Research Philosophy

Research philosophy is a vast topic and here we will not be discussing this topic in great details. Research philosophy is associated with assumption, knowledge and nature of the study. It deals with the specific way of developing knowledge. This matter needs to be addressed because researchers may have different assumptions about the nature of truth and knowledge and philosophy helps us to understand their assumptions.

In business and economics dissertations at Bachelor’s level, you are not expected to discuss research philosophy in a great level of depth, and about one page in methodology chapter devoted to research philosophy usually suffices. For a business dissertation at Master’s level, on the other hand, you may need to provide more discussion of the philosophy of your study. But even there, about two pages of discussions are usually accepted as sufficient by supervisors.

Discussion of research philosophy in your dissertation should include the following:

- You need to specify the research philosophy of your study. Your research philosophy can be pragmatism , positivism , realism or interpretivism as discussed below in more details.

- The reasons behind philosophical classifications of the study need to be provided.

- You need to discuss the implications of your research philosophy on the research strategy in general and the choice of primary data collection methods in particular.

The Essence of Research Philosophy

Research philosophy deals with the source, nature and development of knowledge [1] . In simple terms, research philosophy is belief about the ways in which data about a phenomenon should be collected, analysed and used.

Although the idea of knowledge creation may appear to be profound, you are engaged in knowledge creation as part of completing your dissertation. You will collect secondary and primary data and engage in data analysis to answer the research question and this answer marks the creation of new knowledge.

In respect to business and economics philosophy has the following important three functions [2] :

- Demystifying : Exposing, criticising and explaining the unsustainable assumptions, inconsistencies and confusions these may contain.

- Informing : Helping researchers to understand where they stand in the wider field of knowledge-producing activities, and helping to make them aware of potentialities they might explore.

- Method-facilitating : Dissecting and better understanding the methods which economists or, more generally, scientists do, or could, use, and thereby to refine the methods on offer and/or to clarify their conditions of usage.

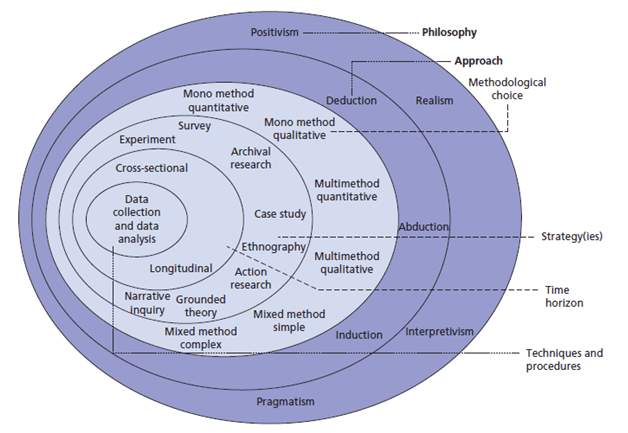

In essence, addressing research philosophy in your dissertation involves being aware and formulating your beliefs and assumptions. As illustrated in figure below, the identification of research philosophy is positioned at the outer layer of the ‘research onion’. Accordingly it is the first topic to be clarified in research methodology chapter of your dissertation.

Research philosophy in the ‘research onion’ [2]

Each stage of the research process is based on assumptions about the sources and the nature of knowledge. Research philosophy will reflect the author’s important assumptions and these assumptions serve as base for the research strategy. Generally, research philosophy has many branches related to a wide range of disciplines. Within the scope of business studies in particular there are four main research philosophies:

- Interpretivism (Interpretivist)

The Choice of Research Philosophy

The choice of a specific research philosophy is impacted by practical implications. There are important philosophical differences between studies that focus on facts and numbers such as an analysis of the impact of foreign direct investment on the level of GDP growth and qualitative studies such as an analysis of leadership style on employee motivation in organizations.

The choice between positivist and interpretivist research philosophies or between quantitative and qualitative research methods has traditionally represented a major point of debate. However, the latest developments in the practice of conducting studies have increased the popularity of pragmatism and realism philosophies as well.

Moreover, as it is illustrated in table below, there are popular data collection methods associated with each research philosophy.

| Popular data collection method | Mixed or multiple method designs, quantitative and qualitative | Highly structured, large samples, measurement, quantitative, but can use qualitative | Methods chosen must fit the subject matter, quantitative or qualitative | Small samples, in-depth investigations, qualitative |

Research philosophies and data collection methods [3]

My e-book, The Ultimate Guide to Writing a Dissertation in Business Studies: a step by step assistance contains discussions of theory and application of research philosophy. The e-book also explains all stages of the research process starting from the selection of the research area to writing personal reflection. Important elements of dissertations such as research philosophy , research approach , research design , methods of data collection and data analysis are explained in this e-book in simple words.

John Dudovskiy

[1] Bajpai, N. (2011) “Business Research Methods” Pearson Education India

[2] Tsung, E.W.K. (2016) “The Philosophy of Management Research” Routledge

[3] Table adapted from Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2012) “Research Methods for Business Students” 6 th edition, Pearson Education Limited

Research Philosophy & Paradigms

Positivism, Interpretivism & Pragmatism, Explained Simply

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewer: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | June 2023

Research philosophy is one of those things that students tend to either gloss over or become utterly confused by when undertaking formal academic research for the first time. And understandably so – it’s all rather fluffy and conceptual. However, understanding the philosophical underpinnings of your research is genuinely important as it directly impacts how you develop your research methodology.

In this post, we’ll explain what research philosophy is , what the main research paradigms are and how these play out in the real world, using loads of practical examples . To keep this all as digestible as possible, we are admittedly going to simplify things somewhat and we’re not going to dive into the finer details such as ontology, epistemology and axiology (we’ll save those brain benders for another post!). Nevertheless, this post should set you up with a solid foundational understanding of what research philosophy and research paradigms are, and what they mean for your project.

Overview: Research Philosophy

- What is a research philosophy or paradigm ?

- Positivism 101

- Interpretivism 101

- Pragmatism 101

- Choosing your research philosophy

What is a research philosophy or paradigm?

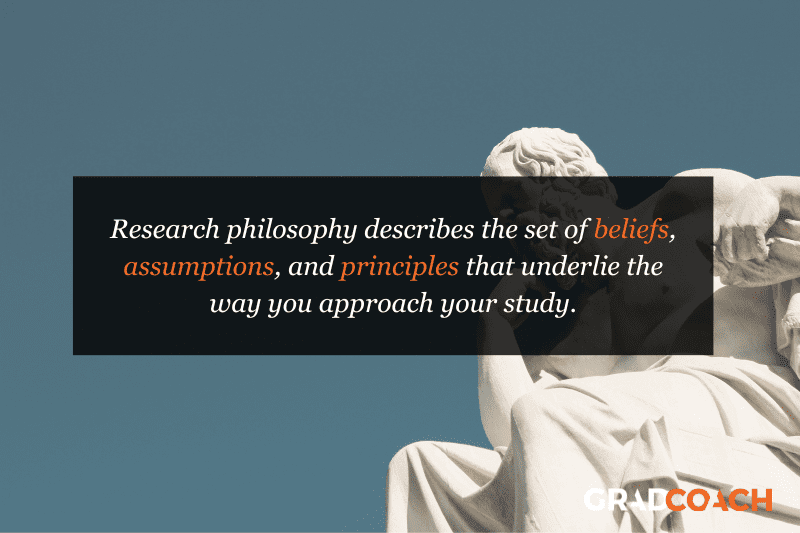

Research philosophy and research paradigm are terms that tend to be used pretty loosely, even interchangeably. Broadly speaking, they both refer to the set of beliefs, assumptions, and principles that underlie the way you approach your study (whether that’s a dissertation, thesis or any other sort of academic research project).

For example, one philosophical assumption could be that there is an external reality that exists independent of our perceptions (i.e., an objective reality), whereas an alternative assumption could be that reality is constructed by the observer (i.e., a subjective reality). Naturally, these assumptions have quite an impact on how you approach your study (more on this later…).

The research philosophy and research paradigm also encapsulate the nature of the knowledge that you seek to obtain by undertaking your study. In other words, your philosophy reflects what sort of knowledge and insight you believe you can realistically gain by undertaking your research project. For example, you might expect to find a concrete, absolute type of answer to your research question , or you might anticipate that things will turn out to be more nuanced and less directly calculable and measurable . Put another way, it’s about whether you expect “hard”, clean answers or softer, more opaque ones.

So, what’s the difference between research philosophy and paradigm?

Well, it depends on who you ask. Different textbooks will present slightly different definitions, with some saying that philosophy is about the researcher themselves while the paradigm is about the approach to the study . Others will use the two terms interchangeably. And others will say that the research philosophy is the top-level category and paradigms are the pre-packaged combinations of philosophical assumptions and expectations.

To keep things simple in this video, we’ll avoid getting tangled up in the terminology and rather focus on the shared focus of both these terms – that is that they both describe (or at least involve) the set of beliefs, assumptions, and principles that underlie the way you approach your study .

Importantly, your research philosophy and/or paradigm form the foundation of your study . More specifically, they will have a direct influence on your research methodology , including your research design , the data collection and analysis techniques you adopt, and of course, how you interpret your results. So, it’s important to understand the philosophy that underlies your research to ensure that the rest of your methodological decisions are well-aligned .

So, what are the options?

We’ll be straight with you – research philosophy is a rabbit hole (as with anything philosophy-related) and, as a result, there are many different approaches (or paradigms) you can take, each with its own perspective on the nature of reality and knowledge . To keep things simple though, we’ll focus on the “big three”, namely positivism , interpretivism and pragmatism . Understanding these three is a solid starting point and, in many cases, will be all you need.

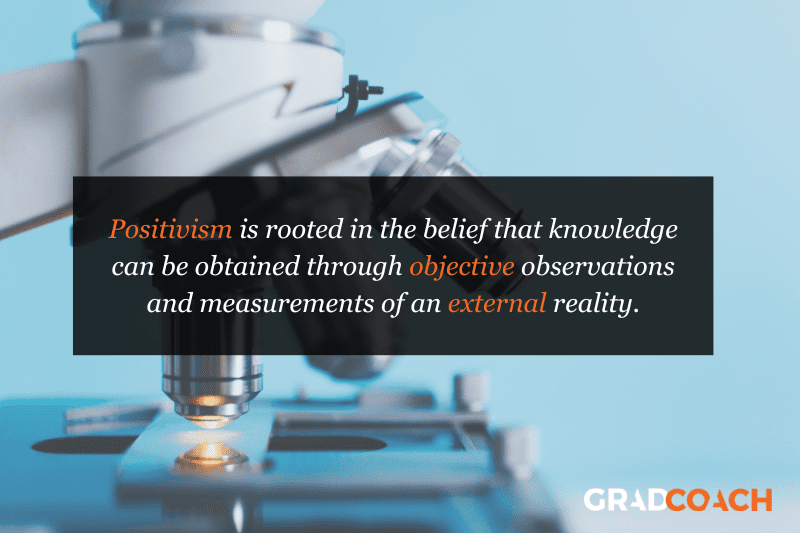

Paradigm 1: Positivism

When you think positivism, think hard sciences – physics, biology, astronomy, etc. Simply put, positivism is rooted in the belief that knowledge can be obtained through objective observations and measurements . In other words, the positivist philosophy assumes that answers can be found by carefully measuring and analysing data, particularly numerical data .

As a research paradigm, positivism typically manifests in methodologies that make use of quantitative data , and oftentimes (but not always) adopt experimental or quasi-experimental research designs. Quite often, the focus is on causal relationships – in other words, understanding which variables affect other variables, in what way and to what extent. As a result, studies with a positivist research philosophy typically aim for objectivity, generalisability and replicability of findings.

Let’s look at an example of positivism to make things a little more tangible.

Assume you wanted to investigate the relationship between a particular dietary supplement and weight loss. In this case, you could design a randomised controlled trial (RCT) where you assign participants to either a control group (who do not receive the supplement) or an intervention group (who do receive the supplement). With this design in place, you could measure each participant’s weight before and after the study and then use various quantitative analysis methods to assess whether there’s a statistically significant difference in weight loss between the two groups. By doing so, you could infer a causal relationship between the dietary supplement and weight loss, based on objective measurements and rigorous experimental design.

As you can see in this example, the underlying assumptions and beliefs revolve around the viewpoint that knowledge and insight can be obtained through carefully controlling the environment, manipulating variables and analysing the resulting numerical data . Therefore, this sort of study would adopt a positivistic research philosophy. This is quite common for studies within the hard sciences – so much so that research philosophy is often just assumed to be positivistic and there’s no discussion of it within the methodology section of a dissertation or thesis.

Paradigm 2: Interpretivism

If you can imagine a spectrum of research paradigms, interpretivism would sit more or less on the opposite side of the spectrum from positivism. Essentially, interpretivism takes the position that reality is socially constructed . In other words, that reality is subjective , and is constructed by the observer through their experience of it , rather than being independent of the observer (which, if you recall, is what positivism assumes).

The interpretivist paradigm typically underlies studies where the research aims involve attempting to understand the meanings and interpretations that people assign to their experiences. An interpretivistic philosophy also typically manifests in the adoption of a qualitative methodology , relying on data collection methods such as interviews , observations , and textual analysis . These types of studies commonly explore complex social phenomena and individual perspectives, which are naturally more subjective and nuanced.

Let’s look at an example of the interpretivist approach in action:

Assume that you’re interested in understanding the experiences of individuals suffering from chronic pain. In this case, you might conduct in-depth interviews with a group of participants and ask open-ended questions about their pain, its impact on their lives, coping strategies, and their overall experience and perceptions of living with pain. You would then transcribe those interviews and analyse the transcripts, using thematic analysis to identify recurring themes and patterns. Based on that analysis, you’d be able to better understand the experiences of these individuals, thereby satisfying your original research aim.

As you can see in this example, the underlying assumptions and beliefs revolve around the viewpoint that insight can be obtained through engaging in conversation with and exploring the subjective experiences of people (as opposed to collecting numerical data and trying to measure and calculate it). Therefore, this sort of study would adopt an interpretivistic research philosophy. Ultimately, if you’re looking to understand people’s lived experiences , you have to operate on the assumption that knowledge can be generated by exploring people’s viewpoints, as subjective as they may be.

Paradigm 3: Pragmatism

Now that we’ve looked at the two opposing ends of the research philosophy spectrum – positivism and interpretivism, you can probably see that both of the positions have their merits , and that they both function as tools for different jobs . More specifically, they lend themselves to different types of research aims, objectives and research questions . But what happens when your study doesn’t fall into a clear-cut category and involves exploring both “hard” and “soft” phenomena? Enter pragmatism…

As the name suggests, pragmatism takes a more practical and flexible approach, focusing on the usefulness and applicability of research findings , rather than an all-or-nothing, mutually exclusive philosophical position. This allows you, as the researcher, to explore research aims that cross philosophical boundaries, using different perspectives for different aspects of the study .

With a pragmatic research paradigm, both quantitative and qualitative methods can play a part, depending on the research questions and the context of the study. This often manifests in studies that adopt a mixed-method approach , utilising a combination of different data types and analysis methods. Ultimately, the pragmatist adopts a problem-solving mindset , seeking practical ways to achieve diverse research aims.

Let’s look at an example of pragmatism in action:

Imagine that you want to investigate the effectiveness of a new teaching method in improving student learning outcomes. In this case, you might adopt a mixed-methods approach, which makes use of both quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis techniques. One part of your project could involve comparing standardised test results from an intervention group (students that received the new teaching method) and a control group (students that received the traditional teaching method). Additionally, you might conduct in-person interviews with a smaller group of students from both groups, to gather qualitative data on their perceptions and preferences regarding the respective teaching methods.

As you can see in this example, the pragmatist’s approach can incorporate both quantitative and qualitative data . This allows the researcher to develop a more holistic, comprehensive understanding of the teaching method’s efficacy and practical implications , with a synthesis of both types of data . Naturally, this type of insight is incredibly valuable in this case, as it’s essential to understand not just the impact of the teaching method on test results, but also on the students themselves!

Wrapping Up: Philosophies & Paradigms

Now that we’ve unpacked the “big three” research philosophies or paradigms – positivism, interpretivism and pragmatism, hopefully, you can see that research philosophy underlies all of the methodological decisions you’ll make in your study. In many ways, it’s less a case of you choosing your research philosophy and more a case of it choosing you (or at least, being revealed to you), based on the nature of your research aims and research questions .

- Research philosophies and paradigms encapsulate the set of beliefs, assumptions, and principles that guide the way you, as the researcher, approach your study and develop your methodology.

- Positivism is rooted in the belief that reality is independent of the observer, and consequently, that knowledge can be obtained through objective observations and measurements.

- Interpretivism takes the (opposing) position that reality is subjectively constructed by the observer through their experience of it, rather than being an independent thing.

- Pragmatism attempts to find a middle ground, focusing on the usefulness and applicability of research findings, rather than an all-or-nothing, mutually exclusive philosophical position.

If you’d like to learn more about research philosophy, research paradigms and research methodology more generally, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach blog . Alternatively, if you’d like hands-on help with your research, consider our private coaching service , where we guide you through each stage of the research journey, step by step.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

21 Comments

was very useful for me, I had no idea what a philosophy is, and what type of philosophy of my study. thank you

Thanks for this explanation, is so good for me

You contributed much to my master thesis development and I wish to have again your support for PhD program through research.

the way of you explanation very good keep it up/continuous just like this

Very precise stuff. It has been of great use to me. It has greatly helped me to sharpen my PhD research project!

Very clear and very helpful explanation above. I have clearly understand the explanation.

Very clear and useful. Thanks

Thanks so much for your insightful explanations of the research philosophies that confuse me

I would like to thank Grad Coach TV or Youtube organizers and presenters. Since then, I have been able to learn a lot by finding very informative posts from them.

thank you so much for this valuable and explicit explanation,cheers

Hey, at last i have gained insight on which philosophy to use as i had little understanding on their applicability to my current research. Thanks

Tremendously useful

thank you and God bless you. This was very helpful, I had no understanding before this.

USEFULL IN DEED!

Explanations to the research paradigm has been easy to follow. Well understood and made my life easy.

Very useful content. This will make my research life easy.

The explanation is very efficacy to those who were still not understanding the research philosophy. Very clear explanations on the types of research paradigms.

The explanation is very efficacy to those who were still not understanding the research philosophy.

thank you for this informative page.

thank you:)

Very well explained.I am grateful for the understanding I gained from this scholarly writeup.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

| A research philosophy (also called a paradigm or philosophical position) is a set of basic beliefs that guide the design and execution of a research study, and different research philosophies offer different ways of understanding scientific research (Creswell, 2013; Daly, 2007; Guba & Lincoln, 1994). Research philosophies are fundamental to conducting and assessing research studies, and they are embedded within all forms of research. However, researchers are often taught the tools and strategies for conducting research studies (i.e., methods), without being taught how these methods reflect underlying assumptions about the nature of reality, truth, and knowledge. To help researchers understand the philosophical assumptions that are conveyed in their research, in this chapter, we present information regarding different research philosophies and how these inform different approaches for research and evaluation. We describe the basic differences between some of the major philosophical positions, and we suggest how research conducted from each of these philosophical positions might differ, and how each would produce different types of knowledge. Through this chapter, researchers should come to understand how their choice of research question(s) and methods are underpinned by important assumptions about the nature of reality, knowledge, and science, and how these assumptions are embedded in the language used to describe their research study. Before discussing the underlying assumptions associated with various research philosophies, it is important to distinguish between the different types of research study that one may conduct. Researchers commonly make a distinction between studies that use quantitative and qualitative data to answer their research question. Quantitative research uses numerical data to capture information about a phenomenon, experience, or event - researchers use quantitative measures to count or measure an outcome, event, phenomenon, or psychological construct as precisely as possible. For example, researchers may want to know how frequently a person experiences concerns related to their body image during the week, and whether this is associated with their level of physical activity during the week. Thus, a researcher would use various instruments or questionnaires to try and capture information about the individual's physical activity and their body-related thoughts and feelings to examine the statistical associations between these variables. Qualitative research uses textual, audio, or visual data to understand the way that people experience a phenomenon and to understand the meanings that people attribute to their experiences. Thus, researchers using qualitative approaches attempt to capture what people say and do, and to interpret patterns of meaning in the data (Denzin & Lincoln, 2012; Maykut & Morehouse, 1994). Characteristics of qualitative research include an exploratory and descriptive focus; an emergent design that can change during the course of a study as important leads are identified; a purposive sample of participants, contexts, or phenomena; qualitative data collected in natural settings (e.g., interviews, observations, photos, documents); ongoing, inductive, and deductive analysis of the data; a reflexive account of the researcher's position within the research process; and a rich description of the research outcomes (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Maykut & Morehouse, 1994). Thus, researchers aiming to understand a phenomenon or experience by focusing on people's words, actions, or documents (Maykut & Morehouse, 1994) may not be concerned with measuring or counting the number of times a person experiences body-related thoughts or feelings; rather, researchers adopting qualitative approaches may use interviews, observations, documents, and other sources of information to understand how individuals develop meanings about their bodies and what the experience of negative body-related thoughts and feelings is like for participants. It is important to note that this is a very basic distinction between studies that use quantitative and qualitative approaches to collecting and analysing data, and there are many different variations in the ways that researchers might use these types of data, particularly within the broad range of approaches and perspectives under the umbrella of qualitative research. Moreover, these different research approaches will produce different types of knowledge (Burke Johnson, 2008). For example, a researcher conducting a qualitative study might conduct interviews with participants who identify as perfectionists about their daily habits and health behaviours, and then count the number of times that participants talk about 'diet' or 'exercise' in the interview. Conversely, another researcher may not be interested in the frequency of a participant saying the word 'diet' or 'exercise', but, rather, the researcher might conduct interviews to explore how young women internalize broader societal messages about perfectionism and how these internalized standards influence their self-image and health behaviours. As this example illustrates, even under the broad umbrella of 'qualitative research', there is a great deal of variation in the approaches that researchers may take in designing their study and in collecting and analysing data. These different research approaches are underpinned by different research philosophies and will produce different types of information and knowledge about the phenomena of interest. An important point about research philosophies is that language matters - the language that a researcher uses in describing a study conveys important information about the philosophical assumptions that underpin their study and guide their research approach. For example, the way a researcher uses the terms 'validity', 'reliability', and 'generalizability' conveys their philosophical position. Furthermore, it is the researcher's responsibility to understand what they are communicating when they use particular words to describe their research methods and findings: 'It is important that those engaged in research realize that the language they choose represents and communicates a paradigm and worldview ... researchers are responsible for understanding the implications of language being used' (Jones, Torres, & Arminio, 2014, p. 4). Regardless of whether researchers are conducting quantitative or qualitative studies, it is important for researchers to understand the philosophical assumptions that underpin their research choices and approaches. | |

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, contemporary research paradigms and philosophies.

Contemporary Research Methods in Hospitality and Tourism

ISBN : 978-1-80117-547-0 , eISBN : 978-1-80117-546-3

Publication date: 13 April 2022

Understanding the most appropriate research philosophy to underpin any piece of scholarly inquiry is crucial if one hopes to address research problems in a manner distinct from those already evidenced across extant literature. Distinct philosophical ideas and positions are often associated with specific research designs, therefore influencing the research approach adopted in any given study. Identifying an appropriate philosophical approach requires robust comprehension of how philosophical positions differ, alongside a reflective understanding of one's own perceptions and beliefs regarding what knowledge and reality “are” and how new knowledge is discovered, developed, and/or confirmed. This chapter therefore discusses different research paradigms and philosophies in order to identify core distinctions therein, highlighting the advantages and the challenges associated with different philosophical approaches to research along the way.

- Contemporary research

- Research philosophy

- Hospitality

Gannon, M.J. , Taheri, B. and Azer, J. (2022), "Contemporary Research Paradigms and Philosophies", Okumus, F. , Rasoolimanesh, S.M. and Jahani, S. (Ed.) Contemporary Research Methods in Hospitality and Tourism , Emerald Publishing Limited, Leeds, pp. 5-19. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80117-546-320221002

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2022 Martin J Gannon, Babak Taheri and Jaylan Azer. Published under exclusive licence by Emerald Publishing Limited

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

University Libraries

Research methods for social sciences, research philosophy.

- Literature Review

- Research Design

- Data Collection

- Data Analysis and Reporting

- Beyond the Traditional Methods

- Research Ethics

When conducting research, there are different philosophies, with their own assumptions and worldviews, that inform your decisions on selecting a method or design for your inquiry. Some common terms are:

- Constructivism

- Interpretivism

- Post-modernism

You may also heard the term research paradigm , which is the worldview from a specific philosophy that a researcher follows. For more information on different research philosophies and paradigms, see the suggested materials below.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: May 21, 2024 1:27 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.unt.edu/rmss

Additional Links

UNT: Apply now UNT: Schedule a tour UNT: Get more info about the University of North Texas

UNT: Disclaimer | UNT: AA/EOE/ADA | UNT: Privacy | UNT: Electronic Accessibility | UNT: Required Links | UNT: UNT Home

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

The Four Types of Research Paradigms: A Comprehensive Guide

5-minute read

- 22nd January 2023

In this guide, you’ll learn all about the four research paradigms and how to choose the right one for your research.

Introduction to Research Paradigms

A paradigm is a system of beliefs, ideas, values, or habits that form the basis for a way of thinking about the world. Therefore, a research paradigm is an approach, model, or framework from which to conduct research. The research paradigm helps you to form a research philosophy, which in turn informs your research methodology.

Your research methodology is essentially the “how” of your research – how you design your study to not only accomplish your research’s aims and objectives but also to ensure your results are reliable and valid. Choosing the correct research paradigm is crucial because it provides a logical structure for conducting your research and improves the quality of your work, assuming it’s followed correctly.

Three Pillars: Ontology, Epistemology, and Methodology

Before we jump into the four types of research paradigms, we need to consider the three pillars of a research paradigm.

Ontology addresses the question, “What is reality?” It’s the study of being. This pillar is about finding out what you seek to research. What do you aim to examine?

Epistemology is the study of knowledge. It asks, “How is knowledge gathered and from what sources?”

Methodology involves the system in which you choose to investigate, measure, and analyze your research’s aims and objectives. It answers the “how” questions.

Let’s now take a look at the different research paradigms.

1. Positivist Research Paradigm

The positivist research paradigm assumes that there is one objective reality, and people can know this reality and accurately describe and explain it. Positivists rely on their observations through their senses to gain knowledge of their surroundings.

In this singular objective reality, researchers can compare their claims and ascertain the truth. This means researchers are limited to data collection and interpretations from an objective viewpoint. As a result, positivists usually use quantitative methodologies in their research (e.g., statistics, social surveys, and structured questionnaires).

This research paradigm is mostly used in natural sciences, physical sciences, or whenever large sample sizes are being used.

2. Interpretivist Research Paradigm

Interpretivists believe that different people in society experience and understand reality in different ways – while there may be only “one” reality, everyone interprets it according to their own view. They also believe that all research is influenced and shaped by researchers’ worldviews and theories.

As a result, interpretivists use qualitative methods and techniques to conduct their research. This includes interviews, focus groups, observations of a phenomenon, or collecting documentation on a phenomenon (e.g., newspaper articles, reports, or information from websites).

3. Critical Theory Research Paradigm

The critical theory paradigm asserts that social science can never be 100% objective or value-free. This paradigm is focused on enacting social change through scientific investigation. Critical theorists question knowledge and procedures and acknowledge how power is used (or abused) in the phenomena or systems they’re investigating.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Researchers using this paradigm are more often than not aiming to create a more just, egalitarian society in which individual and collective freedoms are secure. Both quantitative and qualitative methods can be used with this paradigm.

4. Constructivist Research Paradigm

Constructivism asserts that reality is a construct of our minds ; therefore, reality is subjective. Constructivists believe that all knowledge comes from our experiences and reflections on those experiences and oppose the idea that there is a single methodology to generate knowledge.

This paradigm is mostly associated with qualitative research approaches due to its focus on experiences and subjectivity. The researcher focuses on participants’ experiences as well as their own.

Choosing the Right Research Paradigm for Your Study

Once you have a comprehensive understanding of each paradigm, you’re faced with a big question: which paradigm should you choose? The answer to this will set the course of your research and determine its success, findings, and results.

To start, you need to identify your research problem, research objectives , and hypothesis . This will help you to establish what you want to accomplish or understand from your research and the path you need to take to achieve this.

You can begin this process by asking yourself some questions:

- What is the nature of your research problem (i.e., quantitative or qualitative)?

- How can you acquire the knowledge you need and communicate it to others? For example, is this knowledge already available in other forms (e.g., documents) and do you need to gain it by gathering or observing other people’s experiences or by experiencing it personally?

- What is the nature of the reality that you want to study? Is it objective or subjective?

Depending on the problem and objective, other questions may arise during this process that lead you to a suitable paradigm. Ultimately, you must be able to state, explain, and justify the research paradigm you select for your research and be prepared to include this in your dissertation’s methodology and design section.

Using Two Paradigms

If the nature of your research problem and objectives involves both quantitative and qualitative aspects, then you might consider using two paradigms or a mixed methods approach . In this, one paradigm is used to frame the qualitative aspects of the study and another for the quantitative aspects. This is acceptable, although you will be tasked with explaining your rationale for using both of these paradigms in your research.

Choosing the right research paradigm for your research can seem like an insurmountable task. It requires you to:

● Have a comprehensive understanding of the paradigms,

● Identify your research problem, objectives, and hypothesis, and

● Be able to state, explain, and justify the paradigm you select in your methodology and design section.

Although conducting your research and putting your dissertation together is no easy task, proofreading it can be! Our experts are here to make your writing shine. Your first 500 words are free !

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

Free email newsletter template (2024).

Promoting a brand means sharing valuable insights to connect more deeply with your audience, and...

6-minute read

How to Write a Nonprofit Grant Proposal

If you’re seeking funding to support your charitable endeavors as a nonprofit organization, you’ll need...

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Breadcrumbs Section. Click here to navigate to respective pages.

Research philosophies

DOI link for Research philosophies

Click here to navigate to parent product.

A research philosophy is a set of basic beliefs that guide the design and execution of a research study, and different research philosophies offer different ways of understanding scientific research. Qualitative research uses textual, audio, or visual data to understand the way that people experience a phenomenon and to understand the meanings that people attribute to their experiences. Research philosophies represent ‘a worldview that defines, for its holder, the nature of the “world,” the individual’s place in it, and the range of possible relationships to that world and its parts’. Post-positivism is the predominant philosophical position in which most researchers in sport and exercise psychology situate their studies. Research conducted from a constructivist philosophical position focuses on understanding the meanings people create for themselves and attribute to their experience. The notion of a subjective and transactional epistemology underlies the concept of co-constructing knowledge or meaning within qualitative research.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Taylor & Francis Group

- Students/Researchers

- Librarians/Institutions

Connect with us

Registered in England & Wales No. 3099067 5 Howick Place | London | SW1P 1WG © 2024 Informa UK Limited

- Classification

- Physical Education

- Travel and Tourism

- BIBLIOMETRICS

- Banking System

- Real Estate

Select Page

Research Philosophy: Positivism, Interpretivism, and Pragmatism

Posted by Md. Harun Ar Rashid | Jun 28, 2023 | Research Methodology

Research philosophy refers to the set of beliefs, assumptions, and methodologies that guide the way researchers approach their investigations. It provides a framework for understanding the nature of knowledge, the role of the researcher, and the methods used to gather and interpret data. There are several research philosophies, but three of the most widely recognized and influential ones are positivism, interpretivism, and pragmatism. In this article, we will explore these three research philosophies in brief, providing a simple and accessible explanation of each.

1. Positivism:

Positivism is a research philosophy that originated in the natural sciences and gained prominence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It is based on the belief that scientific knowledge should be derived from empirical observation and objective measurement. Positivists assume that there is a single reality that exists independently of our perceptions and that this reality can be understood through systematic and rigorous scientific methods.

Key Principles:

a. Objectivity: Positivists emphasize the importance of objectivity in research. They argue that researchers should strive to eliminate bias and personal opinions from their investigations. Objectivity is achieved through careful design and execution of experiments, reliance on measurable and observable data, and the use of statistical analysis to draw conclusions.

b. Determinism: Positivism assumes that the social world operates according to universal laws that can be discovered through scientific inquiry. It suggests that human behavior is determined by external factors such as social structures, cultural norms, and economic conditions. This deterministic view implies that social phenomena can be predicted and explained using objective and generalizable laws.

c. Reductionism: Positivists often employ reductionism, which involves breaking down complex phenomena into smaller, more manageable parts. They believe that by studying the individual components of a system, they can gain a better understanding of the whole. Reductionism allows researchers to isolate specific variables and test their effects in controlled conditions.

d. Quantitative Methods: Positivism favors quantitative research methods, such as surveys, experiments, and statistical analysis. These methods provide numerical data that can be analyzed statistically to identify patterns, correlations, and cause-and-effect relationships. Positivists value the reliability and replicability of quantitative research, as it allows for precise measurement and comparison.

Critiques and Limitations:

Critics argue that positivism has several limitations. They claim that the positivist approach overlooks the subjective experiences and meanings that individuals attach to their actions. Additionally, positivism’s focus on observable and measurable phenomena may neglect important contextual factors that influence human behavior. Critics also argue that the notion of objective reality is problematic, as individuals’ perceptions and interpretations shape their understanding of the world.

2. Interpretivism:

Interpretivism, also known as constructivism or hermeneutics, emerged as a response to the limitations of positivism in the social sciences. It emphasizes the subjective nature of human experience and focuses on understanding social phenomena through the meanings and interpretations that individuals assign to them. Interpretivists believe that social reality is socially constructed and context-dependent and that it cannot be reduced to objective laws or generalizations.

a. Subjectivity: Interpretivism acknowledges that individuals have unique experiences, perspectives, and interpretations of the world. Researchers aim to understand these subjective meanings by engaging in dialogue and interaction with research participants. They seek to uncover the complex and diverse ways in which individuals create and attribute meaning to their actions and social interactions.

b. Social and Historical Context: Interpretivists emphasize the importance of understanding social phenomena within their specific social and historical contexts. They recognize that individuals’ beliefs, values, and behaviors are shaped by their cultural, historical, and institutional backgrounds. Researchers employ qualitative methods, such as interviews, observations, and textual analysis, to capture the richness and complexity of these contextual factors.

c. Reflexivity: Interpretivism promotes reflexivity, which involves acknowledging and reflecting upon the influence of the researcher’s own background, biases, and assumptions on the research process. Researchers recognize that their interpretations are inherently subjective and influenced by their own perspectives. Reflexivity helps researchers identify and address potential biases and enhances the credibility of their findings.

d. Inductive Reasoning: Interpretivists often employ inductive reasoning, which involves deriving general conclusions from specific observations. They emphasize the importance of exploring and discovering patterns and themes in qualitative data, rather than starting with preconceived theories or hypotheses. This approach allows for the emergence of new insights and theories grounded in the data.

Critics argue that interpretivism lacks objectivity and generalizability, as its focus on subjective meanings and context-specific interpretations makes it difficult to draw universal conclusions. They also claim that interpretive research can be overly reliant on the researcher’s interpretive skills, potentially introducing bias and subjectivity into the analysis. Additionally, some argue that interpretivism may prioritize understanding over explanation, limiting its ability to generate causal explanations or predict behavior.

3. Pragmatism:

Pragmatism is a research philosophy that seeks to bridge the gap between positivism and interpretivism. It emphasizes the practical consequences of knowledge and encourages researchers to adopt a flexible and problem-solving approach. Pragmatists believe that the value of knowledge lies in its usefulness and its ability to address real-world problems.

- Practicality: Pragmatism prioritizes the practical applications of knowledge. Researchers are encouraged to focus on solving real-world problems and addressing the needs of individuals and communities. Pragmatists believe that research should have practical implications and be relevant to the concerns of society.

- Pluralism: Pragmatism recognizes that different research methods and approaches can be useful in different contexts. It promotes a pluralistic view that values the integration of multiple perspectives and methods. Researchers are encouraged to select the most appropriate methods based on the research question, context, and desired outcomes.

- Mixed Methods: Pragmatists often employ mixed methods, combining both qualitative and quantitative approaches, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of research phenomena. They believe that this integration of methods can provide a more holistic and nuanced perspective, drawing on the strengths of each approach.

- Pragmatic Truth: Pragmatism defines truth in terms of its practical consequences. Rather than seeking absolute or universal truth, pragmatists focus on the usefulness and effectiveness of knowledge in solving problems and improving outcomes. Truth is seen as a dynamic and evolving concept that is subject to revision based on new evidence and experiences.

Critics argue that pragmatism can be seen as a compromise that sacrifices depth and rigor for practicality. They claim that the integration of different methods can be challenging and may lead to a superficial treatment of complex research phenomena. Additionally, some argue that the emphasis on practicality and problem-solving may overshadow the critical examination of underlying power structures and social inequalities.

Choosing Your Research Philosophy:

Selecting a research philosophy is a crucial step in the research process, as it provides a framework for understanding the nature of knowledge, the role of the researcher, and the methods used to gather and interpret data. The choice of research philosophy depends on several factors, including the research question, the nature of the study, and the researcher’s epistemological and ontological beliefs. In this section, we will discuss important considerations when choosing your research philosophy.

A. Research Question: The research question serves as the starting point for selecting a research philosophy. Consider the nature of your research question and the type of knowledge you seek to generate. Is your research question focused on understanding the subjective experiences and meanings of individuals? Or does it aim to identify general patterns and causal relationships? The research question will help guide your choice between interpretivism and positivism.

- If your research question focuses on exploring subjective meanings, social interactions, and cultural context, interpretivism may be a suitable choice. Interpretive research allows for in-depth exploration of individuals’ perspectives and the contextual factors that shape their experiences.

- On the other hand, if your research question aims to establish general laws, predict behavior, or test cause-and-effect relationships, positivism may be more appropriate. Positivist research emphasizes objectivity, quantifiable data, and the identification of universal patterns.

B. Nature of the Study: Consider the nature of your study, including its scope, context, and practical implications. This consideration can guide your choice of research philosophy.

- If your study is exploratory, seeks to generate new theories or concepts, or focuses on understanding complex social phenomena, interpretivism may be suitable. Interpretive research methods, such as interviews, observations, and qualitative analysis, allow for a deep exploration of individual experiences and the context in which they occur.

- If your study is more applied, aims to solve practical problems, or requires numerical data for statistical analysis, pragmatism may be a viable option. Pragmatic research emphasizes practicality, mixed methods, and the integration of different perspectives and approaches to address real-world issues.

C. Epistemological and Ontological Beliefs: Epistemology and ontology refer to your beliefs about the nature of knowledge and reality, respectively. These philosophical perspectives influence your choice of research philosophy.

- Epistemological Beliefs: Consider whether you believe knowledge is objective and can be discovered through empirical observation (positivism) or whether it is subjective and constructed through interpretation and social interactions (interpretivism). If you value subjective experiences, interpretations, and context-dependency of knowledge, interpretivism may align with your epistemological beliefs.

- Ontological Beliefs: Reflect on your beliefs about the nature of reality and whether you think it is deterministic (positivism) or socially constructed and context-dependent (interpretivism). If you believe that reality is objective, exists independently of human perception, and can be reduced to observable and measurable phenomena, positivism may align with your ontological beliefs. If you believe that reality is socially constructed and shaped by human experiences, interpretations, and cultural context, interpretivism may resonate with your ontological beliefs.

D. Practical Considerations: Practical considerations, such as available resources, time constraints, and the feasibility of data collection and analysis methods, should also be taken into account when selecting a research philosophy.

- Resource Availability: Consider the resources available to you, including funding, equipment, and access to research participants. Certain research methods and approaches may require more resources than others. For example, positivist research often requires larger sample sizes and sophisticated data collection tools, while interpretive research may rely on in-depth interviews or participant observation.

- Time Constraints: Consider the time available for conducting your research. Some research philosophies, such as positivism, often require structured data collection methods and statistical analysis, which can be time-consuming. Conversely, interpretive research may involve prolonged engagement with research participants and iterative data analysis processes.

- Feasibility of Methods: Evaluate the feasibility of different research methods within the constraints of your study. Consider the compatibility of your research question with various data collection methods (e.g., surveys, interviews, observations) and analysis techniques (e.g., statistical analysis, content analysis). Choose a research philosophy that allows you to collect and analyze data effectively within the limitations of your study.

In summary, choosing a research philosophy involves considering the research question, the nature of the study, your epistemological and ontological beliefs, and practical considerations. By carefully evaluating these factors, you can select a research philosophy that aligns with your research goals, enhances the validity of your findings, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in your field.

Finally, we can say that positivism, interpretivism, and pragmatism represent distinct research philosophies, each with its own set of assumptions, principles, and methodologies. Positivism emphasizes objectivity, determinism, and quantitative methods, seeking to discover general laws that govern the social world. Interpretivism focuses on subjective meanings, social and historical context, and qualitative methods, aiming to understand the complexities of human experiences and social interactions. Pragmatism emphasizes practicality, pluralism, and mixed methods, seeking to address real-world problems and generate useful knowledge. While these research philosophies have their respective strengths and limitations, researchers often adopt a philosophy based on the nature of their research questions, the context of the study, and their own epistemological and ontological beliefs. By understanding these philosophies, researchers can make informed choices about their research approaches and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in their respective fields.

What is research philosophy?

Research philosophy refers to the set of beliefs, assumptions, and methodologies that guide the way researchers approach their investigations. It provides a framework for understanding the nature of knowledge, the role of the researcher, and the methods used to gather and interpret data.

What is positivism?

Positivism is a research philosophy that originated in the natural sciences and emphasizes the importance of empirical observation and objective measurement. Positivists believe in a single, objective reality that exists independently of our perceptions and can be understood through systematic and rigorous scientific methods.

What is interpretivism?

Interpretivism, also known as constructivism or hermeneutics, is a research philosophy that emphasizes the subjective nature of human experience and focuses on understanding social phenomena through the meanings and interpretations that individuals assign to them. It recognizes that social reality is socially constructed and context-dependent.

What is pragmatism?

What is the significance of choosing a research philosophy?

Choosing a research philosophy is significant because it provides a framework for understanding the nature of knowledge, the role of the researcher, and the methods used to gather and interpret data. It guides the entire research process, from formulating research questions to selecting appropriate methodologies.

How do I choose the right research philosophy?

Choosing the right research philosophy involves considering several factors:

- Research question: Consider the nature of your research question and the type of knowledge you seek to generate. Is it focused on subjective experiences or general patterns? This will guide your choice between interpretivism and positivism.

- Nature of the study: Evaluate the scope, context, and practical implications of your study. Does it require in-depth exploration or solving real-world problems? This can guide you towards interpretivism or pragmatism, respectively.

- Epistemological and ontological beliefs : Reflect on your beliefs about the nature of knowledge and reality. Do you value subjective interpretations or objective observations? This will align with interpretivism or positivism, respectively.

- Practical considerations: Consider the available resources, time constraints, and feasibility of methods. Choose a philosophy that suits the resources at your disposal and aligns with the practical requirements of your study.

Can I mix research philosophies?

Yes, it is possible to mix research philosophies, and this approach is known as methodological pluralism. Pragmatism, in particular, promotes the integration of multiple perspectives and methods. Researchers may combine qualitative and quantitative approaches or draw from different philosophies depending on the research question and objectives.

What are the advantages of each research philosophy?

- Positivism: Positivism provides objectivity and allows for generalizable findings. It emphasizes empirical evidence and can establish causal relationships.

- Interpretivism: Interpretivism enables a deep understanding of subjective experiences and social contexts. It allows researchers to explore complex social phenomena and capture rich qualitative data.

- Pragmatism: Pragmatism focuses on practical applications and problem-solving. It allows researchers to integrate various methods, gaining a comprehensive understanding of research phenomena.

Are there any limitations to each research philosophy?

- Positivism: Positivism may overlook subjective experiences and contextual factors. It can be limited in its ability to capture complex social phenomena and may neglect the influence of social and cultural factors.

- Interpretivism: Interpretivism lacks objectivity and generalizability. The subjective interpretation of data can introduce researcher bias. It may also prioritize understanding over explanation or prediction.

- Pragmatism: Pragmatism may sacrifice depth and rigor for practicality. Integrating different methods can be challenging, and the focus on problem-solving may overshadow the critical examination of underlying social issues.

Can I change my research philosophy during a study?

While it is possible to change research philosophies during a study, it should be done cautiously and with valid reasons. Changing the research philosophy may affect the research design, data collection, and interpretation of findings. Consult with experienced researchers or your academic advisor before making such a change.

References:

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Sage Publications.

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 105-117). Sage Publications.

- Morgan, D. L. (2007). Paradigms lost and pragmatism regained: Methodological implications of combining qualitative and quantitative methods. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 48-76.

- Ponterotto, J. G. (2005). Qualitative research in counseling psychology: A primer on research paradigms and philosophy of science. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 126-136.

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method, and research. Sage Publications.

- Smith, M. J., & Heshusius, L. (2005). Closing the gap: From evidence to action. Heinemann.

- Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (Eds.). (2003). Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Sage Publications.

- Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2009). Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Sage Publications.

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Sage Publications.

Former Student at Rajshahi University

About The Author

Md. Harun Ar Rashid

Related posts.

How Does the Analysis Differ from the Interpretation in a Research Context?

December 4, 2023

Inferential Statistics | Different Types of Inferential Statistics

October 26, 2023

Formulating a Research Problem | Importance, Sources, Considerations in Selecting, and Steps in Formulating a Research Problem | Formulation of Research Objectives

September 26, 2022

The Art of Descriptive Writing: Purpose, Techniques, Types, and Tips

February 1, 2024

Follow us on Facebook

Library & Information Management Community

Recent Posts

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |

Pin It on Pinterest

- LiveJournal

Spirituality

The mental health of the "spiritual but not religious", surprisingly, people who identify as spiritual tend to have worse mental health..

Posted August 27, 2024 | Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

- Many people today report having a spiritual life while disavowing any particular religious practice.

- Research shows that being spiritual but not religious significantly predicts mental distress.

- Modes of evaluation that commend a spiritual life without due reflection should be regarded with caution.

There is a long tradition of wondering about the mental health implications of religious practice. The psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Jung famously claimed to have seen almost no practicing Catholics in decades of clinical practice. Others have failed to replicate this result, but the idea that religious practice has some meaningful impact on mental health persists.

For Jung, speaking in 1939, the world could be divided into two categories: those who practiced a religion (which for Europeans of Jung's era primarily included Catholicism, Protestantism, and Judaism) and those who did not. Any serious contemporary consideration of this question, however, would need to introduce a third category. Many people today reject "organized religion," but do not quite identify as secular either. They report having a spiritual life while disavowing any particular religious practice. They are, in a phrase, " spiritual but not religious ."

This fact introduces a new question for psychology: What are the mental health benefits of this spiritual attitude? One might reasonably suppose that they are positive. After all, many people who take this attitude engage in practices that are widely held to be beneficial to mental health, such as meditation , even if they do not accept the background theology of Buddhism or other major religions that encourage meditative practices. This spiritual orientation is also a part of 12-step programs that encourage individuals to find their own "higher power," outside the bounds of traditional religious belief. So, one might think that this kind of spiritual orientation to the world is associated with positive mental health.

Mixed Research Results

The empirical literature on this question, however, is decidedly more mixed. Consider an important 2013 study in the British Journal of Psychiatry . The authors consider data from approximately 7,400 individuals in England. Of these, most identify as either religious or as non-religious and non-spiritual, but about a fifth (19 percent) identify as spiritual but not religious. The prevalence of mental disorders in the first two groups (the religious and the non-religious non-spiritual) is roughly the same, but the spiritual but not religious are different: Among other things, they are significantly more likely to have phobias, anxiety , and neurotic disorders generally. In short, being spiritual but not religious is a significant predictor of mental distress, compared to the general population.

This correlation between spirituality without religiosity ought to give us pause, in part because it is confirmed by subsequent studies. For example, one more recent study (Vittengl, 2018) finds that people who are more spiritual than they are religious are at greater risk for the development of depressive disorders. As I said, all this is very puzzling. What explains these somewhat dispiriting findings? And what lessons should we draw from it?

Three Caveats

To begin with, we should note three caveats or complications.

First, as the authors emphasize, these findings say nothing about cause and effect. It could be that spiritual practices outside of traditional religion are a cause of mental distress. Or it equally well could be that people in mental distress seek out spiritual but non-religious practices. Or it could be that these two phenomena—being spiritual but not religious and experiencing mental distress—are common effects of some shared cause.

Second, many people do not seek their spiritual orientation, in the first place, because of its mental health benefits. People who are drawn to spirituality while rejecting traditional religious frameworks are in the first place pursuing their own spiritual values, rather than seeking mental health. So these correlations should not, on their own, lead anyone to doubt their own spiritual convictions.

Third, as all of the authors discussed above acknowledge, these correlations remain very poorly understood. This is partly because we are stuck in a dichotomous way of thinking about spirituality—on which people are religious or not religious—that the introduction of a third category remains something of a novelty. Furthermore, this third category remains poorly understood, in part because "spirituality" itself admits so many different understandings.

With those qualifications in place, however, I think these correlations ought to be better known and recognized by practicing clinicians. Many clinicians will see the development of a spiritual life in a client, outside the bounds of traditional religion, as a sign of psychological growth. And, indeed, it is often that. But it is, at the same time, something of a risk factor for many mental health disorders, and so is not exactly an unalloyed good.

Here as elsewhere, there are few unambiguous goods in therapy , and what may be good for one person may be concerning in another. Modes of evaluation that commend a spiritual life, without due reflection on the role and structures involved in that life, should be regarded with some caution. The empirical evidence, such as it is, suggests that being "spiritual but not religious" is a more ambivalent state than it is usually taken to be.

King M, Marston L, McManus S, Brugha T, Meltzer H, Bebbington P (2013) Religion, spirituality and mental health: results from a national study of English households. British Journal of Psychiatry . 202(1):68–73.

Vittengl JR (2018) A lonely search?: Risk for depression when spirituality exceeds religiosity. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 206:386–389.

John T. Maier, Ph.D., MSW , is a psychotherapist in private practice in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Professor of Philosophy

- Madison, Wisconsin

- COLLEGE OF LETTERS AND SCIENCE/PHILOSOPHY-GEN

- Faculty-Full Time

- Opening at: Aug 28 2024 at 16:15 CDT

Job Summary:

The highly ranked Department of Philosophy is seeking excellent junior candidates for multiple tenure/tenure-track faculty positions. The selected candidate will mount a vigorous research program while making significant contributions to the department's teaching mission. The area of research is open and specialization is open. The successful candidate will advance the educational mission of the College of Letters & Science, that values, prioritizes, and actualizes evidence-based and student-centered teaching and undergraduate student mentoring. They will contribute to an inclusive, fair, and equitable environment that fosters engagement and a sense of belonging for faculty, staff, students and members of the broader community.

Responsibilities:

Successful applicants will teach graduate and undergraduate classes, mentor students, conduct scholarly research, and provide service to the department, college, university, and academic community nationally or internationally. The general teaching load is 4 courses per year, 2 in one semester and 2 in the other. The successful candidate, as a member of the College of L&S, will proactively contribute to, support, and advance the college's commitment to equity among all aspects of their teaching, mentoring, research, and service.

Institutional Statement on Diversity:

Diversity is a source of strength, creativity, and innovation for UW-Madison. We value the contributions of each person and respect the profound ways their identity, culture, background, experience, status, abilities, and opinion enrich the university community. We commit ourselves to the pursuit of excellence in teaching, research, outreach, and diversity as inextricably linked goals. The University of Wisconsin-Madison fulfills its public mission by creating a welcoming and inclusive community for people from every background - people who as students, faculty, and staff serve Wisconsin and the world. For more information on diversity and inclusion on campus, please visit: Diversity and Inclusion

Required PhD in Philosophy or similar is required by the start of the appointment.

Qualifications:

Candidates should demonstrate evidence of creativity and excellence in teaching and scholarly research. In addition, the successful candidate will demonstrate experience with fostering or the ability to foster an inclusive and equity-centered teaching, learning, departmental, and research environment where all can thrive.

Full Time: 100% It is anticipated this position requires work be performed in-person, onsite, at a designated campus work location.

Appointment Type, Duration:

Ongoing/Renewable

Anticipated Begin Date:

AUGUST 18, 2025

Negotiable ACADEMIC (9 months)

Additional Information:

The Department of Philosophy at UW-Madison is highly rated and has department strengths in traditional areas of Philosophy as well as a variety of subdisciplines, including Philosophy of Science, Philosophy of Education, and AI Ethics. Our department is multidisciplinary and has a highly collaborative environment. Madison is the state's capitol city and is well known for offering a small town feel in a medium sized city. It is a great place to raise a family and offers an ideal combination of natural beauty, stimulating cultural events, outstanding schools and outdoor recreation. The College of Letters & Science is committed to creating an inclusive environment in which all of us - students, staff, and faculty - can thrive. Ours is a community in which we all are welcome. Most importantly, we strive to build a community in which all of us feel a great sense of belonging. There is no excellence without diversity in all its forms; diverse teams are more creative and successful than homogeneous ones. We are better when we are diverse and when we acknowledge, celebrate and honor our diversity. In acknowledging and honoring our diversity, we also assume a responsibility to support and stand up for each other.

How to Apply:

Applications must come through UW Jobs website ( http://jobs.wisc.edu ), under job number 304309. Applications submitted outside of this system will not be considered. To begin the application process please click on the 'Apply Now' button. You will be asked to create a profile. For full consideration, all materials must be received no later than 11:59 pm on October 15, 2024. Applications will be accepted until the position is filled. Please note that applicants will be evaluated based upon submitted application materials and therefore should speak to and include evidence of their qualifications. Application materials must clearly demonstrate the applicant's dedication to excellence in student-centered teaching and mentoring. Additionally, materials should showcase the applicant's ability to purposefully plan their teaching practices, evidenced through goals, action plans, reflection, and related documentation. This portion of application materials must be created by the applicant and may include supporting letters. It cannot be only in the form of letters and testimony by others. Please upload the following 4 documents: 1) a cover letter 2) a Curriculum Vitae 3) one or two articles (published or unpublished; if two articles, please upload both in same document) 4) evidence of teaching and mentoring excellence

In addition, you will be asked to provide the names and contact information for three references. References will be contacted upon application submission. If a candidate has more than three references, please send the name and email contact for additional references to [email protected] Candidates should be available for interviews on Zoom in November or December. Please reference PVL304309 in all correspondence. Employment will require an institutional reference check regarding any misconduct. To be considered, applicants must upload a signed 'Authorization to Release Information' form as part of the application. The authorization form and a definition of 'misconduct' can be found here: https://hr.wisc.edu/institutional-reference-check/

Wendy Crabb [email protected] 608-263-5335 Relay Access (WTRS): 7-1-1. See RELAY_SERVICE for further information.

Official Title:

Assistant Professor(FA040)

Department(s):

A48-COL OF LETTERS & SCIENCE/PHILOSOPHY/PHILOSOPHY

Employment Class:

Job number:, the university of wisconsin-madison is an equal opportunity and affirmative action employer..

You will be redirected to the application to launch your career momentarily. Thank you!

Frequently Asked Questions

Applicant Tutorial

Disability Accommodations

Pay Transparency Policy Statement

Refer a Friend

You've sent this job to a friend!

Website feedback, questions or accessibility issues: [email protected] .

Learn more about accessibility at UW–Madison .

© 2016–2024 Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System • Privacy Statement

Before You Go..

Would you like to sign-up for job alerts.

Thank you for subscribing to UW–Madison job alerts!

Research Philosophy, Methodological Implications, and Research Design

- Open Access

- First Online: 20 October 2023

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Jonas Bergmann 6

Part of the book series: Studien zur Migrations- und Integrationspolitik ((SZMI))

5773 Accesses

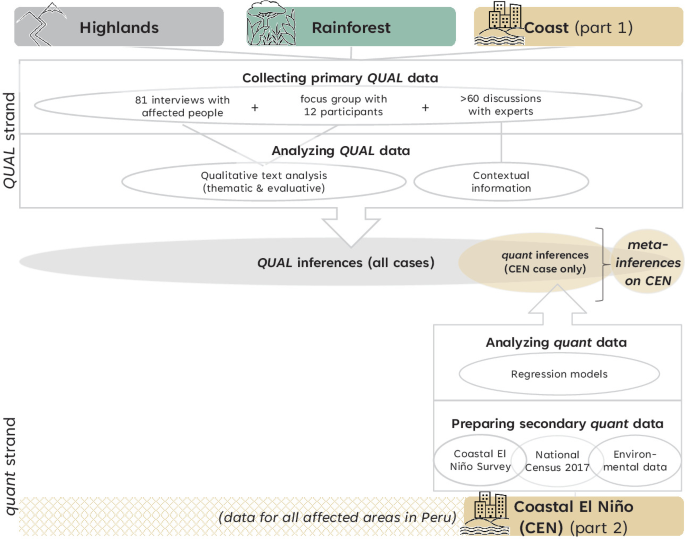

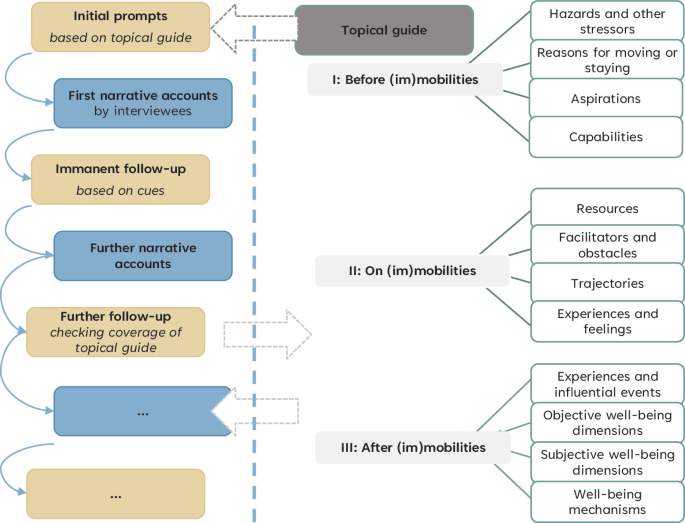

In this chapter, I explain the choices for the layers of the research approach applied in this book. Chiefly, I used a critical realist research stance and analyzed both qualitative case studies as well as survey data in a mixed methods approach. For the central qualitative research, I collected data through 81 problem-centered interviews, one focus group with 12 affected people, and discussions with over 60 experts. I analyzed the data through Qualitative Text Analysis to examine effects, mechanisms, social system dynamics, and structures. For the parallel quantitative study on the Coastal El Niño, I assessed extensive survey data through regression models. To evaluate differential displacement risk, I used a dataset collected by Peru’s National Institute of Statistics and Informatics directly after the disaster with close to 190,000 affected adults spread across all of Peru. Additionally, to identify the effects of displacement on well-being, I applied a customized, merged dataset of that survey and the National Census collected later in the same year. The chapter discusses the used data as well as the strengths and limitations of all chosen methods.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

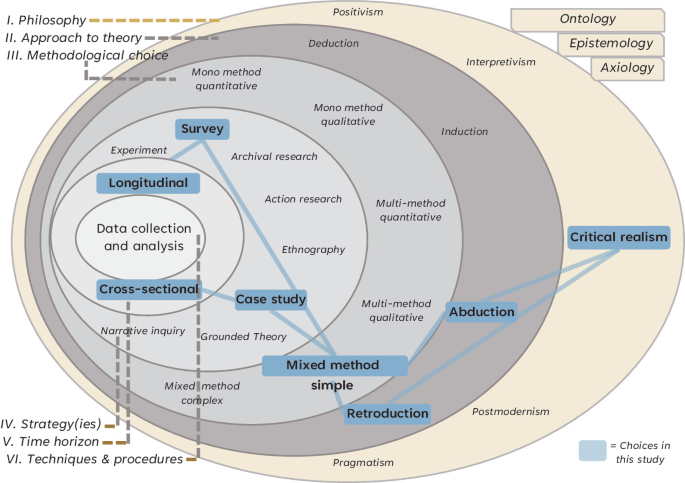

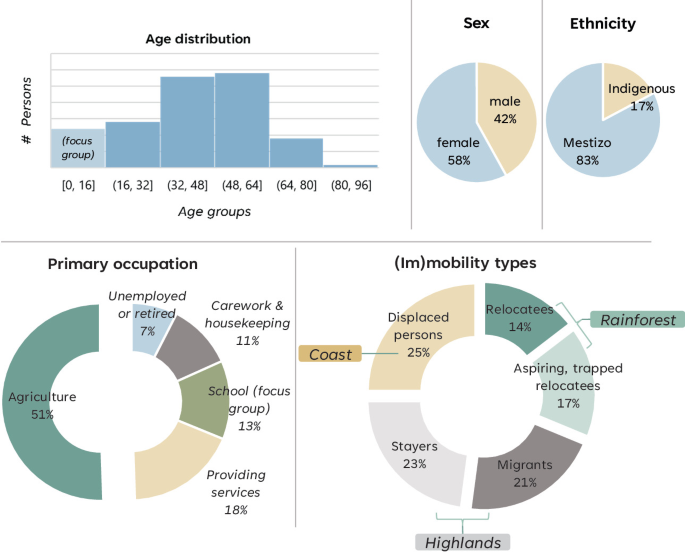

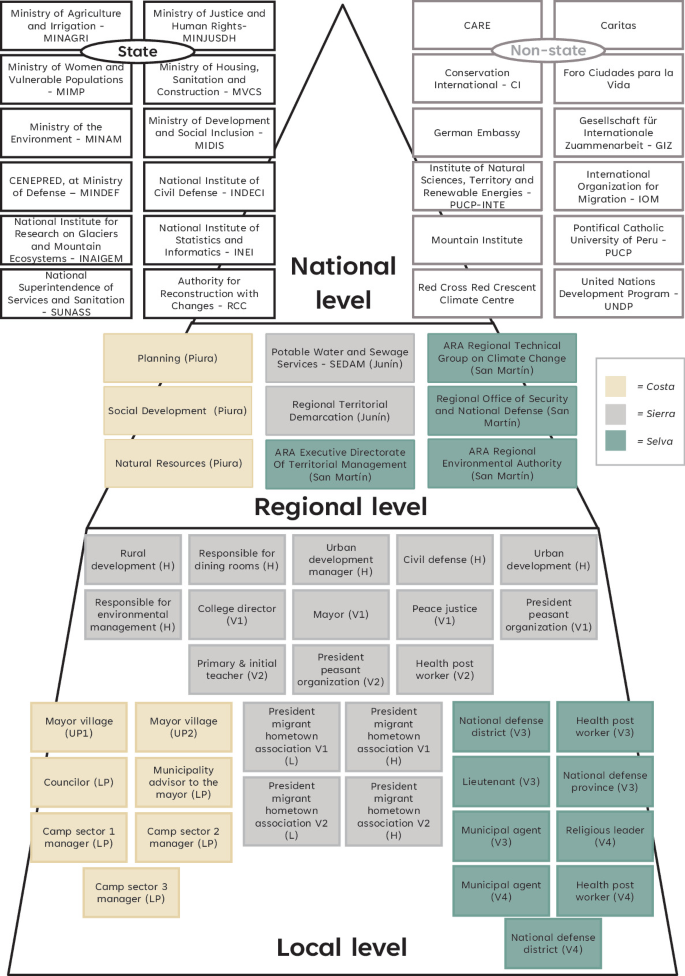

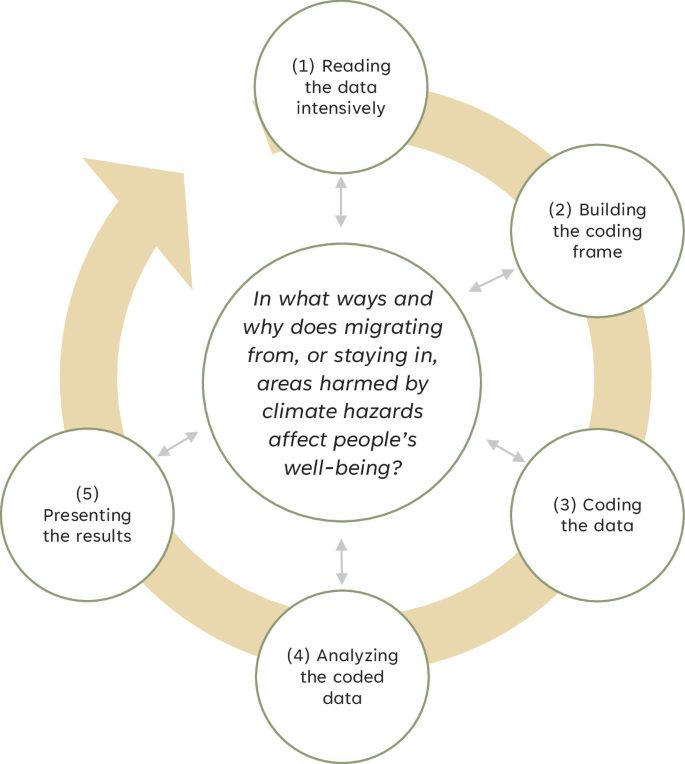

In this chapter, I explain the choices for the four different layers of the research approach applied in this dissertation, which are illustrated in Figure 3.1 (Saunders et al. 2011). I used a critical realist research stance, applied retroduction and abduction as modes of reasoning, and analyzed both qualitative case studies and survey data in a mixed methods approach.