Guide to the classics: Michel de Montaigne’s Essays

Associate Professor in Philosophy, Deakin University

Disclosure statement

Matthew Sharpe is part of an ARC funded project on modern reinventions of the ancient idea of "philosophy as a way of life", in which Montaigne is a central figure.

Deakin University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

When Michel de Montaigne retired to his family estate in 1572, aged 38, he tells us that he wanted to write his famous Essays as a distraction for his idle mind . He neither wanted nor expected people beyond his circle of friends to be too interested.

His Essays’ preface almost warns us off:

Reader, you have here an honest book; … in writing it, I have proposed to myself no other than a domestic and private end. I have had no consideration at all either to your service or to my glory … Thus, reader, I myself am the matter of my book: there’s no reason that you should employ your leisure upon so frivolous and vain a subject. Therefore farewell.

The ensuing, free-ranging essays, although steeped in classical poetry, history and philosophy, are unquestionably something new in the history of Western thought. They were almost scandalous for their day.

No one before Montaigne in the Western canon had thought to devote pages to subjects as diverse and seemingly insignificant as “Of Smells”, “Of the Custom of Wearing Clothes”, “Of Posting” (letters, that is), “Of Thumbs” or “Of Sleep” — let alone reflections on the unruliness of the male appendage , a subject which repeatedly concerned him.

French philosopher Jacques Rancière has recently argued that modernism began with the opening up of the mundane, private and ordinary to artistic treatment. Modern art no longer restricts its subject matters to classical myths, biblical tales, the battles and dealings of Princes and prelates.

If Rancière is right, it could be said that Montaigne’s 107 Essays, each between several hundred words and (in one case) several hundred pages, came close to inventing modernism in the late 16th century.

Montaigne frequently apologises for writing so much about himself. He is only a second rate politician and one-time Mayor of Bourdeaux, after all. With an almost Socratic irony , he tells us most about his own habits of writing in the essays titled “Of Presumption”, “Of Giving the Lie”, “Of Vanity”, and “Of Repentance”.

But the message of this latter essay is, quite simply, that non, je ne regrette rien , as a more recent French icon sang:

Were I to live my life over again, I should live it just as I have lived it; I neither complain of the past, nor do I fear the future; and if I am not much deceived, I am the same within that I am without … I have seen the grass, the blossom, and the fruit, and now see the withering; happily, however, because naturally.

Montaigne’s persistence in assembling his extraordinary dossier of stories, arguments, asides and observations on nearly everything under the sun (from how to parley with an enemy to whether women should be so demure in matters of sex , has been celebrated by admirers in nearly every generation.

Within a decade of his death, his Essays had left their mark on Bacon and Shakespeare. He was a hero to the enlighteners Montesquieu and Diderot. Voltaire celebrated Montaigne - a man educated only by his own reading, his father and his childhood tutors – as “the least methodical of all philosophers, but the wisest and most amiable”. Nietzsche claimed that the very existence of Montaigne’s Essays added to the joy of living in this world.

More recently, Sarah Bakewell’s charming engagement with Montaigne, How to Live or a Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer (2010) made the best-sellers’ lists. Even today’s initiatives in teaching philosophy in schools can look back to Montaigne (and his “ On the Education of Children ”) as a patron saint or sage .

So what are these Essays, which Montaigne protested were indistinguishable from their author? (“ My book and I go hand in hand together ”).

It’s a good question.

Anyone who tries to read the Essays systematically soon finds themselves overwhelmed by the sheer wealth of examples, anecdotes, digressions and curios Montaigne assembles for our delectation, often without more than the hint of a reason why.

To open the book is to venture into a world in which fortune consistently defies expectations; our senses are as uncertain as our understanding is prone to error; opposites turn out very often to be conjoined (“ the most universal quality is diversity ”); even vice can lead to virtue. Many titles seem to have no direct relation to their contents. Nearly everything our author says in one place is qualified, if not overturned, elsewhere.

Without pretending to untangle all of the knots of this “ book with a wild and desultory plan ”, let me tug here on a couple of Montaigne’s threads to invite and assist new readers to find their own way.

Philosophy (and writing) as a way of life

Some scholars argued that Montaigne began writing his essays as a want-to-be Stoic , hardening himself against the horrors of the French civil and religious wars , and his grief at the loss of his best friend Étienne de La Boétie through dysentery.

Certainly, for Montaigne, as for ancient thinkers led by his favourites, Plutarch and the Roman Stoic Seneca, philosophy was not solely about constructing theoretical systems, writing books and articles. It was what one more recent admirer of Montaigne has called “ a way of life ”.

Montaigne has little time for forms of pedantry that value learning as a means to insulate scholars from the world, rather than opening out onto it. He writes :

Either our reason mocks us or it ought to have no other aim but our contentment.

We are great fools . ‘He has passed over his life in idleness,’ we say: ‘I have done nothing today.’ What? have you not lived? that is not only the fundamental, but the most illustrious of all your occupations.

One feature of the Essays is, accordingly, Montaigne’s fascination with the daily doings of men like Socrates and Cato the Younger ; two of those figures revered amongst the ancients as wise men or “ sages ”.

Their wisdom, he suggests , was chiefly evident in the lives they led (neither wrote a thing). In particular, it was proven by the nobility each showed in facing their deaths. Socrates consented serenely to taking hemlock, having been sentenced unjustly to death by the Athenians. Cato stabbed himself to death after having meditated upon Socrates’ example , in order not to cede to Julius Caesar’s coup d’état .

To achieve such “philosophic” constancy, Montaigne saw, requires a good deal more than book learning . Indeed, everything about our passions and, above all, our imagination , speaks against achieving that perfect tranquillity the classical thinkers saw as the highest philosophical goal.

We discharge our hopes and fears, very often, on the wrong objects, Montaigne notes , in an observation that anticipates the thinking of Freud and modern psychology. Always, these emotions dwell on things we cannot presently change. Sometimes, they inhibit our ability to see and deal in a supple way with the changing demands of life.

Philosophy, in this classical view, involves a retraining of our ways of thinking, seeing and being in the world. Montaigne’s earlier essay “ To philosophise is to learn how to die ” is perhaps the clearest exemplar of his indebtedness to this ancient idea of philosophy.

Yet there is a strong sense in which all of the Essays are a form of what one 20th century author has dubbed “ self-writing ”: an ethical exercise to “strengthen and enlighten” Montaigne’s own judgement, as much as that of we readers:

And though nobody should read me, have I wasted time in entertaining myself so many idle hours in so pleasing and useful thoughts? … I have no more made my book than my book has made me: it is a book consubstantial with the author, of a peculiar design, a parcel of my life …

As for the seeming disorder of the product, and Montaigne’s frequent claims that he is playing the fool , this is arguably one more feature of the Essays that reflects his Socratic irony. Montaigne wants to leave us with some work to do and scope to find our own paths through the labyrinth of his thoughts, or alternatively, to bobble about on their diverting surfaces .

A free-thinking sceptic

Yet Montaigne’s Essays, for all of their classicism and their idiosyncracies, are rightly numbered as one of the founding texts of modern thought . Their author keeps his own prerogatives, even as he bows deferentially before the altars of ancient heroes like Socrates, Cato, Alexander the Great or the Theban general Epaminondas .

There is a good deal of the Christian, Augustinian legacy in Montaigne’s makeup. And of all the philosophers, he most frequently echoes ancient sceptics like Pyrrho or Carneades who argued that we can know almost nothing with certainty. This is especially true concerning the “ultimate questions” the Catholics and Huguenots of Montaigne’s day were bloodily contesting.

Writing in a time of cruel sectarian violence , Montaigne is unconvinced by the ageless claim that having a dogmatic faith is necessary or especially effective in assisting people to love their neighbours :

Between ourselves, I have ever observed supercelestial opinions and subterranean manners to be of singular accord …

This scepticism applies as much to the pagan ideal of a perfected philosophical sage as it does to theological speculations.

Socrates’ constancy before death, Montaigne concludes, was simply too demanding for most people, almost superhuman . As for Cato’s proud suicide, Montaigne takes liberty to doubt whether it was as much the product of Stoic tranquility, as of a singular turn of mind that could take pleasure in such extreme virtue .

Indeed when it comes to his essays “ Of Moderation ” or “ Of Virtue ”, Montaigne quietly breaks the ancient mold. Instead of celebrating the feats of the world’s Catos or Alexanders, here he lists example after example of people moved by their sense of transcendent self-righteousness to acts of murderous or suicidal excess.

Even virtue can become vicious, these essays imply, unless we know how to moderate our own presumptions.

Of cannibals and cruelties

If there is one form of argument Montaigne uses most often, it is the sceptical argument drawing on the disagreement amongst even the wisest authorities.

If human beings could know if, say, the soul was immortal, with or without the body, or dissolved when we die … then the wisest people would all have come to the same conclusions by now, the argument goes. Yet even the “most knowing” authorities disagree about such things, Montaigne delights in showing us .

The existence of such “ an infinite confusion ” of opinions and customs ceases to be the problem, for Montaigne. It points the way to a new kind of solution, and could in fact enlighten us.

Documenting such manifold differences between customs and opinions is, for him, an education in humility :

Manners and opinions contrary to mine do not so much displease as instruct me; nor so much make me proud as they humble me.

His essay “ Of Cannibals ” for instance, presents all of the different aspects of American Indian culture, as known to Montaigne through travellers’ reports then filtering back into Europe. For the most part, he finds these “savages’” society ethically equal, if not far superior, to that of war-torn France’s — a perspective that Voltaire and Rousseau would echo nearly 200 years later.

We are horrified at the prospect of eating our ancestors. Yet Montaigne imagines that from the Indians’ perspective, Western practices of cremating our deceased, or burying their bodies to be devoured by the worms must seem every bit as callous.

And while we are at it, Montaigne adds that consuming people after they are dead seems a good deal less cruel and inhumane than torturing folk we don’t even know are guilty of any crime whilst they are still alive …

A gay and sociable wisdom

“So what is left then?”, the reader might ask, as Montaigne undermines one presumption after another, and piles up exceptions like they had become the only rule.

A very great deal , is the answer. With metaphysics, theology, and the feats of godlike sages all under a “ suspension of judgment ”, we become witnesses as we read the Essays to a key document in the modern revaluation and valorization of everyday life.

There is, for instance, Montaigne’s scandalously demotic habit of interlacing words, stories and actions from his neighbours, the local peasants (and peasant women) with examples from the greats of Christian and pagan history. As he writes :

I have known in my time a hundred artisans, a hundred labourers, wiser and more happy than the rectors of the university, and whom I had much rather have resembled.

By the end of the Essays, Montaigne has begun openly to suggest that, if tranquillity, constancy, bravery, and honour are the goals the wise hold up for us, they can all be seen in much greater abundance amongst the salt of the earth than amongst the rich and famous:

I propose a life ordinary and without lustre: ‘tis all one … To enter a breach, conduct an embassy, govern a people, are actions of renown; to … laugh, sell, pay, love, hate, and gently and justly converse with our own families and with ourselves … not to give our selves the lie, that is rarer, more difficult and less remarkable …

And so we arrive with these last Essays at a sentiment better known today from another philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche, the author of A Gay Science (1882) .

Montaigne’s closing essays repeat the avowal that: “ I love a gay and civil wisdom … .” But in contrast to his later Germanic admirer, the music here is less Wagner or Beethoven than it is Mozart (as it were), and Montaigne’s spirit much less agonised than gently serene.

It was Voltaire, again, who said that life is a tragedy for those who feel, and a comedy for those who think. Montaigne adopts and admires the comic perspective . As he writes in “Of Experience”:

It is not of much use to go upon stilts , for, when upon stilts, we must still walk with our legs; and when seated upon the most elevated throne in the world, we are still perched on our own bums.

- Classic literature

- Michel de Montaigne

Senior Lecturer - Earth System Science

Operations Coordinator

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

The Essays of Montaigne

First published in 1686; from the edition revised and edited in 1877 by William Carew Hazlitt

Table of Contents

- The Letters of Montaigne

- Chapter XXXIV. Means to carry on a war according to Julius Caesar.

- Chapter I. Of Profit and Honesty.

- Chapter II. Of Repentance.

- Chapter III. Of Three Commerces.

- Chapter IV. Of Diversion.

- Chapter V. Upon Some verses of Virgil.

- Chapter VI. Of Coaches.

- Chapter VII. Of the Inconvenience of Greatness.

- Chapter VIII. Of the Art of Conference.

- Chapter IX. Of Vanity.

- Chapter X. Of Managing the Will.

- Chapter XI. Of Cripples.

- Chapter XII. Of Physiognomy.

- Chapter XIII. Of Experience.

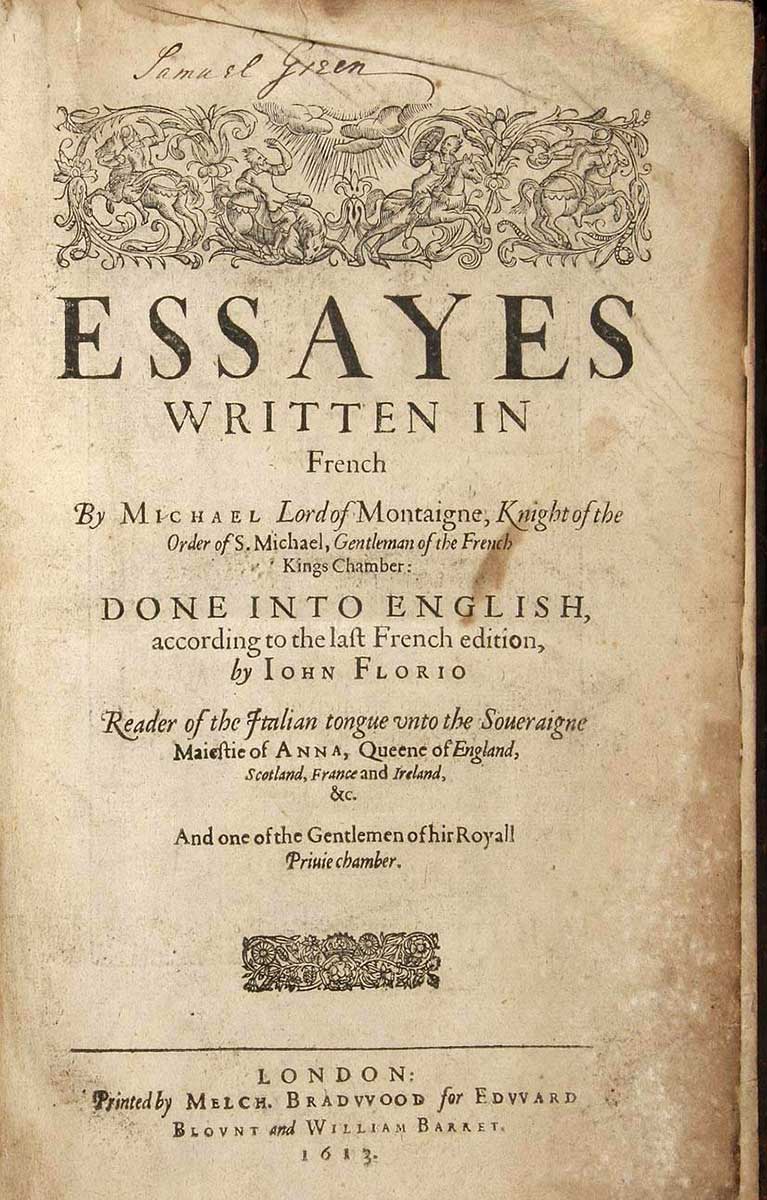

- ↑ Translator John Florio

- French essays

- Works originally in French

- Headers applying DefaultSort key

Navigation menu

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

François Quesnel, “Montaigne”, c. 1590, drawing reprinted with permission from the Montaigne Studies website

Michel de Montaigne

The question is not who will hit the ring, but who will make the best runs at it.

Given the huge breadth of his readings, Montaigne could have been ranked among the most erudite humanists of the XVI th century. But in the Essays , his aim is above all to exercise his own judgment properly. Readers who might want to convict him of ignorance would find nothing to hold against him, he said, for he was exerting his natural capacities, not borrowed ones. He thought that too much knowledge could prove a burden, preferring to exert his “natural judgment” to displaying his erudition.

3. A Philosophy of Free Judgment

4. montaigne’s scepticism, 5. montaigne and relativism, 6. montaigne’s legacy from charron to hobbes, 7. conclusion, translations in english, secondary sources, translations, related entries.

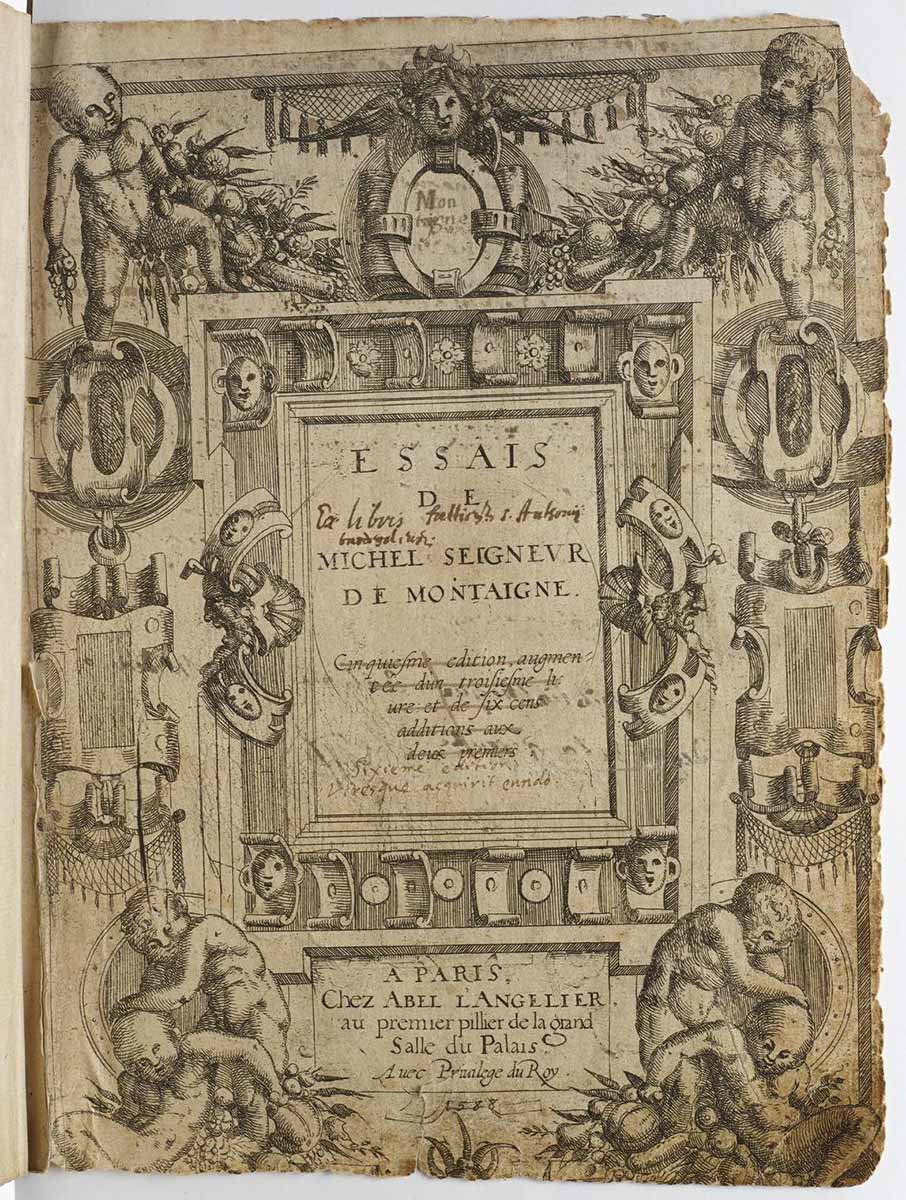

Montaigne (1533–1592) came from a rich bourgeois family that acquired nobility after his father fought in Italy in the army of King Francis I of France; he came back with the firm intention of bringing refined Italian culture to France. He decorated his Périgord castle in the style of an ancient Roman villa. He also decided that his son would not learn Latin in school. He arranged instead for a German preceptor and the household to speak to him exclusively in Latin at home. So the young Montaigne grew up speaking Latin and reading Vergil, Ovid, and Horace on his own. At the age of six, he was sent to board at the Collège de Guyenne in Bordeaux, which he later praised as the best humanist college in France, though he found fault with humanist colleges in general. Where Montaigne later studied law, or, indeed, whether he ever studied law at all is not clear. The only thing we know with certainty is that his father bought him an office in the Court of Périgueux. He then met Etienne de La Boëtie with whom he formed an intimate friendship and whose death some years later, in 1563, left him deeply distraught. Tired of active life, he retired at the age of only 37 to his father’s castle. In the same year, 1571, he was nominated Gentleman of King Charles IX’s Ordinary Chamber, and soon thereafter, also of Henri de Navarre’s Chamber. He received the decoration of the Order of Saint-Michel, a distinction all the more exceptional as Montaigne’s lineage was from recent nobility. On the title page of the first edition (1580) of the Essays , we read: “Essais de Messire Michel Seigneur de Montaigne, Chevalier de l’ordre du Roy, & Gentilhomme ordinaire de sa chambre.” Initially keen to show off his titles and, thus, his social standing, Montaigne had the honorifics removed in the second edition (1582).

Replicating Petrarca’s choice in De vita solitaria , Montaigne chose to dedicate himself to the Muses. In his library, which was quite large for the period, he had wisdom formulas carved on the wooden beams. They were drawn from, amongst others, Ecclesiastes , Sextus Empiricus, Lucretius, and other classical authors, whom he read intensively. To escape fits of melancholy, he began to commit his thoughts to paper. In 1580, he undertook a journey to Italy, whose main goal was to cure the pain of his kidney stones at thermal resorts. The journey is related in part by a secretary, in part by Montaigne himself, in a manuscript that was only discovered during the XVIII th century, given the title The Journal of the Journey to Italy , and forgotten soon after. While Montaigne was taking the baths near Pisa, he learnt of his election as Mayor of Bordeaux. He was first tempted to refuse out of modesty, but eventually accepted (he even received a letter from the King urging him to take the post) and was later re-elected. In his second term he came under criticism for having abandoned the town during the great plague in an attempt to protect himself and his family. His time in office was dimmed by the wars of religion between Catholics and Protestants. Several members of his family converted to Protestantism, but Montaigne himself remained a Catholic.

Montaigne wrote three books of Essays . (“Essay” was an original name for this kind of work; it became an appreciated genre soon after.) Three main editions are recognized: 1580 (at this stage, only the first two books were written), 1588, and 1595. The last edition, which could not be supervised by Montaigne himself, was edited from the manuscript by his adoptive daughter Marie de Gournay. Till the end of the XIX th century, the copy text for all new editions was that of 1595; Fortunat Strowski and shortly after him Pierre Villey dismissed it in favor of the “Bordeaux copy”, a text of the 1588 edition supplemented by manuscript additions. [ 1 ] Montaigne enriched his text continuously; he preferred to add for the sake of diversity, rather than to correct. [ 2 ] The unity of the work and the order of every single chapter remain problematic. We are unable to detect obvious links from one chapter to the next: in the first book, Montaigne jumps from “Idleness” (I,8) to “Liars” (I,9), then from “Prompt or slow speech” (I,10) to “Prognostications” (I,11). The random aspect of the work, acknowledged by the author himself, has been a challenge for commentators ever since. Part of the brilliance of the Essays lies in this very ability to elicit various forms of explanatory coherence whilst at the same time defying them. The work is so rich and flexible that it accommodates virtually any academic trend. Yet, it is also so resistant to interpretation that it reveals the limits of each interpretation.

Critical studies of the Essays have, until recently, been mainly of a literary nature. However, to consider Montaigne as a writer rather than as a philosopher can be a way of ignoring a disturbing thinker. Indeed, he shook some fundamental aspects of Western thought, such as the superiority we assign to man over animals, [ 3 ] to European civilization over “Barbarians”, [ 4 ] or to reason as an alleged universal standard. A tradition rooted in the 19th century tends to relegate his work to the status of literary impressionism or to the expression of a frivolous subjectivity. To do him justice, one needs to bear in mind the inseparable unity of thought and style in his work. Montaigne’s repeated revisions of his text, as modern editions show with the three letters A, B, C, standing for the three main editions, mirror the relationship between the activity of his thought and the Essays as a work in progress. The Essays display both the laboriousness and the delight of thinking.

In Montaigne we have a writer whose work is deeply infused by philosophical thought. One verse out of sixteen in Lucretius’ De natura rerum is quoted in the Essays . [ 5 ] If it is true, as Edmund Husserl said, that philosophy is a shared endeavor, Montaigne is perhaps the most exemplary of philosophers since his work extensively borrows and quotes from others. Montaigne managed to internalize a huge breadth of reading, so that his erudition does not appear as such. He created a most singular work, yet one that remains deeply rooted in the community of poets, historians, and philosophers. His decision to use only his own judgment in dealing with all sorts of matters, his resolutely distant attitude towards memory and knowledge, his warning that we should not mix God or transcendent principles with the human world, are some of the key elements that characterize Montaigne’s position. As a humanist, he considered that one has to assimilate the classics, but above all to display virtue, “according to the opinion of Plato, who says that steadfastness, faith, and sincerity are real philosophy, and the other sciences which aim at other things are only powder and rouge.” [ 6 ]

Montaigne rejects the theoretical or speculative way of philosophizing that prevailed under the Scholastics ever since the Middle Ages. According to him, science does not exist, but only a general belief in science. Petrarch had already criticized the Scholastics for worshiping Aristotle as their God. Siding with the humanists, Montaigne develops a sharp criticism of science “à la mode des Geométriens”, [ 7 ] the mos geometricus deemed to be the most rigorous. It is merely “a practice and business of science”, [ 8 ] he says, which is restricted to the University and essentially carried out between masters and their disciples. The main problem of this kind of science is that it makes us spend our time justifying as rational the beliefs we inherit, instead of calling into question their foundations; it makes us label fashionable opinions as truth, instead of gauging their strength. Whereas science should be a free inquiry, it consists only in gibberish discussions on how we should read Aristotle or Galen. [ 9 ] Critical judgment is systematically silenced. Montaigne demands a thought process that would not be tied down by any doctrinaire principle, a thought process that would lead to free enquiry.

If we trace back the birth of modern science, we find that Montaigne as a philosopher was ahead of his time. In 1543, Copernicus put the earth in motion, depriving man of his cosmological centrality. Yet he nevertheless changed little in the medieval conception of the world as a sphere. The Copernican world became an “open” world only with Thomas Digges (1576) although his sky was still situated in space, inhabited by gods and angels. [ 10 ] One has to wait for Giordano Bruno to find the first representative of the modern conception of an infinite universe (1584). But whether Bruno is a modern mind remains controversial (the planets are still animals, etc). Montaigne, on the contrary, is entirely free from the medieval conception of the spheres. He owes his cosmological freedom to his deep interest in ancient philosophers, to Lucretius in particular. In the longest chapter of the Essays , the “Apologie de Raymond Sebond”, Montaigne conjures up many opinions, regarding the nature of the cosmos, or the nature of the soul. He weighs the Epicureans’ opinion that several worlds exist, against that of the unicity of the world put forth by both Aristotle and Aquinas. He comes out in favor of the former, without ranking his own evaluation as a truth.

As a humanist, Montaigne conceived of philosophy as morals. In the chapter “On the education of children”, [ 11 ] education is identified with philosophy, this being understood as the formation of judgment and manners in everyday life: “for philosophy, which, as the molder of judgment and conduct, will be his principal lesson, has the privilege of being everywhere at home”. [ 12 ] Philosophy, which consists essentially in the use of judgment, is significant to the very ordinary, varied and “undulating” [ 13 ] process of life. In fact, under the guise of innocuous anecdotes, Montaigne achieved the humanist revolution in philosophy. He moved from a conception of philosophy conceived of as theoretical science, to a philosophy conceived of as the practice of free judgment. Lamenting that “philosophy, even with people of understanding, should be an empty and fantastic name, a thing of no use and no value”, [ 14 ] he asserted that philosophy should be the most cheerful activity. He practised philosophy by setting his judgment to trial, in order to become aware of its weaknesses, but also to get to know its strength. “Every movement reveals us”, [ 15 ] but our judgments do so the best. At the beginning of the past century, one of Montaigne’s greatest commentators, Pierre Villey, developed the idea that Montaigne truly became himself through writing. This idea remains more or less true, in spite of its obvious link with late romanticist psychology. The Essays remain an exceptional historical testimony of the progress of privacy and individualism, a blossoming of subjectivity, an attainment of personal maturity that will be copied, but maybe never matched since. It seems that Montaigne, who dedicated himself to freedom of the mind and peacefulness of the soul, did not have any other aim through writing than cultivating and educating himself. Since philosophy had failed to determine a secure path towards happiness, he committed each individual to do so in his own way. [ 16 ]

Montaigne wants to escape the stifling of thought by knowledge, a wide-spread phenomenon which he called “pedantism”, [ 17 ] an idea that he may have gleaned from the tarnishing of professors by the Commedia dell’arte . He praises one of the most famous professors of the day, Adrianus Turnebus, for having combined robust judgment with massive erudition. We have to moderate our thirst for knowledge, just as we do our appetite for pleasure. Siding here with Callicles against Plato, Montaigne asserts that a gentleman should not dedicate himself entirely to philosophy. [ 18 ] Practised with restraint, it proves useful, whereas in excess it leads to eccentricity and insociability. [ 19 ] Reflecting on the education of the children of the aristocracy (chapter I, 26, is dedicated to the countess Diane de Foix, who was then pregnant), Montaigne departs significantly from a traditional humanist education, the very one he himself received. Instead of focusing on the ways and means of making the teaching of Latin more effective, as pedagogues in the wake of Erasmus usually did, Montaigne stresses the need for action and playful activities. The child will conform early to social and political customs, but without servility. The use of judgment in every circumstance, as a warrant for practical intelligence and personal freedom, has to remain at the core of education. He transfers the major responsibility of education from the school to everyday life: “Wonderful brilliance may be gained for human judgment by getting to know men”. [ 20 ] The priority given to the formation of judgment and character strongly opposes the craving for a powerful memory during his time. He reserves for himself the freedom to pick up bits of knowledge here and there, displaying the “nonchalance” or unconcern intellectually, much in the same way that Castiglione’s courtier would use sprezzatura in social relationships. Although Montaigne presents this nonchalance as essential to his nature, his position is not innocent: it allows him to take on the voice now of a Stoic, and then of a Sceptic, now of an Epicurean and then of a Christian. Although his views are never fully original, they always bear his unmistakable mark. Montaigne’s thought, which is often rated as modern in so many aspects, remains deeply rooted in the classical tradition. Montaigne navigates easily through heaps of classical knowledge, proposing remarkable literary and philosophical innovations along the way.

Montaigne begins his project to know man by noticing that the same human behavior can have opposite effects, or that even opposite conducts can have the same effects: “by diverse means we arrive at the same end”. [ 21 ] Human life cannot be turned into an object of rational theory. Human conduct does not obey universal rules, but a great diversity of rules, among which the most accurate still fall short of the intended mark. “Human reason is a tincture infused in about equal strength in all our opinions and ways, whatever their form: infinite in substance, infinite in diversity” [ 22 ] says the chapter on custom. By focusing on anecdotal experience, Montaigne comes thus to write “the masterpiece of modern moral science”, according to the great commentator Hugo Friedrich. He gives up the moral ambition of telling how men should live, in order to arrive at a non-prejudiced mind for knowing man as he is. “Others form man, I tell of him”. [ 23 ] Man is ever since “without a definition”, as philosopher Marcel Conche commented. [ 24 ] In the chapter “Apologie de Raimond Sebond”, Montaigne draws from classical and Renaissance knowledge in order to remind us that, in some parts of the world, we find men that bear little resemblance to us. Our experience of man and things should not be perceived as limited by our present standards of judgment. It is a sort of madness when we settle limits for the possible and the impossible. [ 25 ]

Philosophy has failed to secure man a determined idea of his place in the world, or of his nature. Metaphysical or psychological opinions, indeed far too numerous, come as a burden more than as a help. Montaigne pursues his quest for knowledge through experience; the meaning of concepts is not set down by means of a definition, it is related to common language or to historical examples. One of the essential elements of experience is the ability to reflect on one’s actions and thoughts. Montaigne is engaging in a case-by-case gnôti seauton , “know thyself”: although truth in general is not truly an appropriate object for human faculties, we can reflect on our experience. What counts is not the fact that we eventually know the truth or not, but rather the way in which we seek it. “The question is not who will hit the ring, but who will make the best runs at it.” [ 26 ] The aim is to properly exercise our judgment.

Montaigne’s thinking baffles our most common categories. The vision of an ever-changing world that he developed threatens the being of all things. “We have no communication with being”. [ 27 ] We wrongly take that which appears for that which is, and we indulge in a dogmatic, deceptive language that is cut off from an ever-changing reality. We ought to be more careful with our use of language. Montaigne would prefer that children be taught other ways of speaking, more appropriate to the nature of human inquiry, such as “What does that mean ?”, “I do not understand it”, “This might be”, “Is it true?” [ 28 ] Montaigne himself is fond of “these formulas that soften the boldness of our propositions”: “perhaps”, “to some extent”, “they say”, “I think”, [ 29 ] and the like. Criticism on theory and dogmatism permeates for example his reflexion on politics. Because social order is too complicated to be mastered by individual reason, he deems conservatism as the wisest stance. [ 30 ] This policy is grounded on the general evaluation that change is usually more damaging than the conservation of social institutions. Nevertheless, there may be certain circumstances that advocate change as a better solution, as history sometimes showed. Reason being then unable to decide a priori , judgment must come into play and alternate its views to find the best option.

With Cornelius Agrippa, Henri Estienne or Francisco Sanchez, among others, Montaigne has largely contributed to the rebirth of scepticism during the XVI th century. His literary encounter with Sextus produced a decisive shock: around 1576, when Montaigne had his own personal medal coined, he had it engraved with his age, with “ Epecho ” , “I abstain” in Greek, and another Sceptic motto in French: “ Que sais-je ?”: what do I know ? At this period in his life, Montaigne is thought to have undergone a “sceptical crisis”, as Pierre Villey famously commented. In fact, this interpretation dates back to Pascal, for whom scepticism could only be a sort of momentary frenzy. [ 31 ] The “Apologie de Raimond Sebond”, the longest chapter of the Essays , bears the sign of intellectual despair that Montaigne manages to shake off elsewhere. But another interpretation of scepticism formulates it as a strategy used to confront “fideism”: because reason is unable to demonstrate religious dogmas, we must rely on spiritual revelation and faith. The paradigm of fideism, a word which Montaigne does not use, has been delivered by Richard Popkin in History of Scepticism [ 32 ] . Montaigne appears here as a founding father of the Counter Reformation, being the leader of the “Nouveaux Pyrrhoniens”, for whom scepticism is used as a means to an end, that is, to neutralize the grip that philosophy once had on religion.

Commentators now agree upon the fact that Montaigne largely transformed the type of scepticism he borrowed from Sextus. The two sides of the scale are never perfectly balanced, since reason always tips the scale in favor of the present at hand. This imbalance undermines the key mechanism of isosthenia , the equality of strength of two opposing arguments. Since the suspension of judgment cannot occur “casually”, as Sextus Empiricus would like it to, judgment must abstain from giving its assent. In fact, the sources of Montaigne’s scepticism are much wider: his child readings of Ovid’s Metamorphosis , which gave him a deep awareness of change, the in utramque partem academic debate which he practised at the Collège de Guyenne (a pro and contra discussion inherited from Aristotle and Cicero), and the humanist philosophy of action, dealing with the uncertainty of human affairs, shaped his mind early on. Through them, he learned repeatedly that rational appearances are deceptive. In most of the chapters of the Essays , Montaigne now and then reverses his judgment: these sudden shifts of perspective are designed to escape adherence, and to tackle the matter from another point of view. [ 33 ] The Essays mirror a discreet conduct of judgment, in keeping with the formula iudicio alternante , which we still find engraved today on the beams of the Périgord castle’s library. The aim is not to ruin arguments by opposing them, as it is the case in the Pyrrhonian “antilogy”, but rather to counterbalance a single opinion by taking into account other opinions. In order to work, each scale of judgment has to be laden. If we take morals, for example, Montaigne refers to varied moral authorities, one of them being custom and the other reason. Against every form of dogmatism, Montaigne returns moral life to its original diversity and inherent uneasiness. Through philosophy, he seeks full accordance with the diversity of life: “As for me, I love life and cultivate it as God has been pleased to grant it to us”. [ 34 ]

We find two readings of Montaigne as a Sceptic. The first one concentrates on the polemical, negative arguments drawn from Sextus Empiricus, at the end of the “Apology”. This hard-line scepticism draws the picture of man as “humiliated”. [ 35 ] Its aim is essentially to fight the pretensions of reason and to annihilate human knowledge. “Truth”, “being” and “justice” are equally dismissed as unattainable. Doubt foreshadows here Descartes’ Meditations , on the problem of the reality of the outside world. Dismissing the objective value of one’s representations, Montaigne would have created the long-lasting problem of “solipsism”. We notice, nevertheless, that he does not question the reality of things — except occasionally at the very end of the “Apology” — but the value of opinions and men. The second reading of his scepticism puts forth that Cicero’s probabilism is of far greater significance in shaping the sceptical content of the Essays . After the 1570s, Montaigne no longer read Sextus; additions show, however, that he took up a more and more extensive reading of Cicero’s philosophical writings. We assume that, in his early search for polemical arguments against rationalism during the 1570s, Montaigne borrowed much from Sextus, but as he got tired of the sceptical machinery, and understood scepticism rather as an ethics of judgment, he went back to Cicero. [ 36 ] The paramount importance of the Academica for XVI th century thought has been underlined by Charles B. Schmitt. [ 37 ] In the free enquiry, which Cicero engaged throughout the varied doctrines, the humanists found an ideal mirror of their own relationship with the Classics. “The Academy, of which I am a follower, gives me the opportunity to hold an opinion as if it were ours, as soon as it shows itself to be highly probable” [ 38 ] , wrote Cicero in the De Officiis . Reading Seneca, Montaigne will think as if he were a member of the Stoa; then changing for Lucretius, he will think as if he had become an Epicurean, and so on. Doctrines or opinions, beside historical stuff and personal experiences, make up the nourishment of judgment. Montaigne assimilates opinions, according to what appears to him as true, without taking it to be absolutely true. He insists on the dialogical nature of thought, referring to Socrates’ way of keeping the discussion going: “The leader of Plato’s dialogues, Socrates, is always asking questions and stirring up discussion, never concluding, never satisfying (…).” [ 39 ] Judgment has to determine the most convincing position, or at least to determine the strengths and weaknesses of each position. The simple dismissal of truth would be too dogmatic a position; but if absolute truth is lacking, we still have the possibility to balance opinions. We have resources enough, to evaluate the various authorities that we have to deal with in ordinary life.

The original failure of commentators was perhaps in labelling Montaigne’s thought as “sceptic” without reflecting on the proper meaning of the essay. Montaigne’s exercise of judgment is an exercise of “natural judgment”, which means that judgment does not need any principle or any rule as a presupposition. In this way, many aspects of Montaigne’s thinking can be considered as sceptical, although they were not used for the sake of scepticism. For example, when Montaigne sets down the exercise of doubt as a good start in education, he understands doubt as part of the process of the formation of judgment. This process should lead to wisdom, characterized as “always joyful”. [ 40 ] Montaigne’s scepticism is not a desperate one. On the contrary, it offers the reader a sort of jubilation which relies on the modest but effective pleasure in dismissing knowledge, thus making room for the exercise of one’s natural faculties.

Renaissance thinkers strongly felt the necessity to revise their discourse on man. But no one accentuated this necessity more than Montaigne: what he was looking for, when reading historians or travellers such as Lopez de Gomara’s History of Indies , was the utmost variety of beliefs and customs that would enrich his image of man. Neither the Hellenistic Sage, nor the Christian Saint, nor the Renaissance Scholar, are unquestioned models in the Essays . Instead, Montaigne is considering real men, who are the product of customs. “Here they live on human flesh; there it is an act of piety to kill one’s father at a certain age (…).” [ 41 ] The importance of custom plays a polemical part: alongside with scepticism, the strength of imagination (chapter I,21) or Fortune (chapters I,1, I,24, etc.), it contributes to the devaluation of reason and will. It is bound to destroy our spontaneous confidence that we do know the truth, and that we live according to justice. During the XVI th century, the jurists of the “French school of law” showed that the law is tied up with historical determinations. [ 42 ] In chapter I,23, “On custom”, Montaigne seems to extrapolate on this idea : our opinions and conducts being everywhere the product of custom, references to universal “reason”, “truth”, or “justice” are to be dismissed as illusions. Pierre Villey was the first to use the terms “relativity” and “relativism”, which proved to be useful tools when commenting on the fact that Montaigne acknowledges that no universal reason presides over the birth of our beliefs. [ 43 ] The notion of absolute truth, applied to human matters, vitiates the understanding and wreaks havoc in society. Upon further reflexion, contingent customs impact everything: “in short, to my way of thinking, there is nothing that custom will not or cannot do”. [ 44 ] Montaigne calls it “Circe’s drink”. [ 45 ] Custom is a sort of witch, whose spell, among other effects, casts moral illusion. “The laws of conscience, which we say are born from nature, are born of custom. Each man, holding in inward veneration the opinions and the behavior approved and accepted around him, cannot break loose from them without remorse, or apply himself to them without self-satisfaction.” [ 46 ] The power of custom, indeed, not only guides man in his behavior, but also persuades him of its legitimacy. What is crime for one person will appear normal to another. In the XVII th century, Blaise Pascal will use this argument when challenging the pretension of philosophers of knowing truth. One century later, David Hume will lay stress on the fact that the power of custom is all the stronger, specifically because we are not aware of it. What are we supposed to do, then, if our reason is so flexible that it “changes with two degrees of elevation towards the pole”, as Pascal puts it? [ 47 ] For the Jansenist thinker, only one alternative exists, faith in Jesus Christ. However, it is more complicated in the case of Montaigne. Getting to know all sorts of customs, through his readings or travels, he makes an exemplary effort to open his mind. “We are all huddled and concentrated in ourselves, and our vision is reduced to the length of our nose.” [ 48 ] Custom’s grip is so strong that it is dubious as to whether we are in a position to become aware of it and shake off its power.

Montaigne was hailed by Claude Lévi-Strauss as the progenitor of the human sciences, and the pioneer of cultural relativism. [ 49 ] However, Montaigne has not been willing to indulge entirely in relativism. Judgment is at first sight unable to stop the relativistic discourse, but it is not left without remedy when facing the power of custom. Exercise of thought is the first counterweight we can make use of, for example when criticizing an existing law. Customs are not almighty, since their authority can be reflected upon, evaluated or challenged by individual judgment. The comparative method can also be applied to the freeing of judgment: although lacking a universal standard, we can nevertheless stand back from particular customs, by the mere fact of comparing them. Montaigne thus compares heating or circulating means between people. In a more tragical way, he denounces the fanaticism and the cruelty displayed by Christians against one another, during the civil wars in France, through a comparison with cannibalism: “I think there is more barbarity in eating a man alive than in eating him dead, and in tearing by tortures and the rack a body still full of feeling (…).” [ 50 ] The meaning of the word “barbarity” is not merely relative to a culture or a point of view, since there are degrees of barbarity. Passing a judgment on cannibals, Montaigne also says: “So we may well call these people barbarians, in respect to the rules of reason, but not in respect to ourselves, who surpass them in every kind of barbarity (…).” [ 51 ] Judgment is still endowed with the possibility of postulating universal standards, such as “reason” or “nature”, which help when evaluating actions and behaviors. Although Montaigne maintains in the “Apologie” that true reason and true justice are only known by God, he asserts in other chapters that these standards are somehow accessible to man, since they allow judgment to consider customs as particular and contingent rules. [ 52 ] In order to criticize the changeable and the relative, we must suppose that our judgment is still able to “bring things back to truth and reason”. [ 53 ] Man is everywhere enslaved by custom, but this does not mean that we should accept the numbing of our mind. Montaigne elaborates a pedagogy, which rests on the practice of judgment itself. The task of the pupil is not to repeat what the master said, but, on a given subject of problem, to confront his judgment with the master’s one. Moreover, relativistic readings of the Essays are forced to ignore certain passages that carry a more rationalistic tone. “The violent detriment inflicted by custom” (I,23) is certainly not a praise of custom, but an invitation to escape it. In the same way that Circe’s potion has changed men into pigs, custom turns their intelligence into stupidity. In the toughest cases, Montaigne’s critical use of judgment aims at giving “a good whiplash to the ordinary stupidity of judgment.” [ 54 ] In many other places, Montaigne boasts of himself being able to resist vulgar opinion. Independence of thinking, alongside with clear-mindedness and good faith, are the first virtues a young gentleman should acquire.

Pierre Charron was Montaigne’s friend and official heir. In De la sagesse (1601 and 1604), he re-organized many of his master’s ideas, setting aside the most disturbing ones. His work is now usually dismissed as a dogmatic misrepresentation of Montaigne’s thought. Nevertheless, his book was given priority over the Essays themselves during the whole XVII th century, especially after Malebranche’s critics conspired to have the Essays included in the Roman Index of 1677. Montaigne’s historical influence must be reckoned through the lens of this mediation. Moreover, Charron’s reading is not simply faulty. According to him, wisdom relies on the readiness of judgment to revise itself towards a more favorable outcome: [ 55 ] this idea is one of the most remarkable readings of the Essays in the early history of their reception.

The critical conception of the essay was taken up by the English scientist and philosopher Francis Bacon, who considered his own Essays as “fragments of [his] conceits” and “dispersed meditations”, aiming to stimulate the reader’s appetite for thinking and knowledge rather than satisfying it with expositions of dogmas and methods. [ 56 ] Even in his more scientific works, such as The Advancement of Learning , Bacon’s writing was inconclusive. He posited that this open and fragmentary style was the best way to inspire further thought and examination: “Aphorisms, representing a knowledge broken, do invite men to inquire further”. [ 57 ] Bacon’s reflections allow us to appreciate the scientific value of Montaigne’s Essays, insofar as they are incomplete works, always calling for subsequent reflections by the author and the reader, thus inspiring and promoting the development of ideas and the advancement of research.

The influence Montaigne had on Descartes has been commented upon by many critics, at least from the XIX th century on, within the context of the birth of modern science. As a sceptic, calling into question the natural link between mind and things, Montaigne would have won his position in the modern philosophical landscape. The scepticism in the “Apologie” is, no doubt, a main source of “solipsism”, but Descartes cannot be called a disciple of Montaigne in the sense that he would have inherited a doctrine. Above all, he owes the Périgourdin gentleman a way of educating himself. Far from substituting Montaigne for his Jesuit schoolteachers, Descartes decided to teach himself from scratch, following the path indicated by Montaigne to achieve independence and firmness of judgment. The mindset that Descartes inherited from the Essays appears as something particularly obvious, in the two first parts of the Discours de la méthode . As the young Descartes left the Collège de La Flèche, he decided to travel, and to test his own value in action. “I employed the rest of my youth to travel, to see courts and armies, to meet people of varied humors and conditions, to collect varied experiences, to try myself in the meetings that fortune was offering me (…).” [ 58 ] Education, taken out of a school context, is presented as an essay of the self through experience. The world, as pedagogue, has been substituted for books and teachers. This new education allows Descartes to get rid of the prejudice of overrating his own customs, a widespread phenomenon that we now call ethnocentrism. Montaigne’s legacy becomes particularly conspicuous when Descartes draws the lesson from his travels, “having acknowledged that those who have very contrary feelings to ours are not barbarians or savages, but that many of them make use of reason as much or more so than we do”. And also : “It is good to know something of different people, in order to judge our own with more sanity, and not to think that everything that is against our customs and habits is ridiculous and against reason, as usually do those who have never seen anything.” [ 59 ] Like Montaigne, Descartes begins by philosophizing on life with no other device than the a discipline of judgment: “I was learning not to believe anything too firmly, of which I had been persuaded through example and custom.” [ 60 ] He departs nevertheless from Montaigne when he will equate with error opinions that are grounded on custom. [ 61 ] The latter would not have dared to speak of error: varied opinions, having more or less authority, are to be weighed upon the scale of judgment. It is thus not correct to interpret Montaigne’s philosophy as a “criticism of prejudice” from a Cartesian stance.

In recent years, critics have stressed the importance of the connection between Montaigne and Hobbes for the development of a modern vision of politics, rooted in a criticism of traditional doctrines of man and society. At the time when Shakespeare was writing his plays, the first English translation of Montaigne’s Essays by John Florio (1603) became a widely-read classic in England. As a former student of Magdalen Hall (Oxford) and Saint John’s College (Cambridge), and as a young tutor and secretary to aristocratic and wealthy families, Thomas Hobbes had many opportunities to read Montaigne in the libraries he frequented. In his capacity as tutor, he traveled widely in Europe and spent several sojourns in France, before the English Civil War forced him into exile in Paris (1641–1651). During this period, Hobbes moved in skeptical and libertine circles and met scholars such as Sorbière, Gassendi, and La Mothe Le Vayer, all influenced by a shared reference to Montaigne’s skepticism. Historical documents and comparative research confirm the relevance of Montaigne’s influence on Hobbes’s work, from Elements of Law to Leviathan . [ 62 ] The two authors share a philosophical conception of man as driven by desire and imagination, and relentlessly striving for self-conservation and power. Montaigne identified human life with movement and instability, and pointed to the power that our passions have to push us toward imaginary future accomplishments (honor, glory, science, reason, and so on). [ 63 ] In Leviathan , Hobbes builds on this position to assert, as a general inclination of all mankind, “a perpetual and restless desire of power after power, that ceases only in death”. [ 64 ] This shared anthropology shows the extent to which Montaigne and Hobbes refute the Scholastic and Renaissance anthropocentric idea of man as a rational being at the summit of creation. On the contrary, they underline his instinctive and passionate nature, which eventually leads to violence and conflict wherever the political community collapses. This negative anthropology is to be understood in the light of the historical experience of the civil wars upsetting both their countries. [ 65 ] The threat of political turmoil imbued both Montaigne and Hobbes’ lives. Whereas Hobbes quoted the ancient saying homo homini lupus , and described the human condition outside the civil state as a war “where every man is enemy to every man”, [ 66 ] Montaigne seemed to go further, “having learned by experience, from the cruelty of some Christians, that there is no beast in the world to be feared by man as man”. [ 67 ] In order to avoid the outburst of violence, they both recognize the necessity of laws and obedience, a necessity that does not rely on any ontological or moral foundation. The normative force of law results from its practical necessity, as it is the rational condition of life in society. [ 68 ] As Montaigne wrote: “Now laws remain in credit not because they are just, but because they are laws”. [ 69 ] Questioning the Aristotelian vision of politics as a natural goal for humanity, Montaigne and Hobbes pointed out the man-made nature of civil authority, as founded in the need to preserve life and peace, avoiding violence and war.

Montaigne cultivates his liberty by not adhering exclusively to any one idea, while at the same time exploring them all. In exercising his judgment on various topics, he trains himself to go off on fresh tracks, starting from something he read or experienced. For Montaigne this also means calling into question the convictions of his time, reflecting upon his beliefs and education, and cultivating his own personal thoughts. His language can be said to obey only one rule, that is, to be “an effect of judgment and sincerity,” [ 70 ] which is the very one that he demands from the pupil. His language bears an unmistakable tone but contradicts itself sometimes from one place to another, perhaps for the very reason that it follows so closely the movements of thought.

If being a philosopher means being insensitive to human frailties and to the evils or to the pleasures which befall us, then Montaigne is not a philosopher. If it means using a “jargon”, and being able to enter the world of scholars, then Montaigne is not one either. Yet, if being a philosopher is being able to judge properly in any circumstances of life, then the Essays are the exemplary testimony of an author who wanted to be a philosopher for good. Montaigne is putting his judgment to trial on whatever subject, in order not only to get to know its value, but also to form and strengthen it.

He manages thus to offer us a philosophy in accordance with life. As Nietzsche puts it, “that such a man has written, joy on earth has truly increased…If my task were to make this earth a home, I would attach myself to him.” Or, as Stefan Zweig said, in a context which was closer to the historical reality experienced by Montaigne himself : “Montaigne helps us answer this one question: ‘How to stay free? How to preserve our inborn clear-mindedness in front of all the threats and dangers of fanaticism, how to preserve the humanity of our hearts among the upsurge of bestiality?’”

- Essais , F. Strowski (ed.), Paris: Hachette, 1912, Phototypic reproduction of the “Exemplaire de Bordeaux”, showing Montaigne’s handwritten additions of 1588–1592.

- Essais , Pierre Villey (ed.), 3 volumes, Alcan, 1922–1923, revised by V.-L. Saulnier, 1965. Gives the 3 strata indications, probable dates of composition of the chapters, and many sources.

- Michel de Montaigne. Les Essais , J. Balsamo, C. Magnien-Simonin & M. Magnien (eds.) (with “Notes de lecture” and “Sentences peintes” edited by Alain Legros), Paris, “Pléiade”, Gallimard, 2007. The Essays are based on the 1595 published version.

- La Théologie naturelle de Raymond Sebond , traduicte nouvellement en François par Messire Michel, Seigneur de Montaigne, Chevalier de l’ordre du Roy et Gentilhomme ordinaire de sa chambre . Ed. by Dr Armaingaud, Paris: Conard, 1935.

- Le Journal de Voyage en Italie de Michel de Montaigne . Ed. by François Rigolot, Paris: PUF, 1992.

- Lettres . Ed. by Arthur Armaingaud, Paris, Conard, 1939 (vol. XI, in Œuvres complètes , pp. 159–266).

- The Essayes , tr. by John Florio. London: V. Sims, 1603.

- The Essays , tr. by Charles Cotton. 3 vol., London: T. Basset, M. Gilliflower and W. Hensman, 1685–1686.

- The Essays , tr. by E.J. Trechmann. 2 vol., Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1927.

- Michel de Montaigne. The Complete Works. Essays, Travel Journal, Letters, tr. by Donald M. Frame , Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1958, renewed 1971 & 1976.

- The Complete Essays , tr. by M.A. Screech, London/New York: Penguin, 1993.

- The Journal of Montaigne’s Travels , tr. by W.G. Watters, 3 vol., London: John Murray, 1903.

- The Diary of Montaigne’s Journey to Italy in 1580 and 1581 , tr. by E.J. Trechmann. London: Hogarth Press, 1929.

- Auerbach, Erich, 1946, “l’humaine condition” (on Montaigne) in Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, trans . Willard Trask. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003 (originally pub. Bern: Francke).

- Burke, Peter, 1981, Montaigne , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Compayré, Gabriel, 1908, Montaigne and the Education of the Judgment, trans. J. E. Mansion, New York: Burt Franklin, 1971.

- Conche, Marcel, 1996, Montaigne et la philosophie , Paris: PUF.

- Desan, Philippe, 2017, Montaigne: A Life , Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ––– (ed.), 2007, Dictionnaire de Montaigne , Paris: Champion.

- ––– (ed.), 2016, The Oxford Handbook of Montaigne , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ferrari, Emiliano, & Gontier, Thierry, 2016, L’Axe Montaigne-Hobbes: anthropologie et politique , Paris: Classiques Garnier.

- Frame, Donald M., 1984, Montaigne: A Biography , New York: Harcourt/ London: Hamish Hamilton, 1965/ San Francisco: North Point Press.

- Friedrich, Hugo, 1991, Montaigne , Bern: Francke, 1949; Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Fontana, Biancamaria, 2008, Montaigne’s Politics: Authority and Governance in the Essays , Geneva: Princeton University Press.

- Hoffmann, Georges, 1998, Montaigne’s Career , Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Horkheimer, Max, 1938, Montaigne und die Funktion der Skepsis , Frankfurt: Fischer, reprinted 1971.

- Imbach, Ruedi, 1983, “‘Et toutefois nostre outrecuidance veut faire passer la divinité par nostre estamine’, l’essai II,12 et la genèse de la pensée moderne. Construction d’une thèse explicative” in Paradigmes de théologie philosophique , O. Höffe et R. Imbach (eds.), Fribourg.

- Ulrich Langer, 2005, The Cambridge Companion to Montaigne , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Leake, R.E., 1981, Concordance des Essais de Montaigne , 2 vol., Genève: Droz.

- Paganini, Gianni, 2008, Skepsis. Le débat des modernes sur le scepticisme , Paris: Vrin.

- Popkin, Richard, 1960, The History of Scepticism from Erasmus to Descartes , Assen: Van Gorcum.

- –––, 1979, The History of Scepticism from Erasmus to Spinoza , Berkeley: University of California Press.

- –––, 2003, The History of Scepticism from Savonarola to Bayle , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schmitt, Charles B., 1972, Cicero scepticus : A Study of the Influence of the Academica in the Renaissance , The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

- Screech, Michael, 1983, Montaigne & Melancholy — The Wisdom of the Essays , London: Duckworth.

- –––, 1998, Montaigne’s Annotated Copy of Lucretius, A transcription and study of the manuscript, notes and pen-marks , Geneva: Droz.

- Skinner, Quentin, 2002, Visions of Politics (Volume 3: Hobbes and Civil Science), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Starobinski, Jean, 2009, Montaigne in Motion , University of Chicago Press.

- Supple, James, 1984, Arms versus Letters, The Military and Literary Ideals in the Essays , Cambridge: Clarendon Press.

- Thompson, Douglas, 2018, Montaigne and the Tolerance of Politics , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tournon, André, 1983, La glose et l’essai , Paris: H. Champion, reprinted 2001.

- Zweig, Stefan, 1960, Montaigne [written 1935–1941] Frankfurt: Fischer.

How to cite this entry . Preview the PDF version of this entry at the Friends of the SEP Society . Look up topics and thinkers related to this entry at the Internet Philosophy Ontology Project (InPhO). Enhanced bibliography for this entry at PhilPapers , with links to its database.

Other Internet Resources

- The complete, searchable text of the Villey-Saulnier edition , from the ARFTL project at the University of Chicago (French)

- Montaigne Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum , Philippe Desan, ed., (University of Chicago).

- Portrait Gallery , in Montaigne Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum

- Montaigne’s Essays John Florio’s translation (first published 1603, Ben R. Schneider (ed.), Lawrence University, Wisconsin, from The World’s Classics, 1904, 1910, 1924), published at Renascence Editions, U. Oregon

- Essays of Michel De Montaigne , translated (1685–1686) by Charles Cotton, edited by William Carew Hazlitt, London: Reeves anbd Turner.

civic humanism | Descartes, René | -->humanism: in the Renaissance --> | liberty: positive and negative | relativism | Sextus Empiricus | skepticism | Stoicism

Copyright © 2019 by Marc Foglia < marc . foglia @ gmail . com > Emiliano Ferrari < ferrariemil @ gmail . com >

- Accessibility

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The complete essays of Montaigne

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

1,297 Views

35 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by Christine Wagner on January 14, 2010

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- Corrections

Michel de Montaigne and the Art of the Personal Essay

Montaigne invented the essay genre after deciding he wanted to write a literary self-portrait of himself. This turned out to be an impossible task.

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) is one of France’s most celebrated literary giants . Born into a noble Catholic family from South West France, he spent many years sitting in Bordeaux’s parliament. But after 15 years working in the legal and political sphere, Montaigne retired to his country estate in Dordogne.

It was here, inside a small library within one of his chateau towers , that Montaigne began writing the Essays . He published the first two volumes of these essays in 1580, followed by a third in 1588. Within their pages he wrote chapters of varying lengths (sometimes only a few paragraphs, sometimes hundreds of pages long) on a wide array of topics ranging from architecture to child-rearing. His writing style was unusual in the 16th century for its complete honesty and informality.

The Essays: Michel de Montaigne’s Personal and Historical Context

Before we dive into the essays themselves, it’s helpful to understand Montaigne’s mindset when he first began writing in 1571. The nobleman had already suffered a series of personal tragedies by the time he put quill to parchment. His close friend Étienne de la Boétie passed away in 1563, followed by Montaigne’s beloved father Pierre only a few years later in 1568.

In fact, Montaigne was arguably surrounded by death throughout his life. He and his wife Françoise had several children, but only one daughter, Léonore, survived childhood. Furthermore, France was embroiled in a bloody civil war between Catholic and Protestant factions for much of the latter half of the 16th century. This violence reached the walls of Montaigne’s chateau on many occasions. Montaigne himself was twice accosted by spies and soldiers who wanted to kidnap or kill him, but in both cases he managed to talk his way out of trouble.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

In this context of grief and bloody violence, Montaigne began to look inwardly to himself. After all, his external reality, which was filled with family tragedy and religious massacres, didn’t seem to be making much sense. It’s hardly surprising that in his famous preface to the Essays , the author expresses a belief that his own death will occur fairly soon. Therefore his writing will serve as a legacy, a reminder of his character and personality once he is dead.

This is where the unique nature of Montaigne’s writing comes into play. In the Essays he wants to try and pin down his own thoughts and feelings on paper, amid the uncertainty and violence of the world around him. He accepts that there are plenty of things he knows very little about, which is why he often defers to other people by including direct quotations from ancient philosophers and historians in his writing. But what he can do is draw on his own experience, i.e. his memories, personal events etc. and combine it with the books and philosophies that have shaped him, in order to try and sketch a self-portrait of himself.

The Essays were printed and widely disseminated throughout Europe, bringing Michel de Montaigne a large degree of fame during his lifetime. He continued to write and rewrite previous editions of his work, resulting in several versions of the Essays in circulation. Eventually, after some brief periods of travel across France and Italy, ill health confined Montaigne to his chateau once again. He died of quinsy at the age of 59.

The Unique Composition of the Essays

As you may have guessed, the Essays (in French: Essais ) are an unusual collection of writing. The word ‘essay’ itself comes from the French verb ‘essayer’ i.e. ‘to attempt’. Each chapter is Montaigne’s attempt to explore a particular topic, whether it be child-rearing or suicide , by capturing the natural flow of his thoughts as they enter his mind. In a chapter on politeness, for example, he might begin by discussing a famous quote on being polite, then compare this with what various philosophers say on the matter, before finally reflecting on his own attitude towards politeness.

Despite being a member of the upper classes, Montaigne discusses historical events and philosophical questions alongside personal anecdotes and health issues (including his bowel movements and napping schedule!). Although it’s now a common literary genre, this free-flowing essay form was completely new to 16th century audiences. The Essays represented the origins of an entirely new way of writing.

What makes Michel de Montaigne’s writing even more unique was his insistence on constantly revising what he had already published. In later editions, he added hundreds of annotations (sometimes several paragraphs long) or hastily deleted sentences and quotes he no longer liked. In fact, this constant rewriting highlights just how difficult it is to paint a literary self-portrait. Our ideas and opinions on subjects are constantly changing over the course of our lifetime. The Essays are a record of how Montaigne’s own mindset evolved as he grew older, read more books and experienced even more of life.

Montaigne and the Act of (Re)writing

Indeed, the rewriting process feeds into this problem which Montaigne encounters during his writing. In a chapter entitled ‘On Repentance’, he ends up discussing how difficult he finds it to record himself through the medium of writing: “I can’t pin down my object. It is tumultuous, it flutters around” (Montaigne, 2007). Then he asserts one of his most famous dictums: “I don’t paint the being. I paint the passage” (Montaigne, 2007). Here he illustrates what he believes to be one of the key conditions of human existence: that all human beings are constantly in flux.

Michel de Montaigne can never truly give a single self-portrait of himself through his writing. Because he, like us, is constantly changing over time. His body is aging, his emotions change from day to day, his favorite authors and philosophers evolve as he reads more books. He cannot write the ‘being’ because it’s constantly in flux, so he can only record the ‘passage’ of himself as it changes from day to day, minute to minute.

The Philosophical Significance of the Essays

So if we’re constantly in flux, how can we ever do what a philosopher wants to do best and try to find truth? After all, Montaigne acknowledges that learning and attempting to find truth in the world is often portrayed as the most distinguished way to spend one’s time: “We are born to seek out truth…the world is nothing but a school of learning” (Montaigne, 2007).

Montaigne suggests that we humans possess a strong desire to fulfill our curiosity. Furthermore, when Michel de Montaigne discusses truth, he often uses verbs such as ‘to seek’ or ‘to search’ but never claims to have finally ‘found’ the truth. This suggests that he believes truth-seeking to be an open-ended journey, one which will never quite be fully realized. This is mirrored in the writing of the Essays themselves, which were edited and re-edited by their author, before subsequently spawning a long tradition of academic scholarship which still debates the meaning of Montaigne’s writing today.

In a temporal world , learning and accessing truth is challenging. Montaigne often uses the French word branle (which roughly translates as ‘inconstant movement’) to describe time. Time’s inconstancy affects us every single day. Montaigne points out that each new day brings new feelings and flights of imagination, leading us to flit between different opinions. Time’s inconstancy isn’t just reflected in the external world i.e. through the changing seasons, but it also affects the inner essence of our being. And we humans allow ourselves to drift along in this way, stating an opinion then changing it an hour later, for the entirety of our lives on earth: “It’s nothing but inconstancy” (Montaigne, 2007).

When it comes to pinning down a literary self-portrait, Montaigne struggles due to the impermanence of living in time: “If I speak of myself in different ways, it’s because I view myself differently” (Montaigne, 2007). However, his commitment to writing and rewriting his thoughts shows his determination to try and find truth in the world despite all of its uncertainty. Even though human beings exist in temporal flux, we still have a brain and rational tools which allow us to live in time. Truth-seeking means doing what Montaigne is doing with his writing: drawing on your own experience and writing down your thoughts to try and know yourself. After all, the one thing that humans can reliably claim to know about is themselves.

Michel de Montaigne’s Literary and Philosophical Legacy

The Essays are celebrated due to their inventive nature. In the end, Montaigne didn’t care that he would never be able to represent himself faithfully through writing. He accepts that this is the way of the world, and puts quill to parchment anyway. Scholar Terence Cave once described the Essays as “the richest and most productive thought-experiment ever committed to paper” (Cave, 2007). Furthermore, as stated above, the clue is in the name essay , which means ‘attempt’: as he reflects on the French civil war or the nature of custom, his thoughts shift and change. He is trying, and that’s all we can ever do.

Montaigne has also defied classification as a philosopher. Sometimes he favors Stoicism as a world view, at other times he prefers the Skeptics. And unlike many philosophers who are seeking a way to live in the world , Michel de Montaigne refuses to give a final judgment on whatever topic he is writing about. His personal anecdotes and moral reflections always lead towards open-ended conclusions. He doesn’t seek to provide his readers with absolute answers to life’s major questions. What he does do is attempt to record himself searching for those answers in vain.

Bibliography

Terence Cave, How to Read Montaigne (London: Granta, 2007)

Michel de Montaigne, Les Essais , ed. by Jean Balsamo, Michel Magnien & Catherine Magnien-Simonen (Paris: Gallimard, 2007)

10 Characteristics of Renaissance Architecture

By Rachel Ashcroft MSc Comparative Literature, PhD Renaissance Philosophy Rachel is a contributing writer and journalist with an academic background in European languages, literature and philosophy. She has an MA in French and Italian and an MSc in Comparative Literature from the University of Edinburgh. Rachel completed a PhD in Renaissance conceptions of time at Durham University. Now living back in Edinburgh, she regularly publishes articles and book reviews related to her specialty for a range of publications including The Economist.

Frequently Read Together

The Philosophy of Death: Is it Rational to Fear Death?

Classicism and The Renaissance: The Rebirth of Antiquity in Europe

Does Kantian Ethics Permit Euthanasia?

- Project Gutenberg

- 73,365 free eBooks

- 33 by Michel de Montaigne

Essays of Michel de Montaigne — Volume 03 by Michel de Montaigne

Read now or download (free!)

Similar books, about this ebook.

- Privacy policy

- About Project Gutenberg

- Terms of Use

- Contact Information

Michel de Montaigne and the Art of Writing an Essay

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592)

On February 28, 1533, French philosopher Michel de Montaigne was born. Montaigne was one of the most significant philosophers of the French Renaissance , known for popularizing the essay as a literary genre. His work is noted for its merging of casual anecdotes and autobiography with intellectual insight. His massive volume Essais contains some of the most influential essays ever written.

“We are, I know not how, double in ourselves, so that what we believe we disbelieve, and cannot rid ourselves of what we condemn.” – Michel de Montagne, as quoted in [9]

Michel de Montaigne – Early Years