Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 01 April 2019

Infrastructure for sustainable development

- Scott Thacker ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2683-484X 1 , 2 ,

- Daniel Adshead 2 ,

- Marianne Fay 3 ,

- Stéphane Hallegatte ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1781-4268 3 ,

- Mark Harvey 4 ,

- Hendrik Meller 5 ,

- Nicholas O’Regan 1 ,

- Julie Rozenberg 3 ,

- Graham Watkins 6 &

- Jim W. Hall 2

Nature Sustainability volume 2 , pages 324–331 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

377 Citations

114 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Civil engineering

- Developing world

- Sustainability

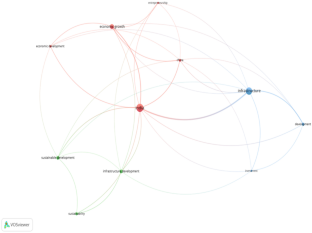

Infrastructure systems form the backbone of every society, providing essential services that include energy, water, waste management, transport and telecommunications. Infrastructure can also create harmful social and environmental impacts, increase vulnerability to natural disasters and leave an unsustainable burden of debt. Investment in infrastructure is at an all-time high globally, thus an ever-increasing number of decisions are being made now that will lock-in patterns of development for future generations. Although for the most part these investments are motivated by the desire to increase economic productivity and employment, we find that infrastructure either directly or indirectly influences the attainment of all of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including 72% of the targets. We categorize the positive and negative effects of infrastructure and the interdependencies between infrastructure sectors. To ensure that the right infrastructure is built, policymakers need to establish long-term visions for sustainable national infrastructure systems, informed by the SDGs, and develop adaptable plans that can demonstrably deliver their vision.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

The economic commitment of climate change

Maximilian Kotz, Anders Levermann & Leonie Wenz

Ghost roads and the destruction of Asia-Pacific tropical forests

Jayden E. Engert, Mason J. Campbell, … William F. Laurance

The role of artificial intelligence in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals

Ricardo Vinuesa, Hossein Azizpour, … Francesco Fuso Nerini

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information .

Carse, A. in Infrastructures and Social Complexity: A Companion (eds Harvey, P. et al.) (Routledge, 2016).

Pederson, P., Dudenhoeffer, D., Hartley, S. & Permann, M. Critical Infrastructure Interdependency Modeling: A Survey of US and International Research (Idaho National Laboratory, 2006).

A National Infrastructure for the 21st Century (Council for Science and Technology, 2009).

Frischmann, B. M. Infrastructure: The Social Value of Shared Resources (Oxford Univ. Press, 2012).

Allen, S. Points and Lines: Diagrams and Projects for the City (Princeton Architectural Press, 1999).

Erickson, P., Kartha, S., Lazarus, M. & Tempest, K. Assessing carbon lock-in. Environ. Res. Lett. 10 , 084023 (2015).

Article Google Scholar

Weinberger, R. & Goetzke, F. Unpacking preference: how previous experience affects auto ownership in the United States. Urban Stud. 47 , 2111–2128 (2010).

Clark, S. S., Seager, T. P. & Chester, M. V. A capabilities approach to the prioritization of critical infrastructure. Environ. Syst. Decis. 38 , 339–352 (2018).

Steinbuks, J. & Foster, V. When do firms generate? Evidence on in-house electricity supply in Africa. Energy Econ. 32 , 505–514 (2010).

Fischer, M. M. Innovation, Networks, and Knowledge Spillovers, Selected Essays (Springer, 2006).

Fujita, M., Krugman, P. R. & Venables A. J. The Spatial Economy: Cities, Regions, and International Trade (MIT press, 2001).

The Sustainable Infrastructure Imperative: Financing for Better Growth and Development. The 2016 New Climate Economy Report (The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, 2016).

Scholz, M. & Lee, B. H. Constructed wetlands: a review. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 62 , 421–447 (2005).

van der Kamp, G. & Hayashi, M. The groundwater recharge function of small wetlands in the semi-arid Northern Prairies. Great Plains Res. 8 , 39–56 (1998).

Google Scholar

Dadson, S. J. et al. A restatement of the natural science evidence concerning catchment-based ‘natural’ flood management in the UK. Proc. R. Soc. A 473 , 20160706 (2017).

Lewis, T. G. Critical Infrastructure Protection in Homeland Security: Defending a Networked Nation (Wiley, 2006).

Rinaldi, S. M., Peerenboom, J. P. & Kelly, T. K. Identifying, understanding, and analyzing critical infrastructure interdependencies. IEEE Contr. Syst. Mag. 21 , 11–25 (2001).

Bollinger, L. & Dijkema, G. Evaluating infrastructure resilience to extreme weather – the case of the Dutch electricity transmission network. Eur. J. Transp. Infrastruct. Res. 16 , 214–239 (2016).

Global Infrastructure Outlook: 2017 (Global Infrastructure Hub, 2017).

Bhattacharya, A. et al. Delivering on Sustainable Infrastructure for Better Development and Better Climate (Brookings Institution, 2016).

Ascensão, F. et al. Environmental challenges for the Belt and Road Initiative. Nat. Sustain. 1 , 206–209 (2018).

Private Participation in Infrastructure (PPI) Annual Report: 2017 (The World Bank, 2017).

World Bank Press Release 2015/041/EAP (The World Bank, 2014).

Better Infrastructure, Better Economy (European Investment Bank, 2017).

African Economic Outlook: 2018 (African Development Bank, 2018).

Adam, M. C. & Bevan M. D. Public Investment, Public Finance, and Growth: The Impact of Distortionary Taxation, Recurrent Costs, and Incomplete Appropriability (International Monetary Fund, 2014).

Inclusive Green Growth: The Pathway to Sustainable Development (The World Bank, 2012).

Connecting People, Creating Wealth: Infrastructure for Economic Development and Poverty Reduction (Department for International Development, 2013).

Ruan, Z., Wang, C., Ming Hui, P. & Liu, Z. Integrated travel network model for studying epidemics: interplay between journeys and epidemic. Sci. Rep. 5 , 11401 (2015).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Pfeiffer, A., Hepburn, C., Vogt-Schilb, A. & Caldecott, B. Committed emissions from existing and planned power plants and asset stranding required to meet the Paris Agreement. Environ. Res. Lett. 13 , 054019 (2018).

Gaynor, C. & Jennings, M. Gender, Poverty and Public Private Partnerships In Infrastructure, (PPPI) . Annex on Gender and Infrastructure (The World Bank, 2004).

Bajar, S. & Rajeev, M. The impact of infrastructure provisioning on inequality in India: does the level of development matter? J. Comp. Asian Dev. 15 , 122–155 (2016).

Hall, J. W., Nicholls, R. J., Tran, M. & Hickford, A. J. The Future of National Infrastructure: A System Of Systems Approach (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2016).

Fuso Nerini, F. et al. Mapping synergies and trade-offs between energy and the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Energy 3 , 10–15 (2018).

Bhaduri, A. et al. Achieving sustainable development goals from a water perspective. Front. Environ. Sci. 4 , 64 (2016).

Transport and Sustainable Development Goals Transport and Communications Bulletin for Asia and the Pacific No. 87 (United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, 2017).

Weitz, N., Carlsen, H., Nilsson, M. & Skånberg, K. Towards systemic and contextual priority setting for implementing the 2030 agenda. Sustain. Sci. 13 , 531–548 (2018).

Straub, S. Infrastructure and Development: A Critical Appraisal of the Macro Level Literature (The World Bank, 2008).

Lee, K., Miguel, E. & Wolfram, C. Appliance ownership and aspirations among electric grid and home solar households in rural Kenya. Am. Econ. Rev. 106 , 89–94 (2016).

Banister, D. & Berechman, Y. Transport investment and the promotion of economic growth. J. Transp. Geogr. 9 , 209–218 (2001).

Duranton, G. & Venables, A. J. Place-based Policies for Development World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 8410 (The World Bank, 2018).

Mathur, V. K. Human capital-based strategy for regional economic development. Econ. Dev. Q. 13 , 203–216 (1999).

Venables, A. J., Laird, J. & Overman, H. Transport Investment and Economic Performance: Implications for Project Appraisal (Department for Transport, 2014).

N ew Urban Agenda A/RES/71/256 (United Nations, 2017).

Hall, J. W. et al. Strategic analysis of the future of national infrastructure. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Civ. Eng. 170 , 39–47 (2017).

Otto, A. et al. A quantified system-of-systems modeling framework for robust national infrastructure planning. IEEE Syst. J. 10 , 385–396 (2016).

Allenby, B. & Chester, M. V. Reconceptualizing infrastructure in the Anthropocene. Issues Sci. Technol. 34 , 3 (2018).

Adshead, D. et al. Evidence-based Infrastructure: Curaçao National Infrastructure Systems Modelling to Support Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure Development (United Nations Office for Project Services, 2018).

Chester, M. V. & Allenby, B. Toward adaptive infrastructure: flexibility and agility in a non-stationarity age. Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. https://doi.org/10.1080/23789689.2017.1416846 (2018).

Siew, Y. J. R., Balatbat, M. C. A. & Carmichael, D. G. A review of building/infrastructure sustainability reporting tools (SRTs). Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2 , 106–139 (2013).

Final Report: Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, 2017).

Strategic Infrastructure Planning: International Best Practice (OECD, 2017).

How to Design an Infrastructure Strategy for the UK (Institute for Government, 2017).

The Global Competitiveness Report 2017–2018 (World Economic Forum, 2017).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the contributions of the Infrastructure Transitions Research Consortium, which is funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council by grants EP/101344X/1 and EP/N017064/1. S.T. thanks the United Nations Office for Project Services, specifically R. Jones, G. Morgan, S. Crosskey and T. Sway for providing useful suggestions that improved this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS), Copenhagen, Denmark

Scott Thacker & Nicholas O’Regan

University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Scott Thacker, Daniel Adshead & Jim W. Hall

World Bank, Washington, DC, USA

Marianne Fay, Stéphane Hallegatte & Julie Rozenberg

Department for International Development (DFID), London, UK

Mark Harvey

German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ), Bonn, Germany

Hendrik Meller

Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), Washington, DC, USA

Graham Watkins

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

S.T. designed the study. D.A., S.T. and J.W.H. performed most of the analyses. J.W.H., S.T. and D.A. wrote most of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the development of the manuscript through methodological advice, analysis, comments and edits to the text and figures.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Scott Thacker .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary Table 1 and 2

Supplementary Table 3

Additional data (qualitative)

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Thacker, S., Adshead, D., Fay, M. et al. Infrastructure for sustainable development. Nat Sustain 2 , 324–331 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0256-8

Download citation

Received : 29 August 2017

Accepted : 25 February 2019

Published : 01 April 2019

Issue Date : April 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0256-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Mainstreaming systematic climate action in energy infrastructure to support the sustainable development goals.

- Louise Wernersson

- Simon Román

- Daniel Adshead

npj Climate Action (2024)

Social consequences of planned relocation in response to sea level rise: impacts on anxiety, well-being, and perceived safety

- Stacey C Heath

Scientific Reports (2024)

Climate threats to coastal infrastructure and sustainable development outcomes

- Amelie Paszkowski

- Jim W. Hall

Nature Climate Change (2024)

Solid-state lithium-ion batteries for grid energy storage: opportunities and challenges

- Yu-Ming Zhao

Science China Chemistry (2024)

The role of the waste sector in the sustainable development goals and the IPCC assessment reports

- Romana Kopecká

- Marlies Hrad

- Marion Huber-Humer

Österreichische Wasser- und Abfallwirtschaft (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Why Infrastructure Matters: Rotten Roads, Bum Economy

Subscribe to the brookings metro update, robert puentes robert puentes nonresident senior fellow - brookings metro @rpuentes.

January 20, 2015

- 12 min read

Cities, states and metropolitan areas throughout America face an unprecedented economic, demographic, fiscal and environmental challenges that make it imperative for the public and private sectors to rethink the way they do business. These new forces are incredibly diverse, but they share an underlying need for modern, efficient and reliable infrastructure.

Concrete, steel and fiber-optic cable are the essential building blocks of the economy. Infrastructure enables trade, powers businesses, connects workers to their jobs, creates opportunities for struggling communities and protects the nation from an increasingly unpredictable natural environment. From private investment in telecommunication systems, broadband networks, freight railroads, energy projects and pipelines, to publicly spending on transportation, water, buildings and parks, infrastructure is the backbone of a healthy economy.

It also supports workers, providing millions of jobs each year in building and maintenance. A Brookings Institution analysis Bureau of Labor Statistics data reveals that 14 million people have jobs in fields directly related to infrastructure. From locomotive engineers and electrical power line installers, to truck drivers and airline pilots, to construction laborers and meter readers, infrastructure jobs account for nearly 11 percent of the nation’s workforce, offering employment opportunities that have low barriers of entry and are projected to grow over the next decade.

Important national goals also depend on it. The economy needs reliable infrastructure to connect supply chains and efficiently move goods and services across borders. Infrastructure connects households across metropolitan areas to higher quality opportunities for employment, healthcare and education. Clean energy and public transit can reduce greenhouse gases. This same economic logic applies to broadband networks, water systems and energy production and distribution.

Big demographic and cultural changes, such as the aging and diversification of our society, shrinking households and domestic migration, underscore the need for new transportation and telecommunications to connect people and communities. The percentage of licensed drivers among the young is the lowest in three decades, as more of them use public transit and many others use new services for sharing cars and bikes. The prototypical family of the suburban era, a married couple with school-age children, now represents only 20 percent of households, down from over 40 percent in 1970. Some 55 percent of millennials say living close to public transportation is important to them, according to a recent survey by the Urban Land Institute.

Yet unlike Western Europe and parts of Asia, the United States still has a growing population. We’ve added 25 million people in the past 10 years. This tremendous growth, concentrated in the 50 largest metropolitan areas, will place new demands on already overtaxed infrastructure. Metropolitan areas must be ready to adapt not only to serve millions of new customers but also to help poorer residents, many of whom are jobless, have the best chance possible to find work.

A recent Brookings analysis found that only a quarter of jobs in low-skill and middle-skill industries can be reached within 90 minutes by a typical metropolitan commuter. Successful cities will be those that connect workers to jobs and close the digital divide between high-income and low-income neighborhoods. The White House notes that broadband speeds have doubled since 2009 and that more than four out of five people now have high-speed wireless broadband, adoption rates for low-income and minority households remains low (about 43 and 56 percent, respectively.)

Our economy is changing as fast as our society. Over 83 percent of world economic growth in the next five years is expected to occur outside the United States, and because of rapid globalization, it will be concentrated in cities. This offers an unprecedented opportunity for American businesses to export more goods and services and to create high-quality jobs at home. It also amplifies the importance of our seaports, air hubs, freight rail, border crossings and truck routes, which move $51 billion worth of goods quickly and efficiently each day in the complex supply chains of the modern economy.

The diverse energy boom also disrupts our infrastructure. Natural gas needs new truck, pipeline and rail networks. Rooftop solar panels have rattled electric utilities, which are scrambling to find ways to incorporate and store the energy they produce while keeping the grid operating. At the same time, finding the money to pay for the development of a smart electricity grid and for clean energy presents challenges, as hundreds of thousands of small and large projects are projected to come online in coming decades.

High-profile natural disasters, such as Hurricane Sandy, drew attention to problems with water infrastructure. Overwhelmed waste water systems, washed-out roads, shorted electrical circuitry and flooded train stations not only highlighted the economy’s reliance on these networks, but also revealed their poor condition. The nation’s water systems are now being rebuilt. Cities are working to capture storm and rain water rather than building costly pipes to sluice it away. The Center for an Urban Future recently described how New York City plans to spend $2.4 billion over 18 years in so-called “green” infrastructure such as rooftop vegetation, porous pavements, and soils to soak up rain.

Over and above the new types of needed infrastructure is a big change in how projects are financed.

Despite the importance of infrastructure, the U.S. has not spent enough for decades to maintain and improve it. It accounts for about 2.5 percent of the economy, compared to about 3.9 percent spent in Canada, Australia and South Korea, 5 percent for Europe and 9-12 percent in China. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates that the U.S. must spend at least $150 billion more a year on infrastructure through 2020 to meet its needs. This would add about 1.5 percent to annual economic growth and create at least 1.8 million jobs.

Split between Republicans and Democrats, the federal government appears incapable of doing this. For the foreseeable future, the Highway Trust Fund, the State Revolving Funds for water and others will face cuts and squeezed budgets. Other experiments, such as a National Infrastructure Bank, seem prohibitively complex in the current political environment. And of course, rising interest costs on federal debt, increases in entitlement spending and declining traditional revenue sources such as the gasoline tax mean that competition for limited resources is fiercer than ever.

Some cities and states are enjoying budget surpluses because property and sales tax revenues. But most localities will take years to build back their reserves, repay additional debt incurred during the recession and pay for deferred maintenance on infrastructure. Unfunded pension obligations and other debts facing all levels of government mean there just aren’t the public funds to pay for necessary infrastructure. And though interest rates remain at historically low levels, the ability of many governments to borrow from capital markets is hindered by debt caps and weak credit ratings.

Despite gradual acceptance in the past decade that infrastructure is vital to economic growth, debate of spending remains an amorphous and simplistic. Infrastructure is made up of interrelated sectors as diverse as a water treatment plant is from an airport, a wind farm, a gas line or a broadband network. The focus on infrastructure in the abstract led to unrealistic silver-bullet policy solutions that fail to capture the unique and economically critical attributes of each. In reality, each infrastructure sector involves fundamentally different design frameworks and market attributes. And they are owned, regulated, governed and operated by different public and private entities.

The federal role should not be exaggerated. American infrastructure in selected, built, maintained, operates and paid for in a diverse and fragmentary fashion. For certain sectors, such as transportation and water, federal spending is relatively high, averaging $92.15 billion each year from 2000 to 2007. But even there, according to the Congressional Budget Office, Washington’s share of spending never topped 27 percent. For other sectors, such as freight rail, telecommunications, and clean energy, the federal role is more limited.

So what does all this mean and how are we going to pay for what we need?

Roads, bridges and transit must be paid for largely from public funds. Ballot measures have been important for fund raising, particularly at the local level, because general obligation bonds require popular approval. That’s how regions and municipalities pay for public transit systems, bridges, road construction, water and sewer improvements and a host of other infrastructure projects. Many cities are following this trend. Those places, especially in Westerns cities such as Los Angeles, Phoenix and Salt Lake City, are taxing themselves, dedicating substantial local money and effectively contributing to the construction of the nation’s infrastructure.

Metropolitan transportation initiatives are popular among voters. According to the Center for Transportation Excellence, 71 percent of measures were passed in 2014 as were 73 percent in 2013. While state level ballot measures on infrastructure spending are far less common, in 2013, eight states voted to raise taxes for such projects. This includes both conservative strongholds such as Wyoming and Democrat-controlled legislatures in states such as Maryland.

A number of cities are using market mechanisms that capture the increased value in land that accrues from infrastructure. This provides a more targeted way to finance new or existing transportation projects by matching the benefit from infrastructure with its cost. These techniques include impact fees where land developers are assessed a charge to support associated public infrastructure improvements, generally local roads and public works like sidewalks. The lease or sale of air rights is another practice that has been used by to finance development around transit stations for decades, famously around Grand Central Station in New York, and more recently in Boston and Dallas.

Another growing trend is the use of tax increment financing districts. These TIFs support infrastructure projects by borrowing against the future stream of additional tax revenue the project is expected to generate. Examples include a TIF used to pay for improvements at the Atlantic Station project in Atlanta and Portland, Ore.,’s similar strategy to fund its streetcar by creating a local improvement district that leveraged the economic gains of nearby property owners.

For its part, the federal government can allow greater flexibility for states and cities to innovate on projects that connect metros. Passenger Facility Charges used to fund airport modernization are artificially capped at $4.50 and do not begin to cover the airport’s operating and long-term investment costs. Busy airports could be freed to meet congestion and investment costs by removing the caps. Archaic restrictions on interstate highways tolls could also be lifted. Metropolitan and local leaders, with the states, are in the best position to determine which segments of road could best raise revenue.

Other infrastructures could be public-private partnerships. These often complex agreements allow the public sector to bring in private enterprises to take an active role during the life of the infrastructure asset. At their heart, these partnerships share risk and costs of design, construction, maintenance, financing and operations.

The public-sector interest in partnerships is propelled by the shortage of money. Ever since the recession, many states and local governments have been plagued by high debt, low credit ratings and limited options to borrow. PPPs are not “free money,” but they can offer benefits such as better and faster completion of the project, more budgetary accountability and overall savings.

Partnerships with the private sector are not appropriate for all infrastructure sectors or projects. Some may not be profitable enough to attract investors. Green infrastructure or public parks, for example, may lack a revenue stream. Private conservancies maintain and oversee parks in New York, Pittsburgh, Houston and St. Louis, but they are all nonprofit organizations set up solely for that purpose and do not help spread risk.

The best infrastructure projects for private sector involvement are those with a clear revenue stream from rate-payers, such as water infrastructure and toll roads. The private sector can bring in new technologies for metering and billing that can improve services. Thoughtful procurement can also facilitate projects that do not include ratepayers. Nearly any project can be suitable for a private partnership as long as there is a mechanism to spread risk among all parties, even without user fees. So-called availability payment models allow the public sector to pay a recurring user fee for the use of an asset based on its condition and accessibility. These payments are a form of debt since but require continuous public expenditure and a binding budgetary obligation.

It would help spur public-private partnerships if there were standard contracts and pricing, risk sharing and returns. In the past, Washington has set these kinds of standards for such vast areas of the consumer market as housing and small business. But the federal government appears unlikely to do so for infrastructure investment. A mix of public, private and civic bodies will have to do so instead.

An emerging example is the West Coast Infrastructure Exchange, a collaboration between California, Oregon, Washington and British Columbia standardizing transparency, contracts, labor and risk allocation. The goal is to build a market for projects. By sharing details, project finance and delivery methods can be scaled and replicated.

If successful, the WCX could be a model for other state, city and metro infrastructure exchanges. Each exchange could focus on the infrastructure delivery and finance strategies suited to the culture, traditions and needs of the region it serves. An East Coast or Mid-Atlantic Exchange could focus on rebuilding coastlines and climate resiliency after Hurricane Sandy, or on transportation projects that cross state borders. A Midwestern Exchange might focus on water infrastructure in a largely slow growth environment or on projects with Canada. A Southern Exchange might facilitate new infrastructure to accommodate fast growth and new manufacturing, supply chains and movement of goods. Regardless of their focus, exchanges could be linked through a project clearinghouse to share data, information and best practices.

Energy, telecommunications and freight rail will remain dominated by the private sector typically with federal and state regulatory oversight. But there will also be new types of public and private relationships in these sectors, too. For example, while broadband networks are still delivered by private companies, local governments recognize that this kind of network access is equally important to the future economic success of households as well as businesses. So as cities such as Los Angeles explore ways to extend broadband to all homes, they also are working to figure out the financing arrangements and business opportunities for firms interested in developing those networks.

The trade and logistics industry is highly decentralized, with private operators owning almost all trucks and rails, and the public sector owning roads, airports, and waterway rights. Unlike such countries as Germany, Canada and Australia, the U.S. does not have a unified strategy that aligns disparate owners and interests around national economic objectives. Innovative partnerships are therefore necessary to make freight movements in and around big cities more efficient and reliable. The CREATE program in Chicago aligns several such interests in a citywide effort to relieve freight and passenger bottlenecks that cause delays. The $2.5 billion for the program will come from a mix of traditional sources (federal grants), private investments (railroads), state loans (bonds) and existing local sources.

It is clear that projects are becoming more complex. There is not one-size-fits-all form of financing for them. It very much depends on the place, time and particulars of each project. The level of private engagement will depend on market and business opportunities.

In many respects, America’s ability to realize its competitive potential depends on making smart infrastructure choices. These must respond to economic, demographic, fiscal, and environmental changes if they are to help people, places and firms thrive and prosper.

This commentary was originally published by the Washington Examiner .

Infrastructure

Brookings Metro

The Brookings Institution, Washington DC

2:30 pm - 4:00 pm EDT

William H. Frey

April 15, 2024

Molly Kinder

April 12, 2024

Infrastructure Development: The Cornerstone of Economic Growth | Essay Writing for UPSC by Vikash Ranjan Sir | Triumph ias

Table of Contents

Infrastructure Development: The Pillar of Economic Growth

(relevant for essay writing for upsc civil services examination).

Infrastructure development is often considered the backbone of economic growth. But how exactly does it contribute to a nation’s prosperity? Let’s delve into the integral relationship between infrastructure and economic development.

Jobs, Productivity, and Investment

From constructing roads to laying down telecom lines, infrastructure projects create jobs and boost productivity. These projects also attract investment, becoming a magnet for business growth.

Beyond Economics: Social Progress

Infrastructure is not just about economics; it’s about social progress. By improving access to services and reducing inequality, infrastructure fosters a more inclusive society.

Building a Sustainable Future

In the era of climate change, sustainable infrastructure is essential. By considering environmental impacts and building resilience, infrastructure sets the stage for long-term economic stability.

Conclusion: The Way Forward

Infrastructure development is economic development. By weaving together growth, inclusivity, and sustainability, it crafts the blueprint for a nation’s progress.

To master these intricacies and fare well in the Sociology Optional Syllabus , aspiring sociologists might benefit from guidance by the Best Sociology Optional Teacher and participation in the Best Sociology Optional Coaching . These avenues provide comprehensive assistance, ensuring a solid understanding of sociology’s diverse methodologies and techniques

Infrastructure Development, Economic Growth, Job Creation, Productivity, Investment, Accessibility, Inequality Reduction, Sustainability, Resilience, Economic Development.

Sociology Optional Syllabus Course Commencement Information

- Enrolment is limited to a maximum of 250 Seats.

- Course Timings: Evening Batch

- Course Duration: 4.5 Months

- Class Schedule: Monday to Saturday

- Batch Starts from: Admission open for online batch

Book Your Seat Fast Book Your Seat Fast

We would like to hear from you. Please send us a message by filling out the form below and we will get back with you shortly.

Instructional Format:

- Each class session is scheduled for a duration of two hours.

- At the conclusion of each lecture, an assignment will be distributed by Vikash Ranjan Sir for Paper-I & Paper-II coverage.

Study Material:

- A set of printed booklets will be provided for each topic. These materials are succinct, thoroughly updated, and tailored for examination preparation.

- A compilation of previous years’ question papers (spanning the last 27 years) will be supplied for answer writing practice.

- Access to PDF versions of toppers’ answer booklets will be available on our website.

- Post-course, you will receive two practice workbooks containing a total of 10 sets of mock test papers based on the UPSC format for self-assessment.

Additional Provisions:

- In the event of missed classes, video lectures will be temporarily available on the online portal for reference.

- Daily one-on-one doubt resolution sessions with Vikash Ranjan Sir will be organized post-class.

Syllabus of Sociology Optional

FUNDAMENTALS OF SOCIOLOGY

- Modernity and social changes in Europe and emergence of sociology.

- Scope of the subject and comparison with other social sciences.

- Sociology and common sense.

- Science, scientific method and critique.

- Major theoretical strands of research methodology.

- Positivism and its critique.

- Fact value and objectivity.

- Non- positivist methodologies.

- Qualitative and quantitative methods.

- Techniques of data collection.

- Variables, sampling, hypothesis, reliability and validity.

- Karl Marx- Historical materialism, mode of production, alienation, class struggle.

- Emile Durkheim- Division of labour, social fact, suicide, religion and society.

- Max Weber- Social action, ideal types, authority, bureaucracy, protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism.

- Talcott Parsons- Social system, pattern variables.

- Robert K. Merton- Latent and manifest functions, conformity and deviance, reference groups.

- Mead – Self and identity.

- Concepts- equality, inequality, hierarchy, exclusion, poverty and deprivation.

- Theories of social stratification- Structural functionalist theory, Marxist theory, Weberian theory.

- Dimensions – Social stratification of class, status groups, gender, ethnicity and race.

- Social mobility- open and closed systems, types of mobility, sources and causes of mobility.

- Social organization of work in different types of society- slave society, feudal society, industrial /capitalist society

- Formal and informal organization of work.

- Labour and society.

- Sociological theories of power.

- Power elite, bureaucracy, pressure groups, and political parties.

- Nation, state, citizenship, democracy, civil society, ideology.

- Protest, agitation, social movements, collective action, revolution.

- Sociological theories of religion.

- Types of religious practices: animism, monism, pluralism, sects, cults.

- Religion in modern society: religion and science, secularization, religious revivalism, fundamentalism.

- Family, household, marriage.

- Types and forms of family.

- Lineage and descent.

- Patriarchy and sexual division of labour.

- Contemporary trends.

- Sociological theories of social change.

- Development and dependency.

- Agents of social change.

- Education and social change.

- Science, technology and social change.

INDIAN SOCIETY: STRUCTURE AND CHANGE

Introducing indian society.

- Indology (GS. Ghurye).

- Structural functionalism (M N Srinivas).

- Marxist sociology (A R Desai).

- Social background of Indian nationalism.

- Modernization of Indian tradition.

- Protests and movements during the colonial period.

- Social reforms.

SOCIAL STRUCTURE

- The idea of Indian village and village studies.

- Agrarian social structure – evolution of land tenure system, land reforms.

- Perspectives on the study of caste systems: GS Ghurye, M N Srinivas, Louis Dumont, Andre Beteille.

- Features of caste system.

- Untouchability – forms and perspectives.

- Definitional problems.

- Geographical spread.

- Colonial policies and tribes.

- Issues of integration and autonomy.

- Social Classes in India:

- Agrarian class structure.

- Industrial class structure.

- Middle classes in India.

- Lineage and descent in India.

- Types of kinship systems.

- Family and marriage in India.

- Household dimensions of the family.

- Patriarchy, entitlements and sexual division of labour

- Religious communities in India.

- Problems of religious minorities.

SOCIAL CHANGES IN INDIA

- Idea of development planning and mixed economy

- Constitution, law and social change.

- Programmes of rural development, Community Development Programme, cooperatives,poverty alleviation schemes

- Green revolution and social change.

- Changing modes of production in Indian agriculture.

- Problems of rural labour, bondage, migration.

3. Industrialization and Urbanisation in India:

- Evolution of modern industry in India.

- Growth of urban settlements in India.

- Working class: structure, growth, class mobilization.

- Informal sector, child labour

- Slums and deprivation in urban areas.

4. Politics and Society:

- Nation, democracy and citizenship.

- Political parties, pressure groups , social and political elite

- Regionalism and decentralization of power.

- Secularization

5. Social Movements in Modern India:

- Peasants and farmers movements.

- Women’s movement.

- Backward classes & Dalit movement.

- Environmental movements.

- Ethnicity and Identity movements.

6. Population Dynamics:

- Population size, growth, composition and distribution

- Components of population growth: birth, death, migration.

- Population policy and family planning.

- Emerging issues: ageing, sex ratios, child and infant mortality, reproductive health.

7. Challenges of Social Transformation:

- Crisis of development: displacement, environmental problems and sustainability

- Poverty, deprivation and inequalities.

- Violence against women.

- Caste conflicts.

- Ethnic conflicts, communalism, religious revivalism.

- Illiteracy and disparities in education.

Mr. Vikash Ranjan, arguably the Best Sociology Optional Teacher , has emerged as a versatile genius in teaching and writing books on Sociology & General Studies. His approach to the Sociology Optional Syllabus / Sociology Syllabus is remarkable, and his Sociological Themes and Perspectives are excellent. His teaching aptitude is Simple, Easy and Exam Focused. He is often chosen as the Best Sociology Teacher for Sociology Optional UPSC aspirants.

About Triumph IAS

Innovating Knowledge, Inspiring Success We, at Triumph IAS , pride ourselves on being the best sociology optional coaching platform. We believe that each Individual Aspirant is unique and requires Individual Guidance and Care, hence the need for the Best Sociology Teacher . We prepare students keeping in mind his or her strength and weakness, paying particular attention to the Sociology Optional Syllabus / Sociology Syllabus , which forms a significant part of our Sociology Foundation Course .

Course Features

Every day, the Best Sociology Optional Teacher spends 2 hours with the students, covering each aspect of the Sociology Optional Syllabus / Sociology Syllabus and the Sociology Course . Students are given assignments related to the Topic based on Previous Year Question to ensure they’re ready for the Sociology Optional UPSC examination.

Regular one-on-one interaction & individual counseling for stress management and refinement of strategy for Exam by Vikash Ranjan Sir , the Best Sociology Teacher , is part of the package. We specialize in sociology optional coaching and are hence fully equipped to guide you to your dream space in the civil service final list.

Specialist Guidance of Vikash Ranjan Sir

The Best Sociology Teacher helps students to get a complete conceptual understanding of each and every topic of the Sociology Optional Syllabus / Sociology Syllabus , enabling them to attempt any of the questions, be direct or applied, ensuring 300+ Marks in Sociology Optional .

Classrooms Interaction & Participatory Discussion

The Best Sociology Teacher, Vikash Sir , ensures that there’s explanation & DISCUSSION on every topic of the Sociology Optional Syllabus / Sociology Syllabus in the class. The emphasis is not just on teaching but also on understanding, which is why we are known as the Best Sociology Optional Coaching institution.

Preparatory-Study Support

Online Support System (Oss)

Get access to an online forum for value addition study material, journals, and articles relevant to Sociology on www.triumphias.com . Ask preparation related queries directly to the Best Sociology Teacher , Vikash Sir, via mail or WhatsApp.

Strategic Classroom Preparation

Comprehensive Study Material

We provide printed booklets of concise, well-researched, exam-ready study material for every unit of the Sociology Optional Syllabus / Sociology Syllabus , making us the Best Sociology Optional Coaching platform.

Why Vikash Ranjan’s Classes for Sociology?

Proper guidance and assistance are required to learn the skill of interlinking current happenings with the conventional topics. VIKASH RANJAN SIR at TRIUMPH IAS guides students according to the Recent Trends of UPSC, making him the Best Sociology Teacher for Sociology Optional UPSC.

At Triumph IAS, the Best Sociology Optional Coaching platform, we not only provide the best study material and applied classes for Sociology for IAS but also conduct regular assignments and class tests to assess candidates’ writing skills and understanding of the subject.

Choose T he Best Sociology Optional Teacher for IAS Preparation?

At the beginning of the journey for Civil Services Examination preparation, many students face a pivotal decision – selecting their optional subject. Questions such as “ which optional subject is the best? ” and “ which optional subject is the most scoring? ” frequently come to mind. Choosing the right optional subject, like choosing the best sociology optional teacher , is a subjective yet vital step that requires a thoughtful decision based on facts. A misstep in this crucial decision can indeed prove disastrous.

Ever since the exam pattern was revamped in 2013, the UPSC has eliminated the need for a second optional subject. Now, candidates have to choose only one optional subject for the UPSC Mains , which has two papers of 250 marks each. One of the compelling choices for many has been the sociology optional. However, it’s strongly advised to decide on your optional subject for mains well ahead of time to get sufficient time to complete the syllabus. After all, most students score similarly in General Studies Papers; it’s the score in the optional subject & essay that contributes significantly to the final selection.

“ A sound strategy does not rely solely on the popular Opinion of toppers or famous YouTubers cum teachers. ”

It requires understanding one’s ability, interest, and the relevance of the subject, not just for the exam but also for life in general. Hence, when selecting the best sociology teacher, one must consider the usefulness of sociology optional coaching in General Studies, Essay, and Personality Test.

The choice of the optional subject should be based on objective criteria, such as the nature, scope, and size of the syllabus, uniformity and stability in the question pattern, relevance of the syllabic content in daily life in society, and the availability of study material and guidance. For example, choosing the best sociology optional coaching can ensure access to top-quality study materials and experienced teachers. Always remember, the approach of the UPSC optional subject differs from your academic studies of subjects. Therefore, before settling for sociology optional , you need to analyze the syllabus, previous years’ pattern, subject requirements (be it ideal, visionary, numerical, conceptual theoretical), and your comfort level with the subject.

This decision marks a critical point in your UPSC – CSE journey , potentially determining your success in a career in IAS/Civil Services. Therefore, it’s crucial to choose wisely, whether it’s the optional subject or the best sociology optional teacher . Always base your decision on accurate facts, and never let your emotional biases guide your choices. After all, the search for the best sociology optional coaching is about finding the perfect fit for your unique academic needs and aspirations.

To master these intricacies and fare well in the Sociology Optional Syllabus , aspiring sociologists might benefit from guidance by the Best Sociology Optional Teacher and participation in the Best Sociology Optional Coaching . These avenues provide comprehensive assistance, ensuring a solid understanding of sociology’s diverse methodologies and techniques. Sociology, Social theory, Best Sociology Optional Teacher, Best Sociology Optional Coaching, Sociology Optional Syllabus. Best Sociology Optional Teacher, Sociology Syllabus, Sociology Optional, Sociology Optional Coaching, Best Sociology Optional Coaching, Best Sociology Teacher, Sociology Course, Sociology Teacher, Sociology Foundation, Sociology Foundation Course, Sociology Optional UPSC, Sociology for IAS,

Follow us :

🔎 https://www.instagram.com/triumphias

🔎 www.triumphias.com

🔎https://www.youtube.com/c/TriumphIAS

https://t.me/VikashRanjanSociology

Find More Blogs

One comment.

- Pingback: Rajat Yadav | Infrastructure investment, in science is an investment in jobs, in health, in economic growth, and developmental solutions | Copy UPSC CSE 2022 RANK 111

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Infrastructure development in India: a systematic review

- Original Paper

- Published: 14 October 2023

- Volume 16 , article number 35 , ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- A. Indira ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1189-5922 1 &

- N. Chandrasekaran ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0076-2019 2

321 Accesses

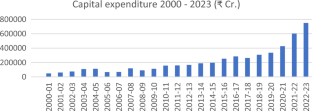

Explore all metrics

It is now well-accepted that infrastructure development is essential for the growth of any economy. Successive governments in India, both at the Union and State level have given a thrust towards increased budgetary spending on infrastructure to help economic growth. On the eve of the 75th year of independence, there is a reiteration for long-term initiatives, including focused programs for roads, railways, airports, waterways, mass transport, ports, and logistics to further boost infrastructure spending. Keeping this in mind, the authors sought to systematically review the literature on how infrastructure development has unfolded in India between the years 2000–2022. The study shows that with diverse economic growth in India, there is interest in infrastructure development aligned with public interests. Infrastructure development is contextual and location-specific. Access to infrastructure positively impacts social and economic outcomes. There is however growing concern for sustainable development with rapid urbanization.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Source Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy, 2021–22, Table 93

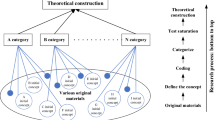

Source Author

Similar content being viewed by others

Road Development Risks and Challenges in the Philippines

Influencing factors of urban innovation and development: a grounded theory analysis

Jing-Xiao Zhang, Jia-Wei Cheng, … Ge Wang

Gentrification, Neighborhood Change, and Population Health: a Systematic Review

Alina S. Schnake-Mahl, Jaquelyn L. Jahn, … Mariana Arcaya

Agarchand, N., Laishram, B.: Sustainable infrastructure development challenges through PPP procurement process: Indian perspective. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 10 (3), 642–662 (2017)

Google Scholar

Aschauer, D.A.: Is public expenditure productive? J. Monet. Econ. 23 (2), 177–200 (1989)

Asher, S., Garg, T., Novosad, P.: The ecological impact of transportation infrastructure. Econ. J. 130 (629), 1173–1199 (2020)

Azam, M.: The role of migrant workers remittances in fostering economic growth: the four Asian developing countries’ experiences. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 42 (8), 690–775 (2015)

Barman, H., Nath, H.K.: What determines international tourist arrivals in India? Asia Pac. J. Tourism Res. 24 (2), 180–190 (2019)

Bhattacharyay, B.N., De, P.: Promotion of the trade and investment between people’s Republic of China and India: toward a regional perspective. Asian Dev. Rev. 22 (1), 45–70 (2005)

Chakravorty, U., Pelli, M., Ural Marchand, B.: Does the quality of electricity matter? Evidence from rural India. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 107 , 228–247 (2014)

Chatterjee, E.: The politics of electricity reform: evidence from West Bengal, India. World Dev. 104 , 128–139 (2018)

Chaudhuri, S., Roy, M.: Rural-urban spatial inequality in water and sanitation facilities in India: a cross-sectional study from household to national level. Appl. Geogr. 85 , 27–38 (2017)

Dasha, R.K., Sahoo, P.: Economic growth in India: the role of physical and social infrastructure. J. Econ. Policy Reform 13 (4), 373–385 (2010)

Datta, S.: The impact of improved highways on indian firms. J. Dev. Econ. 99 (1), 46–57 (2012)

Deichmann, U., Lall, S.V., et al.: Industrial location in developing countries. World Bank. Res. Obs. 23 (2), 219–246 (2008)

Desai, S., Joshi, O.: The Paradox of declining female work participation in an era of economic growth. Indian J. Lab. Econ. 62 (1), 55–71 (2019)

Dutta, A., Bouri, E., et al.: Commodity market risks and green investments: evidence from India. J. Clean. Prod. 318 , 128523 (2021)

Economic, Survey: 2000-01, Ministry of finance, Government of India, Chap. 9, (2023). https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budget_archive/es2000-01/chap91.pdf ,. Accessed on June 15,

Economic, S.: 2022-23, Ministry of finance, Government of India, (2023). https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey/doc/eschapter/echap12.pdf ,. Accessed on June 15

Fan, S., Hazell, P., Haque, T.: Targeting public investments by agro-ecological zone to achieve growth and poverty alleviation goals in rural India. Food Policy 25 (4), 411–428 (2000)

Gardas, B.B., Raut, R.D., Narkhede, B.: Evaluating critical causal factors for post-harvest losses (PHL) in the fruit and vegetables supply chain in India using the DEMATEL approach. J. Clean Prod. 199 , 47–61 (2018)

Ghosh, B., De, P.: Investigating the linkage between infrastructure and regional development in India: era of planning to globalization. J. Asian Econ. 15 (6), 1023–1050 (2005)

Hirschman, A.O.: The Strategy of Economic Development. Yale University Press, New Haven (1958)

Hulten, C.R., Bennathan, E., Srinivasan, S.: Infrastructure, externalities, and economic development: a study of the Indian manufacturing industry. World Bank. Econ. Rev. 20 (2), 291–308 (2006)

Hutchison, N., Squires, G.: Financing infrastructure development: time to unshackle the bonds? J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 34 (3), 208–224 (2016)

Jain, M.: Contemporary urbanization as unregulated growth in India: the story of census towns. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 107 , 228–247 (2018)

Kaul, H., Gupta, S.: Sustainable tourism in India. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 1 (1), 12–18 (2009)

Kennedy, L.: Regional industrial policies driving peri-urban dynamics in Hyderabad, India. Cities 24 (2), 95–109 (2007)

Krishnamurthy, R., Desouza, K.C.: Chennai, India. Cities 42 , 118–129 (2015)

Kumar, H., Singh, M.K., et al.: Moving towards smart cities: solutions that lead to the smart city transformation framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 153 , 119281 (2020)

Lei, L., Desai, S., Vanneman, R.: The impact of transportation infrastructure on women’s employment in India. Fem. Econ. 25 (4), 94–125 (2019)

Mahalingam, A.: PPP experiences in Indian cities: barriers, enablers, and the way forward. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 136 (4), 419–429 (2010)

Maparu, T.S., Mazumder, T.N.: Transport infrastructure, economic development and urbanization in India (1990–2011): is there any causal relationship? Transp. Res. Part A: Policy Pract. 100 , 319–336 (2017)

Mitra, A., Nagar, J.P.: City size, deprivation and other indicators of development: evidence from India. World Dev. 106 , 273–283 (2018)

Moench, M.: Responding to climate and other change processes in complex contexts: challenges facing development of adaptive policy frameworks in the Ganga Basin. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 77 (6), 975–986 (2010)

Nakamura, H., Nagasawa, K., et al.: Principles of infrastructure-case studies and best practices. Asian Development Bank Institute and Mitsubishi Research Institute Inc, Tokyo, pp 52–96 (2019)

Orgill-Meyer, J., Pattanayak, S.K.: Improved sanitation increases long-term cognitive test scores. World Dev. 132 , 104975 (2020)

Pal, S.: Public infrastructure, location of private schools and primary school attainment in an emerging economy. Econ. Educ. Rev. 29 (5), 783–794 (2010)

Parikh, P., Fu, K., et al.: Infrastructure provision, gender, and poverty in Indian slums. World Dev. 66 , 468–486 (2015)

Parwez, S.: A conceptual model for integration of indian food supply chains. Global Bus. Rev. 17 (4), 834–850 (2016)

Patel, U.R., Bhattacharya, S.: Infrastructure in India: The economics of transition from public to private provision. J. Comp. Econ. 38 (1), 52–70 (2010)

Pesaran, M., Hashem; Shin, Y., Smith, R.J.: Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J. Appl. Econ. 16 , 289–326 (2001)

Pradhan, R.P., Arvin, M.B., et al.: Sustainable economic development in India: The dynamics between financial inclusion, ICT development, and economic growth. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 69 , 120758 (2021)

Rasul, G., Sharma, E.: Understanding the poor economic performance of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, India: A macro-perspective. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 1 (1), 221–239 (2014)

Rud, J.P.: Electricity provision and industrial development: Evidence from India. J. Dev. Econ. 97 (2), 352–367 (2012)

Sahoo, P., Dash, R.K.: India’s surge in modern services exports: Empirics for policy. J. Policy Model 36 (6), 1082–1100 (2014)

Sati, V.P.: Carrying capacity analysis and destination development: A case study of Gangotri tourists/pilgrims’ circuit in the Himalaya. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 23 (3), 312–322 (2018)

Sharma, M., Joshi, S., et al.: Internet of things (IoT) adoption barriers of smart cities’ waste management: An indian context. J. Clean Prod. 270 , 122047 (2020)

Shenoy, A.: Regional development through place-based policies: Evidence from a spatial discontinuity. J. Dev. Econ. 130 , 173–189 (2018)

Sohail, M., Miles, D.W.J., Cotton, A.P.: Developing monitoring indicators for urban micro contracts in South Asia. Int. J. Project Manag. 20 (8), 583–591 (2002)

Sudhira, H.S., Ramachandra, T.V., Subrahmanya, M.H.B.: Bangalore. Cities 24 (5), 379–390 (2007)

Sun, Y., Ajaz, T., Razzaq, A.: How infrastructure development and technical efficiency change caused resources consumption in BRICS countries: Analysis based on energy, transport, ICT, and financial infrastructure indices. Resour. Policy 79 , 102942 (2022)

Thomas, A.V., Kalidindi, S.N., Ananthanarayanan, K.: Risk perception analysis of BOT road project participants in India. Constr. Manag. Econ. 21 (4), 393–407 (2003)

Thomson, E., Horii, N.: China’s energy security: Challenges and priorities. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 50 (6), 643–664 (2009)

Vidyarthi, H.: Energy consumption and growth in South Asia: Evidence from a panel error correction model. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 9 (3), 295–310 (2015)

Yadav, V., Karmakar, S., et al.: A feasibility study for the locations of waste transfer stations in urban centers: A case study on the city of Nashik, India. J. Clean Prod. 126 , 191–205 (2016)

Zhang, X., Fan, S.: How productive is infrastructure? A new approach and evidence from rural India. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 86 (2), 492–501 (2004)

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Budget and Policy Studies, M.N.Krishna Rao Road, Basavanagudi, Bengaluru, India

Operations Management, IFMR GSB - Krea University, Sri City, A.P., India

N. Chandrasekaran

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to A. Indira .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Indira, A., Chandrasekaran, N. Infrastructure development in India: a systematic review. Lett Spat Resour Sci 16 , 35 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12076-023-00357-5

Download citation

Received : 19 June 2023

Revised : 19 June 2023

Accepted : 20 September 2023

Published : 14 October 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12076-023-00357-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Infrastructure spending

- Infrastructure development

- Economic growth

JEL classification

Advertisement

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Essays on public infrastructure investment and economic growth

- Original file (PDF) 46.2 MB

- Cover image (JPG) 15.6 KB

- Full text (TXT) 143 B

- MODS (XML) 11.5 KB

- Dublin Core (XML) 5.4 KB

- NDLTD (XML) 6.5 KB

- Report accessibility issue

The critical role of infrastructure for the Sustainable Development Goals

The critical role of infrastructure for the Sustainable Development Goals is an essay written by The Economist Intelligence Unit and supported by UNOPS, the UN organisation with a core mandate for infrastructure. The research uses three pillars—the economy, the environment and wider society—as well as the overarching theme of resilience through which to assess the role of infrastructure in meeting global social and environmental goals.

- Marianne Fay, chief economist for climate change, World Bank

- Jim Hall, director and professor of climate and environmental risks, Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford

- Mark Harvey, head of profession (infrastructure), UK Department for International Development

- Morgan Landy, senior director of global infrastructure and natural resources, International Finance Corporation

- Virginie Marchal, senior policy analyst, Environment Directorate, OECD

- Jo da Silva, founder and director, International Development, Arup

- Graham Watkins, principal environmental specialist, Inter-American Development Bank

Introduction

From the water we drink to the way we travel to work or school, infrastructure touches every aspect of human life. It has the power to shape the natural environment—for good or for ill. As the world’s population expands, urbanisation accelerates and emerging middle classes in developing countries demand more services, the need for infrastructure is rising rapidly. Meanwhile, increasingly severe weather events and rising sea levels pose direct threats to infrastructure assets and the critical services these provide, with lack of precise knowledge about future climate change making long-term planning increasingly difficult.

So how can we address these challenges? Many argue that the answer lies in new approaches to sustainable infrastructure development. The New Climate Economy’s Sustainable Infrastructure Imperative sees investing in sustainable infrastructure as “key to tackling the three central challenges facing the global community: reigniting growth, delivering on the Sustainable Development Goals, and reducing climate risk in line with the Paris Agreement.” 3

Indeed, the Paris Agreement, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development—which supports the Sustainable Developments Goals (SDGs) developed by UN member states—the New Urban Agenda and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction all require investments that deliver climate-resilient infrastructure that supports sustainable development.

Among the SDGs, SDG 9 explicitly refers to building resilient infrastructure. However, all the goals are underpinned by infrastructure development. “Infrastructure is really at the centre of the delivery of the SDGs,” says Virginie Marchal, senior policy analyst in the OECD’s Environment Directorate. She cites inequality as a key example. “How can you make sure that by building the right type of infrastructure you not only have a positive impact on the environment and meet climate goals but you also contribute to reducing inequality within societies?”

Achieving SDG 10—reduced inequalities—means meeting a number of the other SDGs. For example, SDG 6—availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all—demands investments in infrastructure of at least US$114bn a year, according to the World Bank. 4 When it comes to meeting SDG 7—access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all—investments needed include US$52bn per year to achieve universal electrification by 2030, only half of which is covered by planned investments. 5 And by helping empower women and girls, infrastructure contributes to meeting the objectives of SDG 5.

But what do we mean by “sustainable infrastructure”? First, while they offer solutions to sustainable development, infrastructure assets can have negative impacts. For example, infrastructure is responsible for more than 60% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. 6 The construction of large infrastructure assets, such as dams and railways, can disrupt and displace communities.

Sustainable infrastructure therefore needs to be planned, designed, delivered, managed and decommissioned to minimise its negative impacts and maximise its positive impacts. Meanwhile, infrastructure assets—throughout their entire lifecycle—should have positive impacts on the economy, society and the environment.

In this essay, Chapter 1 discusses the benefits of infrastructure, Chapter 2 examines the barriers to delivering sustainable infrastructure, and Chapter 3 highlights solutions and best practices.

The dividends

Delivering economic gains.

Investments in infrastructure will be instrumental in meeting the SDGs. By creating jobs and economic activity, infrastructure enables development. It also provides the services that underpin the ability of people to be economically productive, for example via transport. “The transport sector has a huge role in connecting populations to where the work is,” says Ms Marchal.

Infrastructure investments help stem economic losses arising from problems such as power outages or traffic congestion. The World Bank estimates that in Sub-Saharan Africa closing the infrastructure quantity and quality gap relative to the world’s best performers could raise GDP growth per head by 2.6% points per year. 7

In the US, it is estimated that about 63m full-time jobs in industries such as tourism, retail, agriculture and manufacturing depend on the quality, safety and reliability of transport infrastructure. 8 And McKinsey Global Institute analysis suggests that increasing infrastructure investment by 1% of GDP could create major new job opportunities across the world (see chart 1). 9

The failure of infrastructure is also a useful indicator of its economic value. For example, in 2013, when the Dawlish sea wall in south-west England was destroyed during storms, the repairs to the wall itself cost £35m, but the loss of a critical transport connection to the south west of England was estimated to cost the UK economy £1.2bn. 10

Infrastructure itself can also become more economically productive. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates that increasing the productivity of infrastructure can cut spending needs by 40%. Steps it recommends include optimising portfolios to avoid investing in projects that fail to meet needs or deliver sufficient benefits, streamlining processes, and implementing measures that increase the performance of existing assets. 11

Protecting the natural environment

From renewable energy to transport systems, the environmental benefits of infrastructure are manifold. For example, in the US, estimates are that if someone commuting 20 miles a day switches from driving to public transportation, it would lower their carbon footprint by 4,800 pounds annually. 12 Sustainable infrastructure assets can help to address climate and natural disasters, reduce greenhouse gas emissions and contamination, manage natural capital, and enhance resource efficiency. “The infrastructure built in the next five years will determine how we meet the Paris climate goals,” says Ms Marchal. “It’s a threat but also a huge opportunity for countries to leapfrog to infrastructure that is fit for climate.”

Professor Hall cites transportation as a tool in fossil-fuel reduction. “The transport sector needs to be largely electrified,” he says. “Whether you bank on electric vehicles or invest in mass transport in urban areas, it’s fundamental.”

Technology will facilitate significant environmental gains. In power infrastructure, for example, smart meters allow energy utilities to manage consumption patterns, creating price incentives to use electricity outside peak times, enabling them to reduce reliance on the more polluting “peaker plants” that supplement supply at peak demand times and that usually generate power using fossil fuels. 13

Integrating green infrastructure such as trees, plantings and forests into the portfolio of assets can improve air quality and contribute to removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere or, in the case of mangroves, increasing flood protection and preventing soil erosion. Green roofs act as giant sponges, soaking up stormwater before it pollutes rivers and lakes, assist with flood control and, collectively, can reduce temperatures in cities during the summer. For example, one simulation study found that covering half of the available surfaces in downtown Toronto with green roofs would cool the city by up to 2˚C in some areas. 14

However, Professor Hall argues that efforts to increase investments in green infrastructure should not eclipse work to ensure that traditional infrastructure is sustainable. This includes addressing the emissions created by constructing and operating infrastructure. Erecting and running buildings, for example, consumes 36% of the world’s energy and produces some 40% of energy-related carbon emissions, according to estimates by the International Energy Agency, a research group. Meanwhile, while regulations are being introduced in many countries to reduce the environmental impact of construction, emissions generated by existing infrastructure must also be managed. In the developed world, for example, only about one in 100 buildings is replaced by a new one every year. 15

“If we focus only on green infrastructure, we lose sight of the amount that’s being spent on grey infrastructure and the potential for locking in patterns of development that may or may not be sustainable,” Professor Hall says.

Underpinning social progress

From schools, hospitals and roads to power and water networks, sustainable infrastructure enables governments and the private sector to provide services that contribute to sustainable individual livelihoods, as well as broader economic growth, while improving quality of life and enhancing human dignity. As part of this, ensuring equitable access to these services is critical, an aspiration enshrined in many of the SDGs, which call for basic services such as health, education, shelter, water and sanitation to be available to all.

When it comes to gender equality, infrastructure plays an important role, both protecting women and accelerating their advancement. For example, public transport systems both enable women to enter the workforce but also, when well designed, provides them with safety and security and ensures that they have equal access to opportunities and services.

Sanitation infrastructure is also crucial in ensuring equal participation in economic and education opportunities. If safe toilets or private hygiene facilities in schools or workplaces are unavailable, during menstruation women and girls are often forced to stay at home or leave school or their jobs altogether. The World Bank estimates that at least 500m women and girls globally lack adequate facilities for menstrual hygiene management. 16

This can also be harmful to women and girls. “Maternal mortality rates are affected by the quality of water and hygiene. And it tends to be the girls who don’t go to school because they have to go and fetch water,” says Ms Fay. “Services do have these differential impacts on gender.”

Infrastructure is a tool in increasing social mobility. For example, introducing solar power to Sudan and Tanzania in schools enabled an increase in completion rates at primary and secondary schools from less than 50% to almost 100%. 17

Morgan Landy, senior director of global infrastructure and natural resources at the International Finance Corporation (IFC), argues that infrastructure’s social impact is rising up the agenda. “If you are going to have a wind power project you need to bring a community lens to that to make sure the benefits are shared,” he says. “That’s the future. The environmental side will always be strong, but the next frontier will be social impact.”

The role of resilience

Infrastructure that can withstand the shocks and stresses experienced over its lifetime provides resilience and protects development by having a positive impact across all three pillars of sustainability.

Resilient infrastructure protects the economy by reducing disruptions to industry from shocks, such as severe storms. Similarly, when resilient infrastructure ensures the continuity of critical services such as power and water during a crisis, it offers greater stability to communities and reduced disruption to their livelihoods. “During hurricanes in the Caribbean, you lose particular bridges,” says Graham Watkins, principal environmental specialist in the climate change division of the Inter-America Development Bank (IDB). “So if you strengthen those bridges that are critical, you can maintain conduits and people suffer less.”

If infrastructure has to be less frequently rebuilt or repaired, governments not only save money—they also need to use fewer natural resources. Moreover, using green infrastructure to protect against climate-related floods and intense storms helps communities adapt to the effects of climate change. Examples range from street plantings, parks and green roofs in cities to wetlands and mangrove forests, which protect coastal communities from storm surge and sea-level rise.

Japan is well recognised for its ability to build highly resilient infrastructure that can withstand frequent or severe earthquakes. This includes the construction by many towns and cities of new energy infrastructure based on micro-grids—groups of interconnected and distributed energy resources that act as single, controllable entities—and decentralised power sources. Supporting such developments is the country’s National Resilience Programme, established in the wake of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. 18

However, Ms da Silva stresses that resilient infrastructure goes beyond the assets explicitly designed for the protection and mitigation of disasters to all systems that support society—such as energy, transport and water—and how they connect with each other.

“When you look at the definition of critical infrastructure, it is critical if, when it fails, it has a severe detrimental effect on human wellbeing and economic development,” says Ms da Silva, who leads the Resilience Shift, an initiative supported by the Lloyds Register Foundation to raise awareness of the need for infrastructure to be resilient and develop new approaches that will drive changes to current practice.

“Given the complexity of modern infrastructure and the pressures on infrastructure systems due to increasing demand, ageing and/or climate change, failure is a possibility,” she says. “So infrastructure has to be resilient or it’s going to have a severe effect on society.”

The Challenges

Growing demand.

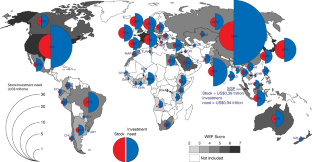

As the world’s population expands, delivering basic services will become increasingly challenging. And as more and more people live in cities, pressures on urban infrastructure are becoming intense. By one estimate, infrastructure investment of up to US$3.2trn-US$3.7trn per year is needed between now and 2030. 19 Infrastructure investment gaps are already an issue in many emerging and developing markets, totalling US$452bn over 2014-20, with actual spending of an estimated US$259bn dwarfed by requirements of US$711bn (see chart 2).

The G20-backed Global Infrastructure (GI) Hub estimates that investments of US$94trn in infrastructure will be needed by 2040. More than half of these investment needs are in Asia, according to GI Hub. At US$28trn, representing 30% of global infrastructure investment needs, China will have the greatest demand over this period.

Some of the gaps look daunting. Take water and sanitation infrastructure. In 2015 some 844m people lacked even a basic drinking-water service, according to the World Health Organisation, and at least 2bn people were using drinking water sources contaminated with faeces. 10

Meanwhile, if current spending trends continue, the US—where an estimated US$3.8trn needs to be invested in infrastructure 21 —is forecast to have the world’s biggest spending gap to 2040, according to the GI Hub. 22 This imposes a high price on Americans, with one estimate that the cost to the average motorist of poor road infrastructure is US$599 annually, or US$130bn nationally in repair costs, accelerated vehicle deterioration and depreciation, increased maintenance, and additional fuel consumption. 23

The increasing risks and vulnerabilities brought about by climate change will also increase pressure to upgrade infrastructure and repair or replace assets damaged during extreme weather. For example, tens of billions of dollars of damage to infrastructure in New York and New Jersey was caused by Hurricane Sandy in 2012, prompting the creation of the Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force. 24

Funding and resource gaps