- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Political Science Research

iResearchNet

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research

For decades, there has been a raging debate among scholars regarding the differences between and advantages of qualitative and quantitative methods. In fact, this has probably been one of the largest and longest methodological debates in all of social science research. Perhaps it can be briefly summarized by the following two famous and opposing quotations: Donald Campbell says, “All research ultimately has a qualitative grounding”; and Fred Kerlinger says, “There’s no such thing as qualitative data. Everything is either 1 or 0” (in Miles & Huberman, 1994, p. 40). Although it is not necessarily critical to determine which—if either—of these approaches can be described as the better one, it is imperative to have a thorough understanding of these methods in order to be able to conduct sound political science research. After all, for a study to be of value to scholars and other individuals interested in the topic, it is necessary for one to choose the correct research approach, ask suitable questions, use appropriate research methods and statistical analyses, correctly deduce or induce inferences, and have suitable general goals driving the research.

The questions under consideration and the answers obtained by any particular study will depend on whether the study uses quantitative or qualitative approaches. The purpose of this article is to differentiate between these two types of research. First, the literature available on this topic is briefly summarized, focusing specifically on how qualitative and quantitative research is defined, as well as the different assumptions on which these types of research are based. Next, a summary of the similarities and differences in each stage of the research process is provided. Then, the different methods that these two types of approaches use are discussed. Next, since this is a book examining political science in the 21st century, current and future research directions are examined. In particular, the use of what are called mixed methods approaches is discussed. The article ends with a brief summary and conclusion of the information that has been presented. Finally, suggested books and articles for further reading are provided, including some material for individuals interested in conducting advanced statistical studies, which are beyond the scope of this article.

Definition of Quantitative Research

Assumptions of quantitative research, definition of qualitative research, assumptions of qualitative research, the research question, research design, data collection, data analysis, reporting of results, limitations of quantitative methods, limitations of qualitative methods, future directions, quantitative and qualitative research.

The following section introduces the definitions and assumptions of quantitative and qualitative research. First, however, it is worth briefly discussing two types of political analysis in order to understand the origins of quantitative and qualitative methods. Political scientists distinguish between empirical analysis—obtaining and dealing with knowledge and information—and normative analysis— determining how to use that knowledge. Normative analysis relies on the development of subjective goals and values to apply what has been learned to reality. Empirical analysis, however, focuses on using common terms to explain and describe political reality and can be either quantitative or qualitative in nature. If something is empirical, it is verifiable through observations or experiments. Empirical analysis is the focus of this article.

As a first step, it is necessary to define these two methods of research and examine their goals. Quantitative research can be defined as a process of inquiry examining an identified problem that is based on testing a theory measured by numbers and analyzed with statistical techniques. Thus, quantitative research involves the analysis of numerical data. A more technical definition is provided by Brady and Collier (2004), who define mainstream quantitative methods as “an approach to methodology strongly oriented toward regression analysis, econometric refinements on regression, and the search for statistical alternatives to regression models in contexts where specific regression assumptions are not met” (p. 294). The econometric refinements and statistical alternatives referred to by the authors are beyond the scope of this article but include logit and probit models, time-series analysis, and a variety of techniques to circumvent problems that can occur in regression analysis, such as heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation. Essentially, quantitative methods have played a major role in improving on commonly used research tools within the structure of regression models that are frequently used in the field of political science.

The goal of quantitative research is to examine particular instances or aspects of phenomena to determine if predictive generalizations of a theory hold true or to test causal hypotheses. As a result, there are several key assumptions underlying quantitative research methods, which are briefly outlined here. These include the following:

- Reality can be studied objectively.

- Research must remain independent of the researcher through the use of experiments, questionnaires, machines, or inventories.

- Research is value free, and the researcher does not become a part of or interfere with the research.

- Theories and hypotheses are tested in a cause effect order with research based primarily on deductive forms of logic identified a priori by the researcher.

- The purpose of research is to develop generalizations that contribute to theory and allow the researcher to predict, explain, and understand a particular phenomenon.

Qualitative research can be defined as a process of inquiry that builds a complex and holistic picture of a particular phenomenon of interest by using a natural setting. Thus, qualitative research involves the analysis of words, pictures, videos, or objects in the context in which they occur.

The goal of qualitative research is to understand social issues from multiple perspectives to have a comprehensive understanding of a particular event, person, or group. As with quantitative research, there are several key assumptions underlying qualitative research methods:

- Reality is socially constructed, and there are multiple realities.

- The researcher interacts and often works closely with the individuals or groups under study and serves as the primary instrument for data collection and analysis.

- The research is value laden, and the researchers become a part of the research, attempting to understand the lives and experiences of the people they study.

- Research is context bound and based on inductive forms of logic that emerge as a study progresses.

- The purpose of research is to find theories that help explain a particular phenomenon.

Comparing and Contrasting Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods

The following section examines how quantitative and qualitative methods are similar to and different from each other throughout the research process, beginning with the creation of a research question and up to the reporting of the results. Although examining quantitative and qualitative methods as two separate categories is necessary for the sake of clarification throughout this section, it is important to realize that these two methods are not mutually exclusive, a topic that will be discussed in more detail shortly. As Manheim, Rich, Willnat, and Brians (2007) note, when examining the differences between quantitative and qualitative methods, “The distinctions discussed are generally more matters of degree than absolutes. The two types of methods often require only different forms of work, but are working toward similar objectives” (p. 323). This is important to keep in mind while reading this article.

The first step in conducting sound political science research is selecting a research question. An appropriate research question should fulfill either a scientific need or a societal need by helping to provide an answer to an important problem. Both quantitative and qualitative forms of research begin by creating a research question that is intended to produce knowledge of the empirical world. In terms of the research questions, the main difference between quantitative and qualitative methods typically exists in the type of questions that are being posed.

A theory is a potential explanation for events and is composed of a set of logically related propositions and assumptions. Theorizing is the actual process of stating these conceptual explanations for events that take place in the real world by proclaiming relationships among the concepts. Theories are created to help people understand phenomena. There are several characteristics that make a theory particularly useful in explaining observations. Theories should be (a) testable, (b) logically sound, (c) communicable, (d) general, and (e) parsimonious.

Theorizing is a critical phase of the research process for quantitative and qualitative researchers. However, quantitative researchers are more likely than qualitative researchers to focus on testing performed theories. Quantitative researchers base their studies on a theory that relates to their subject in an attempt to develop generalizations that contribute to theory. Thus, in quantitative research, theorizing occurs prior to the collection of data. Qualitative researchers, on the other hand, are more likely than quantitative researchers to elaborate on theories while making observations of a particular phenomenon. Many qualitative researchers argue that, as a result of this, their theories are far more grounded in reality than are those of quantitative researchers. However, quantitative researchers argue that the formulation of theory during the observation-making process can easily lead to the creation of a theory designed around those specific observations. As a result, these theories would be polluted and not testable. Furthermore, if a theory is based on observation of one particular group, the usefulness of the theory is quite limited.

Simply defined, a research design is the plan of a study. It organizes observations in a manner that establishes a logical basis for causal inference. Essentially, the research design can be viewed as the blueprint for a study. There are three main types of research designs in political science: exploratory, descriptive, and explanatory. Exploratory research attempts to discover which factors should be included when theorizing about and researching a particular subject. Descriptive research attempts to measure some aspect of reality for its own sake and not for the purpose of developing or testing some theory. Explanatory research uses observations of reality to test hypotheses and help develop an understanding of patterns of behavior in the context of a specific theory.

Regardless of the purpose of a study, every research design should have the same basic elements, which are outlined by Manheim et al. (2007): (a) a statement outlining the purpose of the research; (b) a review of the theory and any hypotheses that are going to be tested, if applicable; (c) a statement explaining the variables that will be used; (d) an explanation of the operationalization and measurement of the variables; (e) a statement of how observations will be organized, as well as conducted; and (f) a discussion of how the data that are collected will be analyzed.

Although both quantitative and qualitative researchers produce research designs for their studies, quantitative researchers are much more likely than their counterparts to base their designs on the logic of experiments. For instance, quantitative researchers often emphasize control groups, pretests, and other elements that provide them with the opportunity to hold some factor(s) constant in their attempt to make causal inferences. Qualitative research designs, on the other hand, typically focus more on who or what is being observed, where the observation will take place, how observations will be conducted, and how the data will be recorded. For qualitative researchers, more emphasis is placed on viewing people and events as they naturally occur, while for quantitative researchers there is a greater focus on establishing cause-and-effect relationships.

A sample is a small group of cases drawn from and used to represent a larger population under consideration. A representative sample is a sample in which each major attribute of the larger population occurs in approximately the same proportion or frequency as in the larger population. “In other words, a truly representative sample is a microcosm—a smaller, but accurate model—of the larger population from which it is taken” (Manheim et al., 2007, p. 119). When a sample is representative, the conclusions drawn from it are generalizable to the entire population.

In quantitative studies, sampling is based on the logic of probability to produce statistical representativeness. Additionally, in quantitative research, sampling is done before the data are collected. Qualitative researchers, on the other hand, usually create their sample once their study is already in progress. After observing, learning about, and gaining understanding from an initial case, qualitative researchers are then able to determine what they will observe next. Additionally, whereas generalizability is a chief concern for quantitative researchers, this is not the case for qualitative researchers, who are far more concerned with finding the specific information that they are looking for from their sample. Since this method is very time-consuming, qualitative findings are often based on fewer cases than quantitative findings.

Data are observations or information about reality that represent attributes of variables and result from the research process. Although data collection is an integral part of both types of research methods, data are composed of words in qualitative research and numbers in quantitative research, which results in a data collection process that differs significantly for quantitative and qualitative research. Furthermore, the data collection process is different: Although quantitative researchers have the ability to administer a previously prepared questionnaire or watch an experiment unfold behind blind glass, qualitative researchers are engaged—sometimes for long periods of time—with the people or groups under study.

As can likely be seen by now, quantitative researchers frequently have a detailed plan of action that is thought out prior to the beginning of a study’s taking place. Qualitative researchers, on the other hand, tend to take a more fluid approach to their studies. This holds true for the analysis of data, as well. Whereas in quantitative studies, the data analysis methods are planned out in advance and then occur after the data are collected, data analysis typically takes place at the same time as data collection in qualitative studies. To make appropriate future observations, analyses must often begin after studying one to several initial cases. As a result, quantitative researchers are not usually afforded the opportunity to modify their methods of data collection during a project, while qualitative researchers can do so at any point in a project after conducting the initial data analysis.

Additionally, although qualitative data are more subjective and sometimes difficult to interpret, quantitative data are easily coded into numerical formats. As a result, it is much easier to enter quantitative data into computer programs, such as Excel and SPSS, than it is to enter qualitative data. Furthermore, there are a number of programs that analyze the statistical data, such as SPSS and Stata. Although programs do exist for the interpretation of qualitative data, they are not used nearly as extensively as those used for quantitative data analysis.

Finally, whereas quantitative researchers have a variety of means to test the statistical significance and validity of the data that they are analyzing, this is not the case for qualitative researchers. Instead, qualitative researchers must do their best to present a clear, accurate, and convincing analysis of their data. As a result, a topic of much debate between quantitative and qualitative researchers is the validity and reliability of findings produced in studies. Validity is the extent to which measures correspond to the concepts they are intended to reflect. Reliability is the consistency with which a measuring instrument allows assignment of values to cases when repeated over time. Although a measure can be reliable without being valid, it cannot be valid without being reliable.

Additionally, since one of the main points of conducting quantitative research is to study causal relationships, part of the process involves manipulating various factors that could potentially influence a phenomenon of interest while at the same time controlling for other variables that could affect the outcome. For instance, if a researcher were examining if gender played a role in whether a person received a job, it would be important to control for other variables, such as education or previous work experience, since these factors may also determine why an individual would receive an employment offer. In quantitative analysis, empirical relationships and associations are typically examined by using general linear models, nonlinear models, or factor analysis to understand important information about the relationship between variables, such as the direction of a relationship. However, despite the results that may be produced by these models, it is important to note that a major tenet of quantitative research is that correlation does not imply causation. In other words, a spurious relationship is always a possible result of the data analysis.

When presenting the results of a study, qualitative researchers often have an arduous task in front of them. Since their reports typically rely on the interpretation of observations, it is necessary for them to be very careful in the selection of what stories, quotations, pictures, and so on, they will share in order to avoid bias. The reports produced by quantitative researchers tend to be more straightforward since they rely mostly on the interpretation of statistics. But here, too, it is important to make sure that bias was avoided in the sample and that appropriate data analysis methods were used in order to avoid bias in quantitative analysis.

To sum up, there are a lot of similarities among quantitative and qualitative research methods. Irrespective of which method is used, it is still necessary to create an appropriate research question, understand the theory behind what will be observed, create a research design, collect and analyze data, and create a report of the results. However, there are several key differences between quantitative and qualitative research methods. These methods differ in (a) the types of questions that they pose, (b) their analytical objectives, (c) the amount of flexibility allowed in the research design, (d) the data collection instruments that are used, and (e) the type of data that are ultimately produced. According to Mack, Woodsong, MacQueen, Guest, and Namey (2005), the fifth difference is the biggest. The authors argue that quantitative methods are generally inflexible since categories are typically closed-ended or fixed, while qualitative methods are more flexible, with a large amount of spontaneity and adaptation occurring during interaction with other people, especially in the form of open-ended questions.

To decide which research approach should be used, several things should be taken into account, including the problem of interest, the resources available, the skills and training of the researcher(s), and the audience for the research. Since there are considerable differences in the assumptions that underlie these two research approaches, as well as the collection and analysis of data, these considerations are important. The following sections provide a more detailed examination of the various types of quantitative and qualitative research methods, as well as the limitations of these methods in general.

Quantitative Methods in Political Science

Quantitative methods are essentially a variety of research techniques that are used to gather quantitative data. There are a variety of different types of quantitative methods, which are briefly outlined in this section: experiments, quasi experiments, content analysis, and surveys. First, in experiments, participants are randomly assigned to experimental conditions, as well as experimental controls. The individuals who are assigned to experimental controls are testing the independent variable. The difference between experiments and quasi experiments is the way that subjects are selected. In quasi experiments, participants are assigned to experimental conditions in a nonrandom fashion.

Next, content analysis is a systematic means of counting and assessing information in order to interpret it. For instance, scholars may count the number of times that personal characteristics, such as dress or hairstyle, are mentioned in newspaper articles to determine whether media coverage of male and female candidates differs. Finally, surveys are used to estimate the characteristics of a population based on responses to questionnaires and interviews from a sample of the population. Surveys provide five types of information: (1) facts, (2) opinions, (3) perceptions, (4) attitudes, and (5) behavioral reports. Essentially, questionnaires and surveys can serve as a means for helping scholars understand why people feel or act the way that they do, as well as measure their attitudes and assess their behaviors.

There are three key criticisms of quantitative research that are discussed here. First, since quantitative research methods were adopted from the physical sciences, critics argue that all cases are treated as though they are alike. Complex concepts are turned into numbers, and their unique elements are dissipated as a result. Furthermore, people can easily attribute different meanings to something even when they are experiencing the same phenomena. Second, and related to the first criticism, some people argue that quantitative methods are inherently biased. Since they are adopted from the physical sciences, critics argue that quantitative methods fail to take into account the unique cultural roots and other critical aspects of marginalized groups of people. Thus, according to critics, when it comes to populations that have been politically excluded, the usage of quantitative methods may not be appropriate, according to critics. Third, critics argue that quantitative research methods result in taking individuals out of their natural settings to examine very limited aspects of what a person thinks or believes. To these critics, context is very important, and by taking actions out of context, it is impossible to understand the true meaning of events or responses.

Qualitative Methods in Political Science

Just as quantitative research methods have a variety of research techniques that are used to gather data, there are also a variety of qualitative methods. This section focuses on several of these: ethnographic studies, phenomenological studies, case studies, focus groups, and intense interviews. First, in ethnographic studies, researchers examine cultural groups in their natural setting. Examples of cultural groups can include students in a dormitory, women in a crisis center, or people from a village in Asia. This type of study can provide rich, detailed information about the individuals in various groups, since it involves first-hand observation.

Second, in phenomenological studies, a small group of people is studied intensively over a long period to understand the life experience of the individuals being studied. Phenomenological studies can involve direct or indirect observation. Additionally, depending on the study, the individuals being observed may or may not know the purpose of the study or what exactly is being observed. Sometimes the researcher relies on building a trusting relationship with the subjects so the subjects act as naturally as possible even though they are being observed. As a result of this closeness, the researcher can often tell when a person is modifying his or her behavior. However, it is not always possible to establish this kind of relationship. As a result, some researchers conceal the purpose of their studies from those being observed to avoid the modifying of behavior by the subject. This process of behavior modification by the respondent is called reactivity and can greatly affect the results of a study.

Third, in a case study, a case is studied by a researcher, and detailed information about the entity or phenomenon is recorded. Sometimes information that is found in a case study can lend itself to the content analytical techniques discussed in the previous quantitative research section. Other times, newspapers, books, interviews, or other sources may be used. In content analysis, researchers are looking for specific words, phrases, or general ideas that are relevant to their study. The researchers will then count the instances of these items to learn more about a particular subject. For instance, some political scientists are interested in learning about gender bias in the media. By examining how often a female versus a male candidate is mentioned in an article or the type of coverage the candidate receives, these scholars are able to draw conclusions about gender bias in the media.

Finally, there are two other ways to collect and analyze qualitative data that are of relevance in this section—focus groups and intense interviewing. Focus groups are in-depth studies composed of small groups of people who have guided discussions. For instance, a focus group may be shown a political advertisement that a political campaign hopes to air on television. After watching the advertisement, members of the group are asked questions, and a discussion is prompted in which they can discuss their feelings about the ad, such as what they liked and did not like, as well as whether they were swayed by the ad and found it to be credible. These responses allow the advertisement’s producers to make changes that make the ad more effective.

Intense interviews are similar to survey questionnaires in that the interviewer generally has some thoughts in mind about what the respondent will be asked. However, although survey questions are planned out in their entirety in advance, this is often not the case in intense interviews where the interviewee has the ability to ask follow-up questions or a variety of other questions related to an answer provided by the respondent. Additionally, whereas survey questionnaire responses tend to be closed-ended (a particular response can be chosen from those available), intense interview responses are typically open-ended (no response categories) and can be very detailed. Thus, researchers have more flexibility when conducting an intense interview than they would if they were administering a questionnaire; however, their results are typically not quantifiable.

Just as quantitative methods have their detractors, so too do qualitative methods. Some of the biggest criticisms of qualitative methods are outlined in this section. First, some critics argue that qualitative methods focus too much on particular individuals, sometimes at the expense of seeing the bigger picture, and they fail to make their results generalizable to a larger population. Second, critics note that the quality of the results and analysis that are produced are highly dependent on the skill of the researcher. It is necessary for the researcher to have remained unbiased and provide a clear assessment of the subjects under study, or the results are essentially meaningless. Third, it is very time-consuming to conduct qualitative research studies. The amount of time spent conducting interviews and making observations is just the beginning. After these take place, the researchers still have to figure out a way to analyze the vast amounts of information that they have collected to produce results.

As can be seen from the information provided throughout this article, there has been a raging decades-long debate as to whether qualitative or quantitative research is better. Many scholars focus on qualitative versus quantitative techniques, automatically framing these methods and approaches in opposition to each other. Although it may appear that qualitative and quantitative data exist in opposition to each other, this is not necessarily the case. As King, Keohane, and Verba (1994) argue, “The two traditions appear quite different; indeed they sometimes seem to be at war. Our view is that these differences are mainly ones of style and specific technique. The same underlying logic provides the framework for each research approach” (p. 3). As a result, research does not typically fit into one particular category or another.

Additionally, King et al. (1994) note that we live in a world that changes rapidly, and to fully understand the changes that occur around us, it is necessary to be able to take into account information that can be quantified, as well as information that cannot. Furthermore, since social science requires comparison, it is important to examine both quantitative differences (such as which phenomena are more or less alike in degree) and qualitative differences (such as which phenomena are more or less alike in kind).

In recent years, scholars have been focusing a lot more on triangulation. Triangulation is essentially the idea that more than one research technique can be used to examine a research question to further verify the findings. Triangulation can help improve confidence about the results produced from a study. Quantitative and qualitative research can frequently be integrated, creating mixed-methods research that can depict a clearer picture of a social science phenomenon than one single method on its own.

Another way that quantitative and qualitative methods can exist together is by coding qualitative data into quantitative data. Just about any type of qualitative data can be assigned meaningful numerical values that can be manipulated to help condense the information and gain a different and more generalizable understanding of the data. One frequently used example is open-ended questions. Although more detailed insight is gained from an open-ended question than a categorical question, open-ended questions can typically be broken down into simple numerical categories allowing for a quantitative analysis of the data.

The Research Network on Gender Politics and the State (RNGS) serves as another good example. The researchers in RNGS had been conducting a crossnational, longitudinal, qualitative research project that explored changes in public policy processes dating back to the 1960s. Starting in 2000, however, the researchers began to code their vast qualitative data into a large quantitative data file. By using quantitative coding, additional useful information may be garnered, and a new form of data analysis is possible. As can be seen here, sometimes the line between quantitative and qualitative analysis may not be so clear after all.

On the other hand, quantitative data is inherently based on qualitative judgment because it is impossible to interpret numbers without understanding the assumptions underlying the numbers. When a person provides a numerical response to a survey question, for instance, many assumptions and judgments are present. For instance, if a person, when asked, “How satisfied are you with your life?” responds, “Very satisfied” (denoted by a value of 1), a variety of other questions could be asked. What does satisfaction mean to this respondent? Was he or she thinking only of the economic climate? Job? Family? Relationships? How does he or she define satisfaction, and how does this differ from how the next person defines satisfaction? Did the respondent even pay attention to or think about the question, or was he or she just offering quick responses? When and in what context was this question presented? The list goes on. As can be seen from this brief example, what appeared to be a simple numerical piece of information actually involved numerous judgments about the meaning of each response.

Quantitative and qualitative analysis are two general approaches to the analysis of data. Both seek to explain trends but have different means of doing this. Additionally, quantitative and qualitative research methods are each based on a basic set of assumptions. Both forms of research carefully follow each step in the research process, from formulating a research question to reporting the results of the data analysis. However, the order and ways in which this process is completed differ between quantitative and qualitative methods because of the different goals that researchers using these methods have for their studies. Essentially, though, at some level, quantitative and qualitative data are inseparable and do not exist in complete opposition to each other. Thus, it is almost self-defeating to claim that one method is better than the other. There are times when one is more appropriate to use in a given situation than another, but often, they can both be used together, whether at the same time or in different stages. As research progresses through the 21st century, it is highly probable that more scholars will use mixed-methods approaches.

References:

- Achen, C. H. (1982). Interpreting and using regression. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Adcock, R., & Collier, D. (2001). Measurement validity: A shared standard for qualitative and quantitative research. American Political Science Review, 95, 529-546.

- Agresti, A., & Finlay, B. (1997). Statistical methods for the social sciences (3rd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Berg, B. L. (2003). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (5th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Box Steffensmeier, J.M., Brady, H. E., & Collier, D. (Eds.). (2008). The Oxford handbook of political methodology. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Brady, H., & Collier, D. (Eds.). (2004). Rethinking social inquiry: Diverse tools, shared standards. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. (2005). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Fink, A. (2005). How to conduct surveys: A step by step guide (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Frankfort Nachmias, C., & Nachmias, D. (1999). Research methods in the social sciences (6th ed.). New York: St. Martin’s.

- Frey, J. H., & Oishi, S. M. (2004). How to conduct interviews by telephone and in person. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Gerring, J. (2001). Social science methodology: A critical frame work. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Goodin, R. E., & Klingemann, H. D. (Eds.). (1996). A new hand book of political science. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Greene, J. C., Caracelli, V. J., & Graham, W. F. (1989). Towards a conceptual framework for mixed method evaluation designs. Education Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11, 255-274.

- Gujarati, D. N. (2002). Basic econometrics (4th ed.). New York: McGraw Hill.

- Hewson, C., Yule, P., Laurent, D., & Vogel, C. (2002). Internet research methods: A practical guide for the social and behavioural sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Hoover, K., & Donovan, T. (2004). The elements of social scientific thinking (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Isaak, A. C. (1975). Scope and methods of political science: An introduction to the methodology of political inquiry. Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press.

- Johnson, J. B., Reynolds, H. T., & Mycoff, J. D. (2007). Political science research methods (6th ed.). Washington, DC: CQ Press.

- Kinder, D. R., & Palfrey, T. R. (1993). Experimental foundations of political science. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- King, G., Keohane, R. O., & Verba, S. (1994). Designing social inquiry: Scientific inference in qualitative research. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Leege, D. C., & Francis, W. L. (1974). Political research: Design, measurement, and analysis. New York: Basic Books.

- Levy, P. S., & Lemeshow, S. (2003). Sampling of populations: Methods and applications (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley.

- Lohr, S. L. (1998). Sampling: Design and analysis. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury Press.

- Mack, N., Woodsong, C., MacQueen, K. M., Guest, G., & Namey, E. (2005). Qualitative research methods: A data collector’s field guide. Research Triangle Park, NC: Family Health International.

- Manheim, J. B., Rich, R. C., Willnat, L., & Brians, C. L. (2007). Empirical political analysis: Quantitative and qualitative research methods (7th ed.). Essex, UK: Longman.

- Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (1999). Designing qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- McNabb, D. E. (2009). Research methods for political science: Quantitative and qualitative methods (2nd ed.). Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Miller, D. C., & Salkind, N. J. (2002). Handbook of research design and social measurement (6th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Ott, L. R., & Longnecker, M. T. (2001). An introduction to statistical methods and data analysis. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Pollock, P., III. (2008). The essentials of political analysis. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

- Salmon, W. (1998). Causality and explanation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Shiveley, W. P. (1990). The craft of political research. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Silverman, D. (2001). Interpreting qualitative data: Methods for analyzing talk, text, and interaction (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Singleton, R. A., Jr., & Straits, B. C. (2004). Approaches to social research. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Weisberg, H. F., Krosnick, J. A., & Bowen, B. D. (1996). An introduction to survey research, polling, and data analysis (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Reader Interactions

Breadcrumbs Section. Click here to navigate to respective pages.

Research Methods for Political Science

DOI link for Research Methods for Political Science

Get Citation

Thoroughly updated, more concise than the previous edition, and available for the first time in paperback, "Research Methods for Political Science" is designed to help students learn what to research, why to research, and how to research. The text integrates both quantitative and qualitative approaches to research in one volume, and includes the most comprehensive coverage of qualitative methods currently available. It covers such important topics as research design, specifying research problems, designing questionnaries and writing questions, designing and carrying out qualitative research, and analyzing both quantitative and qualitative research data. Heavily illustrated, classroom tested, and exceptionally readable and engaging, the text also provides specific instructions on the use of available statistical software programs such as Excel and SPSS.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Part | 2 pages, part 1 foundations of political science research, chapter 1 | 12 pages, research fundamentals, chapter 2 | 14 pages, research approaches and methods, chapter 3 | 11 pages, understanding the research process, chapter 4 | 17 pages, selecting a research design and choosing a research topic, chapter 5 | 9 pages, preparing a research proposal, chapter 6 | 11 pages, the legal and ethical environment of research, part 2 quantitative research approaches and methods, chapter 7 | 17 pages, introduction to quantitative methods, chapter 8 | 13 pages, exploratory research: the probing approach, chapter 9 | 16 pages, descriptive research: the survey approach, chapter 10 | 16 pages, causal research: the experimental approach, chapter 11 | 16 pages, interpreting exploratory and descriptive statistics, chapter 12 | 19 pages, testing research hypotheses, chapter 13 | 16 pages, introduction to nonparametric statistics, chapter 14 | 15 pages, correlation and regression analysis in political science, chapter 15 | 16 pages, exploring multivariate statistics, part 3 qualitative research approaches and methods, chapter 16 | 11 pages, introduction to qualitative research methods, chapter 17 | 15 pages, explanatory research: case and historical methods, chapter 18 | 13 pages, the interpretive approach i: grounded theory methods, chapter 19 | 12 pages, the interpretive approach ii: ethnographic research methods, chapter 20 | 11 pages, the critical approach: feminist and empowerment research, chapter 21 | 16 pages, analysis methods for qualitative data, chapter 22 | 24 pages, analyzing texts, documents, and artifacts, part 4 preparing and presenting research findings, chapter 23 | 15 pages, organizing information in tables, charts, and graphs, chapter 24 | 20 pages, organizing and writing a research report, chapter 25 | 19 pages, introduction to statistical software.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Taylor & Francis Group

- Students/Researchers

- Librarians/Institutions

Connect with us

Registered in England & Wales No. 3099067 5 Howick Place | London | SW1P 1WG © 2024 Informa UK Limited

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8 Chapter 10: Methods

Understanding political methodology requires us to return to a few key concepts from previous chapters. The basics of social science inquiry is to explain causation—what causes what—in political, social, or economic phenomena.

There are two variables in this causal relationship: the dependent and independent variables. The dependent variable is the outcome we seek to isolate and study in order to determine what caused it. Independent variables are the potential causes of the dependent variable in question. Once we determine the dependent variable as the focus of the study and a number of independent variables that could potentially be the cause, we need tools, or methods, to observe and draw conclusions. Key to this inquiry is determining the right methods that best explain the phenomenon in question. Once we establish the methods then we can begin the process of data collection, observation, analysis, and inference.

A fundamental divide in methods for political science is the distinction between quantitative and qualitative methods. Quantitative methods principally combines statistics, mathematics, and formal theory as tools for positive research in political science. It is a data-driven approach in which collection, analysis, interpretation, and presentation of numerical data provides inferences and insights into key political questions. Positive research, as previously mentioned, seeks to describe and explain what is, and is in contrast with normative research that seeks prescriptions of what ought to be. Qualitative methods entail a set of tools for explaining political phenomena that are not numerical or statistical and does not seek to count or measure data. Instead, a qualitative approach uses description and observation of non-numerical data to draw inferences. Not all data can be quantified in a way that is useful, particularly human-related data such as behavior or belief, and qualitative methods help us fill the gap. As a sub-field in political science, political methodology is principally the study of how methods are used in the discipline. It is a practical, hands on sub-discipline that gives students direct access to the tools of political inquiry.

Let’s review a few key concepts and approaches in political methodology. First, we will consider some terms and approaches in quantitative methods. Second, we will look at some core principles and dominant approaches to qualitative methods. Lastly, we will discuss the basics of developing a research project that will serve as a template for students to create their own research agenda.

Correlations

Statistical correlations are the most common tool in quantitative methods. Correlations measure the relationship between two variables. A positive correlation implies a relationship in which an increase or decrease in numerical value of one variable corresponds to a similar increase or decrease in the other variable. As an example, let’s look at the relationship between wealth and voting participation: several studies have found a positive correlation between these variables such that higher levels of wealth correspond to a higher likelihood of voting. [1] Moreover, lower levels of wealth tend to correspond to a lesser likelihood of voting. A negative correlation implies a relationship in which one variable increases when the other variable decreases, or vice versa. Let’s consider the variable of voter turnout—what are some variables that can be negatively correlated to voter turnout? We may think of a number of variables that could be tested, such as bad weather, a more stringent registration process, high levels of poverty, or low levels of education. We can test these variables and hopefully gain some insight into what drives higher voter turnout and what obstacles there are to voting.

A correlation, it has often be said, does not necessarily imply causation, but correlations are an indication that there may be causation or some meaningful relationship that can provide insight into political inquiry. Suppose we just collected and analyzed data, maybe for years, gathering mountains of information. Assume further that we organize this information and present it in an accessible and attractive way. What’s missing in this research project? Data can be collected, organized, analyzed, and presented, but at the end of the day the political scientist must ask, “okay, what does all this mean ?” What conclusions can be drawn from the analysis of data? What questions remain? The methodological work of a political scientist is not done once a statistical regression is run and a correlation between two variables is determined. An important next step is the task of inference—drawing conclusions based on the correlation and perhaps other observations and correlations as well. Drawing inferences is an essential scientific activity that directly probes the meaning of data and analysis.

Let’s return to the example of a positive correlation between wealth and voting participation. What does this really mean? We may logically infer one thing it does not mean: that voting makes you more wealthy. Voter turnout is the dependent variable in this analysis—an outcome for which we seek causal explanation. It may be that individuals who are wealthy are more likely to volunteer, participate in other civic and political endeavors, run for office, and the like. In this case, wealth may not be such a powerful explanation for voter turnout, but rather a variable that increases the likelihood of many different forms of political participation. On the other hand, wealth may be a more direct cause of voter turnout: the correlation between these two variables may be noticeably higher than between wealth and volunteerism or wealth and running for office. Additionally, we may draw an inference that voting participation increases with wealth because individuals may feel as though they have a larger stake in the political process or are at risk of paying more taxes, etc. This inference suggests a tighter link between wealth and voter participation.

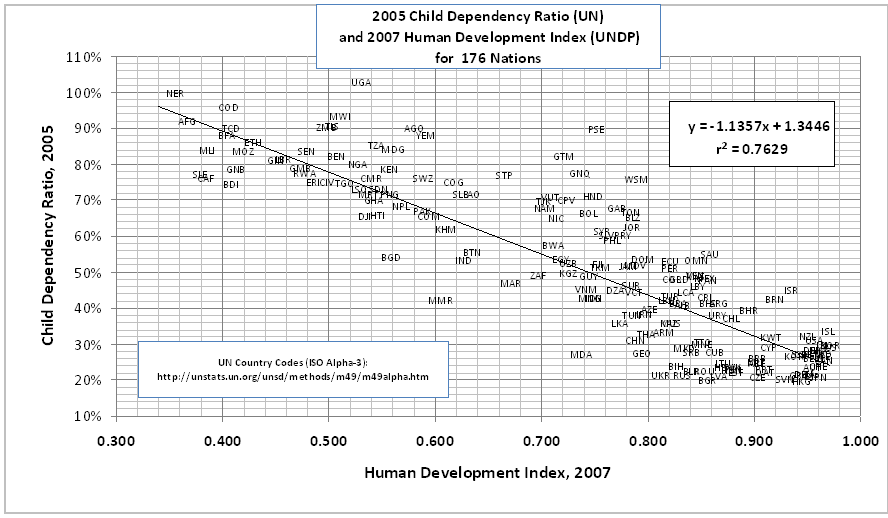

Here is an example of a correlation represented with a scatter plot:

This scatter plot shows the correlation between child-dependency ratio and the UN Human Development Index. A child-dependency ratio is derived by taking the number of dependents (14 years of age and younger and 65 years of age and older) and dividing it by the total population. The N in this statistic is 176: the number of nations in the study. What this statistic suggests is that there is a negative correlation between these values—higher child-dependency ratios correspond to lower human development.

Key Terms in Mathematical Modeling

Doing the work of political science often involves statistics to gather, observe, and organize data, and so it is necessary to understand some basic elements of statistical work. Typically, one begins with a population , the universe of event numbers associated with your study. Out of this population, a researcher can derive a sample that can be observed. Random samples have the advantage of being free from any presumptions a researcher might have and are thus likely to be unbiased. The overall number in a sample is referred to as N. If you survey a random sample of 1,500 people asking them whether they approve or disapprove of a particular politician, the N in this survey is 1,500. A statistic, a numerical measure that describes some property of the population, can be pulled from this sample and analyzed. This statistic will include some form of numerical, or quantitative, data.

There are broadly two types of quantitative data: discrete data, which are typically integers which cannot be divided further or be made more precise, and continuous data, which can be divided into smaller and more precise measurements. An example of discreet data would be the number of representatives in Congress who voted for a particular bill. This will be a whole number that cannot be divided—you cannot have a half or quarter of a representative who voted, the number may be 212 or 213, but cannot be 212.5. An example of continuous data would be the average number of representatives in Congress who voted for appropriations bills over a 10-year period of time. This number could be 212 or 213, but it could also be 212.5 or 212.275.

Data can also be derived from surveys or experiments. Surveys derive data from responses by a group of participants. This group is a sample from the overall population. Survey results can be generalized to the larger population but they are less than precise in predicting causation. Experiments are controlled observations of a particular phenomena and provide experimental data that is not easily generalized but can more precisely predict causation. In political science, conducting experiments can sometimes be impossible, whereas researchers often rely on surveys. The result is that causation is harder to predict in political science, as well as the other social sciences, compared to the natural or so-called hard sciences, where experiments are much more common.

A particular statistic may give us a probability—the likelihood of an event or outcome happening. Further, we may get a probability distribution, which indicates a scale of possible outcomes based on the likelihood of occurring. Probability distributions may be discrete (only certain values, such as whole numbers) or continuous (a range of possible values), along the lines described above. The distribution of data across a scale will provide a mean, median, and mode. A mean is a measure of central tendency, the average of the numbers on the scale, which can be achieved by adding up the value of all the numbers and dividing by how many numbers there are. The median is not an average but the central value on a scale. The mode is the value that occurs most frequently in the scale. If your data scale is the following: 2, 4, 5, 9, and 9, then the mean would be (2+4+5+9+9=29/5=) 5.8, whereas the median would be the value in the middle of this scale (5), and the mode would be 9, the most frequently occurring number.

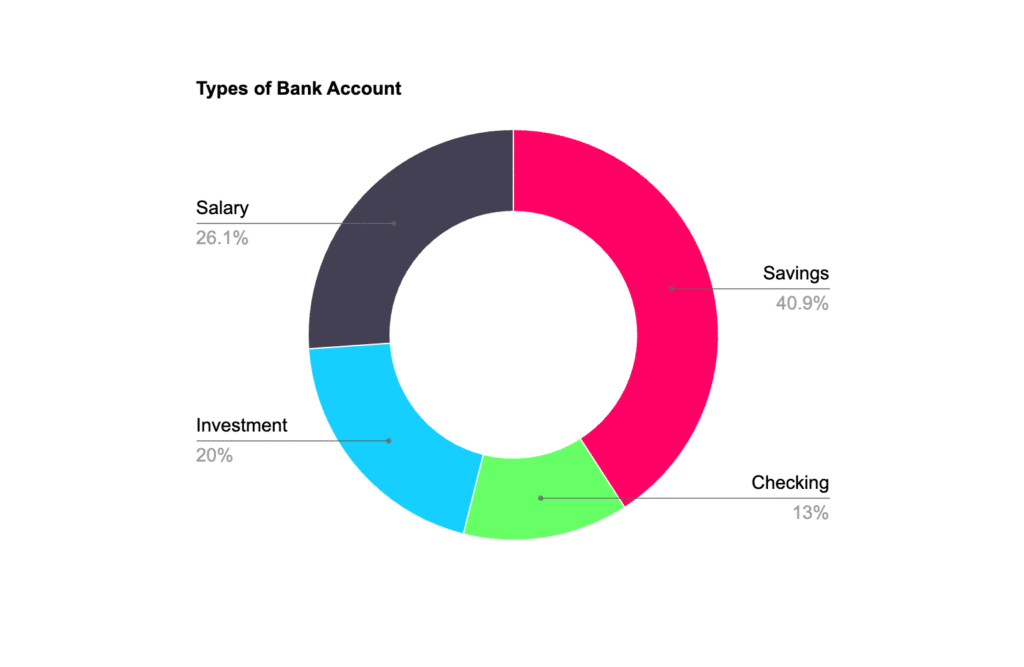

Lastly, we may present data in a number of ways that will be helpful for analysis and drawing inferences. A bar and whisker plot is a representation of groups of numerical data based on quartiles. The box in a box and whisker plot is the area of the inner two quartiles, whereas the whiskers (lines extended out from the boxes) are the highest and lowest quartiles respectively. A bar chart will show the frequency in each value by the height of a bar that represents that value and typically shows the relationship between two variables. A histogram will represent the frequency of values in intervals or “bins” which should be adjacent to one another but do not have to be equal. Histograms typically represent only one variable. A pie chart is a circular graph that shows portions of the total with wedges that represent the size of that proportion. A pareto chart contains both bars and a line graph, the bars representing descending frequency for each value and the line graph representing the cumulative total of frequencies. Finally, a scatter plot locates values (represented as points) along a plot typically determined by two variables, one along the X axis and the other along the Y axis, and can contain a third variable if the points are coded (by color or size, for example).

Qualitative methods

As previously mentioned, not all data can be numeric. Typically, human-related data that is subjective cannot be meaningfully quantified but may nonetheless be important to your research. The meaning of why or the description of how may be essential for answering your research, particularly why and how questions related to the human experience. Quantitative approaches can only count and measure, not give us the why or the how. Qualitative methods seeks to fill in the gap by providing a set of tools that allows for data collection, analysis, organization, and presentation. The typical qualitative approach is the case study—a focused, in-depth account of a single individual, group, organization, action, or event. Researchers who seek more context, depth, and detail of a single case are best suited to the qualitative method, where the absence of large amounts of numerical data make quantitative data collection and analysis impossible. Case studies in themselves are not confined to qualitative data, however, and may employ a mix of both qualitative and quantitative methods and data. A qualitative case study will provide a “thick description” of the case, focusing on the why and how of various phenomena that occur. [2]

In selecting a case, typical or average cases often do not reveal rich detail of information or are meaningful in their context and characteristics. Unique or outlier cases often prove more interested to explain. Because of this, random-sampling of cases, while useful to the quantitative method, are less useful in the qualitative approach. Cases may be selected based on the inherent and unique characteristics of the case, the context that surrounds it, or because the researcher has the prior depth of knowledge of the characteristics or culture of the case that would allow them to immerse themselves in the environment and provide descriptions or accounts that are meaningful. A qualitative case study is therefore less generalizable than quantitative research—if you are providing a thick description of a single, unique case, it makes sense that this case will not tell you very much about other cases. In contrast, quantitative research that includes large amounts of numerical data affords researchers better opportunities to generalize and make claims across cases.

Qualitative research can collect data in a variety of ways, such as interviews, storytelling, analysis of narratives, participant observations, or focus groups, among others. Interviews are a common form of qualitative data collecting in which a researcher asks questions to subjects that are important to the case. Interviews may be highly structured, in which questions are determined beforehand and there is no deviation from the list of questions, or unstructured, in which the researcher and subject engage in open-ended dialog. Narratives and storytelling can be important to understanding a particular culture or community, since stories can form a kind of discursive foundation on which common knowledge is shared and common action is determined. Participant observations can be a good way for a researcher to collect data through simply observing a group interact with one another. Such observations can be passive in the sense that the researcher attempts to remove themselves from the dynamic as much as possible so as not to influence the outcomes, or it can be active, in which a researcher is part of the group interactions and makes observations from within the context of the dynamic. Finally, focus groups allow for more controlled observations of specific interactions and allow a researcher to gather more contextualized data (such as reactions, agreement, or disagreement) than would be possible in isolated interviews.

Field research is a broad term we use to describe data collection and observation on the ground, removed from the academic setting. It is in your field research that you would conduct interviews, focus groups, or participant observations. As discussed in the comparative politics context in Chapter 7, researchers should determine which case is best to study given practical considerations on the ground, the most appropriate form of data collection (interviews, etc.), how long the field research should be conducted (short stays may be more directed, long stays may yield more data), and what sort of resources and skills would be necessary to conduct the research successfully.

Research Design

Designing a research project can be daunting, but it is also an exciting, hands-on way for students to learn more about issues they care about, understand the work of political science and its relevance, and gain insight into how political action and change might make a better world. Outlined below are the basic elements required to begin a research project, a brief description of each of those elements, and a rubric for each element that can give teachers and students a guide as to how a research project assignment may be evaluated. Keep in mind, this outline is not the research itself, only a template. No data will actually be gathered, analyzed, and assessed, and no inferences are drawn.

- Research question (RQ).

- Identify your dependent variable (DV), ie, the focus of your study.

- Potential answers (IVs) to the RQ, ie, the explanation for your DV outcome.

- Why does this question matter (SFW)? What relevance does this have? Why is it important?

- Choose method of data collection and analysis: quantitative (QN), qualitative (QL) or both (BQ)

- Determine form of method for data collection and the ideal data (D). For QN, identify specific statistics and different representations of variables (scatter plot, pie chart, bar graph, etc). You do not actually have to find this data or compile it, so its best to think of this as the ideal data possible for you to answer your question. In the best possible world, what numerical data would I need to best answer the RQ? For QR, determine a unique or outlier case that makes for interesting study. Determine the basic framework of your field research (short or long stay, resources and skills needed, etc.), and identify at least two forms of data collection (interviews, participant observations, etc).

- Identify which political science sub-field is the best fit for this research project.

- An annotated bibliography (BIB) of at least 6 scholarly sources (books or articles, including online sources) that provide some overview or analysis of your topic and can serve as sources for a literary review or extensive background information. This BIB is not a list of your ideal data, but rather scholarly or reputable sources that pertain to the issues surrounding your RQ.

Political methodology is the tool box we use to put theory (ideas about our political world) into practice. Methods allow us test theories, ideas, and assumptions we have, refining our understanding of politics and drawing out meaningful insights and inferences. The vast majority of political inquiry is an inquiry into causation on one level or another, and so research in political science requires a structure that can explain the causes of political phenomena. The first step is designing a research question—developing a starting point of inquiry that is centered on change or variation of some kind. What explains this particular change we see? Why do we get x and not y? Why are two seemingly similar cases produced different outcomes? The explanations or causes are independent variables in social science inquiry, and the dependent variable is the outcome of this change. Typical research in political science will center their study on the dependent variable and seek to explain how this outcome came about by identifying and analyzing independent variables that have potentially caused this outcome. Methods are the tools used to collect and analyze data, scrutinize the independent variables in question, and draw inferences that best explain causes of the dependent variable in question.

Broadly, there are two approaches in political methodology, quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative research typically entails large amounts of numerical data that require mathematical modeling—statistics—to analyze the variables in question. Correlations are statistical indicators that measure the mutual dependence or association between two variables and are commonly used in political science research. These correlations may indicate causation, but not necessarily—the researcher must draw inferences and analyze the strength of the association in order to make claims of causation. Qualitative research entails the collection of non-numerical data, often human-related experiences that are difficult to quantify. Such qualitative data can include interviews, participant observations, and focus groups conducted in field research. Both quantitative and qualitative research should be driven by a research question—a precise, non-banal question that directly centers on explaining some kind of political phenomena we observe in the world.

Media Attributions

- Plot-of-Human-Development-Index-2007-and-Child-Dependency-Ratios-2005-for-176-countries © Fm122 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- CNH_Figure_2 © Conhegarty is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1920px-Yale_climate_US_public_opinion_2018_bar_chart © Yale Program on Climate Change Communication is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Labeled_Box_and_Whisker_Plot © KStrileckis

- Histogram_of_Palestinian_rocket_attacks_on_Israel_per_day,_2014 © Kozrty is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- RootCauseParetoChart © KellyLawless is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- World Economic Forum, "Link Between Voting in Elections and Income." 2018: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/07/low-voter-turnout-increasing-household-income-may-help (accessed on July 28, 2019). ↵

- The phrase "thick description" comes from Clifford Geertz, "Thick Description: Towards an Interpretive Theory of Culture," in The Interpretation of Cultures. Basic Books: 1973 ↵

In statistics, a population is a universe of event numbers under study.

Politics, Power, and Purpose: An Orientation to Political Science Copyright © 2019 by Jay Steinmetz is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Political Science

Volume 20, 2017, review article, qualitative methods.

- John Gerring 1

- View Affiliations Hide Affiliations Affiliations: Department of Government, University of Texas, Austin, Texas 78712; email: [email protected]

- Vol. 20:15-36 (Volume publication date May 2017) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-092415-024158

- First published as a Review in Advance on January 11, 2017

- © Annual Reviews

One might argue that political science has gone further than any other social science in developing a rigorous field of study devoted to qualitative methods. This review article begins by discussing the time-honored qualitative/quantitative distinction. What is qualitative data and analysis, and how does it differ from quantitative data and analysis? I propose a narrow definition of “qualitative” and explore its implications. I also explore in a speculative vein some of the factors underlying the ongoing Methodenstreit between scholars who identify with quantitative and qualitative approaches to social science. In the remainder of the article I discuss areas of qualitative research that have been especially fecund over the past decade. These include case selection, causal inference, and multimethod research.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

Literature Cited

- Ahmed A , Sil R . 2012 . When multi-method research subverts methodological pluralism—or, why we still need single-method research. Perspect. Polit. 10 : 4 935– 53 [Google Scholar]

- Alesina A , Glaeser E , Sacerdote B . 2001 . Why doesn't the US have a European-style welfare state?. Brookings Pap. Econ. Act. 2 : 187– 277 [Google Scholar]

- Beach D , Pedersen RM . 2013 . Process-Tracing Methods: Foundations and Guidelines Ann Arbor: Univ. Mich. Press [Google Scholar]

- Beck N . 2006 . Is causal-process observation an oxymoron?. Polit. Anal. 14 : 3 347– 52 [Google Scholar]

- Beck N . 2010 . Causal process “observations”: oxymoron or (fine) old wine. Polit. Anal. 18 : 4 499– 505 [Google Scholar]

- Bennett A . 2008 . Process tracing: a Bayesian approach. See Box-Steffensmeier et al. 2008 702– 21

- Bennett A . 2015 . Disciplining our conjectures: systematizing process tracing with Bayesian analysis. See Bennett & Checkel 2015 276– 98

- Bennett A , Checkel JT . 2015 . Process Tracing: From Metaphor to Analytic Tool Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Bennett A , Elman C . 2006a . Complex causal relations and case study methods: the example of path dependence. Polit. Anal. 14 : 3 250– 67 [Google Scholar]

- Bennett A , Elman C . 2006b . Qualitative research: recent developments in case study methods. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 9 : 455– 76 [Google Scholar]

- Blatter J , Haverland M . 2012 . Designing Case Studies: Explanatory Approaches in Small-N Research Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan [Google Scholar]

- Boas TC . 2007 . Conceptualizing continuity and change: the composite-standard model of path dependence. J. Theor. Polit. 19 : 1 33– 54 [Google Scholar]

- Boix C . 1999 . Setting the rules of the game: the choice of electoral systems in advanced democracies. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 93 : 3 609– 24 [Google Scholar]

- Box-Steffensmeier J , Brady H , Collier D . 2008 . Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Brady HE . 2010 . Data-set observations versus causal-process observations: the 2000 U.S. presidential election. See Brady & Collier 2010 237– 42

- Brady HE , Collier D . 2004 . Rethinking Social Inquiry: Diverse Tools, Shared Standards Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield [Google Scholar]

- Brady HE , Collier D . 2010 . Rethinking Social Inquiry: Diverse Tools, Shared Standards Lanham, MD: Rowan & Littlefield, 2nd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer J , Hunter A . 2006 . Foundations of Multimethod Research: Synthesizing Styles Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J . 2009 . Is there a quantitative-qualitative divide in comparative politics. ? In The SAGE Handbook of Comparative Politics T Landman, N Robinson 67– 83 Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay R , Duflo E . 2004 . Women as policy makers: evidence from a randomized policy experiment in India. Econometrica 72 : 5 1409– 43 [Google Scholar]

- Collier D . 2011 . Understanding process tracing. PS Polit. Sci. Polit. 44 : 4 823– 30 [Google Scholar]

- Collier D , Elman C . 2008 . Qualitative and Multimethod Research: Organizations, Publications, and Reflections on Integration See Box-Steffensmeier et al. 2008 779– 95 [Google Scholar]

- Collier D , Gerring J . 2009 . Concepts and Method in Social Science: The Tradition of Giovanni Sartori New York: Routledge [Google Scholar]

- Collier D , LaPorte J , Seawright J . 2012 . Putting typologies to work: concept formation, measurement, and analytic rigor. Polit. Res. Q. 65 : 1 217– 32 [Google Scholar]

- Crandell JL , Voils CI , Chang YK , Sandelowski M . 2011 . Bayesian data augmentation methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research findings. Qual. Quant. 45 : 653– 69 [Google Scholar]

- Dunning T . 2012 . Natural Experiments in the Social Sciences: A Design-Based Approach Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein H . 1975 . Case studies and theory in political science. Handbook of Political Science. Political Science: Scope and Theory 7 FI Greenstein, NW Polsby 94– 137 Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley [Google Scholar]

- Elman C . 2005 . Explanatory typologies in qualitative studies of international politics. Int. Organ. 59 : 2 293– 326 [Google Scholar]

- Elman C , Kapiszewski D . 2014 . Data access and research transparency in the qualitative tradition. PS Polit. Sci. Polit. 47 : 1 43– 47 [Google Scholar]

- Elman C , Kapiszewski D , Vinuela L . 2010 . Qualitative data archiving: rewards and challenges. PS Polit. Sci. Polit. 43 : 1 23– 27 [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LD . 1964 . A comparative study of Canadian parties. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 58 : 46– 59 [Google Scholar]

- Fairfield T . 2013 . Going where the money is: strategies for taxing economic elites in unequal democracies. World Dev. 47 : 42– 57 [Google Scholar]

- Fairfield T . 2015 . Private Wealth and Public Revenue in Latin America: Business Power and Tax Politics Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Fenno RF Jr . 1977 . U.S. House members in their constituencies: an exploration. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 71 : 3 883– 917 [Google Scholar]

- Fenno RF Jr . 1978 . Home Style: House Members in Their Districts Boston, MA: Little, Brown [Google Scholar]

- Ferwerda J , Miller N . 2014 . Political devolution and resistance to foreign rule: a natural experiment. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 108 : 3 642– 60 [Google Scholar]

- Feyerabend P . 1975 . Against Method London: New Left Books [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M , Schwartz A . 1963 . A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960 Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel H . 1967 . Studies in Ethnomethodology Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall [Google Scholar]

- George AL . 1979 . Case studies and theory development: the method of structured, focused comparison. Diplomacy: New Approaches in History, Theory, and Policy PG Lauren 3– 68 New York: Free Press [Google Scholar]

- George AL , Bennett A . 2005 . Case Studies and Theory Development Cambridge, MA: MIT Press [Google Scholar]

- George AL , McKeown TJ . 1985 . Case studies and theories of organizational decision-making. Advances in Information Processing in Organizations RF Coulam, RA Smith 21– 58 Greenwich, CT: JAI Press [Google Scholar]

- Gerring J . 2007 . Case Study Research: Principles and Practices Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Gerring J . 2012 . Mere description. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 42 : 4 721– 46 [Google Scholar]

- Gerring J . 2017 . Case Study Research: Principles and Practices Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2nd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Gerring J , Cojocaru L . 2016 . Selecting cases for intensive analysis: a diversity of goals and methods. Sociol. Methods Res. 45 : 3 392– 423 [Google Scholar]

- Gerring J , McDermott R . 2007 . An experimental template for case-study research. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 51 : 3 688– 701 [Google Scholar]

- Gill CJ , Sabin L , Schmid CH . 2005 . Why clinicians are natural Bayesians. BMJ 330 : 1080– 83 [Google Scholar]

- Glassner B , Moreno JD . 1989 . The Qualitative-Quantitative Distinction in the Social Sciences Dordrecht, Neth.: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Goertz G . 2005 . Social Science Concepts: A User's Guide Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Goertz G . 2017 . Multimethod Research, Causal Mechanisms, and Selecting Cases: The Research Triad Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Goertz G , Mahoney J . 2012 . A Tale of Two Cultures: Qualitative and Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Grimmer J , Stewart BM . 2013 . Text as data: the promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Polit. Anal. 21 : 3 267– 97 [Google Scholar]

- Hall PA . 2003 . Aligning ontology and methodology in comparative politics. Comparative Historical Analysis in the Social Sciences J Mahoney, D Rueschemeyer 373– 404 Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Hall PA . 2006 . Systematic process analysis: when and how to use it. Eur. Manag. Rev. 3 : 24– 31 [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley M . 1992 . Deconstructing the qualitative-quantitative divide. Mixing Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Research J Brannen Aldershot, UK: Avebury [Google Scholar]

- Harrits GS . 2011 . More than method? A discussion of paradigm differences within mixed methods research. J. Mixed Methods Res. 5 : 2 150– 66 [Google Scholar]

- Herron MC , Quinn KM . 2016 . A careful look at modern case selection methods. Sociol. Methods Res. 45 : 3 458– 92 [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys M , Jacobs AM . 2015 . Mixing methods: a Bayesian approach. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 109 : 4 653– 73 [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys M , Jacobs AM . 2018 . Integrated Inferences: A Bayesian Integration of Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches to Causal Inference Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press. In press [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs A . 2015 . Process tracing the effects of ideas. See Bennett & Checkel 2015 41– 73

- Kapiszewski D , MacLean LM , Read BL . 2015 . Field Research in Political Science: Practices and Principles Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Karl TL . 1997 . The Paradox of Plenty: Oil Booms and Petro-States Berkeley: Univ. Calif. Press [Google Scholar]

- King G , Keohane RO , Verba S . 1994 . Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Kocher M , Monteiro N . 2015 . What's in a line? Natural experiments and the line of demarcation in WWII occupied France Work. Pap., Dep. Polit. Sci., Yale Univ. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzer M . 2010 . Historical knowledge and quantitative analysis: the case of the origins of proportional representation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 104 : 369– 92 [Google Scholar]

- Levy JS . 2007 . Qualitative methods and cross-method dialogue in political science. Comp. Polit. Stud. 40 : 2 196– 214 [Google Scholar]

- Levy JS . 2008 . Case studies: types, designs, and logics of inference. Confl. Manag. Peace Sci. 25 : 1– 18 [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman ES . 2005 . Nested analysis as a mixed-method strategy for comparative research. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 99 : 3 435– 52 [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman ES . 2010 . Bridging the qualitative-quantitative divide: best practices in the development of historically oriented replication databases. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 13 : 37– 59 [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman ES . 2016 . Can the biomedical research cycle be a model for political science?. Perspect. Polit. 14 1054– 66 [Google Scholar]

- Lijphart A . 1971 . Comparative politics and the comparative method. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 65 : 682– 93 [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann S . 2007 . The trouble with multi-methodism. Newsl. APSA Organ. Sect. Qual. Methods 5 : 1 13– 17 [Google Scholar]

- Lynd RS , Lynd HM . 1956 (1929) . Middletown: A Study in American Culture. New York: Harcourt Brace [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney J . 2010 . After KKV: the new methodology of qualitative research. World Polit. 62 : 1 120– 47 [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney J . 2012 . The logic of process tracing tests in the social sciences. Sociol. Methods Res. 41 : 4 566– 90 [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney J , Goertz G . 2006 . A tale of two cultures: contrasting quantitative and qualitative research. Polit. Anal. 14 : 227– 49 [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney J , Sweet Vanderpoel R . 2015 . Set diagrams and qualitative research. Comp. Polit. Stud. 48 : 1 65– 100 [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney J , Thelen K . 2015 . Advances in Comparative-Historical Analysis Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield ED , Snyder J . 2005 . Electing to Fight: Why Emerging Democracies Go to War Cambridge, MA: MIT Press [Google Scholar]

- McKeown TJ . 1999 . Case studies and the statistical world view. Int. Organ. 53 : 161– 90 [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin E . 1991 . Oppositional poverty: the quantitative/qualitative divide and other dichotomies. Sociol. Rev. 39 : 292– 308 [Google Scholar]

- Mill JS . 1843/1872 . A System of Logic. London: Longmans, Green, 8th ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Moore B Jr. . 1966 . Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World. Boston, MA: Beacon Press [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M . 2012 . Case studies: one observation or many? Justification or discovery?. Philos. Sci. 79 : 5 655– 66 [Google Scholar]

- Page SE . 2006 . Essay: path dependence. Q. J. Polit. Sci. 1 : 87– 115 [Google Scholar]

- Paluck EL . 2010 . The promising integration of qualitative methods and field experiments. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 628 : 59– 71 [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ . 2002 . Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Pincus S . 2011 . 1688: The First Modern Revolution New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Platt J . 1992 . “Case study” in American methodological thought. Curr. Sociol. 40 : 1 17– 48 [Google Scholar]

- Posner D . 2004 . The political salience of cultural difference: why Chewas and Tumbukas are allies in Zambia and adversaries in Malawi. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 98 : 4 529– 46 [Google Scholar]

- Ray JL . 1993 . Wars between democracies: rare or nonexistent?. Int. Interact. 18 : 251– 76 [Google Scholar]