- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

How D-Day Changed the Course of WWII

By: Roy Wenzl

Updated: March 13, 2024 | Original: April 23, 2018

The D-Day military invasion that helped to end World War II was one the most ambitious and consequential military campaigns in human history. In its strategy and scope—and its enormous stakes for the future of the free world—historians regard it among the greatest military achievements ever.

D-Day, code-named Operation Overlord, launched on June 6, 1944, after the commanding Allied general, Dwight D. Eisenhower , ordered the largest invasion force in history—hundreds of thousands of American, British, Canadian and other troops—to ship across across the English Channel and come ashore on the beaches of Normandy , on France’s northern coast. After almost five years of war, nearly all of Western Europe was occupied by German troops or held by fascist governments, like those of Spain and Italy. The Western Allies’ goal: to put an end to the Germany army and, by extension, to topple Adolf Hitler ’s barbarous Nazi regime.

Here’s why D-Day remains an event of great magnitude, and why we owe those fighters so much:

Halting the Nazi Genocidal Machine

German armies during World War II overran most of Europe and North Africa and much of the western Soviet Union . They set up murderous police states everywhere they went, then hunted down and imprisoned millions. With gas chambers and firing squads they killed 6 million Jewish people and millions more Poles, Russians, gays, disabled people and others undesirable to the Nazi regime, which sought to engineer a master Germanic race.

“It’s hard to imagine what the consequences would have been had the Allies lost,” says Timothy Rives, deputy director of the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas. “You could make the argument that they saved the world. A few months after D-Day, General Eisenhower visited a German death camp, and wrote: “We are told the American soldier does not know what he is fighting for. Now, at least, he will know what he is fighting against.”

Invasion Went Beyond the Beaches

The “D” in D-Day means simply “Day,” as in “The day we invade.” (The military had to call it something.) But to those who survived June 6, and the subsequent summer-long incursion, D-Day meant sheer terror. Raymond Hoffman, from Lowell, Massachusetts, gave an oral history interview in 1978 at the Eisenhower Library about the life-and-death fear he survived as a 22-year-old paratrooper in the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division.

On D-Day he parachuted with a hard thud into a Normandy cow pasture only minutes after midnight—and he heard footsteps approaching fast, even before he could unhook himself from his parachute straps.

“Boy, here I am,” he thought. “Five minutes on the ground and I’m about to get it. And I’m flat on my back, and…I got to roll, and I can’t get to my weapon and now… I can’t find my knife! And the footsteps have stopped…and (suddenly) I am looking up into the eyes of a big, brown cow.”

That was worth a grin then. But hours later, “some mysteries in life were removed,” Hoffman said.

In a gunfight with German soldiers, where bullets flew so thick that no one dared raise their heads to look up, he removed “the mystery” he’d pondered for months—about whether fear in combat would compel him to run or to fight.

He fought. And there was no longer any mystery: “You now know what it is like to be fired upon,” he said, “as well as to fire.”

An Effort of Staggering Scale

“I had some fun here one day looking up statistics, of all the stuff the Allies piled up on the beaches of southern England to support the invasion,” says Rives. “They had massive ammo dumps, and supply dumps, and in one of those supply dumps they had piled up 3,500 tons of bath soap—which Eisenhower later sent into France so the soldiers could take baths.

“He had 3 million troops under his command, and what they all devoured in just one day was stupendous,” says Rives. According to historian Rick Atkinson, commanders had “calculated daily combat consumption, from fuel to bullets to chewing gum, at 41.298 pounds per soldier. Sixty million K-rations, enough to feed the invaders for a month, were packed in 500-ton bales.”

Steep Casualties

German machine-gunners mowed down hundreds of Allied soldiers before they ever got off the landing boats onto the Normandy beaches. But Eisenhower overwhelmed them, Rives says, with 160,000 assault troops, 12,000 aircraft and 200,000 sailors manning 7,000 sea vessels.

Their losses were steep: The eight assault divisions now ashore had suffered 12,000 killed, wounded and missing, with thousands more unaccounted for, according to Atkinson. The Americans lost 8,230 of the total.

“Many were felled by 9.6-gram bullets moving at 2,000 to 4,000 feet per second,” Atkinson wrote. “Such specks of steel could destroy a world, cell by cell.”

Three thousand French civilians were killed in the invasion, mostly by Allied bombs or shell fire. By then the French had lost so much in the war that they’d run out of medical supplies. Some injured citizens were reduced to disinfecting their wounds with calvados, the local brandy fermented from apples, according to Atkinson.

But when the Allied soldiers marched inland from the beaches, the French cheered, many of them giving soldiers flowers, many of them sobbing in happiness.

D-Day Strategy

No one thought victory was sure. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had pestered Eisenhower and President Franklin Roosevelt for two years before D-Day, pleading that they avoid Normandy and instead pursue a slower, less dangerous strategy, putting more troops into Italy and southern France.

But the Germans had killed tens of millions of civilians and soldiers in the Soviet Union, and the Soviets desperately wanted the Allies to bleed the Germany army by opening up a second front of battle. Eisenhower thought it disgraceful to avoid Normandy, and thought Normandy was the best military move, not only to win but to shorten the war.

The Allies had long planned the invasion for a narrow window in the lunar cycle that would provide both maximum moonlight to illuminate landing places for gliders—and low tides at dawn to reveal the German’s extensive underwater coastal defenses. Poor weather forced Allied troops to delay the operation a day, cutting into that window. But in a stroke of luck, German forecasters predicted that gale-force winds and rough seas would deter the invasion even longer, so the Nazis redeployed some of their forces away from the coast. German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel even traveled home to celebrate his wife’s birthday, bringing her a pair of Parisian shoes.

On the night before the invasion, Eisenhower penciled himself an “In case of failure” note, to be published if necessary: “If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone,” he wrote.

“Of all the documents we have from his time in the Army and in his eight years of the presidency, I regard that as our most significant document here,” Rives said of the collection at the Eisenhower Library. “It shows the character of the man who led it all.”

Eisenhower hated war. Years after the war ended, he gave a speech, with a paragraph that can be seen engraved in the marble stone wall surrounding his tomb in Abilene, Kansas.

“Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies in the final sense a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children. This is not a way of life at all in any true sense.”

The Importance of the D-Day Victory

Most battles are quickly forgotten. But all free nations owe their culture and democracy to D-Day, which can be grouped among some of the most epic victories in history. They include George Washington ’s defeat of the British army at Yorktown in 1781, which allowed the American experiment in democracy to survive, and to inspire oppressed people everywhere.

And in 490 and 480 B.C, the small armies and navies of Greece defeated the huge invading forces of the Persian Empire at the battles of Marathon and Salamis. The Greeks saved not only themselves, but their democracy, classic literature, art and architecture, philosophy and much more.

Historians put D-Day in the same category of greatness.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Written by: Edward G. Lengel, The National World War II Museum

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain the causes and effects of the victory of the United States and its allies over the Axis Powers

Suggested Sequencing

Use this narrative with the Dwight Eisenhower, D-Day Statement, 1944 Primary Source to give students a fuller understanding of the campaign. This narrative can also be used with the Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima Narrative and the Phil “Bo” Perabo, Letter Home, 1945 Primary Source to showcase American soldiers’ experiences during WWII.

Allied leaders had debated opening a second front in German-occupied western Europe as early as 1942. Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin’s pressure to launch such a front was unrelenting and reiterated at every Allied conference. Developing the means to launch a successful invasion was far from easy, however. Until 1944, the United States and Great Britain lacked the forces and the means to attack the Germans in France and successfully open a beachhead to invade Normandy. And success was all important. If a large-scale invasion failed, the results would be disastrous, and not just in terms of troops lost. Assembling another invasion might take years.

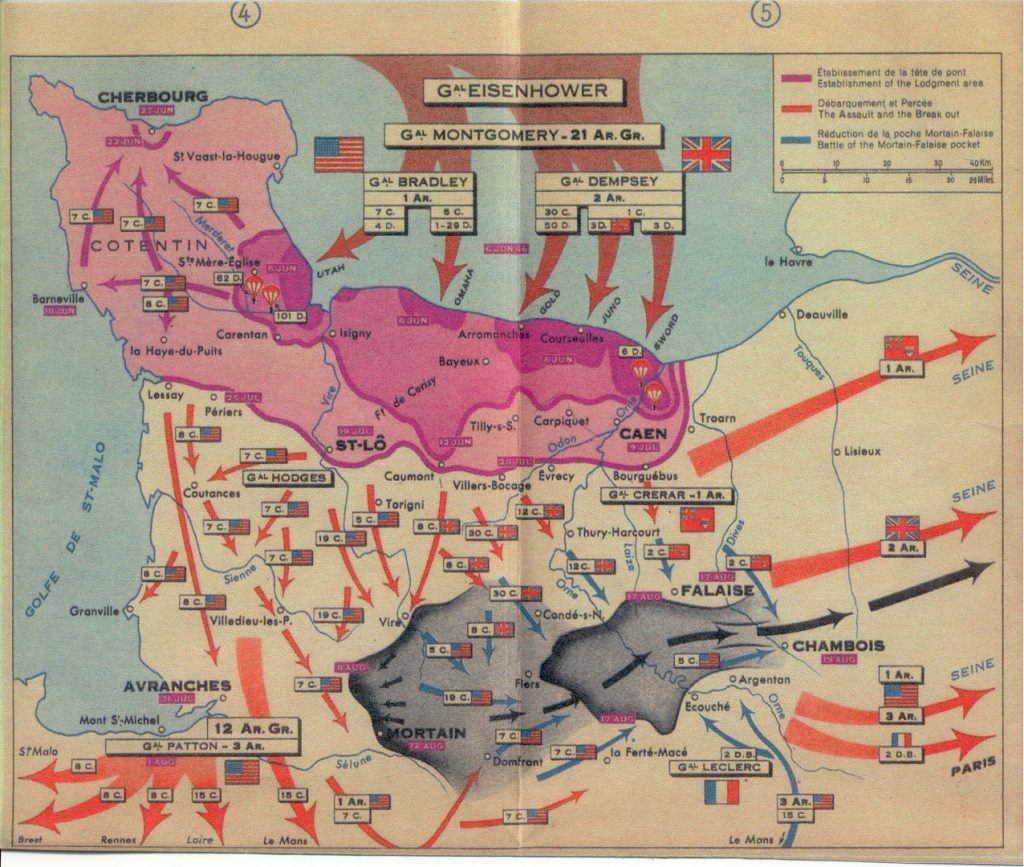

By the spring of 1944, however, the outlines of what came to be called Operation Overlord were complete. Five divisions of American, Canadian, and British troops, supported by three airborne divisions of paratroopers and glider-borne soldiers, were to land on beachheads in Normandy. After securing the landing beaches, establishing a firm perimeter, capturing the port of Cherbourg, establishing portable harbors there for resupply, and assembling armored reinforcements, Allied forces could drive inland to begin the liberation of France.

Several moving pieces had to be put in place before the plan could get underway. First, adequate naval support, and especially transport and landing craft, had to be secured – an especially difficult undertaking given the demands of warfare in both Europe and the far-flung Pacific, where amphibious landings on the Japanese-held islands were frequent. Second, American and British air forces had to work in complete coordination with ground forces, not only placing paratroopers and glider-borne forces on target but also preventing German efforts to move reinforcements and especially panzer divisions toward the beaches. Third, Free French forces, some owing allegiance to General Charles De Gaulle and others not, had to be alerted to the invasion and their support coordinated. Finally, an elaborate campaign of deception was established to convince the Germans that the primary Allied invasion would take place not in Normandy but at the heavily defended and more centrally located Pas de Calais, at the narrowest point of the English Channel.

Coordinating these factors, many under the control of disparate personalities who had different ideas about how the invasion should take place, took months. The Allied Supreme Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower, working with British General Bernard Law Montgomery (in command of the invading ground forces) and British commanders of the supporting naval and air forces, finally thought he had his pieces assembled at the beginning of June, but there was one final decision to be made. Because of the tides and other factors, the Allies could land at the beaches of Normandy only on certain dates, but weather reports suggested unsettled weather in early June. In a tense meeting at his headquarters in Bletchley Park, England, Eisenhower elected to gamble on a break in the weather and said “Go” for the invasion on June 6, 1944.

At this critical moment, Eisenhower’s leadership abilities came to the fore. Rather than remaining at headquarters, he made a point of visiting, encouraging, and even joking with the troops assembled to carry out the invasion. He dispatched a message to them declaring, “You are about to embark upon a great crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. . . . I have full confidence in your devotion to duty and skill in battle. We will accept nothing less than full Victory. Good luck! And let us all beseech the blessing of Almighty God upon this great and noble undertaking.” But the general also penned a draft dispatch to be sent in case the invasion failed, taking full responsibility upon himself.

American and British airborne troops carried out the first phase of the invasion by landing around the coastal villages behind German beach defenses on the night of June 5-6. Although badly scattered and forced to work in small, poorly armed groups, they succeeded in their primary mission of seizing – and, where necessary, destroying – important bridges and crossroads to hold back enemy reinforcements. U.S. Army Rangers carried out a heroic and costly assault against German cliffside emplacements at Pointe du Hoc overlooking Omaha Beach, only to discover that the enemy had already dismantled their heavy guns.

The primary invasion took place on five Normandy beaches, code-named (from west to east) Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword. British and Canadian troops landed at the latter three beaches against weaker-than-expected enemy opposition and quickly seized their immediate objectives. At Utah, thanks in part to airborne support inland, the U.S. 4th Division landed successfully and laid the groundwork for the capture of the Cotentin Peninsula and the all-important port of Cherbourg.

At Omaha Beach, however, facing strong tides and mistakes by inexperienced infantry and naval forces, the invasion nearly foundered. Here, troops of the U.S. 29th and 1st Divisions (the famous “Big Red One”) faced a strong defense from well dug-in and determined German infantry that they struggled to overcome. Heavy casualties on the beaches led General Omar Bradley, commanding the U.S. First Army, briefly to consider abandoning the beachhead. But the infantry refused to give up and, with great courage and sacrifice, they finally managed to break the German defenses and establish a defensive perimeter. Fortunately, Allied ground attack aircraft also succeeded in their primary missions of supporting airborne troops inland and inflicting heavy casualties on German armored and infantry forces as they rushed toward the beaches.

Although casualties had been heavy at places like Omaha Beach, overall Allied losses for June 6 totaled 4,900 killed, wounded, and missing – far lower than Eisenhower and his generals had anticipated. The five Allied beachheads were linked together by June 12, and by the end of the month, Cherbourg had been captured. Firmly entrenched and supplied, thanks in part to elaborate and expensive portable harbors codenamed Mulberry that were established on the Normandy beaches (although one was destroyed by a storm on June 19), the Allies had succeeded in forming the long-awaited second front. Although the drive inland proved far more difficult than anticipated, the process of the liberation of Western Europe had begun.

One of the Mulberry harbors established on the D-Day beaches in 1944, which allowed the Allies to secure supplies to liberate France.

Review Questions

The outcome of the events depicted in the photograph resulted in

- the liberation of Western Europe

- the fall of Japan

- the creation of the League of Nations

- the presidential election of Herbert Hoover

2. The Allied leader overseeing D-Day was

- Erwin Rommel

- Dwight Eisenhower

- George Marshall

- Bernard Law Montgomery

3. One of the key concerns in Allied planning for Operation Overlord was

- securing the support of the Soviet Union

- amassing enough naval support to transport and land troops and equipment

- getting the help of the French resistance

- getting the approval of Harry Truman

4. The D-Day invasion marked the

- beginning of the development of an atomic bomb

- fall of Benito Mussolini’s Italy

- surrender of Adolf Hitler to Allied troops

- opening of a second front against Nazi Germany

5. The Normandy invasion in World War II was considered necessary to

- stop the spread of Japanese imperialism

- relieve the pressure on the eastern front

- save Italy from falling to Nazi Germany

- keep the Nazis from developing a nuclear bomb

6. The night before the D-Day landings American and British troops successfully

- surprised and destroyed German army headquarters

- dismantled the bulk of Nazi shore defenses

- captured vital bridges and crossroads

- captured Adolf Hitler

Free Response Questions

- Explain the need for the D-Day invasion in World War II.

- Explain the Allies’ challenges in planning the D-Day invasion in World War II.

AP Practice Questions

“SUPREME HEADQUARTERS ALLIED EXPEDITIONARY FORCE Soldiers, Sailors, and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force! You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hope and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other Fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world. Your task will not be an easy one. Your enemy is well trained, well equipped and battle-hardened. He will fight savagely.”

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Order of the Day, 1944

1. The sentiments expressed in Eisenhower’s “Order of the Day” most directly led to

- the collapse of fascist regimes in Europe

- the fall of communism in Eastern Europe

- the dropping of the atomic bomb

- the beginning of the Cold War

2. The situation referred to in the excerpt from Eisenhower’s Order of the Day was directly shaped by

- the establishment of a fully integrated American military

- the success of the Treaty of Versailles

- the defeat of Nazi tyranny by the free nations of the world

- the success of the island-hopping campaign in the Pacific Theater of Operation during World War II

3. The sentiments in the excerpt were most directly shaped by

- the Monroe Doctrine

- technological advances in military armaments

- rejection of the collective-security provision in the League of Nations covenant

- the belief that the war was a fight for the survival of democracy

Primary Sources

Baumgarten, Harold. D-Day Survivor: An Autobiography . New York: Pelican, 2006.

Santoro, G. “Omaha the Hard Way: Conversation With Hal Baumgarten.” http://www.historynet.com/omaha-hard-way-conversation-hal-baumgarten.htm

Suggested Resources

Ambrose, Stephen E. D-Day June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II . New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994.

Atkinson, Rick. The Guns at Last Light: The War in Western Europe, 19441945 . New York: Henry Holt, 2013.

Beevor, Antony. D-Day: The Battle for Normandy . New York: Viking, 2009.

Caddick-Adams, Peter. Sand and Steel: The D-Day Invasion and the Liberation of France . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Chambers, John Whiteclay, ed. The Oxford Companion to American Military History . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1999.

D’Este, Carlo. Decision in Normandy . New York: Harper, 1994.

Hastings, Max. Overlord: D-Day and the Battle for Normandy . New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984.

Holland, James. Normandy ’44: D-Day and the Epic 77-Day Battle for France . New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2019.

Keegan, John. Six Armies in Normandy: From D-Day to the Liberation of Paris . New York: Viking, 1983.

Kershaw, Alex. The Bedford Boys: One American Town’s Ultimate D-Day Sacrifice . New York: Da Capo Press, 2003.

Kershaw, Alex. The First Wave: The D-Day Warriors Who Led the Way to Victory in World War II . New York: Dutton Caliber, 2019.

McManus, John C. The Dead and Those About to Die: D-Day: The Big Red One at Omaha Beach . New York: Dutton Caliber, 2014.

Ryan, Cornelius. The Longest Day: June 6, 1944 . Reprint. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994

Weinberg, Gerhard L. A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Related Content

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

In our resource history is presented through a series of narratives, primary sources, and point-counterpoint debates that invites students to participate in the ongoing conversation about the American experiment.

D-Day: The Role in World War II Research Paper

D-day is an important historical event that happened on June 6, 1944. During World War II, allied armies suffered significant losses, and D-day, also known as the Normandy landings, or Operation Overlord, resulted in terrible human losses. This invasion became one of the hugest amphibious military actions and demanded profound planning (History.com Editors, 2019). It is essential to examine facts about D-day to understand the scale of its significance in terms of World War II.

The preparations for this military operation were extensive and witty. Several months before D-day, the Allies made German soldiers think that Pas-de-Calais was the main aim, not Normandy (History.com Editors, 2019). Many techniques were used to conduct such a deception, including false weapons. Moreover, the operation was delayed by one day because of poor weather conditions. Indeed, after the meteorologist predicted weather improvement, General Dwight Eisenhower approved the process. He motivated his soldiers with vital speeches, which became legendary. More than five thousand ships and eleven thousand aircraft were mobilized during D-day (History.com Editors, 2019). About 156,000 allied troops conquered the Normandy territories by the end of June 6, 1944. Next week the Allies stormed countryside areas, facing German opposition.

By the end of 1944, Paris was released after the Allies approached the Seine River. German armies left France, which signalized the victory (History.com Editors, 2019). Indeed, the critical fact was a significant mental crash during the Normandy invasion. It prevented Adolf Hitler from creating his Eastern Front against the Soviet armies. The Allies decided to eliminate Nazi Germany; Adolf Hitler committed suicide a week before the decision, on April 30, 1945 (History.com Editors, 2019). D-Day became a significant event that influenced the pace of World War II. Undoubtedly, many people died and suffered severe injuries during the event; however, it became an essential part of history.

History.com Editors. (2019). D-Day . History.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, April 8). D-Day: The Role in World War II. https://ivypanda.com/essays/d-day-the-role-in-world-war-ii/

"D-Day: The Role in World War II." IvyPanda , 8 Apr. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/d-day-the-role-in-world-war-ii/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'D-Day: The Role in World War II'. 8 April.

IvyPanda . 2023. "D-Day: The Role in World War II." April 8, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/d-day-the-role-in-world-war-ii/.

1. IvyPanda . "D-Day: The Role in World War II." April 8, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/d-day-the-role-in-world-war-ii/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "D-Day: The Role in World War II." April 8, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/d-day-the-role-in-world-war-ii/.

- Comparison of Signalized Intersections and Roundabouts

- Invasion of Normandy in World War II

- The battle of Normandy

- Experience and Perspective Amphibious Operations

- War Movie Analysis and Reflection

- The European Theatre of Operations in WWII

- Fisherman's Wharf in San Francisco

- Intelligence, War and International Relations

- The Events and Importance of the Battle of Carentan

- Crowdfunding Project on Kickstarter

- The Second World War Choices Made in 1940

- The World War II Propaganda Techniques

- What Role Did India Play in the Second World War?

- Could the US Prevent the Start of World War II?

- World War Two and Its Ramifications

Search the Holocaust Encyclopedia

- Animated Map

- Discussion Question

- Media Essay

- Oral History

- Timeline Event

- Clear Selections

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Português do Brasil

Featured Content

Find topics of interest and explore encyclopedia content related to those topics

Find articles, photos, maps, films, and more listed alphabetically

For Teachers

Recommended resources and topics if you have limited time to teach about the Holocaust

Explore the ID Cards to learn more about personal experiences during the Holocaust

Timeline of Events

Explore a timeline of events that occurred before, during, and after the Holocaust.

- Introduction to the Holocaust

- Liberation of Nazi Camps

- Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

- Boycott of Jewish Businesses

- Axis Invasion of Yugoslavia

- Antisemitism

- How Many People did the Nazis Murder?

- The Rwanda Genocide

The D-Day invasion of Normandy, France, on June 6, 1944, was one of the most important military operations to the western Allies’ success during World War II. By the end of June, more than 850,000 US, British, and Canadian troops had come ashore on the beaches of Normandy.

Operation Overlord—commonly known as “D-Day”—was the largest amphibious invasion in history, deploying more than 160,000 Allied troops on air, land, and sea.

D-Day marked the beginning of the end of German rule in France. Two and a half months later, Paris was liberated.

As important as D-Day was to Allied victory, it came too late to change the course of the Holocaust. As the Allies were coming ashore, Hungarian Jews—the largest remaining community of Jews in occupied Europe—were being deported and murdered.

- World War II

- Allied powers

This content is available in the following languages

After the German conquest of France in 1940 , the opening of a second front in western Europe was a major aim of Allied strategy during World War II . Before the summer of 1944, the Soviet Red Army carried on the bulk of the Allied fighting in Europe. Western Allied troops, however, did not gain a footing on the European continent until July 1943 with the invasion of Sicily.

But it was the Allied landing in northern France in June of 1944 that ultimately ensured Allied victory over the Nazis.

On June 6 of that year, under the code name Operation “Overlord,” US, British, and Canadian troops crossed the English Channel and landed on the beaches of Normandy, France. Since then, June 6, 1944, has been known in World War II history as “D-Day.”

D-Day: Photographs

Operation "Overlord"

Operation “Overlord” was organized under the overall command of US General Dwight D. Eisenhower. On the ground, it was commanded by British General Bernard Montgomery. During the operation, Allied troops landed on five beaches on the coast of Normandy. The beaches were code named: Omaha, Gold, Juno, Sword, and Utah. On the night before the amphibious landings, more than 23,000 US, British, and Canadian paratroopers landed in France behind the German defensive lines by parachute and glider. The invasion forces numbered about 175,000 Allied troops and 50,000 vehicles. Some 5,000 naval craft and more than 11,500 aircraft supported the initial invasion.

At first, under the overall command of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel , the Germans had held the advantage in battle positioning. They had deployed five infantry divisions, one airborne division, and one tank division along the Normandy coast. However, the Allies had an overwhelming advantage in naval and air power. On D-Day alone, the Allies flew 14,000 sorties. In contrast, the German air force managed only 500 sorties. Moreover, a successful Allied deception plan had led the Germans to believe the point of the attack would be further north and east on the coast near Calais and the Belgian border. Deceived, the Germans moved only slowly to reinforce the Normandy defenses after the initial landing.

"'This is D-Day,’ the BBC announced at twelve. ‘This is the day.’ The invasion has begun...Is this really the beginning of the long-awaited liberation? The liberation we’ve all talked so much about, which still seems too good, too much of a fairy tale ever to come true? Will this year, 1944, bring us victory? We don’t know yet. But where there’s hope, there’s life. It fills us with fresh courage and makes us strong again.” — Anne Frank , diary entry June 6, 1944

By nightfall of June 6, 1944, some 100,000 Allied servicemen had come ashore . Despite Allied superiority, the Germans contained Allied troops in their slowly expanding beachhead for six weeks. The US 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions made the most difficult landing on Omaha Beach. Stiff German resistance here caused over 3,000 casualties before the Allied troops could establish their positions by the end of the first day. On D-Day itself, Allied troops suffered more than 10,000 casualties, with 4,400 confirmed dead. Specifically, British and Canadian forces suffered around 3,700 casualties; and US forces suffered about 6,600 casualties. German forces lost between 4,000 and 9,000 men.

D-Day: Historical Film Footage

On D-Day itself, the Allies landed 11 divisions on the French coast. Initially , they failed to reach their planned objective of linking the beachheads or driving inland to a distance of nine miles. On June 11, however, Allied troops overcame German resistance. They united the invasion beaches into one large beachhead.

On July 25, 1944, Allied troops broke out of the Normandy beachhead near the town of St. Lo. They began to pour into northern France. By mid-August, Allied troops encircled and destroyed much of the German army in Normandy in the Falaise pocket. Spearheaded by General George Patton's Third Army, the Allies then raced across France. On August 25, Free French forces liberated Pari s with Allied support. On September 11, 1944, US troops arrived in Luxembourg, which at the time was annexed to the German Reich. This meant that US troops had effectively crossed the German frontier.

D-Day and the Holocaust

D-Day was key to the overall Allied victory in World War II. However, this victory came too late in the war to make a significant difference in the fate of Europe’s Jews. More than five million had already been killed by D-Day.

As Allied troops stormed ashore in Northern France, the Nazis were deporting and murdering Hungarian Jews on a massive scale. The Jews of Hungary were the largest remaining Jewish community in occupied Europe at this time.

Despite the Allied victory during Operation “Overlord,” Jews would continue to be murdered right up until the end of the war.

Series: World War II

World War II in Europe

World War II: In Depth

World War II Dates and Timeline

The Holocaust and World War II: Key Dates

Axis Powers in World War II

Blitzkrieg (Lightning War)

Invasion of Poland, Fall 1939

German Invasion of Western Europe, May 1940

Allied Military Operations in North Africa

Invasion of the soviet union, june 1941.

World War II in Eastern Europe, 1942–1945

The Eastern Front: The German War against the Soviet Union

World War II in the Pacific

Pearl Harbor

Allied Military Advances in the West

Series: allied military advances in the west.

Hürtgen Forest

Battle of the bulge.

Capture of the Bridge at Remagen

The Rhine Crossings in World War II

Encircling the Ruhr

Switch series, critical thinking questions.

- Genocide often happens under cover of war. What was the relationship between the progress of the war and the mass murder of Europe’s Jews?

- How many Jews had been murdered by D-Day? What camps and killing centers were still in operation?

- When did Allied forces in the west begin to encounter concentration camps? When did Soviet forces encounter camps in Poland?

Thank you for supporting our work

We would like to thank Crown Family Philanthropies and the Abe and Ida Cooper Foundation for supporting the ongoing work to create content and resources for the Holocaust Encyclopedia. View the list of all donors .

- X (formerly Twitter)

Why D-Day Matters

While the invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, usually termed D-Day, did not end the war in Europe—that would take eleven more months—success on that day created a path to victory for the Allies. The stakes were so great, the impact so monumental, that this single day stands out in history.

Toward Which We Have Striven

The planning of d-day.

The largest land, sea, and air invasion ever attempted was years in the making. World War II in Europe began with the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany in September 1939. Britain and France declared war in response but could do little to help the Poles. In the spring of 1940, German leader Adolf Hitler staged successful invasions of Denmark, Norway, Belgium, Holland, and other nations. German armies then moved into France, rapidly breaking through border defenses and pinning much of the British and French armies against the English Channel. While Britain was able to evacuate many of those forces from the area around Dunkirk, it left Nazi Germany dominant on the continent of Europe.

Almost immediately, British leaders began envisioning ways to get back across the Channel in an amphibious assault, eventually code-named Operation Overlord. Understanding the threat such an invasion would pose, Hitler began to build formidable defenses along the entire Channel coast, which he called his “Atlantic Wall.”

In 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, formerly a partner. Also, by the end of that year, the United States entered the war after Japan (an ally of Germany) attacked the American base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The entry of the U.S. into the Alliance meant the scope of the planned cross-Channel invasion would grow. Soon American forces began arriving in England to train for the invasion.

At the Tehran Conference in November 1943, Allied leaders decided the cross-Channel invasion would occur in the spring of 1944 with American general Dwight Eisenhower as Supreme Allied Commander of the multinational operation. Forces from twelve Allied nations (most occupied by Nazi Germany) would take part. The invasion had to be the most intricately planned military operation in history. Such questions as where and when to land; how many soldiers, tanks, ships, and planes would be needed; what equipment each man had to carry; and the essential question of how to keep this a secret from the enemy were debated and planned. The final plan called for some 156,000 men to land on five beaches on the coast of Normandy: the Americans at Utah and Omaha in the west, and the British and Canadians at Gold, Juno, and Sword. They would be bolstered by parachute and glider landings and supported by some 5,000 ships and 11,000 airplanes.

Planners set the date of June 5, 1944, for the landings, but a storm that day meant it would be too cloudy to bombard German coastal defenses and too windy for men to disembark from landing craft. British meteorologist James Stagg advised General Eisenhower of a temporary break in the weather, clearer skies, and lighter winds, which would potentially allow the invasion to commence twenty-four hours later. With his assault, naval, and air commanders all saying “go,” Eisenhower gave the order.

Victorious Allies

The Eyes of the World Are Upon You

June 6, 1944.

In the early hours of June 6, under the cover of darkness, American and British paratroopers dropped into Normandy from more than 1,200 aircraft. Once daylight appeared, gliders brought in additional paratroopers. American airborne forces of the 82nd and 101st worked valiantly to achieve their inland objectives, including the capture of Sainte-Mere Eglise and securing key approaches to the Allied beachhead.

The largest naval bombardment ever seen began at 5:30 AM, lasting only forty minutes. American battleships supported by cruisers and destroyers and the British Royal Navy with a similar group of ships shelled gun emplacements and defensive positions around their designated beaches.

The sunrise on June 6 brought with it wave after wave of landing vessels, carrying the more than 150,000 American, British, Canadian, and French ground troops who stormed some fifty miles of coastline in Northern France, beaches fiercely defended by the Germans.

Strong currents pushed the Americans 2,000 yards south of Utah Beach, forcing them to march that distance back to the intended landing areas to seize German fortifications. They still secured Utah by day’s end.

The Germans were aware of the importance of the sector designated Omaha Beach, which the Allies would need to connect and secure the beachheads together, and made certain it was heavily defended. Fortifications and elevated terrain meant the American landing on Omaha would be the bloodiest that day.

The British secured Gold Beach with the help of artillery, tanks, and air support. Assuming Allied landing craft could not make it past the offshore rocks, the Germans did not defend Juno Beach as heavily. Canadian forces pushed the Germans out and secured Juno’s beachhead by mid-afternoon. Tasked with securing Sword Beach, the British were three miles from their intended objective at Caen by day’s end. Nightfall on D-Day found Allied forces past the German defenses on all five beachheads. Hitler’s vaunted Atlantic Wall lasted less than twenty-four hours.

Listen to the Historic Broadcast

A Dispatch from

Fifty years after D-Day, in 1994, Bruce Campbell bought an old cabin on Long Island. As Campbell began cleaning out the basement, he came across boxes containing what looked like movie film. He’d discovered 16 Amertapes and various parts of a Recordgraph machine.

Marching Together to Victory

Beyond overlord.

Many Allied soldiers would follow the D-Day forces into France, with the goal of breaking out of Normandy and pushing the Germans east. Allied forces found themselves bogged down in the infamous hedgerows of Normandy, walls of impenetrable vegetation that provided ideal defensive positions for the Germans and limited the Allies’ ability to move as quickly as hoped.

Frustrated with the failure of the British in the Caen sector to achieve a breakout, General Omar Bradley planned an American offensive, Operation Cobra, near Saint-Lô. If successful, the U.S. forces would be out of the dreaded hedgerows and able to maneuver rapidly. Cobra commenced on July 25 with a massive air assault against German positions. It worked, and soon the American mechanized army was on the move.

The success of Cobra is considered the end of the Normandy campaign and signaled the collapse of German defenses throughout most of France. Hastened by American landings on France’s Mediterranean coast beginning August 15 (Operation Dragoon), Allied forces by August 25 had liberated Paris. Soviet offenses from the east placed additional pressure on the Germans. Ultimate victory, the defeat of Nazi Germany, would only come after fierce fighting that lasted until the following May.

Frequently Asked Questions About D-Day

What does the d in d-day stand for.

D, which merely stands for day, is the designation used to indicate the start date of any American military operation. Military planners used plus and minus signs to designate days occurring before or after; two days before an operation commenced was indicated as D-2, three days after was D+3. An operation began on D Day and at H-Hour. While all American operations had a D-Day, the invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, is the best-known and goes down in history as such.

Why invade at Normandy?

There was enormous thought on both sides as to where the cross-Channel attack would take place. The most obvious location was in the Calais area, where the Channel is narrowest. But it was deemed too obvious. Attacking at Normandy increased the distance to travel and lengthened supply lines, but the element of surprise was considered worth the extra difficulty and risk.

What is the difference between Operation Overlord and Operation Neptune?

Operation Overlord was the code-name for the overall invasion of Normandy. Operation Neptune was the code-name for the seaborne landings and naval aspects.

How many men were killed on D-Day?

4,415: 2,502 Americans and 1,913 Allies from seven nations.

The Foundation’s necrology database is the most authoritative accounting of D-Day fallen anywhere in the world, but we know there are others. Precise record-keeping was not the priority in the heat of battle and dates were recorded incorrectly or not at all. When evidence suggests an individual was killed on June 6, 1944, our research team determines eligibility for inclusion on the Memorial wall.

Were women involved in the D-Day invasion? What about African Americans and Native Americans?

Women being ineligible for combat in 1944, no women landed on D-Day; although war correspondent Martha Gellhorn reportedly snuck onto a troop transport to cover the invasion. However, within two or three days American nurses were serving in Normandy; and the brave civilian women who acted within the French Resistance deserve recognition too.

African Americans were certainly present on D-Day, despite the racial segregation of the period. Most notable were the men of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion, which landed elements on both Utah and Omaha Beach. African Americans also acted with the quartermaster corps, as truck or bulldozer drivers, and as medics. Five African Americans are known to have given their lives on D-Day.

It is difficult to say how many Native Americans served on D-Day, because they were not always identified as such in records. But we know that members of the Comanche Tribe served as code talkers, using their native language as code unbreakable to the enemy. According to the Charles Shay Indian Memorial on Omaha Beach, about 175 American Indians invaded Omaha Beach. “Some were medics, others fought as seamen, scouts, snipers, radio operators, machine gunners, artillery gunners, combat engineers, or forward observers.”

Who were the “Bedford Boys?”

The term popularized by author Alex Kershaw’s 2003 book usually refers to soldiers from the community of Bedford, Virginia, serving in Company A, 116th Regiment who participated in the Normandy Invasion. Nineteen of those soldiers died on Omaha Beach and a twentieth Bedford native from Company F also died that day.

Why is the Memorial in Bedford?

The loss of the “Bedford Boys” is widely thought to be the highest per capita sacrifice made by any American community on D-Day. For that reason, Congress warranted the Memorial’s establishment in Bedford, Virginia, recognizing Bedford as emblematic of American homefront communities. Additionally, it is worth noting that approximately 100 other Bedford residents died during WWII in other battles and other theaters.

Is the Memorial part of the National Park Service? Does it receive government funding?

Though warranted by the United States Congress, the Memorial is not a National Park Service site. The National D-Day Memorial Foundation operates and maintains the site, with the educational mission of preserving the lessons and legacy of D-Day. The Memorial is not state or federally funded and relies on donor support. Visit our Ways to Support Us page to learn how you can support the Memorial.

Who designed and built the Memorial?

Byron Dickson – Architect

Coleman-Adams Construction – General Contractor

Jim Brothers, Matthew Kirby, Richard Pumphrey – Sculptors

Can my relative be recognized at the Memorial?

Only the names of those who died between 12:00 AM and 11:59 PM on June 6, 1944, while participating in the invasion of Normandy, are recorded on the Memorial wall. Families can honor loved ones with Memorial bricks or by purchasing a cherry tree or bench located on-site. Biographical information about Normandy veterans can be submitted to our Participant Program for inclusion in the research archive.

What is a Gold Star Family?

Gold Star Families are those American families who have lost a loved one in military service to our nation. The blue and gold star banner tradition began in World War I. A blue star indicates an active service member. A gold star denotes a service member who gave his or her life for their country.

On the west side of the Memorial grounds is a Gold Star Families Memorial Monument, a moving tribute to those families. Created by the late Hershel “Woody” Williams, the longest-surviving Medal of Honor recipient from WWII, Williams personally chose the National D-Day Memorial as the site of the first such monument in Virginia.

European journal of American studies

Home Issues 7-2 The Many Meanings of D-Day

The Many Meanings of D-Day

This essay investigates what D-Day has symbolized for Americans and how and why its meaning has changed over the past six decades. While the commemoration functions differently in U.S. domestic and foreign policies, in both cases it has been used to mark new beginnings. Ronald Reagan launched his “morning again in America” 1984 re-election campaign from the Pointe du Hoc, and the international commemorations on the Normandy beaches since 1990 have been occasions to display the changing face of Europe and the realignment of allies.

Index terms

Keywords: .

1 For Americans, June 6, 1944 “D-Day” has come to symbolize World War II, with commemorations at home and abroad. How did this date come to assume such significance and how have the commemorations changed over the 65 years since the Normandy landings? How does D-Day function in U.S. cultural memory and in domestic politics and foreign policy? This paper will look at some of the major trends in D-Day remembrances, particularly in international commemorations and D-Day’s meaning in U.S. and Allied foreign policy. Although war commemorations are ostensibly directed at reflecting on the hallowed past, the D-Day observances, particularly since the 1980s, have also marked new beginnings in both domestic and foreign policy.

2 As the invasion was taking place in June 1944, there was, of course, a great deal of coverage in the U.S. media. The events in Normandy, however, shared the June headlines with other simultaneous developments on the European front including the fall of Rome. 1

1. Early Years

3 The very first anniversary of the D-Day landings was marked on June 6, 1945 by a holiday for the Allied forces. In his message to the troops announcing the holiday General Eisenhower stated that “formal ceremonies would be avoided.” 2

4 By the time the invasion’s fifth anniversary rolled around in 1949 the day was marked by a “colorful but modest memorial service” at the beach. The U.S. was represented at the event by the military attaché and the naval attaché of the U.S. Embassy in Paris. A French naval guard, a local bugle corps and an honor guard from an American Legion Post in Paris all took part. A pair of young girls from the surrounding villages placed wreaths on the beach, and a U.S. Air Force Flying Fortresses passed over, firing rockets and dropping flowers. 3

5 The anniversaries of the early 1950s reflected the tenor of the times, evoking both the economic and military Cold War projects of the U.S. in Europe: the Marshall Plan and NATO. Barry Bingham, head of the Marshall Plan Mission in France, used the occasion of the 1950 D-Day commemoration ceremony to praise France’s postwar recovery efforts. 4 Held in the middle of the Korean War, the 1952 D-Day commemoration at Utah Beach proved an opportunity for General Matthew D. Ridgway, Supreme Commander Allied Forces in Europe and a D-Day veteran, to speak of U.S. purpose in the Cold War against “a new and more fearful totalitarianism.” He warned the Communist powers not to “underestimate our resolve to live as free men in our own territories….We will gather the strength we have pledged to one another and set it before our people and our lands as a protective shield until reason backed by strength halts further aggression….” Referring to both his status as a D-Day participant and his current role as military commander of NATO, Ridgway pledged: “The last time I came here, I came as one of thousands to wage war. This time I come to wage peace.” 5

6 The tenth anniversary of the D-Day landings found President Dwight Eisenhower, who as Commander of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) had led the Normandy invasion, strolling through a wheat field in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. 6 Eisenhower sent a statement to be read at the Utah Beach commemoration ceremony by the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. who was the President’s personal representative at the anniversary events. In contrast to the bellicose remarks of General Ridgway a few years earlier, Eisenhower in 1954 expressed “profound regret” that all of “the members of the Grand Alliance have not maintained in time of peace the spirit of that wartime union.” Eisenhower used this anniversary occasion to recall “my pleasant association with the outstanding Soviet Soldier, Marshall Zhukov, and the victorious meeting at the Elbe of the armies of the West and of the East.” 7 A decade later, in preparation for the twentieth anniversary of the D-Day landings, Eisenhower, no longer president, returned to the Normandy beaches in 1963 to film a D-Day TV special for CBS. 8

7 In between the tenth and twentieth anniversaries, U.S. domestic interest in the Normandy landings had been stoked by Cornelius Ryan’s 1959 best-seller The Longest Day and the 1962 Hollywood epic that Darryl F. Zanuck produced based on Ryan’s book. The film was also notable for giving separate attention to the contributions of the British and Canadian forces as well as those of the French Resistance. The German actions in Normandy were depicted without demonization. Leading German actors (speaking German) gave voice to the professional military’s criticism of Hitler’s leadership. This empathetic portrayal was an indication perhaps of West Germany’s position in the NATO alliance. Clocking in at 178 minutes and shot in black and white for a documentary feel, The Longest Day boasted a cast that was a Who’s-who of British and American male stars of the era: John Wayne, Henry Fonda, Robert Mitchum, Richard Burton, Peter Lawford, Sean Connery, Richard Beymer, Red Buttons, Eddie Albert, and teen heart-throbs Fabian, Paul Anka, Tommy Sands and Sal Mineo. This display of bold-face names served to undercut the film’s intended documentary effect as their presence constantly reminded the viewers that they were watching a Hollywood production. Critics pointed out that Zanuck’s attention to period detail in weapons, equipment and language did not carry through to a realistic depiction of combat death and casualties—a charge that could not be laid against Steven Spielberg for Saving Private Ryan a 1998 Hollywood D-Day block-buster . 9

8 In spite of this heightened public interest in D-Day, U.S. President Lyndon Johnson, absorbed in both his ambitious domestic agenda—including trying to secure passage of the Civil Rights Act-- and the Vietnam War, did not travel to Normandy for the twentieth anniversary. Instead he sent General Omar N. Bradley, one of the commanders of the 1944 landings. 10

9 For the twenty-fifth anniversary in 1969 President Richard Nixon, focused on Vietnam, issued a boilerplate proclamation, calling the Allied landings in 1944 “‘a historical landmark in the history of freedom.’” 11 When the time came for the thirtieth anniversary of D-Day in 1974, Nixon again was too preoccupied to travel to Normandy. Congress had already begun impeachment hearings against him on charges of obstruction of justice, abuse of power and contempt of Congress arising from the Watergate affair. Nixon would resign in August 1974, and Presidential attention for the rest of the 1970s was directed at the aftermath of Vietnam and at new crisis like those involving the U.S. economy, energy, and the seizing of the U.S. Embassy in Teheran. The moment for actively reinvigorating the memory of World War II had not yet arrived.

10 As the G-7 leaders 12 gathered in Paris for their meetings at Versailles in early June 1982, President Ronald Reagan made D-Day the focus of his radio broadcast to U.S. audiences on June 5. He also prepared taped remarks on D-Day for broadcast on French television. 13 Although the President himself did not travel to the landing sites in 1982, U.S. First Lady Nancy Reagan paid a three-hour visit to Normandy to mark the thirty-eighth anniversary of D-Day. 14 Accompanied by the Defense and Army attachés of the U.S. Embassy in Paris, she laid a wreath at the memorial statue in the U.S. cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer and made some brief remarks to a small crowd: “If my husband were here today, he would tell you how deeply he feels the responsibilities of peace and freedom. He would tell you how we can best insure that other young men on other beaches and other fields will not have to die. And I think he would tell you of his ideas for nuclear peace.” 15

2. “Morning Again in America”

11 Two years later on the fortieth anniversary of D-Day in June 1984 her husband President Ronald Reagan would get the chance to personally address those gathered to commemorate the Normandy invasion. But this time the crowd was no longer small. Speaking at the Ranger Monument at Pointe du Hoc at 1:20 p.m. (timed to coincide with the morning TV programs on the U.S. East Coast and designed as part of Reagan’s re-election campaign) President Reagan delivered his now-famous “boys of Pointe du Hoc” address to a television audience of millions as well as to the veterans and Allied leaders gathered on the Normandy coast. In remarks carefully crafted by Peggy Noonan, Reagan first paid tribute to the Ranger veterans, recreating dramatically their heroic deeds in scaling the cliffs: “They climbed, shot back, and held their footing. Soon, one by one, the Rangers pulled themselves over the top, and in seizing the firm land at the top of these cliffs, they began to seize back the continent of Europe. Two hundred and twenty-five came here. After two days of fighting, only ninety could still bear arms.” He went on to pay tribute to the Allies, mentioning by name “the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, Poland's 24th Lancers, the Royal Scots Fusiliers, the Screaming Eagles, the Yeomen of England's armored divisions, the forces of Free France, the Coast Guard's ‘Matchbox Fleet’ and you, the American Rangers.” Not leaving out Germany and Italy, Reagan spoke of the reconciliation with former enemies “all of whom had suffered so greatly. The United States did its part, creating the Marshall plan to help rebuild our allies and our former enemies. The Marshall plan led to the Atlantic alliance -- a great alliance that serves to this day as our shield for freedom, for prosperity, and for peace.” Toward the Russians, Reagan presented two faces. 16 First, he lamented: “Some liberated countries were lost. The great sadness of this loss echoes down to our own time in the streets of Warsaw, Prague, and East Berlin. Soviet troops that came to the center of this continent did not leave when peace came. They're still there, uninvited, unwanted, unyielding, almost 40 years after the war.” Then he added: “It's fitting to remember here the great losses also suffered by the Russian people during World War II: 20 million perished…. We look for some sign from the Soviet Union that they are willing to move forward, that they share our desire and love for peace, and that they will give up the ways of conquest.” After his remarks he unveiled two memorial plaques honoring the Rangers. 17

12 The Pointe du Hoc speech served as the opening salvo in Reagan’s “morning again in America” re-election campaign. Using snippets from this speech in a popular television advertisement, the campaign transformed a look back at a forty-year-old battle into a new beginning for the nation. 18

13 A few hours after the Pointe du Hoc speech Reagan gave another address on Omaha Beach, this time paying special tribute to the efforts of the French Resistance, directing his remarks at President Mitterrand, who had participated in the Resistance. “Your valiant struggle for France did so much to cripple the enemy and spur the advance of the armies of liberation. The French Forces of the Interior will forever personify courage and national spirit.” Reminding Americans and Europeans of the importance of postwar efforts like NATO, he concluded: “Our alliance, forged in the crucible of war, tempered and shaped by the realities of the postwar world, has succeeded. In Europe, the threat has been contained, the peace has been kept.” 19

14 Later that same day President Reagan joined President Mitterrand and other Allied leaders (Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, Queen Beatrix of The Netherlands, King Olav V of Norway, King Baudouin I of Belgium, Grand Duke Jean of Luxembourg, and Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau of Canada) at Utah Beach. Mitterrand’s remarks stressed reconciliation with Germany: “‘the adversaries of yesterday are reconciled and are building the Europe of freedom.’” 20 Chancellor Helmut Kohl had not been invited to the ceremonies, but the day’s events and speeches buttressed a NATO alliance that included (West) Germany.

15 This emphasis on the continuing importance of the NATO alliance was far from accidental. There are been widespread protests in Europe in 1984 over the installation of U.S. Cruise and Pershing missiles in accordance with a 1979 NATO decision. The “family portrait” of the assembled Allies on Utah Beach and the tribute to their absent member Germany sent a signal to publics on both sides of the Atlantic about the continuing commitment to joint defense of “the Europe of freedom.” The 1984 celebrations set a new standard for D-Day commemorations and established a pattern that would be followed (with variations) for the next twenty-five years. By looking at these variations in subsequent years we can monitor changes in transatlantic relations.

3. A New Europe

16 By the time of the fiftieth anniversary of D-Day the map of Europe had shifted once again. The Warsaw Pact had dissolved; Germany had reunited; Czechoslovakia had split; the Soviet Union was no more. In June 1994 leaders of all the countries that had participated in the invasion gathered at Normandy: Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, the UK and the U.S. and this year for the first time leaders of Poland and the Czech Republic and Slovakia—a visible symbol of the changed faced of Europe since 1989 and yet another new beginning for the continent. In addition the year marked a generational shift, with the U.S. represented in Normandy by President Clinton who had been born after the end of World War II.

- 22 Jeffrey Birnbaum, “Reporter’s Notebook: Clinton, Facing Comparison with Reagan’s D-Day Speech Rise (...)

17 Clinton, of course, had a hard act to follow given the iconic status that Reagan’s “boys of Pointe du Hoc” speech had attained over the past decade. He also had the disadvantage of never having served in the military and of having famously avoided serving in the Vietnam War. In a new wrinkle to D-Day celebrations, Clinton, along with Queen Elizabeth and other Allied leaders, sailed from Portsmouth, England to the French coast in a “massive flotilla” accompanied by Lancaster bombers to recreate and commemorate the 1944 invasion. 21 In France Clinton participated in four ceremonies marking the anniversary of the landings. In his address at the American cemetery he turned his seeming disadvantage of lack of WWII experience into an advantage as he stressed the ties between generations: “‘We are the children of your sacrifice,’” he told the veterans of D-Day. “‘The flame of your youth became freedom's lamp, and we see its light reflected in your faces still, and in the faces of your children and grandchildren…. We commit ourselves, as you did, to keep that lamp burning for those who will follow. You completed your mission here. But the mission of freedom goes on; the battle continues. The `longest day' is not yet over.’” 22

18 D-Day anniversaries were not only occasions for major political gatherings and speeches, but had also become important tourist attractions and income generators for Western Europe, especially France, with Normandy hotels and guest houses fully booked for early June. In 1994 France alone hosted more than 350 events commemorating the D-Day landings. Many specialized tours were designed for veterans and their families. The QE2 even offered a cruise to Cherbourg featuring 1940s big bands, Vera Lynn and Bob Hope. 23 Across the Channel, thousands of veterans and their families were also welcomed at anniversary events in England. 24

19 Ten years later for the sixtieth anniversary of D-Day President George W. Bush faced a double challenge: how to repair the Alliance after the visible rupture over the Iraq War and how to compete with the memory of Ronald Reagan, whose exquisitely timed death on June 5, 2004 insured that the Great Communicator’s 1984 D-Day speeches would be replayed prominently on June 6, making comparisons between the two presidents unavoidable. The attack on Iraq in 2003 had become a point of contention among NATO Allies, with France and Germany refusing to support the war. French President Chirac as host of the Normandy commemorations invited German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder to the commemorations held in Caen and Arromanche , the first time a German leader had been included in the celebrations. 25 Although Chirac’s predecessor Mitterrand had gone out of his way to emphasize conciliation with Germany in his remarks twenty years before, on the fiftieth anniversary in 1994 Chancellor Helmut Kohl had not been invited to attend any Normandy events. At the time Kohl remarked, “There was ‘no reason’ for a chancellor of Germany ‘to celebrate when others mark a battle in which tens of thousands of Germans met miserable deaths.’” Schröder declared that his invitation to the 2004 Normandy commemoration “meant that ‘Germany's long journey to the West has now been completed,’” 26 signaling a new beginning for German identity within the community of Western nations.

20 The 1944 Normandy invasion had been, of course, an attack on German forces occupying France, but Schröder had been allied with Chirac in opposing the 2003 Iraq War. Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi of Italy, who supported the Iraq War, on the other hand, was not invited to the 2004 celebrations. However, Tony Blair, Bush’s close ally in the Iraq War, was there along with Queen Elizabeth. President Vladimir Putin of Russia also attended-- another first. During the Cold War the Soviet Union had not been included in the Normandy celebrations, in spite of its contributions to the Allied victory in World War II. Leaders and royalty from Australia, Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Slovakia and New Zealand also participated in the sixtieth anniversary events.

- 27 Richard W. Stevenson, “In Normandy, Bush Honors Veterans of D-Day,” The New York Times, 6 June 200 (...)

21 President Bush addressed the gathered veterans and heads of state at the Normandy American Cemetery above Omaha Beach, with a speech that focused on recounting the events of 1944 and on paying tribute to those who had participated in the invasion. “Mr. Bush said those who faced the hail of German machine gun fire and artillery, some who made it up over the cliffs and some who did not, had served ‘the noblest of causes’ and would never be forgotten.” 27 He turned toward President Chirac to add “And America would do it again, for our friends.” After the speech Chirac warmly clasped Bush’s hand. 28

29 Richard W. Stevenson, “In Normandy, Bush Honors Veterans of D-Day,” New York Times, 6 June 2004.

22 Bush in his remarks also reminded the Allies present that the “nations that battled across the continent would become trusted partners in the cause of peace, and our great alliance of freedom is strong, and it is still needed today,” a not-so-subtle hint to the French about the need for solidarity in the War on Terror. At the same event President Chirac vowed that “France will ‘never forget what it owes to America, its friend forever.’” 29 Tom Hanks and Steven Spielberg, the star and director of Saving Private Ryan , were among the crowd—a mixing of real veterans with those who represented them in Hollywood.

4. A New Generation

- 30 Andrew Pierce, “Prince of Wales to attend 65 th D-Day Anniversary,” The Daily Telegraph, 2 June 200 (...)

23 In 2009 with the numbers of surviving WWII veterans drastically shrinking, heads of state again returned to Normandy to mark D-Day—the 65 th anniversary of the landings. If President Chirac had made history by inviting Chancellor Schröder and President Putin, President Sarkozy made headlines when it was learned that Queen Elizabeth had not been invited to the anniversary celebrations. French and British officials traded charges about where the blame lay and in the end, after intervention by the Obama administration, Prince Charles attended the Normandy commemoration along with Prime Minister Gordon Brown. 30 Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper also took part. The generational shift first evident in 1994 was now complete. With the absence of Queen Elizabeth, all the Allied leaders taking part in the ceremonies had been born after World War II and had no direct personal memories to contribute. A fresh generation had assumed command, but continued to honor the past while celebrating the new. President Obama “invoked his deceased grandfather, ‘who arrived on this beach six weeks after D-Day and marched across Europe in Patton’s Army.’ And he introduced his great-uncle, Charles Payne, who fought in Germany and traveled here from Chicago.” 31 More than had his predecessors Obama also paid extensive tribute to America’s World War II home front “On farms and in factories millions of men and women worked three shifts a day, month after month, year after year. Trucks and tanks came from plants in Michigan and Indiana, New York and Illinois. Bombers and fighter planes rolled off assembly lines in Ohio and Kansas, where my grandmother did her part as an inspector.” 32 With President Sarkozy beaming on screen behind President Obama throughout the U.S. President’s remarks, the 2009 showcased a visibly warmer Franco-American relationship than had been on display five years earlier. In his own remarks, Sarkozy noted: “The great totalitarian systems of the 20th century have been defeated. The threats that loom over the future of humanity today are of a different kind, but they are no less serious.” 33 British Prime Minister Gordon Brown was so dazzled to be in the presence of the new American president that he made the Freudian slip of referring to Omaha Beach as “Obama Beach.” 34

24 Placing himself in the tradition that had started with President Reagan, Obama acknowledged, “I’m not the first American President to come and mark this anniversary, and I likely will not be the last.” 35 Over the twenty-five years since the invention of the Normandy “summits,” these events have become useful indicators of the state of the transatlantic relationship as well as of intra-European alignments. As the number of WWII veterans decreases to the point of elimination and the ties of the participating Allied leaders to the events become ever more attenuated, the meanings of D-Day become more about the present than the past. But looking back at even the early celebrations of the 1950s where the Marshall Plan and NATO were showcased we see that this has always been the case. The D-Day commemorations simultaneously honored the past while marking new beginnings in domestic politics and transatlantic relations.

1 Marianna Torgovnick, The War Complex: World War II in Our Time (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005) 23. Torgovnick also points out (pp. 40-41) that the total U.S. casualty figures for D-Day were 3581, 2403 of whom were killed. These numbers are much lower than those for some other WWII battles that have not acquired D-Day’s iconic status.

2 “D-Day Anniversary to be holiday for troops,” The New York Times , 3 June 1945, 2.

3 “Normandy Marks D-Day Anniversary,” The New York Times , 6 June 1949, 1.

4 “Recovery in France is Hailed,” The New York Times, 6 June 1950, 2.

5 “Reds Warned by Ridgway to Avoid War,” Washington Post , 7 1952, 3.

6 “Eisenhower Day Serene,” The New York Times, 6 June 1954, 30.

7 “Eisenhower Cites D-Day Solidarity,” New York Times, 6 June 1954, 30.

8 Val Adams, “Eisenhower going to Normandy to film D-Day program,” The New York Times, 15July . 1963, 43.

9 Robert Brent Toplin, “Hollywood’s D-Day from the Perspective of the 1960s and 1990s,” in: Peter C. Rollins and John E. O’Connor, eds. , Why We Fought: America’s Wars in Film and History (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2008) 306.

10 “British Ceremonies on Observances of 20 th D-Day Anniversary,” Washington Post , 4 June 1964, A8.

11 “D-Day Noted,” The New York Times, 1 June1969, 34.

12 The G-7, of course, included nations that fought on both sides of WWII: U.S., France, Britain and Canada representing the Allied forces on D-Day and Germany, Italy and Japan the Axis Powers in WWII.

13 Douglas Brinkley, The Boys of Pointe de Hoc: Ronald Reagan, D-Day and the U.S. Army 2 nd Ranger Battalion (New York: HarperCollins, 2005) 4-5

14 Nancy Reagan had received much negative criticism during the first year of the Reagan presidency for wearing designer dresses and spending large sums redecorating the White House (including purchasing a new china service) during a recession. The D-Day program as well as her visit to the National Institute for Blind Youth in Paris would serve to polish the First Lady’s public image and divert the focus from fashion during the Reagans’ time in France.

15 Enid Nemy, “Mrs. Reagan Visits U.S. Cemetery in Normandy on D-Day Anniversary,” The New York Times, 7 June 1982, D7.

16 These two approaches towards the Soviet Union reflect an internal administration debate over the address. See Brinkley, 156.

17 URL: http://www.reagan.utexas.edu/archives/speeches/1984/60684a.htm (accessed 3/20/2010)

18 Gil Troy, Morning in America: How Ronald Reagan Invented the 1980s (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005) 161.

19 URL: http://www.reagan.utexas.edu/archives/speeches/1984/60684b.htm (accessed 3/20/2010)

20 John Vinocur, “Mitterrand Stresses Conciliation,: New York Times , 7 June 1984, A12.

21 William Tuohy, “Allies Sail for D-Day plus 50,” Los Angeles Times, 6June 1994.

22 Jeffrey Birnbaum, “Reporter’s Notebook: Clinton, Facing Comparison with Reagan’s D-Day Speech Rises to occasion,” The Wall Street Journal, 7 June 1994, A16.

23 Mary Blume, “Normandy’s 50 th Anniversary Invasion,” The New York Times , 22 January 1994.

24 William Schmidt, “The D-Day Tour: Reminiscences,” The New York Times , 4 June 1994.

25 Schröder, however, was not present for President Bush's address at the American Cemetery.

26 Richard Bernstein, “Europa--So far, only silence for a remarkable visit,” The New York Times, 28 May 2004.

27 Richard W. Stevenson, “In Normandy, Bush Honors Veterans of D-Day,” The New York Times, 6 June 2004.

28 Carl M. Cannon, “Obama in Good Company on D-Day,” Politics Daily URL:

http://www.politicsdaily.com/2009/06/06/obama-in-good-company-on-d-day/ (accessed 3/20/2010)

30 Andrew Pierce, “Prince of Wales to attend 65 th D-Day Anniversary,” The Daily Telegraph, 2 June 2009.

31 Jeff Zeleny, “Obama Hails D-Day Heroes at Normandy,” The New York Times, 6 June 2009.

32 URL: http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-d-day-65th-anniversary-ceremony (accessed 3/21/2010)

33 Jeff Zeleny, “Obama Hails D-Day Heroes at Normandy,” The New York Times, 6 June 2009.

35 URL: http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-d-day-65th-anniversary-ceremony (accessed 3/21/2010)

Electronic reference

Kate Delaney , “The Many Meanings of D-Day” , European journal of American studies [Online], 7-2 | 2012, document 13, Online since 29 March 2012 , connection on 23 April 2024 . URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/9544; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.9544

About the author

Kate delaney.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The text only may be used under licence CC BY-NC 4.0 . All other elements (illustrations, imported files) are “All rights reserved”, unless otherwise stated.

- Cited Names

Full text issues

- 19-1 | 2024 Special Issue: Figurations of Interspecies Harmony in North American Literature and Culture

- 18-4 | 2023 Special Issue: Memory, Identity, Belonging: Narratives of Eastern and Central European Presence in North America

- 18-3 | 2023 Special Issue: Obsessions in Melville and Hawthorne

- 18-2 | 2023 Summer 2023

- 18-1 | 2023 Special Issue: Hamilton and the Poetics of America

- 17-4 | 2022 The Boredoms of Late Modernity

- 17-3 | 2022 Special Issue: Louisa May Alcott and Love: A European Seminar in Rome

- 17-2 | 2022 Summer 2022

- 17-1 | 2022 The Greek War of Independence and the United States: Narratives of Myth and Reality

- 16-4 | 2021 The American Neuronovel (2009-2021)

- 16-3 | 2021 Special Issue: Video Games and/in American Studies: Politics, Popular Culture, and Populism

- 16-2 | 2021 Summer 2021

- 16-1 | 2021 Spring 2021

- 15-4 | 2020 Special Issue: Contagion and Conviction: Rumor and Gossip in American Culture

- 15-3 | 2020 Special Issue: Media Agoras: Islamophobia and Inter/Multimedial Dissensus

- 15-2 | 2020 Summer 2020

- 15-1 | 2020 Special Issue: Truth or Post-Truth? Philosophy, American Studies, and Current Perspectives in Pragmatism and Hermeneutics

- 14-4 | 2019 Special Issue: Spectacle and Spectatorship in American Culture

- 14-3 | 2019 Special Issue: Harriet Prescott Spofford: The Home, the Nation, and the Wilderness

- 14-2 | 2019 Summer 2019

- 14-1 | 2019 Special Issue: Race Matters: 1968 as Living History in the Black Freedom Struggle

- 13-4 | 2018 Special Issue: Envisioning Justice: Mediating the Question of Rights in American Visual Culture

- 13-3 | 2018 Special Issue: America to Poland: Cultural Transfers and Adaptations

- 13-2 | 2018 Summer 2018

- 13-1 | 2018 Special Issue: Animals on American Television

- 12-4 | 2017 Special Issue: Sound and Vision: Intermediality and American Music

- 12-3 | 2017 Special Issue of the European Journal of American Studies: Cormac McCarthy Between Worlds

- 12-2 | 2017 Summer 2017, including Special Issue: Popularizing Politics: The 2016 U.S. Presidential Election

- 12-1 | 2017 Spring 2017: Special Issue - Eleanor Roosevelt and Diplomacy in the Public Interest

- 11-3 | 2017 Special Issue: Re-Queering The Nation: America’s Queer Crisis

- 11-2 | 2016 Summer 2016

- 11-1 | 2016 Special Issue: Intimate Frictions: History and Literature in the United States from the 19th to the 21st Century

- 10-3 | 2015 Special Double Issue: The City

- 10-2 | 2015 Summer 2015, including Special Issue: (Re)visioning America in the Graphic Novel

- 10-1 | 2015 Special Issue: Women in the USA

- 9-3 | 2014 Special Issue: Transnational Approaches to North American Regionalism

- 9-2 | 2014 Summer 2014

- 9-1 | 2014 Spring 2014

- 8-1 | 2013 Spring 2013

- 7-2 | 2012 Special Issue: Wars and New Beginnings in American History

- 7-1 | 2012 Spring 2012

- 6-3 | 2011 Special Issue: Postfrontier Writing

- 6-2 | 2011 Special Issue: Oslo Conference

- 6-1 | 2011 Spring 2011

- 5-4 | 2010 Special Issue: Film

- 5-3 | 2010 Summer 2010

- 5-2 | 2010 Special Issue: The North-West Pacific in the 18th and 19th Centuries

- 5-1 | 2010 Spring 2010

- 4-3 | 2009 Special Issue: Immigration

- 4-2 | 2009 Autumn 2009

- 4-1 | 2009 Spring 2009

- 3-3 | 2008 Autumn 2008

- 3-2 | 2008 Special Issue: May 68

- 3-1 | 2008 Spring 2008

- 2-2 | 2007 Autumn 2007

- 2-1 | 2007 Spring 2007

- 1-1 | 2006 Spring 2006

Electronic supplements

- Book reviews

The Journal

- What is EJAS ?

- Editorial Committee

- Instructions for Contributors

- Book Reviews Information

- Publication Ethics and Malpractice Statement

Information

- Website credits

- Publishing policies

Newsletters

- OpenEdition Newsletter

In collaboration with

Electronic ISSN 1991-9336

Read detailed presentation

Site map – Contact us – Website credits – Syndication

Privacy Policy – About Cookies – Report a problem

OpenEdition Journals member – Published with Lodel – Administration only