Persuasive Writing In Three Steps: Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis

April 14, 2021 by Ryan Law in

Great writing persuades. It persuades the reader that your product is right for them, that your process achieves the outcome they desire, that your opinion supersedes all other opinions. But spend an hour clicking around the internet and you’ll quickly realise that most content is passive, presenting facts and ideas without context or structure. The reader must connect the dots and create a convincing argument from the raw material presented to them. They rarely do, and for good reason: It’s hard work. The onus of persuasion falls on the writer, not the reader. Persuasive communication is a timeless challenge with an ancient solution. Zeno of Elea cracked it in the 5th century B.C. Georg Hegel gave it a lick of paint in the 1800s. You can apply it to your writing in three simple steps: thesis, antithesis, synthesis.

Use Dialectic to Find Logical Bedrock

“ Dialectic ” is a complicated-sounding idea with a simple meaning: It’s a structured process for taking two seemingly contradictory viewpoints and, through reasoned discussion, reaching a satisfactory conclusion. Over centuries of use the term has been burdened with the baggage of philosophy and academia. But at its heart, dialectics reflects a process similar to every spirited conversation or debate humans have ever had:

- Person A presents an idea: “We should travel to the Eastern waterhole because it’s closest to camp.”

- Person B disagrees and shares a counterargument: “I saw wolf prints on the Eastern trail, so we should go to the Western waterhole instead.”

- Person A responds to the counterargument , either disproving it or modifying their own stance to accommodate the criticism: “I saw those same wolf prints, but our party is large enough that the wolves won’t risk an attack.”

- Person B responds in a similar vein: “Ordinarily that would be true, but half of our party had dysentery last week so we’re not at full strength.”

- Person A responds: “They got dysentery from drinking at the Western waterhole.”

This process continues until conversational bedrock is reached: an idea that both parties understand and agree to, helped by the fact they’ve both been a part of the process that shaped it.

Dialectic is intended to help draw closer to the “truth” of an argument, tempering any viewpoint by working through and resolving its flaws. This same process can also be used to persuade.

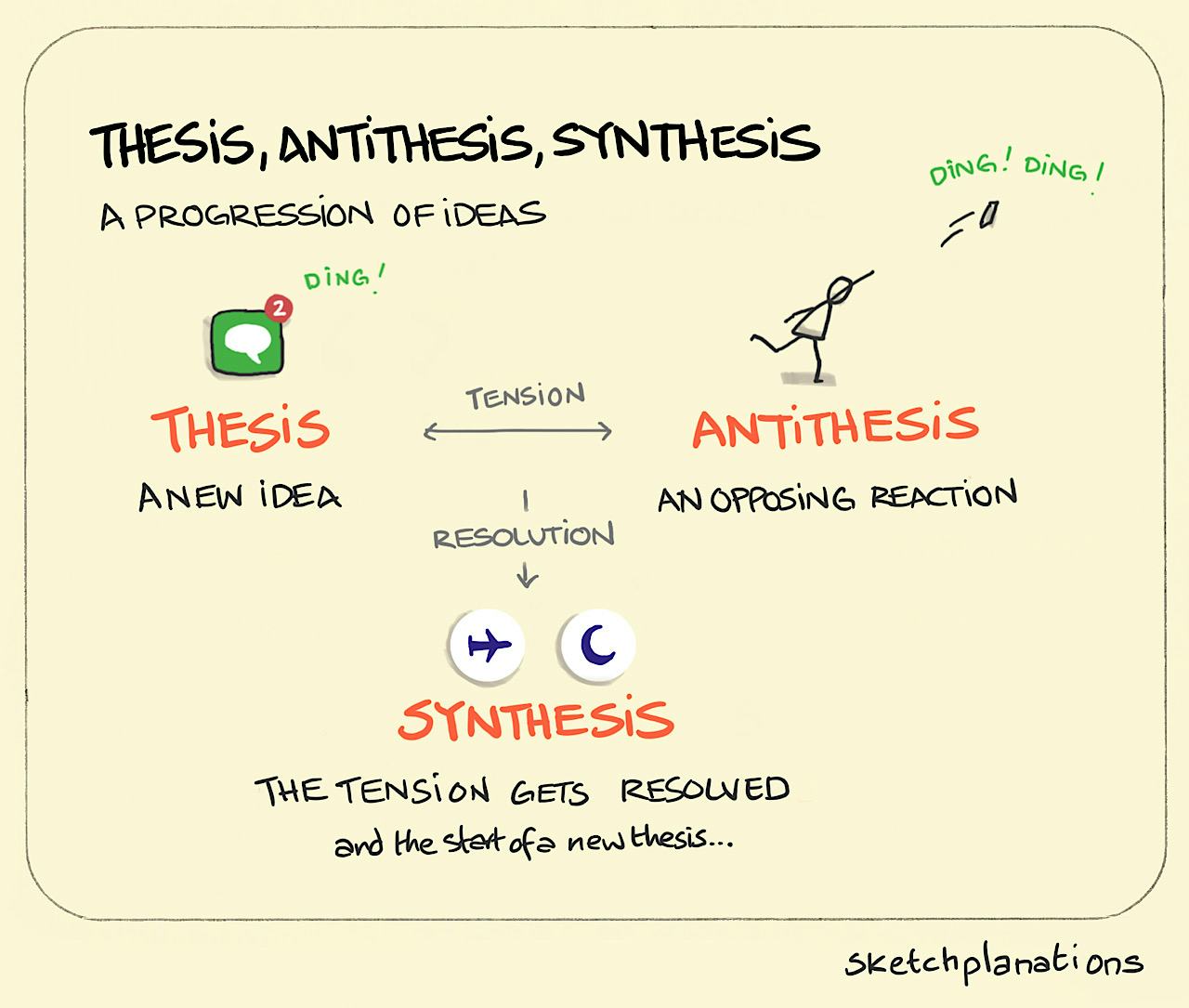

Create Inevitability with Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis

The philosopher Georg Hegel is most famous for popularizing a type of dialectics that is particularly well-suited to writing: thesis, antithesis, synthesis (also known, unsurprisingly, as Hegelian Dialectic ).

- Thesis: Present the status quo, the viewpoint that is currently accepted and widely held.

- Antithesis: Articulate the problems with the thesis. (Hegel also called this phase “the negative.”)

- Synthesis: Share a new viewpoint (a modified thesis) that resolves the problems.

Hegel’s method focused less on the search for absolute truth and more on replacing old ideas with newer, more sophisticated versions . That, in a nutshell, is the same objective as much of content marketing (and particularly thought leadership content ): We’re persuading the reader that our product, processes, and ideas are better and more useful than the “old” way of doing things. Thesis, antithesis, synthesis (or TAS) is a persuasive writing structure because it:

- Reduces complex arguments into a simple three-act structure. Complicated, nuanced arguments are simplified into a clear, concise format that anyone can follow. This simplification reflects well on the author: It takes mastery of a topic to explain it in it the simplest terms.

- Presents a balanced argument by “steelmanning” the best objection. Strong, one-sided arguments can trigger reactance in the reader: They don’t want to feel duped. TAS gives voice to their doubts, addressing their best objection and “giv[ing] readers the chance to entertain the other side, making them feel as though they have come to an objective conclusion.”

- Creates a sense of inevitability. Like a story building to a satisfying conclusion, articles written with TAS take the reader on a structured, logical journey that culminates in precisely the viewpoint we wish to advocate for. Doubts are voiced, ideas challenged, and the conclusion reached feels more valid and concrete as a result.

There are two main ways to apply TAS to your writing: Use it beef up your introductions, or apply it to your article’s entire structure.

Writing Article Introductions with TAS

Take a moment to scroll back to the top of this article. If I’ve done my job correctly, you’ll notice a now familiar formula staring back at you: The first three paragraphs are built around Hegel’s thesis, antithesis, synthesis structure. Here’s what the introduction looked like during the outlining process . The first paragraph shares the thesis, the accepted idea that great writing should be persuasive:

Next up, the antithesis introduces a complicating idea, explaining why most content marketing isn’t all that persuasive:

Finally, the synthesis shares a new idea that serves to reconcile the two previous paragraphs: Content can be made persuasive by using the thesis, antithesis, synthesis framework. The meat of the article is then focused on the nitty-gritty of the synthesis.

Introductions are hard, but thesis, antithesis, synthesis offers a simple way to write consistently persuasive opening copy. In the space of three short paragraphs, the article’s key ideas are shared , the entire argument is summarised, and—hopefully—the reader is hooked.

Best of all, most articles—whether how-to’s, thought leadership content, or even list content—can benefit from Hegelian Dialectic , for the simple reason that every article introduction should be persuasive enough to encourage the reader to stick around.

Structuring Entire Articles with TAS

Harder, but most persuasive, is to use thesis, antithesis, synthesis to structure your entire article. This works best for thought leadership content. Here, your primary objective is to advocate for a new idea and disprove the old, tired way of thinking—exactly the use case Hegel intended for his dialectic. It’s less useful for content that explores and illustrates a process, because the primary objective is to show the reader how to do something (like this article—otherwise, I would have written the whole darn thing using the framework). Arjun Sethi’s article The Hive is the New Network is a great example.

The article’s primary purpose is to explain why the “old” model of social networks is outmoded and offer a newer, better framework. (It would be equally valid—but less punchy—to publish this with the title “ Why the Hive is the New Network.”) The thesis, antithesis, synthesis structure shapes the entire article:

- Thesis: Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram grew by creating networks “that brought existing real-world relationships online.”

- Antithesis: As these networks grow, the less useful they become, skewing towards bots, “celebrity, meme and business accounts.”

- Synthesis: To survive continued growth, these networks need to embrace a new structure and become hives.

With the argument established, the vast majority of the article is focused on synthesis. After all, it requires little elaboration to share the status quo in a particular situation, and it’s relatively easy to point out the problems with a given idea. The synthesis—the solution that needs to reconcile both thesis and antithesis—is the hardest part to tackle and requires the greatest word count. Throughout the article, Arjun is systematically addressing the “best objections” to his theory and demonstrating why the “Hive” is the best solution:

- Antithesis: Why now? Why didn’t Hives emerge in the first place?

- Thesis: We were limited by technology, but today, we have the necessary infrastructure: “We’re no longer limited to a broadcast radio model, where one signal is received by many nodes. ...We sync with each other instantaneously, and all the time.”

- Antithesis: If the Hive is so smart, why aren’t our brightest and best companies already embracing it?

- Thesis: They are, and autonomous cars are a perfect example: “Why are all these vastly different companies converging on the autonomous car? That’s because for these companies, it’s about platform and hive, not just about roads without drivers.”

It takes bravery to tackle objections head-on and an innate understanding of the subject matter to even identify objections in the first place, but the effort is worthwhile. The end result is a structured journey through the arguments for and against the “Hive,” with the reader eventually reaching the same conclusion as the author: that “Hives” are superior to traditional networks.

Destination: Persuasion

Persuasion isn’t about cajoling or coercing the reader. Statistics and anecdotes alone aren’t all that persuasive. Simply sharing a new idea and hoping that it will trigger an about-turn in the reader’s beliefs is wishful thinking. Instead, you should take the reader on a journey—the same journey you travelled to arrive at your newfound beliefs, whether it’s about the superiority of your product or the zeitgeist-changing trend that’s about to break. Hegelian Dialectic—thesis, antithesis, synthesis— is a structured process for doing precisely that. It contextualises your ideas and explains why they matter. It challenges the idea and strengthens it in the process. Using centuries-old processes, it nudges the 21st-century reader onto a well-worn path that takes them exactly where they need to go.

Ryan is the Content Director at Ahrefs and former CMO of Animalz.

Why ‘Vertical Volatility’ Is the Missing Link in Your Keyword Strategy

Get insight and analysis on the world's top SaaS brands, each and every Monday morning.

Success! Now check your email to confirm your subscription.

There was an error submitting your subscription. Please try again.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Hegel’s Dialectics

“Dialectics” is a term used to describe a method of philosophical argument that involves some sort of contradictory process between opposing sides. In what is perhaps the most classic version of “dialectics”, the ancient Greek philosopher, Plato (see entry on Plato ), for instance, presented his philosophical argument as a back-and-forth dialogue or debate, generally between the character of Socrates, on one side, and some person or group of people to whom Socrates was talking (his interlocutors), on the other. In the course of the dialogues, Socrates’ interlocutors propose definitions of philosophical concepts or express views that Socrates challenges or opposes. The back-and-forth debate between opposing sides produces a kind of linear progression or evolution in philosophical views or positions: as the dialogues go along, Socrates’ interlocutors change or refine their views in response to Socrates’ challenges and come to adopt more sophisticated views. The back-and-forth dialectic between Socrates and his interlocutors thus becomes Plato’s way of arguing against the earlier, less sophisticated views or positions and for the more sophisticated ones later.

“Hegel’s dialectics” refers to the particular dialectical method of argument employed by the 19th Century German philosopher, G.W.F. Hegel (see entry on Hegel ), which, like other “dialectical” methods, relies on a contradictory process between opposing sides. Whereas Plato’s “opposing sides” were people (Socrates and his interlocutors), however, what the “opposing sides” are in Hegel’s work depends on the subject matter he discusses. In his work on logic, for instance, the “opposing sides” are different definitions of logical concepts that are opposed to one another. In the Phenomenology of Spirit , which presents Hegel’s epistemology or philosophy of knowledge, the “opposing sides” are different definitions of consciousness and of the object that consciousness is aware of or claims to know. As in Plato’s dialogues, a contradictory process between “opposing sides” in Hegel’s dialectics leads to a linear evolution or development from less sophisticated definitions or views to more sophisticated ones later. The dialectical process thus constitutes Hegel’s method for arguing against the earlier, less sophisticated definitions or views and for the more sophisticated ones later. Hegel regarded this dialectical method or “speculative mode of cognition” (PR §10) as the hallmark of his philosophy and used the same method in the Phenomenology of Spirit [PhG], as well as in all of the mature works he published later—the entire Encyclopaedia of Philosophical Sciences (including, as its first part, the “Lesser Logic” or the Encyclopaedia Logic [EL]), the Science of Logic [SL], and the Philosophy of Right [PR].

Note that, although Hegel acknowledged that his dialectical method was part of a philosophical tradition stretching back to Plato, he criticized Plato’s version of dialectics. He argued that Plato’s dialectics deals only with limited philosophical claims and is unable to get beyond skepticism or nothingness (SL-M 55–6; SL-dG 34–5; PR, Remark to §31). According to the logic of a traditional reductio ad absurdum argument, if the premises of an argument lead to a contradiction, we must conclude that the premises are false—which leaves us with no premises or with nothing. We must then wait around for new premises to spring up arbitrarily from somewhere else, and then see whether those new premises put us back into nothingness or emptiness once again, if they, too, lead to a contradiction. Because Hegel believed that reason necessarily generates contradictions, as we will see, he thought new premises will indeed produce further contradictions. As he puts the argument, then,

the scepticism that ends up with the bare abstraction of nothingness or emptiness cannot get any further from there, but must wait to see whether something new comes along and what it is, in order to throw it too into the same empty abyss. (PhG-M §79)

Hegel argues that, because Plato’s dialectics cannot get beyond arbitrariness and skepticism, it generates only approximate truths, and falls short of being a genuine science (SL-M 55–6; SL-dG 34–5; PR, Remark to §31; cf. EL Remark to §81). The following sections examine Hegel’s dialectics as well as these issues in more detail.

1. Hegel’s description of his dialectical method

2. applying hegel’s dialectical method to his arguments, 3. why does hegel use dialectics, 4. is hegel’s dialectical method logical, 5. syntactic patterns and special terminology in hegel’s dialectics, english translations of key texts by hegel, english translations of other primary sources, secondary literature, other internet resources, related entries.

Hegel provides the most extensive, general account of his dialectical method in Part I of his Encyclopaedia of Philosophical Sciences , which is often called the Encyclopaedia Logic [EL]. The form or presentation of logic, he says, has three sides or moments (EL §79). These sides are not parts of logic, but, rather, moments of “every concept”, as well as “of everything true in general” (EL Remark to §79; we will see why Hegel thought dialectics is in everything in section 3 ). The first moment—the moment of the understanding—is the moment of fixity, in which concepts or forms have a seemingly stable definition or determination (EL §80).

The second moment—the “ dialectical ” (EL §§79, 81) or “ negatively rational ” (EL §79) moment—is the moment of instability. In this moment, a one-sidedness or restrictedness (EL Remark to §81) in the determination from the moment of understanding comes to the fore, and the determination that was fixed in the first moment passes into its opposite (EL §81). Hegel describes this process as a process of “self-sublation” (EL §81). The English verb “to sublate” translates Hegel’s technical use of the German verb aufheben , which is a crucial concept in his dialectical method. Hegel says that aufheben has a doubled meaning: it means both to cancel (or negate) and to preserve at the same time (PhG §113; SL-M 107; SL-dG 81–2; cf. EL the Addition to §95). The moment of understanding sublates itself because its own character or nature—its one-sidedness or restrictedness—destabilizes its definition and leads it to pass into its opposite. The dialectical moment thus involves a process of self -sublation, or a process in which the determination from the moment of understanding sublates itself , or both cancels and preserves itself , as it pushes on to or passes into its opposite.

The third moment—the “ speculative ” or “ positively rational ” (EL §§79, 82) moment—grasps the unity of the opposition between the first two determinations, or is the positive result of the dissolution or transition of those determinations (EL §82 and Remark to §82). Here, Hegel rejects the traditional, reductio ad absurdum argument, which says that when the premises of an argument lead to a contradiction, then the premises must be discarded altogether, leaving nothing. As Hegel suggests in the Phenomenology , such an argument

is just the skepticism which only ever sees pure nothingness in its result and abstracts from the fact that this nothingness is specifically the nothingness of that from which it results . (PhG-M §79)

Although the speculative moment negates the contradiction, it is a determinate or defined nothingness because it is the result of a specific process. There is something particular about the determination in the moment of understanding—a specific weakness, or some specific aspect that was ignored in its one-sidedness or restrictedness—that leads it to fall apart in the dialectical moment. The speculative moment has a definition, determination or content because it grows out of and unifies the particular character of those earlier determinations, or is “a unity of distinct determinations ” (EL Remark to §82). The speculative moment is thus “truly not empty, abstract nothing , but the negation of certain determinations ” (EL-GSH §82). When the result “is taken as the result of that from which it emerges”, Hegel says, then it is “in fact, the true result; in that case it is itself a determinate nothingness, one which has a content” (PhG-M §79). As he also puts it, “the result is conceived as it is in truth, namely, as a determinate negation [ bestimmte Negation]; a new form has thereby immediately arisen” (PhG-M §79). Or, as he says, “[b]ecause the result, the negation, is a determinate negation [bestimmte Negation ], it has a content ” (SL-dG 33; cf. SL-M 54). Hegel’s claim in both the Phenomenology and the Science of Logic that his philosophy relies on a process of “ determinate negation [ bestimmte Negation]” has sometimes led scholars to describe his dialectics as a method or doctrine of “determinate negation” (see entry on Hegel, section on Science of Logic ; cf. Rosen 1982: 30; Stewart 1996, 2000: 41–3; Winfield 1990: 56).

There are several features of this account that Hegel thinks raise his dialectical method above the arbitrariness of Plato’s dialectics to the level of a genuine science. First, because the determinations in the moment of understanding sublate themselves , Hegel’s dialectics does not require some new idea to show up arbitrarily. Instead, the movement to new determinations is driven by the nature of the earlier determinations and so “comes about on its own accord” (PhG-P §79). Indeed, for Hegel, the movement is driven by necessity (see, e.g., EL Remarks to §§12, 42, 81, 87, 88; PhG §79). The natures of the determinations themselves drive or force them to pass into their opposites. This sense of necessity —the idea that the method involves being forced from earlier moments to later ones—leads Hegel to regard his dialectics as a kind of logic . As he says in the Phenomenology , the method’s “proper exposition belongs to logic” (PhG-M §48). Necessity—the sense of being driven or forced to conclusions—is the hallmark of “logic” in Western philosophy.

Second, because the form or determination that arises is the result of the self-sublation of the determination from the moment of understanding, there is no need for some new idea to show up from the outside. Instead, the transition to the new determination or form is necessitated by earlier moments and hence grows out of the process itself. Unlike in Plato’s arbitrary dialectics, then—which must wait around until some other idea comes in from the outside—in Hegel’s dialectics “nothing extraneous is introduced”, as he says (SL-M 54; cf. SL-dG 33). His dialectics is driven by the nature, immanence or “inwardness” of its own content (SL-M 54; cf. SL-dG 33; cf. PR §31). As he puts it, dialectics is “the principle through which alone immanent coherence and necessity enter into the content of science” (EL-GSH Remark to §81).

Third, because later determinations “sublate” earlier determinations, the earlier determinations are not completely cancelled or negated. On the contrary, the earlier determinations are preserved in the sense that they remain in effect within the later determinations. When Being-for-itself, for instance, is introduced in the logic as the first concept of ideality or universality and is defined by embracing a set of “something-others”, Being-for-itself replaces the something-others as the new concept, but those something-others remain active within the definition of the concept of Being-for-itself. The something-others must continue to do the work of picking out individual somethings before the concept of Being-for-itself can have its own definition as the concept that gathers them up. Being-for-itself replaces the something-others, but it also preserves them, because its definition still requires them to do their work of picking out individual somethings (EL §§95–6).

The concept of “apple”, for example, as a Being-for-itself, would be defined by gathering up individual “somethings” that are the same as one another (as apples). Each individual apple can be what it is (as an apple) only in relation to an “other” that is the same “something” that it is (i.e., an apple). That is the one-sidedness or restrictedness that leads each “something” to pass into its “other” or opposite. The “somethings” are thus both “something-others”. Moreover, their defining processes lead to an endless process of passing back and forth into one another: one “something” can be what it is (as an apple) only in relation to another “something” that is the same as it is, which, in turn, can be what it is (an apple) only in relation to the other “something” that is the same as it is, and so on, back and forth, endlessly (cf. EL §95). The concept of “apple”, as a Being-for-itself, stops that endless, passing-over process by embracing or including the individual something-others (the apples) in its content. It grasps or captures their character or quality as apples . But the “something-others” must do their work of picking out and separating those individual items (the apples) before the concept of “apple”—as the Being-for-itself—can gather them up for its own definition. We can picture the concept of Being-for-itself like this:

Later concepts thus replace, but also preserve, earlier concepts.

Fourth, later concepts both determine and also surpass the limits or finitude of earlier concepts. Earlier determinations sublate themselves —they pass into their others because of some weakness, one-sidedness or restrictedness in their own definitions. There are thus limitations in each of the determinations that lead them to pass into their opposites. As Hegel says, “that is what everything finite is: its own sublation” (EL-GSH Remark to §81). Later determinations define the finiteness of the earlier determinations. From the point of view of the concept of Being-for-itself, for instance, the concept of a “something-other” is limited or finite: although the something-others are supposed to be the same as one another, the character of their sameness (e.g., as apples) is captured only from above, by the higher-level, more universal concept of Being-for-itself. Being-for-itself reveals the limitations of the concept of a “something-other”. It also rises above those limitations, since it can do something that the concept of a something-other cannot do. Dialectics thus allows us to get beyond the finite to the universal. As Hegel puts it, “all genuine, nonexternal elevation above the finite is to be found in this principle [of dialectics]” (EL-GSH Remark to §81).

Fifth, because the determination in the speculative moment grasps the unity of the first two moments, Hegel’s dialectical method leads to concepts or forms that are increasingly comprehensive and universal. As Hegel puts it, the result of the dialectical process

is a new concept but one higher and richer than the preceding—richer because it negates or opposes the preceding and therefore contains it, and it contains even more than that, for it is the unity of itself and its opposite. (SL-dG 33; cf. SL-M 54)

Like Being-for-itself, later concepts are more universal because they unify or are built out of earlier determinations, and include those earlier determinations as part of their definitions. Indeed, many other concepts or determinations can also be depicted as literally surrounding earlier ones (cf. Maybee 2009: 73, 100, 112, 156, 193, 214, 221, 235, 458).

Finally, because the dialectical process leads to increasing comprehensiveness and universality, it ultimately produces a complete series, or drives “to completion” (SL-dG 33; cf. SL-M 54; PhG §79). Dialectics drives to the “Absolute”, to use Hegel’s term, which is the last, final, and completely all-encompassing or unconditioned concept or form in the relevant subject matter under discussion (logic, phenomenology, ethics/politics and so on). The “Absolute” concept or form is unconditioned because its definition or determination contains all the other concepts or forms that were developed earlier in the dialectical process for that subject matter. Moreover, because the process develops necessarily and comprehensively through each concept, form or determination, there are no determinations that are left out of the process. There are therefore no left-over concepts or forms—concepts or forms outside of the “Absolute”—that might “condition” or define it. The “Absolute” is thus unconditioned because it contains all of the conditions in its content, and is not conditioned by anything else outside of it. This Absolute is the highest concept or form of universality for that subject matter. It is the thought or concept of the whole conceptual system for the relevant subject matter. We can picture the Absolute Idea (EL §236), for instance—which is the “Absolute” for logic—as an oval that is filled up with and surrounds numerous, embedded rings of smaller ovals and circles, which represent all of the earlier and less universal determinations from the logical development (cf. Maybee 2009: 30, 600):

Since the “Absolute” concepts for each subject matter lead into one another, when they are taken together, they constitute Hegel’s entire philosophical system, which, as Hegel says, “presents itself therefore as a circle of circles” (EL-GSH §15). We can picture the entire system like this (cf. Maybee 2009: 29):

Together, Hegel believes, these characteristics make his dialectical method genuinely scientific. As he says, “the dialectical constitutes the moving soul of scientific progression” (EL-GSH Remark to §81). He acknowledges that a description of the method can be more or less complete and detailed, but because the method or progression is driven only by the subject matter itself, this dialectical method is the “only true method” (SL-M 54; SL-dG 33).

So far, we have seen how Hegel describes his dialectical method, but we have yet to see how we might read this method into the arguments he offers in his works. Scholars often use the first three stages of the logic as the “textbook example” (Forster 1993: 133) to illustrate how Hegel’s dialectical method should be applied to his arguments. The logic begins with the simple and immediate concept of pure Being, which is said to illustrate the moment of the understanding. We can think of Being here as a concept of pure presence. It is not mediated by any other concept—or is not defined in relation to any other concept—and so is undetermined or has no further determination (EL §86; SL-M 82; SL-dG 59). It asserts bare presence, but what that presence is like has no further determination. Because the thought of pure Being is undetermined and so is a pure abstraction, however, it is really no different from the assertion of pure negation or the absolutely negative (EL §87). It is therefore equally a Nothing (SL-M 82; SL-dG 59). Being’s lack of determination thus leads it to sublate itself and pass into the concept of Nothing (EL §87; SL-M 82; SL-dG 59), which illustrates the dialectical moment.

But if we focus for a moment on the definitions of Being and Nothing themselves, their definitions have the same content. Indeed, both are undetermined, so they have the same kind of undefined content. The only difference between them is “something merely meant ” (EL-GSH Remark to §87), namely, that Being is an undefined content, taken as or meant to be presence, while Nothing is an undefined content, taken as or meant to be absence. The third concept of the logic—which is used to illustrate the speculative moment—unifies the first two moments by capturing the positive result of—or the conclusion that we can draw from—the opposition between the first two moments. The concept of Becoming is the thought of an undefined content, taken as presence (Being) and then taken as absence (Nothing), or taken as absence (Nothing) and then taken as presence (Being). To Become is to go from Being to Nothing or from Nothing to Being, or is, as Hegel puts it, “the immediate vanishing of the one in the other” (SL-M 83; cf. SL-dG 60). The contradiction between Being and Nothing thus is not a reductio ad absurdum , or does not lead to the rejection of both concepts and hence to nothingness—as Hegel had said Plato’s dialectics does (SL-M 55–6; SL-dG 34–5)—but leads to a positive result, namely, to the introduction of a new concept—the synthesis—which unifies the two, earlier, opposed concepts.

We can also use the textbook Being-Nothing-Becoming example to illustrate Hegel’s concept of aufheben (to sublate), which, as we saw, means to cancel (or negate) and to preserve at the same time. Hegel says that the concept of Becoming sublates the concepts of Being and Nothing (SL-M 105; SL-dG 80). Becoming cancels or negates Being and Nothing because it is a new concept that replaces the earlier concepts; but it also preserves Being and Nothing because it relies on those earlier concepts for its own definition. Indeed, it is the first concrete concept in the logic. Unlike Being and Nothing, which had no definition or determination as concepts themselves and so were merely abstract (SL-M 82–3; SL-dG 59–60; cf. EL Addition to §88), Becoming is a “ determinate unity in which there is both Being and Nothing” (SL-M 105; cf. SL-dG 80). Becoming succeeds in having a definition or determination because it is defined by, or piggy-backs on, the concepts of Being and Nothing.

This “textbook” Being-Nothing-Becoming example is closely connected to the traditional idea that Hegel’s dialectics follows a thesis-antithesis-synthesis pattern, which, when applied to the logic, means that one concept is introduced as a “thesis” or positive concept, which then develops into a second concept that negates or is opposed to the first or is its “antithesis”, which in turn leads to a third concept, the “synthesis”, that unifies the first two (see, e.g., McTaggert 1964 [1910]: 3–4; Mure 1950: 302; Stace, 1955 [1924]: 90–3, 125–6; Kosek 1972: 243; E. Harris 1983: 93–7; Singer 1983: 77–79). Versions of this interpretation of Hegel’s dialectics continue to have currency (e.g., Forster 1993: 131; Stewart 2000: 39, 55; Fritzman 2014: 3–5). On this reading, Being is the positive moment or thesis, Nothing is the negative moment or antithesis, and Becoming is the moment of aufheben or synthesis—the concept that cancels and preserves, or unifies and combines, Being and Nothing.

We must be careful, however, not to apply this textbook example too dogmatically to the rest of Hegel’s logic or to his dialectical method more generally (for a classic criticism of the thesis-antithesis-synthesis reading of Hegel’s dialectics, see Mueller 1958). There are other places where this general pattern might describe some of the transitions from stage to stage, but there are many more places where the development does not seem to fit this pattern very well. One place where the pattern seems to hold, for instance, is where the Measure (EL §107)—as the combination of Quality and Quantity—transitions into the Measureless (EL §107), which is opposed to it, which then in turn transitions into Essence, which is the unity or combination of the two earlier sides (EL §111). This series of transitions could be said to follow the general pattern captured by the “textbook example”: Measure would be the moment of the understanding or thesis, the Measureless would be the dialectical moment or antithesis, and Essence would be the speculative moment or synthesis that unifies the two earlier moments. However, before the transition to Essence takes place, the Measureless itself is redefined as a Measure (EL §109)—undercutting a precise parallel with the textbook Being-Nothing-Becoming example, since the transition from Measure to Essence would not follow a Measure-Measureless-Essence pattern, but rather a Measure-(Measureless?)-Measure-Essence pattern.

Other sections of Hegel’s philosophy do not fit the triadic, textbook example of Being-Nothing-Becoming at all, as even interpreters who have supported the traditional reading of Hegel’s dialectics have noted. After using the Being-Nothing-Becoming example to argue that Hegel’s dialectical method consists of “triads” whose members “are called the thesis, antithesis, synthesis” (Stace 1955 [1924]: 93), W.T. Stace, for instance, goes on to warn us that Hegel does not succeed in applying this pattern throughout the philosophical system. It is hard to see, Stace says, how the middle term of some of Hegel’s triads are the opposites or antitheses of the first term, “and there are even ‘triads’ which contain four terms!” (Stace 1955 [1924]: 97). As a matter of fact, one section of Hegel’s logic—the section on Cognition—violates the thesis-antithesis-synthesis pattern because it has only two sub-divisions, rather than three. “The triad is incomplete”, Stace complains. “There is no third. Hegel here abandons the triadic method. Nor is any explanation of his having done so forthcoming” (Stace 1955 [1924]: 286; cf. McTaggart 1964 [1910]: 292).

Interpreters have offered various solutions to the complaint that Hegel’s dialectics sometimes seems to violate the triadic form. Some scholars apply the triadic form fairly loosely across several stages (e.g. Burbidge 1981: 43–5; Taylor 1975: 229–30). Others have applied Hegel’s triadic method to whole sections of his philosophy, rather than to individual stages. For G.R.G. Mure, for instance, the section on Cognition fits neatly into a triadic, thesis-antithesis-synthesis account of dialectics because the whole section is itself the antithesis of the previous section of Hegel’s logic, the section on Life (Mure 1950: 270). Mure argues that Hegel’s triadic form is easier to discern the more broadly we apply it. “The triadic form appears on many scales”, he says, “and the larger the scale we consider the more obvious it is” (Mure 1950: 302).

Scholars who interpret Hegel’s description of dialectics on a smaller scale—as an account of how to get from stage to stage—have also tried to explain why some sections seem to violate the triadic form. J.N. Findlay, for instance—who, like Stace, associates dialectics “with the triad , or with triplicity ”—argues that stages can fit into that form in “more than one sense” (Findlay 1962: 66). The first sense of triplicity echoes the textbook, Being-Nothing-Becoming example. In a second sense, however, Findlay says, the dialectical moment or “contradictory breakdown” is not itself a separate stage, or “does not count as one of the stages”, but is a transition between opposed, “but complementary”, abstract stages that “are developed more or less concurrently” (Findlay 1962: 66). This second sort of triplicity could involve any number of stages: it “could readily have been expanded into a quadruplicity, a quintuplicity and so forth” (Findlay 1962: 66). Still, like Stace, he goes on to complain that many of the transitions in Hegel’s philosophy do not seem to fit the triadic pattern very well. In some triads, the second term is “the direct and obvious contrary of the first”—as in the case of Being and Nothing. In other cases, however, the opposition is, as Findlay puts it, “of a much less extreme character” (Findlay 1962: 69). In some triads, the third term obviously mediates between the first two terms. In other cases, however, he says, the third term is just one possible mediator or unity among other possible ones; and, in yet other cases, “the reconciling functions of the third member are not at all obvious” (Findlay 1962: 70).

Let us look more closely at one place where the “textbook example” of Being-Nothing-Becoming does not seem to describe the dialectical development of Hegel’s logic very well. In a later stage of the logic, the concept of Purpose goes through several iterations, from Abstract Purpose (EL §204), to Finite or Immediate Purpose (EL §205), and then through several stages of a syllogism (EL §206) to Realized Purpose (EL §210). Abstract Purpose is the thought of any kind of purposiveness, where the purpose has not been further determined or defined. It includes not just the kinds of purposes that occur in consciousness, such as needs or drives, but also the “internal purposiveness” or teleological view proposed by the ancient Greek philosopher, Aristotle (see entry on Aristotle ; EL Remark to §204), according to which things in the world have essences and aim to achieve (or have the purpose of living up to) their essences. Finite Purpose is the moment in which an Abstract Purpose begins to have a determination by fixing on some particular material or content through which it will be realized (EL §205). The Finite Purpose then goes through a process in which it, as the Universality, comes to realize itself as the Purpose over the particular material or content (and hence becomes Realized Purpose) by pushing out into Particularity, then into Singularity (the syllogism U-P-S), and ultimately into ‘out-thereness,’ or into individual objects out there in the world (EL §210; cf. Maybee 2009: 466–493).

Hegel’s description of the development of Purpose does not seem to fit the textbook Being-Nothing-Becoming example or the thesis-antithesis-synthesis model. According to the example and model, Abstract Purpose would be the moment of understanding or thesis, Finite Purpose would be the dialectical moment or antithesis, and Realized Purpose would be the speculative moment or synthesis. Although Finite Purpose has a different determination from Abstract Purpose (it refines the definition of Abstract Purpose), it is hard to see how it would qualify as strictly “opposed” to or as the “antithesis” of Abstract Purpose in the way that Nothing is opposed to or is the antithesis of Being.

There is an answer, however, to the criticism that many of the determinations are not “opposites” in a strict sense. The German term that is translated as “opposite” in Hegel’s description of the moments of dialectics (EL §§81, 82)— entgegensetzen —has three root words: setzen (“to posit or set”), gegen , (“against”), and the prefix ent -, which indicates that something has entered into a new state. The verb entgegensetzen can therefore literally be translated as “to set over against”. The “ engegengesetzte ” into which determinations pass, then, do not need to be the strict “opposites” of the first, but can be determinations that are merely “set against” or are different from the first ones. And the prefix ent -, which suggests that the first determinations are put into a new state, can be explained by Hegel’s claim that the finite determinations from the moment of understanding sublate (cancel but also preserve) themselves (EL §81): later determinations put earlier determinations into a new state by preserving them.

At the same time, there is a technical sense in which a later determination would still be the “opposite” of the earlier determination. Since the second determination is different from the first one, it is the logical negation of the first one, or is not -the-first-determination. If the first determination is “e”, for instance, because the new determination is different from that one, the new one is “not-e” (Kosek 1972: 240). Since Finite Purpose, for instance, has a definition or determination that is different from the definition that Abstract Purpose has, it is not -Abstract-Purpose, or is the negation or opposite of Abstract Purpose in that sense. There is therefore a technical, logical sense in which the second concept or form is the “opposite” or negation of—or is “not”—the first one—though, again, it need not be the “opposite” of the first one in a strict sense.

Other problems remain, however. Because the concept of Realized Purpose is defined through a syllogistic process, it is itself the product of several stages of development (at least four, by my count, if Realized Purpose counts as a separate determination), which would seem to violate a triadic model. Moreover, the concept of Realized Purpose does not, strictly speaking, seem to be the unity or combination of Abstract Purpose and Finite Purpose. Realized Purpose is the result of (and so unifies) the syllogistic process of Finite Purpose, through which Finite Purpose focuses on and is realized in a particular material or content. Realized Purpose thus seems to be a development of Finite Purpose, rather than a unity or combination of Abstract Purpose and Finite Purpose, in the way that Becoming can be said to be the unity or combination of Being and Nothing.

These sorts of considerations have led some scholars to interpret Hegel’s dialectics in a way that is implied by a more literal reading of his claim, in the Encyclopaedia Logic , that the three “sides” of the form of logic—namely, the moment of understanding, the dialectical moment, and the speculative moment—“are moments of each [or every; jedes ] logically-real , that is each [or every; jedes ] concept” (EL Remark to §79; this is an alternative translation). The quotation suggests that each concept goes through all three moments of the dialectical process—a suggestion reinforced by Hegel’s claim, in the Phenomenology , that the result of the process of determinate negation is that “a new form has thereby immediately arisen” (PhG-M §79). According to this interpretation, the three “sides” are not three different concepts or forms that are related to one another in a triad—as the textbook Being-Nothing-Becoming example suggests—but rather different momentary sides or “determinations” in the life, so to speak, of each concept or form as it transitions to the next one. The three moments thus involve only two concepts or forms: the one that comes first, and the one that comes next (examples of philosophers who interpret Hegel’s dialectics in this second way include Maybee 2009; Priest 1989: 402; Rosen 2014: 122, 132; and Winfield 1990: 56).

For the concept of Being, for example, its moment of understanding is its moment of stability, in which it is asserted to be pure presence. This determination is one-sided or restricted however, because, as we saw, it ignores another aspect of Being’s definition, namely, that Being has no content or determination, which is how Being is defined in its dialectical moment. Being thus sublates itself because the one-sidedness of its moment of understanding undermines that determination and leads to the definition it has in the dialectical moment. The speculative moment draws out the implications of these moments: it asserts that Being (as pure presence) implies nothing. It is also the “unity of the determinations in their comparison [ Entgegensetzung ]” (EL §82; alternative translation): since it captures a process from one to the other, it includes Being’s moment of understanding (as pure presence) and dialectical moment (as nothing or undetermined), but also compares those two determinations, or sets (- setzen ) them up against (- gegen ) each other. It even puts Being into a new state (as the prefix ent - suggests) because the next concept, Nothing, will sublate (cancel and preserve) Being.

The concept of Nothing also has all three moments. When it is asserted to be the speculative result of the concept of Being, it has its moment of understanding or stability: it is Nothing, defined as pure absence, as the absence of determination. But Nothing’s moment of understanding is also one-sided or restricted: like Being, Nothing is also an undefined content, which is its determination in its dialectical moment. Nothing thus sublates itself : since it is an undefined content , it is not pure absence after all, but has the same presence that Being did. It is present as an undefined content . Nothing thus sublates Being: it replaces (cancels) Being, but also preserves Being insofar as it has the same definition (as an undefined content) and presence that Being had. We can picture Being and Nothing like this (the circles have dashed outlines to indicate that, as concepts, they are each undefined; cf. Maybee 2009: 51):

In its speculative moment, then, Nothing implies presence or Being, which is the “unity of the determinations in their comparison [ Entgegensetzung ]” (EL §82; alternative translation), since it both includes but—as a process from one to the other—also compares the two earlier determinations of Nothing, first, as pure absence and, second, as just as much presence.

The dialectical process is driven to the next concept or form—Becoming—not by a triadic, thesis-antithesis-synthesis pattern, but by the one-sidedness of Nothing—which leads Nothing to sublate itself—and by the implications of the process so far. Since Being and Nothing have each been exhaustively analyzed as separate concepts, and since they are the only concepts in play, there is only one way for the dialectical process to move forward: whatever concept comes next will have to take account of both Being and Nothing at the same time. Moreover, the process revealed that an undefined content taken to be presence (i.e., Being) implies Nothing (or absence), and that an undefined content taken to be absence (i.e., Nothing) implies presence (i.e., Being). The next concept, then, takes Being and Nothing together and draws out those implications—namely, that Being implies Nothing, and that Nothing implies Being. It is therefore Becoming, defined as two separate processes: one in which Being becomes Nothing, and one in which Nothing becomes Being. We can picture Becoming this way (cf. Maybee 2009: 53):

In a similar way, a one-sidedness or restrictedness in the determination of Finite Purpose together with the implications of earlier stages leads to Realized Purpose. In its moment of understanding, Finite Purpose particularizes into (or presents) its content as “ something-presupposed ” or as a pre-given object (EL §205). I go to a restaurant for the purpose of having dinner, for instance, and order a salad. My purpose of having dinner particularizes as a pre-given object—the salad. But this object or particularity—e.g. the salad—is “inwardly reflected” (EL §205): it has its own content—developed in earlier stages—which the definition of Finite Purpose ignores. We can picture Finite Purpose this way:

In the dialectical moment, Finite Purpose is determined by the previously ignored content, or by that other content. The one-sidedness of Finite Purpose requires the dialectical process to continue through a series of syllogisms that determines Finite Purpose in relation to the ignored content. The first syllogism links the Finite Purpose to the first layer of content in the object: the Purpose or universality (e.g., dinner) goes through the particularity (e.g., the salad) to its content, the singularity (e.g., lettuce as a type of thing)—the syllogism U-P-S (EL §206). But the particularity (e.g., the salad) is itself a universality or purpose, “which at the same time is a syllogism within itself [ in sich ]” (EL Remark to §208; alternative translation), in relation to its own content. The salad is a universality/purpose that particularizes as lettuce (as a type of thing) and has its singularity in this lettuce here—a second syllogism, U-P-S. Thus, the first singularity (e.g., “lettuce” as a type of thing)—which, in this second syllogism, is the particularity or P —“ judges ” (EL §207) or asserts that “ U is S ”: it says that “lettuce” as a universality ( U ) or type of thing is a singularity ( S ), or is “this lettuce here”, for instance. This new singularity (e.g. “this lettuce here”) is itself a combination of subjectivity and objectivity (EL §207): it is an Inner or identifying concept (“lettuce”) that is in a mutually-defining relationship (the circular arrow) with an Outer or out-thereness (“this here”) as its content. In the speculative moment, Finite Purpose is determined by the whole process of development from the moment of understanding—when it is defined by particularizing into a pre-given object with a content that it ignores—to its dialectical moment—when it is also defined by the previously ignored content. We can picture the speculative moment of Finite Purpose this way:

Finite Purpose’s speculative moment leads to Realized Purpose. As soon as Finite Purpose presents all the content, there is a return process (a series of return arrows) that establishes each layer and redefines Finite Purpose as Realized Purpose. The presence of “this lettuce here” establishes the actuality of “lettuce” as a type of thing (an Actuality is a concept that captures a mutually-defining relationship between an Inner and an Outer [EL §142]), which establishes the “salad”, which establishes “dinner” as the Realized Purpose over the whole process. We can picture Realized Purpose this way:

If Hegel’s account of dialectics is a general description of the life of each concept or form, then any section can include as many or as few stages as the development requires. Instead of trying to squeeze the stages into a triadic form (cf. Solomon 1983: 22)—a technique Hegel himself rejects (PhG §50; cf. section 3 )—we can see the process as driven by each determination on its own account: what it succeeds in grasping (which allows it to be stable, for a moment of understanding), what it fails to grasp or capture (in its dialectical moment), and how it leads (in its speculative moment) to a new concept or form that tries to correct for the one-sidedness of the moment of understanding. This sort of process might reveal a kind of argument that, as Hegel had promised, might produce a comprehensive and exhaustive exploration of every concept, form or determination in each subject matter, as well as raise dialectics above a haphazard analysis of various philosophical views to the level of a genuine science.

We can begin to see why Hegel was motivated to use a dialectical method by examining the project he set for himself, particularly in relation to the work of David Hume and Immanuel Kant (see entries on Hume and Kant ). Hume had argued against what we can think of as the naïve view of how we come to have scientific knowledge. According to the naïve view, we gain knowledge of the world by using our senses to pull the world into our heads, so to speak. Although we may have to use careful observations and do experiments, our knowledge of the world is basically a mirror or copy of what the world is like. Hume argued, however, that naïve science’s claim that our knowledge corresponds to or copies what the world is like does not work. Take the scientific concept of cause, for instance. According to that concept of cause, to say that one event causes another is to say that there is a necessary connection between the first event (the cause) and the second event (the effect), such that, when the first event happens, the second event must also happen. According to naïve science, when we claim (or know) that some event causes some other event, our claim mirrors or copies what the world is like. It follows that the necessary, causal connection between the two events must itself be out there in the world. However, Hume argued, we never observe any such necessary causal connection in our experience of the world, nor can we infer that one exists based on our reasoning (see Hume’s A Treatise of Human Nature , Book I, Part III, Section II; Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding , Section VII, Part I). There is nothing in the world itself that our idea of cause mirrors or copies.

Kant thought Hume’s argument led to an unacceptable, skeptical conclusion, and he rejected Hume’s own solution to the skepticism (see Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason , B5, B19–20). Hume suggested that our idea of causal necessity is grounded merely in custom or habit, since it is generated by our own imaginations after repeated observations of one sort of event following another sort of event (see Hume’s A Treatise of Human Nature , Book I, Section VI; Hegel also rejected Hume’s solution, see EL §39). For Kant, science and knowledge should be grounded in reason, and he proposed a solution that aimed to reestablish the connection between reason and knowledge that was broken by Hume’s skeptical argument. Kant’s solution involved proposing a Copernican revolution in philosophy ( Critique of Pure Reason , Bxvi). Nicholas Copernicus was the Polish astronomer who said that the earth revolves around the sun, rather than the other way around. Kant proposed a similar solution to Hume’s skepticism. Naïve science assumes that our knowledge revolves around what the world is like, but, Hume’s criticism argued, this view entails that we cannot then have knowledge of scientific causes through reason. We can reestablish a connection between reason and knowledge, however, Kant suggested, if we say—not that knowledge revolves around what the world is like—but that knowledge revolves around what we are like . For the purposes of our knowledge, Kant said, we do not revolve around the world—the world revolves around us. Because we are rational creatures, we share a cognitive structure with one another that regularizes our experiences of the world. This intersubjectively shared structure of rationality—and not the world itself—grounds our knowledge.

However, Kant’s solution to Hume’s skepticism led to a skeptical conclusion of its own that Hegel rejected. While the intersubjectively shared structure of our reason might allow us to have knowledge of the world from our perspective, so to speak, we cannot get outside of our mental, rational structures to see what the world might be like in itself. As Kant had to admit, according to his theory, there is still a world in itself or “Thing-in-itself” ( Ding an sich ) about which we can know nothing (see, e.g., Critique of Pure Reason , Bxxv–xxvi). Hegel rejected Kant’s skeptical conclusion that we can know nothing about the world- or Thing-in-itself, and he intended his own philosophy to be a response to this view (see, e.g., EL §44 and the Remark to §44).

How did Hegel respond to Kant’s skepticism—especially since Hegel accepted Kant’s Copernican revolution, or Kant’s claim that we have knowledge of the world because of what we are like, because of our reason? How, for Hegel, can we get out of our heads to see the world as it is in itself? Hegel’s answer is very close to the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle’s response to Plato. Plato argued that we have knowledge of the world only through the Forms. The Forms are perfectly universal, rational concepts or ideas. Because the world is imperfect, however, Plato exiled the Forms to their own realm. Although things in the world get their definitions by participating in the Forms, those things are, at best, imperfect copies of the universal Forms (see, e.g., Parmenides 131–135a). The Forms are therefore not in this world, but in a separate realm of their own. Aristotle argued, however, that the world is knowable not because things in the world are imperfect copies of the Forms, but because the Forms are in things themselves as the defining essences of those things (see, e.g., De Anima [ On the Soul ], Book I, Chapter 1 [403a26–403b18]; Metaphysics , Book VII, Chapter 6 [1031b6–1032a5] and Chapter 8 [1033b20–1034a8]).

In a similar way, Hegel’s answer to Kant is that we can get out of our heads to see what the world is like in itself—and hence can have knowledge of the world in itself—because the very same rationality or reason that is in our heads is in the world itself . As Hegel apparently put it in a lecture, the opposition or antithesis between the subjective and objective disappears by saying, as the Ancients did,

that nous governs the world, or by our own saying that there is reason in the world, by which we mean that reason is the soul of the world, inhabits it, and is immanent in it, as it own, innermost nature, its universal. (EL-GSH Addition 1 to §24)

Hegel used an example familiar from Aristotle’s work to illustrate this view:

“to be an animal”, the kind considered as the universal, pertains to the determinate animal and constitutes its determinate essentiality. If we were to deprive a dog of its animality we could not say what it is. (EL-GSH Addition 1 to §24; cf. SL-dG 16–17, SL-M 36-37)

Kant’s mistake, then, was that he regarded reason or rationality as only in our heads, Hegel suggests (EL §§43–44), rather than in both us and the world itself (see also below in this section and section 4 ). We can use our reason to have knowledge of the world because the very same reason that is in us, is in the world itself as it own defining principle. The rationality or reason in the world makes reality understandable, and that is why we can have knowledge of, or can understand, reality with our rationality. Dialectics—which is Hegel’s account of reason—characterizes not only logic, but also “everything true in general” (EL Remark to §79).

But why does Hegel come to define reason in terms of dialectics, and hence adopt a dialectical method? We can begin to see what drove Hegel to adopt a dialectical method by returning once again to Plato’s philosophy. Plato argued that we can have knowledge of the world only by grasping the Forms, which are perfectly universal, rational concepts or ideas. Because things in the world are so imperfect, however, Plato concluded that the Forms are not in this world, but in a realm of their own. After all, if a human being were perfectly beautiful, for instance, then he or she would never become not-beautiful. But human beings change, get old, and die, and so can be, at best, imperfect copies of the Form of beauty—though they get whatever beauty they have by participating in that Form. Moreover, for Plato, things in the world are such imperfect copies that we cannot gain knowledge of the Forms by studying things in the world, but only through reason, that is, only by using our rationality to access the separate realm of the Forms (as Plato argued in the well-known parable of the cave; Republic , Book 7, 514–516b).

Notice, however, that Plato’s conclusion that the Forms cannot be in this world and so must be exiled to a separate realm rests on two claims. First, it rests on the claim that the world is an imperfect and messy place—a claim that is hard to deny. But it also rests on the assumption that the Forms—the universal, rational concepts or ideas of reason itself—are static and fixed, and so cannot grasp the messiness within the imperfect world. Hegel is able to link reason back to our messy world by changing the definition of reason. Instead of saying that reason consists of static universals, concepts or ideas, Hegel says that the universal concepts or forms are themselves messy . Against Plato, Hegel’s dialectical method allows him to argue that universal concepts can “overgrasp” (from the German verb übergreifen ) the messy, dialectical nature of the world because they, themselves, are dialectical . Moreover, because later concepts build on or sublate (cancel, but also preserve) earlier concepts, the later, more universal concepts grasp the dialectical processes of earlier concepts. As a result, higher-level concepts can grasp not only the dialectical nature of earlier concepts or forms, but also the dialectical processes that make the world itself a messy place. The highest definition of the concept of beauty, for instance, would not take beauty to be fixed and static, but would include within it the dialectical nature or finiteness of beauty, the idea that beauty becomes, on its own account, not-beauty. This dialectical understanding of the concept of beauty can then overgrasp the dialectical and finite nature of beauty in the world, and hence the truth that, in the world, beautiful things themselves become not-beautiful, or might be beautiful in one respect and not another. Similarly, the highest determination of the concept of “tree” will include within its definition the dialectical process of development and change from seed to sapling to tree. As Hegel says, dialectics is “the principle of all natural and spiritual life” (SL-M 56; SL-dG 35), or “the moving soul of scientific progression” (EL §81). Dialectics is what drives the development of both reason as well as of things in the world. A dialectical reason can overgrasp a dialectical world.

Two further journeys into the history of philosophy will help to show why Hegel chose dialectics as his method of argument. As we saw, Hegel argues against Kant’s skepticism by suggesting that reason is not only in our heads, but in the world itself. To show that reason is in the world itself, however, Hegel has to show that reason can be what it is without us human beings to help it. He has to show that reason can develop on its own, and does not need us to do the developing for it (at least for those things in the world that are not human-created). As we saw (cf. section 1 ), central to Hegel’s dialectics is the idea that concepts or forms develop on their own because they “self-sublate”, or sublate (cancel and preserve) themselves , and so pass into subsequent concepts or forms on their own accounts, because of their own, dialectical natures. Thus reason, as it were, drives itself, and hence does not need our heads to develop it. Hegel needs an account of self-driving reason to get beyond Kant’s skepticism.

Ironically, Hegel derives the basic outlines of his account of self-driving reason from Kant. Kant divided human rationality into two faculties: the faculty of the understanding and the faculty of reason. The understanding uses concepts to organize and regularize our experiences of the world. Reason’s job is to coordinate the concepts and categories of the understanding by developing a completely unified, conceptual system, and it does this work, Kant thought, on its own, independently of how those concepts might apply to the world. Reason coordinates the concepts of the understanding by following out necessary chains of syllogisms to produce concepts that achieve higher and higher levels of conceptual unity. Indeed, this process will lead reason to produce its own transcendental ideas, or concepts that go beyond the world of experience. Kant calls this necessary, concept-creating reason “speculative” reason (cf. Critique of Pure Reason , Bxx–xxi, A327/B384). Reason creates its own concepts or ideas—it “speculates”—by generating new and increasingly comprehensive concepts of its own, independently of the understanding. In the end, Kant thought, reason will follow out such chains of syllogisms until it develops completely comprehensive or unconditioned universals—universals that contain all of the conditions or all of the less-comprehensive concepts that help to define them. As we saw (cf. section 1 ), Hegel’s dialectics adopts Kant’s notion of a self-driving and concept-creating “speculative” reason, as well as Kant’s idea that reason aims toward unconditioned universality or absolute concepts.

Ultimately, Kant thought, reasons’ necessary, self-driving activity will lead it to produce contradictions—what he called the “antinomies”, which consist of a thesis and antithesis. Once reason has generated the unconditioned concept of the whole world, for instance, Kant argued, it can look at the world in two, contradictory ways. In the first antinomy, reason can see the world (1) as the whole totality or as the unconditioned, or (2) as the series of syllogisms that led up to that totality. If reason sees the world as the unconditioned or as a complete whole that is not conditioned by anything else, then it will see the world as having a beginning and end in terms of space and time, and so will conclude (the thesis) that the world has a beginning and end or limit. But if reason sees the world as the series, in which each member of the series is conditioned by the previous member, then the world will appear to be without a beginning and infinite, and reason will conclude (the antithesis) that the world does not have a limit in terms of space and time (cf. Critique of Pure Reason , A417–18/B445–6). Reason thus leads to a contradiction: it holds both that the world has a limit and that it does not have a limit at the same time. Because reason’s own process of self-development will lead it to develop contradictions or to be dialectical in this way, Kant thought that reason must be kept in check by the understanding. Any conclusions that reason draws that do not fall within the purview of the understanding cannot be applied to the world of experience, Kant said, and so cannot be considered genuine knowledge ( Critique of Pure Reason , A506/B534).

Hegel adopts Kant’s dialectical conception of reason, but he liberates reason for knowledge from the tyranny of the understanding. Kant was right that reason speculatively generates concepts on its own, and that this speculative process is driven by necessity and leads to concepts of increasing universality or comprehensiveness. Kant was even right to suggest—as he had shown in the discussion of the antinomies—that reason is dialectical, or necessarily produces contradictions on its own. Again, Kant’s mistake was that he fell short of saying that these contradictions are in the world itself. He failed to apply the insights of his discussion of the antinomies to “ things in themselves ” (SL-M 56; SL-dG 35; see also section 4 ). Indeed, Kant’s own argument proves that the dialectical nature of reason can be applied to things themselves. The fact that reason develops those contradictions on its own, without our heads to help it , shows that those contradictions are not just in our heads, but are objective, or in the world itself. Kant, however, failed to draw this conclusion, and continued to regard reason’s conclusions as illusions. Still, Kant’s philosophy vindicated the general idea that the contradictions he took to be illusions are both objective—or out there in the world—and necessary. As Hegel puts it, Kant vindicates the general idea of “the objectivity of the illusion and the necessity of the contradiction which belongs to the nature of thought determinations” (SL-M 56; cf. SL-dG 35), or to the nature of concepts themselves.

The work of Johann Gottlieb Fichte (see entry on Fichte ) showed Hegel how dialectics can get beyond Kant—beyond the contradictions that, as Kant had shown, reason (necessarily) develops on its own, beyond the reductio ad absurdum argument (which, as we saw above, holds that a contradiction leads to nothingness), and beyond Kant’s skepticism, or Kant’s claim that reason’s contradictions must be reined in by the understanding and cannot count as knowledge. Fichte argued that the task of discovering the foundation of all human knowledge leads to a contradiction or opposition between the self and the not-self (it is not important, for our purposes, why Fichte held this view). The kind of reasoning that leads to this contradiction, Fichte said, is the analytical or antithetical method of reasoning, which involves drawing out an opposition between elements (in this case, the self and not-self) that are being compared to, or equated with, one another. While the traditional reductio ad absurdum argument would lead us to reject both sides of the contradiction and start from scratch, Fichte argued that the contradiction or opposition between the self and not-self can be resolved. In particular, the contradiction is resolved by positing a third concept—the concept of divisibility—which unites the two sides ( The Science of Knowledge , I: 110–11; Fichte 1982: 108–110). The concept of divisibility is produced by a synthetic procedure of reasoning, which involves “discovering in opposites the respect in which they are alike ” ( The Science of Knowledge , I: 112–13; Fichte 1982: 111). Indeed, Fichte argued, not only is the move to resolve contradictions with synthetic concepts or judgments possible, it is necessary . As he says of the move from the contradiction between self and not-self to the synthetic concept of divisibility,

there can be no further question as to the possibility of this [synthesis], nor can any ground for it be given; it is absolutely possible, and we are entitled to it without further grounds of any kind. ( The Science of Knowledge , I: 114; Fichte 1982: 112)

Since the analytical method leads to oppositions or contradictions, he argued, if we use only analytic judgments, “we not only do not get very far, as Kant says; we do not get anywhere at all” ( The Science of Knowledge , I: 113; Fichte 1982: 112). Without the synthetic concepts or judgments, we are left, as the classic reductio ad absurdum argument suggests, with nothing at all. The synthetic concepts or judgments are thus necessary to get beyond contradiction without leaving us with nothing.

Fichte’s account of the synthetic method provides Hegel with the key to moving beyond Kant. Fichte suggested that a synthetic concept that unifies the results of a dialectically-generated contradiction does not completely cancel the contradictory sides, but only limits them. As he said, in general, “[t]o limit something is to abolish its reality, not wholly , but in part only” ( The Science of Knowledge , I: 108; Fichte 1982: 108). Instead of concluding, as a reductio ad absurdum requires, that the two sides of a contradiction must be dismissed altogether, the synthetic concept or judgment retroactively justifies the opposing sides by demonstrating their limit, by showing which part of reality they attach to and which they do not ( The Science of Knowledge , I: 108–10; Fichte 1982: 108–9), or by determining in what respect and to what degree they are each true. For Hegel, as we saw (cf. section 1 ), later concepts and forms sublate—both cancel and preserve —earlier concepts and forms in the sense that they include earlier concepts and forms in their own definitions. From the point of view of the later concepts or forms, the earlier ones still have some validity, that is, they have a limited validity or truth defined by the higher-level concept or form.

Dialectically generated contradictions are therefore not a defect to be reigned in by the understanding, as Kant had said, but invitations for reason to “speculate”, that is, for reason to generate precisely the sort of increasingly comprehensive and universal concepts and forms that Kant had said reason aims to develop. Ultimately, Hegel thought, as we saw (cf. section 1 ), the dialectical process leads to a completely unconditioned concept or form for each subject matter—the Absolute Idea (logic), Absolute Spirit (phenomenology), Absolute Idea of right and law ( Philosophy of Right ), and so on—which, taken together, form the “circle of circles” (EL §15) that constitutes the whole philosophical system or “Idea” (EL §15) that both overgrasps the world and makes it understandable (for us).

Note that, while Hegel was clearly influenced by Fichte’s work, he never adopted Fichte’s triadic “thesis—antithesis—synthesis” language in his descriptions of his own philosophy (Mueller 1958: 411–2; Solomon 1983: 23), though he did apparently use it in his lectures to describe Kant’s philosophy (LHP III: 477). Indeed, Hegel criticized formalistic uses of the method of “ triplicity [Triplizität]” (PhG-P §50) inspired by Kant—a criticism that could well have been aimed at Fichte. Hegel argued that Kantian-inspired uses of triadic form had been reduced to “a lifeless schema” and “an actual semblance [ eigentlichen Scheinen ]” (PhG §50; alternative translation) that, like a formula in mathematics, was simply imposed on top of subject matters. Instead, a properly scientific use of Kant’s “triplicity” should flow—as he said his own dialectical method did (see section 1 )—out of “the inner life and self-movement” (PhG §51) of the content.

Scholars have often questioned whether Hegel’s dialectical method is logical. Some of their skepticism grows out of the role that contradiction plays in his thought and argument. While many of the oppositions embedded in the dialectical development and the definitions of concepts or forms are not contradictions in the strict sense, as we saw ( section 2 , above), scholars such as Graham Priest have suggested that some of them arguably are (Priest 1989: 391). Hegel even holds, against Kant (cf. section 3 above), that there are contradictions, not only in thought, but also in the world. Motion, for instance, Hegel says, is an “ existent contradiction”. As he describes it:

Something moves, not because now it is here and there at another now, but because in one and the same now it is here and not here, because in this here, it is and is not at the same time. (SL-dG 382; cf. SL-M 440)

Kant’s sorts of antinomies (cf. section 3 above) or contradictions more generally are therefore, as Hegel puts it in one place, “in all objects of all kinds, in all representations, concepts and ideas” (EL-GSH Remark to §48). Hegel thus seems to reject, as he himself explicitly claims (SL-M 439–40; SL-dG 381–82), the law of non-contradiction, which is a fundamental principle of formal logic—the classical, Aristotelian logic (see entries on Aristotle’s Logic and Contradiction ) that dominated during Hegel’s lifetime as well as the dominant systems of symbolic logic today (cf. Priest 1989: 391; Düsing 2010: 97–103). According to the law of non-contradiction, something cannot be both true and false at the same time or, put another way, “x” and “not-x” cannot both be true at the same time.

Hegel’s apparent rejection of the law of non-contradiction has led some interpreters to regard his dialectics as illogical, even “absurd” (Popper 1940: 420; 1962: 330; 2002: 443). Karl R. Popper, for instance, argued that accepting Hegel’s and other dialecticians’ rejection of the law of non-contradiction as part of both a logical theory and a general theory of the world “would mean a complete breakdown of science” (Popper 1940: 408; 1962: 317; 2002: 426). Since, according to today’s systems of symbolic logic, he suggested, the truth of a contradiction leads logically to any claim (any claim can logically be inferred from two contradictory claims), if we allow contradictory claims to be valid or true together, then we would have no reason to rule out any claim whatsoever (Popper 1940: 408–410; 1962: 317–319; 2002: 426–429).

Popper was notoriously hostile toward Hegel’s work (cf. Popper 2013: 242–289; for a scathing criticism of Popper’s analysis see Kaufmann 1976 [1972]), but, as Priest has noted (Priest 1989: 389–91), even some sympathetic interpreters have been inspired by today’s dominant systems of symbolic logic to hold that the kind of contradiction that is embedded in Hegel’s dialectics cannot be genuine contradiction in the strict sense. While Dieter Wandschneider, for instance, grants that his sympathetic theory of dialectic “is not presented as a faithful interpretation of the Hegelian text” (Wandschneider 2010: 32), he uses the same logical argument that Popper offered in defense of the claim that “dialectical contradiction is not a ‘normal’ contradiction, but one that is actually only an apparent contradiction” (Wandschneider 2010: 37). The suggestion (by the traditional, triadic account of Hegel’s dialectics, cf. section 2 , above) that Being and Nothing (or non-being) is a contradiction, for instance, he says, rests on an ambiguity. Being is an undefined content, taken to mean being or presence, while Nothing is an undefined content, taken to mean nothing or absence ( section 2 , above; cf. Wandschneider 2010: 34–35). Being is Nothing (or non-being) with respect to the property they have as concepts, namely, that they both have an undefined content. But Being is not Nothing (or non-being) with respect to their meaning (Wandschneider 2010: 34–38). The supposed contradiction between them, then, Wandschneider suggests, takes place “in different respects ”. It is therefore only an apparent contradiction. “Rightly understood”, he concludes, “there can be no talk of contradiction ” (Wandschneider 2010: 38).