Among the tens of millions of children affected, many do not have the opportunity to go to school, especially in low-income countries. Faced with a lack of data and knowledge on the identity and individual needs of these children, many countries do not know how to ensure their inclusion in their national education system. Persistent stigmatization, the often inadequate adaptation of schools, and the lack of training of teachers and materials to encourage inclusive education make access to school and learning even more difficult.

source_iiep-unicef_report_on_the_road_to_inclusion.png

While the transition towards inclusion has begun in several countries, so-called ‘segregated’ educational systems continue to prevail globally, according to UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring Report 2020 .

For the education of pupils with disabilities, national policies provide for a separate system in 25% of countries, an integrated system in 10 per cent of countries and an inclusive system in only 17% of countries. The remaining States apply a mixed system of segregated and integrated teaching.

Our round tables on inclusive education To help governments develop educational planning that is able to address the needs of all learners, IIEP organized two technical round tables , with the support and collaboration of the United Nations Children’s Fund ( UNICEF ). Representatives of 16 national ministries of education and disability organizations met to discuss the difficulties and progress in planning for fairer and more inclusive educational systems, particularly for children with disabilities.

- Round table ‘ Inclusion and disability in sectoral planning in education in Asia and Anglophone Africa ’, in Paris in 2018. Watch daily highlights .

- Round table ‘ Inclusion and disability in sectoral planning in education in Francophone Africa ’, in Paris in 2019

The conclusions and learning from these round tables led to a report, accessible online.

Read our report

Listen to Radio France Internationale’s report during the second round table

“Inclusive education can improve children’s success at school, strengthen their social and emotional development, encourage acceptance of others... and therefore also contribute to more inclusive societies. To take up this challenge, governments should engage in a process of holistic and systemic reflection, based on rigorous planning.” Jennifer Pye, IIEP inclusive education specialist

Inclusive education: Our training courses

The conceptual framework for disability-inclusive education, developed by IIEP and UNICEF, contributed to and helped structure an online course focused on the Foundations for disability-inclusive education planning.

This nine-week course, intended for officials in ministries of education working on issues of fairness and inclusion, has been delivered three times since 2020, with each session adapted to a regional context (Southern and East Africa; Asia; Southeast Asia and the Pacific). Overall, IIEP has trained more than 400 ministry of education officials worldwide. Read a participant’s testimony

The impact of this online course on the professional practices of participants is the subject of an evaluation , based on the outcome harvesting method and the Kirkpatrick model.

Find out about IIEP’s training courses

Inclusive education and technology: Our research

Information and communication technology plays a major role in filling the learning gap between pupils with disabilities and those without. Open and distance teaching has long been considered a useful tool to provide access to courses and educational materials that might be out of reach of some pupils. With the pandemic, these distance learning systems have suddenly become essential to maintain an educational link with as many pupils as possible. Yet these tools are still too rarely inclusive or accessible. IIEP conducts case studies on emerging practices in inclusive digital learning, in collaboration with the UNESCO Institute for Information Technologies in Education ( IITE-UNESCO ). In parallel, rapid assessments are conducted, in different national contexts, to measure the impact of COVID-19 on access to distance learning for pupils with disabilities. This work targets four countries:

- Colombia (case study in English , in Spanish ),

- Bangladesh ( case study ),

- The Republic of Mauritius ( case study | rapid assessment ),

- Rwanda ( rapid assessment ).

Webinars and reports:

- Webinar "Technology-enabled inclusive education: Emerging practices from COVID-19 for learners with disabilities" from Bangladesh, Mauritius, Rwanda (15 June 2021)

Webinar report

- Webinar "COVID 19, educación basada en la tecnología: Prácticas emergentes en el aprendizaje digital inclusivo para estudiantes con discapacidad" (in Spanish with Colombian sign language interpretation) (29 July 2021)

Webinar info note (in Spanish)

Webinar report (available soon)

This project follows directly from UNESCO’s action on disability inclusion through open and distance teaching, particularly during the pandemic. More broadly, it is part of a global programme of the United Nations Partnership On the Rights of Persons with Disabilities ( UNPRPD ).

Gender-sensitive and crisis-sensitive educational planning

Whether in terms of schools or learning, there are many obstacles to inclusive and fair education. These obstacles often mount up. Beyond the central question of disability, other forms of exclusion are therefore also taken into account in IIEP’s research, training, and technical support activities.

- IIEP strives to integrate gender equality at the heart of strategies and practices in the education sector. In particular, the Institute is responsible for the technical leadership of the Gender at the Center (GCI) initiative, through its office in Dakar. Launched in 2019 during the G7 summit, GCI aims to reduce gender inequalities in the education systems of eight sub-Saharan African countries.

- Similarly, as many countries face conflicts, epidemics, or natural disasters that are likely to exclude children from education, a crisis-sensitive planning approach is integrated into technical support services.

- In Eswatini, inclusive education turns a page

- Inclusive education: Overcoming barriers to technology

- Learning together: Inclusive education for refugees in Kenya

- All children in school together: the quest for disability-inclusive education

- Ghana: making inclusive education a reality

- Technical roundtable on inclusive education

- Technical Round Table: inclusive education for children with disabilities

- Technical Round Table: Inclusion of children with disabilities in education sector planning in French-speaking Africa

- National policies for inclusive education - Planipolis

- Blog post: ‘A school for all: what does it look like and where do we stand?’

- Data Dive Webinar: ‘Making schools inclusive for children with disabilities’

- Blog post: ‘Inclusive education starts with planning.’

- Read our opinion piece published by Devex: The urgent need to plan for disability-inclusive education

- Issue brief, ‘Disability inclusive education and learning’ – Learning Portal

- Privacy Notice

Inclusive education stories from the field

Leonard Cheshire has a longstanding relationship with UNESCO, providing disability specific technical expertise and advice as a formal partner.

As we work together to continue our global efforts towards the Sustainable Development Goals, these stories demonstrate the importance of inclusive education programmes in creating opportunities for persons with disabilities. From the implementation of assistive technology devices, to supporting families and communities in understanding and appreciating disability, to providing educational and vocational opportunities for girls with disabilities, each story shows the value of disability inclusive projects in creating a more equal world for all.

Alice’s quest for education despite life challenges and the COVID-19 pandemic

Alice Atieno Ouma is 18 years old and lives with her husband and child in Wakesi village, Muhoroni Sub-County, Kisumu County, Kenya. Alice is currently a beneficiary of the Education for Life project, where she’s been attending numeracy, literacy and life skills classes since she joined in February 2020. She has an intellectual disability and has shown herself to be an active and dedicated learner in class.

Alice attended lower primary school but dropped out due to family challenges and the lack of a supportive school environment. She was sent to Nairobi, Kenya where she did menial work for a few years. She later left and went back home and eventually got married. Alice heard about the Education for Life project through a community event organised by the project. She went to the catch-up centre where she completed project assessments and was later admitted into the programme.

“When they called that I had been chosen to be one of the 30 girls in our catch up centre I was very excited for the opportunity! I have been attending classes before we closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic,” Alice explained.

Alice enjoys going to the centre and has made lots of friends. Spending three hours, three days of the week in the centre has really helped her. “What I like most about being here is that my fellow girls are very kind to me and the teacher always says when we are at the centre we are a big family,” Alice said.

Alice’s life has changed a lot because of the project. First, her literacy levels have improved. She also does well in mathematics, her favourite subject. Through the life skills and mentorship sessions that she attends, her self-confidence has also improved. She vividly remembers a session where they were chatting about reproductive health and the mentor took them practically through using a sanitary towel step by step.

“It was a very fun session. We all laughed and learned a lot because who thought putting on a sanitary towel could be talked about openly!”

Life has improved for both Alice and her family, and her husband has been encouraging her throughout her studies. Her husband has also learned a lot about how to support her and understand her better through a workshop organised by the project for households of girls with disabilities. They were taught how to appreciate and support those living with disabilities.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused economic uncertainty in the community. It has been a difficult time for Alice and her family. Her husband works at a sugar cane farm as a casual labourer and his income has not been consistent. To mitigate this, and have additional income in the family, she has been washing clothes for her neighbours during her free time when she is not at the centre.

When the centre was closed after the COVID-19 pandemic first hit Kenya, the project adapted by providing the Educator Facilitators and Mentors with airtime to reach out to the girls every week. They provided psychosocial support and offered some learning by providing small assignments on phones to keep the girls active. Additionally, Alice was provided with workbooks (Mathematics, English, and Kiswahili) to aid her to study at home. She was also provided with a dignity kit (sanitary towels, soap, underwear, etc). These items were very useful and relieved her of the stress of having to source them for herself.

With learning now resuming at the catch up centre, Alice is optimistic about her future. She hopes one day to own her beauty salon. She is sure that with the support of the project’s role models and career guidance sessions she will choose the right transition pathway to help her achieve her goals.

With all the efforts that the project has made, Alice shared that there is more that can be done to support girls with disabilities. This includes continuous sensitization of the community to be more supportive of girls like her, improvement of the teaching and learning materials in the centres and encouragement and additional training for the teachers that support them.

“This is the best project to have ever come in my community,” Alice said. “It has been helpful to girls like me. I am very grateful and I hope other girls like me will benefit from this great initiative.”

Emmanuel’s Story – Finding his future

Emmanuel is a 14 year old boy from Kizimba Village, Agwingiri Parish, Agwingiri Sub County in Amolatar district in Uganda. He is the ninth born in a family of ten. Both he and two of his sisters have hearing and speech impairments.

When Emmanuel was ten years old his father died. His mother couldn’t afford to keep him in a school for disabled children and believed he wouldn’t cope in a mainstream school.

So, Emmanuel went to live with a friend of his brother’s in Kampala. The friend became Emmanuel’s guardian and provided funding for him to go to school again. However, during the third year of his education in Kampala, his guardian passed away and Emmanuel had to go back to Kizimba village to live with his mother.

Back in the village, his mother was still unable to pay for him to attend school. She said: “Emmanuel has been very lonely at home with no friends since most children in the community attend school.”

For a while, Emmanuel had no choice but to stay at home and help out with domestic chores. But Emmanuel’s chance to go back to school came when the team from Leonard Cheshire’s Inclusive Education project in Amolatar District in Northern Uganda came to his local area. Their aim was to teach the community about disability and reduce the stigma around it, as well as identify children that could be supported by the project.

Emmanuel registered with the project, and soon after was enrolled at Omara Ebek Memorial primary school in Amolatar district. The project also provided support with his school fees and materials. Emmanuel now has teachers who can speak in sign language, so he feels welcome and comfortable to learn. His teachers have described him as a bright boy, one of the best in class!

Not only is Emmanuel making great progress with his education, but he’s also been making lots of friends. He loves playing football with them. His mother says: “Emmanuel is now a happy boy with many friends and is very confident.”

Through the work of the project, Emmanuel’s community now believe that children with disabilities have a future through inclusive education. Emmanuel says he’d also like to become a teacher himself one day so that he can help other children like him.

Small changes, big impacts – the importance of inclusive learning environments

Esther Banda is a primary school teacher at one of schools participating in Leonard Cheshire’s Inclusive Education project in the Eastern Province of Zambia. She took part in inclusive teacher training in May 2019.

Around the time that the inclusive education project was introduced at their school in January 2019, Esther had started teaching Efita, a 10-year-old learner with epilepsy and other developmental impairments. It was Esther’s first time teaching a student with a disability, and it was the first time that Efita had attended mainstream school. At first Esther did not know how to include Efita in the classroom activities. She was sure that Efita would not benefit from her class. Efita, who had never been to school before, showed signs of being afraid and disinterested in school and was constantly isolated from others.

However, after the teacher training, Esther is now better equipped to deliver lessons in an inclusive manner. She is now confident that Efita will be learning well with others. She has started implementing some of the inclusive approaches that she learned, including arranging the classroom into groups so that children learn from each other. She’s also been using different chalk colours to write on the board to help accommodate other learners with visual impairments. Her method of delivering lessons is no longer her original lecture style but is now more learner focused. She allows for more discussion and uses learning aids such as diagrams as a way of simplifying content.

The changes in teaching approach have helped improve Efita’s performance in class. He now mingles with his classmates and has made many friends. At the moment he enjoys basic tracing activities and playing a role in classroom exercises. He also enjoys being clapped by other children when he answers questions correctly in class. As a result, his confidence and interest in school have increased a lot.

These milestones made with Efita have convinced Esther that inclusive education works. She says: “I now know that children with impairments are like other children, they have the right to education and have the ability to learn like other children”.

Over the next 3 years, Leonard Cheshire expects to enrol 750 children with disabilities in five districts in the Eastern Province of Zambia. In the first year, 421 children have been enrolled.

Using technology to create positive learning environments

Pauline Okach is a teacher at Nyasare Primary School in Migori County Kenya. She is one of 75 teachers who have been taking part in a training programme for the Orbit Reader 20, an assistive technology device that helps people with visual impairments read in braille, as well as take braille notes. The programme is part of Leonard Cheshire’s innovation initiative to expand the use of innovative low-cost assistive technology to learners with disabilities living in rural and under resourced areas.

The portable devices are light weight and operate in two main modes. The stand-alone mode has the capabilities of reading, writing and file management for books that have been translated into electronic braille. The remote mode allows the reader to be connected to a computer with a screen reader, with a removable memory card and Bluetooth connectivity. The devices allow children to read and write in braille, with notes that can then be converted back to electronic print for the teacher to read and grade accordingly.

As part of Leonard Cheshire’s Girls’ Education Challenge Transition project, a number of training modules have been developed so that teachers can help their students get the most out of the technology. While the Covid-19 pandemic affected schools around the world, teachers were still able to take part in the Orbit Reader 20 training, ensuring they were ready to support students on their return to school. The training was conducted by Leonard Cheshire staff in partnership with eKitabu, who developed the online training tutorials. The tutorials were then shared via Whatsapp, where the teachers were able to interact with and support each other.

To ensure progress was being made, individual follow up calls were made to the teachers following each tutorial, with ongoing support being provided by the instructors. An end-of-training assessment was also carried out to identify any knowledge gaps and ensure the teachers had access to further support if they needed it.

Pauline works in an integrated mainstream school which accommodates students with and without disabilities. A number of her students have visual impairments, including ten-year-old Marydith. Pauline already had good knowledge of the importance of inclusive education, taking part in training a few years ago in order to learn how best to support students with a range of disabilities and needs. Originally, she said her attitude towards disability was negative, but it is much more positive now she has had access to training. Following the recent Orbit Reader training, Pauline has been supporting Marydith to use the technology in class. With the use of the devices, Marydith has been using the Orbit Reader to learn the letters of the alphabet in braille. She can also use it to type and delete notes, helping her engage in class.

There have been a number of other adjustments made at the school to ensure Marydith is fully included. This includes clear, level pathways to help her move more freely around the school and highlighted doorways and steps with yellow or white paint making them more obvious to assist her. There is also an adapted timetable that ensures Marydith gets the learning support she needs, with extra time during lessons to help her use the Orbit Reader. In addition, she is a member of the school’s child to child club, where she gets to interact with her peers and demonstrate the value of inclusion.

Pauline believes that these universal design measures, as well as the introduction of assistive technology, has helped improve inclusion in the school and changed the attitudes of other students. Before, there was a lot of stigma around disability and other students felt nervous to be around children with visual impairments. Now, they have much more awareness and appreciation for disability. They accommodate Marydith and help her move around the school between classes. This has created a positive atmosphere at the school, reducing bullying and creating a productive learning environment for the students. The Orbit Readers have also greatly improved Marydith’s learning progress. She can now read and write without straining her eyes, allowing her to succeed in class and stay on the same level as her classmates.

Without assistive devices like the Orbit Readers, children with severe visual impairments would not have the same opportunities for education and may even feel discouraged to attend school. Pauline hopes that more teachers can get access to training on the technology so that even more students can benefit from these and other devices.

The power of data in advocacy

Youth advocate Ian Banda tells us how data can help him make changes in Zambia.

There is so much power in data. Data – like personal stories and facts and figures – is so important in getting a strong message across. In fact, it was central to my role as lead citizen reporter on Leonard Cheshire’s 2030 and Counting project.

The community citizen reporters and I went out and gathered community insights with our phones. We would then submit the content to a central reporting hub. The aim was to find data and stories about the barriers, challenges and opportunities for youth with disabilities in Zambia. Specifically, in relation to health, education and employment. This data is so important in tracking progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). And making sure disabled people are included in this progress too! Because there is no single SDG that covers just disability, but the 17 SDGs can only be achieved if people with disabilities have their rights fulfilled.

I found Rebecca’s story on education during a data collection trip in the local community. I was touched by how much Rebecca valued education. She knew it could improve her life. She has really big dreams for our country and access to education is an important part of that. I feel personal stories are important for advocacy. They show the impact on a personal, individual level. And they show what is transpiring on the ground with regards to disability inclusion. Stories also help provide a clear picture when providing evidence-based advocacy. This is essential if you want to bring about change at a higher level.

After 2030 and Counting I set up Youth in Action for Disability Inclusion of Zambia (YADIZ). We are a youth-led disability inclusion organisation. We promote the inclusion of youth with disabilities in all aspects of life. I know the information available on Leonard Cheshire’s Disability Data Portal will really help us with our work.

The portal gives us access to evidence for our advocacy work. Valuable data on the portal from census' shows that Zambian policies and practices have gaps when it comes to disability. These figures can go a long way in highlighting concerns and irregularities in the way the government implements policy. Especially in areas like education and employment. These gaps need to be filled in order for disability inclusion to be a reality in Zambia. No one should be left behind and we are the best placed to bring that message to governments.

As the portal continues to expand we will also be able to see how we compare with other countries and assess gaps in other areas. From work in the community we know there are issues when it comes to inaccessible sexual reproductive health for people with disabilities. As well as negative attitudes displayed by health personnel. There’s also a lack of information in accessible formats. And despite Zambia having some progressive policies, there is no implementation, monitoring and evaluation framework to really track progress. That was also a recurring issue many people with disabilities experienced across the world. The simple lack of accessible information about Covid-19 put us at a disadvantage. Access to better quality data, like the portal, can help us highlight these issues.

When it comes to advocacy, it’s essential everyone has access to research. That way we can improve public knowledge and awareness of the rights of people with disabilities. Data and stories are two sides of the same coin. By combining the two, we can influence laws and policies so that they are inclusive.

- Find out more about Ian’s fight for equality in Zambia

Universal design at Mcini Primary School

Leonard Cheshire and Cheshire Homes Society in Zambia have been working together to make vital school adaptations at Mcini Primary School in Zambia. Now the school is much more accessible for children with disabilities.

Other recent news

School Inclusion in Lebanon pp 47–65 Cite as

Historical and Theoretical Approaches to Inclusive Education

- Anies Al-Hroub 3 &

- Nidal Jouni 3

- First Online: 16 November 2023

119 Accesses

This chapter provides an overview of the historical and theoretical underpinnings of student inclusion in education. It investigates how the notion of inclusion has evolved and its relationship with social justice and equity in education. Additionally, the chapter examines how inclusion is a transformational approach that meets the diverse expectations and needs of all learners and compares different inclusive models across countries. Furthermore, the chapter explores the theoretical foundations of inclusion based on an understanding of the ecological context and sociocultural dimensions of children’s learning. It highlights the link between students’ learning and the application of sociocultural instructional approaches that promote student social interaction and engagement with the learning environment.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Ainscow, M. (2005). Looking to the future: Towards a common sense of purpose. The Australasian Journal of Special Education, 29 (2), 182–186. https://doi.org/10.2260/1030-0112.29.2.0268

Article Google Scholar

Al-Hroub, A. (2009a). Dynamic assessment applied to preschool children with learning difficulties. La Nouvelle revue de l’adaptationet de la scolarisation, 46 , 69–76. https://doi.org/10.3917/nras.046.0069

Al-Hroub, A. (2009b). Évaluation dynamique appliquée aux préscolaires présentant des difficulties d'apprentissage. La Nouvelle revue de l’adaptationet de la scolarisation, 46 , 61–68. https://doi.org/10.3917/nras.046.0061

Al-Hroub, A. (2011). Developing assessment profiles for mathematically gifted children with learning difficulties in England. Journal of Education for the Gifted, 34 (1), 7–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/016235321003400102

Al-Hroub, A. (2012). Theoretical issues surrounding the concept of gifted with learning difficulties. International Journal for Research in Education, 31 , 30–60. http://www.cedu.uaeu.ac.ae/journal/issue31/ch2_31ar.pdf

Google Scholar

Al-Hroub, A. (2013). A multidimensional model for the identification of dual-exceptional learners. Gifted and Talented International, 28 , 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332276.2013.11678403

Al-Hroub, A. (2014). Perspectives of school dropouts’ dilemma in Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon: An ethnographic study. International Journal of Educational Development, 35 , 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2013.04.004

Al-Hroub, A. (2021). The utility of psychometric and dynamic assessments for identifying cognitive characteristics of twice-exceptional students exhibiting mathematical giftedness and learning disabilities. Frontiers in Psychology, 12 , 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.747872

Al-Hroub, A., & Whitebread, D. (2019). Dynamic assessment for identification of twice-exceptional learners exhibiting mathematical giftedness and specific learning disabilities. Roeper Review, 41 (2), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783193.2019.1585396

Al-Hroub, A., Saab, C., & Vlaardingerbroek, B. (2020). Addressing the educational needs of street children in Lebanon: A hotchpotch of policy and practice. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34 (3), 3184–3196. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa091

Alkhateeb, J. M., Hadidi, M. S., & Alkhateeb, A. J. (2016). Inclusion of children with developmental disabilities in Arab countries: A review of the research literature from 1990 to 2014. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 49–50 , 60–75.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Artiles, A. J., & Kozleski, Ε. B. (2007). Beyond convictions: Interrogating culture, history, and power in inclusive education. Journal of Language Arts, 84 (4), 351–358.

Artiles, A.J., Kozleski, E. B., & Waitoller, F. (Eds.). (2011). Inclusive education: Examining equity on five continents. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Bassot, B. (2012). Upholding equality and social justice: A social constructivist perspective on emancipatory career guidance practice. Australian Journal of Career Development, 21 (2), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/103841621202100202

Black-Hawkins, K. (2010). Educational meanings, consequences and control. Cambridge Journal of Education, 40 (2), 93–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2010.486229

Booth, T., & Ainscow, M. (2002). Index for inclusion: Developing learning and participation in schools . Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education.

Booth, T., & Ainscow, M. (2005). From them to us: An international study of inclusion in education . Routledge Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203982884

Book Google Scholar

Booth, T., Ainscow, M., & Kingston, D. (2006). Index for inclusion: Developing play, learning and participation in early years and childcare . Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education.

Budd, J. (2016). Using meta-perspectives to improve equity and inclusion. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 51 (2), 227–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-016-0060-1

Capper, C. A., Frattura, E. M., & Keyes, M. W. (2000). Meeting the needs of students of all abilities: How leaders go beyond inclusion . Corwin Press.

Cline, T., & Frederickson, N. (2014). Models of service delivery and forms of provision. In L. Florian (Ed.), The Sage handbook of special education (pp. 39–54). SAGE.

Chapter Google Scholar

Connor, D. J. (2014). Social justice in education for students with disabilities. In L. Florian (Ed.), The Sage handbook of special education (pp. 111–128). SAGE.

Daniels, H. (2008). Vygotsky and research . Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203891797

Dewey, J. (1915). The school and society . University of Chicago Press.

Education Bureau. (2008). Catering for student differences. Indicators for Inclusion: A tool for school self-evaluation and school development . Hong Kong SAR: Education Bureau.

Felder, F. (2018). The value of inclusion. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 52 (1), 54–70.

Feuerstein, R. (1980). Instrumental enrichment: An intervention program for cognitive modifiability . University Park Press.

Florian, L. (2008). Special or inclusive education: Future trends. British Journal of Special Education, 35 (4), 202–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8578.2008.00402.x

Florian, L. (2014). Reimagining special education. In L. Florian (Ed.), The Sage handbook of special education (pp. 9–22). SAGE.

Fraser, Ν. (1997). Justice interruptus: Critical reflections on the postsocialist condition . Routledge.

Fraser, Ν. (2008). Scales of justice: Reimagining political space in a globalizing world. Polity.

Gaad, E. (2011). Inclusive education in the Middle East . Routledge.

Gallagher, D. J., Connor, D. J., & Ferri, B. A. (2014). Beyond the far too incessant schism: Special education and the social model of disability. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 18 , 1120–1142.

Gindis, B. (1999). Vygotsky's vision: Reshaping the practice of special education for the 21st century. Remedial and Special Education, 20 (6), 333–340.

Hallahan, D. P., Kauffman, J. M., & Pullen, P. C. (2023). Exceptional learners: An introduction to special education (15th ed.). Pearson.

Harry, B., & Klingner, J. (2014). Why are so many minority students in special education? Teachers College Press.

Hawkins, R. C. (2011). The impact of inclusion on the achievement of middle school students with mild to moderate learning disabilities performance in middle school. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, Walden University.

Holton, D., & Clarke, D., (2006) Scaffolding and metacognition. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 37:2, 127-143, DOI: 10.1080/00207390500285818.

Idol, L. (2006). Toward inclusion of special education students in general education: A program evaluation of eight schools. Remedial and Special Education, 27 (2), 77–94.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, (IDEA). (2004). 20 U.S.C. 1401(3) (A). Retrieved from:https://sites.ed.gov/idea/statute-chapter-33/subchapter-i/1401/3

Kauffman, J. M., & Hallahan, D. P. (2005). Special education: What it is and why we need it . Pearson Allyn & Bacon.

Kavelashvili, N. (2017). Inclusive education in Georgia: Current progress and challenges. Izzivi Prihodnosti, 2 (2), 89–101.

Kearney, A. (2009). Barriers to school inclusion: An investigation into the exclusion of disabled students from and within New Zealand Schools . Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand.

Kilinc, S. (2019). ‘Who will fit in with whom?’ Inclusive education struggles for students with dis/abilities. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23 , 1296–1314.

Kyriazopoulou, M., & Weber, H. (Eds.). (2009). Development of a set of indicators for inclusive education in Europe . European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mallory, B. L., & New, R. S. (1994). Social constructivist theory and principles of inclusion: Challenges for early childhood special education. The Journal of Special Education, 28 (3), 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/002246699402800307

McCullough, J. L. (2008). A study of special education programming and its relationship . University of Delaware, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 3325487.

Meijer, A. M., & Van den Wittenboer, G. L. H. (2004). The joint contribution of sleep, intelligence and motivation to school performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 37 , 95–106.

Mittler, P. J. (2000). Working towards inclusive education: Social contexts . David Fulton Publishers.

Nieto, S., & Bode, P. (2007). Affirming diversity: The sociopolitical context of multicultural education (5th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Norwich, B. (2014). Categories of special educational needs. In L. Florian (Ed.), The Sage handbook of special education (pp. 55–72). SAGE.

Nusbaum, E. A. (2013). Vulnerable to exclusion: The place for segregated education within conceptions of inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 17 , 1295–1311.

Opertti, R., Walker, Z., & Zhang, Y. (2014). Inclusive education: From targeting groups and schools to achieving quality education as the core of EFA. In L. Florian (Ed.), The Sage handbook of special education (pp. 149–170). SAGE.

Polat, F. (2011). Inclusion in education: A step towards social justice. International Journal of Educational Development, 31 (1), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2010.06.009

Poon-McBrayer, K. F. (2014). The evolution from integration to inclusion: The Hong Kong tale. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 18 (10), 1004–1013.

Ratner, C. (1991). Vygotsky’s sociohistorical psychology and its contemporary applications . Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2614-2

Rieber, R. W., & Robinson, D. K. (2004). The essential vygotsky . Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-30600-1

Rioux, M. (2014). Disability rights in education. In L. Florian (Ed.), The Sage handbook of special education (pp. 132–148). SAGE.

Rix, J. (2011). Repositioning of special schools within a specialist, personalised educational marketplace – The need for a representative principle. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15 (2), 263–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110902795476

Ruijs, N. M., & Peetsma, T. D. (2009). Effects of inclusion on students with and without special educational needs reviewed. Educational Research Review, 4 , 67–79.

Ryan, J. (2006). Inclusive leadership and social justice for schools. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 5 (1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700760500483995

Sampaio, M., & Leite, C. (2018). Mapping social justice perspectives and their relationship with curricular and schools' evaluation practices: Looking at scientific publications. Education as Change, 22 (1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.25159/1947-9417/2146

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (2003). Knowledge building environments: Extending the limits of the possible in education and knowledge work. In A. DiStefano, K. E. Rudestam, & R. Silverman (Eds.), Encyclopedia of distributed learning (pp. 269–272). Sage.

Shaeffer, S. (2015). Equity in education: An imperative for the post-2015 development agenda . Asian Education Futures, Workshop Report, 1 . Singapore: The Head Foundation. Retrieved from: http://www.headfoundation.org/reports/Workshop_Paper_No_1_For_web_v2.pdf

Shaeffer, S. (2019). Inclusive education: A prerequisite for equity and social justice. Asia Pacific Education Review, 20 (2), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-019-09598-w

Stacy, C., Meixell, B., & Sirini, T. (2019). Inequality versus inclusion in US cities. Social Indicators Research, 145, 117–156. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02090-3

Sternberg, R. J., & Williams, W. M. (2010). Educational psychology (2nd ed.).

Terzi, L. (2010). Introduction. In M. Warnock, B. Norwich, & L. Terzi (Eds.), Special educational needs: A new look . Continuum.

Tharp, R. (1997). From at-risk to excellence: Research, theory, and principles for practice.

Theoharis, G., & Causton, J. (2014). Leading inclusive reform for students with disabilities: A school- and systemwide approach. Theory Into Practice, 53 (2), 82–97. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43893918

Thomas, G. (2013). A review of thinking and research about inclusive education policy, with suggestions for a new kind of inclusive thinking. British Educational Research Journal, 39 (3), 473–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2011.652070

UNESCO. (1994). The Salamanca Statement and framework for action on special needs education. Adopted by the world conference on special needs education: Access and quality. UNESCO.

UNESCO. (2009). Policy guidelines on inclusion in education . The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000098427

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2000). The Dakar framework for action. UNESCO. Retrieved from: https://www.right-to-education.org/sites/right-to-education.org/files/resourceattachments/Dakar_Framework_for_Action_2000_en.pdf

United Nations. (2007). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). UN. https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-crpd

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2010). Education for All (EFA): Towards Inclusion. UNESCO. Retrieved from: https://www.unesco.org/gem-report/en/efa-achievements-challenges

Valenzuela, J. S. (2014). Sociocultural views of learning. In L. Florian (Ed.), The Sage handbook of special education (pp. 299–314). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446282236

Vaughan, M. (2000). Index for inclusion: Developing learning and participation in schools . Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1934/1986) Thought and language . Sage/MIT Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1962). Thought and language . (E.Hanfmann & G. vakar, Trans.). MIT Press.

Waitoller, F. R., & Annamma, S. A. (2017). Taking a spatial turn in inclusive education: Seeking justice at the intersections of multiple markers of difference. In M. T. Hughes & E. Talbott (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of research on diversity in special education . Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118768778.ch2

Warnock, M. (2005). Special educational needs: A new look . Impact paper No 11. Philosophy of Education Society of Great Britain.

Warnock, M., & Norwich, B. (2010). Special educational needs: A new look . Bloomsbury Publishing.

Winzer, M. A. (2014). Confronting difference: A brief history of special education. In L. Florian (Ed.), The Sage handbook of special education (pp. 23–38). SAGE.

Zambo, D. (2009). Gifted students in the 21 st century: Using Vygotsky’s theory to meet their literacy and content area needs. Gifted Education International, 25 (3), 270–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/026142940902500308

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Education, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon

Anies Al-Hroub & Nidal Jouni

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Anies Al-Hroub .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Al-Hroub, A., Jouni, N. (2023). Historical and Theoretical Approaches to Inclusive Education. In: School Inclusion in Lebanon. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34779-5_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34779-5_4

Published : 16 November 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-34778-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-34779-5

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Privacy Policy & Terms of Use

Copyright © INEE 2024

Inclusive Education: What, Why, and How: A handbook for program implementers

Inclusive education is one dimension of a rights-based quality education which emphasizes equity in access and participation, and responds positively to the individual learning needs and competencies of all children. Inclusive education is child-centered and places the responsibility of adaptation on the education system rather than the individual child.

This handbook has been developed specifically for Save the Children program staff, implementing partners, and practitioners supporting education programs in any context – development, emergency, or protracted crisis. Although not all education projects have the word “inclusive” in the title or goals, every education project can and should be made more inclusive, and we encourage this resource to be used by all education staff, not only those working on targeted inclusive education projects.

A document review conducted by the Inclusive Education Working Group (IEWG) in 2013 found that despite a large number of resources available on inclusion, most have not led to universal understanding and uptake of inclusive education. Many inclusive education manuals are very long, and are not easily accessible to busy project managers. The majority of documents also targeted a wide audience, and in doing so, limited their utility to any specific group. The IEWG recognizes that inclusive education begins with the work being done by education staff in the field, and have therefore designed this handbook specifically with them in mind. Guidance has also been structured along the project cycle, so that it may be useful to programs regardless of their current stage of implementation.

Resource Info

Resource type, published by.

This site belongs to UNESCO's International Institute for Educational Planning

IIEP Learning Portal

Search form

- issue briefs

- Improve learning

Disability inclusive education and learning

Inscribed in the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (1948) , education is a basic right. A range of declarations and conventions highlight the importance of education for people with disabilities: the Salamanca Statement on education and special needs in 1994, as well as article 24 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) adopted in 2006. The importance of education for all is also included in the Convention against Discrimination in Education 1960. In 2015, the Incheon Declaration recalled the importance of inclusive education for all. Targets 4.5 and 4.a call for access to education and the construction of adapted facilities for children with disabilities (Education 2030, 2016).

WHAT WE KNOW

There are few data on school enrolment figures for children with disabilities. However, we do know that there are between 93 and 150 million children living with a disability and, according to the Learning Generation report, in low- and middle-income countries as many as 33 million children with disabilities are out of school (Grant Lewis, 2019). Moreover, children with disabilities are less likely to complete primary, secondary and further education compared to children without disabilities.

In all countries of the world, people with disabilities have lower literacy rates than people without disabilities (Singal, 2015; UIS, 2018; United Nations, 2018). There is also a difference based on the nature of the disability i.e. illiteracy is higher in children with visual impairments, multiple or mental disorders compared to children with motor disabilities (Singal, 2015).

When they do attend school, children with disabilities score lower in mathematics and reading tests, as shown in the PASEC learning assessments (World Bank, 2019; Wodon et al, 2018). Girls with disabilities are penalized even further due to their gender (UIS, 2018). Generally, disability tends to compound social inequalities (e.g. poverty or place of residence). That said, in Pakistan, the learning gap between children with disabilities and children without disabilities enrolled in school was lower than the gap between these two out-of-school groups (Rose et al., 2018: 9). Moreover, studies in the United States of America have shown that students with disabilities achieve better academic outcomes and social integration when studying in a mainstream environment than students studying in segregated or specialized classes (Alquraini and Gut, 2012).

TOWARD A MAINSTREAM SCHOOL ENVIRONMENT

Inclusive education means including students with disabilities in a mainstream school environment. In many countries today, children with disabilities attend ordinary schools but follow a specific curriculum. Moving toward a more inclusive model (i.e. students with disabilities follow an inclusive curriculum along with able-bodied students) is a long-term process.

As countries move toward more inclusive education, special schools and their staff can play a key role by acting as specialized experts and helping mainstream schools achieve greater inclusion (UNESCO, 2017). The Global Partnership for Education (GPE) studied the inclusion of students with disabilities in education sector plans in 51 countries. Seventeen of them are considering a two-pronged approach: to integrate disability in education and to invest in actions and services aimed specifically at meeting the needs of children with disabilities (GPE, 2018).

Many obstacles prevent children and young people with disabilities from attending a mainstream school.

- Identifying pupils with disabilities . Prejudices and social attitudes lead to under-declaring the number of children with disabilities (GPE, 2018). Certain families, fearing stigmatisation, do not send their children to school (Singal, 2015; EDT and UNICEF, 2016). Due to the hidden nature of certain learning difficulties, the total population of these children is largely unknown (World Bank, 2019). Identifying these children at school is rare (Wodon et al, 2018). Recognizing disabilities may be limited to observable disabilities and not necessarily those that affect the child's ability to learn (EDT and UNICEF, 2016). Obsolete and inadequate data complicate effective educational planning and hinder decision-making and resource allocation (GPE, 2018). In addition, countries use different measurements, methods and definitions to classify disabilities thus affecting their ability to compare data (GPE, 2018; Price, 2018).

- Lack of trained teachers. In many countries, teachers do not have the confidence or the necessary skills to deliver inclusive education (Singal, 2015; Wodon et al, 2018). Inclusive education is only a small component of the training received by teachers and is not always assessed (EDT and UNICEF, 2016).

- Poorly adapted school facilities and learning materials. Poorly adapted infrastructures and a lack of accessible learning materials are significant obstacles. This is particularly true in rural areas where increased levels of poverty, poor services, and recurrent infrastructure failings exacerbate these existing problems for children with disabilities (SADPD, 2012). School curricula that solely rely on passive learning methods, such as drilling, dictation, and copying from the blackboard, further limit access to quality education for children with disabilities (Humanity & Inclusion, 2015).

- Lack of resources. Whether it concerns building adapted schools, reducing class sizes or teacher training, financial and human resources are required (Grimes, Stevens and Kumar, 2015). Funds earmarked for special needs are often insufficient. Where funding is available, it is primarily intended for schools and special units, rather than being used for the needs of students enrolled in mainstream schools and removing existing barriers (Mariga, McConkey and Myezwa, 2014).

- Assessing learning. There are few data on the learning outcomes of students with disabilities. Examinations and tests rarely make accommodations for these students putting them at a disadvantage. Most international performance tests exclude students with disabilities, which, in turn, reinforces low expectations (Schuelka, 2013 cited in Price, 2018; World Bank, 2019).

POLICY AND PLANNING

- Defining a policy for inclusive education. Inclusive education requires a systemic examination of education systems and school cultures. Promoting social justice and inclusive education requires drawing up, implementing and assessing plans and policies that favour inclusive education for all. Every country needs to formulate its own set of solutions that reach down to the level of individual schools (Grant Lewis, 2019).

- Facilitating access to learning. The first step to including children with disabilities in mainstream schools is the provision of adapted school facilities e.g. ramps, toilets, special equipment, and apparatus, as well as making appropriate teaching and learning materials available (SADPD, 2012; Malik et al., 2018). To encourage the enrolment of girls with disabilities, special measures could comprise grants or allowances (GPE, 2018).

- Strengthening partnerships. Inclusive education requires creating partnerships with local stakeholders i.e. parents, schools, communities, countries, ministries, and development partners (Grant Lewis, 2019). Partnerships which capitalize on local knowledge and resources have proven to be effective (SADPD, 2012; EDT and UNICEF, 2016; GPE, 2018). One recommendation is to give particular support to parents to raise their awareness of the importance of inclusive education and to integrate them into the educational community, for example by participating in school activities (GPE, 2018).

- Ensuring adequate teacher training. The ability of teachers to provide quality education to students with disabilities depends on their training and qualifications (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2015). However, teachers often struggle due to already overcrowded classes. Offering upstream pre-service training for future teachers, investing in in-service teacher training comprising practical stages and a mentoring system are approaches that have proved their effectiveness (Ackers, 2018). However, it is important to train specialized teachers as it is not possible to train all mainstream teachers to be sufficiently fluent in Braille, national sign language, and augmentative and alternative communication modes (EDT and UNICEF, 2016). The Global Partnership for Education has also highlighted the importance of training teachers to identify disabilities (GPE, 2018).

- Statistics to reinforce human support. Although data are rare, there are tools which can be used to monitor the participation and learning of students with disabilities. Data from household surveys are used to monitor school attendance and success rates for children, as well as to examine factors linked to non-attendance; Education Management Information Systems (EMIS) collect administrative data about school attendance, student behaviour, and progress. However, qualitative data are also needed to shed light on the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of the lives of students, teachers, and parents (Mont, 2018). Equally important is the collection of data on the school environment, such as the physical accessibility of schools, information on policies and legislation, teaching materials, teacher training and the availability of support specialists in schools (Grant Lewis, 2018).

- Assessing students. The Salamanca Statement advocates formative assessment to identify difficulties and help students overcome them (Salamanca Statement, 1994). Sæbønes et al. (2015) recommend classroom assessments for individual learning. They recommend that regional and national examinations and international learning assessments systematically include all students and provide reasonable accommodations for learners with disabilities. A study conducted in Kenya shows that it is possible to carry out large-scale learning assessments of deaf and blind children. However, in order to design these adapted tools, human, material and financial resources are necessary (Piper et al., 2019). For an overview of the issue of learning assessments and students with disabilities see World Bank, 2019.

- Investing in technology. According to UNESCO “ICTs can be a valuable tool for learners with disabilities who are vulnerable to the digital divide and exclusion from educational opportunities” (UNESCO, 2014: 10). To reduce barriers, their model policy recommends the use of inclusive ICTs, commercially available products that are, as far as possible, accessible to all, as well as assistive technology to enable access when this is not possible using products available on the market. (UNESCO, 2014: 11).

- Cost. It is important to find ways to meet the needs of the most marginalized without additional funding (UNESCO, 2017). Approaches, such as analysing data from household surveys, suggest that the returns on investing in education for children with disabilities are high and similar to those for people without disabilities. Therefore, investing in the education of children with disabilities is both smart and profitable (Wodon et al., 2018). UNESCO recommends setting up or strengthening financial monitoring systems, as well as creating partnerships between governments and donors (UNESCO, 2017). Finally, the comparison between the cost of specialized institutions and inclusive institutions reveals that the inclusive system is more efficient (Open Society Foundations, n.d.; Inclusion International. n.d.).

- Proposing inclusive pedagogy. The type of disability (autism spectrum disorders, learning disabilities, language, hearing, etc.) influences the learning method. Inclusive pedagogy requires a shift in the educational culture within teaching and support practices i.e. moving away from ‘one-size-fits-all’ education towards a tailored approach to increase the capacity of the system to meet the diverse needs of learners without the need to categorize or label them (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2017). We move away from the idea of inclusion as a specialized response to certain learners, to allow them to access or participate in what is offered to most students (Florian, 2015). Inclusive pedagogy implies having resources and services that can be used by all students without the need for adaptation or specialized planning (UNESCO, 2017: 19).

Plans and policies

- Fiji: Policy on special and inclusive education (2016)

- Kenya: Sector policy for learners and trainees with disabilities (2018)

- South Africa: Policy on screening, identification, assessment, and support (2014)

- Fiji. Ministry of Education; Australian Agency for International Development. 2017. Fiji Education Management Information System (FEMIS): Disability disaggregation package. Guidelines and forms.

- Bulat, J.; Macon, W.; Ticha, R.; Abery, B. 2017. School and classroom disabilities inclusion guide for low- and middle-income countries. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI Press.

- Ethiopia. Ministry of Education. 2015. Guideline for establishing and managing inclusive education resource/support centers (RCs). Addis Ababa: Federal Ministry of Education.

- Hayes, A. M.; Bulat, J. 2017. Disabilities inclusive education systems and policies guide for low- and middle-income countries . Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI Press.

- UNESCO. 2017. A Guide for ensuring inclusion and equity in education. Paris: UNESCO.

Ackers, J. 2018. “Teacher education and inclusive education”. The IIEP Letter 34 (2)

Alquraini, T.; Gut, D. 2012. Critical components of successful inclusion of students with severe disabilities: International Journal of Special Education 27 (1): 42 59.

Convention against discrimination in education.

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4: To ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning . 2016.

Education Development Trust; UNICEF. 2016. Eastern and Southern Africa regional study on the fulfilment of the right to education of children with disabilities. Reading: EDT.

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education. 2015. Empowering teachers to promote inclusive education: A case study of approaches to training and support for inclusive teacher practice. Odense: European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education.

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education. 2017. Inclusive education for learners with disabilities. Study for the Peti committee. Brussels: European Union.

Florian, L. 2015. Inclusive Pedagogy: A transformative approach to individual differences but can it help reduce educational inequalities? Scottish Educational Review 47 (1): 5 14.

Grant Lewis, S. 2019. ' Opinion: The urgent need to plan for disability-inclusive education'. Devex. 6 February 2019.

Grimes, P.; Stevens, M.; Kumar, K. 2015. 'An examination of the evolution of policies and strategies to improve access to education for children with disabilities with a focus on inclusive education approaches, the success and challenges'. Background paper prepared for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2015, Education for All 2000-2015: Achievements and challenges.

Humanity & Inclusion. 2015. Education for all? This is still not a reality for most children with disabilities.

Inclusion International. n.d. FAQs - Inclusion International .

Male, C.; Wodon, Q. 2018. Disability gaps in educational attainment and literacy. The price of exclusion: disability and education. Washington, DC: World Bank; GPE.

Mariga, L.; McConkey, R.; Myezwa, H. 2014. Inclusive education in low-income countries: A resource for teacher educators, parent trainers and community development workers . Cape Town: Atlas Alliance and Disability Innovations Africa.

Mont, D. 2018. Collecting data for inclusive education . IIEP Learning Portal (blog).

Open Society Foundations. n. d. ' The power of letting children learn together'.

Global Partnership for Education (GPE). 2018. Disability and inclusive education - a stocktake of education sector plans and GPE-funded grants. Washington, DC: GPE.

Piper, B.; Bulat, J.; Kwayumba, D.; Oketch, J.; Gangla, L. 2019. Measuring literacy outcomes for the blind and for the deaf: Nationally representative results from Kenya. International Journal of Educational Development 69 (September)

Price, R. 2018. Inclusive and special education approaches in developing countries. K4D Helpdesk Report.

Rose, P.; Singal, N.; Bari, F.; Malik, R.; Kamran, S. 2018. Identifying disability in household surveys: evidence on education access and learning for children with disabilities in Pakistan. Policy Paper, 18/1. Cambridge: REAL Centre. University of Cambridge.

Sæbønes, A.-M.; Berman Bieler, R.; Baboo, N.; Banham, L.; Singal, N.; Howgego, C.; Vuyiswa McClain-Nhlapo, C.; Riis-Hansen, T. C.; Dansie, G. A. ' Towards a disability inclusive education '. Background paper for the Oslo Summit on Education for Development, 6-7 July 2015.

Salamanca Statement and the Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. 1994.

Secretariat of the African Decade of Persons with Disabilities. 2012. Study on education for children with disabilities in Southern Africa. Pretoria: SADPD.

Singal, N. 2015. Education of children with disabilities in India and Pakistan: an analysis of developments since 2000. Background paper prepared for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2015, Education for All 2000-2015: Achievements and challenges.

UIS. 2018. Education and disability: analysis of data from 49 countries. Information Paper 49. Montreal: UIS.

UNESCO. 2014. Model policy for inclusive ICTs in education for persons with disabilities. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO. 2017. A Guide for ensuring inclusion and equity in education . Paris: UNESCO.

United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2018. ' Realization of the Sustainable Development Goals by, for and with persons with disabilities'. UN Flagship Report on Disability and Development 2018. Advanced unedited version. New York: United Nations.

Universal Declaration on Human Rights . 1948

Wodon, Q.; Male, C.; Montenegro, C.; Nayihouba, A. 2018. The challenge of inclusive education in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. 2019. Every learner matters: Unpacking the learning crisis for children with disabilities . Washington, DC: World Bank.

Related information

- Global education monitoring report, 2020: Inclusion and education: all means all

- IIEP, planning for inclusive education

- UNESCO: Inclusion in education

- Inclusive education

Accessibility Panel

- Increase Text

- Decrease Text

- High Contrast

- Reading Line

- Transparency

2023 GEM Report: How can technology support inclusive education?

- Inclusive Education

On the launch of UNESCO’s 2023 Global Education Monitoring report, Nafisa Baboo, Light for the World’s expert on Inclusive Education, examines opportunities and challenges for learners with disabilities.

Harnessing technologies to make learning materials accessible can ensure students with disabilities are included in education — but targeted funding is essential to advance existing progress.

The 2023 GEM Report on technology and education , released July 26, explores the role of technology in the classroom and widening divisions as it rapidly evolves.

With the theme A tool on whose terms? the report analyses challenges to technology use, including access, equity and inclusion. It recognises the importance of using technology to level the playing field but also the risk of widening the gap between those with existing access to technology and those without.

When technology providers and publishers comply with global accessibility standards, more opportunities for accessible technologies will be created. Nearly nine out of 10 (87%) adults said that accessible technology devices were replacing traditional assistive tools most or all the time, the report found.

However, challenges for learners with disabilities remain. These include insufficient availability of, and access to, educational technology and a lack of specialised teacher training. The stigma of using assistive technologies, which makes disabilities more visible, was also highlighted.

Nafisa Baboo, Light for the World’s expert on Inclusive Education, was among the GEM Report’s Group of Friends, advisors who provided feedback and recommendations during the report drafting.

“Technology is an enabler and can promote access and improved learning outcomes for people with disabilities. But we must be wary of the potentially dehumanising effects of technology. It can never replace the connection that supports learning and wellbeing that comes from children being together or the mentorship of a teacher,” says Nafisa.

“I know from personal experience how technology can be a game changer for people with disabilities.

“Unfortunately, many children around the world still do not have the opportunity to read. Accessible technology opens a host of possibilities and the chance for children to gain knowledge and understand a world beyond their own.

Open-use, accessible technology can support learners with disabilities, but cannot replace the human connection that influences education and learning. Digital technologies must support and enhance teacher-led education to nurture a more inclusive educational experience.”

The GEM Report stressed educational technology needs to be widely available, to ensure it not only benefits already privileged learners.

“We must prioritise technology to support the continuation of learning in humanitarian crises and inclusion of students with disabilities,” says Nafisa.

“That includes ensuring resources like websites, documents and textbooks comply with global accessibility standards and that technology is designed to reflect the diverse needs, experiences and socio-cultural contexts of learners.

“To ensure no one is left behind, we need targeted funding for expert organisations to promote and test accessible technology. And to develop evidence on what does and doesn’t work in different settings to promote an inclusive and equitable education system for all.”

This year marks the 10 th anniversary of the Marrakesh Treaty, seeking to end a “book famine” for people unable to access standard print materials. The Treaty allows for copyright laws to be relaxed, enabling people who are blind, visually impaired or with a print disability to access more books and print materials in accessible formats.

By loading the video, you agree to YouTube’s privacy policy. Learn more

Always unblock YouTube

In sub-Saharan Africa, fewer than 1% of books are in accessible format. In Burkina Faso, most students with visual impairments lack access to textbooks, with learning materials manually produced by volunteers.

Inspired by the opportunities offered by the Treaty, Light for the World has been working to improve access to learning materials for Burkinabé students.

Working alongside partners the National Union of Burkinabe Associations for the Promotion of the Blind and Visually Impaired ( UN-ABPAM ), DAISY Consortium and Benetech , Light for the World facilitated the digitialisation of more than 300 books in French and Moore.

The project saw hundreds of students receive laptops, tablets, Orbit readers and Evo E10 Daisy recorder/players . The readers and recorder/players allow students with visual impairments to access the same textbooks as their peers in real-time. A current pilot study has provided students with disabilities with smartphones and Bluetooth keyboards.