Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

60 Aristotelian (Classical) Argument Model

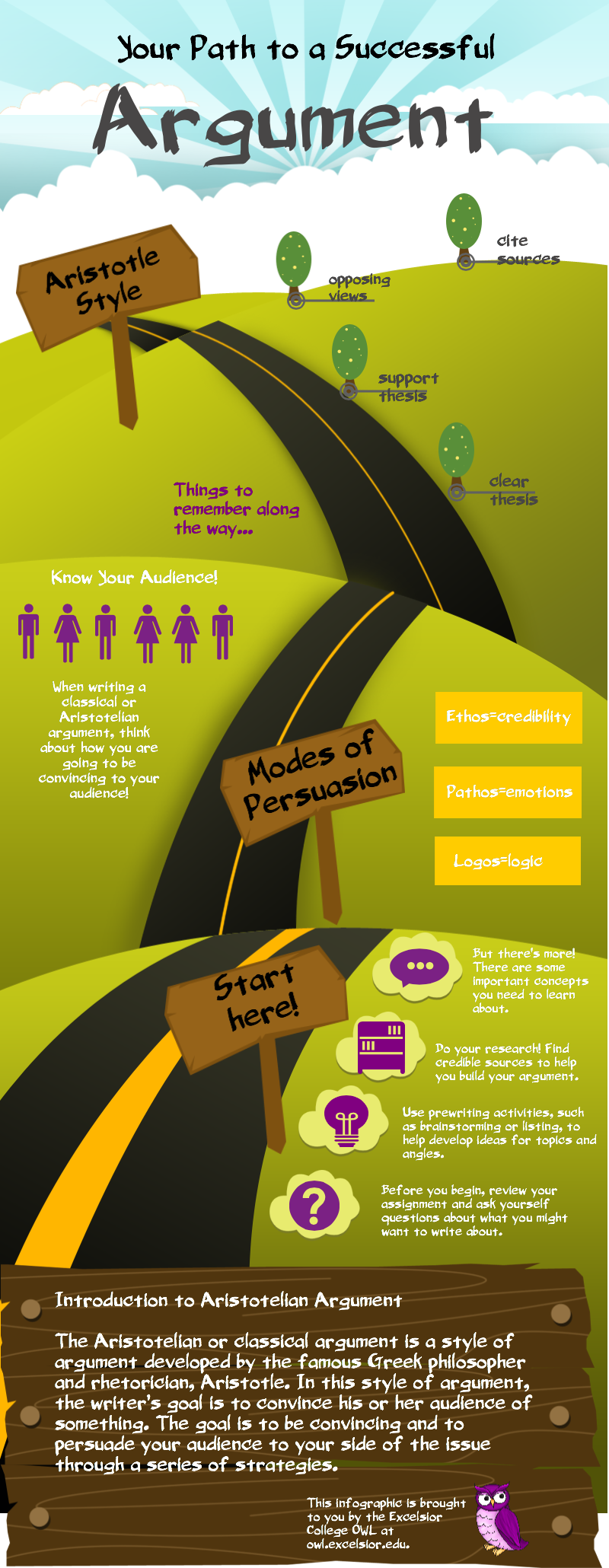

Aristotelian argument.

The Aristotelian or classical argument is a style of argument developed by the famous Greek philosopher and rhetorician, Aristotle . In this style of argument, your goal as a writer is to convince your audience of something. The goal is to use a series of strategies to persuade your audience to adopt your side of the issue. Although ethos , pathos , and logos play a role in any argument, this style of argument utilizes them in the most persuasive ways possible.

Of course, your professor may require some variations, but here is the basic format for an Aristotelian, or classical, argumentative essay:

- Introduce your issue. At the end of your introduction, most professors will ask you to present your thesis. The idea is to present your readers with your main point and then dig into it.

- Present your case by explaining the issue in detail and why something must be done or a way of thinking is not working. This will take place over several paragraphs.

- Address the opposition. Use a few paragraphs to explain the other side. Refute the opposition one point at a time.

- Provide your proof. After you address the other side, you’ll want to provide clear evidence that your side is the best side.

- Present your conclusion. In your conclusion, you should remind your readers of your main point or thesis and summarize the key points of your argument. If you are arguing for some kind of change, this is a good place to give your audience a call to action. Tell them what they could do to make a change.

For a visual representation of this type of argument, check out the Aristotelian infographic below:

Introduction to Aristotelian Argument

The Aristotelian or classical argument is a style of argument developed by the famous Greek philosopher and rhetorician, Aristotle. In this style of argument, the writer’s goal is to be convincing and to persuade your audience to your side of the issue through a series of strategies.

Start here!

Before you begin, review your assignment and ask yourself questions about what you might want to write about.

Use prewriting activities, such as brainstorming or listing, to help develop ideas for topics and angles.

Do your research! Find credible sources to help you build your argument.

But there’s more! There are some important concepts you need to learn about.

Modes of Persuasion

Ethos=credibility

Pathos=emotions

Logos=logic

Know Your Audience!

When writing a classical or Aristotelian argument, think about how you are going to be convincing to your audience!

Things to remember along the way…

Clear thesis

Support thesis

Opposing views

Cite sources

Sample Essay

For a sample essay written in the Aristotelian model, click here .

Aristotelian (Classical) Argument Model Copyright © 2020 by Liza Long; Amy Minervini; and Joel Gladd is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Corrections

Aristotle’s Model of Communication: 3 Key Elements of Persuasion

What was Aristotle’s contribution to rhetoric? We explore his influential model of communication.

Aristotle took a stance on almost every possible philosophical debate of his time, but more importantly, he came up with new issues and kickstarted new discussions as well. Aristotle was one of the first thinkers to delve into rhetoric and contributed greatly to its forming and development. He came up with many insights and theories on the topic of linguistics within rhetoric. However, his communication model remains his most prominent theory to this day. Let’s see what his model of communication consists of.

Introduction to Aristotle’s Model of Communication

Before we begin analyzing Aristotle’s model of communication, some context is needed. Aristotle was one of the first philosophers that worked on the art of speaking. It was his treatise Rhetoric that founded the basic principles of rhetorical theory and spoke openly about the art of persuasion. To this day, most rhetoricians regard it as the most important single work on persuasion ever written. That’s why Aristotle’s model of communication is still used to this day.

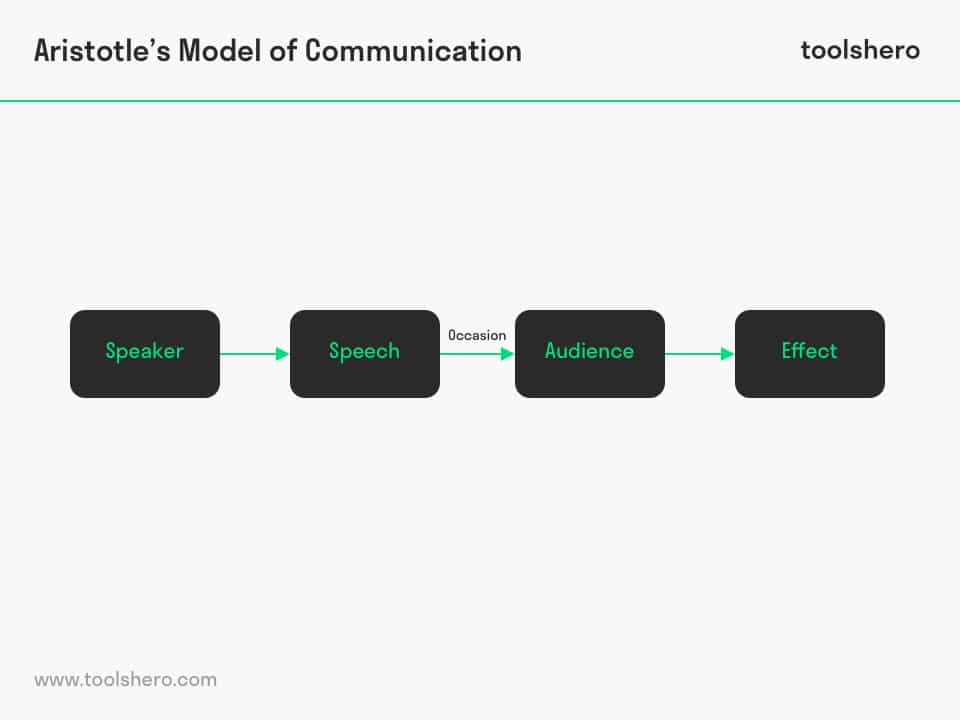

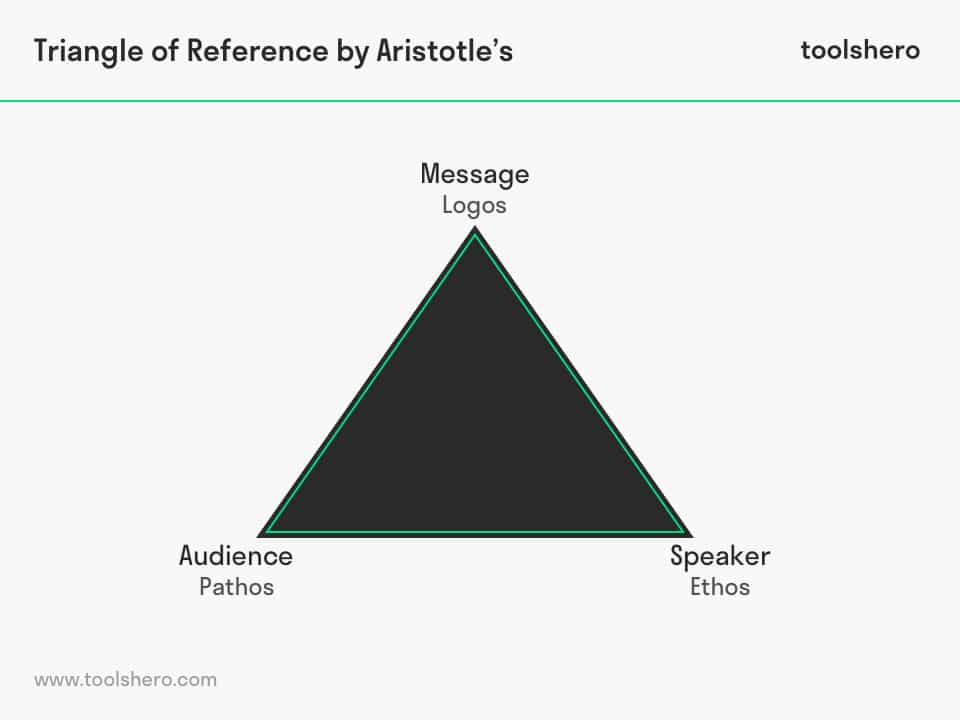

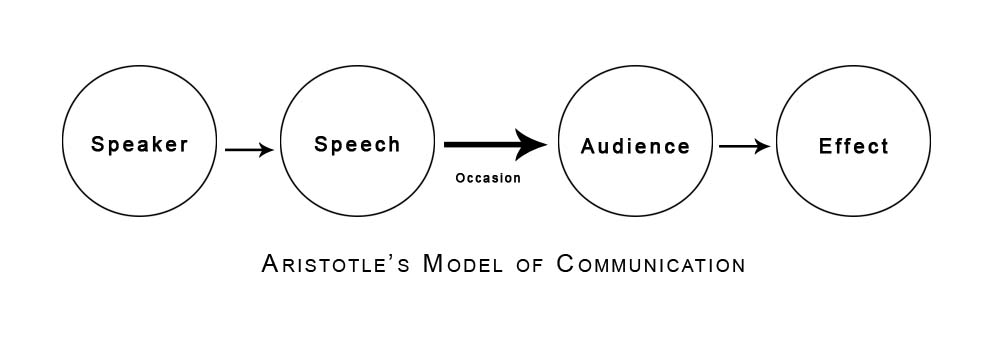

Aristotle’s model of communication is also known as the “rhetorical triangle” or as the “speaker-audience-message” model. It consists of three main elements: the speaker, the audience, and the message.

1. The Speaker

The speaker is the person who is delivering the message. In this model, the speaker is responsible for creating and delivering the message effectively. This includes not only the words used but also the delivery style, tone, and body language.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription, 2. the audience .

The audience is the group of people who receive the message. In this model, the audience is considered an essential part of the communication process. The speaker needs to understand the audience’s needs, interests, beliefs, and values to effectively communicate the message.

3. The Message

The message is the content of what is being communicated. In this model, the message should be clear, concise, and persuasive. The message should be crafted with the audience in mind to ensure that it is relevant and engaging.

Aristotle’s model of communication is important because it seems plausible and valid even in our modern lives. His model consists of three bullet points or three main important elements. That’s why we’ll explore each of them one by one.

The First Element of Communication: Ethos

The first element Aristotle comes up with is what he calls ethos . Ethos is essentially the speaker’s credibility to talk about the subject that he’s talking about and discuss it openly and with certainty.

What Aristotle means by ethos is the process of the speaker establishing his credibility about the subject he’s talking about. That can simply be done by mentioning the area of expertise he had majored in, but it can also be done by demonstrating his ability to back up his arguments. Credibility can also be built by using evidence, citing sources, or drawing on the speaker’s own experience or expertise. That’s why having empirical data to back up your arguments with clear proof is essential for this point.

What this does to an audience is create an image of the speaker as someone who knows what they are talking about and as someone that they can easily rely on and trust. That’s why Aristotle mentions it as the first important point out of the 3 most important ones.

The Second Element of Communication: Pathos

The second most important element of communication is what Aristotle calls pathos . The literal translation of pathos is emotion. Pathos is essentially the speaker establishing an emotional connection with the audience he’s speaking to.

The idea behind pathos is that the audience has to feel that they are being communicated with or that they are, in a way, interconnected. Emotional bonds will make the listeners fascinated, and they feel the speaker is “one of them.” In certain situations, the audience might want to feel more confident; in others, sadder, angry, or emotional. So, in Aristotle’s model of communication, pathos refers to the emotional appeal of a message. It focuses on engaging the audience’s emotions and creating a connection with them in order to persuade or influence their attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors.

Pathos can be conveyed through various elements of communication, such as tone of voice, facial expressions, body language, and the use of vivid language and imagery. In order to effectively use pathos in communication, Aristotle suggested that speakers should have a deep understanding of their audience and their emotional state. By appealing to their emotions and creating a connection with them, speakers can make their message more memorable and impactful.

The Third Element of Communication: Logos

The third most important element of communication Aristotle points out is logos. Logos refers to the logical or rational appeal of a message. This element focuses on the substance of the message and how it is presented to the audience.

Logos can be seen as the argument or reasoning behind a message, and it is often used to appeal to the audience’s sense of logic or reason. While ethos refers to the credibility or trustworthiness of the speaker or source of the message, and pathos refers to the emotional appeal in a message, logos focuses on the logical appeal and the argumentative structure of the message itself.

In order to effectively use logos in communication, Aristotle suggested that speakers should use clear and logical arguments, present evidence or facts to support their claims, and use reasoning to connect their ideas and persuade their audience. By appealing to the audience’s sense of logic and reason, speakers can create a persuasive message that is grounded in substance and can effectively influence their audience.

Criticisms of Aristotle’s Model of Communication

Now that we’ve carefully analyzed Aristotle’s model of communication, it’s time to look into the strong and weak points of the theory.

When it comes to the theory’s strengths, we can mention the following. First and foremost, the model emphasizes the importance of understanding the audience and adapting the message to their needs and interests. This means that the model’s main focus is figuring out the best approach to get through to the audience and their concerns, needs, and interests.

The second advantage this model provides is a clear structure for organizing a persuasive message, including the use of logos, ethos, and pathos. This makes it easier for the speaker to tailor his speech easily by following a particular structure. The third strength of this model is that it shows the importance of effective delivery techniques, such as tone and body language, which can enhance the impact of the message. Through these techniques, the speaker can easily point out a particular sentence or saying that he wants the audience to notice, for example.

However, regardless of the model’s many strengths, many of them unmentioned here, it is important to think critically and mention some of its weaker points and limitations.

First, the model is primarily focused on persuasion and may not be as useful in non-persuasive communication contexts. The model’s main use is having an audience involved at an event of a certain kind, which is why it may not be efficient for everyday use.

The second and probably most notable limitation of this theory is that the model assumes that communication is a linear process and does not account for the dynamic and interactive nature of communication. This means that the model does not leave any space for any sort of feedback, questions, or brainstorming sessions from the audience, taking them to be passive listeners to the speech the speaker is giving. Thus, the model is only applicable to public speaking of a very specific kind.

Some thinkers object to this limitation. Even though Aristotle’s model of communication is mostly associated with public speaking and formal communication situations, they say, the principles of effective communication outlined in Aristotle’s model can also be applied to everyday communication. For example, understanding the audience’s needs and interests can help us communicate more effectively with friends, family members, and coworkers. Crafting a clear and concise message can also help us avoid misunderstandings and conflicts in everyday interactions. Aristotle’s model of communication emphasizes the importance of understanding the audience and crafting a persuasive message, which is an essential skill in all types of communication, whether it’s public speaking or everyday conversation. Still, the model’s limitation still stands and is plausible.

The third limitation is that the model may not account for contextual factors that can influence communication, such as cultural differences or power dynamics.

The Lasting Influence of Aristotle’s Model of Communication

In conclusion, Aristotle’s model of communication is a timeless framework that still has relevance today. The three elements of ethos, logos, and pathos provide a solid guide for speakers to effectively communicate their message and persuade their audience. Ethos focuses on the credibility and trustworthiness of the speaker, logos emphasizes the use of logic and reasoning in the message, and pathos is the emotional appeal that creates a connection with the audience.

While Aristotle’s model of communication is widely recognized as a classic, other similar models have emerged in the field of communication. For instance, Berlo’s model of communication incorporates four elements, including source, message, channel, and receiver, and emphasizes the importance of feedback in the communication process (thus avoiding one of the weaknesses of Aristotle’s approach). Similarly, Shannon and Weaver’s model of communication focuses on the transmission of a message through a channel and highlights the role of noise and distortion in the communication process.

It’s also important to mention that Aristotle was not the first one to notice the power that language can have. The Sophists taught a lot about language, and even Aristotle’s mentor Plato talked extensively about language as well. However, it was Aristotle that contributed the most to the forming of rhetoric as a discipline. Aristotle’s model of communication remains an important foundation for understanding effective communication, and it continues to influence contemporary models and theories in the field of communication.

Aristotle’s Philosophy: Eudaimonia and Virtue Ethics

By Antonio Panovski BA Philosophy Antonio holds a BA in Philosophy from SS. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, North Macedonia. His main areas of interest are contemporary, as well as analytic philosophy, with a special focus on the epistemological aspect of them, although he’s currently thoroughly examining the philosophy of science. Besides writing, he loves cinema, music, and traveling.

Frequently Read Together

What is Rhetoric and Is it Good? Exploring Plato’s Sophist

Why Aristotle Hated Athenian Democracy

What Were Aristotle’s Four Cardinal Virtues?

- Writing Center

- Current Students

- Online Only Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Parents & Family

- Alumni & Friends

- Community & Business

- Student Life

- Video Introduction

- Become a Writing Assistant

- All Writers

- Graduate Students

- ELL Students

- Campus and Community

- Testimonials

- Encouraging Writing Center Use

- Incentives and Requirements

- Open Educational Resources

- How We Help

- Get to Know Us

- Conversation Partners Program

- Workshop Series

- Professors Talk Writing

- Computer Lab

- Starting a Writing Center

- A Note to Instructors

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Research Proposal

- Argument Essay

- Rhetorical Analysis

Aristotelian Argument

The Aristotelian or classical argument is a style of argument developed by the famous Greek philosopher and rhetorician, Aristotle. In this style of argument, your goal as a writer is to convince your audience of something. The goal is to use a series of strategies to persuade your audience to adopt your side of the issue. Although ethos, pathos, and logos play a role in any argument, this style of argument utilizes them in the most persuasive ways possible.

Of course, your professor may require some variations, but here is the basic format for an Aristotelian, or classical, argumentative essay:

- Introduce your issue. At the end of your introduction, most professors will ask you to present your thesis. The idea is to present your readers with your main point and then dig into it.

- Present your case by explaining the issue in detail and why something must be done or a way of thinking is not working. This will take place over several paragraphs.

- Address the opposition. Use a few paragraphs to explain the other side. Refute the opposition one point at a time.

- Provide your proof. After you address the other side, you’ll want to provide clear evidence that your side is the best side.

- Present your conclusion. In your conclusion, you should remind your readers of your main point or thesis and summarize the key points of your argument. If you are arguing for some kind of change, this is a good place to give your audience a call to action. Tell them what they could do to make a change.

Aristotelian Infographic

Introduction to Aristotelian Argument

The Aristotelian or classical argument is a style of argument developed by the famous Greek philosopher and rhetorician, Aristotle. In this style of argument, the writer’s goal is to be convincing and to persuade your audience to your side of the issue through a series of strategies.

Start here!

Before you begin, review your assignment and ask yourself questions about what you might want to write about.

Use prewriting activities, such as brainstorming or listing, to help develop ideas for topics and angles.

Do your research! Find credible sources to help you build your argument.

But there’s more! There are some important concepts you need to learn about.

Modes of Persuasion

Ethos=credibility

Pathos=emotions

Logos=logic

Know Your Audience!

When writing a classical or Aristotelian argument, think about how you are going to be convincing to your audience!

Things to remember along the way…

Clear thesis

Support thesis

Opposing views

Cite sources

Sample Aristotelian Argument

Now that you have had the chance to learn about Aristotle and a classical style of argument, it’s time to see what an Aristotelian argument might look like. Below, you’ll see a sample argumentative essay, written according to APA 7th edition guidelines, with a particular emphasis on Aristotelian elements.

Download here the sample paper. In the sample, the strategies and techniques the author used have been noted for you.

This content was originally created by Excelsior Online Writing Lab (OWL) and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-4.0 International License . You are free to use, adapt, and/or share this material as long as you properly attribute. Please keep this information on materials you use, adapt, and/or share for attribution purposes.

Contact Info

Kennesaw Campus 1000 Chastain Road Kennesaw, GA 30144

Marietta Campus 1100 South Marietta Pkwy Marietta, GA 30060

Campus Maps

Phone 470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

kennesaw.edu/info

Media Resources

Resources For

Related Links

- Financial Aid

- Degrees, Majors & Programs

- Job Opportunities

- Campus Security

- Global Education

- Sustainability

- Accessibility

470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

© 2024 Kennesaw State University. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Statement

- Accreditation

- Emergency Information

- Report a Concern

- Open Records

- Human Trafficking Notice

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, aristotelian argument.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

Learn how to employ the fundamental qualities of argument developed by Aristotle.

Aristotelian Argument is a deductive approach to argumentation that presents a thesis, an argument up front — somewhere in the introduction — and then endeavors to prove that point via deductive reasoning and exemplification .

Scholarly conversations regarding this style of argument can be traced to the 4th century BEC, including, especially Aristotle’s Rhetoric as well as the later works of Cicero and Quintilian.

Aristotelian argument is strategic choice for developing your arguments so long as

- your audience is open to argument based on logical reasoning and rhetorical reasoning .

- you are well versed on scholarly conversations about the topic .

Aristotelian Argument may also be referred to as Classical Argument or Traditional Argument

Related Concepts: Evidence ; Persuasion

Guide to Aristotelian Argument

Arguments come in all shapes and sizes. Hence, there’s no one way to compose an argument. Rather, you need to adjust how you shape your arguments based on your topic and rhetorical situation .

As always, you are wise to engage in rhetorical reasoning and rhetorical analysis to decide whether you should even respond to a call for an argument, much less invest the time in research your claims.

- Introduces the Topic

- Introduce Claims

- Appeal to Ethos & Persona to Establish an Appropriate Tone

- Appeal to Emotions

- Appeal to Logic

- Present Counterarguments

- Search for a Compromise and Call for a Higher Interest

- Speculate About Implications in Conclusions

1. Introduce the Topic

Before attempting to convince readers to agree with your position on a subject, you may need to educate them about the topic. In the introduction, explain the scope, complexity, and significance of the issue. You might want to mention the various approaches others have taken to solve the problem.

A discussion of background information and definition of terms can constitute a substantial part of your argument when you are writing for uninformed audiences, or it can constitute a minor part of your argument when you are writing for more informed audiences.

2. State Claims

Arguments are driven by claims. The claims can be about:

- Facts (Females are better mathematicians than males).

- Cause-and-Effect Relationships (Media violence creates a “culture of violence” in America).

- Solutions (Vegetarian diets are healthier and easier on the environment).

- Policies (Students who plagiarize should be expelled).

- Value (It’s unethical to hurt animals to conduct medical research).

As discussed below, claims are typically presented near the beginning of arguments, but they can also be implied or presented in the conclusions of the texts.

3. Appeal to Ethos & Persona to Establish an Appropriate Tone

The ethos the person making the argument has an effect on its success. If the writer, speaker, knowledge worker . . . has a reputation as a credible source, their argument appears more persuasive.

Additionally, the persona you project as a communicator influences whether readers, listeners, users . . . will read and consider of your argument. Your opening sentences generally establish the tone of your text and present to the reader a sense of your persona, both of which play a tremendous role in the overall persuasiveness of your argument. By evaluating how you define the problem, consider counterarguments, or marshal support for your claims, your readers will make inferences about your ethos and pathos.

Most academic readers are put off by zealous, emotional, or angry arguments. No matter how well you fine-tune the substance of your document, the tone that readers detect significantly influences how the message is perceived. If readers dislike the manner of your presentation, they may reject your facts, too. If you do not sound confident, your readers may doubt you. If your paper is loaded with spelling errors, you look foolish. No matter how solid your evidence is for a particular claim, your readers may not agree with you if you sound sarcastic, condescending, or intolerant.

Occasionally writers will hide behind a persona. Their reasons for hiding may be totally ethical.

4. Appeal to Emotions

Advertising seeks to invoke your emotions and capture your attention because advertisers know people make some decisions based on emotion rather than reason.

We all tend to perceive certain situations subjectively and passionately—particularly situations that involve us at a personal level. Even when we try to be objective, many of us still make decisions based on emotional impulses rather than sound reasoning. Those who recognize the power of emotional appeals sometimes twist them to sway others. Hitler is an obvious and extreme example. His dichotomizing—”You’re either for me or against me”—and bandwagon appeals—”Everyone knows the Jews are inferior to true Germans”—helped instigate one of the darkest chapters in human history.

Additional emotional appeals include:

- According to the EPA, global warming will raise sea levels).

- I should be allowed to take the test again because I had the flu the first time I took it).

- I wouldn’t vote for that man because he’s a womanizer).

Like arguments based solely on the persona of the author, arguments based solely on appeals to emotions usually lack the strength to be completely persuasive. Most modern, well-educated readers are quick to see through such manipulative attempts.

Emotional appeals can be used to persuade readers of the rightness of good causes or imperative action. For example, if you were writing an essay advocating a school-wide recycling program, you might paint an emotional, bleak picture of what our world will look like in 50 years if we don’t begin conserving now.

To achieve the non-threatening tone needed to diffuse emotional situations, avoid exaggerating your claims or using biased, emotional language. Also, avoid attacking your audience’s claims as exaggerated. Whenever you feel angry or defensive, take a deep breath and look for points in which you can agree with or understand your opponents. When you are really emotional about an issue, try to cool off enough to recognize where your language is loaded with explosive terms.

If the people for whom you are writing feel stress when you confront them with an emotionally charged issue and have already made up their minds firmly on the subject, you should try to interest such reluctant readers by suggesting that you have an innovative way of viewing the problem. Of course, this tactic is effective only when you can indeed follow through and be as original as possible in your treatment of the subject. Otherwise, your readers may reject your ideas because they recognize that you have misrepresented yourself.

5. Appeal to Logic

Critical readers expect you to develop your claims thoroughly. By examining the point you want to argue and the needs of your audience, you can determine whether it will be acceptable to rely only on anecdotal information and reasoning or whether you will also need to research facts and figures and include quotations from established sources. Personal observations have their place, say, in an argument about staying in athletic shape. But an anecdotal tone is unlikely to be persuasive when you address touchy social issues such as terrorism, gun control, pornography, or drugs.

Despite the forcefulness of your emotional appeals, you need to be rational if you hope to sway educated readers. Trained as critical readers, your teachers and college-educated peers expect you to provide evidence—that is, logical reasoning, personal observations, expert testimony, facts, and statistics. Like a judge who must decide a case based on the law rather than on intuition, your teachers want to see that you can analyze an issue as “objectively” as possible. As members of the academic community, they are usually more concerned with how you argue than what you argue for or against. Regardless of your position on an issue, they want to see that you can defend your position logically and with evidence.

6. Present Counter Arguments

At some point in your essay, you may need to present counterarguments to your claim(s). Essentially, whenever you think your readers are likely to disagree with you, you need to account for their concerns. Elaborating on counterarguments is particularly useful when you have an unusual claim or a skeptical audience. The strategy usually involves stating an opinion or argument that is contrary to your position, then proving to the best of your ability why your point of view still prevails.

When presenting and refuting counterarguments, remember that your readers do not expect your position to be valid 100 percent of the time. Few people think so simplistically. Despite the forced choices that clever rhetoricians present, few subjects that are worth arguing about can be reduced to yes, always, or no, never. When it is pertinent, therefore, you should concede any instances in which your opponents’ counterarguments have merit.

When considering likely counterarguments, you may want to elaborate on which of your opponent’s claims about the problem are correct. For example, if your roommate’s messiness is driving you crazy but you still want to live with him or her, stress that cleanliness is not the be-all-and-end-all of human life. Commend your roommate for helping you focus on your studies and express appreciation for all of the times that he or she has pitched in to clean up. And, of course, you would also want to admit to a few annoying habits of your own, such as taking thirty-minute showers or forgetting to pay the phone bill. Rather than issuing an ultimatum such as “Unless you start picking up after yourself and doing your fair share of the housework, I’m moving out,” you could say, “I realize that you view housekeeping as a less important activity than I do, but I need to let you know that I find your messiness to be highly stressful, and I’m wondering what kind of compromise we can make so we can continue living together.” Yes, this statement carries an implied threat, but note how this sentence is framed positively and minimalizes the emotional intensity inherent in the situation.

You will sabotage your hard-won persona as an informed and fair-minded thinker if you misrepresent your opponent’s counterarguments. For example, one rhetorical tactic that critical readers typically dislike is the straw man approach, in which a weak aspect of the opponent’s argument is equated with weakness of the argument as a whole. Unfortunately, American politicians tend to garner voter support by misrepresenting their opponent’s background and position on the issues. Before taking a straw man approach in an academic essay, you should remember that misrepresenting or satirizing opposing thoughts and feelings about your subject will probably alienate thoughtful readers.

7. Search for a Compromise and Call for a Higher Interest

Occasionally–particularly in emotionally stressful situations–authors extensively develop counterarguments. Some problems are so complex that there simply isn’t one solution to the problem. Under such circumstances, authors may seek a compromise under a call for a “higher interest.” For example, if you were writing an editorial in an Israeli newspaper that called for setting aside some of the Gaza territory for an independent Palestinian state, your introduction might sympathetically explore all of the Israeli blood that has been lost since the Gaza was seized in the Seven Day War. Then you could address the “eye-for-an-eye” mentality that has characterized this problem. Perhaps you could soften your readers’ thoughts about this problem by mentioning the number of Arabs who have died. Once you have developed your claim that some land should be set aside for the Palestinians, you might try to explore some of the “common ground” and call for Israelis and Arabs to seek out a higher goal expressed by both Jewish and Muslim peoples—that is, the desire for peace.

8. Speculate About Implications in Conclusions

Instead of merely repeating your original claim in the conclusion, you should end by trying to motivate your audience. Do not go out with a whimper and a boring restatement of your introduction. Instead, elaborate on the significant and broad implications of your argument. The wrap-up is an excellent place to utilize some emotional appeals.

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

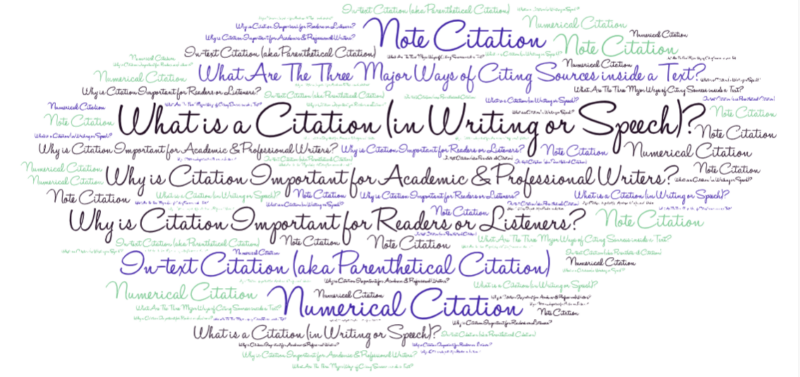

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Speech & Writing

Aristotle’s Model of Rhetoric and Contemporary Patterns of Argumentation: On Some Aristotelian Challenges

- First Online: 28 December 2023

Cite this chapter

- Giovanni Bombelli ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0486-9902 23

Part of the book series: Law and Philosophy Library ((LAPS,volume 144))

77 Accesses

The chapter focuses on the interdependence of the concepts of dialogue, law and truth in Aristotle’s model of rhetoric. Taking some aspects of the new rhetoric and of the argumentation theory of Perelman, Alexy and Habermas as a starting point, it will be clarified that the Aristotelian and ancient idea of rhetoric involved a completely different pattern of reasoning. Our analysis will focus on Aristotle’s paradigm, in particular the aspects of dialogue, truth and justice, which highlight the complexity of his model and show how his approach differs from the new model of argumentation theory. The revival of aspects of the Aristotelian approach within the contemporary philosophical-legal debate demonstrates the enduring relevance of Aristotle’s theoretical framework and invites its use to analyze patterns of reasoning in the public debate on issues as equity and climate change.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

For a general historical-theoretical framework and an introduction concerning the contemporay debate and perspectives on argumentation see, for instance, Handbook of Legal Reasoning and Argumentation ( 2018 ); Walton ( 2006 ), in particular (about the connection argumentation-dialogue) Chaps. 1 , 5 and 8 ; Piazza ( 2004 ); Atienza ( 2020 ) on the nexus between a general theory of argumentation and the legal argumentation (with reference to authors as Viehweg, Perelman, Toulmin and the “standard theory” developed by MacCormick and Alexy) and, more generally, Atienza and Ruiz Manero ( 2016 ).

About this question see Toulmin ( 2003 ), which can be considered one of the starting points of the discussion, and Spranzi ( 2011 ), p. 162, who synthesizes the developments of the debate and approaches: “These approaches can be arranged along a continuous spectrum according to two criteria: the relative importance they give to various forms of dialogue, and the aim of dialectical exchanges”; Rapp and Wagner ( 2013 ); furthermore van Eemeren ( 2013 ) moving from the perspective of the “pragma-dialectic” as widely presented in van Eemeren and Grootendorst ( 1992 ).

Moreover the developments proposed in Perelman ( 1976 ).

Spranzi ( 2011 ), especially Chaps. 2 – 3 about the Latin tradition and the revival of dialectic in the Renaissance. See also below about Aristotle’s framework.

Perelman ( 1979 ), Chap. 1 . The chapter offers a historical glance concerning the development of rhetoric in the Western thought. On Perelman’s perspective Piazza ( 2004 ), Chap. 2 .

Perelman ( 1979 ), the introduction by H. Zyskind. Zyskind provides a general survey on Perelman’s theory, with special regard to the idea of “new rhetoric” (XII about the structural relation action-language) and the comparison with Aristotle’s framework (X-XIII). See furthermore the Chaps. 10 – 11 concerning Perelman’s criticism of the continuity rhetoric-dialectic developed by the Stagirite: in other words, according to the Polish author within the Aristotelian framework dialectic cannot be considered in light of a continuum with rhetoric (I do not agree with this position).

Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca ( 1971 ), pp. 30–31. In a fundamental passage the authors point out: “The first[type of the audience] consists of the whole of mankind, or at least, of all normal adult persons: we shall refer to it as the universal audience. The second consists of the single interlocutor whom a speaker addresses in a dialogue. The third is the subject himself when he deliberates or gives himself reasons for his actions. We hasten to add that it is only when the interlocutor in a dialogue and the man debating with himself are regarded as an incarnation of the universal audience, that they can enjoy the philosophic privilege conferred to reason, by virtue of which argumentation addressed to them has often been assimilated to logical discourse. Each speaker’s universal audience, but it nonetheless remains true that, for each speaker at each moment, there exists an audience transcending all others, which cannot easily be forced within the bounds of a particular audience. On the other hand, the interlocutor in a dialogue or the person engaged in deliberation can be considered as a particular audience, with reactions that are known to us, or at least with characteristics we can study. Hence the primordial importance of the universal audience, as providing a norm for objective argumentation, because the other party to a dialogue and the person deliberating with himself can never amount to more than floating incarnations of this universal audience.” See also ibid ., pp. 32–35 concerning the concept of “universal audience”.

About the relation between the figure of the “dialogue” and the dialectical dimension see the remarks of H. Zyskind in Perelman ( 1979 ), p. XV and especially, for some clarifications by Perelman, pp. 73–81.

Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca ( 1971 ), pp. 36–37: see also pp. 38–39 and furthermore p. 56 concerning the “duty of dialogue” elaborated by the Italian philosopher Guido Calogero ( 2015 ). About this topic see also the conclusion of this contribution as regards the idea of “dialogue” within certain patterns of logic in the last century.

Perelman ( 1980 ), p. XI: “[The universal audience is] the principle of universality conceived in rhetorical terms”. According to Spranzi ( 2011 ), pp. 162–164 although Perelman “claims to take his inspiration from Aristotle’s dialectic, he calls his approach the “New Rhetoric” and distinguishes it from demonstration in a way that is reminiscent more of Aristotelian rhetoric than of Aristotelian dialectic.(…)Thus, dialectical arguments are only a special (and less interesting case) of the wider class of rhetorical arguments.” I do not agree with this reading.

In general, Spranzi points out that “Perelman’s avowedly Aristotelian project is dialectical only in the extended and generic sense of emphasizing invention, stressing the importance of argumentation, and considering the positions of others in building arguments. However, the New Rhetoric differs markedly from Aristotle’s position in the Topics in two respects. In the first place(…)Aristotle does not consider dialectical arguments as means of persuasion but as means of testing—and indirectly establishing—claims to knowledge.(…)Secondly, Perelman views ‘endoxa’ as instruments for appealing to the target audience and creating as wide a consensus as possible, rather than as necessary instruments for gaining the opponent’s assent, and thereby putting a rational end to criticisms.(…)It is thus not surprising that Perelman—like so many others—interprets Aristotle’s ‘endoxa’ as expressing “generally accepted opinions”(…), which in Aristotle’s Topics are only one of the possible sources of ‘endoxa’, and not even the most representative at that.(…)Perelman’s rhetorical approach can thus be compared to Agricola’s view of dialectic, which encompassed the argumentative and emotional aspects of rhetoric to the exclusion of style and openly sophistical arguments.”

Perelman ( 1980 ), p. vii ( Preface of the volume): “Legal reasoning is to rhetoric what mathematics is to formal logic”.

Habermas ( 1979 )[1976], p. 3 (for both the quotations; emphasis in the text); more widely Habermas ( 2007 ) especially p. 87 and p. 201 (about the Aristotelian references) and Habermas ( 1984 ). About this point for instance Rasmussen ( 1995 ), pp. 60–63 and Moon ( 2006 ), pp. 143–64 who starts from the comparison Habermas-Rawls.

White ( 2006 ) Part IV on Discursive Democracy , with the relevant contributions of Mark Warren, Kenneth Bynes and Simone Chambers.

Alexy ( 2010 ), p. 16 and ibidem chapter four dedicated to the discussion of Perelman’s theory. See also p. 287 ff. about the legal and, in general, the practical discourse (especially the remarks concerning the partial correspondence in the claim to correctness). Moreover, as regards the idea of “claim to correctness” see also, in the same volume, pp. 104–105 and pp. 107–108; for the references to Aristotle pp. 21, 23, 84, 88, 103, 156 and 159.

Among many comments, see for instance Lafont ( 2012 ) who in some way suggests the same “double interpretation” of the claim to correctness proposed in this contribution: as a logical principle and at a “substantial level”. Furthermore Bongiovanni et al. ( 2007 ).

Alexy ( 2019 ), p. 43.

Alexy ( 2019 ), p. 45. See also ff. about the distinction based on the first-order and second-order correctness and the connection between justice and legal certainty related to the “ideal dimension pentagon”.

Russell ( 2010 ) and furthermore in Stanford Encyclopedia ( 2006 ) “Type Theory”.

In particular Ayer ( 1970 ).

This approach could be discussed also in light of the question of “human rights”: Sieckmann ( 2007 ). In some way, a similar position characterizes Habermas’ perspective on argumentation. It seems to fluctuate between two sides (Habermas 1996 about the role of law). On the one hand, the German philosopher builds up a coherentist or “narrative” approach, which is also related to the idea of “reasonableness” à la Rawls (Habermas 1995 ;furthermore Alexy 2010 , Chap. 4 about the debate Habermas-Rawls). On the other hand, Habermas sometimes seems to make room for a sort of “ontological perspective”, that is to say, a model related to a referential level and to a “substantial justice”.

Aristotle and Pickard-Cambridge ( 1984a ). Please control this point Topics (Top.) II–VII and Aristotle and Rhys Roberts ( 1984 ) Rhetoric (Rhet.) II 18–24; furthermore Spranzi ( 2011 ), pp. 15–20, 30–38 and 90. In the current debate about this topic Perelman ( 1980 ), pp. 81, 88, 92 and 100; Perelman ( 1979 ), p. 58; Hart ( 1994 ) for the idea of common sense; Hintikka and Vandamme ( 1985 ), pp. 249 and ff.; Perelman and Olbrechts Tyteca ( 1971 ) §§ 21-24). The topics discussed below were also deepened by me in Bombelli ( 2013 ).

For an introduction Árnason, Raaflaub, and Wagner, The Greek Polis and the Invention of Democracy ( 2013 ).

The close relation between rhetoric and dialectic was emphasized within the humanistic movement and especially, for instance, by Rudolph Agricola on the basis of Aristotle’s framework: see Spranzi ( 2011 ), pp. 62–63 and Chaps. 3 – 4 ; van Eemeren ( 2013 ) in a “pragma-dialectic” direction oriented to the idea of “strategic manoeuvring”.

Aristotle and Jowett ( 1984 ) Politics (Pol.).

In the sense elaborated by Bertea ( 2019 ), especially Chap. 10 .

Rhet. I, Parts 2 and 3. Aristotle notoriously distinguishes three divisions of oratory: deliberative, forensic and speech of praise and blame (epideictic).

Rhet. I, especially Parts 2, 3 and 4.

Rhet. I, 1; I, 2 and the entire book II. For instance: “Rhetoric may be defined as the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion” ( Rhet. I, 2, 1355b 27-28, trans. Rhys Roberts). Notice that the relevance conferred to the emotive sphere highlights an important point: the rhetorical dimension cannot be interpreted as a formal scheme. It should be understood as a relation between orator and hearer involving a close connection among the argumentative, demonstrative and emotive level; see also Aristotle and Bywater ( 1984 ) Poetics (Poet.) I, 2.

In particular Rhet. , I, 2 and 4–8. After establishing the relation rhetoric-ethics-politics, Aristotle emphasizes the strong relation among the topics of political rhetoric and fundamental concepts like “happiness”, “utility”, “goodness”.

Spranzi ( 2011 ), p. 74 notes that the theme of the “power of truth” was common in the ancient world and that it can be found in Aristotle’s Rhetoric : “Rhetoric is useful because things that are true and things that are just have a natural tendency to prevail over their opposites, so that if the decisions of judges are not what they ought to be, the defeat must be due to the speakers themselves, and they must be blamed accordingly” ( Rhet , I, 1, 1355a 22–24, transl. Rhys Roberts).

Aristotle et al. ( 1984 ) (EN) VI, 8, 1142a; 1144a 6-9; 1145a 4-6.

Aristotle and Jenkinson ( 1984 ) Prior Analytics (APr.) I, 1, 24a 27-29.

Aristotle and Pickard-Cambridge ( 1984b ). Sophistical Refutation (SE). See also SE 2, 165b 7 ff .; more generally the paragraphs V–VIII.

See also Rhet. II, 18-26 wherein the distinction example-enthymeme highlights the role of the topoi in light of the theoretical circle among common/public knowledge and the rhetoric as a practice (on the concept of “enthymeme” Burnyeat 2015 ). This is the confirmation that Aristotle’s framework entails an embedded paradigm, which is the unescapable condition of the argumentative truth according to the epistemic continuity between rhetoric and dialectic established by the Stagirite (including the possible distinction aporetic-disputational dialectic: on this point, moving from Topics see Spranzi 2011 , introduction and Chap. 1 ; furthermore McAdon 2004 ).

For an analysis of the close circle polis -justice, in light of Aristotle’s framework, see Bombelli 2013 p. 297 ff., including the critical references. Furthermore Perelman ( 1979 ), p. XVIII.

EN , V, 5, 1134a 30-1134b 15: “For justice exists only between men whose mutual relations are governed by law; and law exists for men between whom there is injustice; for legal justice is the discrimination of the just and the unjust.(…)This is why we do not allow a man to rule, but law, because a man behaves thus in his own interests and becomes a tyrant.(…)(Justice or injustice of citizens are) according to law, and between people naturally subject to law (that is to say) people who have an equal share in ruling and being ruled.” (trans. Ross/Urmson, emphasis R/U)

See also Pol. III, 13, 1283b 42-1284a 3, trans. Jowett: “And a citizen is one who shares in governing and being governed. He differs under different forms of government, but in the best state he is one who is able and chooses to be governed and to govern with a view to the life of excellence”; see also Politics , III, 9, 1280b 5-13.

Pol. IV, 11, 1295a 25-1296a 19; on these categories Perelman ( 1980 ), p. 9 and Bombelli ( 2013 ), p. 305 and ff.

From this perspective the crucial role played by the figure of “dialogue” within Aristotle’s framework, including its communitarian horizon, can be compared to the “renaissance” of the dialogue in the philosophical and legal debate of the last century. It developed at least in two directions related to each other. On the one hand the so-called “philosophy of dialogue” or “dialogical movement”, which emphasized the “philosophical” aspect of dialogue dating back to Martin Buber’s intuitions and articulated, in different manner, by authors like Franz Rosenzweig, Ferdinand Ebner and the abovementioned Guido Calogero. On the other hand, the approach more closely focused on argumentation, which deals with the structurally dialogical-relational dimension of the discourse according to two theoretical orientations: the “formal dialogical logic” and the “informal dialogical logic”. The first one (i.e. the so-called dialogische Logik elaborated by the “Erlangen School”) moves from some of Paul Lorenzen’s works (Lorenzen 2010 , 1987 ; Lorenzen and Lorenz 1978 ) as well as Jakko Hintikka’s insights (related to the “Game Theoretical Semantics” encompassing the Aristotelian roots of his approach: Hintikka 1999 , 1997 , 1996 ; furthermore Hintikka and Vamdamme 1985 ) which deals with the structurally dialogical-relational dimension of the discourse. In particular, this orientation emphasizes the abstract structure of the dialogue in order to develop non-monological conceptual models. The “informal dialogical logic” has been developed by authors like Charles Hamblin ( 1970 , 1987 ), Douglas Walton with Erik Krabbe (Walton and Krabbe 1995 ) and Catarina Duthil Novaes ( 2021 , 2012 ): it aims at finding out rational criteria for understanding the ordinary argumentative speeches and their contexts.

In conclusion, some aspects of the contemporary philosophical-legal debate on argumentation seems to confirm the current theoretical usefulness of the Aristotelian perspective in order to rethink the logical conditions underlying the patterns of practical reasoning.

EN , V, 1137a31-1137b; see also Rhet. I, 13, 1374 a-b.

Also according to an historical perspective concerning the idea of equity underlying the tradition of common law and dating back to Hobbes’ theory of equity as well as to the experience of the English Courts like the Court of Chancery: Yntema ( 1966 ); Abosch ( 2013 ) and Klimchuk ( 2012 ).

Cf. Spranzi ( 2011 ), pp. 173–177, also starting from Aristotle: Lamb-Lane ( 2016 ).

Cf. Perelman ( 1980 ), p. 46 and ff. for a criticism).

Cf. about this point Perelman ( 1980 ) Chaps. 9 – 10 and 1979 , pp. 25–31, pp. 70–21, pp. 117–133; Spranzi ( 2011 ), pp. 164–166 against the pragma-dialectical approach.

Abosch, Yishaiya. 2013. An Exceptional Power: Equity in Thomas Hobbes’s Dialogue on the Common Law. Political Research Quarterly 66 (1): 18–31.

Article Google Scholar

Alexy, Robert. 2002. The Argument from Injustice: A Reply to Legal Positivism . Oxford : New York: Clarendon Press ; Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

———. 2010. A Theory of Legal Argumentation: The Theory of Rational Discourse as Theory of Legal Justification . 1st pbk. ed. Oxford (England); New York: Oxford University Press.

———. 2019. “Law’s Dual Nature” Ordines . Per un sapere interdisciplinare sulle istituzioni europee 1: 42–51.

Aristotle, and I. Bywater. 1984. Poetics. In The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation , ed. Jonathan Barnes, 2316–2340. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Aristotle, and A.J. Jenkinson. 1984. Prior Analytics. In The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation , ed. Jonathan Barnes, 114–166. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Aristotle, and B. Jowett. 1984. Politics. In The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation , ed. Jonathan Barnes, 1986–2129. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

Aristotle, and W.A. Pickard-Cambridge. 1984a. Topics. In The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation , ed. Jonathan Barnes, 167–277. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Aristotle, and W.A. Pickard-Cambridge. 1984b. Sophistical Refutations. In The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation , ed. Jonathan Barnes, 278–314. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Aristotle, and W. Rhys Roberts. 1984. Rhetoric. In The Complete Works of Aristotle. The Revised Oxford Translation , ed. Jonathan Barnes, 2152–2269. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Aristotle, W.D. Ross, and J.O. Urmson. 1984. Nicomachean Ethics. In The Complete Works of Aristotle. The Revised Oxford Translation , ed. Jonathan Barnes, 1729–1867. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Árnason, Jóhann Páll, Kurt A. Raaflaub, and Peter Wagner, eds. 2013. The Greek Polis and the Invention of Democracy: A Politico-Cultural Transformation and Its Interpretations. Ancient World : Comparative Histories . Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, A John wiley & Sons, Inc. Publication.

Atienza, Manuel. 2020. What Is the Theory Legal Argumentation For? International Journal for the Semiotics of Law - Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique 33 (1): 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-019-09669-6 .

Atienza, Manuel, and Juan Ruiz Manero. 2016. Las piezas del derecho: Teoría de los enunciados jurídicos . 4 a edición. Barcelona: Ariel.

Ayer, Alfred Jules. 1970. Language, Truth and Logic . Unabridged and Unaltered republ. of the 2. (1946) ed. New York, NY: Dover Publications.

Bertea, Stefano. 2019. A Theory of Legal Obligation . Cambridge, United Kingdom; New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press.

Bombelli, Giovanni. 2013. Occidente e “figure” comunitarie. I. Un ordine inquieto: koinonia e comunità radicata. Profili filosofico-giuridici . Napoli: Jovene.

Bongiovanni, Giorgio, Antonino Rotolo, and Corrado Roversi. 2007. The Claim to Correctness and Inferentialism: Alexy’s Theory of Practical Reason Reconsidered. In Law, Rights and Discourse: The Legal Philosophy of Robert Alexy , ed. George Pavlakos and Robert Alexy, 275–299. Portland, OR: Hart Publishing.

Burnyeat, Myles Fredric (2015) Enthymeme: Aristotle on the Logic of Persuasion. In Aristotle’s “Rhetoric”: Philosophical Essays , edited by David J. Furley and Alexander Nehamas, 3–56. Princeton University Press, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400872879-003 .

Calogero, Guido. 2015. Filosofia del dialogo . 1st ed. Brescia: Morcelliana.

Crutzen, Paul J., and Eugene F. Stoermer. 2000. Global Change Newsletter The Anthropocene. The Anthropocene 41: 17–18.

Duthil Novaes, Catarina. 2012. Formal Languages in Logic. A Philosophical and Cognitive Analysis . Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

———. 2021. The Dialogical Roots of Deduction. Historical, Cognitive and Philosophical Perspectives on Reasoning . Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press

Habermas, Jürgen. 1979. [1976]Communication and the Evolution of Society . Boston: Beacon Pr.

———. (1983) Moralbewusstsein Und Kommunikatives Handeln . 1. Aufl. Suhrkamp Taschenbuch Wissenschaft 422. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

———. (1984) Vorstudien Und Ergänzungen Zur Theorie Des Kommunikativen Handelns . 1. Aufl. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

———. 1995. Reconciliation Through the Public Use of Reason: Remarks on John Rawls’s Political Liberalism. The Journal of Philosophy 92 (3): 109–131.

———. 1996. Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy . In Studies in Contemporary German Social Thought . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, Habermas, Jürgen.

———. 2007. Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action. Repr . Cambridge: Polity.

Hamblin, C.L. 1970. Fallacies . London: Methuen.

———. 1987. Imperatives . New York, NY: Basil Blackwell.

Handbook of Legal Reasoning and Argumentation . 2018. New York, NY: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Hart, H.L.A. 1994. The Concept of Law . 2nd ed. Oxford: New York: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press.

Hintikka, Jaakko. 1996. The Principles of Mathematics Revisited . Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

———. 1997. What Was Aristotle Doing in His Early Logic, Anyway? A reply to Woods and Hansen. Synthese 241: 49.

———. 1999. On Aristotle’s Notion of Existence. The Review of Metaphysics 1999 (779): 805.

Hintikka, Jakko, and Fernand J. Vandamme, eds. 1985. Logic of Discovery and Logic of Discourse . New York: Ghent: Plenum Press; Communication and Cognition.

Jonas, Hans. 1984. The Imperative of Responsibility. In Search of an Ethics for the Technological Age . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Klimchuk, Dennis. 2012. Hobbes on Equity. In Hobbes and the Law , ed. David Dyzenhaus and Thomas Poole, 165–185. Cambridge, United Kingdom; New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Kripke, Saul A. 1980. Naming and Necessity . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lafont, Cristina. 2012. Correctness and Legitimacy in the Discourse Theory of Law. In Instituzionaled Reason: The Jurisprudence of Robert Alexy , ed. Matthias Klatt, 291–306. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lamb, Michael, and Melissa Lane. 2016. Aristotle on the Ethics of Communicating Climate Change. In Climate Justice in a Non-Ideal Worlds , ed. Clare Heyward and Dominic Roser, 229–254. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lorenzen, Paul. 1987. Constructive Philosophy . Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

———. 2010. Formal Logic . Place of publication not identified. Springer.

Lorenzen, Paul, and Kuno Lorenz, eds. 1978. Dialogische Logik . Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, (Abt. Verl.).

McAdon, Brad. 2004. Reconsidering the Intention or Purpose of Aristotle’s Rhetoric. Rhetoric Review 23 (3): 216–234. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327981rr2303 .

McLaughlin, Eugene, Ross Fergusson, Gordon Hughes, and Westmarland, eds. 2003. Restorative Justice: Critical Issues. Crime, Order and Social Control . London; Thousand Oaks: SAGE in Association with the Open University.

Moon, J. Donald. 2006. “Practical Discourse and Communicative Ethics.” In The Cambridge Companion to Habermas , edited by Stephen K. White, 143–164. Cambridge MA: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Perelman, Chaïm. 1976. Logique Juridique: Nouvelle Rhétorique. Méthodes Du Droit . Paris: Dalloz.

———. 1979. The New Rhetoric and the Humanities. Essays on Rhetoric and Its Applications. Synthese Library; vol. 140. Dordrecht, Holland; Boston: D. Reidel Pub. Co.

———. 1980. Justice, Law, and Argument. Essays on Moral and Legal Reasoning. Synthese Library; vol. 142. Dordrecht, Holland; Boston: Hingham, MA: D. Reidel Pub. Co. ; sold and distributed in the U.S.A. and Canada by Kluwer Boston.

Perelman, Chaim, and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca. 1971. The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation . Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Piazza, Francesca. 2004. Linguaggio, Persuasione e Verità: La Retorica Nel Novecento . 1a. ed. Studi Superiori ; Filosofia 477. Roma: Carocci,.

Rapp, Christof, and Tim Wagner. 2013. On Some Aristotelian Sources of Modern Argumentation Theory. Argumentation 27 (1): 7–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-012-9280-9 .

Rasmussen, David M. 1995. Reading Habermas . Cambridge: Blackwell.

Rawls, John. 1999. A Theory of Justice . Rev. ed. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Russell, Bertrand. 2010. Principles of Mathematics . Routledge Classics. London: Routledge, 2010.

Sieckmann, Jan. 2007. Human Rights and the Claim to Correctness in the Theory of Robert Alexy. In Law, Rights and Discourse: The Legal Philosophy of Robert Alexy , ed. George Pavlakos and Robert Alexy, 189–206. Portland, OR: Hart Publishing.

Spranzi, Marta. 2011. The Art of Dialectic Between Dialogue and Rhetoric: The Aristotelian Tradition . Controversies, vol. 9. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Pub. Co.

Tallacchini, Mariachiara. 1996. Diritto per la natura: ecologia e filosofia del diritto . Recta ratio 2, Testi 20. Torino: Giappichelli.

Tarski, Alfred. 1995. Introduction to Logic and to the Methodology of Deductive Sciences . New York: Dover Publications.

Toulmin, Stephen. 2003. The Uses of Argument . Updated edn. Cambridge, U.K.; New York: Cambridge University Press.

“Type Theory”. In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, February 8, 2006.

van Eemeren, F.H., and R. Grootendorst. 1992. Argumentation, Communication, and Fallacies: A Pragma-Dialectical Perspective . Hillsdale, N.J: L. Erlbaum.

van Eemeren, Frans H. 2013. In What Sense Do Modern Argumentation Theories Relate to Aristotle? The Case of Pragma-Dialectics. Argumentation 27 (1): 49–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-012-9277-4 .

Walton, Douglas N. 2006. Fundamentals of Critical Argumentation . Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Walton, Douglas N., and E.C. W. Krabbe. 1995. Commitment in Dialogue: Basic Concepts of Interpersonal Reasoning . SUNY Series in Logic and Language. Albany: State University of New York Press.

White, Stephen K. 2006. The Cambridge Companion to Habermas . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://cco.cambridge.org/login2?dest=/book?id=ccol052144120x_CCOL052144120X .

Yntema, Hessel E. 1966. Equity in the Civil Law and the Common Law. The American Journal of Comparative Law 15 (1/2): 60–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/838860 .

Zehr, Howard. 2005. Changing Lenses: A New Focus for Crime and Justice . 3rd ed. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Law, Catholic University of Milan, Milan, Italy

Giovanni Bombelli

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Giovanni Bombelli .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Liesbeth Huppes-Cluysenaer

Faculdade de Direito de Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo, Brazil

Nuno M.M.S. Coelho

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Bombelli, G. (2023). Aristotle’s Model of Rhetoric and Contemporary Patterns of Argumentation: On Some Aristotelian Challenges. In: Huppes-Cluysenaer, L., Coelho, N.M. (eds) Aristotle on Truth, Dialogue, Justice and Decision. Law and Philosophy Library, vol 144. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-45485-1_9

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-45485-1_9

Published : 28 December 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-45484-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-45485-1

eBook Packages : Law and Criminology Law and Criminology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Memberships

Aristotle Model of Communication

Aristotle Model of Communication: this article provides a practical explanation of the Aristotle Model of Communication . The article contains the definition of the Aristotle Model of Communication, and example of the diagram and practical tips. Enjoy reading!

What is Aristotle Model of Communication?

It was Aristotle who first proposed and wrote about a unique model of communication.

Today, his model is referred to as the Aristotle Model of Communication. The great philosopher Aristotle already created this linear model before 300 BC, placing more emphasis on public speaking than on interpersonal communication.

The simple model is presented in a diagram and is still widely used in preparing seminars, lectures and speeches to this day.

Aristotle model of communication diagram

The Aristotle Model of Communication diagram can roughly be divided into five elements. The speaker is the most important element, making this model a speaker-oriented model.

Figure 1 – Aristotle model of communication diagram

Aristotle Model of Communication: the Role of the Speaker

According to the Aristotle Model of Communication, the speaker is the main figure in communication. This person is fully responsible for all communication. In this model of communication, it is important that the speaker selects his words carefully.

He or she must analyse his audience and prepare his speech accordingly. At the same time, he or she should assume the right body language, as well as ensuring proper eye contact and voice modulations.

In order to entice the audience, blank expressions, confused looks, and monotonous speech must be avoided at all times. The audience must believe in the speaker’s ability to easily put his money where his mouth is.

A politician (the speaker) gives a speech on a market square during an election campaign (the occasion). His goal is the win the votes of the citizens (the audience) present as well as those of the citizens potentially watching the speech on TV.

The people will vote (the effect) for the politician if they believe in his views. At the same time, the way in which he presents his story is crucial in convincing his audience.

The politician talks about his party’s standpoints and will probably be familiar with his audience. In other situations, it would be more suitable to actively research the audience in advance and determine their potential viewpoints or opinions.

The Rhetorical Triangle

The rhetorical triangle is essentially a method to organise and distinguish the three elements of rhetoric. The rhetorical triangle consists of three convincing strategies, to be used in direct communication situations.

Aristotle did not use a triangle himself in the Aristotle Model of Communication, but effectively described the three modes of persuasion , namely logos, pathos, and ethos.

These modes of persuasion always influence each other during conversations in which arguments are shared back and forth, but also in one-way communication, such as during speeches.

Figure 2 – Aristotle’s Triangle of Reference

Ethos is about the writer or speaker’s credibility and degree of authority, especially in relation to the subject at hand. A doctor’s ethos is the result of years of study and training. Due to his qualifications, a doctor’s words involve a significant degree of authority.

One’s ethos can be damaged in the blink of an eye, however. For example, the reputable politician may be found out when corruption scandals come to light and his private life turns out to be in complete contrast with his political standpoints. Tips for building ethos in communication:

- Use words that suit the target group

- Keep communication professional

- Conduct research before words are presented as facts

- Use recommendations from qualified experts

- Make logical connections and avoid fallacies

The literal translation of pathos is emotion. In the rhetoric, pathos refers to the audience and the way in which they react to the speaker’s message, the center in the Aristotle Model of Communication.

The idea behind pathos is that the audience must feel that they are communicated with. In certain situations, they want to feel more confident, in others more sad, angry, or emotional.

Before and during the Second World War, Adolf Hitler gave many speeches in front of tens of thousands of people. His words and particular pronunciation made his audience feel attracted to him. Pathos, emotion, can therefore also be abused. For example, people may become anxious as a result of the false consequences of not buying a product presented in the sales world.

The question of whether emotions may be manipulated in sales strategies is a sensitive one. When collecting money for charities, this is somewhat socially acceptable.

However, when selling products or services, many people will express their doubts. Nevertheless, capitalising on pathos can be very effective.

Tips for effectively addressing emotions:

- People’s involvement is stimulated by humour. Always keep different types of humour in mind, though

- Use images or other visual materials to evoke strong emotions

- Pay attention to the intonation and tempo of one’s voice in order to elicit enthusiasm or anxiety

The direct translation of logos is logic, but in rhetoric it more broadly refers to the speaker’s message and more specifically the facts, statements, and other elements that comprise the argument.

According to the Aristotle model of communication, logos is the most important part of one’s argument. For this reason, it is crucial that sales talks always emphasise this particular element.

The appeal to logic also means that paragraphs and arguments must be properly ordered. Facts, statistics and logical reasoning are especially important here. When analysing logos, always ask yourself:

- What is the context? What conditions are relevant?

- What are the potential counter-arguments?

- Is there any evidence that supports my argument? Always mention this

- Do I correctly avoid generalisations and am I being specific enough?

The Complete Communication Skills Master Class for Life More information

An Example of Proper Use of Rhetoric

One man who understood rhetoric very well and applied it effectively was Steve Jobs , founder of Pixar Animation, NeXT, and Apple. He also applied the Aristotle model of communication effectively. This business guru stands head and shoulders above others of his generation in terms of communication techniques.

Much research has been conducted into the ways in which he used to communicate a constant series of messages and themes about his company’s products and his vision of the future.

Communication experts especially distinguish Steve Jobs’ ethos. His degree of ethos, or credibility, had a major influence on how he used logos and pathos.

If ethos was low, Steve Jobs would use high levels of pathos and low levels of logos. If ethos was high, he would use low levels of pathos and high levels of logos.

In addition to effective use of the rhetorical triangle, Jobs also used a mix of rhetorical strategies such as repetition, re-stirring of discussions to suit his vision and goals, and amplification. Amplification refers to a literary technique in which the user enhances a series of words by adding information to increase their value and comprehensibility.

Criticism of Aristotle Model of Communication

Despite the fact that at first glance there does not seem much wrong with Aristotle’s communication model, there are important points of criticism of the model.

The main point of communication is that the model considers a directional process, from speaker to receiver.

In reality, it is a dynamic process in which both the speaker and receiver are active. Evidence for this can be found, for example, in the technology of eavesdropping.

Because of the above, the model is useless in many situations because the feedback is not included.

Now it’s your turn

What do you think? Are you familiar with the Aristotle model of communication? How do you think you can use this information to improve your communication skills? Do you have any additional tips for effective communication? Do you have any other suggestions or additions?

Share your experience and knowledge in the comments box below.

More information

- Kallendorf, C., & Kallendorf, C. (1985). The figures of speech, ethos, and Aristotle: Notes toward a rhetoric of business communication . The Journal of Business Communication (1973), 22(1), 35-50.

- Griffin, E. M. (2006). A first look at communication theory . McGraw-Hill .

- Braet, A. C. (1992). Ethos, pathos and logos in Aristotle’s Rhetoric: A re-examination . Argumentation, 6(3), 307-320.

How to cite this article: Janse, B. (2018). Aristotle Model of Communication . Retrieved [insert date] from Toolshero: https://www.toolshero.com/communication-methods/aristotle-model-of-communication/

Original publication date: 10/07/2018 | Last update: 11/08/2023

Add a link to this page on your website: <a href=”https://www.toolshero.com/communication-methods/aristotle-model-of-communication/a>Toolshero: Aristotle Model of Communication</a>

Did you find this article interesting?

Your rating is more than welcome or share this article via Social media!

Average rating 4.8 / 5. Vote count: 19

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Ben Janse is a young professional working at ToolsHero as Content Manager. He is also an International Business student at Rotterdam Business School where he focusses on analyzing and developing management models. Thanks to his theoretical and practical knowledge, he knows how to distinguish main- and side issues and to make the essence of each article clearly visible.

Related ARTICLES

Ladder of Abstraction (Hayakawa)

Dialogue Mapping by Jeff Conklin: a Summary

7 C’s of Communication Theory

Social Intelligence (SI) explained

Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS)

Impression Management Theory by Erving Goffman

Also interesting.

David Berlo’s SMCR Model of Communication explained

Storytelling Method: Basics and Steps

Core Quality Quadrant Model explained

2 responses to “aristotle model of communication”.

It would be great if we find Criticism of this model.

Yes we do have some criticisms of this model 1. There is no concept of feedback, it is one way from the speaker to the audience. 2. There is no concept of communication failures like noise and barriers. 3. This model can only be used in public speaking.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

BOOST YOUR SKILLS

Toolshero supports people worldwide ( 10+ million visitors from 100+ countries ) to empower themselves through an easily accessible and high-quality learning platform for personal and professional development.

By making access to scientific knowledge simple and affordable, self-development becomes attainable for everyone, including you! Join our learning platform and boost your skills with Toolshero.

POPULAR TOPICS

- Change Management

- Marketing Theories

- Problem Solving Theories

- Psychology Theories

ABOUT TOOLSHERO

- Free Toolshero e-book

- Memberships & Pricing

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Aristotle’s Natural Philosophy