Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

How to Write a Research Paper Introduction (with Examples)

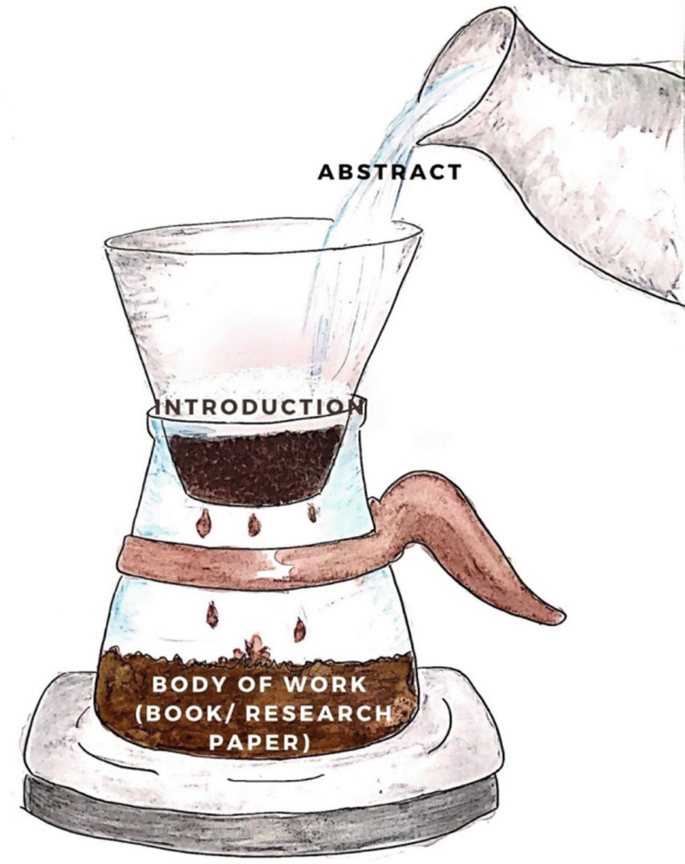

The research paper introduction section, along with the Title and Abstract, can be considered the face of any research paper. The following article is intended to guide you in organizing and writing the research paper introduction for a quality academic article or dissertation.

The research paper introduction aims to present the topic to the reader. A study will only be accepted for publishing if you can ascertain that the available literature cannot answer your research question. So it is important to ensure that you have read important studies on that particular topic, especially those within the last five to ten years, and that they are properly referenced in this section. 1 What should be included in the research paper introduction is decided by what you want to tell readers about the reason behind the research and how you plan to fill the knowledge gap. The best research paper introduction provides a systemic review of existing work and demonstrates additional work that needs to be done. It needs to be brief, captivating, and well-referenced; a well-drafted research paper introduction will help the researcher win half the battle.

The introduction for a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your research topic

- Capture reader interest

- Summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Define your specific research problem and problem statement

- Highlight the novelty and contributions of the study

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The research paper introduction can vary in size and structure depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or is a review paper. Some research paper introduction examples are only half a page while others are a few pages long. In many cases, the introduction will be shorter than all of the other sections of your paper; its length depends on the size of your paper as a whole.

- Break through writer’s block. Write your research paper introduction with Paperpal Copilot

Table of Contents

What is the introduction for a research paper, why is the introduction important in a research paper, craft a compelling introduction section with paperpal. try now, 1. introduce the research topic:, 2. determine a research niche:, 3. place your research within the research niche:, craft accurate research paper introductions with paperpal. start writing now, frequently asked questions on research paper introduction, key points to remember.

The introduction in a research paper is placed at the beginning to guide the reader from a broad subject area to the specific topic that your research addresses. They present the following information to the reader

- Scope: The topic covered in the research paper

- Context: Background of your topic

- Importance: Why your research matters in that particular area of research and the industry problem that can be targeted

The research paper introduction conveys a lot of information and can be considered an essential roadmap for the rest of your paper. A good introduction for a research paper is important for the following reasons:

- It stimulates your reader’s interest: A good introduction section can make your readers want to read your paper by capturing their interest. It informs the reader what they are going to learn and helps determine if the topic is of interest to them.

- It helps the reader understand the research background: Without a clear introduction, your readers may feel confused and even struggle when reading your paper. A good research paper introduction will prepare them for the in-depth research to come. It provides you the opportunity to engage with the readers and demonstrate your knowledge and authority on the specific topic.

- It explains why your research paper is worth reading: Your introduction can convey a lot of information to your readers. It introduces the topic, why the topic is important, and how you plan to proceed with your research.

- It helps guide the reader through the rest of the paper: The research paper introduction gives the reader a sense of the nature of the information that will support your arguments and the general organization of the paragraphs that will follow. It offers an overview of what to expect when reading the main body of your paper.

What are the parts of introduction in the research?

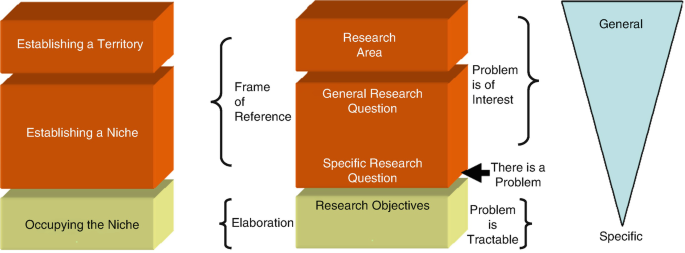

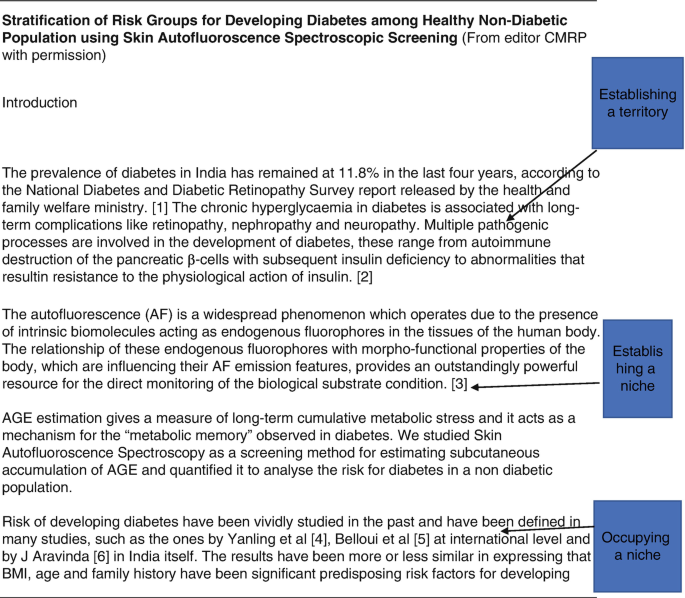

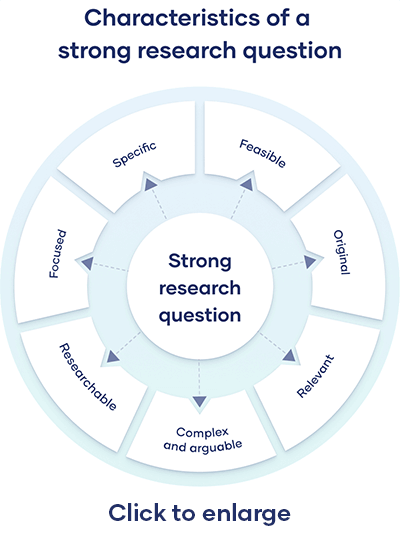

A good research paper introduction section should comprise three main elements: 2

- What is known: This sets the stage for your research. It informs the readers of what is known on the subject.

- What is lacking: This is aimed at justifying the reason for carrying out your research. This could involve investigating a new concept or method or building upon previous research.

- What you aim to do: This part briefly states the objectives of your research and its major contributions. Your detailed hypothesis will also form a part of this section.

How to write a research paper introduction?

The first step in writing the research paper introduction is to inform the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening statement. The second step involves establishing the kinds of research that have been done and ending with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to address. Finally, the research paper introduction clarifies how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses. If your research involved testing hypotheses, these should be stated along with your research question. The hypothesis should be presented in the past tense since it will have been tested by the time you are writing the research paper introduction.

The following key points, with examples, can guide you when writing the research paper introduction section:

- Highlight the importance of the research field or topic

- Describe the background of the topic

- Present an overview of current research on the topic

Example: The inclusion of experiential and competency-based learning has benefitted electronics engineering education. Industry partnerships provide an excellent alternative for students wanting to engage in solving real-world challenges. Industry-academia participation has grown in recent years due to the need for skilled engineers with practical training and specialized expertise. However, from the educational perspective, many activities are needed to incorporate sustainable development goals into the university curricula and consolidate learning innovation in universities.

- Reveal a gap in existing research or oppose an existing assumption

- Formulate the research question

Example: There have been plausible efforts to integrate educational activities in higher education electronics engineering programs. However, very few studies have considered using educational research methods for performance evaluation of competency-based higher engineering education, with a focus on technical and or transversal skills. To remedy the current need for evaluating competencies in STEM fields and providing sustainable development goals in engineering education, in this study, a comparison was drawn between study groups without and with industry partners.

- State the purpose of your study

- Highlight the key characteristics of your study

- Describe important results

- Highlight the novelty of the study.

- Offer a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

Example: The study evaluates the main competency needed in the applied electronics course, which is a fundamental core subject for many electronics engineering undergraduate programs. We compared two groups, without and with an industrial partner, that offered real-world projects to solve during the semester. This comparison can help determine significant differences in both groups in terms of developing subject competency and achieving sustainable development goals.

Write a Research Paper Introduction in Minutes with Paperpal

Paperpal Copilot is a generative AI-powered academic writing assistant. It’s trained on millions of published scholarly articles and over 20 years of STM experience. Paperpal Copilot helps authors write better and faster with:

- Real-time writing suggestions

- In-depth checks for language and grammar correction

- Paraphrasing to add variety, ensure academic tone, and trim text to meet journal limits

With Paperpal Copilot, create a research paper introduction effortlessly. In this step-by-step guide, we’ll walk you through how Paperpal transforms your initial ideas into a polished and publication-ready introduction.

How to use Paperpal to write the Introduction section

Step 1: Sign up on Paperpal and click on the Copilot feature, under this choose Outlines > Research Article > Introduction

Step 2: Add your unstructured notes or initial draft, whether in English or another language, to Paperpal, which is to be used as the base for your content.

Step 3: Fill in the specifics, such as your field of study, brief description or details you want to include, which will help the AI generate the outline for your Introduction.

Step 4: Use this outline and sentence suggestions to develop your content, adding citations where needed and modifying it to align with your specific research focus.

Step 5: Turn to Paperpal’s granular language checks to refine your content, tailor it to reflect your personal writing style, and ensure it effectively conveys your message.

You can use the same process to develop each section of your article, and finally your research paper in half the time and without any of the stress.

The purpose of the research paper introduction is to introduce the reader to the problem definition, justify the need for the study, and describe the main theme of the study. The aim is to gain the reader’s attention by providing them with necessary background information and establishing the main purpose and direction of the research.

The length of the research paper introduction can vary across journals and disciplines. While there are no strict word limits for writing the research paper introduction, an ideal length would be one page, with a maximum of 400 words over 1-4 paragraphs. Generally, it is one of the shorter sections of the paper as the reader is assumed to have at least a reasonable knowledge about the topic. 2 For example, for a study evaluating the role of building design in ensuring fire safety, there is no need to discuss definitions and nature of fire in the introduction; you could start by commenting upon the existing practices for fire safety and how your study will add to the existing knowledge and practice.

When deciding what to include in the research paper introduction, the rest of the paper should also be considered. The aim is to introduce the reader smoothly to the topic and facilitate an easy read without much dependency on external sources. 3 Below is a list of elements you can include to prepare a research paper introduction outline and follow it when you are writing the research paper introduction. Topic introduction: This can include key definitions and a brief history of the topic. Research context and background: Offer the readers some general information and then narrow it down to specific aspects. Details of the research you conducted: A brief literature review can be included to support your arguments or line of thought. Rationale for the study: This establishes the relevance of your study and establishes its importance. Importance of your research: The main contributions are highlighted to help establish the novelty of your study Research hypothesis: Introduce your research question and propose an expected outcome. Organization of the paper: Include a short paragraph of 3-4 sentences that highlights your plan for the entire paper

Cite only works that are most relevant to your topic; as a general rule, you can include one to three. Note that readers want to see evidence of original thinking. So it is better to avoid using too many references as it does not leave much room for your personal standpoint to shine through. Citations in your research paper introduction support the key points, and the number of citations depend on the subject matter and the point discussed. If the research paper introduction is too long or overflowing with citations, it is better to cite a few review articles rather than the individual articles summarized in the review. A good point to remember when citing research papers in the introduction section is to include at least one-third of the references in the introduction.

The literature review plays a significant role in the research paper introduction section. A good literature review accomplishes the following: Introduces the topic – Establishes the study’s significance – Provides an overview of the relevant literature – Provides context for the study using literature – Identifies knowledge gaps However, remember to avoid making the following mistakes when writing a research paper introduction: Do not use studies from the literature review to aggressively support your research Avoid direct quoting Do not allow literature review to be the focus of this section. Instead, the literature review should only aid in setting a foundation for the manuscript.

Remember the following key points for writing a good research paper introduction: 4

- Avoid stuffing too much general information: Avoid including what an average reader would know and include only that information related to the problem being addressed in the research paper introduction. For example, when describing a comparative study of non-traditional methods for mechanical design optimization, information related to the traditional methods and differences between traditional and non-traditional methods would not be relevant. In this case, the introduction for the research paper should begin with the state-of-the-art non-traditional methods and methods to evaluate the efficiency of newly developed algorithms.

- Avoid packing too many references: Cite only the required works in your research paper introduction. The other works can be included in the discussion section to strengthen your findings.

- Avoid extensive criticism of previous studies: Avoid being overly critical of earlier studies while setting the rationale for your study. A better place for this would be the Discussion section, where you can highlight the advantages of your method.

- Avoid describing conclusions of the study: When writing a research paper introduction remember not to include the findings of your study. The aim is to let the readers know what question is being answered. The actual answer should only be given in the Results and Discussion section.

To summarize, the research paper introduction section should be brief yet informative. It should convince the reader the need to conduct the study and motivate him to read further. If you’re feeling stuck or unsure, choose trusted AI academic writing assistants like Paperpal to effortlessly craft your research paper introduction and other sections of your research article.

1. Jawaid, S. A., & Jawaid, M. (2019). How to write introduction and discussion. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia, 13(Suppl 1), S18.

2. Dewan, P., & Gupta, P. (2016). Writing the title, abstract and introduction: Looks matter!. Indian pediatrics, 53, 235-241.

3. Cetin, S., & Hackam, D. J. (2005). An approach to the writing of a scientific Manuscript1. Journal of Surgical Research, 128(2), 165-167.

4. Bavdekar, S. B. (2015). Writing introduction: Laying the foundations of a research paper. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 63(7), 44-6.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Scientific Writing Style Guides Explained

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

- 8 Most Effective Ways to Increase Motivation for Thesis Writing

Practice vs. Practise: Learn the Difference

Academic paraphrasing: why paperpal’s rewrite should be your first choice , you may also like, phd qualifying exam: tips for success , ai in education: it’s time to change the..., is it ethical to use ai-generated abstracts without..., what are journal guidelines on using generative ai..., quillbot review: features, pricing, and free alternatives, what is an academic paper types and elements , should you use ai tools like chatgpt for..., publish research papers: 9 steps for successful publications , what are the different types of research papers, how to make translating academic papers less challenging.

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Paper Introduction – Writing Guide and Examples

Research Paper Introduction – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Paper Introduction

Research paper introduction is the first section of a research paper that provides an overview of the study, its purpose, and the research question (s) or hypothesis (es) being investigated. It typically includes background information about the topic, a review of previous research in the field, and a statement of the research objectives. The introduction is intended to provide the reader with a clear understanding of the research problem, why it is important, and how the study will contribute to existing knowledge in the field. It also sets the tone for the rest of the paper and helps to establish the author’s credibility and expertise on the subject.

How to Write Research Paper Introduction

Writing an introduction for a research paper can be challenging because it sets the tone for the entire paper. Here are some steps to follow to help you write an effective research paper introduction:

- Start with a hook : Begin your introduction with an attention-grabbing statement, a question, or a surprising fact that will make the reader interested in reading further.

- Provide background information: After the hook, provide background information on the topic. This information should give the reader a general idea of what the topic is about and why it is important.

- State the research problem: Clearly state the research problem or question that the paper addresses. This should be done in a concise and straightforward manner.

- State the research objectives: After stating the research problem, clearly state the research objectives. This will give the reader an idea of what the paper aims to achieve.

- Provide a brief overview of the paper: At the end of the introduction, provide a brief overview of the paper. This should include a summary of the main points that will be discussed in the paper.

- Revise and refine: Finally, revise and refine your introduction to ensure that it is clear, concise, and engaging.

Structure of Research Paper Introduction

The following is a typical structure for a research paper introduction:

- Background Information: This section provides an overview of the topic of the research paper, including relevant background information and any previous research that has been done on the topic. It helps to give the reader a sense of the context for the study.

- Problem Statement: This section identifies the specific problem or issue that the research paper is addressing. It should be clear and concise, and it should articulate the gap in knowledge that the study aims to fill.

- Research Question/Hypothesis : This section states the research question or hypothesis that the study aims to answer. It should be specific and focused, and it should clearly connect to the problem statement.

- Significance of the Study: This section explains why the research is important and what the potential implications of the study are. It should highlight the contribution that the research makes to the field.

- Methodology: This section describes the research methods that were used to conduct the study. It should be detailed enough to allow the reader to understand how the study was conducted and to evaluate the validity of the results.

- Organization of the Paper : This section provides a brief overview of the structure of the research paper. It should give the reader a sense of what to expect in each section of the paper.

Research Paper Introduction Examples

Research Paper Introduction Examples could be:

Example 1: In recent years, the use of artificial intelligence (AI) has become increasingly prevalent in various industries, including healthcare. AI algorithms are being developed to assist with medical diagnoses, treatment recommendations, and patient monitoring. However, as the use of AI in healthcare grows, ethical concerns regarding privacy, bias, and accountability have emerged. This paper aims to explore the ethical implications of AI in healthcare and propose recommendations for addressing these concerns.

Example 2: Climate change is one of the most pressing issues facing our planet today. The increasing concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere has resulted in rising temperatures, changing weather patterns, and other environmental impacts. In this paper, we will review the scientific evidence on climate change, discuss the potential consequences of inaction, and propose solutions for mitigating its effects.

Example 3: The rise of social media has transformed the way we communicate and interact with each other. While social media platforms offer many benefits, including increased connectivity and access to information, they also present numerous challenges. In this paper, we will examine the impact of social media on mental health, privacy, and democracy, and propose solutions for addressing these issues.

Example 4: The use of renewable energy sources has become increasingly important in the face of climate change and environmental degradation. While renewable energy technologies offer many benefits, including reduced greenhouse gas emissions and energy independence, they also present numerous challenges. In this paper, we will assess the current state of renewable energy technology, discuss the economic and political barriers to its adoption, and propose solutions for promoting the widespread use of renewable energy.

Purpose of Research Paper Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper serves several important purposes, including:

- Providing context: The introduction should give readers a general understanding of the topic, including its background, significance, and relevance to the field.

- Presenting the research question or problem: The introduction should clearly state the research question or problem that the paper aims to address. This helps readers understand the purpose of the study and what the author hopes to accomplish.

- Reviewing the literature: The introduction should summarize the current state of knowledge on the topic, highlighting the gaps and limitations in existing research. This shows readers why the study is important and necessary.

- Outlining the scope and objectives of the study: The introduction should describe the scope and objectives of the study, including what aspects of the topic will be covered, what data will be collected, and what methods will be used.

- Previewing the main findings and conclusions : The introduction should provide a brief overview of the main findings and conclusions that the study will present. This helps readers anticipate what they can expect to learn from the paper.

When to Write Research Paper Introduction

The introduction of a research paper is typically written after the research has been conducted and the data has been analyzed. This is because the introduction should provide an overview of the research problem, the purpose of the study, and the research questions or hypotheses that will be investigated.

Once you have a clear understanding of the research problem and the questions that you want to explore, you can begin to write the introduction. It’s important to keep in mind that the introduction should be written in a way that engages the reader and provides a clear rationale for the study. It should also provide context for the research by reviewing relevant literature and explaining how the study fits into the larger field of research.

Advantages of Research Paper Introduction

The introduction of a research paper has several advantages, including:

- Establishing the purpose of the research: The introduction provides an overview of the research problem, question, or hypothesis, and the objectives of the study. This helps to clarify the purpose of the research and provide a roadmap for the reader to follow.

- Providing background information: The introduction also provides background information on the topic, including a review of relevant literature and research. This helps the reader understand the context of the study and how it fits into the broader field of research.

- Demonstrating the significance of the research: The introduction also explains why the research is important and relevant. This helps the reader understand the value of the study and why it is worth reading.

- Setting expectations: The introduction sets the tone for the rest of the paper and prepares the reader for what is to come. This helps the reader understand what to expect and how to approach the paper.

- Grabbing the reader’s attention: A well-written introduction can grab the reader’s attention and make them interested in reading further. This is important because it can help to keep the reader engaged and motivated to read the rest of the paper.

- Creating a strong first impression: The introduction is the first part of the research paper that the reader will see, and it can create a strong first impression. A well-written introduction can make the reader more likely to take the research seriously and view it as credible.

- Establishing the author’s credibility: The introduction can also establish the author’s credibility as a researcher. By providing a clear and thorough overview of the research problem and relevant literature, the author can demonstrate their expertise and knowledge in the field.

- Providing a structure for the paper: The introduction can also provide a structure for the rest of the paper. By outlining the main sections and sub-sections of the paper, the introduction can help the reader navigate the paper and find the information they are looking for.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Research Paper Title – Writing Guide and Example

Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and...

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 4. The Introduction

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The introduction leads the reader from a general subject area to a particular topic of inquiry. It establishes the scope, context, and significance of the research being conducted by summarizing current understanding and background information about the topic, stating the purpose of the work in the form of the research problem supported by a hypothesis or a set of questions, explaining briefly the methodological approach used to examine the research problem, highlighting the potential outcomes your study can reveal, and outlining the remaining structure and organization of the paper.

Key Elements of the Research Proposal. Prepared under the direction of the Superintendent and by the 2010 Curriculum Design and Writing Team. Baltimore County Public Schools.

Importance of a Good Introduction

Think of the introduction as a mental road map that must answer for the reader these four questions:

- What was I studying?

- Why was this topic important to investigate?

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study?

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding?

According to Reyes, there are three overarching goals of a good introduction: 1) ensure that you summarize prior studies about the topic in a manner that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem; 2) explain how your study specifically addresses gaps in the literature, insufficient consideration of the topic, or other deficiency in the literature; and, 3) note the broader theoretical, empirical, and/or policy contributions and implications of your research.

A well-written introduction is important because, quite simply, you never get a second chance to make a good first impression. The opening paragraphs of your paper will provide your readers with their initial impressions about the logic of your argument, your writing style, the overall quality of your research, and, ultimately, the validity of your findings and conclusions. A vague, disorganized, or error-filled introduction will create a negative impression, whereas, a concise, engaging, and well-written introduction will lead your readers to think highly of your analytical skills, your writing style, and your research approach. All introductions should conclude with a brief paragraph that describes the organization of the rest of the paper.

Hirano, Eliana. “Research Article Introductions in English for Specific Purposes: A Comparison between Brazilian, Portuguese, and English.” English for Specific Purposes 28 (October 2009): 240-250; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide. Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Reyes, Victoria. Demystifying the Journal Article. Inside Higher Education.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Structure and Approach

The introduction is the broad beginning of the paper that answers three important questions for the reader:

- What is this?

- Why should I read it?

- What do you want me to think about / consider doing / react to?

Think of the structure of the introduction as an inverted triangle of information that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem. Organize the information so as to present the more general aspects of the topic early in the introduction, then narrow your analysis to more specific topical information that provides context, finally arriving at your research problem and the rationale for studying it [often written as a series of key questions to be addressed or framed as a hypothesis or set of assumptions to be tested] and, whenever possible, a description of the potential outcomes your study can reveal.

These are general phases associated with writing an introduction: 1. Establish an area to research by:

- Highlighting the importance of the topic, and/or

- Making general statements about the topic, and/or

- Presenting an overview on current research on the subject.

2. Identify a research niche by:

- Opposing an existing assumption, and/or

- Revealing a gap in existing research, and/or

- Formulating a research question or problem, and/or

- Continuing a disciplinary tradition.

3. Place your research within the research niche by:

- Stating the intent of your study,

- Outlining the key characteristics of your study,

- Describing important results, and

- Giving a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

NOTE: It is often useful to review the introduction late in the writing process. This is appropriate because outcomes are unknown until you've completed the study. After you complete writing the body of the paper, go back and review introductory descriptions of the structure of the paper, the method of data gathering, the reporting and analysis of results, and the conclusion. Reviewing and, if necessary, rewriting the introduction ensures that it correctly matches the overall structure of your final paper.

II. Delimitations of the Study

Delimitations refer to those characteristics that limit the scope and define the conceptual boundaries of your research . This is determined by the conscious exclusionary and inclusionary decisions you make about how to investigate the research problem. In other words, not only should you tell the reader what it is you are studying and why, but you must also acknowledge why you rejected alternative approaches that could have been used to examine the topic.

Obviously, the first limiting step was the choice of research problem itself. However, implicit are other, related problems that could have been chosen but were rejected. These should be noted in the conclusion of your introduction. For example, a delimitating statement could read, "Although many factors can be understood to impact the likelihood young people will vote, this study will focus on socioeconomic factors related to the need to work full-time while in school." The point is not to document every possible delimiting factor, but to highlight why previously researched issues related to the topic were not addressed.

Examples of delimitating choices would be:

- The key aims and objectives of your study,

- The research questions that you address,

- The variables of interest [i.e., the various factors and features of the phenomenon being studied],

- The method(s) of investigation,

- The time period your study covers, and

- Any relevant alternative theoretical frameworks that could have been adopted.

Review each of these decisions. Not only do you clearly establish what you intend to accomplish in your research, but you should also include a declaration of what the study does not intend to cover. In the latter case, your exclusionary decisions should be based upon criteria understood as, "not interesting"; "not directly relevant"; “too problematic because..."; "not feasible," and the like. Make this reasoning explicit!

NOTE: Delimitations refer to the initial choices made about the broader, overall design of your study and should not be confused with documenting the limitations of your study discovered after the research has been completed.

ANOTHER NOTE : Do not view delimitating statements as admitting to an inherent failing or shortcoming in your research. They are an accepted element of academic writing intended to keep the reader focused on the research problem by explicitly defining the conceptual boundaries and scope of your study. It addresses any critical questions in the reader's mind of, "Why the hell didn't the author examine this?"

III. The Narrative Flow

Issues to keep in mind that will help the narrative flow in your introduction :

- Your introduction should clearly identify the subject area of interest . A simple strategy to follow is to use key words from your title in the first few sentences of the introduction. This will help focus the introduction on the topic at the appropriate level and ensures that you get to the subject matter quickly without losing focus, or discussing information that is too general.

- Establish context by providing a brief and balanced review of the pertinent published literature that is available on the subject. The key is to summarize for the reader what is known about the specific research problem before you did your analysis. This part of your introduction should not represent a comprehensive literature review--that comes next. It consists of a general review of the important, foundational research literature [with citations] that establishes a foundation for understanding key elements of the research problem. See the drop-down menu under this tab for " Background Information " regarding types of contexts.

- Clearly state the hypothesis that you investigated . When you are first learning to write in this format it is okay, and actually preferable, to use a past statement like, "The purpose of this study was to...." or "We investigated three possible mechanisms to explain the...."

- Why did you choose this kind of research study or design? Provide a clear statement of the rationale for your approach to the problem studied. This will usually follow your statement of purpose in the last paragraph of the introduction.

IV. Engaging the Reader

A research problem in the social sciences can come across as dry and uninteresting to anyone unfamiliar with the topic . Therefore, one of the goals of your introduction is to make readers want to read your paper. Here are several strategies you can use to grab the reader's attention:

- Open with a compelling story . Almost all research problems in the social sciences, no matter how obscure or esoteric , are really about the lives of people. Telling a story that humanizes an issue can help illuminate the significance of the problem and help the reader empathize with those affected by the condition being studied.

- Include a strong quotation or a vivid, perhaps unexpected, anecdote . During your review of the literature, make note of any quotes or anecdotes that grab your attention because they can used in your introduction to highlight the research problem in a captivating way.

- Pose a provocative or thought-provoking question . Your research problem should be framed by a set of questions to be addressed or hypotheses to be tested. However, a provocative question can be presented in the beginning of your introduction that challenges an existing assumption or compels the reader to consider an alternative viewpoint that helps establish the significance of your study.

- Describe a puzzling scenario or incongruity . This involves highlighting an interesting quandary concerning the research problem or describing contradictory findings from prior studies about a topic. Posing what is essentially an unresolved intellectual riddle about the problem can engage the reader's interest in the study.

- Cite a stirring example or case study that illustrates why the research problem is important . Draw upon the findings of others to demonstrate the significance of the problem and to describe how your study builds upon or offers alternatives ways of investigating this prior research.

NOTE: It is important that you choose only one of the suggested strategies for engaging your readers. This avoids giving an impression that your paper is more flash than substance and does not distract from the substance of your study.

Freedman, Leora and Jerry Plotnick. Introductions and Conclusions. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Introduction. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Introductions. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Introductions, Body Paragraphs, and Conclusions for an Argument Paper. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Resources for Writers: Introduction Strategies. Program in Writing and Humanistic Studies. Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Sharpling, Gerald. Writing an Introduction. Centre for Applied Linguistics, University of Warwick; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Swales, John and Christine B. Feak. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: Essential Skills and Tasks . 2nd edition. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2004 ; Writing Your Introduction. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University.

Writing Tip

Avoid the "Dictionary" Introduction

Giving the dictionary definition of words related to the research problem may appear appropriate because it is important to define specific terminology that readers may be unfamiliar with. However, anyone can look a word up in the dictionary and a general dictionary is not a particularly authoritative source because it doesn't take into account the context of your topic and doesn't offer particularly detailed information. Also, placed in the context of a particular discipline, a term or concept may have a different meaning than what is found in a general dictionary. If you feel that you must seek out an authoritative definition, use a subject specific dictionary or encyclopedia [e.g., if you are a sociology student, search for dictionaries of sociology]. A good database for obtaining definitive definitions of concepts or terms is Credo Reference .

Saba, Robert. The College Research Paper. Florida International University; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina.

Another Writing Tip

When Do I Begin?

A common question asked at the start of any paper is, "Where should I begin?" An equally important question to ask yourself is, "When do I begin?" Research problems in the social sciences rarely rest in isolation from history. Therefore, it is important to lay a foundation for understanding the historical context underpinning the research problem. However, this information should be brief and succinct and begin at a point in time that illustrates the study's overall importance. For example, a study that investigates coffee cultivation and export in West Africa as a key stimulus for local economic growth needs to describe the beginning of exporting coffee in the region and establishing why economic growth is important. You do not need to give a long historical explanation about coffee exports in Africa. If a research problem requires a substantial exploration of the historical context, do this in the literature review section. In your introduction, make note of this as part of the "roadmap" [see below] that you use to describe the organization of your paper.

Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Always End with a Roadmap

The final paragraph or sentences of your introduction should forecast your main arguments and conclusions and provide a brief description of the rest of the paper [the "roadmap"] that let's the reader know where you are going and what to expect. A roadmap is important because it helps the reader place the research problem within the context of their own perspectives about the topic. In addition, concluding your introduction with an explicit roadmap tells the reader that you have a clear understanding of the structural purpose of your paper. In this way, the roadmap acts as a type of promise to yourself and to your readers that you will follow a consistent and coherent approach to addressing the topic of inquiry. Refer to it often to help keep your writing focused and organized.

Cassuto, Leonard. “On the Dissertation: How to Write the Introduction.” The Chronicle of Higher Education , May 28, 2018; Radich, Michael. A Student's Guide to Writing in East Asian Studies . (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Writing n. d.), pp. 35-37.

- << Previous: Executive Summary

- Next: The C.A.R.S. Model >>

- Last Updated: Apr 16, 2024 10:20 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How to Write an Introduction for a Research Paper

Table of Contents

Writing an introduction for a research paper is a critical element of your paper, but it can seem challenging to encapsulate enormous amount of information into a concise form. The introduction of your research paper sets the tone for your research and provides the context for your study. In this article, we will guide you through the process of writing an effective introduction that grabs the reader's attention and captures the essence of your research paper.

Understanding the Purpose of a Research Paper Introduction

The introduction acts as a road map for your research paper, guiding the reader through the main ideas and arguments. The purpose of the introduction is to present your research topic to the readers and provide a rationale for why your study is relevant. It helps the reader locate your research and its relevance in the broader field of related scientific explorations. Additionally, the introduction should inform the reader about the objectives and scope of your study, giving them an overview of what to expect in the paper. By including a comprehensive introduction, you establish your credibility as an author and convince the reader that your research is worth their time and attention.

Key Elements to Include in Your Introduction

When writing your research paper introduction, there are several key elements you should include to ensure it is comprehensive and informative.

- A hook or attention-grabbing statement to capture the reader's interest. It can be a thought-provoking question, a surprising statistic, or a compelling anecdote that relates to your research topic.

- A brief overview of the research topic and its significance. By highlighting the gap in existing knowledge or the problem your research aims to address, you create a compelling case for the relevance of your study.

- A clear research question or problem statement. This serves as the foundation of your research and guides the reader in understanding the unique focus of your study. It should be concise, specific, and clearly articulated.

- An outline of the paper's structure and main arguments, to help the readers navigate through the paper with ease.

Preparing to Write Your Introduction

Before diving into writing your introduction, it is essential to prepare adequately. This involves 3 important steps:

- Conducting Preliminary Research: Immerse yourself in the existing literature to develop a clear research question and position your study within the academic discourse.

- Identifying Your Thesis Statement: Define a specific, focused, and debatable thesis statement, serving as a roadmap for your paper.

- Considering Broader Context: Reflect on the significance of your research within your field, understanding its potential impact and contribution.

By engaging in these preparatory steps, you can ensure that your introduction is well-informed, focused, and sets the stage for a compelling research paper.

Structuring Your Introduction

Now that you have prepared yourself to tackle the introduction, it's time to structure it effectively. A well-structured introduction will engage the reader from the beginning and provide a logical flow to your research paper.

Starting with a Hook

Begin your introduction with an attention-grabbing hook that captivates the reader's interest. This hook serves as a way to make your introduction more engaging and compelling. For example, if you are writing a research paper on the impact of climate change on biodiversity, you could start your introduction with a statistic about the number of species that have gone extinct due to climate change. This will immediately grab the reader's attention and make them realize the urgency and importance of the topic.

Introducing Your Topic

Provide a brief overview, which should give the reader a general understanding of the subject matter and its significance. Explain the importance of the topic and its relevance to the field. This will help the reader understand why your research is significant and why they should continue reading. Continuing with the example of climate change and biodiversity, you could explain how climate change is one of the greatest threats to global biodiversity, how it affects ecosystems, and the potential consequences for both wildlife and human populations. By providing this context, you are setting the stage for the rest of your research paper and helping the reader understand the importance of your study.

Presenting Your Thesis Statement

The thesis statement should directly address your research question and provide a preview of the main arguments or findings discussed in your paper. Make sure your thesis statement is clear, concise, and well-supported by the evidence you will present in your research paper. By presenting a strong and focused thesis statement, you are providing the reader with the information they could anticipate in your research paper. This will help them understand the purpose and scope of your study and will make them more inclined to continue reading.

Writing Techniques for an Effective Introduction

When crafting an introduction, it is crucial to pay attention to the finer details that can elevate your writing to the next level. By utilizing specific writing techniques, you can captivate your readers and draw them into your research journey.

Using Clear and Concise Language

One of the most important writing techniques to employ in your introduction is the use of clear and concise language. By choosing your words carefully, you can effectively convey your ideas to the reader. It is essential to avoid using jargon or complex terminology that may confuse or alienate your audience. Instead, focus on communicating your research in a straightforward manner to ensure that your introduction is accessible to both experts in your field and those who may be new to the topic. This approach allows you to engage a broader audience and make your research more inclusive.

Establishing the Relevance of Your Research

One way to establish the relevance of your research is by highlighting how it fills a gap in the existing literature. Explain how your study addresses a significant research question that has not been adequately explored. By doing this, you demonstrate that your research is not only unique but also contributes to the broader knowledge in your field. Furthermore, it is important to emphasize the potential impact of your research. Whether it is advancing scientific understanding, informing policy decisions, or improving practical applications, make it clear to the reader how your study can make a difference.

By employing these two writing techniques in your introduction, you can effectively engage your readers. Take your time to craft an introduction that is both informative and captivating, leaving your readers eager to delve deeper into your research.

Revising and Polishing Your Introduction

Once you have written your introduction, it is crucial to revise and polish it to ensure that it effectively sets the stage for your research paper.

Self-Editing Techniques

Review your introduction for clarity, coherence, and logical flow. Ensure each paragraph introduces a new idea or argument with smooth transitions.

Check for grammatical errors, spelling mistakes, and awkward sentence structures.

Ensure that your introduction aligns with the overall tone and style of your research paper.

Seeking Feedback for Improvement

Consider seeking feedback from peers, colleagues, or your instructor. They can provide valuable insights and suggestions for improving your introduction. Be open to constructive criticism and use it to refine your introduction and make it more compelling for the reader.

Writing an introduction for a research paper requires careful thought and planning. By understanding the purpose of the introduction, preparing adequately, structuring effectively, and employing writing techniques, you can create an engaging and informative introduction for your research. Remember to revise and polish your introduction to ensure that it accurately represents the main ideas and arguments in your research paper. With a well-crafted introduction, you will capture the reader's attention and keep them inclined to your paper.

Suggested Reads

ResearchGPT: A Custom GPT for Researchers and Scientists Best Academic Search Engines [2023] How To Humanize AI Text In Scientific Articles Elevate Your Writing Game With AI Grammar Checker Tools

You might also like

AI for Meta-Analysis — A Comprehensive Guide

Cybersecurity in Higher Education: Safeguarding Students and Faculty Data

How To Write An Argumentative Essay

How to write an effective introduction for your research paper

Last updated

20 January 2024

Reviewed by

However, the introduction is a vital element of your research paper. It helps the reader decide whether your paper is worth their time. As such, it's worth taking your time to get it right.

In this article, we'll tell you everything you need to know about writing an effective introduction for your research paper.

- The importance of an introduction in research papers

The primary purpose of an introduction is to provide an overview of your paper. This lets readers gauge whether they want to continue reading or not. The introduction should provide a meaningful roadmap of your research to help them make this decision. It should let readers know whether the information they're interested in is likely to be found in the pages that follow.

Aside from providing readers with information about the content of your paper, the introduction also sets the tone. It shows readers the style of language they can expect, which can further help them to decide how far to read.

When you take into account both of these roles that an introduction plays, it becomes clear that crafting an engaging introduction is the best way to get your paper read more widely. First impressions count, and the introduction provides that impression to readers.

- The optimum length for a research paper introduction

While there's no magic formula to determine exactly how long a research paper introduction should be, there are a few guidelines. Some variables that impact the ideal introduction length include:

Field of study

Complexity of the topic

Specific requirements of the course or publication

A commonly recommended length of a research paper introduction is around 10% of the total paper’s length. So, a ten-page paper has a one-page introduction. If the topic is complex, it may require more background to craft a compelling intro. Humanities papers tend to have longer introductions than those of the hard sciences.

The best way to craft an introduction of the right length is to focus on clarity and conciseness. Tell the reader only what is necessary to set up your research. An introduction edited down with this goal in mind should end up at an acceptable length.

- Evaluating successful research paper introductions

A good way to gauge how to create a great introduction is by looking at examples from across your field. The most influential and well-regarded papers should provide some insights into what makes a good introduction.

Dissecting examples: what works and why

We can make some general assumptions by looking at common elements of a good introduction, regardless of the field of research.

A common structure is to start with a broad context, and then narrow that down to specific research questions or hypotheses. This creates a funnel that establishes the scope and relevance.

The most effective introductions are careful about the assumptions they make regarding reader knowledge. By clearly defining key terms and concepts instead of assuming the reader is familiar with them, these introductions set a more solid foundation for understanding.

To pull in the reader and make that all-important good first impression, excellent research paper introductions will often incorporate a compelling narrative or some striking fact that grabs the reader's attention.

Finally, good introductions provide clear citations from past research to back up the claims they're making. In the case of argumentative papers or essays (those that take a stance on a topic or issue), a strong thesis statement compels the reader to continue reading.

Common pitfalls to avoid in research paper introductions

You can also learn what not to do by looking at other research papers. Many authors have made mistakes you can learn from.

We've talked about the need to be clear and concise. Many introductions fail at this; they're verbose, vague, or otherwise fail to convey the research problem or hypothesis efficiently. This often comes in the form of an overemphasis on background information, which obscures the main research focus.

Ensure your introduction provides the proper emphasis and excitement around your research and its significance. Otherwise, fewer people will want to read more about it.

- Crafting a compelling introduction for a research paper

Let’s take a look at the steps required to craft an introduction that pulls readers in and compels them to learn more about your research.

Step 1: Capturing interest and setting the scene

To capture the reader's interest immediately, begin your introduction with a compelling question, a surprising fact, a provocative quote, or some other mechanism that will hook readers and pull them further into the paper.

As they continue reading, the introduction should contextualize your research within the current field, showing readers its relevance and importance. Clarify any essential terms that will help them better understand what you're saying. This keeps the fundamentals of your research accessible to all readers from all backgrounds.

Step 2: Building a solid foundation with background information

Including background information in your introduction serves two major purposes:

It helps to clarify the topic for the reader

It establishes the depth of your research

The approach you take when conveying this information depends on the type of paper.

For argumentative papers, you'll want to develop engaging background narratives. These should provide context for the argument you'll be presenting.

For empirical papers, highlighting past research is the key. Often, there will be some questions that weren't answered in those past papers. If your paper is focused on those areas, those papers make ideal candidates for you to discuss and critique in your introduction.

Step 3: Pinpointing the research challenge

To capture the attention of the reader, you need to explain what research challenges you'll be discussing.

For argumentative papers, this involves articulating why the argument you'll be making is important. What is its relevance to current discussions or problems? What is the potential impact of people accepting or rejecting your argument?

For empirical papers, explain how your research is addressing a gap in existing knowledge. What new insights or contributions will your research bring to your field?

Step 4: Clarifying your research aims and objectives

We mentioned earlier that the introduction to a research paper can serve as a roadmap for what's within. We've also frequently discussed the need for clarity. This step addresses both of these.

When writing an argumentative paper, craft a thesis statement with impact. Clearly articulate what your position is and the main points you intend to present. This will map out for the reader exactly what they'll get from reading the rest.

For empirical papers, focus on formulating precise research questions and hypotheses. Directly link them to the gaps or issues you've identified in existing research to show the reader the precise direction your research paper will take.

Step 5: Sketching the blueprint of your study

Continue building a roadmap for your readers by designing a structured outline for the paper. Guide the reader through your research journey, explaining what the different sections will contain and their relationship to one another.

This outline should flow seamlessly as you move from section to section. Creating this outline early can also help guide the creation of the paper itself, resulting in a final product that's better organized. In doing so, you'll craft a paper where each section flows intuitively from the next.

Step 6: Integrating your research question

To avoid letting your research question get lost in background information or clarifications, craft your introduction in such a way that the research question resonates throughout. The research question should clearly address a gap in existing knowledge or offer a new perspective on an existing problem.

Tell users your research question explicitly but also remember to frequently come back to it. When providing context or clarification, point out how it relates to the research question. This keeps your focus where it needs to be and prevents the topic of the paper from becoming under-emphasized.

Step 7: Establishing the scope and limitations

So far, we've talked mostly about what's in the paper and how to convey that information to readers. The opposite is also important. Information that's outside the scope of your paper should be made clear to the reader in the introduction so their expectations for what is to follow are set appropriately.

Similarly, be honest and upfront about the limitations of the study. Any constraints in methodology, data, or how far your findings can be generalized should be fully communicated in the introduction.

Step 8: Concluding the introduction with a promise

The final few lines of the introduction are your last chance to convince people to continue reading the rest of the paper. Here is where you should make it very clear what benefit they'll get from doing so. What topics will be covered? What questions will be answered? Make it clear what they will get for continuing.

By providing a quick recap of the key points contained in the introduction in its final lines and properly setting the stage for what follows in the rest of the paper, you refocus the reader's attention on the topic of your research and guide them to read more.

- Research paper introduction best practices

Following the steps above will give you a compelling introduction that hits on all the key points an introduction should have. Some more tips and tricks can make an introduction even more polished.

As you follow the steps above, keep the following tips in mind.

Set the right tone and style

Like every piece of writing, a research paper should be written for the audience. That is to say, it should match the tone and style that your academic discipline and target audience expect. This is typically a formal and academic tone, though the degree of formality varies by field.

Kno w the audience

The perfect introduction balances clarity with conciseness. The amount of clarification required for a given topic depends greatly on the target audience. Knowing who will be reading your paper will guide you in determining how much background information is required.

Adopt the CARS (create a research space) model

The CARS model is a helpful tool for structuring introductions. This structure has three parts. The beginning of the introduction establishes the general research area. Next, relevant literature is reviewed and critiqued. The final section outlines the purpose of your study as it relates to the previous parts.

Master the art of funneling

The CARS method is one example of a well-funneled introduction. These start broadly and then slowly narrow down to your specific research problem. It provides a nice narrative flow that provides the right information at the right time. If you stray from the CARS model, try to retain this same type of funneling.

Incorporate narrative element

People read research papers largely to be informed. But to inform the reader, you have to hold their attention. A narrative style, particularly in the introduction, is a great way to do that. This can be a compelling story, an intriguing question, or a description of a real-world problem.

Write the introduction last

By writing the introduction after the rest of the paper, you'll have a better idea of what your research entails and how the paper is structured. This prevents the common problem of writing something in the introduction and then forgetting to include it in the paper. It also means anything particularly exciting in the paper isn’t neglected in the intro.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

How to Write an Introduction for a Research Paper

How to write an introduction for a research paper? Eventually (and with practice) all writers will develop their own strategy for writing the perfect introduction for a research paper. Once you are comfortable with writing, you will probably find your own, but coming up with a good strategy can be tough for beginning writers.

The Purpose of an Introduction

Your opening paragraphs, phrases for introducing thesis statements, research paper introduction examples, using the introduction to map out your research paper.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

- First write your thesis.Your thesis should state the main idea in specific terms.

- After you have a working thesis, tackle the body of your paper before you write the rest of the introduction. Each paragraph in the body should explore one specific topic that proves, or summarizes your thesis. Writing is a thinking process. Once you have worked your way through that process by writing the body of the paper, you will have an intimate understanding of how you are supporting your thesis. After you have written the body paragraphs, go back and rewrite your thesis to make it more specific and to connect it to the topics you addressed in the body paragraph.

- Revise your introduction several times, saving each revision. Be sure your introduction previews the topics you are presenting in your paper. One way of doing this is to use keywords from the topic sentences in each paragraph to introduce, or preview, the topics in your introduction.This “preview” will give your reader a context for understanding how you will make your case.

- Experiment by taking different approaches to your thesis with every revision you make. Play with the language in the introduction. Strike a new tone. Go back and compare versions. Then pick the one that works most effectively with the body of your research paper.

- Do not try to pack everything you want to say into your introduction. Just as your introduction should not be too short, it should also not be too long. Your introduction should be about the same length as any other paragraph in your research paper. Let the content—what you have to say—dictate the length.

The first page of your research paper should draw the reader into the text. It is the paper’s most important page and, alas, often the worst written. There are two culprits here and effective ways to cope with both of them.

First, the writer is usually straining too hard to say something terribly BIG and IMPORTANT about the thesis topic. The goal is worthy, but the aim is unrealistically high. The result is often a muddle of vague platitudes rather than a crisp, compelling introduction to the thesis. Want a familiar example? Listen to most graduation speakers. Their goal couldn’t be loftier: to say what education means and to tell an entire football stadium how to live the rest of their lives. The results are usually an avalanche of clichés and sodden prose.

The second culprit is bad timing. The opening and concluding paragraphs are usually written late in the game, after the rest of the thesis is finished and polished. There’s nothing wrong with writing these sections last. It’s usually the right approach since you need to know exactly what you are saying in the substantive middle sections of the thesis before you can introduce them effectively or draw together your findings. But having waited to write the opening and closing sections, you need to review and edit them several times to catch up. Otherwise, you’ll putting the most jagged prose in the most tender spots. Edit and polish your opening paragraphs with extra care. They should draw readers into the paper.

After you’ve done some extra polishing, I suggest a simple test for the introductory section. As an experiment, chop off the first few paragraphs. Let the paper begin on, say, paragraph 2 or even page 2. If you don’t lose much, or actually gain in clarity and pace, then you’ve got a problem.

There are two solutions. One is to start at this new spot, further into the text. After all, that’s where you finally gain traction on your subject. That works best in some cases, and we occasionally suggest it. The alternative, of course, is to write a new opening that doesn’t flop around, saying nothing.

What makes a good opening? Actually, they come in several flavors. One is an intriguing story about your topic. Another is a brief, compelling quote. When you run across them during your reading, set them aside for later use. Don’t be deterred from using them because they “don’t seem academic enough.” They’re fine as long as the rest of the paper doesn’t sound like you did your research in People magazine. The third, and most common, way to begin is by stating your main questions, followed by a brief comment about why they matter.

Whichever opening you choose, it should engage your readers and coax them to continue. Having done that, you should give them a general overview of the project—the main issues you will cover, the material you will use, and your thesis statement (that is, your basic approach to the topic). Finally, at the end of the introductory section, give your readers a brief road map, showing how the paper will unfold. How you do that depends on your topic but here are some general suggestions for phrase choice that may help:

- This analysis will provide …

- This paper analyzes the relationship between …

- This paper presents an analysis of …

- This paper will argue that …

- This topic supports the argument that…

- Research supports the opinion that …

- This paper supports the opinion that …

- An interpretation of the facts indicates …

- The results of this experiment show …

- The results of this research show …

Comparisons/Contrasts

- A comparison will show that …

- By contrasting the results,we see that …

- This paper examines the advantages and disadvantages of …

Definitions/Classifications

- This paper will provide a guide for categorizing the following:…

- This paper provides a definition of …

- This paper explores the meaning of …

- This paper will discuss the implications of …

- A discussion of this topic reveals …

- The following discussion will focus on …

Description

- This report describes…

- This report will illustrate…

- This paper provides an illustration of …

Process/Experimentation

- This paper will identify the reasons behind…

- The results of the experiment show …

- The process revealed that …

- This paper theorizes…

- This paper presents the theory that …

- In theory, this indicates that …

Quotes, anecdotes, questions, examples, and broad statements—all of them can used successfully to write an introduction for a research paper. It’s instructive to see them in action, in the hands of skilled academic writers.

Let’s begin with David M. Kennedy’s superb history, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 . Kennedy begins each chapter with a quote, followed by his text. The quote above chapter 1 shows President Hoover speaking in 1928 about America’s golden future. The text below it begins with the stock market collapse of 1929. It is a riveting account of just how wrong Hoover was. The text about the Depression is stronger because it contrasts so starkly with the optimistic quotation.

“We in America today are nearer the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land.”—Herbert Hoover, August 11, 1928 Like an earthquake, the stock market crash of October 1929 cracked startlingly across the United States, the herald of a crisis that was to shake the American way of life to its foundations. The events of the ensuing decade opened a fissure across the landscape of American history no less gaping than that opened by the volley on Lexington Common in April 1775 or by the bombardment of Sumter on another April four score and six years later. The ratcheting ticker machines in the autumn of 1929 did not merely record avalanching stock prices. In time they came also to symbolize the end of an era. (David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 . New York: Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 10)

Kennedy has exciting, wrenching material to work with. John Mueller faces the exact opposite problem. In Retreat from Doomsday: The Obsolescence of Major War , he is trying to explain why Great Powers have suddenly stopped fighting each other. For centuries they made war on each other with devastating regularity, killing millions in the process. But now, Mueller thinks, they have not just paused; they have stopped permanently. He is literally trying to explain why “nothing is happening now.” That may be an exciting topic intellectually, it may have great practical significance, but “nothing happened” is not a very promising subject for an exciting opening paragraph. Mueller manages to make it exciting and, at the same time, shows why it matters so much. Here’s his opening, aptly entitled “History’s Greatest Nonevent”:

On May 15, 1984, the major countries of the developed world had managed to remain at peace with each other for the longest continuous stretch of time since the days of the Roman Empire. If a significant battle in a war had been fought on that day, the press would have bristled with it. As usual, however, a landmark crossing in the history of peace caused no stir: the most prominent story in the New York Times that day concerned the saga of a manicurist, a machinist, and a cleaning woman who had just won a big Lotto contest. This book seeks to develop an explanation for what is probably the greatest nonevent in human history. (John Mueller, Retreat from Doomsday: The Obsolescence of Major War . New York: Basic Books, 1989, p. 3)

In the space of a few sentences, Mueller sets up his puzzle and reveals its profound human significance. At the same time, he shows just how easy it is to miss this milestone in the buzz of daily events. Notice how concretely he does that. He doesn’t just say that the New York Times ignored this record setting peace. He offers telling details about what they covered instead: “a manicurist, a machinist, and a cleaning woman who had just won a big Lotto contest.” Likewise, David Kennedy immediately entangles us in concrete events: the stunning stock market crash of 1929. These are powerful openings that capture readers’ interests, establish puzzles, and launch narratives.