- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- TikTok’s fate

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66606035/1207638131.jpg.0.jpg)

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.

So as the coronavirus pandemic has stretched around the world, it’s sparked a crop of diary entries and essays that describe how life has changed. Novelists, critics, artists, and journalists have put words to the feelings many are experiencing. The result is a first draft of how we’ll someday remember this time, filled with uncertainty and pain and fear as well as small moments of hope and humanity.

At the New York Review of Books, Ali Bhutto writes that in Karachi, Pakistan, the government-imposed curfew due to the virus is “eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns”:

Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

His essay concludes with the sobering note that “in the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another.”

Writing from Chattanooga, novelist Jamie Quatro documents the mixed ways her neighbors have been responding to the threat, and the frustration of conflicting direction, or no direction at all, from local, state, and federal leaders:

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders? We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

Award-winning photojournalist Alessio Mamo, quarantined with his partner Marta in Sicily after she tested positive for the virus, accompanies his photographs in the Guardian of their confinement with a reflection on being confined :

The doctors asked me to take a second test, but again I tested negative. Perhaps I’m immune? The days dragged on in my apartment, in black and white, like my photos. Sometimes we tried to smile, imagining that I was asymptomatic, because I was the virus. Our smiles seemed to bring good news. My mother left hospital, but I won’t be able to see her for weeks. Marta started breathing well again, and so did I. I would have liked to photograph my country in the midst of this emergency, the battles that the doctors wage on the frontline, the hospitals pushed to their limits, Italy on its knees fighting an invisible enemy. That enemy, a day in March, knocked on my door instead.

In the New York Times Magazine, deputy editor Jessica Lustig writes with devastating clarity about her family’s life in Brooklyn while her husband battled the virus, weeks before most people began taking the threat seriously:

At the door of the clinic, we stand looking out at two older women chatting outside the doorway, oblivious. Do I wave them away? Call out that they should get far away, go home, wash their hands, stay inside? Instead we just stand there, awkwardly, until they move on. Only then do we step outside to begin the long three-block walk home. I point out the early magnolia, the forsythia. T says he is cold. The untrimmed hairs on his neck, under his beard, are white. The few people walking past us on the sidewalk don’t know that we are visitors from the future. A vision, a premonition, a walking visitation. This will be them: Either T, in the mask, or — if they’re lucky — me, tending to him.

Essayist Leslie Jamison writes in the New York Review of Books about being shut away alone in her New York City apartment with her 2-year-old daughter since she became sick:

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

At Literary Hub, novelist Heidi Pitlor writes about the elastic nature of time during her family’s quarantine in Massachusetts:

During a shutdown, the things that mark our days—commuting to work, sending our kids to school, having a drink with friends—vanish and time takes on a flat, seamless quality. Without some self-imposed structure, it’s easy to feel a little untethered. A friend recently posted on Facebook: “For those who have lost track, today is Blursday the fortyteenth of Maprilay.” ... Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless. We do not know whether the virus will continue to rage for weeks or months or, lord help us, on and off for years. We do not know when we will feel safe again. And so many of us, minus those who are gifted at compartmentalization or denial, remain largely captive to fear. We may stay this way if we do not create at least the illusion of movement in our lives, our long days spent with ourselves or partners or families.

Novelist Lauren Groff writes at the New York Review of Books about trying to escape the prison of her fears while sequestered at home in Gainesville, Florida:

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

At ArtForum , Berlin-based critic and writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen reflects on martinis, melancholia, and Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo’s 2018 graphic novel Retreat , in which three young people exile themselves in the woods:

In melancholia, the shape of what is ending, and its temporality, is sprawling and incomprehensible. The ambivalence makes it hard to bear. The world of Retreat is rendered in lush pink and purple watercolors, which dissolve into wild and messy abstractions. In apocalypse, the divisions established in genesis bleed back out. My own Corona-retreat is similarly soft, color-field like, each day a blurred succession of quarantinis, YouTube–yoga, and televized press conferences. As restrictions mount, so does abstraction. For now, I’m still rooting for love to save the world.

At the Paris Review , Matt Levin writes about reading Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves during quarantine:

A retreat, a quarantine, a sickness—they simultaneously distort and clarify, curtail and expand. It is an ideal state in which to read literature with a reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, those hermetic books shorn of the handholds of conventional plot or characterization or description. A novel like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is perfect for the state of interiority induced by quarantine—a story of three men and three women, meeting after the death of a mutual friend, told entirely in the overlapping internal monologues of the six, interspersed only with sections of pure, achingly beautiful descriptions of the natural world, a day’s procession and recession of light and waves. The novel is, in my mind’s eye, a perfectly spherical object. It is translucent and shimmering and infinitely fragile, prone to shatter at the slightest disturbance. It is not a book that can be read in snatches on the subway—it demands total absorption. Though it revels in a stark emotional nakedness, the book remains aloof, remote in its own deep self-absorption.

In an essay for the Financial Times, novelist Arundhati Roy writes with anger about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s anemic response to the threat, but also offers a glimmer of hope for the future:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

From Boston, Nora Caplan-Bricker writes in The Point about the strange contraction of space under quarantine, in which a friend in Beirut is as close as the one around the corner in the same city:

It’s a nice illusion—nice to feel like we’re in it together, even if my real world has shrunk to one person, my husband, who sits with his laptop in the other room. It’s nice in the same way as reading those essays that reframe social distancing as solidarity. “We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love,” the poet Anne Boyer wrote on March 10th, the day that Massachusetts declared a state of emergency. If you squint, you could almost make sense of this quarantine as an effort to flatten, along with the curve, the distinctions we make between our bonds with others. Right now, I care for my neighbor in the same way I demonstrate love for my mother: in all instances, I stay away. And in moments this month, I have loved strangers with an intensity that is new to me. On March 14th, the Saturday night after the end of life as we knew it, I went out with my dog and found the street silent: no lines for restaurants, no children on bicycles, no couples strolling with little cups of ice cream. It had taken the combined will of thousands of people to deliver such a sudden and complete emptiness. I felt so grateful, and so bereft.

And on his own website, musician and artist David Byrne writes about rediscovering the value of working for collective good , saying that “what is happening now is an opportunity to learn how to change our behavior”:

In emergencies, citizens can suddenly cooperate and collaborate. Change can happen. We’re going to need to work together as the effects of climate change ramp up. In order for capitalism to survive in any form, we will have to be a little more socialist. Here is an opportunity for us to see things differently — to see that we really are all connected — and adjust our behavior accordingly. Are we willing to do this? Is this moment an opportunity to see how truly interdependent we all are? To live in a world that is different and better than the one we live in now? We might be too far down the road to test every asymptomatic person, but a change in our mindsets, in how we view our neighbors, could lay the groundwork for the collective action we’ll need to deal with other global crises. The time to see how connected we all are is now.

The portrait these writers paint of a world under quarantine is multifaceted. Our worlds have contracted to the confines of our homes, and yet in some ways we’re more connected than ever to one another. We feel fear and boredom, anger and gratitude, frustration and strange peace. Uncertainty drives us to find metaphors and images that will let us wrap our minds around what is happening.

Yet there’s no single “what” that is happening. Everyone is contending with the pandemic and its effects from different places and in different ways. Reading others’ experiences — even the most frightening ones — can help alleviate the loneliness and dread, a little, and remind us that what we’re going through is both unique and shared by all.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

At Vox, we believe that clarity is power, and that power shouldn’t only be available to those who can afford to pay. That’s why we keep our work free. Millions rely on Vox’s clear, high-quality journalism to understand the forces shaping today’s world. Support our mission and help keep Vox free for all by making a financial contribution to Vox today.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In Culture

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

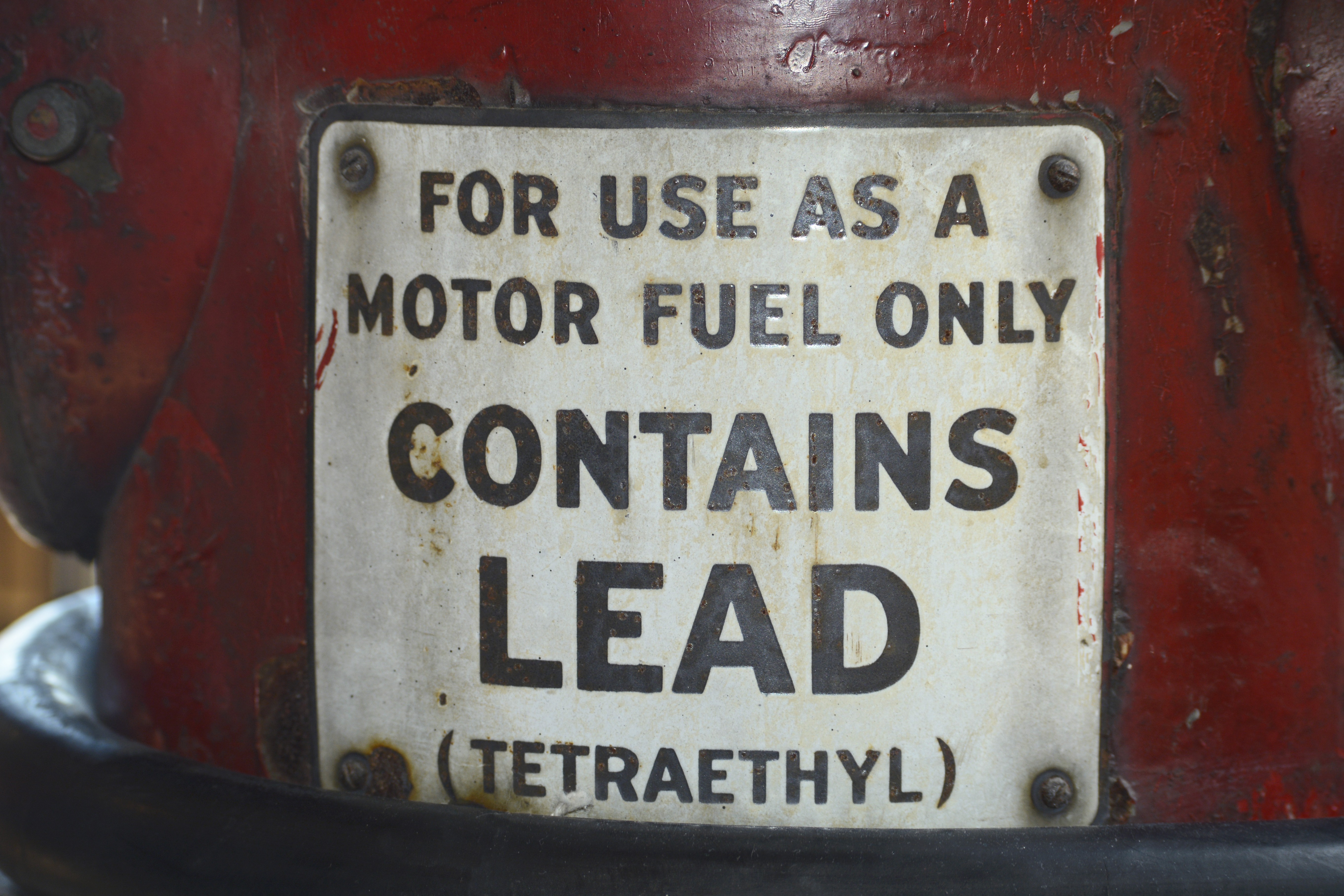

Why is there so much lead in American food?

Multigenerational housing is coming back in a big way

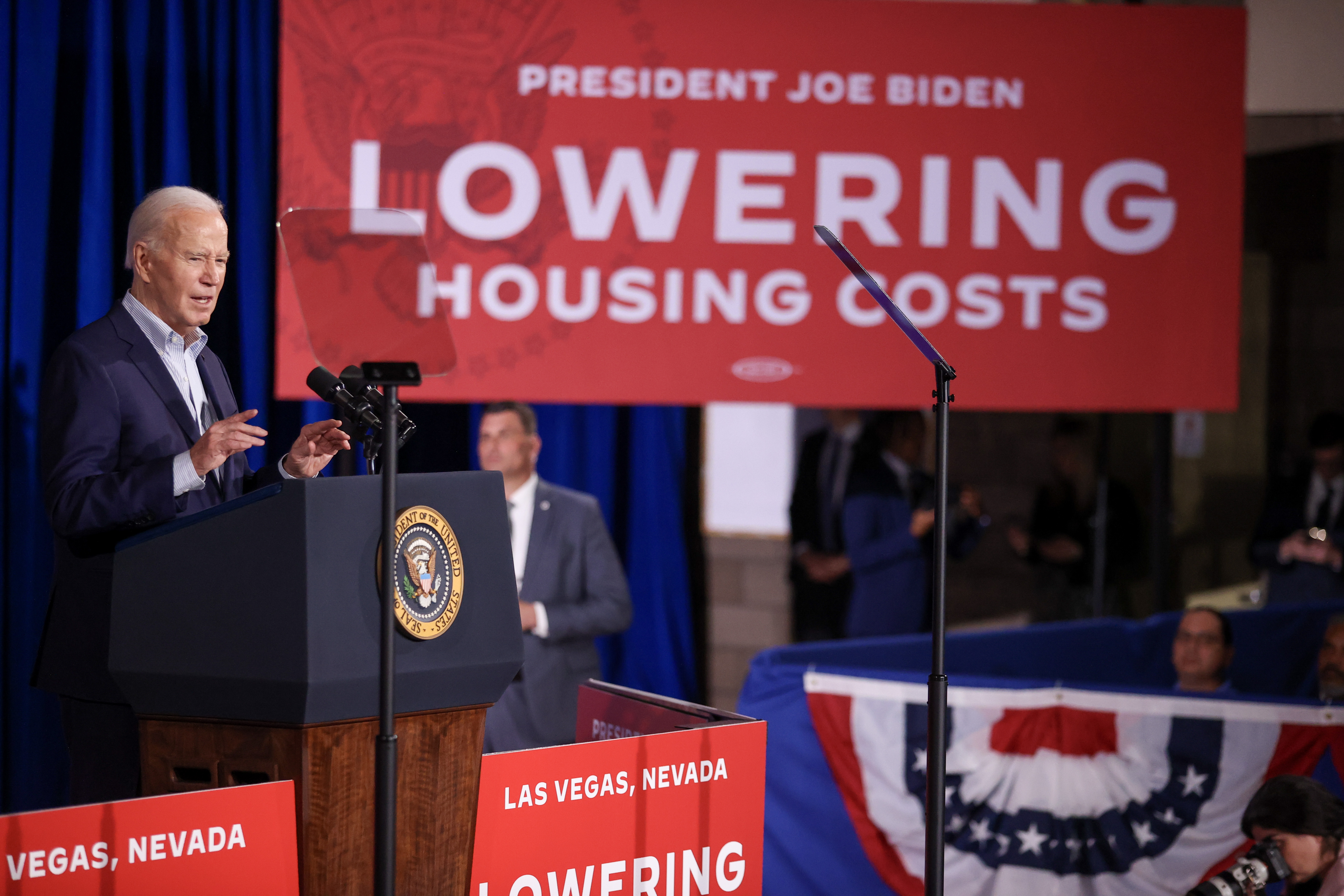

You can’t afford to buy a house. Biden knows that.

Want a 32-hour workweek? Give workers more power.

The harrowing “Quiet on Set” allegations, explained

The chaplain who doesn’t believe in God

Persuasive Essay Guide

Persuasive Essay About Covid19

How to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid19 | Examples & Tips

11 min read

People also read

A Comprehensive Guide to Writing an Effective Persuasive Essay

200+ Persuasive Essay Topics to Help You Out

Learn How to Create a Persuasive Essay Outline

30+ Free Persuasive Essay Examples To Get You Started

Read Excellent Examples of Persuasive Essay About Gun Control

Crafting a Convincing Persuasive Essay About Abortion

Learn to Write Persuasive Essay About Business With Examples and Tips

Check Out 12 Persuasive Essay About Online Education Examples

Persuasive Essay About Smoking - Making a Powerful Argument with Examples

Are you looking to write a persuasive essay about the Covid-19 pandemic?

Writing a compelling and informative essay about this global crisis can be challenging. It requires researching the latest information, understanding the facts, and presenting your argument persuasively.

But don’t worry! with some guidance from experts, you’ll be able to write an effective and persuasive essay about Covid-19.

In this blog post, we’ll outline the basics of writing a persuasive essay . We’ll provide clear examples, helpful tips, and essential information for crafting your own persuasive piece on Covid-19.

Read on to get started on your essay.

- 1. Steps to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

- 2. Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid19

- 3. Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Vaccine

- 4. Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Integration

- 5. Examples of Argumentative Essay About Covid 19

- 6. Examples of Persuasive Speeches About Covid-19

- 7. Tips to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

- 8. Common Topics for a Persuasive Essay on COVID-19

Steps to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Here are the steps to help you write a persuasive essay on this topic, along with an example essay:

Step 1: Choose a Specific Thesis Statement

Your thesis statement should clearly state your position on a specific aspect of COVID-19. It should be debatable and clear. For example:

Step 2: Research and Gather Information

Collect reliable and up-to-date information from reputable sources to support your thesis statement. This may include statistics, expert opinions, and scientific studies. For instance:

- COVID-19 vaccination effectiveness data

- Information on vaccine mandates in different countries

- Expert statements from health organizations like the WHO or CDC

Step 3: Outline Your Essay

Create a clear and organized outline to structure your essay. A persuasive essay typically follows this structure:

- Introduction

- Background Information

- Body Paragraphs (with supporting evidence)

- Counterarguments (addressing opposing views)

Step 4: Write the Introduction

In the introduction, grab your reader's attention and present your thesis statement. For example:

Step 5: Provide Background Information

Offer context and background information to help your readers understand the issue better. For instance:

Step 6: Develop Body Paragraphs

Each body paragraph should present a single point or piece of evidence that supports your thesis statement. Use clear topic sentences, evidence, and analysis. Here's an example:

Step 7: Address Counterarguments

Acknowledge opposing viewpoints and refute them with strong counterarguments. This demonstrates that you've considered different perspectives. For example:

Step 8: Write the Conclusion

Summarize your main points and restate your thesis statement in the conclusion. End with a strong call to action or thought-provoking statement. For instance:

Step 9: Revise and Proofread

Edit your essay for clarity, coherence, grammar, and spelling errors. Ensure that your argument flows logically.

Step 10: Cite Your Sources

Include proper citations and a bibliography page to give credit to your sources.

Remember to adjust your approach and arguments based on your target audience and the specific angle you want to take in your persuasive essay about COVID-19.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid19

When writing a persuasive essay about the Covid-19 pandemic, it’s important to consider how you want to present your argument. To help you get started, here are some example essays for you to read:

Check out some more PDF examples below:

Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Pandemic

Sample Of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 In The Philippines - Example

If you're in search of a compelling persuasive essay on business, don't miss out on our “ persuasive essay about business ” blog!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Vaccine

Covid19 vaccines are one of the ways to prevent the spread of Covid-19, but they have been a source of controversy. Different sides argue about the benefits or dangers of the new vaccines. Whatever your point of view is, writing a persuasive essay about it is a good way of organizing your thoughts and persuading others.

A persuasive essay about the Covid-19 vaccine could consider the benefits of getting vaccinated as well as the potential side effects.

Below are some examples of persuasive essays on getting vaccinated for Covid-19.

Covid19 Vaccine Persuasive Essay

Persuasive Essay on Covid Vaccines

Interested in thought-provoking discussions on abortion? Read our persuasive essay about abortion blog to eplore arguments!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Integration

Covid19 has drastically changed the way people interact in schools, markets, and workplaces. In short, it has affected all aspects of life. However, people have started to learn to live with Covid19.

Writing a persuasive essay about it shouldn't be stressful. Read the sample essay below to get idea for your own essay about Covid19 integration.

Persuasive Essay About Working From Home During Covid19

Searching for the topic of Online Education? Our persuasive essay about online education is a must-read.

Examples of Argumentative Essay About Covid 19

Covid-19 has been an ever-evolving issue, with new developments and discoveries being made on a daily basis.

Writing an argumentative essay about such an issue is both interesting and challenging. It allows you to evaluate different aspects of the pandemic, as well as consider potential solutions.

Here are some examples of argumentative essays on Covid19.

Argumentative Essay About Covid19 Sample

Argumentative Essay About Covid19 With Introduction Body and Conclusion

Looking for a persuasive take on the topic of smoking? You'll find it all related arguments in out Persuasive Essay About Smoking blog!

Examples of Persuasive Speeches About Covid-19

Do you need to prepare a speech about Covid19 and need examples? We have them for you!

Persuasive speeches about Covid-19 can provide the audience with valuable insights on how to best handle the pandemic. They can be used to advocate for specific changes in policies or simply raise awareness about the virus.

Check out some examples of persuasive speeches on Covid-19:

Persuasive Speech About Covid-19 Example

Persuasive Speech About Vaccine For Covid-19

You can also read persuasive essay examples on other topics to master your persuasive techniques!

Tips to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Writing a persuasive essay about COVID-19 requires a thoughtful approach to present your arguments effectively.

Here are some tips to help you craft a compelling persuasive essay on this topic:

Choose a Specific Angle

Start by narrowing down your focus. COVID-19 is a broad topic, so selecting a specific aspect or issue related to it will make your essay more persuasive and manageable. For example, you could focus on vaccination, public health measures, the economic impact, or misinformation.

Provide Credible Sources

Support your arguments with credible sources such as scientific studies, government reports, and reputable news outlets. Reliable sources enhance the credibility of your essay.

Use Persuasive Language

Employ persuasive techniques, such as ethos (establishing credibility), pathos (appealing to emotions), and logos (using logic and evidence). Use vivid examples and anecdotes to make your points relatable.

Organize Your Essay

Structure your essay involves creating a persuasive essay outline and establishing a logical flow from one point to the next. Each paragraph should focus on a single point, and transitions between paragraphs should be smooth and logical.

Emphasize Benefits

Highlight the benefits of your proposed actions or viewpoints. Explain how your suggestions can improve public health, safety, or well-being. Make it clear why your audience should support your position.

Use Visuals -H3

Incorporate graphs, charts, and statistics when applicable. Visual aids can reinforce your arguments and make complex data more accessible to your readers.

Call to Action

End your essay with a strong call to action. Encourage your readers to take a specific step or consider your viewpoint. Make it clear what you want them to do or think after reading your essay.

Revise and Edit

Proofread your essay for grammar, spelling, and clarity. Make sure your arguments are well-structured and that your writing flows smoothly.

Seek Feedback

Have someone else read your essay to get feedback. They may offer valuable insights and help you identify areas where your persuasive techniques can be improved.

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Common Topics for a Persuasive Essay on COVID-19

Here are some persuasive essay topics on COVID-19:

- The Importance of Vaccination Mandates for COVID-19 Control

- Balancing Public Health and Personal Freedom During a Pandemic

- The Economic Impact of Lockdowns vs. Public Health Benefits

- The Role of Misinformation in Fueling Vaccine Hesitancy

- Remote Learning vs. In-Person Education: What's Best for Students?

- The Ethics of Vaccine Distribution: Prioritizing Vulnerable Populations

- The Mental Health Crisis Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic

- The Long-Term Effects of COVID-19 on Healthcare Systems

- Global Cooperation vs. Vaccine Nationalism in Fighting the Pandemic

- The Future of Telemedicine: Expanding Healthcare Access Post-COVID-19

In search of more inspiring topics for your next persuasive essay? Our persuasive essay topics blog has plenty of ideas!

To sum it up,

You have read good sample essays and got some helpful tips. You now have the tools you needed to write a persuasive essay about Covid-19. So don't let the doubts stop you, start writing!

If you need professional writing help, don't worry! We've got that for you as well.

MyPerfectWords.com is a professional essay writing service that can help you craft an excellent persuasive essay on Covid-19. Our experienced essay writer will create a well-structured, insightful paper in no time!

So don't hesitate and get in touch with our persuasive essay writing service today!

Frequently Asked Questions

Are there any ethical considerations when writing a persuasive essay about covid-19.

Yes, there are ethical considerations when writing a persuasive essay about COVID-19. It's essential to ensure the information is accurate, not contribute to misinformation, and be sensitive to the pandemic's impact on individuals and communities. Additionally, respecting diverse viewpoints and emphasizing public health benefits can promote ethical communication.

What impact does COVID-19 have on society?

The impact of COVID-19 on society is far-reaching. It has led to job and economic losses, an increase in stress and mental health disorders, and changes in education systems. It has also had a negative effect on social interactions, as people have been asked to limit their contact with others.

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Caleb S. has been providing writing services for over five years and has a Masters degree from Oxford University. He is an expert in his craft and takes great pride in helping students achieve their academic goals. Caleb is a dedicated professional who always puts his clients first.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

I Thought We’d Learned Nothing From the Pandemic. I Wasn’t Seeing the Full Picture

M y first home had a back door that opened to a concrete patio with a giant crack down the middle. When my sister and I played, I made sure to stay on the same side of the divide as her, just in case. The 1988 film The Land Before Time was one of the first movies I ever saw, and the image of the earth splintering into pieces planted its roots in my brain. I believed that, even in my own backyard, I could easily become the tiny Triceratops separated from her family, on the other side of the chasm, as everything crumbled into chaos.

Some 30 years later, I marvel at the eerie, unexpected ways that cartoonish nightmare came to life – not just for me and my family, but for all of us. The landscape was already covered in fissures well before COVID-19 made its way across the planet, but the pandemic applied pressure, and the cracks broke wide open, separating us from each other physically and ideologically. Under the weight of the crisis, we scattered and landed on such different patches of earth we could barely see each other’s faces, even when we squinted. We disagreed viciously with each other, about how to respond, but also about what was true.

Recently, someone asked me if we’ve learned anything from the pandemic, and my first thought was a flat no. Nothing. There was a time when I thought it would be the very thing to draw us together and catapult us – as a capital “S” Society – into a kinder future. It’s surreal to remember those early days when people rallied together, sewing masks for health care workers during critical shortages and gathering on balconies in cities from Dallas to New York City to clap and sing songs like “Yellow Submarine.” It felt like a giant lightning bolt shot across the sky, and for one breath, we all saw something that had been hidden in the dark – the inherent vulnerability in being human or maybe our inescapable connectedness .

More from TIME

Read More: The Family Time the Pandemic Stole

But it turns out, it was just a flash. The goodwill vanished as quickly as it appeared. A couple of years later, people feel lied to, abandoned, and all on their own. I’ve felt my own curiosity shrinking, my willingness to reach out waning , my ability to keep my hands open dwindling. I look out across the landscape and see selfishness and rage, burnt earth and so many dead bodies. Game over. We lost. And if we’ve already lost, why try?

Still, the question kept nagging me. I wondered, am I seeing the full picture? What happens when we focus not on the collective society but at one face, one story at a time? I’m not asking for a bow to minimize the suffering – a pretty flourish to put on top and make the whole thing “worth it.” Yuck. That’s not what we need. But I wondered about deep, quiet growth. The kind we feel in our bodies, relationships, homes, places of work, neighborhoods.

Like a walkie-talkie message sent to my allies on the ground, I posted a call on my Instagram. What do you see? What do you hear? What feels possible? Is there life out here? Sprouting up among the rubble? I heard human voices calling back – reports of life, personal and specific. I heard one story at a time – stories of grief and distrust, fury and disappointment. Also gratitude. Discovery. Determination.

Among the most prevalent were the stories of self-revelation. Almost as if machines were given the chance to live as humans, people described blossoming into fuller selves. They listened to their bodies’ cues, recognized their desires and comforts, tuned into their gut instincts, and honored the intuition they hadn’t realized belonged to them. Alex, a writer and fellow disabled parent, found the freedom to explore a fuller version of herself in the privacy the pandemic provided. “The way I dress, the way I love, and the way I carry myself have both shrunk and expanded,” she shared. “I don’t love myself very well with an audience.” Without the daily ritual of trying to pass as “normal” in public, Tamar, a queer mom in the Netherlands, realized she’s autistic. “I think the pandemic helped me to recognize the mask,” she wrote. “Not that unmasking is easy now. But at least I know it’s there.” In a time of widespread suffering that none of us could solve on our own, many tended to our internal wounds and misalignments, large and small, and found clarity.

Read More: A Tool for Staying Grounded in This Era of Constant Uncertainty

I wonder if this flourishing of self-awareness is at least partially responsible for the life alterations people pursued. The pandemic broke open our personal notions of work and pushed us to reevaluate things like time and money. Lucy, a disabled writer in the U.K., made the hard decision to leave her job as a journalist covering Westminster to write freelance about her beloved disability community. “This work feels important in a way nothing else has ever felt,” she wrote. “I don’t think I’d have realized this was what I should be doing without the pandemic.” And she wasn’t alone – many people changed jobs , moved, learned new skills and hobbies, became politically engaged.

Perhaps more than any other shifts, people described a significant reassessment of their relationships. They set boundaries, said no, had challenging conversations. They also reconnected, fell in love, and learned to trust. Jeanne, a quilter in Indiana, got to know relatives she wouldn’t have connected with if lockdowns hadn’t prompted weekly family Zooms. “We are all over the map as regards to our belief systems,” she emphasized, “but it is possible to love people you don’t see eye to eye with on every issue.” Anna, an anti-violence advocate in Maine, learned she could trust her new marriage: “Life was not a honeymoon. But we still chose to turn to each other with kindness and curiosity.” So many bonds forged and broken, strengthened and strained.

Instead of relying on default relationships or institutional structures, widespread recalibrations allowed for going off script and fortifying smaller communities. Mara from Idyllwild, Calif., described the tangible plan for care enacted in her town. “We started a mutual-aid group at the beginning of the pandemic,” she wrote, “and it grew so quickly before we knew it we were feeding 400 of the 4000 residents.” She didn’t pretend the conditions were ideal. In fact, she expressed immense frustration with our collective response to the pandemic. Even so, the local group rallied and continues to offer assistance to their community with help from donations and volunteers (many of whom were originally on the receiving end of support). “I’ve learned that people thrive when they feel their connection to others,” she wrote. Clare, a teacher from the U.K., voiced similar conviction as she described a giant scarf she’s woven out of ribbons, each representing a single person. The scarf is “a collection of stories, moments and wisdom we are sharing with each other,” she wrote. It now stretches well over 1,000 feet.

A few hours into reading the comments, I lay back on my bed, phone held against my chest. The room was quiet, but my internal world was lighting up with firefly flickers. What felt different? Surely part of it was receiving personal accounts of deep-rooted growth. And also, there was something to the mere act of asking and listening. Maybe it connected me to humans before battle cries. Maybe it was the chance to be in conversation with others who were also trying to understand – what is happening to us? Underneath it all, an undeniable thread remained; I saw people peering into the mess and narrating their findings onto the shared frequency. Every comment was like a flare into the sky. I’m here! And if the sky is full of flares, we aren’t alone.

I recognized my own pandemic discoveries – some minor, others massive. Like washing off thick eyeliner and mascara every night is more effort than it’s worth; I can transform the mundane into the magical with a bedsheet, a movie projector, and twinkle lights; my paralyzed body can mother an infant in ways I’d never seen modeled for me. I remembered disappointing, bewildering conversations within my own family of origin and our imperfect attempts to remain close while also seeing things so differently. I realized that every time I get the weekly invite to my virtual “Find the Mumsies” call, with a tiny group of moms living hundreds of miles apart, I’m being welcomed into a pocket of unexpected community. Even though we’ve never been in one room all together, I’ve felt an uncommon kind of solace in their now-familiar faces.

Hope is a slippery thing. I desperately want to hold onto it, but everywhere I look there are real, weighty reasons to despair. The pandemic marks a stretch on the timeline that tangles with a teetering democracy, a deteriorating planet , the loss of human rights that once felt unshakable . When the world is falling apart Land Before Time style, it can feel trite, sniffing out the beauty – useless, firing off flares to anyone looking for signs of life. But, while I’m under no delusions that if we just keep trudging forward we’ll find our own oasis of waterfalls and grassy meadows glistening in the sunshine beneath a heavenly chorus, I wonder if trivializing small acts of beauty, connection, and hope actually cuts us off from resources essential to our survival. The group of abandoned dinosaurs were keeping each other alive and making each other laugh well before they made it to their fantasy ending.

Read More: How Ice Cream Became My Own Personal Act of Resistance

After the monarch butterfly went on the endangered-species list, my friend and fellow writer Hannah Soyer sent me wildflower seeds to plant in my yard. A simple act of big hope – that I will actually plant them, that they will grow, that a monarch butterfly will receive nourishment from whatever blossoms are able to push their way through the dirt. There are so many ways that could fail. But maybe the outcome wasn’t exactly the point. Maybe hope is the dogged insistence – the stubborn defiance – to continue cultivating moments of beauty regardless. There is value in the planting apart from the harvest.

I can’t point out a single collective lesson from the pandemic. It’s hard to see any great “we.” Still, I see the faces in my moms’ group, making pancakes for their kids and popping on between strings of meetings while we try to figure out how to raise these small people in this chaotic world. I think of my friends on Instagram tending to the selves they discovered when no one was watching and the scarf of ribbons stretching the length of more than three football fields. I remember my family of three, holding hands on the way up the ramp to the library. These bits of growth and rings of support might not be loud or right on the surface, but that’s not the same thing as nothing. If we only cared about the bottom-line defeats or sweeping successes of the big picture, we’d never plant flowers at all.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Why We're Spending So Much Money Now

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- Breaker Sunny Choi Is Heading to Paris

- Why TV Can’t Stop Making Silly Shows About Lady Journalists

- The Case for Wearing Shoes in the House

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

What Life Was Like for Students in the Pandemic Year

- Share article

In this video, Navajo student Miles Johnson shares how he experienced the stress and anxiety of schools shutting down last year. Miles’ teacher shared his experience and those of her other students in a recent piece for Education Week. In these short essays below, teacher Claire Marie Grogan’s 11th grade students at Oceanside High School on Long Island, N.Y., describe their pandemic experiences. Their writings have been slightly edited for clarity. Read Grogan’s essay .

“Hours Staring at Tiny Boxes on the Screen”

By Kimberly Polacco, 16

I stare at my blank computer screen, trying to find the motivation to turn it on, but my finger flinches every time it hovers near the button. I instead open my curtains. It is raining outside, but it does not matter, I will not be going out there for the rest of the day. The sound of pounding raindrops contributes to my headache enough to make me turn on my computer in hopes that it will give me something to drown out the noise. But as soon as I open it up, I feel the weight of the world crash upon my shoulders.

Each 42-minute period drags on by. I spend hours upon hours staring at tiny boxes on a screen, one of which my exhausted face occupies, and attempt to retain concepts that have been presented to me through this device. By the time I have the freedom of pressing the “leave” button on my last Google Meet of the day, my eyes are heavy and my legs feel like mush from having not left my bed since I woke up.

Tomorrow arrives, except this time here I am inside of a school building, interacting with my first period teacher face to face. We talk about our favorite movies and TV shows to stream as other kids pile into the classroom. With each passing period I accumulate more and more of these tiny meaningless conversations everywhere I go with both teachers and students. They may not seem like much, but to me they are everything because I know that the next time I am expected to report to school, I will be trapped in the bubble of my room counting down the hours until I can sit down in my freshly sanitized wooden desk again.

“My Only Parent Essentially on Her Death Bed”

By Nick Ingargiola, 16

My mom had COVID-19 for ten weeks. She got sick during the first month school buildings were shut. The difficulty of navigating an online classroom was already overwhelming, and when mixed with my only parent essentially on her death bed, it made it unbearable. Focusing on schoolwork was impossible, and watching my mother struggle to lift up her arm broke my heart.

My mom has been through her fair share of diseases from pancreatic cancer to seizures and even as far as a stroke that paralyzed her entire left side. It is safe to say she has been through a lot. The craziest part is you would never know it. She is the strongest and most positive person I’ve ever met. COVID hit her hard. Although I have watched her go through life and death multiple times, I have never seen her so physically and mentally drained.

I initially was overjoyed to complete my school year in the comfort of my own home, but once my mom got sick, I couldn’t handle it. No one knows what it’s like to pretend like everything is OK until they are forced to. I would wake up at 8 after staying up until 5 in the morning pondering the possibility of losing my mother. She was all I had. I was forced to turn my camera on and float in the fake reality of being fine although I wasn’t. The teachers tried to keep the class engaged by obligating the students to participate. This was dreadful. I didn’t want to talk. I had to hide the distress in my voice. If only the teachers understood what I was going through. I was hesitant because I didn’t want everyone to know that the virus that was infecting and killing millions was knocking on my front door.

After my online classes, I was required to finish an immense amount of homework while simultaneously hiding my sadness so that my mom wouldn’t worry about me. She was already going through a lot. There was no reason to add me to her list of worries. I wasn’t even able to give her a hug. All I could do was watch.

“The Way of Staying Sane”

By Lynda Feustel, 16

Entering year two of the pandemic is strange. It barely seems a day since last March, but it also seems like a lifetime. As an only child and introvert, shutting down my world was initially simple and relatively easy. My friends and I had been super busy with the school play, and while I was sad about it being canceled, I was struggling a lot during that show and desperately needed some time off.

As March turned to April, virtual school began, and being alone really set in. I missed my friends and us being together. The isolation felt real with just my parents and me, even as we spent time together. My friends and I began meeting on Facetime every night to watch TV and just be together in some way. We laughed at insane jokes we made and had homework and therapy sessions over Facetime and grew closer through digital and literal walls.

The summer passed with in-person events together, and the virus faded into the background for a little while. We went to the track and the beach and hung out in people’s backyards.

Then school came for us in a more nasty way than usual. In hybrid school we were separated. People had jobs, sports, activities, and quarantines. Teachers piled on work, and the virus grew more present again. The group text put out hundreds of messages a day while the Facetimes came to a grinding halt, and meeting in person as a group became more of a rarity. Being together on video and in person was the way of staying sane.

In a way I am in a similar place to last year, working and looking for some change as we enter the second year of this mess.

“In History Class, Reports of Heightening Cases”

By Vivian Rose, 16

I remember the moment my freshman year English teacher told me about the young writers’ conference at Bread Loaf during my sophomore year. At first, I didn’t want to apply, the deadline had passed, but for some strange reason, the directors of the program extended it another week. It felt like it was meant to be. It was in Vermont in the last week of May when the flowers have awakened and the sun is warm.

I submitted my work, and two weeks later I got an email of my acceptance. I screamed at the top of my lungs in the empty house; everyone was out, so I was left alone to celebrate my small victory. It was rare for them to admit sophomores. Usually they accept submissions only from juniors and seniors.

That was the first week of February 2020. All of a sudden, there was some talk about this strange virus coming from China. We thought nothing of it. Every night, I would fall asleep smiling, knowing that I would be able to go to the exact conference that Robert Frost attended for 42 years.

Then, as if overnight, it seemed the virus had swung its hand and had gripped parts of the country. Every newscast was about the disease. Every day in history, we would look at the reports of heightening cases and joke around that this could never become a threat as big as Dr. Fauci was proposing. Then, March 13th came around--it was the last day before the world seemed to shut down. Just like that, Bread Loaf would vanish from my grasp.

“One Day Every Day Won’t Be As Terrible”

By Nick Wollweber, 17

COVID created personal problems for everyone, some more serious than others, but everyone had a struggle.

As the COVID lock-down took hold, the main thing weighing on my mind was my oldest brother, Joe, who passed away in January 2019 unexpectedly in his sleep. Losing my brother was a complete gut punch and reality check for me at 14 and 15 years old. 2019 was a year of struggle, darkness, sadness, frustration. I didn’t want to learn after my brother had passed, but I had to in order to move forward and find my new normal.

Routine and always having things to do and places to go is what let me cope in the year after Joe died. Then COVID came and gave me the option to let up and let down my guard. I struggled with not wanting to take care of personal hygiene. That was the beginning of an underlying mental problem where I wouldn’t do things that were necessary for everyday life.

My “coping routine” that got me through every day and week the year before was gone. COVID wasn’t beneficial to me, but it did bring out the true nature of my mental struggles and put a name to it. Since COVID, I have been diagnosed with severe depression and anxiety. I began taking antidepressants and going to therapy a lot more.

COVID made me realize that I’m not happy with who I am and that I needed to change. I’m still not happy with who I am. I struggle every day, but I am working towards a goal that one day every day won’t be as terrible.

Coverage of social and emotional learning is supported in part by a grant from the NoVo Foundation, at www.novofoundation.org . Education Week retains sole editorial control over the content of this coverage. A version of this article appeared in the March 31, 2021 edition of Education Week as What Life Was Like for Students in the Pandemic Year

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

How to decide if an mba is worth it.

Sarah Wood March 27, 2024

What to Wear to a Graduation

LaMont Jones, Jr. March 27, 2024

FAFSA Delays Alarm Families, Colleges

Sarah Wood March 25, 2024

Help Your Teen With the College Decision

Anayat Durrani March 25, 2024

Toward Semiconductor Gender Equity

Alexis McKittrick March 22, 2024

March Madness in the Classroom

Cole Claybourn March 21, 2024

20 Lower-Cost Online Private Colleges

Sarah Wood March 21, 2024

How to Choose a Microcredential

Sarah Wood March 20, 2024

Basic Components of an Online Course

Cole Claybourn March 19, 2024

Can You Double Minor in College?

Sarah Wood March 15, 2024

Seven short essays about life during the pandemic

The boston book festival's at home community writing project invites area residents to describe their experiences during this unprecedented time..

My alarm sounds at 8:15 a.m. I open my eyes and take a deep breath. I wiggle my toes and move my legs. I do this religiously every morning. Today, marks day 74 of staying at home.

My mornings are filled with reading biblical scripture, meditation, breathing in the scents of a hanging eucalyptus branch in the shower, and making tea before I log into my computer to work. After an hour-and-a-half Zoom meeting, I decided to take a long walk to the post office and grab a fresh bouquet of burnt orange ranunculus flowers. I embrace the warm sun beaming on my face. I feel joy. I feel at peace.

Advertisement

I enter my apartment and excessively wash my hands and face. I pour a glass of iced kombucha. I sit at my table and look at the text message on my phone. My coworker writes that she is thinking of me during this difficult time. She must be referring to the Amy Cooper incident. I learn shortly that she is not.

I Google Minneapolis and see his name: George Floyd. And just like that a simple and beautiful day transitions into a day of sorrow.

Nakia Hill, Boston

It was a wobbly, yet solemn little procession: three masked mourners and a canine. Beginning in Kenmore Square, at David and Sue Horner’s condo, it proceeded up Commonwealth Avenue Mall.

S. Sue Horner died on Good Friday, April 10, in the Year of the Virus. Sue did not die of the virus but her parting was hemmed by it: no gatherings to mark the passing of this splendid human being.

David devised a send-off nevertheless. On April 23rd, accompanied by his daughter and son-in-law, he set out for Old South Church. David led, bearing the urn. His daughter came next, holding her phone aloft, speaker on, through which her brother in Illinois played the bagpipes for the length of the procession, its soaring thrum infusing the Mall. Her husband came last with Melon, their golden retriever.

I unlocked the empty church and led the procession into the columbarium. David drew the urn from its velvet cover, revealing a golden vessel inset with incandescent tiles. We lifted the urn into the niche, prayed, recited Psalm 23, and shared some words.

It was far too small for the luminous “Dr. Sue”, but what we could manage in the Year of the Virus.

Nancy S. Taylor, Boston

On April 26, 2020, our household was a bustling home for four people. Our two sons, ages 18 and 22, have a lot of energy. We are among the lucky ones. I can work remotely. Our food and shelter are not at risk.

As I write this a week later, it is much quieter here.

On April 27, our older son, an EMT, transported a COVID-19 patient to the ER. He left home to protect my delicate health and became ill with the virus a week later.

On April 29, my husband’s 95-year-old father had a stroke. My husband left immediately to be with his 90-year-old mother near New York City and is now preparing for his father’s discharge from the hospital. Rehab people will come to the house; going to a facility would be too dangerous.

My husband just called me to describe today’s hospital visit. The doctors had warned that although his father had regained the ability to speak, he could only repeat what was said to him.

“It’s me,” said my husband.

“It’s me,” said my father-in-law.

“I love you,” said my husband.

“I love you,” said my father-in-law.

“Sooooooooo much,” said my father-in-law.

Lucia Thompson, Wayland

Would racism exist if we were blind?

I felt his eyes bore into me as I walked through the grocery store. At first, I thought nothing of it. With the angst in the air attributable to COVID, I understood the anxiety-provoking nature of feeling as though your 6-foot bubble had burst. So, I ignored him and maintained my distance. But he persisted, glaring at my face, squinting to see who I was underneath the mask. This time I looked back, when he yelled, in my mother tongue, for me to go back to my country.

In shock, I just laughed. How could he tell what I was under my mask? Or see anything through the sunglasses he was wearing inside? It baffled me. I laughed at the irony that he would use my own language against me, that he knew enough to guess where I was from in some version of culturally competent racism. I laughed because dealing with the truth behind that comment generated a sadness in me that was too much to handle. If not now, then when will we be together?

So I ask again, would racism exist if we were blind?

Faizah Shareef, Boston

My Family is “Out” There

But I am “in” here. Life is different now “in” Assisted Living since the deadly COVID-19 arrived. Now the staff, employees, and all 100 residents have our temperatures taken daily. Everyone else, including my family, is “out” there. People like the hairdresser are really missed — with long straight hair and masks, we don’t even recognize ourselves.

Since mid-March we are in quarantine “in” our rooms with meals served. Activities are practically non-existent. We can sit on the back patio 6 feet apart, wearing masks, do exercises there, chat, and walk nearby. Nothing inside. Hopefully June will improve.

My family is “out” there — somewhere! Most are working from home (or Montana). Hopefully an August wedding will happen, but unfortunately, I may still be “in” here.

From my window I wave to my son “out” there. Recently, when my daughter visited, I opened the window “in” my second-floor room and could see and hear her perfectly “out” there. Next time she will bring a chair so we can have an “in” and “out” conversation all day, or until we run out of words.

Barbara Anderson, Raynham

My boyfriend Marcial lives in Boston, and I live in New York City. We had been doing the long-distance thing pretty successfully until coronavirus hit. In mid-March, I was furloughed from my temp job, Marcial began working remotely, and New York started shutting down. I went to Boston to stay with Marcial.

We are opposites in many ways, but we share a love of food. The kitchen has been the center of quarantine life —and also quarantine problems.

Marcial and I have gone from eating out and cooking/grocery shopping for each other during our periodic visits to cooking/grocery shopping with each other all the time. We’ve argued over things like the proper way to make rice and what greens to buy for salad. Our habits are deeply rooted in our upbringing and individual cultures (Filipino immigrant and American-born Chinese, hence the strong rice opinions).

On top of the mundane issues, we’ve also dealt with a flooded kitchen (resulting in cockroaches) and a mandoline accident leading to an ER visit. Marcial and I have spent quarantine navigating how to handle the unexpected and how to integrate our lifestyles. We’ve been eating well along the way.

Melissa Lee, Waltham

It’s 3 a.m. and my dog Rikki just gave me a worried look. Up again?

“I can’t sleep,” I say. I flick the light, pick up “Non-Zero Probabilities.” But the words lay pinned to the page like swatted flies. I watch new “Killing Eve” episodes, play old Nathaniel Rateliff and The Night Sweats songs. Still night.

We are — what? — 12 agitated weeks into lockdown, and now this. The thing that got me was Chauvin’s sunglasses. Perched nonchalantly on his head, undisturbed, as if he were at a backyard BBQ. Or anywhere other than kneeling on George Floyd’s neck, on his life. And Floyd was a father, as we all now know, having seen his daughter Gianna on Stephen Jackson’s shoulders saying “Daddy changed the world.”

Precious child. I pray, safeguard her.

Rikki has her own bed. But she won’t leave me. A Goddess of Protection. She does that thing dogs do, hovers increasingly closely the more agitated I get. “I’m losing it,” I say. I know. And like those weighted gravity blankets meant to encourage sleep, she drapes her 70 pounds over me, covering my restless heart with safety.

As if daybreak, or a prayer, could bring peace today.

Kirstan Barnett, Watertown

Until June 30, send your essay (200 words or less) about life during COVID-19 via bostonbookfest.org . Some essays will be published on the festival’s blog and some will appear in The Boston Globe.

Coronavirus: What students have learned living in pandemic: Student Voices winners

As students settle into their new routines, the appreciation for many things taken for granted becomes more evident. The once dreaded chore of walking your dog or countless complaints of hectic school schedule are now simply not that bad. The freedom to leave your home and spend time with friends is replaced with face masks, social distancing rules and sheltering in place.

In this month's Asbury Park Press Student Voices Essay and Video contest, we posed the question: What is the most important lesson you learned from having to live through the coronavirus pandemic?

Below are the winning essays and videos for May in the Asbury Park Press Student Voices contest.

First place winner: Grades 7-8

Simple Strolls

When everything was normal in my life, I failed to appreciate the little things in my life. For example, going on walks with my dog was like a chore without pay. To me, it was forced labor. My dog would tug on the leash, and I would try to stand my ground as we awkwardly avoided what seemed like thousands of happy walkers with their barking dogs. People would walk past us, and we would exchange smiles, but it was very boring because I knew there was something they didn't. There is a better way to use my time, I would think: studying, doing homework, exercising, etc. However, once COVID-19, the virus that changed life as we all know it entered the scene like an unwanted guest, I was exposed to another perspective…

7:00 AM Thursday / Day Three of Distance Learning

“Chloe,” my mom yelled, “Hurry, we have to walk the dog before breakfast!”

“Coming,” I replied while I trudged down the stairs. As we walked out the door, I noticed the tension in the air.

Every walker was avoiding everyone else by staying six feet away. No smiles were exchanged. (And even if there were, who would know, they were covered by masks.)

My dog frolicked along like a bad deer impersonator while my mom and I lumbered down the streets. The fog made the walk more depressing. At the end of the walk, while we slumped down my driveway towards the back door, I began to miss the walks that I once hated.

Walking may not seem like much to you, but the coronavirus has taught me to enjoy the little things in life. Before, typical walks with my dog were a bore, but once the luxury was taken away, I began to miss the most boring part of my average day. Luckily, everyone is staying safe. However, when everything returns to normal, I will never take for granted the fun strolls with my dog. I will enjoy the tiny part of my average day.

Chloe LaForge

Spring Lake Heights Elementary School

Teacher: Nicole Kirk

First place video winner:

First place winner: grades 9-12.

Hot Air Balloon

My room is filled with the carnage of apathy. Three empty water bottles slump underneath my dresser. My drawers are neat for once because I’ve been wearing only pajama pants and the same two shirts the entire quarantine. My alarm clock is the only thing that resembles normality, and even that is different. Before this pandemic, I had never used the snooze button. Now, I use it every day.

I’ve always prided myself on being hardworking and capable. If only I had more time, was how my theme song went. More time to cook, more time to read, more time to have the fun you need, my brain would croon to itself. Now I have endless hours to fill with whatever I please. And yes, I’ve cooked meals for my family and finished five books during the quarantine, but I haven’t been having fun. I do these things because I feel like I would be nothing if I didn’t, like I would be incomplete. Because I’m hardworking and capable, but ever since this pandemic I’ve wanted to do nothing but sleep.

During quarantine, I’ve realized that I’m a hot air balloon, filled with hopeful gusts and shiny blue ideas. I need a tether to keep me from soaring away through the clouds to the beckoning land of nostalgic poetry and YouTube videos about eighteenth-century European monarchs. That tether is studying with my friends, visiting a teacher during my lunch break, practicing for the spring musical so late that I have no choice but to get my homework done right after school. I miss feeling like I have something important to do and goals to achieve. Schools everywhere are adjusting to our “new normal” with standardized testing scores waived and school days reduced to only a few video chats. I feel like someone ripped a hole in me. My hot air balloon is getting battered by the waves of uncertainty, and it feels like only a matter of time before it sinks into the thick grayish water.

If I’ve learned anything during the coronavirus pandemic, it’s that I need the hectic normality of my everyday life. I need my friends and my teachers and those homework assignments that never seem to end. Because without them, I don’t remember how to fly.

Kimberly Koscinski

Point Pleasant Borough High School

Teacher: Shannon Orosz

Second place winner: Grades 7-8

Use Your Time Wisely

2020 has been a rollercoaster of events, emotions and some unpleasant surprises. This pandemic has deprived us of many things we took for granted, such as leaving your house or meeting your friends. It shut down businesses and schools, and it made the busiest cities standstill for the first time. During this pandemic, I learned that we should never take what privileges and opportunities we have for granted; and also to enjoy the little things that life has to offer, such as spending time with friends or going out with your family.

Before the pandemic, back in 2019, I used to take for granted my ability to go to school, to get out of my house, and do things on my own. There were countless times when I could have spent more time with friends and family, but instead, I chose to hide away in my room. Sometimes I wish I had gone out more, that I had enjoyed my free time better rather than just looking at a phone screen. It's an understatement to say that school is underrated. We never take time to appreciate how school affects our lives, and how the teachers and classmates influence us. I indeed enjoy having my own time to do work. However, nothing will ever compare to going to a classroom to learn, and having a teacher explain the topic in detail.

I am happy that I've gotten more time to spend with my family. I'm connecting with them more than I had ever before since it was rare for all of us to spend time together. I've also learned some things about myself; there are some things I'm not proud of, but I'm happy I got to know what they were. Now, I can improve myself and my character to be a better person.

This pandemic certainly feels like the end of the world. Still, I know that if everyone follows instructions and stays quarantined, we will be able to overcome it. We don't know what the future has to bring, but hopefully, it will be better than what has already happened. I think it's important to understand that despite having a fortune, money could never buy time, so don't waste it.

Maria Reyes-Hernandez

G Harold Antrim Elementary School

Teacher: Stephanie Woit

Second place video winner:

Second place winner: grades 9-12.

Lessons In Quarantine

It's quite a strange thing to think about, honestly. Everyday we always consider what we could really do if we had just one more hour of time on our hands. What we could achieve with an extra day of personal work. Yet, in a time like today when we have been suddenly thrust into having so much free time stuck at home, we realize just how much of that time we actually had and how much of it we took for granted. If there was anything I learned from my newly awarded hours of contemplation during quarantine, it's this: we should never take our time for granted. Start that personal project you’ve been wanting to head off. Go out on that weekend evening and let yourself unwind. Step back from those obscene work hours and take some time for other things.

Let me paint you a picture. Throw away the quarantine for a second and place yourself in the shoes of what we used to know as normalcy. It's a school night, you’ve got a test in a couple of days and, honestly, you know you’re a shoe in for at the very least a B+. Dinner is being cooked in the kitchen a few doors down from your room, and right as you just settled into bed for a nightly study session, you get a text. Your friend wants you to go party with them tomorrow night. You freeze up for a moment. While parties have never been your scene, you have some small spike in confidence and almost type out a response. However, that burst quickly subsides, and you decline. After all, there'll be plenty more parties and plenty more chances to go out, right? Well, while that might be true, it's a mindset that sets us up countless missed opportunities. Take that decision, and now put it into perspective.

What if that was the last chance you had to ever see your friends in person again? What if that was your last chance to get some time out of your house for two, three, four months? With all that in mind, would you still stay behind? Time is fixed. We only have a certain amount of time, ever, making it just as precious as life itself, something we should seldom take for granted.

Gregory Rivera

Point Pleasant Borough High School

Teacher: Mrs. Orosz

Third place winner: Grades 7-8

The Little Things

The sound of a bell. A noisy hallway. Twenty-two of your peers fills the empty desks. Six incredible teachers, you see throughout the course of your day. It is almost hard to even imagine how a routine so basic can change in an instant. Now no bell. No one surrounds you. You see your favorite teachers through webcams and videos. Your fingers ache from clicking on the keys and you get a headache from the pixels on your screen. After eight long hours of work, all you want to do is see your friend, be able to hug your family and be with the people who matter most. Apparently, that seems like a lot to ask for.

Over these past two months of being stuck inside our homes, we have come to appreciate many things that we take for granted in this world. Now everyone is thinking the same thing, “When can I leave the house”, or, “Is this ever going to be over.” The truth is, it will be over someday. We will all be able to be together again like we used to. There’s no reason for complaining about being in your own home with the people who love you. I have learned to appreciate the little things in life. Because when we can finally go to stores, and eat at our favorite restaurants, you will have a new respect for all the little things that surround you.

Wherever you go on social media, or out on a run, you see these people who completely ignore the rules of doctors and the government who are ultimately trying to keep us safe. I would have never thought that two words could have such an impact on people. Stay home. It is maybe the simplest task that any one person could carry out. But it seems so impossible to people. Stay home with the people who love you. Be with the people who matter. You can go without a haircut or a trip to the gym. Enjoy the little things. An afternoon walk with your dog, or a running workout. The little things. Those are what matters most.

Brady Durkac

Memorial Middle School

Teacher: Lynn Thompson

Third place video winner:

Third place winners: grades 9-12.

Take control

What is the most important lesson you learned from having to live through the coronavirus pandemic?

The most important lesson I have learned from having to live through the coronavirus pandemic is that not everything goes your way. But no matter what’s happening, you must take control of the situation. That means get your work done, deal with what’s being thrown at you in these times, make the most out of it, and never lose your motivation. I find it helpful to invest as much energy as I can into each new day because once this is all over, I don’t want to look back on what I did during quarantine and regret it.