Since his death in 2003, the Chilean novelist Roberto Bolaño has become one of the more colorful gods in the pantheon of international literary myth. (Who can forget the time he impregnated a dragon using nothing but the power of his neglected avant-gardism?) My favorite episode of his biographical legend is the part where, at the age of nearly 40, having spent his wild-haired youth as an experimental poet obscurely chasing revolutions (political and aesthetic) all over Latin America, he finally decided it was time to hang up his spurs (or whatever revolutionaries had worn in the seventies) and try, with the air of a man resigning himself to becoming a vacuum salesman, to earn a stable living by writing fiction. This is funny because Bolaño’s fiction—dreamy novellas in which air-force pilots skywrite opaque poetry and priests tutor despots in Marxism—is perhaps the least commercially viable body of literature ever written for the alleged purpose of making money. His novelistic skill-set seems designed to repel consumers. He has an apparently life-threatening allergy to cuteness, fictional convention, and reader-enabling shortcuts. He seems personally offended by the artifice of narrative closure; although he’s addicted to detective plots, he employs them almost purely as philosophical exercises, often abandoning them halfway through. He loves (like Borges) to invent elaborate bibliographies for fictional authors, which occasionally creates the sensation that you’re reading a card catalogue instead of a novel. He follows his restless talent down every available rabbit hole of improvisation, no matter how dark and unpromising. Single sentences stretch on for pages, obsessively sifting the most minor gradations. Surreal metaphors bloom without warning: “It was raining in the quadrangle, and the quadrangular sky looked like the grimace of a robot or a god made in our own likeness … the grass and earth seemed to talk, no, not talk, argue, their incomprehensible words like crystallized spiderwebs or the briefest crystallized vomitings.” This all adds up, indisputably, to great literature—at his best, Bolaño strikes a new kind of balance between aim (quests, escapes, investigations) and aimlessness (dreams, description, metaphorical riffing), in which the aimlessness is so energetic and oddly urgent it steps up as a whole new species of purpose. But in what world would it ever possibly sell?

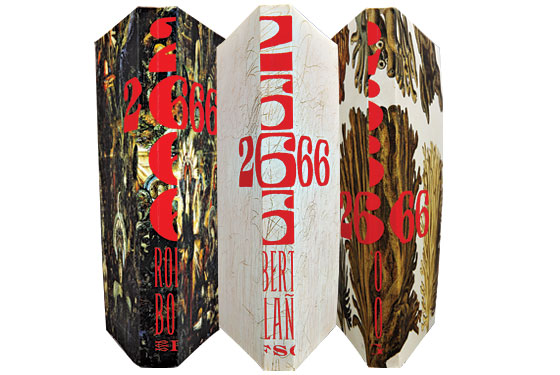

Well, apparently in this one. The newest entry in Bolaño’s legendary oeuvre is the enormous, posthumous, ambiguously complete, inscrutably titled novel 2666 —which arrives omni-buzzed and hyperdesigned, poised to be the most fashionable literary blockbuster of the holiday season.

Having just spent the equivalent of a full workweek crawling through the book, however, I’m having trouble envisioning it as the hot Christmas item some people might expect. Its 893 pages are indisputably brilliant, but they are not, by any definition, brisk—they’re tall, crowded, brutal, dense. In fact, one possible explanation of the mysterious title is that it would take any normal author 2,666 pages to convey what Bolaño manages to convey (or half-convey, or almost possibly begin to suggest he might convey) in just under 900. Reading 2666 demands a degree of sustained artistic communion that strikes me as deeply old-fashioned, practically Victorian. There are underwhelming patches, tonal dead spots, and even stretches that border on self-parody. The opening chapter is, at times, prohibitively dry. (It took me a second reading, immediately after finishing the book, to pick up much of its resonance.) Even when Bolaño is absolutely on fire, hypnotizing you with his dirty magic (which is often), the pages don’t fly by—if anything, they drag you right down into the dense fudgy core of time, where moments congeal into minutes, minutes into hours, and hours into eons.

Plot summary, I’m afraid, is futile. Bolaño has a lyric poet’s feel for narrative logic, and 2666 is a modular epic—a novel built out of five linked novellas, each of which is itself a collage of endless stand-alone parts: riffs, nightmares, set pieces, monologues, dead ends, stories within stories, descriptive flourishes. It begins with four literary critics—three Europeans and an Englishwoman, embroiled in a fierce international love quadrangle—who’ve built academic careers based entirely on their obsession with a vanished German novelist, the absurdly named Benno von Archimboldi. On a tip, the scholars go searching for Archimboldi in Santa Teresa, a dystopic Mexican boomtown (“equal parts lost cemetery and garbage dump”) near the U.S. border, where, they soon discover, hundreds of women have recently been kidnapped, raped, and murdered. These mysterious killings, based on a real-life crime wave that broke out in Ciudad Juárez in the nineties, become the center of 2666 , around which Bolaño mobilizes his small army of cosmopolitan protagonists: a Chilean professor who’s terrified that his teenage daughter will be the next victim; a black American journalist assigned, on a fluke, to cover a boxing match in Santa Teresa; and the elusive Archimboldi himself, drawn toward the murders at the end of his life by a surprising family connection.

The heart of 2666 is its fourth and longest section, called simply “The Part About the Crimes.” It is, flat out, one of the best stretches of fiction I’ve ever read. I broke my pencil several times writing catatonically enthusiastic marginalia. Bolaño takes the crimes on directly, one by one, compiling a brutal, almost journalistic catalogue of the murdered women. Although he’s clearly outraged by the culture of misogyny, exploitation, and indifference that enables the killing, he refuses to load the fictional dice. He humanizes not only the women and their families but the corrupt police and even the murder suspects. It’s a perfect fusion of subject and method: The real-world horror anchors Bolaño’s dreamy aesthetic, producing an impossibly powerful hybrid of political anger and sophisticated art.

Bolaño’s novellas and short stories are often perfect exercises in pacing and tone. 2666 is, as the book itself admits, very clearly not that. Bolaño was working on the classic “loose baggy monster” plan of the novel, aiming not for a tidy, fussy, impeccable minor work but for a heroic, encyclopedic, reckless, god-awful brilliant mess. He wanted, as his Chilean professor puts it, not Bartleby the Scrivener but Moby-Dick —one of the world’s “great, imperfect, torrential works” in which the writer engages in “real combat … against that something, that something that terrifies us all.” That something was, at least partly for Bolaño, death. He was apparently not quite finished revising 2666 when he died, at 50, of liver failure—a real-life tragedy that strikes me, on a purely artistic level, as somehow appropriate. 2666 is Bolaño’s everything book: It aspires to say all he had to say about his career, his central obsessions, and his geographical touchstones (Chile, Mexico, Spain, Germany). His death, in the last moments of its creation, applies the final indeterminate Bolañesco touch: mystery, openness, imperfection—a simultaneous promise of everything and of nothing.

See Also The best passages, the five-page sentence, and more on 2666 from Vulture .

2666 By Roberto Bolaño. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. $30.

Most viewed

- Andrew Huberman’s Mechanisms of Control

- The Boeing Nosedive

- Cinematrix No. 28: April 3, 2024

- The Case for Marrying an Older Man

- What to Know About the Latest Student-Loan Forgiveness Plans

- Shōgun Recap: Family Matters

What is your email?

This email will be used to sign into all New York sites. By submitting your email, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy and to receive email correspondence from us.

Sign In To Continue Reading

Create your free account.

Password must be at least 8 characters and contain:

- Lower case letters (a-z)

- Upper case letters (A-Z)

- Numbers (0-9)

- Special Characters (!@#$%^&*)

As part of your account, you’ll receive occasional updates and offers from New York , which you can opt out of anytime.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

2666 by Roberto Bolaño

T he posthumous appearance of Bolaño's mammoth magnum opus caused one reviewer to proclaim that it "makes difficulty sexy". In fact it concerns a pair of rival literary critics who find sex difficult, one of whom "could screw for six hours (without coming) thanks to his bibliography" while the other "finished half dead sheerly on the basis of strength and force of will". It takes some force of will to make it through this sequence of five separate, tangentially linked novels, the recurring thread of which is the identity of a reclusive author named Benno von Archimboldi, whose impenetrable books have become cult objects among academics. The mysterious author may or may not be related to a series of sadistic killings in the Mexican border town of Santa Teresa, where an investigative journalist known as Fate has a curious conversation with a hotel clerk about Michael Jackson. In the porter's opinion, "Michael knows things the rest of us don't". Could it be that the King of Pop has taken the secret of Bolano's fathomless novel to the grave?

- Roberto Bolaño

Most viewed

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

Google Rating

National Book Critics Circle Winner

by Roberto Bolaño & translated by Natasha Wimmer ‧ RELEASE DATE: Nov. 1, 2008

Unquestionably the finest novel of the present century—and we may be saying the same thing 92 years from now.

Life and art, death and transfiguration reverberate with protean intensity in the late (1953–2003) Chilean author’s final work: a mystery and quest novel of unparalleled richness.

Published posthumously in a single volume, despite its author’s instruction that it appear as five distinct novels, it’s a symphonic envisioning of moral and societal collapse, which begins with a mordantly amusing account (“The Part About the Critics”) of the efforts of four literary scholars to discover the obscured personal history and unknown present whereabouts of German novelist Benno von Archimboldi, an itinerant recluse rumored to be a likely Nobel laureate. Their searches lead them to northern Mexico, in a desert area notorious for the unsolved murders of hundreds of Mexican women presumably seeking freedom by crossing the U.S. border. In the novel’s second book, a Spanish academic (Amalfitano) now living in Mexico fears a similar fate threatens his beautiful daughter Rosa. It’s followed by the story of a black American journalist whom Rosa encounters, in a subplot only imperfectly related to the main narrative. Then, in “The Part About the Crimes,” the stories of the murdered women and various people in their lives (which echo much of the content of Bolaño’s other late mega-novel The Savage Detectives ) lead to a police investigation that gradually focuses on the fugitive Archimboldi. Finally, “The Part About Archimboldi” introduces the figure of Hans Reiter, an artistically inclined young German growing up in Hitler’s shadow, living what amounts to an allegorical representation of German culture in extremis , and experiencing transformations that will send him halfway around the world; bring him literary success, consuming love and intolerable loss; and culminate in a destiny best understood by Reiter’s weary, similarly bereaved and burdened sister Lotte: “He’s stopped existing.” Bolaño’s gripping, increasingly astonishing fiction echoes the world-encompassing masterpieces of Stendhal, Mann, Grass, Pynchon and García Márquez, in a consummate display of literary virtuosity powered by an emotional thrust that can rip your heart out.

Pub Date: Nov. 1, 2008

ISBN: 978-0-374-10014-8

Page Count: 912

Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Review Posted Online: May 19, 2010

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Sept. 15, 2008

LITERARY FICTION

Share your opinion of this book

More by Roberto Bolaño

BOOK REVIEW

by Roberto Bolaño ; translated by Natasha Wimmer

HOUSE OF LEAVES

by Mark Z. Danielewski ‧ RELEASE DATE: March 6, 2000

The story's very ambiguity steadily feeds its mysteriousness and power, and Danielewski's mastery of postmodernist and...

An amazingly intricate and ambitious first novel - ten years in the making - that puts an engrossing new spin on the traditional haunted-house tale.

Texts within texts, preceded by intriguing introductory material and followed by 150 pages of appendices and related "documents" and photographs, tell the story of a mysterious old house in a Virginia suburb inhabited by esteemed photographer-filmmaker Will Navidson, his companion Karen Green (an ex-fashion model), and their young children Daisy and Chad. The record of their experiences therein is preserved in Will's film The Davidson Record - which is the subject of an unpublished manuscript left behind by a (possibly insane) old man, Frank Zampano - which falls into the possession of Johnny Truant, a drifter who has survived an abusive childhood and the perverse possessiveness of his mad mother (who is institutionalized). As Johnny reads Zampano's manuscript, he adds his own (autobiographical) annotations to the scholarly ones that already adorn and clutter the text (a trick perhaps influenced by David Foster Wallace's Infinite Jest ) - and begins experiencing panic attacks and episodes of disorientation that echo with ominous precision the content of Davidson's film (their house's interior proves, "impossibly," to be larger than its exterior; previously unnoticed doors and corridors extend inward inexplicably, and swallow up or traumatize all who dare to "explore" their recesses). Danielewski skillfully manipulates the reader's expectations and fears, employing ingeniously skewed typography, and throwing out hints that the house's apparent malevolence may be related to the history of the Jamestown colony, or to Davidson's Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of a dying Vietnamese child stalked by a waiting vulture. Or, as "some critics [have suggested,] the house's mutations reflect the psychology of anyone who enters it."

Pub Date: March 6, 2000

ISBN: 0-375-70376-4

Page Count: 704

Publisher: Pantheon

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Feb. 1, 2000

More by Mark Z. Danielewski

by Mark Z. Danielewski

Kirkus Reviews' Best Books Of 2019

New York Times Bestseller

IndieBound Bestseller

NORMAL PEOPLE

by Sally Rooney ‧ RELEASE DATE: April 16, 2019

Absolutely enthralling. Read it.

A young Irish couple gets together, splits up, gets together, splits up—sorry, can't tell you how it ends!

Irish writer Rooney has made a trans-Atlantic splash since publishing her first novel, Conversations With Friends , in 2017. Her second has already won the Costa Novel Award, among other honors, since it was published in Ireland and Britain last year. In outline it's a simple story, but Rooney tells it with bravura intelligence, wit, and delicacy. Connell Waldron and Marianne Sheridan are classmates in the small Irish town of Carricklea, where his mother works for her family as a cleaner. It's 2011, after the financial crisis, which hovers around the edges of the book like a ghost. Connell is popular in school, good at soccer, and nice; Marianne is strange and friendless. They're the smartest kids in their class, and they forge an intimacy when Connell picks his mother up from Marianne's house. Soon they're having sex, but Connell doesn't want anyone to know and Marianne doesn't mind; either she really doesn't care, or it's all she thinks she deserves. Or both. Though one time when she's forced into a social situation with some of their classmates, she briefly fantasizes about what would happen if she revealed their connection: "How much terrifying and bewildering status would accrue to her in this one moment, how destabilising it would be, how destructive." When they both move to Dublin for Trinity College, their positions are swapped: Marianne now seems electric and in-demand while Connell feels adrift in this unfamiliar environment. Rooney's genius lies in her ability to track her characters' subtle shifts in power, both within themselves and in relation to each other, and the ways they do and don't know each other; they both feel most like themselves when they're together, but they still have disastrous failures of communication. "Sorry about last night," Marianne says to Connell in February 2012. Then Rooney elaborates: "She tries to pronounce this in a way that communicates several things: apology, painful embarrassment, some additional pained embarrassment that serves to ironise and dilute the painful kind, a sense that she knows she will be forgiven or is already, a desire not to 'make a big deal.' " Then: "Forget about it, he says." Rooney precisely articulates everything that's going on below the surface; there's humor and insight here as well as the pleasure of getting to know two prickly, complicated people as they try to figure out who they are and who they want to become.

Pub Date: April 16, 2019

ISBN: 978-1-984-82217-8

Page Count: 288

Publisher: Hogarth

Review Posted Online: Feb. 17, 2019

Kirkus Reviews Issue: March 1, 2019

More by Sally Rooney

by Sally Rooney

More About This Book

PERSPECTIVES

SEEN & HEARD

BOOK TO SCREEN

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

Lines in the Sand

WATCH OWN APP

Download the Watch OWN app and access OWN anytime, anywhere. Watch full episodes and live stream OWN whenever and wherever you want. The Watch OWN app is free and available to you as part of your OWN subscription through a participating TV provider.

NEWSLETTERS

SIGN UP FOR NEWSLETTERS TODAY AND ENJOY THE BENEFITS.

- Stay up to date with the latest trends that matter to you most.

- Have top-notch advice and tips delivered directly to you.

- Be in the know on current and upcoming trends.

OPRAH IS A REGISTERED TRADEMARK OF HARPO, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED © 2024 HARPO PRODUCTIONS, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. OWN: OPRAH WINFREY NETWORK

2666 by Roberto Bolaño

general information | review summaries | our review | links | about the author

- Return to top of the page -

A+ : nearly perfect

See our review for fuller assessment.

Review Consensus : Very impressed. From the Reviews : "You could say 2666 is the epic novel that Borges never wrote. Though the book is often quite maddening -- in the way it's so plethoric, constantly introducing new characters and dropping others, never having a main protagonist, choosing to leave so much unexplained, proceeding like a dream -- it also always has a power to command the reader, to absorb and mystify you. And however much the novel circles around uncontrollable evil, social disorder and the questionable value of literature itself, Bolaño's true preoccupation remains always, unmistakeably, the search for love and meaning in life. A masterpiece then ? Maybe. Certainly not nothing." - David Sexton, Evening Standard "Pas un roman, mais un bréviaire pour les temps présents, un immense manuel de deuil et de mélancolie. Un De profundis baroque et énigmatique, le crime passionnel d'un homme mort par et pour la littérature, qui laisse aux vivants ce livre, comme une armée vaincue fait retraite en br�lant la terre derrière elle. (...) Ce serait un livre moderne, indifférent à la modernité. (...) Ce serait inoubliable." - Olivier Mony, Le Figaro "Bolaño�s most audacious performance. (...) 2666 is less fun than The Savage Detectives but it is a summative work -- a grand recapitulation of the author�s main concerns and motifs. (...) Bolaño is an uncompromising writer. He alternates between brisk vignettes and passages of meandering opulence. His prose is short on adjectives and sometimes deliberately infelicitous but it can also beguile. It is studded with aphorisms, many of them calculated to invite passionate disagreement. Deranged similes are a hallmark of his writing" - Henry Hitchings, Financial Times "Only the final book, a compelling mittel-European picaresque of Archimboldi�s rise from Prussian peasant to an author sought by the Nobel committee, brings out Bolaño�s gift for intense, erotically charged encounters, subtly nuanced relationships and assured, complex plotting." - James Urquhart, Financial Times " 2666 ist ein k�hnes, wildes, hochexperimentelles Unget�m von einem Roman. In der vorliegenden Form keineswegs perfekt -- besonders der zweite, dritte und fünfte Teil haben große Längen --, ist er doch immer noch so ziemlich allem überlegen, was in den letzten Jahren veröffentlicht wurde. 2666 , das kann man getrost voraussagen, wird für die Literatur Südamerikas so prägend sein wie in der vorangegangenen Generation die Hauptwerke von Gabriel García Márquez, Mario Vargas Llosa und Julio Cortázar." - Daniel Kehlmann, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung "It is complete, achieved and satisfying, though there is an unignorable urgency to it that is truly mesmerizing and breathtaking (.....) Although existentially unsettling, 2666 is also funny, very funny, and oddly reassuring; no run-of-the-mill apocalypticist, Bolaño maintains a belief in art, in a "third leg," even though so much conspires against it, like time and the ways it distorts and disintegrates everything. 2666 holds an "unquiet mirror" up to hell and stuns with its brilliance. It is a heroic achievement, a modern epic -- a masterpiece." - J.S.Goldbach, Globe & Mail "It takes some force of will to make it through this sequence of five separate, tangentially linked novels" - Alfred Hickling, The Guardian "Naturally in such a work there are boring passages, irrelevant passages, highly indulgent passages, places where you can clearly see Bolaño pushing his fiction writer�s confidence game too far; yet, the whole of 2666 is such a masterly and awe-inspiring performance that the reader settles into and clings to it as one settles for the world." - Vivek Narayanan, The Hindu "Roberto Bolaño's 2666 is a difficult experience to shake off; it lingers in the unconscious like a sizzling psychotropic for days or weeks after reading. It is a novel both prodigious in scope and profound in implication, but a book ablaze with the furious passion of its own composition. At times, it reads like a race against death. At others, you can only wonder at the reach and raw intelligence of the writing. (...) The uncertainty and the loose flaps, the digressions and the rare unfoldings, the borrowing or pastiche of different genres, the blazing curtains of prose, the frequently hilarious non-sequiturs, together create an effect of startling anarchic grace, no less magnificent for being swallowed up in the novel's own encircling silence. (...) Much of the writing goes beyond any recognisable literary model and can only be approached on its own terms." - Richard Gwyn, The Independent "The next time you hear about the "death of the novel", beat the speaker over the head with 2666 . And then make them read it. Five books in one, masterfully interwoven not only by recurrent ideas and characters but by a torrential humour, deep humanity and sheer storytelling bravura, the posthumous masterpiece from the Chilean-turned-Catalan magician (splendidly translated by Natasha Wimmer) should stand on every self-respecting bookshelf." - Boyd Tonkin, The Independent " 2666 , a detective novel without a solution, contains much dark philosophical humour, wickedly effective pastiche and pages of gutsy, irreverent boisterousness (not to mention peculiar sex). (...) Among other things, 2666 offers an apology for the novel as a vast network that links all things, no matter how trivial or disparate. It is a marvellous gallimaufry of the funny, fabulist and, at times, oddly beautiful. All human life is contained in these burning pages, and Natasha Wimmer deserves a medal for her fluent translation." - Ian Thomson, Independent on Sunday "Whether he is as good as he wanted to be, or in the way he wanted to be, is another question, and the answer can�t be simple. It depends, I think, not only on the literary quality of the hugely ambitious late work, especially 2666 , but on how we read it and what we are looking for. (...) The way these stories arise and fade away doesn�t give us the sense that the narrative leads nowhere; just the sense that it doesn�t lead anywhere obvious, and that we are going to have to work out the connections that Bolaño has left for us to make." - Michael Wood, London Review of Books "This is no ordinary whodunit, but it is a murder mystery. Santa Teresa is not just a hell. It's a mirror also -- "the sad American mirror of wealth and poverty and constant, useless metamorphosis." (...) He wrote 2666 in a race against death. His ambitions were appropriately outsized: to make some final reckoning, to take life's measure, to wrestle to the limits of the void. So his reach extends beyond northern Mexico in the 1990s to Weimar Berlin and Stalin's Moscow, to Dracula's castle and the bottom of the sea." - Ben Ehrenreich, The Los Angeles Times " 2666 , like all of Bolaño's work, is a graveyard. (...) His ambitions for 2666 were greater: to write a postmortem for the dead of the past, the present and the future." - Marcela Valdes, The Nation "Die ganze Potenz seines Könnens legte er in diesen 1200-seitigen Roman (.....) (E)in Ineinander von Stimmungen und Überlegungen, Erregungen und Meditationen. (...) 2666 ist ein literarischer Amazonas, in dessen labyrinthische Verzweigungen und Stromschnellen hinaus ein jeder Leser mit einem Boot segelt, das sich als zu klein erweist. (...) Bolaño zieht das ganze Arsenal seines Könnens, um reale Gegenwart zu schaffen. Stupend sind sein Wissen und seine Beobachtungsgabe, die Potenz seiner (historischen) Imagination, die Sensitivität der Einfühlung, die Psychologie der Figurenzeichnung und nicht zuletzt die Organisation eines so gigantischen Stoffes und so vieler Erzählstränge." - Andreas Breitenstein, Neue Zürcher Zeitung "It is here that 2666 begins to betray its weaknesses. Each of its parts is brilliantly paced, and aside from the first few dozen pages of the third, consistently compelling. All are connected not only by the crimes, but also by a myriad of interwoven motifs. But the whole thing does not hold together. Bolaño goes too far this time in the centrifugal direction. The difficulty is not the novel's heterogeneity of form. Just as The Savage Detectives offers a crowd of voices, 2666 gives us a virtuosic range of narrative modes: academic satire in I, minimalism in III, reportage in IV, the bildungsroman or fictional biography in V, allegory and surrealism in places throughout. There is no problem with Bolaño's implication that to know something one must speak about it in different ways. The problem is that there is no single central something about which the novel attempts to speak." - William Deresiewicz, The New Republic "An outline of the narrative is, maybe, an evasion of what the book is about: it obscures the violence, the explicit and often overwrought sex (cocks a foot long, and no screw under three hours); it also obscures Bolaño's teasing, self-consciously literary tone. He is a relentlessly digressive author, and the book is packed with subplots, details and disquisitions to the point of neurosis. (...) When the dazzle has faded, what is the pattern that will be left imprinted on your vision ? Is it only the omnipresence of death ?" - Robert Hanks, New Statesman "The newest entry in Bolaño�s legendary oeuvre is the enormous, posthumous, ambiguously complete, inscrutably titled novel 2666 -- which arrives omni-buzzed and hyperdesigned, poised to be the most fashionable literary blockbuster of the holiday season. Having just spent the equivalent of a full workweek crawling through the book, however, I�m having trouble envisioning it as the hot Christmas item some people might expect. Its 893 pages are indisputably brilliant, but they are not, by any definition, brisk -- they�re tall, crowded, brutal, dense. In fact, one possible explanation of the mysterious title is that it would take any normal author 2,666 pages to convey what Bolaño manages to convey (or half-convey, or almost possibly begin to suggest he might convey) in just under 900." - Sam Anderson, New York "It�s hard to know what to make of 2666 . It reads like a puzzle crafted by a sadistic, sympathetic literary master. Given the way it rambles without urgency, it�s hard to believe it�s is the work of someone at death�s door. There are long stretches when I felt abandoned as a reader. (That he�s not here to explain himself makes for a perfect punch line.) Yet Bola�o reveals enough to keep us reading�a turn of phrase, a captured moment that just feels so confident, so singular. (...) If there�s something, anything, that ties these five books together, perhaps it�s a sense of the nakedness of life, the proximity of death and the occasional yearning to reach out and stroke the liquid air. It should be noted that although many lives are snuffed out in these pages, the writers seem to live on. 2666 may not be Bolaño�s masterpiece, but it�s also inescapable, unignorable and lasting." - Emily Borrow, The New York Observer "(O)ne doesn't really feel the lack of final revisions doing much to diminish its power. At many points, one feels about to be able to compare the book to something else. (...) Randomness and consequence competing for control over history, the struggle of the individual to survive with a functioning ethics: the themes carry over into the final section (.....) For a while yet, our brain feels rewired for multiplicity. This is not just a cultural or geographical question, though if 2666 contains a lesson it is that people are always from some confluence of factors more bizarre than a country. And it goes deeper than the question of multiple voices. We have eavesdropped on characters and then felt ourselves in the funny, sad, and dangerous process of needing and making meaning. Since there is no logical endpoint, we close with an image from the novel that is out of time. A world of "endless shipwreck," but met with the most radiant effort. It's as good a way as any to describe Bolaño and his overwhelming book. " - Sarah Kerr, The New York Review of Books "Almost 300 slow pages later, with "The Part About Archimboldi," this epic, maddening, mesmerizing adventure picks up energy as it nears its end. Archimboldi appears, not quite living up to his fanfare. The book tightens its focus, to the extent that a book with a huge population but no real principals can do so. And a description of Archimboldi�s prose offers a crystallization of Bolaño�s." - Janet Maslin, The New York Times " 2666 is as consummate a performance as any 900-page novel dare hope to be: Bolaño won the race to the finish line in writing what he plainly intended as a master statement. Indeed, he produced not only a supreme capstone to his own vaulting ambition, but a landmark in what's possible for the novel as a form in our increasingly, and terrifyingly, post-national world. The Savage Detectives looks positively hermetic beside it. (...) As in Arcimboldo's paintings, the individual elements of 2666 are easily catalogued, while the composite result, though unmistakable, remains ominously implicit, conveying a power unattainable by more direct strategies. (...) By writing across the grain of his doubts about what literature can do, how much it can discover or dare pronounce the names of our world's disasters, Bolaño has proven it can do anything, and for an instant, at least, given a name to the unnamable." - Jonathan Lethem, The New York Times Book Review " 2666 is not Roberto Bolaño�s masterpiece but almost a compendium, in individual scenes, of the qualities that made him a great writer. (...) By the end, after close to nine hundred pages, the reader will be impressed by the range and power on display but might wish that the novel cohered, rather than merely concluding." - The New Yorker "History, in this concept, is like a collective nightmare, and reading 2666 is much like enduring a horrific dream -- all you want to do is wake up but you can't -- because the multitalented Bolaño was a spellbinder: he knew how to make readers keep turning pages. (...) This is a daunting book, a book to admire more than like. But despite its faults -- the section on the serial murders is, frankly, tedious -- it beguiles a reader as few books do. If you're not one of those timid readers singled out at the beginning of this review, if you're a reader who'd rather see a novelist aim for the moon, even if he falls on his face, then this is the book for you." - Malcolm Jones, Newsweek " 2666 is a novel of stupefying ambition with a mock-documentary element at its core. (...) 2666 is indeed Bolaño's master statement, not just on account of its length and quality but also because it is the fullest expression of his two abiding themes: the writing life and violence. Bolaño's interest in the former is easy to explain -- he believed that a life dedicated to literature was the only one worth living." - William Skidelsky, The Observer "With The Savage Detectives having already been proclaimed Roberto Bolaño's "masterpiece", a new superlative is needed for this, the Chilean author's colossal final work." - Hermione Hoby, The Observer "The detailed and relentless cataloging of the deaths of hundreds of women in the border city of Santa Teresa in the novel's longest part, titled "The Part About the Crimes," serves as a lens through which readers witness the brutality of a modern society whose fabric has been torn by the exigencies of global capitalism, internal and external migration, and the dehumanization of the characters who people this nightmarish landscape." - Martha Kramer, Political Affairs "Like all superconfident bastards, 2666 is flattering, unpredictable, swaggering -- and irresistible to anyone who wants something to care about in the world of books. No wonder reviewers loved it. Reviewing a novel like this is about the most intense thrill a critic will ever have, short of writing one themselves. (...) The intoxicating force of 2666 also lies in its utter disregard for boundaries." - Tom Chatfield, Prospect "Bolaño is occasionally lyrical but more frequently direct, demonstrating a facility with styles and tones from broad comedy to blackest despair. The five discrete sections that make up 2666 could stand as novels in their own right, twists on different genres from academic satire to clinical police procedural to bildungsroman." - James Crossley, Review of Contemporary Fiction "(M)addening, inconclusive and very, very long; hideous in parts and beautiful in others; exerting a terrible power over the reader long after it's done. (...) As for the title, there are clues to its significance in other books, but trying to take apart Bolaño is like looking under the hood of a car to see what makes it go. The big cryptic number, like so much in the book, is a riddle without a right answer -- ineffable, yet palpitating with meaning." - Alexander Cuadros, San Francisco Chronicle " 2666 has still bigger goals in its sights, and though the mind shrinks from parts of it, it is impossible not to be overwhelmed by its ambition, and much of its achievement. (...) This is an unlikely bestseller, I must say: it is often very hard-going, deliberately frustrates the reader�s wish to discover, and challenges his ability to recall the details of plot and character at every point. (...) Does he have enough subject-matter to sustain his huge fictional design, or is he one of those writers who turn to exhibitions of the extreme to disguise a fundamental poverty of observed human experience ? The question goes unanswered, but I will say that the wild chaos of 2666 held me from beginning to end -- reminding me, above all, of The Man Without Qualities -- and sent me back to read all Bolaño�s other novels. You will want to experience this one." - Philip Hensher, The Spectator "The fact that the book remains as riveting as any top-notch thriller is testament to Bolano's astonishing virtuosity. (...) What is most memorable about 2666 is the sheer abundance of its narrative. Bolano mints characters with a spendthrift generosity, though there is nothing preening about this breadth of scope. (...) Bolano is equally unstinting with his subplots, which spring organically from the novel, like the colourful offshoots of a rampant tropical plant." - Stephen Amidon, Sunday Times "The first temptation might be to dismiss this wondrous novel as no more than cult fiction. (...) But 2666 is a major literary event. (...) (W)ith Bolaño nothing is simple. 2666 is also a deeply self-conscious work which concerns itself with the act of reading and writing (something almost every main character is seen doing at some stage). (...) It is both notably realistic (...) and elaborately inventive. It is an important development in the novel form and an unforgettable piece of writing that will resonate for years to come." - Stephen Abell, The Telegraph " 2666 is not a novel that any responsible critic could describe with words like brisk or taut . (Not like all those other brisk, taut 898-page novels.) That's not Bola�o's method. He's addicted to unsolved mysteries and seemingly extraneous details that actually do turn out to be extraneous, and he loves trotting out characters -- indelible thumbnail sketches -- whom we will never encounter a second time. (...) But the relentless gratuitousness of 2666 has its own logic and its own power, which builds into something overwhelming that hits you all the harder because you don't see it coming. This is a dangerous book, and you can get lost in it. How can art, Bolaño is asking, a medium of form and meaning, reflect a world that is blessed with neither ? That is in fact a cesspool of chance and filth ?" - Lev Grossman, Time "Wading through its 900 pages, one never feels that he could have pushed things further but chose to rein himself in; at every turn, he went for it. The result is a wild, ungoverned book, full of surreal inversions and wistful comedy, the source of countless pleasures. Yet it is also a menacing proposition for readers of average intolerance, exhaustingly playful and tauntingly long, founded on dream sequences and digressions, replete with red herrings and wild geese. The book's fever-ishness can be contagious; symptoms include nausea and déjà vu. (...) (I)ts whole approach seems to have been derived from Goethe's notion of "world literature". The difference is that Goethe conceived "world literature" as a way of thinking about all books, whereas Bolaño, with his mixture of dynamism and overreach, managed to achieve it in a single novel." - Leo Robson, The Times "(A)n exceptionally exciting literary labyrinth. (...) What strikes one first about it is the stylistic richness: rich, elegant yet slangy language that is immediately recognizable as Bolano's own mixture of Chilean, Mexican and European Spanish. Then there is 2666 's resistance to categorization. At times it is reminiscent of James Ellroy: gritty and scurrilous. At other moments it seems as though the Alexandria Quartet had been transposed to Mexico and populated by ragged versions of Durrell's characters. There's also a similarity with W. G. Sebald's work (.....) There are no defining moments in 2666 . Mysteries are never resolved. Anecdotes are all there is. Freak or banal events happen simultaneously, inform each other and poignantly keep the wheel turning. There is no logical end to a Bolano book." - Amaia Gabantxo, Times Literary Supplement "Even as the novel exudes the improvisatory nature of lived experience, Bolaño eases the reader towards the void represented by the murders in Santa Teresa. Quirky, vibrantly etched characters undergo crises that resonate with the darkness at the heart of the novel." - Michael Saler, Times Literary Supplement "In the staggeringly intricate, vast, and brilliantly unnerving 2666 , too, everyone is constantly moving toward the unknown, but this time, they're not alone." - Zach Baron, The Village Voice "Knowing that his liver ailment would probably kill him, Bolaño pulled out all the stops for his last novel and threw out the rulebook for conventional fiction. (...) Archimboldi never meets his critics, the reporters never solve the crimes, and nothing is resolved at the novel's end. (Even the title is left unexplained, though an editor's note offers a clue.) This is not because Bolaño didn't finish it but because he was more interested in conveying the culture of violence and how writers respond to it than in telling a tidy story. (...) The novel is probably longer than it needs to be, but there isn't a boring page in it, and I suspect further study would justify everything here." - Steven Moore, The Washington Post "Auf uns Leser wartet das Glück einer einzigartigen Entdecker-Reise, über Hunderte und Aberhunderte Seiten einer von Christian Hansen berückend aus dem Spanischen übersetzten Prosa, die tatsächlich ihresgleichen sucht. (Wenngleich Roberto Bolano wohl auch an dieser Formulierung die stilistische Prüderie gerügt hätte.)" - Marko Martin, Die Welt "Metaphernsicher, mit Sinn für rasante dramaturgische Schnitte (auch den locker eingestreuten Kürzestdialog beherrscht er hinreißend), dabei höchst ambivalent zwischen Frechheit, Wahn, Zynismus, Trauer, Wut und Komik schwankend, berichtet dieser chilenische Vielfraß und Alleskönner vom Bösen. Der deutsche Übersetzer Christian Hansen ist ebenfalls hoch zu loben. Er hat Bolaños rasch dahineilende Sätze in ein sehr gelenkiges Deutsch überführt und sich vor affigen Floskeln gehütet. Doch eine Crux gibt es. Sie betrifft den fünften und letzten Teil (.....) Deshalb mein Rat: Stellen Sie auf Seite 769 einfach das Lesen ein." - Sibylle Lewitscharoff, Die Welt Quotes : "The multiple story lines of 2666 are borne along by narrators who seem also to represent various of its literary influences, from European avant-garde to critical theory to pulp fiction, and who converge on the city of Santa Teresa as if propelled toward some final unifying epiphany. It seems appropriate that 2666 's abrupt end leaves us just short of whatever that epiphany might have been, resulting in another open-ended ending, in paths to retrace and resume, leaving everything behind again." - Francisco Goldman, The New York Review of Books (19/7/2007) Please note that these ratings solely represent the complete review 's biased interpretation and subjective opinion of the actual reviews and do not claim to accurately reflect or represent the views of the reviewers. Similarly the illustrative quotes chosen here are merely those the complete review subjectively believes represent the tenor and judgment of the review as a whole. We acknowledge (and remind and warn you) that they may, in fact, be entirely unrepresentative of the actual reviews by any other measure.

The complete review 's Review :

Now even bookish pharmacists are afraid to take on the great, imperfect, torrential works, books that blaze paths into the unknown. They choose the perfect exercises of the great masters. Or what amounts to the same thing: they want to watch the great masters spar, but they have no interest in real combat, when the great masters struggle against that something, that something that terrifies us all, that something that cows us and spurs us on, amid blood and mortal wounds and stench.

I don't know what I'm doing in Santa Teresa, Amalfitano said to himself after he'd been living in the city for a week. Don't you ? Don't you really ? he asked himself. Really I don't, he said to himself, and that was as elegant as he could be.

"A sketch of the industrial landscape in the third world," said Fate, "a piece of reportage about the current situation in Mexico, a panorama of the border, a serious crime story, for fuck's sake."

Even on the poorest streets people could be heard laughing. Some of the streets were completely dark, like black holes, and the laughter that came from who know where was the only sign, the only beacon that kept residents and strangers from getting lost.

And at last we come to Archimboldi's sister, Lotte Reiter.

The end of simulacra.

the paintings of the four seasons were pure bliss. Everything in everything, writes Ansky. As if Arcimboldo had learned a single lesson, but one of vital importance.

Every single thing in this country is an homage to everything in the world, even the things that haven't happened yet.

"No, not American either, more like African," said Junge, and he made more faces under the tree branches. "Or rather: Asian," murmured the critic.

About the Author :

Chilean author Roberto Bolaño lived 1953 to 2003.

© 2008-2021 the complete review Main | the New | the Best | the Rest | Review Index | Links

- Member Login

- Library Patron Login

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR

FREE NEWSLETTERS

Search: Title Author Article Search String:

2666 : Book summary and reviews of 2666 by Roberto Bolano

Summary | Reviews | More Information | More Books

by Roberto Bolano

Critics' Opinion:

Readers' rating:

Published Nov 2008 912 pages Genre: Literary Fiction Publication Information

Rate this book

About this book

Book summary.

Composed in the last years of Roberto Bolaño’s life, 2666 was greeted across Europe and Latin America as his highest achievement, surpassing even his previous work in its strangeness, beauty, and scope. Its throng of unforgettable characters includes academics and convicts, an American sportswriter, an elusive German novelist, and a teenage student and her widowed, mentally unstable father. Their lives intersect in the urban sprawl of Santa Teresa—a fictional Juárez—on the U.S-Mexico border, where hundreds of young factory workers, in the novel as in life, have disappeared.

- "Beyond the Book" articles

- Free books to read and review (US only)

- Find books by time period, setting & theme

- Read-alike suggestions by book and author

- Book club discussions

- and much more!

- Just $45 for 12 months or $15 for 3 months.

- More about membership!

Book Awards

Media reviews, reader reviews.

"Starred Review. It is safe to predict that no novel this year will have as powerful an effect on the reader as this one." - Publishers Weekly. "The book is rightly praised as Bolaño's masterpiece, but owing to its unorthodox length it will likely find greater favor among critics than among general readers." - Library Journal. "[A] consummate display of literary virtuosity powered by an emotional thrust that can rip your heart out ... Unquestionably the finest novel of the present century—and we may be saying the same thing 92 years from now." - Kirkus Reviews. "Bolaño’s masterwork . . . An often shockingly raunchy and violent tour de force (though the phrase seems hardly adequate to describe the novel’s narrative velocity, polyphonic range, inventiveness, and bravery)." - The New York Review of Books.

Click here and be the first to review this book!

Author Information

- Books by this Author

Roberto Bolano Author Biography

Roberto Bolaño was born in Chile on April 28, 1953. For much of his life he lived a nomadic existence, living in Chile, Mexico, El Salvador, France and Spain. During the 1970s, he formed an avant-garde group called infrarealism with other writers and poets in Mexico where he lived after leaving Chile when it fell under military dictatorship. He returned to Chile in 1972 but left again the next year when General Augusto Pinochet came to power. In the early eighties, he finally settled in the small town of Blanes, near Gerona in Northern Spain, where he died on July 15, 2003 of liver disease while awaiting a transplant. He is survived by his Spanish wife and his son and daughter. Bolaño received some of the Hispanic world's highest literary ...

... Full Biography

Name Pronunciation Roberto Bolano: roh-bAIR-toh bo-LAR-neo

Other books by Roberto Bolano at BookBrowse

More Recommendations

Readers also browsed . . ..

- Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld

- The Bullet Swallower by Elizabeth Gonzalez James

- Change by Edouard Louis

- Fruit of the Dead by Rachel Lyon

- Ways and Means by Daniel Lefferts

- The Oceans and the Stars by Mark Helprin

- A Great Country by Shilpi Somaya Gowda

- Prophet Song by Paul Lynch

- Leaving by Roxana Robinson

- Say Hello to My Little Friend by Jennine Capó Crucet

more literary fiction...

Support BookBrowse

Join our inner reading circle, go ad-free and get way more!

Find out more

BookBrowse Book Club

Members Recommend

The Mystery Writer by Sulari Gentill

There's nothing easier to dismiss than a conspiracy theory—until it turns out to be true.

The Divorcees by Rowan Beaird

A "delicious" debut novel set at a 1950s Reno divorce ranch about the complex friendships between women who dare to imagine a different future.

The Stone Home by Crystal Hana Kim

A moving family drama and coming-of-age story revealing a dark corner of South Korean history.

Who Said...

It is among the commonplaces of education that we often first cut off the living root and then try to replace its ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Solve this clue:

and be entered to win..

Your guide to exceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

Subscribe to receive some of our best reviews, "beyond the book" articles, book club info and giveaways by email.

- Biggest New Books

- Non-Fiction

- All Categories

- First Readers Club Daily Giveaway

- How It Works

Get the Book Marks Bulletin

Email address:

- Categories Fiction Fantasy Graphic Novels Historical Horror Literary Literature in Translation Mystery, Crime, & Thriller Poetry Romance Speculative Story Collections Non-Fiction Art Biography Criticism Culture Essays Film & TV Graphic Nonfiction Health History Investigative Journalism Memoir Music Nature Politics Religion Science Social Sciences Sports Technology Travel True Crime

April 3, 2024

- Remembering Maryse Condé

- On the development of New York City as a police state

- Leslie Jamison considers the pop-psychification of gaslighting

- Getting Started

- Start a Book Club

- Book Club Ideas/Help▼

- Our Featured Clubs ▼

- Popular Books

- Book Reviews

- Reading Guides

- Blog Home ▼

- Find a Recipe

- About LitCourse

- Course Catalog

2666 (Bolano)

Summary | Author | Book Reviews | Discussion Questions

2666 Roberto Bolano, trans., Natasha Wimmer, 2004 Macmillan Picador 912 pp. ISBN-13: 9780312429218

In Brief Winner, 2008 National Book Critics Circle Award Composed in the last years of Roberto Bolano’s life, 2666 was greeted across Europe and Latin America as his highest achievement, surpassing even his previous work in its strangeness, beauty, and scope. Its throng of unforgettable characters includes academics and convicts, an American sportswriter, an elusive German novelist, and a teenage student and her widowed, mentally unstable father. Their lives intersect in the urban sprawl of Santa Teresa—a fictional Juárez—on the U.S.-Mexico border, where hundreds of young factory workers, in the novel as in life, have disappeared ( From the publisher. )

More Roberto Bolano is a master of digression. Among the countless stories that he tells in 2666 , his 900-page cinderblock of a novel, there is not one that feels incomplete. (Considering that Bolano died in 2003 before he finished the final book of the five-part sequence, that’s quite a feat.) In his hands, narrative tangents, followed to their logical (or illogical, as the case may be) conclusions, fill in the spaces opened up by the boundlessly layered story lines.

To call 2666 ambitious is to understate its scale. Comprising five almost autonomous books, the novel is a chronicle of the 20th century, unafraid to confront its more gruesome turns in its sweep across history. The binding link, insofar as there is one, is the Mexican border town of Santa Teresa, modeled on Ciudad Juárez, where for the better part of the 1990s there were hundreds of brutal murders, with the bodies of young women turning up in dumps and deserts at the city’s margin. The fourth, and longest, of the books takes up the matter of the murders directly, taking readers sequentially through each of the killings, along with the sexual abuse, mutilation, and police incompetence that accompanied them. They vary in their specifics, but the broad template is the same. Bolano writes with the blank neutrality of a police report:

In September, the body of Ana Muñoz Sanjuán was found behind some trash cans on Calle Javier Paredes, between Colonia Félix Gómez and Colonia Centro. The body was completely naked and showed evidence of strangulation and rape, which would later be confirmed by the medical examiner .

(From Barnes & Noble Review .) top of page

About the Author • Birth—April 28, 1953 • Where—Santiago, Chile • Reared—in Chile and Mexico City, Mexico • Died—July 15, 2003 • Where—Blanes, Spain • Awards—Herralde Prize, Romulo Gallegos Prize (both for Savage Detectives , 1998)

Bolano was born in Chile and raised in Mexico. He later emigrated to Spain, where he died aged 50. His early years were spent in southern and coastal Chile; by his own account he was a skinny, nearsighted and bookish but unpromising child. He suffered from dyslexia as a child, and was often bullied at school, where he felt an outsider. As a teenager, though, he moved with his family to Mexico, dropped out of school, worked as a journalist and became active in left-wing political causes.

He returned to Chile just before the 1973 coup that installed Gen. Augusto Pinochet in power, and, like many others of his age and background, was jailed.

For most of his youth, Bolano was a vagabond, living at one time or another in Chile, Mexico, El Salvador, France and Spain, where he finally settled down in the early 1980s in the small Catalan beach town of Blanes.

Bolano was a heroin addict in his youth and died of chronic hepatitis, caused by Hepatitis C, with which he was infected as a result of sharing needles during his "mainlining" days. He had suffered from liver failure and was on a transplant list.

He was survived by his Spanish wife and their two children, whom he once called "my only motherland." (In his last interview, published by the Mexican edition of Playboy magazine, Bolano said he regarded himself as a Latin American, adding that "my only country is my two children and perhaps, though in second place, some moments, streets, faces or books that are in me.") Bolano named his only son Lautaro, after the Mapuche leader Lautaro, who resisted the Spanish conquest of Chile, as related in the sixteenth-century epic La araucana .

A key episode in Bolano's life, mentioned in different forms in several of his works, occurred in 1973, when he left Mexico for Chile to "help build the revolution." After Augusto Pinochet's coup against Salvador Allende, Bolano was arrested on suspicion of being a terrorist and spent eight days in custody. He was rescued by two former classmates who had become prison guards. Bolano describes his experience in the story "Dance Card." According to the version of events he provides in this story, he was neither tortured nor killed, as he had expected, but...

In the small hours I could hear them torturing others; I couldn't sleep and there was nothing to read except a magazine in English that someone had left behind. The only interesting article in it was about a house that had once belonged to Dylan Thomas.... I got out of that hole thanks to a pair of detectives who had been at high school with me in Los Angeles .

In the 1970s, Bolano became a Trotskyist and a founding member of infrarrealismo, a minor poetic movement. Although deep down he always felt like a poet, in the vein of his beloved Nicanor Parra, his reputation ultimately rests on his novels, novellas and short story collections.

After an interlude in El Salvador, spent in the company of the poet Roque Dalton and the guerrillas of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, Bolano returned to Mexico, living as a bohemian poet and literary enfant terrible—a professional provocateur feared at all the publishing houses even though he was a nobody, bursting into literary presentations and readings, his editor, Jorge Herralde, recalled. His erratic behaviour had as much to do with his leftist ideology as with his chaotic, heroin-addicted lifestyle.

Bolano finally made his way to Spain, where he married and settled on the Mediterranean coast near Barcelona, working as a dishwasher, a campground custodian, bellhop and garbage collector—working during the day and writing at night.

In an interview Bolano stated that his decision to shift to fiction at the age of 40 was because he felt responsible for the future financial well-being of his family, which he knew he could never secure from the earnings of a poet. He continued to think of himself primarily as a poet, and a 20-year collection of his verse was published in 2000 under the title The Romantic Dogs .

As regards his native country, which he visited just once after going into exile, Bolano had conflicted feelings. He was notorious in Chile for his fierce attacks on Isabel Allende and other members of the literary establishment. "He didn't fit into Chile, and the rejection that he experienced left him free to say whatever he wanted, which can be a good thing for a writer," said the Chilean novelist and playwright Ariel Dorfman.

Six weeks before he died, Bolano's fellow Latin American novelists hailed him as the most important figure of his generation at an international conference he attended in Seville. He counted among his closest friends novelists Rodrigo Fresan and Enrique Vila-Matas. According to Fresan:

Roberto emerged as a writer at a time when Latin America no longer believed in utopias, when paradise had become hell, and that sense of monstrousness and waking nightmares and constant flight from something horrid permeates 2666 and all his work. His books are political, but in a way that is more personal than militant or demagogic, that is closer to the mystique of the beatniks than the Boom .

Bolano was extraordinarily prolific, but Jorge Herralde reports that not much remains unpublished: a volume of poetry tentatively called The Unknown University and one more collection of short stories.

Bolano joked about the "posthumous", saying the word "sounds like the name of a Roman gladiator, one who is undefeated", and he would no doubt be amused to see how his stock has risen now that he is dead.

Rodrigo Fresan has observed that "Roberto was one of a kind, a writer who worked without a net, who went all out, with no brakes, and in doing so, created a new way to be a great Latin American writer."

Although Bolano espoused the lifestyle of a bohemian poet and enfant terrible writer all his life, he only began publishing fiction regularly in the late 1990s, after he quit his addiction to heroin. He immediately became a widely respected figure in Spanish and Latin American letters. In rapid succession, he published a widely acclaimed series of works, the most important of which are the novel Los detectives salvajes ( The Savage Detectives ), the novella Nocturno de Chile ( By Night in Chile ), and, posthumously, the novel 2666. His two collections of short stories Llamadas telefónicas and Putas asesinas were awarded literary prizes. ( From Wikipedia .) top of page

Critics Say . . . Make no mistake, 2666 is a work of huge importance ... a complex literary experience, in which the author seeks to set down his nightmares while he feels time running out. Bolano inspires passion, even when his material, his era, and his volume seem overwhelming. This could only be published in a single volume, and it can only be read as one. El Mundo

Think of David Lynch, Marcel Duchamp (both explicitly invoked here) and the Bob Dylan of "Highway 61 Revisited," all at the peak of their lucid yet hallucinatory powers. Bolano's references were sufficiently global to encompass all that, and to interweave both stuffy academia and tawdry gumshoe fiction into this book's monumentally inclusive mix. Janet Maslin - New York Times

2666 is as consummate a performance as any 900-page novel dare hope to be: Bolano won the race to the finish line in writing what he plainly intended, in his self-interrogating way, as a master statement. Indeed, he produced not only a supreme capstone to his own vaulting ambition, but a landmark in what's possible for the novel as a form in our increasingly, and terrifyingly, post-national world.... By writing across the grain of his doubts about what literature can do, how much it can discover or dare pronounce the names of our world's disasters, Bolano has proven it can do anything, and for an instant, at least, given a name to the unnamable. Jonathan Lethem - New York Times Book Review

Last year's The Savage Detectives by the late Chilean-Mexican novelist Bolano (1953-2003) garnered extraordinary sales and critical plaudits for a complex novel in translation, and quickly became the object of a literary cult. This brilliant behemoth is grander in scope, ambition and sheer page count, and translator Wimmer has again done a masterful job. The novel is divided into five parts (Bolano originally imagined it being published as five books) and begins with the adventures and love affairs of a small group of scholars dedicated to the work of Benno von Archimboldi, a reclusive German novelist. They trace the writer to the Mexican border town of Santa Teresa (read: Juarez), but there the trail runs dry, and it isn't until the final section that readers learn about Benno and why he went to Santa Teresa. The heart of the novel comes in the three middle parts: in "The Part About Amalfitano," a professor from Spain moves to Santa Teresa with his beautiful daughter, Rosa, and begins to hear voices. "The Part About Fate," the novel's weakest section, concerns Quincy "Fate" Williams, a black American reporter who is sent to Santa Teresa to cover a prizefight and ends up rescuing Rosa from her gun-toting ex-boyfriend. "The Part About the Crimes," the longest and most haunting section, operates on a number of levels: it is a tormented catalogue of women murdered and raped in Santa Teresa; a panorama of the power system that is either covering up for the real criminals with its implausible story that the crimes were all connected to a German national, or too incompetent to find them (or maybe both); and it is a collection of the stories of journalists, cops, murderers, vengeful husbands, prisoners and tourists, among others, presided over by an old woman seer. It is safe to predict that no novel this year will have as powerful an effect on the reader as this one. Publishers Weekly

This sprawling, digressive, Jamesian "loose, baggy monster" reads like five independent but interrelated novels, connected by a common link to an actual series of mostly unresolved murders of female factory workers in the area of Ciudad Juárez (here called Santa Teresa), a topic also addressed in Margorie Agosín's Secrets in the Sand. The first part follows four literary critics who wind up in Mexico in pursuit of the obscure (and imaginary) German writer Benno von Archimboldi, a scenario that recalls Bolano's The Savage Detectives . The second and third parts, respectively, focus on Professor Almafitano and African American reporter Quincy Williams (also called Oscar Fate), whose attempts to expose the murders are thwarted. The fourth, and by far the longest, section consists mostly of detached accounts of the hundreds of murders; culled from newspaper and police reports, they offer a relentless onslaught of the gruesome details and become increasingly tedious. The last section returns to Archimboldi. Boasting Bolano's trademark devices—ambiguity, open endings, characters that assume different names, and an enigmatic title, along with splashes of humor—this posthumously published work is consistently masterful until the last half of the final part, which shows some haste. The book is rightly praised as Bolano's masterpiece, but owing to its unorthodox length it will likely find greater favor among critics than among general readers. In fact, before he died, the author asked that it be published in five parts over just as many years; it's a pity his relatives refused to honor his request. Lawrence Olszewski - Library Journal

Life and art, death and transfiguration reverberate with protean intensity in the late (1953–2003) Chilean author's final work: a mystery and quest novel of unparalleled richness. Published posthumously in a single volume, despite its author's instruction that it appear as five distinct novels, it's a symphonic envisioning of moral and societal collapse, which begins with a mordantly amusing account ("The Part About the Critics") of the efforts of four literary scholars to discover the obscured personal history and unknown present whereabouts of German novelist Benno von Archimboldi, an itinerant recluse rumored to be a likely Nobel laureate. Their searches lead them to northern Mexico, in a desert area notorious for the unsolved murders of hundreds of Mexican women presumably seeking freedom by crossing the U.S. border. In the novel's second book, a Spanish academic (Amalfitano) now living in Mexico fears a similar fate threatens his beautiful daughter Rosa. It's followed by the story of a black American journalist whom Rosa encounters, in a subplot only imperfectly related to the main narrative. Then, in "The Part About the Crimes," the stories of the murdered women and various people in their lives (which echo much of the content of Bolano's other late mega-novel The Savage Detectives ) lead to a police investigation that gradually focuses on the fugitive Archimboldi. Finally, "The Part About Archimboldi" introduces the figure of Hans Reiter, an artistically inclined young German growing up in Hitler's shadow, living what amounts to an allegorical representation of German culture in extremis, and experiencing transformations that will send him halfway around the world; bring him literary success, consuming love and intolerable loss; and culminate in a destiny best understood by Reiter's weary, similarly bereaved and burdened sister Lotte: "He's stopped existing." Bolano's gripping, increasingly astonishing fiction echoes the world-encompassing masterpieces of Stendhal, Mann, Grass, Pynchon and Garcia Marquez, in a consummate display of literary virtuosity powered by an emotional thrust that can rip your heart out. Unquestionably the finest novel of the present century—and we may be saying the same thing 92 years from now. Kirkus Reviews top of page

Book Club Discussion Questions Use our LitLovers Book Club Resources; they can help with discussions for any book:

• How to Discuss a Book (helpful discussion tips) • Generic Discussion Questions—Fiction and Nonfiction • Read-Think-Talk (a guided reading chart) top of page

LitLovers © 2024

- Literature & Fiction

Buy new: ₹1,953.00

Other Sellers on Amazon

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet or computer – no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera, scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

2666: A Novel Paperback – 1 September 2009

Save extra with 2 offers, 10 days replacement, replacement instructions.

Purchase options and add-ons

- Print length 912 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Picador

- Publication date 1 September 2009

- Dimensions 13.84 x 3.94 x 20.83 cm

- ISBN-10 0312429215

- ISBN-13 978-0312429218

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Product description

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : Picador; Reprint edition (1 September 2009)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 912 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0312429215

- ISBN-13 : 978-0312429218

- Item Weight : 686 g

- Dimensions : 13.84 x 3.94 x 20.83 cm

- #354,986 in Literature & Fiction (Books)

About the author

Roberto bolaño.

Author of 2666 and many other acclaimed works, Roberto Bolaño (1953-2003) was born in Santiago, Chile, and later lived in Mexico, Paris, and Spain. He has been acclaimed "by far the most exciting writer to come from south of the Rio Grande in a long time" (Ilan Stavans, The Los Angeles Times)," and as "the real thing and the rarest" (Susan Sontag). Among his many prizes are the extremely prestigious Herralde de Novela Award and the Premio Rómulo Gallegos. He was widely considered to be the greatest Latin American writer of his generation. He wrote nine novels, two story collections, and five books of poetry, before dying in July 2003 at the age of 50. Chris Andrews has won the TLS Valle Inclán Prize and the PEN Translation Prize for his Bolaño translations.

Photo by Farisori (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Customer reviews

Reviews with images.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from India

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Press Releases

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell under Amazon Accelerator

- Protect and Build Your Brand

- Amazon Global Selling

- Become an Affiliate

- Fulfilment by Amazon

- Advertise Your Products

- Amazon Pay on Merchants

- COVID-19 and Amazon

- Your Account

- Returns Centre

- 100% Purchase Protection

- Amazon App Download

- Netherlands

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Conditions of Use & Sale

- Privacy Notice

- Interest-Based Ads

Advertisement

Supported by

editors’ choice

8 New Books We Recommend This Week

Suggested reading from critics and editors at The New York Times.

- Share full article

Our fiction recommendations this week include a “gleeful romp” of a series mystery, along with three novels by some heavy-hitting young writers: Téa Obreht, Helen Oyeyemi and Tommy Orange. (How heavy-hitting, and how young? Consider that Obreht was included in The New Yorker’s “20 Under 40” issue in 2010 — and she’s still under 40 today. So is Oyeyemi, who was one of Granta’s “Best Young British Novelists” in 2013, while Orange, at 42, has won the PEN/Hemingway Award, the John Leonard Prize and the American Book Award. The future is in good hands.)

In nonfiction, we recommend a painter’s memoir, a group biography of three jazz giants, a posthumous essay collection by the great critic Joan Acocella and a journalist’s look at American citizens trying to come to terms with a divided country. Happy reading. — Gregory Cowles

THE MORNINGSIDE Téa Obreht

After being displaced from their homeland, Silvia and her mother move into the Morningside, a weather-beaten luxury apartment building in “Island City,” a sinking version of New York in the middle of all-out climate collapse. Silvia learns about her heritage through the folk tales her aunt Ena tells her, and becomes fascinated with the mysterious woman who lives in the penthouse apartment.

“I marveled at the subtle beauty and precision of Obreht’s prose. … Even in the face of catastrophe, there’s solace to be found in art.”

From Jessamine Chan’s review

Random House | $29

A GRAVE ROBBERY Deanna Raybourn

In their ninth crime-solving tale, the Victorian-era adventuress and butterfly hunter Veronica Speedwell and her partner discover that a wax mannequin is actually a dead young woman, expertly preserved.

“Throw in an assortment of delightful side characters and an engaging tamarin monkey, and what you have is the very definition of a gleeful romp.”

From Sarah Weinman’s crime column

Berkley | $28

THE BLOODIED NIGHTGOWN: And Other Essays Joan Acocella

Acocella, who died in January, may have been best known as one of our finest dance critics. But as this posthumous collection shows, she brought the same rigor, passion and insight to all the art she consumed. Whether her subject is genre fiction, “Beowulf” or Marilynne Robinson, Acocella’s knowledge and enthusiasm are hard to match. We will not see her like again.

"Some critics are haters, but Acocella began writing criticism because she loved — first dance, and then much of the best of Western culture. She let life bring her closer to art."

From Joanna Biggs’s review

Farrar, Straus & Giroux | $35

WANDERING STARS Tommy Orange

This follow-up to Orange’s debut, “There There,” is part prequel and part sequel; it trails the young survivor of a 19th-century massacre of Native Americans, chronicling not just his harsh fate but those of his descendants. In its second half, the novel enters 21st-century Oakland, following the family in the aftermath of a shooting.

“Orange’s ability to highlight the contradictory forces that coexist within friendships, familial relationships and the characters themselves ... makes ‘Wandering Stars’ a towering achievement.”

From Jonathan Escoffery’s review

Knopf | $29

PARASOL AGAINST THE AXE Helen Oyeyemi

In Oyeyemi’s latest magical realist adventure, our hero is a woman named Hero, and she is hurtling through the city of Prague, with a shape-shifting book about Prague, during a bachelorette weekend. But Hero doesn’t seem to be directing the novel’s action; the story itself seems to be calling the shots.

“Her stock-in-trade has always been tales at their least domesticated. … In this novel, they have all the autonomy, charisma and messiness of living beings — and demand the same respect.”

From Chelsea Leu’s review

Riverhead | $28

3 SHADES OF BLUE: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, and the Lost Empire of Cool James Kaplan

On one memorable occasion in 1959, three outstanding musicians came together for what may be the greatest jazz record ever, Davis’s “Kind of Blue.” Kaplan, the author of a Frank Sinatra biography, traces the lives of his protagonists in compelling fashion; he may not be a jazz expert but he knows how to tell a good story.

“Kaplan has framed '3 Shades of Blue' as both a chronicle of a golden age and a lament for its decline and fall. One doesn’t have to accept the decline-and-fall part to acknowledge that he has done a lovely job of evoking the golden age.”

From Peter Keepnews’s review

Penguin Press | $35

WITH DARKNESS CAME STARS: A Memoir Audrey Flack

From her early days as an Abstract Expressionist who hung out with Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning at the Cedar Bar to her later success as a pioneering photorealist, Flack worked and lived at the center of New York’s art world over her long career; here she chronicles the triumphs, the slights, the sexism and the gossip, all with equal relish.

“Flack is a natural, unfiltered storyteller. … The person who emerges from her pages is someone who never doubts she has somewhere to go.”

From Prudence Peiffer’s review

Penn State University Press | $37.50

AN AMERICAN DREAMER: Life in a Divided Country David Finkel

Agile and bracing, Finkel’s book trails a small network of people struggling in the tumultuous period between the 2016 and 2020 U.S. presidential elections. At the center is Brent Cummings, a white Iraq war veteran who is trying to cope with a country he no longer recognizes.

“Adroitly assembles these stories into a poignant account of the social and political mood in the United States. … A timely and compelling argument for tolerance and moral character in times of extreme antagonism.”

From John Knight’s review

Random House | $32

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

James McBride’s novel sold a million copies, and he isn’t sure how he feels about that, as he considers the critical and commercial success of “The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store.”

How did gender become a scary word? Judith Butler, the theorist who got us talking about the subject , has answers.