- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Three techniques for...

Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies

- Related content

- Peer review

- Alicia O’Cathain , professor 1 ,

- Elizabeth Murphy , professor 2 ,

- Jon Nicholl , professor 1

- 1 Medical Care Research Unit, School of Health and Related Research, University of Sheffield, Sheffield S1 4DA, UK

- 2 University of Leicester, Leicester, UK

- Correspondence to: A O’Cathain a.ocathain{at}sheffield.ac.uk

- Accepted 8 June 2010

Techniques designed to combine the results of qualitative and quantitative studies can provide researchers with more knowledge than separate analysis

Health researchers are increasingly using designs that combine qualitative and quantitative methods, and this is often called mixed methods research. 1 Integration—the interaction or conversation between the qualitative and quantitative components of a study—is an important aspect of mixed methods research, and, indeed, is essential to some definitions. 2 Recent empirical studies of mixed methods research in health show, however, a lack of integration between components, 3 4 which limits the amount of knowledge that these types of studies generate. Without integration, the knowledge yield is equivalent to that from a qualitative study and a quantitative study undertaken independently, rather than achieving a “whole greater than the sum of the parts.” 5

Barriers to integration have been identified in both health and social research. 6 7 One barrier is the absence of formal education in mixed methods research. Fortunately, literature is rapidly expanding to fill this educational gap, including descriptions of how to integrate data and findings from qualitative and quantitative methods. 8 9 In this article we outline three techniques that may help health researchers to integrate data or findings in their mixed methods studies and show how these might enhance knowledge generated from this approach.

Triangulation protocol

Researchers will often use qualitative and quantitative methods to examine different aspects of an overall research question. For example, they might use a randomised controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of a healthcare intervention and semistructured interviews with patients and health professionals to consider the way in which the intervention was used in the real world. Alternatively, they might use a survey of service users to measure satisfaction with a service and focus groups to explore views of care in more depth. Data are collected and analysed separately for each component to produce two sets of findings. Researchers will then attempt to combine these findings, sometimes calling this process triangulation. The term triangulation can be confusing because it has two meanings. 10 It can be used to describe corroboration between two sets of findings or to describe a process of studying a problem using different methods to gain a more complete picture. The latter meaning is commonly used in mixed methods research and is the meaning used here.

The process of triangulating findings from different methods takes place at the interpretation stage of a study when both data sets have been analysed separately (figure ⇓ ). Several techniques have been described for triangulating findings. They require researchers to list the findings from each component of a study on the same page and consider where findings from each method agree (convergence), offer complementary information on the same issue (complementarity), or appear to contradict each other (discrepancy or dissonance). 11 12 13 Explicitly looking for disagreements between findings from different methods is an important part of this process. Disagreement is not a sign that something is wrong with a study. Exploration of any apparent “inter-method discrepancy” may lead to a better understanding of the research question, 14 and a range of approaches have been used within health services research to explore inter-method discrepancy. 15

Point of application for three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods research

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

The most detailed description of how to carry out triangulation is the triangulation protocol, 11 which although developed for multiple qualitative methods, is relevant to mixed methods studies. This technique involves producing a “convergence coding matrix” to display findings emerging from each component of a study on the same page. This is followed by consideration of where there is agreement, partial agreement, silence, or dissonance between findings from different components. This technique for triangulation is the only one to include silence—where a theme or finding arises from one data set and not another. Silence might be expected because of the strengths of different methods to examine different aspects of a phenomenon, but surprise silences might also arise that help to increase understanding or lead to further investigations.

The triangulation protocol moves researchers from thinking about the findings related to each method, to what Farmer and colleagues call meta-themes that cut across the findings from different methods. 11 They show a worked example of triangulation protocol, but we could find no other published example. However, similar principles were used in an iterative mixed methods study to understand patient and carer satisfaction with a new primary angioplasty service. 16 Researchers conducted semistructured interviews with 16 users and carers to explore their experiences and views of the new service. These were used to develop a questionnaire for a survey of 595 patients (and 418 of their carers) receiving either the new service or usual care. Finally, 17 of the patients who expressed dissatisfaction with aftercare and rehabilitation were followed up to explore this further in semistructured interviews. A shift of thinking to meta-themes led the researchers away from reporting the findings from the interviews, survey, and follow-up interviews sequentially to consider the meta-themes of speed and efficiency, convenience of care, and discharge and after care. The survey identified that a higher percentage of carers of patients using the new service rated the convenience of visiting the hospital as poor than those using usual care. The interviews supported this concern about the new service, but also identified that the weight carers gave to this concern was low in the context of their family member’s life being saved.

Morgan describes this move as the “third effort” because it occurs after analysis of the qualitative and the quantitative components. 17 It requires time and energy that must be planned into the study timetable. It is also useful to consider who will carry out the integration process. Farmer and colleagues require two researchers to work together during triangulation, which can be particularly important in mixed methods studies if different researchers take responsibility for the qualitative and quantitative components. 11

Following a thread

Moran-Ellis and colleagues describe a different technique for integrating the findings from the qualitative and quantitative components of a study, called following a thread. 18 They state that this takes place at the analysis stage of the research process (figure ⇑ ). It begins with an initial analysis of each component to identify key themes and questions requiring further exploration. Then the researchers select a question or theme from one component and follow it across the other components—they call this the thread. The authors do not specify steps in this technique but offer a visual model for working between datasets. An approach similar to this has been undertaken in health services research, although the researchers did not label it as such, probably because the technique has not been used frequently in the literature (box)

An example of following a thread 19

Adamson and colleagues explored the effect of patient views on the appropriate use of services and help seeking using a survey of people registered at a general practice and semistructured interviews. The qualitative (22 interviews) and quantitative components (survey with 911 respondents) took place concurrently.

The researchers describe what they call an iterative or cyclical approach to analysis. Firstly, the preliminary findings from the interviews generated a hypothesis for testing in the survey data. A key theme from the interviews concerned the self rationing of services as a responsible way of using scarce health care. This theme was then explored in the survey data by testing the hypothesis that people’s views of the appropriate use of services would explain their help seeking behaviour. However, there was no support for this hypothesis in the quantitative analysis because the half of survey respondents who felt that health services were used inappropriately were as likely to report help seeking for a series of symptoms presented in standardised vignettes as were respondents who thought that services were not used inappropriately. The researchers then followed the thread back to the interview data to help interpret this finding.

After further analysis of the interview data the researchers understood that people considered the help seeking of other people to be inappropriate, rather than their own. They also noted that feeling anxious about symptoms was considered to be a good justification for seeking care. The researchers followed this thread back into the survey data and tested whether anxiety levels about the symptoms in the standardised vignettes predicted help seeking behaviour. This second hypothesis was supported by the survey data. Following a thread led the researchers to conclude that patients who seek health care for seemingly minor problems have exceeded their thresholds for the trade-off between not using services inappropriately and any anxiety caused by their symptoms.

Mixed methods matrix

A unique aspect of some mixed methods studies is the availability of both qualitative and quantitative data on the same cases. Data from the qualitative and quantitative components can be integrated at the analysis stage of a mixed methods study (figure ⇑ ). For example, in-depth interviews might be carried out with a sample of survey respondents, creating a subset of cases for which there is both a completed questionnaire and a transcript. Cases may be individuals, groups, organisations, or geographical areas. 9 All the data collected on a single case can be studied together, focusing attention on cases, rather than variables or themes, within a study. The data can be examined in detail for each case—for example, comparing people’s responses to a questionnaire with their interview transcript. Alternatively, data on each case can be summarised and displayed in a matrix 8 9 20 along the lines of Miles and Huberman’s meta-matrix. 21 Within a mixed methods matrix, the rows represent the cases for which there is both qualitative and quantitative data, and the columns display different data collected on each case. This allows researchers to pay attention to surprises and paradoxes between types of data on a single case and then look for patterns across all cases 20 in a qualitative cross case analysis. 21

We used a mixed methods matrix to study the relation between types of team working and the extent of integration in mixed methods studies in health services research (table ⇓ ). 22 Quantitative data were extracted from the proposals, reports, and peer reviewed publications of 75 mixed methods studies, and these were analysed to describe the proportion of studies with integrated outputs such as mixed methods journal articles. Two key variables in the quantitative component were whether the study was assessed as attempting to integrate qualitative or quantitative data or findings and the type of publications produced. We conducted qualitative interviews with 20 researchers who had worked on some of these studies to explore how mixed methods research was practised, including how the team worked together.

Example of a mixed methods matrix for a study exploring the relationship between types of teams and integration between qualitative and quantitative components of studies* 22

- View inline

The shared cases between the qualitative and quantitative components were 21 mixed methods studies (because one interviewee had worked on two studies in the quantitative component). A matrix was formed with each of the 21 studies as a row. The first column of the matrix contained the study identification, the second column indicated whether integration had occurred in that project, and the third column the score for integration of publications emerging from the study. The rows were then ordered to show the most integrated cases first. This ordering of rows helped us to see patterns across rows.

The next columns were themes from the qualitative interview with a researcher from that project. For example, the first theme was about the expertise in qualitative research within the team and whether the interviewee reported this as adequate for the study. The matrix was then used in the context of the qualitative analysis to explore the issues that affected integration. In particular, it helped to identify negative cases (when someone in the analysis doesn’t fit with the conclusions the analysis is coming to) within the qualitative analysis to facilitate understanding. Interviewees reported the need for experienced qualitative researchers on mixed methods studies to ensure that the qualitative component was published, yet two cases showed that this was neither necessary nor sufficient. This pushed us to explore other factors in a research team that helped generate outputs, and integrated outputs, from a mixed methods study.

Themes from a qualitative study can be summarised to the point where they are coded into quantitative data. In the matrix (table ⇑ ), the interviewee’s perception of the adequacy of qualitative expertise on the team could have been coded as adequate=1 or not=2. This is called “quantitising” of qualitative data 23 ; coded data can then be analysed with data from the quantitative component. This technique has been used to great effect in healthcare research to identify the discrepancy between health improvement assessed using quantitative measures and with in-depth interviews in a randomised controlled trial. 24

We have presented three techniques for integration in mixed methods research in the hope that they will inspire researchers to explore what can be learnt from bringing together data from the qualitative and quantitative components of their studies. Using these techniques may give the process of integration credibility rather than leaving researchers feeling that they have “made things up.” It may also encourage researchers to describe their approaches to integration, allowing them to be transparent and helping them to develop, critique, and improve on these techniques. Most importantly, we believe it may help researchers to generate further understanding from their research.

We have presented integration as unproblematic, but it is not. It may be easier for single researchers to use these techniques than a large research team. Large teams will need to pay attention to team dynamics, considering who will take responsibility for integration and who will be taking part in the process. In addition, we have taken a technical stance here rather than paying attention to different philosophical beliefs that may shape approaches to integration. We consider that these techniques would work in the context of a pragmatic or subtle realist stance adopted by some mixed methods researchers. 25 Finally, it is important to remember that these techniques are aids to integration and are helpful only when applied with expertise.

Summary points

Health researchers are increasingly using designs which combine qualitative and quantitative methods

However, there is often lack of integration between methods

Three techniques are described that can help researchers to integrate data from different components of a study: triangulation protocol, following a thread, and the mixed methods matrix

Use of these methods will allow researchers to learn more from the information they have collected

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;341:c4587

Funding: Medical Research Council grant reference G106/1116

Competing interests: All authors have completed the unified competing interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare financial support for the submitted work from the Medical Research Council; no financial relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; no spouses, partners, or children with relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; and no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Contributors: AOC wrote the paper. JN and EM contributed to drafts and all authors agreed the final version. AOC is guarantor.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- ↵ Lingard L, Albert M, Levinson W. Grounded theory, mixed methods and action research. BMJ 2008 ; 337 : a567 . OpenUrl FREE Full Text

- ↵ Creswell JW, Fetters MD, Ivankova NV. Designing a mixed methods study in primary care. Ann Fam Med 2004 ; 2 : 7 -12. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Lewin S, Glenton C, Oxman AD. Use of qualitative methods alongside randomised controlled trials of complex healthcare interventions: methodological study. BMJ 2009 ; 339 : b3496 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ O’Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. Integration and publications as indicators of ‘yield’ from mixed methods studies. J Mix Methods Res 2007 ; 1 : 147 -63. OpenUrl CrossRef Web of Science

- ↵ Barbour RS. The case for combining qualitative and quantitative approaches in health services research. J Health Serv Res Policy 1999 ; 4 : 39 -43. OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ O’Cathain A, Nicholl J, Murphy E. Structural issues affecting mixed methods studies in health research: a qualitative study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009 ; 9 : 82 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Bryman A. Barriers to integrating quantitative and qualitative research. J Mix Methods Res 2007 ; 1 : 8 -22. OpenUrl CrossRef

- ↵ Creswell JW, Plano-Clark V. Designing and conducting mixed methods research . Sage, 2007 .

- ↵ Bazeley P. Analysing mixed methods data. In: Andrew S, Halcomb EJ, eds. Mixed methods research for nursing and the health sciences . Wiley-Blackwell, 2009 :84-118.

- ↵ Sandelowski M. Triangles and crystals: on the geometry of qualitative research. Res Nurs Health 1995 ; 18 : 569 -74. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Farmer T, Robinson K, Elliott SJ, Eyles J. Developing and implementing a triangulation protocol for qualitative health research. Qual Health Res 2006 ; 16 : 377 -94. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Foster RL. Addressing the epistemologic and practical issues in multimethod research: a procedure for conceptual triangulation. Adv Nurs Sci 1997 ; 20 : 1 -12. OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Erzerberger C, Prein G. Triangulation: validity and empirically based hypothesis construction. Qual Quant 1997 ; 31 : 141 -54. OpenUrl CrossRef Web of Science

- ↵ Fielding NG, Fielding JL. Linking data . Sage, 1986 .

- ↵ Moffatt S, White M, Mackintosh J, Howel D. Using quantitative and qualitative data in health services research—what happens when mixed method findings conflict? BMC Health Serv Res 2006 ; 6 : 28 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Sampson FC, O’Cathain A, Goodacre S. Is primary angioplasty an acceptable alternative to thrombolysis? Quantitative and qualitative study of patient and carer satisfaction. Health Expectations (forthcoming).

- ↵ Morgan DL. Practical strategies for combining qualitative and quantitative methods: applications to health research. Qual Health Res 1998 ; 8 : 362 -76. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Moran-Ellis J, Alexander VD, Cronin A, Dickinson M, Fielding J, Sleney J, et al. Triangulation and integration: processes, claims and implications. Qualitative Research 2006 ; 6 : 45 -59. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Adamson J, Ben-Shlomo Y, Chaturvedi N, Donovan J. Exploring the impact of patient views on ‘appropriate’ use of services and help seeking: a mixed method study. Br J Gen Pract 2009 ; 59 : 496 -502. OpenUrl Web of Science

- ↵ Wendler MC. Triangulation using a meta-matrix. J Adv Nurs 2001 ; 35 : 521 -5. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Miles M, Huberman A. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook . Sage, 1994 .

- ↵ O’Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. Multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary or dysfunctional? Team working in mixed methods research. Qual Health Res 2008 ; 18 : 1574 -85. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Sandelowski M. Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and analysis techniques in mixed-method studies. Res Nurs Health 2000 ; 23 : 246 -55. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Campbell R, Quilty B, Dieppe P. Discrepancies between patients’ assessments of outcome: qualitative study nested within a randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2003 ; 326 : 252 -3. OpenUrl FREE Full Text

- ↵ Mays N, Pope C. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 2000 ; 320 : 50 -2. OpenUrl FREE Full Text

The Use of Mixed Methods in Research

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 13 January 2019

- Cite this reference work entry

- Kate A. McBride 2 ,

- Freya MacMillan 3 ,

- Emma S. George 4 &

- Genevieve Z. Steiner 5

2511 Accesses

9 Citations

Mixed methods research is becoming increasingly popular and is widely acknowledged as a means of achieving a more complex understanding of research problems. Combining both the in-depth, contextual views of qualitative research with the broader generalizations of larger population quantitative approaches, mixed methods research can be used to produce a rigorous and credible source of data. Using this methodology, the same core issue is investigated through the collection, analysis, and interpretation of both types of data within one study or a series of studies. Multiple designs are possible and can be guided by philosophical assumptions. Both qualitative and quantitative data can be collected simultaneously or sequentially (in any order) through a multiphase project. Integration of the two data sources then occurs with consideration is given to the weighting of both sources; these can either be equal or one can be prioritized over the other. Designed as a guide for novice mixed methods researchers, this chapter gives an overview of the historical and philosophical roots of mixed methods research. We also provide a practical overview of its application in health research as well as pragmatic considerations for those wishing to undertake mixed methods research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Appleton JV, King L. Journeying from the philosophical contemplation of constructivism to the methodological pragmatics of health services research. J Adv Nurs. 2002;40(6):641–8.

Article Google Scholar

Baba CT, Oliveira IM, Silva AEF, Vieira LM, Cerri NC, Florindo AA, de Oliveira Gomes GA. Evaluating the impact of a walking program in a disadvantaged area: using the RE-AIM framework by mixed methods. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):709. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4698-5 .

Bryman A. The research question in social research: what is its role? Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2007;10(1):5–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570600655282 .

Bryman A. The end of the paradigm wars. In: Alasuutari P, Bickman L, Brannen J, editors. The Sage handbook of social research methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2008. p. 13–25.

Google Scholar

Caracelli VJ, Greene JC. Data-analysis strategies for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 1993;15(2):195–207. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737015002195 .

Castro FG, Kellison JG, Boyd SJ, Kopak A. A methodology for conducting integrative mixed methods research and data analyses. J Mixed Methods Res. 2010;4(4):342–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689810382916 .

Center for Innovation in Teaching in Research. Choosing a mixed methods design. 2017. Retrieved 15 Nov 2017 from https://cirt.gcu.edu/research/developmentresources/research_ready/mixed_methods/choosing_design .

Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2018.

Curry LA, Krumholz HM, O’Cathain A, Clark VLP, Cherlin E, Bradley EH. Mixed methods in biomedical and health services research. Circ-Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(1):119–23. https://doi.org/10.1161/circoutcomes.112.967885 .

Denscombe M. Communities of practice: a research paradigm for the mixed methods approach. J Mixed Methods Res. 2008;2(3):270–83.

Doyle L, Brady A-M, Byrne G. An overview of mixed methods research. J Res Nurs. 2009;14(2):175–85.

Foster NE, Bishop A, Bartlam B, Ogollah R, Barlas P, Holden M, … Young J. Evaluating acupuncture and standard carE for pregnant women with back pain (EASE back): a feasibility study and pilot randomised trial. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(33):1–236. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta20330 .

Haider AH, Schneider EB, Kodadek LM, Adler RR, Ranjit A, Torain M, … Lau BD. Emergency department query for patient-centered approaches to sexual orientation and gender identity the EQUALITY study. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):819–828. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0906 .

Harding KE, Taylor NF, Bowers B, Stafford M, Leggat SG. Clinician and patient perspectives of a new model of triage in a community rehabilitation program that reduced waiting time: a qualitative analysis. Aust Health Rev. 2013;37(3):324–30. https://doi.org/10.1071/ah13033 .

Hoddinott P, Britten J, Prescott GJ, Tappin D, Ludbrook A, Godden DJ. Effectiveness of policy to provide breastfeeding groups ( BIG) for pregnant and breastfeeding mothers in primary care: cluster randomised controlled trial. Br Med J. 2009;338:a3026, 10. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a3026 .

Ivankova NV, Creswell JW, Stick SL. Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: from theory to practice. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822x05282260 .

Johnson B, Gray R. A history of philosophical and theoretical issues for mixed methods research. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. Sage handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2010. p. 69–94.

Chapter Google Scholar

Johnson BR, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Mixed methods research: a research paradigm whose time has come. Educ Res. 2004;33(7):14–26. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x033007014 .

Keeney S, McKenna H, Fleming P, McIlfatrick S. Attitudes to cancer and cancer prevention: what do people aged 35–54 years think? Eur J Cancer Care. 2010;19(6):769–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01137.x .

McBride KA, Ballinger ML, Schlub TE, Young MA, Tattersall MHN, Kirk J, et al. Psychosocial morbidity in TP53 mutation carriers: is whole-body cancer screening beneficial? Familial Cancer. 2017;16(3):423–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-016-9964-7 .

Mertens DM. Transformative mixed methods: addressing inequities. Am Behav Sci. 2012;56(6):802–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764211433797 .

Moffatt S, White M, Mackintosh J, Howel D. Using quantitative and qualitative data in health services research – what happens when mixed method findings conflict? BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:28. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-6-28 .

Morse JM. Approaches to qualitative-quantitative methodological triangulation. Nurs Res. 1991a;40(2):120–3.

Morse JM. Principles of mixed methods and multimethod research design. In: Tashakkori A, Teddilie C, editors. SAGE handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1991b.

Mutrie N, Doolin O, Fitzsimons CF, Grant PM, Granat M, Grealy M, et al. Increasing older adults’ walking through primary care: results of a pilot randomized controlled trial. Fam Pract. 2012;29(6):633–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cms038 .

Newman I, Ridenour C, Newman C, De Marco G. A typology of research purposes and its relationship to mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2003. p. 167–88.

O’Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. The quality of mixed methods studies in health services research. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008;13(2):92–8. https://doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2007.007074 .

Onwuegbuzie AJ, Collins KMT. A typology of mixed methods sampling designs in social science research. Qual Rep. 2007;12(2):281–316.

Plano Clark VL, Badiee M. Research questions in mixed methods research. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. SAGE handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2010. p. 275–304.

Prades, J., Algara, M., Espinas, J. A., Farrus, B., Arenas, M., Reyes, V., . . . Borras, J. M. (2017). Understanding variations in the use of hypofractionated radiotherapy and its specific indications for breast cancer: a mixed-methods study. Radiother Oncol, 123(1), 22–28. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2017.01.014 .

Tariq S, Woodman J. Using mixed methods in health research. JRSM Short Rep. 2013; 4 (6):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042533313479197 .

Tashakkori A, Creswell JW. Editorial: the new era of mixed methods. J Mixed Methods Res. 2007;1(1):3–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/2345678906293042 .

Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. The past and future of mixed methods research: from data triangulation to mixed model designs. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2003. p. 671–701.

Teddlie C, Tashakkori A. Foundations of mixed methods research: integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2009.

Teddlie C, Yu F. Mixed methods sampling a typology with examples. J Mixed Methods Res. 2007;1(1):77–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/2345678906292430 .

Wellard SJ, Rasmussen B, Savage S, Dunning T. Exploring staff diabetes medication knowledge and practices in regional residential care: triangulation study. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(13–14):1933–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12043 .

Zhang W. Mixed methods application in health intervention research: a multiple case study. Int J Mult Res Approaches. 2014;8(1):24–35. https://doi.org/10.5172/mra.2014.8.1.24 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Medicine and Translational Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Kate A. McBride

School of Science and Health and Translational Health Research Institute (THRI), Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia

Freya MacMillan

School of Science and Health, Western Sydney University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Emma S. George

NICM and Translational Health Research Institute (THRI), Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia

Genevieve Z. Steiner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kate A. McBride .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Science and Health, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia

Pranee Liamputtong

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

McBride, K.A., MacMillan, F., George, E.S., Steiner, G.Z. (2019). The Use of Mixed Methods in Research. In: Liamputtong, P. (eds) Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_97

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_97

Published : 13 January 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-10-5250-7

Online ISBN : 978-981-10-5251-4

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 3: Developing a Research Question

3.5 Quantitative, Qualitative, & Mixed Methods Research Approaches

Generally speaking, qualitative and quantitative approaches are the most common methods utilized by researchers. While these two approaches are often presented as a dichotomy, in reality it is much more complicated. Certainly, there are researchers who fall on the more extreme ends of these two approaches, however most recognize the advantages and usefulness of combining both methods (mixed methods). In the following sections we look at quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methodological approaches to undertaking research. Table 2.3 synthesizes the differences between quantitative and qualitative research approaches.

Quantitative Research Approaches

A quantitative approach to research is probably the most familiar approach for the typical research student studying at the introductory level. Arising from the natural sciences, e.g., chemistry and biology), the quantitative approach is framed by the belief that there is one reality or truth that simply requires discovering, known as realism. Therefore, asking the “right” questions is key. Further, this perspective favours observable causes and effects and is therefore outcome-oriented. Typically, aggregate data is used to see patterns and “truth” about the phenomenon under study. True understanding is determined by the ability to predict the phenomenon.

Qualitative Research Approaches

On the other side of research approaches is the qualitative approach. This is generally considered to be the opposite of the quantitative approach. Qualitative researchers are considered phenomenologists, or human-centred researchers. Any research must account for the humanness, i.e., that they have thoughts, feelings, and experiences that they interpret of the participants. Instead of a realist perspective suggesting one reality or truth, qualitative researchers tend to favour the constructionist perspective: knowledge is created, not discovered, and there are multiple realities based on someone’s perspective. Specifically, a researcher needs to understand why, how and to whom a phenomenon applies. These aspects are usually unobservable since they are the thoughts, feelings and experiences of the person. Most importantly, they are a function of their perception of those things rather than what the outside researcher interprets them to be. As a result, there is no such thing as a neutral or objective outsider, as in the quantitative approach. Rather, the approach is generally process-oriented. True understanding, rather than information based on prediction, is based on understanding action and on the interpretive meaning of that action.

Table 3.3 Differences between quantitative and qualitative approaches (from Adjei, n.d).

Note: Researchers in emergency and safety professions are increasingly turning toward qualitative methods. Here is an interesting peer paper related to qualitative research in emergency care.

Qualitative Research in Emergency Care Part I: Research Principles and Common Applications by Choo, Garro, Ranney, Meisel, and Guthrie (2015)

Interview-based Qualitative Research in Emergency Care Part II: Data Collection, Analysis and Results Reporting.

Research Methods for the Social Sciences: An Introduction Copyright © 2020 by Valerie Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- News & Highlights

- Publications and Documents

- Postgraduate Education

- Browse Our Courses

- C/T Research Academy

- K12 Investigator Training

- Translational Innovator

- SMART IRB Reliance Request

- Biostatistics Consulting

- Regulatory Support

- Pilot Funding

- Informatics Program

- Community Engagement

- Diversity Inclusion

- Research Enrollment and Diversity

- Harvard Catalyst Profiles

Community Engagement Program

Supporting bi-directional community engagement to improve the relevance, quality, and impact of research.

- Getting Started

- Resources for Equity in Research

- Community-Engaged Student Practice Placement

- Maternal Health Equity

- Youth Mental Health

- Leadership and Membership

- Past Members

- Study Review Rubric

- Community Ambassador Initiative

- Implementation Science Working Group

- Past Webinars & Podcasts

- Policy Atlas

- Community Advisory Board

For more information:

Mixed methods research.

According to the National Institutes of Health , mixed methods strategically integrates or combines rigorous quantitative and qualitative research methods to draw on the strengths of each. Mixed method approaches allow researchers to use a diversity of methods, combining inductive and deductive thinking, and offsetting limitations of exclusively quantitative and qualitative research through a complementary approach that maximizes strengths of each data type and facilitates a more comprehensive understanding of health issues and potential resolutions.¹ Mixed methods may be employed to produce a robust description and interpretation of the data, make quantitative results more understandable, or understand broader applicability of small-sample qualitative findings.

Integration

This refers to the ways in which qualitative and quantitative research activities are brought together to achieve greater insight. Mixed methods is not simply having quantitative and qualitative data available or analyzing and presenting data findings separately. The integration process can occur during data collection, analysis, or in the presentation of results.

¹ NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research: Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences

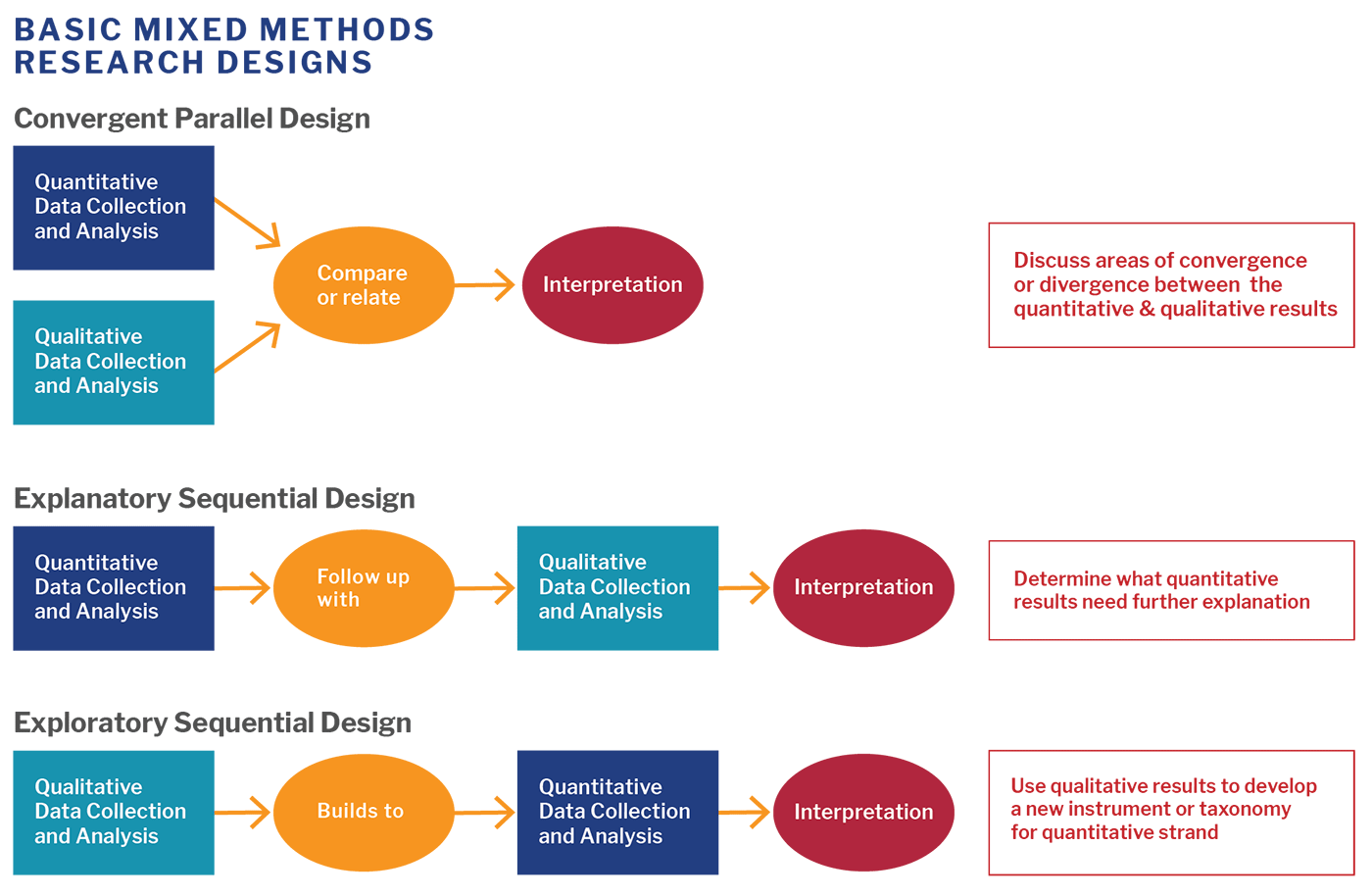

Basic Mixed Methods Research Designs

View image description .

Five Key Questions for Getting Started

- What do you want to know?

- What will be the detailed quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research questions that you hope to address?

- What quantitative and qualitative data will you collect and analyze?

- Which rigorous methods will you use to collect data and/or engage stakeholders?

- How will you integrate the data in a way that allows you to address the first question?

Rationale for Using Mixed Methods

- Obtain different, multiple perspectives: validation

- Build comprehensive understanding

- Explain statistical results in more depth

- Have better contextualized measures

- Track the process of program or intervention

- Study patient-centered outcomes and stakeholder engagement

Sample Mixed Methods Research Study

The EQUALITY study used an exploratory sequential design to identify the optimal patient-centered approach to collect sexual orientation data in the emergency department.

Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis : Semi-structured interviews with patients of different sexual orientation, age, race/ethnicity, as well as healthcare professionals of different roles, age, and race/ethnicity.

Builds Into : Themes identified in the interviews were used to develop questions for the national survey.

Quantitative Data Collection and Analysis : Representative national survey of patients and healthcare professionals on the topic of reporting gender identity and sexual orientation in healthcare.

Other Resources:

Introduction to Mixed Methods Research : Harvard Catalyst’s eight-week online course offers an opportunity for investigators who want to understand and apply a mixed methods approach to their research.

Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences [PDF] : This guide provides a detailed overview of mixed methods designs, best practices, and application to various types of grants and projects.

Mixed Methods Research Training Program for the Health Sciences (MMRTP ): Selected scholars for this summer training program, hosted by Johns Hopkins’ Bloomberg School of Public Health, have access to webinars, resources, a retreat to discuss their research project with expert faculty, and are matched with mixed methods consultants for ongoing support.

Michigan Mixed Methods : University of Michigan Mixed Methods program offers a variety of resources, including short web videos and recommended reading.

To use a mixed methods approach, you may want to first brush up on your qualitative skills. Below are a few helpful resources specific to qualitative research:

- Qualitative Research Guidelines Project : A comprehensive guide for designing, writing, reviewing and reporting qualitative research.

- Fundamentals of Qualitative Research Methods – What is Qualitative Research : A six-module web video series covering essential topics in qualitative research, including what is qualitative research and how to use the most common methods, in-depth interviews, and focus groups.

View PDF of the above information.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Mixed Methods Research – Types & Analysis

Mixed Methods Research – Types & Analysis

Table of Contents

Mixed Methods Research

Mixed methods research is an approach to research that combines both quantitative and qualitative research methods in a single study or research project. It is a methodological approach that involves collecting and analyzing both numerical (quantitative) and narrative (qualitative) data to gain a more comprehensive understanding of a research problem.

Types of Mixed Research

There are different types of mixed methods research designs that researchers can use, depending on the research question, the available data, and the resources available. Here are some common types:

Convergent Parallel Design

This design involves collecting both qualitative and quantitative data simultaneously, analyzing them separately, and then merging the findings to draw conclusions. The qualitative and quantitative data are given equal weight, and the findings are integrated during the interpretation phase.

Sequential Explanatory Design

In this design, the researcher collects and analyzes quantitative data first, and then uses qualitative data to explain or elaborate on the quantitative findings. The researcher may use the qualitative data to clarify unexpected or contradictory results from the quantitative analysis.

Sequential Exploratory Design

This design involves collecting qualitative data first, analyzing it, and then collecting and analyzing quantitative data to confirm or refute the qualitative findings. Qualitative data are used to generate hypotheses that are tested using quantitative data.

Concurrent Triangulation Design

This design involves collecting both qualitative and quantitative data concurrently and then comparing the results to find areas of agreement and disagreement. The findings are integrated during the interpretation phase to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the research question.

Concurrent Nested Design

This design involves collecting one type of data as the primary method and then using the other type of data to elaborate or clarify the primary data. For example, a researcher may use quantitative data as the primary method and qualitative data as a secondary method to provide more context and detail.

Transformative Design

This design involves using mixed methods research to not only understand the research question but also to bring about social change or transformation. The research is conducted in collaboration with stakeholders and aims to generate knowledge that can be used to improve policies, programs, and practices.

Concurrent Embedded Design

Concurrent embedded design is a type of mixed methods research design in which one type of data is embedded within another type of data. This design involves collecting both quantitative and qualitative data simultaneously, with one type of data being the primary method and the other type of data being the secondary method. The secondary method is embedded within the primary method, meaning that it is used to provide additional information or to clarify the primary data.

Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods used in mixed methods research:

Surveys are a common quantitative data collection method used in mixed methods research. Surveys involve collecting standardized responses to a set of questions from a sample of participants. Surveys can be conducted online, in person, or over the phone.

Interviews are a qualitative data collection method that involves asking open-ended questions to gather in-depth information about a participant’s experiences, perspectives, and opinions. Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or online.

Focus groups

Focus groups are a qualitative data collection method that involves bringing together a small group of participants to discuss a topic or research question. The group is facilitated by a researcher, and the discussion is recorded and analyzed for themes and patterns.

Observations

Observations are a qualitative data collection method that involves systematically watching and recording behavior in a natural setting. Observations can be structured or unstructured and can be used to gather information about behavior, interactions, and context.

Document Analysis

Document analysis is a qualitative data collection method that involves analyzing existing documents, such as reports, policy documents, or media articles. Document analysis can be used to gather information about trends, policy changes, or public attitudes.

Experimentation

Experimentation is a quantitative data collection method that involves manipulating one or more variables and measuring their effects on an outcome. Experiments can be conducted in a laboratory or in a natural setting.

Data Analysis Methods

Mixed methods research involves using both quantitative and qualitative data analysis methods to analyze data collected through different methods. Here are some common data analysis methods used in mixed methods research:

Quantitative Data Analysis

Quantitative data collected through surveys or experiments can be analyzed using statistical methods. Statistical analysis can be used to identify relationships between variables, test hypotheses, and make predictions. Common statistical methods used in quantitative data analysis include regression analysis, t-tests, ANOVA, and correlation analysis.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Qualitative data collected through interviews, focus groups, or observations can be analyzed using a variety of qualitative data analysis methods. These methods include content analysis, thematic analysis, narrative analysis, and grounded theory. Qualitative data analysis involves identifying themes and patterns in the data, interpreting the meaning of the data, and drawing conclusions based on the findings.

Integration of Data

The integration of quantitative and qualitative data involves combining the results from both types of data analysis to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the research question. Integration can involve either a concurrent or sequential approach. Concurrent integration involves analyzing quantitative and qualitative data at the same time, while sequential integration involves analyzing one type of data first and then using the results to inform the analysis of the other type of data.

Triangulation

Triangulation involves using multiple sources or types of data to validate or corroborate findings. This can involve using both quantitative and qualitative data or multiple qualitative methods. Triangulation can enhance the credibility and validity of the research findings.

Mixed Methods Meta-analysis

Mixed methods meta-analysis involves the systematic review and synthesis of findings from multiple studies that use mixed methods designs. This involves combining quantitative and qualitative data from multiple studies to gain a broader understanding of a research question.

How to conduct Mixed Methods Research

Here are some general steps for conducting mixed methods research:

- Identify the research problem: The first step is to clearly define the research problem and determine if mixed methods research is appropriate for addressing it.

- Design the study: The research design should include both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods. The specific design will depend on the research question and the purpose of the study.

- Collect data : Data collection involves collecting both qualitative and quantitative data through various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, and document analysis.

- Analyze data: Both qualitative and quantitative data need to be analyzed separately and then integrated. Analysis methods may include coding, statistical analysis, and thematic analysis.

- Interpret results: The results of the analysis should be interpreted, taking into account both the quantitative and qualitative findings. This involves integrating the results and identifying any patterns, themes, or discrepancies.

- Draw conclusions : Based on the interpretation of the results, conclusions should be drawn that address the research question and objectives.

- Report findings: Finally, the findings should be reported in a clear and concise manner, using both quantitative and qualitative data to support the conclusions.

Applications of Mixed Methods Research

Mixed methods research can be applied to a wide range of research fields and topics, including:

- Education : Mixed methods research can be used to evaluate educational programs, assess the effectiveness of teaching methods, and investigate student learning experiences.

- Health and social sciences: Mixed methods research can be used to study health interventions, understand the experiences of patients and their families, and assess the effectiveness of social programs.

- Business and management: Mixed methods research can be used to investigate customer satisfaction, assess the impact of marketing campaigns, and analyze the effectiveness of management strategies.

- Psychology : Mixed methods research can be used to explore the experiences and perspectives of individuals with mental health issues, investigate the impact of psychological interventions, and assess the effectiveness of therapy.

- Sociology : Mixed methods research can be used to study social phenomena, investigate the experiences and perspectives of marginalized groups, and assess the impact of social policies.

- Environmental studies: Mixed methods research can be used to assess the impact of environmental policies, investigate public perceptions of environmental issues, and analyze the effectiveness of conservation strategies.

Examples of Mixed Methods Research

Here are some examples of Mixed-Methods research:

- Evaluating a school-based mental health program: A researcher might use a concurrent embedded design to evaluate a school-based mental health program. The researcher might collect quantitative data through surveys and qualitative data through interviews with students and teachers. The quantitative data might be analyzed using statistical methods, while the qualitative data might be analyzed using thematic analysis. The results of the two types of data analysis could be integrated to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the program’s effectiveness.

- Understanding patient experiences of chronic illness: A researcher might use a sequential explanatory design to investigate patient experiences of chronic illness. The researcher might collect quantitative data through surveys and then use the results of the survey to inform the selection of participants for qualitative interviews. The qualitative data might be analyzed using content analysis to identify common themes in the patients’ experiences.

- Assessing the impact of a new public transportation system : A researcher might use a concurrent triangulation design to assess the impact of a new public transportation system. The researcher might collect quantitative data through surveys and qualitative data through focus groups with community members. The results of the two types of data analysis could be triangulated to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of the new transportation system on the community.

- Exploring teacher perceptions of technology integration in the classroom: A researcher might use a sequential exploratory design to investigate teacher perceptions of technology integration in the classroom. The researcher might collect qualitative data through in-depth interviews with teachers and then use the results of the interviews to develop a survey. The quantitative data might be analyzed using descriptive statistics to identify trends in teacher perceptions.

When to use Mixed Methods Research

Mixed methods research is typically used when a research question cannot be fully answered by using only quantitative or qualitative methods. Here are some common situations where mixed methods research is appropriate:

- When the research question requires a more comprehensive understanding than can be achieved by using only quantitative or qualitative methods.

- When the research question requires both an exploration of individuals’ experiences, perspectives, and attitudes, as well as the measurement of objective outcomes and variables.

- When the research question requires the examination of a phenomenon in its natural setting and context, which can be achieved by collecting rich qualitative data, as well as the generalization of findings to a larger population, which can be achieved through the use of quantitative methods.

- When the research question requires the integration of different types of data or perspectives, such as combining data collected from participants with data collected from stakeholders or experts.

- When the research question requires the validation of findings obtained through one method by using another method.

- When the research question involves studying a complex phenomenon that cannot be understood by using only one method, such as studying the impact of a policy on a community’s well-being.

- When the research question involves studying a topic that has not been well-researched, and using mixed methods can help provide a more comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Purpose of Mixed Methods Research

The purpose of mixed methods research is to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a research problem than can be obtained through either quantitative or qualitative methods alone.

Mixed methods research is particularly useful when the research problem is complex and requires a deep understanding of the context and subjective experiences of participants, as well as the ability to generalize findings to a larger population. By combining both qualitative and quantitative methods, researchers can obtain a more complete picture of the research problem and its underlying mechanisms, as well as test hypotheses and identify patterns that may not be apparent with only one method.

Overall, mixed methods research aims to provide a more holistic and nuanced understanding of the research problem, allowing researchers to draw more valid and reliable conclusions, make more informed decisions, and develop more effective interventions and policies.

Advantages of Mixed Methods Research

Mixed methods research offers several advantages over using only qualitative or quantitative research methods. Here are some of the main advantages of mixed methods research:

- Comprehensive understanding: Mixed methods research provides a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem by combining both qualitative and quantitative data, which allows for a more nuanced interpretation of the data.

- Triangulation : Mixed methods research allows for triangulation, which is the use of multiple sources of data to verify findings. This improves the validity and reliability of the research.

- Addressing limitations: Mixed methods research can address the limitations of qualitative or quantitative research by compensating for the weaknesses of each method.

- Flexibility : Mixed methods research is flexible, allowing researchers to adapt the research design and methods as needed to best address the research question.

- Validity : Mixed methods research can increase the validity of the research by using multiple methods to measure the same concept.

- Generalizability : Mixed methods research can improve the generalizability of the findings by using quantitative data to test the applicability of qualitative findings to a larger population.

- Practical applications: Mixed methods research is useful for developing practical applications, such as interventions or policies, as it provides a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem.

Limitations of Mixed Methods Research

Here are some of the main limitations of mixed methods research:

- Time-consuming: Mixed methods research can be time-consuming and may require more resources than using only one research method.

- Complex data analysis: Integrating qualitative and quantitative data can be challenging and requires specialized skills for data analysis.

- Sampling bias: Mixed methods research can be subject to sampling bias, particularly if the sampling strategies for the qualitative and quantitative components are not aligned.

- Validity and reliability: Mixed methods research requires careful attention to the validity and reliability of both the qualitative and quantitative data, as well as the integration of the two data types.

- Difficulty in balancing the two methods: Mixed methods research can be difficult to balance the qualitative and quantitative methods effectively, particularly if one method dominates the other.

- Theoretical and philosophical issues: Mixed methods research raises theoretical and philosophical questions about the compatibility of qualitative and quantitative research methods and the underlying assumptions about the nature of reality and knowledge.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

- Open access

- Published: 15 December 2015

Qualitative and mixed methods in systematic reviews

- David Gough 1

Systematic Reviews volume 4 , Article number: 181 ( 2015 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

46 Citations

23 Altmetric

Metrics details

Expanding the range of methods of systematic review

The logic of systematic reviews is very simple. We use transparent rigorous approaches to undertake primary research, and so we should do the same in bringing together studies to describe what has been studied (a research map) or to integrate the findings of the different studies to answer a research question (a research synthesis). We should not really need to use the term ‘systematic’ as it should be assumed that researchers are using and reporting systematic methods in all of their research, whether primary or secondary. Despite the universality of this logic, systematic reviews (maps and syntheses) are much better known in health research and for answering questions of the effectiveness of interventions (what works). Systematic reviews addressing other sorts of questions have been around for many years, as in, for example, meta ethnography [ 1 ] and other forms of conceptual synthesis [ 2 ], but only recently has there been a major increase in the use of systematic review approaches to answer other sorts of research questions.

There are probably several reasons for this broadening of approach. One may be that the increased awareness of systematic reviews has made people consider the possibilities for all areas of research. A second related factor may be that more training and funding resources have become available and increased the capacity to undertake such varied review work.

A third reason could be that some of the initial anxieties about systematic reviews have subsided. Initially, there were concerns that their use was being promoted by a new managerialism where reviews, particularly effectiveness reviews, were being used to promote particular ideological and theoretical assumptions and to indirectly control research agendas. However, others like me believe that explicit methods should be used to enable transparency of perspectives driving research and to open up access to and participation in research agendas and priority setting [ 3 ] as illustrated, for example, by the James Lind Alliance (see http://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/ ).

A fourth possible reason for the development of new approaches is that effectiveness reviews have themselves broadened. Some ‘what works’ reviews can be open to criticism for only testing a ‘black box’ hypothesis of what works with little theorizing or any logic model about why any such hypothesis should be true and the mechanisms involved in such processes. There is now more concern to develop theory and to test how variables combine and interact. In primary research, qualitative strategies are advised prior to undertaking experimental trials [ 4 , 5 ] and similar approaches are being advocated to address complexity in reviews [ 6 ], in order to ask questions and use methods that address theories and processes that enable an understanding of both impact and context.

This Special Issue of Systematic Reviews Journal is providing a focus for these new methods of review whether these use qualitative review methods on their own or mixed together with more quantitative approaches. We are linking together with the sister journal Trials for this Special Issue as there is a similar interest in what qualitative approaches can and should contribute to primary research using experimentally controlled trials (see Trials Special Issue editorial by Claire Snowdon).

Dimensions of difference in reviews

Developing the range of methods to address different questions for review creates a challenge in describing and understanding such methods. There are many names and brands for the new methods which may or may not withstand the changes of historical time, but another way to comprehend the changes and new developments is to consider the dimensions on which the approaches to review differ [ 7 , 8 ].

One important distinction is the research question being asked and the associated paradigm underlying the method used to address this question. Research assumes a particular theoretical position and then gathers data within this conceptual lens. In some cases, this is a very specific hypothesis that is then tested empirically, and sometimes, the research is more exploratory and iterative with concepts being emergent and constructed during the research process. This distinction is often labelled as quantitative or positivist versus qualitative or constructionist. However, this can be confusing as much research taking a ‘quantitative’ perspective does not have the necessary numeric data to analyse. Even if it does have such data, this might be explored for emergent properties. Similarly, research taking a ‘qualitative’ perspective may include implicit quantitative themes in terms of the extent of different qualitative findings reported by a study.

Sandelowski and colleagues’ solution is to consider the analytic activity and whether this aggregates (adds up) or configures (arranges) the data [ 9 ]. In a randomized controlled trial and an effectiveness review of such studies, the main analysis is the aggregation of data using a priori non-emergent strategies with little iteration. However, there may also be post hoc analysis that is more exploratory in arranging (configuring) data to identify patterns as in, for example, meta regression or qualitative comparative analysis aiming to identify the active ingredients of effective interventions [ 10 ]. Similarly, qualitative primary research or reviews of such research are predominantly exploring emergent patterns and developing concepts iteratively, yet there may be some aggregation of data to make statements of generalizations of extent.

Even where the analysis is predominantly configuration, there can be a wide variation in the dimensions of difference of iteration of theories and concepts. In thematic synthesis [ 11 ], there may be few presumptions about the concepts that will be configured. In meta ethnography which can be richer in theory, there may be theoretical assumptions underlying the review question framing the analysis. In framework synthesis, there is an explicit conceptual framework that is iteratively developed and changed through the review process [ 12 , 13 ].

In addition to the variation in question, degree of configuration, complexity of theory, and iteration are many other dimensions of difference between reviews. Some of these differences follow on from the research questions being asked and the research paradigm being used such as in the approach to searching (exhaustive or based on exploration or saturation) and the appraisal of the quality and relevance of included studies (based more on risk of bias or more on meaning). Others include the extent that reviews have a broad question, depth of analysis, and the extent of resultant ‘work done’ in terms of progressing a field of inquiry [ 7 , 8 ].

Mixed methods reviews

As one reason for the growth in qualitative synthesis is what they can add to quantitative reviews, it is not surprising that there is also growing interest in mixed methods reviews. This reflects similar developments in primary research in mixing methods to examine the relationship between theory and empirical data which is of course the cornerstone of much research. But, both primary and secondary mixed methods research also face similar challenges in examining complex questions at different levels of analysis and of combining research findings investigated in different ways and may be based on very different epistemological assumptions [ 14 , 15 ].

Some mixed methods approaches are convergent in that they integrate different data and methods of analysis together at the same time [ 16 , 17 ]. Convergent systematic reviews could be described as having broad inclusion criteria (or two or more different sets of criteria) for methods of primary studies and have special methods for the synthesis of the resultant variation in data. Other reviews (and also primary mixed methods studies) are sequences of sub-reviews in that one sub-study using one research paradigm is followed by another sub-study with a different research paradigm. In other words, a qualitative synthesis might be used to explore the findings of a prior quantitative synthesis or vice versa [ 16 , 17 ].

An example of a predominantly aggregative sub-review followed by a configuring sub-review is the EPPI-Centre’s mixed methods review of barriers to healthy eating [ 18 ]. A sub-review on the effectiveness of public health interventions showed a modest effect size. A configuring review of studies of children and young people’s understanding and views about eating provided evidence that the public health interventions did not take good account of such user views research, and that the interventions most closely aligned to the user views were the most effective. The already mentioned qualitative comparative analysis to identify the active ingredients within interventions leading to impact could also be considered a qualitative configuring investigation of an existing quantitative aggregative review [ 10 ].

An example of a predominantly configurative review followed by an aggregative review is realist synthesis. Realist reviews examine the evidence in support of mid-range theories [ 19 ] with a first stage of a configuring review of what is proposed by the theory or proposal (what would need to be in place and what casual pathways would have to be effective for the outcomes proposed by the theory to be supported?) and a second stage searching for empirical evidence to test for those necessary conditions and effectiveness of the pathways. The empirical testing does not however use a standard ‘what works’ a priori methods approach but rather a more iterative seeking out of evidence that confirms or undermines the theory being evaluated [ 20 ].

Although sequential mixed methods approaches are considered to be sub-parts of one larger study, they could be separate studies as part of a long-term strategic approach to studying an issue. We tend to see both primary studies and reviews as one-off events, yet reviews are a way of examining what we know and what more we want to know as a strategic approach to studying an issue over time. If we are in favour of mixing paradigms of research to enable multiple levels and perspectives and mixing of theory development and empirical evaluation, then we are really seeking mixed methods research strategies rather than simply mixed methods studies and reviews.

Noblit G. Hare RD: meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park NY: Sage Publications; 1988.

Google Scholar

Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:59.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gough D, Elbourne D. Systematic research synthesis to inform policy, practice and democratic debate. Soc Pol Soc. 2002;2002:1.

Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance 2015. BMJ. 2015;350:h1258

Candy B, Jone L, King M, Oliver S. Using qualitative evidence to help understand complex palliative care interventions: a novel evidence synthesis approach. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014;4:Supp A41–A42.

Article Google Scholar

Noyes J, Gough D, Lewin S, Mayhew A, Michie S, Pantoja T, et al. A research and development agenda for systematic reviews that ask complex questions about complex interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:11.

Gough D, Oliver S, Thomas J. Introduction to systematic reviews. London: Sage; 2012.

Gough D, Thomas J, Oliver S. Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Syst Rev. 2012;1:28.

Sandelowski M, Voils CJ, Leeman J, Crandlee JL. Mapping the mixed methods-mixed research synthesis terrain. J Mix Methods Res. 2012;6:4.

Thomas J, O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G. Using qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) in systematic reviews of complex interventions: a worked example. Syst Rev. 2014;3:67.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45.

Oliver S, Rees R, Clarke-Jones L, Milne R, Oakley AR, Gabbay J, et al. A multidimensional conceptual framework for analysing public involvement in health services research. Health Exp. 2008;11:72–84.

Booth A, Carroll C. How to build up the actionable knowledge base: the role of ‘best fit’ framework synthesis for studies of improvement in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015. 2014-003642.

Brannen J. Mixed methods research: a discussion paper. NCRM Methods Review Papers, 2006. NCRM/005.

Creswell J. Mapping the developing landscape of mixed methods research. In: Teddlie C, Tashakkori A, editors. SAGE handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. New York: Sage; 2011.

Morse JM. Principles of mixed method and multi-method research design. In: Teddlie C, Tashakkori A, editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioural research. London: Sage; 2003.

Pluye P, Hong QN. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:29–45.

Harden A, Thomas J. Mixed methods and systematic reviews: examples and emerging issues. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. Handbook of mixed methods in the social and behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. London: Sage; 2010. p. 749–74.

Chapter Google Scholar

Pawson R. Evidenced-based policy: a realist perspective. London: Sage; 2006.

Book Google Scholar

Gough D. Meta-narrative and realist reviews: guidance, rules, publication standards and quality appraisal. BMC Med. 2013;11:22.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, University College London, London, WC1H 0NR, UK

David Gough

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to David Gough .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The author is a writer and researcher in this area. The author declares that he has no other competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Gough, D. Qualitative and mixed methods in systematic reviews. Syst Rev 4 , 181 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-015-0151-y

Download citation

Received : 13 October 2015

Accepted : 29 October 2015

Published : 15 December 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-015-0151-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 20, Issue 3

- Mixed methods research: expanding the evidence base

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Allison Shorten 1 ,

- Joanna Smith 2

- 1 School of Nursing , University of Alabama at Birmingham , USA

- 2 Children's Nursing, School of Healthcare , University of Leeds , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Allison Shorten, School of Nursing, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1720 2nd Ave South, Birmingham, AL, 35294, USA; [email protected]; ashorten{at}uab.edu

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2017-102699

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

‘Mixed methods’ is a research approach whereby researchers collect and analyse both quantitative and qualitative data within the same study. 1 2 Growth of mixed methods research in nursing and healthcare has occurred at a time of internationally increasing complexity in healthcare delivery. Mixed methods research draws on potential strengths of both qualitative and quantitative methods, 3 allowing researchers to explore diverse perspectives and uncover relationships that exist between the intricate layers of our multifaceted research questions. As providers and policy makers strive to ensure quality and safety for patients and families, researchers can use mixed methods to explore contemporary healthcare trends and practices across increasingly diverse practice settings.

What is mixed methods research?