Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Pathophysiology and clinical presentation – correct diagnosis

Image Reference: https://blog.ekincare.com/2018/06/29/diagnosis-of-hypertension/

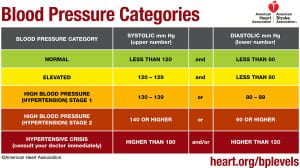

Hypertension or high blood pressure, is when an individual has consistently high arterial blood pressure, also known as the force with which blood flows through a person’s blood vessels (McCance & Huether, 2019). A normal blood pressure reading is a systolic (upper) number lower than 120 mmHg and a diastolic (lower) number that is lower than 80 mmHg (American Heart Association, 2017). Elevated blood pressure is when the systolic (upper) number is 120-129 mmHg with a normal diastolic (lower) number (American Heart Association, 2017). Stage one high blood pressure or hypertension is when the systolic (upper) number is between 130 mmHg and 139 mmHg and the diastolic (lower) number is between 80 and 89 mmHg (American Heart Association, 2017). The second stage of hypertension or high blood pressure is when the systolic (upper) number is 140 mmHg or higher and the diastolic (lower) number is 90 mmHg or higher (American Heart Association, 2017).

For someone to be diagnosed with hypertension their blood pressure measurements have to be taken two separate times that are at least two minutes apart, with the person seated, arm supported at heart level, with the person having rested for at least five minutes, and they should not have been smoking or drank any caffeine in the last 30 minutes (McCance & Huether, 2019). For hypertension to be diagnosed the diastolic and systolic numbers of the two readings are averaged and that measurement are found to be high according to the numbers above (McCance & Huether, 2019). Hypertension is often called a silent disease because in its early stages, there are commonly no other clinical manifestations besides high blood pressure measurements (McCance & Huether, 2019).

Hypertension is thought to be caused by both genetic and environmental factors (McCance & Huether, 2019). Genetic variations that cause the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) or the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) to be overactive predispose a person to hypertension (McCance & Huether, 2019). Additionally, genetic modifications in the function of renal sodium excretion, sensitivity to insulin, and sodium and/or calcium transport can also contribute to an increased risk for hypertension (McCance & Huether, 2019). Some environmental factors that increase the risk for hypertension include diet, exercise, and smoking (McCance & Huether, 2019).

There are two mechanisms by which blood pressure can be increased: an increase in vascular resistance, an increase in cardiac output, or both (McCance & Huether, 2019). Cardiac output increases when stroke volume or heart rate increases and vascular resistance is increased by vasoconstriction or when the blood becomes thicker (McCance & Huether, 2019). Many pathophysiologic processes are involved in facilitating the maintenance of these mechanisms.

The renal excretion of sodium is one of these processes. Blood volume increases when the renal system excretes less salt due to water retention, thus increasing stroke volume and consequently blood pressure (McCance & Huether, 2019). When this system functions normally , the kidneys excrete the appropriate amount of salt to maintain, but not increase blood pressure. Those with hypertension are more likely to secrete less sodium in their urine at any given blood pressure (McCance & Huether, 2019).

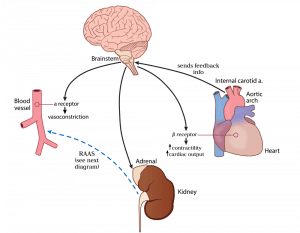

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) also helps modulate blood pressure by stimulating cardiac contractility and prompting vasoconstriction (McCance & Huether, 2019). It does so by controlling the release of epinephrine and norepinephrine which can bind to either alpha 1 receptors that reside on peripheral blood vessels or beta 1 receptors that reside on cardiac tissue (McCance & Huether, 2019). When this system functions normally , these catecholamines are released in the appropriate amount and interact with their receptors properly. In those with hypertension, there may be an increase in production of these catecholamines or their receptors may be especially reactive (McCance & Huether, 2019). This increased SNS activity triggers the heart rate to increase when affecting the beta 1 receptors and peripheral vasoconstriction when affecting the alpha 1 receptors (McCance & Huether, 2019). Both of these functions raise blood pressure (McCance & Huether, 2019).

There is also a connection between the sympathetic nervous system and kidney function. SNS activity triggers the release of renin, increases the amount of sodium that is reabsorbed, and lowers blood flow to the kidneys (McCance & Huether, 2019).

Image Reference: https://hasshe.com/vasodilation-nicotine-5c148fe58719620724c2bbfa/

Hypertension can be affected by inflammation (McCance & Huether, 2019). Injury to endothelial cells, or the cells that line the inside of blood vessels, along with lack of good blood supply to tissues in the body can trigger the immune system to release substances which directly impact the actions of the blood vessels (McCance & Huether, 2019). In a normal short-term injury , the appropriate substances (vasoactive cytokines) are released and help to heal the injured cite without causing overall harm to the body (McCance & Huether, 2019). When an injury to endothelial cells lasts a long time or becomes chronic, the cytokines can cause permanent damage resulting in a change in structure that prevents cells from functioning normally (McCance & Huether, 2019). This permanent change often leads to decreased production of vasodilators, or substances that the body produces to relax the blood vessels (nitric oxide) and an increased production of vasoconstrictors, or substances that the body produces to tighten blood vessels and increase blood pressure (McCance & Huether, 2019). This combination of events leads to an overall increase in blood pressure (McCance & Huether, 2019).

Insulin resistance is commonly associated with hypertension (McCance & Huether, 2019). Insulin resistance occurs when the body has a decreased response to insulin (McCance & Huether, 2019). Insulin is a hormone which normally acts in the body to stabilize blood sugar levels, and in doing so, interacts appropriately with other substances in the body to maintain a normal balance of vasodilators, salt and water (McCance & Huether, 2019). When someone is insulin resistant, there is an associated decrease in release of vasodilators (substances that decrease blood pressure) by endothelial cells (McCance & Huether, 2019). Insulin resistance impacts kidney function which leads to salt and water retention (McCance & Huether, 2019). Overactivity of the SNS and RAAS is also common in patients with insulin resistance (McCance & Huether, 2019). In some patients with diabetes, effective management of blood sugar levels can decrease blood pressure (McCance & Huether, 2019).

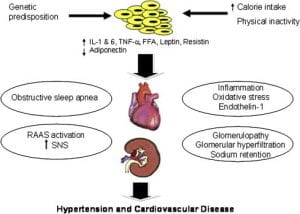

Obesity can have a major impact on hypertension (McCance & Huether, 2019). Obesity is associated with increased inflammation, activation of the RAAS and SNS, insulin resistance, as well as kidney and endothelial cell dysfunction (McCance & Huether, 2019). All these phenomena, as discussed above on this page, cause blood pressure levels to rise (McCance & Huether, 2019). Obesity causes changes in the fat tissue’s secretion of adipokines (McCance & Huether, 2019). Normally, adipokines are substances released by fat cells that act to regulate the actions of the fat cells and the tissues which the cells make up (McCance & Huether, 2019). When an individual is obese, there is an associated resistance to the action of an adipokine called leptin (McCance & Huether, 2019). In most individuals without obesity, leptin acts in the fat tissue to reduce the overall weight and fat content in a person (McCance & Huether, 2019). Under normal circumstances, the use of leptin by fat cells leads to its uptake from the blood into cells. In obese individuals, the decreased use of leptin by fat cells leads to an increase in the amount of leptin left circulating in the blood (McCance & Huether, 2019). This increase in leptin levels in the blood cause an increase in SNS activity and affect the kidneys in such a way that leads to less filtering of sodium out of the body (McCance & Huether, 2019).

Image Reference:

Kurukulasuriya, lr., md, stas, s., md, lastra, g., md, manrique, c., md and sowers, j.r., md. (1 september 2011). hypertension in obesity [diagram]. retrieved from: https://www-clinicalkey-com.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/#/content/playcontent/1-s2.0-s0025712511000629returnurl=https:%2f%2flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2fretrieve%2fpii%2fs0025712511000629%3fshowall%3dtrue&referrer=.

Levels of adiponectin, a protein made by fat tissues, are reduced in obese individuals (McCance & Huether, 2019). This lack of a normal adiponectin level is associated with insulin resistance, decreased nitric oxide (a vasodilator that decreases blood pressure), and an increased activation of the SNS and RAAS (McCance & Huether, 2019). These factors lead to overall constriction of the blood vessels, retention of excess water and salt in the body, and kidney dysfunction (McCance & Huether, 2019). All of these lead to a rise in blood pressure (McCance & Huether, 2019).

Secondary hypertension is when high blood pressure is caused by another disease or medication (McCance & Huether, 2019). Primary hypertension is caused by a combination of one or more factors explained above. Some things that can cause secondary hypertension include kidney disease, tumors associated with the adrenal gland, and medications such as oral contraceptives, antihistamines and corticosteroids (McCance & Huether, 2019) . The cause can be identified and treated or removed to lower blood pressure (McCance & Huether, 2019) .

Create Free Account or

- Acute Coronary Syndromes

- Anticoagulation Management

- Arrhythmias and Clinical EP

- Cardiac Surgery

- Cardio-Oncology

- Cardiovascular Care Team

- Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology

- COVID-19 Hub

- Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease

- Dyslipidemia

- Geriatric Cardiology

- Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies

- Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention

- Noninvasive Imaging

- Pericardial Disease

- Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism

- Sports and Exercise Cardiology

- Stable Ischemic Heart Disease

- Valvular Heart Disease

- Vascular Medicine

- Clinical Updates & Discoveries

- Advocacy & Policy

- Perspectives & Analysis

- Meeting Coverage

- ACC Member Publications

- ACC Podcasts

- View All Cardiology Updates

- Earn Credit

- View the Education Catalog

- ACC Anywhere: The Cardiology Video Library

- CardioSource Plus for Institutions and Practices

- ECG Drill and Practice

- Heart Songs

- Nuclear Cardiology

- Online Courses

- Collaborative Maintenance Pathway (CMP)

- Understanding MOC

- Image and Slide Gallery

- Annual Scientific Session and Related Events

- Chapter Meetings

- Live Meetings

- Live Meetings - International

- Webinars - Live

- Webinars - OnDemand

- Certificates and Certifications

- ACC Accreditation Services

- ACC Quality Improvement for Institutions Program

- CardioSmart

- National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR)

- Advocacy at the ACC

- Cardiology as a Career Path

- Cardiology Careers

- Cardiovascular Buyers Guide

- Clinical Solutions

- Clinician Well-Being Portal

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Infographics

- Innovation Program

- Mobile and Web Apps

Slide Set | 2017 Guideline For the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults (Updated May 2018)

Download PowerPoint File

Date: May 07, 2018

You must be logged in to save to your library.

Jacc journals on acc.org.

- JACC: Advances

- JACC: Basic to Translational Science

- JACC: CardioOncology

- JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging

- JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions

- JACC: Case Reports

- JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology

- JACC: Heart Failure

- Current Members

- Campaign for the Future

- Become a Member

- Renew Your Membership

- Member Benefits and Resources

- Member Sections

- ACC Member Directory

- ACC Innovation Program

- Our Strategic Direction

- Our History

- Our Bylaws and Code of Ethics

- Leadership and Governance

- Annual Report

- Industry Relations

- Support the ACC

- Jobs at the ACC

- Press Releases

- Social Media

- Book Our Conference Center

Clinical Topics

- Chronic Angina

- Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology

- Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease

- Hypertriglyceridemia

- Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention

- Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism

Latest in Cardiology

Education and meetings.

- Online Learning Catalog

- Products and Resources

- Annual Scientific Session

Tools and Practice Support

- Quality Improvement for Institutions

- Accreditation Services

- Practice Solutions

Heart House

- 2400 N St. NW

- Washington , DC 20037

- Email: [email protected]

- Phone: 1-202-375-6000

- Toll Free: 1-800-253-4636

- Fax: 1-202-375-6842

- Media Center

- ACC.org Quick Start Guide

- Advertising & Sponsorship Policy

- Clinical Content Disclaimer

- Editorial Board

- Privacy Policy

- Registered User Agreement

- Terms of Service

- Cookie Policy

© 2024 American College of Cardiology Foundation. All rights reserved.

Pharmacology of Hypertension

Jul 22, 2014

710 likes | 1.64k Views

Pharmacology of Hypertension. Vicki Groo , Pharm.d . Clinical Associate Professor Clinical pharmacist, heart center. [email protected] 413-0928. objectives. Classify hypertension and define treatment goals

Share Presentation

- recurrent stroke prevention

- additional drugs

- h20 retention

- ace inhibitors

- heart failure

- renin ace angiotensinogen angiotensin

Presentation Transcript

Pharmacology of Hypertension Vicki Groo, Pharm.d. Clinical Associate Professor Clinical pharmacist, heart center [email protected] 413-0928

objectives • Classify hypertension and define treatment goals • Be able to describe the pharmacology of oral antihypertensives with considerations in drug choice and compelling indications • Be able to describe the pharmacology of intravenous antihypertensives used in the treatment of hypertensive emergency

CLASSIFICATION **Adults (18 yo) **Avg of 2 readings, 2 mins apart, on 2 occasions Secondary HTN only accounts for 5-10% of population JAMA 2003;289:2560-2572

epidemiology • 31% of US population with HTN • 30% of US population with pre-HTN • Present in: • 69% of patients who present with 1st MI • 77% of patients who present with 1st stroke • 74% of patients with heart failure • Only 47% have BP under control • http://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/facts.htm

National Health & Nutrition Examination Survey 2007-2008 81% 73% 50%

TREATMENT GOALS JNC-7 • REDUCE MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY • Measurable goal: • Prehypertension: <120/80 • HTN w/ diabetes or renal disease: <130/80 • Others: <140/90 • Minimize/ control other CV risk factors • Reduce/ minimize adverse drug effects JAMA 2003;289:2560-2572

AHA BP targets 2007: • For prevention and management of ischemic heart disease: *Don’t worry about learning these for now. They may change Circulation 2007:115:2761-88

Without Compelling Indications With Compelling Indications Drug(s) for the compelling indications Other antihypertensive drugs (diuretics, ACEI, ARB, BB, CCB) as needed. Stage 1 Hypertension(SBP 140–159 or DBP 90–99 mmHg) Thiazide-type diuretics for most. May consider ACEI, ARB, BB, CCB, or combination. Stage 2 Hypertension(SBP >160 or DBP >100 mmHg) 2-drug combination for most (usually thiazide-type diuretic and ACEI, or ARB, or BB, or CCB) Not at Goal Blood Pressure Optimize dosages or add additional drugs until goal blood pressure is achieved.Consider consultation with hypertension specialist. Algorithm for Treatment of Hypertension Lifestyle Modifications Not at Goal Blood Pressure (<140/90 mmHg) (<130/80 mmHg for those with diabetes or chronic kidney disease) Initial Drug Choices JNC VII JAMA 2003;289:2560-2572

Drug Therapy Considerations • Clinical trial data • Over 2/3 of patients will require ≥2 drugs • Cost/ adverse effects • JAMA 2003;289:2560-2572

Limit salt intake Physical activity Lifestyle Modifications DASH eating Plan Lose weight Limit alcohol intake

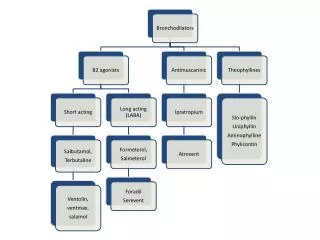

Pharmacology of Antihypertensives • Diuretics: • Deplete sodium thereby decreasing blood volume • Agents that block production or action of angiotensin • Reduce peripheral vascular resistance • Potentially ↓ blood volume • Sympathoplegic agents: • ↓ peripheral vascular resistance • Inhibit cardiac function • ↑ venous pooling in capacitance vessels • Direct vasodilators: • Relax vascular smooth muscle, thus dilating resistance vessels

Diuretic moa

Diuretic Comparison P = 0.054 and 0.009 for 24 hr and pm BP respectively Indapamide Hypertension 2004;43:4-9,

Diuretic Considerations Goodman and Gilmans: The Pharmacologic Basis of Therapeutic 12th edition: http://www.accesspharmacy.com

diuretics • Compelling Indications: • Heart Failure • High CAD risk • Diabetes • Recurrent Stroke Prevention • Monitoring • Electrolytes after initiation or dose increases • Every 6-12 months • K sparing, every 3 months if also on RAAS inhibitor • Side Effects • Increase glucose • Increase uric acid— precipitate gout • dehydration— orthostatic hypotension • Spironolactone— gynecomastia

Mechanism of Action

ACE Inhibitors ARBs * generic Combining with thiazide usually more effective than dose increase • Direct Renin Inhibitors • Aliskiren(Tekturna) • 150-300 mg/day • As effective as ACE or ARB in HTN * Dual elimination: liver & kidney Goodman and Gilmans: The Pharmacologic Basis of Therapeutic 12th edition: http://www.accesspharmacy.com

ACE Inhibitors and ARB • Compelling Indications • Systolic Heart Failure • DM • CKD with Proteinuria • CAD • Monitoring • 1-2 weeks after initiation or dose change for K & Cr • Every 6 months on stable doses • Side Effects • Dry Cough Switch to ARB • Angioedema: ARB likely okay, consider severity • Hyperkalemia: supplements, diet, worsening renal fxn • Combining RAAS inhibitors is generally not recommended • No added benefit CV or renal outcomes / Increased toxicity • ACE or ARB + aldosterone antagonist is the exception • Avoid in Pregnancy

Beta Blockers • MOA: Sympatholytic ↓ HR and CO / ↓ release of renin Avoid sudden discontinuation Rebound HTN d/t up regulation of ᵦ receptors Goodman and Gilmans: The Pharmacologic Basis of Therapeutic 12th edition: http://www.accesspharmacy.com

Beta Blockers • Compelling Indications • CAD • Systolic Heart Failure • Monitoring • ECG if bradycardic- AV block • Avoid combining with other AV nodal blocking agents • Side Effects • Bronchoconstriction—Reactive Airway Disease • Choose B1 selective agent and keep at lower doses • Metabolic—↓HDL, ↑ LDL and triglycerides • Diabetes—↓ insulin sensitivity • Mask symptoms of hypoglycemia, delay recovery • Carvedilol may have advantage as it ↑’s insulin sensitivity • Peripheral Vascular Disease—↑ symptoms, use B1 selective • Depression—Choose agent with low lipid solubility • Fatigue

Calcium channel blockers • http://www.accesspharmacy.com/content.aspx?aID=6543820 • http://www.drugdevelopment-technology.com/projects/istaroxime/istaroxime4.html

CCB Considerations ^ Do not use short acting agents in treatment of HTN # Do not combine with beta-blockers: increased risk of bradycardia Doses provided in DrDiDomenico’s lecture on angina Goodman and Gilmans: The Pharmacologic Basis of Therapeutic 12th edition: http://www.accesspharmacy.com

Calcium channel blockers • Compelling Indications • High CAD risk • Diabetes • Monitoring / Side Effects • Dihydropyridine (DHP) • peripheral edema • reflex tachycardia • dizziness • Non DHP • Bradycardia • Contra-indicated in heart failure • Constipation (especially verapamil)

Vasodilators: alpha-1 blockers Doxazosin: start 1 mg daily: max 8 mg daily Prazosin: start 1 mg bid-tid: max 15 mg/day Terazosin: start 1 mg qhs: max 20 mg/day http://cvpharmacology.com/vasodilator/alpha.htm

Vasodilators: alpha-1 blockers • Compelling Indications: None • Second line therapy • Also used to treat BPH (benign prostatic hypertrophy) • Monitoring: • Na and H20 retention with high doses • Side Effects: • Dizziness —Orthostatic hypotension, first dose syncope • Headaches • Reflex tachycardia • Fatigue

Vasodilators: direct • MOA: vascular smooth muscle relaxation • Compelling Indications: None • Second line therapy: Resistant HTN • Hydralazine • 10 – 50 mg qid; max 300 mg /day • Often dosed bid or tid to improve adherence • Rare but serious SE: Lupus erythematosus, blood dyscrasias, peripheral neuritis • Headaches, tachycardia, angina, nausea, diarrhea, rash • Minoxidil • Start 5 mg daily; usual 10-40 mg daily; max 100 mg daily • Rare but serious SE: Stevens-Johnson syndrome • Hypertrichosis— used topically to promote hair growth • Headache, edema, tachycardia, paresthesia

Vasodilators: direct Caution: Increased myocardial work Use in combination with B-blocker / diuretic to combat these effects

Central alpha 2 agonists • Bind to and activate α2 receptors in the brain • ↓ sympathetic outflow to the heart → CO and HR • ↓ sympathetic outflow to vasculature → ↓ vascular tone http://www.cvpharmacology.com/vasodilator/Central-acting.htm

Central alpha 2 agonists • Compelling Indications: None • Second line therapy: Resistant HTN • Clonidine • Start 0.1 mg bid, titrate up weekly: max 2.4 mg/day • Available as a transdermal patch changed weekly • Severe rebound HTN if stopped abruptly • Side Effects: sedation, depression, bradycardia + many more • Methyldopa • Start 250-500 mg bid-tid, adjust every 2-3 days, max 3gm/day • Can be used in pregnancy • Serious but uncommon SE: blood dyscrasias, myocarditis, pancreatitis • Side effects: sedation, orthostatic hypotension + many more

Antihypertensives: • α 1 blocker: • Prazosin, Doxazosin, Terazosin • Dizziness, edema • Centrally Acting: • Methlydopa • Clonidine • Sedation, dry mouth • Vascular Smooth Muscle: • Hydralazine, Minoxidil • CCBs • Headache, Dizziness, edema, • B-blockers: • Atenolol • Carvedilol • Metoprolol • Propranolol • Bradycardia • Diuretics: • Thiazide • Loop • Other • hypokalemia Renin ACE Angiotensinogen Angiotensin I Angiotensin II ARBs Aliskiren ACE Inhibitors Hyperkalemia, dry cough

Inadequate BP Response with Initial Agent • Increase dose • Substitute new drug from different class • Little to no response to initial drug • No compelling indication for the drug • Troublesome SE • Add a new drug from a different class • Initial drug produces some response and is well tolerated • Compelling indication for the initial drug • Add thiazide if not used initially

HTN: Special Populations • Elderly • Isolated systolic HTN common • SBP rises and DPB declines with aging • Generally salt sensitive • Use lower initial drug doses and slower dose titration • Avoid 1-blockers, labetalol, central 2 agonists • JNC-8 – higher BP goal? • AHA Consensus Statement on the Elderly 2011 • Goal SBP < 140 mm Hg • Age > 80, goal SBP < 150 mmHg • No evidence for lower BP goals for elderly patients at high risk, eg DM, CAD, CKD. • Maintain DBP > 65 mmHg --- coronary perfusion Circulation 2011;123:2434-2506

HTN Elderly Guidelines • Canada 2013 • In the very elderly (age ≥ 80), the target for SBP should be < 150 (grade C) • No changes for those age 65-79; ie goal remains at < 140/90 • Europe 2013 • In elderly < 80 years old with SBP ≥160 mmHg there is solid evidence to reducing SBP to 150 and 140 mmHg (IA) • In fit elderly patients < 80 years old SBP values <140 mmHg may be considered, whereas in the fragile elderly population SBP goals should be adapted to individual tolerability (IIb C) • If > 80 years and with initial SBP ≥160 mmHg, it is recommended to reduce SBP to between 150 and 140 mmHg provided they are in good physical and mental conditions (IB) • Benefit in treating elderly, ↓ stroke, CV events, heart failure Canadian Journal of Cardiology 2013;29:528-542

HTN: Special Populations • African Americans • Prevalence, severity and impact increased compared to other populations • Onset at younger age • More Na+ sensitive, lower plasma renin activity • Good response to Na restriction and diuretic therapy • response to ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and -blockers as monotherapy • HOWEVER, can be overcome by adding a diuretic • Still indicated if compelling indication exists! • ACE inhibitor angioedema 2-4 x more frequent

Hypertensive crisis

EMERGENCY BP >180/120 Acute Target Organ Damage Life threatening GOAL: BP now IV therapy URGENCY BP >180/120 No Target Organ Damage Not life-threatening GOAL: BP over days Oral therapy HYPERTENSION CRISES

HYPERTENSIVE EMERGENCIES • Heart • Acute coronary syndrome • Acute heart failure with pulmonary edema • Dissecting aortic aneurysm • CNS • Intra-cerebral hemorrhage / CVA • Encephalopathy • Eclampsia • Acute Renal Failure • Eyes: • Papilledema, hemorrhage

IV Vasodilators Sodium Nitroprusside Nicardipine Nitroglycerin Enalaprilat Fenoldopam Hydralazine IV Adrenergic Inhibitors Labetalol Esmolol Phentolamine Treatment for Hypertensive Emergencies • Goal: • Lower MAP no greater than 20-25% in a few hours • Maintain DBP 100-110 mmHg • Too rapid or too much cerebral hypoperfusion • Continuous BP monitoring

IV vasodilators * See next slide

IV vasodilators: MOA Fenoldopam D1 receptor agonist moderate affinity α2 vasodilation Release Pro drug • Nitroprusside: • arteriole and venous • No tolerance • Less effect on HR • Nitroglycerin • 1° venodilator • Arteriole dilator at high doses • + tolerance http://cvpharmacology.com/vasodilator/nitrodilator%20mech.gif http://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/imagecache/content_image_landscape/images/colorbox/dopamine.gif

IV vasodilators Duration of action varies from 1-2 min to 6 hours

Nitroprusside Toxicity Metabolism releases Cyanide • Increased Risk if: • Rate at ≥ 5 ug/kg/min • 2 ug/kg/min for prolonged use (24-48 hours) • Renal insufficiency • Can administer Na Thiosulfate to enhance metabolism of cyanide • Cyanide Toxicity • Weakness • Headaches • Vertigo • Confusion / giddiness • Perceived difficulty breathing • Thiocyanate Toxicity • Anorexia / nausea • Fatigue • Toxic psychosis http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/figures/1471-2253-13-9-1-l.jpg

IV adrenergic blockers Duration of action varies from 3-10 min to 6 hours

- More by User

Pharmacology of Adrenocorticosteroids

Learning Objectives. Discuss the physiology of adrenal gland function as it relates to corticosteroid synthesisProvide insight into use of select diagnostic drugs in adrenal pathological disordersReview feedback mechanisms in the HPA axis as it relates to drug induced adrenal suppressionOffer an

1.71k views • 73 slides

Pharmacology of Antidepressants

Pharmacology of Antidepressants. Douglas L. Geenens, D.O. The University of Health Sciences. Classes of Antidepressants Tricyclic-tertiary amines. amitriptyline (Elavil) imipramine (Tofranil) doxepin (Sinequan) clomipramine (Anafranil) trimipramine (Surmontil).

1.24k views • 50 slides

Pharmacology of Uterotonics

Pharmacology of Uterotonics. Uterotonics. Oxytocin Oxytocin Prostaglandin Ergot alkaloid Progesterone antagonist Tocolytics -adrenergist agonist Ca2+-channel blocker PG-synthase inhibitors Magnesium Sulfate Ethanol. Biosynthesis

1.13k views • 32 slides

Pharmacology of Nicotine

Pharmacology of Nicotine. Colleen Miller Lesley-Ann Giddings. What is nicotine?. plant alkaloid derived from nicotinic acid. http://www.scs.leeds.ac.uk/cgi-bin/pfaf/arr_html?Nicotiana+tabacum. How does nicotine act on receptors?. nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

977 views • 18 slides

Pharmacology of Coagulation

Pharmacology of Coagulation. Outline. I. Coagulation Cascade II. Anti-Clotting Mechanisms III. Drugs Affecting Coagulation. Outline. I. Coagulation Cascade II. Anti-Clotting Mechanisms III. Drugs Affecting Coagulation. Blood exhibits laminar flow in an intact vessel. A. Laminar.

830 views • 55 slides

PHARMACOLOGY OF INFLAMMATION

PHARMACOLOGY OF INFLAMMATION. David J. Mokler, Ph.D. October 29, 2009. OBJECTIVES. After studying this material the student should ; Describe the role of prostaglandins in the inflammatory response.

861 views • 66 slides

PHARMACOLOGY OF

PHARMACOLOGY OF. CONTRACEPTION. CONTRACEPTION. PHARMACOLOGY. ILOs. By the end of this lecture you will be able to: Perceive the different contraceptive utilities available Classify them according to their site and mechanism of action Justify the existing hormonal contraceptives present

476 views • 20 slides

PHARMACOLOGY OF SNS

PHARMACOLOGY OF SNS. According to chemistry. According to spectrum of action. According to mode of action. Adrenoceptor Blockers Adrenolytics. Adrenergic Neuron Blockers Sympatholytics. Alpha & beta- adrenergic receptor blockers. Differ in: Site of ganglia

544 views • 24 slides

Pharmacology of Cannabis

Pharmacology of Cannabis. Nathaniel Chow Robert Doan Samantha Polito Jason Tang Nov 27/13. PHM142 Fall 2013 Instructor: Dr. Jeffrey Henderson. What is Cannabis . What is Cannabis . Over 400 chemicals 61 are Cannabinoids Cannabinoids are pharmacologically active

773 views • 16 slides

Pharmacology of Vasoconstrictors

Pharmacology of Vasoconstrictors. What happens if you don’t use a vasoconstrictor ? *Plain local anesthetics are vasodilators by nature 1) Blood vessels in the area dilate 2) Increase absorption of the local anesthetic into the cardiovascular system (redistribution)

3.11k views • 35 slides

Hypertension Dr.Hassan H Alwafi MBBS, Demonstrator Department of Clinical Pharmacology UQU

Hypertension Dr.Hassan H Alwafi MBBS, Demonstrator Department of Clinical Pharmacology UQU. Hypertension The Silent Killer. Hypertension is the term used to describe high blood pressure .

845 views • 44 slides

PHARMACOLOGY OF ANAESTHETICS

PHARMACOLOGY OF ANAESTHETICS. Katarina Zadrazilova FN Brno, October 2010. AIMS OF ANAESTHESIA. Triad of anaesthesia. Neuromuscular blocking agents for muscle relaxation Analgesics /regional anaesthesia for analgesia Anaesthetic agents to produce unconsciousness.

1.27k views • 70 slides

Department of Pharmacology

Section 4 Drugs Affecting the Center Nervous System. Department of Pharmacology. Chapter 22 Sedative and hypnotic Drugs. Definitions A sedative drug decreases activity, moderates excitement, and calms the recipient.

425 views • 23 slides

Principles of Pharmacology

50. Principles of Pharmacology. Learning Outcomes . 50.1 Describe the five categories of pharmacology. 50.2 Differentiate between chemical, generic, and trade names for drugs. 50.3 Describe the major drug categories. 50.4 Identify the main sources of drug information.

820 views • 51 slides

Pharmacology of reproduction

Pharmacology of reproduction. ORAL CONTRACEPTION. ORAL STEROID CONTRACEPTION. COMBINED(COC) x only PROGESTIN (POP) x POSTCOITAL (PCC) efficacy- Pearl index 0,5 - 1 (COC), 0,5 - 4 (POP) ONE PHASE – stable estrogen ( ethinylestradiol ) + stable progestin (derivát 19-nortestosteronu )

724 views • 55 slides

pharmacology-of-asthma

105 views • 3 slides

Pharmacology of Interferon

Pharmacology of Interferon. Interferon. Natural Interferons. Man Made Interferons (Recombinant). Interferon Basics. Interferons play an important role in the first line of defense against viral infections Interferons are part of the non-specific immune system

506 views • 30 slides

Pharmacology of Chemotherapy

Pharmacology of Chemotherapy. David W. Hedley MD Dept Medical Oncology and Hematology Division of Applied Molecular Oncology. Chemotherapy. Cytotoxic agents - generally given by intravenous injection or orally Most chemotherapy drugs act by damaging DNA or inhibiting DNA synthesis

514 views • 50 slides

730 views • 70 slides

371 views • 32 slides

Pharmacology of Antidepressants. Dr Andrew P Mallon. Classes of Antidepressants Tricyclic-tertiary amines. amitriptyline (Elavil) imipramine (Tofranil) doxepin (Sinequan) clomipramine (Anafranil) trimipramine (Surmontil). Classes of Antidepressants Tricyclic-secondary amines.

679 views • 50 slides

Pharmacology of Alcohols

Pharmacology of Alcohols. Dr Javaria Arshad. History and overview. Arabs developed distillation about 800 C.E Word Alcohol derived from Arabic for ‘something subtle’ Alcohol abuse Alcoholic content of beverages ranges between 4% to 6% Wine contain 10% to 15% Alcohol.

418 views • 37 slides

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Mater Sociomed

- v.26(1); 2014 Feb

Clinical Presentation of Hypertensive Crises in Emergency Medical Services

Sabina salkic.

1 Emergency medical services, Community Health Centre Tuzla

Olivera Batic-Mujanovic

2 Family Medicine Education Centre, Community Health Centre Tuzla

Farid Ljuca

3 Faculty of Medicine, University of Tuzla

Selmira Brkic

Objectives:.

The objective of this study is to evaluate the incidence and clinical presentation of hypertensive crises in the Emergency medical services of the Community Health Centre “Dr. Mustafa Šehović” Tuzla in relation to age, sex, duration and severity of hypertension, as well as the prevalence of accompanying symptoms and clinical manifestations.

The study was conducted between November 2009 and April 2010 and included 180 subjects of both sexes, aged 30-80 with a diagnosis of arterial hypertension. All subjects were divided into two groups: a control group, which consisted of subjects without hypertensive crisis (95 subjects) and an experimental group that consisted of subjects with hypertensive crisis (85 subjects).

The study results indicate that female subjects were significantly over- represented compared to men (60% vs. 40 %, p=0.007). The average age of the male subjects was 55.83±11.06 years, while the female subjects’ average age was 59.41±11.97 years. The incidence of hypertensive crisis was 47.22%, with hypertensive urgency significantly more represented than emergency (16.47% vs. 83.53%, p<0.0001). The majority of subjects in the experimental group (28.23%) belonged to the age group of 60-69 years of age: 26.76% urgency and 35.71% emergency. The most common accompanying symptoms in hypertensive subjects were headache (75%), chest pain (48.33%), vertigo (44.44%), shortness of breath (38.88%) and nausea (33.89%). The most common symptoms in subjects with hypertensive crisis were headache (74.11%), chest pain and shortness of breath (62.35%), vertigo (49.41%), and nausea and vomiting (41.17%).

Conclusions:

Chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea and vomiting were significantly over-represented in subjects with hypertensive crisis (p<0.005). Clinical manifestations of hypertensive emergencies in almost all subjects included acute coronary syndrome, and only one subject had acute pulmonary edema.

1. INTRODUCTION

Arterial hypertension is the main independent risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease and mortality in developed, as well as developing countries, such as our country. About 50% of all cases of myocardial infarction and about 60% of cerebrovascular events are the result of high blood pressure. The World Health Organization defines arterial hypertension as the level of systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg or higher and/or diastolic blood pressure of 90 mmHg or higher in people not taking antihypertensive therapy ( 1 ).

Hypertensive crisis is a case of massive, acute increase in blood pressure which directly endangers the patient’s life, represented by symptoms of hypertension which developed suddenly and which is caused by various etiological moments ( 2 ). Hypertensive crisis is defined as levels of systolic blood pressure >180 mmHg and/or levels of diastolic blood pressure >120 mmHg and is usually seen in patients with essential hypertension ( 3 ). In addition, hypertensive crisis is a severe clinical condition in which a sudden increase in arterial blood pressure can lead to acute vascular damage of vital organs, so timely detection, evaluation and adequate treatment are crucial to preventing permanent damage to vital organs ( 4 ). Depending on whether there is damage to vital organs or not, we can distinguish between hypertensive emergency and hypertensive urgency. Hypertensive emergencies are life-threatening conditions because their outcome is complicated by acute damage to vital organs, and can be presented with neurological, renal, cardiovascular, microangiopathic and obstetric complications ( 5 ). Hypertensive emergencies include hypertensive encephalopathy, hypertensive acute left ventricular relaxation associated with acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina, aortic dissection, subarhnoic hemorrhage, ischemic stroke, and severe pre-eclampsia or eclampsia ( 2 ). Hypertensive urgency is a situation with severe increase in blood pressure without progressive dysfunction of vital organs. The most common symptoms are headache, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, epistaxis, and pronounced anxiety ( 6 ).

Hypertension is present in approximately one billion of the world population and is responsible for an average of 7.1 million deaths annually. It is estimated that approximately 1% of patients with hypertension at some point develop a hypertensive crisis ( 7 ). The incidence and prevalence of hypertensive crisis in the population have not been largely discussed in the medical literature. Although the incidence of hypertensive crisis is low (1%), hypertensive crisis is present in more than 500,000 Americans each year ( 8 ).

Pathophysiology of hypertensive crisis has not been entirely elucidated. In terms of pathophysiology, a disruption in the autoregulation of systemic circulation at the level of arterioles is considered to be the cause of both forms of hypertensive crisis ( 9 ).

The fact is that in about 50% of patients with hypertensive crisis the disease progresses to that extent asymptomatically and, unfortunately, hypertensive emergency and urgency are still the least understood and the worst treated acute medical problems ( 10 ).

The aim of the research is to determine the prevalence of accompanying symptoms and clinical manifestations in relation to age, sex, level of arterial blood pressure and duration of hypertension.

2. EXAMINEES AND METHODS

This paper presents and analyzes the results of a prospective study which evaluated the prevalence and clinical presentation of hypertensive crises at the level of primary health care. The study was conducted in the Emergency medical services of the Community Health Centre “Dr. Mustafa Šehović” Tuzla from November 2009 to April 2010. This study encompassed all consecutive hypertensive patients of both sexes and aged 30-80 who sought the emergency medical services of the Community Health Center Tuzla.

The study included a total of 180 hypertensive subjects divided into two groups, the control and the experimental group. The experimental group consisted of hypertensive patients with hypertensive crisis, a total of 85 subjects (47%), and the control group consisted of hypertensive patients without hypertensive crisis, a total of 95 subjects (53%).

The diagnosis of arterial hypertension was established in accordance with the definition of the World Health Organization, which defines arterial hypertension as the level of systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg in people who are not taking antihypertensive therapy (Anonymous, 1999) ( 1 ). Hypertensive crisis is defined as levels of systolic blood pressure >180 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure >120 mmHg in accordance with Guidelines of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute) ( 3 ).

The criterion for inclusion in the study was the presence of hypertension. The study excluded hypertensive patients with mental illness, patients in the terminal stage of a malignant disease, patients on the chronic dialysis program, on cytotoxic therapy and long-term corticosteroid therapy, patients on oral contraceptive therapy, cocaine and amphetamine overdose. Subjects who were included in the study gave their voluntary written consent to want to participate in the study in accordance with the Code of Ethics ( 11 ).

Clinical evaluation of each subject included taking medical history data on the presence of some of the accompanying symptoms: chest pain, shortness of breath, headache, nausea and vomiting, epistaxis, anxiety, cramping, focal neurological signs and visual disturbances. The subjects provided data on the duration of hypertension, the antihypertensive therapy used and the presence of other associated diseases (coronary heart disease, heart failure, stroke and diabetes).

Blood pressure of all patients was measured with a Welch Allyn mercury sphygmomanometer (SN 07319092504 Shock-Resistant CE0297), cuff size 34,3×11×25,3 cm. Blood pressure was measured in a sitting position after a 5 minute rest. Subjects with blood pressure ³140/90mmHg were classified according to the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension (ECS/EHS) ( 12 ). Subjects in the control group had values of 140-179 mmHg for systolic and 90-119 mmHg for diastolic blood pressure. Subjects in the experimental group with hypertensive crisis, i.e. systolic blood pressure >180 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure >120 mmHg were classified into two groups: patients with hypertensive urgency (a condition with a significant increase in blood pressure without progressive damage to vital organs) and patients with hypertensive emergency (a condition with a significant increase in blood pressure with the presence of damage to vital organs, such as hypertensive encephalopathy, acute left ventricular relaxation, associated with myocardial infarction, aortic dissection, subarachnoid hemorrhage or ischemic stroke) in accordance with the guidelines of the U.S. National institutes of Health (National institutes of health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute) ( 3 ).

In addition to measuring blood pressure, physical examination of the subjects included the physical examination of cardiovascular and respiratory systems, as well as a neurological and ophthalmological examination.

All patients had an electrocardiogram with 12 conventional drains under optimal conditions (recording speed 25 mm/s, calibrated gauge deflection 1mV/10 mm), and the device used was

Schiller AT-102 Type Serial No.070.00123 Schiller CH-6340 Baar, Switzerland. Processing of the electrocardiographic recording was performed with a traditional ruler with millimeter divisions.

For the statistical analysis of results we used methods of descriptive statistics (measures of central tendency, measures of dispersion). For comparison of proportions and mean values between the groups we used the χ 2 -test and the Student’s t-test. Statistical hypotheses were tested at the significance level of α = 0.05, i.e. the difference between the groups was considered statistically significant if p<0.05.

In the prospective study, which evaluated the prevalence and clinical presentation of hypertensive crises in the Emergency medical services of the Community Health Centre “Dr. Mustafa Šehović” Tuzla, there was a total of 180 patients: 72 men (40%) and 108 women (60%), with women statistically significantly more represented than men (p = 0.007).

There was no statistically significant difference (p>0.05) in the proportion of subjects in the control and experimental group in relation to sex.

Analyzing the representation of subjects in the experimental groups according to clinical presentation (hypertensive urgencies and emergencies), it was observed that hypertensive urgencies were significantly more common than emergencies: 71 (83.53%) vs. 14 (16.47%) (p<0.0001).

There was no statistically significant difference in the proportions of subjects with hypertensive emergency and urgency in relation to gender (p=0.6598). There was no statistically significant difference between subjects in the experimental and control group with respect to age, and also in the average age of both sexes between the control and experimental group (p>0.05).

There was a statistically significant difference (p<0.05) in the mean value of systolic pressure in subjects of both sexes between the control and the experimental group (p<0.0001), and there was also a statistically significant difference (p<0.05) in the mean value of diastolic blood pressure in subjects of both sexes between the control and the experimental groups (p<0.0001).

Analyzing the structure of the subjects according to the accompanying symptoms in the control and experimental group (sample), and based on the calculated p-values that were less than the significance level of α = 0.05 (5%) at which the test was performed, there is a statistically significant difference in the proportion of subjects between the control and experimental group in terms of the accompanying symptoms: nausea, vomiting, chest pain, shortness of breath, with a higher percentage recorded in the experimental group (p<0.0001). The most common accompanying symptoms were headache and vertigo. Data on the distribution of accompanying symptoms in the control and experimental group are shown in Table 1 .

Distribution of control and experimental group by prevalence of accompanying symptoms

Table 2 shows the distribution of subjects in the experimental group by prevalence of accompanying symptoms. Analyzing the structure of the subjects by condition (emergency or urgency) and accompanying symptoms, and based on the calculated p-values that were less than the significance level of α = 0.05 (5%) at which the test was performed, a significantly higher proportion of patients with hypertensive emergencies had accompanying symptoms: headache, chest pain and shortness of breath (p<0.05).

Distribution of subjects in experimental group by prevalence of accompanying symptoms

There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of male and female subjects between the urgency and emergency group. Data on the distribution of accompanying symptoms of subjects in the urgency and emergency group by sex are shown in Tables Tables3 3 and and4 4 .

Distribution of patients with hypertensive urgency by prevalence of accompanying symptoms

Distribution of patients with hypertensive emergency by prevalence of accompanying symptoms

Based on the data on the distribution of subjects by the accompanying symptoms in relation to the duration of hypertension, since the calculated (empirical) chi-square is higher than the tabular chi-square for the risk of 0.05 (5%) and 2 degrees of freedom amounting to 5.991, there was a statistically significant difference in the relative participation (percentile) of certain accompanying symptoms between the three groups of subjects grouped according to the duration of hypertension.

Table 5 illustrates the distribution of subjects in the experimental group according to the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy, based on the characteristics obtained using the ECG method. From these data we can see that left ventricular hypertrophy was present in 26 subjects (36.62%) in the urgency group and in 14 subjects (100.00%) in the emergency group.

Distribution of subjects in the experimental group by presence of left ventricular hypertrophy

Analysis of the data on left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) indicated that a significantly higher proportion of subjects in the experimental group had left ventricular hypertrophy (P=0.0001).

A significantly higher proportion of subjects with hypertensive emergency had left ventricular hypertrophy in relation to subjects with hypertensive urgency (36.62% vs. 100.00%, p<0.0001). Analyzing the clinical manifestations of hypertensive emergency, it was observed that of the 14 subjects with hypertensive emergency 13 (92.86%) (8 female and 5 male subjects) had the clinical presentation and electrocardiographic features of acute coronary syndrome, and only one male subject (7.14%) had the clinical presentation of acute pulmonary edema.

4. DISCUSSION

Hypertensive crises are urgent conditions, often life-threatening, which are characterized by a sudden onset of increased blood pressure and which are represented in more than a quarter of all medical urgencies/emergencies. As a rule, it remains unclear when and why a persistent significant increase in arterial blood pressure develops into a hypertensive crisis. The fact is that in about 50% of patients with hypertensive crisis the disease progresses to that extent asymptomatically and, unfortunately, hypertensive emergency and urgency are still the least understood and the worst treated acute medical problems.

Unlike our study, the Al-Bannay and Husain cohort study, which examined the clinical presentation and comorbidities of hypertensive crises and included 154 patients with systolic and diastolic blood pressure >179 mm Hg and >119 mm Hg, concluded that 64.3% of subjects had hypertensive urgency, while hypertensive emergency was present in a higher percentage compared to our results (35.7%). In our study, hypertensive emergencies were present in 16.47% of the subjects. Given that this type of hypertensive crisis is characterized by damage to the target organs, it is assumed that the risk factors (stress, improper diet, excessive salt intake, cigarette and alcohol consumption, inadequate physical activity) that are conducive to the development of this condition were less present in the subjects of our study than in the subjects of the above-mentioned study. Their study also showed that men were over-represented compared to women (100:54) and that the majority of subjects belonged to the age group of 45-65 years of age ( 13 ). In our study, most of the subjects belonged to the age group of 60-69 years (28.23%), probably because hypertension is detected later in life, since the symptoms of this disease are particularly “covert” and, unfortunately, are most commonly detected only when they lead to the development of a potentially life-threatening symptom or complication, which is in direct correlation with the potentially lethal outcome. The one-year study by Zampaglione et al showed that out of 14.209 patients that checked into the Internal Medicine Emergency Unit, 1634 (11.5%) were classified as hypertensive crisis, 76% of whom had hypertensive urgency and 24 % hypertensive emergency. In the same study, the number of women identified with the condition was larger than that of men, as in our study. 23% of patients who checked in did not know that they were suffering from hypertension ( 14 ).

The data from these studies differ from the data obtained in our study, which suggest a much greater representation of hypertensive crisis in emergency medicine (11.5% vs. 47.23%). It is devastating that our study revealed that such a large number of patients suffer from unregulated hypertension. The probable reason for this is that the vast majority of patients do not take their disease seriously and do not adhere properly to the prescribed therapies and recommended lifestyle. On the other hand, the reason for such a large percentage of hypertensive crises may be the use of inadequate antihypertensive drugs or irregular control of blood pressure. Also, our results showed that hypertensive emergencies were less common (16.47%), while hypertensive urgencies were more common in our study compared to the data from the Zampaglione et al study (83.53% vs. 76%). Similar to the Zampaglione et al study, women were represented in greater numbers than men, namely 63.38% as hypertensive urgency and 57.14% as hypertensive emergency.

If, on the other hand, we compare the data on the percentage of hypertensive urgencies and emergencies with data from the Martin et al study, it is evident that, out of 452 patients, 60.4% were hypertensive urgency and 39.6% were hypertensive emergency, which is a slightly smaller percentage of urgencies, and higher percentage of emergencies, compared to the data obtained in our study. If we observe the age of subjects suffering from hypertensive urgency in this study, which was 59±14.8 vs. 49.9±18.6 years, it is evident that in the Martin et al study the 60-80 age group was the most represented for hypertensive emergency ( 15 ).

Of the total number of subjects in our study, hypertensive crisis was observed in 47.23% of the subjects. Although women were significantly more represented than men (60% vs. 40%, p=0.007) there was not a large difference in the percentage of hypertensive crisis between the two sexes. Unlike men, women have a higher prevalence of hypertension in elderly age, during the period of menopause and post-menopause, when there are changes in hormone balance which up to that period must have acted as a protective mechanism in the development of arterial hypertension. This is supported by the data from our study, where the average age of the women developing a hypertensive crisis was 61.35±11.83, while in men it was 55.56±10.36 years of age. Similar data have been reported in the Zampaglione et al study, which revealed that 60% of the female subjects were classified in the group with hypertensive crisis, and that women were over-represented in the total hypertensive population.

By analyzing the accompanying symptoms, it can be seen that in the total number of subjects of all ages the most common accompanying symptom were headache (75%) and vertigo (44.44%). The Zampaglione et al study showed that the most common accompanying symptom in the hypertensive urgency group was headache (22%), then epistaxis (17%) and psychomotor agitation (10%), while in the hypertensive emergency group the most common symptom were chest pain (27%), shortness of breath (22%) and hypertensive encephalopathy (16%). Unlike our results, which indicated that acute coronary syndrome and acute left ventricular relaxation were the only two clinical manifestations of hypertensive emergency, the Martin et al study concluded that hypertensive crises constituted 0.5% of all urgency cases and 1.7% of all clinical emergencies, with cerebral ischemic stroke and acute pulmonary edema the most common hypertensive emergencies, which was correlated with neurological deficits and dyspnea ( 15 ). The 1996 Zampaglione et al study found that the most common clinical presentation of hypertensive emergency was cerebral infarction (24.5%), pulmonary edema (22.5%), followed by hypertensive encephalopathy (16.3%) and congestive heart failure (12%) ( 14 ). Based on the data of our study on the clinical manifestation of hypertensive emergency and the accompanying pathology of cardiovascular origin in the Emergency medical services, it can be assumed that the patients in this region simply have greater affinity for the development of any segment of cardiovascular incident.

5. CONCLUSION

The total sample of 180 subjects was 60% female and 40% male. The incidence of hypertensive crises in the Emergency medical services was high at 47.22%. The largest number of subjects (28.23%) with hypertensive crisis belonged to the age group of 60-69. Hypertensive urgencies were significantly more common than emergencies (88.53% vs. 16.47%, p<0.0001). The average blood pressure in subjects with hypertensive crisis was 204.82/126.58 mmHg. There was no statistically significant difference in the number of patients with hypertensive urgency and emergency in relation to age, gender, duration of hypertension, except for the 40-49 age group, where urgency was statistically significantly higher (p=0.0407). The most common symptoms in subjects with hypertensive crisis were headache (74.11%), chest pain and shortness of breath (62.35%), vertigo (49.41%), and nausea and vomiting (41.17%). Chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea and vomiting were significantly over-represented in patients with hypertensive crisis (p<0.005). The most common symptoms of hypertensive urgency were headache (78.87%) and chest pain (56.34%), while the most common symptoms of hypertensive emergency were chest pain (92.86%) and shortness of breath (71.43%). Headache, chest pain and shortness of breath were significantly over-represented in patients with hypertensive emergency (p<0.005). Clinical manifestations of hypertensive emergency were acute coronary syndrome (92.86%) and acute pulmonary edema (7.14%).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: NONE DECLARED.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Hypertension - Download as a PDF or view online for free. 8. SYMPATHETIC NERVOUS SYSTEM ACTIVITIES When the BP is decreasing the activation of SNS will occur. The increased SNS activity increases the heart rate and cardiac contraction. The increased the heart rate and cardiac contraction produce vasoconstriction in the peripheral arterioles and promotes the release of renin from kidney. The ...

Hypertension 2020 Updated Guidelines. Dec 11, 2019 • Download as PPTX, PDF •. 93 likes • 47,778 views. Dr. Aryan (Anish Dhakal) Management of hypertensive condition in 2020 according to AHA/ASA guidelines. We will discuss the presentation, clinical assessment, investigations, and management of hypertension along with major randomized ...

It defines hypertension and provides normal and elevated blood pressure readings. It describes the types and causes of primary and secondary hypertension. It discusses the risk factors, mechanisms, diagnosis, clinical presentation, complications and treatment of hypertension, including lifestyle modifications and medication options.

Case Presentation (SRP-Non-Surgical) on a Patient assessed with Hypertension 2. Hypertension ⚫ also known as high blood pressure ⚫ is a long term medical condition in which the blood pressure in the arteries is persistently elevated ⚫major risk factor for coronary artery disease, stroke, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, vision ...

Pathophysiology of Hypertension • Resting Blood Pressure ≥ 140/90 on two separate occasions in an individual is characterized as either Stage I or Stage II Hypertension. • Resting Blood Pressure ≥ 130/80 in diabetic patients increases their risk for the development of heart disease. 9. Nutritional Assessment. 10.

HTN: Treatment Targets. First objective: <140/90 mm Hg. Once there: try even harder, if tolerated! Optimal goal: SBP < 130 mm Hg and DBP < 80 mm Hg. If BP medications start to cause activity-limiting orthostatic symptoms, reaching optimal goal may not be possible.

Hypertension pathophysiology. Hypertension is defined as persistently elevated arterial blood pressure (BP). JNC7 Guidelines: Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on the Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure JNC7 is the national clinical guideline that was developed to aid clinicians in the management of ...

A study by Wong and Mitchell indicated that independent of other risk factors, the presence of certain signs of hypertensive retinopathy (eg, retinal hemorrhages, microaneurysms, cotton-wool spots) is associated with an increased cardiovascular risk (eg, stroke, stroke mortality). [] Consequently, a funduscopic eye evaluation can help identify any signs of early or late, chronic or acute ...

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, has been documented as far back as 2600 BC. It was not until the early 18th century that methods for measuring blood pressure were developed. Blood pressure is determined by cardiac output and systemic vascular resistance. Sustained elevated blood pressure is defined as hypertension.

Use an electronic or paper registry that identifies patients with high blood pressure. and allows tracking over time. Use electronic health records to collate and analyze clinical information. Provide regular and timely feedback on performance to the entire health care team.

Promoting and ... is a powerpoint presentation that summarizes the impacts of the new hypertension guidelines on clinical practice and research. It covers the definition, prevalence, risk factors, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of hypertension, as well as the role of translational science in addressing this major public health issue. The presentation is based on the expertise of Dr ...

Person 1 plays the role of a patient newly diagnosed with hypertension but with no symptoms. Person 2 plays the role of the health care provider explaining why treatment is necessary. In pairs, take turns so that each person plays each role. Simple, detailed protocols. Administrative and operational procedures in place to enable.

Hypertension or high blood pressure, is when an individual has consistently high arterial blood pressure, also known as the force with which blood flows through a person's blood vessels (McCance & Huether, 2019). A normal blood pressure reading is a systolic (upper) number lower than 120 mmHg and a diastolic (lower) number that is lower than ...

Download PowerPoint File. Description: Slide Set | 2017 Guideline For the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults (Updated May 2018)

Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42 (6):1206-1252. 3. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint ...

severely elevated arterial BP (SBP >180 and/or DBP >120 mm Hg) with nonspecific complaints but without evidence of acute target organ damage. It has less serious prognosis than hypertensive emergency in spite of severe hypertension. Most of the hypertensive crisis presentations (75%) are hypertensive urgencies.

Clinical Presentation of HELLP Syndrome • Extremely variable presentation of symptoms • Common findings: - RUQ pain, epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting - 85% hypertensive • Differential diagnosis can include biliary colic, pancreatitis, acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP), gastroesophageal reflux disease,

What is hypertension? Hypertension—or high blood pressure—can happen steadily over long periods of time and have no clear cause, called primary hypertension,...

Hypertension in the ICU. By. Noemie Chessex and colleagues. UBC. Case A 19-year-old man presents to ED with episodic headaches that resolved spontaneously. In the last week, the headaches have become much more severe and frequent, occurring almost daily, and are accompanied by throbbing chest pain, sweating, dizziness and palpitations.

Presentation Transcript. Pharmacology of Hypertension Vicki Groo, Pharm.d. Clinical Associate Professor Clinical pharmacist, heart center [email protected] 413-0928. objectives • Classify hypertension and define treatment goals • Be able to describe the pharmacology of oral antihypertensives with considerations in drug choice and compelling ...

Case Presentation. The patient was a 17-year-old male who was admitted to our hospital in May 2020 due to uncontrolled hypertension for 6 months and weakness of limbs for 20 days. Six months prior to admission, blood pressure of the patient was found to have increased to 200/120 mmHg during the physical examination.

History. In the evaluation of ocular hypertension, details should be obtained with respect to the following: Ocular hypertension (OHT) can be used as a generic term referring to any situation in which intraocular pressure (IOP) is greater than 21 mm Hg, the widely accepted upper limit of normal intraocular pressure in the general population.

The incidence of hypertensive crises in the Emergency medical services was high at 47.22%. The largest number of subjects (28.23%) with hypertensive crisis belonged to the age group of 60-69. Hypertensive urgencies were significantly more common than emergencies (88.53% vs. 16.47%, p<0.0001). The average blood pressure in subjects with ...