- Accessibility Options:

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Search

- Skip to footer

- Office of Disability Services

- Request Assistance

- 305-284-2374

- High Contrast

- School of Architecture

- College of Arts and Sciences

- Miami Herbert Business School

- School of Communication

- School of Education and Human Development

- College of Engineering

- School of Law

- Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science

- Miller School of Medicine

- Frost School of Music

- School of Nursing and Health Studies

- The Graduate School

- Division of Continuing and International Education

- People Search

- Class Search

- IT Help and Support

- Privacy Statement

- Student Life

University of Miami

- Division of University Communications

- Office of Media Relations

- Miller School of Medicine Communications

- Hurricane Sports

- UM Media Experts

- Emergency Preparedness

Explore Topics

- Latest Headlines

- Arts and Humanities

- People and Community

- All Topics A to Z

Related Links

- Subscribe to Daily Newsletter

- Special Reports

- Social Networks

- Publications

- For the Media

- Find University Experts

- News and Info

- People and Culture

- Benefits and Discounts

- More Life@TheU Topics

- About Life@the U

- Connect and Share

- Contact Life@theU

- Faculty and Staff Events

- Student Events

- TheU Creates (Arts and Culture Events)

- Undergraduate Students: Important Dates and Deadlines

- Submit an Event

- Miami Magazine

- Faculty Affairs

- Student Affairs

- More News Sites

Do we have a moral obligation to help others?

By Barbara Gutierrez [email protected] 04-29-2020

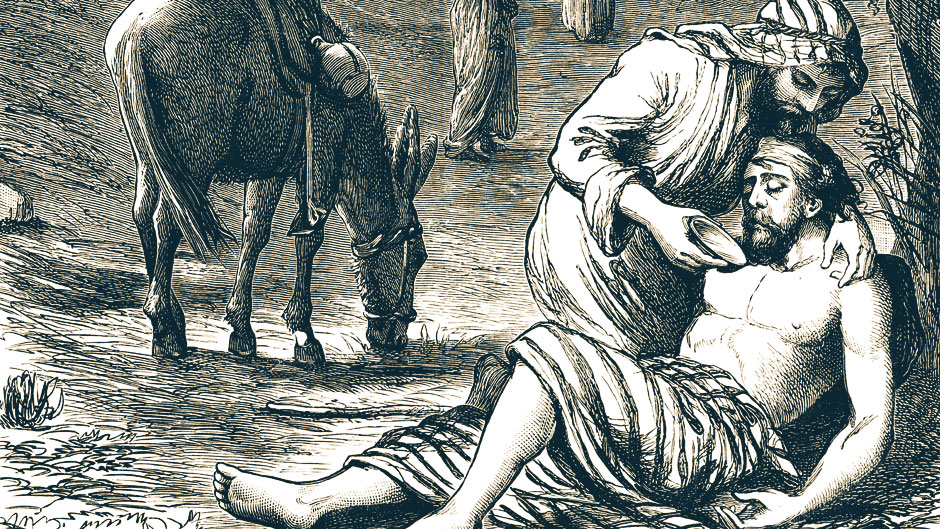

The parable of the Good Samaritan can be helpful in this age of the coronavirus and its painful aftermath.

The Bible tells the story of a man who was robbed, beaten, and left for dead on the road. Two passersby ignore his plight while a Samaritan who sees him, helps him and takes him to safety.

At a time when about 60,000 people have died as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, millions are unemployed, and many others are in need of basic staples such as food, there is a great deal of need.

“There are a lot of people struggling now. And moving forward, things are going to be difficult for a great many,” said Richard Chappell, assistant professor of philosophy at the University of Miami College of Arts and Sciences.

Images of people carrying out good deeds abound on the internet and on television. But there are also troubling images of carefree people gathering at beaches and other public areas without masks and ignoring the physical distancing measures which health officials have said will help keep the virus at bay.

All this begs the question: Do we have a moral responsibility to help others? Do we all have to become Good Samaritans?

“I think most of us who work in ethics believe there is a moral responsibility to others,” said Michael Slote, UST Professor of Ethics in the Department of Philosophy. “It is really also common to the world’s religions and even to the world’s cultures.”

The Hebrew Bible mentions the ideal of helping “widows and orphans and people who are disadvantaged,” pointed out Dexter Callender, associate professor of religious studies.

“The ideal society in the Torah (the first books of the Hebrew Bible) and Deuteronomy is organized around taking care of other people,” he added.

“You get this idea in ancient Judaism and Christianity that you have to love your neighbor; you have to take care of your neighbor,” said Slote. “You have to be responsible to make sure that your neighbor does not suffer too much.”

The teachings of the Torah prompted Jesus to preach that we should “love thy neighbor as thyself.”

Many religious scholars have asked: Who is our neighbor? Are we obliged to help only those close to us, our families, friends, colleagues?

“According to Jesus, our neighbor is anyone we are responsible for,” explained Slote. “It is all of humanity.”

Callender agreed, noting that even in the ancient Hebrew Bible there is a belief that one should help “resident aliens or people who come from other cultures and places, who may not be able to support themselves in the same way as others.”

The Judaic teachings also stress the need to be empathetic of other people and their plight.

“They are constantly told to remember that they were slaves in Egypt,” said Callender. “All the commandments are premised on the memory of being oppressed.”

According to Chappell, besides the religious, “here is a moral principle that states that if you are in a position to prevent something bad from happening without sacrificing anything comparably significant, then you should do it.”

This rule can also extend to helping others financially, if one has the means to do so, Chappell added.

Peter Singer, well-known Australian philosopher and professor of bioethics, has made a reputation by teaching the effective ways of altruism. He believes that societies and individuals can do much more to improve the lives of people living in extreme poverty.

But another biblical parable in the Book of Genesis warns us of why it may be imperative to help our fellow humans.

When Cain kills his brother Abel, God asks him, “Where is Abel your brother?”

Cain answers “I do not know. Am I my brother’s keeper?”

God curses Cain to a life as a fugitive and a wanderer for his crime.

“The narrative teaches us that there are unintended consequences to our selfish actions,” said Callender. “This suggests that it is in our own best interest to be aware of the best interest of others.”

- Coral Gables , FL 33124

- 305-284-2211 305-284-2211

- UM News and Events

- Alumni & Friends

- University Hotline

Tools and Resources

- Academic Calendar

- Parking & Transportation

- social-facebook

- social-twitter

- social-youtube

- social-instagram

Copyright: 2024 University of Miami. All Rights Reserved. Emergency Information Privacy Statement & Legal Notices Title IX & Gender Equity Website Feedback

Individuals with disabilities who experience any technology-based barriers accessing the University’s websites or services can visit the Office of Workplace Equity and Inclusion .

Essay Papers Writing Online

The impact of helping others – a deep dive into the benefits of providing support to those in need.

Compassion is a virtue that ignites the flames of kindness and empathy in our hearts. It is an innate human quality that has the power to bring light into the lives of those in need. When we extend a helping hand to others, we not only uplift their spirits but also nourish our own souls. The act of kindness and compassion resonates in the depths of our being, reminding us of the interconnectedness and shared humanity we all possess.

In a world that can sometimes be filled with hardships and struggles, the power of compassion shines like a beacon of hope. It is through offering a listening ear, a comforting embrace, or a simple gesture of kindness that we can make a profound impact on someone else’s life. The ripple effect of compassion is endless, as the seeds of love and understanding we sow in others’ hearts continue to grow and flourish, spreading positivity and light wherever they go.

The Significance of Compassionate Acts

Compassionate acts have a profound impact on both the giver and the receiver. When we extend a helping hand to others in need, we not only alleviate their suffering but also experience a sense of fulfillment and purpose. Compassion fosters a sense of connection and empathy, strengthening our bonds with others and creating a more caring and supportive community.

Moreover, compassionate acts have a ripple effect, inspiring others to pay it forward and perpetuate kindness. One small act of compassion can set off a chain reaction of positive deeds, influencing the world in ways we may never fully realize. By showing compassion to others, we contribute to a more compassionate and understanding society, one that values empathy and kindness above all else.

Understanding the Impact

Helping others can have a profound impact not only on those receiving assistance but also on the individuals providing help. When we lend a hand to someone in need, we are not just offering material support; we are also showing compassion and empathy . This act of kindness can strengthen bonds between individuals and foster a sense of community .

Furthermore, helping others can boost our own well-being . Studies have shown that acts of kindness and generosity can reduce stress , improve mood , and enhance overall happiness . By giving back , we not only make a positive impact on the lives of others but also nourish our own souls .

Benefits of Helping Others

There are numerous benefits to helping others, both for the recipient and for the giver. Here are some of the key advantages:

- Increased feelings of happiness and fulfilment

- Improved mental health and well-being

- Building stronger connections and relationships with others

- Reduced stress levels and improved self-esteem

- Promoting a sense of purpose and meaning in life

- Contributing to a more compassionate and caring society

By helping others, we not only make a positive impact on the world around us but also experience personal growth and benefits that can enhance our overall happiness and well-being.

Empathy and Connection

Empathy plays a crucial role in our ability to connect with others and understand their experiences. When we practice empathy, we put ourselves in someone else’s shoes and try to see the world from their perspective. This act of compassion allows us to build a connection based on understanding and mutual respect.

By cultivating empathy, we can bridge the gap between different individuals and communities, fostering a sense of unity and solidarity. Empathy helps us recognize the humanity in others, regardless of their background or circumstances, and promotes a culture of kindness and inclusivity.

Through empathy, we not only show compassion towards those in need but also create a supportive environment where everyone feels valued and understood. It is through empathy that we can truly make a difference in the lives of others and build a more compassionate society.

Spreading Positivity Through Kindness

One of the most powerful ways to help others is by spreading positivity through acts of kindness. Kindness has the remarkable ability to brighten someone’s day, lift their spirits, and create a ripple effect of happiness in the world.

Simple gestures like giving a compliment, lending a helping hand, or sharing a smile can make a significant impact on someone’s life. These acts of kindness not only benefit the recipient but also bring a sense of fulfillment and joy to the giver.

When we choose to spread positivity through kindness, we contribute to building a more compassionate and caring society. By showing empathy and understanding towards others, we create a supportive environment where people feel valued and respected.

Kindness is contagious and has the power to inspire others to pay it forward, creating a chain reaction of goodwill and compassion. By incorporating acts of kindness into our daily lives, we can make a positive difference and help create a better world for all.

Creating a Ripple Effect

When we extend a helping hand to others, we set off a chain reaction that can have a profound impact on the world around us. Just like a stone thrown into a calm pond creates ripples that spread outward, our acts of compassion can touch the lives of many, inspiring them to do the same.

By showing kindness and empathy, we not only make a difference in the lives of those we help but also create a ripple effect that can lead to positive change in our communities and beyond. A small gesture of kindness can ignite a spark of hope in someone’s heart, motivating them to pay it forward and spread compassion to others.

Each act of generosity and care has the power to create a ripple effect that can ripple outwards, reaching far beyond our immediate circles. As more and more people join in this chain of kindness, the impact multiplies, creating a wave of positivity that can transform the world one small act of kindness at a time.

Building a Stronger Community

One of the key benefits of helping others is the positive impact it can have on building a stronger community. When individuals come together to support one another, whether it’s through acts of kindness, volunteering, or simply being there for someone in need, it fosters a sense of unity and connection. This sense of community helps to create a supportive and caring environment where people feel valued and respected.

By helping others, we also set an example for those around us, inspiring others to also lend a hand and contribute to the well-being of the community. This ripple effect can lead to a chain reaction of kindness and generosity that can ultimately make the community a better place for everyone.

Furthermore, when people feel supported and cared for by their community, they are more likely to be happier and healthier, both mentally and physically. This sense of belonging and connection can help to reduce feelings of isolation and loneliness, and can improve overall well-being.

In conclusion, building a stronger community through helping others is essential for creating a more positive and caring society. By coming together and supporting one another, we can create a community that is resilient, compassionate, and unified.

Related Post

How to master the art of writing expository essays and captivate your audience, convenient and reliable source to purchase college essays online, step-by-step guide to crafting a powerful literary analysis essay, tips and techniques for crafting compelling narrative essays.

Intellectual Roundtable

Asking — and answering — life's interesting questions

What Are Our Responsibilities To Others?

In pre-flight instructions, you are always advised, in the case of emergency, to take care of yourself before assisting others. This makes sense, because you won’t be able to help another if you yourself are in jeopardy.

This reasoning could be extended, however, to never actually helping anyone other than yourself. That doesn’t seem right. Helping others can end up helping you — a rising tide lifts all boats, as the saying goes.

Related: Listen to an episode of the Intellectual Roundtable Podcast, where Lee and Michael discuss this question: ‘What are our responsibilities to others?’ We also discuss another question as well, ‘Are we too busy?’

A balance between yourself and others needs to be found. Hence the question: What are our responsibilities to others?

Related questions: What is the best way to help others? What is the best way to help yourself?

Spread the word about Intellectual Roundtable:

3 thoughts on “what are our responsibilities to others”.

In essence, is their a social contract or a moral contract that we are bound to by a religion or a society? Some religious views on the subject are very dogmatic one way or another on the subject. The legal state weighs in as well as with constitutions, statutes, and regulations. Many institutions we join (work places, community organizations, etc.) also define these obligations the way they see them. However, this question seems to be coming from a more personal and philosophical place.

I don’t want to go too far down the path of formal ethical theory with my response. While it’s interesting to debate the difference between broad ethical standards — like virtue ethics (embodying virtues of mind and character), utilitarianism (the best outcome for the most people), duty of care, pragmatism, etc. — I’m really much more interested in how the question FEELS to people. In that regard, George Lakoff in Moral Politics provides some great insight for me. He argues that we think in metaphors, develop moral judgments using metaphors, and the principle metaphor we apply is “the family,” which we project onto everything including society as a whole.

In the modern American context, Lakoff sees two competing family metaphors: Strict Father, and Nurturant Parent. These are two different competing moral views that see our responsibilities to others very differently. The Strict Father view sees a world based on competition in which the ultimate goal is self-sufficiency and the greatest capacity you can instill in others is the self-control necessary to achieve self-sufficiency that you reinforce in them through strict punishment. The Nurturant Parent view on the other hand sees the world as neither inherently hostile or friendly, but rather what we collectively make it. Therefore, the greatest capacities you can instill in others are empathy and compassion in order to be able to exercise self care and care for others in order to most fully develop.

When it comes to my personal view on our responsibilities to others, it certainly falls in line with the Nurturant Parent view. But, also the pragmatic ethics tradition, since my views were really crystalized as a young adult by some traditional community organizing concepts. In organizing, you focus on finding that middle group between selfishness (denying others) and selflessness (denying yourself) that represents enlightened self interest. You pursue your individual interests while taking the interests of others into account, and your also recognize that their are collective interests to pursue as a group. From both perspectives, Nurturant Parent and pragmatic ethics, the best way to help others is to do things with them, rather than either competing with them or doing it for them.

Practically and philosophically, I believe that there is enough bounty in the world for us all to thrive. Societally, our responsibilities to others comes in constructing systems that foster proper individual and community growth. Materially, yes. But also it’s in coming to realize the conditions that help individuals reach their full potential and build communities that foster bonds to each other so we care enough to contribute to the common good.

On the other hand, and practically, our systems (e.g. financial, municipal ordinances, agricultural, treaties, etc.) do not reinforce the building of a common good. If budgets — individual, communal, nationally, and between nations — reflect values, we value wealth accumulation and stability. Bounty for an elite (to whom some say have proven and deserve their worth) as well as national and international agreements. The latter two reflect budgets and systems that use might to ascribe right.

I could go on for a long time describing the paragraph above, but I’ll save that for questions if people want to ask specific questions. Let me just restate succinctly that we need a more perfect union … one that binds us together in a way embraces potential versus stability.

Reading history from the days of the cave men to the present makes me think that it is the human destiny to become more and more dependent on each other. This dependency on the group leads to a responsibility to the group. That seems to be the essence of civilization. Interdependency generally adds to the prosperity of a culture, but it does not automatically lead to the equality as one might wish. But, those groups that unite seems to become stronger as they grow in number. Individual tribes are no match for a nation state; they don’t have the resources. Yet, the strength and cunning of the individual is still necessary and adds to the strength, ingenuity and prosperity of the group.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Have you a moral duty to care for others?

Kant’s lesson for nursing home operators: people shouldn’t be treated simply as a means to an end.

Immanuel Kant: ‘The duty of care includes care of oneself’

:quality(70)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/irishtimes/b0febe96-5e9f-4939-a43b-d43796138686.png)

The controversy surrounding the Tuam mother-and-child home has highlighted how societal values have changed in Ireland. We have a radically different concept today of what it means to treat people with dignity and respect.

The controversy also challenges us to ask questions today about the role of carers. Is caring primarily the responsibility of the state, families or individuals?

Manus Charleton, author of Ethics for Social Care in Ireland: Philosophy and Practice (Gill and Macmillan), and a lecturer in ethics and social policy at Sligo Institute of Technology, has reflected deeply on this question, drawing on philosophical thought through the ages. He provides today's very Kantian idea: People shouldn't be treated simply as a means to an end.

Is caring for people a moral option or a duty?

Manus Charleton: “There are different views. For Hobbes, our nature is to seek power to satisfy our own desires. This is facilitated through a social contract between the people and government in which caring is left as a choice. We should be fair and kind to others, but only because it helps make for a society suited to pursuing our own interests.

"Kant saw caring as a duty that arises from universal moral laws. We could not rationally will a universal law that no care be provided to others because it entails that no care should have to be given to us. He's not saying, 'I'll help you, provided you help me.' He argues we would be in breach of our nature as rational human beings if we claim we have no duty of care.

“He calls it an ‘imperfect’ duty. This is because neither we (nor the State) can possibly care for everyone in all the ways needed. So we decide the amount and kind of care we give. But we become good people by how well we live up to the duty.

“In recent decades some moral philosophers have emphasised caring as a natural human emotion and disposition. They have pointed out that we need and benefit from care throughout our lives, from parents, family, friends and the State. On this view we should nourish and practise caring in all aspects of our lives – personal, social and work-related – to reduce misery and hardship and realise our humanity.”

How does a nursing-home manager avoid treating clients as a means rather than an end?

“The manager has to respect their autonomy. This is what Kant meant when he gave as a moral law that we should always treat people never simply as a means but always at the same time as an end.

“Kant recognised we naturally treat people as a means to some need or desire of our own. The manager treats residents as a means for employment. However, the manager is wrong to treat residents simply for this means or some other.

“At the same time the manager has to regard each person as their own end, which is as a unique individual with a right to be consulted and involved in all aspects of their care.”

You have looked at how such principles might transfer to other sectors, such as financial services. So what would Aristotle make of the Irish banking crisis?

“He would see the crisis in the banks as an example of what can happen when people ignore the requirement to manage their desires for both their own good and the good of society, which are interdependent. We are naturally social creatures from the existence of family, friends and society.

“Most desires, too, are natural and good. But if we give in to them too much it can turn out to our detriment, for example, if we take risks while ignoring the need to act with prudence and consideration for the wellbeing of others. He explains how to develop character qualities by making a rational choice to act according to the midpoint between excess and deficiency of desires and feelings. For example, acting with courage is midway between the excess of recklessness and the deficiency of timidity.

“This is the idea of the golden mean. It’s the way to act with power or excellence, which he understood as virtue. Also, he was aware from Greek drama how luck or fate can up-end us when we take unjustifiable pride in our apparent success and become blind to danger signals and heedless of warnings.”

Would it be ethical to outsource caring in the future to robots?

“Caring shouldn’t be depersonalised. It’s a natural human impulse and interaction that has to be nuanced to an individual’s needs and personality. And it includes being sensitive and responsive to often complex feelings in ways which can’t be predetermined.”

Does one have a responsibility to care for oneself?

“Yes. For Kant the duty of care includes care of oneself. Respect for oneself is also a duty along with respect for others. And for Aristotle selfcare is bound up with a natural desire to realise our own potential.”

Is ‘flourishing’ only a young person’s game? What does it mean to flourish in one’s old age?

“I think Aristotle was right in identifying the core of flourishing with making our own rational decisions about how to respond to our feelings and desires towards various situations that arise for us every day. This is how we form our character.

“As for the art of living, he recognised how hard an art form it can be, especially when we have to cope with adversity. But in old age we can still practise the art. It’s important for our self-respect, self-esteem and for how we would like others to see us. And we can hope to be better at it if we’ve learnt from experience.”

Question: Is fear of Friday the 13th a harmless tradition?

David Hume replies: "Superstition is favourable to priestly power . . . The stronger mixture there is of superstition, the higher is the authority of the priesthood."

Twitter @JoeHumphreys42

IN THIS SECTION

The black keys in dublin: gritty show gives people what they wanted, especially towards the triumphant finish, pains and gains: paschal donohoe on three books about economic growth, bryan dobson: ‘retirement could be a terrible shock to the system – or not, who knows’, beating the drum for preserving the language and culture of canada’s indigenous nations, passion, booze, madness and comradeship: bruce springsteen’s special relationship with ireland, man jailed for ‘predatory’ attempted rape of woman in toilets in dublin city bar, brothers awarded €95,000 each over mistaken arrest for grafton street handbag theft, ‘we don’t speak, we don’t eat, we don’t do anything together’: inside an irish divorce court, in ireland today, only rich people can afford to live in houses originally built for poor labourers, uk accepted return of 201 migrants from ireland under current deal but none was sent, latest stories, at least nine killed in strike on displacement camp in eastern dr congo, we shouldn’t import broken british rhetoric about migration, a tech entrepreneur chases immortality: bryan johnson is 46. soon, he plans to turn 18, i spent my maternity leave in a chemo chair. then i got a letter telling me to go back to work, maybe now the irish government will accept that the uk and unionists had a point about open borders.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/SJQTLMCMMRC2PLALXUKEWWS6HU.png)

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Information

- Cookie Settings

- Community Standards

Individuals have a moral obligation to assist people in need

Do-Gooders, philanthropists, humanitarian people, the ones who care; gotta love ’em. But is it always good to care? I’d like to relay a story my principal related to the school long ago: Once upon a time there was a caterpillar stuck in its cocoon and a goodly well-meaning stranger grabbed his scissors and clipped the cocoon for it. Now if the caterpillar had struggled a little longer he would come out unscathed but thanks to the goodly stranger a one-winged butterfly clumsily jumped out forever crippled.

All the Yes points:

But individuals are people in need, consequentialism – we must reduce overall suffering, helping people reduces suffering in the world, virtue ethics – we become better people, all the no points:, it’s none of your business, only help those who ask for it and that too at your discretion, moral obligation, virtue ethics, yes because….

So you’re essentially saying that people should help themselves and others? In modern philosophy the stress on ‘help’ and ‘cooperation’ is very pronounced. If the goal is to optimize well-being then this should be the logical course of action. If you want the world to be a livable, better and wonderful place. Do unto others …

No because…

Hedonism, humanism and hatred are all essential parts of a healthy human psyche. There will be times that you won’t get put of bed because you don’t want to. There will be times when you will feel the urge to kill don’t act on it, there will be times that your heart will be broken and you will break other people’s hearts. There is no way around creating needs, denying needs and so on, as such you are not obligated to doing anything. You don’t owe the world or the children or humanity anything. But since we all also have the desire to help, give and be liked (as Hobbes would put it, even selfless acts are selfish) we should but there still should not be an obligation, as such. [[http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HwNFiffOKic]]

Consequentialism says that we must minimize suffering and provide the most help to the greatest number of people. Helping those in need would reduce such suffering. Moreover, $20 to an affluent person is much less valuable than $20 for an impoverished person. Thus if the affluent person donates that $20 it reduces more suffering than if they use it themselves.

I understand we may minimize suffering but we should not be morally obliged to do so. For, moral obligation does not exist. It is just the feeling of guilt that pushes us to donate, or give charity.

Although it might seem a bit vacuous, virtue ethics states that when we act righteously we become more complete persons. Thus the most moral action for ourselves, would be to help others and, in doing so, become more virtuous persons.

According to Rawls, we are selfish. Therefore, we are doing things for our own benefit. We do not become a more virtous person but we obtain something. We also tend to do things for our own fulfillment. If you are doing something for yourself, you are not being virtuous.

Empathy is the ultimate virtue. Only when acting out of empathy do we understand other people, meaning that the only way we can understand others and our obligation to them is through empathy. When we do empathize with those in need, we understand their pain and need, and so we are obligated to help them.

That aruguement makes a separation between obligations and understanding. Essentially, if one understands another and their pain, a moral obligation is thus created. This means that it is not a moral obligation that we have to help peole, but a problem of understanding. Some could then create a meaning or create an understanding that compels them to assist another. The logic then is flawed because it leaves understanding up to the individual as well as what assistence they are to act upon to fix what they understand. If that is the case, the overal goal would then never be accomplished. It thus places the power to define all relavent terms into each and every individual. This is counter productive because this would cause more harm then good. The reason for not having a moral obligation to assist a person in need would be because one can never truly understand whether or not the need is ralavent or if the assistence is even fruitful. I then ask what makes up a moral obligation?

Sure, everybody’s in need but that is no excuse to bother a homeless person sleeping in a garbage can or pooping in the park It is horrible enough that this person has to sleep there or poop there, the indignity of his/her circumstances is only worsened with your pity or your food throwing or what you call help. Every human being has the right to be left alone and not be judged or interfered with.

Sometimes people refuse help when it is good for them. For example, not wanting to swallow bitter medicine despite being very very sick. [[http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=djQdI1t9_Ag]]

Suppose someone ‘needs’ to have sex and comes up to you and asks you to do it. It is not your moral obligation to help, okay. Kids today! Just because someone has asked you do something or if someone needs something, is not obligation to go ahead and help them. [[http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q99JgYrgzco&feature=related]] If you want to help people and they want your help then by all means do so, but otherwise there’s no ‘obligation’ per se. Free will, exercise it. [[http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q99JgYrgzco&feature=related]]

A way to assist the person in need of sex would then be to change what it is they need. You are not obligated to have sex with them, you are however obligated to assist them in not having to have sex in the first place. This essentialy means we perscribe ourselves to knowing the best way to help a need. The way to do this would be to abide by a legitamite government which operates under the notion orf morals. It is throught these morals that we obtain an understanding of justice. Justice is thus assisting those in need. The foundation for justice is morals. Anyone living under a legitamite government not only has a moral obligation to assist a person in need, but continuosly practice this. The citation of ‘Free will’ was only understood because of a moral foundation. To exercise that right would then obligate you to abide by the laws created by the government. By obeying those laws you assist others by creating a society that minimized pain and suffering as well as maximized understanding.

A moral obligation is an imperative. As good as philanthropy is and that it improves the world, it should not be required. Morally one’s task should be to do the right thing by improving oneself rather than others first.

If one advocates for the moral advancement of obeself, then they also understand that there is a moral reason behind it. By bettering oneself they assist others. It then brings truth to the notion that “Individuals have a moral obligation to assist a person in need.”

Although helping people in need is an honorable thing to do, when we tell people that they are “obligated” to help, those on the receiving end will develop a laziness or dependence upon others. Now said person is ALWAYS in need help and ALWAYS want more. This makes them a serious drain on society and a serious drain on my wallet. <—(yes… i’m a capitalist)

they are called “tax-write offs”. Not only is it cool its saves you, ….ahem….i mean me money. <—-(yes….i’m a capitalist)

Virtue ethics states that when we act righteously we become more complete persons. Thus the most moral action for ourselves, would be to help others and, in doing so, become more virtuous persons. this is actully a yes and not a no but anyway….

I guess this will be no then. Virtue ethics is a good point in this topic but lets also think about the true outcome of helping someone. You could endanger yourself in the process. If you see a person badly beaten, are you going to stop and help? I wouldn’t. Teach people to act righteously in other ways.

We would love to hear what you think – please leave a comment!

Hey dave. Nice article!

Why Do We Help Others? The Morality Preference Hypothesis

We often help others. In most cases we help friends, family members, or colleagues. However, in some situations, we also help people with whom we have no connection whatsoever, for example, when we donate our change to a homeless person along the street, or when we give part of our salary to a humanitarian organisation. Although it is not very common, there are also well documented cases of people putting their life at risk to save strangers, or even animals, like the man in California who jumped into a wildfire to save a rabbit .

This is quite strange, right? Helping random people, or even animals, does not bring us any obvious direct or indirect benefit and thus it seems to go against the classic academic assumption that helping behaviours evolved because they provided benefits to the helper. For example, if I help my friend today they will help me tomorrow. It is not surprising, then, that understanding helping behaviour towards strangers has become one of the greatest challenges in social science research.

There can be many reasons why people help each other.

How can we explain it? The starting point is to turn to laboratory experiments using simple economic problems that are meant to model the essence of helping behaviour using a unit of measurement that is as objective as possible; most often, money. As for the decision problem, the most used one is called the ‘Dictator Game’. Here, a person, the dictator, is given a certain amount of money and is asked how to split it with an anonymous stranger, the recipient, who is given nothing. The recipient does not make any choice and only receives what the dictator decides to give them. Clearly, a purely self-interested dictator would give nothing to the recipient, because giving has neither direct nor indirect positive consequences for the dictator. However, mirroring what we see in everyday life, empirical research has repeatedly shown that a significant proportion of dictators give part of their money to the stranger. Why so?

[the_ad id=”11275″]

To explain these results, behavioural scientists have typically turned to something called ‘ social preferences ‘. In the case of giving money in the dictator game, a useful way to explain this behaviour is ‘ inequity aversion ‘, which is a type of social preference. Inequity aversion assumes that people experience psychological disutility (discomfort) from economic inequalities. To avoid this disutility, thus, some people will turn out to donate part of their money. This might explain why a significant proportion of dictators appear to give money to anonymous recipients.

Is this the whole story? Do people care only about the economic consequences of their actions? Or are there people who care also about doing the right thing, independently of the economic consequences?

In a recent series of papers, my collaborators and I have shown that, indeed, people seemed to be motivated also, and, actually, mainly, by reasons beyond the economic consequences of their actions. Specifically, dictators seem to be donating to recipients not because they are motivated by minimising the inequity between themselves and the recipient, but because they believe that sharing their money is the morally right thing to do.

This point is illustrated in a paper co-written with Dave Rand at MIT that was published in January 2018 in the academic journal Judgment and Decision Making . In that paper, we introduced a ‘trade-off game’ , a decision problem that helps distinguish people with social preferences for minimising economic inequalities from people with moral preferences for doing the right thing, beyond its economic consequences. Comparing the average amount of dictator game giving among inequity averse participants with the average amount of giving among moral participants, we found that the latter ones donate significantly more than the former ones, providing clean evidence that giving is mainly driven by moral preferences for doing the right thing.

In a subsequent work conducted with Ben Tappin at Royal Holloway University of London , published in June 2018 in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology , we replicated this result and extended it by showing that preferences to do the right thing are equally strong as preferences to avoid doing the wrong thing when giving money in the dictator game.

Do people care only about the economic consequences of their actions?

Together, these studies provide robust evidence that helping behaviour in the laboratory is not driven by social preferences for minimising inequities per se, but is mainly driven by moral preferences for doing the right thing.

Of course, this finding raises a number of important questions that should be explored in further research.

For example, thus far we have focused on laboratory behaviour involving relatively small amounts of money. Exploring whether morality preferences extend to real behaviour and/or situations in which stakes are much higher (think about the Californian guy who jumped into the fire to save a rabbit), is an important direction for future work. In these cases, it is difficult to make predictions. On the one hand, one might think that larger stakes will make people more caring about the economic consequences of their actions; on the other hand, one might also think that there is a subclass of subjects for which moral preferences are relatively stake-independent (perhaps among deontologists, i.e., people for whom the rightness or the wrongness of an action does not depend on the consequences of that action, but only on whether that action instantiates or violates certain moral norms and duties?).

When we are helping others, some people make us happier.

Another important question concerns the path through which people construct moral judgements in a given context. What are the cues that make people conclude that one action, among all the available ones, is the morally right one? This is likely to be a multidimensional question. In a working paper, co-written with Andrea Vanzo , a linguist at the Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh, we have observed that one dimension is certainly important – the language used to describe the available actions.

We have shown that simply changing one word in Dictator Game-like instructions can dramatically change people’s behaviour. For example, people are less likely to steal money from another participant than to take money from another participant, although ‘stealing’ and ‘taking’, in the given contexts, have the same economic consequences. Therefore, it seems that people use the language used to describe the available actions to deduce properties about the moral qualities of the corresponding actions.

In sum, this line of research provides evidence that helping behaviour in the laboratory has not much to do with minimising economic inequalities, but it is mainly driven by moral preferences for doing the right thing. Exploring the boundary conditions of this morality preference hypothesis and studying how people build moral judgements are fundamental directions for future research.

Related Articles

Why do online communities become hyper-toxic, it’s all in the smile: aston university-led research finds politicians can influence voters with facial expressions, study reveals higher injury and assault rates among nyc food delivery gig workers dependent on the work, unlock the world: 5 tips for communicating abroad when you’re lost in translation, i love the west. but sometimes i hate their hypocrisy, the uplifting power of communities, the psychology of fashion – how our choice of clothing reflects and shapes our identity, new report reveals 10 most dangerous uk cities for pedestrians, new bbc documentary sheds light on violence against women and police misconduct in the sarah everard case, effort-based self-interest motivation negatively impacts altruistic donation behaviour, moral heroes and underdogs win our hearts in fiction, finds new study, study reveals lower volunteering in diverse us states – trust key factor, the type of white normativity that activists convieniently ignore, how animal cruelty images on social media affect our mental well-being, observing how repeated social injustice can significantly impact mental well-being, digital media fuels jihadist radicalisation in australia, finds study, study shows social media’s influence on islamist militancy among bangladeshi youth, new book offers in-depth exploration of forensic psychology’s role in legal systems, new study reveals how depression influences political attitudes, a guide to using the insanity defence in a criminal trial, study finds shaky connection between moral foundations and moral attitudes, study shows vaccination alters body odour and facial attractiveness, resolve to be greener: seven easy, small steps freelancers and sole traders can take to be more sustainable in 2024, “they don’t like you because you’re black” – injecting racial poison into children’s minds.

Psychreg is a digital media company and not a clinical company. Our content does not constitute a medical or psychological consultation. See a certified medical or mental health professional for diagnosis.

- Privacy Policy

© Copyright 2014–2034 Psychreg Ltd

- PSYCHREG JOURNAL

- MEET OUR WRITERS

- MEET THE TEAM

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Obligations to Oneself

Moral philosophy is often said to be about what we owe to each other. Do we owe anything to ourselves?

Philosophers are torn. On the one hand, obligations to self are a mainstay of moral theories – most famously Kant’s – as well as ordinary thinking. It is not just academic Kantians who believe in making something of our lives and standing up for ourselves. And yet, the idea of literally owing things to oneself can sound paradoxical. When I owe you $5, I am bound to pay. When you owe me $5, I can waive the debt away. Now suppose I owe myself $5. Don’t I then have the power to waive my own obligation? But then how could it bind me? An obligation I can escape at will is like a prison with an open gate, a speed limit with no penalty. Such an obligation seems powerless, toothless, imperceptible – in other words, it seems like no obligation at all.

This paradox has cast a long shadow. In the 20 th century, obligations to oneself “largely disappeared from the radar of academic philosophers” (Cholbi 2015, 852), as the traditional question of what we owe to ourselves gave way to doubts about whether such obligations are even coherent.

But in the new century, the topic has enjoyed a renaissance, with fresh theories cropping up for the first time in decades and applications arising across a range of fascinating issues: privacy and promises, self-respect and supererogation, tech-addiction and tattoos. Some have even wondered, echoing Kant, if the topic might lie at the very heart of ethics.

We begin with the question of what obligations to oneself are supposed to be (§1). From there we lay out the “paradox” and its history (§2), along with the three theories that have arisen in response (§§3–5). We conclude (§7) after a survey of applied issues (§6), focusing on topics of broad interest, but sprinkling in a few specifics – like Kant’s qualms about haircuts – for the sake of spice.

1. What is an obligation to oneself?

2. the paradox of self-release, 3. denying obligations to oneself, 4. unwaivable obligations to oneself, 5. waivable obligations to oneself, 6.1 suicide, 6.2 supererogation, 6.3 self-promises, 6.4 body modification and self-expression, 6.5 self-knowledge.

- 6.6 Self-respect

6.7 Privacy

7. conclusion, other internet resources, related entries.

The traditional examples of obligations to oneself are a hodgepodge, but they basically come in two kinds: self-care and self-respect (Allen 2013, 854). Self-care is a matter of promoting our own interests – pursuing our dreams, minding our health, preserving our lives. Self-respect, meanwhile, is less about what is good for us, and more about what is proper or dignified; think of prohibitions on safe and profitable sex work, or taboos around painless suicide even in the shadow of an agonizing terminal disease. As these examples show, self-care and self-respect can be in tension. “Disrespecting” oneself might be the best way to escape a miserable death or a life in poverty.

The tension here is so deep that many philosophers claim to only believe in one of these two kinds of duty, while totally rejecting the other. At one point in his Lectures on Ethics [ LE ], Kant suggests that we only owe ourselves respect: “self-regarding duties…have nothing to do with well-being and our temporal happiness” ( LE 27:341). [ 1 ] Utilitarians, who think morality is all about well-being, are open at most to duties of self-care; they do not share the Kantians’ concerns about ending one’s life or selling access to one’s body when the result is greater well-being overall (see, e.g., Meiland 1963).

With such stark disagreement, it is natural to wonder if the debate here is really focused on a single concept of “obligations to oneself.” In fact, it is often not. The variety in the examples reflects a more basic variety in concepts. The most crucial distinction here – essential to everything ever written on duties to oneself – is between an obligation owed to oneself, and one merely regarding oneself.

Suppose you promise your friend to stop wearing tacky hats. As a result of the promise, you owe it to your friend to dress better; in this sense, the obligation is “to” your friend, not to you. But this is still an obligation regarding you, in the sense that it concerns what you do to yourself. You are the one whose headgear is at issue. (This sort of example is common in the literature; see, e.g., Mavrodes 1964, 165–66; Timmermann 2006, 506.)

It is an open question what an obligation to someone consists in, if it is something over and above mere regard (see Thompson 2004 on “bipolar normativity,” Darwall 2006 on “second-personal” address, and Schofield 2022 [Other Internet Resources]). “Interest theories” say that an obligation to you is somehow linked to what is good for you (see, e.g., Raz 1986, chap. 5). “Standing theories,” which are more popular in writings on obligations to oneself, say that obligations to you put you in control. For Gilbert (2018) and Darwall (2006, 18), the distinctive thing is that you have the standing to demand what is owed to you. For Schofield (2021, 52), the key is that you get “a rightful say.” For Steiner (2013), you have the power to waive the obligation via your powers of consent.

Suffice it to say, the exact essence of an obligation to oneself is still up for debate. By contrast, everyone knows what self-regarding obligations are, and everyone agrees that we might have them – duties to maintain one’s health so as to take care of one’s family; to wear a mask to avoid spreading contagion; and so on. Indeed, it is hard to imagine an obligation that isn’t somehow self-regarding.

It is far more controversial to say we have bona fide obligations to ourselves – that is, owed to ourselves, strictly speaking, just as you might owe it to your friend to keep your promise. The idea of literally owing something to oneself seems to imply that we have rights against ourselves, along with the power to release ourselves from duties (see §2, below). To avoid this paradox, many traditional “obligations to oneself” have been recast as, or replaced with, obligations merely regarding oneself. Aristotle argues that suicide is not an “injustice towards oneself,” but only towards the state that one is supposed to serve (1138a 4–1138b 11). Some argue that self-care is not owed to oneself, or even to others; it is obligatory only in the sense that we have to do it. (It is an “undirected” rather than a “directed” obligation.) And the duty to develop one’s talents might be seen as part of a duty to promote the good of others: think of a lifeguard swimming laps or a surgeon doing hand exercises.

Another way around the paradox is to say that obligations to oneself don’t imply any quixotic power of self-release. To make this view work, we need some way of interpreting “obligations to oneself” so that they aren’t quite like the legalistic obligations we get from promises and contracts. Some say “obligations” to oneself are in some sense non-legal; others say one can owe things “to” oneself only in an attenuated sense; and some even consider shifting the referent of “oneself” – perhaps we only owe things to our future selves, or one aspect of our psyche owes it to another.

Much as the Liar Paradox shaped modern theories of truth, the threat of paradox has profoundly shaped our theories of obligations to oneself. Let’s take a closer look at the paradox before tracing its influence on contemporary work.

What’s so weird about obligations to oneself?

One thing to note – not quite our topic, but important to clear up – is that many moral wrongs can be done only to other people. You cannot steal your own lunch money, deceive yourself with lying promises, or bop yourself on the head against your own will. Who could be duped by a promise they know to be false? (See Hill, Jr. 1991, 144.) How can one “steal” what one already owns? (See Haase 2014, 365.) How can one will things against one’s own will?

This familiar fact – that some wrongs can be done to others but not to ourselves – is called the asymmetry of possibilities (Muñoz and Baron-Schmitt 2022 [Other Internet Resources]). This asymmetry constrains the scope of self-wronging; some naughty interactions are impossible in the one-person case. But this does not rule out all possible obligations to oneself. There are still plenty of problematic things one can do to oneself: bodily harm, property damage, and so on. Could we wrong ourselves by doing such things, or is there something fishy about the very idea of an obligation to oneself?

Now the real paradox. The tension arises from the dual nature of obligations: they are supposed to be both binding and waivable. Your obligations “bind” you in the sense that you have to comply, other things equal, or else you wrong the person to whom you are obliged. But this person can, if they like, waive the obligation, releasing you from your duty. This duality is perfectly intelligible in the two-person case. If you owe your friend $5 for a fancy coffee, you are bound to pay – you cannot simply opt out, as you might opt out of a mailing list or a volunteer trip. And if your friend wants to unbind you, they can do so unmysteriously, simply by saying “My treat.”

What if you owe something to yourself? Then the “binding” seems to vanish. Since you can willy-nilly waive any obligation owed to you, you can willy-nilly waive any obligation to yourself. Any such obligation is therefore purely optional – which sounds incoherent, like an obligatory hobby or a mercenary passion project.

The modern version of the paradox is due to Marcus Singer (1959, 203), who frames it as an argument with three premises:

- If A has a duty to B , then B has a right against A .

- If B has a right against A , he [or she] can give it up and release A from the obligation.

- No one can release himself [or herself] from an obligation.

Together, these ensure that one cannot have duties to oneself. (“Duties” are just “obligations” with fewer syllables.) It’s a punchy argument. Duties entail rights; rights entail powers of release; but one cannot release oneself from a duty. The conclusion, for Singer, is that one cannot have a duty to oneself; the very idea of such a duty is “self-contradictory” (1958, 203).

Singer’s spin on the paradox is clear and forceful. It also crucially involves the concept of a right, which is used to link duties to the power of release. But otherwise, the puzzle merely echoes several historical sources, which Singer does not cite or engage with (see Cholbi 2015). For example, here is Immanuel Kant.

If the I that imposes obligation is taken in the same sense as the I that is put under obligation , a duty to oneself is a self-contradictory concept. … [O]ne imposing obligation ( auctor obligationis ) could always release the one put under obligation ( subjectum obligationis ) from the obligation ( terminus obligationis ), so that (if both are one and the same subject) he would not be bound at all to a duty he lays upon himself. This involves a contradiction. ( Metaphysics of Morals [ MM ] 6:417) [ 2 ]

Notice the same emphasis on “self-contradiction.” And here is Thomas Hobbes, discussing legal rather than moral obligations:

The sovereign of a commonwealth, be it an assembly, or one man, is not subject to the civil laws. For having power to make, and repeal laws, he may, when he pleaseth, free himself from that subjection by repealing those laws that trouble him and making of new; and consequently he was free before. For he is free, that can be free when he will; nor is it possible for any person to be bound to himself, because he that can bind can release; and therefore, he that is bound to himself only is not bound. (1651 [1994, 174])

“He is free, that can be free when he will” is just another way of saying that one cannot release oneself from a genuine obligation. When self-release is an option, one is never really bound. [ 3 ]

What’s the solution?

We have three options. The first is to follow the argument where it leads – namely, to Singer’s nihilism, on which there is no such thing as a duty to self. The next option, which is the most popular among ethicists, is to defend unwaivable duties to oneself. Finally, some argue that self-release is not as incoherent as it sounds, and that we really do have waivable duties to, and maybe even rights against, ourselves.

The choice between these three options is a crossroads in moral philosophy; in effect, we are choosing the place of the self within moral theory. Singer says there is no place for the self in morality. The Kantians – the chief defenders of unwaivable duties to self – are more likely to place the self at the privileged center. And those who believe in self-release see the self as just one moral person among others, denying or downplay the specialness of one’s relation to oneself.

On what grounds have philosophers chosen one road over the others? Where have their choices led them?

Let’s start with Singer’s view, which is that, as shown by the paradox, there can be no obligations to oneself. There may be self-regarding obligations owed to other people; there may be decisive reasons to be prudent. But no one ever literally owes anything to oneself, morally speaking. On the extreme version of this view, no one even has a moral reason to promote their own interests as such (see, e.g., Finlay 2007).

Singer gets points for dispensing with the paradox. He doesn’t posit duties to self, and he has a principled reason for not doing so: given the possibility of self-release, a duty to oneself would not be binding – which means it would lack the core property of any duty that deserves the name.

The challenge for Singer’s view is that it is revisionary, obliterating half of the classic distinction between duties to self and duties to others – a distinction that “seems well embedded both in traditional moral philosophy and in ordinary moral thinking” (Singer 1958, 202).

Perhaps it is all right for Singer to dispute traditional wisdom. It would not be the first time a tradition got something wrong. Besides, as we have noted, there is an equally distinguished tradition of skepticism about obligations to oneself. Even Kant, the chief defender of duties to self, has wary moments (see §2, 4). Deference to the past isn’t decisive here.

What about ordinary thought? If duties to self are really “embedded” in common sense, that is certainly some reason to reject Singer’s argument, or at least to look for ways out.

Singer himself suggests that we should not take our ordinary moral discourse too seriously. When we talk of duties to oneself, our language “must be metaphorical” (1958, 203). He explains:

To say that someone has a duty to (or owes it to) himself to do something is an emphatic way of asserting that he has a right to do it – that there are no moral considerations against it – and that it would be foolish or imprudent for him not to. (1958, 203)

Similarly, Singer thinks, when you “promise yourself” to do something, you must really be expressing your resolve to do it (see also Haase 2014, 364; Hills 2003, 131–33).

There are three questions we might ask about Singer’s interpretation of ordinary talk. First, Anita Allen questions why we shouldn’t take people literally in these contexts:

Figures of speech abound in language. But in the case of statements about duties to oneself, why suppose we do not mean exactly what we say? A moral theory should explain rather than discount inconvenient moral discourse (2013, 859)

Second, and related, we could ask if Singer’s position does justice to the thoughts behind the talk. Consider a few basic questions: is it morally all right to risk dire injuries to oneself for a cheap thrill? To debase oneself for a few bucks? To accept humiliation from peers for the sake of fitting in? One might well say no , even if these actions are certain to harm nobody but oneself. This is more than a linguistic habit that philosophers should be able to explain. These are considerable – though still contestable – moral intuitions, and the appeal to metaphors may not be enough to overturn them.

Finally, Singer’s view seems to suggest that we should be happy to talk, at least metaphorically, of rights against oneself – which, in fact, we are not. For Singer, “promises to oneself” are just statements of resolve, and “duties to oneself” are exaggerated ‘oughts’. Presumably, “rights against oneself” would be understood metaphorically, as well. And yet, no one is willing to talk of rights against oneself. Why? The answer cannot just be that these rights are “surely nonsense” (Singer 1958, 202). For Singer, duties to oneself by definition entail rights against oneself, so the duties should be at least as nonsensical. This is a fact about ordinary talk that Singer seems unable to account for.

Stepping back from Singer for a moment, there does seem to be something distinctive about the realm of rights, as opposed to other parts of morality. Rights are waived by consent and created by contracts. Rights imply authority. If you rightfully own a bicycle, then when it comes to who gets to ride it, you are the boss. (This is especially clear on “standing theories.” See §1 above.)

We now turn to the most popular response to the paradox, which is to rescue obligations to oneself by airlifting them out of the realm of rights. We can owe things to ourselves precisely because owing does not imply rights or the authority to waive. Even if self-release is impossible, there could still be unwaivable obligations to oneself.

The most popular response to the paradox is to insist that duties to oneself exist while denying that they imply waivable rights against oneself. This means rejecting either the first or second premise of Singer’s argument:

Either duties don’t entail rights, or rights don’t always grant the power of release.

One of Singer’s first critics, Daniel Kading (1959), defends rights without release. Kading says we only have rights against people with whom we have struck some kind of agreement – like a promise or contract – and sometimes, these people aren’t around to release us. They might, for example, be dead. There is no hope of release in such a scenario, and yet the right remains. But even if this correct, it won’t do anything to establish duties to oneself (as Kading seems to admit). There is something fishy about the idea of “agreements” with oneself, and, as Muñoz (2020, 694) points out, the deathbed promise has no one-person analogue. (See Singer 1963, 133–35, for further objections.)

Kading next tries a different maneuver, which has become a classic. He distinguishes two kinds of “obligations-to.” One typically springs from promises and contracts (the “agreement-sense”), and the other has to do with affecting people’s interests (the “benefits-sense”). Kading agrees with Singer that we can’t have obligations to ourselves in the first way, but insists that we can in the second. We are “morally obligated” to “maximize goodness” even when that just means making ourselves happy (Kading 1959, 156).

This same move shows up all over, particularly in the work of Kantian ethicists, who draw not on Kading but on Kant’s distinction between “juridical” and “non-juridical” duties (see MM 6:383, LE 29:117, 632). Juridical duties are external , concerning acts rather than motives, and enforceable by coercion and demands. For example, if you threaten not to pay me the money you contractually owe me, I can demand that you fork over the cash, and I can sue you if you don’t. But I can’t demand that you pay me out of the love of your heart. I can demand only the external act – the forking-over. A non-juridical duty, by contrast, requires the right mindset as well as the right action. Non-juridical duty is, basically, a matter of caring about important things for the right reasons – for example, loving and respecting your neighbors because they matter. Now the key point. For Kant, only juridical duties involve powers of release. If I offer to void the contract, you can get out of your duty to pay me. But there is no way to get release from your duty to love your neighbors because they matter – it is not as if your neighbors can stop mattering at will! (See MM 6:219.)

So here is the Kantian move. We say Singer is right about juridical duties, which really do come with rights and powers of release. There is no such thing as a juridical duty to oneself. But we insist there can still be non-juridical duties to oneself, since these do not imply rights and powers of release.

This move is extremely popular, though not everyone uses the term “juridical.” Wick (1960, 1961) and Knight (1961) distinguish legal from non-legal duties (see also Mothersill’s 1960 reply to Wick, which emphasizes that Wick doesn’t defend “duties” to self in the ordinary sense). Eisenberg (1968) discusses “social contractual” duties. Paton (1990, 225–26) defends “non-contractual” duties to oneself. Hills (2005) rejects the “‘juridical’ model” of duties and defends an unwaivable, non-juridical duty to promote one’s own well-being. Kahn, in 2018, argues that Kant himself should have endorsed a duty to promote one’s own happiness, despite his arguments to the contrary. For a bit more discussion on what Kant thinks we owe to ourselves, see the supplementary document:

Kant on What We Owe to Ourselves

The result is a certain humanistic, rather than legalistic, picture of duties to oneself: they do not have to do with rights and agreements, but instead with caring and valuing; they are not under voluntary control, but instead spring from unchangeable features of our personality, like our capacity to make free choices (in Kant’s case) or our susceptibility to pain (in Hills’ and Kahn’s) – basic things about our psychology that make us human. We can waive our rights at will and go on with our day; we cannot so easily take a break from our humanity.

On this view, there is something called a “duty to oneself” that slips through the jaws of Paradox – definitely a victory. But some object that the victory is hollow: the Kantians have carved out a space for “non-juridical” duties to oneself while totally surrendering to Singer when it comes to the juridical. This objection may have bite if “duties,” as ordinarily conceived, are juridical at heart. It is worth asking: what kind of “duty” doesn’t come with any rights, waivers, or enforcement? Aren’t these the very things that make a duty distinct from a mere value or virtue? Many writers – following the legal theorist Wesley Hohfeld (1913, 1917) – would even say that A’s duty to B just is the flipside of B’s right against A (this sort of right is also called a claim; see e.g., Gilbert 2018; Johnson 2010; Muñoz 2021; Thomson 1990, chap. 1). We might hesitate to go as far as Hohfeld in equating duties with rights. Still, some might wonder what is left after we subtract from a duty its rights-related upshots (Muñoz 2020, 693). Are non-juridical duties really duties at all?

Paul Schofield (2015) defends something closer to an unwaivable juridical duty to oneself. Schofield argues that you owe it to yourself not to cause yourself harm in the future – as you might by smoking heavily in your youth and giving yourself lung cancer. You also owe it to yourself not to hamstring your future choices, as in Derek Parfit’s (1984, 327–28) example of the Russian nobleman, who arranges as a young socialist to prevent his future self from funding conservative causes. Schofield’s picture is this. You owe a certain action to someone when they can legitimately demand that you do it. But you can also imagine demands made by yourself of yourself, from different perspectives within your life. When you smoke, causing yourself to suffer in the future, you can look upon this either from the perspective of the future sufferer or the present smoker. The future smoker – that is, you from your future perspective – could justifiably demand less smoking from you in the present, generating a duty not to smoke. Moreover, you cannot presently waive this duty, since you do not now occupy the right perspective (Schofield 2015, 17; see also Schofield 2019).

This proposal is enormously creative – a leap forward in philosophical thinking about obligations to oneself. No doubt the link between duties, demands, and perspectives will play an important role in future work on the subject. That said, there have been some objections to this form of Schofield’s view. In particular, some worry that it makes our relation to our future selves too chilly and antagonistic, like our relation to a non-consenting other (Kanygina forthcoming; Muñoz 2020, 694–95). If we cannot now waive our duties not to harm ourselves in the future, it seems to follow that we may not impose costs on our future selves, even for our own greater good. This seems too stringent; there is nothing wrong with taking a medication that cures a severe ailment today while causing moderately bad side-effects in the future. Harming oneself can be justified when it makes one’s life better on the whole. In this respect, self-harm is much like doing harm to a consenting other. [ 4 ]

Our discussion so far has assumed, following Singer, Kant, and Hobbes, that self-release is fishy – that one cannot wiggle out of one’s ethical duties. That is the basic reason why Singer gives up on duties to oneself, and it is the basic reason why Kantians insist on decoupling them from waivable rights.

But what if the assumption is wrong? What if you can release yourself from obligations? This brings us to the third and final family of theories, those that allow waivable obligations to oneself. Such theories confront the Paradox of Self-Release head on. Self-release, after all, certainly seems paradoxical. How can we find a way to resist Hobbes’ dictum – “he is free, that can be free when he will” – and how might we clear the air of paradox?

The basic problem, as a reminder, is that a waivable duty to oneself would not be binding, because it would not be possible to violate. One could simply waive the duty “when one pleaseth” to avoid transgression, as Hobbes’ sovereign might suspend your property rights when he wants your stuff.

To meet this challenge, we need some way to show that such duties, despite appearances, could actually be binding.

The trailblazer here is G.A. Cohen. He imagines himself in the sovereign’s predicament, passing a law that he might later want to waive away:

Suppose…that the law is indeed universal, or that it includes me within its scope by virtue of some other semantic or pragmatic feature of it. Then, if I had the authority to legislate it, it indeed binds me, as long as I do not repeal it. (1996, 170)

In other words, even if you can be free at will, that doesn’t mean you are free already . You are free when, and only when, you go through the motions to free yourself. Until then you are bound – in this case, by virtue of your power to make laws that apply to you.

Cohen’s remarks on the subject, though valuable, are brief. Muñoz (2020, 2021) develops the idea into a bigger picture of duties, rights, and waivers. The starting point is a view known as the Self-Other Symmetry: you have the same basic rights against yourself as you have against anybody else. But it is uniquely difficult to violate your own rights, Muñoz says, because the very choice to do what they forbid doubles as an authorization to do it. By choosing to bop yourself on the head, for example, you make yourself into a willing party to the bopping, and thereby waive your right, a bit like if you had consenting to being bopped by someone else. The result is that rights against oneself are real but “finkish” – waived by the very things that normally lead to violations. (The analogy is with finkish dispositions, which are real but hidden by the very things that normally cause them to manifest; imagine a fragile glass that turns to stone whenever something is about to strike it (see Lewis 1997; Martin 1994).)

But if a right is finkish, it is hard to see why it should matter. For all intents and purposes, it is as good as absent. This challenge is pressed forcefully by Schofield:

Traditionally understood, a duty binds a person, irrespective of what she herself decides. The powerlessness to escape it through a mere act of will is, in fact, part of what it is to be duty-bound. So insofar as a person has the power to release herself, the purported duty lacks its characteristic ability to place her in the very condition that we associate with duty. (2021, 47)

And while some might say finkish rights and duties are merely “feeble,” rather than impossible, Schofield (2021, 48) replies that he can see “no reason why we cannot simply deny altogether that they are duties.” Finkish duties “bind” only in the sense that they count as duties; they do not constrain our actions. (But see §6.2 below on rights against oneself as prerogatives.)

Could a waivable duty to oneself have any normative bite, anything to constrain how we may act? For there to be a constraint here, waivers would have to be less than automatic, so that the mere choice to bop myself on the head might not waive my duty not to bop myself.

Schaab (2021) argues that a decision might fail to waive a duty to oneself if the duty and motive come from different perspectives within the agent – as when someone qua philosopher decides to skip the gym to work on a paper even though, qua athlete, they could legitimately demand more exercise. Kanygina (forthcoming) argues that self-release must be autonomous . If my decisions are “akratic, negligent, or confused,” they will not validly waive my duties to myself, and while sometimes my state of mind will double as an excuse, at other times I may be genuinely culpable. Kanygina illustrates with a case:

Linda, a diabetic craving a cake, might tell herself ‘What harm is there in my eating a piece or two?’ Linda is aware of the risks. Being both weak-willed and negligent of her health, she acts frivolously. When she later feels guilty, her guilt seems appropriate. (forthcoming, §3.1)

Indeed, any version of the Self-Other Symmetry will be committed to a version of Kanygina’s view. It is a truism that interpersonal consent can waive rights only when it is informed, voluntary, and competent. A breezy “yes” might not cut it. Given Symmetry, the same should hold in the one-person case. To authorize oneself to act in high-stakes cases – sharing private information, donating a spare kidney, devoting one’s efforts to a cause – the decision must be made carefully in light of the available facts. Even if self-release is possible, that doesn’t mean it’s easy.

6. Applications

In modern moral philosophy, duties to oneself are often treated as an isolated, antiquated topic. Paul Schofield (2021, 6) remarks that “self-directed duties find themselves largely absent from the contemporary philosophical scene,” as attested by the fact that – as of the time of his writing – there was “no standalone entry for duties to self” in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

As readers of this entry will note, such lacunas in the literature are filling up fast. More and more links are being uncovered between duties to self and far-flung moral questions – how we should use our smartphones (Aylsworth and Castro 2021); whether to let companies mine our data (Allen 2013); whether we should “suck it up” in the face of injustice or instead go out and protest (Boxill 1976; Hill, Jr 1991d; Straumanis 1984).

Here we will survey some particularly interesting issues that intersect with obligations to oneself.

The topic of suicide – as studied by moral and political philosophers – is complex and multifaceted. (See the entry on suicide .) People have many different things to live for, as well as tribulations to escape from. In dark moments it may well seem reasonable to wish for a release from suffering; other times, the attempt to end one’s own life may strike others – and oneself, if one survives – as rash and tragic. One extreme case would be martyrs, praised for giving their lives to a higher cause. At the other end might be those who, at least on some views, have a very clear duty to stay alive. Even in such cases, however, it may be inapt or counterproductive to castigate someone for actions taken out of distraught desperation, abandoned by their sense of self-worth; to defend a duty of self-care here is not simply to advocate blaming and shaming.

There are also many people to whom one might owe the duty not to kill oneself, as Kant observes:

[Suicide] can…be regarded as a violation of one’s duty to other people (the duty of spouses to each other, of parents to their children, of a subject to his superior or to his fellow citizens, and finally even a violation of duty to God, as his abandoning the post assigned him in the world without having been called away from it). ( MM 6:422)