SELECT COUNTRY

- Overview of OWIS Singapore

- Mission, Vision and Values

- Creating Global Citizens

- Parent Partnerships

- Global Schools Foundation (GSF)

- Academic & Examination Board (AEB)

- Awards & Accreditations

- Admissions Overview

- Apply Online

- Book a Tour

- Application Process

- School Fees

- Scholarship

- Admissions Events and Webinars

- Entry Requirements

- Regulations

- Learning & Curricula at OWIS

- IB Primary Years Programme (Ages 3 to 11)

- Modified Cambridge (Ages 12 to 14)

- Cambridge IGCSE (Ages 15 to 16)

- IB Diploma Programme (Ages 17 to 18)

- Chinese-English Bilingual Programme (Ages 7 to 11)

- Co-scholastic Learning Programmes

- English as an Additional Language (EAL) Programme

- After-School Programme (CCAs)

- Overview of OWIS Nanyang

- Welcome Message

- Early Childhood

- Primary School

- Secondary School

- Learning Environment

- Academic Results & University Offers

- Pastoral Care & Student Well-Being

- School Calendar

- Join Our Open House

- Overview of OWIS Suntec

- Overview of OWIS Digital Campus*

- Blogs & Insights

- School Stories

- In the Media

- E-books & Downloads

- Public vs Private School

- Relocating to Singapore

OWIS SINGAPORE

Strategies to develop problem-solving skills in students.

- November 14, 2023

Students need the freedom to brainstorm, develop solutions and make mistakes — this is truly the only way to prepare them for life outside the classroom. When students are immersed in a learning environment that only offers them step-by-step guides and encourages them to focus solely on memorisation, they are not gaining the skills necessary to help them navigate in the complex, interconnected environment of the real world.

Choosing a school that emphasises the importance of future-focussed skills will ensure your child has the abilities they need to survive and thrive anywhere in the world. What are future-focussed skills? Students who are prepared for the future need to possess highly developed communication skills, self-management skills, research skills, thinking skills, social skills and problem-solving skills. In this blog, I would like to focus on problem-solving skills.

What Are Problem-Solving Skills?

The Forage defines problem-solving skills as those that allow an individual to identify a problem, come up with solutions, analyse the options and collaborate to find the best solution for the issue.

Importance of Problem-Solving in the Classroom Setting

Learning how to solve problems effectively and positively is a crucial part of child development. When children are allowed to solve problems in a classroom setting, they can test those skills in a safe and nurturing environment. Generally, when they face age-appropriate issues, they can begin building those skills in a healthy and positive manner.

Without exposure to challenging situations and scenarios, children will not be equipped with the foundational problem-solving skills needed to tackle complex issues in the real world. Experts predict that problem-solving skills will eventually be more sought after in job applicants than hard skills related to that specific profession. Students must be given opportunities in school to resolve conflicts, address complex problems and come up with their own solutions in order to develop these skills.

Benefits of Problem-Solving Skills for Students

Learning how to solve problems offers students many advantages, such as:

Improving Academic Results

When students have a well-developed set of problem-solving skills, they are often better critical and analytical thinkers as well. They are able to effectively use these 21st-century skills when completing their coursework, allowing them to become more successful in all academic areas. By prioritising problem-solving strategies in the classroom, teachers often find that academic performance improves.

Developing Confidence

Giving students the freedom to solve problems and create their own solutions is essentially permitting them to make their own choices. This sense of independence — and the natural resilience that comes with it — allows students to become confident learners who aren’t intimidated by new or challenging situations. Ultimately, this prepares them to take on more complex challenges in the future, both on a professional and social level.

Preparing Students for Real-World Challenges

The challenges we are facing today are only growing more complex, and by the time students have graduated, they are going to be facing issues that we may not even have imagined. By arming them with real-world problem-solving experience, they will not feel intimidated or stifled by those challenges; they will be excited and ready to address them. They will know how to discuss their ideas with others, respect various perspectives and collaborate to develop a solution that best benefits everyone involved.

The Best Problem-Solving Strategies for Students

No single approach or strategy will instil a set of problem-solving skills in students. Every child is different, so educators should rely on a variety of strategies to develop this core competency in their students. It is best if these skills are developed naturally.

These are some of the best strategies to support students problem-solving skills:

Project-Based Learning

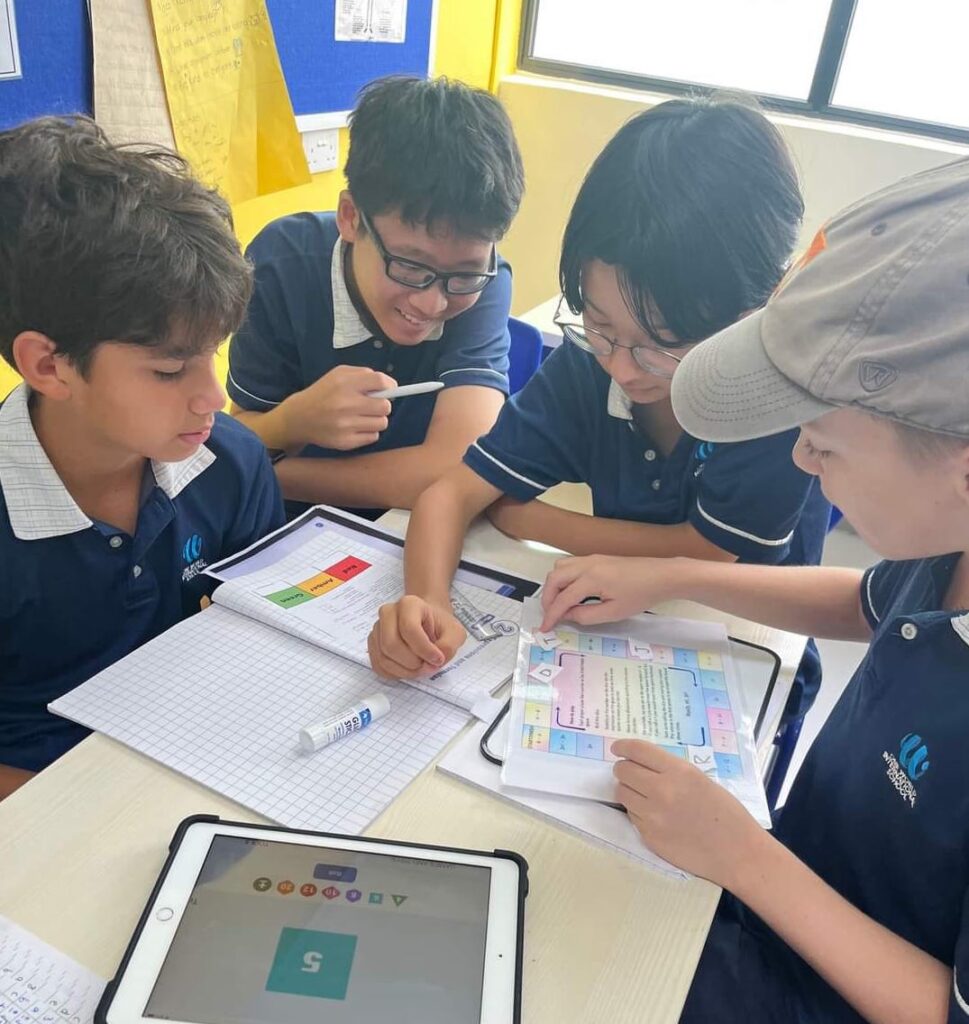

By providing students with project-based learning experiences and allowing plenty of time for discussion, educators can watch students put their problem-solving skills into action inside their classrooms. This strategy is one of the most effective ways to fine-tune problem-solving skills in students. During project-based learning, teachers may take notes on how the students approach a problem and then offer feedback to students for future development. Teachers can address their observations of interactions during project-based learning at the group level or they can work with students on an individual basis to help them become more effective problem-solvers.

Encourage Discussion and Collaboration in the Classroom Setting

Another strategy to encourage the development of problem-solving skills in students is to allow for plenty of discussion and collaboration in the classroom setting. When students interact with one another, they are naturally developing problem solving skills. Rather than the teacher delivering information and requiring the students to passively receive information, students can share thoughts and ideas with one another. Getting students to generate their own discussion and communication requires thinking skills.

Utilising an Inquiry-Based approach to Learning

Students should be presented with situations in which their curiosity is sparked and they are motivated to inquire further. Teachers should ask open-ended questions and encourage students to develop responses which require problem-solving. By providing students with complex questions for which a variety of answers may be correct, teachers get students to consider different perspectives and deal with potential disagreement, which requires problem-solving skills to resolve.

Model Appropriate Problem-Solving Skills

One of the simplest ways to instil effective problem-solving skills in students is to model appropriate and respectful strategies and behaviour when resolving a conflict or addressing an issue. Teachers can showcase their problem-solving skills by:

- Identifying a problem when they come across one for the class to see

- Brainstorming possible solutions with students

- Collaborating with students to decide on the best solution

- Testing that solution and examining the results with the students

- Adapting as necessary to improve results or achieve the desired goal

Prioritise Student Agency in Learning

Recent research shows that self-directed learning is one of the most effective ways to nurture 21st-century competency development in young learners. Learning experiences that encourage student agency often require problem-solving skills. When creativity and innovation are needed, students often encounter unexpected problems along the way that must be solved. Through self-directed learning, students experience challenges in a natural situation and can fine-tune their problem-solving skills along the way. Self-directed learning provides them with a foundation in problem-solving that they can build upon in the future, allowing them to eventually develop more advanced and impactful problem-solving skills for real life.

21st-Century Skill Development at OWIS Singapore

Problem-solving has been identified as one of the core competencies that young learners must develop to be prepared to meet the dynamic needs of a global environment. At OWIS Singapore, we have implemented an inquiry-driven, skills-based curriculum that allows students to organically develop critical future-ready skills — including problem-solving. Our hands-on approach to education enables students to collaborate, explore, innovate, face-challenges, make mistakes and adapt as necessary. As such, they learn problem-solving skills in an authentic manner.

For more information about 21st-century skill development, schedule a campus tour today.

About Author

David swanson, latest blogs.

- March 26, 2024

Beyond the Classroom: Exploring IBDP’s Impact on College and Career Readiness

- March 12, 2024

Unpacking the IB PYP: A Comprehensive Guide for Parents

- March 11, 2024

Embarking on a Journey Through the Art Spaces at OWIS Digital Campus*

- March 4, 2024

Recommended Storybooks for Preschoolers

- February 27, 2024

Transitioning From the American Curriculum to an IB School in Singapore

- February 13, 2024

Helping Teenage Students Settle Into Secondary School in Singapore

Related blog posts.

- Culture & Values

- Holistic development

- Testimonial

Fostering Confidence in Education: The Dynamic Blend of Diversity and Academic Excellence at OWIS Digital Campus*

- December 18, 2023

International Day 2020

- October 16, 2020

Sports Week 2022

- June 6, 2022

nanyang Campus

- +65 6914 6700

- [email protected]

- 21 Jurong West Street 81, Singapore 649075

- +65-83183027

Digital Campus

- #01-02, Global Campus Village, 27 Punggol Field Walk, Singapore 828649

Suntec Campus

- 1 Raffles Blvd, Singapore 039593

OWIS Nanyang is accredited for the IB PYP, Cambridge IGCSE and IB DP. OWIS Suntec is a Candidate School** for the IB PYP. This school is pursuing authorisation as an IB World School. These are schools that share a common philosophy—a commitment to high quality, challenging, international education that OWIS believes is important for our students.**Only schools authorised by the IB Organization can offer any of its four academic programmes: the Primary Years Programme (PYP), the Middle Years Programme (MYP), the Diploma Programme, or the Career-related Programme (CP). Candidate status gives no guarantee that authorisation will be granted. For further information about the IB and its programmes, visit www.ibo.org CPE Registration Number: 200800495N | Validity Period: 24 February 2023 to 23 February 2027.

Quick Links:

Virtual and in-person Campus Tours Available

Problem Solving Skills: Meaning, Examples & Techniques

Table of Contents

26 January 2021

Reading Time: 2 minutes

Do your children have trouble solving their Maths homework?

Or, do they struggle to maintain friendships at school?

If your answer is ‘Yes,’ the issue might be related to your child’s problem-solving abilities. Whether your child often forgets his/her lunch at school or is lagging in his/her class, good problem-solving skills can be a major tool to help them manage their lives better.

Children need to learn to solve problems on their own. Whether it is about dealing with academic difficulties or peer issues when children are equipped with necessary problem-solving skills they gain confidence and learn to make healthy decisions for themselves. So let us look at what is problem-solving, its benefits, and how to encourage your child to inculcate problem-solving abilities

Problem-solving skills can be defined as the ability to identify a problem, determine its cause, and figure out all possible solutions to solve the problem.

- Trigonometric Problems

What is problem-solving, then? Problem-solving is the ability to use appropriate methods to tackle unexpected challenges in an organized manner. The ability to solve problems is considered a soft skill, meaning that it’s more of a personality trait than a skill you’ve learned at school, on-the-job, or through technical training. While your natural ability to tackle problems and solve them is something you were born with or began to hone early on, it doesn’t mean that you can’t work on it. This is a skill that can be cultivated and nurtured so you can become better at dealing with problems over time.

Problem Solving Skills: Meaning, Examples & Techniques are mentioned below in the Downloadable PDF.

Benefits of learning problem-solving skills

Promotes creative thinking and thinking outside the box.

Improves decision-making abilities.

Builds solid communication skills.

Develop the ability to learn from mistakes and avoid the repetition of mistakes.

Problem Solving as an ability is a life skill desired by everyone, as it is essential to manage our day-to-day lives. Whether you are at home, school, or work, life throws us curve balls at every single step of the way. And how do we resolve those? You guessed it right – Problem Solving.

Strengthening and nurturing problem-solving skills helps children cope with challenges and obstacles as they come. They can face and resolve a wide variety of problems efficiently and effectively without having a breakdown. Nurturing good problem-solving skills develop your child’s independence, allowing them to grow into confident, responsible adults.

Children enjoy experimenting with a wide variety of situations as they develop their problem-solving skills through trial and error. A child’s action of sprinkling and pouring sand on their hands while playing in the ground, then finally mixing it all to eliminate the stickiness shows how fast their little minds work.

Sometimes children become frustrated when an idea doesn't work according to their expectations, they may even walk away from their project. They often become focused on one particular solution, which may or may not work.

However, they can be encouraged to try other methods of problem-solving when given support by an adult. The adult may give hints or ask questions in ways that help the kids to formulate their solutions.

Encouraging Problem-Solving Skills in Kids

Practice problem solving through games.

Exposing kids to various riddles, mysteries, and treasure hunts, puzzles, and games not only enhances their critical thinking but is also an excellent bonding experience to create a lifetime of memories.

Create a safe environment for brainstorming

Welcome, all the ideas your child brings up to you. Children learn how to work together to solve a problem collectively when given the freedom and flexibility to come up with their solutions. This bout of encouragement instills in them the confidence to face obstacles bravely.

Invite children to expand their Learning capabilities

Whenever children experiment with an idea or problem, they test out their solutions in different settings. They apply their teachings to new situations and effectively receive and communicate ideas. They learn the ability to think abstractly and can learn to tackle any obstacle whether it is finding solutions to a math problem or navigating social interactions.

Problem-solving is the act of finding answers and solutions to complicated problems.

Developing problem-solving skills from an early age helps kids to navigate their life problems, whether academic or social more effectively and avoid mental and emotional turmoil.

Children learn to develop a future-oriented approach and view problems as challenges that can be easily overcome by exploring solutions.

About Cuemath

Cuemath, a student-friendly mathematics and coding platform, conducts regular Online Classes for academics and skill-development, and their Mental Math App, on both iOS and Android , is a one-stop solution for kids to develop multiple skills. Understand the Cuemath Fee structure and sign up for a free trial.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How do you teach problem-solving skills.

Model a useful problem-solving method. Problem solving can be difficult and sometimes tedious. ... 1. Teach within a specific context. ... 2. Help students understand the problem. ... 3. Take enough time. ... 4. Ask questions and make suggestions. ... 5. Link errors to misconceptions.

What makes a good problem solver?

Excellent problem solvers build networks and know how to collaborate with other people and teams. They are skilled in bringing people together and sharing knowledge and information. A key skill for great problem solvers is that they are trusted by others.

Center for Teaching

Teaching problem solving.

Print Version

Tips and Techniques

Expert vs. novice problem solvers, communicate.

- Have students identify specific problems, difficulties, or confusions . Don’t waste time working through problems that students already understand.

- If students are unable to articulate their concerns, determine where they are having trouble by asking them to identify the specific concepts or principles associated with the problem.

- In a one-on-one tutoring session, ask the student to work his/her problem out loud . This slows down the thinking process, making it more accurate and allowing you to access understanding.

- When working with larger groups you can ask students to provide a written “two-column solution.” Have students write up their solution to a problem by putting all their calculations in one column and all of their reasoning (in complete sentences) in the other column. This helps them to think critically about their own problem solving and helps you to more easily identify where they may be having problems. Two-Column Solution (Math) Two-Column Solution (Physics)

Encourage Independence

- Model the problem solving process rather than just giving students the answer. As you work through the problem, consider how a novice might struggle with the concepts and make your thinking clear

- Have students work through problems on their own. Ask directing questions or give helpful suggestions, but provide only minimal assistance and only when needed to overcome obstacles.

- Don’t fear group work ! Students can frequently help each other, and talking about a problem helps them think more critically about the steps needed to solve the problem. Additionally, group work helps students realize that problems often have multiple solution strategies, some that might be more effective than others

Be sensitive

- Frequently, when working problems, students are unsure of themselves. This lack of confidence may hamper their learning. It is important to recognize this when students come to us for help, and to give each student some feeling of mastery. Do this by providing positive reinforcement to let students know when they have mastered a new concept or skill.

Encourage Thoroughness and Patience

- Try to communicate that the process is more important than the answer so that the student learns that it is OK to not have an instant solution. This is learned through your acceptance of his/her pace of doing things, through your refusal to let anxiety pressure you into giving the right answer, and through your example of problem solving through a step-by step process.

Experts (teachers) in a particular field are often so fluent in solving problems from that field that they can find it difficult to articulate the problem solving principles and strategies they use to novices (students) in their field because these principles and strategies are second nature to the expert. To teach students problem solving skills, a teacher should be aware of principles and strategies of good problem solving in his or her discipline .

The mathematician George Polya captured the problem solving principles and strategies he used in his discipline in the book How to Solve It: A New Aspect of Mathematical Method (Princeton University Press, 1957). The book includes a summary of Polya’s problem solving heuristic as well as advice on the teaching of problem solving.

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

Developing Problem-Solving Skills for Kids | Strategies & Tips

We've made teaching problem-solving skills for kids a whole lot easier! Keep reading and comment below with any other tips you have for your classroom!

Problem-Solving Skills for Kids: The Real Deal

Picture this: You've carefully created an assignment for your class. The step-by-step instructions are crystal clear. During class time, you walk through all the directions, and the response is awesome. Your students are ready! It's finally time for them to start working individually and then... 8 hands shoot up with questions. You hear one student mumble in the distance, "Wait, I don't get this" followed by the dreaded, "What are we supposed to be doing again?"

When I was a new computer science teacher, I would have this exact situation happen. As a result, I would end up scrambling to help each individual student with their problems until half the class period was eaten up. I assumed that in order for my students to learn best, I needed to be there to help answer questions immediately so they could move forward and complete the assignment.

Here's what I wish I had known when I started teaching coding to elementary students - the process of grappling with an assignment's content can be more important than completing the assignment's product. That said, not every student knows how to grapple, or struggle, in order to get to the "aha!" moment and solve a problem independently. The good news is, the ability to creatively solve problems is not a fixed skill. It can be learned by students, nurtured by teachers, and practiced by everyone!

Your students are absolutely capable of navigating and solving problems on their own. Here are some strategies, tips, and resources that can help:

Problem-Solving Skills for Kids: Student Strategies

These are strategies your students can use during independent work time to become creative problem solvers.

1. Go Step-By-Step Through The Problem-Solving Sequence

Post problem-solving anchor charts and references on your classroom wall or pin them to your Google Classroom - anything to make them accessible to students. When they ask for help, invite them to reference the charts first.

2. Revisit Past Problems

If a student gets stuck, they should ask themself, "Have I ever seen a problem like this before? If so, how did I solve it?" Chances are, your students have tackled something similar already and can recycle the same strategies they used before to solve the problem this time around.

3. Document What Doesn’t Work

Sometimes finding the answer to a problem requires the process of elimination. Have your students attempt to solve a problem at least two different ways before reaching out to you for help. Even better, encourage them write down their "Not-The-Answers" so you can see their thought process when you do step in to support. Cool thing is, you likely won't need to! By attempting to solve a problem in multiple different ways, students will often come across the answer on their own.

4. "3 Before Me"

Let's say your students have gone through the Problem Solving Process, revisited past problems, and documented what doesn't work. Now, they know it's time to ask someone for help. Great! But before you jump into save the day, practice "3 Before Me". This means students need to ask 3 other classmates their question before asking the teacher. By doing this, students practice helpful 21st century skills like collaboration and communication, and can usually find the info they're looking for on the way.

Problem-Solving Skills for Kids: Teacher Tips

These are tips that you, the teacher, can use to support students in developing creative problem-solving skills for kids.

1. Ask Open Ended Questions

When a student asks for help, it can be tempting to give them the answer they're looking for so you can both move on. But what this actually does is prevent the student from developing the skills needed to solve the problem on their own. Instead of giving answers, try using open-ended questions and prompts. Here are some examples:

2. Encourage Grappling

Grappling is everything a student might do when faced with a problem that does not have a clear solution. As explained in this article from Edutopia , this doesn't just mean perseverance! Grappling is more than that - it includes critical thinking, asking questions, observing evidence, asking more questions, forming hypotheses, and constructing a deep understanding of an issue.

There are lots of ways to provide opportunities for grappling. Anything that includes the Engineering Design Process is a good one! Examples include:

- Engineering or Art Projects

- Design-thinking challenges

- Computer science projects

- Science experiments

3. Emphasize Process Over Product

For elementary students, reflecting on the process of solving a problem helps them develop a growth mindset . Getting an answer "wrong" doesn't need to be a bad thing! What matters most are the steps they took to get there and how they might change their approach next time. As a teacher, you can support students in learning this reflection process.

4. Model The Strategies Yourself!

As creative problem-solving skills for kids are being learned, there will likely be moments where they are frustrated or unsure. Here are some easy ways you can model what creative problem-solving looks and sounds like.

- Ask clarifying questions if you don't understand something

- Admit when don't know the correct answer

- Talk through multiple possible outcomes for different situations

- Verbalize how you’re feeling when you find a problem

Practicing these strategies with your students will help create a learning environment where grappling, failing, and growing is celebrated!

Problem-Solving Skill for Kids

Did we miss any of your favorites? Comment and share them below!

Looking to add creative problem solving to your class?

Learn more about Kodable's free educator plan or create your free account today to get your students coding!

Kodable has everything you need to teach kids to code!

In just a few minutes a day, kids can learn all about the fundamentals of Computer Science - and so much more! With lessons ranging from zero to JavaScript, Kodable equips children for a digital future.

Why Every Educator Needs to Teach Problem-Solving Skills

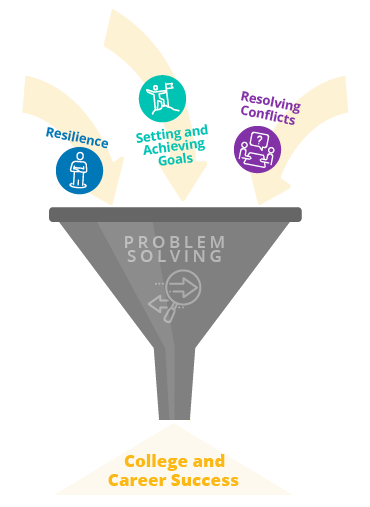

Strong problem-solving skills will help students be more resilient and will increase their academic and career success .

Want to learn more about how to measure and teach students’ higher-order skills, including problem solving, critical thinking, and written communication?

Problem-solving skills are essential in school, careers, and life.

Problem-solving skills are important for every student to master. They help individuals navigate everyday life and find solutions to complex issues and challenges. These skills are especially valuable in the workplace, where employees are often required to solve problems and make decisions quickly and effectively.

Problem-solving skills are also needed for students’ personal growth and development because they help individuals overcome obstacles and achieve their goals. By developing strong problem-solving skills, students can improve their overall quality of life and become more successful in their personal and professional endeavors.

Problem-Solving Skills Help Students…

develop resilience.

Problem-solving skills are an integral part of resilience and the ability to persevere through challenges and adversity. To effectively work through and solve a problem, students must be able to think critically and creatively. Critical and creative thinking help students approach a problem objectively, analyze its components, and determine different ways to go about finding a solution.

This process in turn helps students build self-efficacy . When students are able to analyze and solve a problem, this increases their confidence, and they begin to realize the power they have to advocate for themselves and make meaningful change.

When students gain confidence in their ability to work through problems and attain their goals, they also begin to build a growth mindset . According to leading resilience researcher, Carol Dweck, “in a growth mindset, people believe that their most basic abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work—brains and talent are just the starting point. This view creates a love of learning and a resilience that is essential for great accomplishment.”

Set and Achieve Goals

Students who possess strong problem-solving skills are better equipped to set and achieve their goals. By learning how to identify problems, think critically, and develop solutions, students can become more self-sufficient and confident in their ability to achieve their goals. Additionally, problem-solving skills are used in virtually all fields, disciplines, and career paths, which makes them important for everyone. Building strong problem-solving skills will help students enhance their academic and career performance and become more competitive as they begin to seek full-time employment after graduation or pursue additional education and training.

Resolve Conflicts

In addition to increased social and emotional skills like self-efficacy and goal-setting, problem-solving skills teach students how to cooperate with others and work through disagreements and conflicts. Problem-solving promotes “thinking outside the box” and approaching a conflict by searching for different solutions. This is a very different (and more effective!) method than a more stagnant approach that focuses on placing blame or getting stuck on elements of a situation that can’t be changed.

While it’s natural to get frustrated or feel stuck when working through a conflict, students with strong problem-solving skills will be able to work through these obstacles, think more rationally, and address the situation with a more solution-oriented approach. These skills will be valuable for students in school, their careers, and throughout their lives.

Achieve Success

We are all faced with problems every day. Problems arise in our personal lives, in school and in our jobs, and in our interactions with others. Employers especially are looking for candidates with strong problem-solving skills. In today’s job market, most jobs require the ability to analyze and effectively resolve complex issues. Students with strong problem-solving skills will stand out from other applicants and will have a more desirable skill set.

In a recent opinion piece published by The Hechinger Report , Virgel Hammonds, Chief Learning Officer at KnowledgeWorks, stated “Our world presents increasingly complex challenges. Education must adapt so that it nurtures problem solvers and critical thinkers.” Yet, the “traditional K–12 education system leaves little room for students to engage in real-world problem-solving scenarios.” This is the reason that a growing number of K–12 school districts and higher education institutions are transforming their instructional approach to personalized and competency-based learning, which encourage students to make decisions, problem solve and think critically as they take ownership of and direct their educational journey.

Problem-Solving Skills Can Be Measured and Taught

Research shows that problem-solving skills can be measured and taught. One effective method is through performance-based assessments which require students to demonstrate or apply their knowledge and higher-order skills to create a response or product or do a task.

What Are Performance-Based Assessments?

With the No Child Left Behind Act (2002), the use of standardized testing became the primary way to measure student learning in the U.S. The legislative requirements of this act shifted the emphasis to standardized testing, and this led to a decline in nontraditional testing methods .

But many educators, policy makers, and parents have concerns with standardized tests. Some of the top issues include that they don’t provide feedback on how students can perform better, they don’t value creativity, they are not representative of diverse populations, and they can be disadvantageous to lower-income students.

While standardized tests are still the norm, U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona is encouraging states and districts to move away from traditional multiple choice and short response tests and instead use performance-based assessment, competency-based assessments, and other more authentic methods of measuring students abilities and skills rather than rote learning.

Performance-based assessments measure whether students can apply the skills and knowledge learned from a unit of study. Typically, a performance task challenges students to use their higher-order skills to complete a project or process. Tasks can range from an essay to a complex proposal or design.

Preview a Performance-Based Assessment

Want a closer look at how performance-based assessments work? Preview CAE’s K–12 and Higher Education assessments and see how CAE’s tools help students develop critical thinking, problem-solving, and written communication skills.

Performance-Based Assessments Help Students Build and Practice Problem-Solving Skills

In addition to effectively measuring students’ higher-order skills, including their problem-solving skills, performance-based assessments can help students practice and build these skills. Through the assessment process, students are given opportunities to practically apply their knowledge in real-world situations. By demonstrating their understanding of a topic, students are required to put what they’ve learned into practice through activities such as presentations, experiments, and simulations.

This type of problem-solving assessment tool requires students to analyze information and choose how to approach the presented problems. This process enhances their critical thinking skills and creativity, as well as their problem-solving skills. Unlike traditional assessments based on memorization or reciting facts, performance-based assessments focus on the students’ decisions and solutions, and through these tasks students learn to bridge the gap between theory and practice.

Performance-based assessments like CAE’s College and Career Readiness Assessment (CRA+) and Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA+) provide students with in-depth reports that show them which higher-order skills they are strongest in and which they should continue to develop. This feedback helps students and their teachers plan instruction and supports to deepen their learning and improve their mastery of critical skills.

Explore CAE’s Problem-Solving Assessments

CAE offers performance-based assessments that measure student proficiency in higher-order skills including problem solving, critical thinking, and written communication.

- College and Career Readiness Assessment (CCRA+) for secondary education and

- Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA+) for higher education.

Our solution also includes instructional materials, practice models, and professional development.

We can help you create a program to build students’ problem-solving skills that includes:

- Measuring students’ problem-solving skills through a performance-based assessment

- Using the problem-solving assessment data to inform instruction and tailor interventions

- Teaching students problem-solving skills and providing practice opportunities in real-life scenarios

- Supporting educators with quality professional development

Get started with our problem-solving assessment tools to measure and build students’ problem-solving skills today! These skills will be invaluable to students now and in the future.

Ready to Get Started?

Learn more about cae’s suite of products and let’s get started measuring and teaching students important higher-order skills like problem solving..

Subscribe for Updates

7 ways to cultivate students’ problem-solving skills.

Parents, teachers, and other adults have developed a lot of skills and knowledge that can make it easy for us to solve problems. We’ve seen the situation before, and the solution may seem obvious to us, but young people are likely encountering the challenge for the first time. How do we help them tackle the problems themselves so that they develop the expertise they’ll need to solve other problems in the future?

Use these tips to help you think about how you support young people in solving challenges they encounter.

- Encourage “playing with” the problem. Encourage young people to throw out lots of ideas, make conjectures, and consider many different possibilities–even some that are outlandish. Look at the problem from many perspectives. This flexible thinking is an important skill for forming better solutions than the first that come to mind.

- Guide the young person to break a big problem into its parts. Then focus on aspects of the problem that the young person doesn’t understand or that seem like they have more potential to be solved.

- Ask the young person to work through the problem out loud. Not only does this help you coach the young person, but it also slows down the thinking process.

- Model and talk about the problem solving process, rather than focusing on getting the right answer. Talk through the steps you take and ask the young person to do the same so that it’s easier to learn.

- Have the student work through the problem on her or his own. Give only as much assistance as you need to when the young person is really stuck. And when you do so, limit your guidance to questions or suggestions that will help the young person move through a specific issue without solving the whole problem for her or him.

- Ask open-ended questions. Instead of, “Do you think that will fit in there?” you might ask a more open-ended question, such as, “What do you think it will take to get everything to fit inside?” Ask follow-up questions that encourage the young person to articulate their problem-solving process. This not only helps you learn and guide, but it reinforces the skills.

- Give positive reinforcement when young people overcome an obstacle or master a new problem-solving skill. Be specific in highlighting what they have done or learned.

Visit the store now >>

*Discount automatically applied at checkout.

Search Institute

3001 Broadway Street NE #310

Minneapolis, MN 55413

- 800.888.7828

- 612.376.8955

- Practical Solutions

- Funders & Partners

- Subscribe to our Newsletter

- Cancellations, Returns & Refunds

- Public Records

- Permissions Request Form

- Keep Connected

- Existing Customer Store Login

© 2021 Search Institute |

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Search Institute is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit charitable corporation. All contributions are tax deductible.

How to Develop Problem-Solving Skills in Students

Problem-solving skills – the term has become something of a cliché. It is used by anyone from students trying to pad out their résumés, to recruiters, to inspirational speakers trying to sell tickets to leadership seminars. Let’s unpack the term and what it could mean for you. What does it actually look like to have effective problem-solving skills? And how can you help your students develop these skills?

Why should you teach problem-solving skills to students?

Problem-solving skills make a person adaptable. ‘Problem-solving skills’ is a plural term, and therefore implied is a set of skills , which includes creativity, emotional intelligence and perseverance. This helps to explain why ‘problem-solving skills’ are so sought after in every field.

The earlier students are able to develop their problem-solving skills, the better the outcome. Problem-solving skills come in handy in nearly every situation: in the classroom, in the workplace, and generally in life. Put simply, problem-solving skills give a person independence, which is why it is so important to teach them from a young age. When you are no longer required to depend on parents or teachers for support and guidance, students become more and more independent, capable and are able to gain autonomy.

How to develop problem-solving skills in students

Teaching students problem-solving skills might look different depending on the subject a student is being taught. In maths, teach your students not only to do repetitive drills on the problems which are sure to come up in their exams, but also how to use their initiative to solve problems which have never been explained to them before. In science subjects, you might ask students to come up with their own experiment instead of giving them a pre-devised experiment. In English, encourage students to come up with their own textual analyses, rather than letting them rely on study guides and teaching for all of their ideas.

Problem-solving exercises to give to children

At a young age, children respond very well to games, which is why they are perfect for developing one’s problem-solving skills. Games can often present highly complex problem-solving situations to children – this is an environment of fun which promotes learning, but also provides a challenge! Websites such as this one can provide a series of recommendations based on different age ranges, which is a good way of progressively introducing more and more challenging problem-solving activities to children. Alternatively, this webpage provides more in-depth explanations of several simple games which can be used effectively in a classroom, by parents, or in one-to-one tuition.

Problem-solving exercises to give to teenagers

Just like a muscle, problem-solving skills are strengthened over time and with practice. So, make sure you keep encouraging your students’ growth in this field. Teenagers enjoy games, just like children (of course!), but they are also capable of more advanced problem-solving activities. Unlike most children, teenagers can work on developing complex critical thinking skills which, obviously, allow them to solve more advanced problems. You can find some free suggestions for developing critical thinking and problem-solving skills tailored towards teaching teens here and here .

If you loved this article, you will LOVE all of our other articles, such as: How to Study in Times of Stress , Benefits of Using Technology in the Classroom and How to Maximise Online Lessons for Tutors and Students

– Learnmate Tutoring .

Need an In-Person or Online Tutor? Search for a Tutor Here Today!

About learnmate.

Learnmate is a trusted Australian community platform that connects students who want 1:1 or small group study support, with tutors who are looking to share their knowledge and earn an income. From primary school to high school subjects — from science and maths to niche subjects like visual communication — Learnmate can help you improve academic performance or boost confidence, at your pace with the tutor that you choose.

We pride ourselves in offering a reliable and positive experience for both our students and tutors. Every tutor that joins the platform is vetted to meet a level of academic excellence, teaching qualification or relevant experience. All tutors are provided the opportunity to complete professional training.

Students and parents can easily find and screen for tutors based on their location, their subject results or skill level, and whether they provide in-person or online sessions. Learnmate is proud to provide tutors in Melbourne , Sydney , Geelong , Brisbane , Hobart , Canberra , Perth & Adelaide , and other locations.

Go online and let Learnmate help you get ahead. Start your search today.

"> "> share this post.

Article Author

Find online & in-person tutors near you, recent posts.

VCE SACs: Maximising Your Scores and Understanding Their Impact

Mastering VCE SACs: A Comprehensive Guide As part of the Victorian Certificate of Education (VCE), School Assessed Coursework (SACs) are...

March 26, 2024

Understanding Liquidity Analysis in VCE Accounting: Part One

In the latter part of the VCE Accounting course, students focus extensively on evaluating the financial performance of businesses. An...

Understanding Composite Functions in VCE Maths Methods: A Guide to Understanding and Applying Them

Hi there! My name is Daniela and I am a VCE Math Methods and Biology tutor on Learnmate. I graduated...

March 13, 2024

Don’t Just Tell Students to Solve Problems. Teach Them How.

The positive impact of an innovative uc san diego problem-solving educational curriculum continues to grow.

- Daniel Kane - [email protected]

Published Date

Share this:, article content.

Problem solving is a critical skill for technical education and technical careers of all types. But what are best practices for teaching problem solving to high school and college students?

The University of California San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering is on the forefront of efforts to improve how problem solving is taught. This UC San Diego approach puts hands-on problem-identification and problem-solving techniques front and center. Over 1,500 students across the San Diego region have already benefited over the last three years from this program. In the 2023-2024 academic year, approximately 1,000 upper-level high school students will be taking the problem solving course in four different school districts in the San Diego region. Based on the positive results with college students, as well as high school juniors and seniors in the San Diego region, the project is getting attention from educators across the state of California, and around the nation and the world.

{/exp:typographee}

In Summer 2023, th e 27 community college students who took the unique problem-solving course developed at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering thrived, according to Alex Phan PhD, the Executive Director of Student Success at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering. Phan oversees the project.

Over the course of three weeks, these students from Southwestern College and San Diego City College poured their enthusiasm into problem solving through hands-on team engineering challenges. The students brimmed with positive energy as they worked together.

What was noticeably absent from this laboratory classroom: frustration.

“In school, we often tell students to brainstorm, but they don’t often know where to start. This curriculum gives students direct strategies for brainstorming, for identifying problems, for solving problems,” sai d Jennifer Ogo, a teacher from Kearny High School who taught the problem-solving course in summer 2023 at UC San Diego. Ogo was part of group of educators who took the course themselves last summer.

The curriculum has been created, refined and administered over the last three years through a collaboration between the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering and the UC San Diego Division of Extended Studies. The project kicked off in 2020 with a generous gift from a local philanthropist.

Not getting stuck

One of the overarching goals of this project is to teach both problem-identification and problem-solving skills that help students avoid getting stuck during the learning process. Stuck feelings lead to frustration – and when it’s a Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) project, that frustration can lead students to feel they don’t belong in a STEM major or a STEM career. Instead, the UC San Diego curriculum is designed to give students the tools that lead to reactions like “this class is hard, but I know I can do this!” – as Ogo, a celebrated high school biomedical sciences and technology teacher, put it.

Three years into the curriculum development effort, the light-hearted energy of the students combined with their intense focus points to success. On the last day of the class, Mourad Mjahed PhD, Director of the MESA Program at Southwestern College’s School of Mathematics, Science and Engineering came to UC San Diego to see the final project presentations made by his 22 MESA students.

“Industry is looking for students who have learned from their failures and who have worked outside of their comfort zones,” said Mjahed. The UC San Diego problem-solving curriculum, Mjahed noted, is an opportunity for students to build the skills and the confidence to learn from their failures and to work outside their comfort zone. “And from there, they see pathways to real careers,” he said.

What does it mean to explicitly teach problem solving?

This approach to teaching problem solving includes a significant focus on learning to identify the problem that actually needs to be solved, in order to avoid solving the wrong problem. The curriculum is organized so that each day is a complete experience. It begins with the teacher introducing the problem-identification or problem-solving strategy of the day. The teacher then presents case studies of that particular strategy in action. Next, the students get introduced to the day’s challenge project. Working in teams, the students compete to win the challenge while integrating the day’s technique. Finally, the class reconvenes to reflect. They discuss what worked and didn't work with their designs as well as how they could have used the day’s problem-identification or problem-solving technique more effectively.

The challenges are designed to be engaging – and over three years, they have been refined to be even more engaging. But the student engagement is about much more than being entertained. Many of the students recognize early on that the problem-identification and problem-solving skills they are learning can be applied not just in the classroom, but in other classes and in life in general.

Gabriel from Southwestern College is one of the students who saw benefits outside the classroom almost immediately. In addition to taking the UC San Diego problem-solving course, Gabriel was concurrently enrolled in an online computer science programming class. He said he immediately started applying the UC San Diego problem-identification and troubleshooting strategies to his coding assignments.

Gabriel noted that he was given a coding-specific troubleshooting strategy in the computer science course, but the more general problem-identification strategies from the UC San Diego class had been extremely helpful. It’s critical to “find the right problem so you can get the right solution. The strategies here,” he said, “they work everywhere.”

Phan echoed this sentiment. “We believe this curriculum can prepare students for the technical workforce. It can prepare students to be impactful for any career path.”

The goal is to be able to offer the course in community colleges for course credit that transfers to the UC, and to possibly offer a version of the course to incoming students at UC San Diego.

As the team continues to work towards integrating the curriculum in both standardized high school courses such as physics, and incorporating the content as a part of the general education curriculum at UC San Diego, the project is expected to impact thousands more students across San Diego annually.

Portrait of the Problem-Solving Curriculum

On a sunny Wednesday in July 2023, an experiential-learning classroom was full of San Diego community college students. They were about half-way through the three-week problem-solving course at UC San Diego, held in the campus’ EnVision Arts and Engineering Maker Studio. On this day, the students were challenged to build a contraption that would propel at least six ping pong balls along a kite string spanning the laboratory. The only propulsive force they could rely on was the air shooting out of a party balloon.

A team of three students from Southwestern College – Valeria, Melissa and Alondra – took an early lead in the classroom competition. They were the first to use a plastic bag instead of disposable cups to hold the ping pong balls. Using a bag, their design got more than half-way to the finish line – better than any other team at the time – but there was more work to do.

As the trio considered what design changes to make next, they returned to the problem-solving theme of the day: unintended consequences. Earlier in the day, all the students had been challenged to consider unintended consequences and ask questions like: When you design to reduce friction, what happens? Do new problems emerge? Did other things improve that you hadn’t anticipated?

Other groups soon followed Valeria, Melissa and Alondra’s lead and began iterating on their own plastic-bag solutions to the day’s challenge. New unintended consequences popped up everywhere. Switching from cups to a bag, for example, reduced friction but sometimes increased wind drag.

Over the course of several iterations, Valeria, Melissa and Alondra made their bag smaller, blew their balloon up bigger, and switched to a different kind of tape to get a better connection with the plastic straw that slid along the kite string, carrying the ping pong balls.

One of the groups on the other side of the room watched the emergence of the plastic-bag solution with great interest.

“We tried everything, then we saw a team using a bag,” said Alexander, a student from City College. His team adopted the plastic-bag strategy as well, and iterated on it like everyone else. They also chose to blow up their balloon with a hand pump after the balloon was already attached to the bag filled with ping pong balls – which was unique.

“I don’t want to be trying to put the balloon in place when it's about to explode,” Alexander explained.

Asked about whether the structured problem solving approaches were useful, Alexander’s teammate Brianna, who is a Southwestern College student, talked about how the problem-solving tools have helped her get over mental blocks. “Sometimes we make the most ridiculous things work,” she said. “It’s a pretty fun class for sure.”

Yoshadara, a City College student who is the third member of this team, described some of the problem solving techniques this way: “It’s about letting yourself be a little absurd.”

Alexander jumped back into the conversation. “The value is in the abstraction. As students, we learn to look at the problem solving that worked and then abstract out the problem solving strategy that can then be applied to other challenges. That’s what mathematicians do all the time,” he said, adding that he is already thinking about how he can apply the process of looking at unintended consequences to improve both how he plays chess and how he goes about solving math problems.

Looking ahead, the goal is to empower as many students as possible in the San Diego area and beyond to learn to problem solve more enjoyably. It’s a concrete way to give students tools that could encourage them to thrive in the growing number of technical careers that require sharp problem-solving skills, whether or not they require a four-year degree.

You May Also Like

Medical innovator: farah sheikh, uc san diego roboticists shine at human robot interaction 2024 conference, new genetic analysis tool tracks risks tied to crispr edits, uc san diego engineers inducted into 2024 class of the aimbe college of fellows, stay in the know.

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.

You have been successfully subscribed to the UC San Diego Today Newsletter.

Campus & Community

Arts & culture, visual storytelling.

- Media Resources & Contacts

Signup to get the latest UC San Diego newsletters delivered to your inbox.

Award-winning publication highlighting the distinction, prestige and global impact of UC San Diego.

Popular Searches: Covid-19 Ukraine Campus & Community Arts & Culture Voices

Mastering Problem-Solving Skills: Definition and Examples

Problem-Solving Skills – Introduction

Problem-solving skills are fundamental abilities that enable individuals to tackle complex challenges, overcome obstacles, and devise effective solutions. These skills are invaluable across various domains, from personal life to professional endeavors. As they empower individuals to analyze situations critically and implement strategies to achieve desired outcomes.

Definition of Problem-Solving Skills

Problem-solving skills encompass a range of cognitive processes and techniques aimed at identifying, analyzing, and resolving problems. These skills involve the application of logical reasoning, creativity, critical thinking, and decision-making to address issues and make sound judgments.

Understanding the Problem

Before attempting to solve a problem, it is essential to fully comprehend its nature and scope. This involves identifying the underlying issues, determining the goals to be achieved, and clarifying any constraints or limitations that may affect the solution.

Example: In a business context, understanding a decline in sales requires analyzing market trends. Customer feedback, and internal factors such as product quality and pricing strategies.

Analyzing Options

Once the problem is defined, individuals need to explore various solutions or approaches to address it. This stage involves brainstorming ideas, evaluating alternatives, and considering the potential outcomes of each option.

Example: When faced with a budget shortfall, a project manager may analyze different cost-cutting measures. Such as renegotiating contracts, reducing non-essential expenses, or reallocating resources.

Implementing Solutions

After selecting the most viable solution, the next step is implementing it effectively. This often requires planning, organization, and coordination to execute the chosen approach and monitor its progress toward achieving the desired results.

Example: To improve customer satisfaction, a restaurant manager may introduce a new training program for staff, streamline service processes, and solicit feedback from patrons to assess the impact of the changes.

Evaluating Results

Once the solution has been implemented, it is crucial to evaluate its effectiveness and identify any unforeseen consequences or areas for improvement. This feedback loop allows individuals to refine their problem-solving strategies and learn from their experiences.

Example: A teacher who introduces a new teaching method in the classroom may assess student performance, gather feedback from students and colleagues, and adjust the approach based on the observed outcomes.

Continuous Improvement

Problem-solving skills are not static but evolve through practice and experience. Individuals can enhance their abilities by seeking feedback, learning from failures, and continuously challenging themselves to solve increasingly complex problems.

Example: A software developer may regularly participate in coding challenges, attend workshops on emerging technologies, and collaborate with peers to stay updated and sharpen their programming skills.

In conclusion, problem-solving skills are essential competencies that enable individuals to navigate challenges, innovate solutions, and achieve their goals effectively. By understanding the problem, analyzing options, implementing solutions, evaluating results, and continuously improving. Individuals can develop mastery in problem-solving across diverse contexts. These skills benefit individuals in their personal and professional lives and contribute to the advancement of society as a whole.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Teach educator.

"Teach Educator" is a dynamic and innovative platform designed to empower educators with the tools and resources they need to excel in their teaching journey. This comprehensive solution goes beyond traditional methods, offering a collaborative space where educators can access cutting-edge teaching techniques, share best practices, and engage in professional development.

Privacy Policy

Live Cricket Score

Recent Post

Define Professional Development with Examples – Latest

April 3, 2024

Prompt Engineering Is the New ChatGPT Skill Employer – Latest

Best Guide to Working at Netflix – Latest 2024

Copyright © 2024 Teach Educator

Privacy policy

Discover more from Teach Educator

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Explore Jobs

- Jobs Near Me

- Remote Jobs

- Full Time Jobs

- Part Time Jobs

- Entry Level Jobs

- Work From Home Jobs

Find Specific Jobs

- $15 Per Hour Jobs

- $20 Per Hour Jobs

- Hiring Immediately Jobs

- High School Jobs

- H1b Visa Jobs

Explore Careers

- Business And Financial

- Architecture And Engineering

- Computer And Mathematical

Explore Professions

- What They Do

- Certifications

- Demographics

Best Companies

- Health Care

- Fortune 500

Explore Companies

- CEO And Executies

- Resume Builder

- Career Advice

- Explore Majors

- Questions And Answers

- Interview Questions

What Are Problem-Solving Skills? (Definition, Examples, And How To List On A Resume)

- What Are Skills Employers Look For?

- What Are Inductive Reasoning?

- What Are Problem Solving Skills?

- What Are Active Listening Skills?

- What Are Management Skills?

- What Are Attention To Detail?

- What Are Detail Oriented Skills?

- What Are Domain Knowledge?

- What Is Professionalism?

- What Are Rhetorical Skills?

- What Is Integrity?

- What Are Persuasion Skills?

- How To Start A Conversation

- How To Write A Conclusion For A Research Paper

- Team Player

- Visual Learner

- High Income Skills

- The Most Important Professional Skills

Find a Job You Really Want In

Summary. Problem-solving skills include analysis, creativity, prioritization, organization, and troubleshooting. To solve a problem, you need to use a variety of skills based on the needs of the situation.

Most jobs essentially boil down to identifying and solving problems consistently and effectively. That’s why employers value problem-solving skills in job candidates for just about every role.

We’ll cover problem-solving methods, ways to improve your problem-solving skills, and examples of showcasing your problem-solving skills during your job search .

Key Takeaways:

If you can show off your problem-solving skills on your resume , in your cover letter , and during a job interview, you’ll be one step closer to landing a job.

Companies rely on employees who can handle unexpected challenges, identify persistent issues, and offer workable solutions in a positive way.

It is important to improve problem solving skill because this is a skill that can be cultivated and nurtured so you can become better at dealing with problems over time.

Types of Problem-Solving Skills

How to improve your problem-solving skills, example answers to problem-solving interview questions, how to show off problem-solving skills on a resume, example resume and cover letter with problem-solving skills, more about problem-solving skills, problem solving skills faqs.

- Sign Up For More Advice and Jobs

Problem-solving skills are skills that help you identify and solve problems effectively and efficiently . Your ability to solve problems is one of the main ways that hiring managers and recruiters assess candidates, as those with excellent problem-solving skills are more likely to autonomously carry out their responsibilities.

A true problem solver can look at a situation, find the cause of the problem (or causes, because there are often many issues at play), and then come up with a reasonable solution that effectively fixes the problem or at least remedies most of it.

The ability to solve problems is considered a soft skill , meaning that it’s more of a personality trait than a skill you’ve learned at school, on the job, or through technical training.

That being said, your proficiency with various hard skills will have a direct bearing on your ability to solve problems. For example, it doesn’t matter if you’re a great problem-solver; if you have no experience with astrophysics, you probably won’t be hired as a space station technician .

Problem-solving is considered a skill on its own, but it’s supported by many other skills that can help you be a better problem solver. These skills fall into a few different categories of problem-solving skills.

Problem recognition and analysis. The first step is to recognize that there is a problem and discover what it is or what the root cause of it is.

You can’t begin to solve a problem unless you’re aware of it. Sometimes you’ll see the problem yourself and other times you’ll be told about the problem. Both methods of discovery are very important, but they can require some different skills. The following can be an important part of the process:

Active listening

Data analysis

Historical analysis

Communication

Create possible solutions. You know what the problem is, and you might even know the why of it, but then what? Your next step is the come up with some solutions.

Most of the time, the first solution you come up with won’t be the right one. Don’t fall victim to knee-jerk reactions; try some of the following methods to give you solution options.

Brainstorming

Forecasting

Decision-making

Topic knowledge/understanding

Process flow

Evaluation of solution options. Now that you have a lot of solution options, it’s time to weed through them and start casting some aside. There might be some ridiculous ones, bad ones, and ones you know could never be implemented. Throw them away and focus on the potentially winning ideas.

This step is probably the one where a true, natural problem solver will shine. They intuitively can put together mental scenarios and try out solutions to see their plusses and minuses. If you’re still working on your skill set — try listing the pros and cons on a sheet of paper.

Prioritizing

Evaluating and weighing

Solution implementation. This is your “take action” step. Once you’ve decided which way to go, it’s time to head down that path and see if you were right. This step takes a lot of people and management skills to make it work for you.

Dependability

Teambuilding

Troubleshooting

Follow-Through

Believability

Trustworthiness

Project management

Evaluation of the solution. Was it a good solution? Did your plan work or did it fail miserably? Sometimes the evaluation step takes a lot of work and review to accurately determine effectiveness. The following skills might be essential for a thorough evaluation.

Customer service

Feedback responses

Flexibility

You now have a ton of skills in front of you. Some of them you have naturally and some — not so much. If you want to solve a problem, and you want to be known for doing that well and consistently, then it’s time to sharpen those skills.

Develop industry knowledge. Whether it’s broad-based industry knowledge, on-the-job training , or very specific knowledge about a small sector — knowing all that you can and feeling very confident in your knowledge goes a long way to learning how to solve problems.

Be a part of a solution. Step up and become involved in the problem-solving process. Don’t lead — but follow. Watch an expert solve the problem and, if you pay attention, you’ll learn how to solve a problem, too. Pay attention to the steps and the skills that a person uses.

Practice solving problems. Do some role-playing with a mentor , a professor , co-workers, other students — just start throwing problems out there and coming up with solutions and then detail how those solutions may play out.

Go a step further, find some real-world problems and create your solutions, then find out what they did to solve the problem in actuality.

Identify your weaknesses. If you could easily point out a few of your weaknesses in the list of skills above, then those are the areas you need to focus on improving. How you do it is incredibly varied, so find a method that works for you.

Solve some problems — for real. If the opportunity arises, step in and use your problem-solving skills. You’ll never really know how good (or bad) you are at it until you fail.

That’s right, failing will teach you so much more than succeeding will. You’ll learn how to go back and readdress the problem, find out where you went wrong, learn more from listening even better. Failure will be your best teacher ; it might not make you feel good, but it’ll make you a better problem-solver in the long run.

Once you’ve impressed a hiring manager with top-notch problem-solving skills on your resume and cover letter , you’ll need to continue selling yourself as a problem-solver in the job interview.

There are three main ways that employers can assess your problem-solving skills during an interview:

By asking questions that relate to your past experiences solving problems

Posing hypothetical problems for you to solve

By administering problem-solving tests and exercises

The third method varies wildly depending on what job you’re applying for, so we won’t attempt to cover all the possible problem-solving tests and exercises that may be a part of your application process.

Luckily, interview questions focused on problem-solving are pretty well-known, and most can be answered using the STAR method . STAR stands for situation, task, action, result, and it’s a great way to organize your answers to behavioral interview questions .

Let’s take a look at how to answer some common interview questions built to assess your problem-solving capabilities:

At my current job as an operations analyst at XYZ Inc., my boss set a quarterly goal to cut contractor spending by 25% while maintaining the same level of production and moving more processes in-house. It turned out that achieving this goal required hiring an additional 6 full-time employees, which got stalled due to the pandemic. I suggested that we widen our net and hire remote employees after our initial applicant pool had no solid candidates. I ran the analysis on overhead costs and found that if even 4 of the 6 employees were remote, we’d save 16% annually compared to the contractors’ rates. In the end, all 6 employees we hired were fully remote, and we cut costs by 26% while production rose by a modest amount.

I try to step back and gather research as my first step. For instance, I had a client who needed a graphic designer to work with Crello, which I had never seen before, let alone used. After getting the project details straight, I began meticulously studying the program the YouTube tutorials, and the quick course Crello provides. I also reached out to coworkers who had worked on projects for this same client in the past. Once I felt comfortable with the software, I started work immediately. It was a slower process because I had to be more methodical in my approach, but by putting in some extra hours, I turned in the project ahead of schedule. The client was thrilled with my work and was shocked to hear me joke afterward that it was my first time using Crello.

As a digital marketer , website traffic and conversion rates are my ultimate metrics. However, I also track less visible metrics that can illuminate the story behind the results. For instance, using Google Analytics, I found that 78% of our referral traffic was coming from one affiliate, but that these referrals were only accounting for 5% of our conversions. Another affiliate, who only accounted for about 10% of our referral traffic, was responsible for upwards of 30% of our conversions. I investigated further and found that the second, more effective affiliate was essentially qualifying our leads for us before sending them our way, which made it easier for us to close. I figured out exactly how they were sending us better customers, and reached out to the first, more prolific but less effective affiliate with my understanding of the results. They were able to change their pages that were referring us traffic, and our conversions from that source tripled in just a month. It showed me the importance of digging below the “big picture” metrics to see the mechanics of how revenue was really being generated through digital marketing.

You can bring up your problem-solving skills in your resume summary statement , in your work experience , and under your education section , if you’re a recent graduate. The key is to include items on your resume that speak direclty to your ability to solve problems and generate results.

If you can, quantify your problem-solving accomplishments on your your resume . Hiring managers and recruiters are always more impressed with results that include numbers because they provide much-needed context.

This sample resume for a Customer Service Representative will give you an idea of how you can work problem solving into your resume.

Michelle Beattle 111 Millennial Parkway Chicago, IL 60007 (555) 987-6543 [email protected] Professional Summary Qualified Customer Services Representative with 3 years in a high-pressure customer service environment. Professional, personable, and a true problem solver. Work History ABC Store — Customer Service Representative 01/2015 — 12/2017 Managed in-person and phone relations with customers coming in to pick up purchases, return purchased products, helped find and order items not on store shelves, and explained details and care of merchandise. Became a key player in the customer service department and was promoted to team lead. XYZ Store — Customer Service Representative/Night Manager 01/2018 — 03/2020, released due to Covid-19 layoffs Worked as the night manager of the customer service department and filled in daytime hours when needed. Streamlined a process of moving customers to the right department through an app to ease the burden on the phone lines and reduce customer wait time by 50%. Was working on additional wait time problems when the Covid-19 pandemic caused our stores to close permanently. Education Chicago Tech 2014-2016 Earned an Associate’s Degree in Principles of Customer Care Skills Strong customer service skills Excellent customer complaint resolution Stock record management Order fulfillment New product information Cash register skills and proficiency Leader in problem solving initiatives

You can see how the resume gives you a chance to point out your problem-solving skills and to show where you used them a few times. Your cover letter is your chance to introduce yourself and list a few things that make you stand out from the crowd.

Michelle Beattle 111 Millennial Parkway Chicago, IL 60007 (555) 987-6543 [email protected] Dear Mary McDonald, I am writing in response to your ad on Zippia for a Customer Service Representative . Thank you for taking the time to consider me for this position. Many people believe that a job in customer service is simply listening to people complain all day. I see the job as much more than that. It’s an opportunity to help people solve problems, make their experience with your company more enjoyable, and turn them into life-long advocates of your brand. Through my years of experience and my educational background at Chicago Tech, where I earned an Associate’s Degree in the Principles of Customer Care, I have learned that the customers are the lifeline of the business and without good customer service representatives, a business will falter. I see it as my mission to make each and every customer I come in contact with a fan. I have more than five years of experience in the Customer Services industry and had advanced my role at my last job to Night Manager. I am eager to again prove myself as a hard worker, a dedicated people person, and a problem solver that can be relied upon. I have built a professional reputation as an employee that respects all other employees and customers, as a manager who gets the job done and finds solutions when necessary, and a worker who dives in to learn all she can about the business. Most of my customers have been very satisfied with my resolution ideas and have returned to do business with us again. I believe my expertise would make me a great match for LMNO Store. I have enclosed my resume for your review, and I would appreciate having the opportunity to meet with you to further discuss my qualifications. Thank you again for your time and consideration. Sincerely, Michelle Beattle

You’ve no doubt noticed that many of the skills listed in the problem-solving process are repeated. This is because having these abilities or talents is so important to the entire course of getting a problem solved.

In fact, they’re worthy of a little more attention. Many of them are similar, so we’ll pull them together and discuss how they’re important and how they work together.